Abstract

Protein kinase Cι (PKCι) promotes non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by binding to Par6α and activating a Rac1-Pak-Mek1,2-Erk1,2 signaling cascade. The mechanism by which the PKCι-Par6α complex regulates Rac1 is unknown. Here we show that Ect2, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for Rho family GTPases, is coordinately amplified and overexpressed with PKCι in NSCLC tumors. RNAi-mediated knock down of Ect2 inhibits Rac1 activity and blocks transformed growth, invasion and tumorigenicity of NSCLC cells. Expression of constitutively active Rac1 (RacV12) restores transformation to Ect2-deficient cells. Interestingly, the role of Ect2 in transformation is distinct from its well-established role in cytokinesis. In NSCLC cells, Ect2 is mislocalized to the cytoplasm where it binds the PKCι-Par6α complex. RNAi-mediated knock down of either PKCι or Par6α causes Ect2 to redistribute to the nucleus, indicating that the PKCι-Par6α complex regulates the cytoplasmic localization of Ect2. Our data indicate that Ect2 and PKCι are genetically and functionally linked in NSCLC, acting to coordinately drive tumor cell proliferation and invasion through formation of an oncogenic PKCι-Par6α-Ect2 complex.

Keywords: gene amplification, anchorage-independent growth, invasion, Rac1, Mek-Erk signaling, cytokinesis

Introduction

Epithelial cell transforming sequence 2 (Ect2) is a GEF for Rho family GTPases that functions in cytokinesis (Hara et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2005; Niiya et al., 2006; Niiya et al., 2005; Tatsumoto et al., 1999). Ect2 is comprised of a C-terminal GEF domain, and an N-terminal regulatory domain that modulates Ect2 activity and localization (Kim et al., 2005). Ectopic expression of the Ect2 GEF domain causes transformation in mouse fibroblasts whereas full length Ect2 does not (Miki et al., 1993; Saito et al., 2004). The relevance of this observation to human cancer is unclear. Human cancers express only full length Ect2, indicating that the transforming C-terminal Ect2 fragment is not relevant to human cancer (Saito et al., 2003). Paradoxically, Ect2 is overexpressed in some human tumors (Hirata et al., 2009; Salhia et al., 2008; Sano et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2008) and transient Ect2 knock down (KD) induces transitory cell cycle arrest in vitro, indicating a possible role for Ect2 in tumor cell growth (Hirata et al., 2009). However, the mechanism of Ect2 involvement in human tumorigenesis remains unresolved.

Here we report a novel genetic, biochemical and functional link between Ect2 and the PKCι oncogene. Ect2 and PKCι are coordinately overexpressed in primary NSCLC tumors as a consequence of tumor-specific co-amplification of the ECT2 and PRKCI genes. Furthermore, Ect2 is required for transformed growth and invasion of NSCLC cells in vitro and tumorigenicity in vivo. The role of Ect2 in transformation is distinct from its well-characterized function in cytokinesis. Ect2 mis-localizes to the cytoplasm of NSCLC cells where it binds the oncogenic PKCι-Par6α complex and activates Rac1. Furthermore, the PKCι-Par6α complex regulates the cytoplasmic mis-localization and oncogenic function of Ect2. Thus Ect2 and PKCι are genetically linked by co-amplification, and functionally linked through their physical association in an oncogenic PKCι-Par6α-Ect2 complex that drives transformation through Rac1.

Materials and Methods

Antibody Reagents and Cell Lines

Antibodies used: Ect2, RhoA and CD31/Pecam-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); PKCι, Rac1 and Cdc42 (BD Transduction Labs, San Jose, CA); β-actin, PARP/cleaved PARP, MEK1/2, p298-MEK1/2, ERK, pThr202/Tyr204ERK and Lamin A/C (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA); FLAG epitope (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO); BrdU (DAKO, Carpenteria, CA). Phalloidin-Alexa Fluor 594 and anti-Rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 were from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA and terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling staining (TUNEL) kit from Promega BioSciences, San Luis Obispo, CA. A427, A549, H358, H460, H1703 and Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA).

Human Primary NSCLC Sample Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from primary NSCLC tumors and matched normal lung using RNAqueous 4PCR (Ambion, Austin, TX). Ect2 and PKCι mRNA abundance was determined by Taqman quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) on an Applied Biosystems 7900HT sequence analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using 18S for normalization. Primer/probe sets are listed in Supplementary Figure 1A. Genomic DNA was isolated from primary NSCLC tumors and matched normal lung by phenol/chloroform extraction and ECT2 and PRKCI gene copy number was determined by qPCR using the RNASEP1 gene for normalization. Primer/probe sets are listed in Supplementary Figure 1A. Statistical analyses were performed using the two tailed Student's t test and R2 using Pearson correlation analysis.

Tissue microarrays of primary NSCLC and matched normal lung were analyzed for Ect2 protein by immunohistochemistry using the Envision Plus Dual Labeled Polymer Kit (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA). Specificity was determined by incubating primary Ect2 antibody with a 10-fold excess of Ect2 peptide. Images were captured and analyzed using an Aperio ScanScope scanner and ImageScope software (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA).

Lentiviral RNAi constructs, Cell Transduction and Immunoblot Analysis

Lentiviral RNAi against human Ect2, PKCι, and Par6α were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Mission shRNA library (St Louis, MO, USA) and packaged into recombinant lentiviruses as described previously (Frederick et al., 2008). A non-target lentiviral RNAi (NT-RNAi) that does not recognize any human or canine genes was used as a negative control. RNAi target sequences are listed in Supplemental Figure 1B. Stably transduced cell populations were generated as described previously (Frederick et al., 2008).

Ect2, PKCι, and Par6α RNAi constructs were analyzed for efficiency of target gene knockdown (KD) by qPCR (Supplemental Figure 1A). NT, Ect2 and PKCι KD cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis as described previously (Regala et al., 2005a).

Plasmids, Transfections and Immunoprecipitations

Cells were transfected with pEGFP-C1 containing RNAi resistant, full-length human Ect2 or empty pEGFP-C1 plasmid (Clonotech, Mountain View, CA) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The Ect2 cDNA was rendered RNAi-resistant by introducing silent mutations that disrupt the Ect2-RNAi target site as described previously (Frederick et al., 2008). In some experiments, cells were stably transfected with LZRS containing Myc-tagged RacV12 or empty LZRS retroviral vector as described previously (Frederick et al., 2008). Cells stably transfected with Flag-tagged full-length RNAi-resistant wild-type human Par6α, K19A Par6α mutant (Par6α-K19A), wild-type PKCι, D63A PKCι mutant (PKCι-D63A) or empty vector were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis as described previously (Frederick et al., 2008).

Soft Agar Growth, Cellular Invasion and Population Doubling Time Analysis

Anchorage-independent growth and invasion were assayed as described previously (Frederick et al., 2008; Regala et al., 2005a). Population-doubling time (PDT) was determined during logarithmic growth phase in six-well tissue culture plates (Corning Costar, Corning, NY) (2×104 cells/well) using the formula PDT= ln2t/ln(N/No) (N= final cell number, No= initial cell number and t= time between No and N). Experiments were independently performed at least three times.

Rac1, Cdc42 and RhoA Activity Assays

Rho GTPase activity was determined by affinity pulldown as described previously (Frederick et al., 2008; Zhang, 2004). Densitometry was performed using Kodak Molecular imaging software (Carestream Molecular Imaging, New Haven, CT). Results were normalized to total Rho GTPase.

Tumorigenicity in Nude Mice

A549 NT and Ect2 KD cells were grown subcutaneously in athymic nude mice (Harlan-Sprague-Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) as described previously (Regala et al., 2005a). Tumor volume, BrdU labeling, immunohistochemical and immunoblot analyses were performed as described previously (Regala et al., 2005a). Ect2, Mek1,2, p298-Mek1,2, Erk1,2, p-Erk1,2, PARP/cleaved PARP and β-actin antibodies were used at 1:1000. Images were captured and analyzed using Aperio ScanScope scanner and software (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA, USA).

Confocal Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Cells grown on glass chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, permeabilized in 0.2% (v/v) Triton X-100, incubated in PBS containing 3% BSA for 30 min, and incubated with phalloidin antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 (1:500) for 2 h at RT. Slides were mounted in medium containing 1.5 μg/mL 4′,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for confocal fluorescence microscopy (Vectashield: Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Ten representative fields were photographed at 40× and >1,000 cells from each cell type were analyzed for multiple nuclei. Experiments were independently repeated three times.

