Abstract

CCN2 is best known as a promoter of chondrocyte differentiation among the CCN family members, and Ccn2 null mutant mice display skeletal dysmorphisms. However, little is known concerning the roles of CCN2 during bone formation. We herein present a comparative analysis of wild-type and Ccn2 null mice to investigate the roles of CCN2 in bone development. Multiple histochemical methods were employed to analyze the effects of CCN2 deletion in vivo, and effects of CCN2 on the osteogenic response were evaluated with the isolated and cultured osteoblasts. As a result, we found a drastic reduction of the osteoblastic phenotype in Ccn2 null mutants. Importantly, addition of exogenous CCN2 promoted every step of osteoblast differentiation and rescued the attenuated activities of the Ccn2 null osteoblasts. These results suggest that CCN2 is required not only for the regulation of cartilage and subsequent events, but also for the normal intramembranous bone development.

Keywords: Connective tissue growth factor, Null mutant, Osteoblast, Differentiation, Intramembranous bone formation, CCN family

CCN2 is a member of the CCN (CCN1/Cyr61, CCN2/CTGF, and CCN3/NOV) family which also includes CCN4/WISP1, CCN5/WISP2, and CCN6/WISP3 [1–5]. Although physiological functions are not entirely clear, CCN2 is involved in a number of biological processes, promoting chemotaxis, migration, adhesion, proliferation, differentiation, and extracellular matrix formation [1–9]. Our previous studies have demonstrated the critical roles of CCN2 throughout the process of endochondral bone formation in vitro [1,4,10,11]. In addition, Ccn2 null mutant (CCN2-MT) mice have been shown to display an impaired endochondral bone formation [12].

We previously showed CCN2 to be highly expressed in hyperthrophic chondrocytes but only slightly expressed in cultured osteoblastic cells [13]. On the other hand, we also found that exogenous CCN2 promoted the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblastic cells in vitro [14]. Moreover, a recent study reported an expression of Ccn2 in normal long bones during the growth period and exogenous CCN2 elicited an osteogenic response in vivo [15,16], thus suggesting CCN2 plays an important role during the process of intramembranous bone development.

In this study, we report on a critical role of CCN2 in intramembranous bone formation, in addition to endochondral bone formation previously reported [1,4,10–13], by analyzing CCN2-MT mice in detail.

Materials and methods

Histological and immunohistochemical analysis

CCN2-MT mice were previously described [12]. CCN2-MT and WT mice at E15.5–18.5 were used. The samples from E16.5–18.5 were decalcified with 10% EDTA for 3–7 days, depending on their age. Masson Goldner staining, immunostaining for type I collagen and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), von Kossa staining and tartrate resistance acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining were performed on the 5 μm paraffin sections. Qualitative Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining with a substrate kit (Muto Chemical, Osaka, Japan) was performed on the 7 μm frozen sections. Mouse monoclonal antibodies against human type I collagen and human PCNA were purchased from Abcam Japan (Tokyo, Japan) and used at a 1:200 dilution. Antigen retrieval steps were performed for immunostaining; for collagen, digestion with 0.1% pepsin (Sigma) was performed at 37 °C for 30 min, while the sections were incubated at 96 °C for 30 min in 10 mM citrate for PCNA. We used Histofine Mouse Stain Kit (Nichirei Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan) containing the blocking reagent and secondary antibody. Positive signals were visualized by using 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride (DAB: Sigma). Finally, the sections were counterstained with Methyl Green Solution (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan). After staining, all sections were examined with a Motorized Microscope BX61 and a DP71 digital camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). All animal experiments in this study were conducted according to the Guidelines for Animal Research of the Okayama University and were approved by the Animal Committee.

Recombinant CCN2

Recombinant human CCN2 (rCCN2) produced by a HeLa cell clone was prepared as previously described [10]. Another rCCN2, a commercially available bacteria-derived rCCN2 (rCCN2bv) was obtained from Bio Vender Laboratory Medicine, Inc. (Heidelberg, Germany).

