Abstract

Nitinol alloys are rapidly being utilized as the material of choice in a variety of applications in the medical industry. It has been used for self-expanding stents, graft support systems, and various other devices for minimally invasive interventional and endoscopic procedures. However, the biocompatibility of this alloy remains a concern to many practitioners in the industry due to nickel sensitivity experienced by many patients. In recent times, several new Nitinol alloys have been introduced with the addition of a ternary element. Nevertheless, there is still a dearth of information concerning the biocompatibility and corrosion resistance of these alloys. This study compared the biocompatibility of two ternary Nitinol alloys prepared by powder metallurgy (PM) and arc melting (AM) and critically assessed the influence of the ternary element. ASTM F 2129-08 cyclic polarization in vitro corrosion tests were conducted to evaluate the corrosion resistance in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The growth of endothelial cells on NiTi was examined using optical microscopy.

Keywords: biocompatibility, endothelial cells, nitinol, sintering, stents

1. Introduction

Shape Memory Alloys (SMAs) are a group of metallic materials that demonstrate the ability to return to some previously defined shape or size when subjected to an appropriate thermal or mechanical procedure. In general, these materials can be plastically deformed at some relatively low temperature, and on exposure to some higher temperature, return to their original shapes prior to the deformation. Materials that exhibit shape memory only on heating are referred to as having a one-way shape memory. Some materials also undergo a change in shape on re-cooling. These materials have a two-way shape memory.

Nitinol alloys are rapidly becoming the material of choice for self-expanding stents, graft support systems, filters, baskets, and various other devices for minimally invasive interventional and endoscopic procedures due to their excellent superelasticity, radiopacity and shape memory properties (Ref 1–6).

In this study, Nitinol alloys have been prepared using the powder metallurgy (PM) and arc melting (AM) methods. Tantalum (Ta) and Copper (Cu) have been added to NiTi as ternary elements. Tantalum imparts radiopacity, thermal stability, and control over transformation temperatures (Ref 3), whereas copper increases corrosion resistance and martensitic transformation temperature, and prevents Ti3Ni4 precipitation (Ref 4).

The susceptibility to corrosion of Nitinol alloys was evaluated by conducting Cyclic Polarization tests in accordance with ASTM F 2129-08 (Ref 7).

2. Materials

2.1 Metal Powders

All the metal powders were supplied by Atlantic Equipment Engineers (AEE), Bergenfield, NJ, USA. The size and purity of powders are shown below:

Nickel, 4–8 μm (99.9%)

Titanium, <20 μm (99.7%)

Tantalum, 1–5 μm (99.8%)

Copper, 1–5 μm (99.7%)

Ni, Ti, Ta, and Cu powders were used as starting materials for the production of three different Nitinol alloys by PM, i.e., NiTi, NiTiTa, and NiTiCu.

NiTi, NiTiTa, and NiTiCu pellets prepared by AM method were obtained from National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and were used for comparison.

2.2 Reagent

Phosphate buffered saline (PBS), a reagent grade chemical conforming to the specifications of the Committee on Analytical Reagents of the American Chemical Society was used as the standard test solution.

3. Methodology

3.1 Mixing

Pure metal powders were weighed in the appropriate proportions as shown in Table 1. These powders were mixed in a glove box that was first evacuated and then purged with argon to maintain a stable and inert atmosphere in order to minimize oxidation due to the reactive nature of very fine particles.

Table 1.

Alloy composition (in at.%)

| Ni, at.% | Ti, at.% | Ta or Cu, at.% |

|---|---|---|

| 51 | 49 | 0 |

| 48.45 | 46.55 | 5 |

3.2 Milling

A high-energy ball mill (SPEX 8000), equipped with a hardened steel vial (Ø 2¼ in. × 3 in.) as the milling container and stainless steel balls as the grinding medium, was used to alloy the metal powders mechanically. A milling speed of 1200 rpm, milling duration of 60 min, and a ball-to-powder ratio (BPR) of 10:1 were utilized for effective milling of the powders. The milled powder was collected and stored in an airtight container within the glove box for future usage (Ref 3).

