Abstract

Purpose

Evidence shows that aspects of personality are associated with participation in physical activity. We hypothesized that, among adolescents, behavioral activation (BAS) and behavioral inhibition (BIS) would be associated with physical fitness (cardiovascular fitness and percent body fat), enjoyment of exercise, tolerance of and persistence in high-intensity exercise, and affective response to an acute exercise bout.

Methods

One hundred forty-six healthy adolescents completed a cardiovascular fitness test, percent body fat assessment (dual energy x-ray absorptiometer), and two 30-minute cycle ergometer exercise tasks at a moderate and a hard intensity. Questionnaires evaluated BIS/BAS, enjoyment of exercise, and preference and tolerance for high-intensity activity. Affect in response to exercise was assessed using the Feeling Scale (FS) and the Activation Deactivation Adjective Check List (AD ACL).

Results

BIS was negatively correlated with cardiovascular fitness and tolerance for high-intensity exercise, and adolescents with high BIS scores reported more negative FS in response to exercise at both moderate and hard intensities. BAS was positively correlated with enjoyment of exercise, and adolescents with high BAS scores reported having more positive FS and higher Energetic Arousal on the AD ACL in response to moderate exercise. The association between BAS and affect was attenuated for the hard exercise task.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that both the drive to avoid punishing stimuli (BIS) and the drive to approach rewarding stimuli (BAS) are related to the affective response to exercise. The BIS may be more strongly associated with fitness-related exercise behavior among adolescents than the BAS, whereas the BAS may play a relatively greater role in terms of subjective exercise enjoyment.

Keywords: physically active, Behavioral Activation, Behavioral Inhibition, Affect

Introduction

Estimates based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), using measured heights and weights, indicate that roughly 16 percent of American children and adolescents ages 2 – 19 years are overweight (26), placing them at increased risk for Type 2 diabetes (21) and heart disease (34). Although there is debate as to the reasons for the rising pediatric obesity rates, evidence indicates that insufficient participation in regular physical activity plays a contributing role (20; 30). Epidemiologic data indicate that a troubling proportion of adolescents are not meeting the current health guidelines for physical activity (12; 33) and, despite a growing body of research in this area, little is understood about how to reverse this trend. Throughout adolescence, there is a precipitous decline in physical activity participation (9), and sedentary adolescents are at high risk for remaining sedentary into adulthood (1; 2).

The vast majority of research into why some adolescents remain physically active while others do not has been based on constructs derived from social cognitive models of health behavior, such as perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and self-efficacy. In recent years, another class of variables that has received a fair amount of attention has been dimensions of the physical environment, such as urban design. Far fewer studies have attempted to identify individual differences in personality that might contribute to adolescents’ likelihood of remaining active.

Personality refers to an enduring and consistent pattern of thoughts, feelings, and actions. A meta-analysis of research examining the association between personality and physical activity (28) found that the dimension of personality that was most consistently associated with physical activity was extraversion (i.e., the tendency to be sociable, assertive, seek excitement and experience positive affect). Carver, Sutton, and Scheier (7) posit that extraversion reflects the ‘approach’ component of a dual model of personality that bisects motivation and behavior into two types of action tendencies: approach and avoidance (or withdrawal).

Two neurobehavioral systems have been proposed to control the approach and withdrawal tendencies. These systems have been termed the behavioral activation system (BAS) and the behavioral inhibition system (BIS; 8; 17; 35). In essence, the BAS is responsible for guiding goal-directed or engagement behavior. Activity in this system causes the organism to begin (or increase) movement toward goals and to experience positive emotions. In contrast, the BIS is responsible for guiding behavioral responses to threats and novel stimuli. Activity in this system causes the organism to withdraw or inhibit ongoing behavior, and to experience negative emotions. According to this model, an individual with a highly activated BAS is relatively more sensitive to cues of impending reward and is predisposed to experience positive affect in response to an emotion-eliciting stimulus. In contrast, an individual with a highly activated BIS is relatively more sensitive to cues of impending punishment, and is predisposed to experience negative affect in response to an emotion-eliciting stimulus.

Carver and White (8) have developed and validated a paper-and-pencil measure (the BIS/BAS) that assesses individual differences in approach behaviors. The items on the BIS scale assess anxiety in response to a threatening situation, whereas the items on the BAS scale tap into the degree to which an individual tends to engage in approach-motivated activity toward a goal. Much of the research employing these scales has been designed to explore addictive and/or pathological behavior (17; 22) or to identify physiological markers of BIS/BAS activation (4; 6). Surprisingly, considering that the BIS and BAS are theorized to relate to individuals’ motivation to engage in goal-directed behavior, very little research has examined the utility of BIS/BAS for understanding health-related behaviors that require active engagement, such as participation in regular physical activity.

BIS/BAS and physical activity

A review of the relevant literature revealed one study that explicitly examined the association between BIS/BAS and physical activity-related constructs. In the study by Hall et al. (18), BAS scores were negatively and BIS scores were positively correlated with Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) during an exercise task. Interestingly, the correlations between BAS and RPE disappeared at higher exercise intensities, but those between BIS and RPE did not. These results suggest that individuals who scored higher on the BIS scale were attending to a greater degree to the negative sensations that accompany exercise, regardless of the exercise intensity. In contrast, individuals who scored higher on the BAS may have paid greater attention to the positive sensations that accompany low-intensity exercise, but this effect disappeared at higher levels of intensity.

The present study extends these findings by examining the hypotheses that 1) both the BIS and the BAS will be related to enjoyment of exercise, preference and tolerance for high-intensity exercise, and physiological indicators of physical activity participation (cardiovascular fitness and percent body fat); 2) adolescents with a highly activated BIS will report more negative affect in response to exercise regardless of the intensity of the exercise; and 3) adolescents with a highly activated BAS will report a more positive affective response to exercise at a moderate, but not at a hard level of intensity.

