Abstract

Purpose

While quality of life for most breast cancer survivors (BCS) returns to normal by one year post-treatment, problems in sexual function and intimacy often persist. The present study tested the efficacy of a 6-week psycho-educational group intervention in improving BCS’s sexual well-being.

Methods

We conducted a mailed survey of BCS 1–5 years post-diagnosis to identify a sample of women who reported moderately severe problems in body image, sexual function or partner communication, and were deemed eligible for the randomized intervention trial. Using a pre-randomized design, 70% were assigned to a 6 week psycho-educational group intervention and 30% were assigned to a control condition (print material only).

Results

There were 411 eligible participants, of whom 284 were randomized to the intervention and 127 to the control condition; however, only 83 BCS agreed to participate in the intervention. Four months post-intervention, the intervention and control groups were not significantly different on the primary outcome of emotional functioning; however, BCS randomized to the intervention group were more likely to report improvements in relationship adjustment and communication as well as increased satisfaction with sex than controls. Members of the intervention group who were the least satisfied with their sexual relationship appeared to improve the most.

Conclusions

Although modest in its effects, this intervention can be delivered in standard clinical settings. Having an identified treatment may help reduce physician reluctance to ask BCS about problems in intimacy and as appropriate, refer them for timely help.

Keywords: Body image, Breast cancer, Partner communication, Sexuality, Survivor

Introduction

Advances in the treatment of cancer have increased the number of cancer survivors, estimated to be more than 12 million individuals in the United States (U.S.) today [1]. This is nowhere more apparent than in the case of breast cancer, where mortality rates have been declining steadily since the 1990s. There are estimated to be over 2.4 million breast cancer survivors (BCS) in the U.S. alone [1]. However, these advances have come with long-term and late effects. More women than in the past are exposed to complex, multimodal treatments (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy) and multi-drug regimens, many of which also involve years of adjuvant endocrine therapy. As women live longer following the diagnosis of breast cancer, attention to the adverse chronic and potential late effects of treatment has grown. Clinicians and researchers are learning from this population that being declared disease-free does not mean a woman is free of her disease.

A growing literature describes a wide range of disruptions in day-to-day living as a result of a breast cancer diagnosis [2]. Fortunately, many of these cancer-related problems eventually resolve [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. However, data from studies among longer-term breast cancer survivors show that sexual problems occur with considerable frequency and often do not resolve over time [8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13], even among women who do not undergo mastectomy [8, 9, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18] or who have subsequent breast reconstruction [19, 20].

A diagnosis of breast cancer can negatively affect both medical and psychosocial aspects of sexuality [21]. Among perimenopausal women, chemotherapy can induce premature and sudden menopause, with concomitant symptoms that often interfere with sexual functioning, such as hot flashes, vaginal dryness and sleep disturbance [22, 23]. Furthermore, the frequently used adjuvant endocrine therapies, including both tamoxifen and the newer aromatase inhibitors, can exacerbate these effects. Psychological reactions to cancer also can threaten sexual functioning, through disturbances of mood and body image and the disintegration of established patterns of achieving physical pleasure and intimacy [24, 25]. Changes in partner communication and responsiveness also are associated with post-diagnostic sexuality and intimacy among women with breast cancer [26, 27]. All of these factors can affect sexual response in the breast cancer survivor.

Despite the prevalence and documented persistence of sexuality and intimacy problems among large numbers of breast cancer survivors, few interventions have been developed specifically to address these issues [28, 29]. Most have focused on helping women adjust to global changes in their lives or on acquiring generic, illness-related coping skills and have not been specifically designed for delivery following cancer treatment [30]. Our work examining predictors of sexual well-being among women after breast cancer identified several modifiable psychosocial variables that lend themselves to intervention and that predict a sizeable proportion of variance in sexual health; these include vaginal dryness, emotional well-being, body image, relationship quality, and the presence of sexual problems in one’s partner [31]. Using this information, the current study was designed as a randomized controlled trial to test the efficacy of an intervention that focused on sexuality and intimacy and on factors likely to influence them. Intervention targets for this study were classified into three general, higher-order categories: emotional distress, sexual functioning and relationship functioning. We hypothesized that women randomized to the intervention arm of this study would experience greater improvement in their emotional well-being as well as body image, comfort and satisfaction with sexual functioning and partner communication than women randomized to the control group.

Methods

Overview

This randomized psycho-educational intervention trial was embedded within a larger program of research focused on understanding sexuality and intimacy in breast cancer survivors, through a preliminary survey study in Los Angeles and Washington DC [16, 17, 31, 32]. After the preliminary descriptive research, a randomized trial designed to test the efficacy of a psycho-educational group intervention was planned to help address the needs and concerns of BCS with persistent difficulties with sexuality and intimacy. A second large survey study was conducted to identify participants for the intervention study. The subset of survey respondents who reported problems with body image, sexuality and intimacy, and/or communication with a partner was approached about participating in a two-arm randomized study. At the time of consent for the survey, women were informed that they might be invited to participate in an intervention program in the future. Subsequently, those found to meet criteria for study eligibility (see below) were randomly assigned to the intervention or control condition. Those assigned to the intervention condition were invited to participate in a 6-week psycho-educational group program, and those randomized to the control condition received the educational pamphlet, “Facing Forward: A Guide for Cancer Survivors” (National Cancer Institute, 1994). Follow-up data were collected from participants through mailed survey questionnaires that were sent four months after the completion of the group program for women randomized to the intervention arm, or at an equivalent time point for women in the control arm; all women were mailed a post-intervention survey, whether or not they actually participated in the group intervention. Institutional review board approval was obtained at all institutions participating in the study.