3.3 Pelletizing

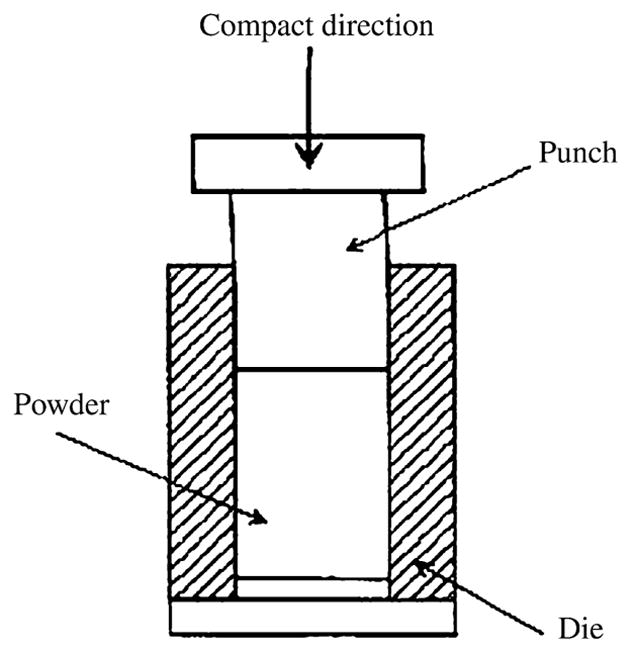

A stainless steel die was specially designed and manufactured (Fig. 1) for the consolidation of the milled powders into pellets. The powder was uni-axially cold pressed at 15,000 lbs force (66723 N) with a manual pellet press and held at that pressure for about 30 min to form the pellet. The pellet was then carefully ejected out of the die and stored in the glove box in separate labeled plastic boxes under argon.

Fig. 1.

Pelletizing die

3.4 Sintering

Pellets were sintered at 900 °C under argon, utilizing a ramp time of 25 min and a hold time of 2.5 h. Afterward, pellets were allowed to cool down to room temperature. These pellets were used to perform corrosion and biocompatibility studies.

4. Experimental Procedure

4.1 Comparative Corrosion Studies

All the pellets were polished with a series of 200, 320, and 600 grit SiC paper. The pellets were then degreased ultrasonically with acetone, rinsed in distilled water, and air dried.

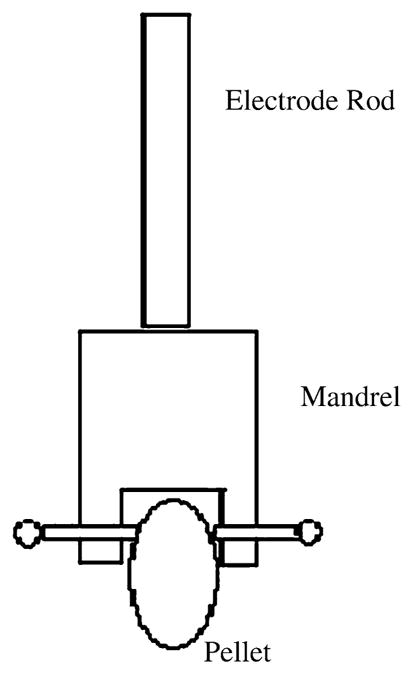

The corrosion cell was first cleaned with deionized water, rinsed with PBS solution, and filled with approximately 70 mL of PBS. The cell with PBS solution was brought up to 37 °C by placing it in a controlled temperature water bath, and the solution was purged with ultra high purity nitrogen for 30 min prior to immersion of the pellet (Fig. 2). A saturated calomel electrode was used as the reference electrode, and it was inserted into a Luggin Capillary. In order to increase the accuracy of the corrosion data, the surface area of the pellet in contact with PBS was carefully calculated. The cyclic polarization option was then selected on a GAMRY® Instrument Framework Software with a scan rate of 1 mV/s over a potential range between −0.5 and 2.2 VSCE.

