Abstract

Background

The development of noninvasive screening tests is important to reduce mortality from gastrointestinal neoplasia. We sought to develop such a test by analysis of DNA methylation from exfoliated cancer cells in feces.

Methods

We first analyzed methylation of the RASSF2 and SFRP2 gene promoters from 788 primary gastric and colorectal tissue specimens to determine whether methylation patterns could act as stage-dependent biomarkers of gastrointestinal tumorigenesis. Next, we developed a novel strategy that uses single-step modification of DNA with sodium bisulfite and fluorescence polymerase chain reaction methodology to measure aberrant methylation in fecal DNA. Methylation of the RASSF2 and SFRP2 promoters was analyzed in 296 fecal samples obtained from a variety of patients, including 21 with gastric tumors, 152 with colorectal tumors, and 10 with non-neoplastic or inflammatory lesions in the gastrointestinal lumen.

Results

Analysis of DNA from tissues showed presence of extensive methylation in both gene promoters exclusively in advanced gastric and colorectal tumors. The assay successfully identified one or more methylated markers in fecal DNA from 57.1% of patients with gastric cancer, 75.0% of patients with colorectal cancer, and 44.4% of patients with advanced colorectal adenomas, but only 10.6% of subjects without neoplastic or active diseases (difference, gastric cancer vs undiseased = 46.5%, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 24.6% to 68.4%, P < .001; difference, colorectal cancer vs undiseased = 64.4%, 95% CI = 53.5% to 75.2%, P < .001; difference, colorectal adenoma vs undiseased = 33.8%, 95% CI = 14.2% to 53.4%, P < .001).

Conclusions

Methylation of the RASSF2 and SFRP2 promoters in fecal DNA is associated with the presence of gastrointestinal tumors relative to non-neoplastic conditions. Our novel fecal DNA methylation assay provides a possible means to noninvasively screen not only for colorectal tumors but also for gastric tumors.

CONTEXT AND CAVEATS

Prior knowledge

A stool-based screening test for colorectal cancer has long been sought. Most recently, studies have centered on the analysis of biomarkers in DNA from exfoliated tumor cells.

Study design

The degree of DNA methylation at the RASSF2 and SFRP2 gene promoters was analyzed in 788 colorectal and gastric tumor specimens to establish these methylation patterns as stage-dependent biomarkers of gastrointestinal tumorigenesis. Next, a highly sensitive assay was developed for the detection of these methylation patterns among 296 fecal DNA specimens that included many from patients with colorectal or gastric tumors.

Contribution

Extensive methylation at the RASSF2 and SFRP2 promoters was much more likely to be found in advanced gastric and colorectal tumors than in normal tissue. Fecal DNA methylation and recovery were also much more likely in stool samples from diseased patients. One or more methylation markers was detected in fecal DNA from 57% of gastric cancer patients, 75% of colorectal cancer patients, and 44% of subjects with advanced colorectal adenomas, but only 10.6% of undiseased patients.

Implications

This method shows promise as a noninvasive screening tool not only for colorectal cancer but also for gastric cancer.

Limitations

The analysis of additional biomarkers may help to enhance the sensitivity of the assay, to reduce the detection of false positives, and to distinguish gastric from colorectal cancers.

From the Editors

A noninvasive test for colorectal cancer has long been sought to screen patients who are reluctant to undergo barium enemas and invasive tests such as colonoscopy (1). Fecal occult blood tests were the first successful screens for asymptomatic colorectal cancer and detected both advanced polyps and invasive cancers with high sensitivity (2–8). However, the efficacy of fecal occult blood test–based screening for colorectal cancer is limited because of the common occurrence of occult bleeding from non-neoplastic sources (1). Interest has shifted recently to the identification of tumor-specific changes in fecal DNA that are representative of the neoplastic cells that are shed into the intestinal lumen of patients with colorectal cancer (9–12).

Until now, many studies to purify and analyze DNA from exfoliated tumor cells in fecal matter investigated a multitarget panel that included several cancer-specific mutations and demonstrated that long human DNA fragments could be recovered from human feces (10,13–16). Others have analyzed hypermethylated promoter DNA sequences from exfoliated neoplastic cells in fecal matter as an alternative approach to identifying diagnostic markers (15,17–25).

Aberrant methylation of CpG islands in gene promoter regions is characteristic of a large majority of gastrointestinal tumors (26,27). The hypermethylation of cytosine residues in a wide range of gene promoters is known to result in their transcriptional inactivation and may provide a useful marker to accurately distinguish advanced tumors from early lesions (28). Although the detailed mechanisms underlying hypermethylation are still unclear, we recently described the gradual expansion of methylated CpG residues in the MGMT promoter in a normal–adenoma–carcinoma sequence (29). These data, however, suggested that aberrant methylation patterns within CpG sequences were not homogeneous and exclusively restricted to tumor cells (28,30). Limited evidence has suggested that similar alterations may also be present in a small proportion of normal tissues but at substantially lower frequencies (30–32). In view of these findings, it is critical to consider the possibility of high false-positive rates when developing noninvasive screening methodologies using epigenetic biomarkers (17–19).

One interesting feature of fecal specimens from persons with colorectal cancer is the increased ratio of exfoliated tumor colonocytes compared with normal epithelial colonocytes due to enhanced rates of epithelial proliferation, lower rates of apoptosis, and reduced cell–cell adhesion in neoplastic tissues as compared with nonmalignant ones (1,33–35). Similar phenomena are likely to exist in gastric cancers as well and, if so, will provide a sound basis for designing a fecal DNA–based assay for gastric cancer. In 2002, gastric cancer was ranked as the second most common cause of worldwide cancer-related deaths (36). However, to the best of our knowledge, even though a few studies have attempted noninvasive fecal DNA–based tests for colorectal cancer detection, none of the previous studies has used this approach for the detection of gastric cancer.

This study aimed to address and improve on some of the limitations of currently available fecal DNA tests, including 1) the development of the “High-sensitivity assay for bisulfite DNA” (Hi-SA) for the simultaneous extraction and bisulfite modification of fecal DNA, which is a novel single-step direct approach and 2) the identification of highly specific and sensitive epigenetic biomarkers not only for patients with sporadic colorectal cancer but also for patients with Lynch syndrome and gastric cancer. We chose to look at DNA methylation of both the RASSF2 and SFRP2 gene promoters as potential biomarkers because both promoters are frequently methylated in colon and gastric cancers (30,37,38).

Materials and Methods

Tissue Specimens

Tissue specimens from 243 colorectal cancers and 208 adjacent normal colorectal mucosa were obtained from patients with colorectal cancer who had undergone curative surgery at Okayama University Hospital, Okayama, Japan, and Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany, between 1994 and 2007. A total of 103 adenomatous polyps and colonic biopsy specimens from 36 subjects with no evidence of colorectal neoplasia at colonoscopy were obtained from participants who had been subjected to colonoscopy at Chikuba hospital and Okayama University Hospital, Okayama, Japan, from 2002 to 2007, as described previously (29,30). Samples from 99 gastric cancers and their adjacent normal gastric mucosa were obtained from gastric cancer patients who had undergone curative surgery at Okayama University Hospital, Japan, between 1998 and 2006. Colorectal and gastric cancers were divided into subsets according to microsatellite instability (MSI) and heredity status as described previously (30) and according to TNM staging (39). We also collected cancer tissue and corresponding normal mucosa samples from 43 colorectal cancer patients, who had undergone curative surgery at Okayama University Hospital between October 1, 2004, and March 31, 2006, and from whom fecal samples were also available, to compare DNA methylation profiles in fecal DNA and the cancer tissues. Ethical approval was obtained from the participating institutions, and we obtained informed consent in writing from all patients. All tissues from non-necrotic areas of the tumor and from normal mucosa were placed on ice immediately upon removal from the patient and then frozen at −80°C until DNA could be extracted from them.

Bisulfite Modification of DNA From Tissue Specimens

DNA from the 874 entire tissue specimens (including 43 colorectal cancers and their normal mucosa tissues for a tissue vs fecal DNA matching test) was extracted using the QIAmpDNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Extracted DNA (1 μg) was subsequently modified using the EZ DNA methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA), which contains sodium bisulfite.

Methylation Analysis of RASSF2 and SFRP2 in DNA From Tissue Specimens

The methylation status of two regions each from the RASSF2 and SFRP2 promoters in DNA from different tissue specimens was analyzed by Combined Bisulfite Restriction Analysis (COBRA) (40). In this technique, treatment of DNA with sodium bisulfite deaminates unmethylated cytosines to make them uracils but leaves 5-methylated cytosines intact. Following this step, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) replaces uracils with thymines and 5-methylcytosines with cytosines. As a result, PCR products from DNA that was originally methylated are susceptible to HhaI cleavage, but PCR products from DNA that was not originally methylated are not. COBRA was carried out using PCR in 30-μL reaction volumes that contained 15 μL of HotStarTaq Master Mix Kit (Qiagen) and were 0.4 μM for each primer. The specific forward (F) and reverse (R) primer sets and conditions used for each COBRA reaction are listed in Supplementary Table 1, available online. The PCR products were digested with the restriction enzyme HhaI (New England Biolabs Inc, Ipswich, MA) at 37°C overnight to quantify DNA methylation within each promoter region.

