Abstract

This article provides an overview of the social history leading up to the crack era, especially 1960 to the present. The central theme holds that several major macro social forces (e.g., economic decline, job loss, ghettoization, housing abandonment, homelessness) have disproportionately impacted on the inner-city economy. These forces have created micro consequences that have impacted directly on many inner-city residents and have increased levels of distress experienced by households, families, and individuals. Economic marginality has generated high levels of alcohol and other drug abuse as well as criminality, which are exemplified in this article by one inner-city household having an extensive family history exhibiting the chronic impacts of these macro forces and their micro consequences.

Keywords: crack cocaine, inner-city household-family, macro social forces, micro social consequences

This article examines the social history of the inner city from 1960 to 1992 in an effort to understand the social forces that provided support for the rapid and widespread adoption of crack cocaine after 1983–1984. The central argument is that several major macro social forces have disproportionately impacted on the inner-city economy and have increased levels of social distress. These forces have impacted directly on many inner-city residents and have increased levels of social distress experienced by households, families, and individuals, which in turn has generated alcohol and other drug abuse as well as criminality. The micro consequences are exemplified by one inner-city household (headed by Island and Ross) having an extensive family history paralleling these macro forces.

In addition, this article focuses on the continued socioeconomic decline in the inner city during the period 1960–1992, particularly in New York City. This 32-year period was chosen because virtually all evidence shows important declines in living standards among inner-city residents during that period (Jaynes & Williams 1989). New York City is a primary focus because its inner-city residents account for a disproportionate share of the nation's problem (Karsada 1992), and historically the city has had the nation's largest drug abuse problem. Additionally, most of the authors' prior research among inner-city drug abusers has been conducted in New York.

An important subtheme in this article is that the use, abuse, and sale or distribution of illegal drugs — especially heroin, cocaine, and crack — are both a consequence of the rising social distress in the inner city and an important contributor to the continuity and intensity of inner-city conditions, and the difficulty in alleviating them. Furthermore, all indicators currently suggest that social distress in the inner city is increasing, intensifying, and perhaps accelerating. Johnson and colleagues (1990) provided a more extended overview of the social history of crack abuse and macro level forces. The case history of Island and her household is more extensively documented in Dunlap (In press-a).

The American economy has historically been characterized by unequal resource allocation, particularly for minorities. While great racial and ethnic disparities existed in the early 1960s, Blacks who migrated from the South to northern cities, migrants from Puerto Rico to New York, and Hispanics to southwestern cities and Chicago made substantial gains economically. During the past three decades, however, American culture and the international economy shifted in emphasis from manufacturing to service sectors. This trend decreased the need for unskilled labor and increased the requirements for advanced education and technical skills. This transformation has generated several major crises, reallocated resources away from programs and services provided in the 1960s, and created numerous difficult conditions for those living in inner-city America.

Several eras of drug use, abuse, and sales have occurred in America since 1965 (Johnson & Manwar 1991) and dramatically transformed patterns of criminal behavior and social arrangements in inner cities. Numerous laws and efforts at controlling drug abusers have been politically popular but have had very repressive impacts on inner-city persons and households. Alcohol, heroin, cocaine, and, recently, crack abuse and distribution, combined with declining socioeconomic conditions, have severely disrupted many inner-city households and families across three and four generations. Such household-families with drug-abusing members serve as the primary vector in transmission across generations of drug abuse, drug sales and distribution, criminal behavior, and support for deviant behaviors.

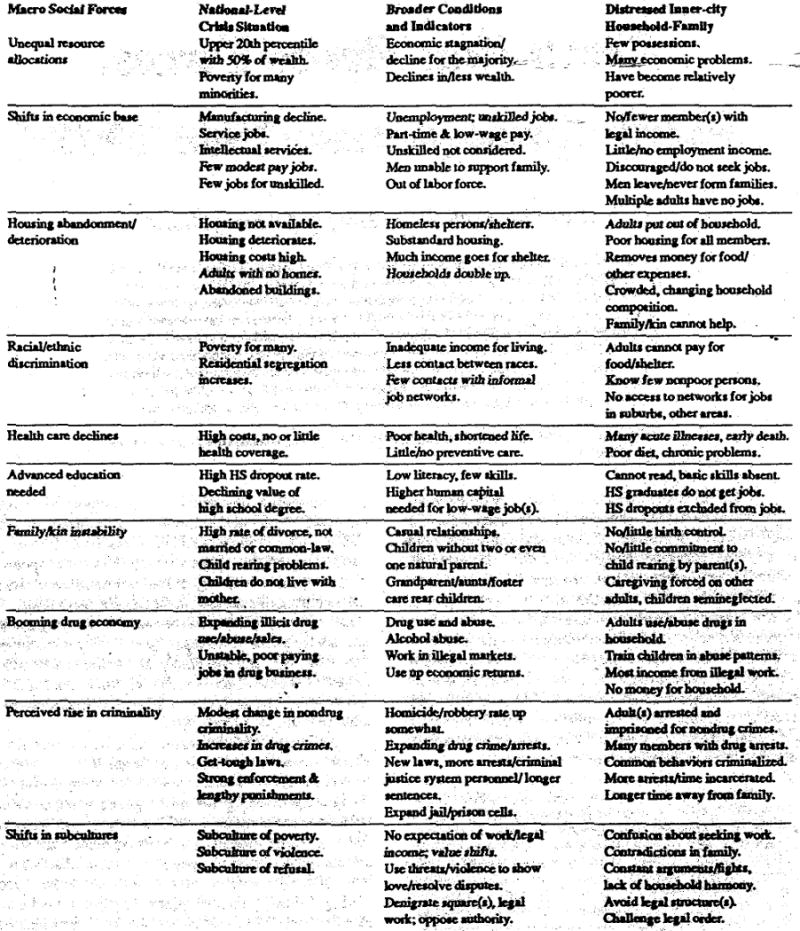

Figure 1 summarizes key themes to be developed below. Macro social forces (e.g., shifting economic base, housing deterioration, drug economy expansion) have created nationwide crisis situations for those with low incomes, especially those living in American inner cities. In turn, such crises in the inner city have generated conditions of social distress that tend to be chronic and cumulative over years across generations. In sociological terms, crisis is a turning point, often brought about by a convergence of events that create new circumstances requiring new responses. The term “crisis” may be applied in a wide range of contexts, from macro to micro levels (Dunlap In press-a; Lyman 1975). Conditions are relatively objective circumstances that are measurable and can be used to document social distress across many persons.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of Social Distress and Distressed Inner-City Households.

These socioeconomic forces and conditions are intertwined in complex ways. They have their immediate and concrete impacts on households, families, and individuals. A key focus of this article is on what may be called the severely distressed inner-city household-family — those living in the inner cities of major urban centers in America, especially New York City. In Kasarda's (1992) study of the 95 most populated central cities in 1980, 15% of the most severely distressed Black households and 55% of the most severely distressed Hispanic households were in New York. Very similar problems and social distress (Kasarda 1992) are likely to emerge among poor households and families in many other parts of America outside of the inner cities (Jaynes & Williams 1989; Dembo 1988).

Many inner-city households and families manage to maintain continuity and relative stability for several years, and may not be classified as severely distressed. However, the focus here is on households that would meet (or exceed) all five distress criteria used by Kasarda (1992): low education (high-school dropout), single parenthood (household head with children under age 18), poor work history (worked less than half time in prior year), receipt of public assistance, and householder's family income from legal sources below the poverty line.

The present analysis focuses on the household-family because the usual census assumptions about family composition and household structure and processes are infrequently met among distressed inner-city households. Rather, the household-family has emerged as an adaptation that meets the survival needs of several persons in the kin network. The availability of a household is the determining factor. Many inner-city adults have great difficulty in acquiring and maintaining a place of residence. While a household head is usually present, the family composition of the household varies dramatically day by day (Dunlap In press-a, 1992) in response to conditions set in force by social and economic macro forces. Several blood relatives and fictive kin who are essentially homeless (and drug abusers) may claim a given household as their home. They may not usually live there, but may keep some clothes there and return periodically to wash and change their attire. They may also reside in the household for short periods of time.

