ABSTRACT

Echinococcus granulosus, which causes cystic echinococcosis, is an uncommon condition in the United States. We report a case of a 78-year-old Caucasian female who presented to her primary care physician in 1999 with right upper quadrant pain. She had a history of frequent foreign travel. Abdominal imaging demonstrated a 12.5-cm hepatic cyst. The cyst was drained and the pathology report on the fluid indicated no bacterial, parasitic, or malignant etiology. Serology tests for and antibodies were negative. The patient underwent multiple hepatic cyst aspirations until 2008 for recurring symptoms. In 2008, abdominal imaging demonstrated solid internal components within the cyst. Repeat antibodies ordered were abnormally elevated. Cyst aspiration demonstrated . We report this case to discuss the diagnosis and management of hydatid cyst and to emphasize that with increasing globalization, physicians must maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for parasitic etiologies in patients with hepatic cysts.

KEY WORDS: hydatid cyst, echinococcus granulosus, hepatic cyst, travel medicine

INTRODUCTION

Echinococcus granulosus which causes cystic echinococcosis is a member of the smallest tapeworms in the Taeniidae family, and its larval stage, the metacestode, is responsible for zoonotic infection in humans.1 Hydatid disease can be found worldwide; particularly in grazing areas where dogs, the definitive host, have access to intermediate hosts such as sheep, goats, other herbivores, and humans. The prevalence of infection varies widely among different countries and in different areas, ranging from 1 to 220 per 100,000 in certain regions. In the United States, the majority of cases are seen in the immigrant population. This is an uncommon condition in the United States having occurred in Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, California, Alaska, and the lower Mississippi Valley; however, it is endemic in Central Asia, South America, the Mediterranean basin, and regions of Africa.2

When the larvae position themselves within the organ, they produce multiloculated fluid-filled cysts.3 Hydatid cysts form in the liver in 45% to 75% of patients or in the lung in 10% to 50% of patients and the remaining 10% are typically located in other organs.1,4 Additionally, 80% of infections involve a single organ; whereas, 20% involve multiple organs.5 Moreover, the cysts have documented predilections to the right lobe of the liver (60–80%), right lung (>50%), and lower lobes of the lungs (>50%).6

The standard diagnostic approach for cystic echinococcosis involves imaging techniques, predominantly ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), X-ray examinations, and confirmation by detection of specific serum antibodies by immunodiagnostic tests. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test using hydatid cyst fluid has a high sensitivity (>95%) but its specificity is often unsatisfactory. Finding a cyst using ultrasound, X-ray, or CT is typically expected in infection.7 Imaging findings of include single, unilocular cyst or multiseptated cysts, with “wheel," "rosette-like,” or “honeycomb” appearances; “snowflake” sign, with free floating protoscoleces (hydatid-sand) within the cyst cavity; degenerating cysts with wavy or serpentine bands; floating membranes indicating detached or ruptured membranes; or dead cysts indicating a calcified cyst wall.3

Clinical management of hepatic cysts includes albendazole therapy in combination with either surgical resection or the puncture aspiration injection re-aspiration (PAIR) procedure. Larger cysts (diameter >10 cm) preferably undergo surgical resection.2,8 Asymptomatic individuals may undergo an observation approach with supervision.9

We report this case to discuss the diagnosis and management of hydatid cyst and to emphasize the importance of globalization and its impact on the spread of infectious agents, thus necessitating awareness amongst internists of diseases that are common in other parts of the world.

