Abstract

Objective

To determine factors independently associated with Cardiac Rehabilitation (CR) referral, which are currently not well described at a national level.

Background

Substantial numbers of eligible patients are not referred to CR at hospital discharge despite proven reductions in mortality and national guideline recommendations.

Methods

We used data from the American Heart Association’s (AHA’s) Get With the Guidelines (GWTG) program, analyzing 72,817 patients discharged alive following a myocardial infarction (MI), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery between 1/00 and 9/07 from 156 hospitals. We identified factors associated with CR referral at discharge and performed multivariable logistic regression, adjusted for clustering, to identify which factors were independently associated with CR referral.

Results

Mean age was 64.1±13.0 years, 68% were male, 79% white, 30% had diabetes, 66% hypertension, and 52% dyslipidemia; mean body mass index was 29.1±6.3 kg/m2 and mean ejection fraction 49.0±13.6%. All patients were admitted for coronary artery disease (CAD), with 71% admitted for MI. Overall, only 40,974 (56%) were referred to CR at discharge, ranging from 53% for MI, to 58% for PCI, and to 74% for CABG patients. Older age, non-ST-elevation MI, and the presence of most co-morbidities were associated with decreased odds of CR referral.

Conclusions

Despite strong evidence for benefit, only 56% of eligible CAD patients discharged from these hospitals were referred to CR. Increased physician awareness about the benefits of CR and initiatives to overcome barriers to referral are critical to improve the quality of care of patients with CAD.

Keywords: coronary artery disease, exercise, prevention, cardiac rehabilitation

Introduction

Cardiac rehabilitation reduces morbidity and mortality in coronary artery disease (CAD) patients after myocardial infarction, improves risk factor management, and is a class I indication in numerous national guidelines following myocardial infarction or revascularization (1–8). However, despite the proven benefits of cardiac rehabilitation and these national guideline recommendations, cardiac rehabilitation continues to be significantly underutilized, based predominately on single center evaluations (1,9–17). A recent analysis of national Medicare claims data also indicated that cardiac rehabilitation use is suboptimal as only 19% of Medicare patients enrolled in cardiac rehabilitation following a myocardial infarction or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery (9). These claims based analyses, however, lacked the detailed clinical data necessary to accurately determine eligibility for cardiac rehabilitation or to determine what percentage had actually been referred for cardiac rehabilitation.

In response to these data concerning the underutilization of cardiac rehabilitation, the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation (AACVPR), the American College of Cardiology (ACC), and the American Heart Association (AHA) recently published performance measures for the referral to and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation services (18). These performance measures state that all hospitalized patients with a qualifying cardiovascular disease event should be referred to outpatient cardiac rehabilitation prior to hospital discharge. Qualifying cardiovascular disease events include: myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), CABG surgery, stable angina, heart transplant, and heart valve surgery. As the authors of these performance measures emphasize, numerous barriers preventing attendance in cardiac rehabilitation exist, but the most important and easily overcome barrier is the failure of health care providers to refer eligible patients to cardiac rehabilitation (18). Understanding referral patterns and barriers to cardiac rehabilitation referral is necessary to improve the utilization of cardiac rehabilitation in eligible CAD patients.

Our current study extends these prior works investigating cardiac rehabilitation underutilization by analyzing cardiac rehabilitation referral among eligible patients with myocardial infarction, PCI, or CABG surgery discharged from hospitals participating in the AHA Get With the Guidelines (GWTG) program. Furthermore, we identified factors that were independently associated with cardiac rehabilitation referral.

Methods

Data Source

The AHA GWTG program is a voluntary, observational data collection and quality-improvement initiative that began in 2000 and has been described in detail previously (19). Participating hospitals use the point-of-service, interactive, Internet-based Patient Management Tool (Outcome Sciences, Inc, Cambridge, Mass) to submit clinical information regarding inhospital care and outcomes of patients hospitalized for CAD, stroke, or heart failure. Participating hospitals submit consecutive, eligible patients to the database and compliance with local regulatory and privacy guidelines is required.

