Abstract

The alarming spread of bacterial strains exhibiting resistance to current antibiotic therapies necessitates that we elucidate the specific genetic and biochemical responses underlying drug-mediated cell killing, so as to increase the efficacy of available treatments and develop new antibacterials. Recent research aimed at identifying such cellular contributions has revealed that antibiotics induce changes in metabolism that promote the formation of reactive oxygen species, which play a role in cell death. Here we discuss the relationship between drug-induced oxidative stress, the SOS response and their potential combined contribution to resistance development. Additionally, we describe ways in which these responses are being taken advantage of to combat bacterial infections and arrest the rise of resistant strains.

Introduction

The emergence of bacteria that have developed resistance to nearly all single and combinatorial antibiotic therapies used in the treatment of infection is a worldwide clinical threat. We are faced with an expanding list of microbial species that can actively escape, with mechanistic heterogeneity, the killing action of structurally and functionally diverse drug classes. It is clear that novel antibacterial tactics, including systematic exploration and exploitation of microbial drug stress response and defense systems, are required to combat antibiotic resistance [1].

Bacteria are capable of resisting the action of antibiotics as a result of genetic alterations, including the physical exchange of genetic material with another organism (via plasmid conjugation, phage-based transduction or horizontal transformation), the activation of latent mobile genetic elements (transposons or cryptic genes), and the mutagenesis of its own DNA [2]. The latter of these mechanisms, chromosomal mutagenesis, may arise directly from interaction between the chromosome and the antibacterial agent or antibiotic-induced oxidative stress, or indirectly from the bacterium’s error-prone DNA polymerases during the repair of a broad spectrum of DNA lesions. The efficacy of inhibiting essential bacterial processes by antibiotics, and thus their capacity to prevent infection, is diminished following any of the aforementioned resistance-conferring events. This is due to the microbe’s new-found ability to modify or destroy the structure of a given drug, reduce access to the drug target by an alteration in permeability/active transport, or abolish stable interactions between the drug molecule and its target [2,3].

Clearly, the encounter between a thriving bacterial population and antibacterial molecules that threaten the existence of this population presents an enormous stress to each microbe in the population. The critical effect of this antibiotic-induced stress is the generation of an intracellular environment that is highly conducive to genetic evolution, owed to a tremendous degree of selective pressure and the physiological responses of the microbe [4,5]. Core responses include the SOS DNA stress response (first described by Radman and Witkin [6,7]), the heat-shock protein stress response (recently reviewed in [8]), and the oxidative stress response [9,10]. Any bacterium surviving the initial wave of antibacterial attack, due to any or all of these defensive responses, may therefore serve as “patient zero” in the rise of populations resistant to single drugs or multiple drugs. In this same manner, just a few “patient zeros” may contribute to the burgeoning phenomenon of heteroresistance, where isolates from a given resistant population exhibit heterogeneous levels of resistance to an antibiotic

In this commentary, we discuss the mechanism by which cellular-generated oxidative stress is induced by antibiotic treatment, and the role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in drug-mediated bacterial cell death. Further, we consider the relationship between the SOS response and antibiotic-stimulated ROS, as well as the mutagenic potential of these reactions, and describe current efforts to exploit cellular responses in fighting drug-resistant strains.

ROS formation

The formation of ROS in living organisms is an unfortunate by-product of respiration in an oxygen-rich environment [9]. There is an extensive literature providing evidence for the role of endogenous ROS as a causative agent in mutagenesis and as a significant contributor to the mutational burden experienced by microbes during periods of oxidative stress (for example, [11–13]). This notion is supported by the existence of several overlapping enzymatic mechanisms employed by bacteria to combat ROS toxicity [14].