CASE PRESENTATION

In 1999, a 78-year-old Caucasian female presented to her primary care physician with right upper quadrant (RUQ) and right flank pain of acute onset and duration of 5 days. She denied any gastrointestinal symptoms including nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea. There was no history of fever, chills, or night sweats. The pain was constant, without radiation, worsened with light exercise, and was mildly relieved with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. She had a history of frequent travel to Kenya and India over a period of three years, from 1988 to 1991. While in Kenya in 1988, she developed bloody diarrhea and received no specific treatment but managed her symptoms with diphenoxylate hydrochloride and atropine sulfate. Review of the records in 1999, when she presented to our facility, shows that physical examination demonstrated mild tenderness in the RUQ, nonspecific bulging of the RUQ area and fullness, no peritoneal signs, and a positive Murphy’s sign. No cutaneous stigmata of liver disease, scleral icterus. or palpable adenopathy were present. Complete blood cell count, electrolytes, eosinophil count, serum biochemistry, and urinalysis were normal. A stool parasite examination, leukocytes, and toxin culture were negative. Abdominal ultrasound demonstrated a sharply marginated, completely anechoic, thin-walled, 11 × 12 cm cystic mass lying within the RUQ between the liver and right kidney. Abdominal CT demonstrated a large sharply marginated simple cyst arising from the right lobe of the liver extending into the subhepatic space. The cyst measured 12 × 12.5 cm in its various diameters and had no aggressive or neoplastic features. Two days after the radiologic studies, the patient underwent CT-guided percutaneous drainage of the hepatic cyst with removal of 800 cc of benign appearing fluid. Her pain was relieved upon drainage of the cyst. Pathologic reports were negative for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures. No other abdominal or pelvic abnormalities were detected on the CT scan.

Six months later (12/1999), follow-up ultrasound studies demonstrated the recurrence of a simple, benign, hepatic cyst measuring 8 cm. The patient was asymptomatic. It was decided to re-aspirate the hepatic cyst and send the fluid for parasite analysis secondary to her history of bloody diarrhea years ago. Additionally, serology tests for and were ordered as well as stools for ova and parasite examination. Laboratory studies indicated negative amoebic and echinococcus antibodies. The stools were negative for ova and parasites. At this stage, considering the cyst size, absence of radiographic features of hydatid cyst and two negative serologies, it was decided to manage the patient as a case of a simple liver cyst with close monitoring. Eight months later (08/2000), another CT-guided percutaneous drainage was performed for symptomatic relief and 200 cc of yellowish colored fluid was removed.

In February 2004, the patient remained asymptomatic and another CT scan of the abdomen with contrast was performed to compare the hepatic cyst with the prior studies. The CT showed a large simple cyst measuring 10.4 × 11.6 cm occupying the lower aspect of the right lobe of the liver unchanged in appearance. Three months later (05/2004), she experienced worsening symptoms of RUQ abdominal pain and a repeat abdominal CT scan with contrast demonstrated a minimal increase in cyst size from 10.4 × 11.6 cm to 11.2 × 12.5 cm. A CT-guided cyst drainage was performed, for the fourth time, and 800 cc of cloudy, dark brown colored fluid was removed. The pathology report indicated fragments of hepatic cells and bile ducts but was negative for atypia, malignancy, or infectious etiology. Subsequently, the patient underwent ultrasound-guided drainage of the cyst annually for symptomatic relief (Table 1).

Table 1.

Graphical Representation of Timeline, Hepatic Cyst Size, Amount of Fluid Drained on Cyst Aspiration, Serological and Cyst Fluid Analysis, Corresponding Figure

| Year/Month | Hepatic cyst Size (cm) | Drainage amount (cc) | Serology and fluid analysis | Imaging |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 06/99 | 12 × 12.5 | 800 | Negative stains and serology | |

| 12/99 | 8 | 300 | Negative stains and serology | |

| 08/00 | 6 | 200 | N/D | |

| 02/04 | 10.4 × 11.6 | N/A | N/D | |

| 05/04 | 11.2 × 12.5 | 800 | Negative stains; serology N/D | |

| 07/05 | N/D | 1000 | N/D | |

| 05/06 | N/D | 400 | N/D | |

| 05/07 | 12.16 | 1000 | N/D | |

| 04/08 | N/D | 600 | N/D | |

| 06/08 | 13 × 12.7 × 11.4 | 2000 | Protoscolex of ; antibody level 1.7; N < 0.80 | Figures 1, 2, and 3 |

not determined, not applicable, cubic centimeters, centimeters.

