Abstract

We have demonstrated earlier that lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)-induced interleukin-8 (IL-8) secretion is regulated by protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ)-dependent NF-κB activation in human bronchial epithelial cells (HBEpCs). Here we provide evidence for signaling pathways that regulate LPA-mediated transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and the role of cross-talk between G-protein-coupled receptors and receptor-tyrosine kinases in IL-8 secretion in HBEpCs. Treatment of HBEpCs with LPA stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR, which was attenuated by matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitor (GM6001), heparin binding (HB)-EGF inhibitor (CRM 197), and HB-EGF neutralizing antibody. Overexpression of dominant negative PKCδ or pretreatment with a PKCδ inhibitor (rottlerin) or Src kinase family inhibitor (PP2) partially blocked LPA-induced MMP activation, proHB-EGF shedding, and EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation. Down-regulation of Lyn kinase, but not Src kinase, by specific small interfering RNA mitigated LPA-induced MMP activation, proHB-EGF shedding, and EGFR phosphorylation. In addition, overexpression of dominant negative PKCδ blocked LPA-induced phosphorylation and translocation of Lyn kinase to the plasma membrane. Furthermore, down-regulation of EGFR by EGFR small interfering RNA or pretreatment of cells with EGFR inhibitors AG1478 and PD158780 almost completely blocked LPA-dependent EGFR phosphorylation and partially attenuated IL-8 secretion, respectively. These results demonstrate that LPA-induced IL-8 secretion is partly dependent on EGFR transactivation regulated by PKCδ-dependent activation of Lyn kinase and MMPs and proHB-EGF shedding, suggesting a novel mechanism of cross-talk and interaction between G-protein-coupled receptors and receptor-tyrosine kinases in HBEpCs.

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)2 is a bioactive phospholipid that is present as a natural constituent in plasma and tissues and plays important roles in cellular responses such as proliferation, differentiation, motility, and cytoskeletal organization under normal and pathological conditions (1-4). Many of the cellular responses of LPA occur in the nanomolar to micromolar range by binding to specific LPA receptors, LPA1–4, which belong to the endothelial differentiation gene family of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) (5-8). Ligation of LPA to LPA1–4 leads to modulation of signal transduction pathways such as changes in [Ca2+]i, activation of protein kinase C, Src kinase, mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, phospholipases, and Pyk2 (9-11). We have reported that LPA1–3 were present in human bronchial epithelial cells (HBEpCs) (12), and LPA-induced stimulation of IL-8 gene expression and secretion was dependent on changes in intracellular Ca2+, activation of PKCδ, and transcription of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and AP-1 (13-15). Furthermore, overexpression of lipid phosphate phosphatase-1 attenuated LPA-induced IL-8 formation by attenuating intracellular signaling pathways, such as changes in [Ca2+]i and translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus (14).

Although LPA-induced modulation of signaling pathways are primarily via its cognate receptors, transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) by GPCRs has been identified as a key link to the MAPK signaling pathway in ovarian cancer cells (16), the liver epithelial cell line (C9) (17), vascular smooth muscle cells (18), prostate cancer cells (19, 20), and PC12 cells (21). EGFR, similar to other growth factor receptors, is activated by forming homo- or heterodimers upon interactions with ligands such as EGF or heparin binding-EGF (HB-EGF) or tumor growth factor-α that are shedded by activated matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (22-25). Additional mechanisms of receptor-tyrosine kinase (RTK) transactivation by GPCRs not affected by MMP inhibitors have been described that utilize protein platforms comprising of G-protein receptor kinase 2, β-arrestin, and adaptor proteins (26, 27). In addition to transactivation of EGFR, LPA also stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of PDGFR (12, 28, 29). In HBEpCs, ligation of the LPA receptors by LPA resulted in increased tyrosine phosphorylation of PDGFRβ by a transactivation mechanism that involved phospholipase D (PLD) 2- but not PLD1-dependent signal transduction (12). Furthermore, in HBEpC activation of MAPK by LPA was dependent in part on GPCR-mediated transactivation of PDGFRβ (12).

Interleukin-8 (IL-8) is a potent chemoattractant for neutrophils and plays a pivotal role in innate immunity and angiogenesis (30-34). IL-8 level is elevated in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthmatic patients (34-36). Also, exposure of bronchial epithelial cells to histamine, ozone, smoke extract, and virus enhanced secretion of IL-8 (37-39). In primary bronchial epithelial cells and the Beas-2B epithelial cell line, the cigarette smoke-induced IL-8 secretion was blocked by neutralizing anti-EGFR (40). LPA is a potent regulator of IL-8 gene expression and secretion in HBEpCs (13, 14); however, mechanisms of LPA-mediated transactivation of EGFR by LPA and involvement of this cross-talk between GPCR and EGFR in IL-8 secretion have not been defined. In the present study we have examined the mechanisms of regulation of EGFR transactivation by LPA receptors and the role of this cross-talk between GPCR and RTK in LPA-mediated IL-8 production in HBEpCs. We provide evidence that EGFR transactivation in response to LPA predominantly depends on PKCδ-medicated activation of Lyn kinase, MMP, and proHB-EGF shedding. Furthermore, down-regulation of EGFR by EGFR-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) partially attenuated LPA-induced IL-8 secretion. These data suggest that in HBEpCs, LPA-mediated transactivation of EGFR represents an important regulatory pathway in controlling part of IL-8 production in addition to LPA-dependent NF-κB/AP-1 transcriptional activation via cognate LPA receptors.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

1-Oleoyl (18:1) LPA was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Antibodies to phospho-IκB (Ser-32), c-Src, c-Fyn, c-Yes, c-Lyn, and extracellular signal-related kinase were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). The antibody for PKCδ was purchased from BD Biosciences. Antibodies to LPA1, LPA2, and LPA3 were from Life-Span BioSciences (Seattle, WA). Antibodies to EGF receptor and phospho-EGF receptors (tyrosines 845, 945, 1048, and 1068) were procured from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA), and the antibody to phospho-EGF receptor (tyrosine 1173), human recombinant EGF, and human recombinant HB-EGF were from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). The antibody to proHB-EGF was purchased from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). MMP2/9 inhibitor (MMP2/9i), PD158780, GM6001, diphtheria toxin, CRM mutant (CRM 197), and pertussis toxin were purchased from Calbiochem. Rottlerin and AG1478 were from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Transfection reagent was from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, and Alexa Fluor-488 goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). The ECL kit for the detection of proteins by Western blotting was obtained from Amersham Biosciences. The ELISA kit for IL-8 measurement was purchased from BIOSOURCE International Inc. (Camarillo, CA). All other reagents were of analytical grade.

Cell Culture

Primary human bronchial epithelial cells were isolated from normal human lung obtained from lung transplant donors following previously described procedures (41, 42). The isolated P0 HBEpCs were seeded at a density of 1.5 × 104 cells/cm2 onto vitrogen-coated (1:75 in sterile water, Cohesion, Palo Alto, CA) P-100 dishes in basal essential growth medium (supplied by Clonetics, BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) that was serum-free and supplemented with growth factors. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 and 95% air to ~80% confluence and subsequently propagated in 35-mm or 6-well collagen-coated dishes. All experiments were carried out between passages 1 and 4.

Measurement of IL-8 Secretion

HBEpCs were cultured in 6-well plates. After pretreatment with or without AG1478 or PD158780 or EGFR siRNA, cells were challenged in BEBM containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin with or without LPA, EGF, or HB-EGF at the indicated concentrations for 3 h. At the end of the experiment cell supernatants were collected, centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, and frozen at -80 °C for later analysis of IL-8 by ELISA, which was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Transfection of Adenoviral Constructs

Infection of HBEpCs (~60% confluence) with purified empty adenoviral vector and adenoviral vectors of PKCδ dominant negative or mouse lipid phosphate phosphatase-1 wild type were carried out in 6-well plates as described previously (13, 14). After infection with different m.o.i. in 1 ml of basal essential growth medium for 48 h, the virus-containing medium was replaced with complete BEBM, and experiments were performed.

