Abstract

Structural characterization of membrane proteins is hampered by their instability in detergent solutions. We modified here a G protein-coupled receptor, the BLT1 receptor of leukotriene B4, to stabilize it in vitro. For this, we introduced a metal-binding site connecting the third and sixth transmembrane domains of the receptor. This modification was intended to restrain the activation-associated relative movement of these helices that results in a less stable packing in the isolated receptor. The modified receptor binds its agonist with low-affinity and can no longer trigger G protein activation, indicating that it is stabilized in its ground state conformation. Of importance, the modified BLT1 receptor displays an increased temperature-, detergent-, and time-dependent stability compared with the wild-type receptor. These data indicate that stabilizing the ground state of this GPCR by limiting the activation-associated movements of the transmembrane helices is a way to increase its stability in detergent solutions; this could represent a forward step on the way of its crystallization.

Keywords: GPCR; G protein; activation, structure; stability

Introduction

G protein-coupled receptors are versatile biological sensors that are responsible for the majority of cellular responses to hormones and neurotransmitters as well as for the senses of sight, smell and taste.1 A limited number of GPCR crystal structures have been published so far.2–9 Although these structures represent a very important step in this way, more information is still needed to assess the molecular mechanisms governing the function of this membrane protein family.

As recently emphasized,10 molecular analyses of GPCRs involve overcoming several technical barriers, among them the stabilization of the native fold out of a membrane environment. Different approaches have been developed so far to stabilize membrane proteins in solution. One possibility to alleviate protein unfolding by classical detergents is to use less aggressive surfactants.11–14 An alternative approach consists in mutating the protein to increase its stability in a wide range of conditions. This approach has been recently applied to several GPCRs including rhodopsin,15 the β1-adrenergic,16 and A2a adenosine receptors.17

Another problem associated with purified GPCRs is that the receptors probably adopt a whole range of different micro-conformations,18 and this conformational heterogeneity is certainly detrimental to crystallization. Improving the stability of a purified receptor therefore implies stabilizing it in essentially one conformation, preferably the inactive one that is probably the most stable.16 Activation of GPCRs involves, among others, relative movements of the TM3 and TM6 segments (Ref. 18 and references therein). A possibility to block GPCR activation therefore is to block such relative movements. This has been done by engineering either disulfide bonds or cation-binding sites connecting the cytoplasmic ends of TM3 and TM6 (Ref. 19 and references therein).

BLT1 is a membrane G protein-coupled receptor for leukotriene B4.20 LTB4 is a potent activator and chemoattractant for leukocytes and is involved in several inflammatory diseases as well as in proliferation of transformed cells.21 BLT1 therefore represents an important target in the context of drug design. We have produced BLT1 as a purified recombinant protein in E. coli with yields allowing structural studies to be carried out.22 However, as stated above, an analysis of the structure of BLT1 requires the receptor to be stable in detergent solutions under conditions compatible with crystallization assays. We previously explored the role of surfactants on BLT1 stability.13 To achieve the highest stability of the purified BLT1 receptor in detergent solutions, we explored here the complementary approach that consists in producing a mutant of the receptor stabilized in its ground state. This was done by creating a cation-binding site connecting the cytoplasmic ends of TM3 and TM6. The mutant receptor is no longer able to trigger G protein activation and binds its agonist ligand with low affinity, indicating that the conformation stabilized is indeed the ground one. Of importance, the modified receptor displays a significantly increased stability in detergent solutions, making it a good candidate for further structural characterization.

Results

Engineering the metal-ion binding site in BLT1

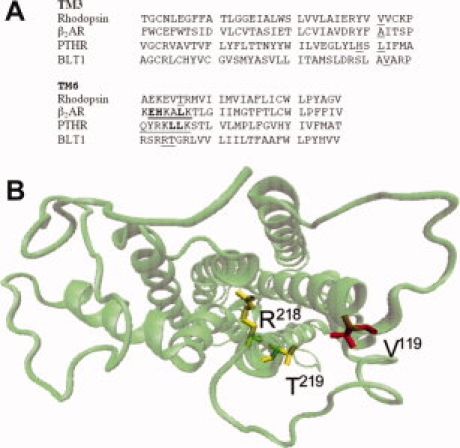

To connect the TM3 and TM6 segments of BLT1 through a metal-ion binding site, we first selected the position of the residues to be modified on the basis of a three-dimensional model of the receptor. The BLT1 model was elaborated using rhodopsin crystal structure as a template (see Discussion section). The α-carbons of the residues composing the high-affinity triads are to be separated by less than 13 Å to allow the corresponding imidazole side chains to coordinate a metal ion.23 On this basis, we selected here three different residues, V119, R218, and T219, to engineer the metal-binding site in BLT1. V119 is located in TM3 whereas R218 and T219 are both in TM6 (see Fig. 1). Based on the three-dimensional model of BLT1, the distance between the α-carbon of V119 and R218, on the one hand, and V119 and T219, on the other hand, are about 11 and 9 Å, respectively [Fig. 1(B)]. These residues were replaced by histidines; the resulting mutant receptor was expressed, purified, and refolded in similar conditions than the wild-type one.

