Abstract

Following influenza-virus infection, CD8 T cells encounter mature, antigen-bearing dendritic cells within the draining lymph nodes (LN) and undergo activation, programmed proliferation and differentiation to effector cells prior to migrating to the lungs to mediate viral clearance. However, it remains unclear if CD8 T cells continue their proliferation after arriving in the lungs. To address this question, we have developed a novel, in vivo dual-label system using intranasal CFSE and BrdU administration to identify virus-specific CD8 T cells that are actively undergoing cell division while in the lungs. With this technique we demonstrate that a high frequency of virus-specific CD8 T cells incorporate BrdU while in the lungs and that this lung-resident proliferation contributes significantly to the magnitude of the antigen-specific CD8 T cell response following influenza-virus infection.

Keywords: Lung; Influenza Virus; T cells, Cytotoxic; Proliferation

Introduction

Control of a primary influenza virus infection requires the clearance of infected cells from the lungs by activated virus-specific CD8 T cells. Initiation of this CD8 T cell response requires migration of activated, viral-antigen bearing dendritic cells from the lungs to the lymph nodes (LN) (1–4). Upon interaction with these migratory DC, naïve antigen-specific CD8 T cells are thought to become activated and undergo several rounds of division and differentiation into effector cells. These effector virus-specific CD8 T cells then accumulate in the lungs where they mediate viral clearance through the killing of infected cells. Through analysis using CFSE dilution by transgenic influenza virus-specific CD8 T cells, it is evident that CD8 T cells proliferate extensively in the LN following their interactions with antigen-bearing DC (5, 6); however, it is less clear if all of the T cell division occurs in the LN or if further CD8 T cell proliferation occurs once arriving in the lungs. A recent publication by Wissinger et al. has suggested that following secondary infection with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), memory CD4 T cells undergo extensive proliferation within the lungs as determined by cell cycle analysis for DNA content using propidium iodide or the DNA binding dye Draq5 (7). These results support the hypothesis that lymphocytes can undergo active proliferation in the lungs following pulmonary viral infection; however, it remains unclear if this lung-resident proliferation is a trait unique to memory T cells and/or CD4 T cells, or if this observation extends to primary cytotoxic T cell responses.

The techniques currently available for examining cell division of lymphocytes in vivo, such as dilution of CFSE, BrdU incorporation or measurement of cell cycling by DNA content as described above (7), are limited because they do not allow identification of the location in which this proliferation occurred. Importantly, in the case of respiratory virus infection, these techniques have been useful for measuring the magnitude and rate of CD8 T cell proliferation following influenza virus infection(5, 6), and for measuring memory CD4 T cell cycling following RSV infection (7); but it has been difficult to differentiate between division that occurs in the LN from that which occurs in the lungs. Therefore, in order to better determine the locations of CD8 T cell expansion, we have developed a novel, dual-label system that utilizes intranasal CFSE administration to label all lung-resident CD8 T cells followed by intranasal BrdU administration to identify those cells incorporating BrdU and therefore undergoing active cell division. Herein, we demonstrate that a sizeable portion of influenza virus-specific CD8 T cells undergo at least one round of division after arriving in the lungs, and this proliferating population is detectable in the lungs as early as day 4 p.i‥ We further demonstrate, by blocking new emigration of CD8 T cells from the LN following influenza virus infection, that this lung-resident CD8 T cell proliferation can significantly contribute to the magnitude of the virus-specific CD8 T cell response in the lungs. Together, these results suggest that while a significant portion of virus-specific CD8 T cell division occurs in the LN following influenza virus infection, an immunologically significant amount of CD8 T cell proliferation continues to occur even after the CD8 T cells have arrived in the lungs.

Materials and Methods

Mice

6–12 week old female BALB/c mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD) and maintained in the animal care facility at the University of Iowa. Experiments were conducted according to federal and institutional guidelines and approved by the University of Iowa Animal Care and Use Committee.

Virus Infection

Mouse-adapted influenza A virus A/PuertoRico/8/34 (H1N1) was grown in the allantoic fluid of 10-day old embryonated chicken eggs, harvested, and stored as previously described (8). Mice were anesthetized with isofluorane and infected intranasally (i.n.) with a 3.155 × 104 pfu dose of A/PR/8/34 in 50 µl of Iscove’s media as previously described (8).