Cell isolation and culture condition

Murine osteoblasts were isolated from the calvariae of E18.5 embryos by digestion with 0.1% collagenase A (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for 1 h after the complete elimination of contaminating soft tissues by preliminary digestion with 0.25% trypsin for 30 min at 37 °C. The primary osteoblasts were inoculated at a density of 5 × 103/cm2 into culture dishes or multiplates (Greiner Japan, Tokyo, Japan) in α-MEM (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) supplemented with 10% FBS (SAFC Biosciences, Vic., Australia). These cells were cultured in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from WT or CCN2-MT osteoblasts in culture using RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Real-time PCR was performed as previously described [17]. RNA samples from 6 WT and 6 CCN2-MT littermates were examined. Primers are as follows: Gapdh (forward, 5′-GCCAAAAGGGTCATCATCTC-3′; reverse, 5′-GTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTGAT-3′); Col1a1 (forward, 5′-T GGCAAAGACGGACTCAAC-3′; reverse, 5′-GGCAGGAAGCTGAA GTCATAA-3′); Alp (forward, 5′-GGAATACGAATGAGAAGGCC-3′; reverse, 5′-CAGTTCAGTGCGGTTCCAGACATAG-3′); Osteocalcin (forward, 5′-CCATCTTTCTGCTCACTCTGCTGAC-3′; reverse, 5′-TA CCTTATTGCCCTCCTGCTTGGAC-3′).

Cell proliferation assay

For the evaluation of cell proliferation, the MTT method was employed. In this study, two days after the osteoblasts were seeded into 48-well plates, the FBS in the medium was reduced to 0.5%, and the cells were preincubated for 24 h and were further incubated in the same medium containing 10–100 ng/ml of both types of rCCN2, or an equal volume of 0.1% BSA–PBS control for 24 h. Thereafter, the lysate was analyzed by MTT assay, as previously described [18].

Evaluation of ALP activities

To estimate the ALP activity, both types of osteoblasts were grown to confluence in 48-well plates in regular α-MEM. Next, the concentration of FBS was reduced to 5% with the addition of 10–100 ng/ml of each rCCN2 or equal volume of 0.1% BSA– PBS control, as well as 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid. The cells were further cultured for 4 days, while the medium was replaced after 3 days. Thereafter, the enzyme activity of cell lysates was measured as previously described [14]. For the histochemical staining, several wells at the indicated time points were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde–PBS (PFA–PBS) at 4 °C for 10 min and were qualitatively stained as described above.

Skeletal preparations

E16.5 CCN2-MT embryo and WT littermate were stained to visualize skeletal elements. Samples were fixed overnight in 100% ethanol (EtOH). They were then stained overnight in 0.015% Alcian blue and 0.005% Alizarin red in 5% acetic acid/70% EtOH. Cleaning was performed in 1% KOH/20% glycerol. Thereafter, they were placed in 100% glycerol for photography.

Mineralization assay with alizarin red staining

Both types of osteoblasts in 48-well plates were grown to confluence in regular α-MEM. Next, the concentration of FBS was reduced to 5% with the addition of 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid and 50 or 100 ng/ml of rCCN2bv, or equal volume of 0.1% BSA–PBS control, and the cells were further cultured for 10 days, while the medium was replaced every 3 days. Thereafter, the cells were fixed with 4% PFA–PBS and were stained with Alizarin Red S Solution (Sigma) for 30 min at RT. The images were captured using a CanoScan D 2400U digital camera (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise specified, all experiments were repeated at least twice, and similar results were obtained. The data were analyzed using Student’s t-test. The results were expressed as means ± SD. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

CCN2 deletion caused reduction of bone matrix in the developing trabecular bones in vivo and down regulated Col1a1 expression in vitro