Figure 1.

Location of the mutated residues. A: Alignment of the TM3 and TM6 segments of rhodopsin, β2-adrenergic, PTH and BLT1 receptors. The sequences of human BLT1, bovine rhodopsin, human β2-adrenergic receptor, and opossum PTHR were aligned using Clustal W.24. The residues mutated in each receptor are underlined. The residues in the TM6 segment of the β2-adrenergic and PTH receptors directly involved in cation coordination are given in bold.19 B: Model of the 7TM helices showing the position of the mutated residues in TM3 and TM6. The model is presented from the cytoplasmic face. The residues in TM3 (V119) and TM6 (R218 and T219) that have been replaced by histidines are indicated. The figure in (B) was prepared in VMD.25

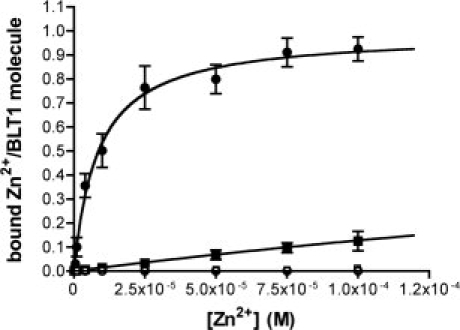

Zn2+-binding properties of the modified BLT1 receptor

We first analyzed if introducing the histidine residues indeed created a divalent cation-binding site. For this, Zn2+ titrations experiments were performed using a fluorescence-based assay with the Zn2+-binding chromophore mag-fura-2.26 As shown in Figure 2, the wild-type receptor displayed no detectable Zn2+-binding. In contrast, BLT1His readily bound Zn2+ ions. In this case, the titration plot indicates the occurrence of a single cation-binding site per receptor with an affinity of 8 μM for Zn2+.

Figure 2.

Zn2+-binding to the wild-type and mutant BLT1. Mag-fura 2-monitored Zn2+ binding to BLT1 (open squares), BLT1V119H (open circles), BLT1R218H, T219H (closed squares), and BLT1V119H, R218H, T219H (closed circles). The data are presented as the amount of Zn2+ bound per receptor molecule (molar Zn2+-to-BLT1 ratio) as a function of Zn2+ concentration. Data represent the mean SE from three independent experiments.

Blocking the relative movements of the TM3 and TM6 segments requires the divalent cation to be coordinated by histidine residues in these two helical domains. The occurrence of a single cation-binding site is compatible with the histidines both in TM3 and in TM6 participating to Zn2+ binding. To further assess whether the cation-binding site in BLT1His indeed involves the histidines in TM3 and TM6, we compared the Zn2+-binding properties of the triply mutated V119H, R218H, T219H receptor to those of mutants with histidines only in TM3 (BLT1 V119H) or in TM6 (BLT1R218H, T219H). As shown in Figure 2, no Zn2+-binding was observed with BLT1V119H. The BLT1R218H, T219H mutant bound Zn2+ but with an affinity significantly lower (ca. 90-fold), than that measured for the triply mutated BLT1His protein (see Fig. 2). All these data indicate that the His residues in TM3 and TM6 in the BLT1His mutant both cooperate in cation binding.