One may speculate — noting that inadequate documentation currently exists — that a majority of these severely distressed inner-city household-families in 1992 probably have one or more adults (16 and older) who is a drug abuser, or drug seller, or who is criminally active. Such drug abusers and sellers may be present or absent from the household-family at any given time, but their appearances provide economic benefits as well as economic and social harms to household-family units. Moreover, drug abusers and sellers in such households act as role models, mentors, and employers (both positive and negative) for youths growing up — thus transmitting values, beliefs, and practices reflecting subcultures of drug abuse, drug sales, criminality, and violence (Dunlap In press-a, 1992). Indeed, such drug abusers and sellers routinely engage in behaviors that disrupt household harmony and stability.

The dynamic shifts and the intensity of problems in such severely depressed inner-city household-families confront researchers with formidable analytic problems and policymakers with complex issues to resolve. If policy could substantially alter the family interaction patterns among such severely depressed inner-city household-family units, policymakers could substantially reduce the magnitude of social distress, dramatically reduce drug abuse and sales, and greatly reduce other fundamental social problems in America. The continuing failure to address these problems — now well documented since the 1960s — is likely to lead to continuing expansion in generational transmission of drug abuse, continuing crises and social conditions, and continuing problems for society in the future.

An Overview of Macro Social Forces, Crises, and Conditions 1960-1992

This section provides an overview of the broad socioeconomic forces and crises during the past 32 years, with special attention to contributions of drug abuse.

Before 1960

Before, during, and after World War II, thousands of Blacks left the South because few jobs were available, and higher paying jobs could be found in northern cities (even if pay was low relative to Whites employment). In the 1940s and 1950s, thousands of Puerto Ricans and individuals from the West Indies also migrated to New York. These immigrants settled in Harlem, East Harlem, the Lower East Side, and Brooklyn. Such immigrants and their families were severely impoverished in both the South and North. Nevertheless, expansion of the national economy decreased the proportion of Blacks living in poverty from 85% in 1944 to 55% in 1959 (Jaynes & Williams 1989). Like many postwar American families, these immigrants had children and contributed disproportionately to the baby-boom generation (born between 1946 and 1960). These minorities gained housing as thousands of White city dwellers moved to the mushrooming suburbs (Frey 1980).

The civil rights movement in the 1950s focused national attention on legal and civil inequalities and on the poverty and despair of Blacks and other minorities. Although (relative to Whites) housing discrimination, low incomes, and other problems beset minorities before 1960, most migrants were considerably better off economically in the cities than their relatives who had remained in the South or than their parents had been two decades earlier. A case study (see Dunlap In press-a, 1992) of one such household is interwoven with the following analysis to illustrate the interplay between the macro social forces and the micro consequences.

A Severely Distressed Inner-city Household-Family: Island, Ross, Sonya

In 1990, Island and her household-family lived in a three-bedroom apartment in Central Harlem. Island is 60 years old and lives with her son, Ross (a 35-year-old active crack seller) and daughter, Sonya (a 37-year-old crack prostitute), as well as several other household members who circulate in and out. Island's story attests to the harsh reality confronting many inner-city families, and reflects the impact of larger social forces and conditions, especially the impact of alcohol and other drug abuse, and the drug economy on a severely distressed household across several years and generations. Despite its problems, it exemplifies the “least unstable households” (Dunlap 1992) affected by drug abuse.

1930 to 1947

In 1930, Island was born on a Caribbean Island and abandoned at birth by her natural mother; her father died when she was four. In 1935, Island was brought to New York, and raised by a stepmother as the youngest of six children. Their household was “doubled up” with the stepmother's sister and her five children. Island's childhood memories were of her stepmother working long hours as a domestic. From 1935 to 1948 Island lived in Harlem with her family and kin network. She therefore grew up in Harlem although her family were migrants. In twelfth grade, she dropped out of school to care for her stepmother who was very ill.

1948 to 1959

In 1947, Island met Joe who was about 25 years old and recently released from jail. He had come from South Carolina and found low-wage work as a coal deliverer. After they married in 1948, Island worked as a home attendant on and off until her first child, Sonya, was born in 1953; Ross was born in 1955. Island found her husband was a heavy alcohol abuser. In 1959 Island left her husband to protect herself and her children after Joe raped their six-year-old daughter. Two years later, her husband was hit by a car and killed.

The 1960s

The 1960s saw major changes in northern urban centers and the lives of minorities in those cities. The civil rights movement had its peak influence as the voting rights act and other legislation and federal enforcement efforts guaranteed the legal rights and equality of opportunity for Blacks and other minorities. The War on Poverty, launched in 1964,1 promised better incomes and living standards for all the poor, but especially for Blacks. Several major books document the situation during this era.

In several volumes titled Children of Crisis, Robert Coles (1970, 1968) provided careful psychological case studies of the response to various crisis situations among persons living in poverty in a period of civil rights demonstrations, including sharecroppers and migrants from south to north. Oscar Lewis (1965) advanced the thesis of a culture of poverty (which he claimed is a subculture). The strengths and other characteristics of Black families were described by several authors (Hill 1971; Billingsley 1968). Wolfgang and Ferricutti (1967) described a subculture of violence and Cohen (1955) described a subculture of delinquency. Heroin abuse began to become a major issue (Brown 1965; Malcolm X & Haley 1965; Chein et al. 1964).

Relative to what was to transpire in the 1980s, these sources and many others document important elements of stability in the social and economic life of inner-city dwellers in the first half of the 1960s. Most inner-city families had one or more adults with some legal employment; Black men were almost as likely to be employed as White men, although at a lower wage rate (Jaynes & Williams 1989). Inner-city families could usually afford housing with about 30% of their income. If they doubled up with relatives, it was generally for less than a year. Almost no family or kin member was homeless or without a place to sleep. Minority couples either were married or maintained a common-law relationship for several years. Children in single-parent households were usually raised by their mothers, sometimes with a father or father substitute present. Occasionally children would be sent to a grandmother or female relative, but be returned to their mother. Grandmothers were seldom responsible for raising their grandchildren. While alcohol use and abuse were common, the use of illicit drugs (especially marijuana, heroin, cocaine) was rare. While there were common-law crimes (robbery, burglary, theft among men and theft or prostitution among women) among some low-income persons, the sale and distribution of illegal drugs was virtually unknown. Even among prostitutes, much income was expended to support their children and household.

In the last half of the 1960s, however, three major events sharply shifted national attention and resources away from poverty and civil rights. First, the Vietnam War (1965–1973) diverted public attention and many fiscal resources from antipoverty programs. Student and antiwar protests spread across American campuses and society; police riots against students generated further protests.

Second, civil disorders and riots in Black inner cities expressed Black rage and anger about the slow pace of economic progress (Grier & Cobbs 1963). These riots badly damaged the fragile infrastructure of Black inner-city communities, particularly in Newark, Detroit, and Los Angeles. The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (1968:1-2) warned that America was headed toward “two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal” and documented the rise of a Black ghetto “largely maintained by white institutions and condoned by white society” (see also Clark 1965).

Third, this decade marked the introduction of illicit drugs as a major recreational activity for millions of individuals of the baby-boom generation who were entering adolescence. Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics, from all class levels participated in this phenomenon. Three Major “drug eras” (Johnson & Manwar 1991) began and overlapped. The marijuana era (1965–1979) began in 1965 when approximately 5% of college students in New York and California began using marijuana; the proportions of marijuana users and frequency of use increased steadily through the 1960s and 1970s. The psychedelic era (1967–1975) saw substantial but smaller increases in the use of LSD — such use occurred primarily among Whites from middle-class backgrounds; inner-city youths generally avoided psychedelics (Johnson 1973). The heroin era (1965–1973), however, occurred primarily among inner-city youths, especially in New York City (and somewhat later in other cities) (Hunt & Chambers 1976).