Eligibility and randomization

The research was conducted in two large metropolitan areas (Los Angeles and Washington, D.C.). Patient selection and recruitment are described in detail elsewhere [16, 31, 32]. In brief, participants were identified and recruited through tumor registry listings, the offices of surgeons and medical or radiation oncologists, and from hospital or clinic logs from a variety of clinical environments (NCI-designated Cancer Centers, staff model HMO’s, and private community hospitals) between January 1996 and June 1997. Eligibility criteria included a diagnosis of stage 0–II breast cancer one to five years earlier, completion of all cancer therapy save tamoxifen, current disease-free status, no prior cancer history other than non-invasive skin or cervical cancer, absence of severe or disabling psychiatric or major medical illness, and English proficiency. All participants completed a baseline mailed survey that assessed cancer history, psychological distress, body image, marital satisfaction, sexual functioning, and other variables unrelated to the present study.

Patients were ineligible for the intervention study if they were geographically inaccessible, severely depressed or in a very poorly functioning partnered relationship based on the mailed survey measures (see below). For the remaining women, eligibility for the intervention was based on the severity of problems related to partner relationship and sexual functioning, as we wished to target those women who were having persistent difficulties. The specific measures and thresholds for eligibility are detailed below. We used a pre-randomized stratified design to assign those meeting the eligibility criteria to intervention (70%) or control (30%). Strata included age (50 years and older versus younger) and partner status (partnered versus unpartnered) Randomization was centrally coordinated through the UCLA statistical office which notified each site of participant assignment. Women allocated to the intervention arm were contacted by letter from the UCLA or Georgetown site and then by telephone to invite them to participate in the group sessions. Those who were interested were assigned to a group at a convenient time and place. Thirteen groups were convened at seven locations in the Los Angeles and Washington, D.C. areas. Controls were sent mailings (the educational pamphlet Facing Forward) timed to coincide with the start of intervention sessions.

Measures

Survey instruments were used both to identify individuals who stood to benefit from a psychosocial intervention and to assess study outcomes. Key variables were measured as follows.

Selection criteria measures

While most intervention studies in the cancer field include participants regardless of level of distress, our intervention was targeted to BCS who reported some difficulty related to sexuality or intimacy, with the exclusions noted earlier for severe depression and significantly distressed partner relationships. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) was administered to screen out participants with significant depression whose needs might be too great for a psycho-educational group. This 20-item self-report scale was designed to measure depressive symptoms in the general population [33]. It is most often used as a screening device for clinical depression, with participants scoring below 16 unlikely to have clinically significant depression [34, 35]. This was the cutoff score used in the present study.

Overall relationship adjustment was measured with the 14-item Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale (RDAS) [36, 37]. This version of the widely-used measure of relationship functioning yields an overall adjustment score, as well as subscale scores for satisfaction, consensus, and cohesion. Overall scores can range from 0 to 69, with a mean for married couples of 48.0 (SD=9.0) [36], where low scores indicate distressed marriages. A cutoff score of < 41 was used to screen out women in poorly functioning relationships (41.6 being the mean reported among women in distressed relationships in the Busby sample).

The Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System (CARES) yielded measures of sexual dysfunction, body image, and affection and communication with a partner. This self-administered measure has excellent reliability, validity, and psychometric properties [38], and extensive normative data are available in breast cancer patients [10, 16, 39, 40]. On the CARES, participants respond to problem statements by selecting a response from a 5-point scale anchored by 0=“Does not apply” to 4=“Applies very much” during the past month. Higher scores indicate greater disruption in quality of life. The instrument yields a number of scale and subscale scores; distress levels indicating appropriateness for randomization were a Sexual Summary score greater than 0.5, or a Marital Communication, Marital Affection, Body Image, or Dating scale score greater than 2.0. These cut-points were derived from prior research with the CARES [10].

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the 32-item Mental Health Index (MHI-32) from the Medical Outcomes Study [41]. On this generic measure of mental health, participants rate the degree to which they have experienced various feeling states over the past month in the domains of anxiety, depression, loneliness, distress, well-being, and positive affect. Items are scored and summed to yield an overall mental health score, with higher scores indicating better mental health. Data document the high internal consistency and validity of this measure [41]. Secondary outcomes included eight Likert-scaled items to measure sexual outcomes including sexual satisfaction, sexual pain (because treatments for breast cancer can cause vaginal symptoms) and comfort with sexual situations (Table 1, items 1–8); a measure of overall subjective impact of breast cancer on sexuality (Table 1, item 9). Secondary outcomes pertaining to relationship functioning included overall relationship adjustment as measured by the 14-item RDAS and a single item asking participants to rate the degree to which communication with their partner had improved since baseline (Table 1, item 10). These measures were applicable only to women who had partners. On all items, higher scores indicate better outcomes.

Table 1.

Outcome items designed for the study

| Sexual outcomes |

|---|

|

| Relationship outcomes |

|

Intervention design

The intervention was derived from our conceptual model of the development of sexual dysfunction in breast cancer survivors [31]. Intervention plans were subjected to focus group scrutiny and pilot testing at both research sites. The final intervention program consisted of six weekly two-hour group meetings. The general content of each session is depicted in Table 2. The program aimed to improve satisfaction with sexual functioning and intimate relationships by (1) providing information, (2) enhancing communication skills, and (3) reducing anxiety in intimate situations. Although sex therapy-based techniques for couples are available for addressing partner sexual difficulties, we aimed to design an intervention that would be useful both to partnered and unpartnered BCS. Therefore we focused our intervention efforts on the individual BCS, rather than the BCS and her partner. Each session included an educational component, a communication-training component, and a sex therapy-related component derived from the general principles of sensate focus therapy [42]. Meetings drew upon a manual for group members that included educational material, homework assignments, and community resources. Additional detail regarding the intervention is available from the authors.

Table 2.

Intervention content

| Session Aims | Offer support |

| Provide information | |

| Reduce anxiety | |

| Identify and work toward goals | |

| Session Structure | Review of homework from prior week |

| Structured educational module led by group leader | |

| Unstructured group discussion of current session’s topic(s) | |

| Introduction of new homework exercise | |

| Content by session | I: Introduction: Orienting Members & Building Rapport |

| II: Body Image & Sexual Anatomy | |

| III: Sexual Attitudes & Behaviors; Menopause | |

| IV: Sexual Functioning; Communication Skills | |

| V: Sexual Dysfunctions; Sexual Enhancement | |

| VI: Conclusions; Goals for the Future |

To ensure quality control, investigators reviewed audiotapes of a subset of the sessions and regularly spoke to and met with group leaders at each site (DC, LA). Group leaders completed brief summary forms after each session that included ratings of the degree to which manual content was covered during the session. Group members completed anonymous group and leader evaluations at the close of the final session.