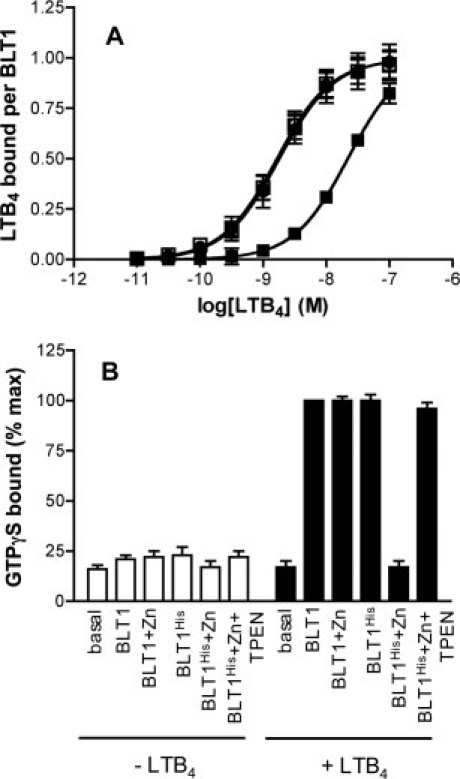

Ligand-binding properties of the modified BLT1 receptor

We subsequently investigated the ligand binding properties of the mutant receptor. The ligand binding assays were carried out in the presence of purified G proteins. The latter are required to stabilize the high-affinity agonist-binding state of BLT1 both in vitro27 and in vivo.28–30 As shown in Figure 3(A), very similar ligand-binding profiles were obtained for both the wild-type receptor (in the absence and presence of Zn2+ ions) and BLT1His in the absence of any divalent cation. The affinity values inferred from these binding profiles were 1.63 ± 0.3 nM (n = 3) and 1.68 ± 0.2 nM (n = 3) for the wild-type and mutant receptors, respectively. These affinity values are within the same range of the Kd previously reported for the high-affinity state of BLT1, for example, 0.99 nM,29, 1.5 nM,30 or 1.2 nM.31 The fact that both receptors display the same affinity for LTB4 indicates that the mutations do not affect BLT1 three-dimensional fold. We then measured the affinity of BLT1His for its agonist in the presence of Zn2+. As shown in Figure 3(A), under these conditions, the mutant receptor bound its LTB4 agonist with about 10-fold decreased affinity compared with either the wild-type receptor or BLTHis in the absence of Zn2+ (Kd = 18.8 ± 2.1 nM; n = 3). This was not due to an indirect effect of Zn2+ on LTB4 binding to BLT1 since the presence of these divalent cations did not affect the pharmacological profile of the wild-type receptor, as expected on the basis of the lack of Zn2+ binding reported in Figure 2 [Fig. 3(A)]. Similarly, about 10–20 fold difference in the Kd value for LTB4 has been observed between the high- and low-affinity states of BLT1 by different authors.28,29 This suggests that introducing a metal-ion binding site between TM3 and TM6 locks the receptor preferentially in its ground state, low-affinity, conformation.

Figure 3.

Agonist binding and receptor-catalyzed G protein activation. A: LTB4-binding to BLT1 (circles) or BLT1His (squares) in the absence (open symbols) or the presence (closed symbols) of 1 mM Zn2+. The binding data are presented as a plot of the amount of LTB4 bound per BLT1 receptor as a function of LTB4 concentration. B: GDP/GTP exchange on Gαi catalyzed by BLT1 or BLT1His in the absence of Zn2+ (BLT1 and BLT1His), in the presence of 1 mM Zn2+ (BLT1 + Zn and BLT1His + Zn), or on successive addition of 1 mM Zn2+ and then 1 mM TPEN (BLT1His + Zn + TPEN), and in the absence (−LTB4) or the presence of 25 μM LTB4 (+LTB4). Data are expressed as the percent of maximal binding GTPγS obtained for the wild-type BLT1 receptor. In all cases, data represent the mean SE from three independent experiments.

G protein-activation properties of the modified BLT1 receptor

We then monitored receptor-catalyzed GTPγS binding by the Gα subunit of purified Gαi2βγ protein.32 Gαi2 couples to BLT1 both in vivo28 and in vitro.27 As shown in Figure 3(B), the wild-type receptor triggered GDP/GTP exchange at the level of Gαi2 in the presence of the LTB4 agonist whether Zn2+ ions were present or not. The same effect was observed for BLT1His in the absence of Zn2+. In contrast, in the presence of Zn2+, the BLT1His receptor was no longer able to trigger G protein activation even in the presence of saturating agonist concentrations, indicating that blocking the relative movements of the TM3 and TM6 prevents receptor-catalyzed G protein activation. As expected if the ground state specifically was to result from Zn2+ binding by the BLT1His protein, the G-protein activation properties were fully restored when the high-affinity Zn2+-specific chelator (TPEN) was added [Fig. 3(B)].

