Abstract

Background

Recent work has highlighted important relationships among Conduct Disorder (CD), Substance Use Disorders (SUD), and Bipolar Disorder (BPD) in youth. However because BPD and CD are frequently comorbid in the young, the impact of CD in mediating SUD in BPD youth remains unclear.

Methods

105 adolescents with BPD (mean±SD=13.6±2.50 years) and 98 controls (13.7±2.10 years) were comprehensively assessed with a structured psychiatric diagnostic interview for psychopathology and SUD.

Results

Among BPD youth, those with CD were more likely to report cigarette smoking and/or SUD than youth without CD. However, CD preceding SUD or cigarette smoking did not significantly increase the subsequent risk of SUD or cigarette smoking. Adolescents with BPD and CD were significantly more likely to manifest a combined alcohol plus drug use disorder compared to subjects with BPD without CD (χ2=9.89, p= 0.001).

Conclusions

While BPD is a risk factor for SUD and cigarette smoking in a sample of adolescents, comorbidity with pre-existing CD does not increase the risk for SUD. Further follow-up of this sample through the full risk of SUD into adulthood is necessary to confirm these findings.

Introduction

Juvenile BPD in its various forms affects from 1–4% of pediatric groups1 with up to one-fifth of psychiatrically referred children and adolescent psychiatric outpatients manifesting BPD2, 3. Convergent evidence documents that BPD is a substantial cause of morbidity and disability among youth including high rates of hospitalization, disruption of the family environment, and severe psychosocial disability4–10. Systematic studies of BPD youth have found high rates of psychiatric comorbidity3, 10–16. Among the most concerning comorbidities in juvenile onset BPD is the link with cigarette smoking and substance use disorders (SUD; including drug or alcohol abuse or dependence)17–20.

In independent samples we have shown that juvenile BPD is a risk for cigarette smoking and SUD17–20, however the role of CD in accounting for these findings has not been fully explored. This issue is important considering the high comorbidity between BPD and CD3, 11, 21–25,26, 27 and the well documented association between CD and SUD, particularly in context to mood dysregulation28, 29 30–33. Further understanding of the nature of the associations between BPD, CD and SUD is of high relevance. For example, since heterogeneity exists in SUD, it may be that CD in BPD predicts a different risk, onset, severity or course of SUD. The delineation of SUD risk in BPD attending to CD is of great clinical and public health interest. If targeted, child-based psychopathology can be identified early with heightened surveillance and intervention, which may result in reduced SUD. Also, scientifically parsing out the heterogeneity of BPD and SUD may provide important data on developmental etiologies and subtypes of SUD34. The main aim of this study was to evaluate the associations between BPD and SUD attending to the comorbidity with CD. To this end, we examined the risk for SUD associated with CD, BPD, and the combination of both in a large sample of adolescents with and without BPD. Based on the literature, we hypothesized that CD will mediate the association between BPD and SUD.

METHODS

Subjects

The current study is based on assessments of our ongoing, controlled, family-based study of BPD adolescents. The methods of the study are described in detail elsewhere20. Briefly, we ascertained 105 bipolar adolescent probands and 98 non-mood disordered control subjects and their first-degree relatives. Subjects from both groups were recruited from the same catchment area through newspaper advertisements, Internet postings, clinical referrals to our program (BPD only), and internal postings within the Partners/Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) system. These methods were used to collect controls that would also use the Partners/MGH system if they had BPD, representing the same source population as the cases.

We included families with a child (designated the proband) between the ages of 10 and 18 and at least one parent available to complete interviews about the children. We also recruited the probands’ biological siblings, as young as the age of six. We excluded potential probands if they had been adopted or if their nuclear family was not available for study. We also excluded any youth with major sensorimotor handicaps that would impede the testing process such as paralysis, deafness, blindness, profound disorders of language such as autism, inadequate command of the English language, or a Full Scale IQ less than 70. Parents provided written informed consent for their children and children provided written assent to participate. The institutional review board at MGH approved this study and a federal certificate of confidentiality was obtained for the study.

