Abstract

Recently developed serotypes of recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors have significantly enhanced the use of rAAV vectors for gene therapy. However, host immune responses to the transgene products from different serotypes remain uncharacterized. In the present study, we evaluated the differential immune responses to the transgene products from rAAV1 and rAAV8 vectors. In non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice, which have a hypersensitive immunity, rAAV serotype 1 vector (rAAV1-hAAT) induced high levels of both humoral and cellular responses, while rAAV8-hAAT did not. In vitro studies showed that rAAV1, but not rAAV8 vector transduced dendritic cells (DCs) efficiently. In vivo studies indicated that vector transduction of DCs was essential for the immune responses; while the presence of a transgene product (or foreign gene product produced by host cells) was not immunogenic. Intriguingly, preimmunization with rAAV8-hAAT vector or with serum of hAAT transgenic NOD mouse induced immune tolerance to rAAV1-hAAT injection. These results demonstrate the immunogenic differences of rAAV1 and rAAV8 and imply tremendous potential for these vectors in different applications, where an immune response to transgene is to be either elicited or avoided.

Keywords: DC activation, rAAV vectors

Recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors (rAAVs) have been widely used for gene therapy in animal models and in human clinical trials. There are several features that make rAAV vectors attractive for gene delivery, including longer-term sustained transgene expression, relatively low genotoxicity, and wide tropism of infection. While recently developed self complementary rAAV vectors, new serotypes of rAAV vectors, and chimeric rAAV vectors have greatly enhanced the use of rAAV vectors (1, 2), they open more opportunities and challenges in understanding the general biology of AAV. To date, more than 10 serotypes of rAAV vectors have been used. However, the immunogenic potential of these vectors remain elusive.

The immune response to transgene products is a critical issue for successful gene therapy (3, 4). While immune responses to a virally delivered antigen are highly desired for a DNA vaccine, immunogenicity may be a hurdle in gene replacement therapy for treatment of genetic diseases such as hemophilia or AAT deficiency. It has been reported that the rAAV2 vector is less immunogenic compared to the adenovirus vector (5). Recent studies show some rAAV vectors including serotypes 1, 2, and 5 can transduce dendritic cells (DCs) and generate immune responses to transgene products (6–9). Some studies have shown that rAAV8 vector has a low immunogenicity while it transduces liver, muscle, and many other cell types with high efficiency (10–15). The work done by Vandenberghe and colleagues suggests that this is due to the inability of transduction of DCs (8). It is clear that different serotypes of AAV vector induce different immune responses to the transgenes they deliver. However, the mechanisms underlying the immunogenicity or immunotolerance from these vectors are not fully understood. In this study, we investigated the distinct immune responses to transgene products in a hypersensitive autoimmune mouse model.

Results

rAAV1 and rAAV8 Vectors Mediated Distinct Immune Responses to Transgene Products in NOD Mice.

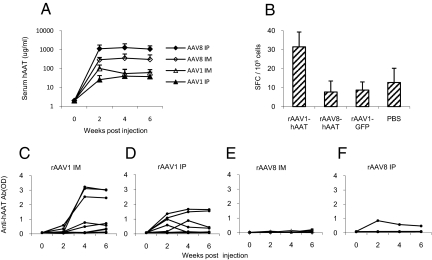

The NOD mouse is a commonly used autoimmune disease model that also displays hypersensitivity to foreign antigen (16). To investigate the immunogenicity of rAAV vectors, cohorts of NOD mice (n = 10) were intraperitoneally (IP) or intramuscularly (IM) injected with rAAV1-hAAT or rAAV8-hAAT vectors (2 × 1011 particles/mouse). Both vectors mediated high levels of transgene (hAAT) expression. The serum hAAT levels in the rAAV8-hAAT injected groups were higher than those in rAAV1-hAAT groups (Fig. 1A). Intriguingly, only one mouse in the rAAV8-hAAT injected group developed a detectable, although low, level of anti-hAAT antibodies, while more than 70% of the rAAV1-hAAT injected mice developed high or moderate levels of antibody against hAAT (Fig. 1 C–F). ELISpot analyses using splenocytes showed that rAAV1 injected mice developed a strong hAAT specific T-cell response, while rAAV8 and control groups did not (Fig. 1B). These results indicate that an immune response to the transgene product may be obtained using an rAAV1 vector or be avoided using an rAAV8 vector.

