Abstract

In this paper, we report the successful use of non-cadmium based quantum dots (QDs) as highly efficient and non-toxic optical probes for imaging live pancreatic cancer cells. Indium phosphide (core)-zinc sulphide (shell), or InP/ZnS, QDs with high quality and bright luminescence were prepared by a hot colloidal synthesis method in non-aqueous media. The surfaces of these QDs were then functionalized with mercaptosuccinic acid to make them highly dispersible in aqueous media. Further bioconjugation with pancreatic cancer specific monoclonal antibodies, such as anti-claudin 4 and anti-prostate stem cell antigen (anti-PSCA), to the functionalized InP/ZnS QDs, allowed specific in vitro targeting of pancreatic cancer cell lines (both immortalized and low passage ones). The receptor mediated delivery of the bioconjugates was further confirmed by the observation of poor in vitro targeting in non-pancreatic cancer based cell lines which are negative for the claudin-4-receptor. These observations suggest the immense potential of InP/ZnS QDs as non-cadmium based safe and efficient optical imaging nanoprobes in diagnostic imaging, particularly for early detection of cancer.

Keywords: Quantum dots, Bioconjugates, Bioimaging, Pancreatic Cancer, Targeted Delivery

Introduction

Semiconductor nanocrystals, or so called quantum dots (QDs), possess unique optical properties that make them potential candidates as luminescent nanoprobes for biological applications, ranging from immunoassays to live cell and tissue imaging1–13. Such nanomaterials have significant advantages over traditional fluorescent probes such as organic dyes and fluorescent proteins14–17. For example, they have robust photochemical stability, high quantum yield, and excellent resistance to chemical and photochemical degradation, as well as size-tunable photoluminescence that ranges from visible to near-IR with sharp spectral bands6, 18, 19. Also, QDs with different emission colors can be simultaneously excited with a single light source, with minimal spectral overlap, providing significant advantages for multiplexed detection of molecular targets20–22. More importantly, QDs can be tuned to emit in a range of wavelengths by systematically changing the nanoparticle size, shape, and composition, whereas new architecture of organic dyes must be designed to shift their emission towards desirable optically detectable wavelengths9, 21. Thus, these QDs have recently attracted much attention as new generation probes for optical bioimaging6, 23–28.

One major drawback which severely limits the potential for clinical translation of QDs is the toxicity concern of common used of II-VI semiconductors (such as CdSe and CdTe) QDs in biomedical applications. These semiconductors are made up of ionic bonds, which make them structurally fragile and vulnerable to disintegration in biological systems, thus leading to the release of the toxic cadmium ions in the surrounding. Therefore, in recent years the emphasis has shifted towards the fabrication of non-cadmium based QDs for applications in biology. In this direction, QDs made up of III-V semiconductors (such as InP) are extremely promising as they are not only cadmium free, but also more robust structurally owing to the presence of covalent bonds in their matrix29–31. This structural robustness confers enhanced optical stability, and most importantly, reduced toxicity as a result of non-erosion of constituent ions in biological systems32. For example, it was reported that Syrian golden hamsters survived throughout a two-year observation period, where they were given 3 mg/kg InP particles intratracheally for 8 weeks33. Our group has demonstrated the use of folic acid-InP QDs bioconjugates for confocal and two-photon imaging of KB cancer cells29, 34. Also, our group has recently shown that the optical properties of the core-shell structures were strongly depend on the nature of the shell around InP. By simply coating the InP core with a ZnS, ZnSe, and CdSe shell, the emission wavelength can be systematically tuned from ~525 to ~590 and from ~590 to ~680 nm, respectively1. These features have made InP QDs a very attractive candidate for replacing cadmium-based QDs for biological studies. However, till date, there are very little studies reporting the use of InP QDs in bioimaging applications, as they are difficult to prepare because of the sensitivity of precursors and surfactants towards the reaction environment in obtaining good quality InP QDs29. We have successfully overcome these challenges by using a simple one pot synthesis approach in fabricating high quality InP/ZnS QDs35.

Pancreatic cancer ranks as the fourth leading cause of cancer related deaths in the United States. The mean survival rate is estimated to be 6 months, and less than 5% of all patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer survive beyond 5 years36, 37. This dismal scenario is primarily due to the fact that most patients are diagnosed when the cancer has reached an advanced stage, which is the result of a lack of specific symptoms and limitations in diagnostics that allows the disease to elude detection during its formative stages38. Thus, it is critical that novel targeted bioimaging probes be developed which would specifically diagnose pancreatic cancer in vivo at their earliest stage, without exerting any systemic toxicity. Non-toxic InP based QDs with high luminescence and ease of linkage with cancer-specific targeting ligands are therefore ideal candidates for this purpose27, 39.

We here present the use of InP/ZnS QDs as targeted optical probes for labeling human pancreatic cancer cells, both immortalized and low-passage ones. Antibodies such as anti-claudin 4 and anti-PSCA, whose corresponding antigen receptors are known to be overexpressed in both primary and metastatic pancreatic cancer, were utilized for the synthesis of QD bioconjugates40–42. The mercaptosuccinic acid-functionalized InP/ZnS QDs were conjugated with antibodies using carbodiimide chemistry. To our knowledge, no study has been reported on the use of antibody-InP/ZnS QD bioconjugates as targeted optical probes for live pancreatic cancer cells imaging. With confocal microscopy and localized spectroscopy, we demonstrate receptor-mediated uptake of QD-antibody bioconjugates into pancreatic cancer cells. Also, we have found that the InP/ZnS QDs have very low cytotoxic effect on the cells, thereby justifying our strategy of using them for targeted bioimaging.

