Abstract

We report here the complete nucleotide sequence of pEntH10407 (65 147 bp), an enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli enterotoxin plasmid (Ent plasmid), which is self-transmissible at low frequency. Within the plasmid, we identified 100 open reading frames (ORFs) which could encode polypeptides. These ORFs included regions encoding heat-labile (LT) and heat-stable (STIa) enterotoxins, regions encoding tools for plasmid replication and an incomplete tra (conjugation) region. The LT and STIa region was located 13.5 kb apart and was surrounded by three IS1s and an IS600 in opposite reading orientations, indicating that the enterotoxin genes may have been horizontally transferred into the plasmid. We identified a single RepFIIA replication region (2.0 kb) including RepA proteins similar to RepA1, RepA2, RepA3 and RepA4. The incomplete tra region was made up of 17 tra genes, which were nearly identical to the corresponding genes of R100, and showed evidence of multiple insertions of ISEc8 and ISEc8-like elements. These data suggest that pEntH10407 has the mosaic nature characteristic of bacterial virulence plasmids, which contains information about its evolution. Although the tra genes might originally have rendered pEntH10407 self-transferable to the same degree as R100, multiple insertion events have occurred in the tra region of pEntH10407 to make it less mobile. Another self-transmissible plasmid might help pEntH10407 to transfer efficiently into H10407 strain. In this paper, we suggest another possibility: that the enterotoxigenic H10407 strain might be formed by auto-transfer of pEntH10407 at a low rate using the incomplete tra region.

Keywords: enterotoxin gene, pathogenicity islet, virulence plasmid

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) strains are important causes of acute and persistent diarrhoea in infants in developing countries.1–3 ETEC strains produce two kinds of classical virulence factors. One is an enterotoxin such as heat-labile (LT) or heat-stable (ST) enterotoxin, which causes diarrhoea. LT consists of two components (A and B subunits), and is immunologically, biochemically and genetically similar to cholera toxin.4,5 ST is a low-molecular-weight peptide consisting of 18 or 19 amino acids.6–8 The other major virulence factor is a colonization factor antigen (CFA), which is responsible for adhesion of bacterial cells to the intestinal epithelial cells.1,9,10

It has been reported that these classical virulence factors are carried by plasmids such as pLT (encoding LT), pST (encoding ST), pLT-ST (encoding LT and ST), pCFA (encoding CFA), pCFA-LT (encoding CFA and LT) and pCFA-ST (encoding CFA and ST).6,7,11,12 However, the full sequences of such plasmids have not been reported, with the exception of a pCFA in ETEC O6:H16.13 Among these plasmids, some families such as pLT,6 pST7,14 and pCFA13,15 have been reported to be auto-transmissible and may be evolving rapidly. Moreover, it has been reported that pLT-ST may also be self-transmissible in some serotypes of ETEC such as O78:H12, but non-self-transmissible in others such as in O78:H11.6 Therefore, it has not yet been determined whether pLT-ST has the genes required for transfer to other strains, or what other factors may render pLT-ST non-self-transmissible.

Escherichia coli H10407 (serotype O78:H11), the best characterized of the ETEC strains, was isolated from a patient with diarrhoea in Bangladesh in 1971.1,8 It has been reported previously that the original E. coli H10407 strain carries five kinds of plasmid: pCFA/I-STIb [molecular mass (MM) 62 × 106 Da)] specifying CFA/I and STIb production, pEntH10407 (MM 42 × 106 Da) specifying LT and STIa production, pTRANS (MM 42 × 106 Da) specifying self-transmission and two other plasmids (MM 3.7 × 106 and 3.8 × 106 Da) manifesting no detectable phenotype.1,6,7,11,12 It has further been reported that pTRANS promotes transfer of pCFA/I-STIb or pEntH10407 to other bacterial strains, suggesting that pCFA/I-STIb and pEntH10407 may be non-self-transmissible.12

Although the H10407 strain has been characterized in detail, there has been no report of the full sequence of the plasmids which it carries. In order to analyse the molecular evolution of pEntH10407 and to identify the factors conferring auto-transmissibility, we determined its full nucleotide sequence.

The ETEC H10407 strain maintained in our laboratory was used in these experiments. The sequenced plasmid, which will be referred to as pEntH10407K, was derived from the native plasmid pEntH10407 by an in vitro transposition system using hyperactive Tn516 (1938 bp) to provide the selectable marker of kanamycin resistance.

The fully assembled sequence of pEntH10407K (GenBank accession no. AP010910), including the kanamycin cassette, consisted of 67 094 bp, 65 147 bp of which was specific to the pEntH10407 of ETEC H10407. The average G + C content of pEntH10407 is 51.2%. The sequence assembly of pEntH10407K was confirmed by comparing the restriction-enzyme-digestion patterns predicted from the sequence with those obtained by digestion of the plasmid, using several different restriction enzymes (data not shown). We also designed a set of PCR primer pairs to amplify segments overlapped with adjacent segments at both ends, covering the entire region of pEntH10407K. All pairs of primers yielded PCR products whose sizes matched the expected sizes (data not shown). These results show that no region was inserted or omitted in our sequence assembly of pEntH10407K.

