Abstract

In budding yeast, phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C (Plc1p encoded by PLC1 gene) and several inositol polyphosphate kinases represent a nuclear pathway for synthesis of inositol polyphosphates (InsPs) that are involved in several aspects of DNA and RNA metabolism, including transcriptional regulation. Plc1p-produced InsP3 is phosphorylated by Ipk2p/Arg82p to yield InsP4/InsP5. Ipk2p/Arg82p is also a component of ArgR-Mcm1p complex that regulates transcription of genes involved in arginine metabolism. The role of Ipk2p/Arg82p in this complex is to stabilize the essential MADS box protein Mcm1p. Consequently, ipk2Δ cells display reduced level of Mcm1p and attenuated expression of Mcm1p-dependent genes. Since plc1Δ cells display aberrant expression of several groups of genes, including genes involved in stress response, the objective of this study was to determine whether Plc1p also affects expression of Mcm1p-dependent genes. We report here that not only ipk2Δ, but also plc1Δ cells display decreased expression of Mcm1p-dependent genes. However, Plc1p is not involved in stabilization of Mcm1p and affects transcription of Mcm1p-dependent genes by a different mechanism, probably involving regulation of chromatin remodeling complexes.

Keywords: phospholipase C, MCM1, transcriptional regulation, inositol polyphosphates

Introduction

In budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, phospholipase C (Plc1p encoded by PLC1 gene) and four inositol polyphosphate kinases (Ipk2p/Arg82p, Ipk1p, Kcs1p, and Vip1p) constitute a nuclear signaling pathway that is responsible for synthesis of inositol polyphosphates (InsPs) and affects transcriptional control (Odom, et al., 2000), export of mRNA from the nucleus (York, et al., 1999), homologous DNA recombination (Luo et al., 2002), cell death, and telomere length (Saiardi et al., 2005; York et al., 2005). Hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate by phospholipase C yields inositol trisphosphate (InsP3) and diacylglycerol, and is the only pathway for InsPs synthesis in budding yeast cells. Ipk2p/Arg82p is a dual specificity kinase that converts Plc1p-generated InsP3 into InsP5 via InsP4 (Odom et al., 2000). InsP4 and InsP5 are involved in transcription by regulating chromatin remodeling complexes (Shen et al., 2003; Steger et al., 2003). InsP5 is subsequently converted to InsP6 by Ipk1p. InsP6 is an effector molecule that regulates mRNA export from the nucleus (York et al., 1999). The mechanism involves binding of InsP6 by nuclear pore protein Gle1p and stimulation of RNA-dependent ATPase activity of Dbp1p, which is essential for nuclear mRNA export (Weirich et al., 2006; Alcazar-Roman et al., 2006). Kcs1p and Vip1p are InsP6 and InsP7 kinases responsible for synthesis of 5-PP-InsP5 and 4-PP-InsP5/6-PP-InsP5, respectively (Saiardi et al., 1999, 2000; Mulugu et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2007). Ultimately, Kc1p and Vip1p can produce InsP8 molecules 4,5-PP2-InsP4 and 5,6-PP2-InsP4. It appears that inositol pyrophosphates are required for number of cellular functions, including inhibition of Pho80p-Pho85p cyclin-CDK complex by the Pho81p inhibitor (Lee et al., 2007; Luo et al., 2002; Saiardi et al., 2005; York et al., 2005).

Ipk2p/Arg82p is together with Arg80p, Arg81p, and Mcm1p a component of the transcriptional complex ArgR-Mcm1 that regulates transcription of genes involved in arginine metabolism (El Bakkoury et al., 2000). When arginine is present, these four proteins repress synthesis of arginine biosynthetic enzymes and induce synthesis of catabolic enzymes. Arg80p and Arg81p are specific regulators of the arginine system, while Ipk2p/Arg82p and Mcm1p are global regulators involved in other processes as well (Dubois & Messenguy, 1991, Messenguy & Dubois, 1993). Arg81p is the sensor of arginine that interacts with the two MADS box proteins Arg80p and Mcm1p to form a complex at the promoters of arginine regulated genes (El Bakkoury et al., 2000; Messenguy and Dubois, 2003). Mcm1p is an essential protein that plays a role in transcription of genes involved in M/G1 and G2/M cell-cycle progression, mating, recombination, and stress tolerance (Messenguy and Dubois, 2003). The role of Ipk2p/Arg82p in the regulation of arginine-responsive genes consists in binding and stabilizing both Arg80p and Mcm1p but does not involve its InsP3 kinase activity. However, the kinase activity of Arg82p is required for proper expression of genes regulated by phosphate and nitrogen (El Alami et al., 2003).