Preparation of Cell Lysates and Western Blotting

After the indicated treatments, HBEpCs were rinsed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in 200 μl of buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 μg/ml protease inhibitors, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 μg/ml pepstatin. Cell lysates were incubated at 4 °C for 10 min, sonicated on ice for 10 s, and centrifuged at 5000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C in a microcentrifuge. Protein concentrations were determined with a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce) using bovine serum albumin as the standard. Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were subjected to 10% or 12% SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, blocked with 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk in TBST (25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 137 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h, and incubated with primary antibodies in 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in TBST for 1–2 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed at least 3 times with TBST at 15-min intervals and then incubated with either mouse or rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:3000 dilution) for1hat room temperature. The membranes were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence detection system according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Transfection of siRNA for EGFR, Src Kinase, and Lyn Kinase

Smartpool RNA duplexes corresponding to EGFR, Src kinase, and Lyn kinase were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Scrambled control #2 siRNA was from Dharmacon Research Inc (Lafayette, CO). HBEpCs (P1 or P2) were cultured onto 6-well plates. At 40–50% confluence, transient transfection of siRNA was carried out using Transmessenger Transfection Reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Briefly, siRNA (100 nM) was condensed with Enhancer R and formulated with Transmessenger reagent according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The transfection complex was diluted into 900 μl of BEBM medium and added directly to the cells. The medium was replaced with complete basal essential growth medium after 3 h. Cells were analyzed at 72 h after transfection by Western blotting.

Immunocytochemistry

HBEpCs grown on coverslips to ~80% confluence were challenged with LPA (1 μM) for 15 min. Coverslips were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline and treated with 3.7% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline at room temperature for 20 min. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline, coverslips were incubated in blocking buffer (1% bovine serum albumin in TBST) for 1 h, and cells were subjected to immunostaining with total EGFR antibody or Lyn antibody (1: 200 dilution) for 1 h and washed 3 times with TBST followed by staining with Alexa Fluor 488 (1:200 dilution in blocking buffer) for 1 h. After washing at least three times with TBST, the coverslips were mounted using commercial mounting medium for fluorescent microscopy (Kirkegaard and Perry laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD) and were examined by immunofluorescent microscope with Hamamatsu digital camera using a 60× oil immersion objective and MetaVue software.

Gelatinase Zymography Assay

HBEpCs were infected with empty adenoviral vector or dominant negative PKCδ (25 m.o.i.) for 48 h or pretreated with GM6001 for 1 h or transfected with Lyn siRNA or scrambled siRNA for 72 h and then challenged with LPA (1 μM) for 10 min. The medium was collected and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min to remove cell debris. 500 μl of medium were concentrated using MILIPORE TM-10 kit, and an equal volume was subjected to 10% Novex-Casien zymography gels (Invitrogen). Gels were incubated in renaturing solution (Invitrogen) for 30 min and then incubated in developing solution for 30 min. After replacement with new developing solution (Invitrogen), incubations were continued at 37 °C for an additional 20 h. Gels were stained with SimplyStain solution (Invitrogen) for 30 min and destained by using water for 24 h. MMP activity was visualized as clear areas.

In Vivo Phosphorylation of Lyn Kinase by [32P]Orthophosphate

HBEpCs (~60% confluence in 35-mm dishes) were infected with empty adenoviral vector or dominant negative PKCδ expression vector (25 m.o.i.) for 48 h, and cells were then labeled with [32P]orthophosphate (50 μCi/ml) in BEBM medium for 3 h. The radioactive medium was aspirated, and cells were exposed to LPA (1 μM) in BEBM medium for 15 min. Total cell lysates (~500 μg of protein) were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Lyn antibody (50 μg/ml) for 18 h, immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE, and images were analyzed by autoradiography.

RNA Isolation and Real-time Reverse Transcription-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cultured HBEpCs using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and RNA was quantified by spectrophotometry. cDNA was prepared using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). Primers for human IL-8 and 18 S were designed using Beacon Designer 2.1 software (15). Real-time PCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green Supermix and the iCycler real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). The -fold change in expression of IL-8 mRNA relative to 18 S RNA was calculated based on the threshold cycle (Ct) as 2-(IL-8 threshold cycle)/2-(18 S threshold cycle) × 106.

Statistical Analyses

All results were subjected to statistical analysis using one-way analysis of variance and, whenever appropriate, analyzed by Student-Newman-Keuls test. Data are expressed as the means ± S.D. of triplicate samples from at least three independent experiments, and the level of significance was taken to p < 0.05.

RESULTS

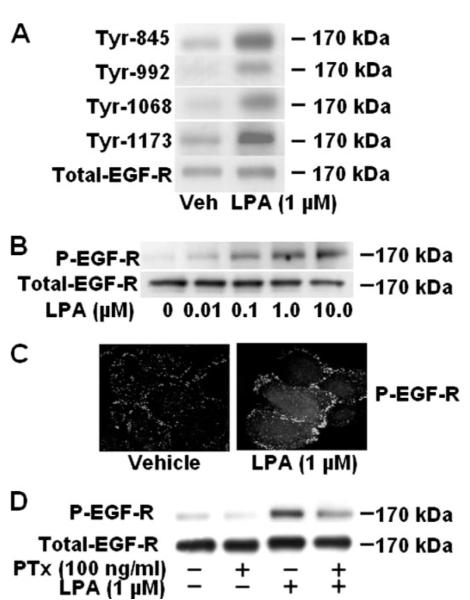

LPA-induced EGFR Tyrosine Phosphorylation Is Sensitive to Pertussis Toxin

Transactivation of RTKs by several GPCR ligands has been well documented (16-29), and we have recently shown that generation of phosphatidic acid (PA) by phospholipase D2 activation is involved in LPA-induced PDGFRβ tyrosine phosphorylation and downstream signaling in HBEpCs (12). Here we examined the cross-talk between LPA receptors and EGFR in LPA-induced IL-8 secretion. HBEpCs challenged with LPA and EGFR activation was studied by Western blotting with phosphotyrosine-specific EGFR antibodies (specific for tyrosine residues at 845, 992, 1068, and 1173). As shown in Fig. 1A, stimulation of cells with LPA (1 μM) for 15 min increased EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation on Tyr-845, Tyr-925, Tyr-1068, and Tyr-1173. Because tyrosine phosphorylation of Tyr-1173 is essential for EGFR activation, we used anti-phospho-Tyr-1173-EGFR antibody to determine EGFR activation in all the experiments. Furthermore, LPA-stimulated EGFR phosphorylation was dose-dependent with maximal tyrosine phosphorylation seen with 1 μM LPA (Fig. 1B). To confirm the results from Western blotting, HBEpCs grown on glass coverslips were stimulated with LPA (1 μM) for 15 min, and phosphorylated EGFR was localized by indirect immunofluorescence. As shown in Fig. 1C, LPA (1 μM) significantly increased immunostaining for phosphorylated EGFR on the plasma membrane and concentrated in areas of lamellipodia. Treatment of cells with EGF (20 ng/ml, 15 min) showed much stronger phosphorylation of EGFR compared with LPA in and around the plasma membrane (data not shown). Because LPA1–3 are coupled to a variety of heterotrimeric G proteins (5-8) and LPA-induced PDGFRβ phosphorylation is coupled to Gi (12), we investigated the role of Gi in LPA-induced EGFR phosphorylation. HBEpCs were pretreated with pertussis toxin (100 ng/ml, 3 h) before stimulation with LPA (1 μM) for 15 min. As shown in Fig. 1D, pertussis toxin significantly and almost completely attenuated the LPA-induced EGFR phosphorylation (~85% inhibition), suggesting that LPA-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR is coupled to Gi.

FIGURE 1. LPA induces tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR in HBEpCs.