Four group leaders at each site were recruited by word-of-mouth and advertisements in a professional newsletter for oncology social workers. Leaders were licensed medical social workers, all of whom worked in medical settings. All leaders had experience running groups and had expertise in cancer and/or sexuality. These mental health professionals were chosen as group leaders because these are the professionals most likely to be running such psycho-educational groups in typical hospital or community settings, which would be relevant for subsequent dissemination of an effective intervention.

One-day leader training sessions were conducted at both sites, led by a single investigator (B.M.) to ensure standardization. These sessions included lectures on breast cancer and sexuality, a discussion of group issues with cancer survivors, and a session-by-session discussion of the manual and session contents. Group leaders received a leaders’ version of the intervention manual that included information about key themes to be covered in discussions, suggestions for how to stimulate discussion, and instructions regarding the approximate length of time to spend on each task. Groups were run between June 1996 and July 1997.

Statistical analysis

In the statistical analyses, we defined receipt of (or participation in) the intervention as attendance of one or more sessions.

As with all intervention studies and more frequently seen with pre-randomized designs, imperfect uptake among women allocated to the intervention and loss to follow-up in both arms created the potential for bias. To evaluate the potential for bias, we conducted comparisons (i) between the intervention and control groups as randomized; (ii) between intervention assignees who received the intervention and those who did not; (iii) between completers and noncompleters at follow-up, in the intervention and control groups separately; (iv) among the three groups of completers defined by control, intervention receipt and intervention nonreceipt. These comparisons consisted of significance tests (chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests or ANOVA for continuous variables) for differences in demographic characteristics, surgery type, chemotherapy status, CES-D, the CARES screening variables and the outcome variables as measured at baseline. Imbalances across groups were controlled in outcome analyses by including the relevant covariates in those analyses.

We evaluated change from baseline to follow-up within groups defined by intervention receipt, intervention nonreceipt and the control condition using paired t-tests. We compared outcomes across the intervention and control conditions using an intent-to-treat analysis comparing women randomized to the intervention to those randomized to control. As exploratory analyses, we also conducted an “as-treated” analysis comparing those who received the intervention with those who did not receive it (grouping women who were randomized to the intervention but did not receive it with the controls); a “per-protocol” analysis comparing intervention-arm women who received the intervention with women in the control group (dropping women randomized to the intervention who did not receive it); and a “complier average causal effect” or CACE analysis. CACE analysis accounts for participation rates among individuals assigned to the intervention and, based on a mixture-model estimation procedure, seeks to compare intervention receivers to individuals in the control group who would have participated in the intervention if offered it [43, 44]. This approach attempts to estimate the effect of the intervention on individuals who are willing and able to receive it.

The intent-to-treat, as-treated, and per-protocol analyses were conducted using least squares regression with the SAS GLM procedure. The CACE analysis was conducted in Stata using the gllamm command and the methods described in Skrondal and Rabe-Hesketh (pp. 427–432) [45]. All analyses included those individuals for whom the variables of interest were not missing. For outcome variables measured only at follow-up (improved comfort with sex and improved communication with partner), follow-up scores were the dependent variable. For outcome variables measured at both baseline and follow-up, we used change scores as the dependent variable in an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model that included a treatment group indicator, baseline score and baseline score × treatment group interaction as predictors. If the interaction term was significant (P < 0.05), this constituted the final model. If the interaction term was not significant, this term was dropped and the reduced model constituted the final model. Covariates (age and employment status) were included in the models to adjust for imbalances between groups at baseline.

To adjust for multiple comparisons, we bounded the false discovery rate within each set of outcomes (primary, secondary: sexual and secondary: relationship) at 0.05 using the Benjamini and Hochberg procedure [46].

Results

Study participation

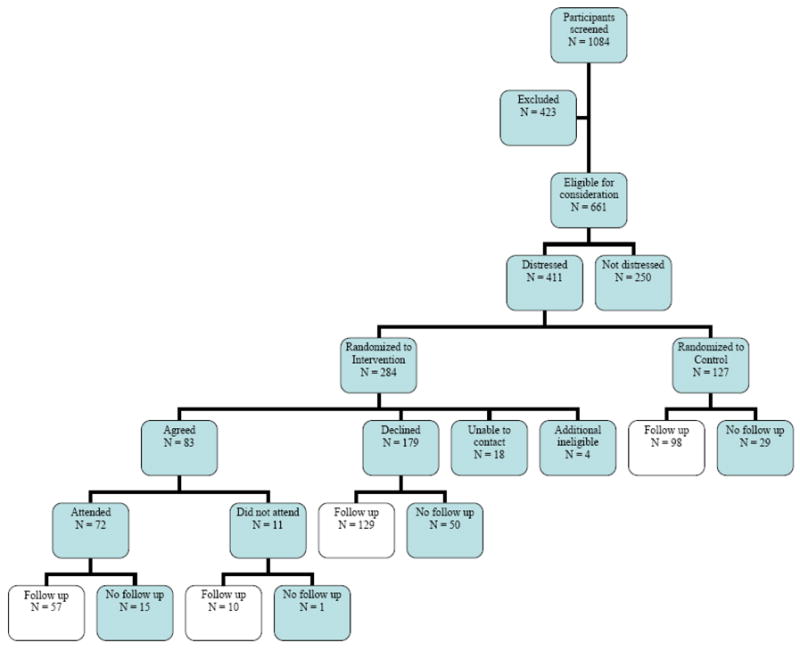

Figure 1 presents participant flow through the study. Thirty-nine percent (N = 423) of the 1,084 patients returning baseline questionnaires were screened out, 23% (N = 253) because of depression, 8% (N = 88) because of a poor partner relationship, and 7% (N = 76) because of geographic location. Of the remaining 661 women, 38% (N = 250) did not meet the distress level thresholds and were also excluded from randomization. Of the 411 eligible women, 284 were randomized to the intervention and 127 to the control condition.