Understanding individual differences in affective response to physical activity is critical to the future success of interventions designed to promote adolescent physical activity (27). Personality types that may predispose individuals to respond to physical activity with a particular affective profile have, for the most part, not been explored among adolescents. Knowing which subgroups of adolescents are least likely to possess personalities that predispose them to enjoy being physically active would enable interventionists to design targeted programs for these at-risk individuals. The present study, then, examines the role of the BIS and BAS as correlates of physical fitness, exercise enjoyment, preference for and tolerance of high-intensity exercise, and affective response to exercise among adolescents.

Methods

Subjects

One hundred forty-six healthy adolescents (55% male; 66% Caucasian, 10% Asian, 16% Latino, 8% other; mean (SD) age = 14.79 (.46) years) were recruited from two public high schools in Southern California. In order to be eligible for the study, adolescents had to meet the following criteria: 1) no health problems that precluded participating in regular moderate to vigorous exercise; 2) enrolled in 10th grade during the study; 3) right-handed (determined using the Chapman Handedness Scale (10)); 4) no history of neurological disorders, stroke, or significant head trauma (i.e., head trauma associated with loss of consciousness for greater than 24 hours); 5) not clinically depressed (defined as ever having been diagnosed with clinical depression or scoring 20 or higher on the Beck Depression Inventory (3)). Inclusion criteria (3), (4), and (5) were incorporated because the study also involved collection of a resting electroencephalogram (data reported elsewhere).

Procedures

All study procedures were reviewed and approved by a University-based Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited using flyers distributed at the schools. An initial telephone screening was followed by an orientation session during which potential participants completed consent forms and screening questionnaires. All participants provided written assent to participate, and consent was also obtained from a parent or guardian. Adolescents who met the study inclusion criteria then visited a University-based General Clinical Research Center, where they completed a cardiovascular fitness test (see below for procedural details). Following the fitness test, each participant’s Ventilatory Threshold (VT) was determined offline. The VT was determined by visually inspecting the ventilatory equivalents for oxygen and carbon dioxide, and identifying the point at which there was a systematic increase in ventilatory equivalent for oxygen without a corresponding increase in ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide. The work rate at the VT was used to calculate the target work rate for the moderate and hard exercise tasks as described below.

A second clinic visit was scheduled within approximately one week of the first. During the second visit, participants completed a computerized questionnaire that assessed BIS/BAS, enjoyment of exercise, and preference and tolerance for high-intensity exercise, and engaged in a 30-minute exercise task on a cycle ergometer. Prior to commencing the exercise task, participants completed two affect assessments (one single-item measure—Feeling Scale; and one multiple item measure—Activation Deactivation Adjective Check List [AD ACL]). Throughout the exercise task and after a 10-minute recovery period, participants were asked every 10 minutes to indicate their affect on the single-item measure. Upon conclusion of the task, at 30 minutes, and again after 10 minutes of resting recovery, participants completed the multiple-item measure of affect. Thus, the Feeling Scale measure was collected at 0, 10, 20, 30 and 40 minutes, whereas the AD ACL was collected at 0, 30, and 40 minutes.

The exercise task was repeated at a third visit to the clinic, with visits two and three randomly determined to be at either a moderate intensity level of exertion (target work rate equivalent to 80% of the watts at which the participant reached VT) or a hard intensity level of exertion (target work rate equivalent to the average of the individual’s work rates at VT and at VO2 peak). Exercise technicians were instructed to be alert for signs of fatigue on the part of participants and to reduce the target work rate in increments of 5–10 watts after the first 10 minutes of exercising, as needed, to ensure that the participant would be able to complete the 30-minute task. Fatigue was defined as the participant being unable to maintain a cadence of 60 revolutions-per-minute for 60 seconds. Participants were not informed as to the intensity level at which they would be exercising. Participants received monetary compensation ($25) following each clinic visit.

Measures

Cardiovascular fitness

Each participant performed a ramp-type progressive cycle-ergometer exercise test (35). Breath-to-breath measurement of gas exchange (ventilation, oxygen uptake, and carbon dioxide output) was viewed online and subsequently analyzed using a Sensor Medics® metabolic system (Yorba Linda, CA). Data from the ramp test was used to determine the peak VO2 (VO2peak) and the VT for each participant.

Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA)

Percent body fat was determined by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) using a Hologic QDR 4500 densitometer (Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA). Participants were scanned in light clothing while lying supine. DEXA scans were performed and analyzed using pediatric software. On the day of each test, the DEXA instrument was calibrated using procedures provided by the manufacturer.

BIS/BAS

Approach (BAS) and withdrawal (BIS) motivations were measured with the 20-item BIS/BAS Scale (8), which has been shown to be valid and reliable among adults, has demonstrated convergent and discriminant validity in relation to other measures of personality among college students (8) and retains its measurement and construct validity when used with adolescents (11). The 7-item BIS subscale assesses apprehension over the possibility of negative events and reaction to these events when they transpire. The 13 BAS items map onto three subscales (Drive, Reward-responsiveness, and Fun-seeking). A 5-point response scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) was used for items such as “If I think something unpleasant is going to happen, I usually get pretty worked up” (BIS) and “when I get something I want, I feel excited and energized” (BAS). In this sample, the BIS and BAS scales had acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .62 to .77).

Preference for and Tolerance of Exercise Intensity (PRETIE-Q)

The PRETIE-Q is a 16-item tool designed to assess participants’ preference for and tolerance of high-intensity exercise. Developed by Ekkekakis, Hall, and Petruzzello (13) and validated by Ekekkakis et al. (16), there are eight items on each subscale (i.e., the Preference and Tolerance subscales), each of which is scored on a five-point response scale ranging from 1 (I totally disagree) to 5 (I totally agree). Responses were provided to items such as “while exercising, I try to keep going even after I feel exhausted” (Tolerance) and “Exercising at a low intensity does not appeal to me at all” (Preference). In this study, the Preference and Tolerance subscales had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas = .85 and .82, respectively).

