Abstract

Background

The role of new T-cell–based blood tests for tuberculosis in the diagnosis of active tuberculosis is unclear.

Objective

To compare the performance of 2 interferon-γ assays and tuberculin skin testing in adults with suspected tuberculosis.

Design

Prospective study conducted in routine practice.

Setting

2 urban hospitals in the United Kingdom.

Patients

389 adults, predominantly of South Asian and black ethnicity, with moderate to high clinical suspicion of active tuberculosis.

Intervention

Tuberculin skin testing, the enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISpot) incorporating early secretory antigenic target-6 and culture filtrate protein-10 (standard ELISpot), and ELISpot incorporating a novel antigen, Rv3879c (ELISpotPLUS) were performed during diagnostic assessment by independent persons who were blinded to results of the other test.

Measurements

Sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and likelihood ratios.

Results

194 patients had a final diagnosis of active tuberculosis, of which 79% were culture-confirmed. Sensitivity for culture-confirmed and highly probable tuberculosis was 89% (95% CI, 84% to 93%) with ELISpotPLUS, 85% (CI, 79% to 90%) with standard ELISpot, 79% (CI, 72% to 85%) with 15-mm threshold tuberculin skin testing, and 83% (CI, 77% to 89%) with thresholds of 15 and 10 mm in vaccinated and unvaccinated patients, respectively. The ELISpotPLUS assay was more sensitive than tuberculin skin testing with 15-mm cutoff points (P = 0.01) but not with stratified 10-mm cutoff points (P = 0.10). The ELISpotPLUS assay had 4% higher diagnostic sensitivity than standard ELISpot (P = 0.02). Combined sensitivity of ELISpotPLUS and tuberculin skin testing was 99% (CI, 95% to 100%), conferring a negative likelihood ratio of 0.02 (CI, 0 to 0.06) when both test results were negative.

Limitations

Local standards for tuberculin skin testing differed from others used internationally. The study sample included few immunosuppressed patients.

Conclusions

The ELISpotPLUS is a more sensitive assay than standard ELISpot and, when used in combination with tuberculin skin testing, enables rapid exclusion of active infection in patients with moderate to high pretest probability of tuberculosis.

Keywords: sensitivity, specificity, diagnosis, tuberculosis, ESAT-6, CFP10, ELISpot, interferon-gamma, Rv3873, Rv3878, Rv3879c

Introduction

Improved diagnosis of tuberculosis is necessary to contain and reverse the rising global burden of this disease (1). The poor speed and sensitivity of existing diagnostic tools (2–4) causes delays in diagnosis and treatment of active tuberculosis, and diagnosis of extrapulmonary and paucibacillary forms is often especially challenging. Given that Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection is a prerequisite for active tuberculosis, reliable determination of infection status could accelerate diagnostic assessment by enabling rapid exclusion of tuberculosis. Recently developed T-cell–based interferon-γ release assays for tuberculosis may overcome some of the limitations of the tuberculin skin test (5–10). These immunoassays detect interferon-γ secreted by T cells in response to antigens encoded in the region of difference 1 of M. tuberculosis complex, a genomic segment absent from bacille Calmette–Guérin and most environmental mycobacteria (11). Test results are therefore not confounded by previous bacille Calmette–Guérin vaccination, conferring higher specificity than the tuberculin skin test (7–10). Moreover, results are available the next day and are unaffected by the boosting phenomenon (12).

The 2 types of T-cell–based interferon-γ release assay are whole-blood enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISpot). The whole-blood ELISA is available commercially as QuantiFERON-TB Gold and an “in-tube” variant, QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-tube (Cellestis, Carnegie, Australia) (13, 14). The ELISpot, developed by Lalvani, is available commercially as T-SPOT.TB (Oxford Immunotec, Oxford, United Kingdom) (15–18). Recent U.S. and United Kingdom national guidelines (19, 20) recommend T-cell–based interferon-γ release assays for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis, but their clinical utility in evaluation of patients with suspected active tuberculosis is poorly defined.

We compared the performance characteristics of 2 assays and tuberculin skin testing individually and in combination for the diagnostic work-up of patients with suspected active tuberculosis. The standard ELISpot assay uses early secretory antigenic target-6 and culture filtrate protein-10, the same peptides as the 2 region of difference 1–encoded antigens included in T-SPOT.TB. The ELISpotPLUS assay incorporates a novel region of difference 1–encoded antigen, Rv3879c, alongside early secretory antigenic target-6 and culture filtrate protein-10 (21).

Methods

Participants

One day each week from 12 July 2002 to 29 June 2005, we prospectively enrolled adults who presented to Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham, and Northwick Park Hospital, London, United Kingdom, with suspected tuberculosis. We invited patients 16 years of age or older to participate and provide written informed consent if their attending physician considered tuberculosis to be part of the differential diagnosis. We used no exclusion criteria. The Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, Harrow, and Oxford Clinical Research Ethics Committees granted ethical approval. Because the background prevalence of HIV is low in this population (22), we tested patients for HIV antibodies during diagnostic work-up only on the basis of clinical suspicion. We identified only 20 patients who were HIV antibody–positive.

Tuberculin Skin Testing

Tuberculin skin testing was performed as part of routine care, and experienced nurses read the results by using the Mantoux method with 0.1 mL (10 tuberculin units) of purified protein derivative (PPD)–Siebert (Evans Vaccines, Liverpool, United Kingdom). Intradermal inoculation was confirmed by the cutaneous appearance of peau d’orange. Induration was measured after 72 hours with a ruler and recorded in millimeters. Because PPD for Mantoux testing was unavailable for 10 months during the study period, 104 patients were tested by using the Heaf method, with the standard multiple puncture 6-needle disposable-head Heaf gun (Bignall Surgical Instruments, Littlehampton, United Kingdom) and concentrated PPD (100 000 tuberculin units/mL, Evans Vaccines). Heaf tests were read 1 week later, as recommended, and graded from 0 to 4. The nurses who performed and read skin tests were blinded to ELISpot results. We considered an induration of 15 mm or greater on the Mantoux test or grade 3 or 4 on the Heaf test (which is considered equivalent to the 15-mm threshold [23, 24]) to be a positive result. We assessed bacille Calmette–Guérin vaccination status by history and, where present, by scar. We also assessed tuberculin skin test performance by using stratified cutoff points of 15 mm and 10 mm (grade 2 to 4 on the Heaf test) in vaccinated and unvaccinated patients, respectively (“stratified 10 mm threshold”) (23, 24).

The ELISpot Assay

Before or within 1 week of initiating therapy, we obtained a sample of 30 mL of heparinized blood and used 7.5 × 106 peripheral blood mononuclear cells for ELISpot assays. We seeded precoated interferon-γ ELISpot plates (Mabtech AB, Stockholm, Sweden) with 2.5 × 105 peripheral blood mononuclear cells per well (17). Duplicate wells contained no antigen (negative control) or phytohemagglutinin (positive control) (ICN Biomedical, Aurora, Ohio) at 5 μg/mL. A further 13 pairs of duplicate wells each contained 1 of 13 peptide pools, which incorporated 5 to 7 overlapping 15-mer peptides. The assay on which T-SPOT.TB is based, defined as standard ELISpot in this study, comprises 35 such peptides assembled into 6 pools and spanning the length of early secretory antigenic target-6 and culture filtrate protein-10. Forty-five peptides from selected regions of Rv3873, Rv3878, and Rv3879c (Research Genetics, Huntsville, Alabama) were assembled into 7 pools (21). The ELISpotPLUS assay was defined as the 35 early secretory antigenic target-6 and culture filtrate protein-10 peptides, with 17 peptides from Rv3879c, assembled into 3 additional pools. The final concentration of each peptide was 10 μg/mL. After overnight incubation at 37 °C in 5% carbon dioxide, the plates were developed with preconjugated detector antibody (Mabtech AB) followed by chromogenic substrate (Moss, Pasadena, Maryland) (17). Spot-forming cells were counted by using an automated ELISpot reader (AID-GmbH, Strassberg, Germany). We predefined settings for the intensity and size of a counted spot and used the same settings throughout. We transferred mean readings from duplicate wells to a spreadsheet electronically and scored them as positive or negative by using a customized software program, ELISTAT (AID-GmbH). We scored responses as positive if test wells contained a mean of at least 5 spot-forming cells more than the mean of the negative control wells and were at least twice the mean of the negative control wells. This predefined cutoff point is the standard threshold used with our assay format in 9 studies including a total of 2506 participants (15–17, 25–30). Operators performing and reading the assays were blinded to tuberculin skin test results and personal identifiers. The ELISpot results were checked and countersigned before data entry by a scientist who did not perform the assays.