A two-stage ascertainment procedure selected subjects. For BPD probands, the first stage assessed the diagnosis of BPD by screening all children using a telephone questionnaire conducted with their primary caregiver, which queried about symptoms of BPD and study exclusion criteria. The second stage confirmed the diagnosis of BPD using a structured psychiatric interview, as described below. Only subjects who received a positive diagnosis at both stages were included in the study sample. Also, we screened non-mood disordered controls in two stages. First, control primary caregivers responded to the telephone questionnaire, then eligible controls meeting study entry criteria were recruited for the study and received the diagnostic assessment with a structured interview. Only subjects classified as not having any mood disorder at both stages were included in the control group. We excluded controls with any mood disorder because of concerns about potential “manic switching” from dysthymia or unipolar depression to BPD 23.

Assessments

All diagnostic assessments were made using DSM-IV-based structured interviews, by raters with bachelor’s or master’s degrees in psychology who had been extensively trained and supervised by the senior investigators (TW, JB). Raters were blind to the ascertainment status of the probands. Psychiatric assessments for subjects under 18 years old relied on the DSM-IV Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders-Epidemiologic Version (KSADS-E)35 and were based on independent interviews with the primary caregivers and direct interviews of probands and siblings. Psychiatric assessments for subjects 18 or older relied on the Scheduled Clinical Interview Diagnosis (SCID). For every diagnosis, information was gathered regarding the ages at onset and offset of full syndromatic criteria, and treatment history.

SUD in our analyses included any alcohol or drug (excluding nicotine) abuse or dependence. SUD, conduct disorder and smoking dependence were diagnosed based on DSM-IV criteria using the Kiddie SADS-E and SCID. All CD and smoking diagnoses used age appropriate criteria to ensure accurate diagnosis. All cases of CD were reviewed by clinicians to determine accurate diagnosis. To meet a positive diagnosis of smoking dependence, subjects under 18 needed to endorse any amount of smoking daily, whereas subjects over 18 needed to endorse smoking at least a pack of cigarettes per day. Recent evidence suggests the utility of structured interview data compared to objective data for “lifetime” SUD determination 36. Rates of disorders reported are lifetime prevalence. Duration of disorders is expressed in years based on ages of onset and offset.

All cases were presented to a committee composed of board certified child psychiatrists and licensed psychologists. Diagnoses presented for review were considered positive only if the diagnosis would be considered clinically meaningful due to the nature of the symptoms, the associated impairment, and the coherence of the clinical picture. Discrepant reports were reconciled using the most severe diagnosis from any source unless the diagnosticians suspected that the source was not supplying reliable information. In addition to assessment of abuse and dependence, subjects were queried for any use of illicit drugs during the SUD module of the structured interview. Early use of drugs or alcohol was not included in establishing diagnoses of conduct disorder. All cases of suspected drug or alcohol abuse or dependence were further reviewed with a child and adult psychiatrist with additional addiction credentials.

To assess the reliability of our diagnostic procedures, we computed kappa coefficients of agreement by having three experienced, board-certified child and adult psychiatrists diagnose subjects from audio taped interviews made by the assessment staff. Based on 500 assessments from interviews of children and adults, the median kappa coefficient was 0.98. Kappa coefficients for individual diagnoses included: major depression (1.0), mania (0.95), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; 0.88), conduct disorder (CD; 1.0), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD; 0.90), antisocial personality disorder (ASPD; 0.80), and substance use disorder (1.0). The Hollingshead Four-Factor Index was used to assess socioeconomic status (SES).

Statistical Analysis

To examine the full relationship between BPD, CD, and SUD, we conducted two separate analyses. We compared the demographic factors between those BPD subjects with and without lifetime history of CD who were in our primary analysis (Cox model). We used t-tests for meristic outcomes, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for SES, and used Pearson χ2 tests for binary outcomes.

