Abstract

Little is known about the lives of adults with sickle cell disease (SCD). This article reports findings from a qualitative pilot study, which used life review as a method to explore influences on health outcomes among middle-aged and older adults with SCD, Six females with SCD, recruited from two urban sickle cell clinics in the U.S., engaged in semi-structured, in-depth life review interviews. MaxQDA2 software was used for qualitative data coding and analysis. Three major themes were identified: vulnerability factors, self-care management resources, and health outcomes. These themes are consistent with the Theory of Self-Care Management for Sickle Cell Disease. Identifying vulnerability factors, self-care management resources, and health outcomes in adults with SCD may aid in developing theory-based interventions to meet health care needs of younger individuals with SCD. The life review process is a useful means to gain insight into successful aging with SCD and other chronic illnesses.

Keywords: Life review, quality of life, sickle cell disease, successful aging

Sickle cell disease (SCD), an inherited autosomal recessive disorder, is expressed as sickle cell anemia, sickle cell thalassemia disease, or sickle hemoglobin C disease, depending on the mode of inheritance (Andrews & Mooney, 1994; Godeau et al., 2001). SCD is a chronic blood disorder, and it is caused by a mutation that produces defective hemoglobin (Reed & Vichinsky, 1998; Yang, Shah, Watson, & Mankad, 1995). This genetic mutation may eventually cause damage to every system in the body. People with SCD may suffer from a lifelong disorder characterized by recurrent and unpredictable episodes of pain, hemolytic anemia, anemic crises, stroke, infections, renal and pulmonary problems, and numerous problems related to organ dysfunction of varying severity (Ballas, 1999; Godeau et al., 2001).

A Lifetime of Pain

Sickle cell disease (SCD) and its manifestations result in a lifetime of pain and hospitalizations and most often affect African Americans, a vulnerable minority population in the U.S. (Dorsey, Phillips, & Williams, 2001; Maxwell & Streetly, 1998). The pain of SCD results from the lack of oxygen that occurs when sickle-shaped red blood cells occlude blood vessels. Fatigue, nausea, and tenderness of the joints are some of the signs and symptoms characterizing the prodromal phase of a vaso-occlusive episode (Ballas, 1995, Jacob et al., 2005). The onset of pain may be gradual; however, it often occurs suddenly (Jacob et al., 2005; Ballas, 1995). The words, “throbbing” and “stabbing” have been used to describe the pain when it peaks (Beyer, Simmons, Woods, & Woods, 1999, p. 918). Children and adults report that the pain of SCD does not decrease until 4–5 days after hospitalization (Ballas, 1995, Jacob et al., 2005).

Although advances in modern medicine have enabled the detection of SCD, people with SCD often receive inadequate health care and may lack the necessary skills needed to improve their self-care strategies and quality of life (QOL) (Jenerette & Phillips, 2006; Jenerette, Funk, & Murdaugh, 2005). Patients with SCD frequently report dissatisfaction with the care they receive, particularly related to pain relief (Booker, Blethyn, Wright, & Greenfield, 2006; Gorman, 1999; Jacob et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2005). To avoid a long wait in the emergency department (ED), patients with SCD frequently try to manage their pain at home (Beyer et al., 1999; Jacob et al., 2005); however, inadequate pain relief may continue after the patient has entered the ED (Jacob et al., 2005). Inadequate pain relief often results in a poor QOL (Bolten, Kempel-Waibel, & Pforringer, 1998; Osman et al., 2000; Strickland, Jackson, Gilead, McGuire, & Quarles, 2001). Increased self-care ability is critical to improve QOL and health status for people living with SCD.

An Acceptable Quality of Life

When a chronic illness like SCD has been diagnosed, managing symptoms and maintaining control over the course of the disease, while assisting the individual to achieve an acceptable QOL, should be major foci of healthcare providers’ interventions (Corbin, 1991; Watkins et al., 2000). Interventions must. support the coping strategies of people with SCD, who have reported that during a painful episode, diversion activities, such as praying, are beneficial (Beyer et al., 1999; Atkin & Ahmad, 2001; Fletcher & Hayes, 2000). The health care literature suggests that prayer and a belief in God are cherished values within the African American community (Harrison et al., 2005; Strickland et al., 2001; Wilson & Miles, 2001). Health care providers must acknowledge the importance of religion and spirituality to adults with SCD.

Mortality in adults with SCD has greatly decreased due to early detection and recent improvements in effective, comprehensive treatment (Claster & Vichinsky, 2003; Wilson, Krishnamurti, & Kamat, 2003). Clinical advancements positively affecting mortality of adults with SCD include prophylactic penicillin to prevent pneumococcal infections, preoperative transfusions, multidisciplinary pain management, adrenergic agonist anti-androgen therapy for the treatment and prevention of priapism, and the use of angiotensin-converting enzymes to inhibit proteinurea and subsequently prevent renal disease (Claster & Vichinsky, 2003). Even so, many adults who are currently 45 years of age or older did not have the benefit of these recent advancements in care. For example, it wasn’t until 1995 that a report in the New England Journal of Medicine indicated hydroxyurea was the first agent to prevent complications of sickle cell anemia, such as vaso-occlusive, painful crises and acute chest syndrome (Charache et al., 1995).

Rowland (1998) reported the first umbilical cord transplant for a child with SCD in 1998. She also reported that researchers had cured sickle cell using bone marrow transplants. In these cases, donors were related brothers and sisters. Most of the time, however, even sibling donors are not a good match (Rowland, 1998). Moreover, Guthrie (2001) reported that bone marrow transplants were of limited use for people with SCD because adults and some children could not endure the procedure, Nonetheless, because of advances in modern medicine, people with SCD are living much longer (Lenoci, Telfair, Cecil, & Edwards, 2002; Wojciechowski, Hurtig, & Dorn, 2002). The increasing survival rates associated with SCD warrant the attention of health care providers. They must work toward the provision of optimal health care resources for adults with SCD.

Self-care management resources of adults with SCD who are at least 45 years of age may have played a large part in their longevity, despite the lack of medical advances during their youth. The authors were unable to identify any published studies describing influences on QOL in adults age 45 years or older with SCD. The life expectancy for persons with SCD has increased from 14 years in 1973 to the mid to late 40s in 2004, transforming SCD into a long-term chronic illness (Diggs, 1973; Quinn, Rogers, & Buchanan, 2004). The purpose of this study was 10 explore influences on health outcomes among middle-aged and older adults with SCD.