FTY720 Treatment

Influenza virus-infected BALB/c mice were injected daily i.p. with 0.5 mg/kg/day of FTY720 (Cayman Chemical) dissolved in sterile PBS (9, 10) starting on the indicated days p.i. through the time of analysis. Non-treated control mice received an equivalent volume of sterile PBS.

Influenza-specific T cell analysis

Lungs were removed, minced and single cell suspensions prepared as described (1, 5, 8). The cells were then stained with antibodies to CD8α (53-6.7) and BrdU incorporation was determined using the BrdU Flow Kit (both from BD Pharmingen) according to manufacturers instructions. Influenza-specific CD8 T cells were detected using MHC I tetramers to HA533 (H-2K(d)/IYSTVASSL); and NP147 (H2K(d)/TYQRTRALV). Cells were analyzed using a BD FACS Canto and FlowJo software. Tetramers were obtained from The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Tetramer Facility (Germantown, MD).

Assay for lung specific T cell proliferation

Mice were anesthetized using isofluorane and i.n. administered an 8 mM solution of CFSE diluted in Iscove’s media as previously described (1). 2 h later, the mice were again anesthetized and administered 0.8 mg BrdU in 80 µl sterile PBS i.n‥ Four h later, the lungs were harvested and single cell suspensions were stained as described above.

Results and Discussion

Kinetics of antigen-specific CD8 T cell responses following influenza virus infection

Before initiating experiments to measure the proliferation of influenza-specific CD8 T cells in the lungs, we first performed a detailed kinetic analysis of the influenza-specific CD8 T cell response. We observed that this sublethal dose of virus induces a robust expansion in both the frequency and number of total and influenza virus-specific CD8 T cells as measured by MHC I tetramers (supplemental Fig S1). Similar to previous reports (5, 6, 8), influenza-specific CD8 T cells begin arriving in the lungs on day 4 p.i. and continue to increase through days 8–10 p.i. following influenza virus infection.

I.n. BrdU and CFSE dual-labeling identifies CD8 T cells that have undergone proliferation in the lungs

BrdU incorporation is a widely used method to label and identify actively dividing cells in vivo. A recent study by Lawrence et al. (6) has demonstrated that BrdU labeling by i.p. injection or ingestion in the drinking water significantly underestimates the frequency of cells that are proliferating in the lungs. Instead, Lawrence et al. demonstrated that lymphocytes in the lungs were more successfully labeled by i.n. BrdU administration (6). However, due to drainage of the BrdU to the LN, it was difficult to determine the location of BrdU incorporation. We have similarly demonstrated that i.n. BrdU administration successfully labels proliferating CD8 T cells in the lungs following influenza virus infection (11). Given the kinetics of BrdU incorporation in vivo, our initial studies have shown that identification of proliferating CD8 T cells in the lungs during an infection is most accurately measured using a short 4–6 hour window following i.n. administration (11).

Because we wanted to differentiate between CD8 T cell proliferation that occurred in the lungs during influenza virus infection from that which occurred in the draining LN, we required a second labeling method to identify those T cells that were in the lungs at the time of i.n. BrdU administration and therefore incorporated BrdU as a direct result of proliferation within the lungs. We have previously developed a method of i.n. CFSE administration that specifically labels cells that are present in the lungs, but not those that are present in the lung-draining LN (1). Therefore, we chose to combine i.n. CFSE administration with i.n. BrdU treatment to specifically identify those CD8 T cells that are undergoing at least one round of active proliferation in the lungs following influenza virus infection.

Given the time dependent nature of our dual-label system, we chose to utilize the experimental approach outlined in supplemental Figure S2A. For these experiments, BALB/c mice were infected i.n. with a sublethal dose of influenza A virus A/PR/8/34. Subsequently, on days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 p.i., mice were administered i.n. CFSE, followed 2 hours later by i.n. BrdU. After 4 hours of incubation, the mice were sacrificed and their lungs were removed and analyzed by flow cytometry. Using the representative gating strategy shown in supplemental Figure S2B and S3, we subsequently examined the lungs for the frequency and number of lung-resident influenza virus-specific CD8 T cells present at the time of CFSE labeling (i.e. CFSE+), and assessed the cells for proliferation as measured by BrdU incorporation. To differentiate between CFSE+ and CFSEneg cells, samples were compared to a mouse that received i.n. PBS+DMSO carrier without CFSE (filled grey, top panels).