A, HBEpCs (~80% confluence in 6-well plates) were treated with 1 μM LPA for 15 min. Cell lysates (20 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western-blotted with anti-phospho-specific (Tyr-845, -992, -1068, or -1173) EGFR or anti-EGFR antibodies. B, HBEpCs (~80% confluence in 6-well plates) were challenged with increasing concentrations of LPA as indicated for 15 min, and cell lysates (20 μg) were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-phospho-specific (Tyr-1173) EGFR or anti-EGFR antibodies. C, HBEpCs grown on coverslips to ~80% confluence were treated with LPA (1 μM) for 15 min, then were subjected to immunostaining with phospho-specific (Tyr-1173) EGFR antibody and examined by fluorescence microscopy. D, HBEpCs (~80% confluence in 6-well plates) were pretreated with100 ng/ml pertussis toxin (PTx) for 3 h before challenge with LPA (1 μM) for 15 min. Cell lysates (20 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-phospho-specific (Tyr-1173) EGFR or anti-EGFR antibodies. Shown are representative blots of three independent experiments.

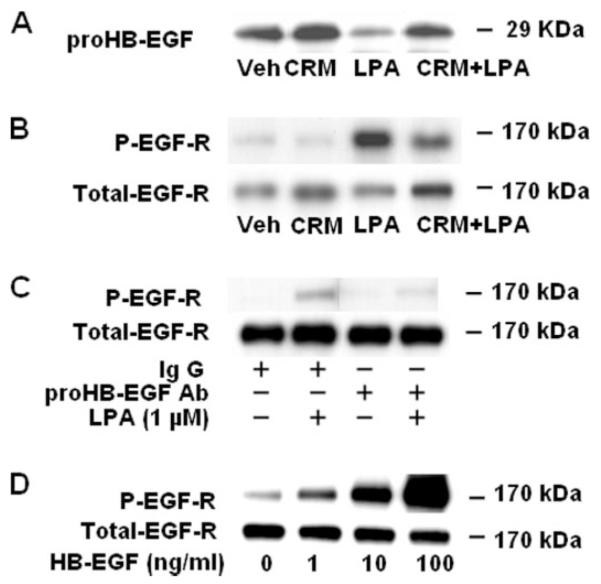

LPA-induced EGFR Transactivation Involves proHB-EGF Shedding

In various cell types the GPCR ligand-induced transactivation of EGFR is mediated by proHB-EGF shedding via activation of MMPs (22-25). To characterize the mechanism(s) of transactivation of EGFR by LPA in HBEpCs, we examined the effect of CRM 197 on LPA-induced proHB-EGF shedding by immunodetection of total cell lysates with a specific antibody that recognizes the ectodomain of proHB-EGF. Fig. 2A shows that in HBEpCs, LPA (1 μM) treatment for 15 min stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR and significantly decreased the total proHB-EGF level in the cells, which were attenuated by pretreatment of cells with CRM 197 (10 μg/ml), a non-toxic mutant of diphtheria toxin that binds specifically to HB-EGF (Fig. 2, A and B). To further confirm the effect of CRM 197 on HB-EGF shedding, the addition of neutralizing antibody to proHB-EGF in the medium prevented LPA-induced EGFR phosphorylation (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, stimulation of cells with 1, 10, and 100 ng/ml HB-EGF for 15 min increased EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 2D). These results demonstrate that LPA-induced EGFR transactivation is dependent on release of HB-EGF.

FIGURE 2. Role of proHB-EGF shedding in LPA-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of EGF receptor.

A and B, HBEpCs (~80% confluence in 6-well plates) were pretreated with CRM 197 (10 μg/ml) for 30 min and then challenged with 1 μM LPA for 15 min. Cell lysates (20 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western-blotted with anti-proHB-EGF or anti-phospho (P)-specific (Tyr-1173) EGFR or anti-EGFR antibodies. C, HBEpCs (~80% confluence in 6-well plates) were pretreated with anti-proHB-EGF antibody (Ab,20 μg/ml) for 1 h and then challenged with 1 μM LPA for 15 min. Cell lysates (20 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western-blotted with anti-phospho-specific (Tyr-1173) EGFR or anti-EGFR antibodies. D, HBEpCs (~80% confluence in 6-well plates) were challenged with increasing concentrations of human recombinant HB-EGF as indicated for 15 min, and cell lysates (20 μg) were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-phospho-specific (Tyr-1173) EGFR or anti-EGFR antibodies. Shown are representative blots of three independent experiments.

Involvement of Matrix Metalloproteinases in LPA-induced proHB-EGF Shedding and EGFR Transactivation

Matrix metalloproteinases have been implicated in the transactivation of EGFR by LPA and other GPCRs (22-25). To examine whether LPA-induced proHB-EGF shedding is dependent on activation of matrix metalloproteinases, we used galardin (GM 6001), a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor. As shown in Fig. 3A, GM 6001 (20 μM) pretreatment attenuated LPA-induced MMP9 activation, as determined by gelatin zymography. Furthermore, GM 6001 also reduced proHB-EGF shedding (Fig. 3B) and tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR (Fig. 3C). The role of MMP2/9 in transactivation of EGFR by LPA was further confirmed with a specific inhibitor, MMP2/9i. In HBEpCs, MMP2/9i (0.1 and 1 μM) pretreatment significantly blocked LPA-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR (Fig. 3D). These results suggest a role for MMP2/9 in LPA-mediated transactivation of EGFR in HBEpCs.

FIGURE 3. Role of MMPs in LPA-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR.

A, HBEpCs (~80% confluence in 6-well plates) were pretreated with GM6001 (2 or 20 μM) for 1 h and then challenged with 1 μM LPA for 15 min. Media were collected, concentrated, and subjected to 10% Novex-Casien zymography gels. Gelatinase activity was detected as described under “Experimental Procedures.” actMMP, activated matrix metalloproteinase. B and C, HBEpCs (~80% confluence in 6-well plates) were pretreated with GM6001 (GM;20 μM) for 1 h and then challenged with 1 μM LPA for 15 min. Cell lysates (20 μg) were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-phospho (P)-specific (Tyr-1173) EGFR or anti-EGFR or anti-proHB-EGF antibodies. D, HBEpCs (~80% confluence in 6-well plates) were pretreated with MMP2/9 inhibitor (0.1 or 1 μM) for 1 h and then challenged with 1 μM LPA for 15 min. Cell lysates (20 μg) were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-phospho-specific (Tyr-1173) EGFR or anti-EGFR antibodies. Shown are representative blots of three independent experiments.

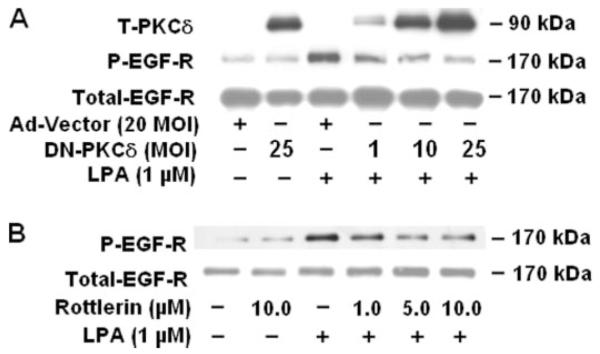

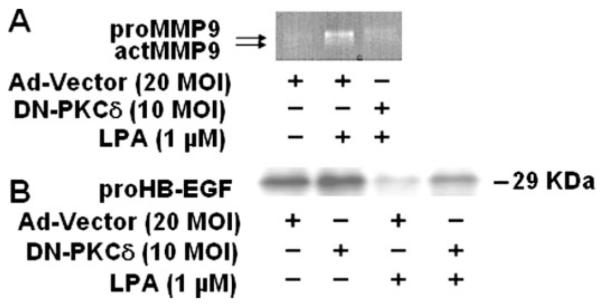

Role of PKCδ in LPA-induced MMP Activation, proHB-EGF Shedding, and EGFR Transactivation