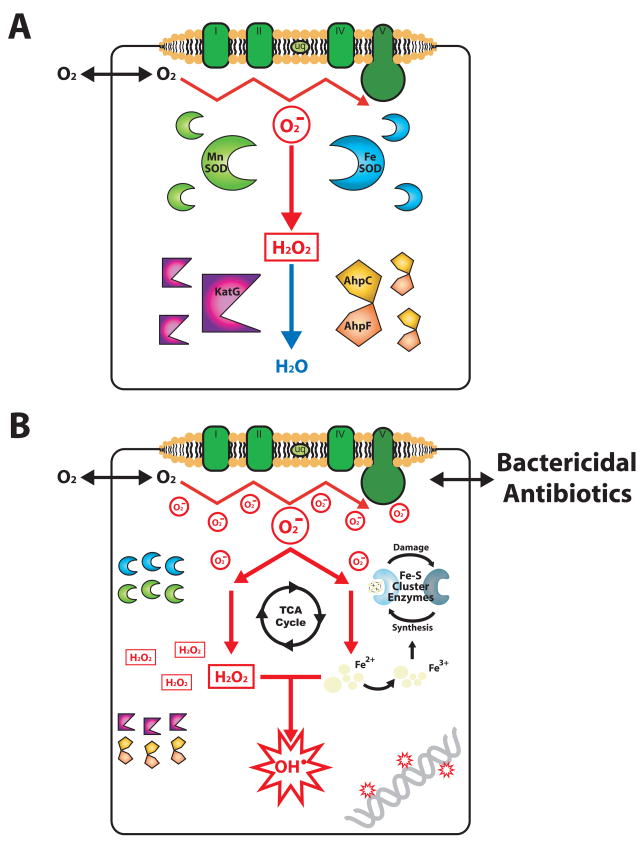

ROS are generated intracellularly during aerobiosis-fueled oxygen metabolism via successive single-electron reductions, thereby producing superoxide (O2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and highly-destructive hydroxyl radicals (OH•). Environmental molecular oxygen (O2) can readily diffuse into microbes and interact with a host of cellular biomolecules. Of particular importance to ROS formation are those interactions between O2 and biomolecules like respiratory flavoenzymes, which have accessible catalytic redox cofactors within their active sites and readily participate in electron transfer reactions with O2. While O2• − and H2O2 can both be generated in this manner, recent evidence has shown that the respiratory chain is responsible for the production of biologically-relevant levels of O2•− [15], but not H2O2 [16]; the specific cytoplasmic mechanism for the generation of H2O2 in appreciable quantities during steady state is not well understood.

Unlike O2• − and H2O2, which can be enzymatically eradicated by the activity of superoxide dismutases (2O2•− + 2H+ → H2O2 + O2) and catalases/peroxidases (2H2O2 → 2H2O + O2), respectively, there exists no known enzyme that catalyzes the cellular detoxification of OH•. Instead, OH• is capable of indiscriminate oxidative attack on proteins, lipids and DNA in a manner that may be cytotoxic or mutagenic [17]. OH• are generated in vivo via the Fenton reaction [18], during which cytoplasmic, solvent-accessible ferrous iron (Fe2+) is oxidized by H2O2 to yield OH• (H2O2 + Fe2+ → OH• + OH− + Fe3+). The Fenton reaction is interdependent on the Haber-Weiss reaction, during which ferric iron (Fe3+) is reduced by O2•− to yield Fe2+. It is important to note that O2•− may interact with “free”, unincorporated Fe3+, or it may reductively attack iron-sulfur cluster-bearing enzymes, thereby destabilizing and/or releasing Fenton-ready Fe2+ [19,20].

As such, during periods of oxidative stress, O2• − is produced at the membrane by the respiratory chain and is either dismutated by superoxide dismutases to H2O2 or reduces Fe3+ by Haber-Weiss chemistry. H2O2 can then oxidize Fe2+ by Fenton chemistry to yield OH• and Fe3+, therefore potentially establishing a vicious redox cycle of ROS attack and generation. Because Fe2+ is capable of localizing to DNA, proteins and lipids, generation of OH• may occur in the immediate vicinity of these biomolecules and thus focus its deleterious effects. Along these lines, it has been shown that Fe2+ exhibits a sequence-specific preference when binding DNA and participating in the Fenton reaction [21,22]. Interestingly, this sequence can be found within the operator sites that enable binding of the iron regulatory transcription factor, Fur, to iron homeostasis-related gene promoters [23].

Antibiotic-induced ROS formation

As noted earlier, a better understanding of the specific sequences of events leading to cell death from the wide range of bactericidal antibiotics is needed for the development of more effective antibacterial therapies. One promising approach involves the identification of bacterial response network targets that can be exploited to combat the rise of resistant microbes [24].

Along these lines, we recently employed a systems biology approach to identify novel mechanisms that contribute to bacterial cell death upon DNA gyrase inhibition by the widely used fluoroquinolone antibiotic, norfloxacin [25]. It is well-known that fluoroquinolone drugs achieve their deadly effect through direct binding with DNA gyrase (topoisomerase II, product of gyrA and gyrB) and/or Topoisomerase IV (product of parC and parE ), trapping the topoisomerase(s) between the DNA strand breakage and rejoining steps that take place during modulation of DNA supercoiling [26]. This interaction results in the formation of double-stranded DNA breaks and ultimately replication arrest by blocking replication forks.

