Abstract

Insomnia-pharmacology clinical trials routinely exclude primary sleep disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD), with a single night of polysomnography (PSG). Given the expense of PSG, we examined whether a thorough clinical screening, combined with actigraphy, would successfully identify OSA and PLMD as part of baseline screening for a clinical trial of insomnia treatment in depressed patients. Of the 73 patients with a complete baseline dataset, 12 screened positive for OSA/PLMD (AHI > 15, or PLMAI > 15), while 61 “passed” the PSG screen. The OSA/PLMD+ patients were older (51.4 ± 10.2 y) and took more naps (2.6 per week) than the OSA/PLMD− patients (41.3 ± 12.8 y; and 1.1 naps per week). The combination of age and nap frequency produced a “good” receiver operating characteristic (ROC) model for predicting OSA/PLMD+, with the area under the curve of 0.82. There were no other demographic, sleep diary, or actigraphic variables, which differed between OSA/PLM + or −, and no other variable improved the ROC model. Still, the best model misclassified 16 of 73 persons. We conclude that while age and the presence of napping were helpful in identifying OSA and PLM in a well-screened sample of depressed insomniacs, PSG is required to definitively identify and exclude primary sleep disorders in insomnia clinical trials.

Citation:

McCall WV; Kimball J; Lasater B; D'Agostino RB; Rosenquist PB. Prevalence and prediction of primary sleep disorders in a clinical trial of depressed patients with insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5(5):454-458.

Modern clinical trials of chronic insomnia must clearly define their recruitment samples, typically excluding persons with primary sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD). Some insomnia and pharmacology clinical trials use a single night of polysomnography (PSG) with respiratory and leg EMG to exclude OSA and PLMD,1,2 while other insomnia clinical trials do not.3,4 PSG may be omitted as part of the OSA and PLMD exclusion process because of the expense associated with PSG, but the omission of PSG screening may lead to unacceptably high rates of OSA and PLMD, since ≥ 30% of older insomniacs have unsuspected OSA or PLMD in non-clinical trial samples.5 An alternative to PSG screening might include simple, lower-cost technologies such as measures of heart rate variability,6 wrist actigraphy combined with arterial tonometry,7 or actigraphy on the legs.8,9

While predictors of primary sleep disorders have previously been described in routine clinical samples, predictors of primary sleep disorders in the context of insomnia clinical trials have not. We examined whether a thorough clinical screening, combined with actigraphy, would successfully identify OSA and PLMD as part of baseline screening for a clinical trial of insomnia treatment in depressed patients. These recruits were screened with a sleep history and a physical exam before undergoing a week of prospective sleep-wake diary collection and actigraphy, culminating in one night of PSG. In the present report we describe an exploratory analysis of clinical and actigraphic predictors of OSA/PLMD. The main results of the clinical trial will be presented in a later report.

METHODS

The recruitment strategy was designed to be inclusive of all degrees of insomnia severity while excluding OSA and PLMD. The majority of participants were recruited through their response to newspaper advertisements, and underwent a telephone screen that confirmed age 18–70 years of age, and either (a) sleep latency > 30 minutes and sleep efficiency < 85% at least 4 nights per week, or (b) met Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) insomnia criteria for at least 4 nights per week.10 The phone screen further confirmed a likely diagnosis of major depression as per a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9) score of ≥ 10,11 a body mass index (BMI) ≤ 35, an absence of habitual snoring or daytime sleepiness, absence of significant restless leg symptoms as defined by < 4 of the 4 IRLS criteria,12 absence of caffeine, alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drug abuse, adherence to conventional bedtime hours, and absence of active medical illnesses likely to interfere with sleep. The project was approved by the local IRB, and all participants provided written, informed consent.

Five hundred and eighteen persons completed the telephone screen; 165 of these passed the telephone screen and were invited for further face-to-face screening after assuring > 7 days of abstinence from all psychoactive medications, except for fluoxetine which required 4 weeks of abstinence. Ninety-seven gave informed consent at the first face-to-face screening. At this visit we reconfirmed all telephone screening criteria, and made a DSM-IV diagnosis of unipolar major depression per Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID).13 We also confirmed Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) score > 24,14 and the 21-item Hamilton rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) score ≥ 20.15 The participant completed the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)16 and underwent a sleep history and physical exam with a physician. The sleep history focused on identifying symptoms of sleep apnea and restless legs syndrome.