Life Review

Butler (1963) proposed die concept of life review as a “naturally occurring, universal mental process characterized by the progressive return to consciousness of past experience, and particularly, the resurgence of unresolved conflicts; simultaneously, and normally, these revived experiences and conflicts can be surveyed and reintegrated . . . prompted by the realization of approaching dissolution and death, and the inability to maintain one’s sense of personal invulnerability” (p. 66). Haight (1992) has expanded the process of life review with a structured questionnaire titled, Haight’s Life Review and Experiencing Form (Haight & Burnside, 1992). This interview allows participants to respond in questions about their childhood, adolescence, family and home, adulthood, and overall life.

Although like review has been used with several populations including individuals living with AIDS (Erlen, Mellors, Sereika, & Cook, 2001), individuals who have had a cerebrovascular accident (Davis, 2004), and individuals living with cancer (Ando, Morita, & O’Connor, 2007), it has never been used with a sample of middle-aged and older adults with SCD. Life review has a therapeutic effect on depression, life satisfaction, and self esteem (Bohlmeijer, Smit, & Cuijpers, 2003; Haight, Michel, & Hendrix, 2000; Shellman, 2004). Life review may be an important psychotherapeutic approach to enhance the health outcomes of older adults (Puentes, 2004).

Conceptual Framework

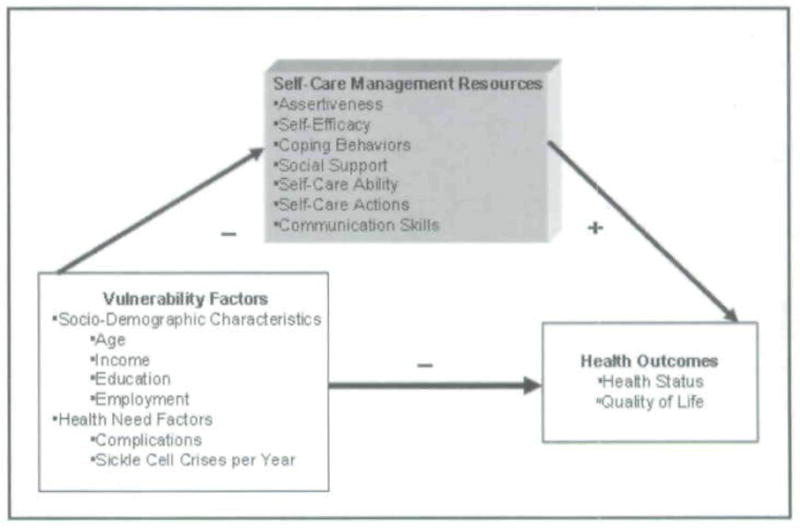

The Theory of Self-Care Management for Sickle Cell Disease (SCMSCD; Figure 1) proposes that a) vulnerability factors (socio-demographic and health-need factors) negatively affect health outcomes (health status and quality of life) and self-care management resources (assertiveness, self-efficacy, coping behaviors, social support, self-care ability, self-care actions, and communication skills) and b) self-care management resources positively mediate the relationship between vulnerability factors and health outcomes. The SCMSCD is based on the Theory of Self-care Management for Vulnerable Populations, a middle range theory developed by the author (CMJ) to describe variables influencing self-care management, health status, and quality of life among populations who experience or are at risk for health disparities Model relationships proposed in the Theory of Self-Care Management for Vulnerable Populations have been supported in prior research with individuals with SCD and other chronic illnesses and published elsewhere (Dorsey, Phillips, & Williams. 2001; Dorsey & Murdaugh, 2003). The SCMSCD was tested with a sample of adults with SCD (Jenerette & Murdaugh, in press). Results partially supported the negative effect of vulnerability factors on health outcomes and self-care management resources and demonstrated a partially positively mediated relationship between vulnerability and health care outcomes.

Figure 1.

Theory of Self-care Management for Sickle Cell Disease

Method

Setting and Participants

The Institutional Review Boards of Yale and Howard Universities approved this pilot study. The study participants were recruited between February 2005 and June 2006 from two urban, outpatient sickle cell clinics in the U.S. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were 45 years or older, able to understand English, and had a diagnosis of SCD.

Clinic staff at each facility identified clients who met the study eligibility criteria. These individuals were recruited via mailings or given the recruitment letter by the clinic nurse during a scheduled clinic appointment. Seven individuals responded to recruitment by contacting the investigators. During the telephone conversation, the prospective participants’ questions were answered. They were told participation in the study would take approximately 1 to 2 hours and could be scheduled at a time that was convenient to them. At the interview appointment, the investigator answered additional questions, and participants provided written, informed consent.

Within the two SCD clinics, there were 22 individuals who met the study criteria. Seven individuals, all females, responded to recruitment efforts, but only six participated in the study. The seventh participant could not participate in the study due to employment and illness.

Data Collection

Each participant was interviewed in person, in a private area, near her respective clinic setting. The authors conducted the interviews. Each participant completed a Demographic and Vulnerability Questionnaire, which was used to obtain data to describe the sample of older adults with SCD and their vulnerability factors. After a participant completed the Demographic and Vulnerability Questionnaire, an interviewer began the semi-structured life review interview using the Successful Aging with SCD Life Review Interview Guide (see Box I). The guide was based on Haight’s Life Review and Experiencing Form (Haight & Burn-side, 1992), but had been adapted for this study using concepts related to SCD and concepts specific to SCMSCD. For example, the first structured statement was, “Tell me about what life was like for you as a child growing up with sickle cell?” Another question was, “On the whole, how would you describe your quality of life or the kind of life that you have had?” The last structured question was, “How have you felt about participating in this life review?”

Box 1. Successful Aging with SCD Life Review Interview Guide.

Tell me about what life was like for you as a child growing up with Sickle Cell. (Do you remember being sick?)

As a teenager with Sickle Cell, tell me about any hardships that you remember. (Do you remember feeling left alone, abandoned, not having enough love or care as a child or adolescent?)

Were you the only child with Sickle Cell in your home? Tell me about the atmosphere in your home. (Do you feel like you were treated differently because you had Sickle Cell? Were your parents/siblings overprotective)

Who were you closest to in your family? Why?

What place did religion play in your life? Do you think this would have been different if you did not have Sickle Cell?

Tell me about your work history as an adult with Sickle Cell, (Do/did you enjoy your work? Are/were you able to earn an adequate living? Do you feel like you work/worked hard in spite of having Sickle Cell? Do/did you feel appreciated?)

-

What were some of the main difficulties you encountered during your adult years?

Did someone close to you die? Go away?

Were you ever sick? Have an accident?

Did you move often? Change jobs?

Did you ever feel atone? Abandoned?

Did you ever feel need?

Resilience can be described as the capacity to withstand a stressor (such as Sickle Cell) despite the potential or actual consequences. Tell me about the role that resilience has played in your life as you have lived with Sickle Cell

On the whole, how would you describe your quality of life or the kind of life that you have had?