We used the Cox proportional hazard models to assess the risk of SUD between BPD subjects with and without lifetime history of CD. Subjects who reported an onset of CD prior to or within one year of the BPD onset were dropped from all Cox analyses (n=17). Subjects were considered exposed if they reported a CD onset prior to the substance-use onset and were considered unexposed if they did not have CD or reported a CD onset following the substance-use onset. Subjects whose CD and substance-use onset were at the same time (within one year) were dropped from the Cox analysis for that outcome. Because we assessed multiple outcomes, each with its own age of onset, the number of dropped subjects varied across the different outcomes ranging from 2 for cigarette smoking to 4 for alcohol abuse and any substance use. Further information regarding this method was reported previously 37.

We also compared subjects with BPD and no CD, BPD and Late Onset CD, and BPD and Early Onset CD, defined as onset before or after age 10 using Cox proportional hazards models. Time to onset of a SUD or cigarette smoking was the primary outcome and group membership (BPD-CD, Early Onset CD, Late Onset CD) was the primary covariate.

In our secondary analysis, we used all BPD subjects in linear and logistic regression models to assess the overall association between BPD, CD, and SUD and the influence of CD on the severity of SUD. No subjects were dropped in this analysis. An alpha-level of 0.05 was used to assert statistical significance; all statistical tests are two-tailed. We calculated all statistics using STATA 10.0.

Results

Sample Characteristics

We ascertained 105 adolescents with bipolar disorder (mean age ± SD 13.6±2.50 years) and 98 controls (13.7±2.10 years). 58 (55%) of these subjects met lifetime criteria for CD; 47 (45%)-? subjects met criteria for subthreshold CD or had no CD20. Among controls, 8 (8%) subjects met lifetime criteria for CD and 4(4%) subjects met lifetime criteria for SUD. In order to test our main hypothesis, we stratified our subjects with pre-existing BPD by the presence and absence of CD. We found that subjects with BPD-CD (n=47) were significantly older at BPD onset than subjects with BPD+CD (n=41, see Table 1). We found no differences in age, SES, gender, family intactness or frequency of lifetime ADHD diagnosis (Table 1). We found a higher frequency of multiple anxiety disorders (two or more in a lifetime) in subjects with BPD+CD.

Table 1.

Demographic variables for adolescents with Bipolar Disorder stratified by Conduct Disorder (n=88)

| BPD-CD N=47 Mean | BPD+CD* N=41 Mean | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject’s Age (yrs) | 13.11 ± 2.25 | 14.05 ± 2.47 | −1.87 | 0.06 |

| BPD Onset (yrs) | 8.76 ± 3.57 | 7.10 ± 3.64 | 2.15 | 0.03 |

| Mean | Mean | z | p | |

| SES | 2.20 ± 1.26 | 1.88 ± 1.04 | 0.93 | 0.35 |

| N (%) | N (%) | χ2 | p | |

| Gender (% male) | 30 (64) | 29 (71) | 0.47 | 0.50 |

| Family Intactness | 30 (64) | 20 (49) | 2.02 | 0.16 |

| DSM-IV ADHD (past) | 37 (79) | 28 (68) | 4.43 | 0.11 |

| Multiple Anxiety Disorders | 26 (56) | 32 (78) | 5.04 | 0.03 |

BPD preceded CD for all subjects with BPD+CD

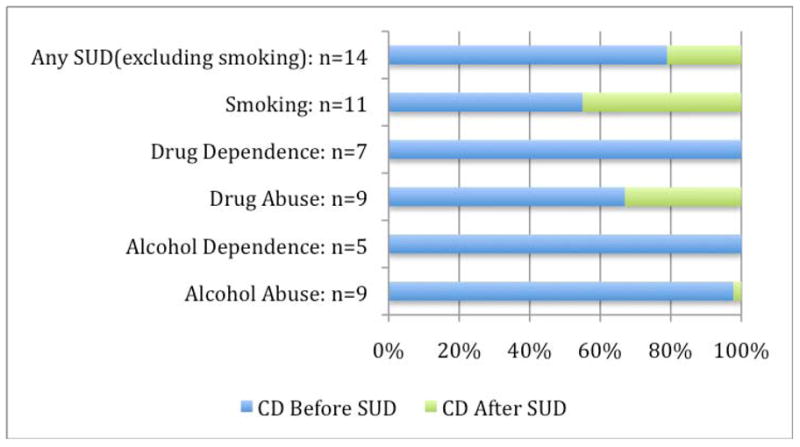

We also found that most BPD+CD subjects had their CD onset prior to any SUD or cigarette-smoking onset. For all categories of SUD and cigarette smoking, at least 50% of subjects had CD before SUD (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Subjects classified by onset of CD with respect to SUD (n=41)

