Abstract

Electrically evoked dopamine release as measured by voltammetry in the rat striatum is heterogeneous in both amplitude and temporal profile. Previous studies have attributed this heterogeneity to variations in the density of DA terminals at the recording site. We reach the alternate conclusion that the heterogeneity of evoked DA release derives from variations in the extent to which DA terminals are autoinhibited. We demonstrate that low-amplitude, slow evoked DA responses occur even though recording electrodes are close to DA terminals. Moreover, the D2 agonist and antagonist, quinpirole and raclopride, respectively, affect the slow responses in a manner consistent with the known functions of presynaptic D2 autoreceptors. Recording sites that exhibit autoinhibited responses are prevalent in the dorsal striatum. Autoinhibition preceded electrical stimulation, which is consistent with our prior reports that the striatum contains a tonic pool of extracellular DA at basal concentrations that exceed the affinity of D2 receptors. We conclude that the striatum contains DA terminals operating on multiple time courses, determined at least in part by the local variation in autoinhibition. Thus, we provide direct, real-time observations of the functional consequence of tonic and phasic DAergic signaling in vivo.

Keywords: evoked dopamine release, basal dopamine, D2 receptor, autoinhibition, diffusion, in vivo voltammetry

INTRODUCTION

Central dopamine (DA) neurons exhibit a broad functional diversity that underlies their role in numerous pathologies, including substance abuse (Phillips et al. 2003), schizophrenia (Abi-Dargham et al. 2000), and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Salahpour et al. 2008). The mechanisms responsible for DA’s diversity of function and dysfunction are a matter of longstanding interest. The anatomical compartmentalization into the nigrostriatal and mesolimbic DA systems is well known (Carli et al. 1985; Carr and White 1986; Horvitz 2000). Furthermore, DA systems operate on multiple time scales to selectively encode function. Rapid DA signaling encodes reward and learning whereas slower DA signaling appears more relevant to motor function (Schultz 2007). Rapid signaling involves sub-second DA transients produced by the burst firing of midbrain DA neurons in response to salient stimuli (Schultz 1998). Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) has produced a wealth of information on the role of such transients in reward and learning (Wightman and Robinson 2002). Slow DA signaling derives from DA release associated with the tonic activity of DA neurons (Grace 1991; Benoit-Marand et al. 2001; Venton et al. 2003) and release via the dopamine transporter (DAT) (Lonart and Zigmond 1991; Falkenburger et al. 2001; Borland and Michael 2004). However, tonic DA levels are more challenging to detect with FSCV, a differential measurement technique best suited to monitoring short-term DA fluctuations (Heien et al. 2005). At present the literature does not contain direct FSCV observations of extracellular DA engaged in both rapid and slow signaling.

In our hands, (Kulagina et al. 2001; Borland and Michael 2004; Mitala et al. 2008) FSCV shows that the striatal extracellular space contains a tonic DA concentration under basal conditions sufficient to activate presynaptic D2 autoreceptors (Grigoriadis and Seeman 1985). This leads to the expectation that DA terminals should be tonically autoinhibited. However, this expectation conflicts with multiple reports that D2 receptor antagonists have little or no effect on DA release evoked by very brief electrical stimuli (1-to-4 pulses) of DA neurons (Garris et al. 1994; Garris and Wightman 1995; Benoit-Marand et al. 2001). Such observations support the opposite conclusion that DA terminals are not autoinhibited prior to the onset of evoked release, i.e. under the basal condition.

The present study resolves this issue by reconsidering the source of the long-known heterogeneity of evoked DA release in the striatum (May and Wightman 1989a; b; Peters and Michael 2000). This heterogeneity has been attributed to variations in the density of terminals near the recording site, i.e. that some recording sites are close to DA terminals whereas others are not. Consequently, it has become common practice to optimize the position of recording electrodes to sites with a high density of terminals (Garris et al. 1993). The practice of optimizing the recording location, combined with other technological refinements of FSCV, has produced detailed knowledge of both evoked and naturally occurring sub-second DA transients, fostering seminal insights into their physiological and functional significance (Robinson et al. 2001; Phillips et al. 2003; Roitman et al. 2004; Stuber et al. 2005). On the other hand, almost no attention has been paid to non-optimized recording sites where evoked responses exhibit comparatively low amplitudes and slow dynamics.

The literature suggests that the non-optimized recording sites are those with few or no DA terminals, such as the “non-DA” sites revealed by immunohistochemistry (Venton et al. 2003). The non-optimized responses have been attributed to diffusional distortion arising because the recording electrode is remote from DA terminals (i.e. the electrode missed its intended target) (May and Wightman 1989b; Garris et al. 1994; Peters and Michael 2000). However, we now provide two lines of evidence showing that non-optimized responses are instead a consequence of autoinhibition. First, the responses have features that cannot be explained by diffusion. Second, the D2 drugs, raclopride and quinpirole, affect the responses in a manner consistent with the functions of presynaptic D2 autoreceptors (Usiello et al. 2000; Benoit-Marand et al. 2001; Rougé-Pont et al. 2002). We conclude that the heterogeneity of evoked DA release in the striatum derives, at least in part, from spatial variations in autoinhibition. The heterogeneity of autoinhibition explains the coexistence of reports that DA terminals both are (this study) and are not (this study; Garris et al. 1994; Garris and Wightman 1995; Benoit-Marand et al. 2001) autoinhibited under basal conditions. Furthermore, we provide direct observations of DA engaged simultaneously in rapid and slow signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Carbon Fiber Electrodes

Single 7-µm diameter carbon fibers (T650, Cytec Carbon Fibers LLC., Piedmont, SC) were placed inside borosilicate glass capillaries (0.4 mm ID, 0.6 mm OD, A–M systems Inc., Sequim, WA). The capillaries were pulled to a fine tip with a vertical micropipette puller (Narishige, Los Angeles, CA) and backfilled with low-viscosity epoxy (Spurr Epoxy, Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA). The exposed fiber was cut to a length of 400 µm and sonicated in reagent grade isopropyl alcohol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) containing activated carbon (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) for 30 minutes (Bath et al. 2000). A droplet of mercury in the barrel established electrical contact between the fiber and a nichrome contact wire (Goodfellow, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, UK).

Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry

FSCV was conducted with an EI 400 high-speed potentiostat (originally constructed by Ensman Instruments but presently available from ESA Inc., Chelmsford, MA) and the program “CV Tar Heels v4.3” (courtesy of Dr. Michael Heien, Department of Chemistry, Pennsylvania State University). The resting potential was 0 V vs Ag/AgCl and the voltammetric waveform consisted of three linear potential sweeps to +1 V, −0.5 V, and back to 0 V at a sweep rate of 400 V/s. The scans were performed at 10 Hz. The DA oxidation current was recorded between 0.5 and 0.7 V during the first sweep. DA voltammograms were obtained by background subtraction.

Electrode Calibration

Electrodes were pre- and post-calibrated in a flow cell with gravity fed artificial cerebral spinal fluid solution (1.2mM Ca2+, 152mM Cl−, 2.7mM K+, 1.0mM Mg2+, 145mM Na+, pH 7.4). Electrodes with rapid DA response times were identified by pre-calibration: electrodes exceeded 85% of their steady-state DA signal in less than 300 ms, i.e. by the third measurement after a step change in DA concentration. Conversion of in vivo oxidation currents to DA concentrations was based on post-calibration results. Standards for calibration were prepared with as-received dopamine HCl (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–350g) (Hilltop, Scottsdale, PA) were anesthetized with isoflurane (2% by vol.) and placed in a stereotax (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) with the incisor bar raised 5 mm above the interaural line (Pellegrino et al. 1979). A heating blanket (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) maintained body temperature at 37°C. A twisted, bipolar, stainless steel stimulating electrode was placed over the medial forebrain bundle (from bregma: 1.6 mm lateral, 2.2 mm posterior, 8.0 mm below dura). A carbon fiber microelectrode was placed in the ipsilateral striatum (from bregma: 2.5 mm lateral, 2.5 mm anterior, initially 4.5 mm below dura). The final depth of the stimulating electrode was determined by lowering until DA release was evoked in the striatum: this well-established protocol assures stimulation of ascending DAergic fibers (Ewing et al. 1983; Kuhr et al. 1984; Heien et al. 2005).