Cells grown on glass chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL), were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated overnight at 4°C with Ect2 antibody (1:500), followed by incubation with anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 (1:500) for 2 h at RT. Cells were mounted in medium containing DAPI and subjected to confocal fluorescence microscopy (Vectashield: Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Cells were photographed with a Zeiss LSM 510 meta confocal microscope and imaging software (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Maple Grove, MN), using a EC Plan-Neofluar 40× oil immersion objective (1.3 numeric aperture). DAPI was detected with a Diode 405-430 laser at 405 nm using a 420 nm long-pass filter. Ect2 was detected with a HeNe laser at 594 nm using a 615 nm long-pass filter.

Subcellular Fractionation

Cells were fractionated using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). Total, nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were subjected to immunoblot analysis using antibodies to Ect2, Lamin A/C, Mek1/2 and PKCι (all at 1:1000), HRP-labeled secondary antibodies and ECL detection. Ect2 levels were determined by densitometry and expressed as % total cellular Ect2. The experiments were independently conducted three times.

Results

Ect2 and PKCι are coordinately amplified and overexpressed in primary NSCLC tumors

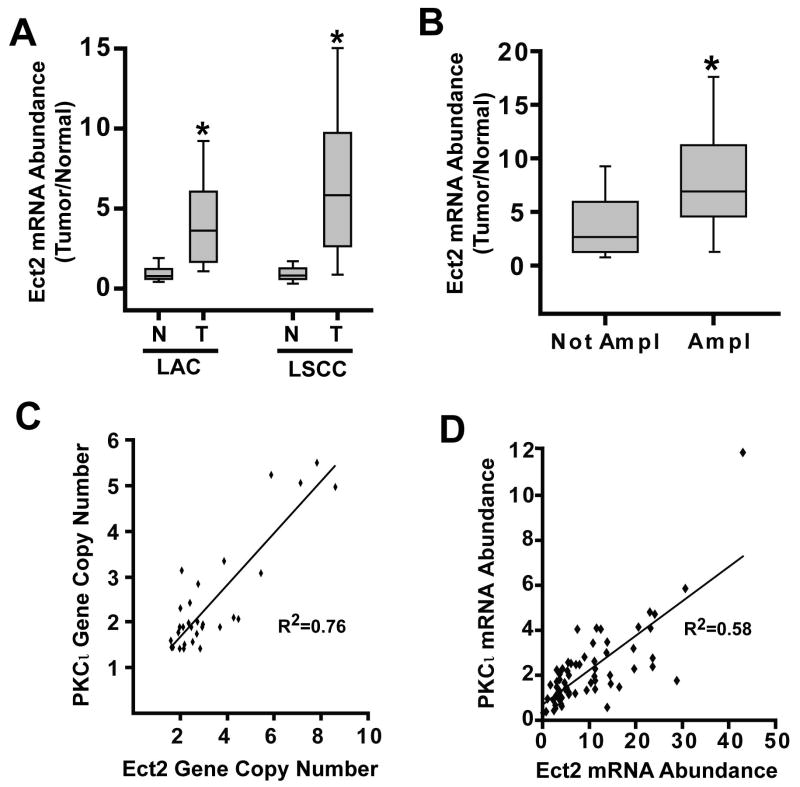

The gene encoding Ect2 resides on chromosome 3q26, a region frequently amplified in LSCC (Balsara et al., 1997; Brass et al., 1996; Sugita et al., 2000). To assess Ect2 expression, we analyzed 137 primary lung tumors [68 lung adenocarcinoma (LAC) and 69 lung squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC)] and matched normal lung by qPCR. Ect2 mRNA was significantly higher in LAC (mean 4.6 fold increase; p<0.0001) and LSCC (mean 6.8 fold increase; p<0.0001) tumors than matched normal lung (Figure 1A). Elevated Ect2 mRNA (defined as >2 standard deviations above the mean Ect2 mRNA value of matched normal lung) was observed in 113/137 (82%) of NSCLC tumors and was equally prevalent in LAC and LSCC.

Figure 1. Ect2 and PKCι are coordinately amplified and over-expressed in primary NSCLC tumors.

Ect2 is over-expressed in primary lung adenocarcinoma (LAC) and squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) (A). 68 LAC cases, 69 LSCC cases and matched normal control lung tissues were analyzed by qPCR for Ect2 mRNA abundance. Ect2 mRNA is significantly higher in LAC and LSCC tumor samples than in matched normal lung (*p<0.0001 and p<0.0001 respectively). (B) ECT2 gene amplification drives Ect2 expression in LSCC. LSCC tumors were analyzed for ECT2 gene copy number as described in Materials and Methods. Tumors harboring ECT2 gene amplification express higher Ect2 mRNA than tumors without ECT2 amplification (*p< 0.001). (C) ECT2 and PRKCI are co-amplified in LSCC. ECT2 and PRKCI gene copy number exhibit a significant correlation in NSCLC tumors (N= 94; R2= 0.76; *p<0.00001). (D) Ect2 and PKCι mRNA are coordinately over-expressed in LSCC tumors harboring gene amplification (n=67; R2=0.52; *p<0.00001).

We next assessed ECT2 copy number. 67 of 94 (71%) LSCC tumors exhibited ECT2 amplification (defined as a gain of 1 or more ECT2 alleles). Analysis of 40 LAC tumors revealed no increase in ECT2 copy number (data not shown), consistent with the restricted distribution of 3q26 amplification to LSCC tumors (Balsara et al., 1997; Brass et al., 1996; Sugita et al., 2000). LSCC tumors harboring ECT2 amplification showed significantly higher Ect2 mRNA than tumors lacking amplification (p<0.001) (Figure 1B). PRKCI is adjacent to ECT2 on chromosome 3q26 and is a target of frequent tumor-specific gene amplification in LSCC tumors (Regala et al., 2005b). ECT2 copy number showed a statistically significant, positive correlation with PRKCI copy number (Figure 1C, R2 of 0.76, p<0.00001). In addition, PKCι and Ect2 mRNA expression correlate in LSCC harboring 3q26 gene amplification (Figure 1D; R2 of 0.58, p<0.00001). Thus, ECT2 and PRKCI are co-amplified, and coordinately overexpressed in LSCC tumors.

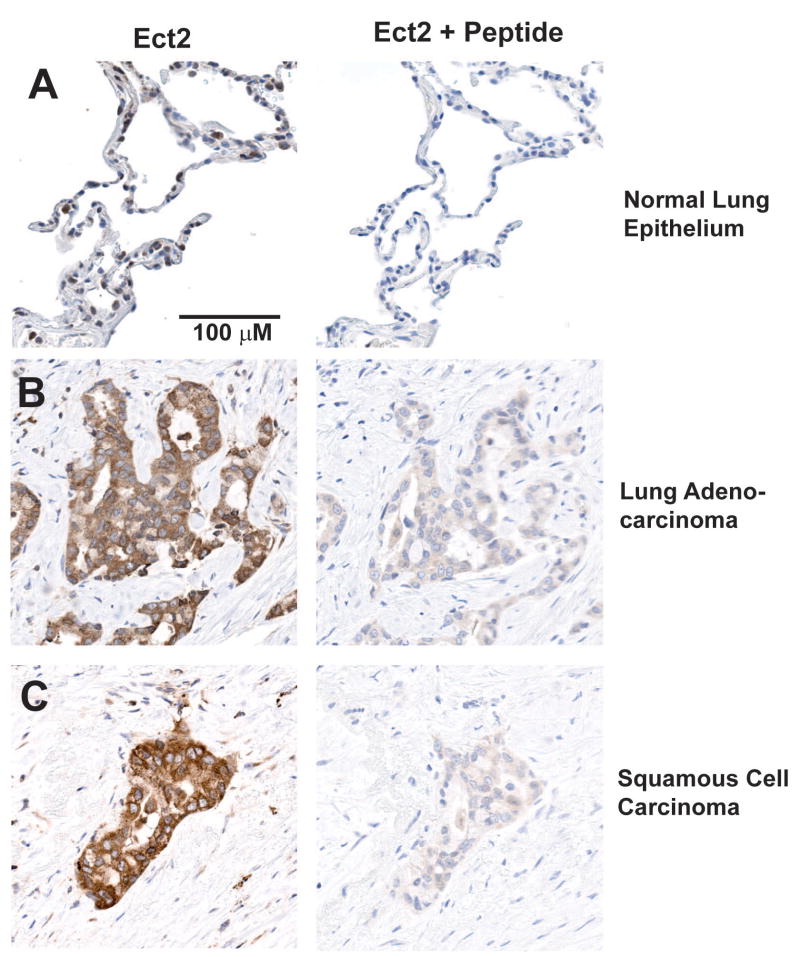

Immunohistochemical analysis reveals that Ect2 is restricted to the nucleus of normal lung epithelial cells (Figure 2A, left panel). In contrast, LAC and LSCC tumors display increased Ect2 staining in the cytoplasm (Figure 2B and C, left panels). Staining specificity was confirmed using a 10-fold excess of recombinant Ect2 peptide in the antibody solution which significantly inhibited Ect2 staining (Figure 2A-C, right panels). Analysis of 68 primary NSCLC tumors (36 LSCC and 32 LAC) revealed elevated cytoplasmic Ect2 staining in 57/68 or ∼84% of tumors, demonstrating that Ect2 protein is frequently overexpressed in NSCLC tumors.