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram

Only 29% (N = 83) of the women randomized to the intervention agreed to participate. Among those who declined participation, the primary reasons given included the inconvenience of the time or location of the sessions being offered (N = 52, 29%), the participant’s perception that she was not distressed and didn’t need the intervention (N = 46, 26%), and being too busy (N = 39, 22%). Other reasons included disliking groups or the topic. There were 18 patients who were unreachable and an additional 4 who were contacted but then proved ineligible for the study.

Seventy-two of the 83 women who agreed to participate actually attended at least one session; the remaining 11 never attended. Follow-up questionnaires were returned by 57 (79%) intervention participants, 98 (77%) control participants, and 139 (73%) intervention nonparticipants.

Characteristics of the study sample

Characteristics of the study sample by assigned group are provided in Table 3. The average age at baseline for the combined study sample was 57 years (range 35 to 86 years). All women were between 1.0 and 5.5 years since diagnosis, with the exception of one woman, an intervention non-participant, who was 10 months since diagnosis. This woman had received a lumpectomy and no chemotherapy. Most of the women had received a lumpectomy rather than mastectomy (60%, N=235) and most had not received chemotherapy (55%, N=216). The majority were white (83%, N=328) and reported household incomes above $60,000 per year (58%, N=221). There were no significant differences between the intervention and control groups as randomized on demographic, clinical or treatment characteristics or on the outcome variables at baseline, with the exception of the self-reported impact of cancer on sex life, which was more negative in the control group (P = 0.035). Baseline values of each outcome variable were included as control variables in the ANCOVA models for the outcome analyses.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the study sample at baseline

| Control group (n = 127) | Intervention group (n = 280)a | Intervention participants (n = 72) | Intervention nonparticipants (n = 208) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Range | Range | Range | Range | |

| Age (years) | 56.1 (10.3) | 57.1 (10.6) | 53.4 (9.2) | 58.4 (10.8)*** |

| 35–81 | 35–86 | 37–81 | 35–86 | |

| Years since diagnosis | 3.0 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.1) | 2.8 (1.1) | 2.8 (1.1) |

| 1.0–5.5 | 0.8–5.2 | 1.0–4.8 | 0.8–5.2 | |

| CESD | 6.7 (4.5) | 7.0 (4.6) | 7.2 (4.7) | 6.9 (4.6) |

| 0–16 | 0–16 | 0–16 | 0–16 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Anglo-American | 106 (84) | 222 (83) | 56 (79) | 164 (85) |

| African-American | 12 (10) | 28 (10) | 7 (10) | 20 (10) |

| Other | 8 (6) | 18 (7) | 8 (11) | 10 (5) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married, living w/husband | 89 (71) | 209 (78) | 52 (73) | 156 (80) |

| Divorced/separated | 19 (15) | 32 (12) | 13 (18) | 17 (9) |

| Widowed | 9 (7) | 15 (6) | 3 (4) | 12 (6) |

| Single | 9 (7) | 12 (4) | 3 (4) | 9 (5) |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 17 (13) | 41 (15) | 9 (13) | 32 (16) |

| Some college | 45 (36) | 96 (36) | 22 (31) | 72 (37) |

| College degree | 21 (17) | 43 (16) | 11 (15) | 32 (16) |

| Post-graduate | 43 (34) | 88 (33) | 29 (41) | 58 (30) |

| Employment | ||||

| Employed full-time | 55 (44) | 112 (42) | 43 (61) | 67 (35) *** |

| Employed part-time | 18 (14) | 45 (17) | 12 (17) | 33 (17) |

| Retired | 28 (22) | 66 (25) | 10 (14) | 55 (28) |

| Other (e.g. disabled) | 25 (20) | 45 (17) | 6 (8) | 39 (20) |

| Household annual income | ||||

| $60,000 or less | 52 (43) | 105 (41) | 27 (40) | 76 (41) |

| More than $60,000 | 70 (57) | 151 (59) | 41 (60) | 109 (59) |

| Type of surgery | ||||

| Lumpectomy | 71 (56) | 164 (61) | 43 (61) | 119 (61) |

| Mastectomy only | 34 (27) | 65 (24) | 15 (21) | 50 (26) |

| Mastectomy + reconstruction | 21 (17) | 39 (15) | 13 (18) | 25 (13) |

| Received chemotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 61 (48) | 117 (44) | 34 (48) | 116 (60) |

| No | 65 (52) | 151 (56) | 37 (52) | 78 (40) |

| Baseline values of outcome variables | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Mental Health Index-32 | 82.1 (8.9) | 81.9 (9.5) | 80.4 (11.6) | 82.4 (8.6) |

| Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale | 50.8 (5.5) | 51.1 (5.5) | 50.4 (5.6) | 51.3 (5.4) |

| Satisfaction w/variety of sex | 4.0 (1.0) | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.0 (1.1) | 4.3 (0.9) |

| Satisfaction with sexual relationship | 4.7 (1.4) | 4.8 (1.3) | 4.6 (1.3) | 4.8 (1.3) |

| Pain with sex | 4.3 (1.8) | 4.1 (1.8) | 4.0 (2.0) | 4.2 (1.8) |

| Pain interfering w/pleasure | 4.6 (1.6) | 4.6 (1.6) | 4.5 (1.7) | 4.7 (1.6) |

| Comfort being touched | 4.3 (1.7) | 4.4 (1.6) | 4.5 (1.7) | 4.4 (1.6) |

| Comfort undressing | 5.1 (1.6) | 4.9 (1.6) | 4.6 (1.8) | 5.0 (1.5) |

| Comfort being nude | 5.3 (1.5) | 5.3 (1.4) | 5.2 (1.5) | 5.3 (1.3) |

| Cancer’s impact on sex life | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.6 (0.8)* | 2.6 (0.9) | 2.7 (0.8) |

Significance tests comparing the control and intervention groups as randomized and intervention participants and nonparticipants were conducted using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables.