Electrical Stimulation

The stimulus was an optically isolated, constant-current, biphasic waveform (frequency 60 Hz, pulse height 270 µA, pulse width 2 ms). Several stimulus protocols were used: single trains between 0.2 s and 5 s long, four 1-s trains separated by 2- or 4-s intervals, and four 200-ms trains separated by 1.8-s intervals. Stimuli were performed 5 min before and 30 min after drug administration.

Drugs

Raclopride tartrate (2 mg/kg i.p.) and (−)quinpirole hydrochloride (1 mg/kg i.p) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were dissolved in phosphate buffered saline (100 mM phosphate, pH 7.4).

Modeling

Evoked DA responses were simulated with Wightman’s mathematical model (Wightman et al. 1988):

| (1) |

where [DA]ex represents the extracellular DA concentration, f is the stimulus frequency, [DA]p is the concentration of DA released-per-stimulus pulse, Vmax is the maximum rate of DA uptake, and KM is the DAT Michaelis constant. The effects of diffusion on [DA]ex were examined by convoluting the output of Equation 1 with Fick’s second law of diffusion. The convolution was implemented by a finite element algorithm in Excel. We have described the use of finite element algorithms in several previous papers (Lu et al. 1998; Yang et al. 1998), so the details are omitted here. Finite element algorithms for solving diffusion equations are well known (Bard and Faulkner 2001).

Data Analysis

During multi-train stimuli, the voltammetric signal occasionally did not return to baseline during the interval between trains. In these cases, voltammetric signals were re-zeroed at the start of each stimulus train. Pre- and post-drug response amplitudes during consecutive stimulus trains were analyzed by means of two-way ANOVA.

RESULTS

Heterogeneity of evoked dopamine release

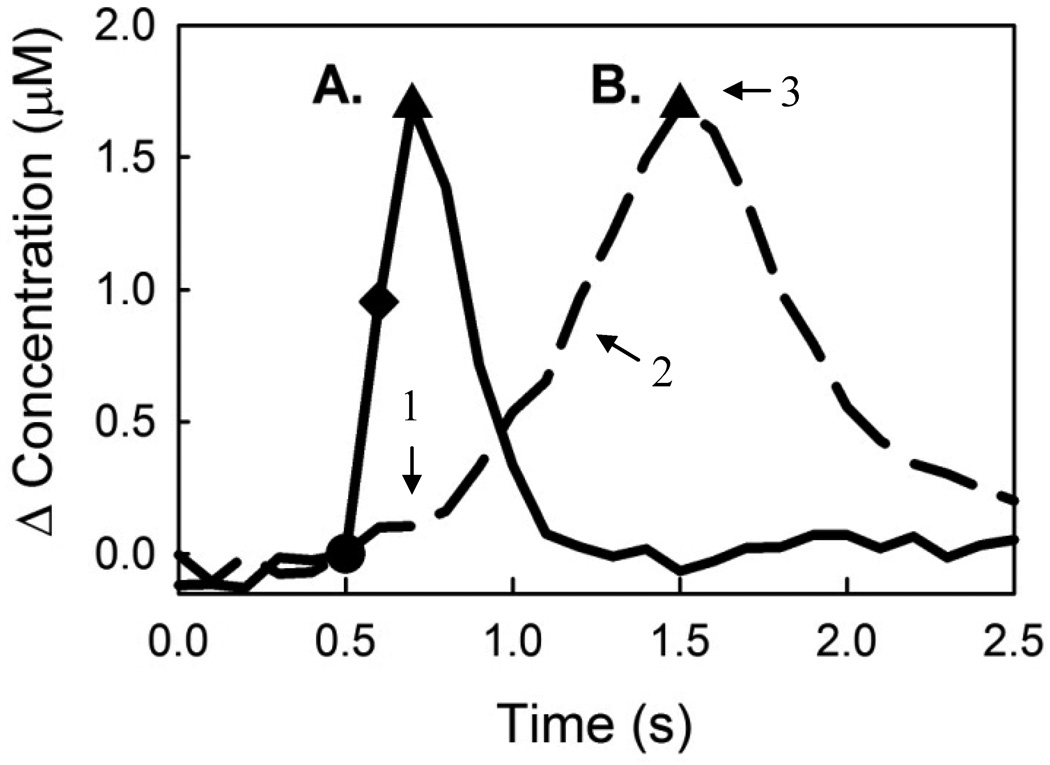

As previously reported (May and Wightman 1989a; b), electrical stimulation of DAergic fibers in the medial forebrain bundle evokes heterogeneous DA release in the striatum. The two stimulus responses in Fig 1 were recorded using identical voltammetric procedures in different rats. The stimulus durations were 200 ms (12 pulses) and 1 s (60 pulses) in Figs 1A and 1B, respectively. The amplitudes of evoked DA release are similar (~1.7 µM) despite the 5-fold difference in stimulus duration. In Fig 1A the response is rapid at first and decreases as the stimulus proceeds: note that the DA concentration after 200 ms of stimulation is less than double that after 100 ms (diamond). In Fig 1B the response rate is initially slow (arrow 1) and increases as the stimulus continues (arrow 2). Both responses begin to fall without delay when the stimulus ends.

Figure 1.

Kinetic heterogeneity of evoked DA release in the rat striatum. The symbols mark the start (circles) and finish (triangles) of the stimuli. The evoked change in extracellular DA was recorded by FSCV with 400-µm long carbon fiber microelectrodes. (A) A fast-type response: DA increases rapidly during the stimulus and falls rapidly after the stimulus. The amount of DA evoked after the first 6 stimulus pulses (diamond) is more than half of the amount of DA evoked after 12 pulses (triangle), indicating that the rate of DA release is decelerating. (B) A slow-type response: evoked DA release begins slowly (arrow 1) and accelerates as the stimulus continues (arrow 2). At the end of stimulation the signal returns toward baseline immediately (arrow 3), showing no signs of overshoot.

In the past, responses with a slow initial rate that increases over time (Fig 1B) were thought to derive from a diffusional distortion arising when the electrode was not positioned close enough to DA terminals. However, we now show that diffusional distortion does not explain several attributes of these responses. For example, if diffusion delays the onset of the response at the start of the stimulus, it should also delay the fall of the response when the stimulus ends (see also Fig 7, below). The delay at the end of the stimulus is expected because DA must diffuse back to DA terminals in order to bind the DAT and be cleared from the extracellular space. Previously (Kawagoe et al. 1992), the delay at the end of the stimulus was described as a signal “overshoot.” Responses without overshoot (Fig 1B, arrow 3) are inconsistent with diffusional distortion.

