Abstract

The Xenopus cerberus gene encodes a secreted factor that is expressed in the anterior endomesoderm of gastrula stage embryos and can induce the formation of ectopic heads when its mRNA is injected into Xenopus embryos [Bouwmeester, T., Kim, S., Lu, B. & De Robertis, E. M. (1996) Nature (London) 382, 595–601]. Here we describe the existence of a cerberus-related gene, Cerr1, in the mouse. Cerr1 encodes a putative secreted protein that is 48% identical to cerberus over a 110-amino acid region. Analysis of a mouse interspecific backcross panel demonstrated that Cerr1 mapped to the central portion of mouse chromosome 4. In early gastrula stage mouse embryos, Cerr1 is expressed in the anterior visceral endoderm and in the anterior definitive endoderm. In somite stage embryos, Cerr1 expression is restricted to the most recently formed somites and in the anterior presomitic mesoderm. Germ layer explant recombination assays demonstrated that Cerr1-expressing somitic-presomitic mesoderm, but not older Cerr1-nonexpressing somitic mesoderm, was able to mimic the anterior neuralizing ability of anterior mesendoderm and maintain Otx2 expression in competent ectoderm. In most Lim1−/− headless embryos, Cerr1 expression in the anterior endoderm was weak or absent. These results suggest that Cerr1 may play a role in anterior neural induction and somite formation during mouse development.

Gastrulation in vertebrate embryos is accompanied by an anterior migration of mesendoderm tissue from the organizer. The organizer is a region of the gastrula embryo that can induce the formation of a second neural axis when transplanted to an undifferentiated region of a host gastrula stage embryo (1). During its migration, the anterior mesendoderm is thought to induce the overlying ectoderm to develop as anterior neural tissue. Subsequently, the posterior mesoderm that forms later in gastrulation is thought to transform a portion of the induced neural tissue into posterior neural tissue resulting in the anterior-posterior patterning of the central nervous system (2).

Classical experiments by Mangold (3) and Eyal-Giladi (4) support the hypothesis that the anterior mesendoderm induces the overlying ectoderm to form anterior neural tissue. Mangold transplanted different regions of dorsal mesendoderm by using the Einsteck method to the blastocoel cavity of host newt embryos. He found that the anterior dorsal mesendoderm induced head-specific structures whereas more posterior dorsal mesendoderm induced posterior brain structures. Eyal-Giladi (4) determined the specification states of the overlying ectoderm at different times during gastrulation in urodele embryos. She found that the first type of tissue to be induced after the initial involution of the dorsal mesendoderm was forebrain tissue in the posterior ectoderm. As the dorsal mesendoderm migrated further anteriorly, the anterior ectoderm was induced to become forebrain tissue and the posterior ectoderm now developed as posterior neurectoderm.

More recent experiments in Xenopus and mouse provide molecular support for the role of anterior mesendoderm in anterior neural development. In Xenopus, if anterior notochord tissue is recombined with ectoderm, it can strongly induce the expression of the midbrain marker engrailed (en-2) whereas posterior notochord tissue induces the expression of en-2 to a lesser extent (5). In the mouse, germ layer recombination explant studies demonstrate that anterior mesendoderm, but not posterior mesendoderm, can induce the expression of the anterior neural marker genes Engrailed-1 (En-1) and Engrailed-2 (En-2) (6) and maintain and induce the expression of the forebrain-midbrain marker gene Otx2 (7). These explant studies also demonstrate that the ectoderm becomes committed to form anterior neural tissue by the mid-streak stage that coincides with the anterior migration of the mesendoderm. Additional support for the involvement of anterior mesendoderm in anterior neural induction comes from mouse knockout studies. Lim1 and Otx2 are homeobox genes that are expressed in the anterior mesendoderm of gastrula stage mouse embryos (7–9). Both Lim1- and Otx2-deficient embryos were found to lack anterior head structures rostral to rhombomere 3 in the hindbrain (9–12). Analysis of early gastrulation stage mutant embryos using molecular markers suggests that the development of the anterior mesendoderm tissues is altered in both Lim1 and Otx2 mutants.

A number of genes encoding secreted factors have been identified in Xenopus that are expressed in the organizer and the anterior mesendoderm. These include noggin, follistatin, and chordin. (13–15). When mRNAs for these genes are injected into Xenopus embryos they are able to induce neural tissue development and axis formation. Both the noggin and chordin proteins have been shown to bind BMP4 and it is believed that their ability to induce neural development results from their ability to suppress BMP signaling (16, 17). Another gene encoding a secreted factor expressed in the organizer is cerberus (18). cerberus is expressed in the anterior endomesoderm of gastrula stage embryos and its expression is reported to overlap extensively with Xlim-1 and goosecoid early in gastrulation. cerberus differs from noggin, follistatin, and chordin in that injection of cerberus mRNA into Xenopus embryos suppresses the formation of posterior mesoderm and specifically induces the formation of ectopic head structures. These results suggest that cerberus may be a component of the head induction pathway in vertebrates.