Despite these increases in social distress, the postwar economic boom continued relatively unabated and Blacks across the nation gained somewhat economically. In 1969, Black men were only 5% less likely than Whites to be employed, and they earned 62% as much as Whites (up from 53% in 1959). The proportion of Blacks in poverty dropped from over 50% to 30% during the 1960s, compared with a drop of 18% to 9% among Whites (Jaynes & Williams 1989). Poverty rates dropped from 51% in 1959 to 20% among Black families headed by men. Poverty rates among Black families headed by women increased from 70% in 1959 to 75% in 1964 but declined to about 60% in 1969 (Jaynes & Williams 1989). Island, her household, and kin network were impacted by alcoholism; they were one of many inner-city households bypassed by economic improvements and afflicted with the pressing problems of a severely distressed family.

1960 to 1969

Island left her husband and began to raise her children alone while supported by welfare. She soon became the caregiver for her kin network. All of Island's older siblings were alcoholics. Their offspring were taken to Island's house until the siblings could resume parental duties. For example, when Island's sister was imprisoned for killing a young woman while performing an abortion, Island took in her children until their mother returned from prison. While raising Ross and Sonya, Island also raised several nieces and nephews when parental acts resulted in jail or prison, or when alcohol consumption limited their ability to care for their children.

The 1970s and 1980s

The economic expansion and dramatic economic gains for Blacks came to an abrupt halt in the early 1970s (Jaynes & Williams 1989). Shifting social forces created a crisis, which impinged directly on inner-city household-families. Each of these larger structural forces has been magnified by the rise of the drug economy and drug abuse among household members.

Shifting Economic Base

Following the end of the Vietnam War in the early 1970s, the American and international economic base shifted substantially. The primary shift has been the decline of manufacturing jobs in the United States that rely on unskilled or semiskilled labor, offering a steady low-to-modest wage and creating goods for the consumer mass market. Foreign countries with lower wage rates and modern equipment now produce many consumer goods (e.g., automobiles, appliances, clothing) that were dominated by American manufacturers in the 1950s and 1960s. Many manufacturing plants located in central cities and employing thousands of inner-city minorities were closed in the 1970s and 1980s (Sullivan 1989). In New York City, over half a million manufacturing jobs plus 100,000 jobs in wholesale and retail trades were lost between 1967 and 1987 (Kasarda 1992). Most such jobs had been filled by blue-collar workers, many of whom faced unemployment or had to accept lower wage jobs. While many fast-food-type jobs were added during these two decades, these usually pay minimum wage or only slightly more; neither individuals nor families can afford housing with such low incomes.

A major shift rarely noted in the American economy was the explosive growth in the underground economy, especially the drug economy in the inner city. Many employed and unemployed persons (Ross and Sonya among them) were attracted by and had much better earnings from this illegal activity than were offered by minimum wage jobs or legal positions, a theme developed below.

Declining Labor Force Participation

By all measures of economic change, inner-city minority residents were literally left behind. For inner-city minority youths and for many adults, virtually no legal jobs were available in their communities or among their networks of associates (Sullivan 1989). Especially among out-of-school males ages 16 to 24, the percent not working (both unemployed and out of labor force) increased from 19% in 1968-1970 to 44% in 1986-1988 among central city residents in Boston, Newark, New York, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh. The proportion of high-school dropouts ages 16 to 64 not working was over 50% among Black males in midwestern cities, including Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, Milwaukee, and St. Louis (Kasarda 1992).

While unemployment has increased, nonparticipation in the labor force (not seeking work and not working) has also grown substantially. During a 45-year work career (from ages 20 to 65), Black men in 1970 could anticipate 36 years of work, two years unemployment, and eight years out of the labor force. In the following 15 years, both unemployment and nonparticipation grew substantially for Black men (but not Whites). By 1985, Black men were likely to work only 29 years, be unemployed for five years, and spend 11 years out of the labor force (Jaynes & Williams 1989).

Between 1972 and 1982 the number of unemployed Black persons increased by 1.3 million (140%, 900,000 in 1972 to 2.1 million in 1982). The unemployment rates for both Blacks and Whites in 1982 were the highest since World War II, but the Black unemployment rate was still double that of Whites. In 1982 the unemployment rate among Black teenagers reached 48%, 28 percentage points higher than that for White teenagers (20.4%).

Island had no legal job outside her house since the early 1950s, although she earned occasional money babysitting for neighbors. Her primary occupation was caregiver for her children and those of her siblings; Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) payments kept her household below the poverty line. In the early 1970s, Ross made a tentative entry into the legal labor force. He obtained a part-time job paying the minimum wage, but held it for only a year before losing it. He has not had a legal job since, nor has he sought legal employment; he has been out of the labor force for 15 years. Similar short job histories, followed by dropping out of the labor market, are common among Island's kin network. Only one distantly related nephew (whom Island did not help raise) has “gone good” by entering and having a career in the armed forces.

Although the mid-1980s were a time of economic expansion across the nation, few or no benefits “trickled down” to inner-city residents. Among high-school dropout minority males ages 16 to 64 living in inner-city neighborhoods in 1990, approximately half to three-quarters (depending on the city) lacked legal employment and many of these have not worked at all during the prior decade.

Advanced Education Needed for New Jobs

The American economy, however, has expanded considerably in the suburbs and in some southern and western cities. The major growth in the 1980s has occurred in service-sector jobs. The best jobs in the computer industry and financial services demand college and advanced degrees or special skills that can only be learned on the job. A quarter million such jobs were added to the New York City economy between 1977 and 1987, and a quarter million more were added in New York suburbs (Kasarda 1992). Yet the odds of a Black student entering college within a year of graduating from high school were less than one-half the odds for a White student. During the booming 1980s, however, out-of-school males 16 to 64 years of age who did not have a college degree and lived in major midwest and northeast cities experienced increasing rates of not working (both Blacks and Whites, center city and suburban residents). Especially in inner-city neighborhoods, high-school dropout rates approach 50% or higher and a high-school diploma from such schools was generally undervalued by employers (Jaynes & Williams 1989; Reed 1988). The vast majority of drug abusers are high-school dropouts, although high-school graduates are increasingly common as the value of education has declined. But during the 1970s and 1980s, school systems have kept most minorities in school so that declining proportions have not completed eighth grade.

Sonya left high school in the eleventh grade as a result of her heroin addiction. At age 16, Ross dropped out of high school to sell drugs, primarily PCP. Island did not encourage or support the children in her care to do homework and she ignored their poor attendance and grades. None did well or enjoyed school; they saw no point in completing it. Virtually all children raised by Island dropped out of high school, and none has entered, or seriously considered attending college. Advanced education was not even a distant possibility in Island's household.

Housing Abandonment and High Housing Costs

By 1960, many structurally sound housing units provided low-cost housing to working families living in the inner-city. During the past 30 years, large segments of the low-cost housing stock deteriorated or were abandoned, particularly in inner-city neighborhoods (Dolbeare 1983; Hartman 1983; Hartman, Keating & Le Gates 1982). In the 1980s, real estate values in most major metropolitan areas soared, so that affordable housing was beyond the economic means of much of the population (Tucker 1989).

Affordable housing was unreachable for nearly half of the nation's Black and Hispanic families; 42% of all Black and Hispanic households spent more on housing in 1985 than is considered affordable, compared to 27% among Whites. Among poor minority households, nearly four out of five pay more for housing than the affordable amount (Hartman 1983). Thus, about 40% of poor Hispanic and Black households spent at least 70% of their income on housing in 1985, leaving little money for food and other necessities.

Poor young adults frequently doubled up with parents or relatives, became couch people (i.e., sleeping on the couch or improvised bedding provided by a relative or friend) or slept in garages, cars or other locales (Ropers 1988). Sizable proportions, particularly alcoholics and other drug abusers, were without housing and unable to obtain couches or garages to sleep in (Johnson et al. 1990). Although the proportions vary, a sizable proportion of drug abusers are homeless, and sleep in abandoned buildings, crack houses, public shelters, and the streets (Johnson et al. 1990, 1988).

