Abstract

Interleukin (IL)-10 is an immunoregulatory cytokine that is produced by diverse cell populations. Studies in mice suggest that the cellular source of IL-10 is a key determinant in various disease pathologies, yet little is known regarding the control of tissue-specific human IL-10 expression. To assess cell type-specific human IL-10 regulation, we created a human IL-10 transgenic mouse with a bacterial artificial chromosome (hIL10BAC) in which the IL10 gene is positioned centrally. Since human IL-10 is biologically active in the mouse, we could examine the in vivo capacity of tissue-specific human IL-10 expression to recapitulate IL-10-dependent phenotypes by reconstituting Il10−/− mice (Il10−/−/hIL10BAC). In response to LPS, Il10−/−/hIL10BAC mice proficiently regulate IL-10-target genes and normalize sensitivity to LPS toxicity via faithful human IL-10 expression from macrophages and dendritic cells. However, in the Leishmania donovani model of pathogen persistence, Il10−/−/hIL10BAC mice did not develop the characteristic IL-10+IFN-γ+CD4 T cell subset thought to mediate persistence and, like Il10−/− mice, cleared the parasites. Furthermore, the IL-10-promoting cytokine IL-27 failed to regulate transgenic human IL-10 production in CD4+ T cells in vitro which together suggests that the hIL10BAC encodes for weak T cell-specific IL-10 expression. Thus, the hIL10BAC mouse is a model of human gene structure and function revealing tissue-specific regulatory requirements for IL-10 expression which impacts disease outcomes.

Keywords: leishmania, LPS, T cell, transgenic, IL-27

A growing body of literature indicates that the cellular source of IL-10 plays a central role in disease pathology based predominately on studies in mice (1). The principal source of IL-10 is regarded to be T cells (1), although a variety of other cell types including monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cell subsets, B cells, and NK cells also produce IL-10 (2, 3). The importance of T cell-derived IL-10 has been demonstrated in mice with T cell-specific ablation of the Il10 gene which results in severe immunopathology associated with Toxoplama gondii infection and augmented contact hypersensitivity (4). Moreover, deletion of Il10 in Tregs leads to unchecked inflammation at mucosal surfaces (5).

Similarly, IL-10 is a critical player in leishmaniasis pathology and a lack of IL-10 has invariably been associated with resistance to disease (6–8). Although human forms of leishmanial infection are associated with enhanced IL-10 production (9), direct evidence for the role of IL-10 in leishmaniasis is derived primarily from mice in which IL-10-secreting T-cell populations are suspected to influence host susceptibility (10).

In contrast, the in vivo response to LPS is mediated by myeloid-derived IL-10 (11). In animal models of endotoxic shock, blockade of IL-10 results in uncontrolled systemic inflammatory responses typified by elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines leading to death (12). In human sepsis, IL-10 administration inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines (13) and blocks the activation of monocytes (14), indicating the conserved biologic properties of IL-10 in controlling inflammation.

The importance of appropriate temporal-spatial IL-10 regulation has been demonstrated in the mouse, yet the contribution of cell-specific IL-10 expression in human disease is lacking. To address the issue of tissue-specific human IL-10 regulation and function in vivo, we created transgenic mice with a human bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC). BACs (and other large genomic DNA constructs) typically support cell type-specific transgene expression (15). In the myeloid compartment, transgenic human IL-10 is appropriately regulated leading to rescue of Il10−/− mice from LPS toxicity. Unexpectedly, transgenic human IL-10 is only weakly expressed in T cells which correlates with a failure to recapitulate Leishmania donovani persistence normally observed in wild-type (WT) mice. Taken together, these data suggest conservation of innate IL-10 expression but divergent regulatory requirements in T cells that may result in differential disease pathogenesis.

Results

Generation and Initial Characterization of Human IL10 BAC (hIL10BAC) Transgenic Mice.

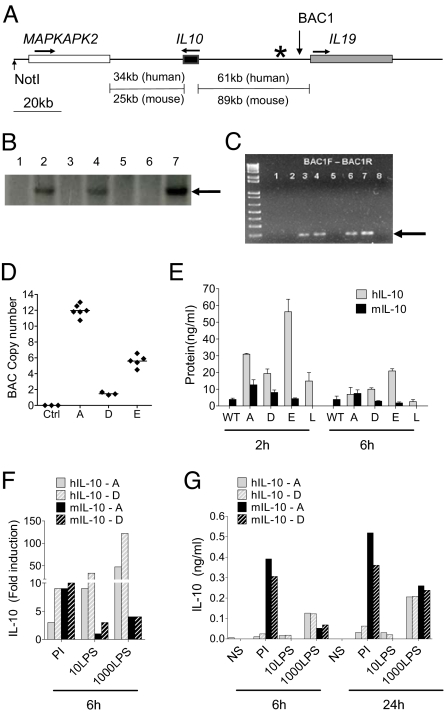

We identified an approximately 180-kb human BAC in which the IL10 gene is situated centrally and flanked by the MAPKAPK2 and IL19 genes. Sequence alignments revealed shared synteny between the mouse and human IL10 locus on chromosome 1 (Fig. 1A). Founder mice were screened for presence of the transgene by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 1B) and PCR-based genotyping (Fig. 1C). Transgene copy numbers were determined in three transgenic lines using a real-time PCR-based approach by normalizing the signal intensity from the target transgenic sequence to standard curve of control genes with known copy numbers. We identified approximately 1 copy in line D, 6 copies in line E, and 12 copies in line A (Fig. 1D). In all founder lines, hIL10BAC mice are healthy with no apparent signs of disease or immunological irregularities for at least the first 1.5 years of life and have normal leukocyte distributions in the spleen.