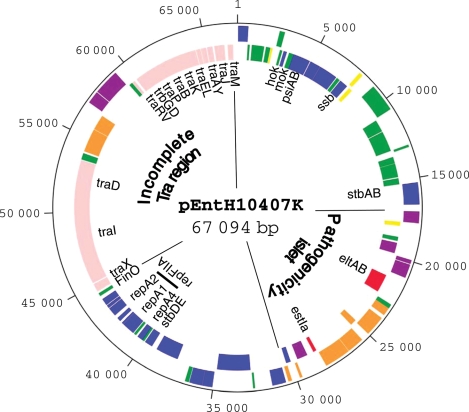

The map shown in Fig. 1 depicts pEntH10407K, a circular plasmid which consists of 67 094 bp containing 100 open reading frames (ORFs) (Table 1) and three regulatory RNA genes: sok, copA and finP. Putative functions could be assigned to 72 ORFs (72.0%); 24 ORFs were similar to conserved hypothetical proteins; the remaining 4 ORFs had no regions of significant similarity with proteins in the current database.

Figure 1.

Map of pH10407K. The sequence of pEntH10407K was determined by a whole-genome shotgun strategy. Sequence reads were assembled and gaps were closed by direct sequencing of PCR products amplified with oligonucleotide primers designed to anneal to each end of neighbouring contigs. The sequence was annotated using GenomeGambler (Xanagen Inc., Kanagawa, Japan). ORFs encoding products that were at least 50 amino acids in length were identified first; then possible ORFs were selected by combinations of database matches and by the presence of a ribosome binding site. Inner circle: ORFs, with their orientations colour-coded by functional category: red, known or putative virulence-associated proteins; pink, conjugal DNA transfer; orange, IS-related or transposase fragments; purple, intact IS or transposase; blue, plasmid replication, maintenance or other DNA metabolic functions; green, conserved hypothetical proteins; yellow, putative proteins. The outer circle shows the scale in base pairs. Nomenclature of ORFs is given in Table 1. The figure was generated using the program ‘in silico MolecularCloning GE’ (In Silico Biology, Inc., Kanagawa, Japan).

Table 1.

ORFs of pEntH10407K

| ORF | Gene | Orientationa | Position (bp) | Size (aa) | Homologue by BLAST | Identity/similarity (%) | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF001 | mltE | + | 39–641 | 200 | Lytic transglycosylase | 94/96 | ABG29580 |

| ORF002 | − | 801–667 | 44 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 100/100 | ABD60010 | |

| ORF003 | − | 1759–938 | 273 | Conserved hypothetical protein YubP | 9/99 | BAA78846 | |

| ORF004 | − | 2166–1870 | 98 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 100/100 | BAA78845 | |

| ORF005 | − | 2318–2190 | 42 | Hypothetical protein | |||

| ORF006 | ppdC | + | 2509–2826 | 105 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 91/93 | BBA97937 |

| ORF007 | − | 2971–2807 | 54 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 93/93 | EDX27828 | |

| ORF008 | hok | − | 3223–3062 | 53 | Post-segregation killing protein | 72/84 | P16077 |

| ORF009 | mok | − | 3281–3066 | 71 | Modulator of post-segregation killing protein | 50/58 | P23587 |

| ORF010 | − | 3746–3432 | 104 | Zn-dependent dehydrogenases | 99/100 | CAI79556 | |

| ORF011 | psiA | − | 4462–3743 | 239 | PsiA | 97/98 | BAA78841 |

| ORF012 | psiB | − | 4893–4459 | 144 | PsiB | 100/100 | ABD51587 |

| ORF013 | − | 5649–4948 | 233 | Predicted transcriptional regulator | 91/96 (truncated) | ABD51586 | |

| ORF014 | − | 6912–5662 | 416 | Predicted transcriptional regulator | 96/97 (truncated) | AAW58879 | |

| ORF015 | − | 7209–6976 | 77 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 98/99 | ABE10669 | |

| ORF016 | ssb | − | 7832–7266 | 188 | Ssb | 94/96 | BBA78826 |

| ORF017 | + | 7858–8094 | 78 | Hypothetical protein | |||

| ORF018 | − | 8273–8025 | 82 | Hypothetical protein | |||

| ORF019 | + | 8997–10 664 | 555 | Conserved hypothetical protein YkfC | 63/77 | ABI41559 | |

| ORF020 | − | 11 020–10 778 | 80 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 93/93 | ZP_00719262 | |

| ORF021 | − | 11 583–11 020 | 187 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 97/99 | BAF33947 | |

| ORF022 | − | 12 991–11 630 | 453 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 90/94 | BAF33946 | |

| ORF023 | + | 12 995–13 135 | 46 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 100/100 | CAP07686 | |

| ORF024 | − | 13 849–13 415 | 144 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 94/97 | BBA78815 | |

| ORF025 | − | 14 084–13 863 | 73 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 99/100 | ABE10652 | |

| ORF026 | − | 14 768–14 085 | 227 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 97/98 | AAS76 410 | |

| ORF027 | – | 15 251–14 844 | 135 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 94/97 | AAW58863 | |

| ORF028 | stbA | + | 15 284–16 246 | 320 | StbA | 99/99 | ABD59972 |

| ORF029 | stbB | + | 16 246–16 599 | 117 | StbB | 99/99 | ABD59971 |

| ORF030 | insA | + | 17 011–17 286 | 91 | InsA of IS1 | 100/100 | AAA58242 |

| ORF031 | insB | + | 17 205–17 708 | 167 | InsB of IS1 | 100/100 | AAA96694 |

| ORF032 | − | 17 982–17 719 | 87 | Hypothetical protein | |||

| ORF033 | − | 18 983–18 720 | 87 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 95/97 | AAS58634 | |