Fig. 1.

Human AAT expression and immune responses to hAAT in NOD mice injected with rAAV1-hAAT or rAAV8-hAAT. AAV1-CB-hAAT, AAV8-CB-hAAT, and AAV1-CB-GFP (2 × 1011 gv/mouse) were injected into 4-week-old NOD mice by IP injection or IM injection. Serum hAAT and anti-hAAT antibody levels were detected by ELISA. Cellular immune response was measured by IFN-γ ELISpot assay. (A) Serum hAAT levels in NOD mice (n = 10 in each group). Each line represents the average levels of each group. Filed diamond (AAV8 ip): IP injected with rAAV8-CB-hAAT; open diamond (AAV8 im): IM injected with rAAV8-CB-hAAT; filed triangle (AAV1ip): IP injected with rAAV1-CB-hAAT; open triangle (AAV1 im): IM injected with rAAV1-CB-hAAT. (B) IFN-γ ELISPOT assay using splenocytes from treatment and control groups (n = 3 in each group). The number of spot-forming cells (SFC) per 105 spleen cells is shown in the y axis. (C–F) Anti-hAAT antibody levels in rAAV1-hAAT (IM)-injected group (C), in rAAV1-hAAT (IP)-injected group (D), rAAV8-hAAT (IM)-injection group (E) and in rAAV8-hAAT (IP)-injection group (F). In C–F, each line shows the antibody levels in an individual animal (n = 10).

rAAV1, but Not rAAV8, Transduces DCs Efficiently.

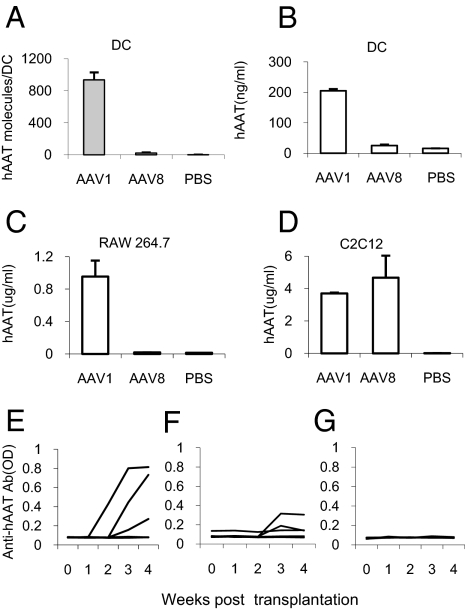

To understand the mechanism underlying the distinct immune responses, bone marrow-derived immature DCs were infected with rAAV1-hAAT or rAAV8-hAAT vectors. Real-time PCR analysis showed that high levels of vector DNA were detected in rAAV1-hAAT infected DCs, while vector DNA was nearly undetectable in rAAV8-hAAT infected cells (Fig. 2A). Transgene expression was evaluated by ELISA detection of hAAT levels in the culture media. As shown in Fig. 2B, rAAV1 mediated high levels of transgene expression. However, hAAT levels were undetectable in rAAV8-infected cells. Similar results were also observed in mouse macrophages (Fig. 2C). To test the infectious activity of the vectors, mouse myoblast C2C12 cells were infected. Both vector mediated high levels of hAAT (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Transduction and transplantation of dendritic cells. (A) Detection of rAAV vector DNA in bone marrow-derived DCs after in vitro infection with AAV1-hAAT or AAV8-hAAT or saline (MOI = 2.8 × 104 vg/cell) by real-time PCR. Each bar shows the average concentration of hAAT DNA (molecules per DCs) in each group (n = 4). (B–D) Transgene expression from DCs (B), mouse macrophage cell line, RAW 264.7 (C), and mouse muscle cell line C2C12 (D) after infection with AAV1-hAAT or AAV8- hAAT or saline (MOI = 103 vg/cell). Human AAT concentrations in culture media were assessed by ELISA. Each bar shows the average level of hAAT in treatment group (n = 3). (E–G) serum anti-hAAT antibody levels in NOD mice received a transplantation of dendritic cells ex vivo-infected with rAAV1-hAAT (E), rAAV8-hAAT (F), or saline (G). Each line shows anti-hAAT levels in an individual animal (n = 5).

