Abstract

Background

For patients with cancer who are married or in an intimate relationship, their relationships with their partners play a critical role in their adaptation to their illness. However, cancer patients and their partners often have difficulty in talking with each other about their cancer-related concerns. Difficulties in communication may ultimately compromise both the patient-partner relationship and the patient's psychological adjustment. The present study tested the efficacy of a novel partner-assisted emotional disclosure intervention in a sample of patients with gastrointestinal (GI) cancer.

Methods

130 patients with GI cancer and their partners were randomly assigned to receive four sessions of either partner-assisted emotional disclosure or a couples cancer education/support intervention. Patients and partners completed measures of relationship quality, intimacy with their partner, and psychological distress before randomization and at the end of the intervention sessions. Data were analyzed using multilevel modeling.

Results

Compared to an education/support condition, the partner-assisted emotional disclosure condition led to improvements in relationship quality and intimacy for couples in which the patient initially reported higher levels of holding back from discussing cancer-related concerns.

Conclusions

Partner-assisted emotional disclosure is a novel intervention that builds on both the private emotional disclosure and the cognitive-behavioral marital literature. The results of this study suggest that this intervention may be beneficial for couples in which the patient tends to hold back from discussing concerns. Future research on methods of enhancing the effects of partner-assisted emotional disclosure is warranted.

Keywords: gastrointestinal cancer, disclosure, couples, psychosocial intervention

For patients with cancer who are married or in an intimate relationship, the relationship with their partner plays a critical role in adapting to their illness.1–3 Both patients and partners often perceive social support and family functioning to diminish in the year following a cancer diagnosis,3–5 suggesting that some couples may be at risk of relationship distress as a result of the burdens imposed by the cancer experience. One factor that may lead to deteriorations in patient-partner relationships is the challenge of communicating effectively about cancer-related concerns. Married cancer patients tend to rate their spouses as their most important confidant,6, 7 however, cancer patients often feel constrained in talking about their concerns with their partners, and partners often withdraw or distance themselves from the patient's emotional distress.2, 6, 8–10 These avoidant patterns are present even in even in relationships that are satisfying.11

Patients' inability to talk openly with their partners about their cancer-related concerns may ultimately compromise the quality of the patient-partner relationship as well as the patient's psychological adjustment Emotional disclosure – defined as the expression of information that is personal, private, and emotional in nature12 – is a central component of the emotional support (e.g. love, concern, and understanding) that partners provide to each other.13, 14 The construct of emotional disclosure has been operationalized as both (a) the degree to which individuals express their thoughts and feelings, and (b) the degree to which they hold back from doing so. While expression and holding back may be seen as opposites of each other, they are in fact only moderately negatively correlated (e.g., −.3215 to −.3816), suggesting that they may represent orthogonal constructs. Holding back may reflect active inhibition of expression rather than a general tendency towards inexpression. Prior studies suggest that high levels of holding back, more so than low levels of expression, are significantly associated with poorer relationship functioning and increased psychological distress.16, 7 To date, however, all of the studies in this area have been correlational, thus it is not possible to draw causal conclusions about the effects of disclosure or holding back.

A number of studies, including several studies conducted with cancer patients,17–20 have shown that expressive writing protocols can produce improvements in psychological and physical well-being (e.g., improved affect, decreased psychological distress and self-reported symptoms).21, 22 In these protocols, participants typically write for 15–20 minutes over several sessions about their deepest thoughts and feelings regarding stressful experiences. In this paradigm, disclosure is private and anonymous; participants are alone when they disclose and their disclosures are not shared with anyone other than the researchers. When applied to patients with cancer, this intervention has been found to lead to improved sleep and vigor in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer17 and to significant reductions in physical symptoms and medical appointments among patients with breast cancer.18

In a separate tradition, increasing emotional disclosure between spouses is often a focus of cognitive-behavioral couple therapy23, 24 A large body of empirical literature demonstrates that in a variety of settings, cognitive-behavioral interventions for couples can significantly improve both individual adjustment and relationship functioning.25 Cognitive-behavioral couple interventions focus specifically on learning relationship skills such as communication. Increases in emotional disclosure that occur during the course of cognitive-behavioral couples therapy have been linked to enhanced intimacy and marital satisfaction.26 However, to our knowledge, the potential benefits of facilitating disclosure regarding cancer-related issues between cancer patients and their partners have not been addressed.