Results and Discussion

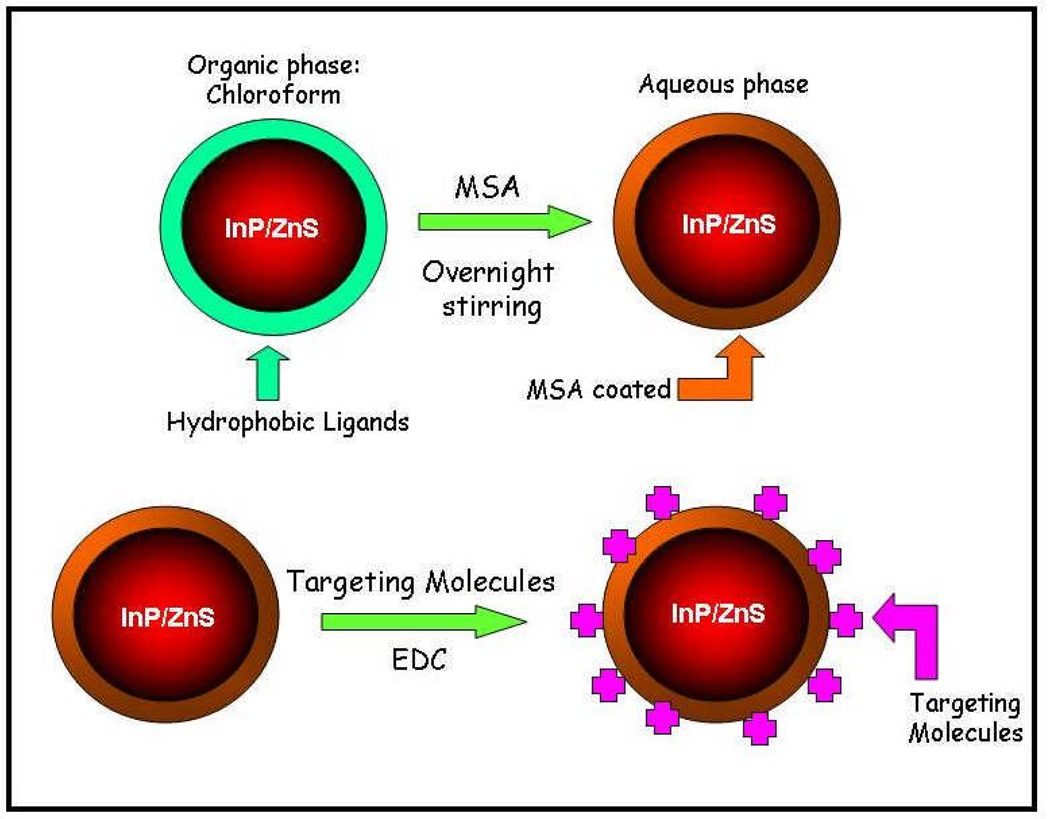

Scheme 1 illustrates the surface functionalization and bioconjugation of QDs for cellular targeting and imaging. The first step involves the ligand exchange process of myristic acid-capped QDs with mercaptosuccinic acid in the organic phase. The mercaptosuccinic acid-coated QDs with carboxyl groups being terminated on their surface are readily dispersible in water. Next, the mercaptosuccinic acid-coated QDs are conjugated with targeting biomolecules by using the carbodiimide chemistry.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration showing the formation of the water-dispersible InP/ZnS QD-bioconjugates.

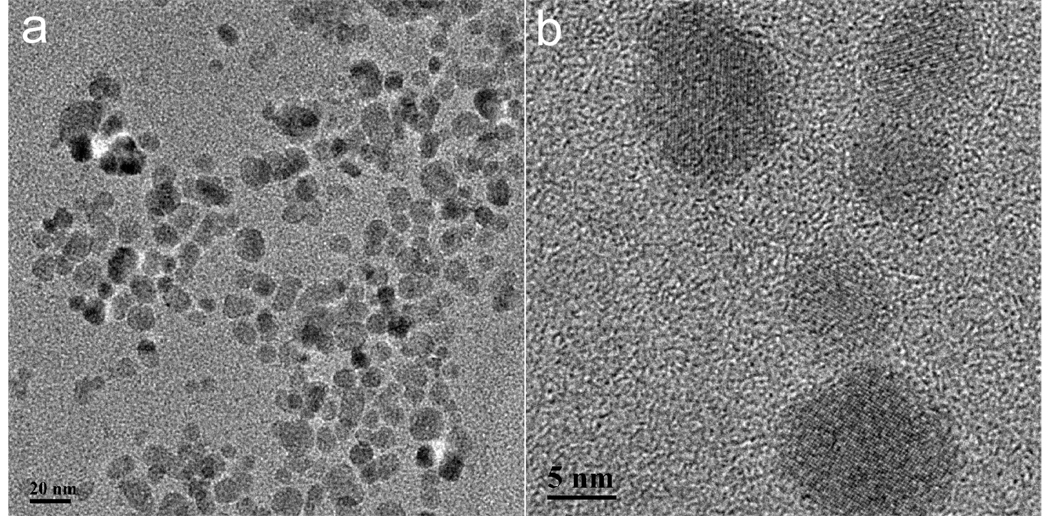

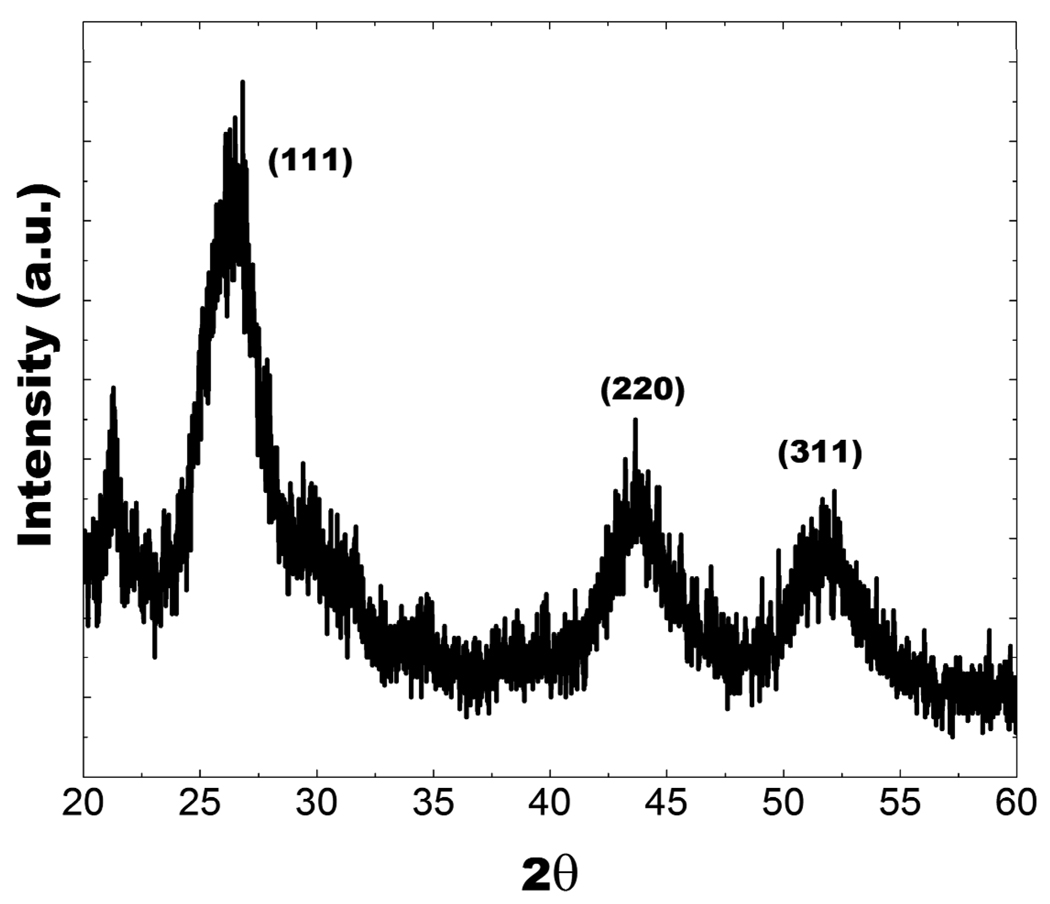

The InP/ZnS QDs were systematically characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and powder X-ray diffraction (XRD). Figures 1a and 1b show the TEM images of InP/ZnS QDs with a diameter of 15–20 nm, at low and high resolution, respectively. The powder XRD pattern from the InP/ZnS QDs is shown in Figure 2. All of the diffraction peaks from the four samples can be readily indexed to the zinc-blende InP. The three strong peaks with 2θ values of 26.05, 30.15, and 43.15° correspond to the (111), (220), and (311) planes, respectively.

Figure 1.

(a) & (b) TEM image of water-dispersible InP/ZnS QDs at different magnification.

Figure 2.