DC Transduction Is Essential for the Immune Response, while Presence of Transgene Product Produced from Host Cells Is Not.

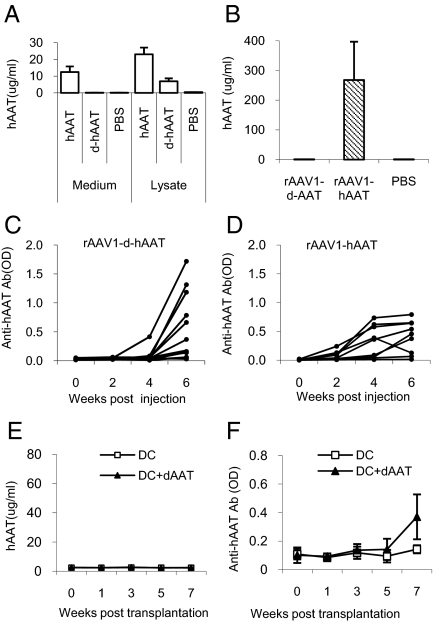

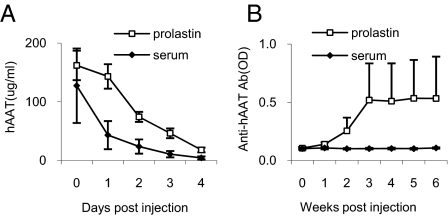

The fact that AAV1 transduces DCs while AAV8 does not suggests that DC transduction is important for the immune response to the transgene product. To test this hypothesis in vivo, we have transplanted ex vivo-infected DCs into adult NOD mice. This study showed that transplantation of rAAV1-hAAT transduced DCs induced high levels of transgene-specific antibodies (Fig. 2E), while transplantation of rAAV8-hAAT or saline treated DCs did not (Fig. 2 F and G). To test the hypothesis that vector transduction of dendritic cells alone is sufficient to induce immune response to transgene product, we have deleted the secretion signal sequence from hAAT cDNA in the rAAV-hAAT vector and created a vector (rAAV1-d-hAAT) that expresses hAAT protein in the cytoplasm but not secretory hAAT. Infection of C2C12 cells with rAAV1-d-hAAT vector resulted in detectable levels of hAAT in cell lysate, but not in the culture medium (Fig. 3A). IM injection of rAAV1-d-hAAT led to no detectable hAAT in the circulation (Fig. 3B), but a strong immune response to hAAT (Fig. 3C) which is comparable to that from rAAV1-hAAT injection (Fig. 3D). In addition, transplantation of rAAV1-d-hAAT infected DCs was sufficient to induce immune response to hAAT (Fig. 3 E and F). These results support our hypothesis, but are not definitive since trace amounts of released transgene product may be sufficient to trigger the immune system. To test whether host cell produced transgene product alone will induce an immune response, we have generated two hAAT transgenic NOD mouse lines using rAAV-hAAT cassette. Both lines express high levels of hAAT (0.5–10 mg/mL) in the circulation. Interestingly, injection of hAAT-containing serum from hAAT-tg NOD mice (hAAT-tg serum) into normal NOD mice did not induce immune responses to hAAT, while injection of hAAT purified from human plasma (Prolastin) induced strong immune responses, suggesting host cell-produced hAAT is not immunogenic (Fig. 4). These data demonstrate that transgene expression in DCs is critical for the immune response to the transgene product, and that host cell produced transgene product can evade the detection by the immune system.

Fig. 3.

Immune response to non-secretory transgene product in NOD mice. rAAV1-d-hAAT vector carries a hAAT gene with deletion of secretion signal sequence. (A) After infection of C2C12 cells with rAAV1-d-hAAT (d-hAAT, MOI = 103), hAAT protein can be detected by ELISA in the cells, but not in the culture medium. rAAV1- hAAT (hAAT) served as positive control group. Saline treated (PBS) cells as a negative control (n = 3). (B) hAAT levels in NOD mice injected with 2 × 1011 gv/mouse of rAAV1-CB-d-hAAT (rAAV1-d-AAT, n = 13), rAAV1-CB-hAAT (rAAV1-hAAT, n = 13), or injected with PBS (n = 13). Four weeks after vector injection, serum hAAT was detected by ELISA. (C and D) Anti-hAAT antibody levels were comparable in both rAAV1-CB-d-hAAT group (C) and rAAV1-CB-hAAT group (D). Each line shows the antibody levels in an individual animal (n = 13). (E and F) DC transplantation. Serum hAAT levels (E) and anti-hAAT antibody level (F) in NOD mice received DCs infected with rAAV1-d-hAAT or saline (MOI = 1013). Each line represents the average of hAAT or anti-hAAT antibody level in each group (n = 5).