Trained personnel abstract the data, and patients are assigned to race/ethnicity categories using options defined by the electronic case report form. Other variables collected in the CAD module include socio-demographic and clinical characteristics, medical history, admitting diagnosis, inpatient medical therapies and procedures, ejection fraction, hospital characteristics, compliance with CAD-related performance measures including referral to cardiac rehabilitation, contraindications for evidence-based therapies, and in-hospital outcomes. Referral to cardiac rehabilitation is recorded as: 1) yes, 2) no, 3) not documented, or 4) not applicable.

Outcome Sciences, Inc. serves as the data collection and coordination center for GWTG. The Duke Clinical Research Institute serves as the data analysis center and has an agreement and Institutional Review Board approval to analyze the aggregate de-identified data for research purposes. The Internet-based data entry system includes edit checks to insure the completeness of the reported data. Data quality is monitored and reports are generated to assure the completeness and accuracy of the submitted data. Only sites and variables with a high degree of completeness are included in analyses.

Study Population

We identified 310,563 patients with CAD-related diagnoses discharged from 555 GWTG participating hospitals between January 2000 and September 2007 in the GWTG CAD module. We limited our analysis to individuals with Class I indications for cardiac rehabilitation by only including patients discharged alive who had an acute myocardial infarction, PCI, or CABG surgery during their hospitalization. We excluded patients whose primary admission diagnoses were non-CAD related (n=26,932), those without an acute myocardial infarction, PCI, or CABG surgery (n=59,121), and those discharged to skilled nursing facilities, acute care facilities, hospice, against medical advice, expired, or whose discharge status was not documented or missing (n=48,302). Additionally, to ensure the accuracy of our analysis, patients discharged from hospitals failing to report data on past medical history or in-hospital procedures >10% of the time (n=52,483 patients from 201 hospitals) or cardiac rehabilitation referral >25% of the time (n=50,908 patients from 170 hospitals) were also excluded. This resulted in a final sample size of 72,817 patients from 156 hospitals. Compared with those included in the analysis, hospitals excluded from the analysis had fewer beds, were less likely to be a teaching hospital, less likely to have interventional and heart transplant capabilities, and more likely to be from the northeast.

Statistical Analysis

The main outcome measure was the proportion of patients referred to cardiac rehabilitation at discharge. Individuals with missing values for cardiac rehabilitation referral, cardiac rehabilitation referral not documented, or those with cardiac rehabilitation recorded as “not applicable” were considered not referred for this analysis. Because “not applicable” might be used to document those felt to have a contraindication for cardiac rehabilitation, we also calculated the proportion of individuals referred to cardiac rehabilitation after excluding those individuals where “not applicable” was recorded (n=7,454).

Using chi-square tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables, we compared the baseline characteristics of patients referred to cardiac rehabilitation with those not referred. Additionally, we were interested in whether individuals referred to cardiac rehabilitation were more likely to receive other evidence-based therapies during their hospitalization. To investigate this, we compared compliance with established CAD performance measures (20,21) between those referred and not referred to cardiac rehabilitation using chi square. Percentages and medians with interquartile ranges were reported for categorical and continuous variables respectively.

A multivariable logistic regression analysis using the generalized estimating equations (GEE) method, adjusting for within-hospital clustering, was performed to identify factors associated with cardiac rehabilitation referral at discharge. The initial model included age, gender, race, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, insurance status, admitting diagnosis, procedures (PCI or CABG), hospital characteristics (bed size, region, teaching status, and transplant capability), and patient co-morbidities including anemia, stroke, heart failure, prior myocardial infarction, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral arterial disease, chronic kidney disease (serum creatinine >2.0 mg/dL), dialysis, atrial fibrillation or flutter, depression, pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, and alcohol or tobacco use. Factors with a p-value <0.05 were kept in the reduced model and the odds ratios for the significant factors in the reduced model were reported. A secondary analysis adding a variable for the presence of a left ventricular ejection fraction <40% into the reduced model was performed to evaluate the influence of left ventricular systolic dysfunction on the probability of cardiac rehabilitation referral. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests. All analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