XRD profile of InP/ZnS QDs.

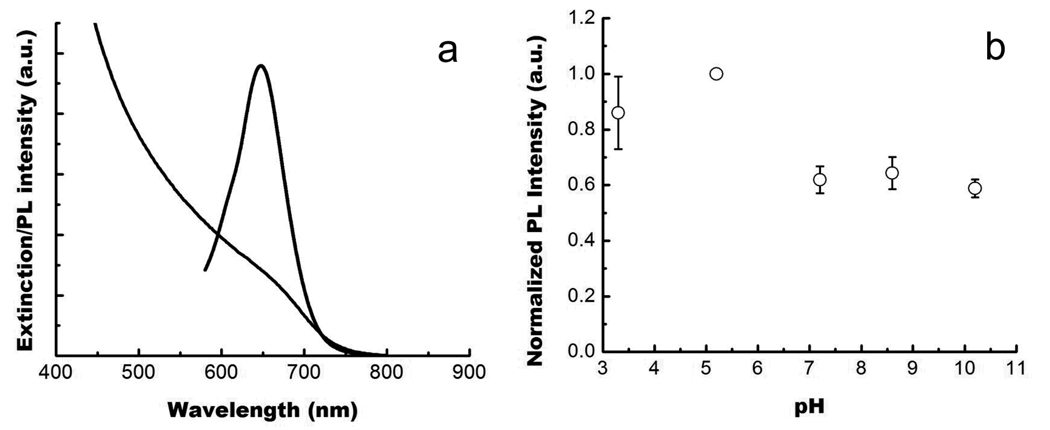

Figure 3a shows the absorption and photoluminescence (PL) spectra of InP/ZnS in chloroform. The QDs demonstrate an absorption feature at ~645 nm and a band edge emission at ~650 nm. The PL quantum yield (QY) of the InP/ZnS QDs is estimated to be 25 – 30%. The QY was measured by comparing the emission of the QD with that of a fluorophore with known QY (rhodamine 6G), at normalized absorption. The QY value, although not as high as that for the cadmium-based quantum dots, is still sufficient for live cell imaging studies. The solution containing mercaptosuccinic acid-coated InP/ZnS QDs did not show any significant decrease in the photoluminescence intensity for two days, even after conjugating them with an antibody.

Figure 3.

(a) Absorption and emission spectra of InP/ZnS QDs dispersed in chloroform. (b) Photoluminescence stability of InP/ZnS QDs under different pH conditions after dispersing the QDs for 48 hours.

The optical stability of the mercaptosucinnic acid coated InP/ZnS QDs under different pH was examined. Figure 3b shows the PL intensity of the InP/ZnS QDs from acidic to basic pH conditions. In changing the pH from 3.3 to 10.8, more than 35% of variation in the PL intensity is observed, although they remain stable for more than 48 hours. Even with a ~38% decrease in PL intensity at neutral pH, there is still sufficient photoluminescence intensity for cell imaging studies in our case (see below). At pH 10.8, a ~40% loss of their PL was observed immediately, and further loss of the PL intensity was observed after one to two days of storage at room temperature. However, it is worth mentioning that for the InP/ZnS QDs dispersion in the pH range of 3.3 to 8.5, the band edge emission of PL spectra was still maintained even after storing them for more than two to three days. The mercaptosuccinic coated InP/ZnS QDs also exhibit stable PL for more than one week when dispersed in common physiological buffers such as PBS and MES.

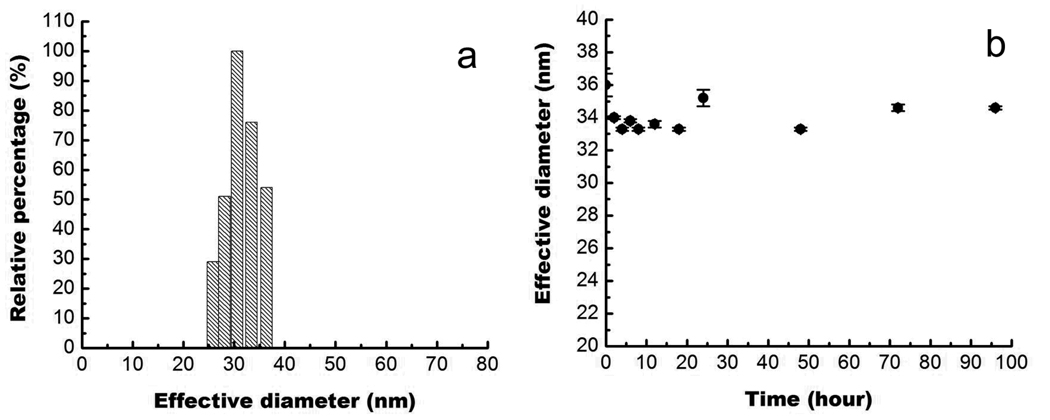

DLS was used to estimate the size distribution of the prepared nanoparticle suspensions. Figure 4a shows the effective size as well as size distributions of InP/ZnS particle suspensions in 1x PBS. From Figure 4a, it is evident that the particles in 1x PBS buffer have an average effective diameter of ~33 nm. According to our TEM results, the size of the InP/ZnS particles is 15–20 nm. This does not directly agree with the DLS data. However, TEM only measures the size of the inorganic semiconductors and does not consider the surface capping surfactants. The results of the DLS experiments demonstrate the hydrodynamic diameter of the particles that includes the overall size of the solvated capping ligands. A similar trend in size measurements between DLS and TEM has been observed in the previous reports29.

Figure 4.

(a) DLS plot of InP/ZnS QDs water dispersion. (b) Time-dependent of hydrodynamic diameter of InP/ZnS QDs dispersed in PBS buffer.

In this study, DLS was also used to determine the colloidal stability of the InP particles dispersed in the PBS buffer. Figure 4b shows the time-dependent profile of the effective diameter of the QDs. Over the time range from 0 to 90 hours, the effective diameter varies by less than 10%, indicating that their colloidal stability is not affected under physiological pH. In addition, we want to emphasize that the result shown here is to demonstrate the non-aggregation of the QDs under physiological conditions.

One of the greatest challenges in preparing stable-aqueous dispersion of nanoparticles involves the selection of small, biocompatible, and low toxicity hydrophilic ligands to replace the hydrophobic moieties on the surface of the QDs. An appropriate ligands improves the overall colloidal stability of the QDs, which is essential to obtain successful bioconjugation20. We have found that the mecarptosuccininc acid-coated QDs are more optically and colloidally stable than the “traditional” mercaptoacetic acid-coated QDs. This may be due to the presence of two carboxyl groups in the mercaptosucinnic acid molecule. Also, with the mecarptosuccininc acid-coated QDs, we were able to maintain the consistency of conjugating biomolecules with the QDs using the carbodiimide chemistry. So far, we have successfully conjugated transferrin, folic acid, monoclonal antibodies, polyclonal antibodies, and other proteins to the QDs. These bioconjugates can be used to label cells without any obvious loss of photoluminescence. We have observed that mercaptoacetic acid-coated QDs are found to be more toxic than the mecarptosuccininc acid-coated QDs, when they are used for labeling cells at high concentration (~10 µg/mL). This finding suggests that the surfactants are also playing a critical role in contributing to the overall toxicity level of the functionalized QDs.