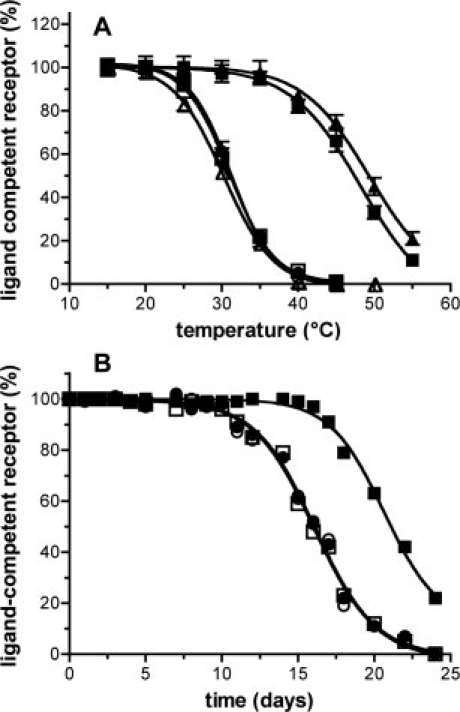

Stability of the modified BLT1 receptor

We subsequently investigated the stability of the isolated BLT1His protein. Purified receptor thermostability was performed using an assay similar to that recently described by Serrano-Vega et al.16 This assay consists in heating the receptors at increasing temperatures, quenching the reaction on ice, and then performing the ligand-binding assay to determine the remaining proportion of ligand-competent receptor. As shown in Figure 4(A), a decrease in the amount in ligand-competent receptor for temperatures above 25–27°C was observed for both the wild-type receptor and BLT1His in the absence of divalent cations. In contrast, BLT1His in the presence of Zn2+ ions was stable up to 38–40°C without any significant loss in activity.

Figure 4.

Stability of BLT1 and BLT1His. A: Temperature-dependent stability of BLT1 (circles) or BLT1His (squares) in the absence (open symbols) or the presence (closed symbols) of 1 mM Zn2+. BLT1 was refolded in either fos-choline-16/asolectin mixed micelles (circles and squares) or in DDM/asolectin mixed micelles receptor (BLT1: open triangles; BLTHis in the presence of 1 mM Zn2+: closed triangles). Data represent the mean SE from three independent experiments. B: Time-dependent stability of BLT1 (circles) or BLT1His (squares) in the absence (open symbols) or the presence (closed symbols) of 1 mM Zn2+.

We then monitored the time-dependent stability of the modified BLT1 receptor by following the ligand-competent receptor fraction as a function of time. Figure 4(B) shows the percent of active receptor as a function of time. In the case of either the wild-type receptor (in the absence or presence of Zn2+ ions) or BLT1His in the absence of Zn2+, a significant decrease in the functional fraction was observed after a 10 days period. In contrast, BLT1His in the presence of Zn2+ was stable with no significant unfolding up to 15–16 days.

We also investigated the stability of BLT1His in different detergents. The first detergent we tested was dodecylmaltoside (DDM). This detergent was selected since similar buffer conditions had been used for both β1-adrenergic and A2a adenosine receptors after introducing stabilizing mutations, thus providing a direct comparison between the three receptors. To achieve detergent exchange, BLT1 refolded in fos-choline-16/asoletin mixed micelles was bound to Ni-NTA agarose and then extensively washed with the same buffer where fos-choline-16 was replaced by DDM. As shown in Figure 4(A), BLT1His in the presence of Zn2+ was stable up to 35–38°C when reconstituted in DDM/asolectin mixed micelles in contrast to the wild-type receptor where unfolding was observed for temperatures above 25°C. The gain of stability compared with the wild-type receptor is in the same range than that reported for the β1-adrenergic and A2a adenosine receptors under similar buffer conditions.

We subsequently analyzed the stability of the mutant receptor in other detergents. As described above for DDM, the receptor refolded in fos-choline-16/asoletin was bound to Ni-NTA agarose and then extensively washed with the same buffer where the detergent had been replaced by either fos-choline-16 (fos16), fos-choline-12 (fos12), DDM (see the earlier section), decylmaltoside (DM), lauryldimethylamine oxide (LDAO), nonylglucoside (NG), or octylglucoside (OG). The fraction of ligand-competent receptor at 20°C was then assessed as described above for the thermostability assays. As shown in Table I, BLT1 was stable only in fos 16, DDM or LDAO with some residual activity in fos 12 and DM; no ligand-competent receptors were observed when the Ni-NTA resin was washed with OG or NG. In contrast, BLT1His in the presence of Zn2+ was fully functional in all detergents with the exception of OG where a reduced fraction of active receptor was detected at the temperature used in this stability assay (i.e. 20°C). This clearly indicates that increasing the temperature- and time-dependent stability of the BLT1 receptor also increased its tolerance to different detergents.

Table I.

Detergent-Dependent Stability of BLT1 and BLT1His

| fos16 | fos12 | DDM | LDAO | DM | NG | OG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLT1 | 100 | 42 | 100 | 92 | 50 | — | — |

| BLT1His + Zn2+ | 100 | 96 | 100 | 98 | 95 | 89 | 73 |

Amount of ligand-competent receptor (expressed in % of total receptor) when BLT1 and BLT1His (in the presence of 1 mM Zn2+) were reconstituted in different detergents (fos16, fos-choline-16; fos12, fos-choline-12; DDM, dodecylmaltoside; DM, decylmaltoside; LDAO, lauryldimethylamine oxide; NG, nonylglucoside; OG, octylglucoside). Assays were all carried out at 20°C.