If you were going to live your life over again, what would you change? Leave unchanged?

We’ve been talking about your life for quite some time now. Let’s discuss your over-all feelings and ideas about your life. What would you say the main satisfactions in your life have been? (Try for three.) Why have they been satisfying?

Let’s talk a little about you as you are now? What are the best things about the age you are now? Tell me about your present health status?

What do you hope will happen to you as you grow older? Are you hopeful about continuing to grow older with Sickle Cell?

Sickle Cell most often affects Blacks in the United States. Have you ever felt that there were/are limits on your quality of life/success in life because you do have a chronic disease that most often affects Blacks, a minority population? If so, tell me about it.

Tell me about what you think adults with Sickle Cell Disease need to do to best take care of themselves. How did you obtain knowledge/skills to take care of yourself? On a scale from 1–10 with 10 being the most assertive, describe how assertive are you when it comes to getting what you need to care for yourself.

How have you felt about participating in this life review?

Data Transcription and Analysis

The audio-raped interviews were transcribed verbatim and imported into MaxQDA2 format; transcripts were analyzed using the constant comparative method of qualitative data analysis (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Hewitt-Taylor, 2001). In a series of steps, each investigator performed a line-by-line review and coded the transcripts independently. Investigators agreed that major concepts from the SCMSCD would be apriori codes and other codes would emerge from the data. Apriori codes from the SCMSCD were selected because this was the conceptual framework for the study. The apriori codes were only used as a first step in data analysis. After each investigator coded two interviews independently, the two investigators came together in a joint session to review the coding of each transcript. The code structure, which included the apriori codes, emerged during the joint session and was augmented with additional sessions after each investigator had ended all data independently. At the final joint session, all discrepancies were resolved through discussion and negotiation until consensus was reached. The final code structure was applied to each transcript, and common themes were apparent among data provided by all respondents.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Sample

The respondents’ mean age was 54 years old (range 48–64 years). Of the six female respondents, five were African American, and one was Greek American. Three respondents were single, two were separated, and one was married. Only one respondent worked full-time, while three reported unemployment due to disability. Two respondents were retired. Five respondents had sickle cell anemia, the most severe form of the disease, while one respondent had sickle cell hemoglobin C disease. The respondents reported that on average their first SCD crisis occurred at about seven years of age and they were hospitalized three times per year due to SCD. In terms of overall present health, two participants characterized their health as excellent, three claimed good health, and only one described her current health status as fair. The mean quality of life score of the respondents was 50 (SD = 11) on a scale that ranged from 7–70.

Interview Data Analysis

The authors identified three major themes that were consistent with the Theory of Self-Care Management for Sickle Cell Disease. These themes were a) Vulnerability Factors – factors that decreased respondents’ potential to age successfully, b) Self-Care Management Resources – the sources of support that helped respondents manage living with SCD, and c) Health Outcomes – descriptions of how SCD affected the respondents’ health status and quality of life. Themes and subthemes are summarized in Table 1.

Table I.

Themes and subthemes in successful aging with sickle cell disease

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Vulnerability Factors |

|

| Self-Care Management Resources |

|

| Health Outcomes |

|

Vulnerability Factors

The Successful Aging with SCD Life Review Interview Guide uses a chronological approach to life review. For this reason, many of the vulnerability factors’ subthemes expressed by respondents began in childhood. Common subthemes of the vulnerability factors were number of pain crises, overprotection, and limitations.

Painful Crises

Pain, a hallmark of SCD, is most frequently the reason why individuals with SCD seek care. In SCMSCD, the number of SCD crises is a vulnerability factor. Middle-aged and older adults with SCD were experiencing the pain of SCD at a time when there may not have been mandatory screening of all newborns for the disease. Many respondents noted their parents did not know what was wrong with them and often treated them with home remedies. One respondent stated, “As a child I had several crises a year and of course no one had heard of the disease and the doctors were very, very limited on what they knew about it.” Another respondent stated, “My mom and dad would take turns rubbing my legs in alcohol or just by rubbing them until I was 5, when I was diagnosed, but earlier on, they didn’t know what was causing the pain.”

The painful crises of SCD did not stop in childhood but were consistently discussed throughout the life span of these adults with SCD. One respondent summed it up best with her statement, “It was some days you had good days, and then there were days where you just didn’t do anything except lay around because you were in so much pain.”

Respondents spoke about their interactions with healthcare providers during their pain crises as adults. One respondent stated, “When you first come into the ER [emergency room] with crisis, you have to lay [sic] around in there - I guess over a couple of hours before you get medicine.” Another described her fear of becoming a drug addict in relation to being cared for during her pain crises by a physician at a teaching hospital:

Because it was times he [the doctor] said, ‘you know, I really don’t understand either about the drugs that are used, if it’s really helping the people or if it’s not, ‘and I try to bring it to his attention where I feel comfortable enough talking to him, to tell him… But trying to introduce me to these different drugs…I’m scared about some of them because the after effects that you have from them. I just pray that I never become addicted to none of them.

Overprotection

The second vulnerability factor subtheme was overprotection. Overprotection was not conceptualized as a vulnerability factor in SCMSCD prior to this study. In childhood, overprotection often resulted because parents were not knowledgeable about SCD or did not understand aspects of the disease. The respondents frequently described the overprotective activities as demonstrations of love or concern. One respondent stated, “As far as my parents, they were very much protective of me because they didn’t know exactly what could happen when I was young but they tried to keep me away from certain things.”

As respondents reminisced about the role overprotection played in their lives when they were growing up, they saw some of the effects as adults. One said, “So, she [mother] protected me from everything that she could possibly protect me from, but when she died I had to learn to stand on my own two feet and be assertive for myself. So, over protection is not good in some ways, too.” Others stated the way they dress and dress their children is related to how protective their parents were: “As a child, my mother protected me very much, bundled me up all the time, and I seem to do the same thing to my child. I can’t help but tell her to take it sweater with her.” In some instances, overprotection was not viewed as loving; instead, it led to negative thoughts. A respondent confided,

…all my life, I felt like, that my mother didn’t want me to be with my sister and brother. Cause they git to go some where and I couldn’t go. …I was like round her ‘24/7’— close to her. When she was in the kitchen, I was in the front room looking at TV. She always ask me questions: ‘You feeling OK? You feeling better? Is there anything wrong’?

Although she would not describe the behaviors of her parents or family as overprotective, one respondent captured the essence of the potentially harmful effects of overprotection of people with chronic conditions, such as SCD, when she stated, “I wouldn’t say overprotected. I would say not given the opportunity to really challenge my sickle cell.”