In 1975, however, Island acquired her present residence, a modest three-bedroom apartment with one bathroom, a kitchen, and a living room in a renovated building in Central Harlem. Even at the height of New York's fiscal crisis in 1976. Island was fortunate to find this apartment, which was then affordable with her low income. It is in one of the best buildings on a block in which most of the buildings were abandoned or in dire need of repair by the mid-1970s. The building is kept up fairly well, the halls are generally clean, even though many people hang out in the vestibule. Elevators constantly break down in this six-story building, but Island's apartment is on the first floor. Island's willingness to double up by accommodating numerous family and kin means that it is generally over-crowded; the household composition changes daily. Except for her older brothers and sisters (over age 60 in 1990), almost none of the adult family-kin members maintain their own households for more than short periods. Island also tolerates high levels of drug abuse and violence among persons in the household, so it is a favorite place for otherwise homeless drug-abusing family members to visit.

Funds for subsidized housing for poor and middle-income families were reduced by over 90% in the 1980s (Downs 1983; Sanjek 1982). In major cities, many low-cost hotels were closed or converted to luxury housing or condominiums (Blackburn 1986; National Bureau of Economic Research 1986). Thus, abandonment or demolition of low-cost housing, higher cost of existing housing, and the near disappearance of low-cost hotels led to a continuing housing crisis for low-income persons. Many families and individuals had to double up with relatives who had housing; young adults had to live with parents during their twenties and thirties. New shelter arrangements developed among the poor; many have been displaced and are essentially homeless (Hooper & Hamberg 1984; Hartman, Keating &Le Gates 1982).

Concentration of Social Distress

The growing literature on the underclass (Kasarda 1992; Jargbwsky & Bane 1991; Jenck & Peterson 1991; Ricketts & Sawhill 1988; Hughes 1988; Wilson 1987; Glasgow 1981; Moynihan 1965; Myrdal 1962) documents clearly that social distress is increasingly concentrated in several areas of midwestern and northeastern cities. Based on comparisons between 1970 and 1980 (1990 census data not yet analyzed), studies show that (1) poor Blacks are more likely to live in census tracts that are insulated from those having any significant number of Whites (Hughes 1988), (2) the number of poverty census tracts increased (Jargowsky & Bane 1991), (3) the number of persons living in underclass areas grew by over 1.5 million between 1970 and 1980 — more than doubling (Ricketts & Sawhill 1988), and (4) two-thirds of the underclass census tracts were in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Detroit. Among the nation's 95 largest cities, New York City contains 15% of Blacks and 55% of Hispanics who are severely distressed (Kasarda 1992). While inner-city citizens have the right to vote and participate in political life, they have become increasingly isolated socially and economically from, the mainstream of American economic life. Economic forces and bureaucractic rules and practices effectively control most aspects of life for inner-city residents.

Island's block is located in Central Harlem, over two miles away from a predominantly White neighborhood, but a few blocks from Black middle-class housing. Whites are rarely observed on this block. Almost all Whites are police, teachers, social workers or other officials. Among the residents on the block, Ross and Island's household is among the more affluent; most families on the block live below the poverty line. Island, Ross, and Sonya rarely leave Harlem or meet nonpoor persons. They remain isolated from and limit contacts with Whites. Their contact with Whites is mainly through institutions of social control.

Family Composition

Important shifts also occurred in family structure, particularly among minorities. The proportion of Black children living in mother-only families increased from 30% to 51% between 1970 and 1985; almost 90% of Black children will experience poverty if they live in a household headed by a single woman under 30 (Gibbs 1988). Moreover, poor families headed by single women will likely be without adequate financial support for housing, so they must live with other relatives, in public shelters, or very deteriorated buildings (Smith 1988). Even when a household is maintained, several different family members, relatives, and unaffiliated persons may reside in it or be couch persons who contribute little to and consume much of the minimal fiscal resources provided by public transfers for the household head and children (Dunlap In press-a; Johnson et al. 1985).

A growing tend in child rearing is for neither the natural mother nor father to live with their child(ren); typically a relative (the child's grandparent or aunt) or the foster care system has primary responsibility for the care and nurturance of the child. (See Dunlap In press-a, 1992 for how drug and alcohol abuse contributes to this phenomenon.)

Island never remarried; she has maintained a sexual relationship with another woman of her age. Sonya has not had any children and is the only female in the family network who is childless. Ross married at 18 and had a son who died of crib death while Ross was in jail for selling angel dust (PCP); the marriage dissolved within two years. Ross also had three children by another woman who is raising the children. Ross occasionally buys presents for his children, and they can ask for help when they need it. Ross's children are being raised by their mother with support from AFDC, plus economic contributions from her brothers, also crack dealers. Except for a few years when he lived with his wife, Ross's primary residence has been Island's apartment. Over the years, Island has been awarded custody of several nieces and nephews (and their children), and has had substantial responsibility for raising almost 89 persons. She is unusual only in that she has not raised her own grandchildren (since Sonya had no children, and Ross's are raised by their mother).

Growth in Criminal Justice and Corrections Systems

The criminal justice system has expanded dramatically during the mid-1980s owing to convictions for drug sales (Mauer 1990; Austin & McVey 1989), primarily crack. At year end, prison populations grew from 196,007 in 1969 to 301,470 in 1979 (Cahalan & Parsons 1986), a 6% annual average increase, to 462,002 by 1984, a 10% annual average increase, to 710,054 by 1989 (Bureau of Justice Statistics 1990). The 1989 prisoner population represents a 10.1% average annual increase since 1984 or a 9% average annual increase during the 1980s. Near the end of 1991, one and a quarter million persons were behind bars (Bureau of Justice 1992a,b). The imprisonment rate has gone from one percent to about 4% of the adult population within 22 years. Much of the explosion since 1984 is directly traceable to increased length of sentence (Langan 1991), the explosion of crack abuse, and policy responses to it in the late 1980s.

From the ages of 18 to 24, Ross served jail time (but no prison terms) for various crimes, such as robbery, but mainly for drug-related arrests. Sonya robbed a store in which someone was killed and spent five years in prison in the 1970s. Both have managed to avoid incarceration in the 1980s, despite full-time involvement in crime. Ross's angel dust business was always lucrative and he was known for having large supplies of dust. During the 1980s, Ross was shot twice as a result of drug distribution. The first time, he was robbed and shot by drug abusers. The second time, he was shot while attempting to rob another dealer. Most of his heroin- and crack-abusing relatives had been (or continued to be) heroin addicts, have been in several rehabilitation institutions, or have served time in jail or prison for drugs or petty crimes. During 1990, four persons who had lived in Island's household for several days were arrested, convicted, and imprisoned for charges including drug sales, aggravated assault and robbery.

Other Forces

In addition to the factors listed above, many others can be shown to impact on inner-city households. These include declines in preventive health care, hospital closings in inner-city areas, shortened life span, and acute and chronic illnesses. Contracting AIDS can be a direct outcome of heroin injection via dirty needles. The social welfare network has been undermined as welfare grants remained below poverty levels and lost purchasing power, family and child care services have been cut, yet cases become more complex and foster care and abuse and neglect cases have surged.

Island has been a court-appointed guardian for numerous children of her siblings; many of these children were born while their mothers used heroin or crack. In mid-1990, she had four children assigned to foster care in her household. When these children or other family members are hurt or ill, she spends long hours in emergency rooms. She provides few lessons in good health care or primary prevention. Almost no one in the entire family-kin network uses condoms, despite frequent participation in high-risk sex. Most of the heroin-abusing family members (like Sonya and other prostitutes) have not been tested (and avoid testing) for AIDS. When Ross was hospitalized in 1991, the doctor told him that he has AIDS. Ross refuses to believe he has AIDS and does not follow through on health practices that would extend his life. Many other family-kin members have died before age 50 as a result of illness, accident, killings, or disease.