Enjoyment of Exercise

Exercise enjoyment was assessed using the Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES; 23), as modified and validated by Motl et al (25). The PACES contains 16 items rated on a Likert scale from 1 (disagree a lot) to 5 (agree a lot). An example of an item from this scale is: “When I am active I find it pleasurable.” In this study, the PACES had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .88).

Affect

Two scales were used to gauge affect in conjunction with the exercise tasks: the Feeling Scale (FS) and the Activation Deactivation Adjective Check List (AD ACL). These scales were selected because they have been used in similar studies of the affective response to exercise and are sensitive to the changes in affect that accompany exercise (14; 24; 29). The FS (19) is a single-item 11-point bipolar measure of pleasure-displeasure. The scale ranges from −5 (very bad) to +5 (very good). A modified Ad ACL also was used to gauge affect before and after each exercise task (31; 32). The AD ACL is a 20-item self-report measure that assesses two arousal dimensions: energetic arousal (EA) and tense arousal (TA). Response options range from 1 (definitely feel) to 4 (definitely do not feel). The reliability and construct validity of the AD ACL are well established (31). In order to update the instrument for our contemporary adolescent sample, we replaced two adjectives on the Tension scale (i.e., we replaced “clutched-up” with “nervous” and “intense” with “stressed”). Items within each subscale were averaged to provide a summary score for each subscale. In this study, the EA and TA subscales of the AD ACL had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas = .72 and .76).

Ratings of perceived exertion (RPE)

Borg’s RPE scale (5) was employed as a manipulation check during the exercise tasks. This scale ranges from 6 (no exertion at all) to 20 (maximal exertion). Participants were asked to provide a rating on the RPE scale every three minutes throughout the exercise tasks.

Data Analysis

In order to demonstrate that the two exercise tasks successfully produced significantly different levels of exertion, repeated measures ANOVAs examined the impact of the exercise on the periodic assessments of heart rate and RPE. Zero-order correlations were employed to assess the relationship of the BIS and BAS scales to variables assessing exercise enjoyment, Preference, and Tolerance. The p values presented for zero-order correlations with BIS and BAS have been corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferonni method. Only those BAS scales that were significantly correlated with enjoyment of exercise were included in the subsequent repeated measures analyses.

The relationships of BIS and BAS to the affective response to exercise were assessed using three separate intensity by time repeated measures analyses. In each analysis, a measure of affect (FS, EA, TA) was examined across all of the available time points after controlling for cardiovascular fitness. The BIS and BAS variables were transformed into dichotomous variables representing high and low scorers, and these dichotomous variables were entered into the repeated measures analyses as between-subjects factors. For the BIS, a median split yielded two groups of low- (n = 73) and high- (n = 68) scoring participants, respectively. For the BAS (reward), the median split yielded two groups of low- (n = 63) and high- (n = 83) scoring participants, respectively. For FS, there were five time points (baseline, minutes 10, 20, 30, 40), and for the AD ACL scales there were three time points (baseline, minutes 30, 40). Initially, gender was included as a covariate in all analyses, but as there were no main or interactive effects for gender, it was dropped from the analyses.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations for BIS, BAS, VO2peak, Percent Body Fat, Enjoyment, Preference, and Tolerance. Boys and girls were significantly different on several of the variables; boys had lower BIS and Percent Body Fat, and higher Preference, Tolerance, and VO2peak.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics; Mean (SD).

| Boys (n = 81) |

Girls (n = 64) |

Full Sample (n = 146) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| BIS* | 3.27 (.62) | 3.68 (.60) | 3.45 (.64) |

| BAS(drive) | 3.55 (.77) | 3.41 (.79) | 3.48 (.78) |

| BAS(reward) | 4.35 (.41) | 4.37 (.48) | 4.36 (.43) |

| BAS(fun) | 3.87 (.71) | 3.90 (.70) | 3.89 (.70) |

| BAS (total) | 3.92 (.50) | 3.89 (.50) | 3.91 (.50) |

| Enjoyment | 4.59 (.41) | 4.53 (.45) | 4.56 (.43) |

| Preference* | 3.36 (.80) | 2.97 (.70) | 3.20 (.83) |

| Tolerance* | 3.46 (.70) | 3.01 (.60) | 3.27 (.73) |

| VO2peak* l/min | 2.80 (.53) | 1.99 (.40) | 2.45 (.62) |

| VO2peak * ml/min/kg | 44.02 (7.50) | 33.47 (6.41) | 39.36 (8.76) |

| VT (% of VO2peak) | 43 (10) | 42 (9) | 42 (10) |

| Percent body fat** | 17.92 (7.33) | 30.12 (5.90) | 23.38 (9.09) |

Significant difference between genders (*p < .01; p < .001)

Note: VO2peak = peak oxygen uptake; Enjoyment = enjoyment of exercise; Preference = preference for high-intensity exercise; Tolerance = tolerance of high-intensity exercise; BIS = Behavioral Inhibition System; BAS = Behavioral Activation System. VT = Ventilatory threshold expressed as percent of VO2peak.

Table 2 provides the correlations between the variables related to physical activity and fitness. Higher VO2peak was associated with lower percent body fat and with higher Preference and Tolerance. The measures of Enjoyment, Preference, and Tolerance were all positively correlated with one another.

Table 2.