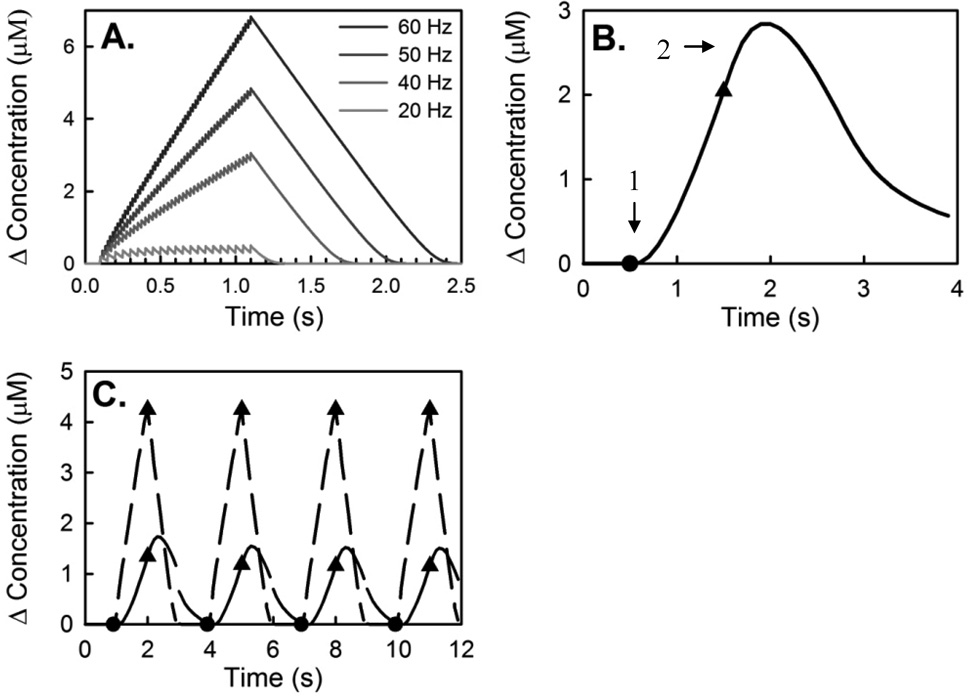

Figure 7.

(A) Theoretical evoked DA curves using the Wightman model (Vmax = 6 mM/s, KM = 200 nM, [DA]P = 200 nM). The modeled curve rises without delay at all stimulus frequencies. (B) The effects of a 15 µm diffusion gap on the Wightman model curve (60 Hz). Diffusion causes an initial delay in the DA signal (arrow 1), and an overshoot of signal after the end of stimulation (arrow 2). (C) Modeling 1-s trains, 2-s interval stimulations. The Wightman model predicts four equal evoked curves (dashed lines). Diffusion of four identical evoked curves produces four signals with similar delays and amplitudes.

Classification of response profiles

For the sake of clarity, we classify responses as “fast-type” when the rate is initially rapid and decreases with ongoing stimulation (Fig 1A) and “slow-type” when the rate is initially slow and increases with ongoing stimulation (Fig 1B). Although fast and slow responses differ in amplitude, our classification is not based on the amplitude. This classification is objective because it is easy to distinguish responses that increase or decrease in rate during the stimulus.

Hybrid evoked responses

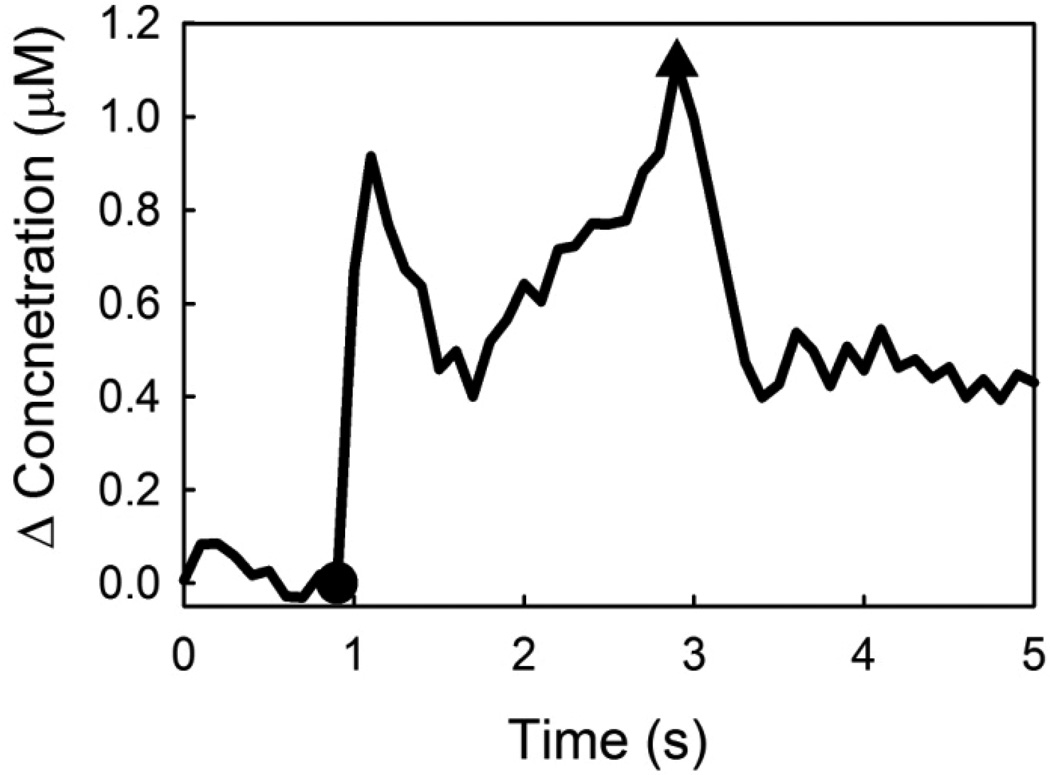

Heterogeneous responses occur within individual animals (Fig 2). The example in Fig 2, which we classify as a hybrid response, exhibits an initial rapid rise in DA that ends, in this case, after 200 ms. The response falls briefly and then increases for a second time but at a slower rate. Hybrid responses reveal the simultaneous detection of fast-type and slow-type behaviors during a single recording. Hence, they confirm that instrumental factors, such as the temporal response or sensitivity of the electrode, are not the source of the response heterogeneity.

Figure 2.

A carbon fiber electrode location exhibiting both fast-type and slow-type release. This hybrid-type response has two peaks. The slope of the ascending part of the first peak is steeper than the second peak counterpart. The rapid rise of the first peak demonstrates a fast-type response, while the second peak has a slow-type response.

In order to record hybrid responses, it was necessary to optimize the placement of the recording electrode. Even with optimization, we were unable to locate hybrid responses in all animals even when slow responses were recorded. Thus, sites yielding hybrid responses are relatively rare compared to those that yield only slow responses. The response in Fig 1A was from a site exhibiting a hybrid response: the stimulus was shortened to 200 ms (12 pulses) to isolate the fast component.

Evoked dopamine release during multiple stimulus trains

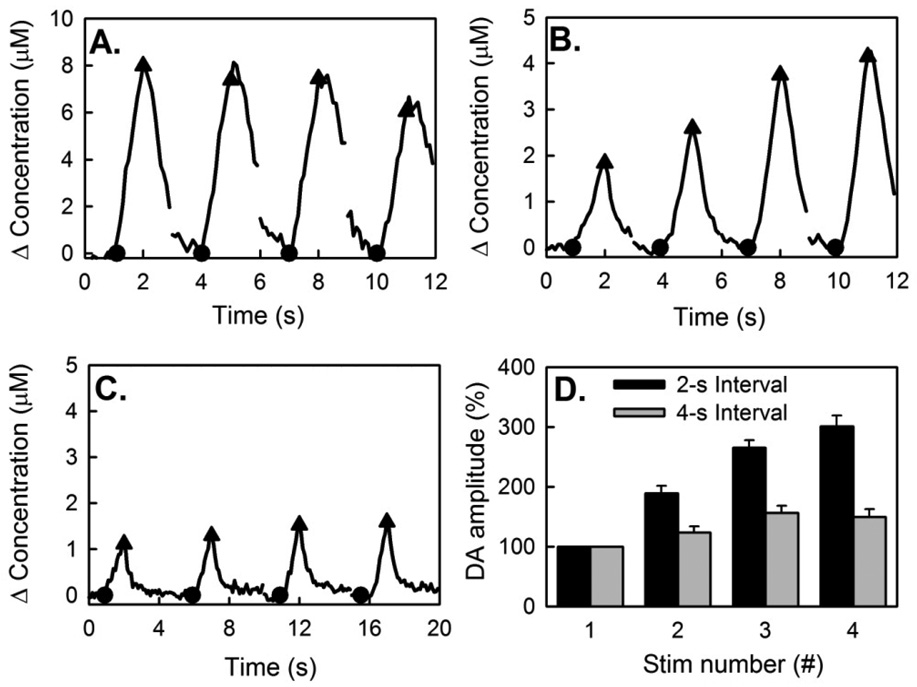

We characterized fast, slow, and hybrid responses using multiple stimulus trains (Fig 3–Fig 6). In the figures, circles and triangles mark the beginning and end, respectively, of each stimulus train. For clarity, we re-zeroed the response at the beginning of each train. Most experiments involved 1-s stimulus trains separated by 2-s intervals.