Ninety-seven of these participants were then invited to a final phase of screening which included one week of prospective sleep diary collection of bedtime, sleep latency (SL), number of awakenings, wake after sleep onset (WASO), total sleep time (TST), rising time, and number and duration of daytime naps. Participants also wore an actigraph on the non-dominant wrist 24-h per day for one week of prospective screening. Actigraphy was conducted with the Mini Mitter Actiwatch set at 30-sec epochs. The actigraphic data were analyzed 3 different ways–using the low, medium, and high sensitivity settings. Weekly averages of sleep variables were computed from actigraphy software algorithms, including SL, WASO, TST, sleep efficiency (SE), sleep fragmentation, as well as average daytime activity counts, maximum activity count, and time spent “immobile” during the day.

Patients remained free of all psychoactive medications for this week, and at the end of this week underwent one night of 8-h PSG. Thus, patients were free of psychotropic medications for a minimum of 2 weeks by the time of PSG. Seventeen patients did not proceed from consent to PSG, including 8 who were lost to follow-up, and 9 who asked to dropout. Thus 80 participants proceeded to PSG screening. The PSG was started at their median bedtime as established from the prospective diary collection. The PSG montage included 4 channels of EEG (C3-A2, C4-A1, C3-O1, and C4-O2), left and right EOG, chin EMG, EKG, right and left anterior tibialis EMG, nasal thermistor, oral thermistor, and pulse oximetry. Sleep was scored by one of the authors (WVM), according to standard criteria,17 and blind to participant identity. Latency to persistent sleep (LPS) was defined as the time from light out to the first epoch of 10 consecutive minutes of uninterrupted sleep. REM latency was defined as the time from LPS to the first epoch of REM sleep, minus intervening wake time.

Clinically significant sleep apnea was defined as an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) ≥ 15 cumulative apneas and hypopneas per hour of EEG sleep. An apnea was defined as ≥ 90% reduction in thermistor-determined airflow for ≥ 10 sec. A hypopnea was defined as 50% to 90% reduction in airflow for ≥ 10 sec, accompanied by an EEG arousal or arterial desaturation of ≥ 4%. Clinically significant PLM disorder was defined by a PLM-arousal index (PLMAI) of ≥ 15 PLM-related EEG arousals per hour of sleep.

Statistics

The primary aim of this exploratory study was to model predictors of significant OSA and PLMD, which were defined respectively defined as an AHI ≥ 15, and PLMAI ≥ 15. Statistical analyses were conducted with JMP 7.0.1. Twelve persons had either OSA or PLMD; and these 12 persons were pooled together to make the OSA/PLMD+ group. Although OSA and PLMD are clinically and etiologically distinct sleep disorders, for the purposes of insomnia-pharmacology clinical trials they are both excluded because of similar disturbing effects on sleep microarchitecture (i.e., arousals). Descriptive statistics were calculated for the PSG characteristics of those with and without OSA/PLMD, and statistical comparisons of the PSG variables for the 2 groups were made with one-way ANOVA.

Candidate predictor variables for OSA/PLMD were included in a logistic regression model, with subsequent examination of ROC curves. Age, gender, and BMI were the first candidate variables tested as predictors of OSA/PLMD. Of these 3 variables, only those that made a significant (p < 0.05) contribution were retained in subsequent model development. Next, clinical variables were tested one at a time in the model, including daytime and night time diary variables, ISI, and HRSD. Again, only significant clinical variables were retained and added to the prior demographic variables. Finally, actigraphic variables were tested within the model, one at a time. After the best model was defined, the best cut point for each of the retained predictor variables was calculated by modeling univariate ROC curves and defining the value for each predictor variable that optimized the greatest [sensitivity – (1-specificity)]. Means were calculated and compared for demographic and clinical variables of the participants with OSA/PLMD and those without OSA/PLMD, using 2-sided t-tests. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 80 participants who completed the PSG screen, 73 had complete demographic, clinical, and actigraphic data. Of these, 12 persons (16%) had a primary sleep disorder: 5 had AHI ≥ 15 (AHI = 28.4 ± 22.3; PLMAI = 3.9 ± 5.6), 6 had PLMAI ≥ 15 (AHI = 0.5 ± 1.0; PLMAI = 31.7 ± 20.7), and 1 person had both AHI and PLMAI ≥ 15 (AHI = 29.3; PLMAI = 35.7). The 61 persons who “passed” the PSG screening had no clinically significant sleep apnea or PLM (AHI = 1.8 ± 3.6; PLMAI = 1.2 ± 2.4)

