ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

To examine patients’ use of and satisfaction with the nurse-staffed Telephone Health Advisory Service (THAS) and physician after-hours care in a rostered Family Health Organization, as well as physicians’ satisfaction with both types of services.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional telephone survey.

SETTING

A Family Health Organization in Hamilton, Ont.

PARTICIPANTS

Nineteen family physicians and their patients who used an after-hours service during 9 selected weeks between March and December of 2007.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Distribution of encounters directed to the on-call physician or to the THAS; types of health problems; and patient and physician satisfaction.

RESULTS

A total of 817 calls were recorded from 774 patients. Of these patients, 606 were contacted and 94.4% (572/606) completed encounter-specific surveys: 358 completed the on-call physician survey and 214 completed the THAS survey. Mean age of respondents was 40.8 years; most were women, and approximately one-third called on behalf of children. Most calls (66.8%, 546/817) were made directly to the on-call physicians. The most common problems were respiratory (34.3%, 271/789), gastrointestinal (10.1%, 80/789), and genitourinary (9.3%, 73/789). Most patients reported being very satisfied with the after-hours care provided by the THAS (62.5%, 125/200) or the on-call physicians (70.9%, 249/351). Almost all callers who bypassed the THAS knew about it (89.8%, 316/352), but either felt their problems were too serious or wished to talk to a physician. Most physicians agreed or strongly agreed that they were satisfied with their colleagues’ on-call care (81.0%, 17/21); 47.6% (10/21) agreed that the THAS was helpful in managing on-call duty.

CONCLUSION

When direct after-hours physician contact is available, a minority of patients uses a nurse-staffed triage. Physicians find the arrangements onerous and would prefer to see after-hours care managed and remunerated differently.

RÉSUMÉ

OBJECTIF

Déterminer le degré d’utilisation et de satisfaction des patients et des médecins relativement au Telephone Health Advisory Service (THAS) géré par des infirmières et aux soins en dehors des heures régulières dans une Organisation de santé familiale pour patients inscrits.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Enquête téléphonique transversale.

CONTEXTE

Une Organisation de santé familiale d’Hamilton, Ontario.

PARTICIPANTS

Dix-neuf médecins de famille et les patients qui avaient utilisé leurs services en dehors des heures régulières au cours de 9 semaines choisies entre mars et décembre 2007.

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES À L’ÉTUDE

Distribution des cas dirigés vers le médecin de garde ou le THAS; types de problèmes de santé; et satisfaction des patients et des médecins.

RÉSULTATS

On a enregistré 817 appels provenant de 774 patients. De ces derniers, 606 ont été contactés et 572 (94,4 %) ont répondu aux questions relatives à leurs rencontres; 358 ont répondu à l’enquête relative au médecin de garde et 214 à celle relative au THAS. Les répondants avaient en moyenne 40,8 ans; la plupart étaient des femmes, et dans environ un tiers des cas, elles appelaient pour des enfants. La plupart des appels (546/817, 66,8 %) étaient faits directement au médecin de garde. Les problèmes les plus fréquents étaient respiratoires (271/871, 34,3 %), gastro-intestinaux (80/789, 10,1 %) et génito-urinaires (73/789, 9,3 %). La plupart des patients se sont dits très satisfaits des soins prodigués hors heures régulières par le THAS (125/200, 62,5 %) ou par les médecins de garde (249/351, 70,9 %). Presque tous les patients qui ont évité le THAS connaissaient son existence (316/352, 89,8 %) mais soit qu’ils pensaient que leur problème était trop grave, soit qu’ils désiraient parler à un médecin. La plupart des médecins se disaient satisfaits ou très satisfaits des soins prodigués par leurs collègues de garde (17/21, 81,0 %); 47,6 % (10/21) reconnaissaient que le THAS était utile pour s’occuper de ce service de garde.

CONCLUSION

Quand ils peuvent contacter directement un médecin en dehors des heures régulières, très peu de patients choisissent un service de triage par des infirmières. Les médecins trouvent que cet arrangement est onéreux et préféreraient une gestion et une rémunération différentes pour les soins en dehors des heures régulières.

Optimal provision of after-hours medical services remains challenging from the perspectives of both patients and providers in our current health care system. Emergency departments overcrowded with patients presenting with emergent or deferrable primary care diagnoses and overextended family physicians reluctant to work more hours on call are testimony to this challenge. Provision of primary care outside of usual office hours has seen considerable change over the past 2 decades in Canada and in other Western countries.1–4 Many Canadian family doctors providing after-hours services have moved away from the single-practitioner model—one practitioner available at all times to practice patients—to models that include signing out to walk-in clinics, joining groups of physicians providing on-call care collaboratively, directing patients to emergency departments, or providing combinations of the above. Centralized telephone health advisory systems have also become one of the available options and are now often the first point of contact for patients seeking after-hours care.