In an effort to identify genes that may be downstream of Lim1 in the head induction pathway in the mouse, we have searched for a mouse homolog of cerberus. Here we report the existence of a mouse cerberus-related gene that we have designated Cerr1. Cerr1 is expressed in the anterior visceral and definitive endoderm of early gastrulation stage mouse embryos and later in development it is expressed in the two most newly formed somites and in the anterior presomitic mesoderm. Because anterior mesendoderm, which expresses Cerr1, has previously been shown to have anterior neuralizing ability (6, 7), we tested whether Cerr1-expressing somitic-presomitic mesoderm might also have anterior neuralizing ability. We show that Cerr1-expressing somitic-presomitic mesoderm, but not Cerr1-nonexpressing somitic mesoderm, can maintain the expression of the anterior neural marker gene Otx2 in ectoderm that is competent to respond to anterior neuralizing signals. In addition, we find that Cerr1 expression in early gastrula stage Lim1−/− headless embryos is weak or absent in most mutant embryos. These results suggest that Cerr1 may be involved in the induction or maintenance of anterior neural fates and somite formation during mouse embryogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of Mouse Cerr1 cDNA Clones.

A mouse cerberus-related cDNA sequence was identified from the dbEST database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/dbEST/index.html) by using the tblastn program (19). The expressed sequence tag (EST) clone 538769, was obtained from Genome Systems (St. Louis). To obtain additional 5′ cDNA sequence we performed 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends PCR using embryonic day (E) 10.5 total RNA. The reverse transcription and amplification reactions were performed by using a commercial kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (GIBCO/BRL). The reverse transcription primer used was 5′-CCGATGCCAGAACCTCTTGG-3′. The PCR amplification primer used was 5′-CTTCCTCCTGTAGAGGTGAT-3′. The PCR amplification conditions used were 94°C for 4 min followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 40 sec, 72°C for 1 min, followed by 72°C for 10 minutes. A PCR product of ≈500 bp was amplified and subcloned into Bluescript II KS− (Stratagene) and sequenced by the DNA Sequencing Core at the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. Additional cDNA clones were identified by screening a mouse E7.5 cDNA library (provided by Akihiko Shimono, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center) with a 0.45-kb SalI-PstI fragment from the EST clone.

Chromosomal Mapping.

The chromosomal location of Cerr1 was determined by Southern hybridization to a mouse interspecific mapping panel obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. The mapping panel was composed of genomic DNA from 94 backcross progeny from an interspecific cross between (C57BL/6J × SPRE/Ei) F1 hybrid female and SPRET/Ei male mice (20). Using a 0.45-kb SalI-PstI DNA fragment from the EST clone as a probe, a SstI restriction fragment length polymorphism was identified between C57BL/6J and SPRET/Ei genomic DNA. A Southern blot membrane containing DNA samples from the backcross progeny digested with SstI provided by Yuanhao Li (21) was then hybridized with the 0.45-kb SalI-PstI DNA probe. The restriction fragment length polymorphism distribution pattern of Cerr1 in the backcross progeny was submitted to The Jackson Laboratory for analysis.

Whole Mount in Situ Hybridization.

Whole mount in situ hybridization reactions were performed essentially as described by Wilkinson (22). Single-stranded RNA probes were labeled with digoxigenin-UTP according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Boehringer Mannheim). Preparation of whole mount embryos for paraffin embedding and sectioning was performed as described by Sasaki and Hogan (23).

Germ Layer Explant Recombination Assays.

Explant and recombination assays were performed essentially as described by Ang and Rossant (6). Ectoderm was isolated from the distal tip region of early primitive streak stage embryos using glass capillary needles. Tissue fragments containing somitic and presomitic mesoderm were isolated from E9.5 embryos with the aid of tungsten needles (0.5 mm, Goodfellow, Cambridge, U.K.). The tissues layers were enzymatically separated by incubation in 0.5% trypsin, 0.25% pancreatin in phosphate buffered saline for 5 min at 4°C. The enzymatic reaction was stopped by transferring the fragments into DMEM containing 15% fetal calf serum. The mesodermal and ectoderm components were cultured alone or together in a 25 μl drop of DMEM supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine and 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol for 30 hr. The explants were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hr at 4°C. Whole mount RNA in situ hybridization was performed as described above.

RESULTS

Identification of a Mouse cerberus-Related Gene.

We searched the dbEST database at the NCBI for genes related to cerberus. One mouse EST clone, no. 538769, from the Beddington E7.5 mouse cDNA library, was identified that shared statistically significant homology with cerberus at the amino acid level. We have named this cDNA clone Cerr1, for cerberus-related gene 1. The Cerr1 EST clone is ≈1.8 kb in size. DNA sequencing of the EST clone indicated that it contained a Poly(A) tail but lacked the amino terminal coding region. 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends PCR was used to obtain ≈200 bp of additional 5′ sequence that contained a consensus translation initiation start site (24). Additional cDNA clones were identified by screening a mouse E7.5 cDNA library with a 0.45 PstI-SalI DNA fragment from the EST clone. Ten clones were plaque purified and subcloned. The cDNA clones ranged in size from ≈1.9 to 3.5 kb. Sequencing of portions of the cDNA clones revealed that the clones shared the same coding region but the length of the 3′ noncoding region was different between the clones. Translation of the ORF indicated that Cerr1 can encode a protein of 272 amino acids. The composite DNA sequence of the EST clone and the 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends product has been deposited in GenBank database. Hybridization of a mouse genomic Southern blot with a Xenopus cerberus DNA probe encompassing the region conserved between cerberus and Cerr1 (see below) at moderate stringency (final wash = 2× standard saline citrate at 55°; 1× standard saline citrate = 0.15 M sodium chloride/0.015 M sodium citrate, pH 7) failed to reveal evidence for additional cerberus family members.

