Abstract

The global acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) pandemic is thought to have arisen by the transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1)-like viruses from chimpanzees in southeastern Cameroon to humans. TRIM5α is a restriction factor that can decrease the susceptibility of cells of particular mammalian species to retrovirus infection. A survey of TRIM5 genes in 127 indigenous individuals from southeastern Cameroon revealed that approximately 4 percent of the Baka pygmies studied were heterozygous for a rare variant with a stop codon in exon 8. The predicted product of this allele, TRIM5 R332X, is truncated in the functionally important B30.2(SPRY) domain, does not restrict retrovirus infection, and acts as a dominant-negative inhibitor of wild-type human TRIM5α. Thus, some indigenous African forest dwellers potentially exhibit diminished TRIM5α function; such genetic factors, along with the high frequency of exposure to chimpanzee body fluids, may have predisposed to the initial cross-species transmission of HIV-1-like viruses.

Keywords: HIV-1, susceptibility, restriction factor, cross-species transmission, polymorphism, mutant, Africa

Introduction

The primate immunodeficiency viruses include the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and type 2 (HIV-1 and HIV-2, respectively) and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV). Simian immunodeficiency viruses infect many of the feral chimpanzee and monkey species indigenous to various parts of Africa. (Allan et al., 1991; Apetrei et al., 2005; Bibollet-Ruche et al., 2004; Jolly et al., 1996; Souquière et al., 2001; Tomonaga et al., 1993; Santiago et al., 2002, 2005). SIVsm in sooty mangabeys in West Africa is closely related to HIV-2, supporting the hypothesis that HIV-2 arose by transmission of these viruses from monkeys to humans (Gao et al., 1992; Santiago et al., 2005; Chen et al., 1996, 1997; Lemey et al., 2003; Marx et al., 1991; Peeters et al., 1994). Although HIV-2 infection can result in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in humans, the major cause of AIDS is HIV-1. Phylogenetically, HIV-1 is classified into a Major (M) Group, an Outlier (O) Group and the non M-non O (N) Group (Lemey et al., 2004; Ayouba et al., 2000, 2001; HIV Sequence Compendium, 2008). HIV-1 Group M variants, responsible for the vast majority of AIDS cases globally, have been further subdivided into phylogenetically distinct clades that differ in prevalence according to geographic region (HIV Sequence Compendium, 2008).

Several pieces of evidence support a west central African origin for HIV-1. Firstly, HIV-1-like viruses in feral chimpanzees (SIVcpz), gorillas and cercopithecine monkeys have been identified in Cameroon (Van Heuverswyn and Peeters, 2007; Van Heuverswyn et al., 2005, 2006; Nerrienet et al., 2005; Courgnaud et al., 2003; Keele et al., 2006; Corbet et al., 2000, Gao et al., 1999). Secondly, significant HIV-1 genetic diversity exists among viruses isolated from humans in central Africa, indicating the presence of the virus for a long period of time relative to other regions (Peeters et al., 2003; Worobey et al., 2008; Vergne et al., 2003; Konings et al., 2006; Zhong et al., 2003). For example, individuals from rural villages in Cameroon are infected with HIV-1 from diverse clades and often harbor a number of circulating recombinant forms indicative of multiple infections (Vergne et al. 2003; Konings et al., 2006). Previous studies have documented multiple infections not only with HIV-1, but also with human T-cell leukemia viruses (HTLV-III, HTLV-IV), simian foamy virus, hepatitis C virus and GB virus C (GBV-C) in individuals in rural Cameroon (Konings et al, 2006; Switzer et al, 2006; Wolfe et al, 2004; Njouom et al, 2003; Kondo et al, 1997; Torimiro et al, unpublished data). Thirdly, rural populations in west central Africa are frequently exposed to the body fluids of non-human primates through hunting, butchering and keeping of pets (Hahn et al., 2000). The Baka pygmies are hunter-gatherers of southwestern Cameroon (Figure 1) whose semi-nomadic lifestyle has persisted, largely unchanged, for thousands of years. The repeated exposure of these forest-dwelling people to the body fluids of non-human primates may have created circumstances favorable to the initial transmission of HIV-1-like viruses from chimpanzees to a small number of humans. Once introduced into the human host, HIV-1 diverged from SIVcpz, presumably allowing improved replication and spread in the human population.

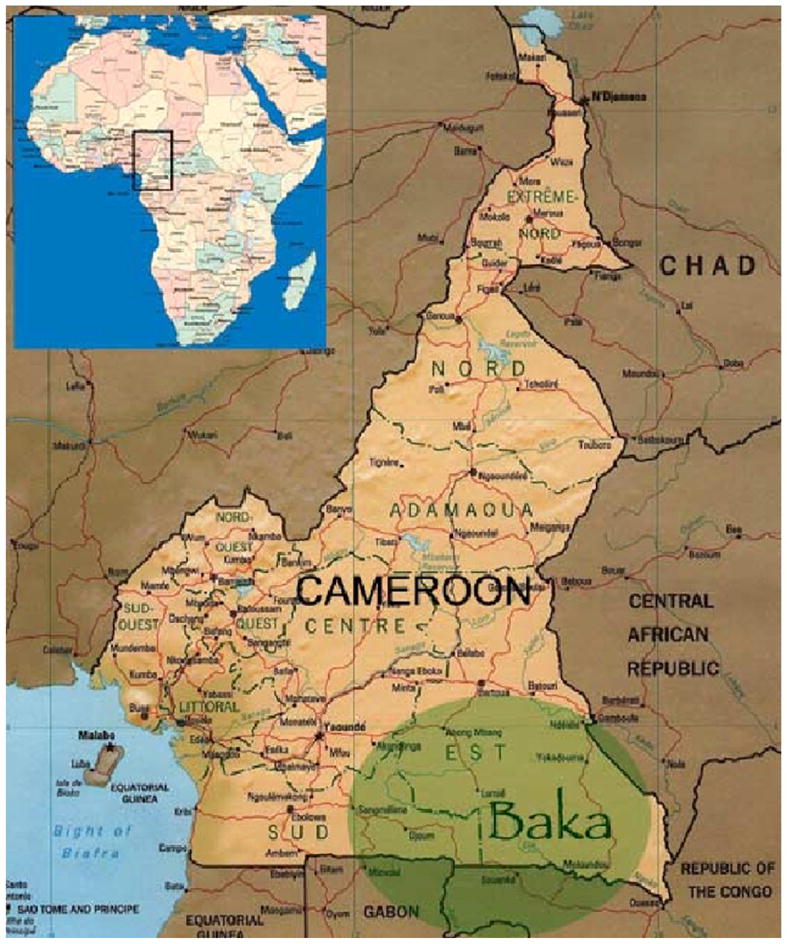

Figure 1. Geographic location of the Baka forest people.

The region of Africa highlighted in the box in the inset is shown, with the range of the Baka pygmy population shaded green. The Baka people constitute an ethnic group inhabiting the rain forest of southeastern Cameroon, northern Republic of Congo, northern Gabon and southwestern Central African Republic. The Baka pygmies number from 5,000 to 28,000 individuals.