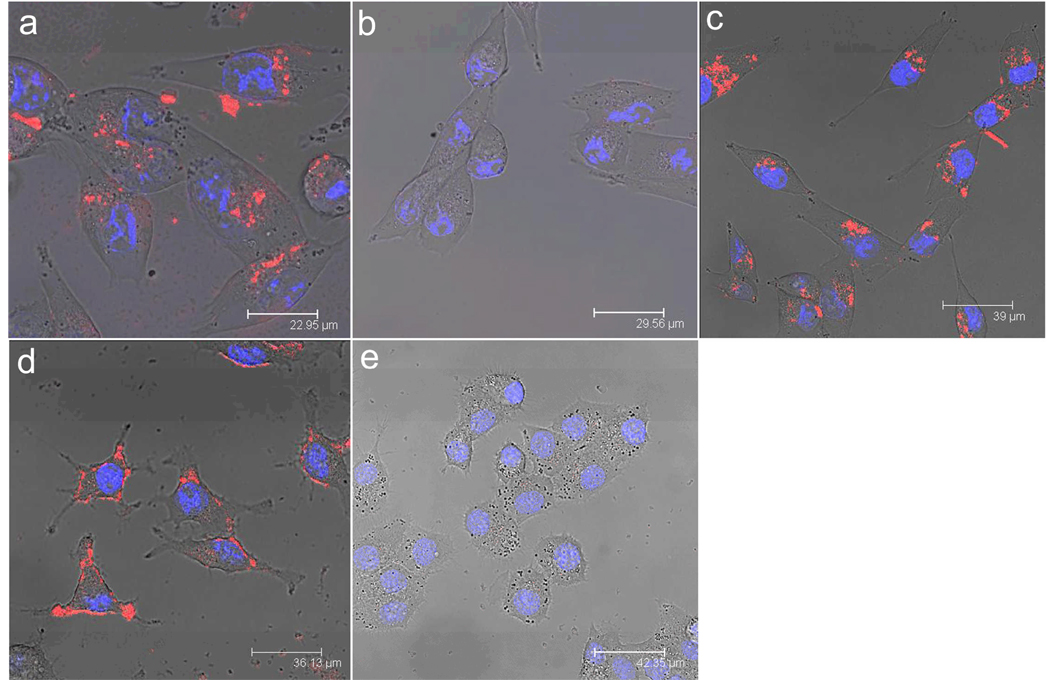

In the in vitro study, we used InP/ZnS QDs to label human pancreatic cancer cells (MiaPaCa or Panc-1). The QDs were conjugated with anti-claudin 4, whose corresponding antigen receptors are known to be overexpressed in both primary and metastatic pancreatic cancer43. Figure 5a illustrates labeling of pancreatic cancer cells (MiaPaCa) with the bioconjugates, anti-claudin 4-InP/ZnS QDs. Cellular uptake of the QD-bioconjugates can be clearly observed from the robust optical signal of the MiaPaCa cells, while no or little signal is observed in the case of cells treated with non-bioconjugated QDs (see Figure 5b), which demonstrates the specific nature of the antibody-mediated targeting of the pancreatic cancer cells. Local spectral analysis of the overall cell staining by the bioconjugated QDs confirms the origin of cellular luminescence signal from the InP/ZnS QDs. More importantly, no signs of morphological damage to the cells were observed upon treatment with various QDs, thereby illustrating their low cytotoxicity. The observed staining pattern is indeed due to the functionalized QDs, which have been demonstrated by several reports19, 29, 44–46. In addition to monoclonal antibody conjugation, QDs were also conjugated with a polyclonal antibody, anti-PSCA, for specific targeting of human pancreatic cancer cells. Figure 5c shows confocal images of MiaPaCa pancreatic cancer cells labeled with anti-PSCA-QD bioconjugates. A strong uptake of the anti-PSCA-QD bioconjugates was also observed. These prepared QD bioconjugates (both monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies) were also further tested in a low passage pancreatic cancer cell line XPA3 and a similar labeling trend was observed (see Figure 5d). From these results, it clearly shows that the engineered InP/ZnS bioconjugates can serve as a potential biocompatible targeted nanoprobe to specifically diagnose human pancreatic cancer cells.

Figure 5.

Confocal microscopic images of (a) MiaPaCa cells treated with anti-claudin 4-conjugated InP/ZnS QDs; (b) MiaPaCa cells treated with unconjugated InP/ZnS QDs; (c) MiaPaCa cells treated with anti-PSCA-conjugated InP/ZnS QDs; (d) XPA3 cells treated with anti-claudin 4-conjugated InP/ZnS QDs; and (e) KB (human nasopharyngeal epidermal carcinoma cell line) cells treated with anti-claudin 4-conjugated InP/ZnS QDs. In all cases, blue represents emission from Hoechst 33342 and red represents emission from InP/ZnS QDs.

To further confirm a receptor-mediated uptake of the bioconjugates, receptor-negative cells (human nasopharyngeal epidermal carcinoma cell line, also known as KB) for claudin-4 were treated with anti-claudin 4-InP/ZnS bioconjugates. A significantly reduced uptake of both the QD-bioconjugates in KB cells was observed (see Figure 5e) comparing to that for Panc-1 and MiaPaCa cells under similar conditions. This experiment confirms “active” targeting, or the receptor-mediated nature of labeling of pancreatic cancer cells with the bioconjugated QDs.

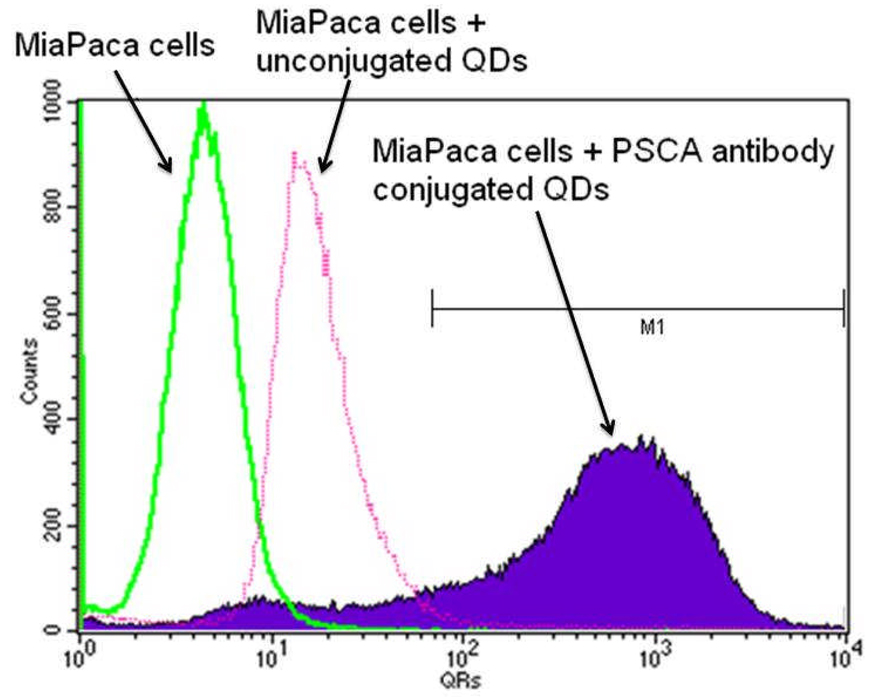

In addition to receptor negative cell lines, flow cytometry was used to quantify their luminescence from the treated cells as shown in Figure 6. The fluorescence intensity of untreated cells was in the range between 100 and 101, and the cells treated with unconjugated QDs exhibited luminescence intensity in the range between 101 and 102. Thus, the cells that exhibited luminescent intensity higher than 102 were taken as positively labeled with bioconjugates. The superior uptake of the bioconjugated nanoparticles is evident from the fact that there is a noticeable change in the luminescence signal observed between unconjugated QDs and antibody conjugated QDs labeled Panc-1 cells, indicating that the specific uptake capability of the bioconjugates is maintained well after the conjugation with QDs.