Bisulfite Sequencing of PCR Fragments From Tissue DNA

As a second method to determine DNA methylation, and to confirm whether the results of COBRA (or Hi-SA, to be explained below) were correct, PCR products from the RASSF2 and SFRP2 promoters were amplified by a different set of primers for bisulfite DNA cloning and sequencing (Supplementary Table 1, available online). The SFRP2 promoter and RASSF2 promoter regions were cloned from bisulfite-treated DNA into the pCR2.1TOPO vector using the TOPO-TA cloning system (Invitrogen Life Technologies Inc, Carlsbad, CA), followed by automated DNA sequencing from both the F and R primers using an ABI 3100-Avant DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Fecal Samples

We obtained 303 fecal samples from individuals who underwent both colonoscopy and gastroduodenal endoscopy at five hospitals (Sato, Konko, Katsuyama, Moritani, and Okayama Univesity Hospitals) in Okayama, Japan. The patients, who were suspected to have colorectal tumors, were enrolled between 2004 and 2007 in a study approved by the Ethical Committee of Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Okayama, Japan (Accession No. 37). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before enrollment in the study.

The patients collected the feces before any colonoscopic or surgical intervention and did not need to adhere to a special diet before collection of the samples. Patients were instructed to collect an aliquot of feces using a paper spoon and to store it in a hermetically sealed plastic container, able to be frozen at −80°C (ASIAKIZAI Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), that was supplied by the investigators. Specimens weighed approximately 500–2000 mg. The container with the sample was stored in a ziplock bag at 4°C or −25°C in a home refrigerator or freezer until the patient’s hospital visit within a day later. The patients were instructed to transport their fecal samples to the hospital on ice and the samples were stored in a −25°C freezer immediately upon receipt. Within a week, couriers transferred these samples on dry ice to the laboratory at Okayama University Hospital, where they were frozen at −80°C until subsequent laboratory analysis. Preliminary experiments indicated that the recovery of DNA from the fecal samples was not so much influenced by whether they were refrigerated or frozen, for up to a week, as by how much they were diluted upon DNA extraction.

Bisulfite Modification of Fecal DNA

Approximately 100 mg of feces was dissolved in 1 mL lysis buffer (500 mM Tris–HCl, 16 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaCl, pH 9.0). These lysates were incubated at 95°C for 10 minutes and centrifuged at 2320g for 5 minutes. The supernatants were diluted in lysis buffer and centrifuged as above. Five microliters of 12 N NaOH and 30 μg of glycogen were added to 195 μL of the pooled supernatants and, after denaturation for 10 minutes at 37°C, 17.5 μL of 10 mM hydroquinone (Sigma-Aldrich Co, St. Louis, MO), 7.5 μL of 12 N NaOH and 125 μL of 8.64 N sodium bisulfite (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) were added. The samples were vortexed and incubated at 95°C for 15 minutes, then at 75°C for 165 minutes. Modified DNA was purified using a Zymo-Spin IC column (Zymo Research) and eluted with 20 μL of RNase- and DNase-free water before PCR amplification by the Hi-SA method (see below).

To validate our technique, we simultaneously amplified the gene, ClpP, for the proteolytic subunit of the Escherichia coli ClpA-ClpP and ClpX-ClpP ATP-dependent serine proteases as an internal control for the bisulfite reaction. The ClpP sequence was chosen as a positive control because these bacteria are present at constant but low abundance in the gut, irrespective of the daily diet and disease status of the host (41). The specific primer set and PCR conditions used for the ClpP gene are listed in Supplementary Table 1, available online. The ClpP gene was stably recovered from fecal matter that was diluted as much as 20-fold after bisulfite treatment. By contrast, human DNA was easily recoverable from the bisulfite-treated fecal samples with a dilution comparable with the 1× samples shown in Supplementary Figure 1, A (available online). The bisulfite-mediated conversion of unmethylated cytosines to uracils within ClpP was confirmed by sequencing the PCR products (see Supplementary Figure 1, B, available online). Amplifying the ClpP locus served two important purposes: First, it allowed us to quantify the recovery of human genomic DNA from feces and second, it provided a measure of the completeness of the bisulfite modification. Hence, only bisulfite-treated fecal samples from which ClpP could be successfully amplified were subjected to further analysis of the DNA methylation status of the human gene promoters. Using this criterion, seven of the 303 fecal specimens were excluded from further analysis.

Analysis of Fecal DNA Methylation

The rationale for developing the fecal methylation assay was in part based on the fact that colonocytes are constantly shed into the intestinal lumen from neoplastic epithelium but not from healthy, normal colon; hence, analyzable human DNA is more likely to be recovered from patients with tumors than from patients without tumors (10,11,20,42). To increase the sensitivity with which methylated or unmethylated alleles from human DNA could be detected in feces, we established a new methylation assay, the Hi-SA. The new method included internal primers that were sensitive to methylation or the lack thereof within the amplicon, in addition to external primers like those used in COBRA that were not methylation-specific (see Supplementary Table 1, available online). It was very difficult to detect methylated DNA sequences using COBRA in fecal samples because of the low proportion of methylated alleles, so in principle, a nested PCR using an internal methylation–specific primer that could amplify the methylated allele selectively would be more sensitive. Because the internal-methylated and internal-unmethylated primers were overlapping the F or R PCR primer, the length of PCR products from the internal-methylated plus F (or R) primers was nearly the same as for products from F plus R primers. Therefore, to distinguish methylated alleles from unmethylated alleles by a difference in PCR product sizes, we used HhaI digestion at CpG recognition sites after PCR to specifically cleave the methylated allele, as in COBRA.

Hi-SA was carried out by using PCR in 30-μL reaction volumes containing 15 μL of HotStarTaq Master Mix (Qiagen), 0.4 μM gene-specific primers, and 0.2 μM nested internal-methylated or internal-unmethylated primers. Normal human colonic epithelial DNA, which was unmethylated at the target CpG sites, was always used as an unmethylated control. Methylated DNA controls were prepared by artificially treating unmethylated normal human genomic DNA with SssI methylase (New England Biolabs), which adds a methyl group at the 5′ position carbon in cytosines at CpG sites, and these controls were run in parallel with each assay. Distilled water was also used as a negative control to monitor for any PCR contamination.

We initially assessed the feasibility of Hi-SA by determining the methylation status of RASSF2 (see Supplementary Figure 2, A, available online). The inclusion of unmethylation- or methylation-specific internal primers increased the amplification rates in comparison to COBRA (see Supplementary Figure 2, B, available online). Although the relative sensitivity of Hi-SA vs COBRA varied for different loci, overall, Hi-SA was five times more sensitive than COBRA (see Supplementary Figure 2, C and D, available online).

To increase our throughput, and to reduce certain time-consuming steps of Hi-SA, we next labeled one primer for each amplified methylation marker with a fluorescent dye: that is, with 6-FAM, VIC, NED, and PET (all from Applied Biosystems) for RASSF2 region 1, RASSF2 region 2, SFRP2 region 1, and SFRP2 region 2, respectively (see Supplementary Table 1, available online). Fluorescence Hi-SA offered several advantages over conventional Hi-SA including reducing restriction enzyme cleavage time to within 10 minutes and allowing us to pool multiple PCR products (ie, those for each target sequence that had been amplified in different tubes) because each product was labeled with a unique fluorescent dye. After pooling 1 μL of each PCR product, the combined samples were digested with HhaI at 37°C for 10 minutes to detect methylated alleles that are cleaved by the enzyme and were loaded simultaneously onto an ABI 310R Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Signals from individual PCR products were distinguished by the unique fluorescent PCR signal from each PCR target in fecal DNA, and the data were analyzed using GeneMapper software version 4.0 (Applied Biosystems). Combining fluorescent Hi-SA with our novel bisulfite modification methodology allowed us to both assess the recovery of human DNA from feces and its methylation status within a few hours.

Bisulfite Sequencing of PCR Fragments From Fecal DNA

PCR products from both the ClpP and human genes from fecal DNA were sequenced after bisulfite modification to confirm the Hi-SA results. For the sequencing of human promoter regions, Hi-SA products before restriction digestion were used as templates. Methylated alleles were re-amplified using the internal methylation–specific and internal methylation–nonspecific primers from 12 samples that showed methylation for each gene and subsequently sequenced. Unmethylated alleles were re-amplified using the nonspecific primers from 12 samples that showed unmethylation for each gene. All sequencing products were purified using QIAquick PCR purification Kit (Qiagen) and sequenced on an ABI 3100-Avant Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Statistical Analysis

Each fecal sample was given a numerical score to reflect the number of recovered and methylated genes. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the recovery rates and the methylation scores for human genomic fecal DNA from patients in whom disease stage had been identified by both colonoscopy and esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted for potential cutoff values based on the number of markers displaying recovery (recovery score), the number of markers methylated (methylation score), and a combined methylation and recovery score (combination score) with respect to the sensitivity for fecal DNA from patients with advanced lesions (colorectal cancer, advanced colorectal adenomas, and gastric cancers). Similarly, the specificity was determined for nonadvanced lesions (colorectal nonadvanced adenomas, colorectal hyperplastic polyps, and subjects without neoplastic or active diseases) in asymptomatic cases. The area under curve was measured to compare the screening efficiency among recovery, methylation, and combination scores. The combination score (H) was based on parameter estimates obtained from multiple logistic regression; H = β1 × (methylation score) + β2 × (recovery score), where β1 denotes the parameter estimate for methylation score obtained from logistic regression and β2 denotes the recovery score. In this study, the parameter estimate for methylation score (β1) was 1.16 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.67 to 2.06, P < .001 by the Wald test) and that of recovery score (β2) was 0.35 (95% CI = 0.11 to 0.56, P = .0037 by the Wald test). The ROC curve for the combination score was checked by cross-validation, which gave identical results. A nonparametric approach was used for comparing the area under the ROC curves (43). Fisher exact test was used to examine an association between categorical variables. The conventional κ statistic was calculated to compare the degree of agreement between the methylation status of fecal DNA from colorectal cancer patients and the matched DNA from the cancer and between the methylation status of fecal DNA from patients and the matched normal epithelial DNA. All P values reported were calculated in two-sided tests and values less than .05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Relationship of Promoter DNA Methylation Patterns With Colorectal and Gastric Cancer Progression