Earlier, we have demonstrated that LPA-induced IL-8 secretion was dependent on PKCδ activation (13). Also, in African green monkey kidney Vero cells overexpressing human proHB-EGF, a PKC-dependent mechanism to yield soluble HB-EGF by phorbol ester has been demonstrated (43). To further understand the mechanism(s) of transactivation of EGFR by LPA, we examined whether LPA-induced EGFR transactivation is regulated by PKCδ previously identified in HBEpCs (13). Infection of HBEpCs with adenoviral vectors of the catalytically inactive mutant of PKCδ showed that dominant negative PKCδ effectively blocked LPA-induced EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation. Infection of HBEpCs with the dominant negative PKCδ at varying multiplicities of infection for 48 h resulted in overexpression of the protein (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4A, overexpression of dominant negative PKCδ significantly blocked LPA-mediated EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation at 10 and 25 m.o.i. of infection. Similarly, pretreatment of cells with rottlerin for1hina dose-dependent manner attenuated LPA-induced EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 4B). Next, we determined the role of PKCδ in LPA-induced activation of MMP9 and proHB-EGF shedding. Overexpression of dominant negative PKCδ (10 m.o.i., 48 h) partially attenuated LPA-induced MMP9 activity (Fig. 5A) and proHB-EGF shedding (Fig. 5B), suggesting that signaling via PKCδ is essential for LPA-induced MMP activation, proHB-EGF shedding, and EGFR transactivation in HBEpCs.

FIGURE 4. Role of PKCδ on LPA-induced tyrosine (T) phosphorylation of EGFR.

A, HBEpCs (~60% confluence in 6-well plates) were infected with increasing m.o.i. of adenoviral dominant negative PKCδ or adenoviral control for 48 h, and then cells were challenged with 1 μM LPA for 15 min. Cell lysates (20 μg) were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-PKCδ antibody or anti-phospho (P)-specific (Tyr-1173) EGFR or anti-EGFR antibodies. B, HBEpCs (~80% confluence in 6-well plates) were pretreated with different concentrations of rotterlin as indicated for 1 h, then cells were challenged with 1 μM LPA for 15 min. Cell lysates (20 μg) were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-phospho-specific (Tyr-1173) EGFR or anti-EGFR antibodies. Shown are representative blots of three independent experiments.

FIGURE 5. Effect of dominant negative PKCδ on LPA-induced proHB-EGF shedding and MMPs activity.

HBEpCs (~60% confluence in 6-well plates) were infected with adenoviral control or dominant negative (DN) PKCδ (10 m.o.i.) for 48 h, and then cells were challenged with 1 μM LPA for 15 min. actMMP, activated matrix metalloproteinase. A, media were collected, concentrated, and subjected to 10% Novex-Casien zymography gels. Gelatinase activity was detected as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Shown is a representative gel image of three independent experiments. B, cell lysates (20 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western-blotted with anti-proHB-EGF antibody. Shown is a representative blot of three independent experiments.

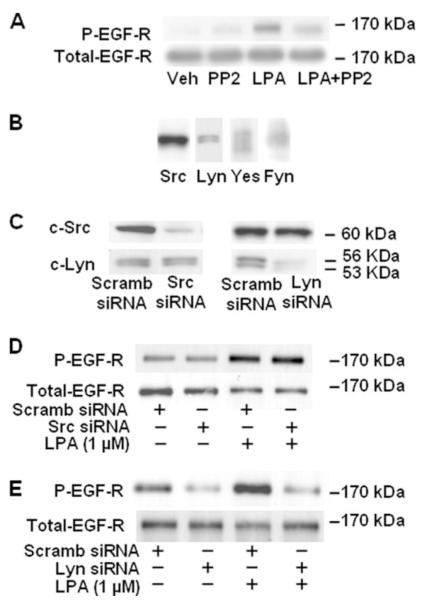

Lyn Kinase, but Not Src Kinase, Regulates LPA-induced EGFR Transactivation

In addition to PKC, several other intermediate signaling molecules such as Ca2+, Src, and Pyk2 may mediate GPCR-induced RTK transactivation (24-27). However, the role of the Src family of non-receptor kinases in proHB-EGF shedding and EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation is unclear. Therefore, we investigated the role of the Src kinase family on MMP activation, proHB-EGF release, and EGFR transactivation by LPA in HBEpCs. HBEpCs were pretreated with PP2 (1 μM) for 1 h before challenge with LPA (1 μM) for 15 min. As shown in Fig. 6A, PP2 attenuated LPA-induced phosphorylation of EGFR at tyrosine site (Tyr-1173). Information on the relative expression of different Src family non-receptor kinases in primary HBEpCs is scarce, and therefore, we assessed protein expression of Src, Lyn, Yes, and Fyn in HBEpCs. Analysis of the whole cell lysates by Western blotting with specific antibodies revealed the presence of Src, Lyn, Yes, and Fyn with the relative amounts of Src > Lyn > Yes > Fyn (Fig. 6B). Because PP2 blocks the kinase activity of all the members of the Src family of non-receptor kinases, we employed siRNA for Src and Lyn to down-regulate the mRNA and protein expression levels. The efficacy of the siRNA employed was determined by Western blotting for the protein expression of Src and Lyn. As shown in Fig. 6C, transfection of cells with siRNA for Src or Lyn specifically blocked the expression of either Src or Lyn proteins, indicating a high degree of specificity in down-regulation without affecting other family member(s). Next we investigated the effect of Src or Lyn siRNA on LPA-induced EGFR activation. HBEpCs were transfected with siRNA for Src or Lyn for 72 h before exposure to LPA (1 μM) for 15 min. As shown in Fig. 6, D and E, Lyn but not Src siRNA attenuated LPA-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR. These data show the involvement of Lyn but not Src in LPA-induced activation of EGFR in HBEpCs.

FIGURE 6. Effect of Lyn siRNA or PP2 on LPA-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR.

A, HBEpCs (~80% confluence in 6-well plates) were pretreated with PP2 (1 μM) for 1 h, then challenged with 1 μM LPA for 15 min. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-phospho (P)-specific (Tyr-1173) EGFR or anti-EGFR antibodies. B, cell lysates from HBEpCs (~80% confluence in 6-well plates) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western-blotted with anti-Src, anti-Lyn, anti-Yes, and anti-Fyn antibodies. Scramb, scrambled. C-E, HBEpCs (~50% confluence in 6-well plates) were transfected with control siRNA, Lyn siRNA (100 nM), or Src siRNA (100 nM) for 72 h as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Cell lysates (20 μg) were analyzed with anti-Src or anti-Lyn or anti-phospho-specific (Tyr-1173) EGFR or anti-EGFR antibodies. Shown is a representative blot of three independent experiments.

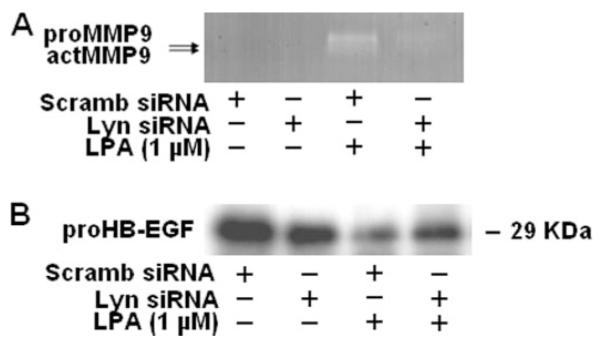

Lyn siRNA Attenuates LPA-induced MMP Activation and proHB-EGF Shedding

To further characterize the role of Lyn in LPA-induced MMP activation and proHB-EGF shedding, HBEpCs were transfected with Lyn siRNA (100 nM) for 72 h, cells were challenged with LPA (1 μM) for 15 min, and MMP9 activation and proHB-EGF shedding were determined by gelatinase zymography or Western blotting, respectively. LPA-induced MMP9 activation and proHB-EGF shedding were attenuated by Lyn siRNA (Fig. 7, A and B). These results demonstrate that the Src non-receptor tyrosine kinase family member, Lyn, regulates MMP9 activation and proHB-EGF shedding in response to LPA in HBEpCs.