In our study, we performed phenotypic and microarray analyses on E. coli treated with norfloxacin to identify additional contributors to cell death resulting from gyrase poisoning [25]. In the course of this work, we discovered and characterized a novel oxidative damage cell death pathway which involves ROS formation, due in part to a breakdown in iron regulatory dynamics following norfloxacin-induced DNA damage. More specifically, we showed that gyrase-inhibiting antibiotic treatment resulted in the activation of the SoxR-regulated O2•− stress response [27], the IscR-regulated iscRUSA operon for repair/synthesis of heavily-degraded iron-sulfur clusters [28], Fur-regulated iron import and utilization [29], as well as the SOS DNA stress response [30]. We demonstrated in vivo that these events promote the Fenton reaction-catalyzed generation of OH•, and that these highly destructive molecules play a critical role in the bactericidal efficacy of norfloxacin [25]. Key contributors to OH• production and cell killing were atpC (a structural and proton-translocating component of ATP synthase) and iscS (a component of the aforementioned IscR-regulated iron-sulfur cluster synthesis machinery). Importantly, to prove that the observed generation of ROS was not due to redox-cycling of the antibiotic, we treated quinolone-resistant E. coli strains harboring mutations in the gyrA gene and found that we could not detect OH• generation.

Building upon this work with fluoroquinolones, we have further shown that all classes of bactericidal antibiotics, regardless of their specific target, promote the generation of lethal hydroxyl radicals in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [10]. To get at the system-level responses underlying this phenomenon, we used microarrays to collect time-course gene expression response profiles for E. coli exposed to representatives of the major bactericidal drug classes, including β-lactams and aminoglycosides, in addition to fluoroquinolones. We analyzed microarray data were analyzed using transcriptional regulatory and biochemical pathway classifications in order to refine the list of significantly changing genes (by z-score) and identify coordinately-responding functional groups that were common across the diverse drug classes. By taking this approach, we were able to predict and subsequently confirm experimentally that the general mechanism of lethal OH• production involves tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle metabolism and a transient depletion of NADH, in addition to iron-sulfur cluster destabilization and iron misregulation.

The role of ROS in drug-induced killing has been expanded upon in several recent studies. For example, Wang and Zhao, in an attempt to determine which components of cellular ROS defense systems play a role in this phenotype, showed that the combined activity of superoxide dismutases SodA and SodB (containing manganese and iron as cofactors, respectively) were critical to killing by fluorquinolones, while the peroxidase AhpC (which uses NADH as reducing equivalent when breaking down H2O2) was critical to killing by β-lactams and aminoglycosides [31]. Additionally, Engelberg-Kulka and colleagues have reported on a potential connection between ROS generation, the chromosomally-encoded MazF toxin and the Extracellular Death Factor (EDF) signaling peptide [32].

Moreover, three recent and separate comprehensive screens of the contribution of single-gene disruptions to increased antibiotic susceptibility have provided further support for antibiotic-induced ROS formation and the role of ROS in drug-mediated killing [33–35]. Specifically, Miller and coworkers observed that impairment of ROS defenses in E. coli potentiates killing by rifampin (a rifamycin) and metronidazole (a nitroimidazole) [33], while Tavazoie and coworkers showed that inhibition of aerobic respiration reduced the susceptibility of E. coli to aminoglycoside antibiotics [34], and Hancock and colleagues observed that mutations in TCA cycle metabolism and respiratory electron transport chain components decreased killing by tobramycin (an aminoglycoside) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa [35].

Taken together, these studies have begun to establish a mechanism for ROS production in bacteria during stressful versus steady-state conditions. Along these lines, we have recently attempted to elucidate the cellular events that connect treatment of bacteria with aminoglycoside antibiotics and the oxidative stress cell death pathway [36]. Our results show that aminoglycoside-induced mistranslation and misfolding of membrane-associated proteins activate the envelope stress response and redox-responsive two-component signal systems, leading to the production of hydroxyl radicals. Moreover, we found that these two-component systems are broadly involved in bactericidal antibiotic-mediated oxidative stress and cell death, providing additional insight into the common mechanism of killing induced by bactericidal antibiotics.

Antibiotic-induced SOS response activation and error-prone polymerases

A great deal of recent attention has been paid to the role of the SOS stress response in the phenomenon of induced mutagenesis [37], and the potential for combating resistance by inhibiting the activity of SOS-regulated, mutagenic machinery [38–40]. Considering that the SOS response is most efficiently activated by DNA damaging agents, it is not surprising that the most convincing evidence correlating antibiotic treatment with inducible mutagenesis and acquired resistance has followed from the study of fluoroquinolone antibiotics [41–44].

During times of homeostasis, the LexA repressor protein effectively represses, via steric inhibition, the expression of the genes that compose the SOS regulon [30]. Upon detection of exposed, single-stranded DNA (the result of DNA damage or stalled replication forks), the SOS co-regulator, RecA, is activated. The immediate effect of this activation is the formation of nucleoprotein filaments at the site(s) of genotoxic stress. Oligomerization of activated RecA then triggers autoproteolysis of LexA, thereby inactivating LexA, alleviating LexA-mediated repression and initializing the highly dynamic expression of SOS genes [45].