Fig. 2.

The holding mandrel

4.2 Endothelial Cell Growth

Growth of endothelial cells on the NiTi alloys was assessed using the ISO 10993 protocols for biological evaluation of medical devices (Ref 8) by using an Olympus IX81 microscope. Cells were first cultured using F-12K medium in a 75 cm2 cell culture flask. When the cells reached confluency, they were trypsinized, centrifuged, and resuspended in culture media for cell counting and cell seeding. A solution of 500 μL of cell culture medium (seeding density 2 × 105 endothelial cells) was transferred to each NiTi alloy located in a 24-well plate. The well plate was then placed in an incubator for 72 h at 37 °C having 5% CO2.

5. Results and Discussion

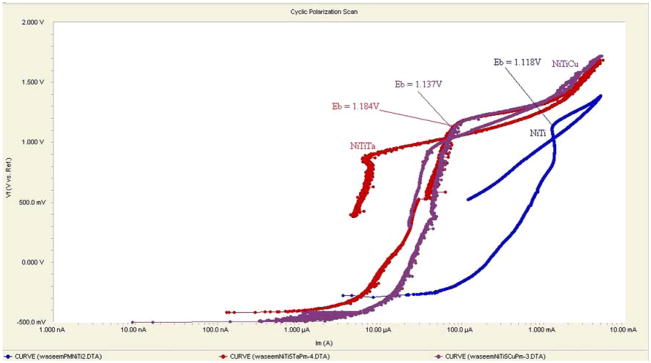

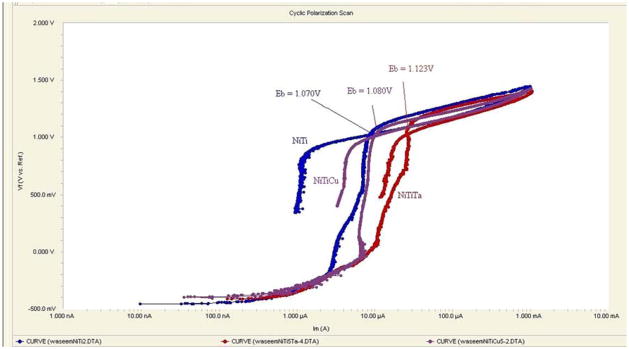

Table 2–7 show various corrosion parameters that were determined at 37 ± 1 °C for three types of Nitinol alloys prepared by two different methods using PBS as the electrolyte. Cyclic polarization curves for PM and AM Nitinol alloys are shown in Fig. 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 2.

Average corrosion parameters obtained for PM NiTi

| Corrosion parameters | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Sample 4 | Sample 5 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eb, V | 1.121 | 1.118 | 1.168 | 1.170 | 1.169 | 1.149 |

| Er, V | −0.005 | −0.277 | −0.367 | −0.351 | −0.140 | −0.228 |

| Ep, V | 1.024 | 1.033 | 1.094 | 1.128 | 1.125 | 1.080 |

| Eb − Er, V | 1.126 | 1.395 | 1.535 | 1.521 | 1.309 | 1.377 |

Table 7.

Average corrosion parameters obtained for AM NiTiCu

| Corrosion parameters | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Sample 4 | Sample 5 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eb, V | 1.116 | 1.080 | 1.123 | 1.016 | 1.110 | 1.089 |

| Er, V | −0.531 | −0.398 | −0.474 | −0.541 | −0.536 | −0.496 |

| Ep, V | 1.101 | 1.016 | 1.041 | 0.891 | 1.076 | 1.025 |

| Eb − Er, V | 1.647 | 1.478 | 1.597 | 1.557 | 1.646 | 1.585 |

Fig. 3.

Cyclic polarization curves of PM Nitinol alloys

Fig. 4.