Risk of SUD

We examined the risk that pre-existing CD beget on subsequent SUD in adolescents with BPD using Cox proportional hazard models to control for age, SES, family history of BPD, and family history of SUD. Specifically stratifying our youth with BPD by the presence or absence of CD pre-existing SUD, we did not find any significant difference in risk between the two groups (Table 2). When we repeated this analysis controlling for the presence of multiple anxiety disorders, no result gained significance.

Table 2.

Substance Use Disorders in Adolescents with BPD by the Presence or Absence of Conduct Disorder (n=88)*

| BPD-CD | BPD+CD | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N (%) with outcome | N | N (%) with outcome | HR | 95% CI | χ2 | p | |

| SUD | 50 | 10 (20) | 34 | 11 (32) | 1.46 | 0.62–3.43 | 0.74 | 0.39 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 48 | 6 (13) | 37 | 8 (22) | 1.24 | 0.43–3.58 | 0.16 | 0.69 |

| Alcohol Dependence | 47 | 1 (2) | 41 | 5 (12) | 3.23 | 0.37–28.08 | 1.13 | 0.29 |

| Drug Abuse | 50 | 7 (14) | 33 | 6 (18) | 1.12 | 0.38–3.33 | 0.04 | 0.84 |

| Drug Dependence | 47 | 2 (4) | 37 | 7 (19) | 3.45 | 0.71–16.83 | 2.34 | 0.13 |

| Cigarette Smoking | 52 | 9 (17) | 34 | 6 (18) | 0.94 | 0.33–2.63 | 0.02 | 0.89 |

CD preceded outcome for all subjects with both CD and outcome; Cox proportional hazards models controlling for subjects’ age

As an exploratory analysis, we also looked to see whether pre-existing SUD mediates the risk of CD among BPD youth using Cox proportional hazard models. When we conducted this analysis between BPD+SUD (23(24%)) and BPD-SUD (71(75%)) youth, we did not find any significant difference in risk of CD between the two groups.

Age of CD onset and SUD

We further assessed the influence of the age of onset of CD on the onset of SUD with Cox proportional hazards models. These models predict time of onset of SUD and cigarette smoking in subjects with BPD-CD compared to subject with early CD onset (before age 10) and late CD onset (onset at age 10 or older). All subjects with early CD onset reported CD before any SUD onset. For subjects with late CD onset, 20 subjects reported CD prior to cigarette smoking and substance abuse onsets, 23 subjects reported CD prior to an alcohol abuse onset, 27 reported CD prior to an alcohol dependence onset, and 24 reported CD prior to a substance dependence onset.

Since we found significant variance in mean age across groups (F2,88=11.93, p < 0.0001), we corrected all analyses for age: subjects with Late Onset CD were significantly older than subjects with Early Onset CD (F1,88=22.50, p<0.0001) and subjects with BPD-CD (F1,88=14.13, p < 0.001). When we compared the three groups with each SUD onset, we did not find any significant differences in the ages of SUD onset. We also did not find any differences in the ages of SUD onset between those with early CD onset or late CD onset.

Overall Association

Using logistic regression to control for age, SES, family history of BPD, and family history of SUD, we first examined the overall relationship between BPD, CD, and SUD among all subjects. As previously reported20, there were significant differences between BPD subjects with and without CD and controls in rates of overall SUD (χ2=20.52, p<0.001), alcohol abuse (χ2=11.45, p<0.005), drug abuse (χ2=11.84, p<0.005), drug dependence (χ2=6.26, p<0.05) and cigarette smoking (χ2=14.88, p<0.001). When we repeated this analysis controlling for the presence of multiple anxiety disorders, alcohol abuse was the only outcome to lose significance.

