Marked changes in ownership and control have occurred in substance abuse treatment delivery since the 1990s (Horgan, 2001; Weisner & Schmidt, 2001). Although outpatient substance abuse treatment (OSAT) is still dominated by organizations under private nonprofit control, a growing proportion of OSAT facilities are now investor-owned, for-profit providers. Between 1988 and 2005, the percentage of private nonprofit OSAT units decreased from 64% to 53% nationally, whereas the percentage of private for-profit OSAT units increased from 10% to 22% (National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey [NDATSS], 2005). In 1995, less than 10% of outpatient methadone-maintenance patients received care at for-profit facilities. Ten years later, for-profit facilities served 34% of OSAT methadone patients (NATSS, 2005; Sloan, 2005; Solomon, 2002).

These changes mark the steady proliferation of private for-profit providers within a treatment system historically controlled by independent, private nonprofit and public institutions. To some observers, the shift from a nonprofit community structure to one more explicitly influenced by financial incentives generates concern for the public good (Anspaugh, 1997; Friedmann et al. 2003; Horwitz, 2005; Stevens, 1989; Wheeler, Fadel, & D'Aunno, 1992; Wheeler & Nahra, 2000).

Specifically, the increased presence of private for-profit providers raises concerns about how the organizational objective of profit maximization impacts treatment systems. Some believe these changes may engender an even deeper schism in the already two-tiered private/public system of care based on a client's ability to pay (IOM, 1990). It has been argued, for example, that the OSAT system dominated by private nonprofit providers emerged, in part, as a response to agency concerns. On this account, nonprofit suppliers with missions that foster a sense of trustworthiness and public commitment arise in sensitive arenas of service delivery, often in the absence of both for-profit and government activity (Arrow, 1963; Hansmann, 1987; Hirth, 1999).

The basis for these expected differences between public and private nonprofit organizations, on the one hand, and the private for-profit firm, on the other, is linked to legal proscriptions against the distribution of profits to stake-holders. Removing the immediate profit motive from public and private nonprofit organizations is designed to eliminate or dampen “incentives for managers to engage in activities that promote private interests at the expense of social welfare objectives” (Heinrich & Fournier, 2004, p. 50).

To promote this social or public-good orientation, these organizations receive exemption from income and property taxes. It is expected, in return, that public and private nonprofit units will more readily provide treatment accessibility to the indigent and underinsured.

Despite a line of research and policymaking that regards nonprofits as more likely than for-profit OSAT providers to advance the public good, the available body of empirical research is limited regarding the conduct and performance of nonprofit providers. The response of nonprofit OSAT providers to market forces and to increased competition from for-profit competitors has also attracted widespread attention though little systematic empirical research.

Some commentators have argued that fewer differences exist between private nonprofit providers and private for-profit providers than early theorists presumed (Frank & Salkever, 2000; Sloan, 2000). Others speculate that private nonprofit providers may be losing their public-good orientation as they become more fiscally motivated (Anspaugh, 1997; Schneller, 1997).

To address these questions, this study evaluates how treatment accessibility is influenced by ownership in OSAT units. Using a nationally representative study of OSAT units, we examine how ownership affects access and retention across three sample waves in 1995, 2000, and 2005. Treatment access is conceptualized as the willingness of a unit to remove or ease financial barriers to treatment and is measured by the percentage of clients treated who are unable to pay for their treatment. Treatment retention is assessed by the willingness of a unit to continue treatment despite a client's financial situation and is measured by the percentage of clients receiving shortened treatment because of their inability to pay.

With this work, we hope to provide empirical evidence about how treatment accessibility, especially for those with limited financial resources, may be influenced by shifting ownership structure within the OSAT sector. Better understanding of the relationship between ownership and aspects of treatment accessibility may help shape policy decisions for the distribution of federal, state, and local support for low-income substance users. For example, federal efforts, such as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's Access to Recovery initiative, focus on improving treatment accessibility through the use of vouchers for millions of substance users in need of treatment (SAMSHA, 2007). Understanding patterns of treatment accessibility and retention helps inform the national dialogue and helps better direct limited federal funds.

Results in our article may also inform state and federal regulatory policies, for example, to scrutinize arguments for favored tax treatment of nonprofit providers (Horwitz, 2006; Schlesinger & Gray, 2006). This analysis is especially timely, giventhe increased marketpenetrationoffor-profitOSATcare.

1. Background

The shift toward OSAT privatization is comparable to that occurring throughout the general health care sector. From the early 1960s and throughout the 1970s, public and nonprofit providers funded by federal resources dominated the substance abuse delivery system. During the mid-1970s and throughout the 1980s, the public sector entered a phase of declining relative resources as public funding was diverted from treatment toward criminal justice interventions and prevention among nonusers (IOM, 1990).

Although the public tier experienced constrained resources, the private segment emerged during the 1980s, aided by societal shifts in attitudes pertinent to OSAT care. The stigma associated with substance abuse treatment decreased as the effectiveness of treatment became more widely known. In turn, consumers and mental health professionals advocated for parity of behavioral health care coverage. Although such parity was not fully realized, advocates encouraged employers to offer more comprehensive health care benefits that included OSAT care (IOM, 1997; Weisner & Schmidt, 2001). Fueled by this demand, private financing for behavioral health care evolved, and private for-profit organizations increased their presence in the management and delivery of care ( Findlay, 1999; IOM, 1997; Weisner & Schmidt, 2001).

