Abstract

Enzymes participating in different metabolic pathways often have similar catalytic mechanisms and structures, suggesting their evolution from a common ancestral precursor enzyme. We sought to create a precursor-like enzyme for N′-[(5′-phosphoribosyl)formimino]-5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (ProFAR) isomerase (HisA; EC 5.3.1.16) and phosphoribosylanthranilate (PRA) isomerase (TrpF; EC 5.3.1.24), which catalyze similar reactions in the biosynthesis of the amino acids histidine and tryptophan and have a similar (βα)8-barrel structure. Using random mutagenesis and selection, we generated several HisA variants that catalyze the TrpF reaction both in vivo and in vitro, and one of these variants retained significant HisA activity. A more detailed analysis revealed that a single amino acid exchange could establish TrpF activity on the HisA scaffold. These findings suggest that HisA and TrpF may have evolved from an ancestral enzyme of broader substrate specificity and underscore that (βα)8-barrel enzymes are very suitable for the design of new catalytic activities.

Enzymes of contemporary metabolic pathways are generally specific and efficient biocatalysts. They can be categorized into a limited number of families, the members of which share similar reaction mechanisms, folds, or both (1). This leads to the idea that the members of a given enzyme family are evolutionarily related. In principle, two different evolutionary scenarios can be envisioned. New catalytic functions of enzymes could have evolved by changing the chemistry of catalysis, while retaining the binding capacity for a common ligand. This idea of retrograde evolution (2) was recently supported by the successful interconversion of the catalytic activity of two enzymes from tryptophan biosynthesis, which catalyze successive reactions in the pathway and therefore bind the same ligand (3). Alternatively, new catalytic functions could have evolved by retaining the chemistry of catalysis, while changing the substrate specificity (1). Along these lines, the patchwork model of enzyme evolution (4) postulates that ancestral enzymes were relatively unspecific and therefore were capable of catalyzing chemically similar reactions in different metabolic pathways. Genes encoding these enzymes would have duplicated in the course of evolution and would have subsequently specialized by diversification.

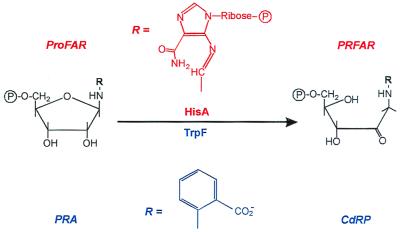

N′-[(5′-Phosphoribosyl)formimino]-5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (ProFAR) isomerase (HisA; EC 5.3.1.16) and phosphoribosylanthranilate (PRA) isomerase (TrpF; EC 5.3.1.24) constitute a pair of similar enzymes, which are involved in the biosynthesis of the amino acids histidine and tryptophan, respectively (5, 6). Both HisA and TrpF catalyze an Amadori rearrangement, which is the irreversible isomerization of an aminoaldose to an aminoketose (Fig. 1). Also, despite the lack of detectable amino acid sequence similarity, HisA and TrpF belong to the same structural family of (βα)8-barrels (7, 8), which is the most frequent fold among single-domain proteins (9). (βα)8-Barrel proteins consist of eight repeating units of βα modules. The eight β-strands form an inner parallel β-sheet, which is surrounded by the eight α-helices. Almost all known (βα)8-barrel proteins are enzymes, and their active sites are always located at the C termini of the β-strands or in the loops that connect β-strands with the following α-helices.

Figure 1.

HisA and TrpF catalyze similar reactions in histidine and tryptophan biosynthesis. HisA and TrpF catalyze the isomerizations of the aminoaldoses N′-[(5′-phosphoribosyl)formimino]-5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (ProFAR) and phosphoribosylanthranilate (PRA) to the aminoketoses N′-[(5′-phosphoribulosyl)formimino]-5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (PRFAR) and 1-(o-carboxyphenylamino)-1-deoxyribulose 5-phosphate (CdRP).