Diagnosis

Attending physicians performed diagnostic work-up as part of routine clinical practice, which was directed on a case-by-case basis by the patient’s clinical presentation. Two research nurses collected clinical, radiologic, and microbiological data on standardized forms at recruitment, during follow-up, and at final case notes review. Two physicians who were blinded to all ELISpot data assigned each patient to 1 of 4 predefined diagnostic categories (Table 1), which are similar to those used in other studies (25). Category 4 inevitably included some patients with inactive or latent tuberculosis. To compensate for the heterogeneity, we further classified patients in this category into 4 predefined subgroups, analogous to American Thoracic Society classes 4, 2, 1, and 0 (31), in decreasing likelihood of latent tuberculosis (Table 1). We stratified by radiologic evidence or history of previous tuberculosis, risk factors for latent infection, and skin test results.

Table 1. Diagnostic categorization of the study population n=387.

| Diagnostic category | Criteria | n | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Culture confirmed TB |

|

154 | ||

| 2 | Highly probable TB |

|

40 | ||

| 3 | Clinically indeterminate |

|

39 | ||

| 4 | Active TB excluded

|

SUBCLASSIFICATION | A Inactive TB |

|

19 |

| B One or more risk factors for TB exposure†, TST positive |

|

18 | |||

|

COne or more risk factors for TB exposure†, TST negative |

|

92 | |||

|

D No risk factors for TB exposure†, TST negative |

|

25 | |||

Abbreviations: chest radiograph (CXR), tuberculosis (TB), tuberculin skin test with 15 mm threshold (Mantoux ≥15mm or Heaf grade 3-4 considered positive) (TST)

Histological findings available in 16/40 cases and supportive in all 16 cases, comprising granulomas n=13, epithelioid cells n=7, caseation n=6, necrosis with acute inflammation n=1

Risk factors for TB exposure: recent exposure to active TB patient, born in country of high prevalence or belonging to an ethnic group with a high prevalence of TB (Incidence >100/100,000, Rose et al28).

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratios, and predictive values for each test and for sequences of 2 tests used in combination. Because the primary clinical utility of immune-based testing is to rule out tuberculosis, our predefined analytical plan focused primarily on sensitivities, negative likelihood ratios, and negative predictive values. We compared proportions by using Pearson chi-square and Fisher exact tests where sample sizes differed substantially (because of missing results for 1 of the tests). We compared the data from the ELISpot and ELISpotPLUS tests by using the McNemar chi-square test, treating the data as paired and dropping the 6 individuals who did not have an ELISpotPLUS result. We assumed that missing data were missing completely at random for our analyses, but we provide sufficient information for other analyses to be performed with different assumptions about reasons for missing data. Two-tailed P values are reported.

We calculated primary analyses of sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratios, and predictive values by using categories 1 (culture-confirmed), 2 (highly probable), and 4 (active tuberculosis excluded) (Table 1). Category 3 (clinically indeterminate) cases were not included in the calculation of test performances. To investigate whether the inclusion of category 2 cases affected sensitivity, we calculated performance by using only categories 1 and 4, and to investigate whether the inclusion of categories 4A, 4B, and 4C (which included patients with latent and inactive tuberculosis) affected specificity, we calculated performance by using only categories 1, 2, and 4D (no risk factors for tuberculosis exposure).

We assessed the performance of combinations of the 2 tests by using logistic regression models. For this analysis, we necessarily restricted the data set to patients with results from both tests. Logistic regression models can be constructed in the same form as Bayesian updating (posttest odds = pretest odds × likelihood ratio) by including the log of the pretest odds of prevalence (a constant term of known value) as an offset in the model. The linear predictor then estimates log likelihood ratios rather than log odds ratios, but bootstrap methods are required to obtain valid CIs (32). We used model parameterizations from Knottnerus (33) to compute likelihood ratios for the additional diagnostic value of each test in a testing sequence, whereas we followed the recommendations of Albert (34) to obtain estimates of likelihood ratios for combinations of tests. We computed nonparametric, bias-adjusted CIs for parameter estimates from 1000 bootstrap samples.

We computed predictors of false-negative test results by using chi-square or Fisher exact tests, using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. We performed our analyses by using GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California) and Stata, version 9.0 (Stata, College Station, Texas).

Role of the Funding Source

Wellcome Trust had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

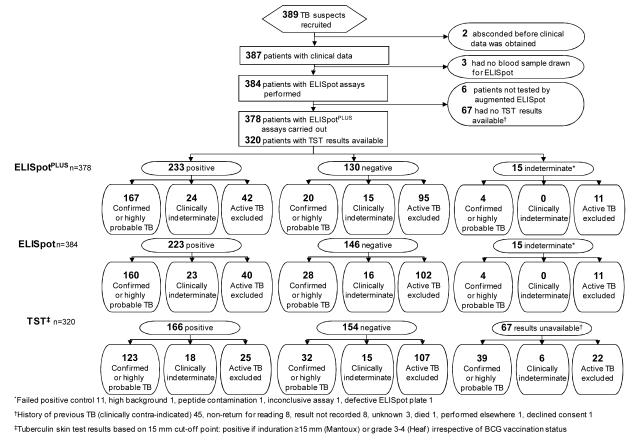

We enrolled 389 consenting adult patients, whose demographic characteristics are shown in Table 2. Blood was unavailable from 3 patients, tuberculin skin test results were unavailable in 67 patients, and 15 ELISpot assays (4%) were indeterminate (Figure 1). The 67 patients without tuberculin skin test results were similar to those with skin test results in terms of age, sex, ethnicity, presence of tuberculosis, site of disease, and presence of comorbid conditions (data provided on request). We classified 154 patients (40%) as having culture-confirmed tuberculosis, 40 (10%) as having highly probable tuberculosis, and 39 (10%) as clinically indeterminate; we excluded active tuberculosis in 154 patients (40%) (Table 1 and Appendix Figure 1, available at www.annals.org). Twenty-eight percent of tuberculosis cases were extrapulmonary; Table 3 shows the clinical subtypes of tuberculosis and alternative diagnoses for patients without tuberculosis.