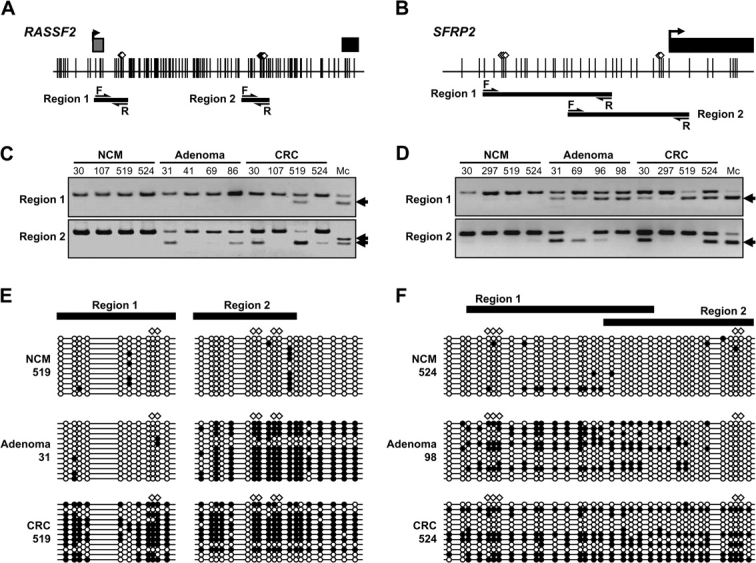

We investigated methylation patterns in CpG islands in each of two separate regions from the RASSF2 and SFRP2 gene promoters in DNA from 590 colorectal and 198 gastric specimens (regions 1 and 2) (Figure 1, A and B; see Figure 1, C and D, for representative data and Table 1 for characteristics and source of tissue). The selection of regions 1 and 2 in RASSF2 were based on previous results that showed that its 5′ CpG island spans approximately 1.6 kb and that expansion of methylation from region 2 to region 1 of this promoter contributed to gene silencing (44). By analogy, we divided the human SFRP2 promoter into the two regions. We chose region 1 based on sequence homology to the mouse sfrp2 promoter sequence that suggested that this region might be a binding site for the transcriptional factor pax2 (45). We chose region 2 based on previous studies in which we showed that this promoter region was aberrantly methylated at high frequency in colorectal cancer specimens (30). Bisulfite DNA cloning sequencing of the RASSF2 and SFRP2 promoter CpG sites including regions 1 and 2 revealed progressively more methylation with advancing colorectal cancer stage, as shown by a representative normal colonic mucosa specimen (mostly unmethylated), a colorectal adenoma specimen (partially methylated), and a colorectal cancer specimen (extensively methylated) (Figure 1, E and F).

Figure 1.

Analysis of RASSF2 and SFRP2 methylation in colorectal tissue. A–B) Schematic representation of RASSF2 A) and SFRP2 B) gene promoter regions analyzed by Combined Bisulfite Restriction Analysis (COBRA). Gray squares represent noncoding exon 1 regions; black squares represent coding exon 2 regions; arrows on the squares indicate transcriptional start sites. Vertical lines indicate CpG sites. White diamonds represent HhaI restriction enzyme recognition sequences. Thick horizontal lines depict the location of COBRA products. Arrows indicate forward (F) and reverse (R) primers that are nonmethylation-specific primers as described in Supplementary Table 1 (available online). C–D) Representative results of COBRA in the two regions (regions 1 and 2) of RASSF2 (C) and SFRP2 (D). Arrows indicate methylated alleles. “Mc” denotes methylated control. E–F) Cloning and sequencing of RASSF2 (E) and SFRP2 (F) regions 1 and 2. Thick horizontal lines show the region that was amplified by COBRA primers. Polymerase chain reaction products that were amplified by primer sets for bisulfite cloning sequence were cloned into a TOPO cloning vector and sequenced. For each sample, at least 12 clones were sequenced. Empty circles indicate unmethylated CpG sites. Filled circles represent methylated CpG sites. CRC = colorectal cancer; NCM = normal colonic mucosa.

Table 1.

Characteristics and RASSF2 and SFRP2 methylation status of colorectal and gastric tissue samples*

| Diagnosis | No. | Mean age, y (SD) | Men, No. (%) |

RASSF2 methylation status, No. (%) |

SFRP2 methylation status, No. (%) |

||||||

| Region 1 methylated | Region 2 methylated | Partially methylated† | Extensively methylated‡ | Region 1 methylated | Region 2 methylated | Partially methylated† | Extensively methylated‡ | ||||

| Colorectal normal mucosa | |||||||||||

| Total | 244 | 64.2 (11.8) | 154 (63.1) | 0 (0) | 11 (4.5) | 11 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 37 (15.2) | 11 (4.5) | 36 (14.8) | 6 (2.5) |

| Normal colonic mucosa from non-neoplastic colons | 36 | 64.0 (11.4) | 20 (55.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.3) | 1 (2.8) | 4 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Adjacent normal colonic mucosa | 208 | 64.2 (11.9) | 134 (64.4) | 0 (0) | 11 (5.3) | 11 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 34 (16.4) | 10 (4.8) | 32 (15.4) | 6 (2.9) |

| Colorectal adenomas | |||||||||||

| Total | 103 | 64.5 (11.0) | 76 (73.8) | 11 (10.7) | 33 (32.0) | 40 (38.8) | 2 (1.9) | 37 (35.9) | 13 (12.6) | 36 (35.0) | 7 (6.8) |

| Nonadvanced adenomas | |||||||||||

| Tubular adenomas <1 cm in diameter | 20 | 63.0 (10.0) | 18 (90.0) | 1 (5.0) | 5 (25.0) | 6 (30.0) | 0 (0) | 7 (35.0) | 1 (5.0) | 8 (40.0) | 0 (0) |

| Advanced adenomas | |||||||||||

| Overall | 83 | 64.9 (11.3) | 58 (69.9) | 10 (12.1) | 28 (33.7) | 34 (41.0) | 2 (2.4) | 30 (36.1) | 12 (14.5) | 28 (33.7) | 7 (8.4) |

| Tubular adenomas ≥1 cm in diameter | 54 | 64.7 (12.2) | 37 (68.5) | 6 (11.1) | 18 (33.3) | 22 (40.7) | 1 (1.9) | 20 (37.0) | 6 (11.1) | 18 (33.3) | 4 (7.4) |

| Tubulavillous adenomas | 15 | 67.4 (9.4) | 10 (66.7) | 2 (13.3) | 5 (33.3) | 7 (46.7) | 0 (0) | 6 (40.0) | 3 (20.0) | 7 (46.7) | 1 (6.7) |

| High-grade dysplasia | 14 | 63.2 (9.6) | 11 (78.6) | 2 (14.3) | 5 (35.7) | 5 (35.7) | 1 (7.1) | 4 (28.6) | 3 (21.4) | 3 (21.4) | 2 (14.3) |

| Colorectal cancer | |||||||||||

| Total | 243 | 62.8 (12.8) | 157 (64.6) | 56 (23.1) | 164 (67.5) | 112 (46.1) | 54 (22.2) | 199 (81.9) | 154 (63.4) | 65 (26.7) | 144 (59.3) |

| By MSI and heredity status | |||||||||||

| Lynch syndrome | 21 | 44.4 (10.7) | 17 (81.0) | 8 (38.1) | 13 (61.9) | 7 (33.3) | 7 (33.3) | 18 (85.7) | 16 (76.2) | 8 (38.1) | 13 (61.9) |

| Sporadic MSI-high | 15 | 68.9 (9.6) | 6 (40.0) | 9 (60.0) | 13 (86.7) | 4 (26.7) | 9 (60.0) | 15 (100) | 10 (66.7) | 5 (33.3) | 10 (66.7) |

| MSI-low and microsatellite-stable | 207 | 64.2 (11.6) | 134 (64.7) | 39 (18.8) | 138 (66.7) | 101 (48.8) | 38 (18.4) | 166 (80.2) | 128 (61.8) | 52 (25.1) | 121 (58.5) |

| By TNM stages§ | |||||||||||

| I and II | 93 | 64.3 (11.7) | 63 (67.7) | 15 (16.1) | 64 (68.8) | 49 (52.7) | 15 (16.1) | 81 (87.1) | 56 (60.2) | 31 (33.3) | 53 (57.0) |

| III and IV | 128 | 64.6 (11.7) | 77 (62.1) | 29 (22.7) | 86 (67.2) | 57 (44.5) | 29 (22.7) | 99 (77.3) | 80 (62.5) | 27 (21.1) | 76 (59.4) |

| Gastric normal mucosa | |||||||||||

| Adjacent normal gastric mucosa | 99 | 65.1 (11.7) | 65 (65.7) | 6 (6.1) | 0 (0) | 6 (6.1) | 0 (0) | 58 (58.6) | 15 (15.2) | 51 (51.5) | 11 (11.1) |

| Gastric cancer | |||||||||||

| Total | 99 | 65.1 (11.7) | 65 (65.7) | 16 (16.2) | 52 (52.5) | 36 (36.4) | 16 (16.2) | 95 (96.0) | 72 (72.7) | 25 (25.3) | 71 (71.7) |

| By MSI status | |||||||||||

| MSI-high | 13 | 69.6 (12.3) | 7 (53.9) | 7 (53.9) | 11 (84.6) | 4 (30.8) | 7 (53.9) | 13 (100) | 12 (92.3) | 1 (7.7) | 12 (92.3) |

| MSI-low and microsatellite-stable | 86 | 64.4 (11.5) | 58 (67.4) | 9 (10.5) | 41 (47.7) | 32 (37.2) | 9 (10.5) | 82 (95.4) | 59 (68.6) | 25 (29.1) | 58 (67.4) |

| By TNM status§ | |||||||||||

| I and II | 47 | 64.2 (12.4) | 31 (66.0) | 5 (10.6) | 24 (51.1) | 19 (40.4) | 5 (10.6) | 46 (97.9) | 33 (70.2) | 13 (27.7) | 33 (70.2) |

| III and IV | 52 | 65.9 (11.1) | 34 (65.4) | 11 (21.2) | 28 (53.9) | 17 (32.7) | 11 (21.2) | 49 (94.2) | 39 (75.0) | 12 (23.1) | 38 (73.1) |

MSI = microsatellite instability; TNM = TNM staging.

