SUMMARY

Contact chemosensation is required for several behaviors that promote the survival of fruit flies and other insects. These include evasive behaviors such as the suppression of feeding on dangerous repellent compounds, referred to as antifeedants. Contact chemosensation also contributes to the suppression of male-male courtship. However, the identities of the gustatory receptors (GRs) required for the responses to non-volatile avoidance chemicals are largely unknown. Exceptions include GR66a and GR93a, which are required specifically to prevent ingestion of caffeine [1, 2], and GR32a, which is necessary for inhibiting male-male courtship [3]. However, GR32a is dispensable for normal taste. Thus, distinct GRs may function in the sensing of avoidance pheromones and in detecting different subsets of antifeedants. Here, we describe the requirements for GR33a, which is expressed widely in gustatory receptor neurons (GRNs) that respond to aversive chemicals. Gr33a mutant flies were impaired in the avoidance responses to all non-volatile repellents tested, ranging from quinine to denatorium, lobeline and caffeine. Gr33a mutant males also displayed increased male-to-male courtship implying that it functioned in the detection of a repulsive male pheromone. In contrast to the broadly required olfactory receptor (OR) OR83b, which is essential for trafficking of other ORs [4], GR66a and GR93a were localized normally in Gr33a mutant GRNs. Thus, rather than regulating trafficking of GRs, GR33a may function as co-receptor required for sensing all non-volatile repulsive chemicals, including tastants and pheromones.

Results and Discussion

Candidate GRs that function in contact chemosensation identified by DNA microarrays

The Drosophila GR family [5] is distinct from other groups of chemosensory receptors in that it includes members that function in both contact [1-3, 6-11] and non-contact chemosensation [12, 13]. To identify additional GRs that might function in contact chemosensation, which includes taste and the detection of non-volatile pheromones, we performed DNA microarrays. To conduct this analysis we took advantage of a mutant, poxn [14], in which the chemosensory sensilla (bristles) were transformed to mechanosensory bristles. The major taste organ in the fly is the labellum. Therefore, we prepared RNA from labella dissected from wild-type and poxn flies, since enrichment in wild-type labella would therefore indicate that the RNA was expressed in taste sensilla. The Gr RNAs most enriched in the wild-type labella were Gr66a and several members of the Gr64 cluster that are expressed in the sugar responsive GRNs (Table S1; enrichments were 6.1 to 14.6 fold). The Gr that was the next most enriched in wild-type sensilla was Gr33a (Table S1; 5.5-fold enrichment), which was the Gr most related to Gr66a (Figure S1).

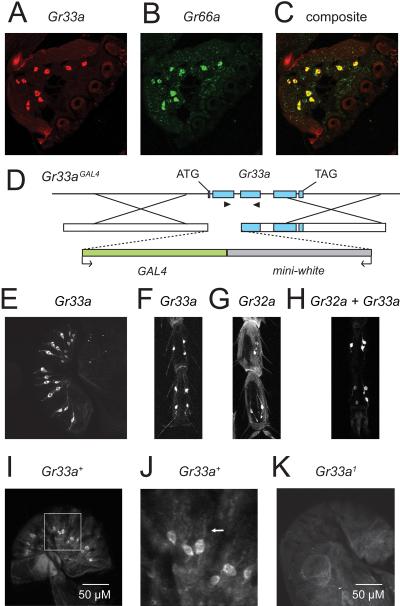

GR33a was expressed in GRNs that respond to repulsive chemicals

To validate that Gr33a was expressed in GRNs, we characterized the spatial distributions of the Gr33a RNA, a Gr33a reporter and the endogenous GR33a protein. To examine the Gr33a RNA expression pattern, we performed in situ hybridizations and found that ~20 GRNs in the labella expressed Gr33a (Figure 1A). Since GR33a is most related to GR66a and there is a precedent that highly related GRs tend to be expressed in the same GRNs [6, 12, 13], we tested whether the two Gr RNAs were co-expressed. We found that all of the Gr33a expressing GRNs expressed the Gr66a RNA and vice versa (Figures 1A - 1C). Thus, Gr33a appeared to be expressed exclusively in GRNs that respond to repulsive chemicals.