Table 2. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population n=389.

| Diagnostic category | 1 Culture confirmed TB |

2 Highly probable TB |

3 Clinically indeterminate |

4 Active TB excluded |

Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Characteristic | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % |

| Total | 154 | 40 | 39 | 154 | 389* | |||||

|

Age (years)

(median, range) |

31.5 (16 - 85) | 30 (17 - 74) | 34 (17 - 88) | 47 (16-95) | 36 (16-95) | |||||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 94 | 61.0 | 20 | 50.0 | 25 | 64.1 | 95 | 61.7 | 235 | 60.4 |

| Ethnic Origin | ||||||||||

| Indian Sub-continent† | 90 | 58.4 | 26 | 65.0 | 23 | 59.0 | 83 | 53.9 | 222 | 57.1 |

| Black‡ | 34 | 22.1 | 11 | 27.5 | 11 | 28.2 | 28 | 18.2 | 86 | 22.1 |

| Caucasian | 22 | 14.3 | 1 | 2.5 | 2 | 5.1 | 65 | 22.7 | 60 | 15.4 |

| Chinese | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Other | 7 | 4.5 | 2 | 5.0 | 2 | 5.1 | 8 | 5.2 | 19 | 4.9 |

|

BCG vaccination

status |

||||||||||

| BCG vaccinated | 93 | 60.4 | 19 | 47.5 | 24 | 61.5 | 68 | 44.2 | 204 | 52.4 |

| BCG vaccination status unknown |

20 | 13.0 | 7 | 17.5 | 6 | 15.4 | 39 | 25.3 | 74 | 19.0 |

|

Pre-existing

conditions and morbidity |

||||||||||

| None | 110 | 71.4 | 35 | 87.5 | 21 | 53.8 | 76 | 49.4 | 244 | 62.7 |

| Previous TB | 12 | 7.8 | 4 | 10.0 | 9 | 23.1 | 20 | 13.0 | 45 | 11.6 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 13 | 8.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.6 | 17 | 11.0 | 31 | 8.0 |

| Asthma | 3 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.6 | 16 | 10.4 | 20 | 5.1 |

| HIV infection | 8 | 5.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 10.3 | 8 | 5.2 | 20 | 5.1 |

| Alcoholism | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.6 | 5 | 3.2 | 6 | 1.5 |

| Ischaemic heart disease |

2 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 2.6 | 6 | 1.5 |

| Sarcoidosis | 4 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.3 | 6 | 1.5 |

| Hypertension | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.6 | 5 | 3.2 | 6 | 1.5 |

| Iron deficiency anaemia | 3 | 1.9 | 1 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 5 | 1.3 |

| Chronic liver disease | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.9 | 4 | 1.0 |

| Chronic renal failure | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.3 | 3 | 0.8 |

| Epilepsy | 3 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.8 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.3 | 3 | 0.8 |

| Intra-venous drug user | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.3 | 3 | 0.8 |

| Carcinoma | 2 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.3 | 3 | 0.8 |

| Congestive cardiac failure |

1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Pneumonia | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.3 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Other§ | 6 | 3.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.6 | 20 | 13.0 | 27 | 6.9 |

Abbreviations: Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), tuberculosis (TB), tuberculin skin test with 15 mm threshold (Mantoux ≥15mm or Heaf grade 3-4 considered positive) (TST)

200 and 189 patients were recruited from London and Birmingham respectively. 325 were recruited from in-patient beds and 64 from clinics. 2 patients which absconded prior to collecting clinical data are not assigned to a diagnostic category, but appear in the total column. Approximately 50 additional patients declined consent to the study.

Pakistani: 105, Indian: 89, Sri Lankan:10, Bangladeshi: 9, Afghani: 7, Nepalese: 1, Burmese: 1

African: 81, Caribbean: 5

One case each of: acute infective hepatitis, alpha thalassaemia, atrial fibrillation, bronchiectasis, candidiasis, carpal tunnel syndrome, chronic pancreatitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hiatus hernia, idiopathic thrombocytopaenic purpura, renal transplant, leprosy, multiple sclerosis, mycobacterium avium intracellularae infection, osteomyelitis, pancreatectomy, pernicious anaemia, polycystic ovarian syndrome, previous breast surgery, previous oesophagectomy, previous rheumatic fever, prostatism, salmonella, schizophrenia, sickle cell trait, splenectomy, thyrotoxicosis, ulcerative colitis, urinary tract infection, Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. BCG = bacille Calmette–Guérin; ELISpot = enzyme-linked immunospot assay incorporating early secretory antigenic target-6 and culture filtrate protein-10; ELISpotPLUS = enzyme-linked immunospot assay incorporating early secretory antigenic target-6, culture filtrate protein-10 and Rv3879c; TB = tuberculosis; TST= tuberculin skin testing. *Results indeterminate because of no achievement of positive control (11 patients), high background (1 patient), peptide contamination (1 patient), inconclusive assay (1 patient), or defective ELISpot plate (1 patient). †Results not available because of history of previous TB (clinically contraindicated) (45 patients), patient did not return for reading (8 patients), result not recorded (8 patients), reason unknown (3 patients), patient death (1 patient), test performed elsewhere (1 patient), or patient declined consent (1 patient). ‡Tuberculin skin test results were based on a 15-mm cutoff point and considered positive if induration was ≥15 mm on the Mantoux test or grade 3 to 4 on the Heaf test regardless of BCG vaccination status.

Table 3. Final diagnoses of study participants.

| Confirmed or highly probable tuberculosis (n=194) | Active tuberculosis excluded (n=154) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site of disease | n | % | Final other diagnosis | n | % |

| Pulmonary | 140 | 72.2 | Pneumonia | 45 | 29.2 |

| Lymphatic | 18 | 9.3 | Carcinoma* | 8 | 5.2 |

| Disseminated | 10 | 5.2 | Other viral infection | 8 | 5.2 |

| Pleural | 9 | 4.6 | Bronchiectasis | 7 | 4.5 |

| Pulmonary and pleural | 3 | 1.5 | Sarcoidosis | 6 | 3.9 |

| Bone | 2 | 1.0 | Lung abscess | 5 | 3.2 |

| Genitourinary | 2 | 1.0 | Lymphoma | 4 | 2.6 |

| Abdominal | 1 | 0.5 | Inactive tuberculosis only | 4 | 2.6 |

| Breast and pericardial | 1 | 0.5 | Typhoid | 4 | 2.6 |

| Joint | 1 | 0.5 | Urinary tract infection | 4 | 2.6 |

| Meningeal | 1 | 0.5 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

3 | 1.9 |

| Pericardial | 1 | 0.5 | Healthy | 3 | 1.9 |

| Peritoneal and pleural | 1 | 0.5 | Hepatic abscess† | 3 | 1.9 |

| Pulmonary and lymphatic | 1 | 0.5 | Bacterial meningitis | 2 | 1.3 |

| Retropharyngeal | 1 | 0.5 | Bronchitis | 2 | 1.3 |

| Thyroid | 1 | 0.5 | Hepatitis | 2 | 1.3 |

| Psoas | 1 | 0.5 | Mycobacterium avium intracellularae |

2 | 1.3 |

| Osteomyelitis | 2 | 1.3 | |||

| Pancreatitis | 2 | 1.3 | |||

| Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia |

2 | 1.3 | |||

| Other‡ | 36 | 23.4 | |||

Pulmonary n=3 (squamous cell, small cell, unspecified), esophageal n=1, ovarian n=1, colonic n=1, unknown primary n=2

Hepatic abscess (pyogenic n=1, cryptococcal n=1, unspecified n=1)

One case each of: adult still’s disease, alcohol related symptoms, aspergilloma, bacterial endocarditis, benign spinal tumour, bronchial adenoma, cellulitis, cytomegalovirus, Crohn’s disease, cystic hygroma, dengue fever, deep venous thrombosis, viral encephalitis, epilepsy, hypervolaemia, foot ulcer, Goodpasture’s syndrome, hemangioma, hematoma, Henoch-Schonlein purpura, hydrocoele, hydradenitis suppurativa, hypertension related headache, hyperthyroidism, ileopsoas inflammation, laryngitis, paratyphoid, pericarditis, pyelonephritis, salmonella sepsis, septicemia, sinusitis, sterile pyuria, streptococcal associated reactive arthritis, subacute pericarditis, viral labyrinthitis.