FIGURE 7. Lyn siRNA attenuates LPA-induced proHB-EGF shedding and MMP activity.

HBEpCs (~50% confluence in 6-well plates) were transfected with control siRNA or Lyn siRNA (100 nM) for 72 h as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and then cells were challenged with 1 μM LPA for 15min. A, media were collected, concentrated, and subjected to 10% Novex-Casien zymography gels. Gelatinase activity was detected as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Shown is a representative gel image of three independent experiments. B, cell lysates (20 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western-blotted with anti-proHB-EGF antibody. Shown is a representative blot of three independent experiments. actMMP, activated matrix metal-loproteinase; Scramb, scrambled.

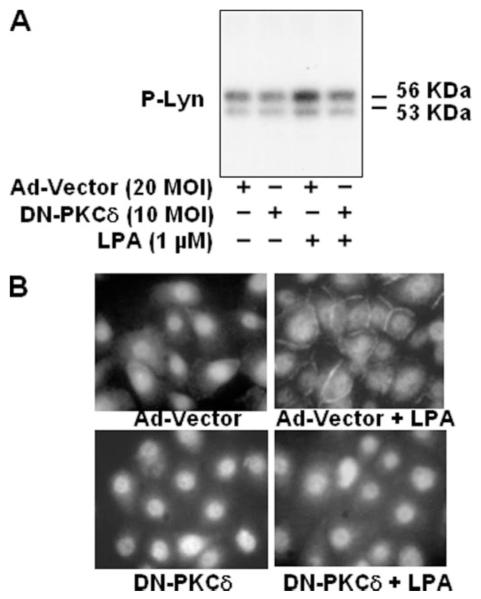

PKCδ Regulates LPA-induced Lyn Phosphorylation and Translocation to Plasma Membrane

It has been reported that PKCδ regulates Src kinase activity (44). Therefore, to further characterize the signaling cascade(s) of EGFR transactivation by LPA, we examined whether PKCδ is involved in LPA-induced Lyn activation in HBEpCs. HBEpCs were transfected with adenoviral dominant negative PKCδ (10 m.o.i.) for 48 h and incubated with [32P]orthophosphate for 3 h. Cells were challenged with media alone or media containing LPA (1 μM) for 15 min, 32P-labeled Lyn kinase was immunoprecipitated with anti-Lyn antibody, and phosphorylation of Lyn kinase was detected by autoradiography of proteins separated by SDS-PAGE. As shown in Fig. 8A, LPA stimulated autophosphorylation of Lyn kinase, and overexpression of dominant negative PKCδ attenuated phosphorylation of Lyn kinase. Furthermore, overexpression of dominant negative PKCδ (10 m.o.i.) blocked LPA-induced Lyn kinase translocation to the plasma membrane as evidenced by immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8. Dominant negative PKCδ attenuates LPA-induced phosphorylation (P) of Lyn and translocation of Lyn to plasma membrane.

A, HBEpCs (~60% confluence in 6-well plates) were infected with adenoviral control vector or dominant negative (DN) PKCδ (10 m.o.i.) for 48 h. Cells were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate (50 μCi/ml) in BEBM medium for 3 h and then challenged with 1 μM LPA for 15 min. Total cell lysates (~500 μg of protein) were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Lyn antibody for 18 h, immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE gel, and radioactivity was analyzed by autoradiography. Shown is a representative image of three independent experiments. B, HBEpCs (~60% confluence in coverslips) were infected with adenoviral control vector or dominant negative PKCδ (10 m.o.i.) for 48 h, and cells were treated with LPA (1 μM) for 15 min, subjected to immunostaining with anti-Lyn antibody, and examined by fluorescent microscopy.

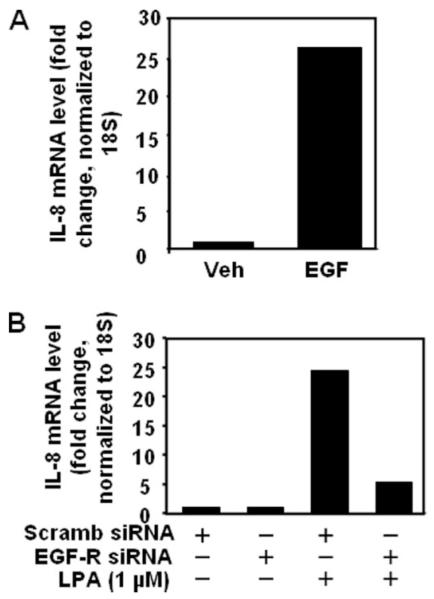

EGFR Transactivation Partially Regulates LPA-induced IL-8 Secretion and Gene Expression in HBEpCs

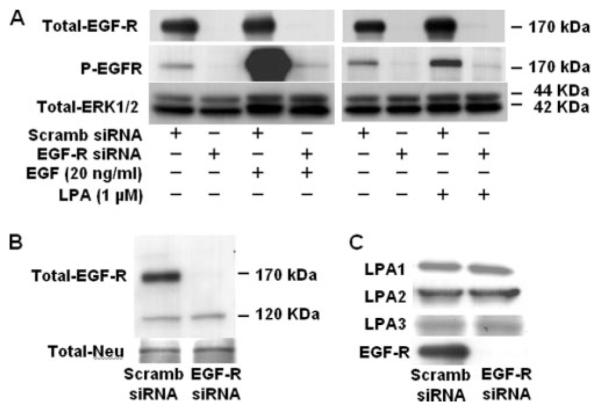

Earlier we showed that LPA-mediated IL-8 secretion was dependent on [Ca2+]i, PKCδ activation, and p38 MAPK- and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-dependent transcriptional regulation of NF-κB and AP-1 in HBEpCs (13-15). Our current results demonstrate that LPA transactivates EGFR; however, the relative contribution of LPA-mediated EGFR transactivation and signal transduction in IL-8 secretion is unknown. To determine the role of EGFR transactivation by LPA in IL-8 secretion, EGFR protein expression was down-regulated by EGFR siRNA. Transfection of HBEpCs with EGFR siRNA for 72 h down-regulated EGFR protein expression by ~90% compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 9A). Under similar transfection conditions, EGFR siRNA blocked both EGF- and LPA-induced EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 9A). Furthermore, transfection of cells with the EGFR siRNA had no effect on the protein expression of Neu, another member of the EGFR family, or LPA1–3, indicating the specificity of the siRNA on the EGFR (Fig. 9, B and C).

FIGURE 9. EGFR siRNA attenuates LPA- or EGF-induced phosphorylation (P) of EGFR and expression of LPA receptors.

A, HBEpCs (~50% confluence in 6-well plates) were transfected with control siRNA or EGFR siRNA (100 nM) for 72 h as described under “Experimental Procedures” and then challenged with of LPA (1 μM) or EGF (20 ng/ml) for 15 min. Cell lysates (20 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-phospho-specific (Tyr-1173) EGFR or anti-EGFR or anti-extracellular signal-related kinase antibodies. Scramb, scrambled. B and C, HBEpCs (~50% confluence in 6-well plates) were transfected with control siRNA or EGFR siRNA (100 nM) for 72 h as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Cells were collected, and cell lysates (20 μg) were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-Neu, anti-LPA1, anti-LPA2, anti-LPA3, or anti-EGFR antibodies. Shown are representative blots of three independent experiments.