The saliency of these market changes stems from the relationship between ownership type and organizational objectives (Wheeler, Fadel, & D'Aunno, 1992). Along one end of the theoretical continuum, private for-profit firms maximize the wealth of their owners and may distribute profits to shareholders. At the other end, public firms serve the community and promote provision of public goods. Somewhere between the two extremes, private nonprofit firm advances social and private objectives within a private framework (Hansmann, 1987a; Weisbrod, 1988). Private nonprofit and public organizations are encouraged to pursue their mission of social welfare with income and property tax exemptions. This literature is most highly developed in the context of hospital care. However, these general arguments are also applied within other arenas of social services and medical care (Horwitz, 2005).

The increased presence of for-profit providers has led both policymakers and researchers to question how the organizational objective of profit maximization impacts the OSAT care system. Some believe there will be a deeper schism in the already two-tiered private/public system of care based on a client's ability to pay (IOM, 1990). An extension of this debate focuses on the vulnerability of the substance user. The complexities of health care make it difficult for clients to judge the appropriateness and quality of treatment. Given increased competition and financial pressures in the health care industry, for-profit providers may have little incentive to provide adequate levels of care to indigent and vulnerable populations, which often have concomitant medical, social, legal, and financial burdens (Hansmann, 1987al; Lee, Reif, Ritter, Levine, & Horgan, 2001). Further, some scholars speculate that nonprofit providers may be abandoning their social mission as they become more fiscally motivated in response to market forces and possibly increased competition from for-profit providers (Anspaugh, 1997; BNA Health Law Reporter, 2004; Horwitz, 2003; Schneller, 1997).

The trend toward OSAT privatization, especially the growth of private for-profit firms, is of particular significance for its potential impact on treatment activity, availability, effectiveness, and innovation (Fadel, 1993; Friedmann, Alexander, & D'Aunno, 1999; Heinrich & Fournier, 2004; Horgan, 2001; Jaffe, 1984; Mechanic, 1999; Price, D'Aunno, & Burke, 1985; Weisner & Schmidt, 2001). Prior research has shown that differences in OSAT ownership are associated with differences in funding sources, clientele, and treatment practices (D'Aunno & Pollack, 2002; Friedmann et al., 1999; Rodgers & Barnett, 2000; Wheeler & Nahra, 2000). Private for-profit organizations have shown to achieve higher levels of financial performance, charge higher prices, outpace other units in operational efficiency, and serve clients with fewer comorbidities and clients with private insurance or the ability to pay out of pocket (Alexander & Wheeler, 1998; Wheeler, Fadel, & D'Aunno, 1992; Wheeler & Nahra, 2000). Friedmann et al. (1999) demonstrated that for-profit units are also less likely than public units to offer mental health and primary care services to outpatient substance abuse clients.

The treatment of uninsured or underinsured clients is of particular importance to OSAT units, which have been burdened by closures and mergers (Wells et al., 2007). However, survival of these units also depends on their ability to remain financially solvent as public funding is reduced and managed care pressures increase ( Galanter et al., 2000; Weisner & Schmidt, 2001; Wells, Lemak, Alexander, Roddy, & Nahra, n.d.).

Meanwhile, survey data indicate that many individuals experience financial barriers to OSAT care. Almost 20 million persons who needed treatment for substance use disorder did not receive treatment in the past year. For those who felt they needed but did not receive treatment at a specialty facility, 35% reported cost and insurance barriers, 14% were unsure how to access treatment, and 13.4% stated other access barriers including no program openings. Other reasons for not accessing the treatment system included stigma associated with receiving treatment and not being prepared to decrease or stop using.

Other research shows that select populations may be particularly vulnerable to treatment accessibility. One study by Pollack and Reuter (2006) illustrates that welfare receipt is an important predictor of treatment access among low-income women with substance use disorders. Policies such as the 1996 welfare reform, which allowed states to tighten requirements for welfare receipt, may thus create additional obstacles to the identification and treatment of low-income individuals with substance use disorders (Metsch & Pollack, 2005; Pollack & Reuter, 2006).

In their 2001 study, Wells et al. document that race and ethnicity may shape treatment accessibility for drug and alcohol abuse treatment and for mental health care. This research shows that there is more delay in receiving care and more unmet need for behavioral health care among African Americans and Hispanic/Latinos, relative to Whites (Wells et al., 2001).

Deck et al. (2006) observed changes in accessibility when modifications to Oregon Medicaid restricted substance abuse treatment. They found that opiate users presenting for publicly funded treatment after the policy change were less than half as likely to be placed in an opiate treatment program compared to the prior year. The impact of Medicaid-managed care programs, some of which are fully capitated, on care access is less consistent (Maglione & Ridgely, 2006).

This study uses data from three waves of the NDATSS to examine how ownership and other organizational and environmental factors in outpatient substance abuse are related to treatment accessibility.

2. Modeling the influence of ownership on treatment access

Two dependent variables are examined in our analysis to reflect the extent to which units (a) enable initiation and (b) provide continuation of treatment for clients without financial resources. Limiting initial access to the treatment facility may be one way that a unit attempts to create a more stable flow of revenues. Some clients are reimbursed at levels below average variable cost but above marginal cost. These patients contribute to OSAT profits (as long as their care does not affect revenues from other patients), although they are apparent money losers. Those who require essentially free care are truly those one would expect to be denied service by an OSAT provider focused primarily on profits. Another path to limit treatment access may be to reduce a prescribed treatment program because of a client's financial standing. This strategy may be employed by units to reduce the financial risks associated with serving this high-risk population.