Fig. 4.

Mouse cell produced transgene product does not generate an immune response. (A) Serum hAAT levels in NOD mice received a single injection of purified hAAT (Prolastin, 0.27 mg/mouse) or serum from hAAT-tg NOD mice (serum, 0.27 mg/mouse). Each line represents the average serum hAAT levels in each group detected by ELISA (n = 5). (B) Serum anti-hAAT levels. Note: no detectable anti-hAAT in mice receiving hAAT-tg NOD serum. Open square, Prolastin (purified hAAT); filed diamond, serum from hAAT-tg NOD mice.

Preimmunization with rAAV8 Suppresses rAAV1-Mediated Immune Response in a Transgene-Specific Manner.

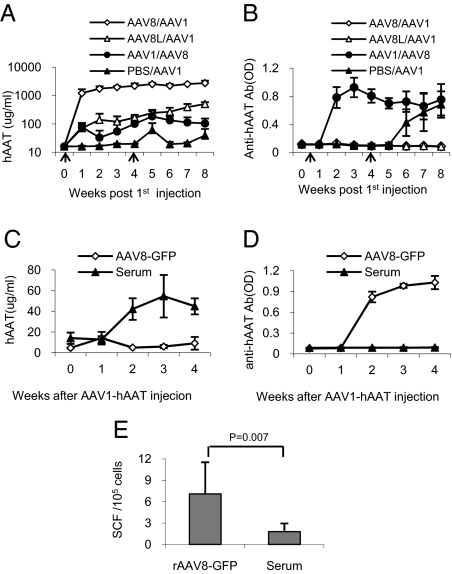

To test whether rAAV8 can suppress the immunogenicity from rAAV1, cohorts of NOD mice were injected IP with rAAV8-hAAT or with saline. These mice showed dose-dependent hAAT expressions and no anti-hAAT levels in the circulation (Fig. 5 A and B). When these animals were challenged with rAAV1-hAAT, no anti-hAAT antibody was detected in rAAV8-hAAT preimmunized groups, while the saline injected group produced high levels of anti-hAAT antibodies as expected (Fig. 5B). To test whether rAAV1-induced immune response will compromise rAAV8 expressed hAAT, a separate group of mice (n = 10) were first IM injected with rAAV1-hAAT vector. Four weeks after the first injection, animals received rAAV8-hAAT. As show in Fig. 5 A and B, rAAV8 injection did not significantly change the total serum levels of hAAT and anti-hAAT antibodies, indicating rAAV1-induced antibodies recognized rAAV8-expressed hAAT. Together, these results demonstrated that preimmunization with low dose of rAAV8 vector induced a tolerance to the same transgene product from rAAV1 vector, and that immune systems activated by rAAV1 were not suppressed by rAAV8. To test whether the immune tolerance is from the transgene product or from rAAV8 vector, cohorts of NOD mice were preimmunized with rAAV8-GFP or hAAT containing serum from hAAT-tg NOD mice (hAAT-tg serum). When challenged with rAAV1-hAAT, the rAAV8-GFP group produced low levels of hAAT and high levels of anti-hAAT antibodies, while the hAAT-tg serum-immunized group produced high levels of hAAT and no detectable levels of anti-hAAT antibodies (Fig. 5 C and D). ELISpot analysis also showed that the hAAT-tg-serum-immunized group displayed much lower cellular immune response to hAAT. Together, these results demonstrated that preimmunization with hAAT from an rAAV8 vector can suppress immune response to hAAT from an rAAV1 vector, and that host cell-produced transgene product induced tolerance to immunogenicity from an rAAV1 vector.

Fig. 5.