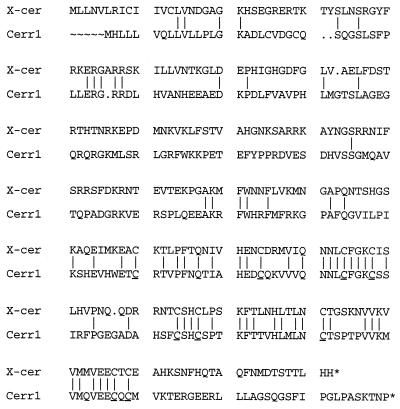

Alignment of the predicted mouse Cerr1 protein sequence with Xenopus cerberus revealed a 110-amino acid region of overlap that is 48% similar (Fig. 1). Within this region the predicted proteins share a conserved spacing of nine cysteine residues. Outside this region, the two predicted proteins do not share extended regions of identity. A search of the prosite Dictionary of Protein Sites and Patterns, distributed by the European Molecular Biology Laboratory, failed to reveal any sequence motifs. Two potential glycosylation sites are present at amino acid positions 168 and 222 with the latter site being conserved with cerberus. The amino terminus of the predicted Cerr1 protein contains a hydrophobic region that may serve as a signal peptide suggesting that Cerr1 is a secreted protein.

Figure 1.

Comparison of Xenopus cerberus and mouse Cerr1 predicted amino acid sequences. The nine conserved cysteine residues in Cerr1 are underlined. Dots (⋅) indicate spaces introduced for optimal alignment. The stop codons are designated by asterisks (*). Sequences were aligned by the pileup program.

Chromosomal Location of Cerr1.

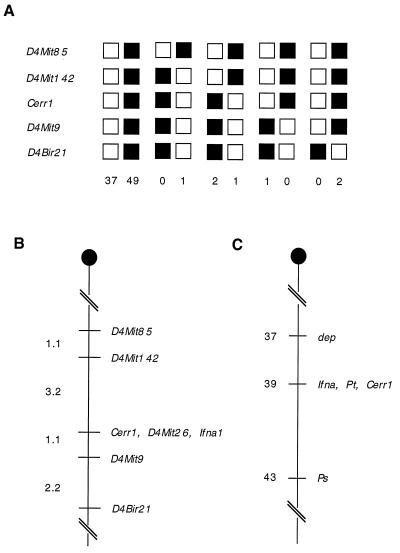

The chromosomal location of Cerr1 was determined by Southern hybridization to a mouse interspecific mapping panel obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. The interspecific mapping panel is made up 94 DNA samples from the progeny of matings between female (C57BL/6J) and male SPRET/Ei mice (20). Southern blots of SstI-digested DNA of the 94 backcross progeny were hybridized with the 0.45-kb SalI-PstI fragment from the EST clone. SstI fragments of ≈6 and 3.2 kb were used to follow the inheritance of the Cerr1 allele from C57BL/6J and SPRET/Ei, respectively. The haplotypes of the backcross panel were compared with other previously typed markers (Fig. 2A). One mouse with a double crossover event in the region where Cerr1 mapped was excluded from the haplotype count. The mapping results indicated that Cerr1 cosegregated with a number of other loci including interferon-alpha 1 (Ifna1) and D4Mit26 on the central portion of mouse chromosome 4 (Fig. 2B). A classical mouse mutation called Pintail (Pt) also maps approximately to this region (Fig. 2C) (25). Pt mice have tails of variable length with a thin threadlike tip (26). The defect is thought to be caused by an abnormal rate of cell division in the notochord of E10.5 embryos (27). As Cerr1 is not expressed in the notochord during development (see below) it is unlikely to be mutated in Pt mice. Based on the chromosomal location of the human interferon alpha genes (28), the predicted human syntenic region is chromosome 9p22.

Figure 2.

Mouse Cerr1 mapped to the central portion of chromosome 4 by interspecific backcross analysis. (A) Haplotype analysis of backcross data. Each column represents the chromosome identified in the backcross progeny that was inherited from the (C57BL/6J × SPRET/Ei) F1 mother. ▪, The C57BL/6J allele; □, the SPRET/Ei allele. The number of offspring that inherited each type of chromosome are listed at the bottom. (B) Likely gene order, with recombination distances between loci shown to the left of the chromosome. (C) Location of Cerr1 relative to the interferon alpha complex genes and several mouse mutations on chromosome 4.

Expression Pattern of Cerr1 during Early Development.