Figure 2. Ect2 is over-expressed and mis-localized to the cytoplasm in primary NSCLC tumors.

Immunohistochemical localization of Ect2 in normal lung epithelium (A), lung adenocarcinoma (LAC) (B) and lung squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) (C) was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Ect2 localizes predominantly to the nucleus of normal lung epithelial cells (A). Ect2 is over-expressed in both LAC (B) and LSCC (C) tumors and is mis-localized to the cytoplasm of tumor cells. Ect2 staining specificity was confirmed using an excess of Ect2 peptide in the antibody solution (A-C, Ect2 + peptide).

Ect2 is required for anchorage-independent growth and invasion of NSCLC cells

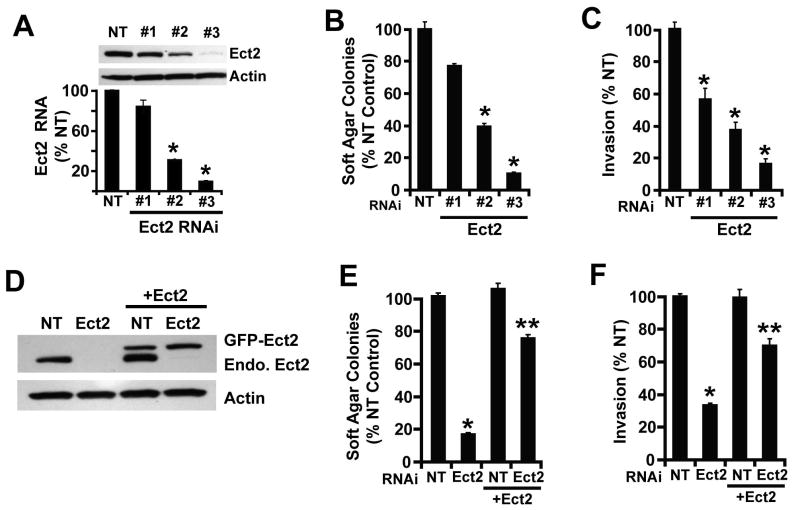

We next assessed whether Ect2 plays a role in the transformed phenotype of NSCLC cells. H1703 LSCC cells were analyzed because they harbor ∼4-fold increase in ECT2 copy number and expresses abundant Ect2 protein. Cells were stably transduced with three lentiviral Ect2 RNAi constructs and a non-target RNAi (NT) control lentivirus, and cell populations were assessed for Ect2 mRNA abundance and protein expression (Figure 3A). Each of the three Ect2 RNAi constructs induced a commensurate reduction in Ect2 mRNA and protein when compared to NT cells (Figure 3A). Functionally, Ect2 KD cells exhibited impaired anchorage-independent growth (Figure 3B) and invasion (Figure 3C) commensurate with the level of Ect2 KD. To confirm this cellular phenotype is due to Ect2 KD, we expressed RNAi-resistant, GFP-tagged Ect2 in NT and Ect2 KD cells (Figure 3D). Exogenous Ect2 significantly restored anchorage-independent growth (Figure 3E) and invasion (Figure 3F) in Ect2 KD cells but had no effect on NT cells. We also analyzed a panel of four cell lines representing major subtypes of NSCLC; LAC (A549 and H358), large cell lung carcinoma (H460) and LSCC (A427) (Supplemental Figure 2). Each cell line exhibited a significant inhibition of anchorage-independent growth and invasion after Ect2 KD indicating that Ect2 is important for transformation in many NSCLC cell lines.

Figure 3. Ect2 is important for anchorage-independent growth and invasion of NSCLC cells.

H1703 cells were infected with one of three recombinant lentiviruses containing RNAi targeting Ect2 (Ect2-RNAi #1-3) or a non-target (NT) sequence. Cell populations stably transduced with each RNAi were isolated and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Cells expressing Ect2-RNAi or NT-RNAi constructs were assessed for Ect2 mRNA abundance by qPCR and Ect2 protein by immunoblot analysis. Cells expressing Ect2-RNAi or NT-RNAi were analyzed for anchorage-independent growth in soft agar (B) and cellular invasion through Matrigel-coated chambers (C). Ect2-RNAi (construct #3) and NT-RNAi cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing GFP-Ect2 (+Ect2) or a control empty plasmid and assessed for GFP-Ect2 and endogenous Ect2 expression by immunoblot analysis (D). Cells from (D) were assessed for anchorage-independent growth in soft agar (E) and invasion (F). Data in panels A-C, E and F are expressed as % NT control and represent the mean +/- SEM; n=3. * denotes a statistically significant difference from NT; ** denotes a statistically significant difference from Ect2 KD cells in the absence of GFP-Ect2, p<0.05)

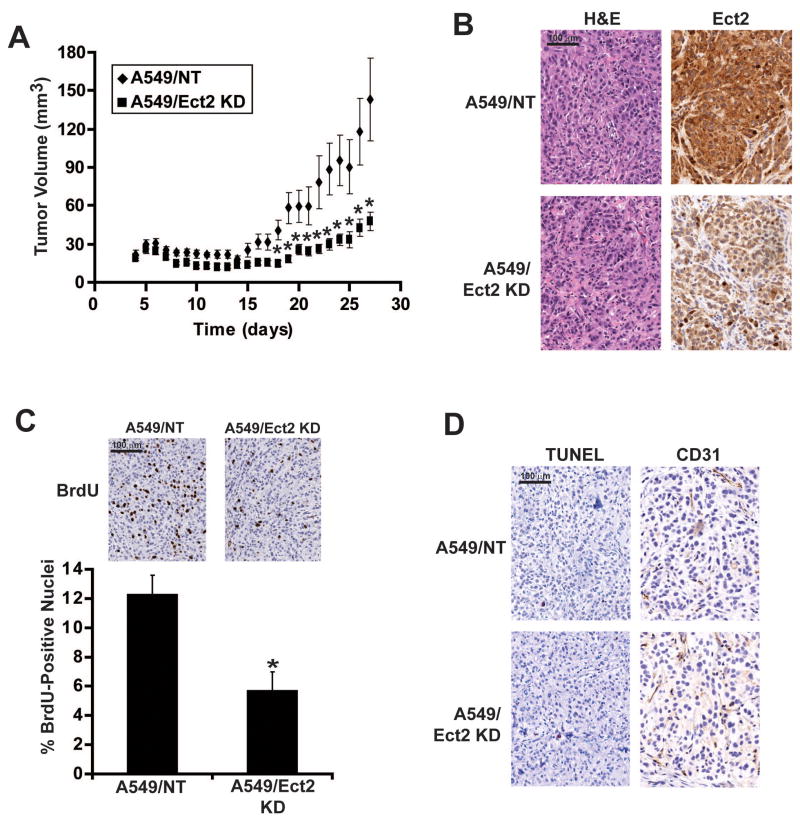

Ect2 is important for NSCLC tumorigenicity in vivo

We next assessed the role of Ect2 in NSCLC tumorigenicity in vivo. A549 cells were chosen because they grow as subcutaneous tumors with well-established growth kinetics. A549/Ect2 KD and A549/NT cells were injected subcutaneously into the flanks of athymic nude mice and tumor growth was monitored over 4 weeks. A549/Ect2 KD cells exhibited impaired tumor growth when compared to A549/NT cells (Figure 4A). Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed reduced Ect2 expression in A549/Ect2 KD tumors (Figure 4B). A549/Ect2 KD tumors exhibited a significant 2.3 fold reduction in labeling index (defined as BrdU-labeled nuclei/total nuclei) compared to A549/NT tumors (Figure 4C). In contrast, A549/NT and A549/Ect2 KD tumors exhibited no significant difference in TUNEL-positive nuclei (0.19 +/-0.05% in A549/NT tumors versus 0.19 +/-0.09% in A549/Ect2 KD tumors; p>0.97) or CD31 staining (Figure 4D) indicating that Ect2 KD primarily affects tumor cell proliferation.

Figure 4. Ect2 is required for NSCLC tumorigenicity in vivo.