The overall sample was middle-aged, primarily female, and modestly overweight (Table 1). Depression and insomnia symptoms were in the moderate-severe range, as reflected in HRSD and ISI scores, and in diary measurements of SL, WASO, and TST. PSG showed that TST and SE were low in both the OSA/PLMD+ and OSA/PLMD− groups, as would be expected in a sample of insomniac patients. PSG sleep onset, sleep continuity, and sleep stage variables were similar in those with and those without OSA/PLMD, except for less slow wave sleep and more frequent arousals in the OSA/PLMD+ group (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic, Clinical, and Sleep Diary Data

| OSA/PLMD+ N = 12 | OSA/PLMD− N = 61 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 51.4 ± 10.2 | 41.3 ± 12.8 | 42.9 ± 12.9 |

| Gender (%women) | 50.0 | 68.9 | 65.8 |

| BMI | 28.6 ± 6.0 | 27.6 ± 5.2 | 27.8 ± 5.3 |

| ISI | 20.4 ± 4.6 | 20.0 ± 4.4 | 20.0 ± 4.4 |

| HRSD | 22.5 ± 4.3 | 22.8 ± 4.1 | 22.7 ± 4.1 |

| Self-report sleep latency (min) | 73.2 ± 63.8 | 68.1 ± 40.9 | 69.0 ± 45.0 |

| Self-report # awakenings | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 2.0 ± 1.3 | 2.0 ± 1.3 |

| Self-report wake after sleep onset (min) | 87.4 ± 76.7 | 62.0 ± 56.0 | 66.2 ± 60.0 |

| Self-report total sleep time | 321.1 ± 71.4 | 351.3 ± 63.4 | 346.3 ± 65.3 |

| Self-report number of naps per day* | 0.37 ± 0.43 | 0.16 ± 0.21 | 0.19 ± 0.27 |

| Self-report cumulative nap time per week (min)* | 23.0 ± 30.1 | 11.2 ± 18.9 | 13.1 ± 21.4 |

OSA/PLMD+ is different from OSA/PLMD− at p < 0.05

Table 2.

Polysomnography Variables from an 8-Hour Recording

| OSA/PLMD+ N = 12 | OSA/PLMD− N = 61 | Total N = 73 | p-value for group differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latency to the first epoch of sleep (min) | 17.7 ± 18.0 | 31.5 ± 40.8 | 29.2 ± 38.3 | 0.25 |

| Latency to persistent sleep (min) | 35.1 ± 30.1 | 42.3 ± 55.9 | 41.4 ± 53.2 | 0.71 |

| Wake after sleep onset (min) | 69.7 ± 59.1 | 63.5 ± 53.6 | 64.3 ± 53.9 | 0.75 |