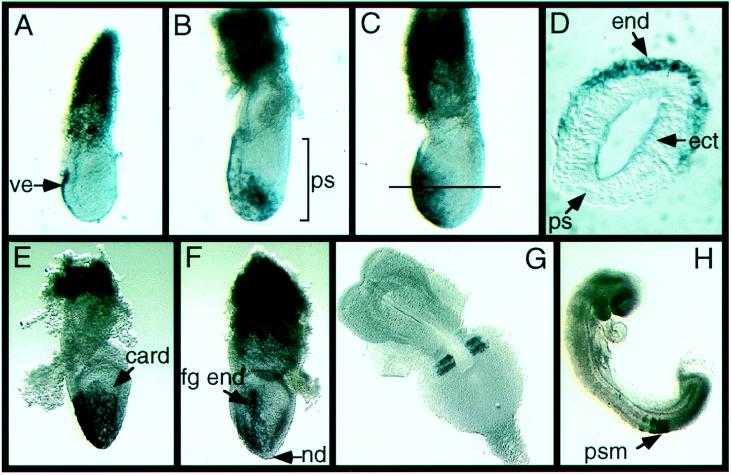

To determine the pattern of expression of Cerr1 during early mouse embryogenesis, whole mount in situ hybridization was performed on E6.5 through E9.5 embryos. At E6.5, in early and mid-streak stage embryos, Cerr1 was expressed in the anterior visceral endoderm. The Cerr1 expression domain extended from the extraembryonic–embryonic junction to approximately two thirds of the way down the epiblast (Fig. 3A). This pattern of expression is similar to that of a number of other anteriorly expressed genes including Otx2 (7), Lim1 (9), Rpx/Hesx1 (29, 30), nodal (31), goosecoid, and HNF3β (32). By the mid-streak to late streak stage, Cerr1 continued to be expressed in the anterior visceral endoderm but was also expressed in the definitive endoderm emanating from the anterior portion of the primitive streak (Fig. 3B). By the neural plate stage at E7.5, Cerr1 expression was present throughout the anterior definitive endoderm layer including both the midline and anterior lateral endoderm but Cerr1 was not expressed in the anterior-most lateral region that appears to correspond to the presumptive cardiac region (33, 34) (Fig. 3 C–E). At the early headfold stage, Cerr1 expression was reduced in the anterior lateral region and expression was seen primarily in the foregut endoderm (Fig. 3F). In early E8.5 embryos, Cerr1 expression was restricted to the two most recently formed somites (Fig. 3G). Expression elsewhere in the embryo was not detected. In E9 and E9.5 embryos, Cerr1 continued to be expressed in the two newest formed somites and also in the anterior presomitic mesoderm (Fig. 3H). These results indicate that Cerr1 is expressed in the anterior visceral and definitive endoderm and in the forming somitic mesoderm during early mouse embryogenesis.

Figure 3.

Expression of Cerr1 from E6.5–E9 revealed by whole mount RNA in situ hybridization. In E6.5 and E7.5 embryos, anterior is to the left and posterior to the right. (A) E6.5 early/mid-streak stage embryo. Expression is localized to the anterior visceral endoderm. (B) E7.0 mid- to late streak stage embryo. Cerr1 is expressed in the anterior visceral endoderm and the definitive endoderm emanating from the anterior portion of the primitive streak. (C) E7.5 early neural plate stage embryo. Cerr1 is expressed in both the anterior and the anterior lateral portion of the embryo. (D) Transverse section of an E7.5 early neural plate embryo showing Cerr1 expression in the anterior endoderm layer. The approximate level of the section is shown by the line in C. (E) Frontal view of Cerr1 expression in an E7.5 early neural plate stage embryo showing Cerr1 expression in the midline and anterior lateral region but excluded from the presumptive cardiac region. (F) Frontal view of an early headfold stage embryo. Expression is localized to the foregut endoderm. (G) E8.5 early somite stage embryo. Cerr1 is expressed in the two most newly formed somites. (H) E9 embryo. Cerr1 is expressed in the last two newly formed somites and in the anterior portion of the presomitic mesoderm. card, presumptive cardiac region; ect, ectoderm; end, endoderm; fg end, foregut endoderm; nd, node; ps, primitive streak; psm, presomitic mesoderm; ve, visceral endoderm.

Germ Layer Recombination Using Cerr1-Expressing Somitic-Presomitic Mesoderm.