Figure 6.

Flow cytometry data showing the relative uptake of unconjugated QDs and PSCA conjugated QDs in MiaPaCa cells. The number of positively labeled cells was represented as the percentage of total cell counts.

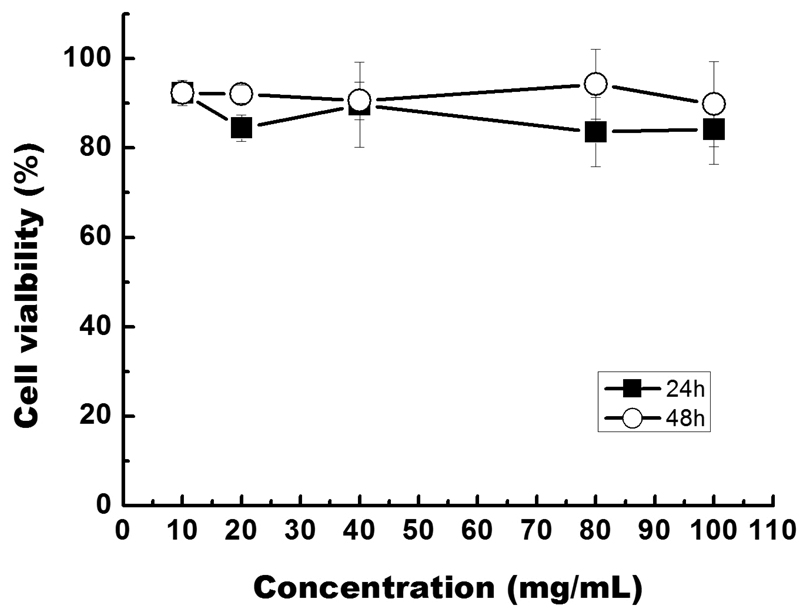

So far, cytotoxicity of cadmium-based QDs has been consistently reported for in vitro studies15, 47, 48. The cause of cytotoxicity has been suggested to depend on a number of factors including size, capping agents, concentration of QDs, coating materials, and processing parameters9. For example, Derfus et al. have shown that uncapped CdSe QDs will slowly decomposes in aqueous solution and generate Cd2+ ions47. The Cd2+ ions concentration was directly correlated with the cytotoxic effects. Shiohara et al. have reported the cytotoxic effects of CdSe/ZnS QDs with different sizes on three different cell types49. To our knowledge, no studies were reported on the cyctotoxicity of InP/ZnS QDs. We have examined the cytotoxicity of InP/ZnS QDs using the cell viability (MTS) assay on Panc-1 cells. Figure 7 shows that the viability of treated cells (for both 24 and 48 hours) are in the range of 80–90 % relative to that of untreated cells, even at a treatment concentration as high as ~300 µg/mL. This safe dosage is 30 and 15 times higher than that of the cyctotoxicity dosage of CdTe48 and PbSe50 QDs, respectively. This result strongly indicates that the InP/ZnS QDs have a relatively low cellular cytotoxicity, thereby justifying our strategy of using them as non-cadmium based targeted optical probes for biomedical applications.

Figure 7.

In vitro cell viability of MiaPaCa treated with varying concentrations of InP/ZnS QDs for 24 and 48 hours. Percentage cell viability of the treated cells is calculated relative to that of untreated cells (with arbitrarily assigned 100 % viability).

To date, many reports have shown the use of cadmium-based QDs for in vitro and in vivo targeted imaging. However, a major limitation of using cadmium-based QDs is their potential toxicity that is due to the degradation of QDs and resulting cadmium and selenium leakage to the biological environment. So far, there are many reports regarding the short and long-term toxicity caused by cadmium-based QDs47, 48. In our study, we did not observe any cytotoxicity effects of the InP/ZnS QDs in vitro for up to 48 hours of treatment. In a recent report, it was reported that no adverse effects were found in mice treated with CdSe QDs. For example, Akerman et al. administrated peptide-labeled CdSe/ZnS QDs into mice and studied the tissue distribution51. It was found that these functionalized QDs accumulated in the liver and spleen, in addition to the targeted sites and this nonspecific accumulation were reduced by further modifying the QD surface with PEG molecules. The group reported that no acute toxicity was caused by this QDs formulation after 24 hours of circulation. Similarly, Larson et al. reported that no acute toxicity was observed after injecting CdSe/ZnS QDs into the mice and hypothesized that CdSe/ZnS QDs successfully excrete from the body before the breakdown of surface coating that will cause the leakeage of heavy metals from the core materials27. However, it is still debatable whether cadmium-based QDs will eventually degrade in biological environment and causes acute toxicicity in long term. Many scientists are currently investigating this issue, but no conclusions on the in vivo toxic effects of cadmium-based QDs have been drawn to date. In a recent report from Nie’s group, the authors have suggested that if it is revealed in the near future that Cd ions is indeed released during their usage in the biological environment, then, new types of QDs must be developed for advancing the biomedical imaging field52. Thus, we suggest that InP/ZnS QDs might be a good alternative probe for replacing cadmium-based QDs for biological use. We have noted that no studies are available in the literature on the toxicity of InP/ZnS particles and at present we can only speculate and extrapolate from other relevant in vivo studies using indium-based nanoparticles. For in vivo studies using InAsP/ZnSe QDs, ~150 pmol of injected QDs contains 22 µg of indium53. It was reported that an average American ingests on the order ~10 µg of indium daily from food and water53, 54. Therefore, despite being composed of potentially toxic materials, the dosage may be small enough that overall toxicity is low. It is worth noting that reports on the development of targeted probes for detecting human pancreatic cancer are very few. Thus, there is an urgency to develop robust imaging agents that can specifically target pancreatic cancer in vivo, leading to improved diagnosis at an early stage. We believe that the current work will serve as an important milestone for future in vivo studies aimed at an early detection of pancreatic cancer, where the tumor targeting efficiency of multiple pancreatic cancer-specific markers can be simultaneously used.

Conclusions

In summary, we have synthesized photostable, biocompatible and water-dispersible InP/ZnS QDs by a facile method. These mercaptosuccinic-coated QDs can be readily conjugated with monoclonal as well as polyclonal antibodies for targeted bioimaging. By using confocal microscopy technique, we have demonstrated the labeling of QD bioconjugates in claudin-4 and PSCA overexpressing pancreatic cancer cells such as MiaPaCa and the low passage cell line, XPA-3. An efficient receptor-mediated uptake of the InP/ZnS bioconjugates in MiaPaCa cells is confirmed by their robust cellular staining, as opposed to the weaker staining of the bioconjugates in receptor-negative (KB) cells. These findings not only offer insights into the receptor-mediated delivery mechanism, but also help the design and development of future nanoprobes for in vivo cancer detecting and therapeutic applications. InP/ZnS QDs combining the brightness, photostability, and biocompatibility characteristics will serve as a new generation of targeted optical probes for several biomedical applications, including early detection of cancer, replacing the cadmium-based (e.g. CdSe) QDs.