There are several reasons why increasing emotional disclosure between cancer patients and their partners is likely to lead to benefits for couples' relationships. First, as noted above, increasing emotional disclosure may lead to increases in intimacy and relationship satisfaction.27 Second, helping couples to discuss their cancer-related concerns may help partners have a better understanding of patients' needs, and to provide more effective support. In addition, it is possible that patients may derive the same individual psychological benefits from disclosure to their partner as they do from private emotional disclosure protocols. Finally, partners may benefit from hearing the patients talk openly about their concerns. Often a partner senses when the patient has concerns and is not expressing them, and this can lead to increase distress for the partner; when the patient shares his/her concerns, the partner may experience this as a relief.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of a new partner-assisted emotional disclosure protocol for patients with GI cancer. GI cancers make a particularly good model in which to study the effects of this protocol for several reasons. First, they are common, with colorectal cancers being the third leading site of cancer occurrence and cancer mortality for both men and women. 28 Second, they are often discovered at advanced stages when the prognosis for survival is poor. 28, 29 While treatments have been shown to improve survival, tumor control, and quality of life due to relief of tumor-related symptoms, these treatments are often associated with significant toxicities. Patients report multiple disease and treatment-related side effects including fatigue, pain, difficulty eating, weight loss, problems with bowel function, and sexual problems.29–32 Many patients also experience significant emotional distress including disturbances in body image, anxiety and worry, depression, and fears of disease progression and death.3, 29–32 Thus, the diagnosis and treatment of GI cancer poses numerous physical and psychological challenges for patients as well as their loved ones.

The partner-assisted emotional disclosure intervention was designed to systematically train patients and partners in strategies to facilitate the patients' disclosure and give the patient the opportunity to talk about their cancer-related concerns to their partner. We hypothesized that the intervention would lead to improvements in relationship quality, intimacy, and psychological distress for patients and their partners relative to an attention control condition. In addition, we conducted exploratory analyses examining whether intervention effects differed by gender or by the degree to which patients reported holding back from disclosing cancer-related concerns to their spouse at baseline.

Method

Participants

Eligible participants were (a) individuals diagnosed with GI cancer, Stages 2–4, with a life expectancy of at least 6 months, and (b) their spouses or intimate partners. Patients were recruited from the GI oncology clinics at Duke University and University of North Carolina Hospitals. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Duke University Medical Center and University of North Carolina School of Medicine, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

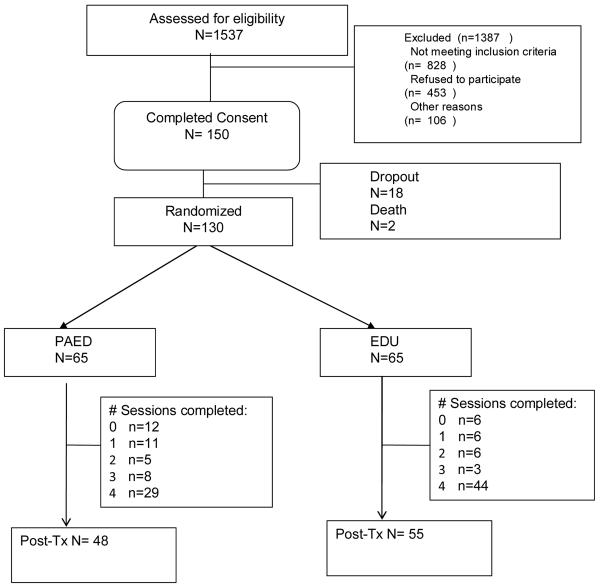

A total of 603 patients were screened for the study, deemed eligible, and approached regarding participation (for CONSORT diagram see Figure 1). Of these patients, 150 (25%) expressed willingness to participate and their partners also agreed to take part. The most common reasons for refusal were that the patient lived at a distance from the medical center and was not willing to travel for the sessions (n=112), the patient and/or partner were not interested (n=95) or felt the study would be too time-consuming (n=24), and that the patient was too ill to participate (n=18).

Figure 1.

CONSORT flowchart.

Of the 150 patients who consented, 20 withdrew prior to randomization. Reasons for withdrawal included death/declining health (n=9), lack of time (n=6), distance (n=3), and lost to contact (n=2). This resulted in 130 couples who were included in the current analyses.

Procedures

After completing informed consent, participants in the study were administered pretreatment measures and were then randomly assigned to one of the two conditions: Partner-Assisted emotional disclosure or Education/Support. The treatment conditions are described below. Randomization was stratified by patient sex and cancer stage (2 and 3 versus 4). After completing the intervention, participants in both conditions completed post-treatment measures. All evaluations were completed by telephone interviews conducted by a research assistant who was blind to the participant's treatment condition. Each participant (patient and partner) was reimbursed $40 ($20 for each of the two evaluations).

Measures

The following measures were completed by both patients and partners:

Relationship quality was assessed using the Quality of Marriage Index (QMI).33 The QMI is a 6-item inventory that assesses relationship satisfaction using broadly worded, global items. Participants indicate whether they agree with each item on a 0–10 scale where 0 means “very strongly disagree” and 10 means “very strongly agree”. Sample items include “My relationship with my partner makes me happy” and “I really feel like part of a team with my partner.” The QMI has demonstrated good reliability and validity, correlating highly with longer, well-validated measures of marital adjustment such as the Dyadic Adjustment Scale.33, 34 Cronbach's alpha in the current study was .92 for patients and .89 for partners.

Intimacy with the partner was assessed using the Miller Social Intimacy Scale (MSIS).35 The MSIS is a 17 item self-report inventory that assesses the degree of intimacy, closeness, and trust that an individual feels in a relationship toward his or her partner. Sample items include “How close do you feel to your partner most of the time?” and “When you have leisure time, how often do you choose to spend it with your partner alone?” There is good evidence that the measure discriminates close from casual friends and happily married from distressed couples, and the MSIS can detect clinically meaningful change following psychological treatment.35, 36 Cronbach's alpha in the current study was .92 for patients and .88 for partners.