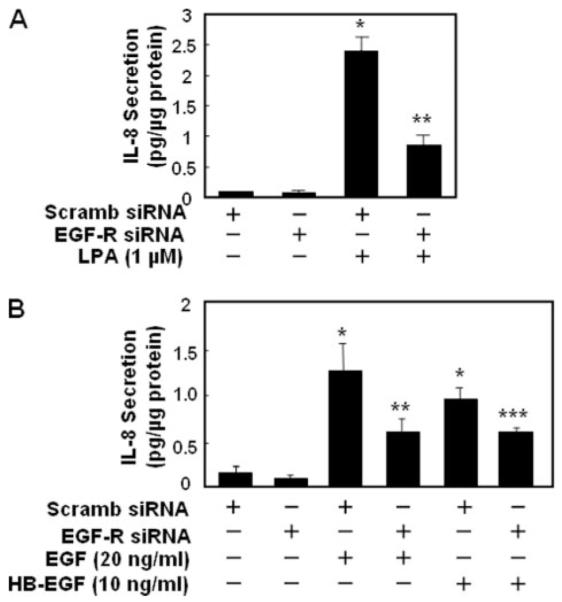

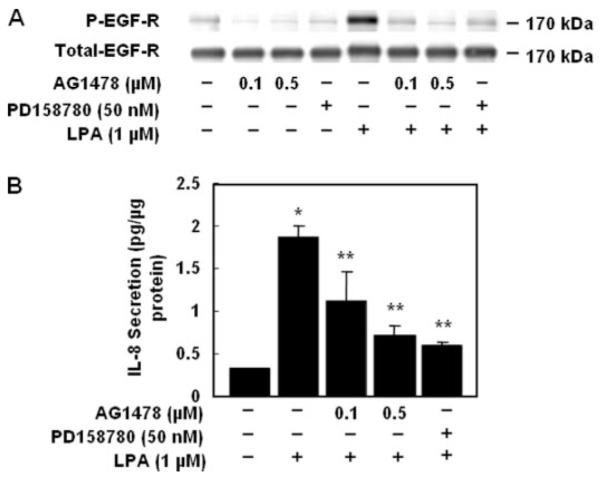

To further determine the role of EGFR transactivation in LPA-induced IL-8 secretion, HBEpCs were transfected with EGFR siRNA to down-regulate EGFR followed by LPA (1 μM) challenge for 3 h, and secreted IL-8 was determined by ELISA. LPA treatment increased IL-8 secretion by 16-fold (vehicle, 0.15 pg/μg of total protein; LPA, 2.35 pg/μg of total protein), whereas EGFR siRNA transfection attenuated LPA-induced IL-8 secretion by ~65% (0.81 pg/μg of total protein) (Fig. 10A). Furthermore, EGFR siRNA transfection partly blocked IL-8 secretion by EGF (20 ng/ml for 3 h) or HB-EGF (10 ng/ml for 3 h) (Fig 10B). The role of EGFR transactivation by LPA in IL-8 secretion was confirmed with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors AG1478 and PD158780. Pretreatment of HBEpCs with AG1478 (0.1 and 0.5 μM) or PD158780 (50 nM) reduced both basal and LPA-induced EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation and attenuated IL-8 secretion (Fig. 11, A and B). These results show that LPA-induced IL-8 secretion in HBEpCs is partly dependent on EGFR transactivation that involves activation of PKCδ, Lyn kinase, and MMP and shedding of proHB-EGF.

FIGURE 10. EGFR siRNA attenuates LPA-, EGF-, or HB-EGF-induced IL-8 secretion.

HBEpCs (~50% confluence in 6-well plates) were transfected with control siRNA or EGFR siRNA (100 nM) for 72 h as described under “Experimental Procedures,” challenged with LPA (1 μM)(A) or EGF (20 ng/ml) or HB-EGF (10 ng/ml) (B) for 3 h, and IL-8 secreted into the medium was quantified by ELISA. Values are the means ± S.D. of three independent experiments and are expressed as pg/μg of protein. *, p < 0.05 compared with vehicle; **, p < 0.05 compared with LPA treatment; ***, p < 0.05 compared with EGF treatment; ****, p < 0.05 compared with HB-EGF treatment. Scramb, scrambled.

FIGURE 11. Effects of AG1478 or PD158780 on LPA-induced phosphorylation of EGFR and IL-8 secretion.

A, HBEpCs (~80% confluence in 6-well plates) were pretreated with AG1478 or PD158780 at the indicated concentrations for 1 h and then challenged with 1 μM LPA for 15 min. Cell lysates (20 μg) were analyzed with anti-phospho (P)-specific (Tyr-1173) EGFR or anti-EGFR or anti-extracellular signal-related kinase antibodies. Shown are representative blots of three independent experiments. B, HBEpCs (~80% confluence in 6-well plates) were pretreated with AG1478 or PD158780 as indicated concentration for 1 h, then cells were challenged with 1 μM LPA for 3 h, and IL-8 secreted into the medium was quantified by ELISA. Values are the means ± S.D. of three independent experiments and are expressed as pg/μg of protein. *, p < 0.05 compared with vehicle; **, p < 0.05 compared with LPA treatment.

Our previous studies have shown that LPA increased IL-8 gene expression (15); therefore, we investigated whether EGFR transactivation by LPA is involved in partial regulation of IL-8 gene expression. As shown in Fig. 12, treatment of HBEpCs to EGF (20 ng/ml) for 3 h stimulated IL-8 gene expression by ~27-fold compared with cells exposed to medium alone (Fig. 12A). Furthermore, transfecting cells with EGFR siRNA (72 h) attenuated LPA (1 μM, 90 min)-induced IL-8 gene expression by ~60% (Fig. 12B), suggesting that EGFR transactivation partial regulates IL-8 gene expression. These results suggest a role for EGFR transactivation by LPA in IL-8 gene expression and secretion in HBEpCs.

FIGURE 12. EGF induces IL-8 gene expression, and EGFR siRNA attenuates LPA-induced IL-8 gene expression.

A, HBEpCs (~80% confluence in 6-well plates) were treated with EGF (20 ng/ml) for 3 h. B, HBEpCs (~50% confluence in 6-well plates) were transfected with scrambled siRNA or EGFR siRNA (100 nM) for 72 h as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and cells were challenged with LPA (1 μM) for 90 min. IL-8 gene expression was evaluated by real-time reverse transcription-PCR as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Veh, vehicle.

DISCUSSION

We earlier identified that LPA is a potent stimulator of IL-8 gene expression and secretion via NF-κB and AP-1 transcription in HBEpCs (13-15). The IL-8 secretion by LPA was dependent on ligation to LPA1–3 expressed on the cell surface of HBEpCs as determined by siRNA studies (15). In addition to signaling via its cognate LPA1–3, ligation of LPA to LPA receptors resulted in transactivation of PDGFRβ (12) that was not coupled to IL-8 production in HBEpCs.3 The novel findings in this study are (i) LPA-mediated activation of PKCδ is central to EGFR transactivation, (ii) Lyn kinase, but not Src kinase, regulates LPA-induced activation of MMPs, proHB-EGF shedding, and EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation, and (iii) LPA-induced transactivation of EGFR partly regulates IL-8 gene expression and secretion.

Earlier studies have demonstrated cross-talk between the GPCRs and RTKs in a variety of mammalian cells, suggesting that these two major plasma membrane receptors share extensive signal transduction pathways leading to activation of extracellular signal-related kinase 1/2, a signal for cell proliferation (12, 19-21, 24, 26-29). Transactivation of EGFR by ligands such as thrombin, angiotensin II, sphingosine 1-phosphate, LPA, endothelin-1, prostaglandin F2α, and parathyroid hormone has been reported (23-27, 45). However, the molecular mechanisms by which various GPCR ligands transactivate EGFR are not completely understood. Recently, a role for changes in intracellular calcium in EGFR transactivation by various GPCR agonists has been reported (45, 46). Pretreatment of HBEpCs with BAPTA/AM, a chelator of intracellular free calcium, had no effect on LPA-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR; however, BAPTA attenuated LPA-induced changes in [Ca2+]i and phosphorylation of extracellular signal-related kinase (data not shown).