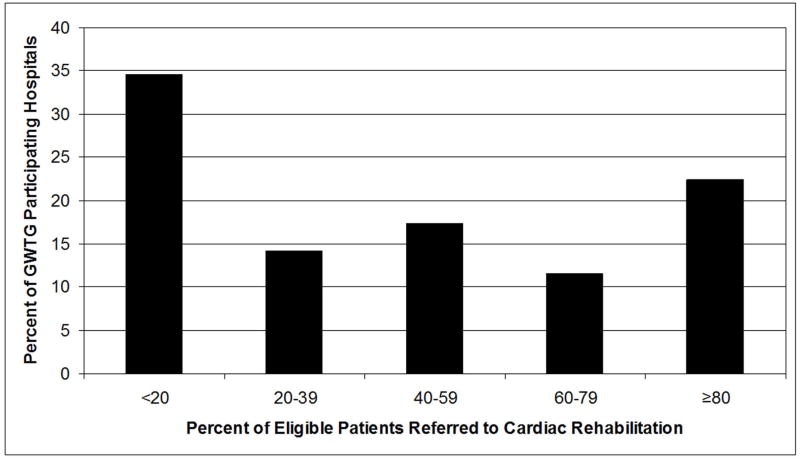

Of the 72,817 individuals discharged from these 156 GWTG participating hospitals following a myocardial infarction, PCI, or CABG surgery from January 2000 to September 2007, only 40,974 (56%) were referred to cardiac rehabilitation at hospital discharge. This ranged from 53% for patients admitted with a myocardial infarction, to 58% for those undergoing PCI, to 74% for those undergoing CABG surgery. After excluding individuals where cardiac rehabilitation was deemed to be “not applicable,” still only 63% (40,974 of 65,363) were referred. The distribution of referral rates by hospital is displayed in Figure 1. The median referral rate by hospital was 43% and ranged from 0 to 100%. As shown in Figure 1, 35% of hospitals referred fewer than 20% of eligible patients, and only one-third of hospitals referred over 60% of eligible patients.

Figure 1. Cardiac Rehabilitation Referral Patterns Among 156 Get With the Guidelines Participating Hospitals, 2000–2007.

GWTG=Get With the Guidelines

Table 1 lists the demographic and clinical characteristics in the overall population as well as in those referred and not referred to cardiac rehabilitation. When compared with those not referred, individuals referred to cardiac rehabilitation were younger, more likely to be male and white race, less likely to have an unspecified or non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, less likely to have Medicare, less likely to have most medical co-morbidities, and more likely to have undergone PCI or CABG. Table 2 lists the proportion of eligible individuals who received therapies in compliance with established performance measures in the overall population and among those referred or not referred to cardiac rehabilitation. Individuals referred to cardiac rehabilitation were also more likely to receive therapies in accordance with each of these performance measures.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics in the Overall Population and in Those Referred and Not Referred to Cardiac Rehabilitation

| Overall Population (n=72,817) | Not Referred to CR (n=31,843) | Referred to CR (n=40,974) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64 (55–74) | 65 (55–75) | 63 (54–73) | <0.0001 |

| Gender (%) | ||||

| Female | 32.1 | 33.7 | 30.8 | <0.0001 |

| Race (%) | ||||

| White | 79 | 76 | 82 | |

| African American | 7 | 7 | 7 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic | 7 | 10 | 5 | |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 28.2 (25.0–32.2) | 27.9 (24.7–32.0) | 28.4 (25.2–32.4) | <0.0001 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 50 (40–60) | 50 (40–60) | 50 (40–60) | 0.0039 |