Inner-city Reservations with Stressful Conditions

All of these forces combine into a multiplicity of stressful conditions that are even more concentrated in inner-city communities than the current quantitative evidence documents. In many census tracts of Central and East Harlem, the South Bronx, and several areas in Brooklyn and Queens, the ghettoization process is so nearly complete that near “reservations” have been created. Residents are socially isolated and cut off from mainstream American society and economy in many ways. From the viewpoint of many minority inner-city residents living in these communities, the social distance (if not physical distance) to the White middle class is almost as great as for Native Americans on geographically isolated reservations. Such inner-city minorities, especially males, rarely see (much less converse) with a White person (most Whites with whom they may occasionally converse are social control agents, such as police, social workers, and teachers). Nor do such residents have reasons, resources or desires to leave their communities, as they are likely to face rejection, avoidance, disrespect, and orders from others while rarely gaining resources they need and feel they deserve.

Among their family members and even neighbors, many inner-city residents are unlikely to know anyone who has a legal job, much less a job paying in excess of $25,000 a year. Almost all the stores at which they shop are owned and operated by Whites and Asians who live outside the community. Few or no factories or low-wage jobs are available within walking distance. Most friends and neighbors will have effectively been out of the labor market and impoverished for several years, have survived on welfare for years, and have been unable to maintain decent housing. Their neighbors will likely have dropped out of high school Even if they completed high school or are literate or have some skills, the lack of networks with employed persons and the depressed economy mean that most will not be able to find jobs. Both men and women realize that the men cannot support families, so legal marriage may never occur among those who live together for years. Casual relationships may result in children who are reared by the mother or her relatives (and with no or meager assistance from the father). The mother's brother(s), other male family members and/or boyfriend(s) become father figures.

While females may receive AFDC grants (or relatives receive foster care funds), which support the rental of a deteriorated apartment, nonpayment of rent leads to frequent moves over the years. Households headed by someone like Island who can pay the rent regularly and maintain it have become the only stable location for several generations of family and kin who are essentially without residence. Such household-families are socially isolated and avoid so-called helping agencies except in acute emergencies. To this extensive social distress have been added drug abuse, drug sales and distribution, and dysfunctional household-family processes.

Impact of Drug Abuse and Distribution on Inner-City Residents

A variety of factors and impacts of drug abuse have been identified in prior analyses (Johnson et al. 1990, 1985) and will not be reiterated here. In the following, two primary vectors are identified as creating and maintaining the ghettoization process that has been underway in the 1970s and 1980s: the booming illicit drug economy and social processes in the household-family system (Dunlap In press-a, 1992).

The Booming Illicit Drug Economy

In many respects, the social forces and conditions leading to ghettoization set the conditions in which the illicit drug economy could grow and flourish. Especially important to its growth has been the effective exclusion of thousands of inner-city youths and young adults from legal jobs paying modest but sufficient income, such as those held by some of their parents a generation earlier. These youths generally did not remain entirely idle (although no good statistical evidence is available); some became active as criminals committing robbery, burglary, and theft.

What almost certainly occurred is that drug selling (legally defined as a crime for opiates and cocaine in 1914 and for marijuana in 1937) emerged sociologically as a new type of crime among inner-city (and middle-class) youths in the 1960s. Marijuana sales became a widespread phenomenon in the 1960s and 1970s. The illicit market exploded in economic importance during the crack era.

Before 1960, New York minorities had maintained prohibition-era practices in the form of after-hours clubs. These clubs operated when bars and liquor stores were closed, generally resold alcohol at higher prices to patrons, and had clientele who partied late at night. Frequently jazz musicians and other habitués would use the scarce and expensive heroin, cocaine, and marijuana; a few would sell it (Hamid 1992; Williams 1978; Malcolm X & Haley 1965).

Marijuana Sales

Marijuana use began to spread in 1965 in all segments of the American population. Inner-city youths began smoking it on a regular basis. An efficient but poorly documented distribution system emerged in Harlem and other inner-city locations in the late 1960s. As the proportion of youths using marijuana increased, and as the frequency and potency of the drug increased, a much more elaborate importation and distribution system emerged.2 Marijuana distribution in the 1960s and 1970s was characterized by cultivation in the West Indies (Jamaica, Granada, and Colombia), importation of boatloads and tons into New York, and an efficient marketing system (Hamid 1990).

By the mid-1970s, almost every block in New York's inner-city neighborhoods had a smoke shop, a storefront from which marijuana was sold either as the only item or as one of several commodities. The proprietor of the store was usually a minority person (frequently from the West Indies) who made handsome profits and invested in his ethnic community (Hamid In press, 1990). In addition, thousands of minority inner-city youths would buy small wholesale amounts (an ounce or pound), roll it into marijuana cigarettes, and sell it on the streets and parks for about one dollar. Since competition among street sellers was vigorous, marijuana sellers rarely made substantial profits, but could generally smoke free and earn some cash ($20 to $50/day). By the late-1970s, virtually all passersby on a New York street would be offered marijuana (and other drugs); nonusers could not enter Union Square, Bryant Park or Washington Square (or walk down 42nd Street) without having to confront several persons attempting to sell them marijuana (or other drugs).

In 1970, almost 90% of college students using marijuana monthly or more often reported some cannabis sales; this was 21% of all students (Blacks and Whites were equally likely to use and sell (Carpenter et al. 1988; Johnson 1973) and the proportions of marijuana sellers was almost certainly as high or higher among inner-city marijuana users. Over half of the marijuana sellers also sold other illicit drugs they used. Those who sold three or more hard drugs were substantially more deviant on virtually all dimensions than persons who only sold or used marijuana (Johnson 1973). Indeed, the overall best indicator of a highly deviant lifestyle was the number of different drugs sold rather than the frequency of marijuana use (see also Carpenter et al. 1988).

In 1970, Ross began selling PCP, a little-known drug at the time. Although he occasionally sold marijuana, he specialized in PCP sales and did quite well through the 1970s. For the most part, marijuana was always a secondary drug of use and sale among Island's children, nephews, and nieces.

Heroin Sales

Heroin use was known among White ethnics and relatively small numbers of jazz musicians; its use began to grow among Harlem youths in 1955 (Preble & Casey 1969; Brown 1965; Malcolm X & Haley 1965) but remained less common than later in the 1960s. Among young men in Manhattan, onset of heroin use increased from 3% in 1963, peaked at 20% between 1970 and 1972, and began to decline as 13% used heroin in 1974 (Clayton & Voss 1981; Boyle & Brunswick 1980); the proportion initiating heroin probably declined further and remained low in the late 1970s. Thus, very low proportions of youths reaching adulthood after 1975 in Harlem and inner-city New York have initiated or become regular users of heroin. A definite norm against heroin use has become widespread among high-risk youths under age 20. Among those who initiated heroin injection during the heroin era, sizable proportions became addicted within two years. While less than half persist in their addiction for several years (Johnson 1978), this heroin-era cohort (estimated at 200,000 in New York City) constitutes the vast majority of heroin addicts who are in their thirties and forties in the 1990s (Frank 1986).

Moreover, almost all heroin abusers engaged in some form of heroin sales and other drug distribution activity, including direct sales, steering customers to sellers, touting a dealer's bag, copping drugs for customers who never meet, or performing a variety of other roles that protect or assist in the sale of heroin (Johnson, Hamid & Sanabria 1991; Johnson, Kaplan & Schmeidler 1990; Johnson et al. 1985). Heroin abusers occasionally also sold cocaine powder and marijuana, but these sales typically occurred on fewer days and generated less cash income than heroin; they frequently used these drugs while selling them.

The important point is that a large pool of heroin abusers had established patterns of irregular sales of heroin and cocaine, and received low to modest returns for several hours of dealing activity. Their sales were primarily designed to support their consumption of heroin, sometimes combined with cocaine. Perhaps some kilo level suppliers were making sizable profits, but street heroin abusers were generally not making enough to keep themselves supplied with the heroin they needed; very few made substantial monetary returns or clear profits from such sales. This pattern of heroin sales with marginal returns to heroin abusers continued into the crack era and the 1990s.