Cyclic polarization curves of AM Nitinol alloys

The true measure of a material’s pitting corrosion resistance is usually associated with the breakdown potential, Eb, as well as the gap, Eb − Er. It appeared that NiTiTa prepared by both PM and AM had the greatest corrosion resistance among the three alloys as indicated by the highest Eb. NiTiCu alloy exhibited a corrosion resistance value lying those of between NiTiTa and NiTi.

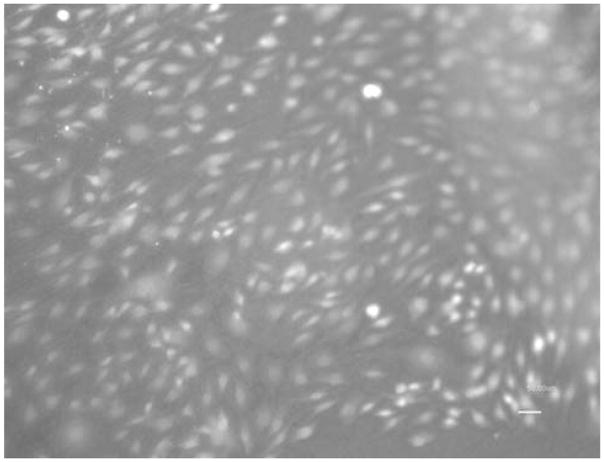

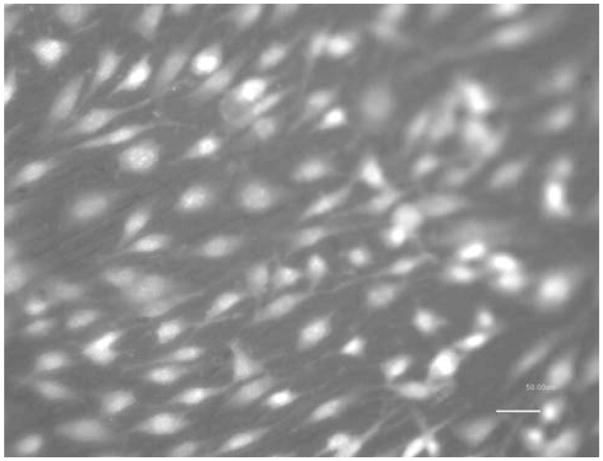

Figures 5 and 6 show the photomicrographs of endothelial cells on NiTi alloy after 72 h. The cells appeared to be healthy, and the growth was prolific.

Fig. 5.

Endothelial cell growth on AM NiTi (10×)

Fig. 6.

Endothelial cell growth on AM NiTi (20×)

6. Conclusions

Cyclic polarization corrosion tests performed on NiTi, NiTiTa, and NiTiCu alloys revealed that the breakdown potential increased as Cu or Ta was added as the ternary element, with NiTiTa being the most resistant to pitting corrosion. Based on the results of cyclic polarization tests, PM alloys appeared to be more resistant to pitting corrosion as compared with AM alloys. The growth and viability of endothelial cells on NiTi were prolific. However, the effect of the ternary elements Ta and Cu on endothelial cell growth will be the focus of future work.

Table 3.

Average corrosion parameters obtained for PM NiTiTa

| Corrosion parameters | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Sample 4 | Sample 5 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eb, V | 1.200 | 1.144 | 1.561 | 1.184 | 1.112 | 1.240 |

| Er, V | −0.403 | −0.459 | −0.372 | −0.418 | −0.527 | −0.435 |

| Ep, V | … | 1.027 | 1.513 | 1.035 | 1.029 | 1.151 |

| Eb − Er, V | 1.603 | 1.603 | 1.933 | 1.602 | 1.639 | 1.675 |

Table 4.