For culture-confirmed and highly probable cases, diagnostic sensitivities were 89% (95% CI, 84% to 93%) with ELISpotPLUS, 85% (CI, 79% to 90%) with standard ELISpot, 79% (CI, 72% to 85%) with 15-mm threshold tuberculin skin testing, and 83% (CI, 77% to 89%) with stratified 10-mm threshold tuberculin skin testing (Table 4). The ELISpotPLUS assay was more sensitive than tuberculin skin testing with the 15-mm threshold (P = 0.01) but not with the stratified 10-mm threshold (P = 0.10). The ELISpotPLUS assay was more sensitive than tuberculin skin testing with a 15-mm threshold in the 297 patients with results from both tests (89% [CI, 83% to 94%] versus 81% [CI, 73% to 87%]; P = 0.04), but not with stratified-10 mm threshold (85% (CI, 78% to 90%, P = 0.2). The sensitivity of ELISpotPLUS was 4.2% higher than that of standard ELISpot (P = 0.02). Seven patients with active tuberculosis had ELISpot responses to novel peptides but not to early secretory antigenic target-6 or culture filtrate protein-10, of whom 4 were positive to Rv3873, 3 to Rv3878, and all 7 to Rv3879c.

Table 4. Diagnostic accuracy for the diagnosis of active TB disease.

| TST 15 mm threshold* |

TST Stratified-10 mm threshold¶ |

ELISpot | P† 15 mm TST |

P** 10 mm TST |

ELISpotPLUS | P‡ 15 mm TST |

P§§ 10 mm TST |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | |||||

|

Sensitivity for a diagnosis

of active tuberculosis |

||||||||||||

| Confirmed TB | 79.0 (70.6 to 85.9) | 94/119 | 82.4 (74.3 to 88.7) | 98/119 | 86.5 (79.9 to 91.6) | 128/148 | 0.10 | 0.35 | 91.2 (85.4 to 95.2) | 134/147 | 0.005 | 0.03 |

| Confirmed and highly probable TB |

79.4 (72.1 to 85.4) | 123/155 | 83.4 (77.1 to 89.3) | 129/155 | 85.1 (79.2 to 89.9) | 160/188 | 0.16 | 0.63 | 89.3 (84.0 to 93.3) | 167/187 | 0.01 | 0.10 |

|

Specificity for a diagnosis

of active tuberculosis |

||||||||||||

| Category 4 (active TB excluded)§ |

81.1 (73.3 to 87.4) | 107/132 | 73.5 (65.1 to 80.8) | 97/132 | 71.8 (63.8 to 79.1) | 102/142 | 0.07 | 0.76 | 69.3 (60.9 to 76.9) | 95/137 | 0.03 | 0.45 |

| Category 4D (active TB excluded, TST negative, no risk factors for latent TB infection)° |

100% ∥ | 25/25 | 100% ∥ | 25/25 | 85.7 (63.7 to 97.0) | 18/21 | 84.2 (60.4 to 96.6) | 16/19 | ||||

| Predictive value | ||||||||||||

| Positive predictive value |

83.1 (76.1 to 88.8) | 123/148 | 78.8 (71.8 to 84.8) | 130/165 | 80.0 (73.8 to 85.3) | 160/200 | 0.46 | 0.78 | 79.9 (73.8 to 85.1) | 167/209 | 0.45 | 0.79 |

| Negative predictive value |

77.0 (69.1 to 83.4) | 107/139 | 79.5 (71.3 to 86.3) | 97/122 | 78.5 (70.4 to 85.2) | 102/130 | 0.77 | 0.84 | 82.6 (74.4 to 89.0) | 95/115 | 0.27 | 0.54 |

| Likelihood ratios | ||||||||||||

| Positive likelihood ratio |

4.19 (2.92 to 6.02) | 287 | 3.16 (2.36 to 4.27) | 287 | 3.02 (2.31 to 3.96) | 330 | 0.15 | 0.97 | 2.91 (2.25 to 3.77) | 324 | 0.11 | 0.68 |

| Negative likelihood ratio |

0.25 (0.19 to 0.35) | 287 | 0.22 (0.15 to 0.32) | 287 | 0.21 (0.15 to 0.30) | 330 | 0.46 | 0.86 | 0.15 (0.10 to 0.24) | 324 | 0.06 | 0.19 |

Abbreviations: millimetres (mm), tuberculosis (TB), tuberculin skin test (TST)

Data are for patients in whom results are available for the test in question, and in whom a definite diagnosis was available (n≤348). Values are for confirmed and highly-probable TB unless stated otherwise

TST - Tuberculin skin test using 15 mm cut-off (Mantoux ≥15mm or Heaf grade 3-4 considered positive)

TST - Tuberculin skin test using stratified-10 mm cut-off (≥10mm or grade 2-4 Heaf scored as positive in Bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccinated individuals, or if unvaccinated ≥15 mm or grade 3-4 Heaf)

Chi squared P value for difference between TST 15 mm and ELISpot

Chi squared P value for difference between TST 15 mm and ELISpotPLUS

Chi squared P value for difference between stratified-10 mm TST and ELISpot

Chi squared P value for difference between stratified-10 mm TST and ELISpotPLUS

Proportion of patients with negative results amongst those in whom active tuberculosis was excluded

Proportion of patients with negative results amongst those in whom active tuberculosis was excluded, tuberculin skin testing was negative and in whom no risk factors for latent TB infection were identified

The definition of category 4D requires skin test is negative if performed

In a sensitivity analysis to investigate whether inclusion of highly probable cases (category 2, which was biased in favor of the tuberculin skin test because a diagnosis of highly probable tuberculosis was based in part on skin test results) affected performance estimates, we re-estimated sensitivity by using only culture-confirmed cases (category 1). Sensitivities were 91% (CI, 85% to 95%) with ELISpotPLUS, 87% (CI, 80% to 92%) with standard ELISpot, 79% (CI, 71% to 86%) with tuberculin skin testing using the 15-mm threshold, and 82 % (CI, 74% to 89%) with the stratified 10-mm threshold. The ELISpotPLUS assay was more sensitive than tuberculin skin testing using either the 15-mm (P = 0.005) or the stratified 10-mm threshold (P = 0.03) (Table 4).