Correlations of physical activity and related variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. VO2peak l/min | -- | |||

| 2. % body fat | −.45** | -- | ||

| 3. Enjoyment | .08 | −.13 | -- | |

| 4. Preference | .36** | −.34** | .22* | -- |

| 5. Tolerance | .35** | -.28** | .28* | .54** |

*p < .01

p<.001

Note: VO2peak = peak oxygen uptake; Enjoyment = enjoyment of exercise; Preference = preference for high-intensity exercise; Tolerance = tolerance of high-intensity exercise

Exercise Task Work Rate

During the moderate exercise task, 96% of the study participants were able to maintain the target work rate throughout the 30-minute exercise task. Five participants exhibited signs of fatigue during the task, resulting in an average reduction in work rate of 28 watts (SD = 17) per participant for these five individuals (range = 10 – 55 watts). During the hard exercise task, 85% of study participants exhibited signs of fatigue prior to the end of the 30-minute task, resulting in a mean reduction in the target work rate of 33 watts (SD = 16) per participant for these individuals (range = 5 – 80 watts).

Manipulation Checks

Heart Rate

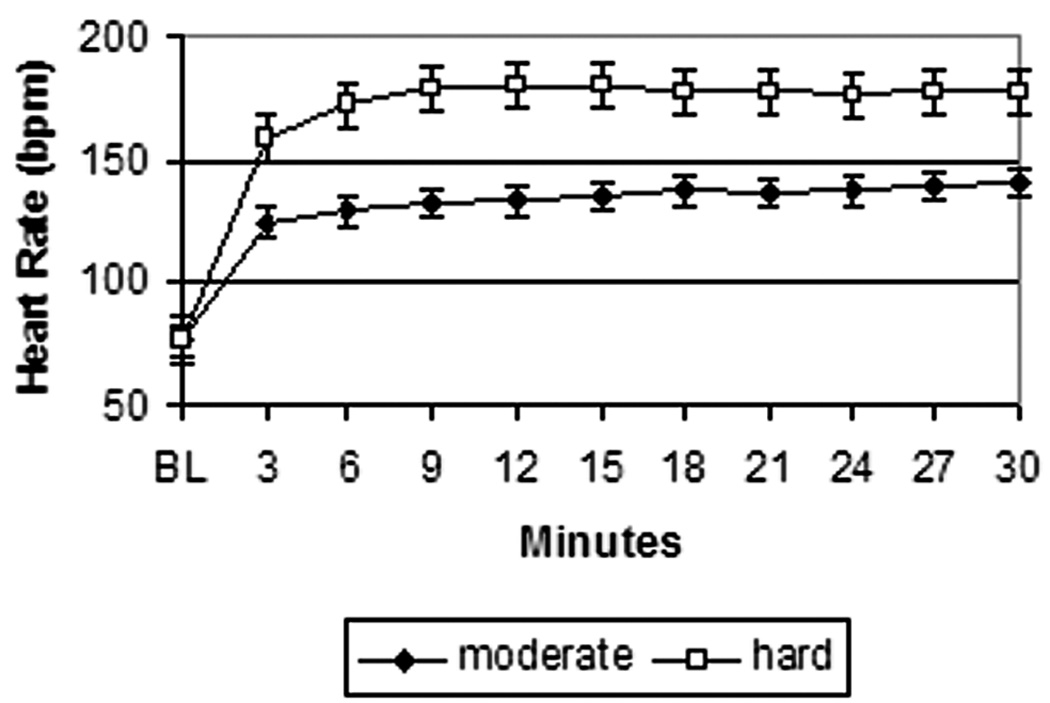

A 2 (exercise intensity) by 11 (time points: baseline, minutes 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, 30) repeated measures ANOVA on the heart rate data showed a significant main effect of exercise intensity [F (1, 106) = 536.37, p < .001], time [F(10, 97) = 320.37, p < .001], and the intensity by time interaction [F(10, 97) = 47.67, p < .001]. Figure 1 illustrates the pattern. During the moderate task, average heart rate increased from 76.40 beats per minute (SD = 13.99) during the warm-up to 137.00 bpm (SD = 18.98) at 18 minutes, and then remained fairly stable throughout the rest of the 30 minutes. Average heart rate during the hard exercise task increased from 76.60 bpm (SD = 15.65) during the warm-up to 179.00 bpm (SD = 14.04) at 9 minutes, and then remained stable for the rest of the task.

Figure 1.