| Admitting Diagnosis (%) | ||||

| Unspecified MI | 45.3 | 51.1 | 40.7 | |

| CAD | 20.7 | 15.8 | 24.6 | |

| Non-STEMI | 16.3 | 17.4 | 15.4 | <0.0001 |

| STEMI | 9.1 | 7.4 | 10.4 | |

| Unstable Angina | 8.7 | 8.3 | 8.9 | |

| Insurance Status (%) | ||||

| Other | 56.3 | 50.9 | 60.5 | |

| Medicare | 32.3 | 37.2 | 28.5 | <0.0001 |

| None | 8.2 | 8.4 | 8.1 | |

| Medicaid | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.0 | |

| Co-Morbidities (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 66.3 | 66.8 | 65.9 | 0.0192 |

| Dyslipidemia | 51.6 | 47.8 | 54.6 | <0.0001 |

| Smoking | 31.4 | 29.0 | 33.3 | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 30.1 | 31.0 | 29.4 | <0.0001 |

| Prior MI | 19.2 | 19.7 | 18.8 | 0.0029 |

| COPD | 11.5 | 12.4 | 10.9 | <0.0001 |

| PAD | 7.5 | 8.1 | 7.1 | <0.0001 |

| Stroke or TIA | 5.8 | 6.9 | 4.9 | <0.0001 |

| Chronic Dialysis | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.2 | <0.0001 |

| ICD | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0086 |

| In-Hospital Procedures (%) | ||||

| PCI | 66.8 | 64.5 | 68.6 | <0.0001 |

| CABG | 15.3 | 9.0 | 20.2 | <0.0001 |

All values listed as median (interquartile range) or %.

Wilcoxon two-sample test performed for continuous variables.

Chi-square test performed for categorical variables.

CABG=coronary artery bypass graft surgery, CAD=coronary artery disease, COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, CR=cardiac rehabilitation, ICD=implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, MI=myocardial infarction, PAD=peripheral arterial disease, PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention, STEMI=ST-segment myocardial infarction, TIA=transient ischemic attack.

Table 2.

Proportion of Eligible Individuals in the Overall Population and in Those Referred and Not Referred to Cardiac Rehabilitation who Received Therapies in Compliance with Established Performance Measures

| Overall Population (n=72,817) | Not Referred to CR (n=31,843) | Referred to CR (n=40,974) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| During Hospitalization | ||||

| AMI and angina patients without CI receiving aspirin <24 hours | 95.6 | 94.3 | 96.7 | <0.0001 |

| Current smokers that receive smoking cessation advice | 92.1 | 88.0 | 94.9 | <0.0001 |

| Patients with a LDL-C >100 mg/dL receiving lipid lowering drugs | 89.6 | 85.3 | 92.5 | <0.0001 |

| At Discharge | ||||

| Patients with documented LVSD discharged on an ACE-I or ARB | 83.5 | 80.9 | 85.6 | <0.0001 |

| Patients discharged on aspirin | 97.6 | 96.5 | 98.5 | <0.0001 |

| Patients discharged on beta-blockers | 93.0 | 91.7 | 94.0 | <0.0001 |

All values listed are %.

ACE-I=ace inhibitor, ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker, AMI=acute myocardial infarction, CI=contraindication, CR=cardiac rehabilitation, LDL-C=low density lipoprotein cholesterol, LVSD=left ventricular systolic dysfunction

Factors independently associated with cardiac rehabilitation referral in the final multivariable model are listed in Table 3. Undergoing CABG surgery (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 3.00) and PCI (AOR 1.67) were the factors most strongly associated with cardiac rehabilitation referral. Other factors independently associated with referral included younger age, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, and a history of dyslipidemia or smoking. Most co-morbidities were associated with decreased odds for referral. Adding left ventricular systolic dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction <40%) into the model did not significantly alter the factors associated with cardiac rehabilitation referral. Patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction were slightly less likely to be referred to cardiac rehabilitation (AOR 0.96, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.92–1.01), although this association was not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Predictors of Referral to Cardiac Rehabilitation in the Overall Population

| Variable | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Variable | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Co-Morbidities | ||

| ≥50 | Referent | Dyslipidemia | 1.15 (1.08–1.23) |

| 51–65 | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | Smoking | 1.10 (1.05–1.15) |