| ORF034 | insB | − | 19 618–19 115 | 167 | InsB of IS1 | 99/99 | AAA96694 |

| ORF035 | insA | − | 19 812–19 537 | 91 | InsA of IS1 | 99/100 | AAA58242 |

| ORF036 | + | 19 925–20 158 | 77 | ORF1 of IS600 | 80/80 (truncated) | ABB68584 | |

| ORF037 | + | 20 208–21 026 | 272 | ORF2 of IS600 | 99/99 | AAN43456 | |

| ORF038 | eltB | − | 21 722–21 348 | 124 | LT-B | 100/100 | AAC60441 |

| ORF039 | eltA | − | 22 549–21 719 | 276 | LT-A | 100/100 | P43530 |

| ORF040 | + | 22 812–23 084 | 90 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 99/100 | AAZ91090 | |

| ORF041 | + | 23 065–23 334 | 89 | Transposase of IS801 | 76/79 (truncated) | AAM14707 | |

| ORF042 | + | 23 250–23 564 | 104 | Transposase of IS801 | 99/99 (truncated) | AAM14707 | |

| ORF043 | + | 23 779–25 002 | 407 | Putative transposase | 99/99 (truncated) | AAT35239 | |

| ORF044 | − | 25 347–24 928 | 139 | Putative transposase | 99/99 (truncated) | CAI79504 | |

| ORF045 | + | 25 487–26 164 | 225 | ORF1 of ISEc8-like IS | 100/100 | AAW51734 | |

| ORF046 | + | 26 164–26 511 | 115 | ORF2 of ISEc8-like IS | 100/100 | AAW51735 | |

| ORF047 | + | 26 531–28 102 | 523 | ORF3 of ISEc8-like IS | 100/100 | AAW51736 | |

| ORF048 | estIa | − | 28 394–28 176 | 72 | STIa | 100/100 | P01559 |

| ORF049 | insB | − | 29 343–28 840 | 167 | InsB of IS1 | 99/99 | AAA96694 |

| ORF050 | insA | − | 29 537–29 262 | 91 | InsA of IS1 | 100/100 | AAA58242 |

| ORF051 | + | 29 641–29 796 | 51 | Putative transposase | 98/100 (truncated) | CAA07835 | |

| ORF052 | − | 30 316–30 008 | 102 | Predicted transcriptional regulator | 100/100 | ZP_00713086 | |

| ORF053 | + | 30 288–30 512 | 74 | Putative transposase | 92/94 (truncated) | AAM14707 | |

| ORF054b | + | 30 664–31 479 | 271 | Aminoglucoside 3′-phosphotransferase | 100/100 | AAA80260 | |

| ORF055 | + | 32 512–32 628 | 38 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 95/95 | ACD54240 | |

| ORF056 | baeS | − | 34 173–32 701 | 490 | BaeS | 73/86 | ABE10335 |

| ORF057 | ompR | − | 34 892–34 170 | 240 | BaeR | 83/90 | ABE10334 |

| ORF058 | ydhU | + | 35 034–35 633 | 199 | Thiosulphate reductase cytochrome B subunit | 67/82 | CAD42043 |

| ORF059 | + | 35 644–36 414 | 256 | Oxidoreductase, molybdopterin-binding subunit | 82/91 | CAD42042 | |

| ORF060 | + | 36 444–36 683 | 79 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 59/70 (truncated) | ABE10331 | |

| ORF061 | − | 39 074–37 563 | 503 | Putative ATP binding protein | 25/43 | CAD16966 | |

| ORF062 | stbE | − | 39 721–39 434 | 95 | RelE | 93/96 | ABD51640 |

| ORF063 | stbD | − | 39 969–39 718 | 83 | RelB | 100/100 | ABD51639 |

| ORF064 | − | 40 233–40 042 | 63 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 95/95 | AAL72549 | |

| ORF065 | repA4 | − | 40 370–40 185 | 61 | RepA4 | 90/93 (truncated) | BAA78895 |

| ORF066 | repA4 | − | 40 573–40 325 | 82 | RepA4 | 88/90 (truncated) | ABC42205 |

| ORF067 | − | 40 873–40 703 | 56 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 81/85 | ACD06080 | |

| ORF068 | repA1 | − | 41 793–40 936 | 285 | RepA1 | 99/100 | CAI79519 |

| ORF069 | tapA | − | 41 860–41 786 | 24 | TapA | 100/100 | BBA78893 |

| ORF070 | repA3 | − | 41 937–41 806 | 43 | RepA3 | 87/89 (truncated) | AAA26066 |

| ORF071 | repA2 | − | 42 354–42 094 | 86 | RepA2 | 99/100 | ABE10578 |

| ORF072 | − | 43 184–42 594 | 196 | Superfamily I DNA/RNA helicase | 100/100 | AAW58927 | |

| ORF073 | − | 43 430–43 227 | 67 | YmoA | 97/97 | AAO49553 | |

| ORF074 | − | 43 937–43 476 | 153 | Thermonuclease family protein | 98/98 | ABE10720 | |

| ORF075 | − | 44 394–44 182 | 70 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 100/100 | BAF33997 | |