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of Gr33a. (A-C) In situ hybridizations of Gr33a and Gr66a RNAs. Fluorescent double in situ hybridizations revealed co-expression of Gr33a and Gr66a RNAs in wild type labella (n=5). (A) Gr33a RNA. (B) Gr66a RNA. (C) Composite of Gr33a and Gr66a RNAs. (D) Structure of Gr33a locus and targeting scheme used to generate the Gr33aGAL4 allele by homologous recombination. The arrowheads indicate primers used for the PCR analysis (Figure S3B). The arrows at the bottom indicate the orientations of the GAL4 and white genes. (E) Gr33a reporter expression in labella (n=10). (F-H) Comparison of Gr33a and Gr32a reporter (Gr32a-GAL4) expression in male prothoracic legs (n=6). Since we used GAL4 lines to detect Gr33a or Gr32a expression, it was not possible to perform double-labeling. Therefore, we examined UAS-mCD8∷GFP expression in flies containing the individual transgenes (Gr33aGAL4/+ or Gr32a-GAL4) or both together. (F) Gr33a reporter expression. (G) Gr32a reporter expression. (H) Combination of both Gr33a and Gr32a reporter expression. (I-K) Expression of the endogenous GR33a protein (n=10). Anti-GR33a immunostaining in Gr33a+ (w1118) or Gr33a1 mutant labella. (I) Gr33a+ labellum. (J) Enlarged view of a portion of the Gr33a+ labellum shown in panel I (indicated by the box). The arrow indicates a GR33a positive dendrite. (K) Gr33a1 allele.

To provide a more sensitive reagent to characterize the cellular distribution of Gr33a, we generated a Gr33a reporter. We used homologous recombination [15] to insert the GAL4 gene at the site of the normal Gr33a translation initiation codon (Figure 1D; Gr33aGAL4) and assayed for Gr33a reporter expression using the GAL4/UAS system [16] in conjunction with a UAS-mCD8∷GFP. The GFP was expressed in the labellum consistent with the in situ hybridizations (Figure 1E). Examination of multiple confocal sections indicated that the Gr33a reporter was expressed in ~20 cells, which was similar to the number of cells positive for the Gr66a reporter [17, 18] and Gr33a RNA.

Since leg tarsi also contain gustatory sensilla, we examined the expression of GFP in the legs. The Gr33a reporter was expressed in multiple GRNs in the legs. These include seven in the prothoracic legs, four in the mesothoracic and four in the 3rd thoracic legs (Figure 1F). Several of the Gr33a positive GRNs in the prothoracic legs appeared to express the previously described Gr32a reporter [3, 18] (Figures 1G, 1H and Table S2). Gr33a reporter expression was indistinguishable between males and females (data not shown).

To analyze the subcellular localization of the GR33a protein in GRNs, we raised anti-GR33a antibodies. We found that the anti-GR33a signal was distributed throughout the GR33a-positive GRNs, including the dendrites, axons and cell bodies (Figures 1I, 1J and Figure S2A). This subcellular distribution of GR33a is reminiscent of GR93a and an odorant receptor (OR), OR83b, both of which are detected in cell bodies and neurites [1, 4]. The staining pattern appeared to be specific for GR33a since it was not detected in the labella of Gr33a mutant animals (see below; Figure 1K). To confirm that the Gr33a reporter reflected the endogenous cellular distribution of the GR33a protein, we performed double-labeling with anti-GFP and anti-GR33a antibodies. We found that the same cells were labeled with both antibodies demonstrating that the Gr33a reporter faithfully represented the GR33a expression pattern (Figure S2B). We did not detect a GR33a signal in tissues other than taste organs, including the central brain, fat bodies, gut, testis and accessory glands using either the Gr33a reporter or the anti-GR33a antibodies (data not shown).

Broad requirement for Gr33a for the gustatory responses to repellent chemicals

To characterize the role of Gr33a, we created two mutant alleles. The first allele was Gr33aGAL4 since the construct used to obtain the GAL4 reporter also deleted a portion of the Gr33a coding region (Figure 1D; residues 4 to 164). We generated a second allele by homologous recombination, Gr33a1, which deleted residues 1 to 199 of GR33a (Figure S3A). Based on PCR analyses of genomic DNA, the Gr33a gene was disrupted as intended in Gr33a1 and Gr33aGAL4 flies (Figure S3B). The Gr33a mutations did not appear to eliminate the Gr33a-expressing GRNs, since Gr66a RNA was still produced in the mutant GRNs (Figure S3C). Both Gr33a mutant alleles were homozygous viable (data not shown).