A549/NT and A549/Ect2 KD cells were injected subcutaneously into the flanks of nude mice and tumor volumes were determined over a four week period as described in Materials and Methods. (A) A549/Ect2 KD tumors grow significantly slower than A549/NT cell tumors. *indicates a statistically significant difference between A549/NT and A549/Ect2 KD tumor volumes at the indicated time points (p<0.05). (B) A549/NT and A549/Ect2 KD tumors stained with hematoxylin and eosin or Ect2 by immunohistochemistry. Ect2 expression is diminished in A549/Ect2 KD tumors. (C) BrdU staining of A549/NT and A549/Ect2 KD tumors (inset). BrdU-positive nuclei were counted as described in Materials and Methods. A549/Ect2 KD tumors exhibit a statistically significant decreased in BrdU labelling index when compared to A549/NT tumors (*p<0.05). (D) A549/NT and A549/Ect2 KD tumors exhibited no differences in TUNEL or CD31 staining.

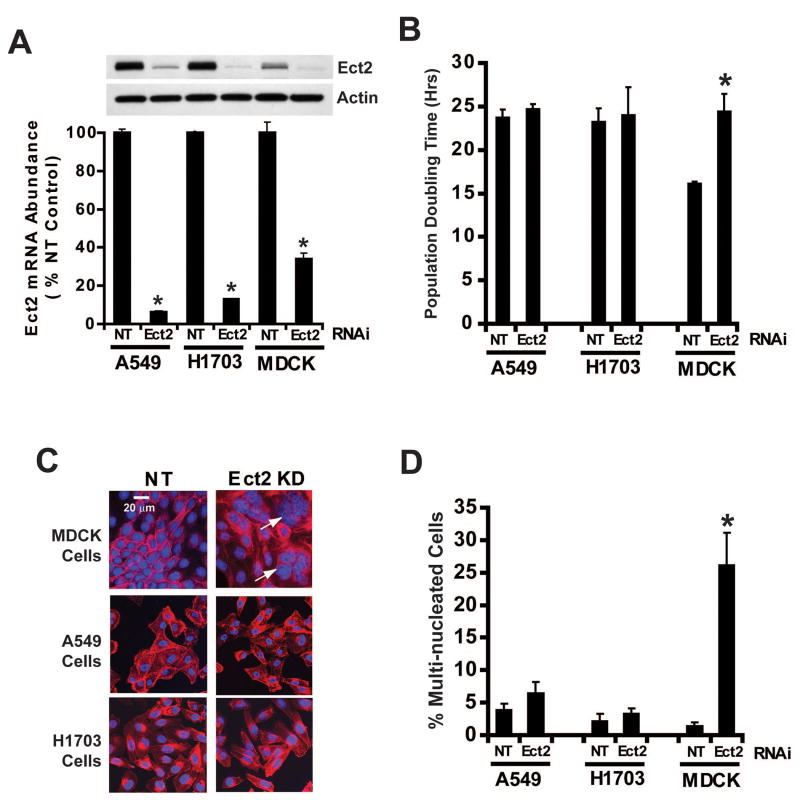

Ect2 KD does not induce cytokinesis defects in NSCLC cells

A major physiologic function of Ect2 is the regulation of cytokinesis (Hara et al., 2006; Niiya et al., 2005; Tatsumoto et al., 1999). Ect2 KD in non-transformed cells leads to a cytokinesis defect characterized by decreased cell growth and accumulation of multinucleated cells (Tatsumoto et al., 1999). To determine if Ect2 KD in NSCLC cells affects cytokinesis, A549, H1703, and MDCK cells were stably transduced with either Ect2 or NT RNAi. The target sequence of Ect2 RNAi construct #3 is conserved between human and canine Ect2 resulting in efficient Ect2 KD in all three cell lines (Figure 5A). As expected, MDCK/Ect2 KD cells exhibited an increased population doubling time (PDT) compared to MDCK/NT cells (Figure 5B). In contrast, neither A549/Ect2 KD nor H1703/Ect2 KD cells showed a significant change in PDT compared to their NT cells (Figure 5B). Furthermore, MDCK/Ect2 KD cell cultures exhibited an accumulation of large, multinucleated cells which was not observed in A549/Ect2 KD or H1703/Ect2 KD cell cultures (Figure 5C). Quantitative analysis revealed a 12-fold increase in multi-nucleated cells in MDCK/Ect2 KD cultures but no significant change in A549/Ect2 KD or H1703/Ect2 KD cultures when compared to their respective NT cell cultures (Figure 5D). We also observed no accumulation of multinucleated cells in A549/Ect2 KD tumors in vivo (1.3 +/-0.10% in A549/NT cells versus 1.3 +/- 0.15% in A549/Ect2 KD cells; p=0.98, n=>500 cells counted/tumor). These data indicate that the role of Ect2 in transformation is distinct from its role in cytokinesis.

Figure 5. Ect2 KD does not induce cytokinesis defects in NSCLC cells.

(A) RNAi-mediated knock down of Ect2 expression in A549, H1703 and MDCK cells. A549/Ect2 KD, A549/NT, H1703/Ect2 KD, H1703/NT, MDCK/Ect2 KD and MDCK/NT cells were analyzed for Ect2 mRNA and Ect2 protein. (B) Ect2 KD causes an increase in population doubling time in MDCK cells, but not A549 or H1703 cells. Population doubling times were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as mean doubling time in hours +/-SEM; n=3; *p<0.05. (C) Ect2 KD induces accumulation of multi-nucleated cells in MDCK but not A549 or H1703 cells. Cells were stained with phalloidin and DAPI and analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy as described in Materials and Methods. Arrows indicate multi-nucleated cells in MDCK/Ect2 KD cultures. (D) Quantitative analysis of multi-nucleated cells. At least 1,000 cells were counted from each cell line in each of three independent experiments. Data are expressed as % multi-nucleated cells +/- SEM. * indicates a statistically significant difference from MDCK/NT cells; p<0.02, n=3.

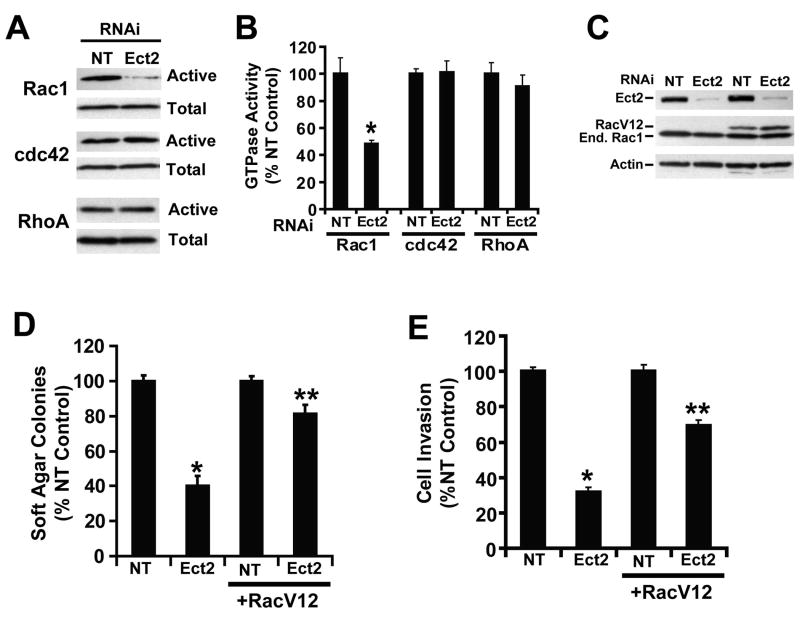

Ect2 regulates Rac1 activity in NSCLC cells

Since Ect2 can regulate the activity of the Rho GTPases Rac1, Cdc42 and RhoA in vitro (Miki et al., 1993), we assessed Rho GTPase activity in H1703/Ect2 KD and H1703/NT cells. Ect2 KD cells exhibited decreased Rac1 activity but no change in Cdc42 or RhoA activity compared to NT cells (Figure 6A). Quantitative analysis revealed a significant ∼50% inhibition in Rac1 activity in Ect2 KD cells (Figure 6B). Furthermore, expression of a constitutively active Rac1 allele (RacV12) in H1703/Ect2 KD and H1703/NT cells (Figure 6C) restored anchorage-independent growth and invasion in Ect2 KD cells while having no effect in NT cells (Figure 6D and E). Similar results were observed in A549 cells (data not shown).

Figure 6. Rac1 is an effector of Ect2-mediated transformation in NSCLC cells.

(A) Ect2 KD inhibits Rac1, but not Cdc42 or RhoA activity. Representative immunoblots of active and total Rac1, Cdc42 and RhoA in H1703 NT and Ect2 KD cells. (B) Quantitative analysis of Rac1, Cdc42 and RhoA activity in H1703 NT and Ect2 KD cells. Data are expressed as % NT control +/-SEM (*p<0.05, n=3). (C) Expression of constitutively active Rac1 (RacV12) in H1703/NT and H1703/Ect2 KD cells. (D) Reconstitution of anchorage independent soft agar growth in H1703/Ect2 KD cells by a RacV12 (*p<0.05, n=5). (E) Reconstitution of cellular invasion in H1703/Ect2 KD cells by RacV12 (*p<0.05, n=4). Data in D and E are expressed as % NT control +/-SEM.