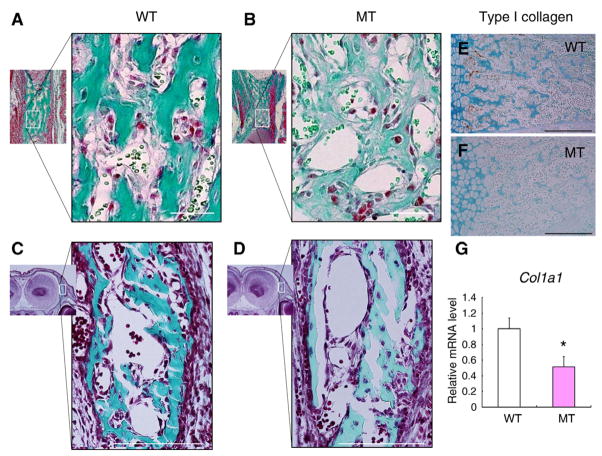

Typical deformation and hypogenesis in the ossified zone of the CCN2-MT embryos as revealed by histological observations are shown in Fig. 1A–F. Masson Goldner staining showed less developed trabecular bones in the CCN2-MT tibia (Fig. 1A and B) and in the CCN2-MT frontal bone (Fig. 1C and D). The WT tibia displayed intense immunoreactivity for type I collagen throughout the trabecular bone matrix in Fig. 1E, where the CCN2- MT tibia showed remarkably weaker immunoreaction (Fig. 1F). In the CCN2-MT osteoblasts, CCN2 deletion also caused reduction in Col1a1 mRNA expression down to 0.5-fold in comparison with to the WT osteoblasts (Fig. 1G).

Fig. 1.

Effect of CCN2 deletion on bone formation in vivo and Col1a1 expression in vitro. (A–D) Histological sections of tibiae at E16.5 (A,B) and coronal sections at E15.5 (C,D) stained by the method of Masson Goldner. (E,F) Immunostaining for type I collagen in the trabecular bones of tibiae at E18.5. (G) Col1a1 mRNA expression levels in wild-type (WT) and Ccn2 null mutant (MT) osteoblasts. Each column represents the mean ± SD of 4 samples from 4 littermates. *p < 0.01, significantly different from WT osteoblasts. Scale bar: 200 μm in (A), (B), (E), and (F); 500 μm in (C) and (D).

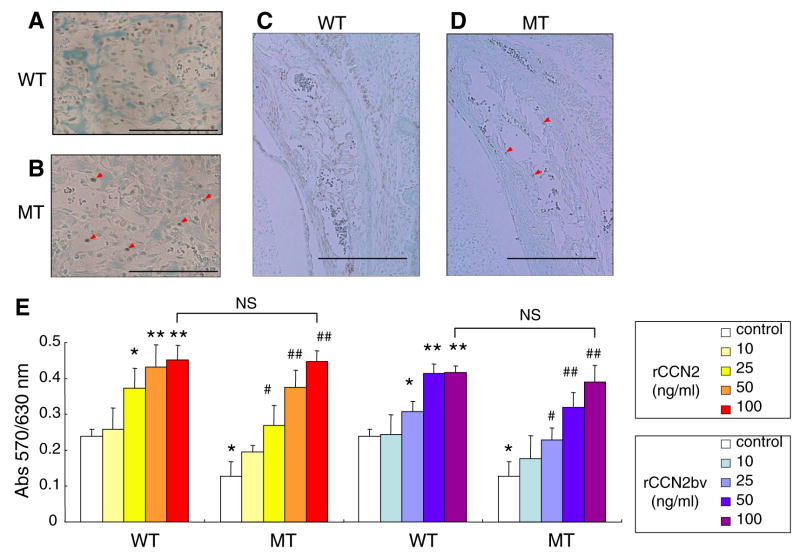

Reduced osteoblast proliferation in the CCN2-MT embryos and effect of exogenous rCCN2 on the proliferation in the both types of osteoblasts

Previous studies showed CCN2 promoted osteoblast proliferation in vitro [14,16]. Therefore, immunostaining for PCNA was employed in order to compare the proliferative activities between WT and CCN2-MT osteoblasts. The PCNA immunopositivity could be identified in the nuclei of almost all osteoblasts located within the trabecular bone in the WT tibia (Fig. 2A) and frontal bone (Fig. 2C). However, the CCN2-MT tibia and frontal bone contained quite few PCNA positive cells (Fig. 2B and D). Moreover, the effect of rCCN2 on proliferation was evaluated in both types of osteoblasts (Fig. 2E). Without an exogenous factor, proliferative activity of CCN2-MT osteoblasts exhibited approximately 50% less than that of WT osteoblasts (white columns in Fig. 2E). As expected, both rCCN2s promoted the proliferative activity, not only of the WT but also the CCN2-MT osteoblasts in a dose dependent manner. Of note, the proliferative activity of CCN2-MT osteoblasts recovered to the WT level with more than 25 ng/ml of rCCN2. At 100 ng/ml of rCCN2, CCN2-MT osteoblast proliferation was promoted as well as WT osteoblasts by both rCCN2s of different source. In WT osteoblasts, the maximal effect was observed at 50 ng/ml.