Limitations

The third vulnerability factor subtheme was limitations. It is related to the previous two subthemes of pain crises and overprotection. This group of women with SCD faced limitations in childhood and throughout their adult lives. One respondent stated that during her childhood she was told, “You’re handicapped. You’re just a paper bag. Then were a lot of things that I wanted to do, that I couldn’t do.” Other respondents reflected on how they were limited in activities: “As a teenager I basically was by myself because I couldn’t do a lot of the things. My mother wouldn’t let me do a lot of the things that all the other regular teenagers was [sic] doing. So I was pretty much a loner.”

In addition to experiencing psychological effects of limitations imposed by others, respondents spoke about the actual physical limitations of the disease process. A respondent stated, “Sickle cell makes you very tired and everything and plus I have problems sleeping because of the pain.”

Childbearing may also be difficult for women with SCD due to the pathophysiology of the disease. Although five of the six respondents had at least one child, most were discouraged from having children. One respondent stated, “I was discouraged [from childbearing]. As a matter of fact, my doctor—I was 24 when I became pregnant for the first time, The doctor set up a meeting with my whole family and he went as far as saying, if he was my father he would make me have an abortion.”

Self-care Management Resources

Self-care management resources are ways in which these middle-aged and older adults with SCD learned to live with the consequences of SCD on a day-to-day basis. In SCMSCD, self-care management resources are conceptualized as positively mediating the relationship between vulnerability factors and health outcomes. During the life review, it was evident that many of the resources respondents developed were heavily influenced by their parents or other caregivers, and these parental ideals remain important in their lives today. The four self-care management subthemes that emerged were religion/spirituality, social support, assertiveness, and self-care activities. These subthemes are consistent with self-care management resources identified in the SCMSCD.

Religion and Spirituality

Each respondent mentioned aspects of religion/spirituality. All of the of the respondents grew up in church and felt as though their religion/spirituality played an important role in living with SCD—especially during painful crises. One respondent stated, “I think religion played a big part because if there was no one else, you could always talk to God and ask Him to help relieve the pain. So, I’m a pretty religious person.” Another respondent described the role of prayer in dealing with delays in the emergency room:

When you first come into the ER [emergency room] with crisis, you have to lay [sic] around in there—I guess over a couple of hours before you get medicine. But I still deal because I trust in the Lord and so I just wait until whenever they come around. I try not to get myself upset, and I just lay [sic] there and pray and ask God to give me strength and give the doctors strength too to help them take care of me. I keep from getting depressed.

Another respondent described her relationship with God as an important aspect of living with SCD:

With God’s help, I think that’s how I made it through with taking care of my children and the home. I always have believed in praying and asking God for strength. He gave me the strength that I need to go work, take cure of my family up to this present time. So …that’s how I deal with my sickle cell.

Social Support

Social support was the second self-care management sub-theme emerging from the life review interviews. Several respondents specifically noted their mother’s support as an important resource although, in some instances as previously mentioned, overprotective mothers enforced many limits. One respondent stated,

I’ve made it and maybe it’s because I understand sickle cell more than anyone else because it was like what my mother kept at—finding a way to make sure that I knew about things… I thank my mother for taking that time for me to let it be known what to do, how to do, don’t feel bad about it.

Another respondent said, “I can remember being in the hospital and you know and ....it was kinda a lonely kind of place. I was very lucky that my mother was…always there for me.”

When asked what adults with SCD need to better take care of themselves, many respondents spoke about the value of social support. One respondent stated, “They need a good support system. To take care of themselves, they really need someone else who can make sure that when they have a problem that they get the health care that they need.” Many respondents expressed having support from their families but not having access to a peer support group. A respondent stated,

I lived in an area where it [SCD] is not really prevalent or if it is, there is no support group. So, I never really knew anybody with sickle cell disease to talk over my problems and it was pretty difficult because you …you had all. these different issues and nobody really seemed to quite understand because they couldn’t…didn’t have it. So yeah, I think a support group would have been a wonderful experience and helped me more.

Assertiveness

The next subtheme of self-care management resources is assertiveness. It is important for individuals with chronic illness to be able to access the healthcare system and get the care they need. However, for adults with SCD, who may have been limited in opportunities to make self-care decisions, secondary to overprotection, assertiveness may be difficult. One respondent stated, “So, she [mother] protected me from everything that she could possibly protect me from, but when she died I had to learn to stand on my own two feet and be assertive for myself. So, overprotection is not good in some ways.” Another respondent described her assertiveness as a 9.5 on a scale from 1–10 with ten being the most assertive and said, “If I don’t take care of me, ain’t nobody else down here gonna take care of me cause they are too busy trying to take care of themselves.”

Another respondent shared how she assertively communicates her pain management plan with her physician when she stated, “…if its something I feel I can’t handle, I’ll let him know but if it something I feel is working for me, I’ll let him know that also.” She described her desire to only take the drugs that alleviate her pain without side effects. Another respondent noted that although it is important to be assertive in seeking care, it is often difficult for individuals with SCD to be assertive during a painful crisis. She stated that when her pain is at its worst or a 10 on a scale of 0 to 10, “I would never do it [be assertive] because I am in a lot of worse pain. But if I go down to, I would say 3, I begin to feeling better, and then I could be able to speak and let them know [my needs].”

Self-care Activities

The last subtheme of self-care management resources is behavior representing each respondent’s self-care actions. Many of the respondents’ activities were learned from experiences with their caregivers during childhood, while other principles of self-care were learned through the experience of living with SCD as an adult. One respondent stated, “She [mother] would always have me wear sweaters and bring coats when the weather changes and stuff ...... Her awareness had been instilled in me to constantly keep on doing the same thing.” Several respondents talked about the importance of getting rest and eating the proper food. One respondent observed that you have to know your body. She said, “I had to learn my body when it’s telling me I’m too tired. I had to control myself—to listen to my body. That’s why I had to learn my body and figure out what’s triggering the sickle cell.”

Health Outcomes

Health outcomes refer to the respondents’ current health status and quality of life. Three themes that emerged as the respondents talked about their health outcomes were a) living beyond expectations, b) enjoying life satisfactions that are consistent with individuals without a chronic illness, and c) doing well in spite of SCD.

Living beyond Expectations

All of the respondents spoke about hearing that they would not live past a certain age. One respondent stated, “I can’t believe I’m 55 I just can’t believe it because my whole life people told me I wouldn’t live beyond 25, and then it was 35, and then it was 45. So to be 55. I’m just really happy. Every birthday now is a big celebration.” Interactions with healthcare providers often reinforced the outdated notion that the respondents were living beyond expectations. A respondent stated,

I am happy to be this age because a lot of people with sickle cell don’t live to get this age. I know once when I was living in Florida, and I got sick down there, I ended up with some doctor. He was a crazy doctor because he asked me what was I doing living because I was supposed to be dead.