A major barrier to cross-species transmission of retroviruses is mediated by the TRIM5α protein (Bieniasz, 2003; Hatziioannou et al., 2003; Hofmann et al., 1999; Stremlau et al., 2004a). Variants of TRIM5α in different primate species block the early, post-entry phase of infection of cells by particular retroviruses (Hatziioannou et al., 2004; Keckesova, Ylinen, and Towers, 2004; Song et al., 2005b; Perron et al., 2004; Yap et al., 2004). For example, the TRIM5α protein of rhesus monkeys restricts HIV-1 infection; even when expressed at comparable levels, human TRIM5α (TRIM5αhu) is less potent at suppressing HIV-1 or SIVcpz (Hatziioannou et al. 2004; Keckesova, Ylinen, and Towers, 2004; Stremlau et al. 2004a; Yap et al. 2004; Kratovac et al., 2008). On the other hand, TRIM5αhu more potently restricts infection by the N-tropic murine leukemia virus (N-MLV) than TRIM5αrh (Hatziioannou et al. 2004; Keckesova et al., 2004; Perron et al. 2004; Song et al., 2005b; Yap et al. 2004).

TRIM5 is a member of a family of proteins that contain a tripartite motif, hence the designation TRIM (Reymond et al., 2001). TRIM proteins have also been called RBCC proteins because the tripartite motif includes a RING domain, B-box 2 domain and coiled coil domain. TRIM proteins exhibit the propensity to assemble into cytoplasmic or nuclear bodies (Reymond et al., 2001). Many cytoplasmic TRIM proteins contain a C-terminal B30.2 or SPRY domain. Differential splicing of the TRIM5 primary transcript gives rise to the expression of several isoforms of the protein product. The TRIM5α isoform is the largest product (~493 amino acid residues in humans) and contains the B30.2(SPRY) domain. The B30.2(SPRY) domain of rhesus monkey TRIM5α is essential for recognition of the retroviral capsid and for anti-HIV-1 activity (Stremlau et al., 2004; Perez-Caballero et al., 2005; Kar et al., 2008; Langelier et al., 2008). Moreover, the difference in the anti-HIV-1 potency of rhesus and human TRIM5α proteins is determined by variable regions within the B30.2(SPRY) domain (Song et al., 2005a; Sawyer et al., 2005; Perez-Caballero et al., 2005; Stremlau et al., 2005; Yap, Nisole and Stoye, 2005). The decreased potency of human TRIM5α in restricting HIV-1, for example, is due to the presence of arginine 332 in the v1 variable loop of the B30.2(SPRY) domain (Li et al., 2006; Yap, Nisole and Stoye, 2005). This arginine residue decreases the affinity of human TRIM5α for the HIV-1 capsid (Li et al., 2006). TRIM5α binding to the retroviral capsid has been shown to lead to accelerated capsid uncoating, a process facilitated by the TRIM5α RING and B-box 2 domains (Stremlau et al., 2006; Perron et al., 2007; Diaz-Griffero et al., 2007a, b; Diaz-Griffero et al., 2008; Li and Sodroski, 2008).

Interspecies differences in primate TRIM5α proteins dictate the potency of restriction against particular retroviruses (Hatziioannou et al. 2004; Keckesova, Ylinen and Towers, 2004; Song et al., 2005b; Stremlau et al., 2004, 2005; Yap et al. 2004a; Kratovac et al., 2008). Considerable intra-species variation in the TRIM5α proteins of primates has also been documented (Liao et al., 2007; Newman et al., 2008; Brenner et al., 2008; Virgen et al., 2008; Wilson et al., 2008). In most reported studies, common polymorphisms in the coding exons of human TRIM5 were not found to exert significant effects on the clinical progression of HIV-1 infection (Speelmon et al., 2006; Javanbakht et al., 2006; Goldschmidt et al., 2006; Sawyer et al., 2006; Nakayama et al., 2007; van Manen et al., 2008). One common nonsynonymous SNP (R136Q) exhibited an increased frequency among HIV-1-infected subjects relative to exposed seronegative persons, hinting that it may be linked to increased acquisition of infection (Speelmon et al., 2006). Moreover, some less common non-coding polymorphisms in African Americans have been associated with increases in susceptibility to HIV-1 infection (Javanbakht et al., 2006). The mechanism and importance of these potential regulatory polymorphisms require further investigation.

Here, we report the results of a survey of TRIM5 genotypes in indigenous Africans living in rural southeastern Cameroon, where HIV-1 infection in humans likely originated through contact with SIVcpz-infected chimpanzees (Gao et al., 1999; Nerrienet et al., 2005; Van Heuverswyn et al., 2007; Van Heuverswyn and Peeters, 2007; Santiago et al., 2002; Corbet et al., 2000; Keele et al., 2006). In Baka pygmies, we identify a rare TRIM5 allele that is predicted to encode a truncated TRIM5α protein defective for retrovirus restriction. The truncated TRIM5 variant exhibits dominant-negative effects on the wild-type TRIM5α protein. Thus, some African forest dwellers, whose lifestyle results in frequent exposure to chimpanzee and other non-human primate body fluids, may possess lower-than-normal TRIM5-mediated retrovirus restriction activity.

Material and Methods

Study population

Administrative and ethical approval to carry out this project was obtained from the Cameroon Ministry of Public Health and all the collaborating institutions. From 2001 to 2002, adult volunteers living in southeastern Cameroon rainforest villages (Figure 1) participated in a study of retrovirus molecular epidemiology. For the human genetics component of the study, a purposive choice sampling technique was used to select 95 Baka pygmies (hunter-gatherers) and 32 non-pygmies.

TRIM5 resequencing

The complete exon 8 of human TRIM5, which encodes the B30.2(SPRY) domain, was resequenced using the following primers: 5′ TCCCTTAGCTGACCTGTTAATTT-3′ and 5′-GCTGTACAGAAGGGGCTGAG-3′. Samples were resequenced using protocols provided by Applied Biosystems, and analyzed on an ABI-3730XL instrument.

Cells

Cf2Th canine thymic epithelial cells and 293T cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and propagated as recommended.

Plasmids

The wild-type TRIM5αhu cDNA was described previously (Stremlau et al., 2004), and corresponds to the major allelic variant in European Americans and African Americans (Javanbakht et al., 2006). The R332X mutation was introduced into the wild-type TRIM5 cDNA by PCR-directed mutagenesis. The TRIM5αhu proteins possess C-terminal epitope tags derived from either the influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) or the P and V proteins of simian virus 5 (V5).

Creation of cells stably expressing TRIM5 variants

A retroviral vector encoding the wild-type TRIM5αhu-HA protein was created using the pLPCX plasmid (Stratagene) (Stremlau et al., 2004). The pLPCX plasmid contains only the amino acid-coding sequence and not the untranslated region of the TRIM5α cDNA. Recombinant viruses were produced in 293T cells by cotransfecting the pLPCX plasmids with the pVPack-GP and pVPack-VSV-G packaging plasmids (Stratagene). The pVPack-VSV-G plasmid encodes the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) G envelope glycoprotein, which allows efficient entry into a wide range of vertebrate cells (Yee et al., 1994). Cf2Th cells stably expressing the wild-type TRIM5αhu-HA proteins were established by incubation of ~ 1 × 105 cells with recombinant virus in the presence of 5 μg/ml polybrene. Cells were selected in 5 μg/ml puromycin.