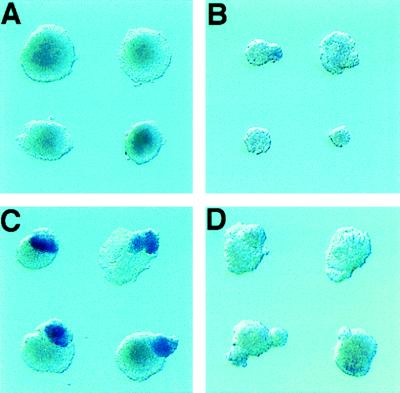

Germ layer recombination explant experiments demonstrate that anterior mesendoderm can induce and maintain the expression of anterior neural markers (6, 7). Because anterior mesendoderm expresses Cerr1, we asked whether Cerr1 expressing somitic-presomitic mesoderm might also have anterior neuralizing properties. To determine whether Cerr1-expressing somitic-presomitic mesoderm has anterior neuralizing properties, germ layer recombination explants were performed by using Cerr1-expressing somitic-presomitic mesoderm from E9.5 embryos and the anterior ectoderm from E6.5 early streak stage embryos (Table 1). These tissues were cultured alone and together for 30 hr and then assayed by whole mount RNA in situ hybridization for the expression of the anterior neural marker gene Otx2. When Cerr1-expressing somitic-presomitic mesoderm was cultured alone, no Otx2 expression was detected (Fig. 4A). Very weak Otx2 expression was detected in ≈50% of the ectoderm pieces cultured alone (Fig. 4B). As Otx2 is expressed in early streak stage ectoderm but is not maintained unless it receives a signal(s) from the anterior mesendoderm (7), the weak expression in the ectoderm explants cultured alone presumably represents residual Otx2 expression. When early streak stage ectoderm was combined with Cerr1-expressing somitic-presomitic mesoderm, strong Otx2 expression was seen in 31 of 32 recombinants explants (Fig. 4C). To test whether this activity was specific to the Cerr1-expressing somitic mesoderm, non-Cerr1-expressing somitic mesoderm located 6–7 somites anterior to the somite-presomite boundary was combined with competent ectoderm. In these experiments, 0/12 recombinants expressed Cerr1 above background levels (Fig. 4D). We also performed recombination assays using posterior presomitic mesoderm. In these recombinations, Otx2 expression was detected in ≈50% of the recombinants (Table 1). As there are no morphological boundaries in the presomitic mesoderm, the mesodermal component may have contained some Cerr1-expressing cells or alternatively Cerr1 may have become expressed in the posterior presomitic mesoderm after being explanted. These results indicate that the somitic-presomitic mesoderm that expresses Cerr1 has anterior neuralizing ability.

Table 1.

Otx2 expression in germ layer explants

| Type of explant | No. expressing/ no. of explants |

|---|---|

| Somitic-presomitic mesoderm + early streak ectoderm | 31/32 |

| Mature somitic mesoderm + early streak ectoderm | 0/12 |

| Posterior presomitic mesoderm + early streak ectoderm | 5/9 |

| Somitic-presomitic mesoderm | 0/11 |

| Mature somitic mesoderm | 0/11 |

| Posterior presomitic mesoderm | 0/11 |

| Early streak ectoderm | 6*/15 |

6/15 early streak ectoderm explants had weak residual Otx2 expression that was used as a baseline for determining expression in recombinants.

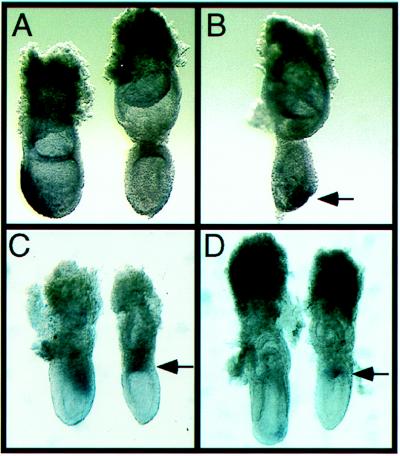

Figure 4.

Maintenance of Otx2 expression in ectoderm explants recombined with Cerr1-expressing somitic-presomitic mesoderm. (A) Somitic-presomitic mesoderm region explant from an E9.5 embryo cultured alone and assayed for Otx2 expression by whole mount RNA in situ hybridization. No Otx2 expression was detected in the explants. (B) Early streak ectoderm explant cultured alone and then assayed for Otx2 expression. Weak expression can be detected in some ectoderm pieces. As Otx2 is expressed in early streak ectoderm before isolation, the weak expression seen in the top two explants presumably represents residual expression present after 30 hr in culture. (C) Somitic-presomitic mesoderm that expresses Cerr1 is able to maintain Otx2 expression in early streak ectoderm. (D) Non-Cerr1 expressing somitic mesoderm is unable to maintain Otx2 expression in early streak ectoderm. The weak signal present in the bottom two recombinants presumably represents residual Otx2 expression in the ectoderm.

Regulation of Cerr1 Expression in Lim1−/− Embryos.

Lim1-deficient embryos lack anterior neural structures including the forebrain, midbrain and part of the hindbrain (9). To determine whether Cerr1 expression was altered in Lim1−/− embryos, whole mount RNA in situ hybridization was performed on E6.5 and E7.5 wild-type and Lim1−/− embryos. In 12/14 Lim1−/− embryos examined, Cerr1 was either not expressed or was weakly expressed in a few scattered cells in the presumptive anterior visceral endoderm and the definitive endoderm regions (Fig. 5A). In two Lim1−/− embryos however, a patch of cells that strongly expressed Cerr1 was seen just anterior of the primitive streak (Fig. 5B). These results demonstrate that Cerr1 expression is altered in Lim1−/− embryos but indicate that Lim1 is not absolutely required for Cerr1 expression.

Figure 5.