Heart Rate during Exercise Tasks

Ratings of Perceived Exertion

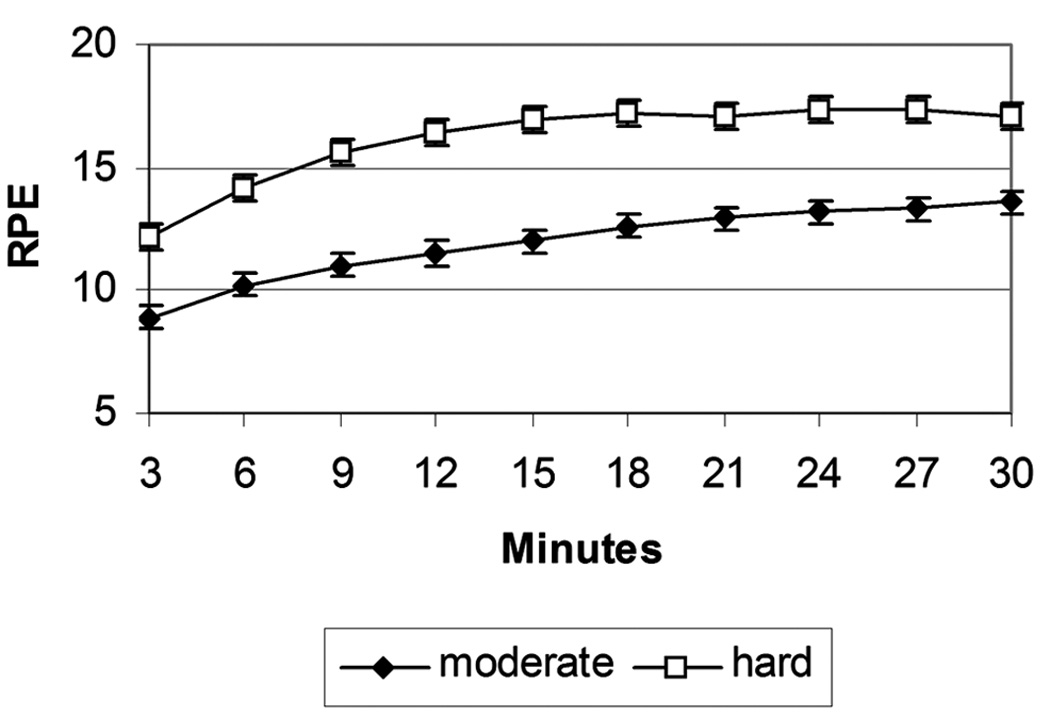

A 2 (exercise intensity) by 10 (time points: minutes 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, 30) repeated measures ANOVA on the RPE data showed a significant main effect of exercise intensity [F (1, 125) = 449.47, p < .00], time [F(9, 117) = 76.74, p < .001], and the intensity by time interaction [F(9, 117) = 11.63, p < .001]. Figure 2 shows that the average RPE during the moderate exercise task increased from 8.90 (very light; SD = 2.05) at 3 minutes to 13.60 (somewhat hard; SD = 3.28) at 30 minutes, with most of the increase occurring during the first 15 minutes of the task. Similarly, during the hard exercise task, the average RPE increased from 12.20 (somewhat hard; SD = 2.13) at 3 minutes to 17.00 (very hard; SD = 2.07) at 15 minutes, and then remained fairly constant throughout the rest of the task.

Figure 2.

Ratings of Perceived Exertion during Exercise Tasks

Associations of BIS/BAS with Physical Fitness and Related Constructs

There was a significant negative correlation between the BIS and VO2peak (r = −.26, p < .05) and between the BIS and Tolerance (r = −.27, p < .05). Adolescents who scored higher on the BIS scale had lower VO2peak and Tolerance. The BAS(reward) subscale was positively related to Enjoyment (r = .44, p < .05). None of the other BAS subscales was significantly associated with any of the fitness or exercise-related variables. The BIS scale was unrelated to any of the BAS scales.