To address whether Gr33a null flies have a defect in taste sensation, we performed electrophysiological and behavioral assays. We tested directly for defects in the detection of gustatory stimuli in GRNs by inserting recording electrodes over the tips of taste sensilla and assaying for the production of tastant-induced action potentials. We also tested for behavioral consequences resulting from the Gr33a mutations using two-way choice assays. To perform this latter assay, we placed starved flies in 72 well microtiter dishes with two types of tastants mixed with either red or blue food coloring. Their abdomens appeared red, blue or purple, depending on whether or not they had a preference for a given tastant. A complete preference for one or the other tastant is indicated by a preference index of 1.0 or 0 while a value of 0.5 results if there is a lack of preference. As expected, since Gr33a was expressed in aversive GRNs, neither Gr33a1 nor Gr33aGAL4 flies showed a significant difference from control flies (w1118) in their electrophysiological or behavioral responses to sugars, such as sucrose (Figure S4).

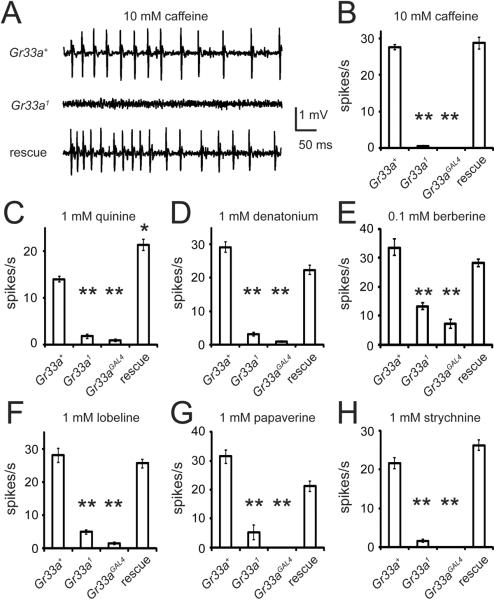

In contrast to the normal sugar responses, Gr33a mutant animals showed impairments in the response to all noxious chemical tested. The defects were most pronounced in the tip recording assays. The Gr33a+ control animals (w1118) produced action potentials upon presentation of aversive chemicals ranging from caffeine to quinine, denatorium, berberine, lobeline, papaverine and strychnine (Figures 2 and S5). In contrast, the frequencies of action potentials induced by these tastants were greatly reduced or eliminated in Gr33aGAL4 or Gr33a1 (Figures 2 and S5) or in the transheterozygous flies (Gr33a1/Gr33aGAL4; data not shown). The impairments were due to the mutations in Gr33a since the phenotypes were suppressed by introduction of a wild-type transgene (UAS-Gr33a+) in Gr33a1/Gr33aGAL4 flies (rescue; Figures 2 and S5). Introduction of the rescue construct in the mutant flies caused hypersensitivity to quinine and to the lower concentrations of denatorium, strychnine and caffeine (Figure S5), possibly due to slightly higher expression of GR33a in the transgenic flies than in w1118. These data support the conclusion that GR33a is required broadly for the avoiding noxious compounds.

Figure 2.

Gr33a was essential for production of action potentials in response to aversive compounds. Shown are the results of tip recordings using s6 sensilla. (A) Representative traces of caffeine induced nerve firings between 50 and 550 milliseconds after application of the recording electrode. The flies used to test for rescue of the Gr33a mutant phenotype by the wild-type Gr33a+ transgene were: Gr33a1/Gr33aGAL4;UAS-Gr33a. The Gr33aGAL4 mutant allele did not show a response to caffeine (data not shown). (B-H) Quantification of the mean action potentials (spikes per second) induced by the indicated noxious chemicals. The genotypes are listed below. The means were based on data collected between 50 and 1050 ms after presentation of the compounds. The error bars represent SEMs. The data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Scheffe's post-hoc analysis. The asterisks indicate statistically significant differences from the Gr33a+ control (* P<0.05, ** P<0.01). Detailed statistics are presented in Table S3. See Figure S5 for dose response analyses, which include the data summarized in this figure.