Island's daughter reached age 17 in 1970, during the peak years for heroin initiation. Sonya began heroin use and rapidly became addicted. Various children of Island's siblings were also caught in the heroin epidemic of the 1970s. Sonya married a heroin addict and dealer who helped support her heroin addiction. While married, she prostituted and lived mostly in shooting galleries with her husband. While they have separated and he now lives in Florida, he returns for visits on occasions. By 1973 when he reached age 18, Ross claimed to have avoided heroin addiction. Ross and many other Harlem youths (Brunswick 1988; Boyle & Brunswick 1980) observed what happened to virtually all his cousins and his sister and refused to consume heroin. He also tried to talk his cousins out of shooting heroin. In the 1970s, Ross felt so deeply about his sister's addiction that he “beat her bad enough” to discourage her from using it, but this treatment regime was not successful. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Ross sold heroin, but avoided using it. He hated selling this drug, but “the money was good.” Numerous kin were low-level heroin abusers and sellers. Most of these addicts spent intermittent periods in jail or prison.

Cocaine Powder Sales

While cocaine had been available before 1960, it was expensive and difficult to obtain. However, from 1975 to 1985 the use of cocaine powder grew steadily. Cocaine powder became the status drug for both rich and poor alike. Very substantial proportions of marijuana-using adolescents during the period from 1965 to 1979 became cocaine users as adults (Kandel, Murphy & Karus 1985; Kozel & Adams 1985). The greater and more frequent their cocaine use, the more likely they were to sell it.

The patterns of inner-city cocaine powder sales followed closely those of heroin, but with some important variations. In New York City, many cocaine habitués in the mid-1970s began attending after-hours clubs, which became a major socialization location for cocaine dealers who both used and dealt large amounts of cocaine. But patrons at after-hours clubs were expected to control their urges for cocaine and “be cool” (Hamid 1992; Williams 1978). Such cocaine sellers generally avoided heroin use and heroin abusers as customers, preferring to provide cocaine to those who wished to snort it. In the mid-1970s, cocaine users were probably three to five times more numerous than heroin users (Preble 1980). Cocaine powder dealers could usually earn enough cash to make a profit and support their own use, but not to supply their friends (Williams & Kornblum 1985). Between 1981 and 1984, cocaine free-basing began to confront cocaine sellers with a major problem. Sellers and persons who could base cocaine had a lively business, but smoking cocaine quickly ate up profits. Several major West Indian marijuana dealers quickly lost their profits and livelihood (Hamid In press, 1990).

While Sonya frequently injected cocaine with heroin (speedballing), she rarely used cocaine powder for snorting. Ross occasionally snorted cocaine during the 1970s but did not sell it. His main business was heroin and PCP sales.

Crack Sales

Between 1984 and 1985, crack use exploded in New York City (Golub, Lewis & Johnson 1991; Johnson, Hamid & Sanabria 1991). Prepared freebased cocaine was placed in small vials for retail sale at $3 to $10 per vial (price depended on size of vial and the street market). Virtually all crack abusers had prior experience with marijuana, cocaine powder or heroin; almost no drug-naive persons were recruited to crack use as their first drug (Fagan & Chin 1991; Fagan 1990). Unlike snorting cocaine, however, the rewards of the instant high and avoidance of dysphoria created many repeated episodes of use per day. While heroin users and cocaine snorters may consume their drug two to three times per day, many crack abusers consumed crack five to 15 times per day, limited primarily by their income. While relatively few new abusers emerged, among cocaine snorters or freebasers, crack consumption was usually added to preexisting drug abuse patterns, but they used crack two to three times as often as other drugs. In short, crack was used more intensively (higher frequencies and expenditures, especially among daily users) than was heroin or cocaine powder (Johnson, Elmoghazy & Dunlap 1990).

The primary means for supporting such crack consumption was crack selling. Because of the large number of purchases per day by most crack abusers, crack developed as an essentially new market. Even persons who limited their drug consumption to marijuana, cocaine powder or heroin, but who sold drugs, typically added crack to their sales activity (Fagan 1992). Crack sales generated higher cash incomes than the sale of heroin, cocaine powder or marijuana, or the commission of other crimes (e.g., robbery, burglary, thefts).

Overall, during the crack era, a significant expansion in the number of daily drug abusers seems to have occurred. In New York City, a substantial majority of an estimated 150,000 persistent heroin injectors appears to have added crack abuse and sale to their daily activities. A relatively small proportion (probably less than 20%) of recreational cocaine snorters (who avoid heroin) became crack abusers (Frank et al. 1988). But since recreational cocaine snorters were so numerous, substantial numbers became crack abusers. While precise figures are not available, the Senate Committee on the Judiciary estimated that in 1990 New York State had 434,000 cocaine or crack addicts; the same report estimated that nationally 2.2 million persons are cocaine addicts (Johnson, Dunlap & Hamid 1992; U.S. Senate 1990).

A study of Washington, D.C., probationers suggests that crack selling is very profitable. Many sellers sold crack for only short periods each week, but had earnings that were several times higher than the minimum wage or legal earnings (Fagan 1992; Reuter et al. 1990). Several studies suggest that some minorities engaged in crack sales but without using crack (Reuter et al. 1990), although noncrack-using crack sellers appear to be rare in New York City.

Sonya moved to crack rapidly when it became available. She was one of several heroin abusers who gave up heroin in favor of crack. She and three female relatives are crackheads, prostituting themselves daily for crack. As soon as they earn a few dollars from a trick, they immediately buy and smoke crack. Or they will exchange sex for crack without ever receiving money. Sonya never became a crack seller. Her brother sets aside hits for her. Her ex-husband will also supply her minimally when in New York. She finds it more beneficial to prostitute to support her habit because the money is steady and quick. She does not have to be responsible for the drug or money. In her view, prostitution leaves her carefree.

As crack began to become popular in the mid-1980s, Ross was once waiting in line with friends to buy freebase cocaine. He observed how many people were consuming crack and realized that he could make much more money selling crack than heroin or angel dust. He sought out those who knew how to cook up freebase. Once Ross became a competent cooker, he began to buy cocaine, in small amounts at first (e.g., $300 worth), cook it up, place it in vials, and sell it.

At first Ross gave out free samples to encourage users to return for purchase. He joined with other free-lance crack sellers and they took over a comer on a main avenue. Ross had long established himself as a dealer there and had his legitimate territory. While he snorts cocaine, Ross reports rarely smoking crack; he limits his consumption so that his business is maintained. When he cooks up crack for sales, he lets his crack-using relatives (including his sister) consume what he “leaves on the mirror”; this practice helps assure that they do not steal from him or set him up for a robbery.

At least during the expansion years between 1985 and 1988, crack selling was quite profitable for thousands of inner-city minorities, although many of these sellers became severely impoverished by their crack use. An interesting paradox arises: crack sales bring monetary wealth to some households in the subculture of poverty. That is, household-families that have been impoverished for generations will suddenly have some members with money in their pockets to buy what they want. In some cases, the illicit income provides sufficient money for the household. But these members have little or no access to the banking system, middle-class lifestyles, or ways of accumulating wealth (other than stashes of cash or jewelry).

The cash income from Ross's crack sales provides Island with much of the cash with which she pays the apartment's rent and purchases food for persons living in or visiting the household. Ross may earn $500 to $1000 when he has a good day; this may happen several times a year. Just before Christmas in 1990, for example, the family paid cash and installed an entire new living room set (e.g., couch, chairs, table, lamps). They have a large freezer stocked with food, everyone has several changes of clothing, and Ross and Island always have money in their pockets. Sonya and other kin in the household can never keep money (it is spent on crack), but they eat and sleep free and dress very well. In many respects, although no family member has a legal job or off-the-books legal income, the illicit income among the adults appears to be quite high. Certainly on days when they prostitute (which is most days), Sonya and other females earn more cash income in that day than a research fieldworker with a doctorate. Since all cash is immediately spent on crack, they remain impoverished. Ross can easily net over $100 a day when he works, but sometimes does not work. Because he is not a compulsive crack smoker, Ross earns enough to provide sufficient cash to keep the household solvent — even well-off by Harlem community standards.

