Abstract

The β3 integrin family members αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 signal bidirectionally through long-range allosteric changes, including a transition from a bent unliganded-closed low-affinity state to an extended liganded-open high-affinity state. To obtain an atomic-level description of this transition in an explicit solvent, we carried out targeted molecular dynamics simulations of the headpieces of αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 integrins. Although minor differences were observed between these receptors, our results suggest a common transition pathway in which the hybrid domain swing-out is accompanied by conformational changes within the β3 βA (I-like) domain that propagate through the α7 helix C-terminus, and are followed by the α7 helix downward motion and the opening of the β6-α7 loop. Breaking of contact interactions between the β6-α7 loop and the α1 helix N-terminus results in helix straightening, internal rearrangements of SDL, movement of the β1-α1 loop toward the metal ion dependent adhesion site (MIDAS), and final changes at the interfaces between the β3 βA (I-like) domain and either the hybrid or the α β-propeller domains. Taken together, our results suggest novel testable hypotheses of intra-domain and inter-domain interactions responsible for β3 integrin activation.

Keywords: Activation, αIIbβ3, αVβ3, transition pathway, simulation

INTRODUCTION

The β3 integrin subunits can form heterodimeric cell surface receptors with either the αIIb subunit (GPIIb; CD41) or the αV subunit (CD51). Specifically, αIIbβ3 is found on the surface of platelets and megakaryocytes, and plays a central role in platelet physiology.1 In contrast, αVβ3 is expressed on a wide variety of cells and may play a role in bone resorption, angiogenesis, and tumor metastasis.2 The αIIb and αV subunits share relatively high structural homology3 (∼40% sequence identity) and both can bind von Willebrand factor, fibronectin, and vitronectin through the cell recognition sequence Arg-Gly-Asp, RGD. Despite their structural and functional similarities, integrins αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 display qualitative and quantitative differences in their ability to bind synthetic or natural peptides, small molecules,4 and fibrinogen,5,6 as well as in the ion regulation of ligand binding.7-10

Like other integrins, β3 integrins can signal bidirectionally through long-range allosteric changes that are induced by the interactions of their short cytoplasmic tails with intracellular proteins (inside-out signaling) or by interactions of their extracellular domains (ectodomains) with extracellular matrix components or soluble ligands (outside-in signaling).11-15 Recent crystallographic, biophysical, and biochemical studies have significantly improved our understanding of the mechanisms underlying β3 integrin function by providing atomic resolution structural information. Specifically, the crystal structures of the ectodomain of αVβ3 in the absence or presence of an RGD-containing peptide (cilengitide)16-18 revealed that: 1) The inactive receptor is in a 135° bent conformation with both the αV (β-propeller domain) and β3 subunits [βA (I-like) domain] contributing to the RGD binding site; 2) The liganded receptor contains three divalent metal ions in its binding pocket at specific sites (i.e., MIDAS or metal ion dependent adhesion site, LIMBS or ligand-associated metal binding site, and ADMIDAS or adjacent to MIDAS); 3) The ligand is directly involved in the coordination of the MIDAS metal ion; 4) The ADMIDAS is the only metal ion exhibiting a clearly defined electron density in the αVβ3 unliganded receptor; and 5) There is relatively little change in the overall conformation of the bent αVβ3 receptor after soaking in the RGD peptide cilengitide. A recently published crystal structure of the complete ectodomain of integrin αIIbβ3 19 also revealed a bent, closed, low-affinity conformation, in addition to the β knee, and the full occupancy of the metal binding sites in the βA (I-like) domain with Ca2+ and Mg2+ in the physiologic low-affinity state. Since the LIMBS metal ion was present in the unliganded state, it was renamed the synergistic metal binding site (SyMBS) 19.

Co-crystals of the integrin αIIbβ3 headpiece bound to ligand-mimetic antagonists, cacodylate ions, or the γ-chain peptide of fibrinogen20,21 provided a high resolution structure consistent with earlier observations from electron microscopy (EM) studies of liganded αVβ3 and αIIbβ39,22-24 that ligand binding is associated with the protein adopting an open conformation through a swing-out of the β3 hybrid domain. In addition, these structures revealed that ligand binding is associated with: 1) Loss of the interaction between the ADMIDAS metal ion and the carbonyl of M335 on the β3 β6-α7 loop; 2) Straightening of the α1 helix and its movement (along with the ADMIDAS metal ion) toward the MIDAS; 3) A marked downward movement (∼6 Å) of the α7 helix, leading to a 60° rotation of the hybrid domain around a hinge point connected to the βA (I-like) domain; 4) A 70 Å movement of the β3 PSI domain away from αIIb; and 5) A major reorganization of the interface between the βA (I-like) and hybrid domains20,21.

EM studies of purified integrin αVβ3 in the presence of Mn2+ or RGD ligand9 and of purified αIIbβ3 bound to fibrinogen led to a “switchblade” model of integrin activation in which leg separation22-25 and headpiece extension are required for activation.9 An alternative “deadbolt” hypothesis has been proposed in which release of the interaction between the β3 subunit terminal domain (βTD) and the βA (I-like) domain is sufficient for ligand binding, with headpiece extension occurring only after ligand binding.26 Data supporting each hypothesis have been reported, as have data that appear inconsistent with each.27-31 Despite these conflicting views, there is strong support for the importance of the swing-out motion of the hybrid domain and the downward movement of the α7 helix of the βA (I-like) domain in achieving high affinity ligand binding,32-35,36 but the precise sequence of events during the conformational transitions of β3 integrins from low-affinity to high-affinity states remains unclear.

Puklin-Faucher et al.37 used both conventional molecular dynamics (MD) and steered molecular dynamics (SMD) simulations of a model of the αVβ3 headpiece [αV subunit β-propeller and β3 βA (I-like) and hybrid domains] in complex with a fibronectin fragment that was used in place of the RGD ligand of the crystal structure of αVβ317 to assess the intrinsic motions of the liganded form of the receptor headpiece in the absence of constraints that may be imposed by headpiece-tailpiece interactions. The authors observed: 1) Spontaneous partial opening of the β3 βA (I-like)/hybrid domain hinge for the liganded-closed state when all ionic sites (LIMBS, MIDAS, ADMIDAS) were occupied by Mg2+; 2) An allosteric transition pathway along which ligand interaction induces elastic distortions of the α1 helix, leading to a partial swing-out of the hybrid domain; and 3) Swing-out acceleration along the same allosteric pathway with SMD.37 Since this study started with the structure of the liganded-bent αVβ3 it could not provide information on the transition from the unliganded state to the liganded state.

In the current study we employed targeted molecular dynamics (TMD) simulations38-40 to provide a stochastic pathway of the swing-out transition from unliganded-closed low affinity (inactive) to liganded-open high affinity (active) states of both β3 integrins, αIIbβ3 and αVβ3. These TMD simulations produced stereochemically feasible pathways with candidate intra-domain and inter-domain interactions responsible for β3 integrin activation that can now be tested experimentally.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

All MD simulations were performed using version c32a2 of the CHARMM biomolecular simulation software41 alongside the CHARMM22 all-atom protein force field. Molecular graphics were generated with Pymol42 and VMD.43

Molecular systems

We simulated the upper leg portion of the two subunits of integrin αIIbβ3 or αVβ3, i.e., αIIb/αV β-propeller and thigh domains (residues 1-592 or 1-586, respectively), and β3 βA (I-like), hybrid, and PSI domains (residues 1-434). For both the unliganded-closed and liganded-open forms of either αIIbβ3 or αVβ3, the starting coordinates of the α-subunit were extracted from the corresponding full-length model of the integrin ectodomain obtained with MODELLER 8v244 as previously described for αIIbβ3.45 Specifically, the starting conformation of the αIIb headpiece was built using: a) the corresponding coordinates of the crystal structure of αIIbβ3 in complex with eptifibatide (PDB ID: 1TY6, chain A, residues 1-452)20 for the αIIb β-propeller domain, and b) the corresponding coordinates of the αVβ3 crystal structure (PDB ID: 1U8C, chain A, residues 439-586)18 as a template for the thigh domain (αIIb residues 453-592). Although a crystal structure refinement (PDB ID: 2VDN) of the eptifibatide-bound αIIbβ3 complex was released after completion of this work, it did not exhibit significant differences from 1TY6 (the root mean square deviation (RMSD) between the two structures in the region we simulated was below 0.2 Å). The starting conformation of the simulated αV subunit was taken from the unliganded-closed crystal structure of αVβ3 (PDB ID: 1U8C, chain A, residues 1-586).18 Metal ions (Ca2+) located within the β-propeller domains of αIIb or αV were kept in place in the selected initial conformations. The coordinates of the β3 fragment of the unliganded-closed forms of αIIbβ3 or αVβ3, namely βA (I-like), hybrid, and PSI domains, were taken from the bent full-length models of αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 ectodomain45 based on αVβ3 crystal structure (PDB ID: 1U8C, chain B, residues 1-432),18 including the ADMIDAS ion (Ca2+). Those of the liganded-open state were extracted from the crystallographic structure of the αIIbβ3 integrin fragment in complex with eptifibatide (PDB ID: 1TY6, chain B, residues 1-432), preserving the SyMBS (Ca2+), MIDAS (Mg2+), and ADMIDAS (Ca2+) metal ions,20 but not the ligand for initial structural relaxation. Finally, five water molecules found in the αIIbβ3 crystal structure to participate in metal ion coordination in the β3 βA (I-like) domain were added or kept in place in all selected initial conformations. A glycerol molecule involved in the coordination of ADMIDAS was replaced by a water molecule, and also added to the simulation setups.