The majority of core SOS genes [46], have some function in the physical repair of damaged DNA. Repair may occur via nucleotide excision, base excision or recombination pathways, depending on the type and number of lesions. The repair process also involves the activity of specialized DNA polymerases, DNA pol II (product of polB/dinA), IV (product of dinB) and V (product of umuC and umuD), which catalyze error-prone DNA synthesis across lesions (translesion synthesis, or TLS) that are physically prohibitive to the normal replicative polymerase, DNA pol III [47,48]. Expression of pol V is SOS-dependent and its activity is RecA-dependent, while expression of pol II and IV is SOS-independent yet increased approximately 10-fold upon SOS induction [30]. While there is some degree of functional overlap, and competition between these polymerases has been observed in vivo, pol II and IV are considered more proficient at handling sterically bulky DNA adducts (i.e., benzopyrenes) [49], whereas thiamine dimers, abasic sites and ROS-mediated oxidation products are considered better substrates for pol V [50]. The greatest difference between these specialized DNA polymerases (and when compared to pol III) is the accuracy with which they add the appropriate deoxyribonucleotide base opposite damaged or undamaged template DNA. Due, in part, to major structural differences (i.e., a more accessible active site and the absence of the so-called “O-helix”, an α-helix that plays a key role in pairing cognate deoxyribonucleotides), Y-family polymerases pol IV and pol V have been shown to synthesize DNA with significantly higher error frequencies than pol II (up to 1000-fold less fidelity), depending on the template [51,52]. Y-family polymerases also lack the exonuclease function of polymerases like pol II, and therefore cannot correct mistakes that are made during replication.

Induction of the SOS response has also been explored following treatment with antibiotics that do not directly cause DNA damage. For example, several β-lactam drugs (including ampicillin), which achieve lethality by disrupting membrane maintenance and biosynthesis or by damaging the cell wall, were shown by Miller and colleagues to trigger the SOS response via activation of the DpiAB two-component system [53]. Additional recent studies have further explored the link between β-lactams, activation of the SOS response and SOS-related expression of error-prone polymerases [10,54,55]. SOS induction has also been observed following treatment with trimethoprim (a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor) [56], which is commonly formulated together with sulfamethoxazole (a sulfonamide) as co-trimoxazole and used to stem urinary tract infections. This latter finding has been attributed to the ability of this drug combination to exhaust intracellular pools of deoxyribonucleotides by inhibition of ribonucleotide reductases, a mixed signal that may be perceived by the cell as a sign of overwhelming DNA stress (discussed in [57]).

A plausible explanation for the observed activation of the SOS response by a diverse set of non-genotoxic antibiotics is the antibiotic-induced cellular generation of ROS, an effect we have explored and validated experimentally [10,25]. It is also possible that activation of the SOS response, via direct or indirect mechanisms (e.g., two-component system signaling), acts as a catalyst for ROS production during periods of drug-based stress. ROS mutagenesis, which is addressed in the next section, may then maintain the SOS response in a chronically activated state and amplify ROS generation. A more detailed exploration of the temporal gene expression dynamics underlying interrelated antibiotic-induced SOS and oxidative stress response activation is needed to address these concepts.

DNA mutagenesis by ROS and its repair

The types of genotoxic stress induced by ROS include physical damage to the DNA base moiety and the sugar-phosphate backbone of incorporated or unincorporated (“free”) nucleotides, as well as single- and double-stranded breaks within the double helix; in addition, DNA can be damaged by by-products of lipid peroxidation [58]. A wide variety of base adducts have been described following exposure to ROS, with the most prevalent of these being 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG or GO), 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamido-pyrimidine (FapyG), and thymine glycol (TG).

The cellular mechanisms that deal with the deleterious mutagenic effects of these stable adducts have been extensively studied. For example, because the 8-oxoG adduct can mispair with adenine nucleotides nearly as efficiently as it can pair with cognate cytosine nucleotides, this mutated base frequently results in G:C to T:A transversions when pol V-based translesion synthesis (TLS) occurs before specific cellular defenses arrive on the scene. Moreover, the 8-oxoG adduct provides a locus for further attack by ROS and reactive nitrogen species, yielding an array of DNA hyperoxidation products. A recent study performed by Neeley and colleagues examined the efficiency with which TLS polymerases pol II, pol IV and pol V bypassed 8-oxoG and 8-oxoG hyperoxidation lesions, and monitored the frequency of 8-oxoG-related mutations in vivo on template DNA [59]. They found that pol V exhibited the greatest TLS efficiency across the mutagenic spectrum tested, and that the activity of pol V was required for SOS-dependent remediation of oxidative lesions. Interestingly, the authors also concluded that the nucleotide which pol V incorporates opposite a given oxidative adduct has more to do with the lesion itself rather than the TLS abilities of the polymerase. This point may be critical to the link between acquired resistance, hypermutability and antibiotic-induced oxidative mutagenesis, e.g., ROS could provide a means to rapidly diversify the breadth of mutation, which is then amplified by the activity of error-prone SOS polymerases.