Rates of SUD were significantly lower in BPD subjects without CD (n=7(15%)) compared to BPD with CD (n=27(47%); χ2=5.91 p=0.009). Similar trends were seen for alcohol and drug use disorders20. When we compared BPD subjects without CD and controls, overall SUD and cigarette smoking remained significant (p<0.05).

Clinical Characteristics of SUD

We also evaluated the influence of CD on severity of SUD and smoking in individuals with SUD and smoking, using linear regression controlling for age. Comparing subjects with BPD+CD to those without CD, we found no significant difference in the duration of cigarette smoking or SUD. We found a significant effect of CD on the frequency of the non-nicotine simultaneous abuse or dependence of more than one drug or alcohol across all subjects: BPD+CD subjects were significantly more likely to manifest a combined alcohol plus drug use disorder (23 subjects or 40% of 58 cases with BPD+CD) compared to subjects with BPD-CD (3 subjects or 6% of 47 subjects; by logistic regression χ2=11.99, p< 0.001).

Subjects with BPD+CD (45.4 ± 5.8) had significantly lower current global assessment of functioning scores than subjects with BPD-CD (50.3±7; F1,102=16.39, p <0.001). We also found that subjects with BPD+CD (37.7 ± 5.1) had significantly lower lifetime GAF scores (40 ± 5.7; linear regression: F1,102=3.97, p=0.05).

Discussion

The results of these analyses of adolescents with BPD show that CD commonly onsets prior to SUD. Contrary to our hypothesis, CD that precedes SUD does not significantly increase the risk for a subsequent SUD or earlier-onset SUD. Compared to adolescents with BPD without CD, CD is associated overall with a more complicated SUD (combined drug plus alcohol use disorders) and poorer overall functioning.

These findings are reminiscent of our previous work in juvenile BPD and SUD. In three pediatric samples, we have reported that adolescents with BPD are at a 2–4 fold higher risk for SUD relative to prepubescent onset BPD18, 20, 38 independent of CD. In these studies, however, the sequential relationship of CD onset to SUD onset was not examined.

Our current data partially replicate previous studies that have shown an increased risk for SUD associated with CD in BPD 28–33. In some of these studies, CD plus other psychopathology incrementally increased the risk for SUD and/or resulted in earlier onset SUD. In the COBY study, for example, Goldstein et al. reported that among 12–17 year old BPD adolescents that CD was associated with a 5.6-fold increased likelihood of developing SUD 39. Carlson et al.13 reported that BPD young adults (< 30 years of age) with SUD had a significant overrepresentation of CD as youth and that the presence of comorbid CD, not BPD, that accounted for the increased risk for SUD. In our current data, overall BPD plus CD was associated with a more complicated SUD; however, controlling for CD, BPD was associated with SUD. Moreover, if one examined only those cases with CD prior to SUD, CD did not increase incrementally the risk for subsequent SUD over that observed with BPD. Differences in the findings may be accounted for by age of follow-up (adolescents vs. young adults), study design (prospective vs. retrospective), and definitions of CD (exclusion vs. inclusion of SUD in CD criteria) may account for the differences in findings.

Our data show some differences in the associations for drug compared to alcohol use disorders in our BPD sample. Despite alcohol being the most common substance misused in our sample of adolescents with BPD, subjects with CD plus BPD specifically, were more likely to have cigarette smoking and drug use disorders. It is of interest that similar findings have been reported recently40, in which conduct mediated drug but not alcohol use disorders in first degree relatives of ADHD youth. While our current finding may be due to relatively small sample sizes in specific analyses, further work needs to be completed to examine more carefully the role of CD in mediating specific classes of agents that are misused or abused.

Why CD is more is more likely to occur with drugs more so than alcohol remains unclear. It may be that drug use is considered more delinquent and given the nature of CD; these youth preferentially use cigarettes and drugs. Alternatively, given familial specificity in SUD41, 42, CD may be linked to specific forms of SUD such as cigarette or drug use disorders. It may also be related to the increased risk for cigarette use that precedes SUD that in turn may kindle specific subsequent drug use disorders37. Clinically, youth with BPD plus CD need to be carefully monitored for the onset of cigarette smoking; as well as SUD, in particular marijuana.