| Total sleep time (min) | 386.8 ± 73.3 | 378.4 ± 78.5 | 379.8 ± 77.2 | 0.74 |

| Sleep efficiency % | 79.9 ± 15.4 | 78.8 ± 16.3 | 78.9 ± 16.1 | 0.82 |

| REM latency (min) | 103.5 ± 62.2 | 84.4 ± 43.3 | 86.9 ± 46.0 | 0.25 |

| Stage 1% | 10.2 ± 6.6 | 10.5 ± 9.0 | 10.4 ± 8.6 | 0.93 |

| Stage 2% | 58.7 ± 14.6 | 52.3 ± 9.0 | 53.3 ± 10.3 | 0.04 |

| SWS% | 13.2 ± 7.5 | 17.8 ± 7.6 | 17.1 ± 7.7 | 0.05 |

| REM% | 17.8 ± 8.2 | 19.5 ± 7.3 | 19.3 ± 7.5 | 0.47 |

| Arousal index | 31.8 ± 21.0 | 8.7 ± 6.8 | 12.5 ± 13.5 | 0.0001 |

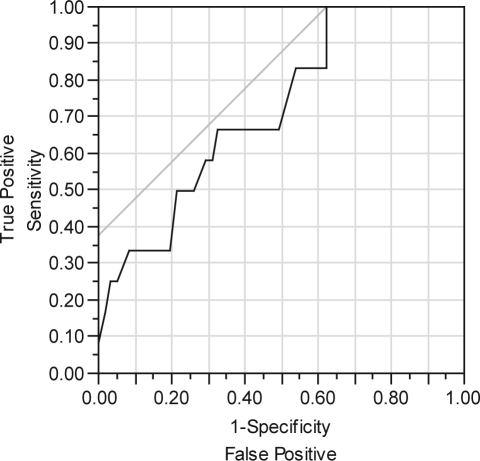

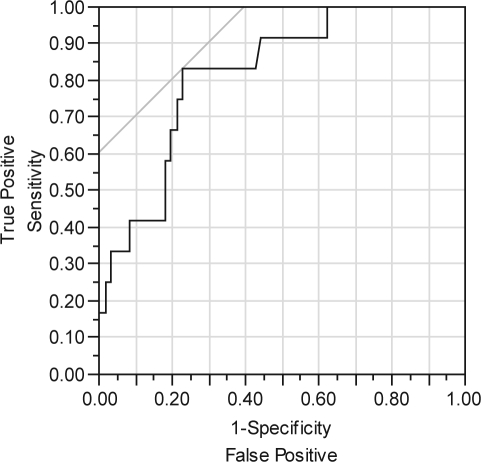

Logistic modeling of OSA/PLMD by age, gender, and BMI was significant only for age (χ2 = 6.9; df = 1; p < 0.01). The area under the curve (AUC) for the ROC curve was 0.72 for age, which is consistent with a “fair” performing model (Figure 1). The sequential testing of clinical variables, added to a model that already included age, showed that both the number of naps and the duration of naps were significant. The best model included both age and number of naps, with an ROC AUC of 0.82, indicating a “good” overall model (χ2 = 14.9; df= 2, p < 0.001) (Figure 2). Both age (p < 0.05) and number of naps (p < 0.01) contributed to this best model. When the best model was optimized for [sensitivity – (1-specificity)], it correctly identified 10 of 12 persons with OSA/PLMD, and it correctly identified 47 of 61 persons without OSA/PLM. Thus the best model still misclassified 16 of 73 persons. The best cut point for age was 37 years, and the best cut point for the average number of naps was 0.29 per day, equivalent to an average of 2 naps per week. Depressed insomniacs with OSA/PLMD were older and took more naps per week than those without OSA/PLMD (Table 1). There were no other differences between the groups in any demographic or clinical variable. No actigraphic variable, at any sensitivity setting, was significant in either univariate or multivariate logistic regression models as a predictor for OSA/PLMD (data not shown).

Figure 1.

ROC for age as a predictor of OSA/PLMD. Using PSG Fail = ‘1’ to be the positive level. Area Under Curve = 0.71790.

Figure 2.

ROC for age and nap frequency as predictors of OSA/PLMD. Using PSG Fail = ‘1’ to be the positive level. Area Under Curve = 0.81762.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study show that 16% of depressed insomniacs in this clinical trial had clinically significant OSA or PLMD, despite multiple levels of clinical screening prior to PSG that included BMI, a sleep history, a systematic assessment of RLS, and a physical exam. The limitations of a physician's exam in detecting primary sleep disorders have been previously described.18 To the extent that napping is an indicator of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), then our findings are consistent with prior reports that age and EDS are predictors of OSA/PLMD.19,20 The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) is a common and well-validated self report instrument for detecting EDS, and it was not used in this study; however, general questions about EDS were included in the initial telephone screen.21 The ESS measures a construct slightly different from our measurements of napping. The ESS is retrospective and hypothetical (i.e., likelihood of dozing at your desk in the afternoon), while our measurement of napping was based upon prospective, daily recording. A surprise finding is that relatively low levels of napping (about 2 naps per week) identified persons at higher risk for a primary sleep disorder.

This study has several limitations, including its small size and exploratory design. This study did not include adolescents, and included no persons over 66 years old. The categorization of the presence or absence of primary sleep disorders was based upon a single night of PSG, and the degree of primary sleep disorders has been reported to vary night-to-night.22,23 Therefore, it is possible that we may have misclassified our patients regarding the presence of primary sleep disorders. We chose to lump our OSA and PLMD patients together because there were insufficient numbers of either to consider them separately, and because their sleep disturbing effects on sleep microarchitecture may be similar. We recognize that larger samples might indicate different sets of predictors for OSA patients versus PLMD patients.