| 66–80 | 0.92 (0.87–0.97) | Hypertension | 0.95 (0.91–0.99) |

| > 80 | 0.76 (0.71–0.82) | Prior MI | 0.95 (0.90–0.99) |

| Admitting Diagnosis | COPD | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) | |

| STEMI | Referent | PAD | 0.92 (0.87–0.98) |

| Non-STEMI | 0.84 (0.76–0.93) | Stroke/TIA | 0.91 (0.87–0.96) |

| Unspecified MI | 0.73 (0.53–0.99) | Chronic Dialysis | 0.79 (0.70–0.90) |

| CAD | 0.71 (0.57–0.87) | ICD | 0.74 (0.55–1.00) |

| Unstable Angina | 0.63 (0.50–0.78) | Procedures | |

| CABG | 3.00 (2.32–3.87) | ||

| PCI | 1.67 (1.50–1.85) |

CABG=coronary artery bypass graft surgery, CAD=coronary artery disease, CI=confidence interval, COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ICD=implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, MI=myocardial infarction, PAD=peripheral arterial disease, PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention, STEMI=ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, TIA=transient ischemic attack

Discussion

Participation in cardiac rehabilitation is associated with reductions in mortality and recurrent myocardial infarction. Taylor et al, in a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of exercise based cardiac rehabilitation, demonstrated that participation in cardiac rehabilitation was associated with significant reductions in both all-cause mortality (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.68–0.93) and cardiac-specific mortality (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.61–0.96) after a median follow-up of 15 months (22). Witt and colleagues have subsequently extended these data by demonstrating that participation in contemporary, community-based cardiac rehabilitation programs, which enroll older and higher risk patients not enrolled in clinical trials and provide more comprehensive approaches to secondary prevention in addition to exercise training, is associated with reduced mortality and fewer recurrent myocardial infarctions (23). Despite these proven benefits of cardiac rehabilitation, previous studies from predominantly single centers within the United States report referral rates of less than 25–30% (11–15). In our study, only approximately one-half of eligible patents in this large, nationwide sample of 72,817 patients discharged from 156 GWTG participating hospitals were referred to cardiac rehabilitation. We also observed substantial variation among hospitals in the percentage of eligible patients referred to cardiac rehabilitation. In 35% of hospitals, fewer than 20% of eligible patients were referred, while only one-third referred over 60%. Given that GWTG hospitals in general (24–25), as well as the subset of those hospitals included in this analysis, report very good compliance with virtually all other secondary prevention performance measures, we believe our results represent a best case scenario among hospitals with high adherence rates to core measures and sufficient resources for excellent data collection.

We also observed that individuals not referred to cardiac rehabilitation were less likely to have received other guidelines-based therapies as defined by recent performance measures (20,21). Individuals not referred to cardiac rehabilitation were less likely to be discharged on aspirin, beta-blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers if they had left ventricular systolic dysfunction, to receive lipid lowering agents if they had a low density lipoprotein cholesterol level >100 mg/dL, and to receive smoking cessation counseling. Most concerning, however, is that despite the wealth of data on the benefits of cardiac rehabilitation, the overall referral rate to cardiac rehabilitation (56%) was far lower than for any of the other performance measures studied (which ranged from 84–98%), suggesting that physician awareness about the benefits of cardiac rehabilitation is lower than for other interventions.

Cortes and Arthur recently systematically reviewed 10 studies to examine referral patterns to cardiac rehabilitation (17). Major predictors of referral to cardiac rehabilitation included being English speaking, admitted to a hospital with a cardiac rehabilitation program, insurance status, and previous myocardial infarction. Other less significant predictors included younger age, cardiac catheterization, hypercholesterolemia, CABG surgery, hypertension, and smoking (17). Our results are similar. Younger age, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, and the performance of PCI or CABG surgery were associated with increased odds of cardiac rehabilitation referral. Individuals with dyslipidemia and those who smoked also had increased odds of cardiac rehabilitation referral; in contrast, most co-morbidities were associated with lower odds of referral. Individuals with co-morbidities may be perceived by physicians as less likely to benefit or less likely to participate in cardiac rehabilitation; however, in many instances, these individuals represent populations at significantly increased cardiovascular risk who may benefit from the more intense secondary prevention services provided in cardiac rehabilitation (23). A recent analysis examining patient and physician factors affecting cardiac rehabilitation referral concluded that among physicians, one of the most important factors influencing whether physicians refer patients to cardiac rehabilitation was the degree of the physician’s perceived benefit of cardiac rehabilitation (26). Therefore, increased physician awareness about the benefits of cardiac rehabilitation in these higher risk sub-groups may increase referrals.