Fig. 1.

Generation and characterization of hIL10BAC Tg mice. (A) hIL10BAC structure with intergenic distances (“*” indicates location of Southern blot probe; “BAC1” indicates location of genotyping primers). (B) Southern blots of founders. (C) Genotyping of hIL10BAC mice by PCR. (D) hIL10BAC copy number estimates in three founder lines (A, D, and E). (E) Human and mouse IL-10 levels in serum of various founder lines treated with LPS in vivo for 2 or 6 h. (F) Human and mouse IL-10 mRNA expression in whole spleen cultures from Lines A and D. (G) Human and mouse IL-10 production in whole spleen cultures from Lines A and D (one of two representative experiments).

To address potential copy-number effects on transgenic human IL-10 expression, we challenged hIL10BAC mice from different lines with LPS. After 2 h, some differences in transgenic human IL-10 production were observed between the hIL10BAC lines but were independent of copy number and decreased to comparable levels of mouse IL-10 by 6 h post-challenge. Levels of endogenous mouse IL-10 were similar between transgenic lines and WT mice suggesting little feedback between human and mouse IL-10.

To further exclude an effect of transgene copy number, we assessed transgenic human and endogenous mouse IL-10 expression in splenocytes from Lines A and D. Transgenic human IL-10 mRNA (Fig. 1F) and protein (Fig. 1G) is inducible to comparable levels in both Lines A and D by both phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and ionomycin (PI) and LPS although endogenous mouse IL-10 production was consistently greater following PI stimulation. Thus, the human IL10 BAC is regulated similarly in separate transgenic lines, in a copy-number-independent manner.

Basal Tissue Expression of Human and Endogenous Mouse IL-10 in hIL10BAC Mice.

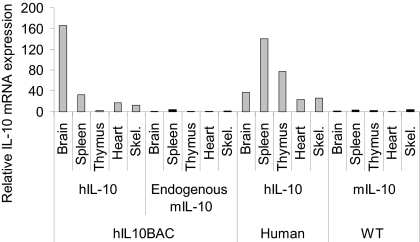

Since transgenic human IL-10 expression is independent of copy number, we focused our investigation on Line A. To determine the fidelity of the BAC in tissue-specific IL-10 regulation we assessed basal levels of human and mouse IL-10 mRNA expression in various tissues of hIL10BAC, WT mice and primary human tissues. Mouse IL-10 mRNA was not detected or in low abundance in all tissues examined (Fig. 2). However, we observed varying degrees of constitutive expression of human IL-10 mRNA in hIL10BAC and primary human tissues. The detection of human mRNA transcripts in hIL10BAC mice however, did not result in basal human IL-10 production in the serum or in brain homogenates. In addition, we observed constitutive expression of human and mouse MAPKAPK2 mRNA in all tissues examined from WT and hIL10BAC mice as well as primary human tissues (Fig. S1). Also, we found constitutive expression of transgenic human IL-19 in tissues from hIL10BAC Line A mice. In contrast, we did not observe mouse or human IL-19 mRNA in WT or primary human tissues respectively (Fig. S2). Conversely, we did not detect human IL-19 mRNA in hIL10BAC Line D mice in any of the tissues or cell types examined. Since transgenic human IL-10 expression between hIL10BAC Line A, Line D, as well as Line E is similar (Fig. 1 E–G), we conclude that the presence of human IL-19 transcripts in Line A does not impinge on IL-10 expression but rather suggests a regulatory boundary between the human IL10 and IL19 genes. It should be noted that unlike IL-10, human IL-19 is not biologically active on mouse cells (16). Thus, transgenic human IL-19 should have no functional impact in hIL10BAC mice. Overall these data establish that the human IL10 BAC cassette supports appropriate human IL-10 expression.

Fig. 2.

Basal expression of IL-10 in various tissues. Relative human and mouse IL-10 mRNA expression in hIL10BAC, WT, and primary human tissues. Samples were normalized to beta-2 microglobulin and expressed as fold change relative to mouse IL-10 mRNA levels in brain (one of three representative experiments).

Human IL-10 Is Regulated by Murine Transcription Factors in hIL-10BAC NK Cells.