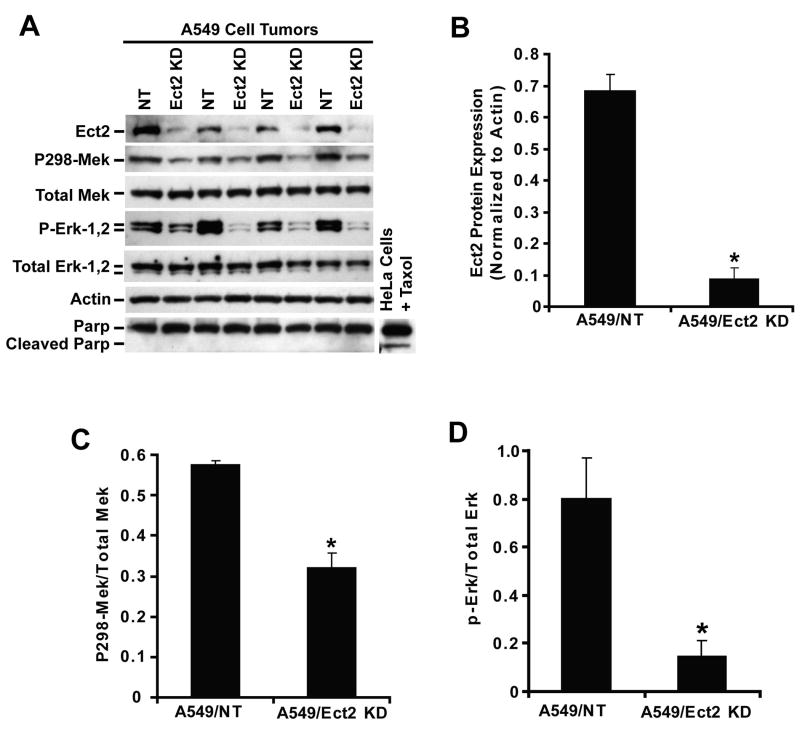

Rac1 drives tumor cell proliferation by activating a Pak-Mek1,2-Erk1,2 proliferative signaling pathway (Regala et al., 2005a). Therefore, we assessed the status of this pathway in A549/NT and A549/Ect2 KD tumors in vivo. Immunoblot analysis confirmed that A549/Ect2 KD tumors express less Ect2 than A549/NT tumors (Figure 7A). Quantitative analysis reveals a significant ∼5-fold decrease in Ect2 protein in A549/Ect2 KD tumors (Figure 7B). A549/Ect2 KD tumors exhibit lower phospho-298 Mek1,2 than A549/NT tumors with no change in total Mek1,2 (Figure 7A) resulting in a decreased ratio of phospho-298-Mek1,2 to total Mek1,2 (Figure 7C). A similar decrease in phospho-Erk1,2 (without a change in total Erk1,2) is observed in A549/Ect2 KD tumors (Figure 7A) resulting in a decreased ratio of phospho-Erk1,2 to total Erk1,2 (Figure 7D). No evidence for PARP cleavage, a biochemical marker of apoptosis, was observed in either A549 Ect2 KD or NT tumors (Figure 7A), consistent with our tumor TUNEL staining. Thus, Ect2 KD inhibits the Rac1-Pak-Mek1,2-Erk1,2 proliferative signaling pathway in vivo.

Figure 7. Ect2 activates the Pak-Mek1,2-Erk1,2 signaling pathway in vivo.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of A549/NT and A549/Ect2 KD tumors for Ect2, phospho-298-Mek1,2, total Mek1,2, phospho-Erk1,2, total Erk1,2, actin, and intact and cleaved PARP. Lysates from Hela cells treated with taxol for 48 hours were used a positive control for PARP cleavage. (B-D) Quantitative analysis demonstrates a statistically significant decrease in: (B) Ect2 protein expression (n=4/group; *p<0.0001), (C) phospho-298-Mek1,2/total Mek1,2 ratio (n=4/group; *p<0.004), and (D) phospho-Erk1,2/total Erk1,2 ratio (n=4/group; *p<0.03) (D) in A549/Ect2 KD tumors when compared to A549/NT tumors.

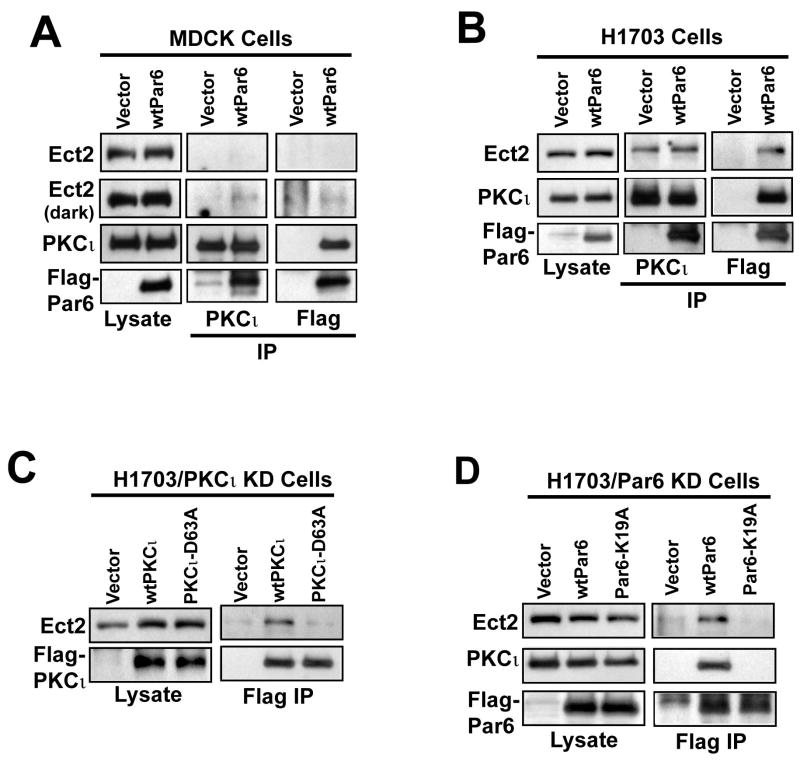

Ect2 associates with the PKCι-Par6α complex in NSCLC cells

Both Ect2 and the PKCι-Par6α complex regulate Rac1 signaling in NSCLC cells. Therefore, we assessed whether Ect2 binds the PKCι-Par6α complex (Figure 8). Since commercially available Par6 antibodies do not efficiently detect Par6α, we generated MDCK and H1703 cells expressing Flag-tagged wild-type human Par6α (wtPar6) or empty plasmid (Vector). Immunoblot analysis confirmed expression of endogenous Ect2, PKCι and Flag-Par6α in MDCK/wtPar6 cells (Figure 8A, lysate). When PKCι was immunoprecipitated from MDCK/Vector and MDCK/wtPar6 cells, Ect2 was detected as a faint band after a long exposure; however, Flag-Par6α efficiently co-precipitated with PKCι in MDCK/wtPar6 cells as expected (Figure 8A, PKCι IP). Similarly, when Flag-Par6α was immunoprecipitated from MDCK/wtPar6 cells, abundant PKCι, but very little Ect2, was detected in the resultant precipitates (Figure 8A, Flag IP). In contrast, when PKCι was immunoprecipitated from H1703/wtPar6 cells, both endogenous Ect2 and Flag-Par6α were easily detected in the resultant precipitates (Figure 8B, PKCι IP). Likewise, both Ect2 and PKCι efficiently co-precipitated with Flag-Par6α in H1703/wtPar6 cells (Figure 8B, Flag IP). Thus, a significant amount of Ect2 associates with PKCι-Par6α in NSCLC cells, whereas only a small amount of Ect2 is found in association with PKCι-Par6α in MDCK cells.

Figure 8. Ect2 associates with the PKCι-Par6α complex in NSCLC cells.