Psychological distress was assessed using the Profile of Mood States-Short Form (POMS-SF).37 This measure asks participants to describe their mood over the past week by rating each of thirty adjectives on a scale from 0=very much unlike this to 3=very much like this. There are six subscales (anxiety, depression, anger, vigor, fatigue, and confusion), as well as a Total Mood Disturbance (TMD) scale. The POMS has good temporal stability, excellent internal consistency, and good convergent validity with other measures of psychological distress. The POMS is often used in cancer research studies and has been found to be sensitive to improvements following psychological interventions in cancer patients.38, 39 In the current study, Cronbach's alphas for the subscales ranged from .74 to .93 for both patients and partners; Cronbach's alpha for the TMD was .88 for patients and .90 for partners.

Holding back

Holding back from disclosure of cancer-related thoughts and feelings was assessed using a modified version of a measure developed by Pistrang and Barker.15 The measure consists of ten items that assess the extent to which patients talk about their cancer-related feelings and concerns to their spouse, and how much they hold back from doing so on a scale of 0 (“not at all”) to 5 (“a lot”). Only the holding back scale was used in the current study. In previous studies of patients with GI cancer16 and breast cancer7, 15, high levels of holding back were significantly associated with increased psychological distress and poorer relationship functioning. Cronbach's alpha in the current study was .88.

Partner-Assisted Emotional Disclosure Intervention

The partner-assisted emotional disclosure (emotional disclosure) protocol was designed to train couples systematically in skills designed to help patients disclose their feelings and concerns related to the cancer experience. Couples attended four face-to-face sessions with a master's level therapist (social worker or psychologist). The first session lasted approximately 75 minutes and Sessions 2–4 lasted 45 minutes each. Whereas it was intended that sessions be scheduled weekly, couples were given up to eight weeks to complete the four sessions in order to accommodate delays due to the patient's medical condition and/or to coordinate sessions with other appointments at the medical center. In the first session, the therapist provided a rationale for the intervention and trained the couple in skills designed to help the patient disclose his/her concerns related to the cancer experience. Patients' guidelines for disclosure including (a) thinking about an experience related to having cancer that caused strong emotions; (b) telling their partner about the experience in as much detail as possible, including both the events and feelings related to the experience; and (c) pausing periodically to give their partner the opportunity to respond (e.g., talking in paragraphs). The partners' role was that of supporter. Their guidelines included (a) trying to put themselves in the patient's place and understand what the experience was like for him/her; (b) avoiding problem-solving, reassurance, or advice giving; and (c) reflective listening (e.g., summarizing what the patient said). Training included both didactic and experiential components and was summarized in handouts given to the couples.The therapist helped the couple identify partner responses that the patient found helpful and unhelpful and assisted patients in generating a list of cancer-related topics to focus on in their disclosure sessions. Partners were instructed to keep the focus of the conversation primarily on the patient's experience, and disclose their own thoughts and feelings only as necessary to facilitate the patient's disclosure. (This continued primary focus on the patient's thoughts and feelings distinguishes the intervention for other couple-based interventions such as cognitive-behavioral couple therapy which places a bilateral focus on both people's thoughts and feelings shared reciprocally during a conversation24).

In the subsequent three sessions, the therapist first presented a brief review of the strategies taught in the first session. The patient was then provided with an opportunity to talk about his/her feelings and concerns about the cancer experience. The couple was instructed that their goal was for the patient to focus on the expression of his/her feelings and concerns related to the cancer experience, and for the partner to utilize the skills learned in the initial session to facilitate disclosure as well as to communicate acceptance and understanding. During the disclosure, the therapist intervened only as necessary to: (a) discourage negative interactions, (b) stimulate disclosure using the concern list generated by the patient in the first session, and (c) ensure that the couple's discussion focused primarily on the patient's experience rather than the partner's. Couples were encouraged to continue these conversations on their own outside of sessions, however they were not given specific home practice assignments.

Cancer Education/Support Couple Condition

In order to hold constant the focus on the couple and cancer during intervention, couples in the cancer education/support condition also attended four face-to-face sessions. The therapists and the scheduling of the sessions were the same as that for the partner-assisted emotional disclosure intervention. The education/support sessions centered on presenting information relevant to living with cancer and were supplemented with handouts. The sessions focused on the following topics: Orientation to the cancer center and the treatment team; suggestions for communicating with health care providers; resources for health information, psychosocial support, and financial concerns; evaluating health information on the internet; the impact of cancer on different domains of quality of life; and suggestions for maintaining quality of life. Patients and partners in the education/support condition did not receive any training in communication skills and patients were not encouraged to discuss their thoughts and feelings related to the cancer experience with their partner.

Uniformity of Treatment

Several steps were taken to ensure that the treatment protocols were uniform and that the therapists followed the treatment protocols in a uniform manner. These included therapist training, use of detailed treatment outlines, audiotaping of sessions and therapist supervision, and assessments of treatment adherence and therapist competence.