Discussion

Molecular analyses of GPCRs involve overcoming several technical barriers, among them the stabilization of the native fold out of a membrane environment. Improving the stability of a purified receptor implies stabilizing it in essentially one conformation, preferentially that of the ground state that is considered as the most stable one. For GPCRs, it is assumed that the helical movements that occur on activation result in a looser and less stable packing in the protein, and therefore in a reduced stability in detergent solutions.16

It has been shown with different G protein-coupled receptors, for example, rhodopsin,33 the M1 muscarinic receptor,34 or the β2-adrenergic and PTH receptors19 that introducing histidine residues at specific positions in the cytoplasmic end of helices 3 and 6 results in a metal binding site connecting both transmembrane segments; introducing such a metal ion binding site restrains the relative movements of these helices that occur on agonist-induced activation. We adopted here a similar approach to stabilize the ground state of the purified recombinant BLT1 receptor.

The residues at the cytoplasmic end of TM3 and TM6 to be mutated were selected on the basis of a three-dimensional homology model of BLT1 based on rhodopsin structure. As shown in Figure 1(A), the residues mutated here are closely related to those mutated in the β2-adrenergic receptor, rhodopsin or the PTH receptor.19 We selected the structure of the ground state of rhodopsin as a template for our three-dimensional model since the BLT1 conformation to stabilize was that of the ground state, as is that of rhodopsin in this crystal structure. Moreover, BLT1 is closer to rhodopsin in terms of both sequence and structural organization. Similar rhodopsin-based BLT1 models have been previously published and validated through site-directed mutagenesis.29–31,35 Our rhodopsin-based model of BLT1 has also been experimentally validated through a combination of site-directed mutagenesis and photolabeling experiments (JLB, ML, and JP, manuscript in preparation). Finally, the fact that the residues selected on the basis of this model are indeed properly located to coordinate the divalent cation further validates our three-dimensional model for the ground state of BLT1.

The mutant BLT1His receptor was expressed, purified and refolded in similar conditions than the wild-type one. Moreover, we observed an invariance between the ligand binding properties of BLT1His in the absence of Zn2+ and those of the wild-type receptor. The ligand binding properties of the receptor were assessed here by measuring the changes in the dichroic properties of LTB4 induced by the binding to BLT1. Free LTB4 is characterized by a four-band CD spectrum in the 240–290 nm region. As we previously reported,22 binding to the recombinant receptor results in an increase in the intensity of all LTB4 dichroic bands that can be interpreted as a skewing of the time-averaged planar triene in free LTB4. The changes in the CD properties associated with the triene moiety of LTB4 are therefore very sensitive to subtle changes in the torsional features of this triene. The similarity in the intensity of the LTB4-associated CD bands obtained with BLT1 and BLT1His (in the absence of Zn2+) is thus direct evidence for a structural invariance of LTB4 bound to both receptors. These observations, associated with the invariance in the CD (far- and near-UV regions) and Trp-fluorescence spectra of the two receptors (data not shown), strongly suggest that the mutations do not affect the overall fold of the BLT1 receptor.

The modified BLT1 receptor in the presence of Zn2+ bound its LTB4 agonist with a significantly decreased affinity. Moreover, in the presence of Zn2+, BLT1His was no longer able to trigger G protein activation. All these data suggest that introducing a metal-ion binding site between TM3 and TM6 locks BLT1 in its ground state, in agreement with previous models for GPCR activation (Ref. 18 and references therein).

Stabilizing membrane proteins in solution can be required to assess their structure, as recently illustrated in the case of the β1-adrenergic receptor.6,16 The data reported here clearly establish that creating a cation-binding site connecting TM3 and TM6 stabilizes BLT1 in its ground state conformation; this leads to an increase in its thermostability in detergent solutions, with a shift in the apparent Tm of about 10°C. Moreover, the modified receptor appears to be stable in a variety of detergents, in contrast to the wild-type receptor. Such a conformational stabilization could be of importance in the context of the crystallization of this pharmacologically important receptor. Finally, the interesting feature with this mutant is that the same receptor protein can be readily turned from its inactive to its native conformation simply by chelating the divalent cation, with not other modification of the protein. All these features make the BLT1His protein particularly well suited for crystallization and subsequent structure determination.

Methods

Materials

LTB4 was purchased from BIOMOL laboratories. All detergents were from Anatrace; thrombin and TPEN were from Sigma.