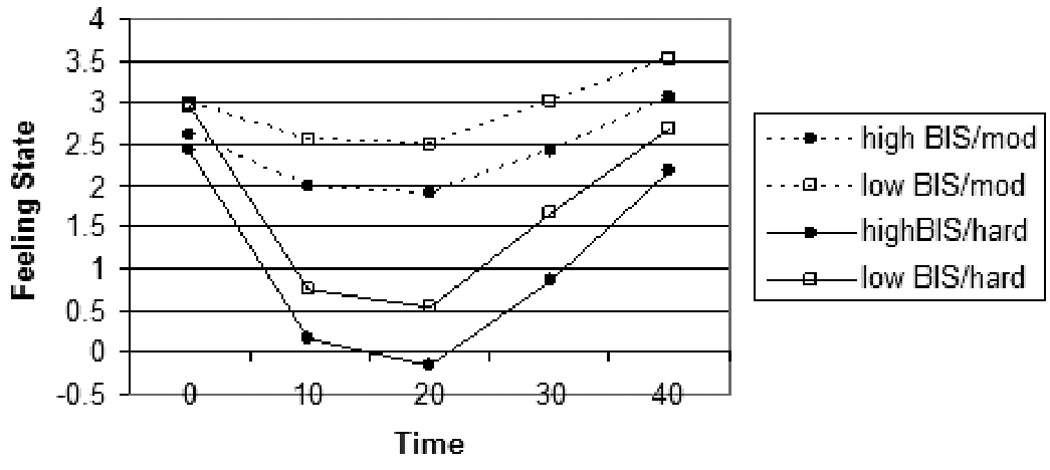

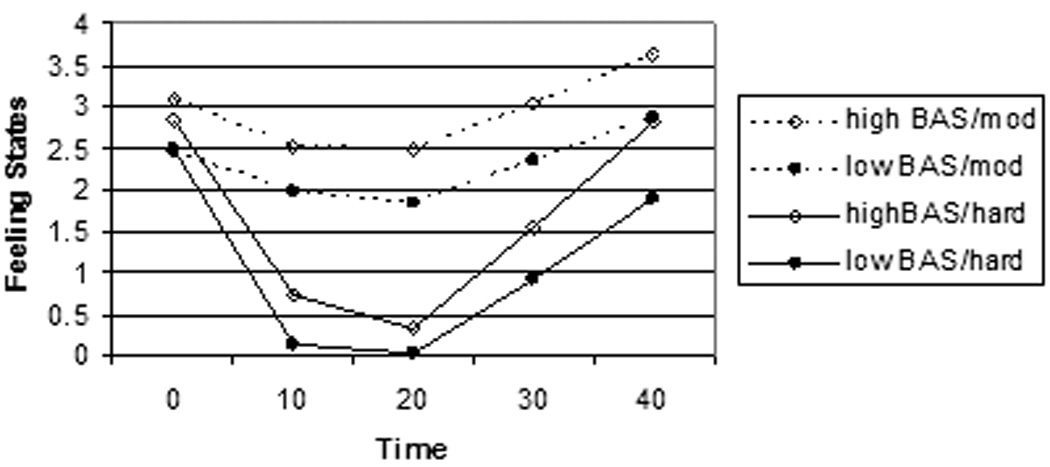

Associations of BIS/BAS with Affective Response to Exercise

Because only the BAS(reward) subscale had a significant correlation with Enjoyment, this scale was used in the repeated measures analysis. The 2 (exercise intensity) by 5 (time points: baseline, minutes 10, 20, 30, 40) by 2 (BAS[reward]: high and low) by 2 (BIS: high and low) repeated measures ANOVA on the ratings of FS showed a main effect of intensity [F(1, 137) = 19.76, p < .001], a main effect of time [F(4, 134) = 6.63, p < .001], an interaction between time and intensity [F(4, 133) = 3.00, p < .05], a main effect of the BIS (F = 11.05, p < .01), and a main effect of the reward subscale of the BAS (F = 9.02, p < .01). Post-hoc t-tests revealed that, compared to adolescents who scored below the median on the BIS, adolescents who scored above the median on the BIS reported a lower FS at baseline (t = 2.10, p< .05), 10 minutes (t = 2.29, p < .05), 20 minutes (t = 2.11, p < .05), 30 minutes (t = 2.20, p < .05), and 40 minutes (marginally; t = 1.95, p =.05), regardless of the exercise intensity. Figure 3 shows the consistently lower BIS ratings across time at both exercise intensities; all t-tests comparing FS across levels of the BIS within each intensity were statistically significant. Similarly, compared to adolescents who scored below the median on the BAS(reward), adolescents who scored above the median on the BAS(reward) reported a higher FS at baseline (t = 2.21, p< .05), 10 minutes (t = 2.11, p < .05), 30 minutes (t = 2.07, p < .05), and 40 minutes (t = 3.44, p < .01), regardless of the exercise intensity. Figure 4 shows that the difference between FS ratings appears to be attenuated during the hard task; all t-tests comparing FS across levels of the BAS(reward) within each intensity were statistically significant at the p < .05 level except those for the hard intensity task at baseline and 20 minutes (t-tests at 10 and 30 minutes during the hard task were marginally significant, p’s < .10).

Figure 3.

FS by levels of BIS

Figure 4.

FS by level of BAS (reward)

The 2 (exercise intensity) by 3 (time points: baseline, minutes 30, 40)) by 2 (BAS[reward]: high and low) by 2 (BIS: high and low) repeated measures ANOVA on the ratings of Energetic Arousal (EA) showed a main effect of intensity [F(1, 136) = 13.41, p < .001], a significant interaction between VO2peak and intensity [F(1, 136) = 4.64, p < .05], a main effect of the reward subscale of the BAS(F = 13.51, p < .001), and a three-way interaction between BAS(reward), intensity, and time [F(2, 135) = 3.19, p < .05]. Post-hoc t-tests indicated that high BAS(reward) scorers reported feeling significantly more energy than low BAS(reward) scorers at the baseline (t = 2.50, p < .01), 30 minute (t = 2.76, p < .01), and 40 minute (t = 3.83, p < .001) time points for the moderate exercise task. In contrast, high BAS(reward) scorers reported significantly more energy than low BAS(reward) scorers at baseline (t = 3.27, p < .01), but not at 30 minutes (t = 1.58, p = .11), or 40 minutes (t = 1.72, p = .08) for the hard exercise task.

The 2 (exercise intensity) by 3 (time points: baseline, minutes 30, 40)) by 2 (BAS[reward]: high and low) by 2 (BIS: high and low) repeated measures ANOVA on the ratings of Tense Arousal showed no main or interactive effects of time, intensity, BIS or BAS(reward) on ratings of TA. Similarly, the 2 (exercise intensity) by 10 (time points: baseline, minutes 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, 30)) by 2 (BAS[reward]: high and low) by 2 (BIS: high and low) repeated measures ANOVA on Ratings of Perceived Exertion (RPE) showed no main or interactive effects of time, intensity, BIS or BAS(reward) on ratings of RPE.

Discussion

The results of this study provide support for the hypotheses, though in a more nuanced fashion than anticipated. The hypothesis that both the BIS and the BAS would be correlated with physiological indicators of physical activity as well as exercise enjoyment and preference and tolerance for high-intensity exercise was partially confirmed. Only the BIS was correlated (negatively) with VO2peak and tolerance for high-intensity exercise, whereas only the BAS(reward) was correlated (positively) with exercise enjoyment. The hypothesis that the BIS would be associated with a more negative affective response to exercise, regardless of intensity, was supported by the results of the analyses using FS, but not by the analyses using the AD ACL scales. Finally, the hypothesis that BAS would be related to a more positive affective response to exercise during the moderate task only was confirmed. High BAS(reward) scorers did report more positive affect in response to the exercise tasks, and the association was attenuated during the hard task, especially using the Energetic Arousal scale as the measure of affect.

The items on the BIS scale are designed to assess sensitivity to cues of punishment, and the results of this study suggest that adolescents with greater sensitivity to cues of impending punishment are likely to take less pleasure in exercising, to tolerate high-intensity exercise less well, and to have lower cardiovascular fitness as compared to adolescents with a lower sensitivity to cues of punishment. This finding suggests that high-BIS adolescents are at elevated risk for becoming and remaining sedentary, and may require special attention if they are to maintain adequate levels of physical activity for optimal fitness. The fact that the difference in affective responding to an exercise bout persisted even during the moderate-intensity exercise session is of particular concern, as it suggests that high-BIS adolescents will find physical activity aversive even at the lower intensities usually assumed to be easily tolerated.

The items on the BAS(reward) scale are designed to assess positive responses to the anticipation of reward, and the results of this study indicate that adolescents with a greater sensitivity to cues of impending reward are more likely to report enjoying exercise and are also more likely to experience pleasure during exercise. It appears that at a hard level of exercise intensity this predisposition to experience positive affect with exercise may be obscured by the negative physiological cues that tend to accompany hard exercise (e.g., shortness of breath, perspiration, muscle strain, increased heart rate, etc…). Nevertheless, the BAS(reward) does seem to have a pervasive positive effect on the subjective experience of exercise, as adolescents with high BAS(reward) scores reported more positive affect even in anticipation of the exercise task (at baseline) and after the cessation of the hard exercise task. Moreover, higher BAS(reward) scores were positively correlated with self-reported enjoyment of exercise. These findings suggest that high-BAS(reward) adolescents may be well-positioned to maintain participation in physical activity.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the contribution of BIS/BAS to individual differences in affective response to exercise. The results suggest that both BAS and BIS have independent effects on the subjective experience of exercising. They also demonstrate that the effect of exercise is not uniform across individuals; deviations in personality characteristics may increase or decrease the likelihood that a person will experience a positive affective response to exercise. Thus, many of the studies that have examined mean differences in affective response to physical activity may have been hampered by a failure to take into account individual differences in affective responses.