As one response to addressing issues surrounding after-hours care, Ontario’s Primary Care Reform initiative contractually mandated provision of after-hours care by family physicians who joined Family Health Organizations (FHOs).5 These FHOs are capitation-funded practices that provide comprehensive medical care to rostered (registered) patients. Physician remuneration is based on the number of patients rostered rather than on fee-for-service payment. Physicians in FHOs provide an after-hours clinic for a predetermined number of hours on weeknights and weekends. In addition, the Ministry of Health provides the Telephone Health Advisory Service (THAS), a government-funded, nurse-staffed health advice and triage service for after-hours coverage of patients rostered in many of the province’s primary care models. The Ontario THAS nurse might offer advice on self-management, advise patients to speak to or see the FHO doctor on-call within a certain time frame, direct patients to an emergency department, or even call an ambulance. Physicians in the FHO model are expected to provide backup to the THAS 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Some FHOs also provide the option of speaking directly to the on-call physician.

Other research has reported on patient satisfaction, safety concerns, utilization (increased, decreased, or deferred visits), and utilization demographics with telephone triage in traditional payment models.6 European research has looked at determinants of patient satisfaction, clinical outcomes, and physician satisfaction with models of after-hours care.1,7 Little is known about utilization of after-hours care in rostered practices in Ontario in the FHO model, which provide after-hours clinics and backup support for the THAS.

This study examined how and which patients are using the THAS or direct physician after-hours care, as well as satisfaction of both patients and providers with different aspects of this care in an FHO.

METHODS

Participants were solicited from an FHO in Hamilton, Ont, comprising 22 physicians and approximately 40 000 rostered patients. These physicians alternate on-call duties to provide backup to the THAS and staff their after-hours patient clinic on weekday evenings and half-days on the weekend. Although located in separate offices, all physicians use the same after-hours message, advising patients to call the THAS number then providing another number for those calling from “a hospital, lab, nursing home, or anyone wishing to speak to the doctor on call.”

For patients who used the THAS or contacted the on-call physician after hours in 9 selected weeks in March, July, August, November, and December of 2007, a telephone survey was administered, usually the next day or within 7 days. The questionnaire was not formally assessed in terms of psychometric properties, but the questions had good face validity and respondents had few problems answering them. During the study weeks, staff collected both on-call physician encounters and THAS records. The survey asked about knowledge of the after-hours services offered by the practice, reasons for directly contacting the on-call physician (if applicable), frequency of use and reasons for use of after-hours services in the past year, satisfaction with the services, and demographic information. Physicians also completed a questionnaire on their satisfaction with the services. One author (I.N.) used on-call and THAS reports of calls received to abstract patients’ health problems.

In order to provide estimates of knowledge and use of the after-hours telephone service with a 95% confidence interval of plus or minus 4% or less, we estimated that at least 600 patients were required. Descriptive analyses were conducted to assess knowledge of, use of, and satisfaction with after-hours health services and to describe the demographic characteristics of patients using the services. Comparisons between demographic characteristics of patients who used the different services were made using χ2 or independent t tests, as appropriate. P values below .05 were considered statistically significant (2-tailed). Analyses were done with SPSS, version 15.0.0.

The study was approved by the Hamilton Health Sciences and Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Board.

RESULTS

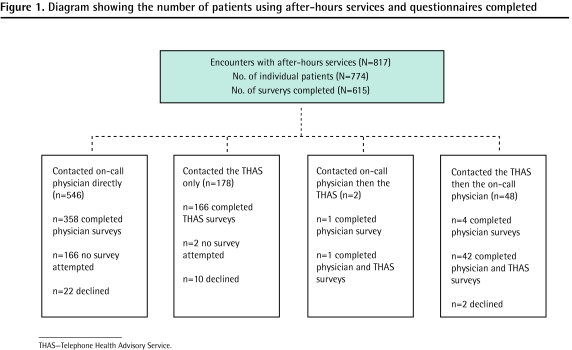

Of the 22 practices, 19 chose to participate in the patient surveys. During the data collection weeks, 817 calls were recorded from 774 unique patients. A total of 615 surveys were completed by 572 patients; some patients who contacted both the THAS and the on-call physicians completed both surveys (Figure 1). Surveys were not administered to 168 of the 774 patients (166 who contacted the on-call physician only and 2 who first contacted the THAS, then the on-call physician). These 168 encounters were mainly with patients from the 3 practices that did not participate in the study, or staff did not indicate that an attempt had been made to reach the matching patient. The refusal rate for completing the survey for those patients who were successfully contacted was 5.6% (34/606).