Data Analyses

Multilevel modeling for dyadic data40, 41 was used to test group differences over time and whether these varied for patients versus partners. Multilevel modeling has a number of advantages over traditional analytic techniques such as repeated measures ANOVA in that it allows for unbalanced data in terms of number and timing of data points, accommodates both time-varying and time-invariant covariates, and are able to account for the fact that data from one member of a couple is influenced by data from the other member of that couple.41

Age, time since diagnosis, and cancer stage were centered and then entered first into the model as covariates. Main effects included in the model were time (pre versus post), treatment condition (partner-assisted emotional disclosure versus education/support), and social role (patient versus partner). Interactions effects included in the model were time X treatment, and time X treatment X role. A significant intervention effect is indicated by a significant two-way interaction between treatment (partner-assisted emotional disclosure versus education/support) and time. A significant three-way interaction (time X treatment X role) would indicate that the treatment effects were different for patients versus partners.

In order to explore the potential moderating effects of gender and patient holding back as assessed at baseline, additional models were run including the main and interaction effects of (a) gender and (b) patient holding back. A significant moderation effect is indicated by a significant three-way interaction between the moderator (gender or holding back), treatment, and time, or by a significant four-way interaction (moderator X treatment X time X role).

Data were analyzed first by intent to treat (e.g., including all randomized couples, n=130). Of these, 108 couples completed post-treatment assessments (see Figure 1). Reasons for dropout included death/declining health (n=10), not enough time/conflicting demands (n=8), and loss to contact/not returning to medical center (n=4). A second set of analyses was conducted including only those couples who attended at least one treatment session (n=53 in partner-assisted emotional disclosure and n=59 in education/support). The number of sessions completed by couples in each condition is shown in Figure 1. The reasons for not completing sessions were similar to those for dropout.

The distribution of relationship quality was negatively skewed. Thus, this variable was log transformed, and analyses were performed with the log transformed values.

Participant Characteristics

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. More than two-thirds of the patients (71%) were men. Participants were predominantly Caucasian and well-educated. The majority of patients (64.6%) had Stage 4 disease. On average, couples had been married 23.4 years.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Patients (N=130) | Partners (N=130) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 59.4 (12.0) | 59.3 (12.3) |

| Gender (% male) | 71 | 29 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 84.5% | 82.0% |

| African American | 11.6% | 11.2% |

| Other/unknown | 3.9% | 6.4% |

| Education | ||

| <12 years | 14.2% | 8.2% |

| High school graduate | 30.9% | 32.3% |

| Some college | 29.6% | 30.2% |

| College graduate/post-graduate | 25.3% | 29.3% |

| Median days since diagnosis (IQR)* | 207.5 (668) | |

| Cancer site | ||

| Colorectal | 42% | |

| Pancreatic | 15% | |

| Esophageal | 11% | |

| Other | 32% | |

| Cancer Stage | ||

| 2 | n=16 (12.3%) | |

| 3 | n=30 (23.1%) | |

| 4 | n=84 (64.6%) | |

| Cancer treatments at baseline | ||

| Chemotherapy | n=79 (60.8%) | |

| Radiation | n=11 (8.5%) |

Results

Intent to Treat

Results of mixed model dyadic analyses including all participants indicated that there was a significant time X treatment effect for relationship quality (B=−.07, SE=0.03, p=.02). The time X treatment effect was not significant for intimacy or mood disturbance. The three way interactions between time, treatment, and social role (patient versus partner) were also not significant, indicating that the treatment effect did not differ for patients versus partners for any of the outcome variables. There were no significant main effects of time indicating that these variables did not change over time in general. There were also no significant main effects of social role, indicating that levels of relationship quality, intimacy, and mood disturbance did not differ significantly between patients and partners.

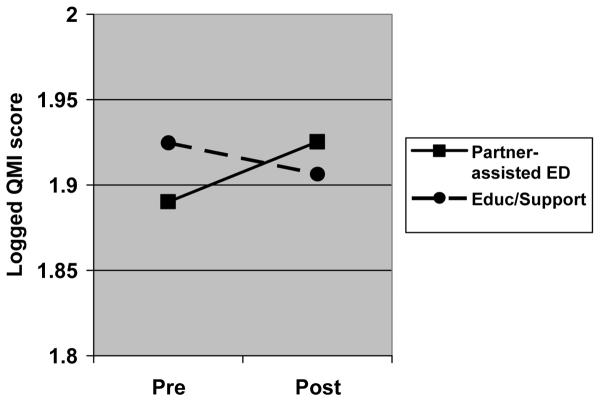

The significant time X treatment interaction for relationship quality was graphed according to the strategies recommended by Preacher, Curran, and Bauer42 (see Figure 2). Patients and spouses in the partner-assisted emotional disclosure condition reported increases in relationship quality from pre to post relative to patients and spouses in the education/support condition.

Figure 2.

Estimated trajectories of change in patients' and partners' scores (logged values) on the Quality of Marriage Index by treatment condition (intent to treat analysis).