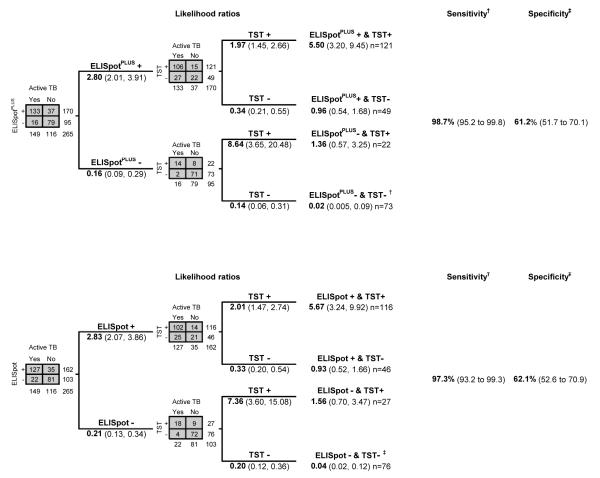

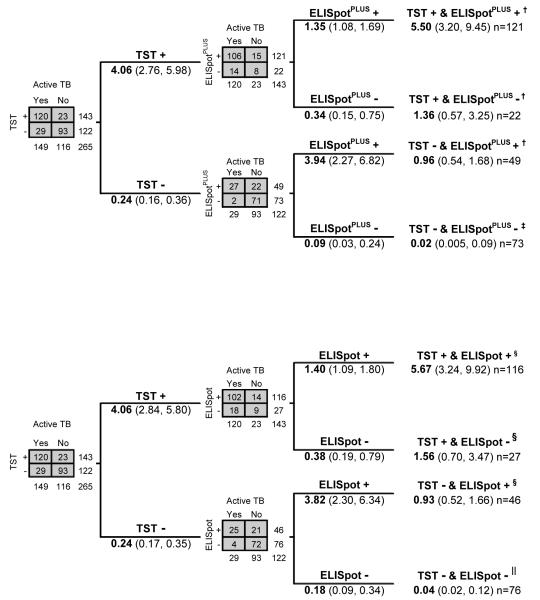

Tuberculin skin testing and ELISpot had higher sensitivity when used in combination. For culture-confirmed or highly probable diagnoses of tuberculosis, sensitivity of ELISpotPLUS with tuberculin skin testing was 99% (CI, 95% to 100%) and standard ELISpot with tuberculin skin testing was 97% (CI, 93% to 99%) (Figure 2). A negative result on both tests was associated with likelihood ratios of 0.02 (CI, 0 to 0.06) for ELISpotPLUS with tuberculin skin testing and 0.04 (CI, 0.01 to 0.10) for standard ELISpot with tuberculin skin testing. Positive results from both tests provided likelihood ratios of 5.5 (CI, 3.2 to 9.5) for ELISpotPLUS with tuberculin skin testing and 5.7 (CI, 3.3 to 9.9) for standard ELISpot with tuberculin skin testing, whereas discordant results (likelihood ratios, 0.93 to 1.56) had no diagnostic value. Figure 2 shows sequential likelihood ratios when ELISpot assays are followed by tuberculin skin testing, and Appendix Figure 2 (available at www.annals.org) shows corresponding results when tuberculin skin testing is used first.

Figure 2.

Likelihood ratios, sensitivities, and specificities of tests used in combination, using ELISpot or ELISpotPLUS first. Data are for patients in whom results on both tests were available (n = 265). Except where stated, values are likelihood ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Tuberculin skin test thresholds for positivity were induration ≥15 mm on the Mantoux test or grade 3 to 4 on the Heaf test. ELISpot = enzyme-linked immunospot incorporating early secretory antigenic target-6 and culture filtrate protein-10; ELISpotPLUS = enzyme-linked immunospot incorporating early secretory antigenic target-6, culture filtrate protein-10 and Rv3879c; TB = tuberculosis; TST = tuberculin skin testing. Top. ELISpot followed by TST. *Combined sensitivity of 1 or more positive results from tests used in combination, 97% (CI, 93% to 99%). †Combined specificity for a double negative result from tests used in combination, 62% (CI, 53% to 71%). Bottom. ELISpotPLUS followed by TST. ‡Combined sensitivity of 1 or more positive results from tests used in combination, 99% (CI, 95% to 100%). §Combined specificity for a double negative result from tests used in combination, 61% (CI, 52% to 70%).

The high sensitivity of the combined tests reflects the fact that false-negative tuberculin skin test results and false-negative ELISpot results occurred in different patient populations. In univariate analysis among culture-confirmed and highly probable cases, the presence of factors associated with cutaneous anergy (5) or risk of progression from latent infection to active tuberculosis (35) was associated with false-negative tuberculin skin test results (P = 0.001) but not with false-negative ELISpot results (P = 0.55). Specifically, 28% (CI, 11% to 44%) of patients with false-negative tuberculin skin test results had factors associated with cutaneous anergy (3 had diabetes and 3 were HIV-positive), compared with 5.0% (CI, 1.1% to 8.8%) of those with true-positive results. Eleven patients with tuberculosis were deemed immunocompromised on the basis of being HIV-positive (8 patients) or receiving long-term corticosteroid treatment (3 patients); 10 had positive ELISpot results and all 11 had positive ELISpotPLUS results. Neither age nor presence of any comorbid condition was associated with false-negative tuberculin skin test or ELISpot results (P > 0.11 in all cases).

The sensitivity of culture was 79% (CI, 73% to 85%) for confirmed and highly probable tuberculosis, which was lower than that of both ELISpot assays; this difference was significant for ELISpotPLUS (P = 0.005). Microscopy had a sensitivity of 39% (CI, 32% to 46%). Microbiological techniques had lower sensitivity in extrapulmonary disease than in pulmonary disease (culture, 53% [CI, 39% to 67%] vs. 89% [CI, 83% to 94%], respectively [P < 0.001]; microscopy, 14% (CI, 5.5% to 26%) vs. 49% (CI, 40% to 58%), respectively [P < 0.001]), whereas ELISpotPLUS showed a nonsignificantly higher sensitivity in extrapulmonary disease (94% [CI, 84% to 99%]) than in pulmonary disease (88% [CI, 81% to 93%]) (P = 0.19). Among patients with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis, the sensitivity of sputum microscopy with ELISpotPLUS was 94% (CI, 89% to 98%) for culture-confirmed and highly probable cases, generating a negative likelihood ratio of 0.10 and a negative predictive value of 90%, compared with a sensitivity of 78% (CI, 69% to 85%) for microscopy combined with tuberculin skin testing (P < 0.001).

Specificity of ELISpotPLUS was 69% (CI, 61% to 77%) for active disease in all category 4 patients, which was lower than the specificity of tuberculin skin testing (81% [CI, 73% to 87%]; P = 0.03). Although ELISpotPLUS gave more diagnostic negative likelihood ratios and negative predictive values than tuberculin skin testing, positive likelihood ratios and positive predictive values were somewhat lower, most likely because of detection of latent infection in category 4 patients; this finding is consistent with the 84% (CI, 60% to 97%) specificity of ELISpotPLUS calculated by using category 4D patients (who were considered least likely to have latent infection). Specificity of standard ELISpot was similar to ELISpotPLUS (Table 4). Three of 21 category 4D patients had false-positive results by standard ELISpot, and 3 of 19 had false-postive results by ELISpotPLUS. All 3 individuals falsely-positive by ELISpotPLUS were United Kingdom-born white persons with 0 mm of induration on the Mantoux test, and 2 were 75 years of age or older. Only 2 category 4D patients who were negative by standard ELISpot were positive to any of the new antigens; both responded to Rv3873 alone. Thus, inclusion of Rv3879c alone in ELISpotPLUS enhanced diagnostic sensitivity without compromising specificity.

Our comparison of the Heaf test and the Mantoux test with a 15-mm induration threshold for patients with culture-confirmed and highly probable cases of tuberculosis revealed a nonsignificant increase in sensitivity for the Heaf test (86% [CI, 74% to 82%] for the Heaf test vs. 76% [CI, 66% to 84%] for the Mantoux test; P = 0.14) and a higher specificity for the Mantoux test (66% [CI, 46% to 82%]) for the Heaf test vs. 85% [CI, 77% to 92%] for the Mantoux test; P = 0.02) (subgroup data provided on request). Receiver-operator characteristic analysis indicated that the area under the curve for both skin test formats was identical at 0.84. Subgroup analysis of combined use of standard ELISpot or ELISpotPLUS followed by Mantoux testing (for the 184 patients who received Mantoux testing) gave similar final likelihood ratios to those observed in the whole study population tested with Mantoux or Heaf methods (265 patients; subgroup data provided on request).

Overall, 4.7% of positive results on standard ELISpot or ELISpotPLUS were dependent on a single peptide pool response of 5 to 10 spot-forming cells per well. These results might therefore be considered borderline positive.

Discussion

This prospective study has defined a role for T-cell–based interferon-γ release assay testing in the diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected tuberculosis. The 89% sensitivity of ELISpotPLUS for a diagnosis of culture-confirmed or highly probable tuberculosis was higher than that of the standard ELISpot, tuberculin skin testing, and culture. The combined sensitivity of ELISpotPLUS and tuberculin skin testing in confirmed and highly probable cases was 99%.