Mouse cell produced transgene product induces transgene specific immune tolerance. (A and B) Cohorts of NOD mice (4 weeks of age) were IP infected with a high dose (2 × 1011 gv/mouse) of rAAV8-hAAT (open diamond, AAV8/AAV1, n = 3), low dose (2 × 1010 gv/mouse) of rAAV8-hAAT (open triangle, AAV8L/AAV1, n = 4), or IM injected with rAAV1-hAAT (2 × 1011 gv/mouse, filled circle, AAV1/AAV8, n = 7) or saline (filed triangle, PBS/AAV1, n = 5). Four weeks after the first injection, mice were infected with 2 × 1011 gv/mouse of another serotype of rAAV-hAAT. Serum hAAT levels (A) and anti-hAAT antibody levels (B) were detected by ELISA. Note: no antibody was detected in rAAV8-hAAT immunized groups. (C–E) In a separate experiment, two groups of NOD mice (n = 5) were IP injected with rAAV8-GFP vector (filed triangle, AAV8-GFP, 2 × 1010 vg/mouse) at 4 weeks of age or injected IP with 100 μL serum from hAAT–tg mice for 4 weeks (open diamond, serum contains 0.27 mg of hAAT, 2 injections/week). At 8 weeks of age, all mice were injected IP with rAAV1-hAAT (2 × 1011 vg/mouse). Serum hAAT levels (C) and anti-hAAT antibody levels (D) were detected by ELISA, and cellular immune response was evaluated by ELISpot (E). Note: mouse produced hAAT (Serum) injected group did not produce anti-hAAT antibody.

Discussion

Recent advances in rAAV technologies have greatly improved the efficiency of gene delivery. Long-term and high levels of transgene expression have been achieved in animal models as well as in humans (9, 17, 18). However, the host immune response to a transgene product is one of the major hurdles to limit the successes of gene therapy in humans (19). Mingozzi et al. have shown that restricted the transgene expression in liver using a liver-specific promoter in rAAV2 vector induced immune tolerance to the transgene product (F.IX) (20, 21). Vandenberghe et al. showed that AAV8 failed to activate a T-cell response to the AAV8 capsid because the capsid lacks a heparin binding domain (RXXR), which is important for DC transduction (8). In the present study, we show that both humoral and cellular immune responses to transgene product can be avoided in the NOD mouse model using a rAAV8 vector. These results suggest that rAAV8 vector is unique among serotypes of AAV vectors in inducing transgene-specific immune tolerance. In addition to the effective transduction of liver and many other organs, this immune tolerance feature may enhance the use of rAAV8 vector for gene replacement therapy and for immunotolerance therapy.

It is commonly seen that immune response to transgene product is weaker in mouse models than in larger animal models or in humans (19). However, NOD mice are an exception and provide an excellent opportunity for studies of the immune response. In addition to high susceptibility for autoimmune disease such as type 1 diabetes and Sorgen's syndrome, NOD mice also display elevated immune responsiveness against foreign antigens and transgene products (16, 21, 22). The lack of immune response to transgene products from rAAV8 in the NOD mouse model strongly suggests that rAAV8 vector could be used in human clinical studies where immune response to transgene product must be avoided. Although further investigation is required, several lines of evidence support this contention (8, 11–15, 23, 24).

Immune responses are complex. It is commonly seen that animals with the same genomic background and in a well-controlled environment have different immune responses. For example, NOD mice are inbred mice and most of the female NOD mice spontaneously develop type 1 diabetes. However, even in the same environment, 20 to 30% of them never develop type 1 diabetes. In the present study, we observed uneven immune responses within the treatment groups. In the rAAV8-treated group, most of the animals did not develop detectable immune responses, while one mouse did develop low levels of immune responses. Similarly, most rAAV1-treated mice develop strong immune responses, while some rAAV1-treated mice have low or undetectable immune responses. The variability observed in this study is likely due to unknown individual differences including micro-environmental factors (food intake, light exposure, behavior, and unknown microbial exposure) and genetic variations (somatic mutations in T-cell receptors, antibodies and other critical genes, epigenetic differences, and SNPs). In addition, variation of vector injection, distribution, and transgene expression may also contribute to the variability of immune responses to hAAT from the rAAV1 vector. It has been reported that antibodies against transgene product from the rAAV8 vector were detected in some individual animals (25, 26). Further investigation focusing on individual differences in immune response to rAAV1 or rAAV8 treatment could reveal the mechanisms of AAV immunogenicity.