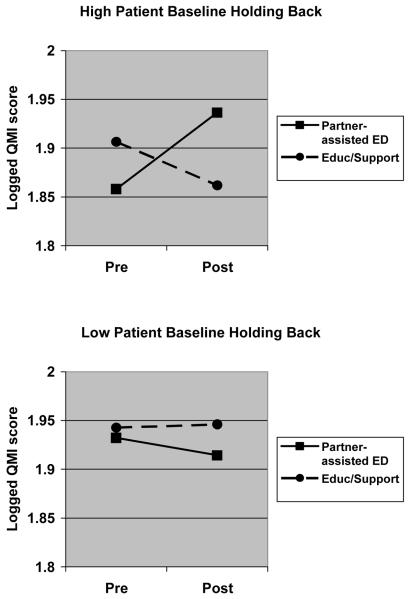

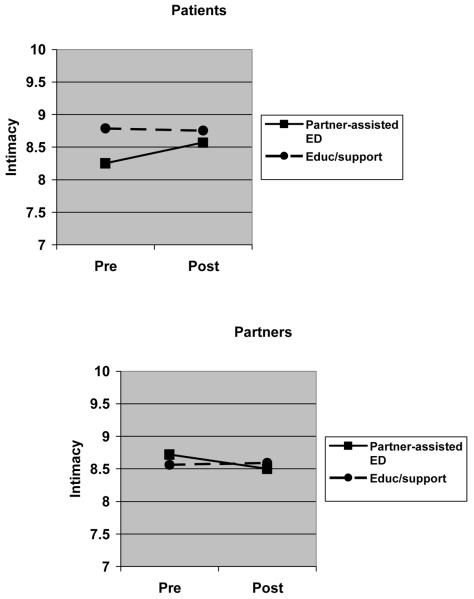

Models including gender as a potential moderator indicated that there were no significant interactions between gender, treatment condition, and time. However, analyses including patient holding back indicated significant three-way interactions (holding back X treatment condition X time) for relationship quality (B=0.10, SE=0.03, p<.0001) and intimacy (B=.56, SE=0.28, p=.02). As can be seen in Figures 3 and 4, the positive effect of the partner-assisted emotional disclosure intervention on relationship quality and intimacy occurred only when patients reported high levels of holding back from talking about cancer-related concerns to their spouse at baseline.

Figure 3.

Estimated trajectories of change in patients' and partners' scores (logged values) on the Quality of Marriage Index by treatment condition and patient baseline holding back (intent to treat analysis).

Figure 4.

Estimated trajectories of change in patients' and partners' scores Miller Social Intimacy Scale by treatment condition and patient baseline holding back (intent to treat analysis).

Treatment completers

The above analyses were repeated, this time including only those couples who had completed at least one session of the intervention (N=53 in partner-assisted emotional disclosure, N=59 in education/support). The time X treatment interaction remained significant for relationship quality (B=−0.08, SE=0.04, p=.02). In addition, there was a significant three-way interaction between time, treatment, and social role (patient versus partner) for intimacy (B=−0.60, SE=0.30, p=.05). There were no main or interaction effects for mood disturbance.

The significant time X treatment X role interaction for intimacy was graphed according to the strategies recommended by Preacher, Curran, and Bauer. 42 As can be seen Figure 5, a positive effect of partner-assisted emotional disclosure on intimacy was seen among patients but not partners. However, in models containing patient baseline holding back, the three-way interaction between holding back, treatment condition, and time continued to be significant for both relationship quality and intimacy; the four-way interaction (holding back X treatment condition X time X role) was not significant. This suggests that both patients and partners experienced improvements in relationship quality and intimacy following the partner-assisted emotional disclosure intervention if the patient initially reported high levels of holding back. Models including gender as a potential moderator indicated that there were no significant interactions between gender, treatment condition, and time.

Figure 5.

Estimated trajectories of change in scores on the Miller Social Intimacy Scale by social role (patient versus partner) and treatment condition (treatment completer analysis).

Discussion

Findings from this study suggest that a brief, couple-based intervention that specifically targeted communication of cancer-related thoughts and feelings in patients with GI cancer led to improvements in relationship quality and intimacy for couples in which the patient initially reported higher levels of holding back from discussing cancer-related concerns. This finding is noteworthy in light of the brevity of the intervention, the length of marriage among couples in the study (mean=24 years), and the severity of the patient's illness (two-thirds of the patients were diagnosed with Stage 4 cancer). Improving the quality of the couple relationship is particularly important in this population due to their shortened life expectancy and the vital role that spouses play in patients' care at the end of life. This study had a number of methodological strengths including comparing the partner-assisted emotional disclosure intervention to a couples cancer education/support condition that controlled for time and attention given to the patients and partners, and the use of sophisticated data analytic techniques (e.g., multilevel models) that are uniquely suited to analyzing data from couple-based interventions.40, 41