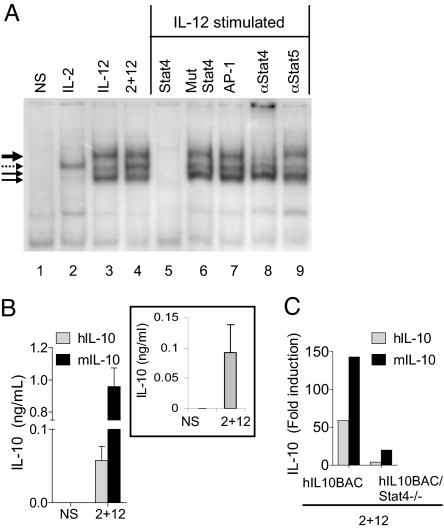

We previously identified a conserved Stat4-binding element in the fourth intron of the murine Il10 gene which binds IL-12-induced Stat4 in NK cells (17). We confirmed that mouse Stat4 binds the conserved human Stat4 motif following IL-12 stimulation (Fig. 3A). We identified three complexes that bind the human STAT element by EMSA (Fig. 3A, solid arrows). Cold-competition and supershift analyses confirmed the specificity of this interaction. Interestingly, IL-2 induced the binding of an unidentified complex to the human but not mouse intronic STAT site [Fig. 3A, dotted arrow and (17)]. This complex is likely to contain Stat5 as a recent report demonstrated that stimulation of human T cells with IL-2 induced Stat5 binding to this site (18).

Fig. 3.

Endogenous mouse and transgenic human IL-10 expression in NK cells. (A) EMSA of human Stat4 element with extracts from mouse NK cells. Stimulation with the indicated cytokines in lanes 1–4. Lanes 5–7, cold competition with the indicated oligos. Lanes 8 and 9 are supershifts with the indicated antibodies. (B) Human/mouse IL-10 production from hIL10BAC NK cells (Inset: IL-10 production in human NK cells). (C) IL-10 mRNA expression in hIL10BAC or hIL10BAC/Stat4−/− NK cells (one of two respresentative experiments).

To confirm that IL-12-induced murine transcription factors regulate the human IL10 BAC, we stimulated hIL10BAC NK cells with IL-2+IL-12 which as expected induced mouse and human IL-10 production (Fig. 3B). Primary human NK cells stimulated with IL-2+IL-12 similarly induce human IL-10 production (Fig. 3, inset). In addition, we assessed the dependence of human IL-10 expression on Stat4 by crossing the hIL10BAC with the Stat4−/− mouse (hIL10BAC/Stat4−/−). In the absence of Stat4, IL-2+IL-12 induction of mouse and human IL-10 is predictably impaired in NK cells (Fig. 3C), indicating further that the hIL10BAC is regulated by the mouse transcriptional machinery.

hIL10BAC-Derived IL-10 Regulates Target Genes in Vivo and Rescues Il10−/− Mice from LPS-Induced Lethality.

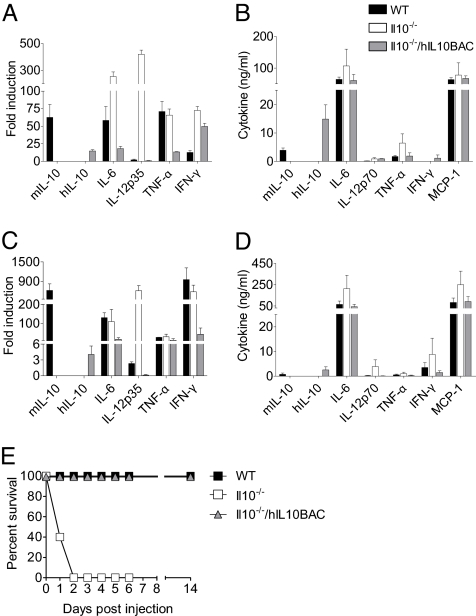

Il10−/− animals are highly susceptible to endotoxic shock due to over-expression of proinflammatory cytokines (12). We examined the regulation and function of human IL-10 in vivo by backcrossing hIL10BAC with Il10−/− mice (Il10−/−/hIL10BAC) and testing the ability of human IL-10 to regulate target genes 2 and 6 h after LPS challenge. As expected, proinflammatory cytokine mRNA and protein expression was elevated in the livers and serum, respectively, of Il10−/− mice (Fig. 4 A–D). Importantly, in the absence of mouse IL-10, Il10−/−/hIL10BAC mice regulate IL-10-target genes much like WT mice.

Fig. 4.

Transgenic human IL-10 function in vivo. (A) mRNA expression profile of inflammatory cytokines in WT, Il10−/− or Il10−/−/hIL10BAC mice 2 h after administration of LPS i.p. (B) Serum levels of inflammatory cytokines 2 h after LPS injection. (C) mRNA expression profile of cytokines 6 h after LPS injection. (D) Serum levels of inflammatory cytokines 6 h after LPS injection. (E) Survival of WT, Il10−/− or Il10−/−/hIL-10BAC mice 2 h after LPS challenge.

To determine whether reconstitution with the human IL10 BAC can normalize LPS-sensitivity, we challenged WT, Il10−/− and Il10−/−/hIL10BAC mice with LPS and monitored the animals at 12-h intervals for morbidity and mortality (Fig. 4E). There was 100% mortality of Il10−/− mice within 48 h while WT and Il10−/−/hIL-10BAC mice had 100% survival. These data suggest that in myeloid cells, human IL-10 is appropriately regulated in hIL10BAC mice, leading to effective control of IL-10 target genes in vivo and rescuing Il10−/− mice from LPS-induced death.

Human IL10 Is Appropriately Regulated in the Myeloid Compartment of hIL10BAC Mice.