Because many family members and healthcare providers believed that people with SCD would not live long lives, they discouraged respondents from pursuing activities and goals that are part of a satisfying life for most individuals.

Enjoying Life Satisfactions

The next health outcomes subtheme was life satisfactions consistent with people who live without chronic illness. When asked to discuss three major satisfactions in life, having children was the most frequent response. Other life satisfactions included family, marriage, career, and work. Several of the respondents were either told they would never have children or they should not have a child due to potential complications. Children were the life satisfaction most often reported by respondents. One respondent named her daughter as her most important life satisfaction:

The first [life satisfaction] would be that my daughter is still with me. Because of my sickle cell, giving birth to her, needless to say, there were complications with me and then complications with her. I thank God that he let her little heart start back to beating. She is still here and she was born healthy. She has the trait but she really hasn’t had any problems like I had.

Another respondent stated, “I always wanted a child, and I ended up having one. And I promised if I had a boy that would be the only one I would have. …I prayed that he didn’t have sickle cell.”

All respondents described their work outside of the home. The various roles included serving meals in a cafeteria, teaching or counseling children, and volunteering in a hospital. The respondents valued the various opportunities experienced in those career roles. A respondent who enjoyed teaching school-age children believed that facing the challenges of SCD had provided a perspective that enabled her to address the special needs of children: “Sickle cell gives you an empathy that other people might not have especially for kids that had problems. So I used to get a lot of those kids, and I really felt for them I think more than the average teacher would and gave them a start.” Another respondent reported that helping others as a hospital volunteer provided a welcomed diversion from thinking about the pain of SCD: “Sometimes when I’m in a light pain [less severe], I would go to volunteer to get this light pain that I got…to get it out my mind. Because sometimes, it go [sic] away if I do things without thinking about this little light affliction that I got.”

Doing Well

The final health outcomes subtheme was doing well in spite of having sickle cell. One respondent summarized it best with her response. “With SCD, I still feel that I lived a normal life ‘cause I feel like I did what I wanted to do. I was happy with the work I done [sic] and having the children I had. So I just feel like with this disease, I still live a happy life.”

Study Limitations

An initial step in exploring influences on health outcomes with middle-aged or older adults with SCD, this pilot study had limitations. First, the study involved only six respondents from two geographic areas. Second, life review methods were used to collect data; therefore, findings were based entirely on self-report and recall. Third, because this was a first attempt at developing a life review interview specific to SCD, several of the questions may have led participants in a certain direction rather than providing opportunity for various responses. In future studies, it will be important to make sure statements or questions are non-directional and open-ended. Last, the study only described the perspectives of middle-aged or older females with SCD. Older adult males with SCD may have different, important experiences to share.

Discussion

Pain management remains a significant issue for adults with SCD. Currently, adults with SCD who present in emergency departments with complaints of an acute pain crisis may wait an average of 90 minutes for the first analgesic to be given. The delay may be due to the pain of SCD being poorly understood. Additional barriers to adequate pain management include the predominantly African American ethnicity of people with SCD in the U.S., greater potential for lower socioeconomic status, and difficulty in objectively assessing a pain crisis (Ely et al., 2002). When adults with SCD seek treatment for acute pain in an emergency department, there is great potential for racial stereotyping, mistrust, and problematic physician-patient communication (Todd et al., 2006). For this reason, it may be important for individuals with SCD who are experiencing a pain crisis to have both the social support of family and the advocacy of others when entering the healthcare system.

Role of Religion and Spirituality

The findings supported previous research depicting the role of religion and spirituality among people living with SCD and their reliance on “God’s help” (Cooper-Effa, Blount, Kaslow, Rothenberg, & Eckman, 2001; Harrison et al., 2005; Jenerette & Phillips, 2006; Loeb, 2006). Reliance on “God’s help” and the support of their families enabled respondents in this study to manage living with SCD, particularly during their pain. Historically, the church has been a vital source of support when African Americans have encountered stressful events in their lives (Harrison et al., 2001). African Americans with chronic illnesses, like SCD, have described participation in religious activities as a source of support when coping with illness stressors. Church attendance has been correlated with the lowest scores on measures of pain. Perceptions of achieving a greater control of pain have been reported by individuals with SCD who described “higher levels of religiosity” (Cooper-Effa et al, 2001; Harrison et al., 2005, p. 251). Therefore, self-care management resource interventions including spirituality or religiosity may help individuals with SCD respond to their illness-related challenges.

Feelings of Social Isolation

Study findings supported previous research in adults with SCD that feelings of being isolated by their experience of a sickle cell pain crisis and limited social support networks, including friends and family, adversely affects pain management (Chen, Cole, & Kato, 2004; Nash, 1994; Smith-Fawzi et al., 2005). Due to often unpredictable pain crises, adults with SCD may have decreased work productivity, missed work, and school absences that significantly impair their social support network and quality of life (Todd et al., 2006). Social isolation may lead to limited peer interactions. Therefore, some adults with SCD may lack experience with problem resolution skills which can lead to social withdrawal and further exacerbation of poor peer relations (Edwards et al., 2005). Older adults with SCD are particularly vulnerable to social isolation because of the increased numbers of complications related to SCD.

Experience of Not Being Heard

Some respondents in the current study described the void existing when they did not have opportunities to express their concerns to other adults with SCD. This finding supports the observations of previous researchers that feelings of isolation may lead to maladaptive coping behaviors in adults with SCD (Booker et al., 2006). For example, Anie (2005) found that adults with SCD commonly report low self-esteem and feelings of hopelessness as a result of frequent pain, hospitalizations and subsequent loss of employment. An adult with SCD said, “It’s devastating for a person to be in pain but not to be believed. It makes you feel less than human. The trust is broken when the person you come to for help reacts negatively” (Schreiber, 2000, p.25). The psychological disturbances, such as depression and anxiety, are often associated with a diminished ability to cope with pain and further perpetuate the cycle of pain intensity with significant impact on health outcomes (Edwards et al., 2005). Establishing social support groups and making referrals to support groups within SCD communities may be important interventions for individuals with SCD whose stories are not heard.

Benefits of Assertiveness and Pro-action

The self-care management activities of individuals with SCD may increase when they are taught how to effectively communicate their perspectives about pain relief measures to health care providers. Adults with SCD often present at a time when pain is so acute they cannot clearly and assertively articulate their subjective evidence of an imminent crisis. Because requests for pain relief are urgent, healthcare providers may stereotype and stigmatize adult patients with SCD as addicts. In order for individuals with SCD to seek care earlier, it is important for them to recognize the prodromal phase of an evolving SCD crisis, characterized as a period before the onset of severe pain that lasts an average of 2–4 days with pain that has been described as low intensity or aches (Ballas, 1995; Jacobs et al., 2005). By recognizing early symptoms and presenting for care before they progress to an acute painful crisis, adults with SCD may be better able to communicate information about pain management strategies and other wellness activities. These pro-actions may increase health care providers’ understanding of how individuals with SCD manage their lives with SCD. Pro-action is consistent with benefits of assertive communication skills promoted in previous studies (Atkin & Ahmad, 2001; Richardson, 2000).