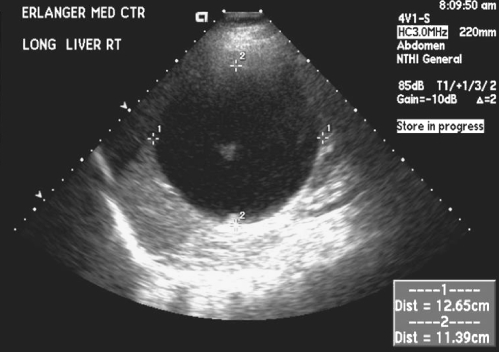

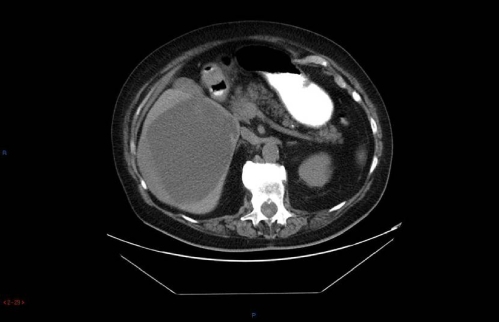

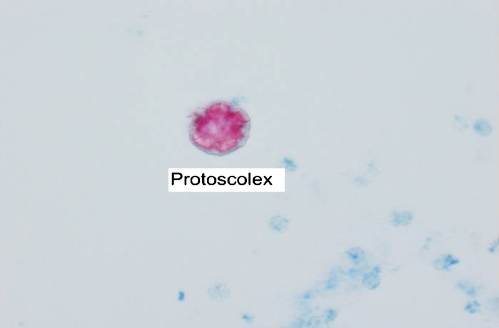

Four years later, in May 2008, the patient presented with increasingly severe abdominal pain. An ultrasound demonstrated a large cystic lesion of the inferior right hepatic lobe with dimensions of 13 × 12.7 × 11.4 cm with solid internal components and debris. No other hepatic lesions were appreciated (Fig. 1). A CT scan without contrast was performed for further evaluation and demonstrated similar findings (Fig. 2). Considering these changes in radiographic appearance of the cyst, which were not present in the past, the patient was referred to a gastroenterologist and based on his recommendation the cyst was aspirated again to re-assess the microbiological aspects of the cyst. Repeat serologies to rule out parasitic infections were also sent. The serology demonstrated normal liver function tests, antibody immunoglobulin G (IgG) 0.15 IU (reference range 0.90 IU or less), alpha fetoprotein 2.0 ng/mL (reference range 0–6 ng/mL), and antibody elevated 1.7 IU (reference range 0.80 IU or less). The patient started albendazole 400 mg twice daily. In June 2008, the cyst was again drained using ultrasound guidance and approximately 2000 cc of brown-colored fluid was withdrawn. The pathology on ThinPrep and cell block demonstrated findings consistent with echinococcal hydatid cyst. An acid fast bacillus (AFB) stain performed on the ThinPrep slide demonstrated one markedly positive structure consistent with a degenerating protoscolex of Echinococcus (Fig. 3). The patient has completed treatment with albendazole and will be followed with repeat CT scans to monitor the cyst size and then perform the PAIR procedure.

Figure 1.

Abdominal ultrasound May 2008. Inferior right hepatic lobe 13 × 12.7 × 11.4 cm cystic lesion with solid internal components (arrow).

Figure 2.

Abdominal computed tomography scan May 2008. Right hepatic cyst unchanged since prior examinations (arrow).

Figure 3.

Acid fast bacillus stain June 2008. Degenerating (arrow).