To prevent this from occurring, bacteria have evolved a three-component 8-oxoG elimination system, referred to as the “GO system”. The GO machinery includes the MutM glycosylase which removes 8-oxoG adducts, the MutY glycosylase which removes misincorporated adenine nucleotides during the replication process, and the MutT phosphatase which sanitizes the nucleotide pool of available 8-oxo-G triphosphate by hydrolyzing its conversion to 8-oxo-G monophosphate; MutM also excises FapyG adducts, while the exonucleases Ndh and Nei excise TG adducts [60,61]. Glycosylases function by scanning DNA for lesions, then binding the lesion site in such a way that the base adduct is flipped outwards for N-glycosylic bond cleavage (between the base moiety and the sugar-phosphate backbone) within the glycosylase active site [62,63]. In this manner, the active site determines the specificity of the enzyme.

A potentially mutagenic and/or cytotoxic abasic site (lacking the base moiety) is generated following glycosylic cleavage, requiring further processing, including the activities of abasic endonucleases, DNA ligase and DNA polymerases. Furthermore, if abasic sites on opposing DNA strands are in close proximity, double-stranded breaks may result [64]. Pol V is among those polymerases that can efficiently synthesize DNA across abasic sites. As such, environmental conditions that promote oxidative stress, including growth in the presence of bactericidal antibiotics, provide powerful direct and indirect mechanisms for mutagenesis. There is a great deal yet to be explored in this space, including the contribution of these conditions to the development of antibiotic resistance.

Conclusions

Eighty years ago, Alexander Fleming’s publication detailing his discovery of penicillin ushered in the modern era of antibacterial therapy [65]. Yet, within 15 years of his findings, Fleming presciently hypothesized that bacteria would likely attain resistance to any antibiotic treatment given the right circumstance. The continued emergence of single and multiple antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains exists as one of the more important societal issues today. Justifiably, the focus of antibiotic resistance research in the last half century has been on the elucidation of the mechanisms by which microbes can physically alter a drug’s structure, disrupt the interaction between a drug and its cellular target, or alter the behavior and efficiency of its own transport machinery to reduce access to a drug’s cellular target [2,3]. A new wave of research, however, dedicated to characterizing the physiological responses of bacteria to the presence and action of antibiotics may hold the key to thwarting the rise and spread of resistance.

With regard to the SOS response and the phenomenon of induced mutagenesis, a number of current research efforts have explored the effects of disabling the protein regulators that control expression of the SOS network of genes, including error-prone polymerases. For example, we have recently shown that a recA knockout strain of E. coli is significantly more susceptible to all classes of bactericidal antibiotics, highlighting the contributions of ROS to drug killing [10]. Additionally, in a study by Romesberg and coworkers, it was shown that expression of an uncleavable form of LexA (thus preventing SOS activation) in drug-treated bacteria resulted in decreased survival and markedly lower mutation rates in culture (ciprofloxacin), as well as in a mouse model of infection (ciprofloxacin and rifampicin) [38]. Along these lines, recent work by our lab has demonstrated that bacteriophage engineered to express an uncleavable LexA variant substantially increase survival in an ofloxacin-treated mouse model of systemic infection [40]; moreover, in this same study, it was shown that combinatorial treatment of ofloxacin and engineered bacteriophage can enhance the killing of fluoroquinolone-resistant bacteria by nearly four orders of magnitude compared to ofloxacin alone. Together with efforts aimed at identifying small molecule and short peptide inhibitors of RecA’s ATPase and DNA filament formation abilities [66,67], it is clear that great potential lies in taking advantage of our current knowledge of the SOS response to combat current antibiotic resistance and prevent further development of resistant strains. These efforts may also offer the added benefit of increasing the efficacy of currently prescribed drugs, which would be particularly important given the lack of developmental efforts [1].

With regard to antibiotic-induced ROS formation and its role in bacterial resistance, a number of studies have attempted to resolve the role of ROS and the oxidative stress response in cell killing following drug treatment. In fact, it is likely that studies such as those by Demple and colleagues, which described several distinct mutations (some never before observed) in multidrug-resistant clinical isolates that increased expression of the O2• − response activator, SoxS [68], will become increasingly more common as the role of oxidative stress in antibiotic-mediated cell death becomes clearer. As we determine the steps between antibiotic addition and the metabolic changes that fuel ROS formation for bactericidal drug classes [10,25], it is vital that we compare and contrast these mechanisms with what we know about ROS generation and remediation during steady-state growth or following treatment with redox-cycling drugs

[14,17]. It may then be possible to exploit the oxidative stress response in order to enhance current antibacterial therapies, as was highlighted recently when bacteriophage engineered to overexpress SoxR significantly increased cell killing by ofloxacin [40]. Moreover, this approach may afford for the identification of novel targets within the microbe’s defense systems for the development of inhibitor molecules or new antibiotics.