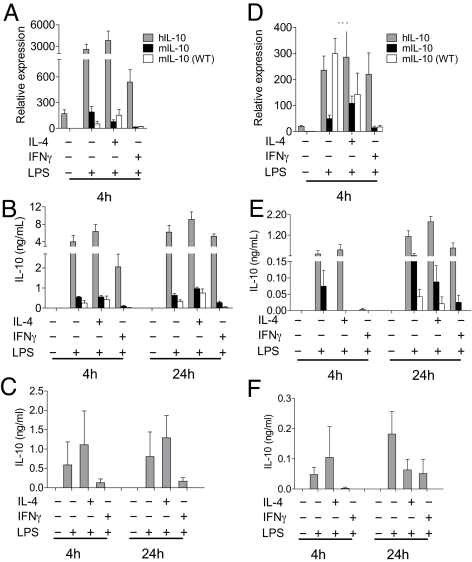

To verify myeloid-specific IL-10 expression we used bone marrow derived macrophages (BMMs) and dendritic cells (BMDCs) from hIL10BAC and WT mice. We also used human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) and DCs (MDDCs) to validate IL-10 expression patterns. Constitutive expression of both mouse and human IL-10 mRNA were found in BMMs (Fig. 5A) and confirmed in MDMs as reported previously (19). LPS treatment enhanced mouse and transgenic human IL-10 mRNA and protein expression and coculture with IL-4 resulted in modest increases (Fig. 5 A and B). However, IFN-γ treatment inhibited human and mouse IL-10 expression in BMM (Fig. 5 A and B) and human IL-10 in MDMs (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Human and mouse IL-10 expression in the myeloid compartment. (A) IL-10 mRNA and (B) IL-10 production in BMMs. (C) IL-10 production from human MDMs. (D) IL-10 mRNA and (E) IL-10 production from BMDCs. (F) IL-10 production from human MDDCs.

In BMDCs, LPS also induced mouse and transgenic human IL-10 mRNA and protein expression although at lower levels (Fig. 5 D and E). LPS co-stimulation with IL-4 had minimal effects on both mouse and transgenic human IL-10 expression. In contrast, IFN-γ strongly inhibited mouse IL-10 expression. The effects of IFN-γ on transgenic human IL-10 were less obvious and restricted to inhibition of IL-10 secretion after 4 h (Fig. 5E). Interestingly, the trends in human IL-10 production in BMDCs were similar in MDDCs (Fig. 5F). These data indicate that the human IL10 BAC transgene is predictably regulated in BMMs and BMDCs in an analogous manner to MDMs and MDDCs (albeit to lower levels) and suggests both transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of human and mouse IL-10 in the myeloid compartment (20).

Il10−/−/hIL10BAC Mice Resolve Leishmania donovani Infection.

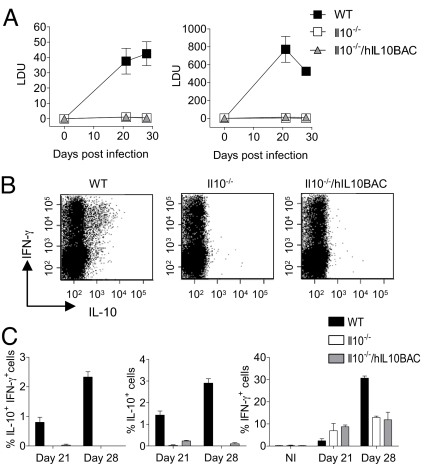

Infection with the intracellular parasite L. donovani (the causative agent of visceral leishmaniasis, VL) results in a persistent infection in WT mice that is thought to be mediated by IL-10-expressing CD4+ T cells. Accordingly, L. donovani infection is self-resolving in Il10−/− mice (8). Thus, we infected WT, Il10−/−, and Il10−/−/hIL10BAC mice with L. donovani and monitored the course of infection in the two primary target organs, the spleen and liver to assess the influence of T cell-derived IL-10 in vivo (Fig. 6A). As expected, the parasite burden increased steadily during the 1st 4 weeks of infection in the spleens of WT L. donovani-infected mice. Similarly, parasite burden in the livers of WT mice peaked at day 21 and began to decline thereafter (Fig. 6A, right panel). Predictably, the parasite burdens were very low in the livers and spleens of Il10−/− mice and the infection resolved by day 28 post-infection. Surprisingly, Il10−/−/hIL10BAC mice also had low parasite burdens and the infection was self-resolved by the day 28 time point.

Fig. 6.

Response of hIL10BAC mice to infection with L. donovani. (A) Splenic (Left) and hepatic (Right) parasite burdens in WT, Il10−/− or Il10−/−/hIL10BAC mice. Data are in Leishmania donovani Units (LDU). (B) ICS for IL-10 and IFN-γ in splenic CD4+ T cells from infected mice (day 28) restimulated with amastigote-pulsed BMDCs. (C) Graphic representation of percent IL-10+IFNγ+ double positive (Left), total IL-10+ (Center), and total IFNγ+ (Right) CD4+ T cells from infected mice at 21 or 28 days post infection (n = 3 per group) NI; non-infected).