Using genome-wide expression analysis our laboratory found previously that not only ipk2Δ, but also plc1Δ cells display decreased expression of Mcm1-dependent genes (Demczuk, et al., 2008). Hence, in this study our objective was to determine whether Plc1p in addition to Ipk2p is also required for stabilization of Mcm1p and thus for expression of Mcm1p-dependent genes. In this report we demonstrate that Plc1p is required for expression of Mcm1-depended genes, however, it does not affect the stability of Mcm1p. Therefore, Plc1p affects expression of Mcm1-depended genes by a different mechanism, probably by affecting the activity of chromatin remodeling complexes.

Materials and Methods

Strains and media

All yeast strains are listed in Table 1. Standard genetic techniques were used to manipulate yeast strains and to introduce mutations from non-W303 strains into the W303 background (Sherman, 1991). Cells were grown in rich medium (YPD; 1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto-peptone, 2% glucose) or under selection in synthetic complete medium (CSM) containing 2% glucose and, when appropriate, lacking specific nutrients in order to select for a plasmid or strain with a particular genotype. Meiosis was induced in diploid cells by incubation in 1% potassium acetate.

Table 1. Yeast strains used in this study.

| Strain | Genotype | Source/ reference |

|---|---|---|

| W303-1a | MATa ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 ssd1-d2 can1-100 | R. Rothstein |

| W303-1α | MATα ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 ssd1-d2 can1-100 | R. Rothstein |

| HL1-1 | W303-1α plc1∷URA3 | Lin, et al. (2000) |

| HL1-3 | W303-1a plc1∷URA3 | De Lillo et al. (2003) |

| AOY138 | W303-1α ipk2∷kanMX | York et al. (2005) |

| A0004 | W303-1α ipk1∷kanMX | York et al. (1999) |

| YSC1178-7502110 | MATa his3 Δ 1 leu2 Δ 0 met15 Δ 0 ura3 Δ 0 MCM1-TAP∷HIS3 | Open Biosystems |

| KG026 | W303-1a MCM1-TAP∷HIS3 | This study |

| KG002 | W303-1a plc1∷URA3 MCM1-TAP∷HIS3 | This study |

| KG022 | W303-1a ipk2∷kanMX MCM1-TAP∷HIS3 | This study |

B-Galactosidase Assays

Wild-type, plc1Δ, and ipk2Δ strains were transformed with the following plasmids: pFV55 (CLN3-LacZ), pFV56 (FAR1-LacZ), pFV57 (PIS1-LacZ), pFV58 (CDC6- LacZ), and pFV60 (PMA1-LacZ) (El Bakkoury, et al., 2000). The transformants were grown under selection in CSM-Ura medium at 30°C and subsequently diluted in YPD medium to an A600 nm of 0.2 and grown until the culture reached A600 nm ∼ 1.0. Cells from 10 ml culture were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in β-galactosidase breaking buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM DTT, 20 % glycerol) containing protease inhibitors (Roche; Complete protease inhibitors) and 2 mM PMSF (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Samples were disrupted by vortexing with glass beads, and 10-100 μl of the collected supernatant was added to 0.9 ml of Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4.7H2O; 40 mM NaH2PO4.H2O; 10 mM KCl; 1 mM MgSO4, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.0). The volume was adjusted up to 1 ml with β-galactosidase breaking buffer and the assay mixture incubated in water bath at 28°C for 5 min with moderate shaking. Reaction was initiated by adding 0.2 ml of o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG; 4 mg/ml in Z buffer) and continued at 28°C until mixture turned pale yellow and terminated by addition of 0.5 ml of 1 M Na2CO3 (Choi et al., 1998). Protein concentration was determined using the Coomassie Plus protein assay kit (Pierce). The specific activity was expressed in terms of nanomoles of ONPG hydrolyzed per minute per mg of protein.