Fig. 2.

Effect of CCN2 deletion in vivo and addition of rCCN2s in vitro on the osteoblast proliferation. (A–D) Immunoreactivity for PCNA in developing tibial trabeculae at E18.5 (A,B) and frontal bones at E15.5 (C,D). Little immunoreaction is found in the MT mice (arrowheads in B and D). (E) Effect of both types of rCCN2 on osteoblast proliferation between WT and MT osteoblasts. Each column represents the mean ± SD of 8 samples from 8 littermates. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, significantly different from WT control. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 vs. MT control. NS, not significantly different. Scale bar: 200 μm in (A) and (B); 500 μm in (C) and (D).

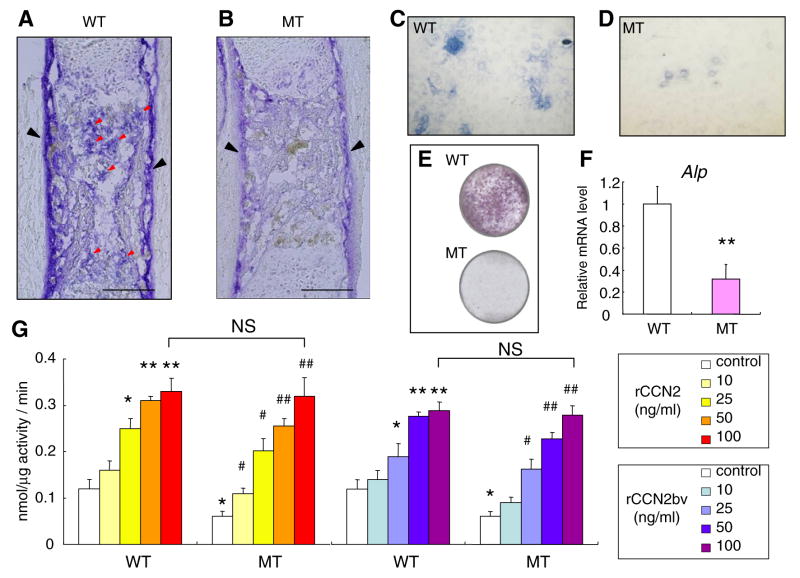

Reduced ALP activity in the CCN2-MT embryos and effect of exogenous rCCN2 on the ALP activity in both types of osteoblasts

To evaluate osteoblast maturation, ALP staining was performed on the both types of tibiae and osteoblasts. The cortical bones of WT tibiae and developing trabecular bones had intense signals for ALP activity was observed in (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the cortical bones of CCN2-MT tibia and the area of trabecular bones exhibited less staining and very little enzymatic reaction, respectively (Fig. 3B). WT osteoblasts showed stronger ALP activity than that of CCN2-MT osteoblasts at 2 days after (Fig. 3C and D) and 10 days after being seeded (Fig. 3E). In addition, CCN2 deletion also caused reduction of Alp mRNA expression down to 0.4-fold (Fig. 3F). The effects of both types of rCCN2 on ALP activity in both types of osteoblasts were also investigated. Both rCCN2s increased the enzymatic activity dose dependently, and maximal stimulation was observed at 50 ng/ml in the WT osteoblasts (Fig. 3G).

Fig. 3.

Effect of CCN2 deletion in vivo and addition of rCCN2s in vitro on the ALP activity of osteoblasts. (A,B) ALP staining of tibiae at E15.5. ALP activity in the cortical bone of MT tibia is much weaker than that of WT (black arrowheads in A and B). In developing trabecular bones, little enzymatic reaction is seen in MT tibia (B), though the intense ALP activity is observed in WT tibia (red arrowheads in A). (C,D) ALP staining of osteoblasts at 50% confluence (day 2). (E) ALP staining of osteoblasts (day 10). (F) The Alp mRNA expression at the same point as (E). (G) Effect of rCCN2 on ALP activity from the WT and MT osteoblasts. Each column represents the mean ± SD of 4 samples from 4 littermates. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, significantly different from WT control. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 vs. MT control. NS, not significantly different. Scale bar: 200 μm in (A) and (B).