(A) MDCK cells were stably transfected with wild-type human Flag-tagged Par6a (wtPar6) or control empty vector (Vector). Total cell lysates (Lysate) confirm expression of endogenous Ect2, PKCι and Flag-Par6α. Immunoprecipitation of PKCι co-precipitates Flag-Par6α and a small amount of endogenous Ect2 from MDCK/wtPar6 cells (PKCι IP). Immunoprecipitation of Flag-Par6α co-precipitates PKCι and a small amount of Ect2 from MDCK/wtPar6 cells (Flag IP). (B) H1703/pBabe (Vector) and H1703/wtPar6 (wtPar6) cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation analysis as described in (A). Endogenous Ect2 co-precipitates with both PKCι and Par6α in these cells. (C) H1703/PKCι KD cells were transfected with wtPKCι, a PKCι-D69A mutant or empty plasmid as described in Materials and Methods. Total cell lysates confirm expression of Ect2 and Flag-PKCι alleles (Lysates). Immunoprecipitation using Flag antibody co-precipitates Ect2 with wtPKCι but not PKCι-D63A (Flag IP). (D) H1703/Par6α KD cells were transfected with Flag-tagged wtPar6α, Par6α-K19A or empty control plasmid (Vector). Cell lysates confirm expression of Ect2, PKCι and Flag-Par6α alleles (Lysates). Immunoprecipitation using Flag antibody co-precipitates Ect2 and PKCι with wtPar6α but not Par6α-K19A.

To further determine if Ect2 binds the PKCι-Par6α complex, H1703/PKCι KD cells were transfected with either Flag-tagged wild-type PKCι, a PKCι-D63A mutant which does not bind Par6α (Frederick et al., 2008), or control plasmid (Vector) (Figure 8C). Immunoblot analysis confirmed expression of Ect2, Flag-wild-type PKCι and Flag-PKCι-D63A in these cells (Figure 8C, lysate). Immunoprecipitation of Flag-PKCι revealed that Ect2 associates with wtPKCι, but not PKCι-D63A (Figure 8C, Flag IP). A complementary experiment was conducted in which H1703/Par6α KD cells were transfected with either wild-type Par6α or a Par6α-K19A mutant which does not bind PKCι (Frederick et al., 2008) (Figure 8D). Immunoblot analysis confirmed expression of Ect2, PKCι and the appropriate Flag-Par6α alleles in these cells (Figure 8D, Lysate). Both PKCι and Ect2 co-immunoprecipitated with wild-type Par6α; but neither PKCι nor Ect2 immunoprecipitated with Flag-Par6α-K19A (Figure 8D, Flag IP). These results indicate that Ect2 preferentially binds to the PKCι-Par6α complex when compared to PKCι or Par6α alone. Similar results were obtained in A549 cells (data not shown).

Cytoplasmic localization of Ect2 in NSCLC cells is regulated by PKCι and Par6α

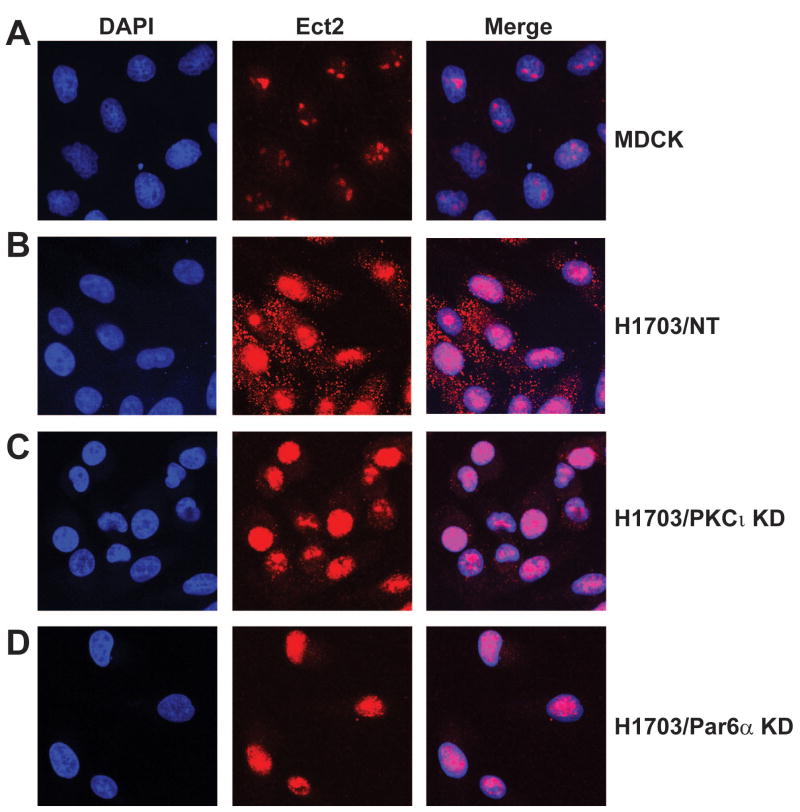

Since Ect2 is mis-localized to the cytoplasm of NSCLC tumors (Figure 2), we examined Ect2 localization by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy (Figure 9). Ect2 is almost exclusively nuclear in MDCK cells (Figure 9A). In contrast, Ect2 localizes to both the nucleus and cytoplasm of H1703/NT cells (Figure 9B). Interestingly, both H1703/PKCι KD and H1703/Par6α KD cells showed significantly less cytoplasmic Ect2 staining than H1703/NT cells (Figure 9C and D) indicating that PKCι and Par6α regulate cytoplasmic Ect2 localization. QPCR confirmed efficient PKCι and Par6α KD respectively in these cells (Supplemental Figure 3). A similar change in Ect2 localization from cytoplasm to nucleus was observed in A549/PKCι KD cells (Supplemental Figure 4).

Figure 9. Ect2 is mis-localized to the cytoplasm of NSCLC cells.

MDCK, H1703/NT, H1703/PKCι KD and H1703/Par6α KD cells were fixed, stained with DAPI and Ect2 antibody, and analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Ect2 localizes almost exclusively to the nucleus of MDCK cells. (B) Ect2 localizes to both the nucleus and cytoplasm of H1703/NT cells. In contrast, Ect2 is largely localized to the nucleus of H1703/PKCι KD (C) and H1703/Par6αKD (D) cells.

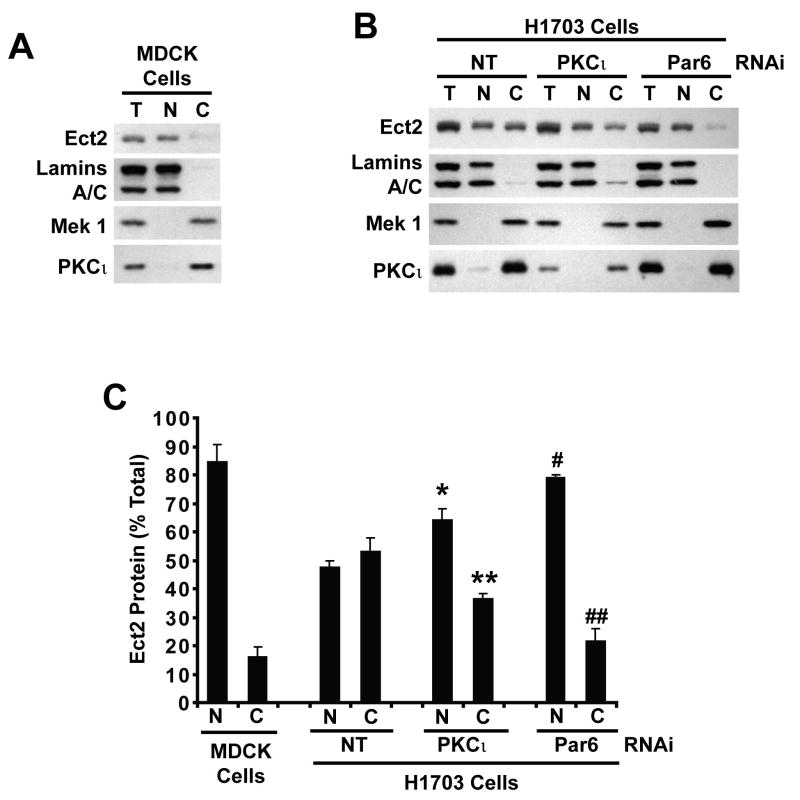

The effects of PKCι KD and Par6α KD on Ect2 localization were confirmed by cellular fractionation (Figure 10). Ect2 is predominantly nuclear in MDCK cells (Figure 10A). In contrast, H1703/NT cells express equal amounts of Ect2 in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, consistent with our immunofluorescence results (Figure 10B). H1703/PKCι KD and H1703/Par6α KD cells exhibit an increase in nuclear Ect2 and a concomitant decrease in the cytoplasmic Ect2 (Figure 10B). Total Ect2 in H1703/PKCι KD and H1703/Par6α KD cells was comparable to H1703/NT cells, indicating that PKCι KD and Par6α KD primarily affect Ect2 localization not expression. The purity of cellular fractions was confirmed using nuclear (lamins A/C) and cytoplasmic (Mek1,2) markers (Figure 10A and B). As expected, PKCι is predominantly cytoplasmic in MDCK and H1703 cells and was efficiently knocked down in H1703/PKCι KD cells (Figure 10A and B). Quantitative analysis of three independent experiments confirmed that Ect2 is largely nuclear in MDCK cells but is distributed equally between the nucleus and cytoplasm of H1703/NT cells, and that H1703/PKCι KD and H1703/Par6α KD cells exhibit a significant redistribution of Ect2 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (Figure 10C).