DCs play important roles in immune responses. Activation or transduction of these cells has been the focus of immunotherapies, such as vaccine or immune tolerance therapies. In this study, we showed that rAAV1 vectors efficiently transduced immature DCs and mediated strong immune humoral and cellular immune responses to transgene product. In contrast, rAAV8 failed to transduce DCs and instead induced immune tolerance. Although other components of the immune system such as regulatory T cells may be involved (27), our results demonstrated transgene expression in DCs is critical for transgene-specific immune responses. These results also suggest that rAAV1 vector has potential as a vaccine carrier (7). Although the cell surface receptors for AAV1 has not been identified, recent studies have shown that glycoproteins with α2,3 and α2,6 N-linked sialic acids are primary receptors for efficient AAV1 and AAV6 viral infection (28). α2,3 and α2,6 sialylated N-glycans are present in monocytes and DCs and play important roles in antigen uptake (29). It is likely that AAV1 transduces and activates DCs through these receptors. Future studies on the molecular interaction between AAV1 and DCs will provide a better understanding of the mechanism by which AAV1 mediates a strong immune response to transgene product.

The tolerance to transgene products from rAAV8 vector is intriguing. Our explanations for this observation are: 1) DC transduction is critical for immune response to transgene product (Fig. 3). rAAV8 vector is unable to infect DCs, and thus is unable to directly activate DCs (Fig. 2). 2) Unlike conventional protein therapy, rAAV-mediated gene therapy has several unique features. The transgene product, a foreign protein expressed in other cells, slowly and constantly presents in the circulation instead of peak-shaped in protein therapy. Therefore, the transgene product may evade the detection of the innate system and blunt the response of the host (Fig. 1). 3) The host cell produced “foreign protein” may be modified and accepted as a self protein. In the present study, we showed that human AAT from rAAV8 vector or from transgenic mice induced transgene-specific tolerance in naïve NOD mice. Although the detailed mechanisms underlying the tolerance remain for further investigation, our results clearly demonstrated that foreign protein produced in host cells is accepted by the host immune system if antigen-presenting cells or DCs are not transduced or activated in the first place.

In summary, we have shown the following: 1) rAAV1 vectors transduce DCs and induce transgene-specific immune responses efficiently; thus, they can be used as a vector for vaccine; 2) rAAV8 vectors fail to transduce DCs and induce immune tolerance to transgene products; thus, they can be used in gene replacement therapy where immune responses are not desired; 3) host cell-produced transgene product is able to evade the detection of host immune system if DC transduction or transgene expression in DCs can be avoided; and 4) host cell-produced foreign protein can induce specific immune tolerance.

Materials and Methods

rAAV Vectors.

rAAV-CB-hAAT and rAAV-CB-GFP vectors were previously described (30). rAAV-dAAT is identical to rAAV-CB-hAAT except rAAV-dAAT contains a mutant human alpha-1-antitrypsin cDNA (d-hAAT) in which the secretory sequence was deleted. All three vectors use CMV enhancer and chicken beta-actin promoter (CB promoter). For rAAV vector production, vector plasmid DNA were co-transfected with AAV1 or AAV8 helper plasmid to 293 cells by calcium phosphate precipitation. rAAV vectors were purified using iodixanol (IOD) gradients. The physical particle titers were determined by a dot-blot assay (9).

Animals.

Female NOD mice were purchased at 4 weeks of age from the Jackson Laboratory. All mice were housed in specific pathogen-free facilities at the University of Florida (Gainesville, FL). The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Florida approved all animal manipulations. For vector administration, mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and IM or IP injected with 100 μL rAAV vector or Ringer's solution. Human AAT transgenic NOD mice (hAAT-tg-NOD) were produced using rAAV-CB-hAAT cassette flanking with AAV2-ITRs. These hAAT-tg-NOD mice produce 0.5–10 mg/mL hAAT in the circulation. For serum transfusion studies, pooled serum from hAAT-tg-NOD mice were IP injected into female recipient mice at 4 weeks of age.

Preparation and Infection of Mouse Bone Marrow-Derived DCs (BM-DCs).