Figure 1.

Diagram showing the number of patients using after-hours services and questionnaires completed

Of the total 817 calls, 66.8% (546/817) were made only to the on-call physicians, 5.9% (48/817) were made to the THAS followed by the on-call physicians, 21.8% (178/817) were made to the THAS only, and less than 0.1% (2/817) were made twice to the on-call physicians then to the THAS. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of patients who completed the surveys. More than two-thirds of patients were female (76.3%, 432/566). Patients who contacted the physicians directly were significantly younger on average (mean 39.2 years, SD 19.8 years) compared with patients who contacted the THAS (mean 43.5 years, SD 16.6 years) (t = 2.73, df = 566; P = .008), and were less likely to report fair or poor health (9.6% [34/355] vs 15.0% [32/213]) (χ21 = 4.3, P = .04). More than one-third (34.9%, 182/521) of respondents were calling about their children. Among patients who contacted the physicians directly, 37.4% (134/358) reported that they had used after-hours services 3 or more times in the past year, compared with 32.8% (66/201) who had used the THAS for this current encounter (χ12 = 1.2, P = .28).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and past after-hours use among patients who telephoned their family physicians after hours and completed a survey about the services:Mean age for all patients was 40.8 (SD 18.7) years; for patients who contacted the on-call physician, 39.2 (SD 19.8) years; and for patients who contacted the THAS, 43.5 (SD 16.6) years (P = .008; t = 2.73, df = 566).

| CHARACTERISTICS | ALL PATIENTS, % (N/N*) | PATIENTS WHO CONTACTED PHYSICIAN, % (N/N*) | PATIENTS WHO CONTACTED THE THAS, % (N/N*) | P VALUE† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fair or poor self-reported health | 11.6 (66/568) | 9.6 (34/355) | 15.0 (32/213) | .05 (χ12 = 3.8) |

| High school or less education | 32.3 (173/536) | 34.3 (113/329) | 29.0 (60/207) | .20 (χ12 = 1.7) |

| Home is owned (vs rented) | 80.4 (448/557) | 82.8 (288/348) | 76.6 (160/209) | .07 (χ12 = 3.2) |

| ≤ 4 people living in home | 17.4 (98/564) | 17.5 (62/354) | 17.1 (36/210) | .91 (χ12 = 0.01) |

| English spoken at home | 97.0 (551/568) | 99.7 (346/347) | 97.2 (205/211) | .87 (χ12 = 0.03) |

| Married or common-law | 67.0 (376/561) | 65.9 (230/349) | 68.9 (146/212) | .47 (χ12 = 0.5) |

| Female | 76.3 (432/566) | 74.7 (266/356) | 79.8 (166/208) | .14 (χ12 = 2.2) |

| Household income in previous year | .09 (χ32 = 6. 8) | |||

| • < $30 000 | 6.6 (23/347) | 6.6 (13/198) | 6.7 (10/149) | |

| • $30 000–$79 999 | 34.9 (121/347) | 40.4 (80/198) | 27.5 (41/149) | |

| • ≥ $80 000 | 32.3 (112/347) | 28.8 (57/198) | 36.9 (55/149) | |

| • Unknown | 26.2 (91/347) | 24.2 (48/198) | 28.9 (43/149) | |

| Calling about child | 34.9 (182/521) | 35.0 (111/317) | 34.8 (71/204) | 96 (χ12= 0.001) |

| No. of times used after-hours care in past year. | 68 (χ12 = 0.17) | |||

| • 0 | 26.3 (147/559) | 26.3 (94/358) | 26.4 (53/201) | |

| • 1 | 17.7 (99/559) | 17.9 (64/358) | 17.4 (35/201) | |

| • 2 | 20.2 (113/559) | 18.4 (66/358) | 23.4 (47/201) | |

| • ≥ 3 | 35.8 (200/559) | 37.4 (134/358) | 32.8 (66/201) |

THAS–Telephone Health Advisory Service.

Not all respondents answered all questions.

For comparison of patients who contacted physician versus the THAS.