The R332X human TRIM5 protein with a V5 epitope tag was expressed using the Viral Power system (Invitrogen) (Diaz-Griffero et al., 2006). Recombinant lentiviruses were produced according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The resulting virus particles were used to transduce ~ 1 × 105 Cf2Th cells (or Cf2Th cells expressing wild-type TRIM5αhu-HA) in the presence of 5 μg/ml polybrene. Cells were selected in either 5 μg/ml blasticidin for cells expressing R332X TRIM5αhu-V5, or 5 μg/ml puromycin and 5 μg/ml blasticidin for cells expressing both wild-type and R332X TRIM5αhu proteins.

TRIM5 protein analysis

Cellular proteins were extracted with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mg/ml aprotinin, 2 mg/ml leupeptin, 1 mg/ml pepstatin A, 100 mg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (10% acrylamide), followed by blotting onto nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences). Detection of protein by Western blotting utilized monoclonal antibodies that are specifically reactive with the HA (Roche Applied Science) or V5 (Invitrogen) epitope tags. Detection of proteins was performed by enhanced chemiluminescence (PerkinElmer Life Sciences), using the following secondary antibodies obtained from Amersham Biosciences: anti-mouse (for V5) and anti-rat (for HA).

Co-localization experiments

Co-localization was studied as previously described (Javanbakht et al., 2005). Briefly, cells were grown overnight on 12-mm-diameter coverslips and fixed in 3.9% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Cellgro) for 30 minutes. Cells were washed in PBS, incubated in 0.1 M glycine (Sigma) for 10 minutes, washed in PBS, and permeabilized with 0.05% saponin (Sigma) for 30 minutes. Samples were blocked with 10% donkey serum (Dako, Carpentaria, CA) for 30 minutes and incubated for 1 hour with antibodies. The anti-HA fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated 3F10 antibody (Roche Applied Sciences) and anti-V5 Cy3-conjugated antibody (Sigma) were used to stain HA- or V5-tagged TRIM5α proteins, respectively. Subsequently, samples were mounted for fluorescence microscopy by using the ProLong Antifade Kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Images were obtained with a Bio-Rad Radiance 2000 laser scanning confocal microscope with Nikon 60X numerical aperture 1.4 optics.

Infection with viruses expressing green fluorescent protein

Recombinant viruses (HIV-1-GFP, N-MLV-GFP and B-MLV-GFP) expressing the humanized Renilla reniformis green fluorescent protein (GFP) were prepared as previously described (Perron et al., 2004; Stremlau et al., 2004). The viral stocks were quantified by measuring reverse transcriptase activity, as described previously (Rho et al., 1981). Cf2Th cells expressing the wild-type (wt) and R332X mutant TRIM5 proteins, or control Cf2Th cells transduced with the empty pLPCX vector, were incubated with various amounts of the recombinant viruses, as described (Perron et al., 2004; Stremlau et al., 2004). For infections, 3 × 104 Cf2Th cells seeded in 24-well plates were incubated with virus for 24 hours. Cells were washed and returned to culture for 48 hours, and then subjected to FACS analysis with a FACScan (Becton Dickinson).

Results

A human TRIM5 allele encoding a truncated protein

To examine the diversity of TRIM5 within a population of individuals in central Africa, genomic DNA was prepared from the PBMC of 127 subjects from Cameroon. This cohort included 95 Baka pygmies and 32 non-pygmies. The complete TRIM5 exon 8, which encodes the B30.2(SPRY) domain of TRIM5α, was resequenced. A rare mutation that specifies a premature stop codon (TGA) replacing the CGA codon for arginine 332 of TRIM5α was observed in four heterozygotes, all Baka pygmies from the same study site. Thus, 4.2 percent of the sampled Baka pygmies are heterozygous for this allele, with an allele frequency of 2.1 percent in this group. The allele is predicted to encode a truncated TRIM5α protein (R332X) missing 83% of the B30.2(SPRY) domain (Figure 2); the other TRIM5 isoforms, TRIM5γ and TRIM5δ, should not be affected by this mutation.

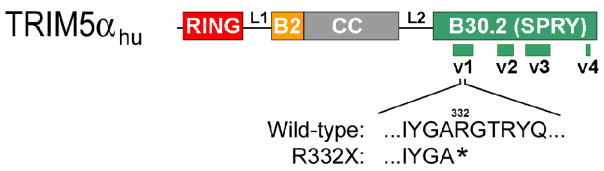

Figure 2. The TRIM5hu R332X protein.

The human TRIM5α protein is shown, with the domains and interdomain linkers (L1 and L2) labeled (B2 = B-box 2; CC = coiled coil). The variable (v1–v4) regions of the B30.2(SPRY) domain are shown. The predicted sequence of the carboxyl terminus of the TRIM5hu R332X protein is shown beneath the wild-type TRIM5αhu sequence.

Anti-retroviral activity of TRIM5hu R332X

The TRIM5α B30.2(SPRY) domain is essential for retrovirus restriction (Stremlau et al., 2004; Perez-Caballero et al., 2005). Furthermore, arginine 332 in the v1 variable region is a determinant of anti-HIV-1 potency (Li et al., 2006; Yap, Nisole and Stoye, 2005). These observations suggest that the truncated TRIM5hu R332X protein is probably defective for retrovirus inhibitory activity. To test this, Cf2Th canine thymic epithelial cells were established that express wild-type TRIM5αhu–HA, TRIM5hu R332X-V5, or both wild-type TRIM5αhu–HA and TRIM5hu R332X-V5. These proteins have C-terminal HA or V5 epitope tags. Two independent cell lines expressing both TRIM5 variants were established. Cf2Th cells were used for these experiments because dogs do not express a functional TRIM5 protein (Sawyer et al., 2007), thus allowing an assessment of the human TRIM5 phenotypes in a clean background. The wild-type TRIM5αhu protein was expressed at comparable levels in the control cells and in each of the independent clones in which TRIM5hu R332X-V5 was also expressed (Figure 3). The TRIM5hu R332X-V5 protein was expressed at higher levels in the control LPCX cells than in the cells expressing the wild-type TRIM5αhu–HA protein. The expression of the wild-type TRIM5αhu–HA protein may have decreased the efficiency of transduction of the cells by the lentivirus vector expressing TRIM5hu R332X-V5.

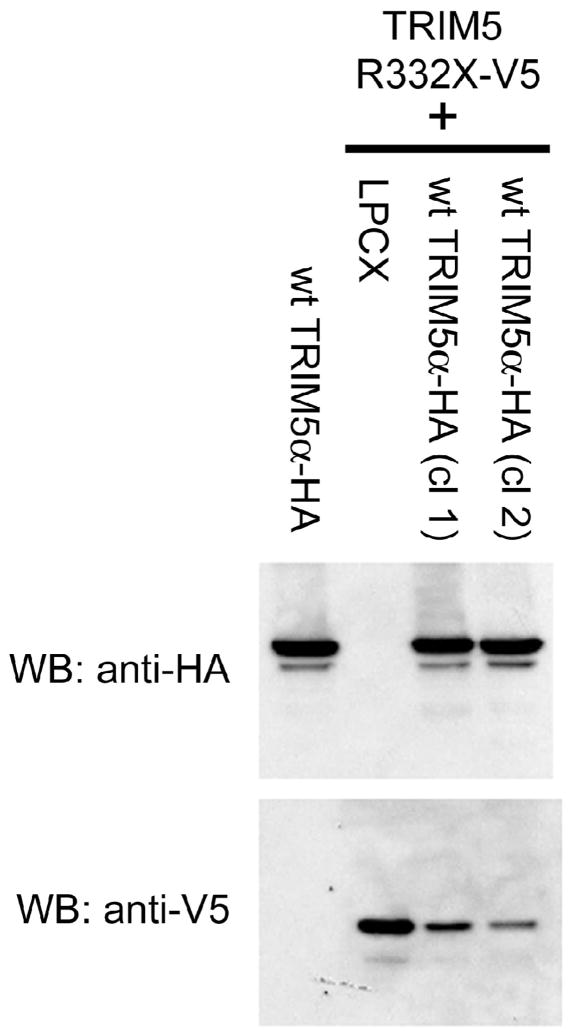

Figure 3. Expression of the human TRIM5 variants in canine epithelial cells.