Of the 284 women randomized to the intervention condition, four were found to be ineligible, reducing the number to 280.

0.01 < P < 0.05 for difference between control and intervention groups as randomized

P < 0.001 for difference between intervention participants and nonparticipants

Within the group randomized to intervention, women who participated in the sessions were younger (P < 0.001) and more likely to be employed (P < 0.001) than nonparticipants (Table 3); however, no differences were found between these two groups on the outcome variables at baseline. Age and employment status were included in outcome analyses as control variables.

Comparison of women who completed the four-month follow-up questionnaire with those who did not on baseline characteristics found no differences between completers and non-completers among those assigned to the intervention (data not shown). Among women assigned to the control condition, women lost to follow-up reported less pain interfering with pleasure (P = 0.023), less comfort being touched (P = 0.002), and greater disruption as measured by marital affection score (P = 0.042) at baseline compared to women who returned follow-up questionnaires.

Baseline scores on outcome variables among the women who completed the follow-up questionnaire are presented in Table 4. No baseline differences were found among intervention participants, intervention nonparticipants and controls completing follow-up with the exception of satisfaction with variety of sex, which was highest among intervention nonparticipants (P = 0.020).

Table 4.

Unadjusted mean baseline and change scores on outcome variables for participants completing the four-month follow-up survey

| A. Intervention participants n = 57 | B. Intervention nonparticipants n = 139 | C. Controls n = 98 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variablea | Baseline (SD) | Baseline (SD) | Baseline (SD) |

| Change (SD) | Change (SD) | Change (SD) | |

| Primary outcome | |||

| Mental Health Index-32 | 80.8 (11.6) | 82.4 (8.9) | 82.6 (9.2) |

| −0.7 (10.4) | −2.7 (10.5)** | −3.8 (9.4)*** | |

| Secondary outcomes: sexual | |||

| Satisfaction with variety of sex | 4.0 (1.1) | 4.4 (0.8)* | 4.0 (1.0) |

| 0.1 (1.2) | −0.2 (0.9) | −0.03 (1.0) | |

| Satisfaction with sexual relationship | 4.8 (1.1) | 4.9 (1.3) | 4.7 (1.4) |

| 0.0 (1.5) | 0.1 (1.4) | −0.3 (1.3)* | |

| Pain with sex | 3.8 (2.0) | 4.2 (1.9) | 4.1 (1.9) |

| 0.7 (1.9) * | 0.2 (1.5) | −0.1 (1.7) | |

| Pain interfering with pleasure | 4.4 (1.7) | 4.7 (1.7) | 4.4 (1.7) |

| 0.3 (1.4) | 0.1 (1.2) | 0.0 (1.1) | |

| Improved comfort with sexualityb | 3.3 (0.6) | 3.1 (0.6) | 3.1 (0.6) |

| Comfort being touched | 4.7 (1.6) | 4.4 (1.6) | 4.6 (1.6) |

| 0.1 (1.4) | 0.3 (1.2)* | −0.1 (1.2) | |

| Comfort undressing | 4.7 (1.7) | 4.9 (1.5) | 5.0 (1.5) |

| 0.2 (1.9) | 0.1 (1.2) | −0.2 (1.8) | |

| Comfort being nude | 5.3 (1.4) | 5.2 (1.5) | 5.2 (1.4) |

| 0.3 (1.3) | 0.1 (1.6) | −0.1 (1.6) | |

| Cancer’s impact on sex life | 2.6 (1.0) | 2.7 (0.8) | 2.4 (1.0) |

| 0.1 (0.8) | 0.04 (0.8) | 0.2 (0.9) | |

| Secondary outcomes: relationship | |||

| Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale | 50.9 (5.7) | 51.2 (5.3) | 51.0 (5.6) |

| 1.1 (4.0) | −0.3 (4.7) | −1.3 (4.6)* | |

| Improved communicationb | 3.5 (0.7) | 3.3 (0.7) | 3.2 (0.7) |

Comparisons of mean baseline scores among the three groups were conducted using analysis of variance. Comparisons of baseline and follow-up scores within each of the three groups were conducted using paired t-tests on change scores.

For all measures, higher scores correspond to better outcomes.

Measured at follow-up only; follow-up scores reported.

0.01 < P < 0.05

0.001 < P < 0.01

P < 0.001

Outcome analyses

Table 4 provides change scores from baseline to follow-up for outcome variables within three groups defined by intervention participation, intervention nonparticipation and control condition. MHI-32 scores declined significantly from baseline to follow-up for intervention nonparticipants (P = 0.003) and control women (P < 0.001); no change was found among intervention participants. Intervention participants reported a decline in pain with sex (P = 0.023), and intervention nonparticipants reported an increase in comfort being touched (P = 0.026). Control group women reported a decline in satisfaction with sex (P = 0.042) and a decline in RDAS (P = 0.018).

Table 5 reports the results of outcome analyses adjusting for baseline score (where applicable), age and employment status (working vs. not working), the latter two variables being included due to imbalances at baseline. The intent-to-treat analysis did not find a significant intervention effect on the primary outcome, MHI-32. The as-treated analysis suggested an improvement on this measure as well as a baseline-by-treatment interaction indicating greater improvement in more distressed women.

Table 5.

Group comparisons using intent-to-treat, as-treated, per-protocol, and complier average causal effect (CACE) approaches: P values for main effects and baseline-treatment interactionsa

| Analytic approach | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intent-to-treatb | As-treatedc | Per-protocold | CACEe | |

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Mental Health Index-32 | 0.244 | 0.025/0.037* | 0.118 | 0.268 |

| Secondary outcomes: sexual | ||||

| Satisfaction w/variety of sex | 0.478 | 0.329 | 0.226 | 0.491 |

| Satisfaction w/sexual relationship | 0.002/0.012* | 0.328 | 0.017/0.044 | <0.001* |

| Pain with sex | 0.057 | 0.084 | 0.090 | 0.876 |

| Pain interfering with pleasure | 0.214 | 0.291 | 0.286 | 0.689 |

| Improved comfort with sexuality | 0.128 | 0.020 | 0.025 | 0.100 |

| Comfort being touched | 0.099 | 0.766 | 0.315 | 0.051 |

| Comfort undressing | 0.355 | 0.570 | 0.590 | <0.001* |

| Comfort being nude | 0.234 | 0.171 | 0.138 | <0.001* |

| Cancer’s impact on sex life | 0.897 | 0.899 | 0.785 | 0.116 |

| Secondary outcomes: relationship | ||||

| Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale | 0.052 | 0.024* | 0.017* | 0.009* |

| Improved communication w/partner | 0.042 | 0.024* | 0.012* | 0.022* |

Adjusted for age, employment status (working vs. not) and baseline value of variable. Where two P-values are presented, the second reports a significant baseline-treatment interaction, indicating a differential effect of treatment depending on the baseline value of the variable.