Obviously, individuals cannot enroll and participate in cardiac rehabilitation if they are not first referred. Mazzini et al report that, in a single center using a GWTG-based clinical pathway, 55% of patients with myocardial infarction were referred to cardiac rehabilitation at discharge (27). However, the subsequent enrollment rate into cardiac rehabilitation for these individuals who were referred prior to discharge was only 34% (27). With no more than one-half of eligible patients being referred and only one-third of those referred enrolling, it is not surprising that most studies, including a recent analysis of 267,427 Medicare beneficiaries with acute myocardial infarctions or CABG surgery, report overall enrollment rates into cardiac rehabilitation of only about 15–20% (9–15). One notable exception is Olmsted County, Minnesota where 55% of individuals enrolled into cardiac rehabilitation following a myocardial infarction between 1982 and 1998 (2). Numerous barriers exist which prevent referred patients from enrolling into cardiac rehabilitation including cost, lack of insurance coverage, time commitment, and distance from a cardiac rehabilitation center. However, despite these barriers, simply increasing the proportion of eligible patients referred to cardiac rehabilitation, as recommended by numerous ACC/AHA guidelines (4–8) and a recently published AACVPR/ACC/AHA performance measure (18), could substantially increase cardiac rehabilitation enrollment.

Investigators in Canada have examined the effectiveness of computer generated, automatic referral at discharge of eligible patients to cardiac rehabilitation (28–31). These authors report enrollment rates into cardiac rehabilitation ranging from as low as 43% to as high as 73% (28–31). These data support the hypothesis that failure to refer patients to cardiac rehabilitation represents one of the largest and, potentially, most easily overcome barrier to participation in cardiac rehabilitation. By simply increasing referral rates, these authors report much higher rates of enrollment in cardiac rehabilitation than is reported using standard, physician-initiated referral practices. However, automatically referring patients to cardiac rehabilitation may not be enough. Mazzini et al report that among those who were referred to cardiac rehabilitation but did not enroll, 26% reported that they did not perceive that they had been referred (27), reflecting a gap between what is documented in the medical record and what the patient actually recalls following discharge. Additionally, multiple previous studies have demonstrated that physician endorsement of the benefits of cardiac rehabilitation is one of the most powerful predictors of attendance in cardiac rehabilitation among patients who are referred (13,14,16). Therefore, a computer generated referral, although helpful in prompting physicians to initiate referrals, may not be sufficient to correct the current vast underutilization of cardiac rehabilitation.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, hospital participation in the GWTG program is voluntary. Therefore, the overall proportion of eligible patients referred to cardiac rehabilitation and predictors of referral may not be the same in non-participating hospitals. Furthermore, even among participating hospitals, we are not able to determine the referral patterns of those hospitals with a large amount of missing data about cardiac rehabilitation referral. This does limit the generalizabilty of our findings; however, we are unlikely to have underestimated the proportion of eligible patients referred to cardiac rehabilitation in the United States. Rather, we believe that our results represent a best case scenario among hospitals with high adherence rates to core measures in general. Hospitals excluded from our analysis as well as non-GWTG participating institutions very likely refer a lower proportion of eligible CAD patients to cardiac rehabilitation. Therefore, the overall referral rate within the United States is likely lower than what we estimate in this analysis. Second, the GWTG program only collects in-hospital data and does not collect data on physician characteristics. Therefore, we are unable to assess what proportion of individuals are referred to cardiac rehabilitation following discharge from the hospital or what percentage of those referred actually attend cardiac rehabilitation. Furthermore, we are unable to determine what physician characteristics contribute to cardiac rehabilitation referral. Third, we lack detailed data on socioeconomic variables such as income and education levels of eligible patients, which prohibits us from assessing the impact that these variables have on referral rates. Fourth, we cannot exclude residual measured and unmeasured confounding variables that might account for these associations with cardiac rehabilitation referral.