DISCUSSION

Cystic echinococcosis is a zoonotic illness caused by infection with Echinococcus granulosus. In the life cycle of , humans sometimes become accidental intermediate hosts.9 Humans can orally take up the eggs from infected carnivore excretions by handling the animals or egg-containing feces, plants, eating vegetables, uncooked fruits, and drinking water with the eggs.10,11

Clinically, the patient is typically asymptomatic during the initial stage of infection and may remain so for many years. Studies demonstrate that hepatic cyst size correlates with symptoms; cysts of 4-cm diameter were asymptomatic and cysts of 10-cm diameter were symptomatic. The rate of growth of cysts is variable depending on the strain differences and the organ involved. Typical measurements state that the average cyst growth is 1 cm to 1.5 cm/year.12 Moreover, small, well-encapsulated, or calcified cysts typically do not elicit major pathology.13 Hydatid hepatic cyst symptoms include pain in the upper abdominal region, hepatomegaly, cholestasis, biliary cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and ascites.10 Serious complications include cyst rupture either into the peritoneal cavity resulting in anaphylaxis or secondary cystic Echinococcosis or cyst rupture into the biliary tree resulting in cholangitis and cholestasis.14 When pulmonary hydatid cyst infection occurs, symptoms such as chronic cough, expectoration, dyspnea, hemoptysis, pleuritis, and lung abscess occur. Cerebral hydatid cyst infection can produce symptoms related to a slow-growing space occupying lesion such as seizures and stroke.14

The standard diagnostic approach for cystic Echinococcosis involves combination of imaging techniques and serological analysis.9 Plain films, ultrasound, and CT scans all can play a role in diagnosing hydatid cyst. Each imaging modality has its unique role in assessing hepatic hydatid disease. Plain films can identify liver calcifications.15 Sonography is also useful during the active stage of cyst development because plain X-rays will appear normal or show nonspecific hepatomegaly at this time.15 Sonography can categorize cysts as solitary univesicular, solitary multivesicular, solid echogenic mass, multiple, either uni- or multivesicular, or collapsed, flattened, and calcified.15 The World Health Organization (WHO) expert group on echinococcosis has developed an international classification of ultrasound images in cystic echinococcosis focusing on the active, transitional, and inactive stages of hydatid cyst disease.16 Additionally, sonography is considered the preferred investigatory method because of its low cost. Sonography is superior to CT in observing the cyst wall, hydatid sand, daughter cysts, and the relation of the cyst to the diaphragm; however, CT is superior to sonography in observing gas within the cysts, minute calcifications, and in anatomical mapping.15 There are multiple studies suggesting that CT scan has a higher sensitivity than ultrasound in the diagnosis of hydatid cyst.17,18 The pathognomonic CT findings are the presence of a single cyst (with a wall) and daughter cysts surrounded by a capsule with peripheral calcification (25% of cases), and membrane detachment.7,19 The common features include the cysts being single or multiple and appearing uni- or multilocular. The cyst wall is typically thin and well-defined but may be thick and enhance on CT. Separation of the laminated membrane from the pericyst (connective tissue layer) produces a “split wall appearance.” The daughter cysts are first solid and then develop into a cystic structure and a fluid level may be observed (“hydatid sand”), indicating the presence of free-floating protoscoleces.5 Moreover, layering in a poorly defined cyst signifies an infected or complicated cyst.20

Serological tests are commonly employed to supplement the radiological data in the diagnosis of hydatid cyst. The current gold standard serology test for echinococcosis detects IgG antibodies to hydatid cyst fluid-derive native or recombinant antigen B subunits. This is performed using ELISA or immunoblot formats.16 The lipoproteins antigen B (AgB) and antigen 5 (Ag5) are the major components of hydatid cyst fluid and are the most widely used antigens in current assays for immunodiagnosis of cystic echinococcosis.21 To identify these antigens, multiple serologic tests are used: complement fixation test, immunoelectrophoresis, indirect hemagglutination, latex agglutination, indirect fluorescence test, and enzyme immunoassays such as ELISA test.