Bone marrow cells were isolated from the femurs and tibias of the 4–6-week-old non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice (31). For induction of immature DCs, bone marrow cells were cultured in RPMI medium 1640 (Sigma Chemical) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 ng/mL recombinant murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (mGM-CSF, R&D Systems), and 5 ng/mL IL-4 (R&D Systems). After 3 days induction, the immature DCs were infected with rAAV vector at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 103. For the detection of hAAT protein produced by DCs, DCs were cultured for 6 days after rAAV infection. Culture media were subjected to ELISA to determine the levels of hAAT. For DC transplantation experiments, DCs were infected with rAAV vector for 2 h, and washed three times with PBS. Infected DCs were resuspended with Ringer's injection solution (Baxter Healthcare Corp.) and injected IP into 4-week-old female NOD mice at the dose of 106 cells/mouse.

Detection of rAAV Vector DNA in DCs.

DCs were cultured overnight post-infection (MOI = 2.8 × 104) and washed three times with PBS. Hir DNA from 4 × 105 DCs was isolated and subjected to real-time PCR analysis using vector (hAAT cDNA)-specific primers. The forward primer was 5′-ACCCTTTGAAGTCAAGGACACCGA-3′. The reverse primer was 5′-TGCTGAAGACCTTAGTGATGCCCA-3′. The fluorogenic probe was 5′-FAM-AGCTGGGTGCTGCTGATGAAATACCT-TAMRA 3′. The PCR was performed using 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) for 40 cycles with initial denaturing at 95 °C for 10 min, denaturing at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 60 °C for 1 min, and extension at 60 °C for 1 min.

Detection of Transgene Expression and Immune Response Against Transgene Products.

hAAT in sera, media, and cell lysates, as well as anti-hAAT antibodies, were detected by ELISA as described previously (9). For hAAT specific ELISA, purified hAAT (Athens Research Technology Inc.) was used as the standard. Goat-anti-hAAT antibodies (ICL) were used as the primary antibody. Rabbit anti-hAAT (Sigma) and peroxides conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma) were used as secondary and tertiary antibodies. For detection of anti-hAAT antibodies, peroxide-conjugated goat-anti-mouse Ig antibodies (Sigma) were used. Detection of T-cell response against hAAT was performed using a mouse IFN-gamma ELISpot kit (eBioscience). Briefly, mouse splenocytes from NOD mice were isolated as described previously (32). The splenocytes (106 cells/well) were loaded with 1 mg/mL hAAT (Aralast, Baxter) in duplicate in a 96-well PVDF membrane plate (Millipore), which was precoated with anti-IFN-γ capture antibody. The plate was incubated for 48 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. All other procedures including washing, reactions with biotinylated detection antibody and Ad-HRP, and spot counting were performed following the manufacturers' instructions.

Acknowledgments.