Computational methods

A full account of this simulated 3D-model will be presented elsewhere including a possible interaction of LTB4 with BLT1 within the ligand-binding pocket (JLB, ML, and JP, manuscript in preparation). Briefly, calculations were performed on an SGI Octane workstation using Macromodel version 6.5 (Columbia University, New-York)36 or Insight II and Discover version 2000 (Accelrys Inc.). The homology building procedure was performed within the Homology module of Insight II. Alignment of sequences was performed using the Homology multiple-sequence aligner software via the PAM (120 or 250) matrices or the Clustal W software as implemented within Homology module. The starting template structure was the bovine rhodopsin X-ray structure (PDB code 1U19; Ref. 37). The coordinates for non-homologous loops were extracted from a data-base generated (via an Insight II utility) from α-carbon distances matrix arising from a 250 proteins set. The crude model was refined by several cycles of splice repairs on the loops and relaxation on the SCR's sides using 100 steps of Steepest Descent and 500 cycles of conjugate gradient. Then small 5 ps molecular dynamics runs were performed on each loop to relax the strains. Finally the entire backbone was fixed and the whole side chains were fully minimized with conjugate gradient method until a RMS of 0.1 kcal Å−1 mol−1 was reached. At this stage the disulfide bond was built. The minimization process was then resumed with the helices backbone fixed but with a tethering constraint applied on the backbone of all loops. This constraint was slowly lowered (starting with a 200 kcal Å−1 mol−1 force constant) in a stepwise manner. Then the helices backbone was unfixed and a tethering constraint was applied on them and the same stepwise minimization process was resumed until the RMS is below 0.1 kcal Å−1 mol−1 and the tethering force is 10 kcal Å−1 mol−1.

Site-directed mutagenesis and protein production

All mutations were introduced in the wild-type BLT1 receptor by PCR-mediated mutagenesis using the QuickChange multisite-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and the wild-type BLT1 construct32 as a template. Mutations were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing. The unfolded wild-type receptor and the different mutants were then expressed in Rosetta(DE3) E. coli strain inclusion bodies and refolded in fos-choline-16/asolectin mixed micelles in a buffer 12.5 mM Na-borate, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.8 as described in Damian et al.13

Ligand- and cation-binding measurements

Fluorescence-based Zn2+-binding experiments were carried out using the Zn2+-binding chromophore mag-fura-2 as described by Eren et al.26 Protein concentrations were in the 10−7M range. All protein concentrations were calculated from UV-absorptivity values (Cary 400 spectrophotometer, Varian) using the extinction coefficient calculated by the method of Gill and von Hippel.38 Fluorescence measurements were carried out with a Cary Eclipse fluorimeter (Varian). Buffer contributions were subtracted under the same experimental conditions. Circular dichroism (CD)-monitored LTB4 titration experiments were carried out as previously described.13 The spectra were the average of five scans using a bandwidth of 2 nm, a step-width of 0.2 nm and a 0.5 s averaging time per point. The cell path length was 1.00 ± 0.01 mm. BLT1 concentrations were determined by UV absorption. A molar absorptivity of 5.0 × 104 L mol−1 cm−1 at 270.5 nm39 was adopted for LTB4 without any correction for solvent effects. All titration data were analyzed using the PRISM software version 4.0 (Graphpad Inc.).

G protein activation assays

GTPγS binding assays were carried out as described by Oldham et al.40 Briefly, the basal rate of GTPγS binding was determined by monitoring the increase in the intrinsic fluorescence (λex = 295 nm; λem = 345 nm) of Gα (500 nM) reconstituted with Gβ1γ2 (500 nM) in buffer containing 10 mM MOPS (pH 7.2), 130 mM NaCl, and 2 mM MgCl2 for 20 min at 20°C after the addition of 10 mM GTPγS. Measurements were carried out in the absence or presence of 100 nM BLT1. The data were normalized to the baseline (0%) and the fluorescence maximum (100%). Data represent the averages from three experiments. The assays in the presence of TPEN were carried out by incubating the BLT1His protein first in the presence of 1 mM ZnCl2 for 30 min and then in the presence 1 mM TPEN for additional 30 min before measuring agonist-induced GTPγS binding. The Gαi2βγ proteins were produced as previously described.27