Protein hydrogen atoms were then added to these initial molecular models using HBUILD within the CHARMM package.41 Histidines were all delta nitrogen protonated, unless electron donors were found close to these atoms, or electron acceptors were close to epsilon nitrogens. In particular, the αIIb H255 that is close to the binding site was protonated at the delta nitrogen. Hydrogen positions were minimized using 500 steps of steepest descent followed by a series of cycles of 500 steps of conjugate gradient minimization until the energy change ratio between cycles was lower than 0.01 kcal/mol (force constant = 1000 kcal mol-1 Å-2). Similarly, subsequent cycles of 500 steps of conjugate gradient minimization were applied for the minimization of the side-chains and the backbone, while maintaining the rest of the protein frozen (force constant = 1000 kcal mol-1 Å-2). Distance-dependent dielectric was used to compute electrostatic interactions and every cycle was repeated until the energy change ratio between cycles was lower than 0.01 kcal/mol. For the nonbonded interactions the force-switching method was used with a cutoff radius of 14 Å.

Following a protocol similar to the one reported by Flynn et al.,46 shells of 9,644 or 9,141 water molecules (∼ 7 Å cutoff around the solute) were placed around each conformational state of αIIβ3 or αVβ3, respectively, using the solvent-shell.str script by Lennart Nilsson (www.biosci.ki.se/md/charmm.html). The procedure yielded systems of 44,544 and 43,056 total atoms for αIIβ3 or αVβ3, respectively. For all unliganded and liganded states, the water shells were first equilibrated using 500 steps of steepest descent while keeping fixed the protein with a harmonic constraint (force constant = 1000 kcal mol-1 Å-2), and then further equilibrated with another cycle of 500 steps of steepest descent and 1000 steps of adopted basis Newton-Raphson while a small harmonic constraining force was imposed on the proteins atoms (force constant = 20 kcal mol-1 Å-2).

Choosing different starting velocities, different initial structures of the unliganded-closed and liganded-open states of αIIβ3 or αVβ3 were generated by additional 10 ps of MD while harmonically constraining the proteins atoms (force constant = 20 kcal mol-1 Å-2).

TMD simulations

The conformational transitions from the unliganded-closed to the liganded-open conformations of integrin αIIbβ3 or αVβ3 were simulated using both standard TMD and the restricted-perturbation TMD (RP-TMD) methods using the TMD module of CHARMM. The RP-TMD method 40 is a variant of the standard TMD method. The latter 38,39 uses a standard MD with a time-dependent constraining force that guides an initial structure of N atoms and Cartesian coordinates XI = (x1I,x2I,x3I...x3NI) towards a final target structure of Cartesian coordinates XT by reducing the distance ||X-XT|| between these two structures over time. This is implemented introducing a holonomic constraint of the form

| (1) |

where d(t) is the desired RMSD between X and the target structure XT. Formally, the coordinates at time t can be written as Xt = xt + pt, where xt is the position in absence of the holonomic constraint and pt = γ (Xt-dt-XT) is a perturbation induced by it. In contrast to standard TMD where γ is obtained by imposing the validity of (1) given d(t), in the restricted perturbation-TMD method γ is found by limiting the total perturbation Σi|pt i| to a preset value PF, and thus setting and minimizing d(t) in (1). In the restricted perturbation-TMD method, the unperturbed dynamics are recovered by letting PF become smaller. This important feature restricts the crossing of energy barriers in the presence of the perturbation, resulting in lower energy pathways than those generated by the standard TMD method.

Preliminary simulations from unliganded-closed to liganded-open conformations were carried out using the standard TMD algorithm. More than 3 ns in five different simulations for each of the β3 integrin systems in the presence of only one metal ion (ADMIDAS) in the binding site were generated using different equilibrated starting structures and initial velocities to analyze the repeatability of the resulting transition pathways. To assess the reversibility of these pathways, and the robustness of the data, four different RP-TMD trajectories for αIIbβ3 and four different RP-TMD trajectories for αVβ3 were performed in the presence of all three metal ions in the binding site (LIMBS, MIDAS, and ADMIDAS), for a total of about 5 ns simulations. Specifically, we generated two different equilibrated starting structures and initial velocities for each unliganded-closed or liganded-open integrin system to analyze the repeatability of the proposed transition pathways. Locations of LIMBS and MIDAS metal ions in unliganded-closed states (crystal structure used as a template only contains ADMIDAS) resulted from the RP-TMD simulations from liganded-open to unliganded-open conformations. Notably, these locations were very similar to those revealed by the recently published low-affinity crystal structure of the complete ectodomain of integrin αIIbβ319. To test whether the sequence of events occurring along the conformational change is reversible, for each system we carried out two independent reverse simulations starting from the liganded-open conformation and steering the system towards the unliganded-closed conformation. All simulations were performed setting the maximum value of the perturbation to PF= 0.001 Å.

No constraints were imposed during the simulations other than the TMD constraint φ(x) applied to all the atoms of the protein. In order to avoid an artificial rotation of the system all protein atoms were used for the fitting to the target structure d0 = 15 Å. The solvent molecules were allowed to move freely and to follow the dynamics of the protein. With the only exception of a few water molecules that evaporated into the vacuum, the water shells remained in contact with the protein throughout the entire simulations.

The first 10 ps of each TMD trajectory were regarded as an equilibration step (TMD constraint = 0) to ensure that no angular momentum was generated as the initial state was pulled towards the target conformation. A dynamic time step of 2 fs was used with the leapfrog integration scheme. The length of all bonds involving hydrogen atoms was kept constant by the SHAKE algorithm.47 The system was coupled to a 300 K heat bath to keep the temperature relatively constant.48

Analysis of the simulations

Analysis of the results was carried out using modules of CHARMM,41 and the bio3d add-on to the R statistical package.49 Inter-residue interactions were defined as contacts between residue side-chains that had centers of geometry within a 6.5 Å distance. Contacts were measured every 10 ps in each of the 8 RP-TMD simulation runs. A contact between two residues was considered “broken” when the distance between the centers of geometry of their side-chains became greater than 6.5 Å in an irreversible manner. A contact between two residues was considered “formed” when the centers of geometry of their side-chains became less than 6.5 Å.

In order to capture the evolution of the contacts formed and broken in the βA (I-like) headpiece during the dynamics, we considered the contact-map distance, defined as the Frobenius distance between the contact matrices:

| (2) |

where M(k)ij is 1 if the contact between residues i and j is formed in the conformation k, or 0 otherwise. For all the trajectories, we calculated the pairwise distances dCM(X(t1),X(t2)) and used the dissimilarity matrix obtained to cluster the structures. Clustering was obtained by application of an agglomerative hierarchical algorithm using the average distance method, and by cutting the clustering hierarchy to 9 clusters. The time evolution of the cluster membership was analyzed to obtain the dynamics in the reduced space defined by the cluster analysis.