| ORF076 | finO | − | 45 086–44 526 | 186 | FinO | 99/99 | AAC70069 |

| ORF077 | traX | − | 45 944–45 141 | 267 | TraX | 99/100 | BAF33995 |

| ORF078 | traI | − | 51 177–45 907 | 1756 | TraI | 98/99 | CAA39337 |

| ORF079 | traD | − | 53 465–51 177 | 762 | TraD | 96/96 | BAA78884 |

| ORF080 | − | 53 944–53 516 | 142 | Conserved hypothetical protein YhfA | 99/99 (truncated) | ABE10712 | |

| ORF081 | − | 55 646–54 075 | 523 | ORF3 of ISEc8-like IS | 100/100 | AAW51736 | |

| ORF082 | − | 56 013–55 666 | 115 | ORF2 of ISEc8-like IS | 100/100 | AAW51735 | |

| ORF083 | − | 56 690–56 013 | 225 | ORF1 of ISEc8-like IS | 100/100 | AAW51734 | |

| ORF084 | + | 56 910–57 311 | 133 | L0013 of ISEc8 | 99/100 | ABG71816 | |

| ORF085 | + | 57 308–57 655 | 115 | L0014 of ISEc8 | 100/100 | AAG54624 | |

| ORF086 | + | 57 705–59 243 | 512 | L0015 of ISEc8 | 99/99 | AAG54625 | |

| ORF087 | − | 59 613–59 377 | 78 | Conserved hypothetical protein YfhA | 99/99 (truncated) | ABD60024 | |

| ORF088 | traR | − | 59 827–59 606 | 73 | TraR | 99/100 | ABC42235 |

| ORF089 | traV | − | 60 477–59 962 | 171 | TraV | 98/99 | BAA78858 |

| ORF090 | trbG | − | 60 725–60 474 | 83 | TrbG | 96/98 | BAA97951 |

| ORF091 | trbD | − | 61 038–60 718 | 106 | TrbD | 89/94 | ABC42237 |

| ORF092 | traP | − | 61 612–61 025 | 195 | TraP | 96/97 | BAA78856 |

| ORF093 | traB | − | 63 032–61 581 | 483 | TraB | 99/99 | BAA78855 |

| ORF094 | traK | − | 63 760–63 032 | 242 | TraK | 99/99 | BAA78854 |

| ORF095 | traE | − | 64 313–63 747 | 188 | TraE | 99/100 | BAA78853 |

| ORF096 | traL | − | 64 646–64 335 | 103 | TraL | 99/100 | BAA97945 |

| ORF097 | traA | − | 65 026–64 661 | 121 | TraA | 96/98 | BAA78851 |

| ORF098 | traY | − | 65 453–65 058 | 131 | TraY | 100/100 | BAA97943 |

| ORF099 | traJ | − | 66 241–65 552 | 229 | TraJ | 98/99 | BAA97942 |

| ORF100 | traM | − | 66 811–66 428 | 127 | TraM | 98/100 | ABD51596 |

a+, clockwise; −, counterclockwise.

bIt originates from kanamycin resistance gene inserted in pEntH10407 to provide a selectable marker.

A total of 20 pEntH10407K ORFs (21.1%) have already been reported. These genes encode the major virulence factors accounting for LT and STIa (STp)7,17 and Tra proteins in the plasmid. The toxin region, containing the LT and STIa genes (elt and estIa), was 13 501 bp in length. This region carries three virulence-associated genes (eltAB and estIa). eltAB is 37.6% G + C and estIa is 30.1% G + C. In addition, this region is shown to contain three IS1s (IS1A, B and C), IS600 (Table 1) and an ISEc8-like element (Table 1). IS1A, IS1B and IS600 are on the same side of the toxin region and IS1C is on the other side (Table 1). The ISEc8-like element is located between eltAB and estIa. The outer end (OE) terminal inverted repeats (IR) of IS1A, IS1B and IS600 begin 4014, 1910 and 696 bp downstream of eltB, respectively, and the OE terminal IR of IS1C ends 446 bp upstream of estIa. Although IS1A, IS1B and IS600 have complete direct repeats (DR) on both sides, IS1C has DR sequences only on one side. Moreover, in this region, there were seven transposase genes between eltA and estIa, and two transposase genes were found upstream of estIa. These observations suggest that the toxin region has evolved through multiple transposition events and may have been transferred horizontally into pEntH10407 with IS1s, as predicted previously.18,19 The organization of the toxin region in pEntH10407K is suggestive of a pathogenicity islet,20 an island of small pieces of DNA (1–10 kb).

Proteins involved in plasmid replication and DNA maintenance (Table 1) are encoded by 16 ORFs (16.8% of pEntH10407K), constituting a putative replication region characteristic of IncFIIA plasmids. RepA4 (ORF065, ORF066), RepA1 (ORF068), TapA (ORF069), RepA3 (ORF070) and RepA2 (ORF071) of pEntH10407K exhibit 53.8–100.0% amino acid sequence identity with the corresponding proteins from plasmid R100.21–23 As for other IncFII replicons, a 9 bp DnaA box (TTATCCACA) and a putative origin of replication (oriR) were detected downstream of repA1 on pEntH10407K. The putative CopA antisense RNA of pEntH10407K exhibits 89.9% DNA sequence identity with the corresponding sequence of plasmid R100, which suggests that the copy number of pEntH10407 might be similar to that of R100 (NR1), i.e. one or two copies per chromosome.