In addition to assessing treatment accessibility in relation to ownership status, we also examine other organizational features, client characteristics, and environmental conditions that may influence the ability for a unit to undertake clients with financial limitations.

Because these OSAT organizations have limited resources, they must balance open accessibility for indigent population and financial survival. Organizations that are affiliated with hospitals or mental health centers may have more financial support over the long run than those organizations that are independently owned.

The demand of a more diverse and clinically complex caseload may further strain an organization and limit its ability or willingness to care for needy and uninsured clients. Previous research has shown that particular client characteristics are associated with more complex and resource-intensive treatment needs. Some racial and ethnic minorities, such as clients who are African American or Hispanic/Latino, experience disproportionate rates of social, economic, and health status disadvantages (Grella & Stein, 2006; Seale, 1993; Wells et al., 2001). Clients who are unemployed may pose another source of financial risk because they are less likely to have adequate insurance coverage or access to resources that may assist the treatment process. Clients with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders, as well as those who have undergone prior treatment, often present with greater case complexity and require a greater range or intensity of treatment services (Harris & Edlund, 2005; Wu, Ringwalt, & Williams, 2003).

Other financial and environmental pressures may influence the ability of treatment units to provide broad treatment accessibility to the uninsured. Public and private payors have increased their efforts to control the burgeoning costs of behavioral health care by reducing reimbursement rates or by restricting payment to particular services. Further, payors have limited provider cost-shifting and have thus reduced financial leeway in these organizations for cross-subsidization strategies to foster treatment accessibility for indigent patients (Horowitz, 2005; Schlesinger & Gray, 2006).

Managed care agreements often impose treatment guidelines or restrictions that must be followed by the unit to receive payment for services provided (Alexander, Lemak, & Campbell, 2003). The financial constraints imposed by managed care organizations also have been associated with reduced access in OSAT care (Alexander, Nahra, & Wheeler, 2003). In addition to managed care constraints, public funding sources, such as Medicaid, continue to pressure behavioral health care organizations to operate under tighter margins (McCarty, Frank, & Denmead, 1999).

Competition may also affect how a unit responds to providing access to an indigent population. In some cases, external competition has been shown to improve organizational efficiency (Feldstein, 1993), thereby increasing available resources to care for the indigent. At the same time, providers in a market may reduce or even abandon care for the uninsured and underinsured as they place greater priority on responding to competitive pressures.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and data collection

Data were from OSAT units surveyed in 1995, 1999/ 2000, and 2005 as part of the NDATSS. NDATSS is a longitudinal study of OSAT units conducted by the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan. The study focuses on organizational structure, operating characteristics, and treatment modalities in OSAT care. In NDATSS, an OSAT unit is defined as a physical facility with resources dedicated primarily (at least 50%) to treating individuals with substance abuse problems on a nonresidential basis.

Details of sampling, study design, and methods used in the NDATSS have been described elsewhere (Adams, 2001; Adams, 2005; Heeringa, 1996). Briefly, NDATSS uses a mixed panel design, which combines elements from panel and cross-sectional design formats (Adams, 2001; Adams, 2005; Heeringa, 1996). Data are collected from the same national sample of OSAT units that have been sampled and screened as part of prior waves of the study. These panel units are combined with a new group of randomly selected OSAT units to ensure that the sample remains nationally representative.

For each specific wave, the new units added to the panel are selected for participation from a sampling frame of the nation's OSAT units. This sample frame is updated and compiled by the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan. After screening and nonresponse, 618 organizations completed interviews in 1995, with an 88% response rate; 745 organizations completed interviews in 2000, with an 89% response rate; and 566 units completed interviews in 2005, with an 88% response rate. In this analysis, the units across the 1995, 2000, 2005 waves are combined for a pooled sample size of 1929 OSAT units.

Several steps were followed to produce reliable and valid telephone survey data, including several pretests for each wave of data collection, elaborate interview training and survey modifications, extensive checks for consistency within and between sections of the survey instrument, and as necessary, recontacts with respondents were made for clarification (Groves, 1988).

Unit directors and clinical supervisors of each participating OSAT unit were asked to complete the telephone interviews. Directors provided data concerning the unit's ownership status, environment, finances, affiliation with other organizations, and managed care arrangements. Clinical supervisors provided information about staff, client characteristics, treatment practices, and ancillary services. After data were collected, extensive reliability checks were performed within and between the two unit surveys.

4. Measures

4.1. Dependent variables

This study considers two variables that reflect a unit's willingness to endure financial risks associated with providing access and sustainable treatment duration for clients who are either uninsured or underinsured. The first dependent variable, reflecting treatment accessibility, is the percentage of clients who have no public or private insurance and who are unable to pay for treatment. The second dependent variable is the percentage of clients in the fiscal year prior to survey interview receiving shortened treatment because of client inability to pay. Both variables are estimates made by the director of the unit for the most recent fiscal year prior to survey interview.

4.2. Predictor variables

Ownership status of the unit is identified as either public, private nonprofit, or private for-profit. Two dummy variables, public and private nonprofit, represent ownership in the model, with private for-profit status as the referent.

Affiliation indicates whether a unit is operated as an independent entity or if it is affiliated with a parent organization. Affiliation may be with a hospital or medical center, a mental health organization, or some other behavioral health care provider. Three dummy variables capture organizational affiliations: hospital affiliation, mental health affiliation, or freestanding, with “other” affiliation as the referent category.