Overall, only approximately one-half of patients discharged from these GWTG participating hospitals who were eligible for cardiac rehabilitation following a myocardial infarction, PCI, or CABG surgery were referred at hospital discharge. Older individuals, as well as those with most of the co-morbidities we studied had decreased odds of cardiac rehabilitation referral. Individuals with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction or who underwent PCI or CABG surgery had increased odds for referral. More emphasis on increasing referral to cardiac rehabilitation is necessary to overcome the current underutilization of cardiac rehabilitation in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

Get With The Guidelines-CAD is sponsored by the American Heart Association with funding in part from an unrestricted education grant from the Merck-Schering Plough Partnership. At the time of this work, Dr. Brown was supported in part by grant 5 T32 HS013852 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD, USA.

Abbreviations List

- AACVPR

American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- ACC

American College of Cardiology

- AHA

American Heart Association

- AOR

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- CABG

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft

- CAD

Coronary Artery Disease

- CI

Confidence Interval

- GEE

Generalized Estimating Equations

- GWTG

Get With the Guidelines

- PCI

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Footnotes

Dr. Hernandez: Reasearch funding from Johnson & Johnson, GSK, Merck, Medtronic; Honoraria from Novartis, AstraZeneca.

Dr. Cannon: Research grants/support from Accumetrics, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Sanofi Partnership, Glaxo Smith Kline, Merck, Merck/Schering Plough Partnership; Clinical Advisor, equity in Automedics Medical Systems.

Dr. Piña: Speakers bureau with Solvay, AstraZeneca, Innovia, Merck, Sanofi-Aventis, Novartis; Consultant for FDA; Grant/Reasearch from NIH.

Dr. Fonarow: Honorarium/Consultant for Merck, Schering Plough, Glaxo Smith Kline.