Plasmid segregation systems are essential for inheritance of low-copy number plasmids in daughter cells. Sequence analysis revealed the presence of three segregation systems on pEntH10407K. The first system, designated hok/sok (bp 3062–3330), is similar to the hok/sok system of plasmid R100,24,25 the second system, designated stb (bp 15 284–16 599), is similar to the stbAB (parMRC) system of R100,26,27 and the third system, designated stbDE (bp 39 434–39 969), is similar to the stbDE system of pSS, a large virulence plasmid found in Shigella sonnei.28 The hok/sok system of R100 consists of two hok and mok genes, organized in an operon, and a locus denoted sok. Orf008 and Orf009 of pEntH10407K exhibit 70.6 and 50.0% amino acid sequence identity to Hok and Mok, respectively, of R100, and the region located upstream of hok on pEntH10407K exhibits 82.0% DNA sequence identity to the region (sok) upstream of the hok of R100. With regard to the second segregation system, StbA and StbB of pEntH10407K exhibit 99.1 and 99.1% amino acid sequence identity with StbA (ParM) and StbB (ParR), respectively, of R100, and a cis-acting site (parC) (90.4% DNA sequence identity with the corresponding sequence in R100) is present upstream of stbA on pEntH10407K. These similarities suggest that the hok/sok and stbAB systems of pEntH10407K are functional. In regard to the third segregation system, StbD and StbE of pEntH10407K exhibit 98.8 and 93.7% amino acid sequence identity with StbD and StbE, respectively, of pSS. StbDE is a novel segregational stability system that was identified on plasmid R485, which originates from Morganella morganii. Experimental data have shown that the StbE protein may be toxic to its host and that StbD is likely to be an antitoxin protein.29 This region shows high similarity to the corresponding sequence of the enteropathogenic E. coli plasmid pB171. The ORFs encoding StbD (83 aa) and StbE (95 aa) are totally identical in both nucleic acid and protein sequence to orf44 and orf43 on pB171 (accession no. AB024946). Homologues of the stbDE genes were also identified on the enterohaemorrhagic E. coli plasmid pO86A1 (pO86A1_p141 and p140 in accession no. AB255435) and on the chromosomes of some pathogenic bacteria.

Orf011 and Orf012 were found to be very similar to PsiA (97.1% amino acid sequence identity) and PsiB (99.3% amino acid sequence identity), respectively, on R100. They function as inhibitors of SOS induction in bacteria, including E. coli. Orf016 shows high identity (93.7%) at the amino acid sequence level with a single-strand DNA binding protein (SSB) of R100.

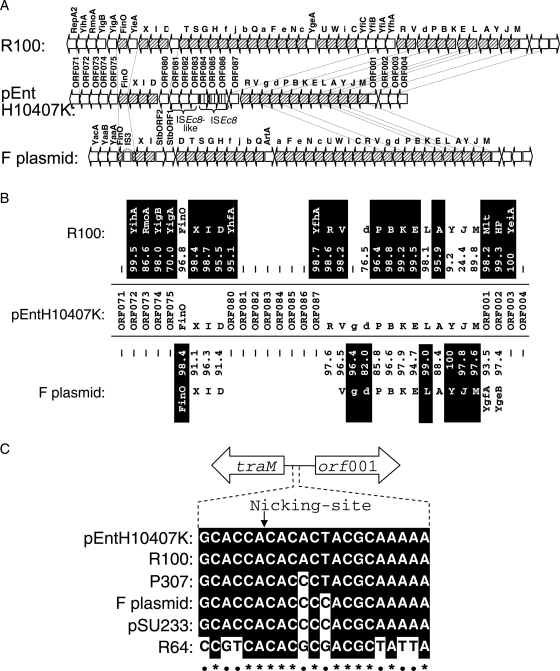

The complete tra region responsible for conjugal transfer is composed of 40 and 37 ORFs in the R100 and F plasmids,30–32 respectively. However, only 17 genes showing similarity to the tra genes of other bacteria were found in pEntH10407K. This incomplete tra region consisted of traM, traJ, traY, traA, traL, traE, traK, traB, traP, trbD, trbG, traV, traR, traD, traI, traX and finO. It contained multiple insertions of ISEc8 and ISEc8-like elements (Fig. 2A), and comprised about 50% of the complete tra operon seen in R100.32,33 The ORFs (ORF080 and ORF087) on both sides of the multiple insertions were highly homologous to YhfA and YfhA in R100, but no similar ORF was found in the F plasmid (Fig. 2A, B). Moreover, oriT, a 463-nucleotide segment located immediately upstream of traM31,32 in R100, was highly conserved in pEntH10407, having perfect identity to the nicking-site region of R100 (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Relationship of complete transfer operons of R100 and F plasmid to the incomplete operon of pEntH10407K. (A) The incomplete tra region in pEntH10407K is compared with the transfer operons of R100 and F plasmids. ORFs are orientated according to pEntH10407K. Diagonally hatched arrows indicate genes of the transfer system. tra genes are in uppercase; trb genes are in lower case. ORFs are not to scale. Although transcription proceeds from right to left in R100 and F plasmids, pEntH10407K only contains the portion of the tra region from traM to traR, which are similar to the analogous ORFs in the F plasmid, and another portion from traD to traX, which is similar to the corresponding region from traD to traX of R100. Between the two tra regions, both transposase and putative transposase genes (from ORF080 to ORF087) were recognized. (B) Per cent sequence similarity for each ORF in pEntH10407K to analogous sequences from the R100 and F plasmids. HP indicates a hypothetical protein. Values indicate identity obtained by BLASTX comparison of each pEntH10407K ORF with the corresponding ORF from R100 and F plasmids. For each pair of comparisons, the higher identity value is in the shaded box. Continuous line indicates that a similar ORF was not found. (C) Comparison of putative oriT region of conjugative plasmid aligned at nick site (arrow) according to Frost et al.32 Sequences were aligned; conserved sequence is marked with the shaded box.