During L. donovani infection, populations of IL-10+IFN-γ+ T cell emerge that are believed to facilitate pathogen persistence (21). Consistent with previous reports, IL-10+IFN-γ+ CD4 T cells were readily detectible in WT mice at day 21 and 28 post-infection (Fig. 6 B and C). However, in Il10−/−/hIL10BAC mice, this cellular subset was not clearly identified. Nonetheless, regulation of IFN-γ expression was intact in CD4+ T cells from Il10−/−/hIL10BAC and Il10−/− mice albeit at lower levels which may be a function of the low parasite burden (Fig. 6D). These data demonstrate that during L. donovani infection, regulation of transgenic human IL-10 production in CD4 T cells is deficient relative to mouse IL-10, resulting in dramatic disparities in disease outcome.

Disparate Expression of Transgenic Human and Endogenous Mouse IL-10 in hIL10BAC T Cells.

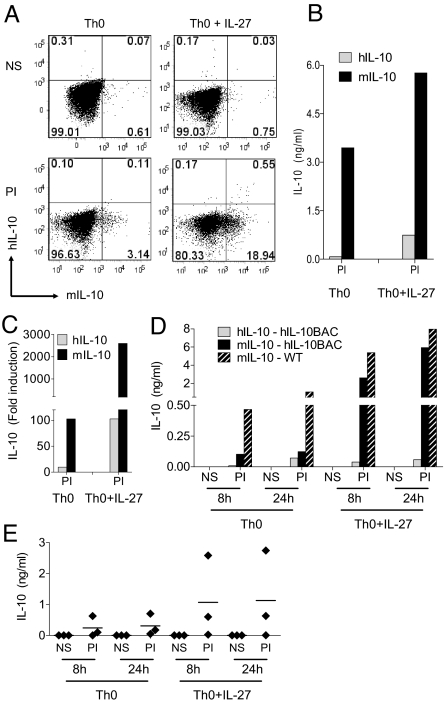

To further explore human IL-10 regulation in CD4+ T cells, we examined the ability of IL-27 to augment T cell-derived human IL-10 expression in vitro. In CD4-enriched Th0 cultures, PI re-stimulation induced a small population of CD4+ T cells expressing mouse but not human IL-10 (Fig. 7A, bottom left). In agreement with Stumhoffer and colleagues (22), the addition of IL-27 resulted in a substantial increase of mouse IL-10+CD4+ T cells (Fig. 7A, bottom right). However, only a modest increase in human IL-10+CD4+ T cells (≈0.5%) was observed (Fig. 7A, bottom right). This discrepancy was also evident in culture supernatants (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Human and mouse IL-10 expression in CD4 T cells. (A) IL-10 ICS in CD4+ Th0 cells from hIL-10BAC mice cultured +/- IL-27 (NS = non-stimulated; PI = PMA+ionomycin). (B) IL-10 production from enriched CD4+ T cell cultures. (C) IL-10 mRNA expression in Th0 cultures from naïve CD4+CD62L+ cells (one of two representative experiments). (D) Human (solid gray) and mouse (solid black) IL-10 production in naïve CD4+CD62L+ T cells from hIL-10BAC mice. Mouse IL-10 production in WT (black hashed bars) naïve T cells (one of two representative experiments). (E) Human IL-10 production from CD4+CD45RA+ naïve human Th0 cells cultured +/- IL-27 (three donors).

These results were confirmed in naïve CD4+CD62L+ T cells cultured with or without IL-27. Re-stimulation of naïve CD4+ Th0 cells cultured in the presence of IL-27 resulted in a strong enhancement of mouse IL-10 mRNA and protein as reported previously (22) but comparatively weak to no induction of human IL-10 mRNA and protein was observed (Fig. 7 C and D). Of note, we have established that under various culture conditions, human IL-10 is also weakly expressed in naïve T cells from hIL10BAC Lines D and E which further validates this unexpected finding (Figs. S3 and S4).

To address the degree of similarity between transgenic and endogenous human IL-10 production in T cells, we cultured naïve CD4+CD45RA+ cells from several donors under the same Th0 conditions +/- IL-27 (Fig. 7E). IL-10 production is known to be highly variable among humans (23, 24). Accordingly, we observed a wide distribution in IL-10 expression between donors. Co-culture with IL-27 resulted in a modest increase in one donor and in another case, did not enhance IL-10 production at all. However in another donor, we observed a substantial increase in IL-10 production following IL-27 co-culture. These data suggest that human IL-10 expression is under additional regulatory restraint and the hIL10BAC represents one of several possible outcomes for T cell-derived human IL-10 production.

Discussion

BAC transgenic approaches are widely used to study gene regulation in vivo as they generally support tissue-specific gene transcription patterns of the endogenous chromosomal gene (15,25). In addition, BAC transgenes are insulated from local chromatin interference and thus are expressed independently of the position of integration in the mouse genome (26). Moreover, tissue-specific gene expression can be transferred across species to mice (27, 28). In fact, Frazer and colleagues showed that human apolipoprotein(a) is appropriately regulated in yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) transgenic mice despite the fact that this gene is not present in the mouse genome (29).

In this study, we hypothesized that the human IL10 BAC contained the genomic regulatory sequences which control cell-specific human IL-10 expression. Indeed, in BMMs and BMDCs human IL-10 is appropriately regulated in response to LPS and functions in vivo to rescue reconstituted Il10−/− mice (Il10−/−/hIL10BAC) from endotoxemia suggesting conservation of the innate IL-10 response to LPS. Also, by comparing human IL-10 expression in several transgenic lines we determined that transgenic human IL-10 is regulated independent of copy number suggesting there is no locus control region (LCR) activity within the BAC (30).