Cf2Th cells were transduced with either the empty LPCX vector or the LPCX vector expressing wild-type (wt) TRIM5αhu-HA. Some of the cells were subsequently transduced with the gene encoding TRIM5hu R332X-V5 using the Viral Power system (Invitrogen). The results with two independent cultures (cl 1 and cl 2) of the Cf2Th cells coexpressing wt TRIM5αhu-HA and TRIM5hu R332X-V5 proteins are shown. Cell lysates were Western blotted and probed with antibodies directed against either the HA epitope tag (top panel) or the V5 tag (lower panel).

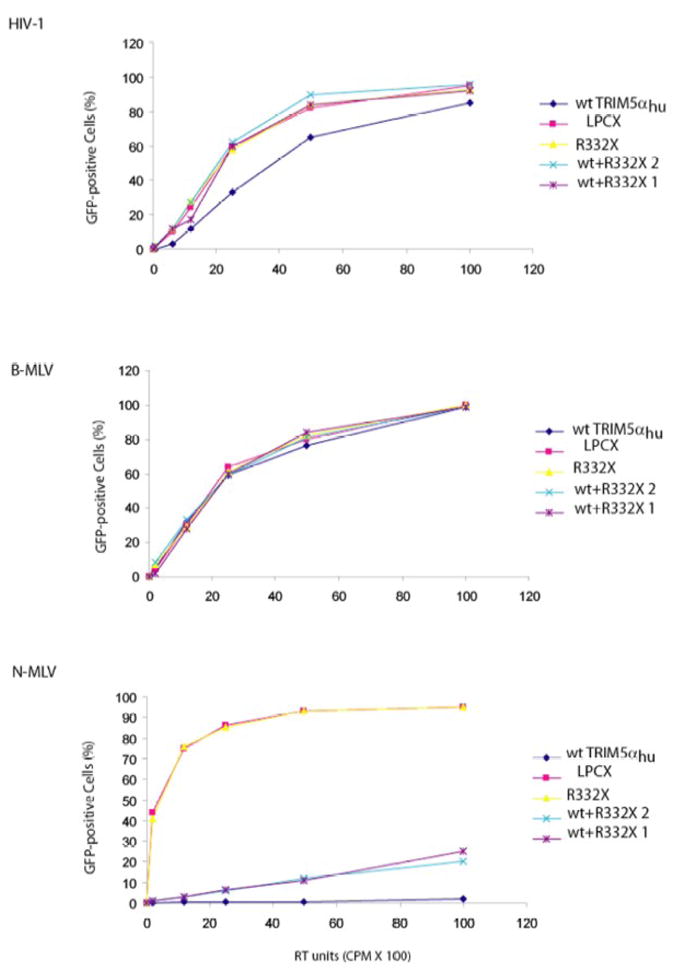

The susceptibility of the Cf2Th cells expressing the TRIM5hu variants to retrovirus infection was assessed. The cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of recombinant HIV-1, B-MLV and N-MLV expressing GFP. Forty-eight hours later, the level of infection achieved was assessed by FACS analysis (Figure 4). Relative to the control cells transduced with the empty LPCX vector, the cells expressing only wild-type TRIM5αhu were less infectible by HIV-1. This result is consistent with previous reports demonstrating that TRIM5αhu partially restricts HIV-1 infection (Stremlau et al., 2004, 2005; Perez-Caballero et al., 2005; Sawyer et al., 2005). By contrast, HIV-1 infection was not inhibited in cells expressing TRIM5hu R332X. Neither was HIV-1 infection affected in the cells expressing both wild-type TRIM5αhu and TRIM5hu R332X proteins. Apparently, the coexpression of TRIM5hu R332X diminishes the partial HIV-1-restricting ability of the wild-type TRIM5αhu protein.

Figure 4. Susceptibility of cells expressing human TRIM5 variants to retrovirus infection.

Cf2Th cells transduced with the empty LPCX vector or expressing the indicated TRIM5hu variants were incubated with various amounts of recombinant HIV-1, B-MLV or N-MLV expressing GFP. The results with two independent cultures (1 and 2) of the cells co-expressing the wt and R332X variants of TRIM5 are shown. Infected, GFP-positive cells were counted by FACS. The results of a typical experiment are shown. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

As expected (Perron et al., 2004; Hatziioannou et al., 2004; Keckesova et al., 2004; Yap et all, 2004), the cells expressing the wild-type TRIM5αhu protein were very resistant to N-MLV infection. No inhibition of N-MLV infection was observed for the TRIM5hu R332X protein. Compared with cells expressing only the wild-type TRIM5αhu protein, cells expressing both wild-type TRIM5αhu and TRIM5hu R332X proteins exhibited less restriction of N-MLV infection. Thus, for both N-MLV and HIV-1 infections, wild-type TRIM5αhu is a less efficient restriction factor when TRIM5hu R332X is co-expressed.

None of the TRIM5 variants tested here affected the efficiency of B-MLV infection. This indicates the specificity of the inhibitory effects observed for HIV-1 and N-MLV.

Co-localization and association of wild-type TRIM5 αhu and TRIM5hu R332X

The above results suggest that TRIM5hu R332X can exert some dominant-negative effects on retroviral restriction by wild-type TRIM5αhu. As both proteins retain all of the TRIM5 regions shown to be sufficient for dimerization (Javanbakht et al., 2006), we examined the colocalization and association of these TRIM5 variants. Wild-type TRIM5αhu and TRIM5hu R332X colocalized in the cytoplasm of cells coexpressing these proteins; the TRIM5 proteins exhibited a speckled pattern superimposed on a diffuse staining of the cytoplasm (Figure 5A). The wild-type TRIM5hu protein was coprecipitated with the TRIM5hu R332X-V5 protein in coexpressing cells (Figure 5B). Thus, the wild-type TRIM5αhu and TRIM5hu R332X proteins colocalize and associate, consistent with the observed dominant-negative effects.