Methadone maintenance modality is measured by a single dummy variable indicating program participation in this treatment protocol.

Five variables measured at the unit level are used to capture aspects of client composition and case complexity: percentage of clients who are (a) African American; (b) Hispanic/Latino1; (c) unemployed; (d) identified with dual diagnoses for mental health and substance use disorders; and (e) with prior substance abuse treatment experience.

Additional financial constraints faced by the OSAT unit are measured with three variables: (a) managed care penetration; (b) percentage of clients with Medicaid; and (c) the number of substance abuse providers in the county. Managed care penetration is measured as the percentage of clients in the most recent fiscal year insured by either a public or private, contractual or noncontractual managed care agreement. The number of substance abuse treatment providers in a county reflects external competition from either other outpatient or inpatient treatment facilities.

Time effects are measures using two dummy variables to indicate study year, 2000 Wave 5 and 2005 Wave 6, respectively, with 1995 Wave 4 serving as the referent.

Table 1 displays weighted descriptive statistics for the dependent and independent variables. Bivariate correlations were examined to scrutinize potential multicollinearity concerns. Only two independent variables (OSAT for-profit and nonprofit status) displayed correlation coefficients exceeding (in absolute value) 0.60.

Table 1.

Variable definition and weighted descriptive statistics

| Pooled sample waves 1995, 2000, 2005 (n = 1,526) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | M | SD |

| Dependent | ||

| Access to treatment | ||

| % clients with no insurance and unable to pay | 24.05 | 31.04 |

| Treatment retention | ||

| % clients with shorter treatment because unable to pay | 2.07 | 7.41 |

| Predictor | ||

| Ownership | ||

| Public ownership | 0.25 | 0.43 |

| Private nonprofit ownership | 0.53 | 0.50 |

| Private for-profit ownership (referent) | 0.22 | 0.41 |

| Affiliation | ||

| Hospital affiliation | 0.13 | 0.34 |

| Mental health center affiliation | 0.18 | 0.39 |

| Freestanding—no affiliation | 0.28 | 0.45 |

| Other affiliation (referent) | 0.41 | 0.49 |

| Methadone treatment | ||

| Methadone provider | 0.15 | 0.35 |

| Client characteristics | ||

| % clients non-Hispanic African American | 38.69 | 28.13 |

| % clients Hispanic/Latino | 14.93 | 19.58 |

| % clients unemployed | 22.78 | 26.15 |

| % clients with dual diagnoses | 64.96 | 26.70 |

| % clients with prior treatment | 35.18 | 24.32 |

| Financial constraints | ||

| % clients with managed care | 17.63 | 28.32 |

| % clients covered by Medicaid | 15.51 | 25.62 |

| No. of substance abuse providers in the county | 65.69 | 116.80 |

5. Analysis strategy

The unit of analysis is the OSAT unit. The two dependent variables are represented by proportional measures. For example, with our first dependent variable, instead of using a percentage, we model the number of clients unable to pay for treatment divided by the total number of OSAT clients in the most recent fiscal year. This approach for dependent variable construction then controls for unit size. Because the distribution of the dependent variables are overdispersed, conventional logistic regressions models are misspecified with overly narrow standard errors. In particular, the research design had a longitudinal component, where most observations were from three waves of data. The generalized estimating equations (GEE) framework accounts for the correlation among repeated measures on the same unit over time. GEE is also robust when there is overdispersion of the dependent variables.

An important feature of GEE is that parameter estimates have the same interpretation as parameters estimated using generalized linear models for cross-sectional data. GEE accounts for within-unit correlation by correcting the standard errors of the regression coefficient estimates using the sandwich method (Liang & Zeger, 1985; Liang & Zeger, 1986; McCullagh & Nelder, 1989). An advantage of the sandwich method is that it does not require the correct specification of the within-unit correlation matrix yet still produces consistent parameter estimates. (Robustness checks with random-effect specifications obtained similar results to those reported here.)

6. Results

Weighted descriptive data in Table 1 show that on average, 24% of OSAT unit clients had no insurance and were unable to pay for treatment. Once treatment began, on average, less than 2% of OSAT clients were reported to have received shortened care because of an inability to pay.

Data on organizational characteristics show that most of the units, 53% in our pooled sample, were private not-for-profit units, with the remaining units divided fairly evenly between public (25%) and private for-profit ownership (22%). More than two thirds of the OSAT units were affiliated with some type of parent organization: 13% were affiliated with hospitals, 18% were affiliated with mental health centers, 28% of the units were freestanding, with the remaining 41% indicating some other type of organizational affiliation. Methadone treatment modality was available in 15% of the outpatient treatment units.

Client characteristics data revealed that 39% of the clients were African American, 15% were of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, and approximately 23% were unemployed. Other unit measures of client severity showed that 67% of the clients had received dual-diagnoses for substance abuse and other psychiatric disorders, and 35% of clients had received prior treatment. Approximately 18% of clients received care under some sort of managed care arrangement, whereas 15% of clients were covered by Medicaid. There were, on average, 66 other substance abuse providers in the county.

6.1. Multivariate results

Table 2 presents the multivariate GEE results for the two dependent variables representing access to treatment and shortening of treatment, respectively: percentage of clients with no insurance and who are unable to pay for treatment and percentage of clients receiving shortened treatment because they were unable to pay. To offer a more intuitive sense of our GEE analysis results, we present figures that examine the predicted proportion of the access characteristics when select predictors are varied.

Table 2.