We are grateful to Drs. Kenneth Berns and Alfred S. Lewin for helpful discussions and suggestions and to Diana Nolte for editorial assistance. We thank Drs. James M. Wilson and Guangping Gao for providing rAAV8 packaging plasmids. This work was supported in part by grants from National Institutes of Health (HL079132, DK05327–6) and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.McCarty DM, Monahan PE, Samulski RJ. Self-complementary recombinant adeno-associated virus (scAAV) vectors promote efficient transduction independently of DNA synthesis. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1248–1254. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Z, Asokan A, Samulski RJ. Adeno-associated virus serotypes: Vector toolkit for human gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2006;14:316–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vandenberghe LH, Wilson JM. AAV as an immunogen. Curr Gene Ther. 2007;7:325–333. doi: 10.2174/156652307782151416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herzog RW. Immune responses to AAV capsid: Are mice not humans after all? Mol Ther. 2007;15:649–650. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jooss K, Yang Y, Fisher KJ, Wilson JM. Transduction of dendritic cells by DNA viral vectors directs the immune response to transgene products in muscle fibers. J Virol. 1998;72:4212–4223. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4212-4223.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xin KQ, et al. Induction of robust immune responses against human immunodeficiency virus is supported by the inherent tropism of adeno-associated virus type 5 for dendritic cells. J Virol. 2006;80:11899–11910. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00890-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veron P, et al. Major subsets of human dendritic cells are efficiently transduced by self-complementary adeno-associated virus vectors 1 and 2. J Virol. 2007;81:5385–5394. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02516-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vandenberghe LH, et al. Heparin binding directs activation of T cells against adeno-associated virus serotype 2 capsid. Nat Med. 2006;12:967–971. doi: 10.1038/nm1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu Y, et al. Therapeutic level of functional human alpha 1 antitrypsin (hAAT) secreted from murine muscle transduced by adeno-associated virus (rAAV1) vector. J Gene Med. 2006;8:730–735. doi: 10.1002/jgm.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Z, et al. Adeno-associated virus serotype 8 efficiently delivers genes to muscle and heart. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:321–328. doi: 10.1038/nbt1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, et al. Sustained correction of disease in naive and AAV2-pretreated hemophilia B dogs: AAV2/8-mediated, liver-directed gene therapy. Blood. 2005;105:3079–3086. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McEachern KA, et al. AAV8-mediated expression of glucocerebrosidase ameliorates the storage pathology in the visceral organs of a mouse model of Gaucher disease. J Gene Med. 2006;8:719–729. doi: 10.1002/jgm.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishiwata A, et al. Phenotype correction of hemophilia A mice with adeno-associated virus vectors carrying the B domain-deleted canine factor VIII gene. Thromb Res. 2006;118:627–635. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ziegler RJ, et al. Correction of the biochemical and functional deficits in fabry mice following AAV8-mediated hepatic expression of alpha-galactosidase A. Mol Ther. 2007;15:492–500. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barbon CM, et al. AAV8-mediated hepatic expression of acid sphingomyelinase corrects the metabolic defect in the visceral organs of a mouse model of Niemann-Pick disease. Mol Ther. 2005;12:431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang YC, et al. Immunity to adeno-associated virus serotype 2 delivered transgenes imparted by genetic predisposition to autoimmunity. Gene Ther. 2004;11:233–240. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song S, et al. Stable therapeutic serum levels of human alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) after portal vein injection of recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1299–1306. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manno CS, et al. AAV-mediated factor IX gene transfer to skeletal muscle in patients with severe hemophilia B. Blood. 2003;101:2963–2972. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arruda VR, et al. Safety and efficacy of factor IX gene transfer to skeletal muscle in murine and canine hemophilia B models by adeno-associated viral vector serotype 1. Blood. 2004;103:85–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mingozzi F, et al. Induction of immune tolerance to coagulation factor IX antigen by in vivo hepatic gene transfer. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1347–1356. doi: 10.1172/JCI16887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song S, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated alpha-1 antitrypsin gene therapy prevents type I diabetes in NOD mice. Gene Ther. 2004;11:181–186. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leijon K, Hammarstrom B, Holmberg D. Non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice display enhanced immune responses and prolonged survival of lymphoid cells. Int Immunol. 1994;6:339–345. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang H, et al. Effects of transient immunosuppression on adenoassociated, virus-mediated, liver-directed gene transfer in rhesus macaques and implications for human gene therapy. Blood. 2006;108:3321–3328. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mays LE, et al. Adeno-associated virus capsid structure drives CD4-dependent CD8+ T cell response to vector encoded proteins. J Immunol. 2009;182:6051–6060. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang H, et al. Multiyear therapeutic benefit of AAV serotypes 2, 6, and 8 delivering factor VIII to hemophilia A mice and dogs. Blood. 2006;108:107–115. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-5115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao G, et al. Erythropoietin gene therapy leads to autoimmune anemia in macaques. Blood. 2004;103:3300–3302. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao O, et al. Induction and role of regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells in tolerance to the transgene product following hepatic in vivo gene transfer. Blood. 2007;110:1132–1140. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-073304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Z, Miller E, Agbandje-McKenna M, Samulski RJ. Alpha2,3 and alpha2,6 N-linked sialic acids facilitate efficient binding and transduction by adeno-associated virus types 1 and 6. J Virol. 2006;80:9093–9103. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00895-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Videira PA, et al. Surface alpha2–3- and alpha2–6-sialylation of human monocytes and derived dendritic cells and its influence on endocytosis. Glycoconj J. 2008;25:259–268. doi: 10.1007/s10719-007-9092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song S, et al. Ex vivo transduced liver progenitor cells as a platform for gene therapy in mice. Hepatology. 2004;40:918–924. doi: 10.1002/hep.20404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaufman CL, et al. Phenotypic characterization of a novel bone marrow-derived cell that facilitates engraftment of allogeneic bone marrow stem cells. Blood. 1994;84:2436–2446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu Y, et al. Alpha1-antitrypsin gene therapy modulates cellular immunity and efficiently prevents type 1 diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:625–634. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]