Proliferation by influenza-virus specific CD8 T cells in the lungs

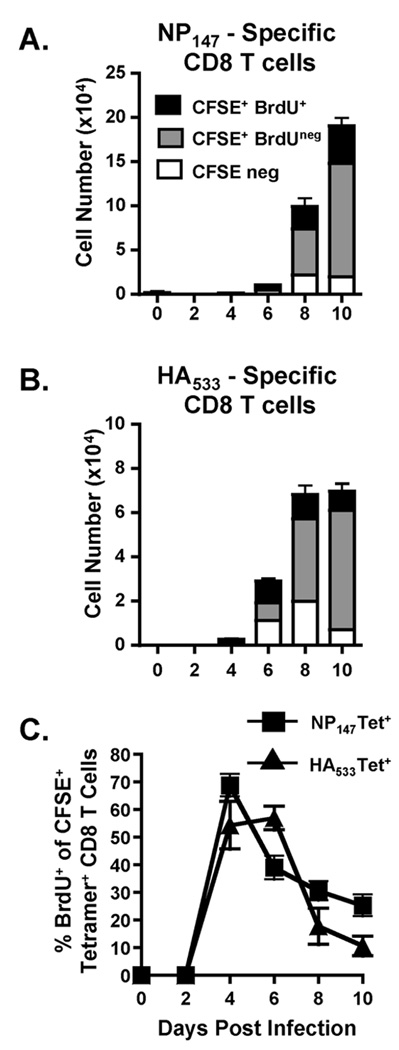

We next wanted to utilize the dual-label CFSE-BrdU labeling technique to determine if influenza virus-specific CD8 T cells were undergoing cell division once arriving in the lungs. Therefore, we infected mice with a sublethal dose of influenza virus and treated the mice with i.n. CFSE followed by i.n. BrdU as outlined in Figure S2A. Mice were sacrificed and their lungs were removed and analyzed for numbers of NP147-specific (Fig 1A) and HA533-specific (Fig 1B) T cells. It is important to note that the magnitude of the pulmonary influenza-specific CD8 T cell response observed on day 10 p.i. is very similar in either the absence (supplemental Fig S1) or presence (Fig 1) of CFSE and BrdU administration, suggesting that this treatment does not substantially alter the influenza-specific CD8 T cell response in the lungs. For this study, we analyzed three primary populations: the CFSE+BrdU+ population (black bars) that was in the lungs at the time of CFSE labeling and had undergone at least one round of division within the lungs based upon BrdU incorporation; the CFSE+BrdUneg population (grey bars) that was present within the lungs at the time of CFSE labeling but did not undergo proliferation within the 4 hour window and therefore, did not incorporate BrdU; and the CFSEneg population (open bars) that constituted a very minor population of influenza-specific CD8 T cells. As demonstrated in Figure 1, the majority of influenza-specific CD8 T cells are CFSE+ (grey and black bars), suggesting that they were present in the lungs at the time of CFSE administration. Further examination of the CFSE+ cell population demonstrates that a sizeable portion of these cells are also positive for BrdU incorporation, suggesting that, during the time of analysis, a substantial portion of the virus-specific CD8 T cells that were present in the lungs underwent at least one round of division. Strikingly, while the numbers of virus-specific CD8 T cells in the lungs on day 4 p.i. are very low, the proportion of virus-specific CD8 T cells that are incorporating BrdU while in the lungs is as high as 70% at early time points p.i. (Day 4, Fig 1C, supplemental Fig S3).

FIGURE 1.