The opening of the hinge angle between the β3 βA (I-like) and hybrid domains (red lines and arrow in Figure 1) was computed with the Wriggers and Schulten’s algorithm50 interfaced to VMD,43 using the starting structure as a reference. This algorithm monitors the movement of rigid domains about common hinges. In comparing two structures, the method partitions a protein into domains of defined geometry, and characterizes the relative movements of these domains by calculating their effective rotation axes.50

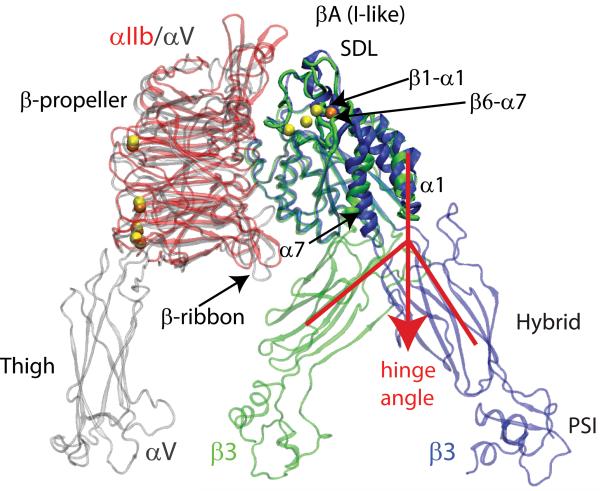

Figure 1. System Setup Used in the TMD Simulations of the Unliganded-closed to the Liganded-open States of β3 Integrins.

Comparison between the crystal structures of integrin αIIbβ3 in its liganded-open headpiece conformation (PDBID: 1TY6; color red for the αIIb β-propeller, blue for β3, and yellow for metal ions)20 and integrin αVβ3 in its unliganded-closed state (PDBID: 1U8C; color gray for both the β-propeller and thigh domains of αV, green for β3, and orange for metal ions).18 The regions of the β3 βA (I-like) domain that show the largest conformational differences are labeled and indicated with arrows. The relative opening of the hinge angle between the β3 βA (I-like) and hybrid domains that describes the swing-out motion of the hybrid domain is indicated by red lines and the red arrow.

RESULTS

We have simulated the hybrid domain swing-out movement between the unliganded-closed and liganded-open conformations of integrins αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 (Figure 1) using both standard TMD and RP-TMD.38-40 Although the results were qualitatively similar, as expected, we only obtained completely reversible transition pathways using the RP-TMD method. Thus, we only describe here in detail the results we obtained from these latter simulations. Headpieces composed of the upper legs of the integrin ectodomains (i.e., αIIb/αV β-propeller and thigh domains, and β3 βA (I-like), hybrid, and PSI domains) were used in the simulations (system setup shown in Figure 1). Transitions between the unliganded-closed and the liganded-open structures in the presence of the three LIMBS, MIDAS, and ADMIDAS metal ions in their binding sites, were achieved by reducing the 15 Å difference between the all atom coordinates of the starting and ending states (see Methods for details). Two different RP-TMD trajectories for each β3 integrin system and each direction (from unliganded-closed to liganded-open conformations, and vice versa) were performed using different starting velocities and slightly different structures of the equilibrated starting configurations (either unliganded-closed or liganded-open) of either αIIbβ3 or αVβ3 (see Methods for details). The RMSD between the different starting structures was ∼0.1 Å for the backbone atoms and ∼0.2 Å for all proteins atoms. Evolutions of the protein total potential energy and of the protein-water interaction energy during one of the simulations from unliganded-closed to liganded-open states are shown in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 for αIIbβ3 or αVβ3, respectively.

In order to assess the overall progress of the above transitions, we used the following different descriptors: 1) The overall RMSD with respect to the target structure and the opening of the hinge angle between βA (I-like) and hybrid domains (Figure 2); 2) The per-residue backbone RMSD of the βA (I-like) headpiece compared with the initial configuration (Figure 3); and 3) The evolution among clusters deriving from contact matrix analysis of the βA (I-like) domain (see Methods for further details) (Figure 4). The results of all these measurements are reported in detail below.

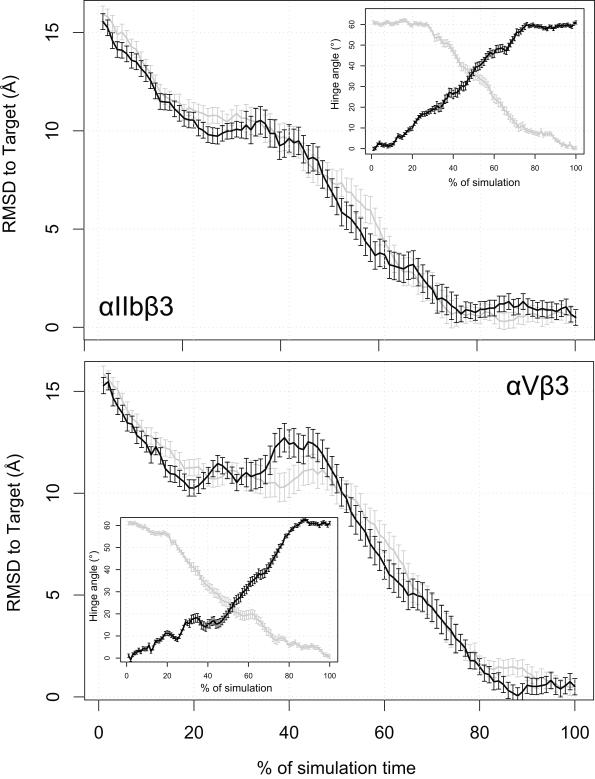

Figure 2. RMSD to the Target Configuration Calculated During the RP-TMD Runs.

The distance from the TMD target is illustrated for both αIIbβ3 (upper panel) and the αVβ3 (lower panel) integrins. The average over the two statistically independent simulations we carried out for each integrin system is represented as a solid line, in black for the forward (unliganded-closed to liganded-open) simulation and in gray for the backward (liganded-open to unliganded-closed) one, along with 95% confidence interval. The insets of the two panels illustrate the behavior of the hinge angle (see text) with the same color coding used above.

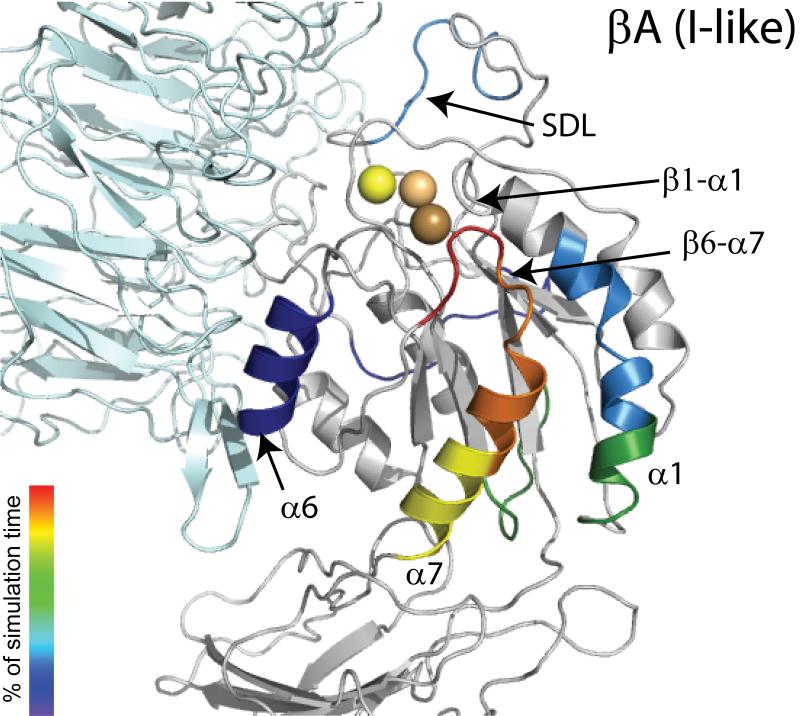

Figure 3. Sequence of Events During the RP-TMD Simulations of the Transition from Unliganded-Closed to the Liganded-Open States of αIIbβ3 integrin.

Structure of the unbound βA (I-like) domain showing the different secondary structure elements colored according to the order of significant conformational changes occurring during simulations with respect to the starting conformation. The α subunit is represented in cyan while SyMBS, MIDAS, and ADMIDAS are shown in light yellow, light orange, and light brown CPKs, respectively. Color coding for conformational changes at the very end of the simulation (after 90% simulation time), including the movement of β1-α1 towards the MIDAS, α1 helix straightening, internal rearrangements of SDL, and final changes at the interfaces between the β3 βA (I-like) domain and either the hybrid or the α β-propeller domains, is omitted for clarity.