The negative likelihood ratio of 0.15 with ELISpotPLUS means that a negative result would reduce the odds of tuberculosis by 6.5-fold, which allows it to be used as a rule-out test in patients with a moderate or low pretest probability of tuberculosis. Given the high pretest probability of tuberculosis (0.50) in our patient population (patients attending urban infectious disease units), the negative predictive value of ELISpotPLUS alone was modest at 83%. However, the 99% combined sensitivity of tuberculin skin testing and ELISpotPLUS and the corresponding negative likelihood ratio of 0.02 allow the combined use of these assays as a rule-out test for tuberculosis, even in populations with high pretest probabilities, such as our study sample. Pretest probabilities in other settings, such as general medical or primary care clinics in low-prevalence countries, will be much lower, and the negative predictive value of ELISpotPLUS, alone or in combination with skin testing, will be correspondingly higher. The higher sensitivity of ELISpotPLUS compared with standard ELISpot was entirely attributable to the addition of 1 antigen, Rv3879c (to which Rv3873 and Rv3878 provided no further incremental sensitivity), which supports inclusion of Rv3879c in T-cell–based interferon-γ release assays.

Analysis of tuberculin skin testing using the lower 10-mm induration threshold in patients not vaccinated with bacille Calmette–Guérin showed a nonsignificant increase in sensitivity and decrease in specificity. Whereas ELISpotPLUS was not significantly more sensitive than skin testing with the stratified 10-mm threshold in patients with confirmed and highly probable tuberculosis, it was significantly more sensitive in the patients with culture-confirmed disease. This is probably because the diagnosis of highly probable tuberculosis was based in part on skin test results, which biases results in favor of the skin test.

Our results are likely generalizable to clinical units evaluating suspected tuberculosis patients in other low-prevalence countries because we performed our study in routine clinical practice and included a wide spectrum of clinical cases and alternative diagnoses (36, 37). This may also account for the lower sensitivity of standard ELISpot in our study compared with earlier, smaller studies of more selected patient groups (16, 18, 38). Because our population comprised relatively few immunocompromised patients, our results cannot be generalized to populations with a higher prevalence of HIV co-infection, although previous studies of larger numbers of patients with tuberculosis who were co-infected with HIV suggest that ELISpot has high sensitivity in this group (25, 28). Our study population was predominantly South Asian and black, and further studies are required in other ethnic groups. Results will be less generalizable outside low-prevalence countries, because the utility of ELISpot in endemic regions will be limited by higher background rates of latent tuberculosis (29, 39). This reduces the utility of a positive result; however, negative results (although proportionally fewer) would still be useful to rule out a diagnosis of tuberculosis (8, 25, 40).

Any T-cell–based test with a high sensitivity for M. tuberculosis infection will detect cases of latent infection among patients who are suspected of having tuberculosis but in whom active tuberculosis has been excluded. Because our study population predominantly comprised patients with suspected tuberculosis from ethnic groups with a high prevalence of tuberculosis and latent tuberculosis, patients without active tuberculosis had a much higher risk of latent infection than would healthy control patients selected for very low risk of infection. This explains the 66% to 86% specificities of ELISpot and tuberculin skin testing when used as markers of active tuberculosis. Hence, when used to support a diagnosis of active tuberculosis, immune-based tests of infection should be interpreted in the context of the overall clinical picture and diagnostic work-up (40), as is recognized for tuberculin skin testing.

Given that culture remains the diagnostic gold standard and is required for identifying drug resistance, we believe our findings will have the following effects on clinical decision making. First, a negative ELISpotPLUS result can assist in excluding tuberculosis when the pretest probability is low-to-moderate. When pretest probabilities are higher, combined use of ELISpotPLUS and tuberculin skin testing excludes tuberculosis with a greater degree of certainty (Figure 2). The likelihood ratio of 0.02 to 0.04 refines a pretest probability of 50% to a posttest probability of approximately 2% (41) in patients with double-negative results, who constituted over a quarter of those tested in our study. Conversely, a positive ELISpotPLUS (or standard ELISpot) result with a corresponding likelihood ratio of 2.8 is of limited value. However, in patients with positive results on both ELISpot and the tuberculin skin test, who constituted nearly half of those tested, the corresponding likelihood ratio of 5.5 increased the probability of active tuberculosis by approximately 30% (41). Thus, double-positive results may help guide decisions about early initiation of presumptive treatment in severe disease while awaiting culture results and in extrapulmonary disease, in which culture is frequently negative. Combined testing also generates some discordant results (Figure 2). In these cases, which amounted to one quarter of persons tested, the near-unity likelihood ratios do not alter pretest probabilities and do not contribute to the diagnostic work-up.

The rate of indeterminate ELISpot results in our study was similar to the 3% to 4% observed in other studies (42, 43) and less than the 11% to 21% indeterminate rates observed with whole-blood ELISA in routine practice (42, 44). Indeterminate ELISA results are associated with immunosuppressive therapies or conditions (42, 44), but no such association was seen for ELISpot in this or other studies (25, 42, 43, 45, 46). Moreover, the proportion of patients with tuberculosis was no higher among those with indeterminate results. As expected, false-negative skin test results were associated with factors known to cause anergy or progression to active disease. In contrast, these factors did not confound the ELISpot results, consistent with previous findings (10, 15, 42).

The 99% combined sensitivity of tuberculin skin testing and ELISpot reflects the fact that patients who had a false-negative result on one test were distinct from those had a false-negative result on the other. This implies that distinct immunologic processes underlie failure of these different, yet complementary, immune-based tests.

The main weakness of our study arises from the problem of differing standards for tuberculin skin testing. Standards vary worldwide, differing by type of tuberculin, production standards, method of administration, dose, and skin test cutoff points (13, 23, 24, 31, 35, 47). Where possible, we used a 10–tuberculin unit PPD–Siebert Mantoux test (in accordance with the United Kingdom standard at the time) and corresponding cutoff points for induration. In one quarter of patients, a Heaf test was used for logistical reasons. When standard thresholds for Mantoux test equivalence were used (23, 24), the Heaf test showed a nonsignificant increase in diagnostic sensitivity and a significant decrease in specificity relative to the Mantoux test. Subgroup analysis of patients who had Mantoux testing showed that conclusions for combined testing with ELISpot or ELISpotPLUS followed by Mantoux testing were similar to those for the study population as a whole. Parallel testing with the alternative whole-blood ELISA T-cell–based interferon-γ release assay would have been of interest, but neither this test nor the T-SPOT.TB (which is based on the standard ELISpot used here) was available when our study began. The modest sample size, limited number of immunocompromised patients, and lack of a definitive gold standard are also limitations of our study. Because many patients with tuberculosis are culture-negative (48), a microbiological gold standard used alone is too insensitive to evaluate new diagnostic tests. We therefore included highly probable cases in our composite reference standard, which better reflects the clinically relevant population, and our sensitivity analysis confirmed that estimates based on the composite reference standard were similar to those based on the microbiological reference standard. Finally, because this is only the second study to evaluate Rv3879c (21) and the first prospective study, further validation of its incremental sensitivity is required.

In summary, we found that ELISpotPLUS was a sensitive and clinically useful diagnostic test for evaluation of patients with suspected tuberculosis. Incorporation of a novel antigen, Rv3879c, conferred improved sensitivity over standard ELISpot. Combined use of tuberculin skin testing with either ELISpotPLUS or ELISpot enabled rapid exclusion of tuberculosis in patients with moderate to high probability of infection.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the study participants; Lemuel Mallari and Sarah Gooding, for collection and processing of some samples; and Muhunthan Thillai, for critical appraisal and revision of the final manuscript.