Since T cells are thought to be the primary source of IL-10, it was surprising that Il10−/−/hIL10BAC mice effectively cleared L. donovani parasites similar to Il10−/− animals (Fig. 6A). Pathogen clearance was associated with a failure to generate hIL-10-expressing CD4+ T cells (Fig. 6 B and C). In human VL, disease is associated with elevated IL-10 levels in the serum but the cellular sources have been elusive (31). However, individuals with VL display an accumulation of IL-10 mRNA in CD25−Foxp3− T cells within the spleen (32). Another report identified increases in IL-10-expressing CD4 and CD8 T cells in patients with active leishmanial disease (33). Yet, interestingly, the majority of individuals that become infected with visceralizing Leishmania species do not develop disease (7). It is tempting to question if resistance to Leishmanial disease is associated with additional regulatory control of IL-10-secreting T cell subsets as observed in hIL10BAC mice.

There are alternate explanations for these findings including insufficient genomic information to fully recapitulate human IL-10 expression profiles. This is unlikely given that the human IL10 BAC contains more flanking sequence than is thought to be required to mimic chromosomal expression (25). In addition, by verifying similar human IL-10 expression patterns in various cell types for each hIL10BAC line, we in effect rule out human IL-10 expression artifacts that may exist in a single transgenic line despite different transgene copy numbers and presumed sites of integration. Another argument could be that the mouse transcriptional machinery does not accurately regulate the human DNA cassette. Again, this is improbable for the above reasons and since tissue-specific gene regulation is transferable across species to mice (15). In fact, a recent study demonstrated that the mouse transcriptional machinery supports faithful species-specific gene expression profiles across an entire human chromosome (34).

Still another possibility is that we have not identified the proper stimulation conditions to induce optimal T cell-derived human IL-10 production. Species differences in cytokine induction have been reported and in the case of the Th17 linage, different cytokine milieus drive mouse and human Th17 differentiation and survival (35). In naïve human CD4+ T cells, we observed a large degree of inter-individual variation in IL-10 production in response to IL-27 co-culture ranging from low (as observed in hIL10BAC mice) to high (Fig. 7E). Nevertheless, our findings indicate that IL-27 has the capacity to induce high IL-10 production from T cells in some individuals when cultured under the same conditions as mouse T cells (22).

In that regard, IL-10 production profiles are suspected to be under the influence of SNPs 5′ to the IL10 gene (24) which appear to operate in a tissue- and receptor-specific manner (23). In fact, IL10 promoter SNPs are also correlated with differential risk for a variety of infectious and autoimmune diseases presumably due at least in part to differential IL-10 expression (36). Sequence analysis of the human IL10 BAC revealed a SNP haplotype block, which has previously been associated with low IL-10 production (IL-10-819T) (37). Furthermore, the alternative IL10-819C genotype was recently found to be associated with susceptibility to lesion formation and higher serum levels of IL-10 in L. braziliensis infected individuals (38). We reported previously that SNPs in the IL-10-819T haplotype block display unique DNA-protein binding patterns in T cells, suggesting these allelic variants may impact biological function (39). It will be important to explore if other stimuli will normalize variation in T cell-derived human IL-10 production and determine the relative contribution of host genetic factors in these responses. Thus the hIL10BAC mouse is an in vivo model of cell-specific human IL-10 regulation and function. Taken together, these data suggest that the human IL10 BAC cassette is regulated appropriately in hIL10BAC mice and encodes for weak IL-10 production in T cells, which impacts leishmaniasis susceptibility.

Materials and Methods

Generation of hIL10BAC Transgenic Mice.

A 181-kb BAC clone (RP11–262N9) from human chromosome 1 containing the human genes MAPKAPK2, IL10, and IL19 was used to create hIL10BAC transgenic mice. The DNA was subjected to NotI digestion and the insert was purified for microinjection. There was an internal NotI restriction site identified 6 kb within the BAC insert which is 39 bp 5′ to the ATG start-site of the first exon of the MAPKAPK2 gene. The purified BAC following NotI digestion was 175 kb in length and was injected into fertilized oocytes of C57BL/6 mice. Experimental procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee.

Determination of Transgene Copy Number.

At least three individual mice from three separate litters in each founder line were used to assess transgene copy numbers. To determine transgene copy number estimates, quantitative PCR assays were designed to detect the hIL10BAC transgene. Data were analyzed and compared to a standard curve of known genes with varying copy numbers. Additional methods are available in SI Text.

EMSA.

Briefly, the DNA-protein binding reaction consisted of 10 μg nuclear protein extract, 1 μg poly (dI-dC) (Sigma), 4 μL 5× binding buffer, and 1.5 × 104 cpm 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probe as previously described (40).

Preparation and Stimulation of BMM/BMDC Cultures.

Primary bone marrow derived macrophages were prepared by flushing bone marrow from the femurs and tibias of mice and cells were plated at 106/mL in six-well plates in DMEM. For BMMs, media were supplemented with 30% conditioned media from the supernatant of M-CSF-secreting L929 fibroblasts. For BMDCs, media were supplemented with 30 ng/mL GM-CSF. Before stimulation, some groups were primed for 2 h with 10 ng/mL IL-4 or 100 U/mL IFN-γ.