“Partially methylated” refers to the number of samples that were found to be methylated in region 1 or 2, but not both.

“Extensively methylated” refers to the number of samples that were found to be methylated in both regions 1 and 2 and includes a portion of the tallies shown under both “Region 1 Methylated” and “Region 2 Methylated”.

22 samples were missing information.

The characteristics of the 590 colorectal and 198 gastric tissue specimens are shown with their methylation status (Table 1). Overall RASSF2 methylation, that is, the frequency of partial methylation in RASSF2 (ie, affecting either region 1 or 2) and of extensive methylation in RASSF2 (ie, affecting both regions 1 and 2) was lowest in normal colorectal mucosa (4.5%), intermediate in colorectal adenomas (40.7%), and highest in colorectal tumors (68.3%). Although extensive RASSF2 methylation was observed in both adenomas and in colorectal cancers, this frequency was only 1.9% in adenomas compared with 22.2% in colorectal cancers. When colorectal cancer tissues were analyzed according to MSI and hereditary status, methylation of RASSF2 was extensive and frequent in sporadic MSI-high tumors (60.0%), lower in Lynch syndrome (33.3%), and lowest in MSI-low and microsatellite-stable cancers (18.4%).

SFRP2 methylation (partial or extensive) was observed in 17.3% of normal colorectal mucosa, 41.8% of colorectal adenomas, and 86.0% of colorectal cancer samples (Table 1). However, extensive SFRP2 methylation was observed in only 2.5% of normal tissues, 6.8% of adenomatous polyps, and 59.3% of cancers. Unlike RASSF2, analysis by MSI and hereditary status showed that extensive SFRP2 methylation was equally likely to occur in sporadic MSI-high tumors (66.7%), Lynch syndrome (61.9%), and MSI-low and microsatellite-stable cancers (58.5%).

When we classified colorectal adenomas into early and advanced adenomas and colorectal cancers by disease progression stage, extensive methylation in both genes was present in advanced colorectal cancers (TNM stage I/II and III/IV) but observed less often in normal colonic mucosa or colorectal adenomas (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 3, available online).

The pattern of DNA methylation was somewhat similar in gastric tissue specimens as in those from colon. RASSF2 methylation was more frequent in gastric carcinoma tissue (52.6%) compared with normal gastric mucosa (6.1%), and extensive methylation was observed exclusively in gastric carcinoma tissue (16.2% vs 0%). Similarly, extensive RASSF2 methylation was more frequent in MSI-high (53.9%) than MSI-low and microsatellite-stable (10.5%) gastric carcinomas. Although SFRP2 was methylated in almost all gastric carcinomas (97.0%) and more than half of the normal gastric mucosa samples (62.5%), extensive methylation of the SFRP2 promoter region was much more common in gastric cancer (71.7%) than in normal gastric mucosa samples (11.1%) and was more frequent in MSI-high (92.3%) than in MSI-low and microsatellite-stable gastric cancers (67.4%).

Taken together, these findings demonstrated that although the spectrum of methylation in both RASSF2 and SFRP2 was different in the stomach and colorectum, in both organs, extensive methylation of both genes occurred in a disease-specific manner. The combination of extensively methylated RASSF2 and SFRP2 was frequently present in the advanced gastric and colorectal cancer regardless of MSI status (Supplementary Figure 3, available online).

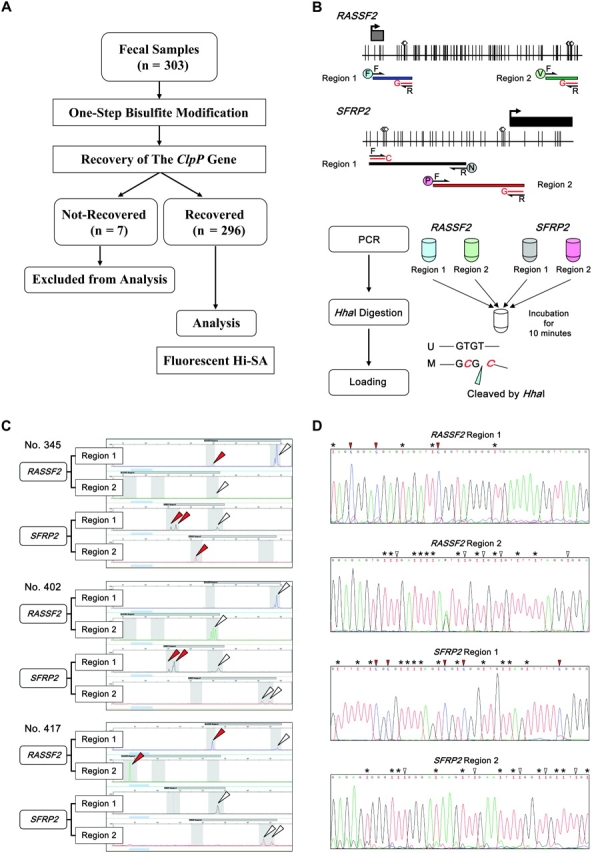

Recovery of Human Methylation Marker DNA From Feces

To investigate the influence of non-neoplastic or inflammatory lesions in the gastrointestinal lumen on fecal DNA methylation, we analyzed fecal DNA methylation using the Hi-SA method that we developed (see “Methods,” outline of the method in Figure 2 and some additional examples in Supplementary Figure 4, available online). We tabulated the results obtained with 296 fecal samples by clinical disease stage based on colonoscopy and esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy results that were confirmed after collection of each patient's fecal material. The characteristics of the patients from whom the fecal specimens were taken are listed in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Fluoroscence High-sensitivity assay for bisulfite DNA (Hi-SA). A) Analytic strategy of the fecal DNA methylation study and number of samples for analysis. B) Schematic representation of RASSF2 and SFRP2 promoter regions and strategy of fluorescence Hi-SA. Black arrows indicate nonmethylation-specific forward (F) or reverse (R) primers (same as Combined Bisulfite Restriction Analysis primers, as described in Supplementary Table 1, available online). Gray squares represent noncoding exon 1 regions; black squares represent coding exon 2 regions; arrows on the squares indicate transcriptional start sites. Vertical lines indicate CpG sites. White diamonds represent HhaI restriction enzyme recognition sequences. Symbols in circles: F, V, N, and P denote fluorescent dyes, 6-FAM, VIC, NED, and PET, respectively. A red line with a symbol (G or C) denotes a methylation-specific internal primer. Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) for fluorescence Hi-SA were done in different tubes for each target sequence. Then, each set of PCR products for a given patient was pooled together and digested with HhaI at 37°C for 10 min. HhaI recognizes and cleaves the “GCGC” sequence. “U” denotes the unmethylated allele and “M” denotes the methylated allele. C) Representative results of fluorescence Hi-SA from fecal samples. For each of three patients’ samples, the panels show the detection of methylation status by fluorescence Hi-SA in the RASSF2 region 1, RASSF2 region 2, SFRP2 region 1, and SFRP2 region 2 (as labeled). Red arrows indicate methylated alleles that were cleaved by HhaI. White arrows indicate unmethylated alleles that were not cleaved by HhaI. D) Representative results of bisulfite DNA cloning and sequencing from fecal DNA samples. RASSF2 region 1 was from sample 345 (methylated) and RASSF2 region 2 was from sample 402 (unmethylated). SFRP2 region 1 was from sample 402 (methylated) and SFRP2 region 2 was from sample 417 (unmethylated). Asterisks indicate unmethylated cytosines that are not a component of a CpG site but were converted to uracil by the fecal bisulfite modification. White arrows indicate unmethylated cytosines that are a component of a CpG site and were converted to uracils by the fecal bisulfite modification; Red arrows indicate methylated cytosines in a CpG site.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients for fecal analysis categorized by the most advanced lesion identified at colonoscopy and endoscopy*

| Diagnosis | No. | Mean age, y (SD) | Men, No. (%) | Proximal tumor location,† No. (%) |

| Subjects without neoplastic or active diseases‡ | 113 | 66.1 (12.5) | 48 (42.5) | — |

| Colorectal hyperplastic polyps | 12 | 61.2 (9.7) | 7 (58.3) | 0 (0) |

| Colorectal adenomas | 56 | 64.6 (12.2) | 36 (64.3) | 25 (44.6) |

| Nonadvanced adenomas§ | 29 | 62.7 (12.5) | 18 (62.1) | 17 (58.6) |

| Advanced adenomas‖ | 27 | 66.7 (11.7) | 18 (66.7) | 8 (29.6) |

| Colorectal cancer | 84 | 65.2 (11.3) | 48 (57.1) | 28 (33.3) |

| TNM stage (I and II) | 40 | 66.4 (11.2) | 22 (55.0) | 15 (37.5) |

| TNM stage (III and IV) | 44 | 64.1 (11.5) | 26 (59.1) | 13 (29.6) |

| Ischemic colitis | 4 | 72.0 (15.1) | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 2 | 68.5 (6.4) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) |

| Gastric and/or duodenal ulcer | 4 | 60.0 (16.6) | 3 (75.0) | — |

| Gastric cancer | 21 | 67.2 (13.8) | 18 (85.7) | — |

| TNM stage (I and II) | 10 | 66.8 (12.8) | 10 (100) | — |

| TNM stage (III and IV) | 11 | 67.6 (15.2) | 8 (72.7) | — |

TNM = TNM staging.