Intent-to-treat analysis compares women randomized to the intervention (A + B in Table 4) to controls (C).

As-treated analysis compares those who participated in the intervention (A) to those who did not receive it (B + C).

Per-protocol analysis compares women who received the intervention (A) to controls (C).

Complier average causal effect (CACE) analysis compares women who received the intervention to a subgroup of the control women who are estimated to have been likely to participate in it if offered.

Results found to be significant after controlling the familywise error rate within each set of outcomes (primary, secondary: sexual and secondary: relationship) at 0.05.

The intent-to-treat analysis as well as the other analytic approaches found an intervention effect for the two relationship outcome measures; the intent-to-treat finding was not significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons, however. Further exploratory analyses with the RDAS revealed that higher levels of functioning of the intervention group on this measure were attributable principally to scores on the subscale assessing general marital satisfaction (P = 0.044, 0.055, 0.052, <0.001 for intent-to-treat, as-treated, per-protocol and CACE, respectively). There was less evidence for an effect on the cohesion subscale (P = 0.059, 0.179, 0.078, 0.002), and no significant differences on the consensus subscale (all P > 0.10).

For sexual outcomes, the intent-to-treat analysis as well as the per-protocol and CACE analyses supported an intervention effect on general satisfaction with sex, with women less satisfied at baseline showing greater improvement. Evidence of improved comfort with sex was suggestive in the as-treated and per-protocol analyses but not significant after multiple testing adjustment. Consistent findings were not revealed for specific sexual outcomes, such as variety of sexual activities, sexual pain, and comfort in specific sexual situations, nor for cancer’s impact on sex life. Only the CACE analysis found significant differences in comfort undressing in front of a partner and having sexual activity in the nude, and comfort being touched was near the 0.05 significance level. The divergence of findings across the four analytic methods may be explained by differences in the distributions of change scores for intervention nonparticipants as compared to control group women, leading to results that differ depending on how the individuals are grouped in the analyses.

Participant evaluations

Written evaluations completed by group members revealed that a majority of participants had very positive attitudes toward the group. On anonymous group evaluations, 78% of participants indicated that they had at least partially met the sexuality and intimacy-related goals they had set for themselves during the group and 87% indicated they had set new goals for the future. Almost two-thirds (64%) felt they had experienced at least some improvement in their relationships due to the group, and 59% felt they had experienced at least some improvement in their sexual functioning. Almost all (91%) stated that they would recommend the group to other women in their situation, and the same proportion indicated that they felt the group was worthwhile.

Discussion

The present study is one of the first to test the efficacy of an intervention designed to address persistent problems in body image, sexual function and partner communication among breast cancer survivors following medical treatment for their disease. Although we did not find an effect of the 6-week psycho-educational group intervention on the primary outcome of general mental health using an intent-to-treat analysis, there was evidence to support improvements in relationship adjustment and communication as well as increased satisfaction with sex. These results were observed despite the small sample size for intervention participants. Importantly, members of the intervention group who were the least satisfied with their sexual relationship appeared to improve the most.

Evidence that the intervention improved women’s body image was more equivocal. Only the CACE approach showed a significant effect of the intervention on measures of comfort undressing in front of a partner, having sexual activity in the nude, and comfort being touched. The CACE analysis attempts to compare women who participated in the intervention with those in the control group who would have participated if offered, and hence to estimate the causal effect of the intervention on individuals who are able and willing to participate in the intervention. It could be argued that this analytic approach is especially suitable for psychosocial interventions that can only be delivered to individuals who are favorably inclined, since the comparison attempts to exclude those who would refuse participation and thus never have an opportunity to be exposed to the intervention.

The intervention effects tended to be general rather than specific. For example, while general satisfaction with sex improved, variety of sexual activities, pain on intercourse, and comfort in specific sexual situations did not change significantly as a function of group participation. Similarly, in relationship functioning, general marital satisfaction and overall communication improved but with less impact on cohesion. Nonetheless, this brief intervention was experienced by the majority of cancer survivors as helpful in improving their functioning in these important areas of psychosocial well-being and was well received. An impressive 91% of women indicated they felt the group was worthwhile and would recommend the group to other breast cancer survivors.

Intervention trials are almost always characterized by varying degrees of noncompliance and withdrawal. Drawing valid inferences about intervention efficacy from such trials can be a challenge. Our response to this challenge was to apply multiple analytic strategies, each with its strengths and weaknesses, and to examine the results for consistent findings. An advantage of this approach is that intervention effects that are consistently observed across strategies can be asserted with confidence. In addition to the application of four different analytic methods, there were a number of other design strengths to this study. First, specific treatment-related concerns identified by breast cancer survivors themselves as problematic were targeted for intervention. This is in contrast to the more common approach of improving global functioning or reducing general distress used in many psychosocial and behavioral intervention studies in cancer [e.g., 6, 28, 30]. Second, many prior studies also offered intervention to all patients. Here, we systematically targeted women for inclusion in the intervention arm of the study who reported problems in one or more of the specific domains of interest (body image, sexual function, partner communication) yet at the same time did not have severe problems in other domains (e.g., partner relationship, psychological function). Third, we intentionally designed an intervention protocol that, if found to be successful, could be delivered in most cancer care settings in an effort to maximize its ecologic validity. Hospital-based social workers were successfully recruited and trained with manualized materials to provide the group intervention. These key healthcare practitioners are widely available to survivors in a diversity of cancer settings in the community. Fourth, by providing the intervention to women who had already completed their medical treatments for cancer an average of almost three years earlier, we demonstrated that it is possible to mitigate cancer’s negative impact months or years following completion of medical therapy. All of these modifications serve to address some of the key criticisms around intervention design that have been leveled by the investigator community since this study was launched [30, 47, 48, 49].