Preparation and Stimulation of Murine T Cells.

For enriched CD4+ T cells, splenocytes were depleted of CD8+ and NK1.1+ cells and stimulated with 5 μg/mL anti-CD3 and anti-CD28. For naïve T cells, CD4+CD62L+ cells were isolated from spleens by negative selection with magnetic beads (R&D Systems). For Th0 cultures, IFN-γ and IL-4 were neutralized with 50 μg/mL anti-mouse IFN-γ and 50 μg/mL anti-mouse IL-4. Fifty ng/mL rmouse IL-27 was added where indicated. On day 5, cells were re-stimulated for 4 h with 10 ng/mL (PMA) and 1 μg/mL Ionomycin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) in the presence of Brefeldin A (BD Biosciences). Cells were washed and stained with VIVID (Invitrogen) to determine dead cells, fixed and permeabilized with BD cytofix/cytoperm kit, and stained with CD3, CD4, and mouse and human IL-10. Cells were acquired on a BD LSRII. Data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Isolation and Stimulation of Naïve Human T Cells.

Naïve human T cells were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) by Ficoll hypaque gradients and CD4+CD45RA+ naïve human T cells were sorted on a BD FACSAria. Cells were plated in 24-well plates coated with 5 μg/mL anti-CD3 and 10 μg/mL anti-CD28 for 3 days. To generate non-polarized T cells (Th0), IFN-γ and IL-4 were neutralized with 10 μg/mL anti-IFN-γ and 10 μg/mL anti–IL-4, respectively. Where indicated, 50 ng/mL rhuman IL-27 was added to Th0 cultures. On day 3, cells were removed from these plates, washed, and reseeded in fresh media supplemented with anti-IFN-γ, anti–IL-4, and, in some cases, rmouse IL-27. On day 5, cells were washed and restimulated.

mRNA Analyses.

Total RNA was isolated (TRIzol, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was generated using a first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). Total human RNA isolated from tissues of healthy donors was purchased from BioChain Institute, Inc. Quantitative PCR was performed using Taqman site-specific primers and probes (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 7300 Real time PCR System. Results were normalized to β-2 microglobulin levels. For relative comparisons samples are compared to non-stimulated (NS) culture conditions for mouse IL-10 that was assigned an arbitrary value of one unless otherwise described.

In Vivo LPS Challenge.

In survival studies, age and gender-matched mice were challenged in vivo with 50 μg/mouse of LPS (List Biologicals) by i.p. injection. For target gene analysis studies mice received 500 μg/mouse i.p. The E. coli-derived LPS (0111:B4) used for in vivo studies has been re-extracted to ensure that it is devoid of potentially contributory TLR2 contaminants.

Parasites.

L. donovani amastigotes (LV9) were isolated from infected RAG−/− (B6.129S7-Rag/tm/Mom/J) mice as previously described (21). Mice were infected with 2 × 107 amastigotes by the lateral tail vein. Hepatic and splenic parasite burdens were determined by examining methanol-fixed, Giemsa stained tissue impression smears. Data are presented as Leishmania donovani Units (LDU).