Expression of Cerr1 in Lim1−/− embryos. (A) E7.5 wild-type (Left) and Lim1−/− (Right) embryos assayed for Cerr1 expression by whole mount RNA in situ hybridization. Weak or no expression was observed in 12/14 E6.5 and E7.5 Lim1−/− embryos. In some mutant embryos, a few Cerr1-positive cells were seen in the central portion of the epiblast and also near the distal tip region that may correspond to the anterior visceral endoderm region. (B) Late streak stage Lim1−/− embryo expressing Cerr1 in a region just anterior to the primitive streak. (C) follistatin expression in mid-streak embryos. In the wild-type embryo (Left), follistatin is expressed in the posterior portion of the primitive streak. In the Lim1−/− embryo (Right) follistatin is expressed in a region of the Lim1−/− embryo that corresponds to the posterior region of the primitive streak (9). (D) chordin expression in mid-streak stage embryos. In the wild-type embryo (Left), chordin is expressed in a small region at the anterior portion of the primitive streak. In the Lim1−/− embryo (Right), chordin is expressed like goosecoid (9) in the region between the embryonic and extraembryonic region. Arrows indicate regions of gene expression. In all embryos, anterior is to the left and posterior to the right.

In Xenopus, follistatin, chordin, and noggin can up-regulate cerberus expression (18). To determine whether the altered Cerr1 expression seen in Lim1−/− embryos might be a consequence of altered follistatin, chordin, or noggin expression, we analyzed the expression of these genes in mid- to late streak Lim1−/− embryos. Mid- to late streak embryos were chosen for study because germ layer explant experiments indicate that anterior ectoderm becomes committed to form anterior neural tissue by these stages (6). Although the primitive streak in Lim1−/− embryos is shifted more posteriorly, perhaps due to the constriction between the embryonic and extraembryonic regions, we found that both follistatin and chordin were expressed in the appropriate part of the primitive streak relative to other primitive streak specific markers like Brachyury and goosecoid that were analyzed previously (9). Follistatin was expressed in the posterior portion of the primitive streak of wild-type embryos (35) and in the equivalent region of the streak in Lim1−/− embryos (Fig. 5C). Chordin expression was localized to the anterior portion of the primitive streak in wild-type and in the corresponding region of Lim1−/− embryos (Fig. 5D). We were unable to detect noggin expression in mid- to late streak wild-type or Lim1−/− mutant embryos (data not shown). These results suggest that Cerr1 is unlikely to be regulated by follistatin, chordin, or noggin.

DISCUSSION

We have identified a mouse cerberus-related gene that we have named Cerr1. As Cerr1 and cerberus share modest sequence homology, it is unclear whether Cerr1 is the mouse homolog of cerberus or only a cerberus gene family member. The predicted amino acid sequences of the two vertebrate genes are 48% identical over a 110-amino acid region and share nine conserved cysteine residues. Despite the modest homology, the expression of Cerr1 in the anterior endoderm of early gastrula stage embryos, its colocalization in tissues with anterior neuralizing ability and its altered expression in Lim1−/− mice suggest that Cerr1 may indeed be the mouse homolog of cerberus.

The initial phase of Cerr1 expression in early gastrulation stage mouse embryos is similar to cerberus expression in Xenopus gastrula stage embryos. At the start of gastrulation in the mouse, Cerr1 is expressed in the anterior visceral endoderm. A number of other genes with a role or a suspected role in anterior axis formation are also expressed in this region. These genes include Otx2 (7), Lim1 (9), Rpx/Hesx1 (29, 30), nodal (31), goosecoid, and HNF3β (32). The visceral endoderm is a layer of primitive endoderm that surrounds the pregastrula epiblast (36). It does not ingress through the primitive streak and is replaced by the definitive endoderm from the anterior portion of the streak during gastrulation (37). In Xenopus gastrula stage embryos, cerberus is expressed in the anterior-most endoderm that does not involute during gastrulation. It is tempting to speculate that this noninvoluting anterior endoderm in Xenopus is homologous to the noningressing anterior visceral endoderm in the mouse. The fate of the cells in these two regions are different however. In Xenopus, the anterior endoderm that expresses cerberus is fated to form foregut, liver, and midgut (18) while in the mouse, the anterior visceral endoderm is fated to form yolk sac endoderm (30, 37).

During the second phase of expression, at the mid- to late streak stage, Cerr1 is expressed in the anteriorly migrating definitive endoderm. The fate of the anterior definitive endoderm is gut endoderm (37), therefore this phase of Cerr1 expression in the mouse may be most similar to cerberus expression in Xenopus. By the early neural plate stage, Cerr1 is expressed in both the midline mesendoderm and the anterior lateral endoderm. In Xenopus, cerberus is expressed in both the anterior and lateral endoderm (18). The expression patterns of the two gene do differ somewhat at this stage though. In mouse, Cerr1 is expressed in the midline but not in the presumptive cardiac region. In Xenopus, cerberus is excluded from the midline mesendoderm and is expressed in the presumptive cardiac region. The discrepancy in the midline expression may be due in part to staging differences because by the early headfold stage Cerr1 expression is excluded from the presumptive notochord region of mouse embryos.