Grant Support By the Wellcome Trust (Dr. Lalvani is a Wellcome Senior Research Fellow in Clinical Science), the Sir Halley Stewart Trust (Dr. Dosanjh’s studentship), a Wellcome Trust PhD Prize Studentship (Dr. Millington), and a United Kingdom Department of Health Senior Fellowship in Evidence Synthesis (Dr. Deeks).

Abbreviations

- (ELISA)

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- (ELISpot)

enzyme-linked immunospot

- (ELISpotPLUS)

enzyme-linked immunospot with additional antigens

- (M. tuberculosis)

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- (TST)

tuberculin skin test

Appendix

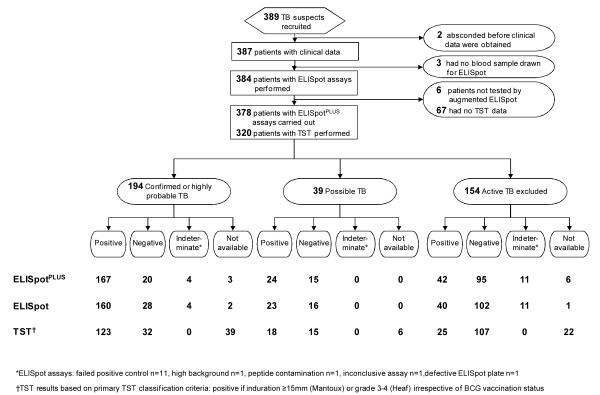

Appendix Figure 1.

Study flow diagram, stratified by final diagnosis and then by test result. These are the same data shown in Figure 1 but displayed in a different manner to allow scrutiny of the entire raw data set. BCG = bacille Calmette–Guérin; ELISpot = enzyme-linked immunospot assay incorporating early secretory antigenic target-6 and culture filtrate protein-10; ELISpotPLUS = enzyme-linked immunospot assay incorporating early secretory antigenic target-6, culture filtrate protein-10 and Rv3879c; TB = tuberculosis; TST= tuberculin skin testing. *Results not available because of history of previous TB (clinically contraindicated) (45 patients), patient did not return for reading (8 patients), result not recorded (8 patients), reason unknown (3 patients), patient death (1 patient), test performed elsewhere (1 patient), or patient declined consent (1 patient). †Results indeterminate because of no achievement of positive control (11 patients), high background (1 patient), peptide contamination (1 patient), inconclusive assay (1 patient), or defective ELISpot plate (1 patient). ‡Tuberculin skin test results were based on a 15-mm cutoff point and considered positive if induration was ≥15 mm on the Mantoux test or grade 3 to 4 on the Heaf test regardless of BCG vaccination status.

Appendix Figure 2.

Likelihood ratios, sensitivities, and specificities of tests used in combination for diagnostic evaluation, using TST as the first test. Data are for patients in whom results on both tests were available (n = 265). Except where stated, numbers are likelihood ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Tuberculin skin test thresholds for positivity were induration ≥15 mm on the Mantoux test or grade 3 to 4 on the Heaf test. ELISpot = enzyme-linked immunospot incorporating early secretory antigenic target-6 and culture filtrate protein-10; ELISpotPLUS = enzyme-linked immunospot incorporating early secretory antigenic target-6, culture filtrate protein-10 and Rv3879c; TB = tuberculosis; TST = tuberculin skin testing. Top. TST followed by ELISpot. *Combined sensitivity of 1 or more positive results from tests used in combination, 97% (CI, 93% to 99%). †Combined specificity for a double negative result from tests used in combination, 62% (CI, 53% to 71%). Bottom. TST followed by ELISpotPLUS. ‡Combined sensitivity of 1 or more positive results from tests used in combination, 99% (CI, 95% to 100%). §Combined specificity for a double negative result from tests used in combination, 61% (CI, 52% to 70%).

Footnotes

Potential Financial Conflicts of Interest Professor Lalvani is a named inventor for several patents underpinning T cell-based diagnosis filed by the University of Oxford since 1996. Regulatory approval and commercialization of the Lalvani ELISpot (T-SPOT.TB) has been undertaken by a spin-out company of the University of Oxford (Oxford Immunotec Ltd, Oxford, UK), in which Professor Lalvani has a share of equity and to which he acts as advisor in a non-executive capacity. The University of Oxford has a share of equity in Oxford Immunotec Ltd.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is the prepublication, author-produced version of a manuscript accepted for publication in Annals of Internal Medicine. This version does not include post-acceptance editing and formatting. The American College of Physicians, the publisher of Annals of Internal Medicine, is not responsible for the content or presentation of the author-produced accepted version of the manuscript or any version that a third party derives from it. Readers who wish to access the definitive published version of this manuscript and any ancillary material related to this manuscript (e.g., correspondence, corrections, editorials, linked articles) should go to www.annals.org or to the print issue in which the article appears. Those who cite this manuscript should cite the published version, as it is the official version of record.