Proliferation within the lungs by pulmonary antigen-specific CD8 T cells following influenza virus infection. On days 0–10 p.i., influenza-infected mice were treated i.n. with CFSE followed by BrdU as shown in supplemental Figure 2A. 4 h later, mice were sacrificed and their lungs examined by flow cytometry for total numbers of CFSE+BrdU+ (black bars), CFSE+BrdUneg (grey bars) and CFSEneg NP147-specific tetramer+(A) and HA533-specific tetramer+(B) CD8 T cells. The lungs were also analyzed for the frequency (C) of CFSE+ NP147-specific tetramer+(squares) and HA533-specific tetramer+(triangles) CD8 T cells that incorporated BrdU during the 4-hour window of analysis. Data are representative of 2 separate experiments. n=3–5 mice/group.

Given the short window of analysis used to a examine CFSE and BrdU labeling, the majority of influenza-specific CD8 T cells in this analysis were CFSE+; however, there was a small, but detectable population of CFSEneg influenza-specific CD8 T cells (white bars, Figure 1A and B) present in the lungs at the time of analysis. It is unlikely that these CFSEneg cells underwent sufficient proliferation to dilute CFSE beyond detection. Instead, these cells are likely a result of two possibilities: 1) they are cells that migrated into the lungs from the LN during the period following CFSE administration, or 2) the cells are a result of inefficient i.n. CFSE labeling.

Proliferation of lung-resident influenza-specific CD8 T cells contributes to the magnitude of the influenza virus-specific CD8 T cell response in the lungs

Whereas the dual-label CFSE-BrdU administration system allows us to identify CD8 T cells that have undergone at least one round of proliferation after arriving in the lungs, it remained unclear to what extent this proliferation contributed to the overall magnitude of the pulmonary influenza virus-specific response. In an effort to address the relevancy of this proliferation in the adaptive response, we next administered the Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonist FTY720. FTY720 is an immunomodulatory drug that is known to inhibit lymphocyte emigration from lymphoid organs and a variety of peripheral tissues, including the lungs (9, 10). By administering FTY720 on multiple days p.i., we could prevent the recruitment of new virus-specific CD8 T cells from the LN to the lungs and assess the role of CD8 T cell proliferation within the lungs independent of new cell recruitment. Prior to initiating experiments to assess the role of virus-specific CD8 T cell proliferation within the lungs, however, we first wanted to test the efficacy of daily FTY720 treatment on inhibiting CD8 T cell emigration from the LN following influenza virus infection. Therefore, we infected mice with a sublethal dose of influenza virus and initiated FTY720 administration on day 2 p.i., prior to release of virus-specific CD8 T cells from the LN, and then continued this administration daily throughout the experiment. Virus-specific CD8 T cell numbers in the lungs were then assessed on days 5–10 p.i‥ While daily FTY720 treatment did not completely ablate release of virus-specific CD8 T cells from the LN to the lung following influenza virus infection, we observed a highly significant reduction in the numbers of tetramer positive CD8 T cells (supplemental Fig S4), suggesting that daily FTY720 is highly effective at blocking emigration of virus-specific CD8 T cells from the LN following influenza virus infection.