Experimental sections

(a) Materials

Indium acetate, sulfur, myristic acid, tristrimethylsilylphosphine, apo-transferrin, octadecene, and HPLC water were purchased from Aldrich. Zinc 2-ethylhexanoate was obtained from Alfa Aesar. All chemicals were used as received. All solvents (hexane, toluene, DMSO, and ethanol) were of reagent grade and used without further purification. Panc-1, MiaPaCa, and KB cells are purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). All cell culture media and reagents were obtained from Invitrogen (USA).

(b) One-pot synthesis of InP/ZnS quantum dots

The synthesis method was adapted from that presented by Lucey et al.35 4 mmol indium acetate, 6 g myristic acid, and 5 mL octadecene were loaded into a 100 mL three-necked flask. Next, the reaction mixture was slowly heated under an argon atmosphere to 180°C. After 30 minutes of heating, a clear homogeneous solution was obtained. The reaction mixture was maintained at 180°C for another 10 minutes, then 2.6 mL of P(TMS)3 solution (1 g of tristrimethylsilylphosphine P(TMS)3 in 4 mL of octadecene) was rapidly injected. After 10 minutes of heating, the reaction temperature was lowered to 150°C. Separately, an oleylamine-sulfur solution was prepared by dissolving 0.1926 g of sulfur (6 mmol) in 5 mL of oleylamine and zinc 2-ethylhexanoate-octadecene solution was prepared by mixing 2 mL of zinc 2-ethylhexanoate with 5 mL of octadecene. These two mixtures were used for ZnS shell growth. 2 mL of zinc 2-ethylhexanoate-octadecene solution was injected into the reaction mixture. Then, 2 mL of oleylamine-sulfur solution was added drop wise into the reaction mixture. The reaction mixture was then held at ~210°C for 45 minutes and then an aliquot was removed via syringe and was injected into a large volume of toluene at room temperature, thereby quenching any further growth of the QDs. The QDs were separated from the surfactant solution by addition of ethanol and centrifugation. The dark-brown QD precipitate could be readily redispersed in various organic solvents (hexane, toluene, and chloroform).

(c) Preparation of mercaptosuccinic acid functionalized InP/ZnS quantum dots

The preparation method of aqueous dispersion of QDs was adapted from that presented by Bharali et al.29. In this reaction, 4 mmols of mercaptosuccinic acid was mixed with 5 mL of chloroform under vigorous stirring. After stirring for 10 to 15 minutes, 2 mL of concentrated (~10–20 mg/mL) InP/ZnS QDs solution was added into this mixture. Approximately one minute later, 1 mL of ammonium hydroxide was added to this vigorously stirred solution. This solution was stirred overnight at room temperature. The QDs were separated from the surfactant solution by addition of ethanol followed by centrifugation. The precipitate was redispersed in 5 mL HPLC water and the solution was further filtered using a syringe filter with a pore diameter of 0.45 µm. The mercaptosuccinic acid coated QDs have relatively good colloidal stability and no precipitation was observed after several weeks. This solution was kept in the refrigerator at 4°C for further use.

(d) Conjugation of mercaptosuccinic acid-coated InP/ZnS QDs with transferrin

The preparation method for an aqueous dispersion of transferrin-QDs bioconjugate was adopted from our previous report46. From the diluted stock solution, 100 µL mercaptosuccinic acid coated QD stock solution was mixed with 200 µL of 2.5 mM EDC solution and gently stirred for 1 to 2 minutes. Next, 200 µL of transferrin was added into this mixture and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours to allow the protein to covalently bond to the lysine coated QDs.

(e) Conjugation of mercaptosuccinic acid-coated QDs with antibodies

The preparation method of aqueous dispersion antibody-QDs bioconjugate was adopted from that presented by Yong et al.19. 100 µL mercaptosuccinic acid coated QD stock solution was mixed with 100 µL of 2.5 mM EDC solution and 300 µL of water. The mixture was gently stirred for 1 to 2 minutes. Next, 7 µl of anti-claudin 4 (500 µg/mL) was added into this mixture and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours. In this study, we estimated that there are at least 1 to 2 antibodies per QD.

(f) Cell staining studies

For in vitro imaging with QDs, the established human cancer cell lines Panc-1, MiaPaCa, and KB were cultured in Dulbecco minimum essential media (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin, and 1% amphotericin B. In addition, low passage pancreatic cancer cells (XPA-3) were also used, cultured in RMPI-1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin, and 1% amphotericin B. The day before treatment, an appropriate number of cells was seeded in 35 mm culture dishes. On the treatment day, the cells (at a confluency of 70–80 %) in serum-supplemented media were treated with the antibody-conjugated QDs for two hours at 37°C (1–5 µg/mL). Nuclei were then stained with Hoechst 33342 (10 µM, 1 hour; λem 461 nm). After two hours, the cells were washed thrice with PBS and directly imaged in a confocal microscope. In order to confirm that the expression of membrane proteins and the binding of targeted QDs to these proteins is not simply an artifact of long-term passage in established cell lines, we also validated the targeting experiments using XPA3, a low passage cell line established at the Johns Hopkins University. These low passage lines retain many of the biological properties observed in the in vivo tumor setting by virtue of their limited ex vivo passage numbers 55.

(g) Cellular imaging

Confocal microscopy images were obtained using a Leica fluorescence imaging system with laser excitation at 405 nm. All images were taken with the exact same conditions of laser power, aperture, gain, offset, and scanning speed.

(h) Characterization methods

The absorption spectra were collected using an Agilent 8453 UV-Visible spectrophotometer over the range from 300 to 1100 nm. The samples were measured against water as reference. All samples were loaded into a quartz cell for measurements. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) images were obtained using a JEOL model JEM-100CX microscope with an acceleration voltage of 100 kV. The specimens were prepared by drop-coating the sample dispersion onto a carbon coated 300 mesh copper grid, which was placed on a filter paper to absorb the excess solvent. X-ray powder diffraction patterns were recorded using a Siemens D500 diffractometer, with Cu Kα radiation. A concentrated QD dispersion was drop cast onto a quartz plate for measurement. Emission quantum yields (QYs) of the QDs chloroform dispersion were determined by comparing the integrated emission from the QDs to Rhodamin 6 dye solutions of matched absorbance. Samples were diluted so that they were optically thin. The effective size distribution of the QD suspensions was estimated using a dynamic light scattering particle size analyzer (Brookhaven 90Plus fitted with APD detector using a 656 nm laser). The InP/ZnS particles were dispersed in 1x PBS at a concentration of 1 mg/mL for the measurement. These solutions were filtered through a 0.45 µm syringe filter membrane to remove the dust impurities and then analyzed directly.