There are several important limitations to consider in interpreting the results presented. Key among these is that the sample for this study was relatively homogeneous, composed largely of white, middle class breast cancer survivors who for the most part had many resources available to them, both social and economic. These characteristics limit our ability to generalize study findings to other more diverse groups of breast cancer survivors. As women were only followed up four months after completion of the intervention, it is not known whether the effects of group participation held or might have changed over time. Some bias may also have occurred in outcomes due to the loss of 21–27% of respondents at follow-up. The low intervention participation rate among women invited to participate (27%, 72/262) also points to the conclusion that this intervention can be expected to provide benefits only to a subgroup of cancer survivors.

A number of logistical difficulties were encountered during recruitment. Many women were unwilling to make the time commitment required to attend six two-hour meetings. Moreover, despite the fact that we offered groups at four locations in the Los Angeles area and three in the D.C. area, it was quite difficult to schedule meetings for a time and place that were convenient for all interested women. While the poor participation rate may well have affected study results, it adds a level of external validity to the study. In real-world practice, only individuals who have sufficient time and interest would take part in an intervention offered in their health care settings. This study demonstrates that those BCS who are inclined to participate do in fact benefit from the intervention.

This study has several important clinical implications. As reported in the literature [50] and reflected in testimony collected by the President’s Cancer Panel [51] as well as the Institute of Medicine [52], significant problems in sexual functioning persist post-treatment for large numbers of cancer survivors. Having an identified treatment that helps may serve to increase the likelihood that oncology providers will ask about sexual health, intimacy and partner relationships and women identifying problems in these areas of adaptation will be referred for help. While earlier is usually better, our data also suggest that it is not too late to intervene if problems are seen to persist even months after the end of treatment. In line with the findings of other researchers, survivors who report more problems appear to benefit most from intervention participation [53, 54]. Finding ways to identify and refer for help survivors who are struggling with their illness remains a major challenge to providing quality cancer care. Important in the present study was the finding that we could enhance women’s communication and general satisfaction with her partner without including a partner in the actual intervention. This is reassuring given the fact that a sizeable minority of patients do not have steady partners and that the recruitment challenges that might be expected in trying to deliver this type of group intervention to women with partners are enormous. Finally, although our intervention was relatively brief and modestly effective, it is possible that there may be more efficient ways to deliver this type of help. Growth of interest in online support groups suggests that one direction to consider for the future might be modification of the current intervention for delivery via the Internet. This would certainly help overcome some of the significant logistical barriers to intervention participation identified by women approached for study entry.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Public Health Service grant R01CA63028 to Dr. Ganz from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services and National Institutes of Health grant CA01642 which supported part of Dr. Crespi’s salary. The authors wish to thank Barbara Bass, Pamela W. Black, Bonnie A. Cesak, Romaine Clifton, Karin M. Johnson, Shirley Otis-Greene, Dominica T. Roth, and Deborah S. Kulp for their work as leaders of the intervention groups

Contributor Information

Julia H. Rowland, Office of Cancer Survivorship, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health/Department of Health and Human Services

Beth E. Meyerowitz, Department of Psychology; University of Southern California

Catherine M. Crespi, Department of Biostatistics and Division of Cancer Prevention and Control Research, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

Beth Leedham, Private practice, Encino, CA.

Katherine Desmond, Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior Center for Community Health, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA.

Thomas R. Belin, Departments of Biostatistics and Psychiatry/Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

Patricia A. Ganz, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control Research and Department of Oncology, University of California, Los Angeles