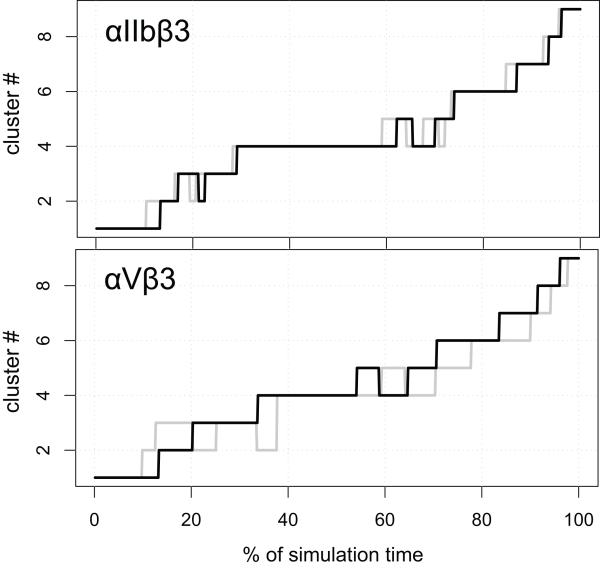

Figure 4. Dynamics of β3 Integrins in Cluster Space.

Conformational evolution of the integrin systems among the clusters defined by the contact matrix analysis of the RP-TMD simulations as a function of the elapsed fraction of simulation time. The upper and lower panels show the sequence of secondary structure changes in the β3 βA (I-like) domain of integrins αIIbβ3 and αVβ3, respectively, as defined by conformational clustering of their forward (unliganded-closed to liganded-open states; black line) and backward (liganded-open to unliganded-closed states; gray line) trajectories. To make the comparison easier, the curves corresponding to the backward simulations (gray color) have been reversed, so that the abscissa represents the fraction of time from the end of the simulation.

Timeline of Global Conformational Rearrangements

To follow the swing-out motion of the β3 hybrid domains of αIIb and αV integrins during transition from their unliganded-closed to liganded-open conformations, and vice versa, we calculated the RMSD to the target configuration during all 8 RP-TMD simulations of αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 integrins. Figure 2 shows the evolution of the distance from the TMD target calculated for αIIbβ3 (upper panel) and αVβ3 (lower panel), respectively, and each averaged over two simulations of either forward (from unliganded-closed to liganded-open conformations, black lines in Figure 2) or backward (from liganded-open to unliganded-closed conformations; gray lines in Figure 2) transitions. The swing-out motion of the β3 hybrid domains was also followed by the opening of the hinge angle50 between the β3 βA (I-like) and hybrid domains (see red lines and arrow in Figure 1) using the Wriggers and Schulten’s algorithm50 and each starting structure as reference (see Methods for more details). The average values of these hinge angles and their standard deviations calculated over two forward RP-TMD (black lines in Figure 2 insets) and two backward RP-TMD (gray lines in Figure 2 insets) simulations of αIIbβ3 or αVβ3 are represented as a function of simulation time in Figure 2 insets. The time evolution of the hinge angle values relative to the starting structure was very similar among the different runs and also when comparing αIIbβ3 with αVβ3.

Analysis of the time evolution of the per residue backbone RMSD of the β3 βA (I-like) domain from its initial conformation revealed the same global rearrangements of its secondary structure elements during the transition from the unliganded-closed to the liganded-open conformations, and vice versa. Figure 3 shows the subdomains in the βA (I-like) domain of αIIbβ3 integrin colored according to the order of significant conformational changes (per residue RMSD larger than 2 Å after optimal superposition of the backbone of all βA (I-like) domain atoms) from the starting conformation during dynamics. Tangible conformational changes within the β3 βA (I-like) domain started at the very beginning of the simulation (e.g., α6 movement, SDL rearrangement, and α1 bending; blue-cyan-green colors in Figure 3), but the most dramatic local rearrangements of the β3 βA (I-like) secondary structure elements that accompanied the swing-out motion of the hybrid domain (e.g., breaking of contact interactions between the β6α7 loop and the α1 helix N-terminus, α7 downward movement, and the opening of the β6α7 loop; yellow-orange-red colors in Figure 3) occurred only near the end (∼90% simulation time) of the trajectories from unliganded-closed to liganded-open αIIbβ3 integrin (Figure 3). These major changes were followed by the movement of the β1-α1 loop towards the MIDAS, which was accompanied by other subtle conformational changes (not shown in Figure 3), including α1 helix straightening, internal rearrangements of SDL, and final changes at the interfaces between the β3 βA (I-like) domain and either the hybrid or the α β-propeller domains. RP-TMD simulations of the αVβ3 system yielded a similar sequence of events (data not shown). An opposite order of events was registered during the RP-TMD simulations from liganded-open to unliganded-closed conformations (data not shown) of either integrin complex.

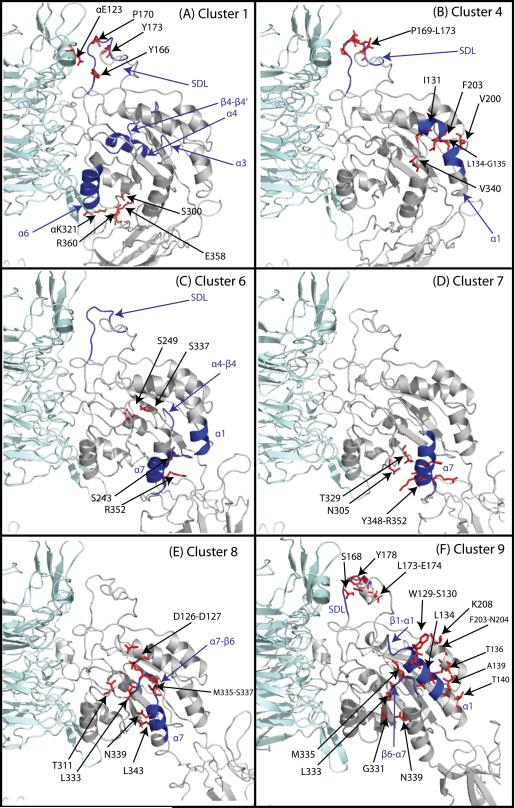

The upper panel of Figure 4 shows the sequence of secondary structure changes in the β3 βA (I-like) domain of integrin αIIbβ3, as defined by conformational clustering of its forward (unliganded-closed to liganded-open states) and backward (liganded-open to unliganded-closed states) RP-TMD trajectories. The system reached the conformation of cluster 1 (Figure 5A) very quickly, and remained in this cluster for approximately the first 10% of the simulation. When compared to the starting conformation, the centroid of this cluster shows some structural differences in the β3 βA (I-like) domain. These differences correspond to significant changes (2.5-4 Å) from their initial conformations in the α6 helix (residues V315-E323), part of the β4-β4′ loop (residues D270-D280), the α3 helix (residues G221-V231), and the α4 helix (residues D233-I236), as well as slight changes in the SDL loop (residues M165-N175). All these regions are colored in blue in Figure 5A. Of note, all but the latter change remained stable during most of the trajectories (until ∼80-85% simulation time).

Figure 5. Representative Conformations of the Most Relevant Clusters of Integrin αIIbβ3.

The most relevant clusters obtained by RP-TMD are defined as the clusters whose conformations show significant differences (RMSD > 4Å). The αIIb subunit is depicted in cyan, and the β3 subunit in gray. Some of the relevant residues involved in contact breaking and formation in the transitions from one cluster to the other are depicted as red sticks. The secondary structure motifs that show significant conformational differences among sequential clusters are depicted in blue. The numbers refer to the residue index in the β3 subunit, unless otherwise indicated.

The αIIbβ3 system left cluster 1 after ∼15% of the trajectory and rapidly populated clusters 2 and 3, exchanging frequently between the two. These two clusters are relatively small and conformationally similar to cluster 1 (data not shown). After approximately 22% simulation time, the system entered cluster 4 and remained in this cluster until approximately the 60% time mark. In this cluster, a distortion in the middle of the α1 helix (residues S130-T140) became evident (Figure 5B; blue color), as well as changes in the first segment of the specificity determining loop (SDL; residues M165-N175), including a 310 helix at residues P169-N175. After a long residence in cluster 4, the system rapidly switched to cluster 5 and back to cluster 4 for a time span of approximately 10% total simulation time. An analysis of cluster 5 shows that the conformational differences with cluster 4 are minimal (the RMSD between the centroids of the two clusters is 0.5 Å).