Average corrosion parameters obtained for PM NiTiCu

| Corrosion parameters | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Sample 4 | Sample 5 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eb, V | 1.099 | 1.354 | 1.137 | 1.186 | 1.170 | 1.189 |

| Er, V | −0.478 | −0.477 | −0.498 | −0.365 | −0.488 | −0.461 |

| Ep, V | 0.991 | 1.275 | 1.021 | … | 1.099 | 1.096 |

| Eb − Er, V | 1.577 | 1.831 | 1.635 | 1.551 | 1.658 | 1.650 |

Table 5.

Average corrosion parameters obtained for AM NiTi

| Corrosion parameters | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Sample 4 | Sample 5 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eb, V | 1.082 | 1.060 | 1.070 | 1.016 | 1.110 | 1.067 |

| Er, V | −0.492 | −0.458 | −0.508 | −0.541 | −0.536 | −0.507 |

| Ep, V | 1.010 | 1.026 | 1.007 | 0.891 | 1.076 | 1.002 |

| Eb − Er, V | 1.574 | 1.518 | 1.578 | 1.557 | 1.646 | 1.574 |

Table 6.

Average corrosion parameters obtained for AM NiTiTa

| Corrosion parameters | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Sample 4 | Sample 5 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eb, V | 1.101 | 1.102 | 1.132 | 1.123 | 1.131 | 1.117 |

| Er, V | −0.565 | −0.485 | −0.592 | −0.501 | −0.451 | −0.518 |

| Ep, V | 0.996 | 1.070 | 1.078 | 1.029 | 1.044 | 1.043 |

| Eb − Er, V | 1.666 | 1.587 | 1.724 | 1.624 | 1.582 | 1.635 |

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Award Number SC3GM084816 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

This article is an invited paper selected from presentations at Shape Memory and Superelastic Technologies 2008, held September 21–25, 2008, in Stresa, Italy, and has been expanded from the original presentation.

References

- 1.Shabalovakaya S. Physicochemical and Biological Aspects of Nitinol as a Biomaterial. Int Mater Rev. 2001;46(4):230–250. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryhanen J, Niemi E, Serlo W, Niemela E, Sandvick P, Pernu H, Salo T. Biocompatibility of Nickel-Titanium Shape Memory Metal and Its Corrosion Behavior in Human Cell Cultures. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997;35(4):451–457. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19970615)35:4<451::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanchibbolta S, Munroe N. Amorphization in Ni-Ti-Ta System Through Mechanical Alloying. J Mater Sci. 2005;40(18):5003–5006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goryczka T, Humbeeck JV. NiTiCu Shape Memory Alloy Produced by Powder Technology. J Alloys Compd. 2008;456:194–200. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munroe ND, Haider W, Wu KH, Datye A. Corrosion Behavior of Electropolished Implant Alloys. Proceedings of the International Conference on Shape Memory and Superelastic Technologies; December 3–5, 2007; Tsukuba, Japan. pp. 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munroe ND, Haider W, Wu KH, Datye A. Corrosion Behavior of Cardiovascular Stent Materials. Proceedings of the International Conference on Shape Memory and Superelastic Technologies; December 3–5, 2007; Tsukuba, Japan. pp. 299–306. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Standard Test Method for Conducting Cyclic Potentiodynamic Polarization Measurements to Determine the Corrosion Susceptibility of Small Implant Devices, ASTM F 2129-08, Annual Book of ASTM Standards

- 8.Anand VP. Biocompatibility Safety Assessment of Medical Devices: FDA/ISO & Japanese Guidelines. MD & DI. 2000 January;:206–216. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otsuka K, Kakeshita T. Science and Technology of Shape-memory Alloys: New Developments. MRS Bulletin. 2002 February;:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma JL. Master thesis. Florida International University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanchibhotla S. Master thesis. Florida International University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bram M, Ahmad-Khanlou A, Heckmann A, Fuchs B, Buchkremer HP, Stover D. Powder Metallurgical Fabrication Processes for NiTi Shape Memory Alloy Parts. Mater Sci Eng A. 2002;337:254–263. [Google Scholar]