Real-time RT- PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cultures grown in YPD medium to optical density A600nm ∼ 1.0 by the hot phenol method as described previously (Iyer & Struhl, 1996), treated with RNase-free DNase (Qiagen), and purified with an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). RT and real-time PCR amplification using BioRad MyIQ single color real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) were performed with iScript kit (BioRad), 100 ng of RNA, and the following primers: ACT1 (5′-TATGTGTAAAGCCGGTTTTGC-3′and 5′-GACAATACCGTGTTCAATTGGG-3′), STE2 (5′-ACCATCACTTTCGATGAGT TGC-3′ and 5′-GGTTGATAATGAAAATCGGCG-3′), STE3 (5′-CCTTTAGCAT GGCATTCACATAC-3′ and 5′-GATATGCCAATATTCGCACCAAC-3′), BAR1 (5′-ACGAAGAGGAGATGTATTACGCAAC-3′and 5′-ACCTGCAATCAATTGAAGGC-3′), MFalpha1 (5′-GCTGAAGCTGTCATCGGTTACTTAG-3′ and CCAGGTTTT AGTTGCAACCAATG-3′).

Western blotting

Yeast cultures were grown in 200 ml YPD to an optical density A600nm =1.0. To determine the Mcm1p stability, 20 μg/ml cycloheximide (CYH) was added at time zero. At different time points after the treatment, cells from 30 ml of the culture were harvested by centrifugation and subsequently converted to spheroplasts using yeast lytic enzyme (Sigma; 700 U/ml in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, containing10 % sucrose). Protein concentration of the samples was determined using Coomassie Plus protein assay kit (Pierce). Denatured proteins were separated on 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and Western blotting with 0.5 μg/ml of anti-TAP antibody (Open Biosystems) was carried out as described previously (Demczuk et al., 2008) and the blots were visualized using GeneGnome Bioimaging System (Syngene). To confirm equivalent amounts of loaded proteins, the membrane was stripped and incubated with anti-3-phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) antibody (Molecular Probes).

Results and Discussion

To identify transcriptional targets of InPs, our laboratory performed genome-wide expression analysis with wild-type, plc1Δ, ipk2Δ, and ipk1Δ strains (Demczuk et al., 2008). In addition to increased expression of Msn2p-dependent stress-responsive genes in plc1Δ cells, we also observed decreased expression of cell-type-specific and Mcm1p - dependent genes such as BAR1, MFA1 and STE2 in ipk2Δ strain (Demczuk et al., 2008). This was not entirely surprising, since ipk2Δ cells display decreased stability of Mcm1p (El Bakhoury et al., 2000). However, several of the Mcm1p-dependent genes were expressed at a lower level also in the plc1Δ cells (Demczuk et al., 2008). These results suggested that Plc1p and/or synthesis of InsPs may be required for full expression of Mcm1p-dependent genes, perhaps also by affecting the stability of Mcm1p. One possible model that could account for the stabilizing effect of InsP3 on Mcm1p would involve assumption that Ipk2p/Arg82 must bind InsPs in order to stabilize Mcm1p.

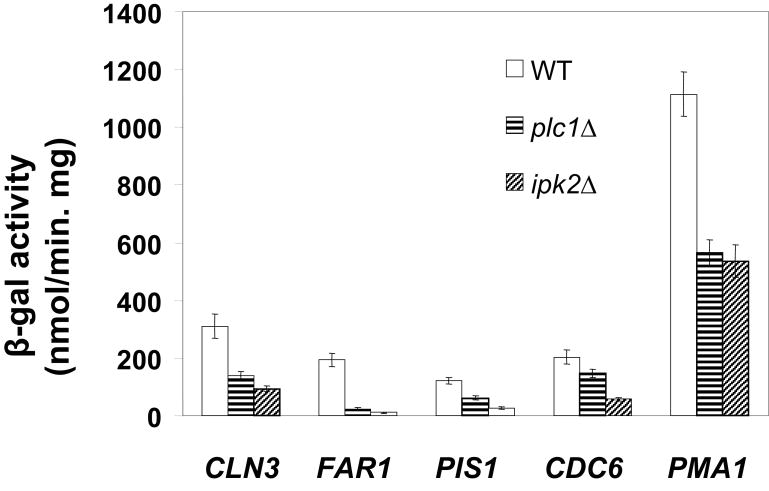

To analyze the involvement of Plc1p and InsP3 in the control of Mcm1-dependent genes, wild-type, plc1Δ, and ipk2Δ strains were transformed with plasmids containing lacZ reporter gene under the control of Mcm1p-regulated promoters of CLN3, FAR1, PIS1, CDC6 and PMA1 (El Bakkoury, et al., 2000). As reported previously (El Bakkoury, et al., 2000), β-galactosidase activities were strongly reduced in ipk2Δ strain in comparison to wild-type strain. In plc1Δ strain the activities were also reduced, however to a lesser extent than in the ipk2Δ strain (Fig. 1). These results thus suggest that Plc1p is also required for full expression of Mcm1p-dependent genes, however, Plc1p appears to be less important than Ipk2p.