Figure.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Walsh C. Where will new antibiotics come from? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2003;1:65–70. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright GD. The antibiotic resistome: the nexus of chemical and genetic diversity. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:175–186. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alekshun MN, Levy SB. Molecular mechanisms of antibacterial multidrug resistance. Cell. 2007;128:1037–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Storz G, Hengge-Aronis R. Bacterial stress responses. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster PL. Stress-induced mutagenesis in bacteria. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;42:373–397. doi: 10.1080/10409230701648494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radman M. Phenomenology of an inducible mutagenic DNA repair pathway in Escherichia coli: SOS repair hypothesis. In: Prakash L, Sherman F, Miller M, Lawrence C, Tabor H, Thomas Charles C, editors. Molecular and Environmental Aspects of Mutagenesis. 1974. pp. 128–142. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witkin EM. Ultraviolet mutagenesis and inducible DNA repair in Escherichia coli. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:869–907. doi: 10.1128/br.40.4.869-907.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guisbert E, Yura T, Rhodius VA, Gross CA. Convergence of molecular, modeling, and systems approaches for an understanding of the Escherichia coli heat shock response. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:545–554. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00007-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Storz G, Imlay JA. Oxidative stress. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:188–194. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10•.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Hayete B, Lawrence CA, Collins JJ. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell. 2007;130:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.049. Reveals that treatment of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria with bactericidal antibiotics induces the formation of hydroxyl radicals via a common mechanism that involves drug-induced changes in cellular metabolism, notably the tricarboxylic acid cycle. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levin DE, Hollstein M, Christman MF, Schwiers EA, Ames BN. A new Salmonella tester strain (TA102) with A X T base pairs at the site of mutation detects oxidative mutagens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:7445–7449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farr SB, D’Ari R, Touati D. Oxygen-dependent mutagenesis in Escherichia coli lacking superoxide dismutase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:8268–8272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakai A, Nakanishi M, Yoshiyama K, Maki H. Impact of reactive oxygen species on spontaneous mutagenesis in Escherichia coli. Genes Cells. 2006;11:767–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14•.Imlay JA. Cellular defenses against superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:755–776. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061606.161055. A comprehensive review that details the mechanism of reactive oxygen species generation in bacteria, as well as the layers of protection employed by bacteria in their defense against these toxic molecules. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korshunov S, Imlay JA. Detection and quantification of superoxide formed within the periplasm of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:6326–6334. doi: 10.1128/JB.00554-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seaver LC, Imlay JA. Are respiratory enzymes the primary sources of intracellular hydrogen peroxide? J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48742–48750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imlay JA. Pathways of oxidative damage. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:395–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imlay JA, Chin SM, Linn S. Toxic DNA damage by hydrogen peroxide through the Fenton reaction in vivo and in vitro. Science. 1988;240:640–642. doi: 10.1126/science.2834821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liochev SI, Fridovich I. Superoxide and iron: partners in crime. IUBMB Life. 1999;48:157–161. doi: 10.1080/713803492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiley PJ, Beinert H. The role of Fe-S proteins in sensing and regulation in bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:181–185. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rai P, Wemmer DE, Linn S. Preferential binding and structural distortion by Fe2+ at RGGG-containing DNA sequences correlates with enhanced oxidative cleavage at such sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:497–510. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balasubramanian B, Pogozelski WK, Tullius TD. DNA strand breaking by the hydroxyl radical is governed by the accessible surface areas of the hydrogen atoms of the DNA backbone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9738–9743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henle ES, Han Z, Tang N, Rai P, Luo Y, Linn S. Sequence-specific DNA cleavage by Fe2+-mediated fenton reactions has possible biological implications. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:962–971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dwyer DJ, Kohanski MA, Collins JJ. Networking opportunities for bacteria. Cell. 2008;135:1153–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25•.Dwyer DJ, Kohanski MA, Hayete B, Collins JJ. Gyrase inhibitors induce an oxidative damage cellular death pathway in Escherichia coli. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:91. doi: 10.1038/msb4100135. Describes the responses of E. coli to gyrase inhibition by a fluoroquinolone antibiotic and a peptide toxin, which include activation of the superoxide stress response, derepression of the iron uptake and utilization regulon, and increased iron-sulfur cluster synthesis. Ultimately, these physiological changes result in hydroxyl radical production, which is shown to contribute to cell death. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drlica K, Malik M, Kerns RJ, Zhao X. Quinolone-mediated bacterial death. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:385–392. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01617-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pomposiello PJ, Demple B. Redox-operated genetic switches: the SoxR and OxyR transcription factors. Trends Biotechnol. 2001;19:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(00)01542-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayala-Castro C, Saini A, Outten FW. Fe-S cluster assembly pathways in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:110–125. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00034-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braun V. Iron uptake by Escherichia coli. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s1409–1421. doi: 10.2741/1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W, Wood RD, Schultz RA, Ellenberger T. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. 2. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Zhao X. Contribution of oxidative damage to antimicrobial lethality. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1395–1402. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01087-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kolodkin-Gal I, Sat B, Keshet A, Engelberg-Kulka H. The communication factor EDF and the toxin-antitoxin module mazEF determine the mode of action of antibiotics. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamae C, Liu A, Kim K, Sitz D, Hong J, Becket E, Bui A, Solaimani P, Tran KP, Yang H, et al. Determination of antibiotic hypersensitivity among 4,000 single-gene-knockout mutants of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:5981–5988. doi: 10.1128/JB.01982-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34•.Girgis HS, Hottes AK, Tavazoie S. Genetic architecture of intrinsic antibiotic susceptibility. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005629. Describes a transposon-based mutagenesis screen which identified individual genes and biochemical pathways, in a sub-MIC growth assay, that differentially contribute to the increased or decreased sensitivity of E. coli to a wide range of bactericidal and bacteriostatic antibiotics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35•.Schurek KN, Marr AK, Taylor PK, Wiegand I, Semenec L, Khaira BK, Hancock RE. Novel genetic determinants of low-level aminoglycoside resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:4213–4219. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00507-08. Describes the screening of a P. aeruginosa transposon mutant library for genes that individually increased the resistance of the bacterium to a clinically relevant aminoglycoside (tobramycin), defines a minimal resistome based on functional enrichment, and discusses the role of lipopolysaccharide synthesis mutants in decreased drug uptake. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Wierzbowski J, Cottarel G, Collins JJ. Mistranslation of membrane proteins and two-component system activation trigger antibiotic-mediated cell death. Cell. 2008;135:679–690. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cirz RT, Romesberg FE. Controlling mutation: intervening in evolution as a therapeutic strategy. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;42:341–354. doi: 10.1080/10409230701597741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38•.Cirz RT, Chin JK, Andes DR, de Crecy-Lagard V, Craig WA, Romesberg FE. Inhibition of mutation and combating the evolution of antibiotic resistance. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030176. Demonstrates that blocking the activation of the SOS response (by using an uncleavable LexA repressor mutant strain of E. coli), following treatment of E. coli-infected mice with either a fluoroquinolone or a rifamycin antibiotic, inhibits the evolution of resistance-conferring mutations. Additionally discusses the role of SOS component polymerases (i.e., pol V) in induced DNA mutagenesis in resistance formation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39•.Smith PA, Romesberg FE. Combating bacteria and drug resistance by inhibiting mechanisms of persistence and adaptation. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:549–556. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.27. A thought-provoking review covering resistance-forming mechanisms, including stress-induced mutagenesis and horizontal transfer of resistance-conferring genes, as well as the clinically-relevant phenomenon of persistence. Also discusses ideas for exploiting these topics as antibacterial therapies. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu TK, Collins JJ. Engineered bacteriophage targeting gene networks as adjuvants for antibiotic therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4629–4634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800442106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ysern P, Clerch B, Castano M, Gibert I, Barbe J, Llagostera M. Induction of SOS genes in Escherichia coli and mutagenesis in Salmonella typhimurium by fluoroquinolones. Mutagenesis. 1990;5:63–66. doi: 10.1093/mutage/5.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drlica K, Malik M. Fluoroquinolones: action and resistance. Curr Top Med Chem. 2003;3:249–282. doi: 10.2174/1568026033452537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beaber JW, Hochhut B, Waldor MK. SOS response promotes horizontal dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. Nature. 2004;427:72–74. doi: 10.1038/nature02241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44•.Mesak LR, Miao V, Davies J. Effects of subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics on SOS and DNA repair gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3394–3397. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01599-07. Describes the screening of several clinically-derived strains and laboratory strains of S. aureus (including several resistant to the fluoroquinolone, ciprofloxacin), with sub-MIC levels of a diverse array of antibiotics, to monitor the dynamics of the SOS response and study expression of SOS and methyl mismatch repair (MMR) genes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Friedman N, Vardi S, Ronen M, Alon U, Stavans J. Precise temporal modulation in the response of the SOS DNA repair network in individual bacteria. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Courcelle J, Khodursky A, Peter B, Brown PO, Hanawalt PC. Comparative gene expression profiles following UV exposure in wild-type and SOS-deficient Escherichia coli. Genetics. 2001;158:41–64. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Napolitano R, Janel-Bintz R, Wagner J, Fuchs RP. All three SOS-inducible DNA polymerases (Pol II, Pol IV and Pol V) are involved in induced mutagenesis. Embo J. 2000;19:6259–6265. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.22.6259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang W, Woodgate R. What a difference a decade makes: insights into translesion DNA synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15591–15598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704219104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagner J, Etienne H, Janel-Bintz R, Fuchs RP. Genetics of mutagenesis in E. coli: various combinations of translesion polymerases (Pol II, IV and V) deal with lesion/sequence context diversity. DNA Repair (Amst) 2002;1:159–167. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(01)00012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang M, Pham P, Shen X, Taylor JS, O’Donnell M, Woodgate R, Goodman MF. Roles of E. coli DNA polymerases IV and V in lesion-targeted and untargeted SOS mutagenesis. Nature. 2000;404:1014–1018. doi: 10.1038/35010020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51•.Jarosz DF, Beuning PJ, Cohen SE, Walker GC. Y-family DNA polymerases in Escherichia coli. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.12.004. A thorough review that discusses the transcriptional regulation, mutagenic potential, and mechanistic details of the error-prone, Y-family DNA polymerases pol IV (DinB) and pol V (UmuDC) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schneider S, Schorr S, Carell T. Crystal structure analysis of DNA lesion repair and tolerance mechanisms. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller C, Thomsen LE, Gaggero C, Mosseri R, Ingmer H, Cohen SN. SOS response induction by beta-lactams and bacterial defense against antibiotic lethality. Science. 2004;305:1629–1631. doi: 10.1126/science.1101630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perez-Capilla T, Baquero MR, Gomez-Gomez JM, Ionel A, Martin S, Blazquez J. SOS-independent induction of dinB transcription by beta-lactam-mediated inhibition of cell wall synthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:1515–1518. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.4.1515-1518.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55•.Maiques E, Ubeda C, Campoy S, Salvador N, Lasa I, Novick RP, Barbe J, Penades JR. beta-lactam antibiotics induce the SOS response and horizontal transfer of virulence factors in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:2726–2729. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.7.2726-2729.2006. These studies describe observations made in both E. coli and S. aureus that β-lactam antibiotics, which do not directly damage DNA, can activate expression of the SOS response and SOS-related genes, which are most efficiently induced by genotoxic stress. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goerke C, Koller J, Wolz C. Ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim cause phage induction and virulence modulation in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:171–177. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.1.171-177.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gon S, Beckwith J. Ribonucleotide reductases: influence of environment on synthesis and activity. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:773–780. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beckman KB, Ames BN. Oxidative decay of DNA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19633–19636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.19633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59•.Neeley WL, Delaney S, Alekseyev YO, Jarosz DF, Delaney JC, Walker GC, Essigmann JM. DNA polymerase V allows bypass of toxic guanine oxidation products in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12741–12748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700575200. Describes a study which measured the ability of several translesion synthesis mutant strains of E. coli to bypass a variety of oxidative DNA lesions, as well as the fidelity with which these mutant strains repaired the oxidative damage. Results showed that pol V is the primary translesion synthesis and oxidative damage repair DNA polymerase in vivo, but does so in a highly error-prone yet consistent manner that is partially mitigated by pol II activity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCullough AK, Dodson ML, Lloyd RS. Initiation of base excision repair: glycosylase mechanisms and structures. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:255–285. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cunningham RP. DNA glycosylases. Mutat Res. 1997;383:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(97)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mol CD, Parikh SS, Putnam CD, Lo TP, Tainer JA. DNA repair mechanisms for the recognition and removal of damaged DNA bases. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1999;28:101–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.David SS, O’Shea VL, Kundu S. Base-excision repair of oxidative DNA damage. Nature. 2007;447:941–950. doi: 10.1038/nature05978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Loeb LA, Preston BD. Mutagenesis by apurinic/apyrimidinic sites. Annu Rev Genet. 1986;20:201–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.001221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fleming A. On the antibacterial action of cultures of a penicillium, with special reference to their use in the isolation of B. influenzae. Br J Exp Pathol. 1929;10:226–236. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wigle TJ, Singleton SF. Directed molecular screening for RecA ATPase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:3249–3253. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cline DJ, Holt SL, Singleton SF. Inhibition of Escherichia coli RecA by rationally redesigned N-terminal helix. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:1525–1528. doi: 10.1039/b703159a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68•.Koutsolioutsou A, Pena-Llopis S, Demple B. Constitutive soxR mutations contribute to multiple-antibiotic resistance in clinical Escherichia coli isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2746–2752. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.7.2746-2752.2005. These studies describe the development of fluorescence-based assays for measuring the ATPase activity of RecA, and the rational design of a small peptide inhibitor of RecA that can bind to this critical regulator of the SOS response and inhibit its activation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]