Figure 3.

DA recordings by FSCV during consecutive stimulus trains. (A) Fast-type response during 1-s trains at 2-s intervals. (B) Slow-type response during 1-s trains at 2-s intervals. (C) Slow-type response during 1-s trains at 4-s intervals. (D) Comparison of the normalized amplitudes of the slow-type responses at 2-s and 4-s intervals: the difference between the 2-s and 4-s groups is significant (ANOVA; F(1,96) = 61.6; n=13; p<0.00001).

Figure 6.

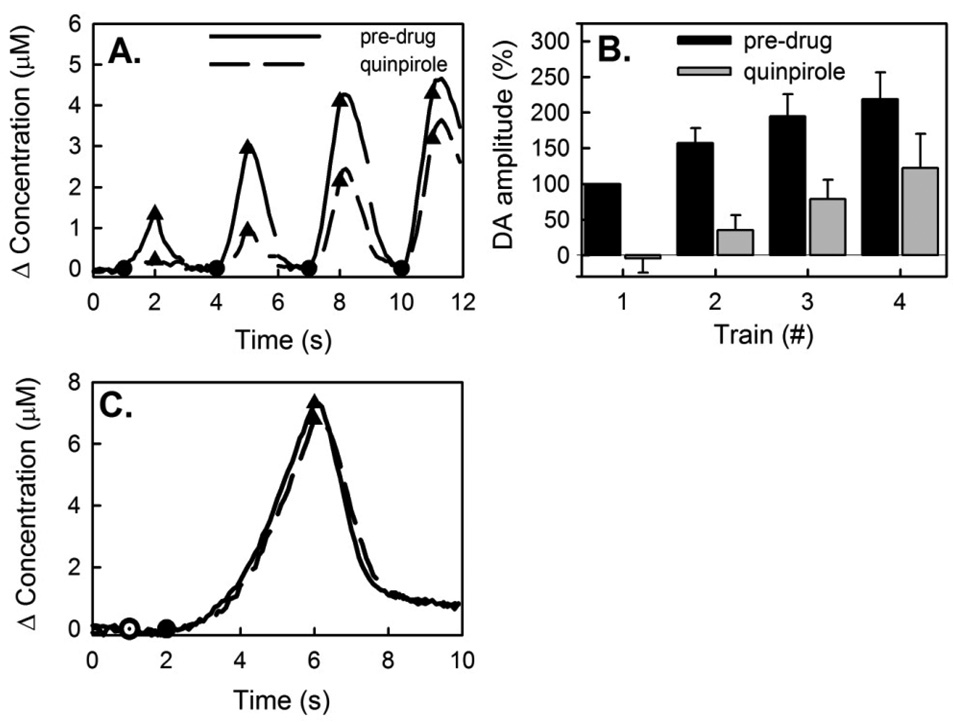

Quinpirole delays evoked DA release. (A) Quinpirole decreased the response amplitudes during 1-s trains at 2-s intervals. However, quinpirole did not prevent the acceleration of evoked DA release. (B) The effect of quinpirole on the normalized response amplitudes is significant (ANOVA; F(1,32) = 29.1; n=5; p<0.0001). Quinpirole did not remove the significant difference between the response amplitudes to consecutive trains (ANOVA; F(3,32) = 6.8; n=5; p<0.002). (C) The duration of pre- and post-drug stimulus responses were adjusted in order to evoke similar response amplitudes, thus the start of stimulation pre-drug (closed circle) and quinpirole (open circle) were staggered. Quinpirole delayed the onset of evoked release but thereafter did not alter the kinetics of evoked DA release or the kinetics of DA clearance after the stimulus.

When the first train evoked a fast-type response (Fig 3A), subsequent trains evoked descending response amplitudes, showing that the decrease in the response rate persists across the interval between trains. This slow-down phenomenon has been reported before and is attributed to an exhaustion effect and/or autoinhibition resulting from the evoked increase in extracellular DA. When the first train evoked a slow-type response (Fig 3B), the response rate increased during each train and subsequent trains evoked ascending amplitudes. Hence, the increase in rate persisted across the 2-s interval between trains. This persistence was almost absent when the trains were separated by 4-s intervals (Fig 3C). Figs 3B and 3C are representative examples: Fig 3D summarizes normalized slow-type responses from 13 animals. The difference in response amplitudes with 2-s and 4-s intervals is significant (ANOVA; F(1,96) = 61.6; n=13; p<0.00001).

It was not necessary to optimize the position of the recording electrode to locate slow-type responses: in our hands, the slow-type response is prevalent in the rat striatum. The persistence in the increased response rate during the intervals between the stimulus trains cannot be attributed to diffusional distortion, further speaking against diffusional distortion as the source of slow-type responses (see also Fig 7).

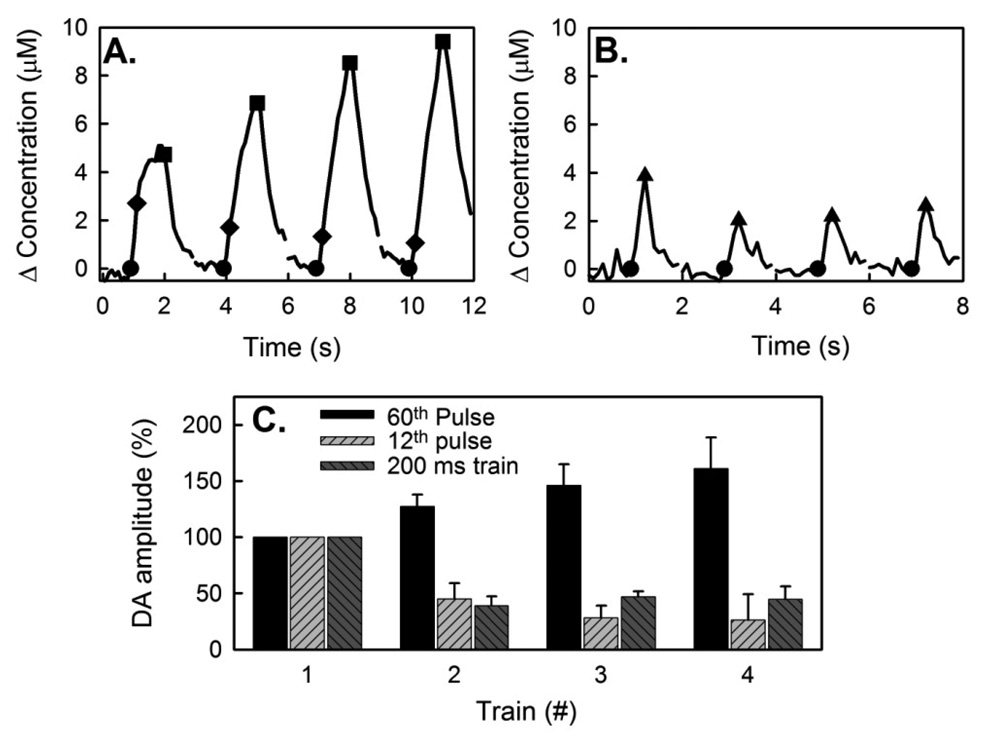

In most cases, hybrid responses comprised a fast signal component that appeared as a leading shoulder on a subsequent slow response (Fig 4). The leading shoulder was most apparent during the first stimulus train. We quantified the fast signal component with the amplitude measured after 12 stimulus pulses (Fig 4A, black diamonds). The fast signal component decreased in amplitude during subsequent trains, consistent with the behavior of fast-type responses described above (Fig 3A). Trains of 12-pulses (200-ms trains separated by 1.8-s intervals) also produced descending response amplitudes (Fig 4B). Figure 4C shows averaged response amplitudes (n=3 animals) after 12 and 60 pulses of the 1-s trains and after the 200-ms trains. The main group effect is significant (ANOVA; F(2,24) = 44.6; n=3; p<0.00001). However, a Tukey post-hoc test reveals that the responses after12 pulses and the 200-ms trains are not different, so the fast and slow responses are significantly different from each other.