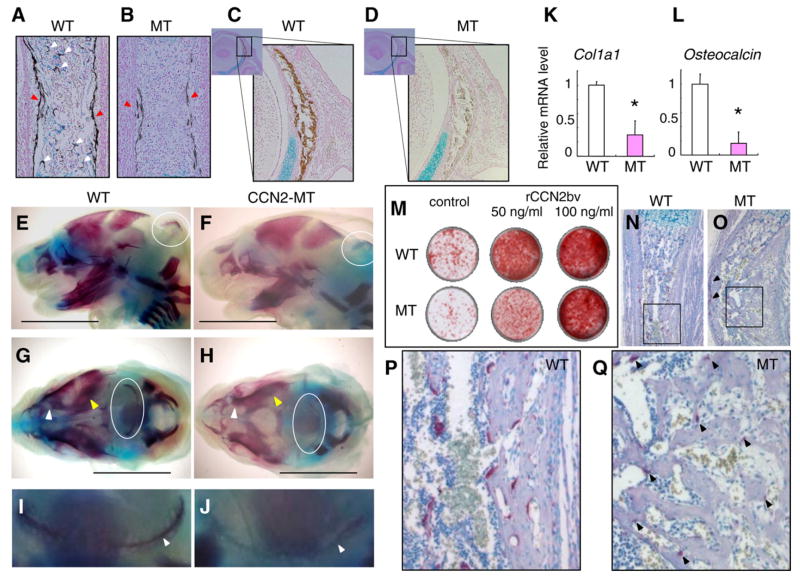

Delayed mineralization in the CCN2-MT embryo and effect of exogenous rCCN2 on the mineralization in both types of osteoblasts

To evaluate bone mineralization in each mouse, von Kossa staining was performed on the tibial and coronal sections (Fig. 4A–D). CCN2-MT cortical bones of tibia showed remarkably delayed mineralization (Fig. 4B). Although mineralized trabecular bones were observed in the WT tibia (Fig. 4A), no structure stained in brown was recognizable in the bone marrow area of the CCN2- MT tibia (Fig. 4B). The degree of mineralization in the frontal bone of the CCN2-MT mouse was also reduced (Fig 4C and D). An examination of skeletal preparations (Fig. 4E–J) demonstrated delayed ossification in the intramembranous skeletal elements of the CC2-MT mice. Both the frontal and parietal bones were properly mineralized in the WT mouse at this time point (Fig. 4G and H). However, interparietal bone mineralization was not clearly observed in the CCN2-MT embryo (Fig. 4E–J).

Fig. 4.

Delayed calcification in the CCN2-MT embryos in vivo, which was rescued by exogenous rCCN2 promoting osteoblastic mineralization in vitro. (A,B) Delayed mineralization in the MT tibia (B) compared to the WT (A) at E15.5 revealed by von Kossa staining. Mineralized cortical bones (red arrowheads in A and B). Mineralized structures can be seen in the bone marrow area of WT tibia (white arrowheads in A). (C,D) Frontal bone of MT embryo also shows delayed calcification at E15.5. (E–J) Skeletal staining in the alizarin red showed that mineralization of intramembranous bone elements of MT embryos were also delayed. (E,F) Lateral views of skulls at E16.5. (G,H) Superior views of skulls at E16.5. High magnification of the mineralized area of interparietal bone (I,J). Ossified areas of interparietal bones (in ovals in E–H, arrowheads in I and J). Frontal bones (white arrowheads) and parietal bones (yellow arrowheads in G and H). (K) Col1a1 mRNA expression levels at 10 days after confluence. (L) Osteocalcin mRNA expression levels at the same time point as in (K). (M) Effect of rCCN2bv on osteoblast mineralization at the same time point as (K) and (L). Representing mineral deposition visualized by alizarin red staining of both types of osteoblasts. (N–Q) TRAP staining of the both types of tibiae at E18.5. TRAP positive cells along with the cortical bones in MT tibia (arrowheads in O). (P,Q) High magnification of black box areas in (N) and (O). Quite weak reaction by TRAP is seen along with the trabecular bone in MT tibia (arrowheads in Q). Each column represents the mean ± SD of 4 samples from 4 littermates. *p < 0.01, significantly different from WT osteoblasts. Scale bar: 4 mm in (E–H).