After such rapid fluctuations, the system evolved into cluster 6, where the changes (blue color in Figure 5C) in the α1 helix (especially its C-terminus, residues T140-L145) and SDL became more pronounced (4-5 Å deviation from initial conformation), and were accompanied by the movement of the α4-β4 loop (residues I236-S243). A small movement of the C-terminal portion of the α7 helix (residues Y348-S353) was also present in the centroid of this cluster. With the transition to cluster 7 (92% simulation time), such movement became much more pronounced (4-8 Å deviation from initial conformation), and propagated towards the N-terminal portion (residues S337-V345) of the α7 helix (Figure 5D). The opening of the β6-α7 loop (residues L333-D336) is the main difference in the representative conformation of cluster 8 (Figure 5E) with respect to the representative conformation of cluster 7. Shortly after the transition to cluster 8, and after a stay of approximately 5% total simulation time, the α1 helix straightens in cluster 9 (Figure 5F), where we also observe a movement of the β1-α1 loop towards the MIDAS, and a transition to a liganded-like conformation of the SDL domain (residues M165 to G189) by the end of the simulation. The conformation of all other βA (I-like) domain elements remained the same as in their initial structures throughout the entire simulation. Only minor differences in the residence times were observed in the two statistically independent forward runs of αIIbβ3 starting from the unliganded-closed conformation. The order with which the clusters were visited was essentially the same, the only differences being the number of rapid exchanges between clusters 2 and 3 at the beginning of the simulation and the short visits to cluster 5 at the end of the residence in cluster 4.

The reverse simulations of αIIbβ3 (gray line in the upper panel of Figure 4), starting from the liganded-open conformation and steering the system towards the unliganded-closed conformation, had very similar dynamics. We compared each cluster of the backward simulations of αIIbβ3 to each one of the forward simulations and found that a clear biunivocal mapping could be established between the two sets, except for the case of the very similar clusters 2 and 3. In each case, the total RMSD of the centroids of the corresponding clusters was less than 1.1 Å, and the next cluster lied at more than 2.4 Å away. Thus, we numbered the clusters of the reverse simulations using the numbers of their corresponding clusters in the forward simulations, and verified that the sequence of events was completely reversed.

The same type of analysis was performed for the αVβ3 system (Figure 4, lower panel). Again, the clusters obtained using the αVβ3 forward trajectory could be placed into a biunivocal relationship to those identified previously for the αIIbβ3 system. Specifically, RMSD analysis showed that pairs of corresponding clusters in αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 differed no more than 2.8 Å, with the next closest cluster lying beyond 3.5 Å. A similar overall pattern of conformational changes of the β3 βA (I-like) elements was found when analyzing the conformational clusters of αVβ3. However, a few minor exceptions were identified by analyzing the differences in the pairs of corresponding clusters in αIIbβ3 and αVβ3. In all clusters, starting from cluster 1, the αVβ3 system showed less pronounced movements of the α6 helix (residues V315-E323, located at the interface between α and β subunits), the α3 helix (residues G221-V231), the α4 helix (residues D233-I236), and the β4-β4′ loop (residues D270-H280). The differences in these regions accounted for almost the 80% of the RMSD between the αVβ3 and the αIIbβ3 systems. While the order of the events is the same, slight variations also occur in the residence time in some of the clusters (see Figure 4). Notably, the long residence of the αIIbβ3 system in cluster 4 is not observed in the αVβ3 case, and the transition to cluster 6 occurs earlier (at about 40% simulation time).

Timeline of Inter-Residue Interaction Changes

Analysis of the TMD simulations allowed us to characterize the integrin αIIβ3 or αVβ3 stochastic pathway(s) of the swing-out movement of the β3 hybrid domain between the unliganded-closed low affinity and the liganded-open high affinity states of the two β3 integrins in terms of changes in specific intra-domain and inter-domain contacts. Specifically, we analyzed the differences of the contact matrices between the centroids of the clusters identified and described in the previous section in order to dissect the effect of forming and breaking contacts on the conformational dynamics of β3 integrins during swing-out of their hybrid domains. Forming contacts were defined as inter-molecular interactions formed by residue side-chains that had centers of geometry within a 6.5 Å distance. At variance with the clustering procedure, where only the contact maps of residues within the βA (I-like) domain were considered when defining the dissimilarity used to generate the clusters, we also considered the contacts formed between the βA (I-like) domain and other domains of the β3 integrin proteins (in particular the α subunit β-propeller regions close to the interface). Specifically, given the sequential nature of the clusters described in the previous section, we compared each cluster with the preceding one in order to capture the differences in specific contacts along the trajectory.

Four main conclusions derive from analysis of inter-residue interactions: 1) The contact rearrangements that occurred upon swing-out of the hybrid domain from the unliganded-closed to the liganded-open conformation were common to both αIIβ3 and αVβ3 integrins and followed similar timelines. Major differences were observed at the interfaces between the α propellers and the β subunits, especially in the hybrid domain at the beginning of the transition, and in the SDL at the end of the simulation. Of note, with the exception of a few residues that were different between αIIb and αV — most notably those in the β2-β3 insert of the W2 blade of the β-propeller (residues W110-T125 in αIIb and L111-E123 in αV) making contacts with the SDL loop — the majority of residues involved in interactions are highly conserved among different species (data not shown). 2) With the exception of some contact breaking at the very beginning of the simulation, contact changes during the simulations followed a clear sequence of events. These events originated at the interfaces between the hybrid domain and both the insert loop between the β2 and β3 strands of the W5 blade loop (β-ribbon) in the α-subunit β-propeller domain and the α6 helix in the βA (I-like) domain (see Figure 3), and continued with the rearrangement of the interface between the hybrid and βA (I-like) domains. This rearrangement preceded changes within the C-terminal region of the α7 helix, which were transduced to the β6-α7 loop and produced separation of this loop from the ADMIDAS ion. Breaking of the interaction between the β6-α7 loop and the N-terminal region of the α1 helix was accompanied by the straightening of that helix, a conformational change of the SDL, and the movement of the β1-α1 loop towards the MIDAS. The transition terminated with a rearrangement of the new interface between the hybrid and βA (I-like) domains, and changes at the interface between the SDL and the β-propeller. 3) There were more breaking than forming contacts during unliganded-closed-to-liganded-open transition, and almost all of the forming contacts occurred at the end of the simulations; 4) The downward and lateral movement of the α7 helix and the opening of the β6-α7 loop primarily reflected contact breaking, whereas straightening of α1 was associated with new contact formation.

A detailed analysis of the specific differences between the clusters follows.

a) Differences between the starting conformation and conformations in cluster 1 (Figure 5A)

A few contacts of the unliganded-closed forms of αIIbβ3 and/or αVβ3 broke at the very beginning of the simulations and are not present in the centroid conformation of cluster 1. These contacts, which involve regions at the interface between the two subunits of the protein, are: 1) the αIIb E123- β3 P170 contact, between the W2β2-W2β3 insert of the β-propeller domain and the first segment of the SDL, which is closer to the αIIb-β3 interface; 2) In the case of the αIIbβ3 system, the Y166-Y173 contact within the first segment of the SDL is lost in cluster 1, whereas the same contact is present in all the clusters up to cluster 6 in the αVβ3 system; 3) the αIIb K321-β3 E358 salt bridge and the αIIb S300-β3 R360 hydrogen bond between the αIIb β-propeller and the β3 hybrid domain.

b) Differences between conformations of cluster 1 and cluster 4 (Figure 5B)

In the conformations of cluster 4, breaking of contacts between the α1 helix and its neighboring residues induces a distortion in the middle of the α1 helix. Specifically contacts of the α1 helix with α7 helix residues (I131-V340) and α2 helix residues (L134-F203, G135-V200) are broken in conformations of cluster 4. Also observed in conformations of this cluster are changes in the first segment of the SDL, with the formation of a 310 helix (P169-L173).

c) Differences between conformations of cluster 4 and cluster 6 (Figure 5C)

The main contacts lost in the conformations of cluster 6 with respect to the conformations of cluster 4 are contacts between the β4 strand and the α7 helix (S243-R352) and between the β4 and α7 helices (S249-S337). These contacts loosen the position of the α7 helix, and initiate the conformational changes evident in the following cluster.

d) Differences between cluster 6 and cluster 7 (Figure 5D)

The main difference between structures in cluster 7 is the loss of interactions involving the C-terminal region of the α7 helix (S337-R352). In both the αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 simulations, contacts between α7 and β6 (T329-K350), or the α5-β5 loop (N305-I351) or within the α7 helix itself (Y348-R352) are also lost. As a result of the loss of such contacts, the α7 helix undergoes a downward and lateral movement.

e) Differences between conformations of cluster 7 and cluster 8 (Figure 5E)