There are multiple studies in the published literature that reflect large variability in the sensitivity and specificity of these tests and additional variability between laboratories, producing false results. General consensus states that the ELISA test with crude hydatid cyst fluid has a high sensitivity of 95%; however, its specificity is low at 61.7%.13 If purified antigens (antigen B) or other techniques (immunoblot analysis, detection of IgG4 antibodies, immunoelectropheresis) are used, specificity is improved but average sensitivity is much lower. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for has been utilized in a few countries outside the United States, but to our knowledge PCR for is being utilized only for research purposes in United States and is not available commercially.22 Ten percent to 20% of patients with hepatic cysts do not produce detectable specific serum antibodies (IgG) and thus give false-negative results.13,14

There are specific findings in the hydatid cysts that may lead to negative serologies. General consensus points to an association between heavily calcified liver cysts and negative serology. One study using indirect hemagglutination assay noted that false-negative serology correlated with age less than 10 years or greater than 20 years, single cyst, cystic size less than 9 cm, intact cysts, cysts in extrahepatic locations, and unilocular or degenerative cyst in comparison with multivesicular types.23,24 Additionally, 10% to 15% false-positive results occur because of cross-reactions with helminth infections (cysticercosis) and noninfectious conditions (cancer, pregnancy, autoimmune diseases).24

As demonstrated in our patient, aspirated cyst fluid can be evaluated for protoscoleces, rostellar hooks, and antigens or DNA. This procedure is useful as a diagnostic method in doubtful cases of cystic echinococcosis, in the absence of detectable anti- antibodies, in patients with small lesions resembling hepatic cysts, and in patients with lesions that are difficult to distinguish from liver abscess, neoplasms, or other conditions.14,25

Clinical management of hepatic cysts includes albendazole or mebendazole therapy in combination with either surgical resection or the PAIR procedure. Larger cysts (diameter >10 cm) preferably undergo surgical resection.2,8 As physician experience with the PAIR procedure has grown, the rates of complications have decreased and the PAIR procedure is becoming the first-line treatment for hepatic hydatid cyst.26 Mebendazole and albendazole are the two most commonly used drugs to treat . Multiple studies have shown albendazole to be superior to mebendazole in efficacy.27,28 Problems associated with chemotherapy include adverse reactions like hepatotoxicity, reversible leukopenia, and hair loss in addition to an inconsistent intracystic drug level. A small prospective study has shown that combining albendazole with percutaneous drainage results in better outcomes.29 There are no published guidelines regarding empiric treatment based on radiographic and clinical findings; however, anecdotal evidence exists outside of the United States that supports the employment of empiric therapy.30 Additionally, there are no published guidelines regarding serial imaging in asymptomatic patients with hepatic hydatid cysts.

This was a very unusual case of isolated hydatid cyst of the liver. In retrospect, an empiric trial of PAIR procedure or chemotherapy might have obviated the long delay in diagnosis. Empiric treatment for hydatid cyst in a case of high pretest probability and negative serological studies should be considered. The world is now functioning as a global village and endemic diseases are no longer limited by geographic boundaries. Primary care physicians need to maintain a high index of clinical suspicion in patients with recurring hepatic cysts and foreign travel exposure.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Written consent from the patient was obtained for publication of this case report. The abstract was presented as an oral presentation at both the Tennessee chapter of the American College of Physicians regional meeting in September 2008 and the regional meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine in February 2009. In addition, the abstract was presented as a poster at the national meeting of the American College of Physicians in April 2009.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dionigi G, Carrafiello G, Recaldini C, et al. Laparoscopic resection of a primary hydatid cyst of the adrenal gland: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2007;1:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Sheng Y, Gerber DA. Complications and management of an echinococcal cyst of the liver. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(6):1222–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Czermak BV, Akhan O, Hiemetzberger R, et al. Echinococcosis of the liver. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33(2):133–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Tiseo D, Borrelli F, Gentile I, Benassai G, Quarto G, Borgia G. Cystic echinococcosis in humans: our clinic experience. Parassitologia. 2004;46(1–2):45–51. [PubMed]

- 5.Mishra SK, Satyprakash MVS, Mahesh N, et al. Hydatid cysts of the liver complicating with inferior venacaval thrombous and right ventricular outflow obstruction, posted for emergency laporotomy. Internet J Anesthesiol. 2008;16:1.