Satisfaction of Having Children

Study findings suggested that life satisfactions of adults with SCD do not differ from the life satisfactions or their peers without a chronic illness. Health care providers need to be aware that females with SCD may want to have children. Therefore, health care providers should support adults with SCD who want to make informed choices about childbearing. Although there are differing opinions about childbearing in adults with SCD, research supports that the desire to have a child often outweighs the potential of experiencing complications or having a child with SCD (Neal-Cooper & Scott, 1988).

Implications for Clinical Practice

Life review interviews with middle-aged or older adults with SCD revealed information to help nurses develop interventions for families with children, adolescents, and adults with SCD. For example, the respondents in this study remembered waiting for long periods of time in the emergency room to receive treatment for pain. Studies suggest that individuals with SCD and their families most often manage SCD pain at home and try to avoid going to the emergency department (Beyer, Simmons, Woods, & Woods, 1999; Booker et al., 2006; Porter et al., 1998). In some instances, avoidance of emergency care may result in individuals with SCD remaining at home too long. Nurses can teach adults with SCD and caregivers of children and adolescents with SCD how to monitor the pain of SCD and decide when it is appropriate to seek health care. Interventions should include age-appropriate instructions to help school-age children and adolescents learn how to assess their pain and communicate whether comfort measures given at home are helping to relieve it.

Effective interventions must address disparities that exist in the client’s access to quality care (Sullivan-Bolyai, Bova, & Harper, 2005). Interventions to enhance children’s, adolescents’, and adults’ abilities to communicate their needs for pain relief to health care providers will be incomplete without educating health care providers about managing the pain of SCD. Some studies have suggested that nurses and physicians lack knowledge about effectively managing pain for clients with SCD (Pack-Mabien, Labbe, Herbert, & Haynes, 2001; Shapiro, Benjamin, Payne, & Heidrich, 1997). Nursing and medical education should emphasize the importance of assessing children’s, adolescents’, and adults’ perceptions of their pain and their knowledge of care regimens that effectively relieve it. Educators in the health professions can inform students that clients with SCD manage much of their pain at home and come to the emergency room or clinic with a knowledge of strategies that have or have not provided relief (Fletcher & Hayes, 2000; Maikler, Broome, Bailey, & Lea, 2001). Client education should encourage participation in care and development decision-making skills.

Studies suggest that exposure to cold temperatures may trigger the pain crises (Mohan et al., 1998; Serjeant et al., 1994; Smith, Coyne, Smith, & Mercier, 2003). In the current study, respondents remembered their caregivers’ concerns about wearing warm clothes in cold weather, and as adults many still implement familiar self-care management strategies, such as always carrying a sweater. Wearing warm clothes to prevent crises is an important self-care management intervention for individuals with SCD. Caregivers and healthcare providers need to teach and reinforce appropriate dress that protects children and adolescents with SCD from exposure to cooler temperatures.

Children and adolescents with SCD may desire to “challenge sickle cell.” They may participate in extracurricular activities, such as basketball and cheerleading, to determine how much physical exertion can be tolerated and to identify with their peers. This information can be included in the anticipatory guidance that health care providers give to caregivers of children and adolescents with SCD. Caregivers need support in order to reduce caregiver burden associated with caring for a child or adolescent with SCD (Moskowitz et al., 2007) and encouragement to assess behaviors indicating the level of activities in which a child or adolescent can safely participate.

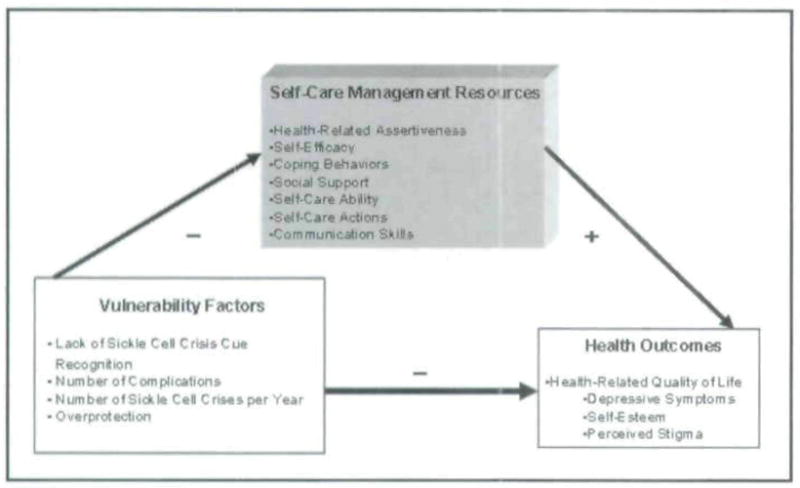

Revisions to the Model

Based on findings from this study, the Theory of Self-care Management has been revised to include additional factors (Figure 2). The revised model no longer includes socio-demographic factors because they are less amenable to change. Instead, the revised model now includes SCD specific vulnerability factors such as overprotection and lack of SCD crisis cue recognition. Enhancing cue recognition may lead to increased care-seeking during the prodromal or pre-crisis phase of a SCD pain event.

Figure 2.

Revised Model of Self-care Management for Sickle Cell Disease

The self-care management resources in the model changed slightly. Assertiveness was changed to health-related assertiveness. Participants’ responses indicate that they may assertive in most situations, but during a time of a painful crisis, they do not possess the energy or ability to be assertive. If people living with SCD can be educated to enhance health-related assertive communication skills, however, they may better be able to advocate for their own needs.

Health outcomes were modified in the revised model. Health status was removed while the concept of health-related quality of life was expanded to reflect the literature and responses from participants. Health-related quality of life includes depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and perceived stigma. The revised model needs to be evaluated in future studies with both females and males with SCD.