Figure 1. plc1Δ cells display reduced expression of Mcm1p-dependent genes.

Wild-type, plc1Δ, and ipk2Δ strains were transformed with plasmids containing lacZ reporter genes under the control of the indicated Mcm1p-regulated promoters (El Bakkoury et al., 2000). The β-galactosidase assays were carried out as described previously (Choi et al., 1998) and the values were calculated from three independent experiments and represent means ± SD.

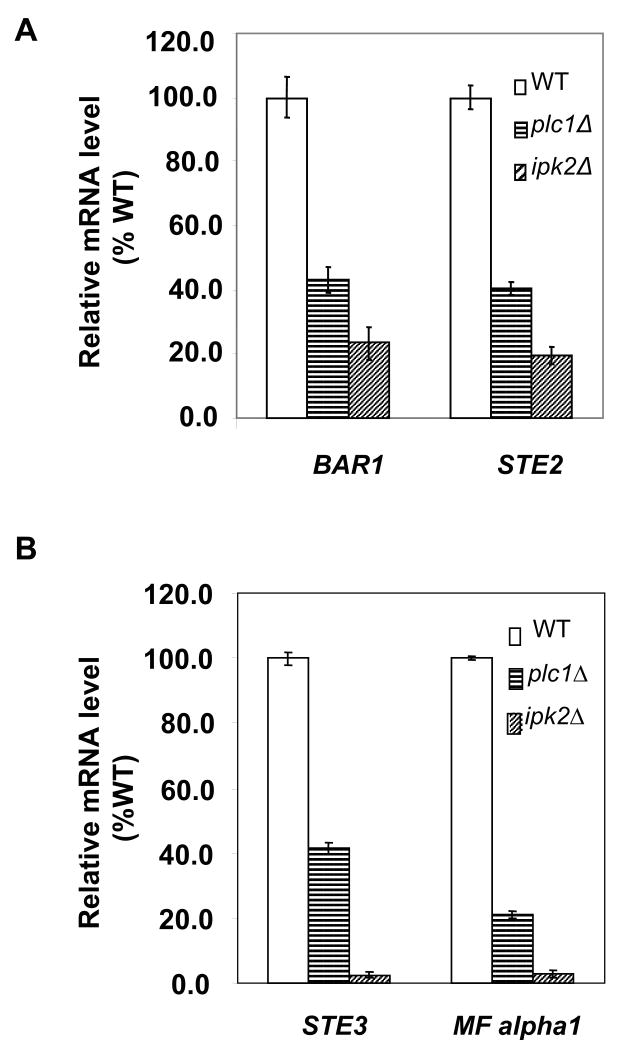

Since the expression of Mcm1p-dependent genes might be affected by promoter chromatin structure that may not be faithfully reconstituted in the context of reporter plasmids, we determined expression of several Mcm1p-dependent genes in their normal chromosomal locations. RNA was isolated from both MATa and MATα cells of wild-type, plc1Δ, and ipk2Δ strains, and the relative transcript levels of a-specific genes (BAR1, STE2) and α-specific genes (STE3 and MFα1) were determined. In MATα cells, cell-type specific transcriptional factor Matα1p and Mcm1p bind cooperatively to promoters of corresponding genes, thus activating α -cell-type-specific gene expression. In a cells, Mcm1p activates transcription of a - specific genes by binding to the Mcm1-binding site found in promoter regions of a - specific genes. Thus, expression of α – specific genes in MATα cells as well as expression of a – specific genes in MATa cells requires Mcm1p. Previous studies have shown that Ipk2p is required for the expression of certain a - and α - specific genes that are also controlled by Mcm1p (Dubois and Messenguy, 1994). As shown in Figure 2A, the transcription levels of a - specific genes BAR1 and STE2 in ipk2Δ mutant were significantly lower than those found in wild-type cells. The same pattern was observed in plc1Δ strain, however, the decrease was not as dramatic as in ipk2Δ strain (Fig. 2A). The transcript levels of α - specific genes STE3 and MFα1 in ipk2Δ strain were also significantly reduced as compared to wild-type. Again, the pattern observed in plc1Δ strain was similar but the decrease was not as dramatic as in ipk2Δ strain (Fig 2B).