Figure 4.

Kinetic hybrid responses during consecutive stimulus trains. (A) During 1-s trains at 2-s intervals the fast-type signal component appears as a leading shoulder on the response. The signal recorded after 12 stimulus pulses (diamonds) was used to quantify the amplitude of the fast signal component. The signal recorded after 60 pulses (squares) was used to quantify the slow component. (B) DA during 200-ms (12-pulse) trains at 1.8-s intervals: these short trains isolate the fast signal component. (C) Normalized response amplitudes: according to ANOVA the group effect is significant (ANOVA; F(2,24) = 44.6; n=3; p<0.00001); according to the Tukey post-hoc test, there is no difference between the responses after 12 pulses during 1-s trains and the responses evoked by 200-ms trains.

The role of the D2 receptor

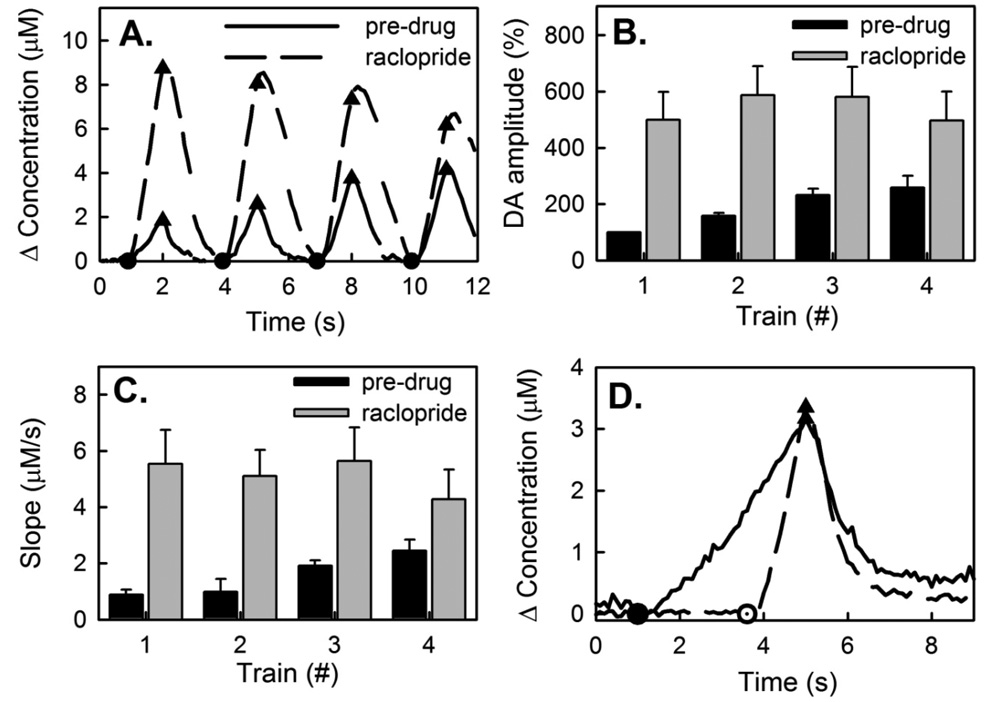

Raclopride (2 mg/kg i.p) converts slow responses to fast responses (Fig 5). In the example of Fig 5A, the pre-raclopride response (1-s trains separated by 2-s intervals) is slow-type while the post-raclopride response (same electrode, recording locations, etc.) is fast-type. Raclopride eliminated the initial period of slow release and abolished the increase in response amplitude during subsequent trains (n=5, Fig 5B).

Figure 5.

(A) Raclopride (2 mg/kg i.p.) converts slow-type responses (pre-drug, solid line) to fast-type responses (post-drug, dashed line). (B) The effect of raclopride is significant (ANOVA; F(1,32) = 52.86; p<0.00001). Pre-drug there was a significant difference between the responses to the consecutive trains, but raclopride abolished this difference (ANOVA; F(3,32) = 0.88; n=5; p>0.5). (C) The effect of raclopride on the initial rise of the DA signal is also significant (ANOVA; F(1,32) = 21.9; n=5; p<0.0001). Raclopride removed the delay present in the pre-drug signal, causing DA signals that increased immediately upon stimulation. (D) The duration of pre- and post-drug stimuli were adjusted to produce a similar maximal amplitude. Then the responses were aligned at the end of the stimulus to permit a comparison of the clearance kinetics. Raclopride had no consistent effect on DA clearance, suggesting that the effects of raclopride noted in this figure are due to changes in the velocity of evoked DA release.

In the case of slow-type responses, raclopride increased the amplitude of the DA measurement from the very beginning of the first stimulus train, i.e. after 12 stimulus pulses. Pre-raclopride, slow DA release was often not detectable after the first 12 stimulus pulses. Hence, the effect of raclopride is not dependent upon the evoked release of DA. To quantify this effect, we measured the slope of the responses between 100 and 300 ms (6–18 pulses) after the start of each stimulus train (Fig 5C). Raclopride consistently and significantly increased the initial response rate (ANOVA; F(1,32) = 21.9; n=5; p<0.0001). This carries two important meanings. First, it shows that the slow responses are a consequence of autoinhibition that exists prior to the onset of the stimulus, i.e. due to a preexisting tone of DA on D2 receptors, presumably derived from basal DA. Second, it shows that the electrode was positioned near DA terminals during these measurements as there was no delay in the onset of the post-raclopride signal. This second point further confirms that diffusional distortion is not the source of the slow responses.

Raclopride affects both DA release and clearance (Greco et al. 2006). So, we wished to establish whether the effects of raclopride observed here are due to changes in DA release or DA clearance. For this purpose, we adjusted the stimulus duration to establish similar evoked amplitudes pre- and post-raclopride and then aligned the responses at the end-point of the stimuli (Fig 5D). This procedure revealed no consistent effect of raclopride on DA clearance, suggesting the effects reported here are derived from alterations in evoked release.

The D2R agonist, quinpirole (1 mg/kg i.p.), consistently and significantly extended the initial period of slow evoked release (Fig 6): evoked release was not detected during the first stimulus train (Fig 6A). This unequivocally confirms that activation of D2 receptors can delay the onset of the evoked response. Subsequent stimulus trains produced ascending response amplitudes, but the amplitudes were significantly lower than before quinpirole (Fig 6B; ANOVA; F(1,32) = 29.1; n=5; p<0.0001). Again, we adjusted the stimulus durations to match the pre- and post-quinpirole amplitudes and aligned the responses at their end-points (Fig 6C). Quinpirole had no systematic effect on DA clearance. Aligning the responses in this way showed that quinpirole increased the delay in onset of evoked release but did not alter the time course of the subsequent response.