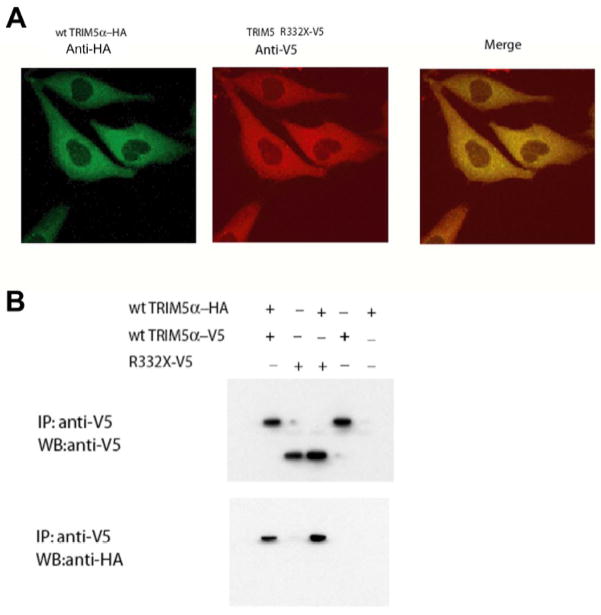

Figure 5. Association of TRIM5hu R332X and wild-type TRIM5αhu.

A. Cf2Th cells stably expressing wild-type TRIM5α hu-HA and TRIM5hu R332X-V5 were fixed and stained with a FITC-conjugated anti-HA antibody or a Cy3-conjugated anti-V5 antibody. Representative confocal microscopic images of the Cf2Th cells are shown. The merged image is shown in the right panel. B. 293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing the indicated TRIM5 variants containing either an HA or a V5 epitope tag. Cell lysates were precipitated (IP) with an anti-V5 antibody. The precipitates were then Western blotted (WB) with an anti-V5 antibody (upper panel) or an anti-HA antibody (lower panel).

Discussion

The existence of SIVcpz phylogenetically related to HIV-1 Group M in chimpanzees in Cameroon (Santiago et al., 2002; Gao et al., 1999; Keele et al., 2006; Nerrienet et al., 2005; Van Heuverswyn et al., 2007) supports the assertion that immunodeficiency viruses causing the global AIDS pandemic entered the human population in west central Africa. There, indigenous forest dwellers hunt and butcher non-human primates, including chimpanzees, and would thus be potentially exposed to retroviruses and other infectious agents in these animals. Here we report that approximately 4% of Baka pygmies are heterozygous for a rare allele (R332X) of TRIM5, which encodes one of the host barriers to cross-species transmission of retroviruses (Stremlau et al., 2004a; Hatziioannou et al., 2004; Keckesova et al., 2004; Perron et al., 2004; Yap et al., 2004; Song et al., 2005b). The presence of a stop codon in the TRIM5 R332X allele is predicted to result in the production of a TRIM5α variant that is truncated in the B30.2(SPRY) domain. This truncated TRIM5 protein lacks detectable antiretroviral activity and can exert a dominant-negative effect on the moderate HIV-1-restricting ability of the wild-type TRIM5α protein. The TRIM5 R332X allele has not been identified in previous surveys of African Americans or South Africans (Javanbakht et al., 2006), indicating that the distribution of this allele is limited. Null mutations in human TRIM5 are apparently rare, whereas a TRIM5 variant (H43Y) exhibiting modestly decreased antiretroviral activity is quite frequent in modern humans (Sawyer et al., 2006; Javanbakht et al., 2006). Species-wide disruption of TRIM5 has occurred in some mammals, such as dogs (Sawyer et al., 2007).

The observed phenotypes of TRIM5hu R332X are consistent with expectations based on numerous structure-function studies of TRIM5α proteins. TRIM5hu R332X is truncated within the v1 variable region of the B30.2(SPRY) domain, and therefore lacks most of the beta strands that contribute to the fold of this domain (Seto et al., 1999; Woo et al., 2006a, b; Yao et al., 2006; Grütter et al., 2006; James et al., 2007). The remnant of the B30.2(SPRY) domain in TRIMhu R332X is presumably folded into some non-native structure. TRIM5hu R332X thus lacks an intact capsid-binding domain, explaining its defectiveness in retroviral restriction (Stremlau et al., 2004; Perez-Caballero et al., 2005; Kar et al., 2008; Langelier et al., 2008).

TRIM5α forms dimers, allowing bivalent binding to the retroviral capsid (Javanbakht et al., 2006; Kar et al., 2008; Langelier et al., 2008). Because TRIM5hu R332X retains the coiled coil and L2 linker needed for oligomerization (Javanbakht et al., 2006), TRIM5hu R332X can form hetero-oligomers with wild-type TRIM5α. As these heterodimers have only one intact capsid-binding domain, the avidity for capsid is diminished compared with that of the wild-type TRIM5α dimer. Thus, as has been previously seen for TRIM5γ and other TRIM5 variants with deleted B30.2(SPRY) domains (Stremlau et al., 2004; Perez-Caballero et al., 2005), TRIM5hu R332X exhibits dominant-negative effects on retroviral restriction when coexpressed with wild-type TRIM5αhu.