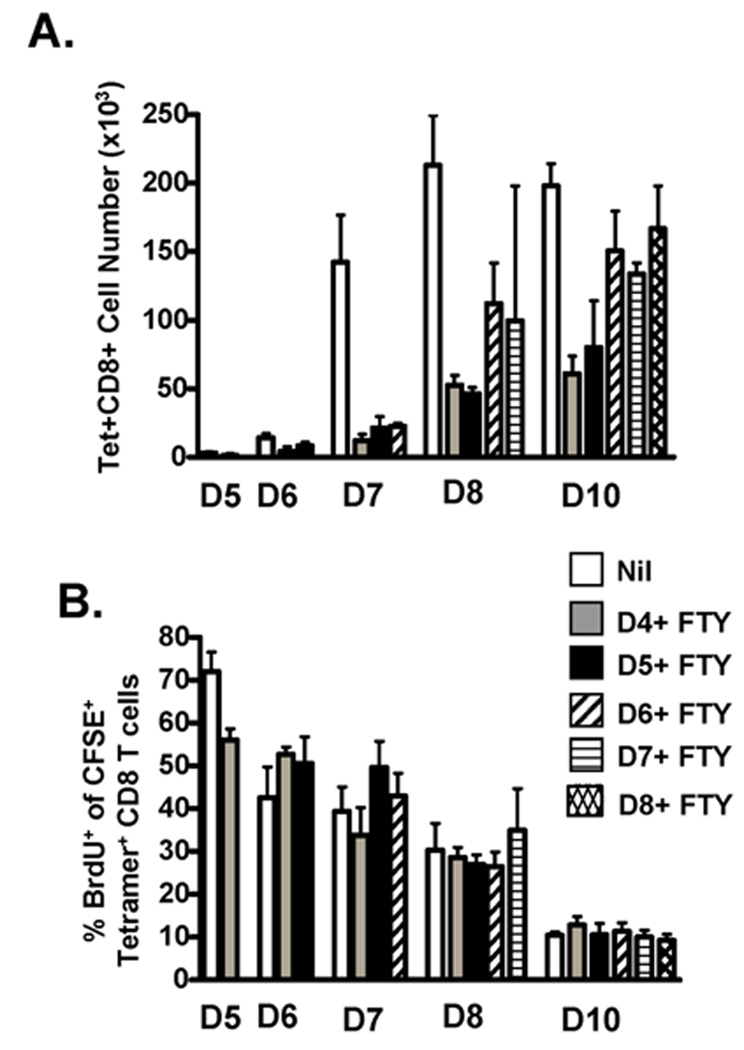

Therefore, we went on to utilize FTY720 administration to assess the role of virus-specific CD8 T cell proliferation within the lungs independent of new cell recruitment. Mice were infected with a sublethal dose of influenza virus and FTY720 administration was initiated on days 4, 5, 6, 7 or 8 p.i and then continued daily throughout the experiment. Pulmonary T cell proliferation was then determined on days 5, 6, 7, 8 and 10 by i.n. CFSE and i.n. BrdU administration, lung harvest, and flow cytometry as described above.

FTY720 treatment results in significantly decreased numbers of influenza-specific CD8 T cells in the lungs at the time of analysis when the drug administration is initiated on days 4+ or 5+ p.i. (Fig 2A). Although there is a dramatic reduction in the number of cells in the lungs of day 4+ (grey bars) and 5+ (black bars) FTY720-treated mice, we continue to see an expansion in the numbers of influenza virus-specific CD8 T cells throughout the course of infection, resulting in an approximately 10-fold increase from day 6 p.i. to day 10 p.i‥ Given that new recruitment of influenza-specific CD8 T cells is inhibited by the FTY720 treatment beginning on days 4 or 5 p.i. and the number of cells present is above that of mice blocked starting on day 2p.i. (supplemental Fig S4), these results suggest that proliferation by lung-resident CD8 T cells is contributing to this 10-fold expansion in pulmonary cell numbers observed out to day 10 p.i‥ Further, a similar percentage of influenza-specific CD8 T cells incorporate BrdU (Fig 2B) in FTY720-treated mice relative to untreated control mice (white bars), suggesting that the T cells are continuing to proliferate at the same rate despite the reduced numbers of CD8 T cells in the lungs following FTY720 treatment.

FIGURE 2.

Lung-resident CD8 T cell proliferation contributes to the overall magnitude of the virus-specific CD8 T cell response in the lungs. Influenza-infected mice were administered FTY720 i.p. daily starting on days 4 (grey bars), 5 (black bars), 6 (diagonal bars), 7 (horizontal bars) or 8 (hatched bars) p.i‥ Mice that did not receive FTY720 were included as controls (Nil, white bars). Groups were treated with CFSE-BrdU on days 5, 6, 7, 8 and 10 p.i. as shown in supplemental Figure 2A. 4 h later, the mice were sacrificed and their lungs examined by flow cytometry for: (A) cell numbers of influenza virus-specific tetramer+ CD8 T cells; and (B) frequencies of influenza virus-specific tetramer+ CD8 T cells that incorporated BrdU during the analysis. Data are representative of 2 separate experiments. n=3–5 mice/group.