Figure 10. PKCι and Par6α regulate the cytoplasmic distribution of Ect2 in NSCLC cells.

MDCK (A), H1703/NT, H1703/PKCι KD and H1703/Par6α KD (B) cells were fractionated into cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. Total cell lysates, nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions from an equivalent cell number were subjected to immunoblot analysis for Ect2, PKCι, lamins A/C and Mek1. Lamins A/C served as a marker of nuclei and Mek1 as a marker of cytoplasm. (C) Quantitative analysis of nuclear and cytoplasmic Ect2 in MDCK, H1703/NT, H1703/PKCι KD and H1703/Par6α KD cells. Immunoblots from three independent fractionation experiments were analyzed by densitometry for Ect2. Results are plotted as % Total Ect2 in the nucleus (N) and cytoplasm (C). *, **, # and ## indicate a statistically significant difference in the amount of nuclear (* and #) and cytoplasmic (** and ##) Ect2 in the indicated cell line when compared to H1703/NT cells (*p<0.02), (**p<0.03), (#p<0.0005) and (##p<0.01); n=3.

Discussion

Rho family GTPases are regulated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs). Since Rac1 activity is high in NSCLC cells as a result of the PKCι-Par6α complex (Frederick et al., 2008; Regala et al., 2005a), we hypothesized that a Rac1-GEF may bind the PKCι-Par6α complex to regulate Rac1 activity in NSCLC tumors. The Ect2 GEF is an attractive candidate for such a role since the Ect2 gene, ECT2, is located at chromosome 3q26, and elevated Ect2 mRNA and protein has been reported in human gliomas, lung, esophageal and pancreatic cancers (Hirata et al., 2009; Sano et al., 2006; Takai et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 2008). Here, we demonstrate that ECT2 and PRKCI are co-amplified as part of the 3q26 amplicon, leading to coordinate overexpression of Ect2 and PKCι in LSCC tumors. Our data provide the first evidence that Ect2 and PKCι are genetically linked in human cancer, and reveal that Ect2 is a relevant target of the 3q26 amplicon.

We also demonstrate that Ect2 is functionally important in anchorage-independent growth and invasion of NSCLC cells in vitro and tumorigenicity in vivo. Our data are consistent with several recent reports implicating Ect2 in the growth and invasion of cancer cells in vitro (Hirata et al., 2009; Salhia et al., 2008). Our results provide important new mechanistic insight into how Ect2 participates in transformation and extend previous findings to the in vivo setting. Ect2 KD blocks tumorigenicity by inhibiting tumor cell proliferation, while causing little or no change in tumor apoptosis or vascularization. Furthermore, Ect2 selectively regulates Rac1 activity in NSCLC cells and Rac1 is a critical downstream effector of Ect2-dependent transformation in vitro. Finally, Ect2 drives tumor cell proliferation by activating a Rac1-Pak-Mek1,2-Erk1,2 signaling axis in vivo. Further studies will be required to dissect the signaling pathway(s) involved in Ect2-, Rac1-dependent invasion.

Ect2 plays a physiologic role in cytokinesis, suggesting a possible mechanism by which Ect2 KD could block NSCLC cell proliferation. Surprisingly however, whereas Ect2 KD leads to a severe cytokinesis defect in MDCK cells, no such defect occurs in NSCLC cells in vitro, or A549 tumors in vivo. Our data differ from a recent report that transient Ect2 KD in A549 cells leads to a transitory inhibition of cell cycle (Hirata et al., 2009). This discrepancy may result from the use of transient Ect2 KD by siRNA as opposed to stable Ect2 KD by lentiviral shRNA. Our stably transduced Ect2 KD cells may express sufficient Ect2 to remain above a critical threshold required for cytokinesis. Alternatively, NSCLC cells may utilize a recently-described alternative cytokinesis mechanism that makes fibrosarcoma cells resistant to Ect2 KD-induced cytokinesis defects (Kanada et al., 2008). Our finding that Ect2 KD does not induce a cytokinesis defect (or change in PDT) in any of the five NSCLC cell lines tested argues for the existence of an Ect2-independent cytokinesis mechanism in NSCLC. Our finding that Ect2 KD in NSCLC cells does not inhibit RhoA, the well-characterized target of Ect2 in cytokinesis (Tatsumoto et al., 1999), further suggests the existence of such an alternative cytokinesis mechanism. In either case, our analysis reveals a novel Ect2 function in transformation that is distinct from cytokinesis.

Ect2 localizes to the nucleus of MDCK and normal lung epithelial cells. In contrast, Ect2 is overexpressed and mis-localized to the cytoplasm of primary NSCLC tumor cells and NSCLC cell lines. The cytoplasmic mis-localization of Ect2 is reminiscent of previous observations correlating cytoplasmic mislocalization of Ect2 fragments with transformation. When expressed in mouse fibroblasts, the C-terminal Ect2 GEF domain localized to the cytoplasm, exhibited constitutive GEF activity and caused cellular transformation (Miki et al., 1993; Saito et al., 2004; Solski et al., 2004). In contrast, full-length Ect2 localized to the nucleus and exhibited no transforming activity (Saito et al., 2004; Solski et al., 2004).

Our data demonstrate that full length, cytoplasmic Ect2 binds the oncogenic PKCι-Par6α complex in NSCLC cells. Ect2 binds more efficiently to the PKCι-Par6α complex than PKCι or Par6α alone, indicating that both PKCι and Par6α contribute to Ect2 binding. PKCι or Par6α KD blocks NSCLC cell transformation (Frederick et al., 2008) and leads to redistribution of Ect2 to the nucleus. These data argue that the PKCι-Par6α complex regulates the cytoplasmic localization and oncogenic potential of Ect2. Our data are interesting in light of previous reports that Ect2 can bind the atypical PKC-Par6-Par3 polarity complex at cell-cell junctions in MDCK cells (Liu et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2006). Our data confirm that a very small amount of Ect2 can be found in association with PKCι and Par6α in MDCK cells; furthermore, we detect very faint Ect2 staining at cell-cell junctions in MDCK cells (data not shown). In NSCLC cells, which have lost cellular polarity, Ect2 exhibits punctuate staining throughout the cytoplasm, and efficiently bind to the oncogenic PKCι-Par6α complex to activate Rac1 activity and drive transformation. Future studies will be required to determine the basis for the punctuate Ect2 staining pattern, and the molecular mechanisms that regulate the formation, dynamics and activity of the oncogenic PKCι-Par6α-Ect2 complex in NSCLC cells.

In conclusion, our data reveal a novel genetic, biochemical and functional link between PKCι and Ect2 in NSCLC. PKCι and Ect2 are coordinately amplified and over-expressed in NSCLC as part of the 3q26 amplicon. Ect2 plays a requisite role in the anchorage-independent growth and invasion of NSCLC cells in vitro and tumorigenicity in vivo. Ect2 is mis-localized to the cytoplasm of NSCLC cells as a consequence of its interaction with the oncogenic PKCι-Par6α complex, and the PKCι-Par6α-Ect2 complex drives transformed growth through activation of a Rac1-Pak-Mek1,2-Erk1,2 signaling axis. Our data are the first to identify Ect2 as a relevant target of tumor-specific 3q26 amplification and to elucidate a molecular mechanism by which Ect2 participates in the transformed phenotype of human tumor cells. Furthermore, our data provide new mechanistic insight into previous observations regarding the cytoplasmic localization of Ect2 fragments and transforming potential. Finally, our data reveal a novel paradigm in which two oncogenes within a single amplicon are genetically, biochemically and functionally linked to cellular transformation. Ect2 and PKCι may be similarly linked in other tumors that harbor 3q26 amplification, such as SCC of the head and neck (Snaddon et al. 2001), esophagus (Imoto et al., 2001), cervix (Sugita et al., 2000) and ovary (Sonoda et al., 1997 and Sugita et al., 2000).

Supplementary Material

A. Primer probe sets for real time qPCR. The catalog number indicates an ABI Assay on Demand. B. RNAi target sequences. CDS= coding sequence; 3′UTR= three prime untranslated region.

(A) Ect2 KD inhibits Ect2 expression in NSCLC cell lines. A427, A549, H358 and H460 NSCLC cell lines were stably infected with lentiviral RNAi constructs targeting Ect2 (construct #3 in Figure 3) or a NT control construct. Ect2 mRNA abundance and protein expression were determined by qPCR and immunoblot analysis respectively as described in Materials and Methods. A427, A549, H358 and H460 cells expressing either Ect2 KD or NT KD were assessed for anchorage-independent growth in soft agar (B) and invasion (C) as described in Materials and Methods. Note that H358 cells were not invasive in these assays. * indicates a statistically significant difference from the same cell line expressing NT. p<0.05 in all cases.