- 6.Halperin A, Bilesio EA. Separate hydatid cysts coexistent in the lower lobe of the right lung & the upper face of the hepatic lobe: surgical tactics & technic used in simultaneous treatment of both processes. Prensa Med Argent. 1958;45(46):3605–9. [PubMed]

- 7.Pandolfo I, Blandino G, Scribano E, Longo M, Certo A, Chirico G. CT findings in hepatic involvement by Echinococcus granulosus. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1984;8(5):839–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.De Rosa F, Teggi A. Treatment of Echinococcus granulosus hydatid disease with albendazole. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1990;84(5):467–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Eckert J, Deplazes P. Biological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(1):107–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Conn DB. Cestode infections of mammary glands and female reproductive organs: potential for vertical transmission? J Helminthol Soc Wash. 1994;61:162–8.

- 11.Eckert J, Gottstein B, Heath D, Liu FJ. Prevention of echinococcosis in humans and safety precautions. In: Eckert J, Gemmell MA, Meslin F-X, Pawlowski ZS, eds. WHO/OIE Manual on Echinococcosis in Humans and Animals: a Public Health Problem of Global Concern. Paris: World Organization for Animal Health; 2001:238–47.

- 12.http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/216432-overview. Access date: 01/21/09.

- 13.Ammann RW, Eckert J. Cestodes: echinococcus. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1996;25:655–89. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Pawlowski ZS, Eckert J, Vuitton DA, et al. Echinococcosis in humans: clinical aspects, diagnosis and treatment. In: Eckert J, Gemmell MA, Meslin FX, Pawlowski ZS, eds. WHO/OIE Manual on Echinococcosis in Humans and Animals: a Public Health Problem of Global Concern. Paris: World Organization for Animal Health; 2001:20–66.

- 15.Suwan Z. Sonographic findings in hydatid disease of the liver: comparison with other imaging methods. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1995;89(3):261–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Craig PS, McManus DP, Lightowlers MW, et al. Prevention and control of cystic echinococcosis. Lancet. 2007;7:395–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Dhar P, Chaudhary A, Desai R, et al. Current trends in the diagnosis and management of cystic hydatid disease of the liver. J Commun Dis. 1996;28:221. [PubMed]

- 18.Safioleas M, Misiakos E, Manti C, et al. Diagnostic evaluation and surgical management of hydatid disease of the liver. World J Surg. 1994;18:859–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Scherer U, Weinzierl M, Sturm R, Schildberg FW, Zrenner M, Lissner J. Computed tomography in hydatid disease of the liver: a report on 13 cases. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1978;2(5):612–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Beggs I. The radiological appearances of hydatid disease of the liver. Clin Radiol. 1983;34(5):555–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Zhang W, Li J, McManus DP. Concepts in immunology and diagnosis of hydatid disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16(1):18–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Gottstein B. Molecular and immunological diagnosis of echinococcosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Mzali R, Ben Amar M, Kallel W, Kolsi K, Beyrouti MI, Ayadi A. Liver cystic echinococcosis: which cysts are correlated with false negative indirect passive hemagglutination (IHA)? Tunis Med. 2007; 85(5):367–70. [PubMed]

- 24.Mamuti W, Yamasaki H, Sako Y, et al. Usefulness of hydatid cyst fluid of Echinococcus granulosus developed in mice with secondary infection for serodiagnosis of cystic Echinococcosis in humans. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9(3):573–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Siles-Lucas MM, Gottstein B. Molecular tools for the diagnosis of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:463–75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Filice C, Brunetti E. Use of PAIR in human cystic echinococcosis. Acta Tropica. 1997;64:95–107. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Todorov T, Vutova K, Mechkov G, et al. Chemotherapy of human cystic echinococcosis: comparative efficacy of mebendazole and albendazole. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1992;86:59. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Liu LX, Weller PF. Antiparasitic drugs. N Eng J Med. 1996;334:1178. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Khuroo MS, Dar MY, Yattoo GN, et al. Percutaneous drainage versus albendazole therapy in hepatic hydatidosis: a prospective, randomized study. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1452. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Zingg W, Kellenberger C, Frey B, et al. A 7-year-old girl with dyspnea and rash. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(1):73–4, 129–30. [DOI] [PubMed]