Number (%) of tumors located proximal to the splenic flexure.

Subjects without neoplastic or active diseases include two cases of erosive gastritis, 31 cases of chronic gastritis, 13 cases of chronic gastritis and colon diverticula, seven cases of chronic gastritis and hemorrhoids, seven cases of colon diverticula, and two cases of hemorrhoids.

Nonadvanced adenomas were single tubular adenomas less than 1 cm in diameter in the colorectum.

Advanced adenomas were colonic adenomatous polyps containing villous architecture, colonic adenomatous polyps 1 cm or more in diameter showing serrated architecture, colonic tubular adenomas 1 cm or more in diameter, or multiple (≥2) tubular adenomas in the colorectum.

We added the number of human loci in RASSF2 and SFRP2 that were successfully amplified from fecal DNA as the recovery score (Table 3). The trends in recovery of RASSF2 and SFRP2 DNA from feces with disease stage are shown in Table 4 (also see Supplementary Figure 5, available online). Recovery scores increased with each progressive stage of colorectal neoplasia (subjects without neoplastic or active disease vs patients with colorectal adenomas, mean recovery score = 1.27 vs 1.86, P = .009; patients with colorectal adenomas vs patients with colorectal cancers, mean recovery score = 1.86 vs 3.21, P < .001). Although the number of samples was small, recovery scores were higher for fecal specimens from patients with ulcerative colitis compared with subjects without neoplastic or active diseases (subjects with colitis vs subjects without neoplastic or active diseases, mean recovery score = 4.00 vs 1.27, P = .020; Table 3), as were recovery scores from gastric cancer patients compared with subjects without neoplastic or active diseases (patients with gastric cancers vs subjects without neoplastic or active diseases, mean recovery score = 2.38 vs 1.27, P = .019; Table 3). In contrast, recovery scores for patients with ischemic colitis, hyperplastic polyps, and gastric and/or duodenal ulcers were not statistically significantly different from subjects without neoplastic or active diseases. We also found no statistically significant difference in the mean recovery scores for tumors located in the proximal and distal colon. Although DNA recovery from feces varied for different markers, it tended to be most efficient from colorectal and gastric cancer patients with late-stage disease.

Table 3.

Summary of recovery and methylation scores from fecal samples*

| Recovery score, No. (%) |

Mean recovery score (SD) | P (comparison)† | Methylation Score, No. (%) |

Mean methylation score (SD) | P (comparison)† | ||||||||||

| Diagnosis | No. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Subjects without neoplastic or active diseases | 113 | 41 (36.3) | 30 (26.6) | 21 (18.6) | 13 (11.5) | 8 (7.1) | 1.27 (1.26) | 101 (89.4) | 9 (8.0) | 3 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.13 (0.41) | ||

| Colorectal hyperplastic polyps | 12 | 4 (33.3) | 2 (16.7) | 3 (25.0) | 2 (16.7) | 1 (8.3) | 1.50 (1.38) | .563 (vs normal)‡ | 9 (75.0) | 2 (16.7) | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.33 (0.65) | .141 (vs normal)‡ |

| Colorectal adenomas | 56 | 12 (21.4) | 13 (23.2) | 12 (21.4) | 9 (16.1) | 10 (17.9) | 1.86 (1.41) | .009 (vs normal)‡ | 36 (64.3) | 14 (25.0) | 3 (5.4) | 2 (3.6) | 1 (1.8) | 0.54 (0.89) | <.001 (vs normal)‡ |

| Nonadvanced adenomas | 29 | 7 (24.1) | 7 (24.1) | 5 (17.2) | 8 (27.6) | 2 (6.9) | 1.69 (1.31) | 21 (72.4) | 7 (24.1) | 1 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.31 (0.54) | ||

| Proximal | 17 | 4 (23.5) | 4 (23.5) | 3 (17.7) | 5 (29.4) | 1 (5.9) | 1.71 (1.31) | .928 (vs distal)§ | 12 (70.6) | 5 (29.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.29 (0.47) | .910 (vs distal)§ |

| Distal | 12 | 3 (25.0) | 3 (25.0) | 2 (16.7) | 3 (25.0) | 1 (8.3) | 1.67 (1.37) | 9 (75.0) | 2 (16.7) | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.33 (0.65) | ||

| Advanced adenomas | 27 | 5 (18.5) | 6 (22.2) | 7 (25.9) | 1 (3.7) | 8 (29.6) | 2.04 (1.51) | 15 (55.6) | 7 (25.9) | 2 (7.4) | 2 (7.4) | 1 (3.7) | 0.78 (1.12) | ||

| Proximal | 8 | 3 (37.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 3 (37.5) | 2.00 (1.85) | .891 (vs distal)§ | 5 (62.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 0.88 (1.34) | .906 (vs distal)§ |

| Distal | 19 | 2 (10.5) | 6 (31.6) | 5 (26.3) | 1 (5.3) | 5 (26.3) | 2.05 (1.39) | 10 (52.6) | 6 (31.6) | 2 (10.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.3) | 0.74 (1.05) | ||

| Colorectal cancer | 84 | 3 (3.6) | 5 (6.0) | 13 (15.5) | 13 (15.5) | 50 (59.5) | 3.21 (1.13) | <.001 (vs adenoma)‖ | 21 (25.0) | 23 (27.4) | 18 (21.4) | 14 (16.7) | 8 (9.5) | 1.58 (1.29) | <.001 (vs adenoma)‖ |

| TNM stage (I and II) | 40 | 3 (7.5) | 3 (7.5) | 7 (17.5) | 7 (17.5) | 20 (50.0) | 2.95 (1.30) | 11 (27.5) | 13 (32.5) | 7 (17.5) | 6 (15.0) | 3 (7.5) | 1.43 (1.26) | ||

| Proximal | 15 | 1 (6.7) | 2 (13.3) | 3 (20.0) | 2 (13.3) | 7 (46.7) | 2.80 (1.37) | .589 (vs distal)§ | 5 (33.3) | 6 (40.0) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (6.7) | 1.20 (1.26) | .333 (vs distal)§ |

| Distal | 25 | 2 (8.0) | 1 (4.0) | 4 (16.0) | 5 (20.0) | 13 (52.0) | 3.04 (1.27) | 6 (24.0) | 7 (28.0) | 6 (24.0) | 4 (16.0) | 2 (8.0) | 1.56 (1.26) | ||

| TNM stage (III and IV) | 44 | 0 (0) | 2 (4.6) | 6 (13.6) | 6 (13.6) | 30 (68.2) | 3.45 (0.90) | 10 (22.7) | 10 (22.7) | 11 (25.0) | 8 (18.2) | 5 (11.4) | 1.73 (1.32) | ||

| Proximal | 13 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0) | 11 (84.7) | 3.69 (0.75) | .179 (vs distal)§ | 4 (30.8) | 4 (30.8) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (15.4) | 2 (15.4) | 1.54 (1.51) | .469 (vs distal)§ |

| Distal | 31 | 0 (0) | 2 (6.5) | 4 (12.9) | 6 (19.4) | 19 (61.3) | 3.35 (0.95) | 6 (19.4) | 6 (19.4) | 10 (32.3) | 6 (19.4) | 3 (9.7) | 1.81 (1.25) | ||

| Ischemic colitis | 4 | 2 (50.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 1.00 (1.41) | .634 (vs normal)‡ | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.25 (0.50) | .394 (vs normal)‡ |

| Ulcerative colitis | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 4.00 (0) | .020 (vs normal)‡ | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2.00 (0) | <.001 (vs normal)‡ |

| Gastric and/or duodenal ulcer | 4 | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0) | 2 (50.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 2.00 (0.82) | .154 (vs normal)‡ | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | .494 (vs normal)‡ |

| Gastric cancer | 21 | 4 (19.0) | 2 (9.5) | 4 (19.0) | 4 (19.0) | 7 (33.3) | 2.38 (1.53) | .002 (vs normal)‡ | 9 (42.9) | 9 (42.9) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 0.76 (0.83) | <.001 (vs normal)‡ |

| TNM stage (I and II) | 10 | 1 (10.0) | 1 (10.0) | 3 (30.0) | 1 (10.0) | 4 (40.0) | 2.60 (1.43) | 4 (40.0) | 4 (40.0) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0) | 0.90 (0.99) | ||

| TNM stage (III and IV) | 11 | 3 (27.3) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | 3 (27.3) | 3 (27.3) | 2.18 (1.66) | 5 (45.5) | 5 (45.5) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.64 (0.67) | ||

TNM = TNM staging.

All P values (two-sided) were calculated by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

P values compared the recovery scores from patients and subjects without neoplastic or active diseases.

P values compared proximal and distal samples in each subgroup.

P values compared colorectal cancer and colorectal adenomas.

Table 4.