RNA was isolated from the H1703 PKCι and Par6α KD cells used in Figures 9 and 10, and was subjected to qPCR for PKCι (A) and Par6α (B) respectively. In addition, lysates from PKCι KD and NT cells were subjected immunoblot analysis for PKCι and actin (A, inset). qPCR results are expressed as % NT control and represent the mean +/- SE, n=3.

A549 cells were stably transduced with either PKCι or NT RNAi lentivirus and analyzed for PKCι mRNA abundance and protein expression as described in Materials and Methods. (A) qPCR and immunoblot characterization of PKCι KD. qPCR results are expressed as % NT control and represent the mean +/- SE, n=3. A549/NT and A549/PKCι KD cells were fixed, stained with DAPI and Ect2 antibody, and analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Ect2 localizes to both the nucleus and cytoplasm (arrowheads) of A549/NT cells. In contrast, Ect2 is largely localized to the nucleus of A549/PKCι KD cells (C).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Roderick P. Regala for assistance with the ectopic tumor studies, Dr. Andras Khoor and Capella Weems for analysis of primary NSCLC tumors, Pam Kreinest and Brandy Edenfield for immunohistochemistry, Dr. Lee Jamieson and Alyssa Kunz for technical assistance, and Drs. E. Aubrey Thompson and Nicole R. Murray for critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA081436), The V Foundation for Cancer Research and The Mayo Foundation to A.P.F.

References

- Balsara BR, Sonoda G, du Manoir S, Siegfried JM, Gabrielson E, Testa JR. Comparative genomic hybridization analysis detects frequent, often high-level, overrepresentation of DNA sequences at 3q, 5p, 7p, and 8q in human non-small cell lung carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2116–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brass N, Ukena I, Remberger K, Mack U, Sybrecht GW, Meese EU. DNA amplification on chromosome 3q26.1-q26.3 in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung detected by reverse chromosome painting. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:1205–8. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick LA, Matthews JA, Jamieson L, Justilien V, Thompson EA, Radisky DC, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-10 is a critical effector of protein kinase Ciota-Par6alpha-mediated lung cancer. Oncogene. 2008 doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T, Abe M, Inoue H, Yu LR, Veenstra TD, Kang YH, et al. Cytokinesis regulator ECT2 changes its conformation through phosphorylation at Thr-341 in G2/M phase. Oncogene. 2006;25:566–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata D, Yamabuki T, Miki D, Ito T, Tsuchiya E, Fujita M, et al. Involvement of Epithelial Cell Transforming Sequence-2 Oncoantigen in Lung and Esophageal Cancer Progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:256–266. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanada M, Nagasaki A, Uyeda TQ. Novel Functions of Ect2 in Polar Lamellipodia Formation and Polarity Maintenance during “Contractile Ring-Independent” Cytokinesis in Adherent Cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:8–16. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JE, Billadeau DD, Chen J. The tandem BRCT domains of Ect2 are required for both negative and positive regulation of Ect2 in cytokinesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5733–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409298200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XF, Ishida H, Raziuddin R, Miki T. Nucleotide exchange factor ECT2 interacts with the polarity protein complex Par6/Par3/protein kinase Czeta (PKCzeta) and regulates PKCzeta activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6665–75. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6665-6675.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XF, Ohno S, Miki T. Nucleotide exchange factor ECT2 regulates epithelial cell polarity. Cell Signal. 2006;18:1604–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T, Smith CL, Long JE, Eva A, Fleming TP. Oncogene ect2 is related to regulators of small GTP-binding proteins. Nature. 1993;362:462–5. doi: 10.1038/362462a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niiya F, Tatsumoto T, Lee KS, Miki T. Phosphorylation of the cytokinesis regulator ECT2 at G2/M phase stimulates association of the mitotic kinase Plk1 and accumulation of GTP-bound RhoA. Oncogene. 2006;25:827–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niiya F, Xie X, Lee KS, Inoue H, Miki T. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 1 induces cytokinesis without chromosome segregation in an ECT2 and MgcRacGAP-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36502–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regala RP, Weems C, Jamieson L, Copland JA, Thompson EA, Fields AP. Atypical protein kinase Ciota plays a critical role in human lung cancer cell growth and tumorigenicity. J Biol Chem. 2005a;280:31109–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505402200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regala RP, Weems C, Jamieson L, Khoor A, Edell ES, Lohse CM, et al. Atypical protein kinase C iota is an oncogene in human non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2005b;65:8905–11. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S, Liu XF, Kamijo K, Raziuddin R, Tatsumoto T, Okamoto I, et al. Deregulation and mislocalization of the cytokinesis regulator ECT2 activate the Rho signaling pathways leading to malignant transformation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7169–79. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306725200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S, Tatsumoto T, Lorenzi MV, Chedid M, Kapoor V, Sakata H, et al. Rho exchange factor ECT2 is induced by growth factors and regulates cytokinesis through the N-terminal cell cycle regulator-related domains. J Cell Biochem. 2003;90:819–36. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salhia B, Tran NL, Chan A, Wolf A, Nakada M, Rutka F, et al. The guanine nucleotide exchange factors trio, Ect2, and Vav3 mediate the invasive behavior of glioblastoma. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1828–38. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano M, Genkai N, Yajima N, Tsuchiya N, Homma J, Tanaka R, et al. Expression level of ECT2 proto-oncogene correlates with prognosis in glioma patients. Oncol Rep. 2006;16:1093–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solski PA, Wilder RS, Rossman KL, Sondek J, Cox AD, Campbell SL, et al. Requirement for C-terminal sequences in regulation of Ect2 guanine nucleotide exchange specificity and transformation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25226–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313792200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita M, Tanaka N, Davidson S, Sekiya S, Varella-Garcia M, West J, et al. Molecular definition of a small amplification domain within 3q26 in tumors of cervix, ovary, and lung. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2000;117:9–18. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(99)00135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai S, Long JE, Yamada K, Miki T. Chromosomal localization of the human ECT2 proto-oncogene to 3q26.1-->q26.2 by somatic cell analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Genomics. 1995;27:220–2. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumoto T, Xie X, Blumenthal R, Okamoto I, Miki T. Human ECT2 is an exchange factor for Rho GTPases, phosphorylated in G2/M phases, and involved in cytokinesis. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:921–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Anastasiadis PZ, Liu Y, Thompson EA, Fields AP. Protein Kinase C βII Induces Cell Invasion Through a Ras/MEK-, PKCιota/RAC 1-dependent Signaling Pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22118–22123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400774200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ML, Lu S, Zhou L, Zheng SS. Correlation between ECT2 gene expression and methylation change of ECT2 promoter region in pancreatic cancer. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:533–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. Primer probe sets for real time qPCR. The catalog number indicates an ABI Assay on Demand. B. RNAi target sequences. CDS= coding sequence; 3′UTR= three prime untranslated region.

(A) Ect2 KD inhibits Ect2 expression in NSCLC cell lines. A427, A549, H358 and H460 NSCLC cell lines were stably infected with lentiviral RNAi constructs targeting Ect2 (construct #3 in Figure 3) or a NT control construct. Ect2 mRNA abundance and protein expression were determined by qPCR and immunoblot analysis respectively as described in Materials and Methods. A427, A549, H358 and H460 cells expressing either Ect2 KD or NT KD were assessed for anchorage-independent growth in soft agar (B) and invasion (C) as described in Materials and Methods. Note that H358 cells were not invasive in these assays. * indicates a statistically significant difference from the same cell line expressing NT. p<0.05 in all cases.

RNA was isolated from the H1703 PKCι and Par6α KD cells used in Figures 9 and 10, and was subjected to qPCR for PKCι (A) and Par6α (B) respectively. In addition, lysates from PKCι KD and NT cells were subjected immunoblot analysis for PKCι and actin (A, inset). qPCR results are expressed as % NT control and represent the mean +/- SE, n=3.

A549 cells were stably transduced with either PKCι or NT RNAi lentivirus and analyzed for PKCι mRNA abundance and protein expression as described in Materials and Methods. (A) qPCR and immunoblot characterization of PKCι KD. qPCR results are expressed as % NT control and represent the mean +/- SE, n=3. A549/NT and A549/PKCι KD cells were fixed, stained with DAPI and Ect2 antibody, and analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Ect2 localizes to both the nucleus and cytoplasm (arrowheads) of A549/NT cells. In contrast, Ect2 is largely localized to the nucleus of A549/PKCι KD cells (C).