In contrast to FTY720 treatment on days 4+ and 5+ p.i., FTY720 administration does not appear to have a substantial effect on the numbers of influenza-specific CD8 T cells in the lungs at the time of analysis if administered on days 6+ (diagonal lined bars), 7+ (horizontal lined bars) or 8+ (hatched bars) p.i. However, like the expansion observed by the day 4+ and 5+ p.i. treated lungs, when FTY720 is administered on days 6+, 7+ or 8+ p.i. to block new migration from the LN, CD8 T cell numbers continue to expand in the lungs through day 10 p.i‥ Like the day 4+ and 5+ FTY720-treated mice, those mice that were treated on days 6+, 7+ and 8+ p.i. have similar levels of BrdU incoporation as untreated controls throughout infection. Given that there is not a significant reduction in the cell numbers of day 6+, 7+, or 8+ p.i. FTY720-treated lungs relative to untreated lungs, the results suggest that enough influenza-specific CD8 T cells have migrated from the LN to the lungs by day 6 p.i., that lung-resident T cell proliferation is sufficient to sustain, independent of new cell recruitment, the high numbers of T cells found in the lungs at these later time points p.i‥

Together, the results suggest that influenza virus-specific CD8 T cells are proliferating very rapidly, likely at their maximal division rate within the lungs (12), particularly in the early stages of the virus-specific adaptive immune response (i.e. days 4 and 5 p.i.). At these early time points, because there are so few CD8 T cells that have arrived in the lungs to contribute to this lung-resident expansion, CD8 T cell migration from the LN to the lungs is essential in providing a new supply of activated virus-specific CD8 T cells, thus promoting the development of a normal magnitude response. In contrast, by the later stages of the virus-specific adaptive response (i.e. days 6, 7 and 8), sufficient numbers of antigen-specific CD8 T cells have arrived in the lungs, that when paired with additional lung-resident cell division, they can promote a CD8 T cell response of normal magnitude. Overall, this would suggest that while migration of CD8 T cells from the LN to the lungs is essential during the very early stages of infection (i.e. day 4 and 5 p.i.), this migration may not be required during the later stages of infection (i.e. day 6, 7 and 8). In fact, during these late stages, lung-resident CD8 T cell division may play the largest role in determining the overall magnitude of the pulmonary virus-specific CD8 T cell response.

It is known that activated CD8 T cells responding to antigen stimulus can proliferate very rapidly in vivo (5, 12, 13). A recent paper by Yoon et al. has suggested that in vivo proliferation of antigen-specific CD8 T cells following influenza virus infection occurs more rapidly that initially estimated, with a doubling time as short as 4 hours in the LN during the early stages of infection (12). These results correspond well with our analysis, given that as many as 70% of antigen-specific CD8 T cells incorporated BrdU within a 4 hour window (Fig 2 and Fig S3).

The dual-label CFSE and BrdU technique can successfully identify CD8 T cells that have undergone at least one round of division within the lungs during influenza virus infection. However, it remains difficult to estimate the number of divisions the influenza-specific CD8 T cells are undergoing once in the lungs. The cells have undergone several divisions within the LN prior to migrating to the lungs and may be simply completing their activation and division program once arriving in the lungs; if this is the case, this technique allows us to identify those cells that are just “finishing up” the program. However our results in Fig 2 for day 4+ and 5+ treatments suggest that one or two final programmed cell divisions are not sufficient to account for the expansion of T cells from days 5➔ 10 p.i‥ Therefore, it is likely that the CD8 T cells are actively undergoing multiple rounds of division during their residence in the lungs.

Whereas we have demonstrated that influenza-specific CD8 T cells continue to proliferate once migrating into the lungs, the mechanisms that promote this continued proliferation remain unclear. However, intriguingly we have recently demonstrated that, during primary influenza virus infections, virus-specific CD8 T cells undergo primary activation by DC in the draining LN and then require a subsequent second interaction with antigen bearing DC in the lungs in order to accumulate to sufficient numbers to promote viral clearance (17).