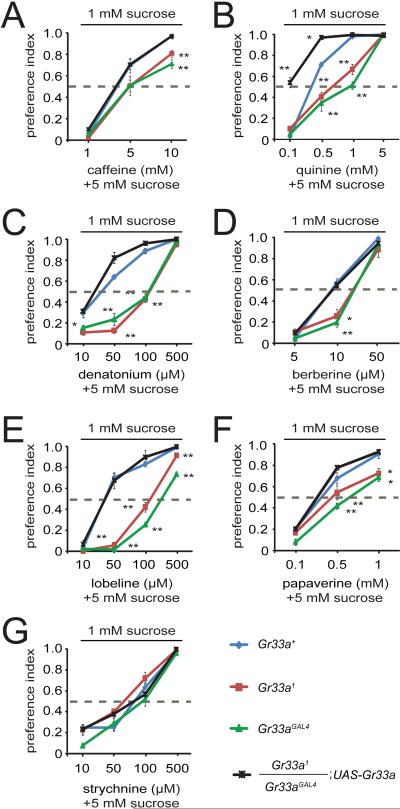

To assay the behavioral consequences resulting from disruption of Gr33a, we performed two-way choice assays. We performed the assay by comparing the preferences for a lower concentration of a sugar (1 mM sucrose) versus a higher concentration of sugar (5 mM sucrose) in combination with a repulsive tastant, as previously described [19]. Since 5 mM sucrose is preferred over 1 mM sucrose (Figure S4C), a selection of 1 mM sucrose in this assay indicates an aversion to the compound mixed with the 5 mM sucrose.

With one exception (strychnine), we found that the behavioral responses to the repulsive compounds were reduced in both Gr33a alleles, and each of the defects was rescued by introduction of the wild-type Gr33a+ transgene (Figure 3). At the higher concentrations of aversive compounds, Gr33a mutant flies tended to select 1 mM sucrose over the 5 mM sucrose/bitter compound cocktails. These results are not necessarily inconsistent with the tip recordings since bitter compounds also suppress the ability of S cells to sense sugars [19]. Thus, when mixing 5 mM sucrose with high concentrations of bitter compounds, the 1 mM sucrose may be perceived as sweeter than the 5 mM sucrose. The absence of a behavioral phenotype in response to strychnine might indicate that the sugar responsive S cell in the s6 sensilla is very sensitive to inhibition by strychnine. Alternatively, we cannot exclude that there exists another strychnine receptor that is expressed in a subset of sensilla that we did not assay in the tip recordings. Expression of the Gr33a+ transgene caused the flies to display increased repulsion to quinine (Figure 3B). This was most pronounced in response to the lowest concentration of quinine tested (0.1 mM). The Gr33a+ control and mutant flies strongly preferred the 5 mM sucrose plus 0.1 mM quinine, while the transgenic flies expressing the rescue construct no longer had a bias for this 5 mM sucrose/0.1 mM quinine cocktail.

Figure 3.

Gr33a mutant flies display reduced avoidance to most bitter chemicals. (AG) The two-way choice behavioral assays were performed by giving the flies a choice between 1 mM sucrose alone or 5 mM sucrose in combination with the indicated concentrations of aversive chemicals. A value of 1 indicates a complete preference for 1 mM sucrose, while a value of 0 indicates a complete preference for the 5 mM sucrose mixed with the aversive chemical. A value of 0.5 indicates no preference for the two alternative tastants. The strains used were: Gr33a+ (w1118; blue lines), Gr33a1 (red), Gr33aGAL4 (green) and Gr33a1/Gr33aGAL4;UAS-Gr33a (black). We used one-way ANOVA followed by Scheffe's post-hoc analysis to perform tests for statistical significance. The error bars represent SEMs. The asterisks indicate statistically differences from the Gr33a+ control (* P<0.05, ** P<0.01). Detailed statistics are presented in Table S4.

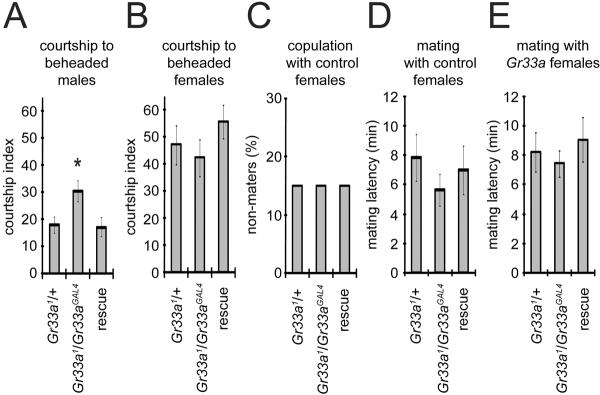

Mutation of Gr33a increased male-male courtship

Since Gr33a mutant flies are unresponsive to all aversive tastants tested, we wondered whether it was also required for inhibiting male-male courtship, since this behavior is suppressed by an inhibitory pheromone present on the male cuticle [20]. This possibility was further supported by the observation that the Gr32a+ gene product, which suppressed male-male courtship [3], appeared to be co-expressed in the legs with Gr33a (Figures 1F - 1H). In support of this conclusion, we detected the same number of GFP-positive (UAS-mCD8∷GFP) neurons in flies harboring the Gr33a-GAL4 alone (Gr33aGAL4/+) or both the Gr33aGAL4/+ and Gr32a-GAL4 drivers (Gr33aGAL4/+ and Gr32a-GAL4; Table S2).