A third phase of Cerr1 expression occurs during somitogenesis. In early somite stage embryos and continuing through E9.5, Cerr1 is expressed in the two most newly formed somites and also in the anterior presomitic mesoderm. In Xenopus, cerberus expression was undetectable by stage 14 (18) when somitic mesoderm begins to form (38). The Notch1 and Notch2 genes are expressed in a manner similar to Cerr1 during somitogenesis. Notch1 is expressed highly in the presomitic mesoderm (39, 40) while Notch2 is expressed most highly in the most recently formed somites (41). The Notch family of genes encode cell surface receptors involved in cell-cell interactions in Drosophila and C. elegans (42). Targeted mutations of Notch1 in the mouse affects somite formation and organization (41, 43). The association of Cerr1 expression with anterior presomitic mesoderm and the most recently formed somites suggests that Cerr1 may also play a role in coordinating somite formation.

The expression of Cerr1 in the anterior visceral endoderm and anterior definitive endoderm are suggestive of role in anterior neural induction in the mouse. Thomas and Beddington (30) have proposed that the anterior visceral endoderm is involved in the initial induction of anterior neural fates in the mouse. They demonstrated that if part of the anterior visceral endoderm is removed from mid- to late streak stage embryos cultured in vitro, the size of the anterior neural folds was reduced. Varlet et al. (31) also demonstrated a role for the visceral endoderm in anterior neural development. They injected wild-type cells into nodal-deficient blastocysts. As embryonic stem cells do not contribute extensively to the visceral endoderm when injected into blastocysts (44), the visceral endoderm in the chimeras was predominantly made up of nodal-deficient cells. Varlet et al. found that chimeras with a substantial contribution of wild-type embryonic stem cells to the embryo proper and containing nodal-deficient cells in the visceral endoderm had head defects affecting the rostral-most neural structures. Cerr1 expression in the anterior definitive endoderm may also be important in neural induction as suggested by germ layer recombination experiments. Recombination experiments demonstrate that anterior mesendoderm from mid- to late streak embryos can induce En and Otx2 expression in early streak stage ectoderm (6, 7). Thomas and Beddington (30) have postulated that in the mouse the anterior visceral endoderm is responsible for the initial induction of anterior neural identity and that subsequently the anterior mesendoderm maintains and reinforces this anterior neural identity.

A novel finding from our experiments was the observation that in germ layer recombination explants, Cerr1-expressing somitic tissue was able to maintain expression of the anterior neural marker Otx2 in early streak stage ectoderm. This anterior neuralizing ability is specific to the Cerr1 expressing somitic-presomitic mesoderm as more mature somites that no longer express Cerr1 are unable to maintain Otx2 expression. Although these recombination experiments do not demonstrate that Cerr1 is the neuralizing factor, it does demonstrate that the developing somitic mesoderm expresses a factor(s) or a combination of factors that can direct early streak stage ectoderm to develop as anterior neural tissue. The neural tube adjacent to the Cerr1-expressing somitic-presomitic mesoderm does not express Otx2 (7). At this time the neural tube may not be competent to respond to the anterior neuralizing signal or alternatively a posteriorizing neuralizing signal(s) may be dominant over the anterior neuralizing signal. Another intriguing possibility is that the newest formed somites are signaling to the overlying neural tissue and for that matter the other adjacent tissues, in a progressive anterior to posterior manner. Thus, this dynamic mesoderm-derived embryonic structure may provide an integrative mechanism for generating anterior-posterior patterning in the adjacent tissues of vertebrates.

Our rationale for searching for a mouse homolog of cerberus was that cerberus may be a downstream target gene of Lim1 in the head induction pathway. In the mouse, Lim1 is initially expressed in the anterior visceral endoderm like Cerr1. It is not known if they are expressed in the same cells. As gastrulation proceeds, Lim1 is expressed in the node, the primitive streak, the mesodermal wing and the midline anterior mesendoderm (9) whereas Cerr1 is expressed in throughout the anterior endoderm. Because Cerr1 is expressed more widely in the endoderm as gastrulation proceeds, Lim1 cannot be directly regulating Cerr1 expression outside the visceral endoderm. When we examined E6.5 and E7.5 Lim1−/− embryos, we found that in most embryos Cerr1 expression was either absent or restricted to a few cells in the presumptive anterior visceral endoderm and definitive endoderm regions. These results suggest that the anterior endoderm cells may be incorrectly specified in Lim1−/− embryos or alternatively that interactions between germ layers are required for the maintenance of Cerr1 expression. Future studies will be directed at understanding the regulation of Cerr1 during early gastrulation and the creation of knockout mice to determine whether Cerr1 has an essential function in anterior neural development and somite formation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Randy Johnson for the Cerr1 EST clone, Akihiko Shimono for the E7.5 mouse cDNA library, Yuanhao Li for RNA samples and the mouse interspecific mapping panel Southern membrane, and Yuji Mishina for computer graphics help. In addition, we thank Siew-Lan Ang, Hai Wang, Zhoufeng Chen, Marty Matzuk, Rosa Beddington, and Richard Harland for probes. We also thank Lucy Rowe of the Jackson Laboratory for assistance with gene mapping. The DNA Sequencing Core facility at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center is supported by the National Cancer Institute Grant CA16672. This work was supported by a research grant from the Human Frontier Science Program.