“Holding back” likely reflects patients' active inhibition of disclosing their cancer-related concerns with their partners rather than a general tendency towards inexpression. Thus, patients who report high levels of holding back may want to discuss these concerns but may be reluctant to do so. It is interesting to note that, on average, patient's levels of holding back as assessed at baseline were quite low (mean=0.82, SD=0.99, range=0–4). Thus, even patients considered “high” in holding back did not indicate that they held back from discussing their cancer-related concerns with their spouse to a large degree. These levels of holding back are similar to what we found in a previous study with the same patient population.16 However, even this relatively modest degree of holding back was associated with significantly poorer individual and relationship functioning.16 Results from this study suggest that helping patients to overcome their reluctance to express their concerns may lead to significant improvements in the quality of their marital relationships and in the amount of intimacy they share with their spouse. This is consistent with research indicating that disclosure of personal, vulnerable information is a central component of intimacy13, 14 which is in turn closely linked to relationship satisfaction.27

Contrary to our hypotheses as well as to the literature on private emotional disclosure, the intervention did not lead to improvements in psychological distress among patients or partners. One possible explanation for this lack of findings is that, although the intervention was designed to facilitate patient disclosure, patients may have been unable to disclose their thoughts and feelings to their partner (and in the presence of a therapist) to the extent that they would have in a private disclosure protocol. Some patients may have felt inhibited about sharing their thoughts and feelings with their partner and/or the therapist. Alternatively, the sessions' dual focus on both the patient's disclosure and on the dyad's communication processes may have distracted the patient from expressing and processing their thoughts and feelings to the same extent that they would have in a private disclosure protocol. Another possibility is that patients may have felt that their disclosure was burdensome to their partners, and that this sense of burden off-set any psychological benefits of disclosure. Importantly, however, there was no evidence that the partner-assisted emotional disclosure sessions led to increased psychological distress for patients or partners. Finally, it is possible that the effects of the intervention were dampened by the fact the many couples did not receive all four sessions. Future studies of partner-assisted emotional disclosure should consider strategies to increase retention in the intervention, such as offering home-based sessions or targeting patients with less advanced disease. It may also be necessary to increase the number of sessions so that patients become more comfortable with the setting and the communication guidelines and have more opportunity to disclose. In addition, future studies should explore the possibility that the two formats of disclosure – partner-assisted versus private – have different effects. Partner-assisted protocols in which patients disclose their concerns to their partner may be more effective in enhancing couples' relationships, whereas private disclosure protocols in which patients write about their thoughts and feelings may be more effective in reducing patient's psychological distress. If so, then treatment can be targeted according to the specific needs of the patient and the couple.

Due to the focus of the intervention on patient disclosure, it is perhaps less surprising that partners did not benefit in terms of reduced psychological distress. While many partners expressed appreciation for the opportunity to hear the patient discuss his/her concerns, it was also at times difficult for them to listen to the patient describe painful experiences and emotions, particularly because partners were asked to refrain from reassuring the patient or giving advice or suggestions. Thus, any benefits for partners may have been off-set by increased burden from listening to the patient's concerns. However, as noted above, partners did not experience increases in distress as a result of the partner-assisted emotional disclosure intervention. Given the high burden of cancer caregiving43, 44, particularly when the patient has advanced disease45, 46, particular attention should be given to developing interventions that may help alleviate partner distress. Enhancing cancer-related communication between partners may ultimately benefit both patients and partners if it leads to increased relationship functioning and a shared understanding about the meaning of the illness experience. One interesting direction for future research would be to explore the relative benefits for patients and partners of including a more reciprocal approach to disclosure (e.g. partners disclosing to patients as well as patients to partners). In addition, longer-term effects of the partner-assisted emotional disclosure intervention should be examined as it is possible that short-term improvements in relationship satisfaction could potentially lead to improvements in individual psychological well-being for patients and/or partners.

These findings build on the literature on private emotional disclosure which has found that writing about cancer concerns can lead to benefits for patients with cancer17–19. To our knowledge, this is the first study of cancer patients that has applied a disclosure paradigm in the context of a patient disclosing to their spouse or intimate partner. There are several reasons that partner-assisted disclosure is particularly appropriate for cancer patients and their partners. The diagnosis and treatment of most cancers places major demands not only on patients but their partners as well. Although patients and partners must work together to meet these demands, communication particularly about emotionally related topics can be challenging even in relationships that overall are strong. The results of the current study are promising in showing that a brief intervention targeting patient disclosure to their partner can be beneficial for couples' relationships. Future studies are needed to replicate these findings in patients and partners who are coping with other types of cancer (e.g. breast cancer, prostate cancer, or lung cancer).

From a clinical perspective, the findings of this study suggest that psychologists, social workers, and other mental health professionals working with GI cancer patients may want to identify patients who tend to hold back from expressing their cancer-related thoughts and feelings to their partners, and work with them and their partners to help facilitate communication. In the current study, the only demographic or medical variable associated with holding back was age, indicating that younger patients were more likely to hold back. This is consistent with clinical impressions that younger patients often have more difficulty coping cancer. Overall, despite the fact that most couples reported having strong relationships at baseline, many commented on the fact that the treatment sessions were helpful in enhancing their relationship further in that they gave them the opportunity to discuss important issues that they had previously avoided. Similar to what has been reported in previous studies,6–8 patients often noted that their biggest need was for someone to listen to them, and that it was helpful to be able to express their concerns more openly to their partner. Partners, on the other hand, often found it difficult not to respond to the patient's concerns with reassurance or problem-solving, but over the course of the sessions learned to appreciate that validating the patient's concerns was more helpful to the patient and also resulted in a higher degree of patient disclosure.