Implications for Future Studies

Study respondents stated they enjoyed the life review interview. Therefore, it may be a useful way to gain insight into successful aging with SCD and other chronic illnesses. Future studies can explore overprotection as a vulnerability factor negatively influencing health outcomes in people with chronic diseases, such as SCD, It will also be important to investigate cue recognition of prodromal symptoms in sickle cell crisis, client’s communication skills, and whether general assertiveness or health-related assertiveness training would he more beneficial to adults with SCD. Although both females and males with SCD face multiple challenges, they face different challenges. It would be useful to repeat this study with a sample of middle-aged and older males with SCD to provide specific feedback for developing appropriate, theory-based interventions for males with SCD.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study participants who shared how they successfully aged while living with SCD and the staff of the Yale-New Haven Hospital Adult Sickle Cell Program and the Howard University Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center. We appreciate the valuable contributions of our research assistant Elizabeth Olumese, MSN, RN. This study was funded by the Yale-Howard Partnership Center for Reducing Health Disparities by Self and Family Management (P20NR08349-04). Coretta M. Jenerette, PhD, RN, was a postdoctoral fellow at Yale University School of Nursing, New Haven, CT when this research was conducted.

Footnotes

Author’s Note: Some data in this article were previously presented in a poster format at the Yale Bouchet Conference on Diversity in Graduate Education in New Haven, CT (April 2006) and in a podium presentation at the M. Elizabeth Carnegie Endowed Professorship in Nursing Research 13th Annual Conference in Washington, DC (March 2007).

Contributor Information

Coretta M. Jenerette, Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Nursing, 4008 Carrington Hall, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7460. She can be contacted at coretta.jenerette@unc.edu.

Gloria Lauderdale, Assistant Professor in the Division of Nursing, College of Pharmacy, Nursing and Allied Health Sciences at Howard University, 501 Bryant Street, NW, Annex II, Washington, D.C. 20059.

References

- Ando M, Morita T, O’Connor SJ. Primary concerns of advanced cancer patients identified through the structural life review process: A qualitative study using a text mining technique. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2007;5(3):265–271. doi: 10.1017/s1478951507000430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews MM, Mooney KH. Alterations in hematologic function in children. In: McCance KL, Huether SE, editors. Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in children. St. Louis: Mosby-Yearbook; 1994. pp. 908–939. [Google Scholar]

- Anie KA. Psychological complications in sickle cell disease. British Journal of Haematology. 2005;129(6):723–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin K, Ahmad WI. Living a ‘normal’ life: Young people coping with thalassaemia major or sickle cell disorder. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;53(5):615–626. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballas SK. The sickle cell painful crisis in adults: Phases and objective signs. Hemoglobin. 1995;19(6):323–333. doi: 10.3109/03630269509005824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballas SK. Complications of sickle cell anemia in adults: Guidelines for effective management. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 1999;66(1):48–58. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.66.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballas SK. Pain management of sickle cell disease. Hematology/oncology Clinics of North America. 2005;19(5):785–802. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer JE, Simmonds LE, Woods GM, Woods PM. A chronology of pain and comfort in children with sickle cell disease. Archives of pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 1999;153:913–920. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.9.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmeijer E, Smit F, Cuijpers P. Effects of reminiscence and life review on late-life depression: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003;18(12):1088–1094. doi: 10.1002/gps.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolten W, Kempel-Waibel A, Pforringer W. Analysis of the cost of illness in backache. Medizinische Klinik (Munich, Germany) 1998;93:388–393. doi: 10.1007/BF03044686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker MJ, Blethyn KL, Wright CJ, Greenfield SM. Pain management in sickle cell disease. Chronic Illness. 2006;2(1):39–50. doi: 10.1177/17423953060020011101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler RN. The life review: An interpretation of reminiscence in the aged. Psychiatry. 1963;26:65–76. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1963.11023339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charache S, Terrin MI, Moore RD, Dover GJ, Barton FB, Eckert SV, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crisis in sickle cell anemia. Investigators of the multicenter study of hydroxyurea in sickle cell anemia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;332(20):1317–1322. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Cole SW, Kato PM. A review of empirically supported psychosocial interventions for pain and adherence outcomes in sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2004;29(3):197–209. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claster S, Vinchinsky EP. Managing sickle cell disease. British Medical Journal. 2003;327(7424):1151–1156. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7424.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Effa M, Blount W, Kaslow N, Rothenberg R, Eckman J. Role of spirituality in patients with sickle cell disease. Journal of American Board of family Practice. 2001;14:116–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Commentary … chronic illness trajectory model. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing practice. 1991;5(3):243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Davis MC. Life review therapy as an intervention to manage depression and enhance life satisfaction in individuals with right hemisphere cerebral vascular accidents. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2004;25(5):503–515. doi: 10.1080/01612840490443455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggs LM. Anatomic lesions in sickle cell disease. In: Abramson H, Bertles JF, Wethers DL, editors. Sickle cell disease: Diagnosis, management, education, and research. St. Louis: C. V. Mosby; 1973. pp. 189–229. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey C, Phillips K, Williams C. Adult sickle cell patients’ perceptions of nurses’ caring behaviors. The Association of Black Nursing Faculty Journal. 2001;12(5):95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey CJ, Murdaugh CL. The theory of self-care management for vulnerable populations. The journal of Theory Construction and Testing. 2003;7(2):43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher C, Hayes JS. Practice applications of research. Appraisal and coping with vaso-occlusive crisis in adolescents with sickle cell disease. Pediatric Nursing. 2000;26(3):319–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards CL, Scales MT, Loughlin C, Bennett GG, Harris-Peterson S, Castro LM, et al. A brief review of the pathophysiology, associated pain, and psychosocial issues in sickle cell disease. International Journal of Behavioural Medicine. 2005;12(3):171–179. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1203_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely B, Dampier C, Gilday M, O’Neal P, Brodecki D. Caregiver report of pain in infants and toddlers with sickle cell disease: Reliability and validity of a daily diary. The Journal of Pain. 2002;3(1):50–57. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2002.xb30064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlen JA, Mellors MP, Sereika SM, Cook C. The use of life-review to enhance quality of life of people living with AIDS: A feasibility study. Quality of Life Research. 2001;10(5):453–464. doi: 10.1023/a:1012583931564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gordeau B, Noel V, Habibi A, Schaeffer A, Bachir D, Galacteros F. Sickle cell disease in adults: Which emergency care by the internists? Review of Internal Medicine. 2001;22(5):440–451. doi: 10.1016/s0248-8663(01)00369-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman K. Sickle cell disease: Do you doubt your patients’ pain? American Journal of Nursing. 1999;99(3):38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie P. ‘Gentler’ treatment for sickle cell hailed. Atlanta Journal Constitution. 2001 October 26;:E1. [Google Scholar]