ABBREVIATIONS

- E

embryonic day

- EST

expressed sequence tag

Footnotes

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. AF031896).

References

- 1.Spemann H, Mangold H. Wilhelm Roux Arch Entwicklungsmech Org. 1924;100:599–638. doi: 10.1007/BF02080953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nieuwkoop P D. J Exp Zool. 1952;120:83–108. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mangold O. Naturwissenschaften. 1933;43:761–766. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eyal-Giladi H. J Arch Biol. 1954;65:180–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hemmati-Brivanlou A, Stewart R, Harland R M. Science. 1990;250:800–802. doi: 10.1126/science.1978411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ang S-L, Rossant J. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1993;118:139–149. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ang S-L, Conlon R A, Jin O, Rossant J. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1994;120:2979–2989. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.10.2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes J D, Crosby J L, Jones M, Wright C V E, Hogan B L M. Dev Biol. 1994;161:168–178. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shawlot W, Behringer R R. Nature (London) 1995;374:425–430. doi: 10.1038/374425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acampora D, Mazan S, Lallemand Y, Avattaggiato V, Maury M, Simeone A, Brulet P. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1995;121:3279–3290. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.10.3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuo I, Kuratani S, Kimura C, Takeda N, Aizawa S. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2646–2658. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.21.2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ang S-L, Jin O, Rhinn M, Daigle N, Stevenson L, Rossant J. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1996;122:243–252. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith W C, Harland R M. Cell. 1992;70:829–840. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemmati-Brivanlou A, Kelly O G, Melton D A. Cell. 1994;77:283–295. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90320-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasai Y, Lu B, Steinbeisser H, Geissert D, Gont L K, De Robertis E M. Cell. 1994;79:779–790. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90068-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piccolo S, Sasai Y, Lu B, De Robertis E M. Cell. 1996;86:589–598. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80132-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmerman L B, De Jesus-Escobar J M, Harland R M. Cell. 1996;86:599–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bouwmeester T, Kim S, Sasai Y, Lu B, De Robertis E M. Nature (London) 1996;382:595–601. doi: 10.1038/382595a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altshul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rowe L B, Nadeau J H, Turner R, Frankel W N, Letts V A, Eppig J T, Ko M S H, Thurston S J, Birkenheimeier E H. Mamm Genome. 1994;5:253–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00389540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Lemaire P, Behringer R R. Dev Biol. 1997;188:85–89. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilkinson D G, editor. In Situ Hybridization, A Practical Approach. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 1992. pp. 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sasaki H, Hogan B L M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1993;118:47–59. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kozak M. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8125–8132. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.20.8125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyon M F, Kirby M C. In: Genetic Variants and Strains of the Laboratory Mouse. Lyon M F, Rastan S, Brown S D M, editors. Vol. 2. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 1996. pp. 881–923. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hollander W F, Strong L C. J Hered. 1951;42:179–182. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berry R J. Genet Res. 1960;1:439–451. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olopade O I, Bohlander S K, Pomykala H, Maltepe E, Van Melle E, Le Beau M M, Diaz M O. Genomics. 1992;14:437–443. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(05)80238-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hermesz E, Mackem S, Mahon K A. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1996;122:41–52. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas P, Beddington R S P. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1487–1496. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(96)00753-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varlet I, Collignon J, Robertson E J. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1997;124:1033–1044. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.5.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Filosa S, Rivera-Perez J A, Gomez A P, Gansmuller A, Sasaki H, Behringer R R, Ang S-L. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1997;124:2843–2854. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.14.2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lints T J, Parsons L M, Hartley L, Lyons I, Harvey R P. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1993;119:419–431. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.2.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parameswaran M, Tam P P L. Dev Genet. 1993;17:16–28. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020170104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albano R M, Arkell R, Beddington R S P, Smith J C. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1994;120:803–813. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hogan B, Beddington R, Constantini F, Lacy E. Manipulating the Mouse Embryo. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lawson K A, Meneses J J, Pederson R A. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1991;113:891–911. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.3.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hausen P, Riebesell M. The Early Development of Xenopus laevis. Berlin: Springer; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Franco del Amo F, Smith D E, Swiatek P J, Gendron-Maguire M, Greenspan R J, McMahon A P, Gridley T. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1992;115:737–744. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.3.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reaume A G, Conlon R A, Zirngibl R, Yamaguchi T P, Rossant J. Dev Biol. 1992;154:377–387. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90076-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swiatek P J, Lindsell C E, Franco del Amo F, Weinmaster G, Gridley T. Genes Dev. 1994;8:707–719. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.6.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenwald I, Rubin G M. Cell. 1992;34:435–444. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conlon R A, Reaume A G, Rossant J. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1995;121:1533–1545. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beddington R S P, Robertson E J. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1989;105:733–737. doi: 10.1242/dev.105.4.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]