Following the in vivo analyses, we evaluated the mRNA expression of Col1a1 and Osteocalcin at 17 days after calvarial osteoblasts were seeded. In the CCN2-MT osteoblasts, CCN2 deletion also caused the significant reduction of Col1a1 and Osteocalcin mRNA expression in comparison with WT osteoblasts (Fig. 4K and L). Alizarin red staining was performed at the same time point. The mineral deposition by the CCN2-MT osteoblasts was remarkably less than that of WT osteoblasts. This reduced mineralization by the CCN2-MT osteoblasts was excessively rescued by exogenous rCCN2 (Fig. 4M). In addition, we performed TRAP staining on both types of tibial sections. A previous report showed that TRAP positive cells were present at normal levels in the bone marrow of CCN2-MT mice, but at reduced levels along the cartilage- bone junction [12]. The number of TRAP positive cells in the CCN2-MT tibia was certainly at a normal level (Fig. 4N and O). However, the number of TRAP positive cells along with the cortical bone in the CCN2-MT mouse was reduced even though they were stained as well as in the WT tibia (Fig. 4O). In addition, TRAP positive cells along the trabecular bones in the CCN2-MT tibia demonstrated remarkably weaker staining (Fig. 4Q).

Discussion

We herein extended the analysis of the CCN2 function in skeletal development to reveal that CCN2 regulates bone formation, especially intramembranous bone. Our data demonstrated that the CCN2 deletion caused a remarkable reduction in bone matrix synthesis, osteoblast proliferation, maturation and mineralization in vivo. We also showed the osteogenic response in the calvarial osteoblasts from CCN2-MT mice to be significantly reduced in vitro. Suppressed proliferation and maturation of osteoblasts eventually delayed calcification, and delayed osteoclast maturation and recruitment were concomitantly observed. These findings indicate that CCN2 is required for normal osteoblast differentiation and subsequent events during skeletal development.

A previous study reported that CCN2-MT mice showed deformation of cartilage and kinks in bone and die within minutes of birth [12]. The kinks in bone have been believed to be due to abnormal endochondral bone formation as a result of impaired chondrocyte proliferation, ECM remodeling and the production of MMP and VEGF in growth plate. To analyze the morphological differences in detail, multiple histochemical methodologies were employed. As a result, the ossified area in the CCN2-MT mice was found to be significantly less developed than the WT littermates. In fact, CCN2 deletion caused significant reduction in type I collagen in bone matrix. CCN2 is known to stimulate the production of ECM components, such as collagens and fibronectins [6– 8]. Consistent with these previous reports, CCN2 was shown to play an important role as an inducer of bone matrices production during skeletal development. Furthermore, proliferative activity in CCN2-MT osteoblasts was impaired, and maturation and the initiation of mineralization were delayed in vivo and in vitro. These defects recovered by the addition of exogenous rCCN2 in vitro. In parallel with this investigation, we confirmed that CCN2 was produced in WT calvarial osteoblasts by immunohistochemical and immunoblot analyses in vivo and in vitro. Ccn2 mRNA was also detectable, and it showed differentiation stage-dependent changes in culture (manuscript in preparation). Consistent with these preliminary results, our present data clearly indicate that CCN2 is an essential mediator of osteoblast differentiation.

In summary, CCN2 is important not only for the regulation of endochondral bone formation but also for the normal intramembranous bone development. Recently, utility of CCN2 in bone regeneration therapy has been indicated [19]. The present study showing the requirement of CCN2 for the coordinated development of bones provides further rationale for employing CCN2 as a key factor in bone regeneration therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Takako Hattori, Takashi Nishida, for their helpful suggestions; Ms. Tomoko Yamamoto for technical assistance and Ms. Yuki Nonami for valuable secretarial assistance. This work was supported by Grants-in- Aid for Scientific Research (S) (to M.T.), (C) (to S.K.) and Exploratory Research (to M.T.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science. H.K. is a recipient of the Iwadare Scholarship from the Iwadare Educational Association for Dental Graduate Students.