Summary of DNA recovery from fecal samples for RASSF2 and SFRP2 genes*

|

RASSF2 recovery status, No. (%) |

SFRP2 recovery status, No. (%) |

||||||||

| Diagnosis | No. | Region 1 recovered | Region 2 recovered | One locus recovered | Two loci recovered | Region 1 recovered | Region 2 recovered | One locus recovered | Two loci recovered |

| Subjects without neoplastic or active diseases | 113 | 48 (42.5) | 37 (32.7) | 29 (25.7) | 28 (24.8) | 28 (24.8) | 30 (26.5) | 36 (31.8) | 11 (9.7) |

| Colorectal hyperplastic polyps | 12 | 5 (41.7) | 5 (41.7) | 2 (16.7) | 4 (33.3) | 3 (25.0) | 5 (41.7) | 4 (33.3) | 2 (16.7) |

| Colorectal adenomas | 56 | 28 (50.0) | 33 (58.9) | 11 (19.6) | 20 (35.7) | 19 (33.9) | 32 (57.1) | 19 (33.3) | 16 (28.6) |

| Nonadvanced adenomas | 29 | 13 (44.8) | 10 (34.5) | 7 (24.1) | 8 (27.6) | 8 (27.6) | 16 (55.2) | 12 (41.4) | 7 (24.1) |

| Advanced adenomas | 27 | 15 (55.6) | 13 (48.1) | 4 (14.8) | 12 (44.4) | 11 (40.7) | 16 (59.3) | 9 (33.3) | 9 (33.3) |

| Colorectal cancer | 84 | 71 (84.5) | 69 (82.1) | 10 (11.9) | 65 (77.4) | 62 (73.8) | 68 (81.0) | 16 (19.0) | 57 (67.9) |

| TNM stage (I and II) | 40 | 30 (75.0) | 28 (70.0) | 6 (15.0) | 26 (65.0) | 28 (70.0) | 32 (80.0) | 8 (20) | 26 (65.0) |

| TNM stage (III and IV) | 44 | 41 (93.2) | 41 (93.2) | 4 (9.1) | 39 (88.6) | 34 (77.3) | 36 (81.8) | 8 (18.2) | 31 (70.5) |

| Ischemic colitis | 4 | 1 (25.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (25.0) | 2 (50.0) | 0 (0) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 2 | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) |

| Gastric and/or duodenal ulcer | 4 | 3 (75.0) | 3 (75.0) | 0 (0) | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (25.0) | 2 (50.0) | 0 (0) |

| Gastric cancer | 21 | 13 (61.9) | 12 (57.1) | 5 (23.8) | 10 (47.6) | 12 (57.1) | 13 (61.9) | 3 (14.3) | 11 (52.4) |

| TNM stage (I and II) | 10 | 7 (70.0) | 6 (60.0) | 3 (30.0) | 5 (50.0) | 6 (60.0) | 7 (70.0) | 1 (10.0) | 6 (60.0) |

| TNM stage (III and IV) | 11 | 6 (54.5) | 6 (54.5) | 2 (18.2) | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) | 6 (54.5) | 2 (18.2) | 5 (45.5) |

TNM = TNM staging.

Methylation Status of Human Markers in Fecal DNA

When we examined the methylation profiles of RASSF2 and SFRP2 in fecal DNA (Tables 3 and 5 and Supplementary Figure 6, available online), we found that overall methylation (ie, partially plus extensively methylated samples) in RASSF2 was lowest in subjects without neoplastic or active diseases (5.3%), intermediate in patients with colorectal adenomas (12.6%), and highest in individuals with colorectal cancer (45.3%). Extensive RASSF2 methylation was absent in subjects without neoplastic or active diseases (0%), infrequent in patients with adenomas (1.9%), and most frequent in patients with colorectal cancer (17.9%). For colorectal adenoma, extensive methylation of the RASSF2 gene was observed only in fecal DNA from patients with advanced adenomas (3.7%).

Table 5.

Summary of the methylation of RASSF2 and SFRP2 genes in fecal samples*

|

RASSF2 methylation status, No. (%) |

SFRP2 methylation status, No. (%) |

||||||||

| Diagnosis | No. | Region 1 methylated | Region 2 methylated | Partially methylated | Extensively methylated | Region 1 methylated | Region 2 methylated | Partially methylated | Extensively methylated |

| Subjects without neoplastic or active diseases | 113 | 3 (2.7) | 3 (2.7) | 6 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (3.5) | 5 (4.4) | 9 (8.0) | 0 (0) |

| Colorectal hyperplastic polyps | 12 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (8.3) | 3 (25.0) | 2 (16.7) | 1 (8.3) |

| Colorectal adenomas | 56 | 5 (8.9) | 3 (5.4) | 6 (10.7) | 1 (1.9) | 12 (21.4) | 10 (17.9) | 14 (25.0) | 4 (7.1) |

| Nonadvanced adenomas | 29 | 0 (0) | 1 (3.5) | 1 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 4 (13.8) | 4 (13.8) | 8 (27.6) | 0 (0) |

| Advanced adenomas | 27 | 5 (18.5) | 2 (7.4) | 5 (18.5) | 1 (3.7) | 8 (29.6) | 6 (22.2) | 6 (22.2) | 4 (14.8) |

| Colorectal cancer | 84 | 23 (27.4) | 30 (35.7) | 23 (27.4) | 15 (17.9) | 48 (57.1) | 32 (38.1) | 26 (31.0) | 27 (32.1) |

| TNM stage (I and II) | 40 | 10 (25.0) | 9 (22.5) | 9 (22.5) | 5 (12.5) | 23 (57.5) | 15 (37.5) | 14 (35.0) | 12 (30.0) |

| TNM stage (III and IV) | 44 | 13 (29.6) | 21 (47.7) | 14 (31.8) | 10 (22.7) | 25 (56.8) | 17 (38.6) | 12 (27.3) | 15 (34.1) |

| Ischemic colitis | 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 2 | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) |

| Gastric and/or duodenal ulcer | 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Gastric cancer | 21 | 0 (0) | 4 (19.0) | 4 (19.0) | 0 (0) | 8 (38.1) | 4 (19.0) | 8 (38.1) | 2 (9.5) |

| TNM stage (I and II) | 10 | 0 (0) | 2 (20.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0 (0) | 4 (40.0) | 3 (30.0) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (20.0) |

| TNM stage (III and IV) | 11 | 0 (0) | 2 (18.2) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0) | 4 (36.4) | 1 (9.1) | 5 (45.5) | 0 (0) |

TNM = TNM staging.

Similar patterns of methylation were seen for SFRP2 from fecal DNA, with a lower frequency of overall methylation in subjects without neoplastic or active diseases (8.0%), an intermediate frequency in colorectal adenomas (32.1%), and the highest frequency in colorectal cancer (63.1%). Extensive SFRP2 methylation was absent in subjects without neoplastic or active diseases (0%), infrequent in patients with adenomas (7.1%), and most frequent in patients with colorectal cancer (32.1%). As for RASSF2, extensive methylation of the SFRP2 gene in patients with adenoma was only seen in those with advanced adenomas (14.8%).

Although there was no evidence of RASSF2 methylation in fecal DNA from patients with hyperplastic polyps and ischemic colitis, SFRP2 was methylated in patients with hyperplastic polyps (extensive methylation, 8.3%; partial methylation, 16.7%) and ischemic colitis (extensive methylation, 0%; partial methylation, 25.0%; Table 5). Of the two samples from patients with ulcerative colitis, RASSF2 was partially methylated in one case and SFRP2 was methylated in both.

In fecal samples from patients with gastric and/or duodenal ulcers, no methylation was observed in either RASSF2 or SFRP2. However, in fecal samples from gastric cancer patients, RASSF2 was methylated with a frequency of 19.0% (partial methylation, 19.0%; extensive methylation, 0%) and SFRP2 was methylated with a frequency of 47.6% (partial methylation, 38.1%; extensive methylation, 9.5%; Table 5).

Similar to what we did for a recovery score, we added the number of markers showing methylation and tabulated this as the methylation score (Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 6, available online). Methylation scores substantially increased with tumor progression for colorectal cancers. In contrast, methylation scores for patients with ischemic colitis, hyperplastic polyps, and gastric and/or duodenal ulcers were not substantially different from subjects without neoplastic or active diseases and there were no statistically significant differences in methylation scores for colorectal cancers from different locations (proximal or distal colon).

From the methylation score, one or more methylated markers were identified in fecal DNA specimens from 12 of 21 (57.1%) patients with gastric cancer, 12 of 27 (44.4%) subjects with advanced colorectal adenomas, and 63 of 84 (75.0%) subjects with colorectal cancer, but only 12 of 113 (10.6%) subjects without neoplastic or active diseases (gastric cancer vs undiseased, difference = 46.5%, 95% CI = 24.6% to 68.4%, P < .001; colorectal cancer vs undiseased, difference = 64.4%, 95% CI = 53.5% to 75.2%, P < .001; colorectal adenoma vs undiseased, difference = 33.8%, 95% CI = 14.2% to 53.4%, P < .001).