References

- 1.Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, Stinchcomb DG, Howlader N, Horner MJ, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Feuer EJ, Altekruse SF, Lewis DR, Clegg L, Eisner MP, Reichman M, Edwards BK, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 1975–2005. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2005/, based on November 2007 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowland JH, Massie MJ. Psychosocial adaptation during and after breast cancer. In: Harris JR, Lippman ME, Morrow M, Osborne CK, editors. Diseases of the breast. 4. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2009. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: A follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:39–49. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, Graham J, Richards M, Ramirez A. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: Five year observational cohort study. Br Med J. 2005;330:702–705. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38343.670868.D3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mols F, Vingerhoets AJ, Coebergh JW, et al. Quality of life among long-term breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2005;411:2613–2619. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alfano CM, Rowland JH. Recovery issues in cancer survivorship: a new challenge for supportive care. Cancer Journal. 2006;12:432–443. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200609000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knobf T. Psychosocial responses in breast cancer survivors. Sem Oncol Nurs. 2007;23:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolberg WH, Romsaas EP, Tanner MA, Malec JF. Psychosexual adaptation to breast cancer surgery. Cancer. 1989;63:1645–1655. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890415)63:8<1645::aid-cncr2820630835>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganz PA, Schag CAC, Lee JJ, Polinsky ML, Tan SJ. Breast conservation versus mastectomy: Is there a difference in psychological adjustment or quality of life in the year after surgery. Cancer. 1992;69:1729–1738. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920401)69:7<1729::aid-cncr2820690714>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schag CA, Ganz PA, Polinsky ML, Fred C, Hirji K, Petersen L. Characteristics of women at risk for psychosocial distress in the year after breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:783–793. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.4.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broeckel JA, Thors CL, Jacobsen PB, Small M, Cox CE. Sexual functioning in long-term breast cancer survivors treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;75:241–248. doi: 10.1023/a:1019953027596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kornblith AB, Herndon JE, 2nd, Weiss RB, et al. Long-term adjustment of survivors of early-stage breast carcinoma, 20 years after adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 2003;98:679–689. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burwell SR, Case D, Kaelin C, Avis NE. Sexual problems in younger women after breast cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2815–2821. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiebert GM, de Haes JC, Van de Velde CJ. The impact of breast conserving treatment and mastectomy on the quality of life of early-stage breast cancer patients: a review. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1059–1070. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.6.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy SM, Haynes LT, Herberman RB, Lee J, McFeeley S, Kirkwood J. Mastectomy versus breast conservation surgery: mental health effects at long-term follow-up. Health Psychol. 1992;11:349–354. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.6.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Desmond K, Meyerowitz BE, Wyatt GE. Life after breast cancer: Understanding women’s health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:501–514. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyerowitz BE, Desmond KA, Rowland JH, Wyatt GE. Sexuality following breast cancer. J Sex Marital Ther. 1999;25:237–250. doi: 10.1080/00926239908403998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor KL, Lamdan RM, Siegel JE, Shelby R, Hrywna M, Moran-Klimi K. Treatment regimen, sexual attractiveness concerns and psychological adjustment among African American breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology. 2002;11:505–517. doi: 10.1002/pon.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowland JH, Desmond KA, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR, Wyatt GE, Ganz PA. Role of breast reconstructive surgery in physical and emotional outcomes among breast cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1422–1429. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.17.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yurek D, Farrar W, Andersen BL. Comparing surgical groups and determining individual differences in postoperative sexuality and body change stress. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:697–709. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.68.4.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beckjord E, Compas BE. Sexual quality of life in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2007;25:19–36. doi: 10.1300/J077v25n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pelusi J. Sexuality and body image. Am J Nursing. 2006;106:32–38. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200603003-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L, Kahn B, Bower JE. Breast cancer in younger women: reproductive and late health effects of treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4184–4193. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fobair P, Stewart SL, Chang S, D’Onofrio C, Banks P, Bloom JR. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15:579–594. doi: 10.1002/pon.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frierson G, Thiel DL, Andersen BL. Body change stress for women with breast cancer: The Breast-Impact of Treatment Scale. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32:77–81. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3201_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manne S, Ostroff J, Rini C, Fox K, Goldstein L, Granna G. The interpersonal model of intimacy: The role of self-disclosure, partner disclosure, and partner responsiveness in interactions between breast cancer patients and their partners. J Family Psychol. 2004;18:589–599. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wimberly SR, Carver CS, Laurenceau J-P, Harris SD, Antoni MH. Perceived partner reactions to diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer: Impact on psychosocial and psychosexual adjustment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:300–311. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newell SA, Sanson-Fisher RW, Savolainen NJ. Systematic review of psychological therapies for cancer patients: Overview and recommendations for future research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:558–584. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.8.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shell JA. Evidence-based practice for symptom management in adults with cancer: sexual dysfunction. Oncol Nur Forum. 2002;29:53–66. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.53-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanton AL. Psychosocial concerns and interventions for cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5132–5137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Belin TR, Meyerowitz BE, Rowland JH. Predictors of sexual health in women after a breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2371–2380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Desmond KA. Impact of different adjuvant therapy strategies on quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Recent Results Cancer Res. 1998;152:396–411. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-45769-2_38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psych Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myers JK, Weissman MM. Use of a self-report symptom scale to detect depression in a community sample. Am J Psychiatr. 1980;137:1081–1084. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts RE, Vernon SW. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Its use in a community sample. Am J Psychiatr. 1983;140:41–46. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Busby DM, Crane DR, Larson JH, Christensen C. A revision of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale for use with distressed and nondistressed couples: Construct hierarchy and multidimensional scales. J Mar Family Ther. 1995;3:289–308. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: new scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J Marriage Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schag CA, Heinrich RL, Aadland RL, Ganz PA. Assessing problems of cancer patients: psychometric properties of the cancer inventory of problem situations. Health Psychol. 1990;9:83–102. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ganz PA, Schag CA, Lee JJ, Sim MS. The CARES: a generic measure of health-related quality of life for patients with cancer. Qual Life Res. 1992;1:19–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00435432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ganz PA, Coscarelli A, Fred C, Kahn B, Polinsky ML, Petersen L. Breast cancer survivors: psychosocial concerns and quality of life. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;38:183–99. doi: 10.1007/BF01806673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherbourne CD. Social functioning: Sexual problems measures. In: Stewart AL, Ware JE, editors. Measuring functioning and well-being: The Medical Outcomes Study approach. Duke University Press; London: 1992. pp. 194–204. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Masters JH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. Boston: Little, Brown; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Angrist JD, Imbens GW, Rubin DB. Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables (with discussion) J Am Stat Assoc. 1996;91:444–472. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Imbens GW, Rubin DB. Bayesian inference for causal effects in randomized experiments with noncompliance. Annals of Statistics. 1997;25:305–327. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skrondal A, Rabe-Hesketh S. Generalized Latent Variable Modeling. Chapman & Hall/CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coyne JC, Lepore SJ, Palmer SC. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions in cancer care: evidence is weaker than it first looks. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32:104–10. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3202_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andrykowski MA, Manne SL. Are psychological interventions effective and accepted by cancer patients? I. Standards and levels of evidence. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32:93–7. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3202_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manne SL, Andrykowski MA. Are psychological interventions effective and accepted by cancer patients? II. Using empirically supported therapy guidelines to decide. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32:98–10. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3202_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huber C, Ramnarace T, McCaffery R. Sexuality and intimacy issues facing women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:1163–1167. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.1163-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.President’s Cancer Panel. 2003/2004 Annual Report: Living Beyond Cancer: Finding a New Balance; Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goodwin PJ, Leszcz M, Ennis M, Koopmans J, Vincent L, Guther H, Drysdale E, Hundleby M, Chochinov HM, Navarro M, Speca M, Hunter J. The effect of group psychosocial support on survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1719–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stanton AL, Ganz PA, Kwan L, Meyerowitz BE, Bower JE, Krupnick JL, Rowland JH, Leedham B, Belin TR. Outcomes from the Moving Beyond Cancer psychoeducational, randomized, controlled trial with breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6009–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]