References

- 1.The STOP TB Partnership . The global plan to stop TB, 2006–2015. World Health Organization; Geneva: [on 2 January 2008]. 2006. Acessed at www.who.int/tb/publications/global_plan_to_stop_tb/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schluger NW, Perez D, Liu YM. Reconstitution of immune responses to tuberculosis in patients with HIV infection who receive antiretroviral therapy. Chest. 2002;122:597–602. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.2.597. [PMID: 12171838] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steingart KR, Henry M, Ng V, Hopewell PC, Ramsay A, Cunningham J, et al. Fluorescence versus conventional sputum smear microscopy for tuberculosis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:570–81. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70578-3. [PMID: 16931408] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dinnes J, Deeks J, Kunst H, Gibson A, Cummins E, Waugh N, et al. A systematic review of rapid diagnostic tests for the detection of tuberculosis infection. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11:1–196. doi: 10.3310/hta11030. [PMID: 17266837] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huebner RE, Schein MF, Bass JB., Jr The tuberculin skin test. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:968–75. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.6.968. [PMID: 8110954] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menzies D. Interpretation of repeated tuberculin tests. Boosting, conversion, and reversion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:15–21. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9801120. [PMID: 9872812] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menzies D, Pai M, Comstock G. Meta-analysis: new tests for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: areas of uncertainty and recommendations for research. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:340–54. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00006. [PMID: 17339619] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lalvani A. Diagnosing tuberculosis infection in the 21st century: new tools to tackle an old enemy. Chest. 2007;131:1898–906. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2471. [PMID: 17565023] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pai M, Riley LW, Colford JM., Jr Interferon-gamma assays in the immunodiagnosis of tuberculosis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:761–76. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01206-X. [PMID: 15567126] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richeldi L. An update on the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:736–42. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1516PP. [PMID: 16799073] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behr MA, Wilson MA, Gill WP, Salamon H, Schoolnik GK, Rane S, et al. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science. 1999;284:1520–3. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1520. [PMID: 10348738] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richeldi L, Ewer K, Losi M, Roversi P, Fabbri LM, Lalvani A. Repeated tuberculin testing does not induce false positive ELISPOT results [Letter] Thorax. 2006;61:180. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.049759. [PMID: 16443712] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mori T, Sakatani M, Yamagishi F, Takashima T, Kawabe Y, Nagao K, et al. Specific detection of tuberculosis infection: an interferon-gamma-based assay using new antigens. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:59–64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-179OC. [PMID: 15059788] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arend SM, Thijsen SF, Leyten EM, Bouwman JJ, Franken WP, Koster BF, et al. Comparison of two interferon-gamma assays and tuberculin skin test for tracing tuberculosis contacts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:618–27. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1099OC. [PMID: 17170386] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lalvani A, Pathan AA, Durkan H, Wilkinson KA, Whelan A, Deeks JJ, et al. Enhanced contact tracing and spatial tracking of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection by enumeration of antigen-specific T cells. Lancet. 2001;357:2017–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05115-1. [PMID: 11438135] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lalvani A, Pathan AA, McShane H, Wilkinson RJ, Latif M, Conlon CP, et al. Rapid detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection by enumeration of antigen-specific T cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:824–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.4.2009100. [PMID: 11282752] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ewer K, Deeks J, Alvarez L, Bryant G, Waller S, Andersen P, et al. Comparison of T-cell-based assay with tuberculin skin test for diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in a school tuberculosis outbreak. Lancet. 2003;361:1168–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12950-9. [PMID: 12686038] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meier T, Eulenbruch HP, Wrighton-Smith P, Enders G, Regnath T. Sensitivity of a new commercial enzyme-linked immunospot assay (T SPOT-TB) for diagnosis of tuberculosis in clinical practice. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;24:529–36. doi: 10.1007/s10096-005-1377-8. [PMID: 16133410] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazurek GH, Jereb J, Lobue P, Iademarco MF, Metchock B, Vernon A, Division of Tuberculosis Elimination. National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Guidelines for using the QuantiFERON-TB Gold test for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:49–55. [PMID: 16357824] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions . Tuberculosis: clinical diagnosis and management of tuberculosis, and measures for its prevention and control. Royal College of Physicians; London: 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu XQ, Dosanjh D, Varia H, Ewer K, Cockle P, Pasvol G, et al. Evaluation of T-cell responses to novel RD1- and RD2-encoded Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene products for specific detection of human tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun. 2004;72:2574–81. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2574-2581.2004. [PMID: 15102765] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rose AM, Watson JM, Graham C, Nunn AJ, Drobniewski F, Ormerod LP, et al. Public Health Laboratory Service/British Thoracic Society/Department of Health Collaborative Group Tuberculosis at the end of the 20th century in England and Wales: results of a national survey in 1998. Thorax. 2001;56:173–9. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.3.173. [PMID: 11182007] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Control and prevention of tuberculosis in the United Kingdom: code of practice 2000. Joint Tuberculosis Committee of the British Thoracic Society. Thorax. 2000;55:887–901. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.11.887. [PMID: 11050256] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department of Health . Immunisation against infectious disease. HMSO; London: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liebeschuetz S, Bamber S, Ewer K, Deeks J, Pathan AA, Lalvani A. Diagnosis of tuberculosis in South African children with a T-cell-based assay: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2004;364:2196–203. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17592-2. [PMID: 15610806] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pathan AA, Wilkinson KA, Klenerman P, McShane H, Davidson RN, Pasvol G, et al. Direct ex vivo analysis of antigen-specific IFN-gamma-secreting CD4 T cells in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected individuals: associations with clinical disease state and effect of treatment. J Immunol. 2001;167:5217–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5217. [PMID: 11673535] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soysal A, Millington KA, Bakir M, Dosanjh D, Aslan Y, Deeks JJ, et al. Effect of BCG vaccination on risk of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children with household tuberculosis contact: a prospective community-based study. Lancet. 2005;366:1443–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67534-4. [PMID: 16243089] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chapman AL, Munkanta M, Wilkinson KA, Pathan AA, Ewer K, Ayles H, et al. Rapid detection of active and latent tuberculosis infection in HIV-positive individuals by enumeration of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific T cells. AIDS. 2002;16:2285–93. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200211220-00008. [PMID: 12441800] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lalvani A, Nagvenkar P, Udwadia Z, Pathan AA, Wilkinson KA, Shastri JS, et al. Enumeration of T cells specific for RD1-encoded antigens suggests a high prevalence of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in healthy urban Indians. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:469–77. doi: 10.1086/318081. [PMID: 11133379] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richeldi L, Ewer K, Losi M, Bergamini BM, Roversi P, Deeks J, et al. T cell-based tracking of multidrug resistant tuberculosis infection after brief exposure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:288–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200403-307OC. [PMID: 15130907] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diagnostic Standards and Classification of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children This official statement of the American Thoracic Society and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. This statement was endorsed by the Council of the Infectious Disease Society of America, September 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1376–95. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.4.16141. [PMID: 10764337] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan SF, Deeks JJ, Macaskill P, Irwig L. Three methods to construct predictive models using logistic regression and likelihood ratios to facilitate adjustment for pretest probability give similar results. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(1):52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.02.012. [PMID: 18083462] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knottnerus JA. Application of logistic regression to the analysis of diagnostic data: exact modeling of a probability tree of multiple binary variables. Med Decis Making. 1992;12:93–108. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9201200202. [PMID: 1573985] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albert A. On the use and computation of likelihood ratios in clinical chemistry. Clin Chem. 1982;28:1113–9. [PMID: 7074890] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. This is a Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This statement was endorsed by the Council of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. (IDSA), September 1999, and the sections of this statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:S221–47. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.supplement_3.ats600. [PMID: 10764341] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Sackett DL. Users’ guides to the medical literature. III. How to use an article about a diagnostic test. B. What are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1994;271:703–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.9.703. [PMID: 8309035] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Small PM, Perkins MD. More rigour needed in trials of new diagnostic agents for tuberculosis. Lancet. 2000;356:1048–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02724-0. [PMID: 11009137] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JY, Choi HJ, Park IN, Hong SB, Oh YM, Lim CM, et al. Comparison of two commercial interferon-gamma assays for diagnosing Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:24–30. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00016906. [PMID: 16611658] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kang YA, Lee HW, Hwang SS, Um SW, Han SK, Shim YS, et al. Usefulness of whole-blood interferon-gamma assay and interferon-gamma enzyme-linked immunospot assay in the diagnosis of active pulmonary tuberculosis. Chest. 2007;132:959–65. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2805. [PMID: 17505029] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barnes PF. Diagnosing latent tuberculosis infection: the 100-year upgrade [Editorial] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:807–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.4.ed0201c. [PMID: 11282742] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Refining clinical diagnosis with likelihood ratios. Lancet. 2005;365:1500–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66422-7. [PMID: 15850636] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferrara G, Losi M, D’Amico R, Roversi P, Piro R, Meacci M, et al. Use in routine clinical practice of two commercial blood tests for diagnosis of infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a prospective study. Lancet. 2006;367:1328–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68579-6. [PMID: 16631911] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Piana F, Codecasa LR, Cavallerio P, Ferrarese M, Migliori GB, Barbarano L, et al. Use of a T-cell-based test for detection of tuberculosis infection among immunocompromised patients. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:31–4. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00110205. [PMID: 16540502] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferrara G, Losi M, Meacci M, Meccugni B, Piro R, Roversi P, et al. Routine hospital use of a new commercial whole blood interferon-gamma assay for the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:631–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-196OC. [PMID: 15961696] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dheda K, Lalvani A, Miller RF, Scott G, Booth H, Johnson MA, et al. Performance of a T-cell-based diagnostic test for tuberculosis infection in HIV-infected individuals is independent of CD4 cell count. AIDS. 2005;19:2038–41. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000191923.08938.5b. [PMID: 16260914] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piana F, Codecasa LR, Besozzi G, Migliori GB, Cirillo DM. Use of commercial interferon-gamma assays in immunocompromised patients for tuberculosis diagnosis [Letter] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:130. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.173.1.130. author reply 130-1. [PMID: 16368794] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee E, Holzman RS. Evolution and current use of the tuberculin test. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:365–70. doi: 10.1086/338149. [PMID: 11774084] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thwaites GE, Chau TT, Stepniewska K, Phu NH, Chuong LV, Sinh DX, et al. Diagnosis of adult tuberculous meningitis by use of clinical and laboratory features. Lancet. 2002;360:1287–92. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11318-3. [PMID: 12414204] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]