Among respondents who had contacted the on-call physicians directly, nearly all knew about the THAS (87.7%, 314/358) (Table 2). The most common reason for bypassing the THAS was the wish to speak to a physician directly (65.9%, 236/358), followed by the perception that the problem was too serious (24.9%, 89/358). Five percent (18/358) reported that they did not like their previous THAS experience.

Table 2.

Surveys by patients who used the on-call physician directly: N = 358.

| CHARACTERISTICS | % (N) |

|---|---|

| Listened to the physician’s after-hours telephone message | 89.4 (320) |

| Knew about the THAS | 87.7 (314) |

| Had both numbers written down at home | 48.9 (175) |

| Had reasons for bypassing the THAS (closed–ended questions) | |

| • Wished to see or speak to physician | 65.9 (236) |

| • Thought the problem was too serious | 24.9 (89) |

| • Did not like past THAS experience | 5.0 (18) |

| • Before the THAS available on Wednesday and Friday afternoons | 9.2 (33) |

| • Lack of awareness of the THAS | 1.7 (6) |

| • The THAS was inconvenient | < 0.1 (2) |

THAS–Telephone Health Advisory Service.

Nearly all patients who contacted the THAS reported that they followed the advice they were given (94.0%, 189/201). The most common advice was to see a physician within 24 hours (30.7%, 66/215), followed by instructions to go to the emergency department (22.3%, 48/215), and instructions for self-care (20.0%, 43/215). Approximately two-thirds of patients who used the THAS reported that they were very satisfied with the service they received (62.5%, 125/200); 70.9% (249/351) of patients who contacted the on-call physicians directly were satisified with the service they received (χ12 = 4.2; P = .04).

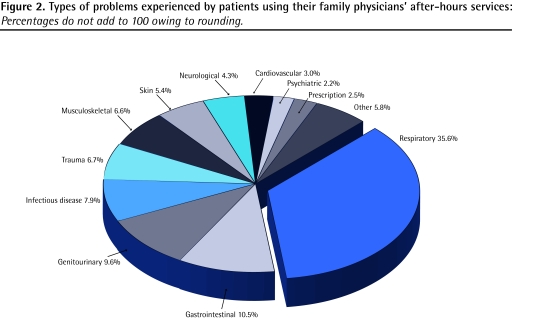

There were 762 health problems for the 817 calls (Figure 2); some surveys were completed but not attached to their original documents and could not be traced back. The largest proportion of calls was related to infections, many of which were respiratory.

Figure 2.

Types of problems experienced by patients using their family physicians’ after-hours services: Percentages do not add to 100 owing to rounding.

Twenty-one of 22 physicians completed the survey on their perceptions of after-hours services (Table 3). Most agreed or strongly agreed that on-call physicians gave similar advice or treatment to what they would give (81.0%; 17/21), and the same number agreed or strongly agreed that they were satisfied with the care provided by their colleagues. Approximately half (47.6%, 10/21) agreed or strongly agreed that the THAS was helpful in managing on-call duty, but fewer (28.6%, 6/21) agreed or strongly agreed that the THAS gave the same advice they would. Most (70.0%, 14/20) felt that on-call services should be staffed by locums or nurse practitioners, and 95.2% (20/21) thought on-call duties should be a separate service and remunerated differently.

Table 3.

Physician perceptions, attitudes, and satisfaction with after-hours care

| PERCEPTION | % (N/N*) |

|---|---|

| Perception of colleagues’ on-call coverage | |

| • Always or often receive on-call reports from group | 100 (19/19) |

| • Agree or strongly agree that reports clearly outline problems and dispositions | 85.7 (18/21) |

| • Agree or strongly agree that on-call physician telephones next day for urgent cases | 66.7 (14/21) |

| • Agree or strongly agree that my patients tell me they are satisfied | 19.0 (4/21) |

| • Agree or strongly agree that patients are seen and assessed in on-call clinic appropriately for semiurgent and urgent problems | 81.0 (17/21) |

| • Agree or strongly agree that advice and treatment given by on-call doctor is similar to what I would give | 81.0 (17/21) |

| • Agree or strongly agree that on-call doctor is respectful, considerate, professional to my patients | 81.0 (17/21) |

| • Satisfied with my on-call colleagues’ care of my patients | 81.0 (17/21) |

| Perception of the THAS | |

| • Agree or strongly agree that telephone triage is helpful in managing on-call duty | 47.6 (10/21) |

| • Agree or strongly agree that telephone triage gives same advice I would | 28.6 (6/21) |

| • Agree or strongly agree that the THAS is user-friendly to physicians | 33.3 (7/21) |

| • Agree or strongly agree that nurse communicates problems concisely and efficiently | 33.3 (7/21) |

| • Agree or strongly agree that the THAS calls after 10 PM should be routed to emergency department | 57.1 (12/21) |

| Perception of on-call duties | |

| • On-call services should be mandated for all physicians | 66.7 (14/21) |

| • On-call services should be a separate service remunerated differently | 95.2 (21/22) |

| • On-call services are onerous | 66.7 (14/21) |

| • Agree with a separate after-hours system for noncritical care staffed by others (eg, locum, nurse practitioner) | 70.0 (14/20) |

| • On-call obligations make family medicine less attractive to medical graduates | 76.2 (16/21) |