Several limitations need to be kept in mind when interpreting the results of this study. First, the participation rate in this study (25%) is somewhat lower than that obtained in other recent couple-based or caregiver-assisted studies with cancer patients (range= 34% 47, 48 to 43%49), possibly due to the fact that many of the patients approached about participation were quite ill. Patient illness was a significant factor in attrition as well. Recruitment and retention were also likely hampered by the fact that participation required that couples attend four, face-to-face sessions. Future studies could test the efficacy of telephone- or internet-based interventions that could be made available to a wider population of couples. A second limitation is that the couples who participated in this study on average reported high levels of relationship quality. The findings may not generalize to couples who are more distressed who quite likely need a more lengthy and intensive intervention. Third, the results of the study likely reflect the sample of patients who participated who tended to be well-educated and have advanced disease. The gender composition of the sample (more male than female patients), may have also influenced the pattern of results. Women have been found to self-disclose more than men, although this difference diminishes in the context of heterosexual relationships14, 50 and was not evident from the baseline data of the current study. Gender differences in response to written emotional disclosure interventions have also been found.22 Thus, it is possible that the results would not generalize to samples of female patients, or to contexts other than heterosexual romantic relationships

Taken together, the results of this study suggest that future research on partner-assisted emotional disclosure is warranted. This is a novel intervention that builds on both the private emotional disclosure and the cognitive-behavioral marital therapy literature. While the benefits in the current study were reflected primarily in indices of the quality of the couple's relationship, it is possible that these short-term improvements in relationship quality and intimacy could be associated with longer-term improvements in both patient and partner individual functioning. In addition to examining longer-term effects, future research could also explore methods of enhancing the effects of the intervention, such as using a mixture of lab-based and home-based partner-assisted disclosure sessions, increasing the number of sessions, and/or exploring the relative benefits of having partners disclose to patients as well as patients to partners. In addition, future research needs to focus on more distressed couples for whom more intensive approaches are likely necessary. Given the important role that partners play in patients' adaptation to cancer, it is critical to help patients and partners communicate effectively about their cancer-related concerns.

Condensed Abstract.

Partner-assisted emotional disclosure is a brief intervention focused on facilitating the cancer patient's emotional disclosure to his/her partner. Results from this study suggest that this intervention led to increases in relationship quality and intimacy for couples in which the patient initially held back from disclosing cancer-related concerns.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Grant R01 CA100743 from the National Cancer Institute