In HBEpCs, activation of PKCδ is central to LPA-induced transactivation of EGFR that involves Lyn, MMP2/9, and HB-EGF release. Although earlier studies have suggested a role for PKC-dependent proteolysis of HB-EGF through the activation of MMP in Vero-H cells (44), PKC does not seem to participate in hydrogen peroxide-mediated EGFR transactivation in vascular smooth muscle cells (47). The identity of targets down stream of PKCδ in the activation of MMPs involved in proHB-EGF shedding and EGFR transactivation remains poorly defined. A possible role of Src kinase in mediating the release of HB-EGF by MMPs was suggested in transactivation of EGFR by α2A-adrenergic receptor (48). Furthermore, involvement of Src kinase in tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR by various ligands, such as gastrin-releasing peptide, amphiregulin, angiotensin II, interferon-γ, and sphingosine 1-phosphate have been reported (26, 48-50). Tyrosine 845 of EGFR was found to be an interactive site for EGFR and Src kinase (51) as LPA- or EGF-stimulation promoted Src kinase activation and EGFR endocytosis (52). Among the nine members of Src kinase family, Src and Lyn kinases were primarily expressed in HBEpCs as detected by Western blotting (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, LPA-induced MMP activation, HB-EGF shedding, and EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation were attenuated by Lyn kinase siRNA but not by Src kinase siRNA (Fig. 7, A and B). In support of our data, a study by Wan et al. (53) showed that Gq-coupled muscarinic acetylcholine receptor activated MAPKs, which were blocked in Lyn kinase-deficient cells. Lyn kinase is a key mediator in several pathways of B cell activation (54). Lyn kinase was found to interact with Btk and Syk kinase and Cbl and regulated thrombopoietin-induced proliferation of hematopoietic cell lines and primary megakaryocytic progenitors (55). Our current data show that LPA-induced phosphorylation and translocation of Lyn kinase to plasma membrane is regulated by PKCδ. The mechanism of PKCδ-mediated activation of Lyn kinase by LPA is unclear. It has been reported that PKCδ induces Src kinase activity by modulating the protein-tyrosine phosphatase PTPa (56). In contrast, PKCδ is tyrosine-phosphorylated and regulated by Src family kinase in skin keratinocytes (57). Although we have demonstrated that LPA activated p38/NF-kB and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase/AP-1 pathways, pretreatment with p38 siRNA, NF-κB pathway inhibitor (Bay11–7082), or c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase inhibitor had no effect on LPA-induced phosphorylation of EGFR3, suggesting a different pathway(s) downstream of EGFR involved in IL-8 expression and secretion by LPA.

We have shown that bronchoalveolar lavage from segmental allergen-challenged asthmatics had a higher level of IL-8, LPA, and eosinophils compared with non-allergen-challenged controls (13). Furthermore, in HBEpCs, LPA is a potent stimulator of IL-8 gene expression and secretion (13-15). Consistent with LPA-induced IL-8 secretion in cultured bronchial epithelial cells, instillation of LPA into mouse trachea elevated MIP-2 levels (homolog of human IL-8) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid within 3 h which was followed by neutrophil infiltration in the alveolar space (13); inhalation of LPA increased the numbers of eosinophils and neutrophils in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of guinea pigs (58). These in vivo results in mouse (13) and guinea pigs (58) suggest that accumulation of LPA or lysophosphatidylcholine in alveolar space can be pro-inflammatory signal in airway diseases.

Given that a myriad of signaling pathways regulate LPA-induced IL-8 secretion, our current results in HBEpCs indicate for the first time that cross-talk between GPCRs and RTKs regulates generation of chemotactic cytokine that could induce leukocyte infiltration and activation at sites of inflammation without the actual presence of growth factors in the milieu. Using EGFR siRNA or pharmacological inhibitors that specifically block tyrosine phosphorylation EGFR, we have unequivocally demonstrated attenuation of LPA-induced IL-8 by ~60% (Figs. 10 and 11). Similarly, the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, AG1478, attenuated the H2O2- or cigarette smoke-increased IL-8 release in H292 human pulmonary carcinoma cells (40, 59) and epithelial Beas2B cells; however, the mechanisms of increased EGFR activation and IL-8 production were not investigated. Furthermore, treatment of airway smooth muscle cells with LPA for 12–24 h up-regulated EGFR expression (60); however, in HBEpCs, LPA had no effect on EGFR expression in HBEpCs after 3 h of treatment (data not shown), suggesting LPA-induced IL-8 secretion to be partly dependent on EGFR transactivation.

In HBEpCs, EGF treatment or EGFR transactivation by LPA contributes to IL-8 gene expression (Fig. 12); however, the mechanism(s) is unclear. We reported that LPA-induced IL-8 secretion is regulated at the transcriptional level by p38/NF-κB and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase/AP-1 pathways (13-15). Interestingly, here we found that EGFR siRNA or EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors had no effect on LPA-induced phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase, and I-κB and translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus,3 suggesting that signaling pathways downstream of EGFR transactivation are not involved in LPA-induced p38/NF-kB and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase/AP-1 transcriptional regulation. The physiological significance of our finding is of relevance in amplification, duration, and intensity of signals generated by co-operative interactions between GPCRs/RTKs versus binding of ligands to cognate receptors and signal transduction in biological systems.

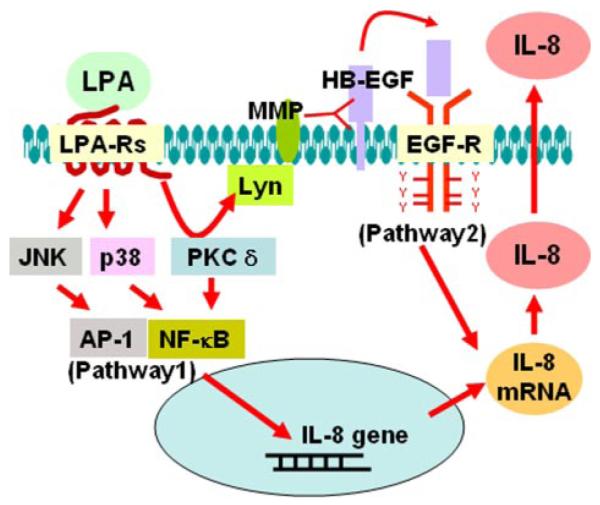

In summary, our findings demonstrate that LPA-induced EGFR transactivation is dependent on Gi, activation of PKCδ, Lyn kinase, and MMP9-mediated proHB-EGF shedding in HBEpCs (Fig. 13). Our results also show that part of LPA-induced IL-8 secretion is dependent on transactivation of EGFR transactivation in HBEpCs. Our work, therefore, provides a novel mechanism of cross-link between LPA receptor and EGFR and a physiological role of GPCR/RTK interaction in release of IL-8, a cytokine that is chemotactic to leukocyte migration and activation at sites of airway inflammation. Thus, therapeutic targeting of LPA receptors with siRNA or specific inhibitors should provide a novel approach of controlling leukocyte trafficking and treating certain inflammatory airway diseases.

FIGURE 13. Signaling pathways of LPA-induced transactivation of EGFR and IL-8 production.

Ligation of LPA to its G-protein-coupled receptors (LPA-R) LPA1–3 induces phosphorylation of EGFR through PKCδ, Lyn kinase, MMP, and proHB-EGF pathway. LPA-induced IL-8 secretion is partly dependent on transactivation of EGFR. JNK, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant HL71152 (to V. N.) and from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, Swindon, United Kingdom (to N. J. P.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement”in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

- LPA

- lysophosphatidic acid

- HB

- heparin binding

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor κB

- HBEpCs

- human bronchial epithelial cells

- EGFR

- epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor

- MMP

- matrix metalloproteinase

- PDGFR

- platelet-derived growth factor receptor

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- BEBM

- bronchial epithelial basal medium

- PA

- phosphatidic acid

- AP-1

- activator protein-1

- IL-8

- interleukin 8

- PKC

- protein kinase C

- GPCR

- G-protein-coupled receptor

- RTK

- receptor-tyrosine kinase

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- m.o.i.