Insights from Wightman’s simple model of evoked release

In this study, we have relied on the concept that the slow-type responses are inconsistent with diffusional distortion. This requires some explanation. The simple form of Wightman’s model of evoked release i.e. equation 1 with constant parameters ([DA]p, Vmax, and KM), often fits well with optimized in vivo responses (Wu et al. 2001) but is incapable of reproducing the features of the slow responses described here (Fig 1B). The simple model only produces responses with decreasing rates (Fig 7A: these are example responses simulated with literature standard parameter values). The decrease in rate has a clear origin: the release term, f * [DA]p, is a constant value but the uptake term, , increases with [DA]ex. Thus, the response rate (the difference between release and uptake terms, Equation 1) is obliged to decrease as the stimulus proceeds.

The effect of diffusion on the modeled responses can be examined by convolution (Fig 7B). In the example of Fig 7B, a simple response is convolved with diffusion over a distance of 15 µm using the DA diffusion coefficient measured in the rat striatum (Nicholson and Rice 1991). The convolution causes a slow initial response that speeds up over time (arrow 1). Qualitatively, there is a good match between the convolution output and rising phase of slow-type in vivo responses (e.g. Fig 1B). However, the convolution produces a clear overshoot (arrow 2), which is absent from our in vivo recordings.

During this study, we made no attempt to fit the convoluted simulations to our in vivo results because we do not agree that diffusion causes the slow-type responses. In past work, convolution was employed to account for the effects of diffusion through Nafion layers (Kawagoe et al. 1992), which were not used in the present work.

Diffusion does not explain the persistence of the increase in response rate during the intervals between trains. In the example of Fig 7C, the simple model was used to simulate a response to four 1-s trains separated by 2-s intervals with and without convolution: according to the models, the consecutive trains produce similar responses, which does not match our in vivo observations.

DISCUSSION

Our findings support the conclusion that slow-type responses derive from striatal sites at which evoked DA release is autoinhibited by basal (non-evoked) extracellular DA. The autoinhibition is tonic, rather than phasic, because it was present before the onset of electrical stimulation. This is consistent with our reports of tonic DA in the striatal extracellular space at concentrations sufficient to activate DA autoreceptors (Kulagina et al. 2001; Borland and Michael 2004; Mitala et al. 2008). Our study includes real-time recordings of DA functioning on multiple time scales determined, at least in part, by the local autoinhibitory tone.

Diffusion or complex release kinetics?

May and Wightman (May and Wightman 1989a; b) originally described evoked responses with initially slow rates that increase over time, as we have also observed (Fig 1B). May and Wightman speculated that this might be due to an increase in the rate of evoked release, but attributed it instead to diffusional distortion arising because the recording electrode was not close enough to DA terminals (May and Wightman 1989b). Diffusional distortion could arise if the electrode were surrounded by a zone of dead tissue (Benoit-Marand et al. 2007), although electron microscopy shows that the dead zone around carbon fibers is likely too small to create significant distortion (Peters et al. 2004). However, several features of the slow responses speak against diffusional distortion. The responses lack the expected overshoots at the end of the stimulus trains (Fig 1B and Fig 7B), which shows that the electrode is close to DAT and, therefore, DA terminals. Diffusion does not explain the persistence of the increased rate of evoked release across the intervals between trains (compare Fig 3B with Fig 7C). And, the initial slow phase of release was abolished by raclopride (Fig 5) and extended by quinpirole (Fig 6), which confirms the role of D2Rs in slow type evoked release.

Other methodological considerations

Immunohistochemistry confirms the presence of non-DA sites within DA terminal fields (Venton et al. 2003). However, our 400-µm long electrodes are much larger than the non-DA sites (less than 10 µm). So, it is not possible that our measurements were confined to non-DA sites. Reports of signal overshoots were based on measurements with beveled microdisk electrodes (May and Wightman 1989b; Young and Michael 1993; Garris et al. 1994; Garris and Wightman 1995), so it is possible that in some cases these very small electrodes were confined to non-DA sites. However, Peters and Michael (2000) compared the heterogeneity of evoked responses at microdisk and microcylinder electrodes and observed responses without overshoots with recording electrodes of both geometries. Hence, the absence of overshoots is not due just to the use of long electrodes. Furthermore, the initially slow DA responses cannot be attributed to the temporal response of the electrodes or recording system, as the responses accelerated with repeated stimulus trains and with the administration of raclopride. Moreover, the hybrid responses confirm that FSCV is capable of recording fast and slow dynamics. On the same grounds, the slow responses cannot be attributed to the placement of the stimulating electrode or choice of stimulus parameters.

The role of autoreceptors

The slow type responses are a consequence of autoinhibition derived from basal DA. It is important to emphasize that the D2R drugs did not simply alter the magnitude of the slow responses but also their time course. The post-raclopride evoked response appeared earlier than the pre-raclopride, i.e. raclopride eliminated the delay in the onset of the evoked response at the beginning of the stimulus (Fig 5). This is an important observation because it demonstrates that autoinhibition was active prior to the beginning of the stimulus. Quinpirole extended the delay in the onset of the response (Fig 6), unequivocally confirming the ability of D2 receptors to delay the onset. These pharmacological effects provide clear support for the conclusion that the slow responses derive from autoinhibition that occurs independently of the DA released by the stimulus, i.e. autoinhibition by basal DA.

The origin of pre-stimulus autoinhibition

Recently, using FSCV, we showed that the striatal extracellular space contains a tonic DA concentration (Kulagina et al. 2001; Borland and Michael 2004; Mitala et al. 2008) sufficient to activate D2R autoreceptors (Grigoriadis and Seeman 1985). The micromolar-range basal DA concentrations we found exceed the low-nanomolar levels widely reported by microdialysis. However, the combined effects of tissue damage and DA uptake cause microdialysis to underestimate actual in vivo DA concentrations, even when no-net-flux or extrapolation to zero-flow procedures are used (Clapp-Lilly et al. 1999; Peters et al. 2000; Bungay et al. 2003; Borland et al. 2005; Mitala et al. 2008). We conclude that the tonic extracellular DA concentration is the source of the autoinhibition that causes the slow responses. With this conclusion in mind, non-optimized striatal recording sites that exhibit slow responses may be reinterpreted as sites where tonic DA signaling leads to autoinhibition of phasic DA release.

Slow type responses are prevalent in the striatum

With 400-µm long electrodes, slow responses are routinely observed in the striatum. Since many responses are exclusively of the slow type, we conclude that slow sites have a domain size commensurate with the length of the electrodes. Hybrid responses are comparatively rare: we had to search for such sites and failed to find hybrid responses in all but a few animals. These observations portray the slow sites as prevalent within the striatum compared to the fast sites. The prevalence of slow sites suggests that the majority of DA terminals in the striatum are tonically autoinhibited. This phenomenon has been overlooked to date due to the attribution of slow responses to non-DA sites and the consequent decision to optimize the recording locations in many voltammetric studies. It now appears that optimizing the recording site amounts to searching for non-inhibited DA terminals.

A comment on stimulus-induced acceleration of evoked DA release

While autoinhibition provides a clear explanation for the slow initial rate of evoked release, our study was not specifically designed to explain why the rate of evoked release increases with continued stimulation. Stimulus-induced acceleration of neurotransmitter release is an interesting and known phenomenon (Greengard et al. 1993; Montague et al. 2004; Kita et al. 2007) but in the present study was observed during supra-physiological stimulation. The stimulation frequency was 60 Hz whereas DA neurons burst near 20 Hz and tonically fire at 1–2 Hz (Grace and Bunney 1984; Benoit-Marand et al. 2001; Hyland et al. 2002). A supra-physiological stimulus was necessary to force evoked release in the face of autoinhibition. Thus, the details of the release evoked by 60 Hz stimuli are not likely to be of direct physiological relevance. Since the autoinhibition we describe here is derived from endogenous (i.e. non-evoked) DA release, we presume that the autoinhibition has physiological relevance.

The necessity of supra-physiological stimulation to observe the slow responses further explains why little attention has been paid to non-optimized recording sites. There has been tremendous interest in investigating DA release during more physiologically relevant stimulus parameters (e.g. Montague et al. 2004). However, the slow sites do not yield a detectable response to such stimuli.