References

- 1.Helgeson VS, Cohen S. Social support and adjustment to cancer: reconciling descriptive, correlational, and intervention research. Health Psychol. 1996 Mar;15(2):135–148. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manne S. Cancer in the marital context: a review of the literature. Cancer Invest. 1998;16(3):188–202. doi: 10.3109/07357909809050036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Northouse LL, Mood D, Templin T, Mellon S, George T. Couples' patterns of adjustment to colon cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2000 Jan;50(2):271–284. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolger N, Foster M, Vinokur AD, Ng R. Close relationships and adjustment to a life crisis: the case of breast cancer. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996 Feb;70(2):283–294. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neuling SJ, Winefield HR. Social support and recovery after surgery for breast cancer: frequency and correlates of supportive behaviours by family, friends and surgeon. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27(4):385–392. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90273-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison J, Maguire P, Pitceathly C. Confiding in crisis: gender differences in pattern of confiding among cancer patients. Soc Sci Med. 1995 Nov;41(9):1255–1260. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00411-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Figueiredo M, Fries E, Ingram K. The role of disclosure patterns and unsupportive social interactions in the well-being of breast cancer patients. Psycho-oncology. 2004;13(2):96–105. doi: 10.1002/pon.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunkel-Schetter C. Social support and cancer: Findings based on patient interviews and their implications. Journal of Social Issues. 1984;40:77–98. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manne SaK R. Annual Meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. San Francisco, CA: 1997. Hiding worries from one's spouse: Protective buffering among cancer patients and their spouses. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vess J, Moreland J, Schwebel A, Knaut E. Psychosocial needs of cancer patients: learning from patients and their spouses. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1988;6:31–51. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lichtman RR, Taylor SE, Wood JV. Social support and marital adjustment after breast cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1987;5:47–74. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pennebaker J. Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science. 1997;8(3):162–166. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chelune GJea. Self-disclosure and its relationship to marital intimacy. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1984;40(1):216–219. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198401)40:1<216::aid-jclp2270400143>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prager KJ. The Psychology of Intimacy. Guilford Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pistrang N, Barker C. The partner relationship in psychological response to breast cancer. Soc Sci Med. 1995 Mar;40(6):789–797. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00136-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Hurwitz H, Faber M. Disclosure between patients with gastrointestinal cancer and their spouses. Psychooncology. 2005 Dec;14(12):1030–1042. doi: 10.1002/pon.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Moor C, Sterner J, Hall M, et al. A pilot study of the effects of expressive writing on psychological and behavioral adjustment in patients enrolled in a Phase II trial of vaccine therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Health Psychol. 2002 Nov;21(6):615–619. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.6.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Sworowski LA, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of written emotional expression and benefit finding in breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2002 Oct;1520(20):4160–4168. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenberg H, Rosenberg S, Ernstoff M, et al. Expressive disclosure and health outcomes in a prostate cancer population. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2002;32(1):37–53. doi: 10.2190/AGPF-VB1G-U82E-AE8C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zakowski S, Ramati A, Morton C, Johnson P, Flanigan R. Written emotional disclosure buffers the effects of social constraints on distress among cancer patients. Health Psychology. 2004;23(6):555–563. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pennebaker JW, Seagal JD. Forming a story: the health benefits of narrative. J Clin Psychol. 1999 Oct;55(10):1243–1254. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199910)55:10<1243::AID-JCLP6>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smyth JM. Written emotional expression: effect sizes, outcome types, and moderating variables. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998 Feb;66(1):174–184. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baucom DHaE N. Cognitive behavioral marital therapy. Brunner/Mazel; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epstein NaB DH. Enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy for couples: A contextual approach. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baucom DH, Shoham V, Mueser KT, Daiuto AD, Stickle TR. Empirically supported couple and family interventions for marital distress and adult mental health problems. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998 Feb;66(1):53–88. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baucom DH, Sayers SL, Sher TG. Supplementing behavioral marital therapy with cognitive restructuring and emotional expressiveness training: an outcome investigation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990 Oct;58(5):636–645. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.5.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merves-Okin L, Edmund A, Frank B. Perceptions of intimacy in marriage: A study of married couples. American Journal of Family Therapy. 1991;19(2):110–118. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jemal A, Murray T, Samuels A, Ghafoor A, Ward E, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003 Jan–Feb;53(1):5–26. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fitzsimmons D, Johnson CD. Quality of life after treatment of pancreatic cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1998 Apr;383(2):145–151. doi: 10.1007/s004230050106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernhard JaH C. Gastrointestinal cancer. In: JCH, editor. Psycho-oncology. Oxford University Press; New York: 1998. pp. 324–339. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmier J, Elixhauser A, Halpern MT. Health-related quality of life evaluations of gastric and pancreatic cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999 May-Jun;46(27):1998–2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ulander K, Jeppsson B, Grahn G. Quality of life and independence in activities of daily living preoperatively and at follow-up in patients with colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 1997 Sep;5(5):402–409. doi: 10.1007/s005200050099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norton R. Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1983;45:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heyman RE, Sayers SL, Bellack AS. Global marital satisfaction versus marital adjustment: an empirical comparison of three measures. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8(4):432–446. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller RS, Lefcourt HM. The assessment of social intimacy. J Pers Assess. 1982 Oct;46(5):514–518. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4605_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller R, Lefcourt H. Miller Social Intimacy Scale. In: Corcoran K, Fischer J, editors. Measures for Clinical Practice: A Sourcebook. 3rd edn. Free Press; New York, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. EDITS Manual: Profile of Mood States. Educational and Industrial Testing Service; San Diego, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson B. Psychological interventions for cancer patients to enhance quality of life. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:552–568. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.4.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Antoni M, Lehman J, Kilbourn K, et al. Cognitive behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2001;20(1):20–32. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kenny D, Kashy D, Cook W. Dyadic Data Analysis. Guilford; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atkins D. Using multilevel models to analyze couple and family treatment data: Basic and advanced issues. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19(1):98–110. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim Y, Schulz R. Family caregivers' strains: comparative analysis of cancer caregiving with dementia, diabetes, and frail elderly caregiving. Journal of Aging and Health. 2008;20(5):483–503. doi: 10.1177/0898264308317533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rhee Y, Yun Y, Park S, et al. Depression in family caregivers of cancer patients: the feeling of burden as a predictor of depression. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(36):5890–5895. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.3957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Braun M, Mikulincer M, Rydall A, Walsh A, Walsh GR. Hidden morbidity in cancer: spouse caregivers. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(30):4829–4834. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Given B, Wyatt G, Given C, et al. Burden and depression among caregivers of patients with cancer at the end of life. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2004;31(6):1105–1117. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.1105-1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kurtz M, Kurtz J, Given C, Given B. A randomized, controlled trial of a patient/caregiver symptom control intervention: effects on depressive symptomatology of caregivers of cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2005;30(2):112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manne S, Ostroff J, Winkel G, et al. Couple-focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(4):634–646. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Given C, Given B, Rahbar M, et al. Effect of a cognitive behavioral intervention on reducing symptom severity during chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Feb 1;22(3):507–516. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dindia K, Allen M. Sex differences in self-disclosure: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 1992 Jul;112(1):106–124. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]