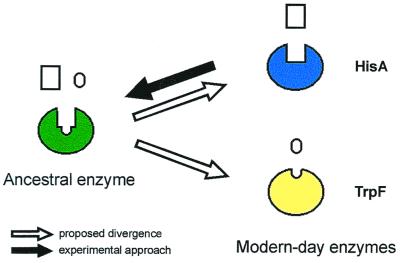

These striking functional and structural similarities suggest that HisA and TrpF may have evolved from one common ancestral enzyme with low substrate specificity (4). We wished to reverse this process by creating an enzyme that is capable of catalyzing both the HisA and the TrpF reactions (Fig. 2), using random mutagenesis and selection in vivo. Because ProFAR is considerably larger than PRA (Fig. 1), we assumed that HisA might bind and convert the substrate of TrpF more easily than vice versa. For this reason, and because we wished to work with a stable protein, HisA from the hyperthermophile Thermotoga maritima (tHisA; ref. 10) was chosen as the scaffold on which TrpF activity should be established.

Figure 2.

Experimental approach for testing the patchwork hypothesis (4) of enzyme evolution. Modern-day enzymes such as HisA and TrpF are highly specific catalysts that may have evolved from a common ancestor enzyme that was less specific. Starting from HisA, we tried to reverse the postulated evolutionary path, creating an enzyme capable of catalyzing both the HisA and the TrpF reaction.

Materials and Methods

Generation of a Plasmid Library of thisA Genes and Selection of Variants with TrpF Activity.

thisA was amplified by PCR in the presence of 2 mM MgCl2 with Taq DNA polymerase, using the plasmid pDS56/RBSII/thisA as the template (10), and the oligonucleotides CyRI (5′-TCA CGA GGC CCT TTC GTC TT-3′) and CyPstI (5′-TCG CCA AGC TAG CTT GGA TTC T-3′) as 5′- and 3′-primers, respectively. The following amplification conditions were applied: step 1, 95°C, 2 min; step 2, 95°C, 45 s; step 3, 50°C, 45 s; step 4, 72°C, 30 s; step 5, 72°C, 2 min; steps 2 to 4 were repeated 30 times. The amplified DNA was digested with 0.17 unit of DNase I at 37°C for 5 min. Fragments of 50–150 bp were isolated by extraction from an agarose gel, purified, and reassembled without added primers in the presence of 2 mM MgCl2. The following program was used: step 1, 95°C, 2 min; step 2, 95°C, 30 s; step 3, 55°C, 30 s; step 4, 72°C, 25 s; step 5, 95°C, 30 s; step 6, 55°C, 30 s; step 7, 72°C, 30 s; step 8, 72°C, 5 min; steps 2 to 4 and steps 5 to 7 were repeated 20 times. A final PCR was performed with Taq DNA polymerase, using the reassembled fragments as template and CyRI and CyPstI as primers. The following amplification conditions were applied: step 1, 95°C, 2 min; step 2, 95°C, 30 s; step 3, 55°C, 30 s; step 4, 72°C, 30 s; step 5, 72°C, 5 min; steps 2 to 4 were repeated 35 times. The amplified fragments were purified and digested with SphI and HindIII, yielding mutagenized thisA fragments 731 bp long. These fragments were ligated into the pDS56/RBSII expression vector, which contains a modified T5 promoter that is regulated by the lac operator (11).

An Escherichia coli strain that lacks the trpF gene on its chromosome (JMB9 r− m+ ΔtrpF, designated ΔtrpF; ref. 12), and therefore cannot grow without addition of tryptophan, was transformed with the ligation mixture described above, plated on minimal VB (13) agar plates containing 0.5% Casamino acids (Difco), and incubated at 37°C. To ensure a high production level of the pDS56/RBSII-encoded tHisA variants in the absence of isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG), the transformed ΔtrpF cells did not contain the plasmid pDMI,1, which encodes the lac repressor and the kanamycin-resistance genes (11).

Expression and Purification of Selected tHisA Variants.