- Haight BK, Burnside I. Reminiscence and life review: Conducting the processes. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 1992;18(2):39–42. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19920701-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haight BK, Michel Y, Hendrix S. The extended effects of the life review in nursing home residents. Intenational Journal of Aging & Human Development. 2000;50(2):151–168. doi: 10.2190/QU66-E8UV-NYMR-Y99E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison MO, Edward C, Koenig HG, Bosworth HB, Decastro L, Wood M. Religiosity/spirituality and pain in patients with sickle cell disease. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2005;193(4):250–257. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000158375.73779.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt-Taylor J. Use of constant comparative analysis in qualitative research. Nursing Standard. 2001;15(42):39–42. doi: 10.7748/ns2001.07.15.42.39.c3052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob EJE, Beyer C, Miaskowski M, Savedra M, Treadwell, Styles L. Are there phases to the vaso-occlusive painful episode in sickle cell disease? Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2005;29(4):392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenerette C, Murdaugh C. Testing the theory of self-care management for sickle cell disease. Research in Nursing and Health. doi: 10.1002/nur.20261. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenerette CM, Phillips RCS. An examination of differences in intra-personal resources, self-care management, and health outcomes in older and younger adults with sickle cell disease. Southern Online journal of Nursing Research. 2006;7(3):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jenerette C, Funk M, Murdaugh C. Sickle cell disease: A stigmatizing condition that may lead to depression. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2005;26(10):1081–1101. doi: 10.1080/01612840500280745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenoci JM, Telfair J, Cecil H, Edwards RR. Self-care in adults with sickle cell disease. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2002;24(3):228–245. doi: 10.1177/01939450222045879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb SJ. African American older adults coping with chronic health conditions. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2006;17(2):139–147. doi: 10.1177/1043659605285415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maikler VE, Broome ME, Bailey P, Lea G. Children’s and adolescents’ use of diaries for sickle cell for sickle cell pain. Journal of the Society of Pediatric Nurses. 2001;6(4):161–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2001.tb00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell KS, Streetly A. Living with sickle cell pain. Nursing Standard. 1998;13(9):33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan J, Marshall JM, Reid HL, Thomas PW, Hambleton I, Serjeant GR. Peripheral vascular response in mild indirect cooling in patients with homozygous sickle cell (SS) disease and the frequency of painful crisis. Clinical Science. 1998;94(2):111–120. doi: 10.1042/cs0940111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz JT, Butensky E, Harmatz P, Vichinsky E, Heyman MB, Acree M, et al. Caregiving time in sickle cell disease: Psychological effects in maternal caregivers. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2007;48:64–71. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash KB. Psychological aspects of sickle cell disease: Past, present, and future directions of research. New York: Haworth; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Neal-Cooper F, Scott RB. Genetic counseling in sickle cell anemia: Experiences with couples at risk. Public Health Reports (Washington, DC) 1998;103(2):174–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman L, Calder G, Robertson R, Friend JA, Legge JS, Douglas JG. Symptoms, quality of life, and health service contact among young adults with mild asthma. American journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. 2000;161(2 Pt 1):498–503. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9904063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pack-Mabien A, Labbe E, Herbert D, Haynes J. Nurses’ attitudes and practices in sickle cell pain management. Applied Nursing Research. 2001;14(4):187–192. doi: 10.1053/apnr.2001.26783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter LS, Gil KM, Sedway JA, Ready J, Workman E, Thompson RJ., Jr Pain and stress in sickle cell disease: An analysis of daily pain records. International Journal of Behavioural Medicine. 1998;5(3):185–203. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0503_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puentes WJ. Cognitive therapy integrated with life review techniques: An eclectic treatment approach for affective symptoms in older adults. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2004;13:84–89. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, Buchanan GR. Survival of the children with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2004;103:4023–4027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed W, Vichinsky EP. New considerations in the treatment of sickle cell disease. Annual Review of Medicine. 1998;49:461–474. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson SS. The effect of an assertiveness training intervention on clients’ level of assertiveness, locus of control, and ways of coping with serious illness. Louisiana State University Medical Center; 2000. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland R. Boy receives first cord blood transplant for sickle cell anemia. 1998 Retrieved June 1, 2007, from http://www.cnn.com/HEALTH/9812/14/cord.blood.sickle.cell/

- Schreiber C. Redefining pain: New guidelines challenge misconception about sickle cell disease. Nurse Week. 2000;13(2):25–25. [Google Scholar]

- Serjeant GR, Ceulaer CD, Lethbridge R, Morris J, Singhal A, Thomas PW. The painful crisis of homozygous sickle cell disease: Clinical features. British Journal of Haematology. 1994;87(3):586–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb08317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro BS, Benjamin LJ, Payne R, Heidrich G. Sickle cell-related pain: Perceptions of medical practitioners. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 1997;14:168–174. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(97)00019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shellman J. “Nobody ever asked me before”: Understanding life experiences of African American elders. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2004;15(4):308–316. doi: 10.1177/1043659604268961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WR, Bovbjerg VE, Penberthy LT, McClish DK, Levenson JL, Roberts JD, et al. Understanding pain and improving management of sickle cell disease: The PiSCES study. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97(2):183–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WR, Coyne P, Smith VS, Mercier B. Temperature changes, temperature extremes, and their relationship to emergency department visits and hospitalizations for sickle cell crisis. Pain Management Nursing. 2003;4(3):106–111. doi: 10.1016/s1524-9042(02)54211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Fawzi MC, Lambert W, Singler JM, Tanagho Y, Leandre E, Nevil P, et al. Factors associated with forced sex among women accessing health services in rural Haiti: Implications for the prevention of HIV infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60(4):679–689. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland O, Jackson G, Gilead M, McGuire DB, Quarles S. Use of focus groups for pain and quality of life assessment in adults with sickle cell disease. Journal of the National Black Nurses Association. 2001;12(2):36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan-Bolyai S, Bova C, Harper D. Developing and refining interventions in persons with health disparities: The use of qualitative description. Nursing Outlook. 2005;53:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd KH, Green C, Bonham VL, Jr, Haywood C, Jr, Ivy E. Sickle cell disease related pain: Crisis and conflict. Journal of Pain. 2006;7(7):453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins K, Connell CM, Fitzgerald JT, Klem L, Hickey T, Ingersoll-Dayton B. Effect of adults’ self-regulation of diabetes on quality of life. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(10):1511–1515. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.10.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RE, Krishnamurti L, Kamat D. Management of sickle cell disease in primary care. Clinical Pediatrics. 2003;42(9):753–761. doi: 10.1177/000992280304200901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SM, Miles MS. Spirituality in African-American mothers coping with a seriously ill infant. Journal of the Society of Pediatric Nurses. 2001;6(3):116–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2001.tb00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowski EA, Hurtig A, Dorn L. A natural history study of adolescents and young adults with sickle cell disease as they transfer to adult care: A need for case management services. Journal of Peditric Nursing. 2002;17:18–27. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2002.30930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YM, Shah AK, Watson M, Mankad VN. Comparison of costs to the health sector of comprehensive and episodic health care for sickle cell disease patients. Public Health Reports. 1995;110:80–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]