Figure 2. plc1Δ cells display reduced expression of cell-type-specific genes.

The indicated strains were grown in YPD medium at 30°C to A600nm=1.0 and the total RNA was isolated and assayed for ACT1, BAR1, STE2, STE3, and MF alpha 1 transcripts by real time RT-PCR. The results were normalized to ACT1 RNA and expressed as relative values in comparison to corresponding WT strain. The experiment was repeated three times and the results represent means ± S.D. (A) Expression of a – specific genes BAR1 and STE2 in Mata cells. (B) Expression of α – specific genes STE3 and MF alpha1 in MATα cells.

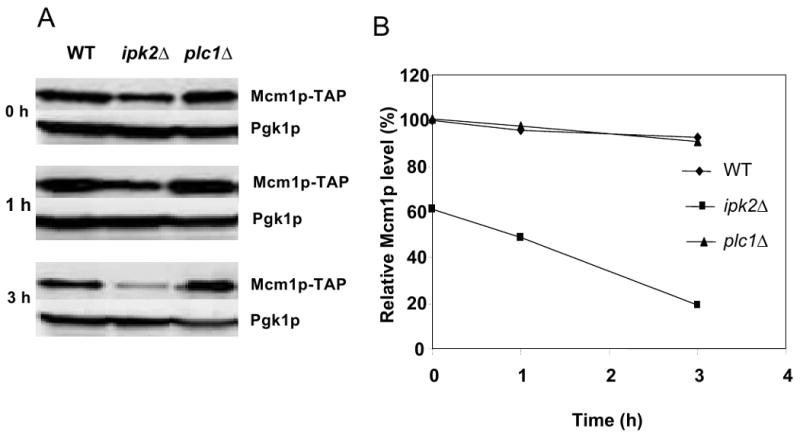

The above results support the conclusion that not only Ipk2p, but also Plc1p is important for full expression of Mcm1p-dependent genes. However, the ipk2Δ mutation affects expression of Mcm1p-dependent genes more significantly than plc1Δ mutation. Since Ipk2p affects expression of Mcm1p-dependent genes by physically interacting with and stabilizing Mcm1p (El Bakkoury et al., 2000; El Alami et al., 2003), we considered possibility that Plc1p also affects intracellular level of Mcm1p. There are several indications that Plc1p may be involved in regulation of stability of certain proteins. First, 26S proteasome-mediated destruction of C-type cyclin Ume3p/Srb11p/Ssn3p upon oxidative stress requires Plc1p (Cooper et al., 1999). Second, genome-wide identification of protein complexes revealed that Plc1p interacts with Caf130p (Krogan et al., 2006), a component of Ccr4/Not transcriptional regulatory complex. One of the subunits of the Ccr4-Not complex is Not4p, an ubiquitin E3 ligase (Albert et al., 2002; Collart, 2003) that interacts with Ubc4p, another ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. In addition, the Ccr4-Not complex associates with the proteasome (Laribee et al., 2007). These findings suggest that at least fraction of Plc1p is found in a molecular complex with ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and proteasome. In addition, we have described previously that Plc1p is required for recruitment of histone aceryltransferase complex SAGA to Sko1p-regulated promoters (Guha et al., 2007). Coincidentaly, the proteasome 19S regulatory particle was found to facilitate loading of SAGA onto chromatin (Lee et al., 2005). These findings prompted us to test whether Plc1p, similarly to Ipk2p, affects stability of Mcm1p. We examined stability of TAP-tagged Mcm1p in WT, plc1Δ, and ipk2Δ strains. The cells were grown in YPD medium to early exponential phase and subsequently treated with cycloheximide (CYH) to block protein synthesis. Mcm1p levels were determined by Western blotting using anti-TAP antibodies. In comparison with wild-type cells, the amount of Mcm1p in ipk2Δ strains is reduced to about 60% before treatment with CYH and to about 20% after 3 h treatment with CYH (Fig. 3). This result demonstrates that Mcm1p is less stable in ipk2Δ strain and agrees with previous results that showed that Ipk2p is required for Mcm1p stability (El Bakkoury, et al., 2000). In contrast, 3 h treatment with CYH in wild-type as well as plc1Δ cells reduced Mcm1p level only to 90% (Fig. 3). Thus, Plc1p is not required for Mcm1p stability and Plc1p and/or synthesis of InsP3 affect expression of Mcm1p-dependent genes by a different mechanism. Since InsPs regulate promoter recruitment and activity of chromatin remodeling complexes such as Swi/Snf and Ino80 (Shen et al., 2003; Steger et al., 2003), it is likely that reduced recruitment and/or activity of chromatin remodeling complexes in plc1Δ cells is responsible for decreased expression of Mcm1p-dependent genes. Future experiments will address the role of InsPs in regulation of chromatin remodeling complexes and expression of Mcm1p-dependent genes.