(i) Cell viability

For each MTS assay, 24 culture wells (8 sets, each set contains 3 wells) of Panc-1 cell were prepared. Seven sets were treated with different concentration of InP/ZnS QDs and the remaining one set was the control. The complete assay was performed thrice, and results were averaged. Various concentrations of QDs ranging from 25 to 350 µg/mL were added to each well and subsequently incubated with the cells for 24 and 48 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. As described in the literature, the absorbance of formazan (produced by the cleavage of MTS by dehydrogenases in living cells) is directly proportional to the number of live cells. After the incubation, 150 µL of MTS reagent was then added to each well and well mixed. The absorbance of the mixtures at 490 nm was measured by using UV-Visible spectrophotometer. The cell viability was calculated as the ratio of the absorbance of the sample well to that of the control well and expressed as a percentage.

(j) Flow Cytometry Analysis

The cellular uptake of QDs, with and without conjugation with various targeting molecules, was quantified by flow cytometry. MiaPaCa cells were seeded at 1.0 × 106 cells per T25 flask and allowed to attach for 24 hours. To determine the extent of QDs uptake, the cells were incubated with 25 µL of nanoparticle (~1 mg/mL) solution per 1 mL serum-free medium for 2 hours. Treated cells were then washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then harvested by trypsinization. The QDs served as the luminescent marker to quantitatively determine their cellular uptake, and the results are analyzed by the FACS Calibur flow cytometry and CellQuest Pro software (Becton Dickenson, Mississauga, CA).

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by grants from the NCI RO1CA119397 and the John R. Oishei Foundation. KTY is supported by the AACR-Pancreatic Cancer Action Network Fellowship for Pancreatic Cancer Research. KTY is indebted to the reviewers for their helpful comments.