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software. A two-tailed, paired Student's t test was used to determine statistically significant differences among groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. John O'Shea for his support and careful review of this manuscript, Dr. Fidel Zavala and Bob Bean for helpful discussions, and Dr. Mark Kaplan for providing Stat4−/− mice; Paul Fallon and the Becton Dickinson Immune Function Laboratory for flow cytometry assistance; and Anitha Moorthy for technical assistance. This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) Research Fellowship HE 5507/1-1 (to C.M.H.) and National Institutes of Health Grant 5R01AI070594-02 to (to J.H.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 16895.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0904955106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Li MO, Flavell RA. Contextual regulation of inflammation: A duet by transforming growth factor-beta and interleukin-10. Immunity. 2008;28:468–476. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore KW, De Waal MR, Coffman RL, O'Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Garra A, Vieira P. T(H)1 cells control themselves by producing interleukin-10. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:425–428. doi: 10.1038/nri2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roers A, et al. T cell-specific inactivation of the interleukin 10 gene in mice results in enhanced T cell responses but normal innate responses to lipopolysaccharide or skin irritation. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1289–1297. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubtsov YP, et al. Regulatory T cell-derived interleukin-10 limits inflammation at environmental interfaces. Immunity. 2008;28:546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miles SA, Conrad SM, Alves RG, Jeronimo SM, Mosser DM. A role for IgG immune complexes during infection with the intracellular pathogen Leishmania. J Exp Med. 2005;201:747–754. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nylen S, Sacks D. Interleukin-10 and the pathogenesis of human visceral leishmaniasis. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy ML, Wille U, Villegas EN, Hunter CA, Farrell JP. IL-10 mediates susceptibility to Leishmania donovani infection. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2848–2856. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2001010)31:10<2848::aid-immu2848>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghalib HW, et al. Interleukin 10 production correlates with pathology in human Leishmania donovani infections. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:324–329. doi: 10.1172/JCI116570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belkaid Y, Piccirillo CA, Mendez S, Shevach EM, Sacks DL. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control Leishmania major persistence and immunity. Nature. 2002;420:502–507. doi: 10.1038/nature01152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siewe L, et al. Interleukin-10 derived from macrophages and/or neutrophils regulates the inflammatory response to LPS but not the response to CpG DNA. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:3248–3255. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg DJ, et al. Interleukin-10 is a central regulator of the response to LPS in murine models of endotoxic shock and the Shwartzman reaction but not endotoxin tolerance. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2339–2347. doi: 10.1172/JCI118290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pajkrt D, et al. Attenuation of proinflammatory response by recombinant human IL-10 in human endotoxemia: Effect of timing of recombinant human IL-10 administration. J Immunol. 1997;158:3971–3977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandtzaeg P, et al. Net inflammatory capacity of human septic shock plasma evaluated by a monocyte-based target cell assay: Identification of interleukin-10 as a major functional deactivator of human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1996;184:51–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sparwasser T, Eberl G. BAC to immunology–bacterial artificial chromosome-mediated transgenesis for targeting of immune cells. Immunology. 2007;121:308–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liao YC, et al. IL-19 induces production of IL-6 and TNF-alpha and results in cell apoptosis through TNF-alpha. J Immunol. 2002;169:4288–4297. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grant LR, et al. Stat4-dependent, T-bet-independent regulation of IL-10 in NK cells. Genes Immun. 2008;9:316–327. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsuji-Takayama K, et al. The production of IL-10 by human regulatory T cells is enhanced by IL-2 through a STAT5-responsive intronic enhancer in the IL-10 locus. J Immunol. 2008;181:3897–3905. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolk K, Kunz S, Asadullah K, Sabat R. Cutting edge: Immune cells as sources and targets of the IL-10 family members? J Immunol. 2002;168:5397–5402. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell MJ, Thompson SA, Tone Y, Waldmann H, Tone M. Posttranscriptional regulation of IL-10 gene expression through sequences in the 3′-untranslated region. J Immunol. 2000;165:292–296. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stager S, et al. Distinct roles for IL-6 and IL-12p40 in mediating protection against Leishmania donovani and the expansion of IL-10+ CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:1764–1771. doi: 10.1002/eji.200635937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stumhofer JS, et al. Interleukins 27 and 6 induce STAT3-mediated T cell production of interleukin 10. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1363–1371. doi: 10.1038/ni1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mormann M, et al. Mosaics of gene variations in the Interleukin-10 gene promoter affect interleukin-10 production depending on the stimulation used. Genes Immun. 2004;5:246–255. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eskdale J, et al. Interleukin-10 microsatellite polymorphisms and IL-10 locus alleles in rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility. Lancet. 1998;352:1282–1283. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70489-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heintz N. BAC to the future: The use of bac transgenic mice for neuroscience research. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:861–870. doi: 10.1038/35104049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giraldo P, Montoliu L. Size matters: Use of YACs, BACs, and PACs in transgenic animals. Transgenic Res. 2001;10:83–103. doi: 10.1023/a:1008918913249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonifer C, Vidal M, Grosveld F, Sippel AE. Tissue specific and position independent expression of the complete gene domain for chicken lysozyme in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 1990;9:2843–2848. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welstead GG, et al. Measles virus replication in lymphatic cells and organs of CD150 (SLAM) transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16415–16420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505945102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frazer KA, Narla G, Zhang JL, Rubin EM. The apolipoprotein(a) gene is regulated by sex hormones and acute-phase inducers in YAC transgenic mice. Nat Genet. 1995;9:424–431. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Q, Peterson KR, Fang X, Stamatoyannopoulos G. Locus control regions. Blood. 2002;100:3077–3086. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurkjian KM, et al. Multiplex analysis of circulating cytokines in the sera of patients with different clinical forms of visceral leishmaniasis. Cytometry A. 2006;69:353–358. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nylen S, et al. Splenic accumulation of IL-10 mRNA in T cells distinct from CD4+CD25+ (Foxp3) regulatory T cells in human visceral leishmaniasis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:805–817. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganguly S, et al. Increased levels of interleukin-10 and IgG3 are hallmarks of Indian post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1762–1771. doi: 10.1086/588387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson MD, et al. Species-specific transcription in mice carrying human chromosome 21. Science. 2008;322:434–438. doi: 10.1126/science.1160930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Z, Tato CM, Muul L, Laurence A, O'Shea JJ. Distinct regulation of interleukin-17 in human T helper lymphocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2936–2946. doi: 10.1002/art.22866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vicari AP, Trinchieri G. Interleukin-10 in viral diseases and cancer: Exiting the labyrinth? Immunol Rev. 2004;202:223–236. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reuss E, et al. Differential regulation of interleukin-10 production by genetic and environmental factors–a twin study. Genes Immun. 2002;3:407–413. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salhi A, et al. Immunological and genetic evidence for a crucial role of IL-10 in cutaneous lesions in humans infected with Leishmania braziliensis. J Immunol. 2008;180:6139–6148. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin HD, et al. Genetic restriction of HIV-1 pathogenesis to AIDS by promoter alleles of IL-10. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14467–14472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bream JH, Ping A, Zhang X, Winkler C, Young HA. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the proximal IFN-gamma promoter alters control of gene transcription. Genes Immun. 2002;3:165–169. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.