Thermostability and time-dependent stability assays

Thermostability was assayed by incubating different receptor samples at the specified temperature for 30 min. The samples were then placed on ice. The amount of active receptor was then determined by circular dichroism by recording the intensity of LTB4-associated CD band centered at 270.5 nm and normalizing to the intensity obtained for the initial receptor preparation before any heating. The intensity of this band is directly related to the amount of LTB4 bound to the receptor.22 For the time-dependent stability, the intensity of LTB4-associated CD band at 270.5 nm in the presence of BLT1 was recorded after storage at 4°C for the duration indicated and normalized to the intensity obtained for the initial receptor preparation. For the detergent-dependent stability, the receptor was refolded in fos-choline-16/asolectin mixed micelles as described above, bound to Ni-NTA superflow (Qiagen), and then extensively washed with the same buffer where fos-choline-16 was replaced by either fos-choline-12 (fos12), DDM, DM, LDAO, NG, or OG. The detergents were used at a 1.5 times their cmc value. After elution from the column with the same buffer containing 200 mM imidazole, the protein was dialyzed overnight in a buffer 25 mM Na-phosphate, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.0 containing the corresponding detergent/asolectin mixture. The amount of active receptor was determined by measuring the intensity of the LTB4-associated CD band at 270.5 nm in the presence of BLT1 after 30 min incubation at 20°C.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CD

circular dichroism

- cmc

critical micelle concentration

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- LTB4

leukotriene B4

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

- SCR

structurally conserved regions

- TM

transmembrane

- TPEN

(N,N,N′,N′-Tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl) ethylenediamine).