Additional investigation will be required to assess the potential biological consequences of TRIM5 R332X heterozygosity. For example, the relative levels of expression of the wild-type TRIM5αhu and TRIM5hu R332X proteins in natural target cells would be expected to modulate the degree to which dominant-negative inactivation of wild-type TRIM5α function occurs. Although a previous study (Javanbakht et al., 2006) hinted that some regulatory changes in TRIM5 might affect HIV-1 susceptibility, whether functional decreases in TRIM5αhu antiretroviral activity resulting from TRIM5hu R332X expression could predispose to a higher risk of HIV-1 or SIVcpz infection is unknown. Because of the rarity of the TRIM5 R332X allele, it is not feasible to perform a case-control study to evaluate the effect of this polymorphism on susceptibility to HIV-1 infection. In addition to facilitating the cross-species transmission of SIVcpz from chimpanzees to humans, decreased TRIM5 function might also allow reinfection with HIV-1-like viruses, which promotes the generation of virus diversity through recombination. Indeed, diverse viruses from multiple clades and circulating recombinant forms of HIV-1 have been documented in the inhabitants of rural villages in the equatorial rain forest and grass field regions in Cameroon (Zhong et al., 2003; Konings et al., 2006). Future studies can explore the intriguing possibility that host genetic factors particular to the forest-dwelling peoples of west central Africa contributed to the initiation and evolution of HIV-1 infection in humans.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Yvette McLaughlin and Ms. Elizabeth Carpelan for preparation of the manuscript. This work has been supported, in part, by a Fellowship/Grant from the Fogarty International Center/USNIH: Grant # 2 D 43 TW000010-16 – AITRP; by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research; by the National Institutes of Health (AI063987, AI076094, AI067854 and a Center for AIDS Research Award AI060354); by the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative; by the Global Viral Forecasting Initiative; and by the late William F. McCarty-Cooper. This project has been funded in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U. S. Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allan JS, Short M, Taylor ME, Su S, Hirsch VM, Johnson PR, Shaw GM, Hahn BH. Species-specific diversity among simian immunodeficiency viruses from African green monkeys. J Virol. 1991;655:2816–2828. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.2816-2828.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apetrei C, Metzger MJ, Richardson D, Ling B, Telfer PT, Reed P, Robertson DL, Mars PA. Detection and partial characterization of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsm strains from bush meat samples from rural Sierra Leone. J Virol. 2005;79:2631–2636. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2631-2636.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayouba A, Souquieres S, Njinku B, Martin PM, Muller-Trutwin MC, Roques P, Barre-Sinoussi F, Mauclere P, Simon F, Nerrienet E. HIV-1 group N among HIV-1-seropositive individuals in Cameroon. AIDS. 2000;14:2623–2625. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200011100-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayouba A, Mauclere P, Martin PM, Cunin P, Mfoupouendoun J, Njinku B, Souquieres S, Simon F. HIV-1 group O infection in Cameroon, 1986–1998. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:466–467. doi: 10.3201/eid0703.010321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibollet-Ruche F, Bailes E, Gao F, Pourrut X, Barlow KL, Clewley JP, Mwenda J, Langat DK, Chege GK, McClure HM, Mpoudi-Ngole E, Delaporte E, Peeters M, Shaw GM, Sharp PM, Hahn BH. New simian immunodeficiency virus infecting De Brazza’s monkeys (Cercopithecus neglectus): evidence for a Cercopithecus monkey virus clade. J Virol. 2004;78:7748–7762. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.14.7748-7762.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieniasz PD. Restriction factors: a defense against retroviral infection. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11:286–291. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(03)00123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan G, Kozyrev Y, Hu SL. TRIMCyp expression in Old World primates Macaca nemestrina and Macaca fascicularis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3569–3574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709511105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Telfier P, Gettie A, Reed P, Zhang L, Ho DD, Marx PA. Genetic characterization of new West African simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsm: geographic clustering of household-derived SIV strains with human immunodeficiency virus type 2 subtypes and genetically diverse viruses from a single feral sooty mangabey troop. J Virol. 1996;70:3617–3627. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3617-3627.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Luckay A, Sodora DL, Telfer P, Reed P, Gettie A, Kanu JM, Sadek RF, Yee J, Ho DD, Zhang L, Marx PA. Human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) seroprevalence and characterization of a distinct HIV-1 genetic subtype from the natural range of simian immunodeficiency virus-infected sooty mangabeys. J Virol. 1997;71:3953–3960. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3953-3960.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbet S, Müller-Trutwin MC, Versmisse P, Delarue S, Ayouba A, Lewis J, Brunak S, Martin P, Brun-Vezinet F, Simon F, Barre-Sinoussi F, Mauclere P. env sequences of simian immunodeficiency viruses from chimpanzees in Cameroon are strongly related to those of human immunodeficiency virus group N from the same geographic area. J Virol. 2000;74:529–534. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.529-534.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courgnaud V, Abela B, Pournet X, Mpoudi-Ngiole E, Loul S, Delaporte E, Peeters M. Identification of a new simian immunodeficiency virus lineage with a vpu gene present among different cercopithecus monkeys (C. mona, C. cephus, and C. nictitans) from Cameroon. J Virol. 2003;77:12523–12534. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.23.12523-12534.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Griffero F, Li X, Javanbakht H, Song B, Welikala S, Stremlau M, Sodroski J. Rapid turnover and polyubiquitylation of the retroviral restriction factor TRIM5. Virology. 2006;349:300–135. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Griffero F, Kar A, Lee M, Stremlau M, Poeschla E, Sodroski J. Comparative requirements for the restriction of retrovirus infection by TRIM5α and TRIMCyp. Virology. 2007a;369:400–410. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Griffero F, Kar A, Perron M, Xiang S, Javanbakht H, Li H, Sodroski J. Modulation of retroviral restriction and proteasome inhibitor-resistant turnover by changes in the TRIM5(alpha) B-box 2 domain. J Virol. 2007b;81:10362–10378. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00703-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Griffero F, Perron M, McGee-Estrada K, Hanna R, Maillard P, Trono D, Sodroski J. A human TRIM5α B30.2/SPRY domain mutant gains the ability to restrict and prematurely uncoat B-tropic murine leukemia virus. Virology. 2008;378:233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F, Yue L, White AT, Pappas PG, Barchue J, Hanson AP, Greene BM, Sharp PM, Shaw GM, Hahn BH. Human infection by genetically diverse SIVsm-related HIV-2 in west Africa. Nature. 1992;358:495–499. doi: 10.1038/358495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F, Bailes E, Robertson DL, Chen Y, Rodenburg CM, Michael SF, Cummins LB, Arthur LO, Peeters M, Shaw GM, Sharp PM, Hahn BH. Origin of HIV-1 in the chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes. Nature. 1999;397:436–441. doi: 10.1038/17130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt V, Bleiber G, May M, Martinez R, Ortiz M, Telenti A. The Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Role of common human TRIM5alpha variants in HIV-1 disease progression. Retrovirology. 2006;22:54. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grütter C, Briand C, Capitani G, Mittl PR, Papin S, Tschopp J, Grütter MG. Structure of the PRYSPRY-domain: implications for autoinflammatory diseases. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn BH, Shaw GM, De Cock KM, Sharp PM. AIDS as a zoonosis: scientific and public health implications. Science. 2000;287:607–614. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatziioannou T, Cowan S, Goff SP, Bieniasz PD, Towers GJ. Restriction of multiple divergent retrovirus by Lv1 and Ref1. EMBO J. 2003;22:385–394. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatziioannou T, Perez-Caballero D, Yang A, Cowan S, Bieniasz PD. Retrovirus resistance factors Ref1 and Lv1 are species-specific variants of TRIM5alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10774–10779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402361101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Schubert D, LaBonte J, Munson L, Gibson S, Scammell J, Ferrigno P, Sodroski J. Species-specific, postentry barriers to primate immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 1999;73:10020–10028. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10020-10028.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James LC, Keeble AH, Khan Z, Rhodes DA, Trowsdale J. Structural basis for PRYSPRY-mediated tripartite motif (TRIM) protein function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6200–6205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609174104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javanbakht H, Diaz-Griffero F, Stremlau M, Si Z, Sodroski J. The contribution of RING and B-box 2 domains to retroviral restriction mediated by monkey TRIM5α. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26933–26940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502145200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javanbakht H, An P, Gold B, Petersen D, O’hUigin C, O’Brien S, Kirk G, Detels R, Goedert J, Buchbinder S, Donfield S, Shulenin S, Song B, Perron M, Stremlau M, Sodroski J, Dean M, Winkler C. Effects of human TRIM5α polymorphisms on antiretroviral function and susceptibility to human immunodeficiency virus infection. Virology. 2006;354:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly C, Phillips-Conroy JE, Turner TR, Broussard S, Allan JS. SIVagm incidence over two decades in a natural population of Ethiopian grivet monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops aethiops) J Med Primatol. 1996;25:78–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1996.tb00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar AK, Diaz-Griffero F, Li Y, Li X, Sodroski J. Biochemical and biophysical characterization of a chimeric TRIM21-TRIM5alpha protein. J Virol. 2008;82:11669–11681. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01559-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keckesova Z, Ylinen LM, Towers GJ. The human and African green monkey TRIM5alpha genes encode Ref1 and Lv1 retroviral restriction factor activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:107890–10785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402474101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keele BF, Van Heuverswyn F, Li Y, Bailes E, Takehisa J, Santiago ML, Bibollet-Ruche F, Chen Y, Wain LV, Liegeois F, Loul S, Ngole EM, Bienvenue Y, Delaporte E, Brookfield JF, Sharp PM, Shaw GM, Peeters M, Hahn BH. Chimpanzee reservoirs of pandemic and nonpandemic HIV-1. Science. 2006;313:523–526. doi: 10.1126/science.1126531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo Y, Mizokami M, Nakano T, Kato T, Ohba K, Orito E, Ueda R, Mukaide M, Hikiji K, Oyunsuren T, Cooksley WG. Genotype of GB virus C/hepatitis G virus by molecular evolutionary analysis. Virus Res. 1997;52:221–230. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(97)00123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konings FA, Haman GR, Xue Y, Urbanski MM, Hertzmark K, Nanfack A, Achkar JM, Burda ST, Nyambi PN. Genetic analysis of HIV-1 strains in rural eastern Cameroon indicates the evolution of second-generation recombinants to circulating recombinant forms. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:331–341. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000219784.81163.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratovac Z, Virgen CA, Bibollet-Ruche F, Hahn B, Bieniasz PD, Hatziioannou T. Primate lentivirus capsid sensitivity to TRIM5 proteins. J Virol. 2008;82:6772–6777. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00410-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiken C, Leitner T, Foley B, Hahn B, Marx P, McCutchan F, Wolinsky S, Korber B, editors. HIV Sequence Compendium 2008. Publisher: Los Alamos National Laboratory, Theoretical Biology and Biophysics; Los Alamos, New Mexico: 2008. LA-UR 08–03719. [Google Scholar]