Figure 3. Plc1p is not required for Mcm1p stability.

(A) Wild-type, ipk2Δ, and plc1Δ cells expressing TAP-tagged Mcm1p were grown in YPD medium to early exponential phase (A600nm = 1.0) and subsequently treated with cycloheximide to block protein synthesis. Mcm1p-TAP levels were determined by Western blotting using anti-TAP antiobody before addition of cycloheximide and after 1 and 3 h. Even loading of protein samples was confirmed with anti-3-phosphoglycerate (Pgk1p) antibody. The experiment was performed three times, and representative results are shown. (B) Densitometric evaluation of the representative Western blot.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Messenguy, Wente, and York for strains and plasmids and members of Vancura lab for helpful comments. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM076075) to A.V.

References

- Albert TK, Hanzawa H, Legtenberg YIA, de Ruwe MJ, van den Heuvel FAJ, Collart MA, Boelens R, Timmers HTM. Identification of aubiquitin-protein ligase subunit within the CCR4-NOT transcription repressor complex. EMBO J. 2002;21:355–364. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.3.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcazar-Roman AR, Tran EJ, Guo S, Wente S. Inositol hexakisphosphate and Gle1 activate the DEAD-box protein Dbp5 for nuclear mRNA export. Nature Cell Biol. 2006;8:711–716. doi: 10.1038/ncb1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature. 1993;361:315–325. doi: 10.1038/361315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JH, Lou W, Vancura A. A novel membrane-bound glutathione S-transferase functions in the stationary phase of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29915–29922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collart MA. Global control of gene expression in yeast by the Ccr4-Not complex. Gene. 2003;313:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00672-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper KF, Mallory MJ, Strich R. Oxidative stress-induced destruction of the yeast C-type cyclin Ume3p requires phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C and the 26S proteasome. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3338–3348. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demczuk A, Guha N, Nguyen PH, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae phospholipase C regulates transcription of Msn2p-dependent stress-responsive genes. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:967–979. doi: 10.1128/EC.00438-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois E, Messenguy F. In vitro studies of the binding of the ARGR proteins to the ARG5,6 promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:2162–2168. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois E, Messenguy F. Pleiotropic function of ArgRIIIp (Arg82p), one of the regulators of arginine metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Role in expression of cell-type-specific genes. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;243:315–324. doi: 10.1007/BF00301067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois E, Dewaste V, Erneux C, Messenguy F. Inositol polyphosphate kinase activity of Arg82/ArgRIII is not required for the regulation of the arginine metabolism in yeast. FEBS Lett. 2000;486:300–304. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Alami M, Messenguy F, Scherens B, Dubois E. Arg82p is a bifunctional protein whose inositol polyphosphate kinase activity is essential for niotrogen and PHO gene expression but not for Mcm1p chaperoning in yeast. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:457–468. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Bakkoury M, Dubois E, Messenguy F. Recruitment of the yeast MADS-box proteins, ArgRI and Mcm1 by the pleiotropic factor ArgRIII is required for their stability. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:15–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elble R, Tye BK. Both activation and repression of a-mating-type-specific genes in yeast require transcription factor Mcm1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:10966–10970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guha N, Desai P, Vancura A. Plc1p is required for SAGA recruitment and derepression of Sko1p-regulated genes. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2419–2428. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-10-0946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen DC, Bruhn L, Westby CA, Sprague GF., Jr Transcription of alpha-specific genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: DNA sequence requirements for activity of the coregulator alpha 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6866–6875. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.11.6866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang-Shum JJ, Hagen DC, Jarvis EE, Westby CA, Sprague GF., Jr Relative contributions of MCM1 and STE12 to transcriptional activation of a- and alpha-specific genes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;227:197–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00259671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer V, Struhl K. Absolute mRNA levels and transcriptional initiation rates in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:5208–5212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan NJ, Cagney G, Yu H, et al. Global landscape of protein complexes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2006;440:637–643. doi: 10.1038/nature04670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo MH, Grayhack E. A library of yeast genomic MCM1 binding sites contains genes involved in cell cycle control, cell wall and membrane structure, and metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:348–359. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laribee RN, Shibata Y, Mersman DP, Collins SR, Kemmeren P, Roguev A, Weissman JS, Briggs SD, Krogan NJ, Strahl BD. CCR4/NOT complex associates with the proteasome and regulates histone methylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5836–5841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607996104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Ezhkova E, Li B, Pattenden SG, Tansey WP, Workman JL. The proteasome regulatory particle alters the SAGA coactivator to enhance its interactions with transcriptional activators. Cell. 2005;123:423–436. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, Mulugu S, York JD, O'Shea EK. Regulation of a cyclin-CDK-CDK inhibitor complex by inositol pyrophosphates. Science. 2007;316:109–112. doi: 10.1126/science.1139080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo HR, Saiardi A, Yu H, Nagata E, Ye K, Snyder SH. Inositol pyrophosphates are required for DNA hyperrecombination in protein kinase C1 mutant yeast. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2509–2515. doi: 10.1021/bi0118153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead J, Bruning AR, Gill MK, Steiner AM, Acton TB, Vershon AK. Interactions of the Mcm1 MADS box protein with cofactors that regulate mating in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4607–4621. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4607-4621.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messenguy F, Dubois E. Genetic evidence for a role for MCM1 in the regulation of arginine metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2586–2592. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messenguy F, Dubois E. Role of MADS box proteins and their cofactors in combinatorial control of gene expression and cell development. gene. 2003;316:1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00747-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulugu S, Bai W, Fridy PC, Bastidas RJ, Otto JC, Dollins DE, Haystead TA, Ribeiro AA, York JD. A conserved family of enzymes that phosphorylate inositol hexakisphosphate. Science. 2007;316:106–109. doi: 10.1126/science.1139099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka Y. Intracellular signaling by hydrolysis of phospholipids and activation of protein kinase C. Science. 1992;258:607–614. doi: 10.1126/science.1411571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom AR, Stahlberg A, Wente SR, York JD. A role for nuclear inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate kinase in transcriptional control. Science. 2000;287:2026–2029. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiardi A, Erdjument-Bromage H, Snowman AM, Tempst P, Snyder SH. Synthesis of diphosphoinositol pentakisphosphate by a newly identified family of higher inositol polyphosphate kinase. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1323–1326. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiardi A, Caffrey JJ, Snyder SH, Shears SB. The inositol hexakisphosphate kinase family. Catalytic flexibility and function in yeast vacuole biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:24686–24692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiardi A, Resnick AC, Snowman AM, Wendland B, Snyder SH. Inositol pyrophosphates regulate cell death and telomere length through phosphoinositide 3-kinase-related protein kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1911–1914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409322102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Xiao H, Ranallo R, Wu WH, Wu C. Modulation of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes by inositol polyphosphates. Science. 2003;299:112–114. doi: 10.1126/science.1078068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:3–21. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94004-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger DJ, Haswell ES, Miller AL, Wente SR, O'Shea EK. Regulation of chromatin remodeling by inositol polyphosphates. Science. 2003;299:114–116. doi: 10.1126/science.1078062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weirich CS, Erzberger JP, Flick JS, Berger JM, Thorner J, Weis K. Activation of the DExD/H-box protein Dbp5 by the nuclear-pore protein Gle1 and its coactivator InsP6 is required for mRNA export. Nature Cell Biol. 2006;8:668–676. doi: 10.1038/ncb1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York JD, Odom AR, Murphy R, Ives EB, Wente SR. A phospholipase C-dependent inositol polyphosphate kinase pathway required for efficient messenger RNA export. Science. 1999;285:96–100. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York SJ, Armbruster BN, Greenwell P, Petes TD, York JD. Inositol diphosphate signaling regulates telomere length. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4264–4269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412070200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]