GEE regression results for measures of access

| Access to treatment |

Treatment retention |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unable to pay (n = 1,504) |

Shortened treatment (n = 1,526) |

|||

| Variables | Coefficient | SEa | Coefficient | SEa |

| Public ownership | 1.693**** | 0.295 | −2.217**** | 0.468 |

| Private not-for-profit ownership | 1 498**** | 0.238 | −1.394**** | 0.341 |

| Hospital affiliation | −0.152 | 0.244 | 0.472 | 0.416 |

| Mental health center affiliation | −0.064 | 0.216 | −0.485 | 0.398 |

| Freestanding—no affiliation | −0.059 | 0.193 | −0.602** | 0.304 |

| Methadone provider | −0.693*** | 0.219 | 0.845** | 0.403 |

| % clients non-Hispanic African American | 0.785*** | 0.290 | −0.016 | 0.645 |

| % clients Hispanic/Latino | 0.927** | 0.419 | 0.418 | 0.463 |

| % clients unemployed | 0.833** | 0.385 | −1.029** | 0.485 |

| % clients with dual diagnoses | 0.261 | 0.367 | 1.356*** | 0.425 |

| % clients with prior treatment | −0.519* | 0.282 | 0.390 | 0.423 |

| % clients with managed care | −1.282**** | 0.261 | 1.087**** | 0.304 |

| % clients covered by Medicaid | −1.454**** | 0.411 | −0.472 | 0.488 |

| No. of substance abuse providers in the county | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Wave 5−2000 | 0.337** | 0.169 | 0.003 | 0.322 |

| Wave 6−2005 | 0.550** | 0.243 | 0.294 | 0.348 |

| Intercept | −2.663 | 0.337 | −3.650 | 0.416 |

Robust standard errors are reported.

p = .10.

p = .05.

p = .01.

p = .001.

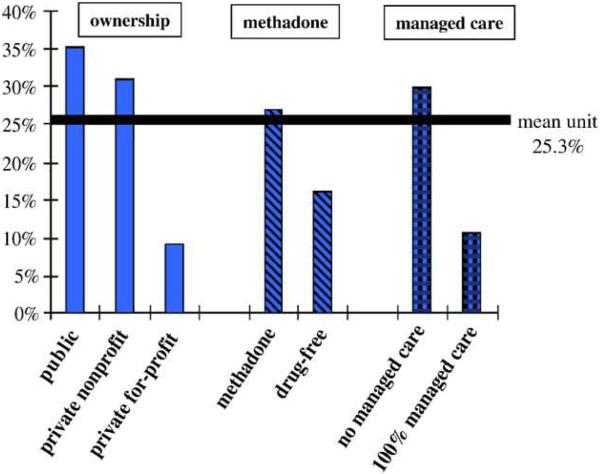

For each figure, we have a “mean unit” baseline that is the predicted proportion when all variables are at the mean level. The figures then show, in turn, the predicted proportion of the access variable when the labeled predictor is entered into the model results with all other independent variables held at their mean.

For example, to calculate the predicted proportion of clients unable to pay for treatment in public units, the value of x for the public unit was set to one (then multiplied by its β coefficient), whereas the value of x for the private nonprofit was set to zero. All other independent variables were assigned the mean value for x. Predicted probabilities were then calculated using these parameter values.

6.1.1. Access to treatment

GEE results in Table 2 show that ownership is a significant predictor of access for the uninsured. Both public (β = 1.693, p < .001) and private nonprofit (β = 1.498, p < .001) OSAT units provide significantly greater access to care for the uninsured and those otherwise unable to pay for treatment than does the referent group: private for profit providers. Fig. 1 illustrates that the predicted proportions of clients unable to pay (with all other independent variables held at the mean) are 35.2% in public units, 30.9% in private nonprofit units, and 9.1% in private for-profit units.

Fig. 1.

Predicted proportion of clients unable to pay: by ownership status, methadone therapy, and managed care penetration. Note: for each bar, the predicted proportion is calculated when the labeled predictor in the grouping is varied and all other predictors are held at the mean value.

Variations in the model specification show that public units do not differ significantly in the percentage of clients unable to pay when compared with private nonprofit units. Unit affiliations are not associated with treatment access for clients unable to pay. Methadone-maintenance programs (β = −0.693, p < .01) provide access to a significantly smaller percentage of clients unable to pay than drug-free OSAT units. Fig. 1 shows that in methadone units, 16% is the predicted proportion of clients unable to pay, whereas that level is a markedly higher level of 27% for nonmethadone or drug-free units; all other variables held equal.

Units with a higher percentage of at-risk client groups showed consistency in their access practices. Specifically, units with higher percentages of African American clients (β = 0.785; p < .01), Hispanic clients (β = 0.927, p < .05), and unemployed clients (β = 0.833, p < .05) were more likely to provide access to care for the uninsured and underinsured. Two measures that reflect client severity, dual diagnoses and prior substance abuse treatment, were not found to be associated with increased access for those unable to pay.

Managed care penetration exhibited a significant and negative relationship (β = −1.282, p < .001) with the percentage of clients unable to pay for OSAT care. Graphically shown in Fig. 1, units with no managed care penetration have a predicted proportion of clients unable to pay of 10.5% versus a predicted proportion of 29.8% when all clients are under managed care arrangements. Similarly, the percentage of clients with Medicaid coverage also showed a significant and negative association (β = −1.454, p < .001) with treatment access for clients unable to pay. Competition from other substance abuse providers in the county had no notable effect on access to treatment.