Other Authors: No Disclosures

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wenger NK. Current status of cardiac rehabilitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1619–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witt BJ, Jacobsen SJ, Weston SA, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation after myocardial infarction in the community. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:988–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams MA, Ades PA, Hamm LF, et al. Clinical evidence for a health benefit from cardiac rehabilitation: An update. Am Heart J. 2006;152:835–841. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. [Accessed on June 23, 2008];ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction) 2004 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.014. Available at www.acc.org/clinical/guidelines/semi/index.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction): developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, American College of Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:e1–e157. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibbons RJ, Abrams J, Chatterjee K, et al. [Accessed on June 23, 2008];ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with chronic stable angina: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Chronic Stable Angina) 2002 doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02848-6. Available at www.acc.org/clinical/guidelines/stable/stable.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Eagle KA, Guyton RA, Davidoff R, et al. ACC/AHA 2004 guideline update for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1999 Guidelines for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery) American College of Cardiology; [Accessed on June 23, 2008]. Web Site. Available at: http://www.acc.org/clinical/guidelines/cabg/cabg.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith SC, Jr, Feldman TE, Hirshfeld JW, Jr, et al. ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/SCAI Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) American College of Cardiology; [Accessed on June 23, 2008]. Web Site. Available at: http://www.acc.org/clinical/guidelines/percutaneous/update/index.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suaya JA, Shepard DS, Normand S-L, Ades PA, Prottas J, Stason WB. Use of cardiac rehabilitation by medicare beneficiaries after myocardial infarction or coronary bypass surgery. Circulation. 2007;116:1653–1662. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.701466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mochari H, Lee JR, Kligfield P, Mosca L. Ethnic differences in barriers and referral to cardiac rehabilitation among women hospitalized with coronary heart disease. Prev Cardiol. 2006;9:8–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1520-037x.2005.3703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blackburn GG, Foody JM, Spencer DL, Park E, Apperson-Hansen C, Pashkow FJ. Cardiac rehabilitation participation patterns in a large, tertiary care center: evidence for selection bias. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2000;20:189–195. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200005000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bittner V, Sanderson B, Breland J, Green D. Referral patterns to a university-based cardiac rehabilitation program. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:252–255. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00830-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ades PA, Waldmann ML, Polk DM, Coflesky JT. Referral patterns and exercise response in the rehabilitation of female coronary patients aged ≥ 62 years. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69:1422–1425. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90894-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barber K, Strommel M, Kroll J, Holmes-Rovner M, McIntosh B. Cardiac rehabilitation for community-based patients with myocardial infarction: Factors predicting discharge recommendation and participation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:1025–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roblin D, Diseker RA, III, Orenstein D, Wilder M, Eley M. Delivery of outpatient cardiac rehabilitation in a managed care organization. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2004;24:157–164. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson L, Leclerc J, Erksine Y, Linden W. Getting the most out of cardiac rehabilitation: A review of referral and adherence predictors. Heart. 2005;91:10–14. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.045559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cortes O, Arthur HM. Determinants of referral to cardiac rehabilitation programs in patients with coronary artery disease: A systematic review. Am Heart J. 2006;151:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas RJ, King M, Lui K, Oldridge N, Pina IL, Spertus J. AACVPR/ACC/AHA 2007 performance measures on cardiac rehabilitation for referral to and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention services. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1400–33. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong Y, LaBresh KA. Overview of the American Heart Association “Get With the Guidelines” programs: Coronary heart disease, stroke, and heart failure. Crit Pathways in Cardiol. 2006;5:179–186. doi: 10.1097/01.hpc.0000243588.00012.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krumholz HM, Anderson JL, Brooks NH, et al. ACC/AHA Clinical Performance Measures for Adults With ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a report of the ACC/AHA Task Force on Performance Measures (ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Performance Measures Writing Committee) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:236–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drozda JP, Messer JV, Spertus J. [Accessed January 12, 2009];Clinical Performance Measure for Chronic Stable Coronary Artery Disease. Availabe at http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/370/cadminisetjune06.pdf.

- 22.Taylor RS, Brown A, Ebrahim S, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for patients with coronary heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Med. 2004;116:682–92. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witt BJ, Jacobsen SJ, Weston SA, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation after myocardial infarction in the community. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:988–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaBresh KA, Ellrodt AG, Gliklich R, Liljestrand J, Peto R. Get With the Guidelines for cardiovascular secondary prevention. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:203–209. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaBresh KA, Fonarow GC, Smith SC, Jr, et al. Improved treatment of hospitalized coronary artery disease patients with the Get With the Guidelines Program. Crit Pathways in Cardiol. 2007;6:98–105. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0b013e31812da7ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grace SL, Gravely-White S, Brual J, et al. Contribution of patient and physician factors to cardiac rehabilitation referral: a prospective multilevel study. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;10:653–662. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazzini MJ, Stevens GR, Whalen D, Ozonoff A, Balady GJ. Effect of an American Heart Association Get With the Guidelines Program-based clinical pathway on referral and enrollment into cardiac rehabilitation after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1084–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grace SL, Evindar A, Kung T, Scholey P, Stewart DE. Increasing access to cardiac rehabilitation: automatic referral to the program nearest home. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2004;24:171–174. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200405000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith KM, Harkness K, Arthur HM. Predicting cardiac rehabilitation enrollment: the role of automatic physician referral. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13:60–66. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000186626.06229.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grace SL, Evindar A, Kung T, Scholey PE, Stewart DE. Automatic referral to cardiac rehabilitation. Med Care. 2004;42:661–669. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000129901.05299.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grace SL, Scholey P, Suskin N, et al. A prospective comparison of cardiac rehabilitation enrollment following automatic vs. usual referral. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39:239–245. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]