In nearly all locations where the R100 and F plasmid tra genes differ, the pEntH10407K homologues more closely resembled R100. The trbG of pEntH10407K, however, had unique sequence similarity to the corresponding ORF of the F plasmid but not to that of the R100 (Fig. 2B). The other Tra proteins encoded in pEntH10407K were more similar at the amino acid sequence level to R100 proteins than F plasmid ones with the exceptions of FinO (98.4% similar to F plasmid), TrbD (82.0%), TraL (99.0%), TraY (100%), TraJ (97.8%) and TraM (97.6%) (Fig. 2B). Moreover, the 5′ end of ORF080 and the 3′ end of ORF087 were identical at the amino acid level to YhfA and YfhA, which are found in R100 and not in F, suggesting that the backbone of pEntH10407 might be close to that of R100, and that the multiple insertion events into the R100-homologous region might affect the capabilities conferred by this region, such as self-transmissibility.

We compared the self-transmissibility of pEntH10407K with that of R100 using a derivative of the E. coli K-12 strain. R100 was transferred at a frequency of 2.44 × 10−6 transconjugants per donor (Table 2). In contrast, self-transfer of pEntH10407K occurred at a very low frequency of 2.84 × 10−9 transconjugants per donor (Table 2). This value is as low as the transfer frequency reported in the conjugal plasmid R68 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.34 Parallel experiments using K-12 donor bacteria carrying pUC19 or pBluescript II SK(+) showed that these plasmids are non-self-transmissible (<10−11 transconjugants per donor for each plasmid) (Table 2). These data suggest that pEntH10407 has a low self-transmissibility. Yamamoto and Yokota12 reported that pEntH10407 did not have self-transmissibility and that pTRANS induced co-transfer of pEntH10407 and pCFA/I-STIb into the H10407 strain (O78:H11 strain). Non-piliated cells do not transfer DNA, showing that the pilus is absolutely required for conjugal DNA transfer, while mutations in the traN or traG genes drastically reduce transfer efficiency by several orders of magnitude but do not completely abolish it.32,35 TraN and TraG are thought to stabilize mating pairs through an as yet unknown mechanism.32,35 The genes that code for TraN and TraG are deleted in the incomplete tra region of pEntH10407K. As it has been reported that the products of the incomplete tra region take part in the synthesis and assembly of the sex pilus,32,33 the remaining tra genes in pEntH10407 appear to form a sex pilus which is involved in the transfer of pEntH10407. The formation of an unstable mating pair due to the deficiency of TraN and TraG might be an important cause of the low transfer efficiency in pEntH10407.

Table 2.

Transfer proficiency of pEntH10407K and the mutant plasmids

| Plasmid in donor | Relevant genotype in tra region | Transfer frequency |

|---|---|---|

| pUC19 | —a | <10−11 |

| pBluescript II SK(+) | —a | <10−11 |

| R100 | tra+b | 2.44 × 10−6 |

| pEntH10407K | traT−, traS−, traG−, traH−, trbF−, trbJ−, trbB−, traQ−, trbA−, traF−, trbE−, traN−, trbC−, traU−, traW−, trbI−, traC− | 2.84 × 10−9 |

| pEntH10407KΔtraA | traT−, traS−, traG−, traH−, trbF−, trbJ−, trbB−, traQ−, trbA−, traF−, trbE−, traN−, trbC−, traU−, traW−, trbI−, traC−, ΔtraA | <10−11 |

To evaluate the transmissibility of pEntH10407K, various plasmids [pUC19, pBluescript II SK(+), R100, pEntH10407K and mutated pEntH10407K] were electropolated into a derivative (a spontaneous nalidixic acid-resistant mutant) of the E. coli K-12 strain. The transformants were used in the experiment as donor strains. Aliquots from overnight cultures of the donor and the recipient in Luria–Bertani medium were mixed in 1:1, and incubated at 37°C for 12 h. After mating, the mixtures were diluted and spread (both diluted and undiluted) on selective agar. As controls, aliquots of the donor and recipient cultures were also spread separately on selective plates. Transfer frequencies were calculated per donor bacterium.

aNo tra region exists.

bA complete tra region is present.

About 20 genes encoded within the tra operon in R100 are thought to be necessary for conjugation to occur, since mutations in these genes abrogate a plasmid transfer. Among these genes, it is known that traA gene encodes pilus subunit, pilin, which is an essential factor for plasmid self-transmissibility in F plasmid and R100. Then, we constructed a mutant plasmid (pEntH10407KΔtraA) lacking traA of pEntH10407K by a homologous recombination method and examined the self-transmissibility of the pEntH10407KΔtraA. In the mating assay, the pEntH10407KΔtraA did not exhibit self-transmissibility (<10−11 transconjutants per donor) (Table 2). The results suggest that the traA gene is required for the self-transmissibility of pEntH10407K.