A comparison of fast and slow responses

The new phenomenon exposed by this study is that many, if not most, sites in the dorsal striatum exhibit slow DA behaviors due to tonic autoinhibition by basal DA. The slow sites exhibit a number of properties that are readily distinguished from the fast sites. For example, the fast responses agree well with Wightman’s simple model (Wu et al. 2001),whereas the slow responses clearly do not (Figure 7). Moreover, the impact of D2Rs on fast-type evoked DA release has been thoroughly characterized by other laboratories (Limberger et al. 1991; Kennedy et al. 1992; Benoit-Marand et al. 2001; Phillips et al. 2002; Avshalumov and Rice 2003; Kita et al. 2007). A main conclusion of those prior studies is that autoinhibition of fast responses begins only after the stimulus itself delivers DA to the extracellular space, i.e. that autoinhibition derived from basal DA is weak or absent. This stands in contrast to the effect of autoinhibition on slow responses.

Although differences in the fast and slow responses are evident, as just summarized, a fundamental similarity also exists. Montague et al. (2004) and Kita et al. (2007) clearly demonstrated that autoreceptors play an important role in the facilitation and depression of fast-type evoked release. Our study shows that is also true for slow release, which seems to be as expected since the striatum receives a single, presumably homogenous, DAergic midbrain projection. The literature, for example, does not point to substantial differences between subpopulations of DA terminals. Thus, the heterogeneity of evoked release appears related to heterogeneity of the presynaptic input to DA terminals, rather than a fundamental difference between the terminals themselves.

Wightman’s simple model agrees with fast responses, but it does not capture all the details of facilitation and depression. Montague et al. (2004) developed a more sophisticated model and used it to explore the kinetics of facilitation and depression (Montague et al. 2004; Kita et al. 2007). We have not yet applied a Montague-style model to our results. Nevertheless, it is possible to highlight some interesting and potentially significant differences between the facilitation and depression of fast and slow responses.

For example, Kita et al. did not report subpopulations of DA sites exhibiting different behaviors akin to the hybrid sites we report. This is because Kita et al. optimized the recording location, so their study focuses on fast sites (e.g. sites that produce robust responses to 12-pulse stimuli). Both studies found that raclopride enhances the response amplitude during the first stimulus train. However, Kita et al. noticed depression after raclopride (Kita’s Fig 4a) while we did not (Fig 5). This might be a sign that fast sites are more sensitive to an autoreceptor-independent long-term depression than the slow sites. Kita et al. attribute long-term depression to slow refilling of the releasable pool. It seems logical that this form of depression would be more apparent at sites where the stimulus more rapidly depletes the releasable pool.

At fast sites, quinpirole modestly affects the responses to the first stimulus train and does not affect the responses to the subsequent 4 trains (Kita et al.’s Fig 5a). The authors attribute this to the ability of quinpirole to promote desensitization of autoreceptors upon evoked DA release. In contrast, at slow sites, quinpirole diminished the responses to all four trains in our study (Figure 6A and B). It is worth mentioning that, in total, Kita used far fewer stimulus pulses than we did (120 versus 240), so it is not the case that our stimulus was too short to permit the pre- and post-drug responses to converge. Furthermore, our results are not so consistent with a desensitization mechanism, as there was no detectable evoked DA release during the first post-quinpirole stimulus train. In that case, it is unlikely that the first stimulus train desensitized autoreceptors. As mentioned above, however, our study did not investigate the mechanism of facilitation due to the supra-physiological nature of the stimulus.

Overall, the pharmacological results, especially in the case of quinpirole, suggest that autoreceptors have greater impact on slow release, which is consistent with the idea that the distinction between fast and slow sites is related to heterogeneity in the presynaptic input to DA terminals. Although the source of such heterogeneity remains to be explored, obvious possibilities present themselves, including spatial heterogeneity in the basal extracellular DA concentration, spatial heterogeneity in the sensitivity or expression of autoreceptors, and/or spatial heterogeneity in other transmitter substances that modulate DAergic activity.

A potentially significant implication of our study is that the slow component of the DA system might play a larger physiological role than previously understood. For example, DAergic drugs might have differential effects in fast and slow sites, as indicated in a preliminary way in the case of raclopride and quinpirole. Further investigation of the slow DA component might provide insights into some of the well known, but as yet unresolved, DA paradoxes, such as the use of psychostimulants as a therapy for hyperactivity disorders.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant #MH075989.

Abbreviations

- DA

dopamine

- D2R

D2-receptor

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- FSCV

fast scan cyclic voltammetry

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest.