- multiplicity of infection

Y. Zhao and V. Natarajan, unpublished data.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Leeuwen FN, Giepmans BN, van Meeteren LA, Moolenaar WH. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003;31:1209–1212. doi: 10.1042/bst0311209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saba JD. J. Cell. Biochem. 2004;92:967–992. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sengupta S, Wang Z, Tipps R, Xu Y. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;15:503–512. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toews ML, Ediger TL, Romberger DJ, Rennard SI. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1582:240–250. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svetlov SI, Sautin YY, Crawford JM. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1582:251–256. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toman RE, Spiegel S. Neurochem. Res. 2002;27:619–627. doi: 10.1023/a:1020219915922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.English D, Brindley DN, Spiegel S, Garcia JG. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1582:228–239. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00176-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukushima N, Chun J. Prostaglandins. 2001;64:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(01)00105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu SS, Chiu T, Rozengurt E. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002;282:1432–1444. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00323.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Facchini A, Borzi RM, Flamigni F. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2919–2925. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cummings R, Parinandi N, Wang L, Usatyuk P, Natarajan V. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2002;234-235:99–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, Cummings R, Zhao Y, Kazlauskas A, Sham JK, Morris A, Georas S, Brindley DN, Natarajan V. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:39931–39940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302896200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummings R, Zhao Y, Jacoby D, Spannhake EW, Ohba M, Garcia JGN, Watkins T, He D, Saatian B, Natarajan V. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:41085–41094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Y, Usatyuk PV, Cummings R, Saatian B, He D, Watkins T, Morris A, Spannhake EW, Brindley DN, Natarajan V. Biochem. J. 2005;385:493–502. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saatian B, Zhao Y, He D, Georas SN, Watkins T, Spannhake EW, Natarajan V. Biochem. J. 2005;393:657–668. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyamoto S, Hirata M, Yamazaki A, Kageyama T, Hasuwa H, Mizushima H, Tanaka Y, Yagi H, Sonoda K, Kai M, Kanoh H, Nakano H, Mekada E. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5720–5727. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah BH, Olivares-Reyes JA, Catt KJ. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;67:184–194. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.003533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmitz U, Thommes K, Beier I, Vetter H. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;291:687–691. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bektas M, Payne SG, Liu H, Goparaju S, Milstien S, Spiegel S. J. Cell Biol. 2005;169:801–811. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kue PF, Taub JS, Harrington LB, Polakiewicz RD, Ullrich A, Daaka Y. Int. J. Cancer. 2002;102:572–579. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SN, Park JG, Lee EB, Kim SS, Yoo YS. J. Cell. Biochem. 2000;76:386–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carpenter G. Sci STKE 2000. 2000 doi: 10.1126/stke.2000.15.pe1. PE1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah BH, Catt KJ. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;15:241–243. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luttrell LM. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2002;80:375–382. doi: 10.1139/y02-045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eguchi S, Frank GD, Mifune M, Inagami T. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003;6:1198–1202. doi: 10.1042/bst0311198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waters C, Connell MC, Pyne S, Pyne NJ. Cell Signal. 2005;17:263–277. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah BH, Baukal AJ, Shah FB, Catt KJ. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005;19:2535–2548. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pyne NJ, Waters C, Moughal NA, Sambi BS, Pyne S. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003;31:1220–1225. doi: 10.1042/bst0311220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goppelt-Struebe M, Fickel S, Reiser CO. Biochem. J. 2000;345:217–224. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pease JE, Sabroe I. Am. J. Respir. Med. 2002;1:19–25. doi: 10.1007/BF03257159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mukaida K. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2003;284:566–577. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00233.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strieter RM. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2002;283:688–689. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00146.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abul H, Abul A, Khan I, Mathew TC, Ayed A, Al-Athary E. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2001;217:107–112. doi: 10.1023/A:1007264411006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brat DJ, Bellail AC, Van Meir EG. Neuro-oncol. 2005;7:122–133. doi: 10.1215/S1152851704001061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ozal D, Aysan T, Solak ZA, Mogulkoc N, Veral A, Sebik F. Respir. Med. 2005;99:1494–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim CK, Kim SW, Kim YK, Kang H, Yu J, Yoo Y, Koh YY. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2005;35:591–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schierhorn K, Zhang M, Matthias C, Kunkel G. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1999;20:1013–1019. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.5.3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hellermann GR, Nagy SB, Kong X, Lockey RF, Mohapatra SS. Respir. Res. 2002;3:22. doi: 10.1186/rr172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Julkunen I, Melen K, Nyqvist M, Pirhonen J, Sareneva T, Matikainen S. Vaccine. 2000;19(Suppl 1):532–537. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00275-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richter a., O’Donnell RA, Powell RM, Sanders MW, Holgate ST, Djukanovic R, Davies DE. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2002;27:85–90. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.27.1.4789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saatian B, Yu XY, Lane AP, Doyle T, Casolaro V, Spannhake EW. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2004;287:217–225. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00132.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bernacki SH, Nelson AL, Abdullah L, Sheehan JK, Harris A, Davis CW, Randell SH. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1999;20:595–604. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.4.3442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lanzrein M, Garred O, Olsnes S, Sandvig K. Biochem. J. 1995;310:285–289. doi: 10.1042/bj3100285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amos S, Martin PM, Polar GA, Parsons SJ, Hussaini IM. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:7729–7738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409056200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eguchi S, Numaguchi K, Iwasaki H, Matsumoto T, Yamakawa T, Utsunomiya H, Motley ED, Kawakatsu H, Owada KM, Hirata Y, Marumo F, Inagami T. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:8890–8896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosen LB, Greenberg ME. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:1113–1118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frank GD, Mifune M, Inagamim T, Ohba M, Sasaki T, Higashiyaman S, Dempsey PJ, Eguchi S. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:1581–1589. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1581-1589.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Q, Thomas SM, Xi S, Smithgall TE, Siegfried JM, Kamens J, Gooding WE, Grandis JR. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6166–6173. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luttrell LM, Della Rocca GJ, van Biesen T, Luttrell DK, Lefkowitz RJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:4637–4644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uribe JM, McCole DF, Barrett KE. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2002;283:923–931. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00237.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sato K, Nagao T, Iwasaki T, Nishihira Y, Fukami Y. Genes Cells. 2003;8:995–1003. doi: 10.1046/j.1356-9597.2003.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim J, Ahn S, Guo R, Daaka Y. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2887–2894. doi: 10.1021/bi026942t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wan Y, Kurosaki T, Huang XY. Nature. 1996;380:541–544. doi: 10.1038/380541a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu Y, Harder KW, Hungtington ND, Hibbs ML, Tarlinton DM. Immunity. 2005;22:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lannutti BJ, Drachman JG. Blood. 2004;103:3736–3743. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brandt DT, Goerke A, Heuer M, Gimona M, Leitges M, Kremmer E, Lammers R, Haller H, Mischak H. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:34073–34078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211650200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joseloff E, Cataisson C, Aamodt H, Ocheni H, Blumberg P, Kraker AJ, Yuspa SH. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:12318–12323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111618200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hashimoto T, Yamashita M, Ohata H, Momose K. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2003;91:8–14. doi: 10.1254/jphs.91.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hamilton LM, Torres-Lozano CM, Puddicombe SM, Richter A, Kimber I, Dearman RJ, Vrugt B, Aalbers R, Holgate ST, Djukanovic R, Wilson SJ, Daview DE. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2003;33:233–240. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ediger TL, Danforth BL, Toews ML. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2002;282:91–98. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2002.282.1.L91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]