THAS–Telephone Health Advisory Service.

Not all respondents answered all questions.

DISCUSSION

Most patients are aware of the THAS, but when direct physician contact is available, most prefer and are most satisfied with physician contact for after-hours care. This appears to be related to patient preference and a perceived need for immediate physician contact rather than to the urgency of the problem. Most callers interpreted their health problems to be serious and immediate, requiring direct physician input and access; however, diagnoses and disposition of calls indicated that most of the problems appeared to be semiurgent or nonurgent. This might be related to the expectations of the patients in the study, mostly young or middle-aged women of high socioeconomic status and self-reported good health, who might have had high expectations of the availability of their family physicians. As well, patients calling on behalf of children might have been more likely to see the problems as urgent. Younger patients have been reported to have lower levels of satisfaction with after-hours care8 and older patients tend to have higher levels of satisfaction and somewhat lower expectations of their primary care services.9 In this study, demographics of callers and reasons for calls of both groups were similar to recent Ontario government THAS statistics, which reported that 61% of callers were female and 46% were calling for others,10 and to those of European and Australian studies of after-hours calls.11,12 Considering that older patients have more health problems, it was surprising that the average age of callers was approximately 40 years. Older patients might be sicker, leading them to go directly to the emergency department. It has also been suggested that younger patients might be more comfortable with advice given over the telephone than older patients are.11

Patients were highly satisfied with both the THAS and the physicians on call. This is similar to the 2007 Ontario THAS bulletin reporting that more than 95% of callers were satisfied with the service.10 Studies in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom found that satisfaction was related to patients’ anticipated outcome of their calls with respect to the mode of care they hoped to receive, rather than the on-call systems used.7,13 In our after-hours system, patients are aware that physicians offer a clinic for several hours in the evening and on Saturdays and Sundays. We speculate that in our study most patients called the physician first because they could often get the anticipated visit or at least speak to the physician. In addition, some patients might not have been aware that the THAS is a triage service that could lead to seeing or speaking to a physician directly, and might have believed they would only receive telephone advice. About two-thirds of patients in this survey had used on-call services up to 3 times in the past year. This suggests a group of patients who are frequent users. This frequency might reflect calls about children. Patients also tended to use the same service they had used previously.

Physicians and the THAS saw, treated, or advised 774 patients. Although patient intentions were not studied, it is possible that a large number of these patients avoided unnecessary emergency department and walk-in clinic visits. Taken together with patient satisfaction, this model appears to provide appropriate after-hours care.

The other part of the on-call equation is the providers. On-call changes have been introduced largely because of physicians being unwilling or unable to be available to their patients at all times, as expectations and complexity of care have escalated. The physicians in our study deemed the quality of care provided by their colleagues to be excellent in terms of communication around patient visits and disposition of patient problems. Physicians reported that their colleagues were respectful, considerate, and professional, and that they gave advice similar to what the physicians would have provided themselves.

A limitation of this study was that surveys were conducted by office staff who might have been known to the patients. This could have influenced patients’ responses, particularly around issues of satisfaction.

Conclusion

In this group of family practices with shared after-hours coverage, most patients, if given a choice, chose direct contact with the on-call physician rather than using the nurse-staffed THAS. This model of care, although satisfactory to patients, might overestimate the contribution of the THAS to relieving physician burden of on-call duty in those practices providing direct access to on-call doctors. This phenomenon of patients bypassing the THAS might reflect the findings of a recent study showing that, increasingly, only a very small number of practices provide direct physician access after hours.14 New models of after-hours care will need to satisfy patients’ expectations of care, perceptions of urgency, and desire for physician involvement in their care, as well as physician willingness to provide this care.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Many Canadian family doctors providing after-hours services have moved away from the single-practitioner model one practitioner available at all times to practice patients to models that include signing out to walk-in clinics, joining groups of physicians providing collaborative on-call care, directing patients to emergency departments, or a combination of the above.