References

- 1.Prasad PN. Nanophotonics. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prasad PN. Introduction to Biophotonics. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arya H, Kaul Z, Wadhwa R, Taira K, Hirano T, Kaul SC. Quantum Dots in Bio-imaging: Revolution by the Small. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2005;329:1173–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azzazy HME, Mansour MMH, Kazmierczak SC. From Diagnostics to Therapy: Prospects of Quantum Dots. Clinical Biochemistry. 2007;40:917–927. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruchez M, Jr, Moronne M, Gin P, Weiss S, Alivisatos AP. Semiconductor Nanocrystals as Fluorescent Biological Labels. Science. 1998;281:2013–2016. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamieson T, Bakhshi R, Petrova D, Pocock R, Imani M, Seifalian AM. Biological Applications of Quantum Dots. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4717–4732. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu W, Choi HS, Zimmer JP, Tanaka E, Frangioni JV, Bawendi M. Compact Cysteine-Coated CdSe(ZnCdS) Quantum Dots for in Vivo Applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14530–14531. doi: 10.1021/ja073790m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu W, Howarth M, Greytak AB, Zheng Y, Nocera DG, Ting AY, Bawendi MG. Compact Biocompatible Quantum Dots Functionalized for Cellular Imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:1274–1284. doi: 10.1021/ja076069p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolcott A, Gerion D, Visconte M, Sun J, Schwartzberg A, Chen S, Zhang JZ. Silica-Coated CdTe Quantum Dots Functionalized with Thiols for Bioconjugation to IgG Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:5779–5789. doi: 10.1021/jp057435z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yong KT, Qian J, Roy I, Lee HH, Bergey EJ, Tramposch KM, He S, Swihart MT, Maitra A, Prasad PN. Quantum Rod Bioconjugates as Targeted Probes for Confocal and Two-Photon Fluorescence Imaging of Cancer Cells. Nano Lett. 2007;7:761–765. doi: 10.1021/nl063031m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yong KT, Sahoo Y, Choudhury KR, Swihart MT, Minter JR, Prasad PN. Shape Control of PbSe Nanocrystals Using Noble Metal Seed Particles. Nano Lett. 2006;6:709–714. doi: 10.1021/nl052472n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yong KT, Sahoo Y, Choudhury KR, Swihart MT, Minter JR, Prasad PN. Control of the Morphology and Size of PbS Nanowires Using Gold Nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 2006;18:5965–5972. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yong KT, Sahoo Y, Swihart MT, Prasad PN. Shape Control of CdS Nanocrystals in One-Pot Synthesis. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2007;111:2447–2458. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan WCW, Nie S. Quantum Dot Bioconjugates for Ultrasensitive Nonisotopic Detection. Science. 1998;281:2016–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubertret B, Skourides P, Norris DJ, Noireaux V, Brivanlou AH, Libchaber A. In Vivo Imaging of Quantum Dots Encapsulated in Phospholipid Micelles. Science. 2002;298:1759–1762. doi: 10.1126/science.1077194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konkar A, Lu S, Madhukar A, Hughes SM, Alivisatos AP. Semiconductor Nanocrystal Quantum Dots on Single Crystal Semiconductor Substrates: High Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy. Nano Lett. 2005;5:969–973. doi: 10.1021/nl0502625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yong K-T, Sahoo Y, Swihart MT, Prasad PN. Growth of CdSe Quantum Rods and Multipods Seeded by Noble Metal Nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 2006;18:1978–1982. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romero MJ, vandeLagemaat J, Mora-Sero I, Rumbles G, Al-Jassim MM. Imaging of Resonant Quenching of Surface Plasmons by Quantum Dots. Nano Lett. 2006;6:2833–2837. doi: 10.1021/nl061997s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yong K-T, Roy I, Pudavar HE, Bergey EJ, Tramposch KM, Swihart MT, Prasad PN. Multiplex Imaging of Pancreatic Cancer Cells by Using Functionalized Quantum Rods. Advanced Materials. 2008;20:1412–1417. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michalet X, Pinaud FF, Bentolila LA, Tsay JM, Doose S, Li JJ, Sundaresan G, Wu AM, Gambhir SS, Weiss S. Quantum Dots for Live Cells, in Vivo Imaging, and Diagnostics. Science. 2005;307:538–544. doi: 10.1126/science.1104274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hild WA, Breunig M, Goepferich A. Quantum dots - Nano-Sized Probes for the Exploration of Cellular and Intracellular Targeting. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics. 2008;68:153–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu G, Yong K-T, Roy I, Mahajan SD, Ding H, Schwartz SA, Prasad PN. Bioconjugated Quantum Rods as Targeted Probes for Efficient Transmigration Across an in Vitro Blood-Brain Barrier. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:1179–1185. doi: 10.1021/bc700477u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ballou B, Lagerholm BC, Ernst LA, Bruchez MP, Waggoner AS. Noninvasive Imaging of Quantum Dots in Mice. Bioconjugate Chem. 2004;15:79–86. doi: 10.1021/bc034153y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai W, Shin DW, Chen K, Gheysens O, Cao Q, Wang SX, Gambhir SS, Chen X. Peptide-Labeled Near-Infrared Quantum Dots for Imaging Tumor Vasculature in Living Subjects. Nano Lett. 2006;6:669–676. doi: 10.1021/nl052405t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hezinger AFE, Temar J, Gopferich A. Polymer Coating of Quantum Dots - A Powerful Tool Toward Diagnostics and Sensorics. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics. 2008;68:138–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang W, Papa E, Fischer H, Mardyani S, Chan WCW. Semiconductor Quantum Dots as Contrast Agents for Whole Animal Imaging. Trends in Biotechnology. 2004;22:607–609. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson DR, Zipfel WR, Williams RM, Clark SW, Bruchez MP, Wise FW, Webb WW. Water-Soluble Quantum Dots for Multiphoton Fluorescence Imaging in Vivo. Science. 2003;300:1434–1436. doi: 10.1126/science.1083780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erogbogbo F, Yong K-T, Roy I, Xu G, Prasad PN, Swihart MT. Biocompatible Luminescent Silicon Quantum Dots for Imaging of Cancer Cells. ACS Nano. 2008;2:873–878. doi: 10.1021/nn700319z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bharali DJ, Lucey DW, Jayakumar H, Pudavar HE, Prasad PN. Folate-Receptor-Mediated Delivery of InP Quantum Dots for Bioimaging Using Confocal and Two-Photon Microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11364–11371. doi: 10.1021/ja051455x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S, Jarrett BR, Kauzlarich SM, Louie AY. Core/Shell Quantum Dots with High Relaxivity and Photoluminescence for Multimodality Imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:3848–3856. doi: 10.1021/ja065996d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahrenkiel SP, Micic OI, Miedaner A, Curtis CJ, Nedeljkovic JM, Nozik AJ. Synthesis and Characterization of Colloidal InP Quantum Rods. Nano Lett. 2003;3:833–837. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie R, Battaglia D, Peng X. Colloidal InP Nanocrystals as Efficient Emitters Covering Blue to Near-Infrared. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15432–15433. doi: 10.1021/ja076363h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamazaki K, Tanaka A, Hirata M, Omura M, Makita Y, Inoue N, Sugio K, Sigimachi K. Long Term Pulmonary Toxicity of Indium Arsenide and Indium Phosphide Instilled Intratracheally in Hamsters. Journal of Occupational Health. 2000;42:169–178. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schroeder JE, Shweky I, Shmeeda H, Banin U, Gabizon A. Folate-Mediated Tumor Cell Uptake of Quantum Dots Entrapped in Lipid Nanoparticles. Journal of Controlled Release. 2007;124:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lucey DW, MacRae DJ, Furis M, Sahoo Y, Cartwright AN, Prasad PN. Monodispersed InP Quantum Dots Prepared by Colloidal Chemistry in a Noncoordinating Solvent. Chem. Mater. 2005;17:3754–3762. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hruban RH, Maitra A, Kern SE, Goggins M. Precursors to Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 2007;36:831–849. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swierczynski SL, Maitra A, Abraham SC, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Ashfaq R, Cameron JL, Schulick RD, Yeo CJ, Rahman A, Hinkle DA, Hruban RH, Argani P. Analysis of Novel Tumor Markers in Pancreatic and Biliary Carcinomas using Tissue Microarrays. Human Pathology. 2004;35:357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Montet X, Weissleder R, Josephson L. Imaging Pancreatic Cancer with a Peptide-Nanoparticle Conjugate Targeted to Normal Pancreas. Bioconjugate Chem. 2006;17:905–911. doi: 10.1021/bc060035+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nida DL, Rahman MS, Carlson KD, Richards-Kortum R, Follen M. Fluorescent Nanocrystals for Use in Early Cervical Cancer Detection. Gynecologic Oncology. 2005;99:S89–S94. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nichols LS, Ashfaq R, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. Claudin 4 Protein Expression in Primary and Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: Support for Use as a Therapeutic Target. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:226–230. doi: 10.1309/K144-PHVD-DUPD-D401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Argani P, Rosty C, Reiter RE, Wilentz RE, Murugesan SR, Leach SD, Ryu B, Skinner HG, Goggins M, Jaffee EM, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Kern SE, Hruban RH. Discovery of New Markers of Cancer Through Serial Analysis of Gene Expression: Prostate Stem Cell Antigen is Overexpressed in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Cancer research. 2001;61:4320–4324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Argani P, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Ryu B, Rosty C, Goggins M, Wilentz RE, Murugesan SR, Leach SD, Jaffee E, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Kern SE, Hruban RH. Mesothelin is Overexpressed in the Vast Majority of Ductal Adenocarcinomas of the Pancreas: Identification of a New Pancreatic Cancer Marker by Serial Analysis of Gene Expression (SAGE) Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3862–3868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nichols LS, Ashfaq R, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. Claudin 4 Protein Expression in Primary and Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer Support for Use as a Therapeutic Target. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2004;121:226–230. doi: 10.1309/K144-PHVD-DUPD-D401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang W, Mardyani S, Fischer H, Chan CW. Design and Characterization of Lysine Cross-Linked Mercapto-Acid Biocompatible Quantum Dots. Chem. Mater. 2006;18:872–878. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang W, Singhal A, Zheng J, Wang C, Chan WCW. Optimizing the Synthesis of Red-to Near-IR-Emitting CdS-Capped CdTexSe1-x Alloyed Quantum Dots for Biomedical Imaging. Chem. Mater. 2006;18:4845–4854. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qian J, Yong KT, Roy I, Ohulchanskyy TY, Bergey EJ, Lee HH, Tramposch KM, He S, Maitra A, Prasad PN. Imaging Pancreatic Cancer Using Surface-Functionalized Quantum Dots. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:6969–6972. doi: 10.1021/jp070620n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Derfus AM, Chan WCW, Bhatia SN. Probing the Cytotoxicity of Semiconductor Quantum Dots. Nano Lett. 2004;4:11–18. doi: 10.1021/nl0347334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cho SJ, Maysinger D, Jain M, Roder B, Hackbarth S, Winnik FM. Long-Term Exposure to CdTe Quantum Dots Causes Functional Impairments in Live Cells. Langmuir. 2007;23:1974–1980. doi: 10.1021/la060093j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shiohara A, Hoshino A, Hanaki K-i, Suzuki K, Yamamoto K. On the Cyto-toxicity caused by Quantum Dots. Microbiology and Immunology. 2004;48:669–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2004.tb03478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan TT, Selvan ST, Zhao L, Gao S, Ying JY. Size Control, Shape Evolution, and Silica Coating of Near-Infrared-Emitting PbSe Quantum Dots. Chem. Mater. 2007;19:3112–3117. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akerman ME, Chan WCW, Laakkonen P, Bhatia SN, Ruoslahti E. Nanocrystal Targeting in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99:12617–12621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152463399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith AM, Duan H, Mohs AM, Nie S. Bioconjugated Quantum Dots for In Vivo Molecular and Cellular Imaging. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2008;60:1226–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim SW, Zimmer JP, Ohnishi S, Tracy JB, Frangioni JV, Bawendi MG. Engineering InAs/InP/ZnSe III-V Alloyed Core/Shell Quantum Dots for the Near-Infrared. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10526–10532. doi: 10.1021/ja0434331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zimmer JP, Kim SW, Ohnishi S, Tanaka E, Frangioni JV, Bawendi MG. Size Series of Small Indium Arsenide-Zinc Selenide Core-Shell Nanocrystals and Their Application to In Vivo Imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2526–2527. doi: 10.1021/ja0579816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Calhoun ES, Hucl T, Gallmeier E, West KM, Arking DE, Maitra A, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Chakravarti A, Hruban RH, Kern SE. Identifying Allelic Loss and Homozygous Deletions in Pancreatic Cancer without Matched Normals Using High-Density Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism Arrays. Cancer research. 2006;66:7920–7928. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]