In comparison to the 1995 referent year, there is a greater predicted proportion of clients unable to pay for treatment in 2000 (26%; β = 0.337, p < .05) and 2005 (35%; β = 0.550, p < .05). Additional variations in model specification show, however, that there were no significant differences between 2000 and 2005.

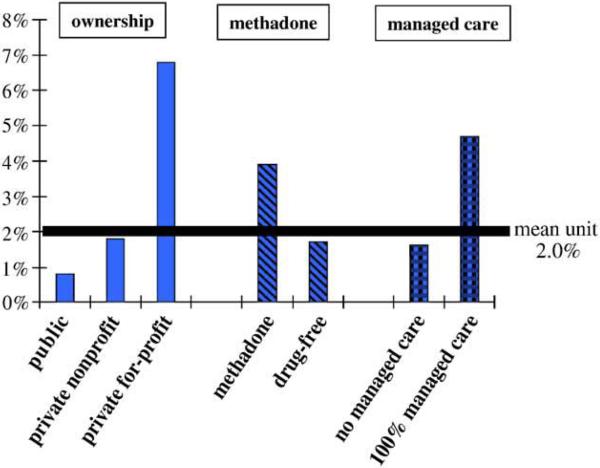

6.1.2. Shortening of treatment

Similar to what was observed with access to treatment, ownership exhibits a statistically significant association with the percentage of clients who receive shortened treatment because of an inability to pay. Table 2 shows that in comparison to private for-profit units, public (β = −2.217, p < .001) and private nonprofit (β = −1.394, p < .001) OSAT units are significantly less likely to reduce treatment retention for clients with an inability to pay.

Additional model specification shows that public units have significantly lower percentages of clients who receive shortened treatment in comparison to private nonprofit units (β = −0.823, p < .05). Fig. 2 shows the predicted proportions of clients with shortened treatment are 0.8% in public units, 1.8% in private nonprofit units, and 6.8% in private for-profit units, with all other independent variables held at the mean. In comparison to “other” organizational affiliation, freestanding OSAT units (β = −0.602, p < .05) are less likely to shorten treatment periods for their clients. Methadone-maintenance units (β = 0.845, p < .05) are more likely to shorten treatment if clients have inadequate financial resources than are drug-free units. Fig. 2 also illustrates predicted proportions for treatment retention for methadone modality. All else equal, 3.9% of the clients at methadone units and 1.7% of clients at drug-free units are predicted to have a shortened treatment because of an inability to pay.

Fig. 2.

Predicted proportion of clients with shortened treatment because of payment inability: by ownership status, methadone therapy, and managed care penetration. Note: for each bar, the predicted proportion is calculated when the labeled predictor in the grouping is varied and all other predictors are held at the mean value.

Two client characteristics showed significance association with the shortening of treatment. Here, units with a higher percentage of unemployed clients were less likely to shorten treatment because of an inability to pay (β = −1.029, p < .05). OSAT units having more clients with dual-diagnoses were significantly more likely to do the same (β = 1.356, p < .01).

Managed care penetration (β = 1.087, p < .05) exhibited a significant and positive association with the percentage of clients receiving shortened treatment because of client inability to pay. Fig. 2 illustrates that if no clients have managed care arrangements, 1.6% of clients are predicted to experience shortened treatment because of an inability to pay. All else being equal, if all clients have managed care arrangements, then 4.7% of those clients are predicted to have shortened treatment because of an inability to pay.

No other variables showed significant associations with shortened treatment. To test for period-specific effects, analyses were conducted on the interaction terms between ownership and year in both models, but findings were not significant. Interaction terms between ownership and the other model predictors also did not present significant results. For reasons of parsimony, these were eliminated from the final model specifications.

6.1.3. Specification checks

We performed several specification checks to examine the robustness of our findings. We ran separate regression specifications by NDATSS survey wave, included OSAT unit size as an explicit covariate, and also ran a random-effect specification rather than our original GEE approach. None of these alternative specifications changed our principal results.

To explore the potential impact of local context and market conditions, we re-ran the regressions with additional county-level control variables drawn from the 2003 Area Resource File. In particular, we chose three specific market variables. To capture variations in local economic conditions and, implicitly, variation in public resources, we include county unemployment rates. To proxy for managed care penetration, we also include a general measure of managed care penetration (for all medical services) at the county level. To proxy for the supply of medical inputs in local communities, we include the number of physicians per 100,000 county residents. Because this physician measure was highly correlated with county per-capita income, it also helps to control for possible confounding effects of local economic conditions.

Results of this expanded model indicate that local unemployment rate, HMO penetration, and physician supply were statistically insignificant in all regressions. Inclusion of these variables had a negligible effect on our point estimates and standard errors.

Our results were also potentially confounded by differences in treatment intensity across ownership types. We have reanalyzed the data with an additional variable: log (FTE staff per client served). We choose this variable because FTE staff is more reliably measured than many other revenue and cost data items. Including this variable did not noticeably change our coefficients or standard errors (Lemak & Alexander, 2005).

7. Discussion

This study has examined how ownership of OSAT programs affects their treatment practices and policies. Our article suggests several important patterns pertinent to public health policy. We document large, statistically significant associations between OSAT unit ownership and both restricted treatment access and shortening of treatment duration for financial reasons. In comparison to private nonprofit and public OSAT units, private for-profit units were less likely to provide initial treatment access and reported shortened treatment for a greater percentage of clients unable to pay. The operational and strategic meaning of reducing access to nonpaying clients or shortening treatment may differ substantively depending on the ownership of the OSAT unit. This suggests that ownership should be viewed as a contextual factor providing meaning to organizational strategies and practices as it is a direct determinant of such practices.