To test whether the Gr33a mutation increased male-male courtship, we combined Gr33a+ and mutant males with passive decapitated wild-type males as described [3]. The courtship index was the percentage of time during a 10-minute interval that the male engaged in courtship behaviors, including vibration of the wing, licking and attempted copulation. We found that the Gr33a1 male flies displayed increased courtship toward passive, decapitated males (Figure 4A). This phenotype was rescued by the Gr33a+ transgene (Figure 4A). In contrast, courtship of Gr33a1 males to decapitated or normal females was not different significantly from the Gr33a+ males (Figures 4B - 4D). Gr33a mutant and Gr33a+ females did not display significant differences in mating (Figures 4E and data not shown). These results raise the possibility that Gr33a is required for sensing an inhibitory male pheromone.

Figure 4.

Increased male-to-male courtship behavior in Gr33a mutant flies. (A) Courtship behavior between males of the indicated genotypes and passive (beheaded) males. The courtship index is the percentage of time that the intact males exhibited courtship behavior during the 10-min observation time. (B) Courtship behavior exhibited by males of the indicated genotypes to beheaded females. (C) Fraction of males that did not mate to Gr33a+ intact females. (D) Time to copulation with Gr33a+ control females. (E) Average latency time for the Gr33a+ males to mate with indicated females. The error bars represent SEMs. ANOVA with the Scheffe's post-hoc tests were used to compare multiple sets of data (A, B, D and E) and the Chi-square test was used to test the statistical significance of non-maters (C). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The asterisks indicate statistically differences from the Gr33a+ control (* P<0.05, ** P<0.01). Detailed statistics are presented in Table S5.

Normal GR trafficking in the absence of GR33a

The observation that GR33a is required for responding to every avoidance compound tested, raises the possibility that it is co-required with other GRs for the responses to aversive chemicals. Consistent with this proposal, misexpression of Gr33a alone in tissue culture cells or in Gr5a-expressing GRNs was insufficient to confer sensitivity to any aversive compound tested (Moon and Montell, unpublished observations). Thus, the receptors for repellent chemicals may be comprised of at least two subunits. A minimum of three Grs is required for the response to caffeine, Gr66a, Gr93a and Gr33a; however, misexpression of all three Grs does not produce a response to caffeine (Moon and Montell, unpublished observations). Thus, the complexity of these receptors may be greater than either the Drosophila CO2 heterodimeric receptor [12, 13] or the mammalian taste receptors, which consist of homo- and heterodimers [21]. Since GR64f functions in concert with GR5a or GR64f for sugar sensation [7], it appears that distinct GRs (GR64f and GR33a) are broadly co-required with other receptors for the responses to sugars and avoidance chemicals.

In the Drosophila olfactory system, OR83b is required for trafficking of other ORs in olfactory sensory neurons [4]. To address whether GR33a may play a similar role, we compared the spatial distribution of GR93a in Gr33a+ and Gr33a mutant GRNs. As we have shown recently, GR93a is detected in dendrites, axons and cell bodies of wild-type avoidance GRNs [1] (Figure S6A). We found that anti-GR93a staining was indistinguishable in the Gr33a mutant (Figure S6B). To address whether GR66a was dependent on GR33a, we used transgenic flies expressing Myc-tagged GR66a (Myc∷GR66a), which rescues the Gr66a mutant phenotype [2]. As with GR93a, the Myc-GR66a protein was detected in dendrites, axons and cell bodies in Gr33a+ GRNs (Figure S6C). This spatial distribution was unchanged in a Gr33a mutant background (Figure S6D).

We conclude that GR33a does not function in receptor trafficking, as is the case for OR83b in olfactory receptor neurons. These results raise the possibility that GR33a serves as an obligatory receptor subunit for the detection rather than the trafficking of all repellent compounds that are sensed through contact chemosensation, including aversive tastants and pheromones. Since three GRs are required but not sufficient for sensing caffeine, the complexity of the aversive GRs may be greater than that of any known chemoreceptor.