References

- 1.Perbal B, Takigawa M. CCN Proteins: A New Family of Cell Growth and Differentiation Regulators. Imperial College Press; London: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brigstock DR. The CCN family: a new stimulus package. J Endocrinol. 2003;178:169–175. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1780169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lau LF, Lam SC. The CCN family of angiogenic regulators: the integrin connection. Exp Cell Res. 2000;248:44–57. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takigawa M, Nakanishi T, Kubota S, Nishida T. Role of CTGF/HCS24/ecogenin in skeletal growth control. J Cell Physiol. 2003;194:256–266. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perbal B. CCN proteins: multifunctional signalling regulators. Lancet. 2004;363:62–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grotendorst GR, Duncan MR. Individual domains of connective tissue growth factor regulate fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation. FASEB J. 2005;19:729–738. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3217com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leask A, Abraham DJ. TGF-beta signaling and the fibrotic response. FASEB J. 2004;18:816–827. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1273rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wahab NA, Mason RM. Connective tissue growth factor and renal diseases: some answers, more questions. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2004;13:53–58. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200401000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimo T, Kubota S, Yoshioka N, Ibaragi S, Isowa S, Eguchi T, Sasaki A, Takigawa M. Pathogenic role of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) in osteolytic metastasis of breast cancer. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1045–1059. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakanishi T, Nishida T, Shimo T, Kobayashi K, Kubo T, Tamatani T, Tezuka K, Takigawa M. Effects of CTGF/Hcs24, a product of a hypertrophic chondrocyte-specific gene, on the proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes in culture. Endocrinology. 2000;141:264–273. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.1.7267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishida T, Kubota S, Nakanishi T, Kuboki T, Yosimichi G, Kondo S, Takigawa M. CTGF/Hcs24, a hypertrophic chondrocyte-specific gene product, stimulates proliferation and differentiation, but not hypertrophy of cultured articular chondrocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2002;192:55–63. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivkovic S, Yoon BS, Popo SN, Safadi FF, Libuda DE, Stephenson RC, Daluiski A, Lyons KM. Connective tissue growth factor coordinates chondrogenesis and angiogenesis during skeletal development. Development. 2003;130:2779–2791. doi: 10.1242/dev.00505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakanishi T, Kimura Y, Tamura T, Ichikawa H, Yamaai Y, Sugimoto T, Takigawa M. Cloning of a mRNA preferentially expressed in chondrocytes by differential display-PCR from a human chondrocytic cell line that is identical with connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) mRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;234:206–210. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishida T, Nakanishi T, Asano M, Shimo T, Takigawa M. Effects of CTGF/Hcs24, a hypertrophic chondrocyte-specific gene product, on the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblastic cells in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 2000;184:197–206. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200008)184:2<197::AID-JCP7>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu J, Smock SL, Safadi FF, Rosenzweig AB, Odgren PR, Marks SC, Jr, Owen TA, Popo SN. Cloning the full-length cDNA for rat connective tissue growth factor: implications for skeletal development. J Cell Biochem. 2000;77:103–115. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(20000401)77:1<103::aid-jcb11>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Safadi FF, Xu J, Smock SL, Kanaan RA, Selim AH, Odgren PR, Marks SC, Jr, Owen TA, Popo SN. Expression of connective tissue growth factor in bone: its role in osteoblast proliferation and differentiation in vitro and bone formation in vivo. J Cell Physiol. 2003;196:51–62. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yanagita T, Kubota S, Kawaki H, Kawata K, Kondo S, Takano-Yamamoto T, Tanaka S, Takigawa M. Expression and physiological role of CCN4/Wnt-induced secreted protein 1 mRNA splicing variants in chondrocytes. FEBS J. 2007;274:1655–1665. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubota S, Kawaki H, Kondo S, Yosimichi G, Minato M, Nishida T, Hanagata H, Miyauchi A, Takigawa M. Multiple activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by purified independent CCN2 modules in vascular endothelial cells and chondrocytes in culture. Biochimie. 2006;88:1973–1981. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ono M, Kubota S, Fujisawa T, Sonoyama W, Kawaki H, Akiyama K, Oshima M, Nishida T, Yoshida Y, Suzuki K, Takigawa M, Kuboki T. Promotion of attachment of human bone marrow stromal cells by CCN2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]