Moreover, McConnell et al.6 reported that an Ent plasmid (pEntO78:H12) from the O78:H12 strain in Bangladesh might contain both enterotoxin genes and be auto-transmissible, but that pEntH10407 (from the O78:H11 strain) might not be auto-transmissible. However, these ETEC strains were isolated also in Bangladesh and in the same period in the 1970s. In addition, the difference of the MM of pEntO78:H12 and pEntH10407 is similar to the MM of the region from traC to traT in R100. These suggest that the pLT-ST may originally have a complete set of tra genes matching those of the R100 or F plasmid, and that pEntH10407 might have been formed by multiple insertions into the tra genes to produce the sequence determined in this paper.

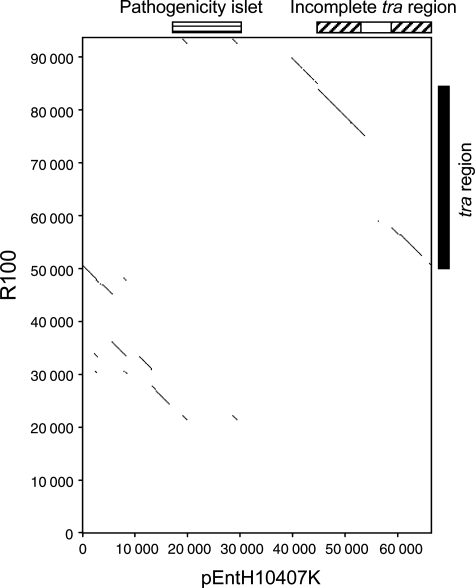

The dot matrix analysis was performed to elucidate sequence similarity between pEntH10407K and R100. This analysis indicated that the pEntH10407K shared the nucleotide sequence similarities in regions involved in plasmid replication/maintenance, and plasmid transfer (tra region) (Fig. 3). The interruption of the similarity within the incomplete tra region of pEntH10407K corresponded to the swapping of tra genes with ISEc8 and ISEc8-like elements. There was no sequence similarity in the toxin region except for IS1 sequences, which clearly indicates the presence of numerous unique ORFs including eltAB and estIa in the toxin region.

Figure 3.

Dot plot analysis for pEntH10407K versus R100. Dot matrix analysis was performed using the Harrplot 2.0 software (Software Development) with a windows setting at 15 and threshold at 10. Solid diagonal line represents similarity. The toxin region (pathogenicity islet) and the incomplete tra region of pEntH10407K are indicated by horizontally and diagonally hatched box, respectively, at the top of the dot plot. The region of the ISEc8 and ISEc8-like elements in the incomplete tra region is indicated by open box. The tra region of R100 is indicated by closed box at the right side of the dot plot.

In summary, we report the complete 67 094 bp sequence of pEntH10407K, an Ent plasmid from ETEC H10407. pEntH10407K contains three distinct major regions: (i) a pathogenicity islet containing enterotoxin genes, (ii) a region involved in plasmid replication and maintenance, and (iii) a region including tra genes that cause the self-transmissibility. Our analysis of the pEntH10407 sequence emphasizes its mosaic nature and has implications for its evolution. Self-transmissibility mediated by the incomplete tra region is retained in pEntH10407, despite the deletion of many tra genes. This finding raises the possibility that the enterotoxigenic H10407 strain might have developed due to the helper plasmid assisting in the transfer of the pEntH10407. However, our finding raises another possibility that the H10407 strain might have been born by self-transfer that occurred totally through the self-transmissibility of pEntH10 407. A comprehensive comparative analysis to clarify the evolution and diversity of Ent plasmids is currently in progress in our laboratory.

Funding

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research in the Priority Area of ‘Applied Genomics’ from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and for the Open Research Center's Project of Fujita Health University from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr H. Hirakawa, Department of Genetic Resources Technology, Faculty of Agriculture, Kyushu University, for bioinformatic analysis of pEntH10407K sequence and data handling.