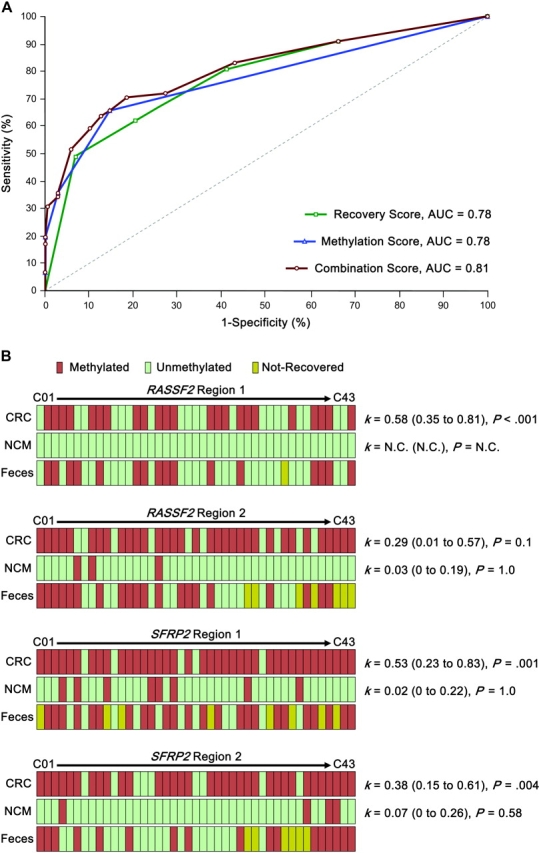

Identification of Gastrointestinal Cancers Using Fecal DNA Methylation and Recovery Scores

Next, we statistically examined the screening performance for the recovery score, the methylation score, and the combination score, a score calculated from methylation score combined with recovery score, to distinguish patients with advanced lesions (colorectal cancers, colorectal advanced adenomas, and gastric cancers) from those without advanced lesions (colorectal nonadvanced adenomas, colorectal hyperplastic polyps, and subjects without neoplastic or active diseases) in asymptomatic cases (symptomatic cases such as ulcerative colitis, ischemic colitis, and gastric and/or duodenal ulcer were excluded). ROC curves show the fraction of true-positive results (sensitivity) and false-positive results (1 − specificity) for various cutoff levels of recovery score, methylation score, and combination score (Figure 3, A, and Supplementary Table 2, available online). The areas under the ROC curve for the recovery, methylation, and combination scores were 0.78 (95% CI = 0.72 to 0.83), 0.78 (95% CI = 0.73 to 0.82), and 0.81 (95% CI = 0.76 to 0.86), respectively. We observed that the combination score improved the characteristics of the screening test for advanced lesions by bringing the curve closer to the y-axis (vs methylation score, P = .02). Finally, we compared the ROC curves for cross-validation. The effect of dropping one observation was so slight that the ROC curve for the cross-validation was identical to the one for the combination score using the original coefficients from the logistic regression for the full data (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 7, available online).

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and DNA methylation profiles from matched colon and fecal specimens from 43 colorectal cancer patients. A) ROC curves for various cutoff levels by the recovery score, the methylation score, and the combination score to screen subjects with advanced lesions (colorectal cancer, colorectal advanced adenomas, and gastric cancer) from subjects with nonadvanced lesions (colorectal nonadvanced adenomas, colorectal hyperplastic polyps, and subjects without neoplastic or active diseases), respectively. Sensitivity and 1 minus specificity (ROC curves) are shown at various threshold values. The combination score improves the characteristics of the screening test for advanced lesions by bringing the curve closer to the y-axis. AUC denotes area under the curve. B) DNA methylation profiles of primary colorectal cancers (CRC), normal colonic mucosa (NCM), and feces from 43 matched CRC patients. DNA from tumors and normal colonic mucosa was analyzed by Combined Bisulfite Restriction Analysis. Fecal DNA was analyzed by fluorescent high-sensitivity assay for bisulfite DNA. In each panel, the κ values (with 95% confidence intervals) compared the concordance for fecal and tumor DNA (top figures) and for fecal and matched normal epithelial DNA (bottom figure; N.C. = not calculated). P values were calculated by Fisher exact test. All tests were two-sided.

DNA Methylation in Matched Tumors, Normal Mucosa, and Feces From Colorectal Cancer Patients

Last, to determine whether the methylation profiles identified in fecal DNA accurately reflected those present in the tumors, we collected and analyzed DNA from tumors, normal colonic mucosa, and feces from 43 patients with colorectal cancer (Figure 3, B). RASSF2 regions 1 and 2 could be recovered in 42 (98%) and 36 (84%) of 43 matched feces, respectively. In RASSF2 region 1, only one patient would be read as a false positive and seven patients as false negatives. In RASSF2 region 2, two patients would be read as false positives (one patient showed unmethylation in cancer tissues but methylation in normal colonic mucosa) and nine patients as false negatives. SFRP2 regions 1 and 2 could be recovered in 35 (81%) and 37 (86%) of 43 matched feces, respectively. In SFRP2 region 1, no patients would be read as a false positive and six patients as false negatives. In SFRP2 region 2, no patient would be read as a false positive and 12 patients as false negatives. The concordance index (κ) for fecal DNA methylation with tumors was greater than with normal epithelium for all loci analyzed, suggesting the robustness of this newly developed methylation assay.

Discussion

In this study, we describe a novel assay for DNA methylation in exfoliated human gastrointestinal cells in feces that may be the first noninvasive screening method to detect both gastric and colorectal cancers, and which therefore has the potential to improve the mortality associated with both cancers.

Feces remain among the most difficult specimens for PCR amplification because they contain PCR inhibitors including bile salts, hemoglobin degradation products, and complex polysaccharides from dietary vegetable matter. In most stool-based assays, PCR inhibitors are removed by a DNA purification step at the beginning. Previously, when we intended to examine DNA methylation profiles in bisulfite-modified DNA from feces, we would always repurify the DNA after bisulfite modification to remove salts, such as bisulfite. In this simplified one-step Hi-SA fecal DNA methylation assay, PCR inhibitors are removed during DNA purification after bisulfite modification, and the need for preliminary DNA purification is eliminated. In our strategy, the substantial dilution of fecal specimens allowed both more efficient bisulfite modification and more robust PCR amplification efficiency and appears to have minimized the influence of PCR inhibitors.

The use of fecal DNA tests to screen for colorectal cancer was first described in 1992 when Sidransky et al. (9) amplified KRAS mutations from fecal samples from colorectal cancer patients. Fecal DNA assays rely on the overall number of human epithelial cells shed from tumors or normal mucosa into the intestinal lumen (1) and on the ability to extract sufficient amounts and long fragments of DNA from exfoliated tumor cells for various molecular investigations (10–12,17,23). These assays exploit the fact that substantially shorter fragments of DNA are shed among exfoliated normal epithelial cells because they undergo anoikis, an apoptotic response to the absence of cell–matrix interactions including apoptotic DNA fragmentation mediated by the activation of caspases and other cell death signals (46,47). Consequently, neoplastic exfoliated cells that escape anoikis provide greater recovery of human DNA from feces of patients with gastrointestinal neoplasia as compared with subjects without neoplastic or active diseases.

We also noted that fecal DNA recovery rates were higher in patients with gastric cancer than in undiseased subjects, similar to what had been observed for colorectal cancer. Our results suggest that gastric cancers also frequently shed epithelial cells into the gastrointestinal lumen, and DNA from these cells is abundant enough to be recovered from the fecal material. However, DNA from cells shed by normal gastric mucosa into fecal materials is not as easily recovered. In this context, although 63% of primary normal gastric mucosal tissues showed SFRP2 region 1 methylation, only 14% (four of 28 recovered cases) of fecal DNA from subjects without neoplastic or active diseases was methylated in the same region and this methylation frequency was similar to that in primary normal colorectal mucosal tissues (15%). Hence, the differential methylation frequency seen in SFRP2 region 1 suggested that DNA from exfoliated normal gastric cells did not reach the feces, in agreement with earlier evidence that almost all exfoliated cells isolated from feces were of colonic origin (48). By demonstrating its success in detecting some gastric cancers, our findings suggest potentially greater utility for the fecal DNA assay: It is possible that the DNA shed by other gastrointestinal tumor cells (eg, pancreatic cancer) might also be recoverable and analyzed from fecal materials. The recovery rate of feces from subjects without neoplastic or active diseases is, however, always low and therefore there are slight variations in our ability to amplify certain loci or genes.

Selection of adequate biomarkers is critical to the success of any screening methodology. In this study, we used the RASSF2 and SFRP2 genes as biomarkers for our fecal DNA methylation assay after initial confirmation for the presence of extensive (ie, increasing) methylation of these gene promoters in both gastric and colorectal tumors. More importantly, these two genes were also relatively frequently methylated in Lynch syndrome colorectal cancer. Hence, these epigenetic markers could detect both patients with nonfamilial sporadic cancers and familial Lynch syndrome patients with equal efficiency.

Our findings also demonstrated that patients with ulcerative colitis and ischemic colitis showed methylation in their fecal DNA, although it is unclear whether this occurred at higher rates than among undiseased subjects. Because these diseases are typically symptomatic, these patients would not be counted as false positives with our fecal DNA methylation–based cancer screening strategy because this assay is designed for an asymptomatic mass population. Even if patients with these diseases were to participate in our fecal DNA methylation–based cancer screening strategy, we could diagnose these patients easily by a postscreen colonoscopy. However, even though our fecal DNA methylation–based cancer screening strategy has a potential to screen some gastric cancer patients as well as colorectal cancer patients, we could not diagnose gastric cancer patients easily by a postscreen colonoscopy. Therefore, to more easily predict which kind of neoplasia subjects might have using fecal DNA–methylation profiles, it will be necessary to discover tissue- or cancer-specific (methylated or unmethylated) markers for these diseases and include them in screening tests in the future.