Future perspective

The identification of GR33a as the first molecular target required broadly for detection of all antifeedants, provides the possibility of screening for GR33a inhibitors, which would promote the intake of noxious chemicals and result in improved insect control. Since many GRs such as GR33a are divergent between Drosophila and other insects, such as Anopheles gambiae (28% identical with GPRGR43) [22, 23], such inhibitors have the potential to selectively target GRs in disease vectors but not in other insects that would be of benefit to maintain.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tao Wang for generating the pw35GAL4 vector. Y. L. was supported in part by a Korea Research Foundation postdoctoral fellowship (2006-352-C00065). S.J.M. was supported in part by a grant from the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare & Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (A084254). This study was supported by a grant to C.M. from the NIDCD (DC007864).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lee Y, Moon SJ, Montell C. Multiple gustatory receptors required for the caffeine response in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:4495–4500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811744106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moon SJ, Köttgen M, Jiao Y, Xu H, Montell C. A taste receptor required for the caffeine response in vivo. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1812–1817. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyamoto T, Amrein H. Suppression of male courtship by a Drosophila pheromone receptor. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:874–876. doi: 10.1038/nn.2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larsson MC, Domingos AI, Jones WD, Chiappe ME, Amrein H, Vosshall LB. Or83b encodes a broadly expressed odorant receptor essential for Drosophila olfaction. Neuron. 2004;43:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson HM, Warr CG, Carlson JR. Molecular evolution of the insect chemoreceptor gene superfamily in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100(Suppl 2):14537–14542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335847100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiao Y, Moon SJ, Montell C. A Drosophila gustatory receptor required for the responses to sucrose, glucose, and maltose identified by mRNA tagging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:14110–14115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702421104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiao Y, Moon SJ, Wang X, Ren Q, Montell C. Gr64f is required in combination with other gustatory receptors for sugar detection in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:1797–1801. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahanukar A, Lei YT, Kwon JY, Carlson JR. Two Gr genes underlie sugar reception in Drosophila. Neuron. 2007;56:503–516. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahanukar A, Foster K, van der Goes van Naters WM, Carlson JR. A Gr receptor is required for response to the sugar trehalose in taste neurons of Drosophila. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:1182–1186. doi: 10.1038/nn765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bray S, Amrein H. A putative Drosophila pheromone receptor expressed in male-specific taste neurons is required for efficient courtship. Neuron. 2003;39:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slone J, Daniels J, Amrein H. Sugar receptors in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:1809–1816. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon JY, Dahanukar A, Weiss LA, Carlson JR. The molecular basis of CO2 reception in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:3574–3578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700079104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones WD, Cayirlioglu P, Grunwald Kadow I, Vosshall LB. Two chemosensory receptors together mediate carbon dioxide detection in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;445:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature05466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Awasaki T, Kimura K. pox-neuro is required for development of chemosensory bristles in Drosophila. J. Neurobiol. 1997;32:707–721. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19970620)32:7<707::aid-neu6>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gong WJ, Golic KG. Ends-out, or replacement, gene targeting in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:2556–2561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0535280100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z, Singhvi A, Kong P, Scott K. Taste representations in the Drosophila brain. Cell. 2004;117:981–991. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorne N, Chromey C, Bray S, Amrein H. Taste perception and coding in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:1065–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meunier N, Marion-Poll F, Rospars JP, Tanimura T. Peripheral coding of bitter taste in Drosophila. J. Neurobiol. 2003;56:139–152. doi: 10.1002/neu.10235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lacaille F, Hiroi M, Twele R, Inoshita T, Umemoto D, Maniere G, Marion-Poll F, Ozaki M, Francke W, Cobb M, et al. An inhibitory sex pheromone tastes bitter for Drosophila males. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandrashekar J, Hoon MA, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. The receptors and cells for mammalian taste. Nature. 2006;444:288–294. doi: 10.1038/nature05401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill CA, Fox AN, Pitts RJ, Kent LB, Tan PL, Chrystal MA, Cravchik A, Collins FH, Robertson HM, Zwiebel LJ. G protein-coupled receptors in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2002;298:176–178. doi: 10.1126/science.1076196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kent LB, Walden KK, Robertson HM. The Gr family of candidate gustatory and olfactory receptors in the yellow-fever mosquito Aedes aegypti. Chemical senses. 2008;33:79–93. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjm067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.