It has been well accepted that influenza-specific CD8 T cells are primed in the lung-draining LN following influenza virus infection where they then undergo multiple rounds of division. Until recently, however, it has remained unclear whether the majority of CD8 T cell division occurs within the LN prior to migration into the lungs, or if the influenza-specific CD8 T cells continue to proliferate once arriving at the site of infection. Here, we have developed a novel in vivo CFSE-BrdU dual labeling system that allows us to identify influenza virus-specific CD8 T cells that have migrated from the LN to the lungs and have undergone at least one round of division within the lungs. With this approach, we have demonstrated that a high ratio of influenza virus-specific CD8 T cells are undergoing division while in the lungs and that lung-resident CD8 T cell division plays a significant role in promoting the development of normal CD8 T cell responses in the lungs following influenza virus infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Jon Heusel and Steve Varga for critical reading of this manuscript.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- LN

lymph nodes

- RSV

respiratory syncytial virus

- p.i.

post infection

- NP

influenza nucleocapsid protein

- HA

influenza hemagglutinin protein

- CFSE

Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH AI-071085 AI-076989 and Department of Pathology Start-Up Funds to K.L.L.

“This is an author-produced version of a manuscript accepted for publication in The Journal of Immunology (The JI). The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. (AAI), publisher of The JI, holds the copyright to this manuscript. This manuscript has not yet been copyedited or subjected to editorial proofreading by The JI; hence it may differ from the final version published in The JI (online and in print). AAI (The JI) is not liable for errors or omissions in this author-produced version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by the United States National Institutes of Health or any other third party. The final, citable version of record can be found at www.jimmunol.org.”

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Legge KL, Braciale TJ. Accelerated migration of respiratory dendritic cells to the regional lymph nodes is limited to the early phase of pulmonary infection. Immunity. 2003;18:265–277. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belz GT, Smith CM, Kleinert L, Reading P, Brooks A, Shortman K, Carbone FR, Heath WR. Distinct migrating and nonmigrating dendritic cell populations are involved in MHC class I-restricted antigen presentation after lung infection with virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:8670–8675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402644101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.GeurtsvanKessel CH, Willart MA, van Rijt LS, Muskens F, Kool M, Baas C, Thielemans K, Bennett C, Clausen BE, Hoogsteden HC, Osterhaus AD, Rimmelzwaan GF, Lambrecht BN. Clearance of influenza virus from the lung depends on migratory langerin+CD11b- but not plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:1621–1634. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim TS, Braciale TJ. PLoS ONE. Vol. 4. 2009. Respiratory dendritic cell subsets differ in their capacity to support the induction of virus-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cell responses; p. e4204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrence CW, Braciale TJ. Activation, differentiation, and migration of naive virus-specific CD8+ T cells during pulmonary influenza virus infection. J. Immunol. 2004;173:1209–1218. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawrence CW, Ream RM, Braciale TJ. Frequency, specificity, and sites of expansion of CD8+ T cells during primary pulmonary influenza virus infection. J. Immunol. 2005;174:5332–5340. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wissinger EL, Stevens WW, Varga SM, Braciale TJ. Proliferative expansion and acquisition of effector activity by memory CD4+ T cells in the lungs following pulmonary virus infection. J. Immunol. 2008;180:2957–2966. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Legge KL, Braciale TJ. Lymph node dendritic cells control CD8+ T cell responses through regulated FasL expression. Immunity. 2005;23:649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofmann M, Brinkmann V, Zerwes HG. FTY720 preferentially depletes naive T cells from peripheral and lymphoid organs. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1902–1910. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cose S, Brammer C, Khanna KM, Masopust D, Lefrancois L. Evidence that a significant number of naive T cells enter non-lymphoid organs as part of a normal migratory pathway. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006;36:1423–1433. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGill J, Legge KL. Continued proliferation of influenza-specific T cells in the lungs during the early stages of influenza virus infections. Options for the Control of Influenza. 2008;VI:162. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon H, Legge KL, Sung SS, Braciale TJ. Sequential activation of CD8+ T cells in the draining lymph nodes in response to pulmonary virus infection. J. Immunol. 2007;179:391–399. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller MJ, Safrina O, Parker I, Cahalan MD. Imaging the single cell dynamics of CD4+ T cell activation by dendritic cells in lymph nodes. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:847–856. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGill J, Van Rooijen N, Legge KL. Protective influenza-specific CD8 T cell responses require interactions with dendritic cells in the lungs. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:1635–1646. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.