The reported association between BPD, CD, and SUD is not surprising considering that juvenile mania is frequently associated with prolonged and aggressive outbursts43, 44 that may predispose these youth to develop SUD45–47. Although these aberrant behaviors are consistent with the diagnosis of CD, they may be due to the behavioral disinhibition that characterizes BPD that may lead to SUD4, 21, 48. Considering that adolescence is a time of high risk for the development of SUD, we have speculated that BPD (and CD) through poor judgment, limited self control, and/or disinhibition49, may be particularly noxious for the development of SUD during adolescence-the time of heightened risk for SUD18, 20, 50. It may be that adolescents self medicate their irritable mood, aggressivity, and “affective storms” with substances of abuse or alcohol47, 51. It may also be that there is a synergistic familial/genetic or other biological predisposition to SUD in BPD (±CD) 48 such that a synergistic relationship exists placing youth simultaneously at risk for BPD, CD, or the combination. Our findings continue to support our previous work on the independence of BPD as a risk factor for adolescent-onset SUD 18–20 What remains to be further delineated, is the magnitude of the ultimate risk associated with CD, the interaction of CD with BPD, the role of additional psychosocial stressors, family functioning, and the mediating role of mood-related CD and treatment in SUD development as our sample fully pass through the full age of risk for SUD.

There are a number of methodological limitations in the current study. Data for the current study are derived from the baseline assessment and are hence, cross sectional in nature. Follow-up of this sample through the full age of risk for SUD is necessary. The sample size is limited, particularly in groups such as those with SUD and CD. SUD was determined by aggregating direct and indirect report via structured interview, as opposed to urine toxicology screens. However, we have found in separate samples that such interviews may provide a more sensitive method of detecting historical SUD that may be missed by urine testing36. Additionally, while differences in ages existed between groups such as those with early versus later onset CD, we utilized modeling to correct for these differences. Furthermore, we were unable to assess the magnitude of the ultimate risk associated with CD or the interaction of CD with BPD due to the lack of CD-BPD individuals. Given the racial and ethnic composition of our sample, it is unclear if these findings will generalize to other settings. Also our results may not generalize to BPD cases in the community.

Despite these limitations, the results of these analyses show that BPD in adolescence confers an elevated risk for SUD; and that CD is associated with a more complex presentation SUD in this group. However, early-onset CD does not appear to increase incrementally the risk for cigarette smoking or SUD over that beget by BPD alone. Clinicians need to be mindful of the association between CD and SUD in begetting SUD among BPD youth. Further study of this group as they pass fully through the age of risk is necessary.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH RO1 DA12945 (TW) and K24 DA016264 (TW)

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Timothy Wilens receives research support from, is a speaker for, or is on the advisory board of the following sources: Abbott, McNeil, Lilly, NIH (NIDA), Novartis, Merck, and Shire.

Dr. Joseph Biederman is currently receiving research support from the following sources: Alza, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Co., Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., McNeil, Merck, Organon, Otsuka, Shire, NIMH, and NICHD

Dr. Joseph Biederman is currently a consultant/advisory board member for the following pharmaceutical companies: Janssen, McNeil, Novartis, and Shire. Dr. Joseph Biederman is currently a speaker for the following speaker’s bureaus: Janssen, McNeil, Novartis, Shire, and UCB Pharma, Inc. In previous years, Dr. Joseph Biederman received research support, consultation fees, or speaker’s fees for/from the following additional sources: Abbott, AstraZeneca, Celltech, Cephalon, Eli Lilly and Co., Esai, Forest, Glaxo, Gliatech, NARSAD, NIDA, New River, Novartis, Noven, Neurosearch, Pfizer, Pharmacia, The Prechter Foundation, The Stanley Foundation, and Wyeth.

Dr. Markus Kreusi receives research support from or is consultant for the following sources: Select Health and Lilly.