The downward motion of α7 helix most likely induces the changes in the βA (I-like) β6-α7 loop observed in cluster 8, with breaking of most hydrophobic contacts between this loop and the N-termini of both the α7 and α1 helices. These changes allowed the opening of the β6-α7 loop and the upward movement of the α1 helix to accommodate the changes that occurred at its boundaries (N-terminal close to MIDAS and ADMIDAS, and C-terminal close to the hybrid domain). Within the β6-α7 loop, L333 broke contacts with the α7 helix residues L343, N339, and S337. In the α1 helix, the ADMIDAS coordinating side-chains D126 and D127 were separated from the loop residue D336, and the hydrogen bond between residues D127 and S337 in the β6-α7 loop is also lost. Finally, opening of the β6-α7 loop was accompanied by breaking of the interaction between T311 (within the β5-α6 loop) and the M335 side-chains as it loses its coordination with the ADMIDAS.

f) Differences between conformations of cluster 8 and cluster 9 (Figure 5F)

In cluster 9, a kink between the 310-helix in the β1-α1 loop (residues L120-D126) and the α1-helix (residues D127-L145) disappeared, resulting in the straightening of the α1-helix as it pivoted laterally and filled in space vacated by the β6-α7 loop. The straightening of the α1 helix was associated with the formation of new contacts between the α1 helix and the β6-α7 loop (S130-M335, S130-L333, L134-L333, and W129-M335), between the α1 and α2 helices (A139-F203, T140-N204, T136-K208), and between the β6 strand and the α7 helix (G331-N339). Also in cluster 9, the SDL domain undergoes conformational changes in the turn that separates the two SDL segments (residues V157-N175 and P176-G189), which implies breaking of β3 S168-E174 and L173-Y178 interactions.

DISCUSSION

Experimental34,51,52 and computational53-55 studies of integrin receptor I domains have supported a role for the movement of the α7 helix in attaining the high affinity ligand binding state. Moreover, liganded and unliganded structures for both high and intermediate-affinity mutant I domains helped reveal atomic details of the conformational change induced by ligand binding.52 In β3 integrins, which lack an I domain, a similar movement of the α7 helix in the β3 βA (I-like) domain has been implicated in attaining a high affinity state.20,32-36. However, there are no intermediate structures reported for the βA (I-like) domain and only structural information from the unliganded and liganded β3 is available. 16-21 Since β3 βA (I-like) domains differ from I domains in having three metal ions instead of just one and in the linkage of the movement of the α7 helix with a dramatic swing-out motion of the β3 hybrid domain, it is not clear to what extent one can extrapolate from studies of I domains to the β3 βA (I-like) domains of αIIbβ3 and αVβ3. Thus, the precise sequence of events during the conformational transitions of β3 integrins from low-affinity to high-affinity states remains unclear.

To obtain an atomic-level stochastic description of the allosteric transitions from unliganded-closed to liganded-open states of the headpieces of αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 integrins in an explicit solvent, with the ultimate goal of identifying the molecular determinants responsible for these transitions, we have carried out TMD simulations of each β3 integrin system. Specifically, multiple simulations from unliganded-closed to liganded-open conformations in the presence of only one metal ion (ADMIDAS) were performed using the standard TMD algorithm. These simulations produced similar results, supporting the robustness of the proposed transition pathways. However, not surprisingly given the known limitations of the TMD method40, these simulations did not show a complete reversibility of the transition pathways when steering the system in the opposite direction from the liganded-open to unliganded-closed conformations. Thus, we applied the RP-TMD method to assess the reversibility of transition pathways between unliganded-closed and liganded-open conformations of αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 integrins, and the robustness of the results under different simulation mechanisms. Moreover, since the TMD and RP-TMD simulations were carried out with different choices for the ion occupation of the metal binding sites (only ADMIDAS for standard TMD simulations but all three LIMBS, MIDAS and ADMIDAS for RP-TMD simulations), we checked for consistency of the results in the presence or absence of LIMBS and MIDAS metal ions.

Notably, the standard TMD and the RP-TMD methods applied to truncated forms of αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 integrins yield similar results, suggesting that the data reflect the sequence of events that best describes the conformational plasticity associated with the hybrid domain swing-out of β3 integrin proteins in terms of specific inter-subunit interaction changes. Our results point to specific major conformational changes in β3 integrins during swing-out of their hybrid domains that are in line with previous experimental and computational data. Specifically, we observe the following sequence of major conformational changes: 1) Breaking of the α subunit β propeller βA- hybrid interface near the β-ribbon (cluster 1); 2) α7 helix downward deflection (cluster 7); 3) Movement of the β6-α7 loop away from the ADMIDAS metal ion (cluster 8), which results in the loss of the coordination of this ion by the carbonyl oxygen of β6-α7 loop M335, one of the hallmarks of the liganded forms of both αIIbβ3 and αVβ3;20 and 4) Concomitant α1 helix straightening and β1-α1 loop movement towards the MIDAS (cluster 9). Less dramatic conformational changes correspond to: 1) The transient deformation of the α6, α4, and α3 helices and the β4-β4′ loop (cluster 1); 2) Transient distortion of the α1 helix (cluster 4) and α4-β4 loop (cluster 6); and 3) Both early and late changes in the SDL (in clusters 4, 6, and 9).

We do not identify significant differences in the dynamics of the αIIβ3 and αVβ3 headpieces, i.e. structural changes, rates of hinge angle opening and contact rearrangements are similar in the simulations of αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 integrins, both in nature and timeline. Since our simulations are conducted in the absence of ligand, it is possible that functional differences between these receptors are due to specific signal- and/or ligand-induced conformational plasticity. Almost all of the subtle differences that we identify between these two cognate proteins are primarily related to differences at the interface between the α subunit β propeller loops and both the hybrid domain and the SDL. Based on structural comparison between the recent crystal structure of the αIIbβ3 low-affinity state (PDBID: 3FCU) and the crystal structure of unliganded-closed αVβ3 (PDBID:1U18) that served as a template for homology modeling of the unliganded-closed conformation of αIIbβ3, these differences may be attributed to non-conserved residues at the interface of the α subunit. Our simulations suggest specific interacting residues whose mutations can help explore the role of the interaction between the β-ribbon of the α-subunit and the SDL in swing-out of the hybrid domain, and in functional differences between αIIβ3 and αVβ3 integrins. Specifically, these residues and contacts are: αIIb E123-β3 P170, β3 Y166- β3 L173, αIIb E121-β3 P170, αV Q120-β3 P170, αIIb E121-β3 S168, and αV Q120-β3 S168. For instance, the impact of early contact breaking at these positions on hybrid domain swing-out may be tested by replacing these residues by cysteines and selectively limiting swing-out by introducing new disulfides.

Results of our TMD studies also point to specific contacts whose mutation is expected to interfere with the normal swing-out of the β3 hybrid domain, including those made by: 1) Three continuous charged residues in the very long αIIb β-ribbon that contact three oppositely charged residues in the β3 hybrid. Specifically, these contacts are αIIb D319-β3 K384, αIIb R320-β3 E356, and αIIb K321-β3 E358. The first and third pairs are conserved in αVβ3 (αV D306-β3 K384 and αV K308-β3 E358), whereas in the latter the αIIb R320 residue is replaced by a glycine in αV (G307).9,56-60 2) β3 S300 (α5 helix) and β3 R360 (hybrid domain),32 whose Cβ distance increases from ∼9 to ∼34 Å; 3) Residues G349-R352 of the C-terminal region of α7 helix that contacts the hybrid domain;33-36 4) Residues S337-N339 and D126-S130 of the N-terminal portions of the α7 helix61,62 and the α1 helix,36,63-67 respectively, whose interactions are lost when the β6-α7 loop moves away from the ADMIDAS ion. Selective modification of these residues may provide valuable information on the role of these residues in attaining the high affinity ligand binding state. For instance, mutations of hydrophobic interacting residues to polar/charged residues may be introduced to suppress contact formation. Similarly, the role of salt bridges/hydrogen bonds in stabilizing particular intermediate states of the protein complexes may be evaluated by replacing the specific polar residues involved in these interactions by alanines.

Finally, in both systems, we observe that the global RMSD decrease towards the target occurs more slowly during the first half of the simulation, and then, after the interactions between the α subunit β-propeller β-ribbon and the β3 subunit break, it decreases more rapidly. This suggests that releasing the restraints imposed by the contacts that were broken during the early time points facilitates the later conformational changes and thus it may partially explain the multistep mechanism observed for ligand binding to integrins, which has been supported by several biophysical techniques.37,68-74 In this model, ligand binding to β3 integrins follows a self priming mechanism in which initial ligand interaction with the RGD site results in changes in the receptor and the ligand that produce higher affinity binding, with perhaps multiple intermediate affinity states, and additional sites of interaction between ligand and receptor.37,68

Supplementary Material

Energy in a Representative RP-TMD Run of Integrin αIIbβ3. The total potential energy of the protein (upper panel) and the protein-solvent interaction term (lower panel) in the first forward run for the αIIbβ3 system.