Footnotes

Edited by Naotake Ogasawara

References

- 1.Evans D.G., Silver R.P., Evans D.J., Jr, Chase D.G., Gorbach S.L. Plasmid-controlled colonization factor associated with virulence in Escherichia coli enterotoxigenic for humans. Infect. Immun. 1975;12:656–67. doi: 10.1128/iai.12.3.656-667.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qadri F., Svennerholm A.M., Faruque A.S., Sack R.B. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in developing countries: epidemiology, microbiology, clinical features, treatment, and prevention. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005;18:465–83. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.3.465-483.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sack R.B., Gorbach S.L., Banwell J.G., Jacobs B., Chatterjee B.D., Mitra R.C. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from patients with severe cholera-like disease. J. Infect. Dis. 1971;123:378–85. doi: 10.1093/infdis/123.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmgren J. Actions of cholera toxin and the prevention and treatment of cholera. Nature. 1981;292:413–7. doi: 10.1038/292413a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsuji T., Taga S., Honda T., Takeda Y., Miwatani T. Molecular heterogeneity of heat-labile enterotoxins from human and porcine enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 1982;38:444–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.2.444-448.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McConnell M.M., Smith H.R., Willshaw G.A., Scotland S.M., Rowe B. Plasmids coding for heat-labile enterotoxin production isolated from Escherichia coli O78: comparison of properties. J. Bacteriol. 1980;143:158–67. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.1.158-167.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moseley S.L., Samadpour-Motalebi M., Falkow S. Plasmid association and nucleotide sequence relationships of two genes encoding heat-stable enterotoxin production in Escherichia coli H-10407. J. Bacteriol. 1983;156:441–3. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.1.441-443.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith H.W., Gyles C.L. The relationship between two apparently different enterotoxins produced by enteropathogenic strains of Escherichia coli of porcine origin. J. Med. Microbiol. 1970;3:387–401. doi: 10.1099/00222615-3-3-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaastra W., Svennerholm A.M. Colonization factors of human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:444–52. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)10068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith H.R., Willshaw G.A., Rowe B. Mapping of a plasmid, coding for colonization, factor antigen I and heat-stable enterotoxin production, isolated from an enterotoxigenic strain of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1982;149:264–75. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.1.264-275.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willshaw G.A., Barclay E.A., Smith H.R., McConnell M.M., Rowe B. Molecular comparison of plasmids encoding heat-labile enterotoxin isolated from Escherichia coli strains of human origin. J. Bacteriol. 1980;143:168–75. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.1.168-175.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamoto T., Yokota T. Plasmids of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli H10407: evidence for two heat-stable enterotoxin genes and a conjugal transfer system. J. Bacteriol. 1983;153:1352–60. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.3.1352-1360.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Froehlich B., Parkhill J., Sanders M., Quail M.A., Scott J.R. The pCoo plasmid of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli is a mosaic cointegrate. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:6509–16. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.18.6509-6516.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wachsmuth I.K., Falkow S., Ryder R.W. Plasmid-mediated properties of a heat-stable enterotoxin-producing Escherichia coli associated with infantile diarrhea. Infect. Immun. 1976;14:403–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.14.2.403-407.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Froehlich B., Holtzapple E., Read T.D., Scott J.R. Horizontal transfer of CS1 pilin genes of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:3230–7. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.10.3230-3237.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goryshin I.Y., Reznikoff W.S. Tn5 in vitro transposition. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:7367–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto T., Tamura T., Yokota T. Primary structure of heat-labile enterotoxin produced by Escherichia coli pathogenic for humans. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:5037–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto T., Gojobori T., Yokota T. Evolutionary origin of pathogenic determinants in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae O1. J. Bacteriol. 1987;169:1352–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.3.1352-1357.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto T., Yokota T. Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin genes are flanked by repeated deoxyribonucleic acid sequences. J. Bacteriol. 1981;145:850–60. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.2.850-860.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gal-Mor O., Finlay B.B. Pathogenicity islands: a molecular toolbox for bacterial virulence. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1707–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang T., Min Y.N., Liu W., Womble D.D., Rownd R.H. Insertion and deletion mutations in the repA4 region of the IncFII plasmid NR1 cause unstable inheritance. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:5350–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5350-5358.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosen J., Ryder T., Inokuchi H., Ohtsubo H., Ohtsubo E. Genes and sites involved in replication and incompatibility of an R100 plasmid derivative based on nucleotide sequence analysis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1980;179:527–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00271742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.del Solar G., Giraldo R., Ruiz-Echevarria M.J., Espinosa M., Diaz-Orejas R. Replication and control of circular bacterial plasmids. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1998;62:434–64. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.434-464.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerdes K., Bech F.W., Jorgensen S.T., et al. Mechanism of postsegregational killing by the hok gene product of the parB system of plasmid R1 and its homology with the relF gene product of the E. coli relB operon. EMBO J. 1986;5:2023–9. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04459.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thisted T., Sorensen N.S., Wagner E.G., Gerdes K. Mechanism of post-segregational killing: Sok antisense RNA interacts with Hok mRNA via its 5′-end single-stranded leader and competes with the 3′-end of Hok mRNA for binding to the mok translational initiation region. EMBO J. 1994;13:1960–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06465.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen R.B., Gerdes K. Mechanism of DNA segregation in prokaryotes: ParM partitioning protein of plasmid R1 co-localizes with its replicon during the cell cycle. EMBO J. 1999;18:4076–84. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen R.B., Lurz R., Gerdes K. Mechanism of DNA segregation in prokaryotes: replicon pairing by parC of plasmid R1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:8550–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang Y., Yang F., Zhang X., et al. The complete sequence and analysis of the large virulence plasmid pSS of Shigella sonnei. Plasmid. 2005;54:149–59. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayes F. A family of stability determinants in pathogenic bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:6415–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6415-6418.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anthony K.G., Klimke W.A., Manchak J., Frost L.S. Comparison of proteins involved in pilus synthesis and mating pair stabilization from the related plasmids F and R100-1: insights into the mechanism of conjugation. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:5149–59. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5149-5159.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brinkley C., Burland V., Keller R., et al. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli adherence factor plasmid pMAR7. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:5408–13. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01840-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frost L.S., Ippen-Ihler K., Skurray R.A. Analysis of the sequence and gene products of the transfer region of the F sex factor. Microbiol. Rev. 1994;58:162–210. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.2.162-210.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawley T.D., Klimke W.A., Gubbins M.J., Frost L.S. F factor conjugation is a true type IV secretion system. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003;224:1–15. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Genthner F.J., Chatterjee P., Barkay T., Bourquin A.W. Capacity of aquatic bacteria to act as recipients of plasmid DNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1988;54:115–7. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.1.115-117.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klimke W.A., Frost L.S. Genetic analysis of the role of the transfer gene, traN, of the F and R100-1 plasmids in mating pair stabilization during conjugation. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:4036–43. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.16.4036-4043.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]