This study examined which patients are using the Telephone Health Advisory Service (THAS) compared with direct physician after-hours care and how, as well as satisfaction of both patients and providers with different aspects of these services in a Family Health Organization.

Most patients are aware of the THAS, but when direct physician contact is available, most prefer and are most satisfied with physician contact for after-hours care. Nevertheless, patients were highly satisfied with both the THAS and on-call physicians.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Bon nombre de médecins de famille canadiens qui fournissent des services en dehors des heures régulières ont abandonné le modèle de pratique en solo – un médecin disponible en tout temps pour sa clientèle – pour adopter des modèles comme une participation à des cliniques sans rendez-vous, l’adhésion à des groupes de médecins qui collaborent à des gardes sur appel, l’orientation des patients aux services des urgences ou une combinaison de ces possibilités.

Cette étude voulait savoir quels patients utilisent le Telephone Health Advisory Service (THAS) plutôt que les soins prodigués directement par les médecins en dehors des heures régulières, et de quelle façon, et connaître le degré de satisfaction des patients et des dispensateurs de soins sur divers aspects de ces services dans une Organisation de santé familiale.

La plupart des patients connaissaient l’existence du THAS, mais quand ils pouvaient avoir un contact direct avec un médecin, la plupart préféraient et appréciaient davantage le contact avec un médecin pour les soins en dehors des heures régulières. Les patients étaient néanmoins très satisfaits tant du THAS que des médecins de garde.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors

Dr Neimanis developed the concept of the study, devised the questionnaires, drafted the manuscript, and interpreted some of the raw data. Dr Kaczorowski participated in the design of the study, data collection, and drafting and revision of the manuscript and gave final approval for publication. Dr Howard contributed to study design, acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript.

Competing interests

None declared

*Full text is available in English at www.cfp.ca.

References

- 1.Leibowitz R, Day S, Dunt D. A systemic review of the effect of different models of after-hours primary medical care services on clinical outcome, medical workload, and patient and GP satisfaction. Fam Pract. 2003;20(3):311–7. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herbert H. Should general practitioners resume 24 hour responsibility for their patients? No. BMJ. 2007;335(7622):697. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39350.516887.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crighton EJ, Bordman R, Wheler D, Franssen E, White D, Bovett M, et al. After-hours care in Canada. Analysis of the 2001 National Family Physician Workforce Survey. Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:1504–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glynn LG, Byrne M, Newell J, Murphy AW. The effect of health status on patients’ satisfaction with out of-hours care provided by a family doctor cooperative. Fam Pract. 2004;21(6):679–85. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Harmonized Family Health Organization agreement among Her Majesty the Queen, in right of Ontario, as represented by the Minister of Health and Long-Term Care and Innovations Family Health Organization; part 111—operational; article 5.2 service obligations; (b) iii re outside of regular office hours operations. Toronto, ON: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bunn F, Byrne G, Kendall S. Telephone consultation and triage: effects on health care use and patient Satisfaction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD004180. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004180.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKinley RK, Stevenson K, Adams S, Manku-Scott TK. Meeting patient expectations of care: the major determinants of satisfaction with out-of-hours primary medical care? Fam Pract. 2002;19(4):333–8. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.4.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKinley RK, Roberts C. Patient satisfaction with out of hours primary medical care. Qual Health Care. 2001;10(1):23–8. doi: 10.1136/qhc.10.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell JL, Ramsay J, Green J. Age, gender, socioeconomic, and ethnic differences in patients’ assessments of primary health care. Qual Health Care. 2001;10(2):90–5. doi: 10.1136/qhc.10.2.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Government of Ontario. THAS update [pamphlet] Toronto, ON: Government of Ontario; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner VF, Bentley PJ, Hodgson SA, Collard PJ, Drimatis R, Rabune C, et al. Telephone triage in Western Australia. Med J Aust. 2002;176(3):100–3. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moll van Charante EP, ter Riet G, Drost S, van der Linden L, Klazinga N, Bindels PJ. Nurse telephone triage in out-of-hours GP practice: determinants of independent advice and return consultation. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giesen P, Moll van Charante E, Mokkink H, Bindels P, van den Bosch W, Grol R. Patients evaluate accessibility and nurse telephone consultations in out-of-hours GP care: determinants of a negative evaluation. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65(1):131–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.021. Epub 2006 Aug 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howard M, Randall G. After-hours information given by telephone by family physicians in Ontario. Healthc Policy. In press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]