Unlike the study by Hall, Ekkekakis, and Petruzzello (18), we did not find a relationship between BIS and BAS on the one hand and RPE on the other. The explanation for this divergence may reside in the nature of the samples employed in the two studies. We studied adolescents with an average age of 14, whereas Hall et al. recruited college students with an average age of 21. Adolescents at the younger age may still be undergoing physical changes associated with the pubertal growth spurt, and may therefore be less accustomed to the physiological sensations that accompany a given level of exertion. In contrast, young adults may have a greater reservoir of experience in terms of interpreting the sensations that accompany exercise, and may therefore be more reliable in their perceptions of exertion. In other words, one might expect greater random variability in responses among adolescents, thus introducing statistical “noise” into the data, and making any correlation more difficult to discern. Another difference between the two samples is that the adolescents in our study were noticeably less fit than the adults in the Hall et al. (18) study, as determined by reported levels of cardiovascular fitness. It may be that one would be more likely to find a relationship between BIS/BAS and RPE among individuals who are relatively fit. It is also worth noting that the absence of an association between BIS and RPE in our study is yet another argument that perceptions of exertion and affect are distinct constructs and, if one wants to comprehend adolescents’ exercise experiences, the inclusion of affect seems necessary.

The finding that BIS was related to cardiovascular fitness, whereas BAS was not, is worthy of some discussion. It is relevant to note that BIS and BAS are often described as independent systems (7), with all combinations of low and high BIS/BAS being possible. Thus, an individual who scores high on the BIS scale may score either high or low on the BAS scale; they are not inversely related. Our findings suggest that the strength of the BIS has greater implications for fitness-related behavior. That is, although high-BAS(reward) adolescents reported greater enjoyment of exercise, that enjoyment did not appear to translate into higher fitness levels. These findings suggest that a promising strategy for promoting physical activity among adolescents would be to develop targeted, innovative strategies designed to encourage high-BIS adolescents to learn to enjoy exercise, perhaps by pairing physical activity with other preferred activities, such as active video games or social interaction. Future research should strive to test novel interventions that may be successful in motivating high-BIS adolescents to maintain physical activity participation.

The inclusion of two measures of affect in this study provides an opportunity to parse this rather omnibus variable into its components. According to the circumplex model of affect (15), there are two dimensions along which affect can vary: valence (pleasure-displeasure) and activation (low-high). The Feeling Scale item, which asks the respondent to rate feelings on a single dimension from “bad” to “good”, is an example of a tool that assesses affective valence without regard to activation. The two scales of the AD ACL employed in this study are designed to tap into the two quadrants of the circumplex model of affect that correspond to activated pleasure (Energetic Arousal) and activated displeasure (Tense Arousal). These are the two quadrants that are typically assessed with regard to the affective response to exercise, since physical activity is expected to increase activation (14; 31).

Using the Feeling Scale item, we found that BIS was related to the affective response to exercise, yet this association was absent with the subscales of the AD ACL (Energetic Arousal and Tense Arousal). Our results suggest that the BIS is related to the pleasure/displeasure dimension of affect during an exercise bout, but not to the compound measures of affect that also incorporate the activation dimension. We speculate that, as the pleasure/displeasure dimension of affect is orthogonal to the activation/deactivation dimension, combining the two into a single assessment may introduce non-systematic variability and therefore obscure the association between the BIS and affective valence.

Unlike the pattern of findings with respect to the BIS, the association between BAS(reward) and affective response to exercise emerged when either the FS or the EA was employed to gauge affect, and did not emerge with respect to Tense Arousal. In order to understand this discrepancy, it is helpful to identify the specific adjectives that are included in the EA and TA scales. Energetic Arousal is assessed with the following adjectives: active, energetic, vigorous, lively, and full-of-pep. Tense Arousal is assessed with the following adjectives: jittery, stressed, fearful, anxious, and tense. As noted earlier, the BAS(reward) reflects sensitivity to cues of reward, so it makes intuitive sense that it would be related both to a measure of affective valence and to a measure of activated positive affect (energy) but not to activated negative affect (tension). In other words, the positivistic bias that may be introduced into adolescents’ perception when the BAS(reward) is highly activated might be expected to yield differences in a measure of activation that is on the “pleasure” end of the valence continuum but not in a measure of activation that is on the “displeasure” end of the valence continuum.1

This study is limited by its cross-sectional design. The associations that emerged in this analysis are correlations, and the direction of the associations cannot be determined from the present data. In other words, it could be that individuals who experience a more positive emotional response to exercise also engage in greater amounts of physical activity, and that this increased activity somehow stimulates the personality traits that are assessed by the BIS/BAS instrument. In order to disentangle these variables, it would be necessary to conduct a longitudinal study, in which BIS/BAS scores at one point in time are used to predict behavior change at a later point in time. Another limitation of this study is the reliance on self-report measures that have not been validated for use with adolescents. The Feeling Scale, Activation Deactivation Adjective Check List, and the BIS/BAS scales have not undergone rigorous validation analysis with adolescent samples, although a recent study with adolescents (29) employed the FS during acute exercise and reported similar patterns of responding as were found in the present study. All of these instruments have, however, been validated among adults, have excellent face validity, and demonstrated good internal consistency in this study. Still, it must be noted that we cannot assume that they are indeed measuring what we have set forth to measure. Finally, it should be noted that the effect sizes of the associations were generally small, in the range of 5% of the variance in affect explained. Clearly, there are other factors contributing to individual variability in affect during exercise. Future research should attempt to identify these additional factors, which may include cognitive variables (e.g., beliefs about the emotional benefits of exercise), social variables (e.g., concerns about social presentation in an exercise setting), and physiological variables (e.g., individual differences in neurophysiology).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Lisa Bouchard for her contributions to completing the study, and two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant HD-37746, and the UCI Satellite GCRC (MO1 RR00827). The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM.