But neither Ross nor Island has a bank account. They know little about income and expenses, they do not budget or plan expenditures, they have no plans to invest in a better apartment or car, and they know nothing about savings or financial instruments, such as stocks and bonds. So the household supports five to ten persons living there at one time. Family members “eat off the stove” (never at a sit-down meal). Ross is effectively subsidizing Sonya, Island, and other kin and friends who happen to be living in the household. Since the crack business is lucrative, and his younger male cousins (ages 17 to 25) were unable to find legal employment. Ross offered them work selling crack; most were quickly arrested and imprisoned for various offenses.

Most household members remain vigorous participants in the subcultures of violence, poverty, and drug abuse. Numerous squabbles and arguments break out on all subjects, but especially over drugs. For example, Ross and Sonya's cousin, Barbara (age 35) and her daughter, Susan (age 18), had both been raised by Island and frequently lived in Island's household in 1990. Barbara and Susan were crack prostitutes who routinely worked together. Barbara was temporarily living with an older john at his apartment. One evening in 1991, Susan came there while intoxicated and paranoid on crack and demanded money for crack. Barbara reported having no money so Susan beat her with a broom handle. When the john tried to stop her, Susan pulled out a knife and stabbed him repeatedly. Barbara was hospitalized and died shortly afterward. At her funeral, Susan was ostracized by all family and kin members; all drank heavily and used a variety of drugs during the wake.

Although Ross does not sell crack directly to his kin, a unique economic system appears to have evolved. The criminal gains from prostitution and other nondrug crimes by several crack abusers are rapidly spent on crack. These funds provide substantial income to crack sellers (like Ross) and/or his suppliers who are controlled (at least not compulsive crack) cocaine users. The net income from such crack sellers appears to provide the cash that supports household-families (like Island's) in which several crack abusers live (at least temporarily), eat, clean up, get clothing on occasion, and hang out. Of course, many crack abusers do not have such households that tolerate crack sellers or relatives who will subsidize them, so they live on the streets, in abandoned buildings or in shelters.

Stressed Household-Family Systems

A second major vector promoting ghettoization is the distressed inner-city household-family system described briefly above. Dunlap (In press-a, 1992) described the impact of crack on various households — from completely unstable to least unstable households.

Several important themes developed more fully elsewhere (Dunlap In press-a, 1992, 1991; Bourgois & Dunlap 1992) have important policy implications and represent a shift from the 1960s, especially when compared with the case materials provided in the culture of poverty (Lewis 1965). While important shifts in family composition have occurred since 1960 (e.g., higher proportion of single-family households), the critical shifts revolve around social processes and expectations among family members, both day by day and over the years:

An especially important shift across the generations is a decline in expectation that a young female will provide the primary care for children born to her. This trend has meant a rise in parenting by grandparents or older female relatives.

While most would like to have their own household, young adults quickly realize that they do not and will never have the income to afford their own household (e.g., to pay rent and maintain an apartment). They adjust to a permanent status of never having their own residence and to living with other family, relatives, temporary liaisons, or friends (if fortunate), or in shelters or streets (if not).

The option of a steady legal job appears so distant for inner-city high-school dropouts (and even graduates), that they cease job searches after a few attempts or experiences in low-wage jobs. Adult household members can rarely provide concrete assistance in finding jobs or help in accessing networks of employers. Such youths and young adults, with no hopes for legal work, are available for recruitment and work in illegal enterprises; drug sales loom largest among these opportunities.

Within the household-family, verbal aggressiveness and willingness to resort to physical violence appear to have increased as a means of both expressing love and settling disputes.

Conclusion

Numerous economic, sociological, and psychological studies have documented the decline of America's inner cities, and the worsening of chronic conditions therein. All of the macro social forces worsened during the 1970s and 1980s. These forces engendered numerous crisis situations, which converged in the mid-1980s to provide the setting for the crack era.

While the crack epidemic may be easing somewhat in 1991, severely impacted individuals — like Sonya, Barbara, Ross (Dunlap 1992) and household-families (like Island's) will continue to be negatively impacted by the behavior of crack abusers and problems with their children. They will also gain a few benefits if a household member can provide some income through crack sales.

Furthermore, the federal, New York State, and New York City budgets being debated at the time of writing are likely to extract an additional $1 billion to $5 billion in government services and goods that were previously provided to residents of New York's inner city. These cuts are in addition to the retreat from and absence of private investment and employment in the inner city. Even if youths reaching adulthood in the 1990s avoid crack and heroin completely, the absence of legal employment, declining value of welfare benefits, and many other forces will provide them with no or few options other than engaging in criminality or the drug business.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Harry Sanabria, of the University of Pittsburgh, for his contributions to this paper and research.

Footnotes

Supported by the Urban Institute's Urban Opportunities Program and presented at the Conference on Drugs, Crime, and Social Distress in Philadelphia, April 1991. This article also relies on much prior conceptualization and research by the authors on the Natural History of Crack Distribution, a project funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1 R01 DA05126-04) as well as from other projects funded by NIDA (1 R01 DA01926-07, 5 T32 DA07233-08, 1 R01 DA06615-02), by the National Institute of Justice (80-IJ-CX-0049S2, 87-IJ-CX-0064, 91-IJ-CX-D014), and by support from Narcotic and Drug Research, Inc.

The opinions expressed do not necessarily represent official positions of the United States Government, National Development and Research Institutes, Inc. or the Urban Institute.

Poverty among Blacks had declined to 30% by 1969, but has remained unchanged to 1984 (Jaynes & Williams 1989).

A parallel and vigorous market in marijuana existed among Whites and hippies of the marijuana era; this market relied on private sales generally in the customer's or seller's home, and avoided street sales and storefront sales (Carpenter et al. 1988).

References

- Austin J, McVey A. Focus (newsletter) San Francisco: National Council on Crime and Delinquency; 1989. Dec, The impact of the war on drugs. [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley A. White Families, Black Families. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn AJ. Single Room Occupancy in New York City. New York: New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle J, Brunswick AF. What happened in Harlem? Analysis of a decline in heroin use among a generation unit of urban black youth. Journal of Drug Issues. 1980;10(1):109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. Manchild in the Promised Land. New York: Signet Books; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Brunswick AF. Young black males and substance use. In: Gibbs JT, editor. Young, Black, and Male in America: An Endangered Species. Dover, Massachusetts: Auburn House; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Jail Inmates 1991. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 1992a. May, [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Prisoners in 1991. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 1992b. May, [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Prisoners in 1989. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 1990. May, [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter C, Glassner B, Johnson BD, Loughlin J. Kids, Drugs and Crime. Lexington, Massachusetts: Lexington Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan MW, Parsons LE. Historical Corrections Statistics in the United States, 1850-1984. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Chein I, Gerard DL, Lee RS, Rosenfeld E. The Road to H. New York: Basic Books; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Clark K. Dark Ghetto. New York: Harper & Row; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton RR, Voss HL. Young Men and Drugs in Manhattan: A Causal Analysis. Rockville, Maryland: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AK. Delinquent Boys. Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Coles R. Children of Crisis III: The South Goes North. Boston: Little, Brown; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Coles R. Children of Crisis II: Migrants, Sharecroppers, Mountaineers. Boston: Little, Brown; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R. Young black males and delinquency. In: Gibbs JT, editor. Young, Black, and Male in America: An Endangered Species. Dover, Massachusetts: Auburn House; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Dolbeare C. The low income housing crisis. In: Hartman C, editor. America's Housing Crisis: What Is to Be Done? Boston: Routledge & Degan Paul; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Downs A. Rental Housing in the 1980s. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap E. Inner-city crisis and crack dealing: Portrait of a drug dealer and his household. In: MacGregor S, editor. Crisis and Resistance: Social Relations and Economic Restructuring in the City. London: Edinburgh Press; In press-a. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap E. Impact of drugs on family life and kin networks in the inner-city African-American single-parent household. In: Harrell A, Peterson G, editors. Drugs, Crime, and Social Isolation: Barriers to Urban Opportunity. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap E. Rachael's place: Case study of a female crack distributor. Paper presented at the Meeting of the American Society of Criminology; San Francisco. November 21.1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J. Drug selling and licit income in distressed neighborhoods: The economic lives of street-level drug users and dealers. In: Harrell A, Peterson G, editors. Drugs, Crime, and Social Isolation: Barriers to Urban Opportunity. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J. Special Issue on Crack Cocaine. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1990;1617(4)(1) [Google Scholar]