- Langelier CR, Sandrin V, Eckert DM, Christensen DE, Chandrasekaran V, Alam SL, Aiken C, Olsen JC, Kar AK, Sodroski JG, Sundquist WI. Biochemical characterization of a recombinant TRIM5α protein that restricts HIV-1 replication. J Virol. 2008;82:11682–11694. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01562-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemey P, Pybus OG, Wang B, Saksena NK, Salemi M, Vandamme AM. Tracing the origins and history of the HIV-2 epidemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6588–6592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0936469100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemey P, Pybus OG, Rambaut A, Drummond AJ, Robertson DL, Roques P, Worobey M, Vandamme AM. The molecular population genetics of HIV-1 group O. Genetics. 2004;167:1059–1068. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.026666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Sodroski J. The TRIM5α B-box 2 domain promotes cooperative binding to the retroviral capsid by mediating higher-order self-association. J Virol. 2008;82:11495–11502. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01548-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Li X, Stremlau M, Lee M, Sodroski J. Removal of arginine 332 allows human TRIM5alpha to bind human immunodeficiency virus capsids and to restriction infection. J Virol. 2006;80:6738–6744. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00270-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao CH, Kuang YQ, Liu HL, Zheng YT, Su B. A novel fusion gene, TRIM5-Cyclophilin A in the pig-tailed macaque determines its susceptibility to HIV-1 infection. AIDS Suppl. 2007;8:S19–26. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304692.09143.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx PA, Li Y, Lerche NW, Sutjipto S, Gettie A, Yee JA, Brotman BH, Prince AM, Hanson A, Webster RG, Desrosiers RC. Isolation of a simian immunodeficiency virus related to human immunodeficiency virus type 2 from a West African pet sooty mangabey. J Virol. 1991;65:4480–4485. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.4480-4485.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama EE, Carpentier W, Costaghola D, Shioda T, Iwamoto A, Debre F, Yoshimura K, Autran B, Matsushita S, Theodorou I. Wild type and H43Y variant of human TRIM5alpha show similar anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity both in vivo and in vitro. Immunogenetics. 2007;59:511–515. doi: 10.1007/s00251-007-0217-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerrienet E, Santiago ML, Foupouapouognigni Y, Bailes E, Mundy NI, Njinku B, Kfutwah A, Muller-Trutwin MC, Barre-Sinoussi F, Shaw GM, Sharp PM, Hahn BH, Ayouba A. Simian immunodeficiency virus infection in wild-caught chimpanzees from Cameroon. J Virol. 2005;79:1312–1319. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.1312-1319.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman RM, Hall L, Kirmaier A, Pozzi LA, Pery E, Farzan M, O’Neil SP, Johnson W. Evolution of a TRIM5-CypA splice isoform in old world monkeys. PloS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000003. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njouom R, Pasquier C, Ayouba A, Gessain A, Froment A, Mfoupouendoun J, Pouillot R, Dubois M, Sandres-Sauné K, Thonnon J, Izopet J, Nerrienet E. High rate of hepatitis C virus infection and predominance of genotype 4 among elderly inhabitants of a remote village of the rain forest of South Cameroon. J Med Virol. 2003;71:219–225. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters M, Janssens W, Fransen K, Brandful J, Heyndrickx L, Koffi K, Delaporte E, Piot P, Gershy-Damet GM, van der Groen G. Isolation of simian immunodeficiency viruses from two sooty mangabeys in Côte d’Ivoire: virological and genetic characterization and relationship to other HIV type 2 and SIVsm/mac strains. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1994;10:1289–1294. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters M, Toure-Kane C, Nkengasong JN. Genetic diversity of HIV in Africa: impact on diagnosis, treatment, vaccine development and trials. AIDS. 2003;17:2547–2560. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000096895.73209.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Caballero D, Hatziioannou T, Yang A, Cowan S, Bieniasz PD. Human tripartite motif 5alpha domains responsible for retrovirus restriction activity and specificity. J Virol. 2005;79:8969–8978. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.8969-8978.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron MJ, Stremlau M, Song B, Ulm W, Mulligan RC, Sodroski J. TRIM5alpha mediates the postentry block to N-tropic murine leukemia viruses in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11827–11832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403364101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron MJ, Stremlau M, Lee M, Javanbakht H, Song B, Sodroski J. The human TRIM5alpha restriction factor mediates accelerated uncoating of the N-tropic murine leukemia virus capsid. J Virol. 2007;81:2138–2148. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02318-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reymond A, Meroni G, Fantozzi A, Merla G, Cairo S, Luzi L, Riganelli D, Zanaria E, Messali S, Cainaraca S, Guffanti A, Minucci S, Pelicci PG, Ballabio A. The tripartite motif family identifies cell compartments. EMBO J. 2001;20:2140–2151. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rho HM, Poiesz B, Ruscetti FW, Gallo RC. Characterization of the reverse transcriptase from a new retrovirus (HTLV) produced by a human cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cell line. Virology. 1981;112:355–360. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90642-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago ML, Rodenburg CM, Kamenya S, Bibollet-Ruche F, Gao F, Bailes E, Meleth S, Soong SJ, Kilby JM, Moldoveanu Z, Fahey B, Muller MN, Ayouba A, Nerrienet E, McClure HM, Henney JL, Pussy AE, Collins DA, Boesch C, Wrangham RW, Goodall J, Sharp PM, Shaw GM, Hahn BH. SIVcpz in wild chimpanzees. Science. 2002;295:465. doi: 10.1126/science.295.5554.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago ML, Range F, Keele BF, Li Y, Bailes E, Bibollet-Ruche F, Fruteau C, Noë R, Peeters M, Brookfield JF, Shaw GM, Sharp PM, Hahn BH. Simian immunodeficiency virus infection in free-ranging sooty mangabeys (Cercocebus atys atys) from the Taï Forest, Côte d’Ivoire: implications for the origin of epidemic human immunodeficiency virus type 2. J Virol. 2005;79:12515–12527. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12515-12527.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer SL, Wu LI, Emerman M, Malik HS. Positive selection of primate TRIM5alpha identifies a critical species-specific retroviral restriction domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2832–2837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409853102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer SL, Wu LI, Akey JM, Emerman M, Malik HS. High-frequency persistence of an impaired allele of the retroviral defense gene TRIM5alpha in humans. Curr Biol. 2006;16:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer SL, Emerman M, Malik HS. Discordant evolution of the adjacent antiretroviral genes TRIM22 and TRIM5 in mammals. PloS Pathog. 2007;3:e197. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto MH, Liu HL, Zajchowski DA, Whitlow M. Protein fold analysis of the B30.2-like domain. Proteins. 1999;35:235–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B, Gold B, O’hUigin C, Javanbakht H, Li X, Stremlau M, Winkler C, Dean M, Sodroski J. The B30.2(SPRY) domain of the retroviral restriction factor TRIM5α exhibits lineage-specific length and sequence variation in primates. J Virol. 