Energy in a Representative RP-TMD Run of Integrin αVβ3. The total potential energy of the protein (upper panel) and the protein-solvent interaction term (lower panel) in the first forward run for the αVβ3 system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Drs. Jianpeng Ma and Liskin Swint-Kruse for help at the time of setting up the standard TMD simulations, and Dr. Eileen Puklin-Faucher for providing the script for the hinge angle measurement. This work was supported in part by grants HL19278 and UL1RR024143 from the NIH and funds from Stony Brook University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shattil SJ, Newman PJ. Integrins: dynamic scaffolds for adhesion and signaling in platelets. Blood. 2004;104(6):1606–1615. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byzova TV, Rabbani R, D’Souza SE, Plow EF. Role of integrin alpha(v)beta3 in vascular biology. Thromb Haemost. 1998;80(5):726–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzgerald LA, Poncz M, Steiner B, Rall SC, Jr., Bennett JS, Phillips DR. Comparison of cDNA-derived protein sequences of the human fibronectin and vitronectin receptor alpha-subunits and platelet glycoprotein IIb. Biochemistry. 1987;26(25):8158–8165. doi: 10.1021/bi00399a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blue R, Murcia M, Karan C, Jirouskova M, Coller BS. Application of high-throughput screening to identify a novel alphaIIb-specific small- molecule inhibitor of alphaIIbbeta3-mediated platelet interaction with fibrinogen. Blood. 2008;111(3):1248–1256. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-105544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JW, Ruggeri ZM, Kunicki TJ, Cheresh DA. Interaction of integrins alpha v beta 3 and glycoprotein IIb-IIIa with fibrinogen. Differential peptide recognition accounts for distinct binding sites. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(21):12267–12271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheresh DA, Berliner SA, Vicente V, Ruggeri ZM. Recognition of distinct adhesive sites on fibrinogen by related integrins on platelets and endothelial cells. Cell. 1989;58(5):945–953. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90946-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith JW, Piotrowicz RS, Mathis D. A mechanism for divalent cation regulation of beta 3-integrins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(2):960–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan B, Hu DD, Knowles SK, Smith JW. Probing chemical and conformational differences in the resting and active conformers of platelet integrin alpha(IIb)beta(3) J Biol Chem. 2000;275(10):7249–7260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takagi J, Petre BM, Walz T, Springer TA. Global conformational rearrangements in integrin extracellular domains in outside-in and inside-out signaling. Cell. 2002;110(5):599–511. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00935-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahrens IG, Moran N, Aylward K, Meade G, Moser M, Assefa D, Fitzgerald DJ, Bode C, Peter K. Evidence for a differential functional regulation of the two beta(3)-integrins alpha(V)beta(3) and alpha(IIb)beta(3) Exp Cell Res. 2006;312(6):925–937. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110(6):673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humphries MJ, Travis MA, Clark K, Mould AP. Mechanisms of integration of cells and extracellular matrices by integrins. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32(Pt 5):822–825. doi: 10.1042/BST0320822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qin J, Vinogradova O, Plow EF. Integrin bidirectional signaling: a molecular view. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(6):e169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo BH, Carman CV, Springer TA. Structural basis of integrin regulation and signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:619–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou Z, Chen H, Schmaier AA, Hynes RO, Kahn ML. Structure-function analysis reveals discrete beta3 integrin inside-out and outside-in signaling pathways in platelets. Blood. 2007;109(8):3284–3290. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiong JP, Stehle T, Diefenbach B, Zhang R, Dunker R, Scott DL, Joachimiak A, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin alpha Vbeta3. Science. 2001;294(5541):339–345. doi: 10.1126/science.1064535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiong JP, Stehle T, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, Frech M, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin alpha Vbeta3 in complex with an Arg-Gly-Asp ligand. Science. 2002;296(5565):151–155. doi: 10.1126/science.1069040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiong JP, Stehle T, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. A novel adaptation of the integrin PSI domain revealed from its crystal structure. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(39):40252–40254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu J, Luo BH, Xiao T, Zhang C, Nishida N, Springer TA. Structure of a complete integrin ectodomain in a physiologic resting state and activation and deactivation by applied forces. Mol Cell. 2008;32(6):849–861. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao T, Takagi J, Coller BS, Wang JH, Springer TA. Structural basis for allostery in integrins and binding to fibrinogen-mimetic therapeutics. Nature. 2004;432(7013):59–67. doi: 10.1038/nature02976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Springer TA, Zhu J, Xiao T. Structural basis for distinctive recognition of fibrinogen gammaC peptide by the platelet integrin alphaIIbbeta3. J Cell Biol. 2008;182(4):791–800. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du X, Gu M, Weisel JW, Nagaswami C, Bennett JS, Bowditch R, Ginsberg MH. Long range propagation of conformational changes in integrin alpha IIb beta 3. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(31):23087–23092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weisel JW, Nagaswami C, Vilaire G, Bennett JS. Examination of the platelet membrane glycoprotein IIb-IIIa complex and its interaction with fibrinogen and other ligands by electron microscopy. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(23):16637–16643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Litvinov RI, Nagaswami C, Vilaire G, Shuman H, Bennett JS, Weisel JW. Functional and structural correlations of individual alphaIIbbeta3 molecules. Blood. 2004;104(13):3979–3985. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwasaki K, Mitsuoka K, Fujiyoshi Y, Fujisawa Y, Kikuchi M, Sekiguchi K, Yamada T. Electron tomography reveals diverse conformations of integrin alphaIIbbeta3 in the active state. J Struct Biol. 2005;150(3):259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiong JP, Stehle T, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. New insights into the structural basis of integrin activation. Blood. 2003;102(4):1155–1159. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adair BD, Xiong JP, Maddock C, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA, Yeager M. Three-dimensional EM structure of the ectodomain of integrin {alpha}V{beta}3 in a complex with fibronectin. J Cell Biol. 2005;168(7):1109–1118. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200410068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coutinho A, Garcia C, Gonzalez-Rodriguez J, Lillo MP. Conformational changes in human integrin alphaIIbbeta3 after platelet activation, monitored by FRET. Biophys Chem. 2007;130(1-2):76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye F, Liu J, Winkler H, Taylor KA. Integrin alpha IIb beta 3 in a membrane environment remains the same height after Mn2+ activation when observed by cryoelectron tomography. J Mol Biol. 2008;378(5):976–986. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumoto A, Kamata T, Takagi J, Iwasaki K, Yura K. Key interactions in integrin ectodomain responsible for global conformational change detected by elastic network normal mode analysis. Biophys J. 2008 doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.131045. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rocco M, Rosano C, Weisel JW, Horita DA, Hantgan RR. Integrin conformational regulation: uncoupling extension/tail separation from changes in the head region by a multiresolution approach. Structure. 2008;16(6):954–964. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo BH, Springer TA, Takagi J. Stabilizing the open conformation of the integrin headpiece with a glycan wedge increases affinity for ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(5):2403–2408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0438060100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo BH, Takagi J, Springer TA. Locking the beta3 integrin I-like domain into high and low affinity conformations with disulfides. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(11):10215–10221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang W, Shimaoka M, Chen J, Springer TA. Activation of integrin beta-subunit I-like domains by one-turn C-terminal alpha-helix deletions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(8):2333–2338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307291101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mould AP, Barton SJ, Askari JA, McEwan PA, Buckley PA, Craig SE, Humphries MJ. Conformational changes in the integrin beta A domain provide a mechanism for signal transduction via hybrid domain movement. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(19):17028–17035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213139200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barton SJ, Travis MA, Askari JA, Buckley PA, Craig SE, Humphries MJ, Mould AP. Novel activating and inactivating mutations in the integrin beta1 subunit A domain. Biochem J. 2004;380(Pt 2):401–407. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puklin-Faucher E, Gao M, Schulten K, Vogel V. How the headpiece hinge angle is opened: New insights into the dynamics of integrin activation. J Cell Biol. 2006;175(2):349–360. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200602071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schlitter J, Engels M, Kruger P, Jacoby E, Wollmer A. Targeted molecular dynamics simulation of conformational change: application to the T↔R transition in insulin. Mol simul. 1993;10(2-6):291–308. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schlitter J, Engels M, Kruger P. Targeted molecular dynamics: a new approach for searching pathways of conformational transitions. J Mol Graph. 1994;12(2):84–89. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(94)80072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Vaart A, Karplus M. Simulation of conformational transitions by the restricted perturbation-targeted molecular dynamics method. J Chem Phys. 2005;122(11):114903. doi: 10.1063/1.1861885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. CHARMM: A program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. J Comput Chem. 1983;4(2):187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Palo Alto, CA, USA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14(1):33–38. 27–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fiser A, Sali A. Modeller: generation and refinement of homology-based protein structure models. Methods Enzymol. 2003;374:461–491. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mitchell WB, Li J, Murcia M, Valentin N, Newman PJ, Coller BS. Mapping early conformational changes in alphaIIb and beta3 during biogenesis reveals a potential mechanism for alphaIIbbeta3 adopting its bent conformation. Blood. 2007;109(9):3725–3732. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-058420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flynn TC, Swint-Kruse L, Kong Y, Booth C, Matthews KS, Ma J. Allosteric transition pathways in the lactose repressor protein core domains: asymmetric motions in a homodimer. Protein Sci. 2003;12(11):2523–2541. doi: 10.1110/ps.03188303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ciccotti G, Berendsen J. Numerical integration of the Cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J Comput Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, von Gunsteren WF, DiNola A, Haak JR. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J Chem Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grant BJ, Rodrigues AP, ElSawy KM, McCammon JA, Caves LS. Bio3d: an R package for the comparative analysis of protein structures. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(21):2695–2696. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wriggers W, Schulten K. Protein domain movements: detection of rigid domains and visualization of hinges in comparisons of atomic coordinates. Proteins. 1997;29(1):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimaoka M, Lu C, Salas A, Xiao T, Takagi J, Springer TA. Stabilizing the integrin alpha M inserted domain in alternative conformations with a range of engineered disulfide bonds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(26):16737–16741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252633099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shimaoka M, Xiao T, Liu JH, Yang Y, Dong Y, Jun CD, McCormack A, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, Takagi J, Wang JH, Springer TA. Structures of the alpha L I domain and its complex with ICAM-1 reveal a shape-shifting pathway for integrin regulation. Cell. 2003;112(1):99–111. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01257-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jin M, Andricioaei I, Springer TA. Conversion between three conformational states of integrin I domains with a C-terminal pull spring studied with molecular dynamics. Structure. 2004;12(12):2137–2147. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nam K, Maiorov V, Feuston B, Kearsley S. Dynamic control of allosteric antagonism of leukocyte function antigen-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 interaction. Proteins. 2006;64(2):376–384. doi: 10.1002/prot.20999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gaillard T, Martin E, San Sebastian E, Cossio FP, Lopez X, Dejaegere A, Stote RH. Comparative normal mode analysis of LFA-1 integrin I-domains. J Mol Biol. 2007;374(1):231–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Derrick JM, Loudon RG, Gartner TK. Peptide LSARLAF activates alpha(IIb)beta3 on resting platelets and causes resting platelet aggregate formation without platelet shape change. Thromb Res. 1998;89(1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(97)00289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Derrick JM, Taylor DB, Loudon RG, Gartner TK. The peptide LSARLAF causes platelet secretion and aggregation by directly activating the integrin alphaIIbbeta3. Biochem J. 1997;325(Pt 2):309–313. doi: 10.1042/bj3250309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Derrick JM, Shattil SJ, Poncz M, Gruppo RA, Gartner TK. Distinct domains of alphaIIbbeta3 support different aspects of outside-in signal transduction and platelet activation induced by LSARLAF, an alphaIIbbeta3 interacting peptide. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86(3):894–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mitsios JV, Tambaki AP, Abatzis M, Biris N, Sakarellos-Daitsiotis M, Sakarellos C, Soteriadou K, Goudevenos J, Elisaf M, Tsoukatos D, Tsikaris V, Tselepis AD. Effect of synthetic peptides corresponding to residues 313-332 of the alphaIIb subunit on platelet activation and fibrinogen binding to alphaIIbbeta3. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271(4):855–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.03990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mitsios JV, Stamos G, Rodis FI, Tsironis LD, Stanica MR, Sakarellos C, Tsoukatos D, Tsikaris V, Tselepis AD. Investigation of the role of adjacent amino acids to the 313-320 sequence of the alphaIIb subunit on platelet activation and fibrinogen binding to alphaIIbbeta3. Platelets. 2006;17(5):277–282. doi: 10.1080/09537100500436713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hato T, Yamanouchi J, Yakushijin Y, Sakai I, Yasukawa M. Identification of critical residues for regulation of integrin activation in the beta6-alpha7 loop of the integrin beta3 I-like domain. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(10):2278–2280. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cheng M, Foo SY, Shi ML, Tang RH, Kong LS, Law SK, Tan SM. Mutation of a conserved asparagine in the I-like domain promotes constitutively active integrins alphaLbeta2 and alphaIIbbeta3. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(25):18225–18232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701386200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bajt ML, Ginsberg MH, Frelinger AL, 3rd, Berndt MC, Loftus JC. A spontaneous mutation of integrin alpha IIb beta 3 (platelet glycoprotein IIb-IIIa) helps define a ligand binding site. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(6):3789–3794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bajt ML, Loftus JC. Mutation of a ligand binding domain of beta 3 integrin. Integral role of oxygenated residues in alpha IIb beta 3 (GPIIb-IIIa) receptor function. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(33):20913–20919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mould AP, Askari JA, Barton S, Kline AD, McEwan PA, Craig SE, Humphries MJ. Integrin activation involves a conformational change in the alpha 1 helix of the beta subunit A-domain. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(22):19800–19805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201571200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mould AP, Barton SJ, Askari JA, Craig SE, Humphries MJ. Role of ADMIDAS cation-binding site in ligand recognition by integrin alpha 5 beta 1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(51):51622–51629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pesho MM, Bledzka K, Michalec L, Cierniewski CS, Plow EF. The specificity and function of the metal-binding sites in the integrin beta3 A-domain. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(32):23034–23041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Parise LV, Steiner B, Nannizzi L, Criss AB, Phillips DR. Evidence for novel binding sites on the platelet glycoprotein IIb and IIIa subunits and immobilized fibrinogen. Biochem J. 1993;289(Pt 2):445–451. doi: 10.1042/bj2890445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Muller B, Zerwes HG, Tangemann K, Peter J, Engel J. Two-step binding mechanism of fibrinogen to alpha IIb beta 3 integrin reconstituted into planar lipid bilayers. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(9):6800–6808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huber W, Hurst J, Schlatter D, Barner R, Hubscher J, Kouns WC, Steiner B. Determination of kinetic constants for the interaction between the platelet glycoprotein IIb-IIIa and fibrinogen by means of surface plasmon resonance. Eur J Biochem. 1995;227(3):647–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bednar B, Cunningham ME, McQueney PA, Egbertson MS, Askew BC, Bednar RA, Hartman GD, Gould RJ. Flow cytometric measurement of kinetic and equilibrium binding parameters of arginine-glycine-aspartic acid ligands in binding to glycoprotein IIb/IIIa on platelets. Cytometry. 1997;28(1):58–65. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19970501)28:1<58::aid-cyto7>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Litvinov RI, Bennett JS, Weisel JW, Shuman H. Multi-step fibrinogen binding to the integrin (alpha)IIb(beta)3 detected using force spectroscopy. Biophys J. 2005;89(4):2824–2834. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.061887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goldsmith HL, McIntosh FA, Shahin J, Frojmovic MM. Time and force dependence of the rupture of glycoprotein IIb-IIIa-fibrinogen bonds between latex spheres. Biophys J. 2000;78(3):1195–1206. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76677-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hsieh CF, Chang BJ, Pai CH, Chen HY, Tsai JW, Yi YH, Chiang YT, Wang DW, Chi S, Hsu L, Lin CH. Stepped changes of monovalent ligand-binding force during ligand-induced clustering of integrin alphaIIB beta3. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(35):25466–25474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Energy in a Representative RP-TMD Run of Integrin αIIbβ3. The total potential energy of the protein (upper panel) and the protein-solvent interaction term (lower panel) in the first forward run for the αIIbβ3 system.

Energy in a Representative RP-TMD Run of Integrin αVβ3. The total potential energy of the protein (upper panel) and the protein-solvent interaction term (lower panel) in the first forward run for the αVβ3 system.