An earlier, preliminary examination of the data (which did not consider the prospective sleep diary data, including napping) had suggested that actigraphic variables might be predictive of primary sleep disorders,24 but this was not substantiated in the final sample. Actigraphy might have been of value in identifying the sleep fragmentation of primary sleep disorders in this sample had we used a different epoch length (i.e., 15-sec epochs). A recent report found that actigraphically determined sleep efficiency predicted OSA/PLMD in a community dwelling population study (i.e., non-patients),25 but actigraphy may be less robust in identifying OSA/PLMD in insomniacs.

In summary, we found that 16% of well-screened depressed insomniacs in a clinical trial had unsuspected primary sleep disorders. Age and low-frequency napping were risk factors for unsuspected primary sleep disorders. Still, even our best model miscategorized many of our patients, suggesting that PSG is necessary to confidently detect primary sleep disorders in insomnia clinical trials.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This study was supported in part by Sepracor Inc, and Mini Mitter. Dr. McCall is an advisor for Somaxon, GlaxoSmithKline, and Sepracor and has participated in speaking engagements for Sepracor. The other authors have indicated no other financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by NIMH MH70821-01, NIH GCRC M01-RR07122, Sepracor Inc, and Mini Mitter

REFERENCES

- 1.Walsh JK, Vogel GW, Scharf M, et al. A five week, polysomnographic assessment of zaleplon 10 mg for the treatment of primary insomnia. Sleep Med. 2000;1:41–9. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(99)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liguori A, Gatto C, Jarrett D, et al. Behavioral and subjective effects of marijuana following partial sleep deprivation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70:233–40. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perlis ML, McCall WV, Krystal A, et al. Long-term, non-nightly administration of zolpidem in the treatment of patients with primary insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1128–37. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scharf M, Erman M, Rosenberg R, et al. A 2-week efficacy and safety study of eszopiclone in elderly patients with primary insomnia. Sleep. 2005;28:720–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.6.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichstein K, Riedel B, Lester K, et al. Occult sleep apnea in a recruited sample of older adults with insomnia. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:405–10. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sforza E, Pichot V, Cervena K, et al. Cardiac variability and heart-rate increment as marker of sleep fragmentation in patients with a sleep disorder: a preliminary study. Sleep. 2007;30:43–51. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayas N, Pittman S, MacDonald M, et al. Assessment of a wrist-worn device in the detection of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2003;4:435–42. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sforza E, Johannes M, Claudio B. The PAM-RL ambulatory device for detection of periodic leg movements: a validation study. Sleep Med. 2005;6:407–13. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King M, Jaffre M, Morrish E, et al. The validation of a new actigraphy system for the measurement of periodic leg movements in sleep. Sleep Med. 2005;6:507–13. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edinger JD, Bonnet MH, Bootzin RR, et al. Derivation of research diagnostic criteria for insomnia: Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine work group. Sleep. 2004;27:1567–96. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen R, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et al. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology: A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101–19. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state. ” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. Los Angeles: UCLA Brain Information Service/Brain Research Institute; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haponik E, Smith P, Meyers D, et al. Evaluation of sleep-disordered breathing Is polysomnography necessary? Am J Med. 1984;77:671–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90361-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedman M, Tanyeri H, La Rosa M, et al. Clinical predictors of obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1901–7. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199912000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guilleminault C, Stoohs R, Clerk A, et al. From obstructive sleep apnea syndrome to upper airway resistance syndrome: consistency of daytime sleepiness. Sleep. 1992;15:S13–S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edinger JD, Marsh GR, McCall WV, et al. Sleep variability across consecutive nights of home monitoring in older mixed DIMS patients. Sleep. 1991;14:13–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edinger JD, McCall WV, Marsh GR, et al. Periodic limb movement variability in older DIMS patients across consecutive nights of home monitoring. Sleep. 1992;15:156–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCall WV, Kimball J, Boggs N, Lasater B, Rosenquist PB. Actigraphy as a component of screening for sleep apnea and periodic limb movements. Sleep. 2008;31:A336. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehra R, Stone K, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Interpreting wrist actigraphic indices of sleep in epidemiologic studies of the elderly: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Sleep. 2008;31:1569–76. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.11.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]