References

- 1.Bockaert J, Claeysen S, Becamel C, Pinloche S, Dumuis A. G protein-coupled receptors: dominant players in cell-cell communication. Int Rev Cytol. 2002;212:63–132. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(01)12004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palczewski K, Kumasaka T, Hori T, Behnke CA, Motoshima H, Fox BA, Le Trong I, Teller DC, Okada T, Stenkamp RE, Yamamoto M, Miyano M. Crystal structure of rhodopsa G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2000;289:739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li J, Edwards PC, Burghammer M, Villa C, Schertler GF. Structure of bovine rhodopsin in a trigonal crystal form. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:1409–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheresov V, Rosenbaum DM, Hanson MA, Rasmussen SG, Thian FS, Kobilka TS, Choi HJ, Kuhn P, Weis WI, Kobilka BK, Stevens RC. High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human β2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2007;318:1258–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.1150577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rasmussen SG, Choi HJ, Rosenbaum DM, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Edwards PC, Burghammer M, Ratnala VR, Sanishvili R, Fischetti RF, Schertler GF, Weis WI, Kobilka BK. Crystal structure of the human β2-adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2007;450:383–387. doi: 10.1038/nature06325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warne T, Serrano-Vega MJ, Baker JG, Moukhametzianov R, Edwards PC, Henderson R, Leslie AG, Tate CG, Schertler GF. Structure of a β1-adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2008;454:486–491. doi: 10.1038/nature07101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park JH, Scheerer P, Hofmann KP, Choe HW, Ernst OP. Crystal structure of the ligand-free G-protein-coupled receptor opsin. Nature. 2008;454:183–187. doi: 10.1038/nature07063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murakami M, Kouyama T. Crystal structure of squid rhodopsin. Nature. 2008;453:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature06925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaakola VP, Griffith MT, Hanson MA, Cherezov V, Chien EY, Lane JR, Ijzerman AP, Stevens RC. The 2.6Å crystal structure of a human A2A adenosine receptor bound to an antagonist. Science. 2008;322:1211–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.1164772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobilka B, Schertler GF. New G-protein-coupled receptor crystal structures: insights and limitations. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popot JL, Berry EA, Charvolin D, Creuzenet C, Ebel C, Engelman DM, Flötenmayer M, Giusti F, Gohon Y, Hong Q, Lakey JH, Leonard K, Shuman HA, Timmins P, Warschawski DE, Zito F, Zoonens M, Pucci B, Tribet C. Amphipols: polymeric surfactants for membrane biology research. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:1559–1574. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3169-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breyton C, Chabaud E, Chaudier Y, Pucci B, Popot JL. Hemifluorinated surfactants: a non-dissociating environment for handling membrane proteins in aqueous solutions? FEBS Lett. 2004;564:312–318. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damian M, Perino S, Polidori A, Martin A, Serre L, Pucci B, Banères JL. New tensio-active molecules stabilize a human G protein-coupled receptor in solution. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1944–1950. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKibbin C, Farmer NA, Jeans C, Reeves PJ, Khorana HG, Wallace BA, Edwards PC, Villa C, Booth PJ. Opsin stability and folding: modulation by phospholipid bicelles. J Mol Biol. 2007;374:1319–1332. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Standfuss J, Xie G, Edwards PC, Burghammer M, Oprian DD, Schertler GF. Crystal structure of a thermally stable rhodopsin mutant. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serrano-Vega MJ, Magnani F, Shibata Y, Tate CG. Conformational thermostabilization of the β1-adrenergic receptor in a detergent-resistant form. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:877–882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711253105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magnani F, Shibata Y, Serrano-Vega MJ, Tate CG. Co-evolving stability and conformational homogeneity of the human adenosine A2a receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10744–10749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804396105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deupi X, Kobilka B. Activation of G protein-coupled receptors. Adv Protein Chem. 2007;74:137–166. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(07)74004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheikh SP, Vilardarga JP, Baranski TJ, Lichtarge O, Iiri T, Meng EC, Nissenson RA, Bourne HR. Similar structures and shared switch mechanisms of the β2-adrenoceptor and the parathyroid hormone receptor. Zn(II) bridges between helices III and VI block activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17033–17041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.17033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toda A, Yokomizo T, Shimizu T. Leukotriene B4 receptors. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002;68:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yokomizo T, Izumi T, Shimizu T. Leukotriene B4: metabolism and signal transduction. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;385:231–241. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banères JL, Martin A, Hullot P, Girard JP, Rossi JC, Parello J. Structure-based analysis of GPCR function: conformational adaptation of both agonist and receptor upon leukotriene B4 binding to recombinant BLT1. J Mol Biol. 2003;329:801–814. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00438-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higaki JN, Fletterick RJ, Craik CS. Engineered metalloregulation in enzymes. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17:100–104. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:27–28. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eren E, Kennedy DC, Maroney MJ, Arguello JM. A novel regulatory metal binding domain is present in the C terminus of Arabidopsis Zn2+-ATPase HMA2. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33881–33891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banères JL, Parello J. Structure-based analysis of GPCR function: evidence for a novel pentameric assembly between the dimeric leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 and the G-protein. J Mol Biol. 2003;329:815–829. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masuda K, Itoh H, Sakihama T, Akiyama C, Takahashi K, Fukuda R, Yokomizo T, Shimizu T, Kodama T, Hamakubo T. A combinatorial G protein-coupled receptor reconstitution system on budded baculovirus. Evidence for Gαi and Gαo coupling to a human leukotriene B4 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24552–24562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302801200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaudreau R, Beaulieu ME, Chen Z, Le Gouill C, Lavigne P, Stankova J, Rola-Pleszczynski M. Structural determinants regulating expression of the high affinity leukotriene B4 receptor: involvement of dileucine motifs and alpha-helix VIII. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10338–10345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuniyeda K, Okuno T, Terawaki K, Miyano M, Yokomizo T, Shimizu T. Identification of the intracellular region of the leukotriene B4 receptor type 1 that is specifically involved in Gi activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3998–4006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basu S, Jala VR, Mathis S, Rajagopal ST, Del Prete A, Maturu P, Trent JO, Haribabu B. Critical role for polar residues in coupling leukotriene B4 binding to signal transduction in BLT1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10005–10017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Damian M, Martin A, Mesnier D, Pin JP, Banères JL. Asymmetric conformational changes in a GPCR dimer controlled by G-proteins. EMBO J. 2006;25:5693–5702. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheikh SP, Zvyaga TA, Lichtarge O, Sakmar TP, Bourne HR. Rhodopsin activation blocked by metal-ion-binding sites linking transmembrane helices C and F. Nature. 1996;383:347–350. doi: 10.1038/383347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu ZL, Hulme EC. A network of conserved intramolecular contacts defines the off-state of the transmembrane switch mechanism in a seven-transmembrane receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5682–5686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sabirsh A, Bywater RP, Bristulf J, Owman C, Haeggstrom JZ. Residues from transmembrane helices 3 and 5 participate in leukotriene B4 binding to BLT1. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5733–5744. doi: 10.1021/bi060076t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohamadi F, Richards NGJ, Guida WC, Liskamp R, Lipton M, Caufield C, Chang G, Hendrickson T, Still WC. Macromodel—an integrated software system for modeling organic and bioorganic molecules using molecular mechanics. J Comp Chem. 1990;11:440–467. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okada T. X-ray crystallographic studies for ligand-protein interaction changes in rhodopsin. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:738–741. doi: 10.1042/BST0320738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gill SC, von Hippel PH. Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal Biochem. 1989;182:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Radmark O, Malmsten C, Samuelsson B, Clark DA, Goto G, Marfat A, Corey EJ. Leukotriene A: stereochemistry and enzymatic conversion to leukotriene B. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;92:954–961. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)90795-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oldham WM, Van Eps N, Preininger AM, Hubbell WL, Hamm HE. Mechanism of the receptor-catalyzed activation of heterotrimeric G proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:772–777. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]