- Fagan JA, Chin K. Social processes of initiation into crack. Journal of Drug Issues. 1991;21(2):313–344. [Google Scholar]

- Frank B. What is the future of the heroin problem in New York City. Paper presented at the Third Annual Northeast Regional Methadone Conference; Baltimore, Maryland. December 3.1986. [Google Scholar]

- Frank B, Morel R, Schmeidler J, Maranda M. Cocaine and Crack Use in New York State. New York: Division of Substance Abuse Services; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Frey WH. Black in-migration, white flight, and the changing economic base of the central city. American Journal of Sociology. 1980;85(6):1396–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs JT. Young, Black, and Male in America: An Endangered species. Dover, Massachusetts: Auburn House; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow D. The Black Underclass. New York: Vintage Books; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Lewis C, Johnson BD. Modeling the epidemic of onset to crack abuse. 1991 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Grier WH, Cobbs PM. Black Rage. New York: Bantam; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid A. The Political Economy of Drugs: The Caribbean Connection. New York: Plenum; In press. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid A. The developmental cycle of a drug epidemic: The cocaine smoking epidemic of 1981-1991. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1992;24(4) doi: 10.1080/02791072.1992.10471658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid A. The political economy of crack-related violence. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1990;17(1):31–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman C, editor. America's Housing Crisis: What Is to Be Done? Boston: Routledge & Degan Paul; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman C, Keating D, Le Gates R. Displacement: How to Fight It. Berkeley, California: National Housing Law Project; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Hill R. The Strengths of the Black Family. New York: National Urban League; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper K, Hamberg J. The Making of America's Homeless: From Skid Row to New Poor, 1945-1984. New York: Community Service Society; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes MA. Report prepared for the Rockefeller Foundation Princeton. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, Princeton Urban and Regional Research Center; 1988. Concentrated Deviance or Isolated Deprivation?: The “Underclass” Idea Reconsidered. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt LG, Chambers CD. The Heroin Epidemics: A Study of Heroin Use in the US, 1965-75. Part II. Holliswood, New York: Spectrum; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Jargowsky PA, Bane MJ. Neighborhood poverty: Basic questions. In: Jencks C, Peterson G, editors. The Urban Underclass. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jaynes GD, Williams RM., Jr . A Common Destiny: Blacks and American Society. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Jencks C, Peterson G, editors. The Urban Underclass. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD. Once an addict, seldom an addict. Contemporary Drug Problems Spring. 1978:35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD. Marijuana Users and Drug Subcultures. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B, Dunlap E, Hamid A. Changes in New York's crack distribution scene. In: Vamos PA, Corriveau P, editors. Drugs and Society to the Year 2000. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Information Agency; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Elmoghazy E, Dunlap E. Crack Abusers and Noncrack Drug Abusers: A Comparison of Drug Use, Drug Sales, and Nondrug Criminality. New York: Narcotic and Drug Research, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Frank B, Morel R, Schmeidler J, Maranda M, Gillman C. Illicit Drug Use Among Transient Adults in New York State. Albany, New York: Division of Substance Abuse Services; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Goldstein P, Preble E, Schmeidler J, Lipton D, Spunt B, Miller T. Taking Care of Business: The Economics of Crime by Heroin Abusers. Lexington, Massachusetts: Lexington Books; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Hamid A, Sanabria H. Emerging models of crack distribution. In: Mieczkowksi T, editor. Drugs and Crime: A Reader. Boston: Allyn-Bacon; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Kaplan MA, Schmeidler J. Days with drug distribution: Which drugs? How many transactions? With what returns? In: Weischeit RA, editor. Drugs, Crime, and the Criminal Justice System. Cincinnati, Ohio: Anderson; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Lipton DS, Wish E. Facts About the Criminality of Heroin and Cocaine Abusers and Some New Alternatives to Incarceration. New York: Narcotic and Drug Research, Inc.; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Manwar A. Towards A paradigm of drug eras: Previous drug eras help to model the crack epidemic in New York City during the 1990s. Paper presented at the Meeting of the American Society of Criminology; San Francisco. November 21.1991. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Muffler J. Sociocultural aspects of drug use and abuse in the 1990s. In: Lowinson J, Ruiz P, Millman R, Langrod J, editors. Substance Abuse Treatment. 2nd. Baltimore: Wilkins and Wilkins; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Williams T, Dei K, Sanabria H. Drug abuse in the inner city: Impact on hard drug users and the community. In: Tonry M, Wilson JQ, editors. Drugs and Crime. Vol. 13. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. (Crime and Justice). [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Murphy D, Karus D. Cocaine use in young adulthood: Patterns of use and psychosocial correlates. In: Kozel N, Adams EH, editors. Cocaine Use in America: Epidemiologic and Clinical Perspectives. Vol. 61. Rockville, Maryland: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1985. (Research Monograph). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasarda JE. The severely distressed in economically transforming cities. In: Harrell A, Peterson G, editors. Drugs, Crime, and Social Isolation: Barriers to Urban Opportunity. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kozel NJ, Adams EH, editors. Cocaine Use in America: Epidemiologic and Clinical Perspectives. Vol. 61. Rockville, Maryland: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1985. (Research Monograph). [Google Scholar]

- Langan PA. America's soaring prison population. Science. 1991;251:1568–73. doi: 10.1126/science.251.5001.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis O. La Vida. New York: Basic Books; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Lyman S. Legitimacy and consensus in Lipset's America: From Washington to Watergate. Social Research. 1975;42:729–757. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm X, Haley A. Autobiography of Malcolm X. New York: Signet; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Mauer M. Young Black Men and The Criminal Justice System: A Growing National Problem. Washington, D.C.: The Sentencing Project; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan DP. The Black Family: The Case for National Action. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Family Planning and Research; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Myrdal G. Challenges to Affluence. New York: Pantheon; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. US Riot Commission Report. New York: Bantam Books; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. Permanent Homelessness in America? Washington, D.C.: U.S. GPO; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Phillipe B, Dunlap E. Exorcising sex-for-crack: An ethnographic perspective from Harlem. In: Ratner M, editor. Crack Pipe as Pimp: An Eight-City Study of the Sex for Crack Phenomenon. New York: Lexington Books; In press. [Google Scholar]

- Preble EJ. Personal Communication. New York: Narcotic and Drug Research, Inc.; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Preble EJ, Casey JJ. Taking care of business: The heroin user's life on the street. International Journal of the Addictions. 1969;4(1):1–24. doi: 10.3109/10826089709027307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed RJ. Education and achievement of young black males. In: Gibbs JT, editor. Young, Black and Male in America: An Endangered Species. Dover, Massachusetts: Auburn House; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter P, MacCoun R, Murphy P, Abrahamse A, Simon B. Money from Crime: A Study of the Economics of Drug Dealing in Washington, DC. Santa Monica, California: Rand; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts E, Sawhill I. Defining and measuring the underclass. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 1988;7(2):316–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ropers RH. The Invisible Homeless: A New Urban Ecology. New York: Insight Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sanjek R. Federal Housing Programs and Their Impact on Homelessness. New York: National Coalition for the Homeless; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JP. Poverty and the family. In: Sandefur GD, Tienda M, editors. Divided Opportunities. Minorities, Poverty, and Social Policy. New York: Plenum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M. Getting Paid. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker W. The Excluded Americans Homelessness and Housing Politics. San Francisco: Laissez Faire Books; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary. A Staff Report. 101st Congress. Washington, D.C.: U.S. GPO; 1990. Hardcore cocaine addicts: Measuring—and fighting—the epidemic. [Google Scholar]

- Williams T. The Cocaine Kids. New York: Addison-Wesley; 1989. [Google Scholar]