Given the fiscal motivation and mission of for-profit providers, we would expect to see these units deploy practices that may limit financial vulnerability. Friedmann et al. (2003) suggest that because immediate access is desirable in addiction treatment, private for-profit units may turn away clients with fewer personal resources to reserve space for potential paying patients. These authors suggest that the private for-profit units may engage in a type of “financial triage,” which limits the percentage of indigent clients gaining access to care.

Consistent with this interpretation, other research has shown that private for-profits units are motivated to engage in practices to enhance their fiscal strength. This includes provision of care to a market segment with more private and client funding and less severe addiction disorders, which may require fewer costly ancillary services and reduce care coordination (Campbell & Alexander, 2005; D'Aunno & Vaughn, 1995; Friedmann et al., 1999; Wheeler & Nahra, 2000).

For-profit OSATs may also target more affluent or lucrative markets, which would result in lower proportion of indigent patients served by for-profit providers (Olmstead & Sindelar, 2005; Olmstead & Sindelar, 2006). Such practices would not directly confound our results. They would, however, suggest that our analysis, which takes OSAT location as exogenous, may understate the impact of increased for-profit OSAT market penetration delivery on care access for disadvantaged patients.2

In this work, we observed that private for-profit treatment units have a higher percentage of clients with OSAT services terminated when clients are unable to pay. The profit maximization objective encourages these units to operate with more fiscal stringency. It is not to conclude, however, that these motivations necessarily lead to lower-quality treatment practices (Rodgers & Barnett, 2000).

Private nonprofit units were similar to public units in their willingness to admit indigent clients. However, private nonprofit units were more likely than public units to modify treatment plans when payment is no longer available. These OSAT units demonstrate the conceptualization of a two- or even three-tiered addiction treatment system (Rodgers & Barnett, 2000; Wheeler & Nahra, 2000).

It is concerning that methadone-maintenance programs continue to exhibit practices that limit treatment accessibility and prescribe to discontinuation of services for clients unable to pay. Friedmann et al. (2003) also found that methadone programs were less likely to provide “treatment on demand.” The effectiveness of methadone treatment and its ability to stem high-risk behaviors associated with injection use and the related threats of HIV and hepatitis C is well documented (Broome, Joe, & Simpson, 1999; IOM, 2000; Metzger et al., 1993; Pollack, D'Aunno, & Lamar, 2006).

As Friedmann et al. (2003 , p. 897) noted, that with the “recent surge in the popularity and purity of heroin and the continued high risk for HIV and hepatitis C infection among drug injectors,” public policies should be focused on easing treatment barriers for this population of drug users. In the present analysis, methadone-maintenance programs appear neither to provide better treatment access nor to better retain their indigent clients when compared with other OSAT units.

Client case-mix offers some additional insights to the documented challenges that minorities and the unemployed face in addiction treatment (Daley, 2005; Lundgren et al., 2001). Here, we observe that units positioned, either through their mission or environmental circumstance, to accommodate minority clients continue to offer improved treatment access. Yet as these units face greater fiscal constraints, accessibility for these at-risk groups will be further compromised. Indigent clients and potential clients include many whose substance use brings the highest social costs (e.g., Zold-Kilbourn, Tucker, & Berry, 1999). A shift toward for-profit providers may therefore indicate reduced access for homeless individuals and for criminally active client populations in greatest treatment need.

Managed care participation further affects treatment practices and access decisions. Managed care is often regarded in behavioral health care research with an accepted duality. One tenet of managed care lies with its ability to tighten unnecessary treatment practices, constrain escalating costs, and free resources for improved treatment access (French, Dunlap, Galinis, Rachal, & Zarkin, 1996; Geller, 1996; Gondolf, Coleman, & Roman, 1996). On the other side, aspects of managed care may adversely impact treatment access for the indigent. As observed in prior research, managed care reduces the ability of units to cross-subsidize uncompensated care as it employs various oversights and regulation for treatment and reimbursement (Weisner & Schmidt, 2001). OSAT units with more managed care participation may find themselves in a position with less fiscal flexibility and greater external constraints, which poses challenges for providing access to the indigent and under-insured. Managed care market penetration appears associated with decreased access to OSAT services. Although our data do not allow us to infer causality—more stressful market conditions may be associated with increased penetration of managed care—these trends bear watching.

Units that cater to a larger proportion of Medicaid clients exhibited decreased likelihood of clients unable to pay. This may be somewhat counterintuitive because units that cater to clients with fewer financial resources would seem to open their doors to the indigent client as well. One response may be that these units are proficient in assisting clients to gain public or private coverage for OSAT care. These units may also operate in environments that provide more generous entitlements to OSAT care.

This article includes several limitations that must be considered in evaluating our results. Most importantly, our unit-level data do not allow direct client-specific analysis of treatment content and treatment outcomes. Our GEE specification also cannot control for unobserved unit characteristics that may be correlated with our observed covariates. For example, many public and nonprofit OSAT units have long-standing organizational commitments to ensuring care access that are independent of ownership form. If these units were to convert to for-profit status, they might still retain these commitments.

It is also possible that our results reflect informant biases. OSAT directors may underreport the extent that economic factors influence treatment decisions. To the extent that public and nonprofit OSAT units face especially strong normative pressures not to deny or curtail care for economic reasons, it is possible that this may bias our results.