Previous Presentation: 2008 Pediatric Bipolar Conference, Boston Massachusetts

References

- 1.Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Bipolar disorders in a community sample of older adolescents: prevalence, phenomenology, comorbidity, and course. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(4):454–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weller RA, Weller EB, Tucker SG, Fristad MA. Mania in prepubertal children: has it been underdiagnosed? J Affect Disord. 1986;11:151–154. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(86)90022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wozniak J, Biederman J, Kiely K, et al. Mania-like symptoms suggestive of childhood-onset bipolar disorder in clinically referred children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:867–876. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199507000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weller EB, Weller RA, Fristad MA. Bipolar disorder in children: Misdiagnosis, underdiagnosis, and future directions. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(6):709–714. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199506000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wozniak J, Biederman J, Kiely K, Ablon JS, Faraone S. Prepubertal mania revisited. Scientific Proceedings of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; San Antonio, TX. 1993. p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geller B, Craney JL, Bolhofner K, Nickelsburg MJ, Williams M, Zimerman B. Two-year prospective follow-up of children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(6):927–933. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birmaher B. Adolescent outcome in BPD. Bipolar Consortium; Boston, MA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geller B, Tillman R, Craney JL, Bolhofner K. Four-year prospective outcome and natural history of mania in children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004 May;61(5):459–467. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geller B, Tillman R, Bolhofner K, Zimerman B, Strauss NA, Kaufmann P. Controlled, blindly rated, direct-interview family study of a prepubertal and early-adolescent bipolar I disorder phenotype: morbid risk, age at onset, and comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Oct;63(10):1130–1138. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Axelson D, Birmaher B, Strober M, et al. Phenomenology of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Oct;63(10):1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, et al. Diagnostic characteristics of 93 cases of a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype by gender, puberty and comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2000;10(3):157–164. doi: 10.1089/10445460050167269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strober M, DeAntonio M, Schmidt-Lackner S, Freeman R, Lampert C, Diamond J. Early childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder predicts poorer response to acute lithium therapy in adolescent mania. J Affect Disord. :1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00213-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlson G, Bromet E, Jandorf L. Conduct disorder and mania: What does it mean in adults. Journal of Affective Disorders’. 1998;48:199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geller B, Sun K, Zimerman B, Luby J, Frazier J, Williams M. Complex and rapid-cycling in bipolar children and adolescents: A preliminary study. J Affect Disord. 1995;34(4):259–268. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00023-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birmaher B, Axelson D. Course and outcome of bipolar spectrum disorder in children and adolescents: a review of the existing literature. Dev Psychopathol. 2006 Fall;18(4):1023–1035. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rende R, Birmaher B, Axelson D, et al. Childhood-onset bipolar disorder: Evidence for increased familial loading of psychiatric illness. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007 Feb;46(2):197–204. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246069.85577.9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilens TE, Biederman J, Milberger S, et al. Is bipolar disorder a risk for cigarette smoking in ADHD youth? Am J Addict. 2000;9(3):187–195. doi: 10.1080/10550490050148017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilens TE, Biederman J, Millstein R, Wozniak J, Hahesy A, Spencer TJ. Risk for substance use disorders in youth with child- and adolescent-onset bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(6):680–685. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilens T, Biederman J, Kwon A, et al. Risk for substance use disorders in adolescents with bipolar disorder. Journal of the American Academy Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(11):1380–1386. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000140454.89323.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilens T, Biederman J, Adamson J, et al. Further Evidence of an Association between Adolescent Bipolar disorder with smoking and substance use disorders: A controlled study. Drug Alchol Depend. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.016. Accepted for Publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovacs M, Pollock M. Bipolar disorder and comorbid conduct disorder in childhood and adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(6):715–723. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199506000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faraone SV, Biederman J, Wozniak J, Mundy E, Mennin D, O’Donnell D. Is comorbidity with ADHD a marker for juvenile-onset mania? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(8):1046–1055. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199708000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geller B, Fox L, Clark K. Rate and predictors of prepubertal bipolarity during follow-up of 6-to 12-year-old depressed children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(4):461–468. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biederman J, Faraone SV, Chu MP, Wozniak J. Further evidence of a bidirectional overlap between juvenile mania and conduct disorder in children. J Am Acad Child Adoles Psychiatry. 1999;38(4):468–476. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199904000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Findling RL, Calabrese JR. Rapid-cycling bipolar disorder in children. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(9):1526–1527. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1526-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barzman DH, DelBello MP, Fleck DE, Lehmkuhl H, Strakowski SM. Rates, types, and psychosocial correlates of legal charges in adolescents with newly diagnosed bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007 Jun;9(4):339–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Endrass J, Vetter S, Gamma A, et al. Are behavioral problems in childhood and adolescence associated with bipolar disorder in early adulthood? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007 Jun;257(4):217–221. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0710-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robins LN. Deviant children grown up. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tarter RE, Edwards K. Psychological factors associated with the risk for alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1988;12:471–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brook J, Cohen P, Brook D. Longitudinal study of co-occuring psychiatric disorders and substance use. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37(3):322–330. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199803000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crowley TJ, Riggs PD. Adolescent substance use disorder with conduct disorder and comorbid conditions. NIDA Res Monogr. 1995;156:49–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitmore E, Mikulich S, Thompson L, Riggs P, Aarons G, Crowley T. Influences on adolescent substance dependence: conduct disorder, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and gender. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47:87–97. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Renouf AG, Kovacs M, Mukerji P. Relationship of depressive, conduct, and comorbid disorders and social functioning in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adoelscent Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):998–1004. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faraone SV, Adamson JJ, Wilens T, Monuteaux MC, Biederman J. Deriving phenotypes for molecular genetic studies of substance use disorders: A family approach. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(2–3):244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ambrosini PJ. Historical development and present status of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children (K-SADS) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):49–58. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gignac M, Wilens TE, Biederman J, Kwon A, Mick E, Swezey A. Assessing cannabis use in adolescents and young adults: what do urine screen and parental report tell you? J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005 Oct;15(5):742–750. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biederman J, Monuteaux M, Mick E, et al. Is cigarette smoking a gateway drug to subseqeunt alcohol and illicit drug use disorders? A controlled study of youths with and without ADHD. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Biederman J, Faraone S, Milberger S, et al. A prospective 4-year follow-up study of attention-deficit hyperactivity and related disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(5):437–446. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830050073012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldstein BI. Substance Use Disorders among Adolescents with Bipolar Spectrum Disorders. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Biederman J, Petty CR, Wilens TE, et al. Familial risk analyses of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 Jan;165(1):107–115. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07030419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsuang MT, Lyons MJ, Eisen SA, et al. Genetic influences on DSM-III-R drug abuse and dependence: A study of 3,372 twin pairs. Am J Med Genet. 1996;67(5):473–477. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960920)67:5<473::AID-AJMG6>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merikangas K, Stolar M, Stevens D, et al. Familial transmission of substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(11):973–979. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davis RE. Manic-depressive variant syndrome of childhood: A preliminary report. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136(5):702–706. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.5.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carlson GA. Bipolar affective disorders in childhood and adolescence. In: Cantwell DP, Carlson GA, editors. Affective Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence. New York: Spectrum Publications; 1983. pp. 61–83. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brook JS, Whiteman M, Cohen P, Shapiro J, Balka E. Longitudinally predicting late adolescent and young adult drug use: Childhood and adolescent precursors. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(9):1230–1238. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199509000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Donovan S, Nunes E. Treatment of comorbid affective and substance use disorders Therapeutic potential of anticonvulsants. American Journal of Addiction. 1998;7(3):210–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brady KT, Myrick H, McElroy S. The relationship between substance use disorders, impulse control disorders, and pathological aggression. Am J Addict. 1998;7:221–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Biederman J, Faraone SV, Wozniak J, Monuteaux MC. Parsing the association between bipolar, conduct, and substance use disorders: a familial risk analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(11):1037–1044. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00906-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Mezzich A, et al. Neurobehavioral disinhibition in childhood predicts early age at onset of substance use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003 Jun;160(6):1078–1085. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV, Spencer T, Wilens TE, Wozniak J. Pediatric Mania: A developmental subtype of bipolar disorder? Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(6):458–466. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00911-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1997;4:231–244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.