2005a;79:6111–6121. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6111-6121.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B, Javanbakht H, Perron M, Park D, Stremlau M, Sodroski J. Retrovirus restriction by TRIM5α variants from Old World and New World primates. J Virol. 2005b;79:3930–3937. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.3930-3937.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souquière S, Bibollet-Ruche F, Robertson DL, Makuwa M, Apetrei C, Onanga R, Kornfeld C, Plantier JC, Gao F, Abernethy K, White LJ, Karesh W, Telfer P, Wickings EJ, Mauclère P, Mars PA, Barré-Sinoussi F, Hahn BH, Müller-Trutwin MC, Simon F. Wild Mandrillus sphinx are carriers of two types of lentivirus. J Virol. 2001;75:7086–7096. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.7086-7096.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speelmon EC, Livingston-Rosanoff D, Li SS, Vu O, Bui J, Geraghty DE, Zhao LP, McElrath MJ. Genetic association of the antiviral restriction factor TRIM5alpha with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 2006;80:2463–2471. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2463-2471.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stremlau M, Owens CM, Perron MJ, Kiessling M, Autissier P, Sodroski J. The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5alpha restricts HIV-1 infection in Old World monkeys. [See comment] Nature. 2004;427:848–853. doi: 10.1038/nature02343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stremlau M, Perron M, Welikala S, Sodroski J. Species-specific variation in the B30.2(SPRY) domain of TRIM5α determines the potency of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) infection. J Virol. 2005;79:3139–3145. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.3139-3145.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stremlau M, Perron M, Lee M, Yuan L, Song B, Javanbakht H, Diaz-Griffero F, Anderson DJ, Sundquist WI, Sodroski J. Specific recognition and accelerated uncoating of retroviral capsids by the TRIM5α restriction factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5514–5519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509996103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Switzer WM, Qari SH, Wolfe ND, Burke DS, Folks TM, Heneine W. Ancient origin and molecular features of the novel human T-lymphotropic virus type 3 revealed by complete genome analysis. J Virol. 2006;80:7427–7438. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00690-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomonaga K, Katahira J, Fukasawa M, Hassan MA, Kawamura M, Akari H, Miura T, Goto T, Nakai M, Suleman M, Isahakia M, Hayami M. Isolation and characterization of simian immunodeficiency virus from African white-crowned mangabey monkeys (Cerocebus torquatus lunulatus) Arch Virol. 1993;129:77–92. doi: 10.1007/BF01316886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Heuverswyn F, Li Y, Neel C, Bailes E, Keele BF, Liu W, Loul S, Butel C, Liegeois F, Bienvenue Y, Mpoudi Ngole E, Sharp PM, Shaw GM, Delaporte E, Hahn BH, Peeters M. SIV infection in wild gorillas. Nature. 2006;444:164. doi: 10.1038/444164a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Heuverswyn F, Peeters M. The origins of HIV and implications for the global epidemic. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2007;9:338–346. doi: 10.1007/s11908-007-0052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Heuverswyn F, Li Y, Bailes E, Neel C, Lafay B, Keele BF, Shaw KS, Takchisa J, Kraus MH, Loul S, Butel C, Liegeois F, Yangda B, Sharp PM, Mpoudi-Ngole E, Delaporte E, Hahn BH, Peeters M. Genetic diversity and phylogeographic clustering of SIVcpsPtt in wild chimpanzees in Cameroon. Virology. 2007;368:155–171. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen D, Rits MA, Beurgeling C, vanDort K, Schuitemaker H, Kootstra NA. The effect of Trim5 polymorphisms on the clinical course of HIV-1 infection. PloS Pathog. 2008;8:e18. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergne L, Bourgeois A, Mpoudi-Ngole E, Mougnutou R, Mbuagbaw J, Liegeois F, Lauren C, Butel C, Zekeng L, Delaporte E, Peeters M. Biological and genetic characteristics of HIV infections in Cameroon reveals dual group M and O infections and a correlation between SI-inducing phenotype of the predominant CRF02_AG variant and disease stage. Virology. 2003;310:254–266. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virgen CA, Kratovac Z, Bieniasz PD, Hatziioannou T. Independent genesis of chimeric TRIM5-cyclophilin proteins in two primate species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3563–3568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709258105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SJ, Webb BL, Ylinen LM, Verschoor E, Heeney JL, Towers GJ. Independent evolution of an antiviral TRIMCyp in rhesus macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3557–3562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709003105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe ND, Switzer WM, Carr JK, Bhullar VB, Shanmugam V, Tamoufe U, Prosser AT, Torimiro JN, Wright A, Mpoudi-Ngole E, McCutchan FE, Birx DL, Folks TM, Burke DS, Heneine W. Naturally acquired simian retrovirus infections in central African hunters. Lancet. 2004;363:932–937. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15787-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo JS, Imm JH, Min CK, Kim KJ, Cha SS, Oh BH. Structural and functional insights into the B30.2/SPRY domain. EMBO J. 2006a;25:1353–1363. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo JS, Suh HY, Park SY, Oh BH. Structural basis for protein recognition by B30.2/SPRY domains. Mol Cell. 2006b;24:967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worobey M, Gemmel M, Teuwen DE, Haselkorn T, Kunstman K, Bunce M, Muyembe JJ, Kabongo J-MM, Kalengayi RM, Van Marck E, Thomas M, Gilbert P, Wolinsky SM. Direct evidence of extensive diversity of HIV-1 in Kinshasa by 1960. Nature. 2008;455:661–664. doi: 10.1038/nature07390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao S, Liu MS, Masters SL, Zhang JG, Babon JJ, Nicola NR, Nicholson SE, Norton RS. Dynamics of the SPRY domain-containing SOCS box protein 2: flexibility of key functional loops. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2761–2772. doi: 10.1110/ps.062477806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap MW, Nisole S, Lynch C, Stoye JP. Trim5alpha protein restricts both HIV-1 and murine leukemia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10786–10791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402876101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap MW, Nisole S, Stoye JP. A single amino acid change in the SPRY domain of human TRIM5alpha leads to HIV-1 restriction. Curr Biol. 2005;15:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee JK, Friedmann T, Burns JC. Generation of high-titer pseudotyped retroviral vectors with very broad host range. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;43:99–112. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60600-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong P, Burda S, Konings F, Urbanski M, Ma L, Zekeng L, Ewane L, Agyingi L, Agwara M, Saa DR, Ze EA, Kinge T, Zolla-Pazner S, Nyambi P. Genetic and biological properties of HIV type 1 isolates prevalent in villagers of the Cameroon equatorial rain forests and grass fields: Further evidence of broad HIV type 1 genetic diversity. AIDS Research and Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19:1167–1178. doi: 10.1089/088922203771881284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]