By examining the presence of DNA methylation at one or more sites to screen for advanced gastric and colorectal tumors, the assay showed a sensitivity of 57.1% for patients with gastric cancer, 44.4% for advanced colorectal adenomas, and 75.0% for colorectal cancer, with a relatively high false-positive rate (10.6%) in subjects without neoplastic or active disease. Because a high false-positive rate increases the number of subsequent invasive cancer screening tests, an effort to reduce the false-positive rate is required. From this point of view, our assay has the flexibility to suit the situation. For example, if a screening process would require a minimal false-positive rate, we could use the presence of extensive methylation (methylation observed in both regions 1 and 2) in either or both genes as a new criterion in our fecal DNA methylation assay, which would decrease the false-positive rates in subjects without neoplastic or active diseases (0%, 95% CI = 0% to 3.3%), patients with hyperplastic polyps (8.3%, 95% CI = 1.5% to 35.4%), and patients with nonadvanced adenomas (0%, 95% CI = 0% to 11.7%), with reduction of sensitivity for gastric cancer to 9.5%, for colorectal advanced adenomas to 14.8%, and for colorectal cancer to 40.5% (Supplementary Figure 8, available online). Indeed, extensive methylation in both genes is a specific methylation pattern that is observed only in advanced gastric and colorectal tumors but is not found at high frequency. Therefore, using the presence of extensive methylation as a new criterion in our fecal DNA methylation assay would increase the specificity for subjects without neoplastic or active disease but decrease the sensitivity for subjects with neoplastic lesions.

Our methodology measured both fecal DNA recovery and methylation scores. Because aberrant DNA methylation in feces directly reflects the alterations present in malignant neoplasia, the presence of altered methylation patterns in fecal DNA is a potent predictor for colorectal and gastric neoplasia. In addition, because neoplastic epithelial cells escape a series of biological events that lead to apoptotic DNA fragmentation in exfoliated cells, the independent measure of human DNA recovery also serves as a predictor of neoplastic disease. According to our data, the combination of fecal DNA methylation status scores with measures of recovery rates improved our ability to screen for advanced lesions including large premalignant adenomas. However, it is possible that the efficiency of tumor screening could be further improved over the combination score for the biomarkers in this study (RASSF2 and SFRP2). To make the combination score an even more efficient predictor, it may be necessary to increase the number of biomarkers and optimize PCR conditions for our fecal DNA methylation–based cancer screening strategy.

In conclusion, we have presented several important lines of evidence that support the use of fecal DNA analysis for screening of both the sporadic and familial forms of colorectal cancer and for gastric cancer screening. We developed a novel single-step approach to extract human DNA from fecal specimens, to modify it with sodium bisulfite for methylation analysis, and to determine both methylation and recovery scores within a few hours. By identifying disease-specific methylation patterns for human fecal DNA from advanced gastric and colorectal tumors, we could more accurately identify subjects at high risk for developing, or having developed, advanced tumors. Further improvement of the method, possibly, even some day to detect pancreatic cancer, awaits future studies.

Funding

Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (20590572 to T.N. and 19390351 to N.M.). Suzuken Memorial Foundation 2007 to T.N. The National Institutes of Health (RO1 CA 72851 to C.R.B. and RO1 CA 129286 to A.G.). Funds from the Baylor Research Institute to C.R.B. and Baylor Health Care System Grant funds to A.G.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The funding sources had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the decision to submit the manuscript for publication; or the writing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Osborn NK, Ahlquist DA. Stool screening for colorectal cancer: molecular approaches. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(1):192–206. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(19):1365–1371. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305133281901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996;348(9040):1472–1477. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jorgensen OD, Sondergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996;348(9040):1467–1471. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandel JS, Church TR, Bond JH, et al. The effect of fecal occult-blood screening on the incidence of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(22):1603–1607. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morikawa T, Kato J, Yamaji Y, Wada R, Mitsushima T, Shiratori Y. A comparison of the immunochemical fecal occult blood test and total colonoscopy in the asymptomatic population. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(2):422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allison JE, Sakoda LC, Levin TR, et al. Screening for colorectal neoplasms with new fecal occult blood tests: update on performance characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(19):1462–1470. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levi Z, Rozen P, Hazazi R, et al. A quantitative immunochemical fecal occult blood test for colorectal neoplasia. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(4):244–255. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-4-200702200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sidransky D, Tokino T, Hamilton SR, et al. Identification of ras oncogene mutations in the stool of patients with curable colorectal tumors. Science. 1992;256(5053):102–105. doi: 10.1126/science.1566048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahlquist DA, Skoletsky JE, Boynton KA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening by detection of altered human DNA in stool: feasibility of a multitarget assay panel. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(5):1219–1227. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.19580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Traverso G, Shuber A, Levin B, et al. Detection of APC mutations in fecal DNA from patients with colorectal tumors. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(5):311–320. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong SM, Traverso G, Johnson C, et al. Detecting colorectal cancer in stool with the use of multiple genetic targets. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(11):858–865. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.11.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, Turnbull BA, Ross ME. Fecal DNA versus fecal occult blood for colorectal-cancer screening in an average-risk population. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(26):2704–2714. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahlquist DA, Sargent DJ, Loprinzi CL, et al. Stool DNA and occult blood testing for screen detection of colorectal neoplasia. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(7):441–450. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-7-200810070-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itzkowitz S, Brand R, Jandorf L, et al. A simplified, noninvasive stool DNA test for colorectal cancer detection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(11):2862–2870. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zou H, Taylor WR, Harrington JJ, et al. High detection rates of colorectal neoplasia by stool DNA testing with a novel digital melt curve assay. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(2):459–470. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muller HM, Oberwalder M, Fiegl H, et al. Methylation changes in faecal DNA: a marker for colorectal cancer screening? Lancet. 2004;363(9417):1283–1285. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen WD, Han ZJ, Skoletsky J, et al. Detection in fecal DNA of colon cancer-specific methylation of the nonexpressed vimentin gene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(15):1124–1132. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petko Z, Ghiassi M, Shuber A, et al. Aberrantly methylated CDKN2A, MGMT, and MLH1 in colon polyps and in fecal DNA from patients with colorectal polyps. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(3):1203–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oberwalder M, Zitt M, Wontner C, et al. SFRP2 methylation in fecal DNA—a marker for colorectal polyps. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23(1):15–19. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Z, Li L, Wang J. Hypermethylation of SFRP2 as a potential marker for stool-based detection of colorectal cancer and precancerous lesions. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(9):2287–2291. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9755-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenhard K, Bommer GT, Asutay S, et al. Analysis of promoter methylation in stool: a novel method for the detection of colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(2):142–149. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00624-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itzkowitz SH, Jandorf L, Brand R, et al. Improved fecal DNA test for colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(1):111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glockner SC, Dhir M, Yi JM, et al. Methylation of TFPI2 in stool DNA: a potential novel biomarker for the detection of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(11):4691–4699. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melotte V, Lentjes MH, van den Bosch SM, et al. N-Myc downstream-regulated gene 4 (NDRG4): a candidate tumor suppressor gene and potential biomarker for colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(13):916–927. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones PA, Laird PW. Cancer epigenetics comes of age. Nat Genet. 1999;21(2):163–167. doi: 10.1038/5947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herman JG, Baylin SB. Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(21):2042–2054. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ushijima T. Detection and interpretation of altered methylation patterns in cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(3):223–231. doi: 10.1038/nrc1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagasaka T, Goel A, Notohara K, et al. Methylation pattern of the O(6)-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase gene in colon during progressive colorectal tumorigenesis. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(11):2429–2436. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagasaka T, Koi M, Kloor M, et al. Mutations in both KRAS and BRAF may contribute to the methylator phenotype in colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(7):1950–1960. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki H, Gabrielson E, Chen W, et al. A genomic screen for genes upregulated by demethylation and histone deacetylase inhibition in human colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2002;31(2):141–149. doi: 10.1038/ng892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen L, Kondo Y, Rosner GL, et al. MGMT promoter methylation and field defect in sporadic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(18):1330–1338. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bedi A, Pasricha PJ, Akhtar AJ, et al. Inhibition of apoptosis during development of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;55(9):1811–1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Partik G, Kahl-Rainer P, Sedivy R, Ellinger A, Bursch W, Marian B. Apoptosis in human colorectal tumours: ultrastructure and quantitative studies on tissue localization and association with bak expression. Virchows Arch. 1998;432(5):415–426. doi: 10.1007/s004280050185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang S, Ingber DE. The structural and mechanical complexity of cell-growth control. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1(5):E131–E138. doi: 10.1038/13043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(2):74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Endoh M, Tamura G, Honda T, et al. RASSF2, a potential tumour suppressor, is silenced by CpG island hypermethylation in gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93(12):1395–1399. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nojima M, Suzuki H, Toyota M, et al. Frequent epigenetic inactivation of SFRP genes and constitutive activation of Wnt signaling in gastric cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26(32):4699–4713. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(2):594–642. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.agast970594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiong Z, Laird PW. COBRA: a sensitive and quantitative DNA methylation assay. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(12):2532–2534. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.12.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guarner F, Malagelada JR. Gut flora in health and disease. Lancet. 2003;361(9356):512–519. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12489-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zou H, Harrington JJ, Klatt KK, Ahlquist DA. A sensitive method to quantify human long DNA in stool: relevance to colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(6):1115–1119. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(3):837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akino K, Toyota M, Suzuki H, et al. The Ras effector RASSF2 is a novel tumor-suppressor gene in human colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(1):156–169. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brophy PD, Lang KM, Dressler GR. The secreted frizzled related protein 2 (SFRP2) gene is a target of the Pax2 transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(52):52401–52405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305614200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frisch SM, Screaton RA. Anoikis mechanisms. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13(5):555–562. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shanmugathasan M, Jothy S. Apoptosis, anoikis and their relevance to the pathobiology of colon cancer. Pathol Int. 2000;50(4):273–279. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2000.01047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albaugh GP, Iyengar V, Lohani A, Malayeri M, Bala S, Nair PP. Isolation of exfoliated colonic epithelial cells, a novel, non-invasive approach to the study of cellular markers. Int J Cancer. 1992;52(3):347–350. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.