Bibliography

- Abi-Dargham A, Rodenhiser J, Printz D, et al. Increases baseline occupancy of D2 receptors by dopamine in schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:8104–8109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avshalumov MV, Rice ME. Activation of ATP-sensitive K+(KATP) channels by H2O2 underlies glutamate-dependent inhibition of striatal dopamine release. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:11729–11734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834314100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard AJ, Faulkner LR. Electrochemical methods, fundamentals and applications. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bath BD, Michael DJ, Trafton BJ, Joseph JD, Runnels PL, Wightman RM. Subsecond adsorption and desorption of dopamine at carbon-fiber microelectrodes. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:5994–6002. doi: 10.1021/ac000849y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit-Marand M, Borrelli E, Gonon F. Inhibition of dopamine release via presynaptic D2 receptors: time course and functional characteristics in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:9134–9141. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09134.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit-Marand M, Suaud-Chagny M-F, Gonon F. Presynaptic regulation of extracellular dopamine as studied by continuous amperometry in anesthetized animals. In: Michael AC, Borland LM, editors. Electrochemical Methods for Neuroscience. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2007. pp. 35–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland LM, Michael AC. Voltammetric study of the control of striatal dopamine release by glutamate. J. Neurochem. 2004;91:220–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland LM, Shi G, Yang H, Michael AC. Voltammetric study of extracellular dopamine near microdialysis probes acutely implanted in the striatum of the anesthetized rat. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2005;146:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bungay PM, Newton-Vinson P, Isele W, Garris PA, Justice JB. Microdialysis of dopamine interpreted with quantitative model incorporating probe implantation trauma. J. Neurochem. 2003;86:932–946. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01904.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carli M, Evenden JL, Robbins TW. Depletion of unilateral striatal dopamine impairs initiation of contralateral actions and not sensory attention. Nature. 1985;313:679–682. doi: 10.1038/313679a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr GD, White NM. Anatomical dissociation of amphetamine's rewarding and aversive effects: an intracranial microinjection study. Psycholpharmacology, Berl. 1986;89:340–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00174372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp-Lilly KL, Roberts RC, Duffy LK, Irons KP, Hu Y, Drew KL. An ultrastructural analysis of tissue surrounding a microdialysis probe. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1999;90:129–142. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(99)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing AG, Bigelow JC, Wightman RM. Direct in vivo monitoring of dopamine released from two striatal compartments in the rat. Science. 1983;221:169–171. doi: 10.1126/science.6857277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenburger BH, Barstow KL, Mintz IM. Dendrodendritic inhibition through reversal of dopamine transport. Science. 2001;293:2465–2470. doi: 10.1126/science.1060645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garris PA, Collins LB, Jones SR, Wightman RM. Evoked extracellular dopamine in vivo in the medial prefrontal cortex. J. Neurochem. 1993;61:637–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb02168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garris PA, Ciolkowski EL, Pastore P, Wightman RM. Efflux of dopamine from the synaptic cleft in the nucleus accumbens of the rat brain. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:6084–6093. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-10-06084.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garris PA, Wightman RM. Regional differences in dopamine release, uptake, and diffusion measured by fast-scan cyclic voltammetry. In: Boulton A, Baker G, Adams RN, editors. Neuromethods: voltammertic methods in brain systems. Vol. 27. Totowa: Humana; 1995. pp. 179–220. [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA, Bunney BS. The control of firing pattern in nigral dopamine neurons: single spike firing. J. Neurosci. 1984;4:2866–2876. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-11-02866.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA. Phasic versus tonic dopamine release and the modulation of dopamine system responsivity : a hypothesis for the etiology of schizophrenia. Neuroscience. 1991;41:1–24. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90196-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco PG, Meisel RL, Heidenreich BA, Garris PA. Voltammetric measurement of electrically evoked dopamine levels in the striatum of the anesthetized Syrian hamster. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2006;152:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greengard P, Valtorta F, Czernik AJ, Benfenati F. Synaptic vesicle phosphoproteins and regulation of synaptic function. Science. 1993;259:780–785. doi: 10.1126/science.8430330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriadis D, Seeman P. Complete conversion of brain D2 dopamine receptors from the high- to the low-affinity state for dopamine agonists, using sodium ions and guanine nucleotide. J. Neurochem. 1985;44:1925–1935. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb07189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heien MLAV, Khan AS, Ariansen JL, Cheer JF, Phillips PEM, Wassum KM, Wightman RM. Real-time measurement of dopamine fluctuations after cocaine in the brain of behaving rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:10023–10028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504657102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz JC. Mesolimbocortical and nigrostriatal dopamine responses to salient non-reward events. Neuroscience. 2000;96:651–656. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland BI, Reynolds JNJ, Hay J, Perk CG, Miller R. Firing modes of midbrain dopamine cells in the freely moving rat. Neuroscience. 2002;114:475–492. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawagoe KT, Garris PA, Wiedemann DJ, Wightman RM. Regulation of transient dopamine concentration gradients in the microenvironment surrounding nerve terminals in the rat striatum. Neuroscience. 1992;51:55–64. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90470-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy RT, Jones SR, Wightman RM. Dynamic Observation of Doparnine Autoreceptor Effects in Rat Striatal Slices. J. Neurochem. 1992;59:449–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita JM, Parker LE, Phillips PEM, Garris PA, Wightman RM. Paradoxical modulation of short-term facilitation of dopamine release by dopamine autoreceptors. J. Neurochem. 2007;102:1115–1125. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhr WG, Ewing AG, Caudill WL, Wightman RM. Monitoring the stimulated release of dopamine with in vivo voltammetry. I: characterization of the response observed in the caudate nucleus of the rat. J. Neurochem. 1984;43:560–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulagina NV, Zigmond MJ, Michael AC. Glutamate regulates the spontaneous and evoked release of dopamine in the rat striatum. Neuroscience. 2001;102:121–128. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00480-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limberger N, Trou SJ, Kruk ZL, Starke K. "Real time" measurement of endogenous dopamine release during short trains of pulses in slices of rat neostriatum and nucleus accumbens: role of autoinhibition. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1991;344:623–629. doi: 10.1007/BF00174745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonart G, Zigmond MJ. High glutamate concentration evoke Ca(++)-independent dopamine release from striatal slices: a possible role of reverse dopamine transport. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;256:1132–1138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Peters JL, Michael AC. Direct comparison of the response of voltammetry and microdialysis to electrically evoked release of striatal dopamine. J. Neurochem. 1998;70:584–593. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70020584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May LJ, Wightman RM. Effects of D-2 antagonists on frequency-dependent stimulated dopamine overflow in nucleus accumbens and caudate-putamen. J. Neurochem. 1989a;53:898–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb11789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May LJ, Wightman RM. Heterogeneity of stimulated dopamine overflow within rat striatum as observed with in vivo voltammetry. Brain Res. 1989b;487:311–320. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90835-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitala CM, Wang Y, Borland LM, Jung M, Shand S, Watkins S, Weber SG, Michael AC. Impact of microdialysis probes on vasculature and dopamine in the rat striatum: A combined fluorescence and voltammetric study. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2008;174:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR, McClure SM, Baldwin PR, Phillips PEM, Budygin EA, Stuber GD, Kilpatrick MR, Wightman RM. Dynamic gain control of dopamine delivery in freely moving animals. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:1754–1759. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4279-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson C, Rice ME. Diffusion of ions and transmitters in the brain cell microenvironment. In: Fuxe K, Agnati LF, editors. Volume Transmission in the Brain. New York: Raven Press; 1991. pp. 279–294. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino LJ, Pellegrino AS, Cushman AJ. A stereotaxic atlas of the rat brain. Plenum Press: New York; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Peters JL, Michael AC. Changes in the kinetics of dopamine release and uptake have differential effects on the spatial distribution of extracellular dopamine concentration in rat striatum. J. Neurochem. 2000;74:1563–1573. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JL, Yang H, Michael AC. Quantitative aspects of brain microdialysis. Anal. Chem. Acta. 2000;412:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Peters JL, Miner LH, Michael AC, Sesack SR. Ultrastructure at carbon fiber microelectrode implantation sites after acute voltammetric measurements in the striatum of anesthetized rats. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2004;137:9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips PEM, Hancock PJ, Stamford JA. Time Window of Autoreceptor-Mediated Inhibition of Limbic and Striatal Dopamine Release. Synapse. 2002;44:15–22. doi: 10.1002/syn.10049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips PEM, Stuber GD, Heien MLAV, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. Subsecond dopamine release promotes cocaine seeking. Nature. 2003;422:614–618. doi: 10.1038/nature01476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DL, Phillips PEM, Budygin EA, Trafton BJ, Garris PA, Wightman RM. Sub-second changes in accumbal dopamine during sexual behavior in male rats. Neuroreport. 2001;12:2549–2552. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200108080-00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roitman MF, Stuber GD, Phillips PEM, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. Dopamine operates as a subsecond modulator of food seeking. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:1265–1271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3823-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougé-Pont F, Usiello A, Benoit-Marand M, Gonon F, Piazza PV, Borrelli E. Changes in extracellular dopamine induced by morphine and cocaine: crucial control by D2 receptors. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:3293–3301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03293.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salahpour A, Ramsey AJ, Medvedev IO, et al. Increase amphetamine-induced hyperactivity and reward in mice overexpressing the dopamine transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:4405–4410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707646105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1–27. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Multiple dopamine functions at different time courses. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;30:259–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuber GD, Roitman MF, Phillips PEM, Carelli RM, Wightman RM. Rapid dopamine signaling in the nucleus accumbens during contingent and noncontingent cocaine administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:853–863. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usiello A, Baik J-H, Rougé-Pont F, Picetti R, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Piazza PV, Borrelli E. Distinct functions of the two isoforms of dopamine D2 receptors. Nature. 2000;408:199–203. doi: 10.1038/35041572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venton BJ, Zhang H, Garris PA, Phillips PE, Sulzer D, Wightman RM. Real-time decoding of dopamine concentration changes in the caudate-putamen during tonic and phasic firing. J. Neurochem. 2003;87:1284–1295. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman RM, Amatore C, Engstrom RC, Hale PD, Kristensen EW, Kuhr WG, May LJ. Real-time characterization of dopamine overflow and uptake in the rat striatum. Neuroscience. 1988;25:513–523. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90255-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman RM, Robinson DL. Transient changes in mesolimbic dopamine and their association with 'reward'. J. Neurochem. 2002;82:721–735. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Reith MEA, Wightman RM, Kawagoe KT, Garris PA. Determination of release and uptake parameters from electrically evoked dopamine dynamics measured by real-time voltammetry. Neuroscience Methods. 2001;112:119–133. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Peters JL, Michael AC. Coupled effects of mass transfer and uptake kinetics on in vivo microdialysis of dopamine. J. Neurochem. 1998;71:684–692. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71020684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SD, Michael AC. Voltammetry of extracellular dopamine in rat striatum during ICSS-like electrical stimulation of the medial forebrain bundle. Brain Res. 1993;600:305–307. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91387-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]