Footnotes

The difference in findings cannot be explained by the different timing of the affect assessments; the pattern of associations between BAS and affect were the same when the FS was evaluated at only the same three time points for which AD ACL data were available.

References

- 1.Alfano CM, Klesges RC, Murray DM, et al. History of sport participation in relation to obesity and related health behaviors in women. Prev Med. 2002;34(1):82–89. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azevedo MR, Araujo CL, Cozzensa da Silva M, et al. Tracking of physical activity from adolescence to adulthood: a population-based study. Rev Saude Publica. 2007;41(1):69–75. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102007000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. Beck Depression Inventory-II. 1996:38. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blair C, Peters R, Granger D. Physiological and neuropsychological correlates of approach/withdrawal tendencies in preschool: further examination of the behavioral inhibition system/behavioral activation system scales for young children. Dev Psychobiol. 2004;45(3):113–124. doi: 10.1002/dev.20022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borg G. Ratings of perceived exertion and heart rates during short-term cycle exercise and their use in a new cycling strength test. Int J Sports Med. 1982;3(3):153–158. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1026080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenner SL, Beauchaine TP, Sylvers PD. A comparison of psychophysiological and self-report measures of BAS and BIS activation. Psychophys. 2005;42(1):108–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carver CS, Sutton S, Scheier M. Action, emotion, and personality: Emerging conceptual integration. Pers Soc Psych Bull. 2000;26:741–751. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: the BIS/BAS scales. J Pers Soc Psych. 1994;67:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caspersen CJ, Pereira MA, Curran KM. Changes in physical activity patterns in the United States, by sex and cross-sectional age. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9):1601–1609. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapman L, Chapman J. The measurement of handedness. Brain Lang. 1987;6:175–183. doi: 10.1016/0278-2626(87)90118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper A, Gomez R, Aucote H. The Behavioral Inhibition System and Behavioral Approach System (BIS/BAS) Scales: Measurement and structural invariance across adults and adolescents. Pers Indiv Diff. 2007;43:295–305. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance--United States, 2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2006;55(5):1–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ekkekakis P, Hall EE, Petruzzello SJ. Practical markers of the transition from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism during exercise: rationale and a case for affect-based exercise prescription. Prev Med. 2004;38(2):149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekkekakis P, Hall EE, Petruzzello SJ. The relationship between exercise intensity and affective responses demystified: to crack the 40-year-old nut, replace the 40-year-old nutcracker! Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(2):136–149. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9025-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ekkekakis P, Petruzzello SJ. Analysis of the affect measurement conundrum in exercise psychology; a conceptual case for the affect circumplex. Psych Sports Exerc. 2002;3:35–63. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekkekakis P, Thome J, Petruzzello SJ, et al. The Preference for and Tolerance of the Intensity of Exercise Questionnaire: a psychometric evaluation among college women. J Sports Sci. 2008;26(5):499–510. doi: 10.1080/02640410701624523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franken IH, Muris P, Georgieva I. Gray's model of personality and addiction. Addict Behav. 2006;31(3):399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall EE, Ekkekakis P, Petruzzello SJ. Is the relationship of RPE to psychological factors intensity-dependent? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(8):1365–1373. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000174897.25739.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardy C, Rejeski W. Not what, but how one feels: the measurement of affect during exercise. J Sport Exerc Psych. 1989;11:304–317. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hills A, King N, Armstrong T. The contribution of physical activity and sedentary behaviors to the growth and development of children and adolescents: implications for overweight and obesity. Sports Med. 2007;37(6):533–545. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu G, Lakka T, Kilpelainen T, et al. Epidemiological studies of exercise in diabetes prevention. Appl Physiol, Nut Metab. 2007;32(3):583–595. doi: 10.1139/H07-030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kasch KL, Rottenberg J, Arnow BA, et al. Behavioral activation and inhibition systems and the severity and course of depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(4):589–597. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kendzierski D, DeCarlo K. Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale: two validation studies. J Sport Exerc Psych. 1991;13(1):50–64. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lochbaum MR. Viability of resting electroencephalograph asymmetry as a predictor of exercise-induced affect: A lack of consistent support. J Sport Beh. 2006;29(4):315–334. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Motl R, Dishman R, Saunders R, et al. Measuring enjoyment of physical activity in adolescent girls. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(2):11–117. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Center for Health Statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, editor. Vol. DHHS Publication number 2004-1232, Series Health, United States. U.S.D.H.H.S.; 2004. Health, United States, 2004; p. 255. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rhodes R. The built-in environment: The role of personality and physical activity. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2006;34(2):83–88. doi: 10.1249/00003677-200604000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhodes R, Smith N. Personality correlates of physical activity: a review and met-analysis. Brit J Sports Med. 2006;40:958–965. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.028860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheppard K, Parfitt G. Acute affective responses to prescribed and self-selected exercise intensities in young adolescent boys and girls. Ped Exerc Sci. 2008;20:129–141. doi: 10.1123/pes.20.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swinburn B, Caterson I, Seidell J, et al. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of excess weight gain and obesity. Public Health Nutri. 2004;7(1A):123–146. doi: 10.1079/phn2003585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thayer RE. Activation-deactivation checklist: Current overview and structural analysis. Psych Rep. 1986;58:607–614. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thayer RE. The biopsychology of mood and arousal. New York: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Troiano R, Berrigan D, Dodd K, et al. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181–188. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wannamethee S, Shaper A. Physical activity and cardiovascular disease. Sem Vasc Med. 2002;2(3):257–266. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whipp B, Davis J, Torres F, et al. A test to determine parameters of aerobic function during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1981;50:217–221. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.50.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]