Our prior work indicates close concordance between NDATSS responses and individual chart reviews in two key variables examined in our prior work: treatment duration and in methadone dosage (Pollack and D'Aunno forthcoming). We know of no comparable client-level data to evaluate the two dependent variables examined in our article.

We cannot determine why or how OSAT facilities may have terminated care or chose not to provide care for lack of payment. In principle, such policies could reflect a commitment to high-quality care. If units are not willing to provide indigent clients with reduced-quality care and will not or cannot cross-subsidize such care with resources attached to others, OSAT directors and clinical supervisors may choose not to provide care.

Similarly, we currently know very little about how those who are responsible for delivering care are affected by the policies of OSAT units under different ownership. For example, these providers may be subject to contradictory pressures that affect their effectiveness. On the one hand, as trained professionals, treatment staff are dedicated to providing care that results in the greatest benefit for their clients, including maintenance of treatment regimens and sustained contact with treatment providers. On the other hand, profit maximization incentives may create pressures for providers to improve operating efficiencies in care delivery by limiting treatment duration or channeling “unprofitable” clients to other providers. To the extent that these staff represent the core technology of substance abuse treatment organizations, future studies should attempt to open the “black box” of the relationship between ownership and important client treatment practices.

Compared with a decade ago, a higher proportion of OSAT units restrict treatment access based on financial factors. Given the importance to individual clients and to the broader society of OSAT services, this represents a significant policy concern. Furthermore, the results noted here do not imply that private for-profit organizations do not have a place in the multitiered market for OSAT care. Our results do underscore that the presence of for-profit providers does not imply commensurate treatment access for many clients in greatest need. Especially as the private for-profit segment continues to expand in particular segments of OSAT care, policymakers must closely monitor these patterns.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Given NDATSS survey implementation, respondents are encouraged to define Hispanic/Latino and African American as mutually exclusive categories. Hispanic/Latino individuals may identify with any race. The small minority of clients who identify as both are likely coded as African American exclusively.

We thank an anonymous referee for drawing our attention to these concerns.

References

- BNA Health Law Reporter NonProfit Hospital Charity Care Litigation. 2004;13:1555–1575. [Google Scholar]

- D'Aunno T, Pollack HA. Changes in methadone treatment practices: Results from a national panel study 1988−2000. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:850–956. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.7.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay S. Managed behavioral health care in 1999: An industry at a crossroads. Health Affairs. 1999;18:116–124. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank R, Salkever D. Market forces, diversification of activity, and the mission of nonprofit hospitals. In: Cutler D, editor. The changing hospital industry: Comparing not-for-profit and for-profit institutions. Chicago University of Chicago Press; 2000. pp. 195–215. [Google Scholar]

- French MT, Dunlap LJ, Galinis BA, et al. Health care reforms and managed care for substance abuse services: Findings from eleven case studies. Journal of Public Health Policy. 1996;17:181–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanter M, Keller DS, Dermatis H, et al. The impact of managed care on substance abuse treatment: A report of the American Society of Addiction Medicine. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2000;19:13–34. doi: 10.1300/J069v19n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller JL. Mental health services of the future: Managed care, unmanaged care, mismanaged care. Smith College Studies in Social Work. 1996;66 [Google Scholar]

- Gondolf E, Coleman K, Roman S. Clinical-based vs. insurance-based recommendations for substance abuse treatment level. Substance Use & Misuse. 1996;31:1101–1116. doi: 10.3109/10826089609063967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella C, Stein J. Impact of program services on treatment outcomes of patients with comorbid and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2006;75:1007–1015. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.7.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Edlund MJ. Use of mental health care and substance abuse treatment among adults with co-occurring disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:954–959. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MT, Reif S, Ritter GA, et al. Access to services in the substance abuse treatment system. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent developments in alcoholism. Vol. 15. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2001. pp. 137–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemak CH, Alexander JA. Factors that influence staffing of outpatient substance abuse treatment programs. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:934–939. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty D, Frank RD, Denmead GC. Methadone maintenance and state Medicaid managed care programs. Milbank Quarterly. 1999;77:341–362. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D. The state of behavioral health in managed care. American Journal of Managed Care. 1999;5(Special Issue):SP17–SP21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metsch LR, Pollack HA. Welfare reform and substance abuse. Milbank Quarterly. 2005;83:65–99. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2005.00336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead TA, Sindelar JL. Does the impact of managed care on substance abuse treatment services vary by provider profit status? Health Services Research. 2005;40(6 Pt 1):1862–1882. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers RH, Barnett PG. Two separate tracks? A national multivariate analysis of differences between public and private substance abuse treatment programs. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26:429–442. doi: 10.1081/ada-100100254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan F. Not for profit ownership and hospital behavior. In: Cuyler AJ, Newhouse JP, editors. Handbook of Health Economics. Vol. 1. Amsterdam Elsevier Science BV; 2005. pp. 1141–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon LM. The resilient sector: The state of nonprofit America. In: Solomon LM, editor. The state of nonprofit America. Washington Brookings Institution Press; 2002. pp. 3–61. [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Schmidt LA. Rethinking access to alcohol treatment. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Vol. 15. New York Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2001. pp. 107–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells R, Lemak CH, Alexander JA, Roddy BL, Nahra TA. Is managed care closing substance abuse treatment units? Managed Care Interface. (n.d.) Accepted at. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Ringwalt CL, Williams CE. Use of substance abuse treatment services by persons with mental health and substance use problems. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:363–369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]