Heterologous expression of thisA_1 and thisA_2 cloned into the SphI and HindIII restriction sites of pDS56/RBSII was conducted in E. coli W3110 ΔtrpEA2 cells (14). The host cells also contained the repressor plasmid pDMI,1. Cells transformed with the corresponding pDS56/RBSII plasmid variant were grown in 1 liter of LB medium containing ampicillin and kanamycin until OD600 reached a value of about 0.5–0.6. Subsequently, expression of thisA_1 or thisA_2 was induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG. Washing, resuspension, and lysis of harvested cells were performed essentially as described for wild-type tHisA (10). In a first purification step, the soluble fraction of the cell extract was incubated for 15 min at 75°C in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, containing 5 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT, so that thermolabile host proteins could be precipitated by centrifugation (23,400 × g, 40 min, 4°C). As shown by SDS/PAGE, about 80% of the host proteins were removed in this step. The supernatants with the thermostable tHisA variants were dialyzed against 50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.8, containing 1 mM DTT, and loaded on a Red Sepharose CL-6B column (2.5 × 16 cm; Amersham Pharmacia) that was equilibrated with the same buffer. Elution of bound proteins from the column was achieved with a linear gradient from 0 to 800 mM NaCl. The tHisA variants eluted at 450–620 mM NaCl and were more than 95% pure, as judged by SDS/PAGE. The yields were 5.9 mg of tHisA_1 and 4.3 mg of tHisA_2 per gram of wet cell mass. Concentration measurements of the tHisA variants were performed as described (10).

Production of tHisA Variants with Single Amino Acid Exchanges.

Five of the seven single mutation variants, tHisA_Asn24Asp, Arg97Gly, His175Tyr, His75Tyr, and Phe111Ser, were produced by site-directed mutagenesis, using the megaprimer method (15). For production of the variants tHisA_Asn24Asp, His75Tyr, Arg97Gly, and Phe111Ser, in the first PCR the oligonucleotide CyRI was used as 5′-primer, and the following oligonucleotides carrying the exchanged nucleotides (underlined) were used as 3′- primers: 5′-TAT GGT GTC CTC TTT TC-3′ (Asn24Asp), 5′-GAT CTG TAT GTA CTC GGC AAA-3′ (His75Tyr), 5′-CTG TCT TCC GTA TCC CA-3′ (Arg97Gly), and 5′-TCC ACA TCG ATT TCT CTC AGG GAT TTC AGG GAA GAA GGA TCT-3′ (Phe111Ser). In the second PCR, the resulting megaprimers were used as 5′-primers and the oligonucleotide CyPstI was used as 3′-primer. For the production of the mutant His175Tyr, in the first PCR the oligonucleotide 5′-CTT CAG GAG TAC GAT TTT TCT C-3′ carrying the exchanged nucleotide was used as 5′-primer, and the oligonucleotide CyPstI was used as 3′-primer. In the second PCR, CyRI was used as 5′-primer, and the megaprimer resulting from the first PCR was used as 3′-primer. For production of the variant Met236Ile, only a single PCR was necessary, using CyRI as 5′-primer and the oligonucleotide 5′-CTA ATT AAG CTT TTA GCG AGC ATA TCT CTT TAT CAC CTC AAC TG-3′ carrying the exchanged nucleotide as 3′-primer. All PCRs were performed with Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene) and a pDS56/RBSII/thisA plasmid with a modified promoter region (16) as the template. The following program was used: step 1, 95°C, 2 min; step 2, 95°C, 30 s; step 3, N°C, 30 s; step 4, 72°C, 1 min; step 5, 72°C, 10 min. The corresponding annealing temperatures N were calculated as described in ref. 17. The full-length PCR products with the thisA gene variants were cloned into pDS56/RBSII, using the SphI and HindIII restriction sites, and sequenced to show that only the planned nucleotide exchanges were introduced and that the remainder of the thisA gene was not changed by inadvertent PCR mutations. All single mutation variants were expressed in E. coli W3110 ΔtrpEA2 cells and purified as described above.

The variant tHisA_Asp127Val was produced by combining the 5′-region of the thisA wild-type gene and the 3′-region of the thisA_2 gene that carries the A380T exchange, leading to the Asp127Val amino acid substitution, and the silent nucleotide exchange T648C. To this end, the pDS56/RBSII/thisA and the pDS56/RBSII/thisA_2 plasmids were digested with Bsu15I and NcoI, yielding fragments of 1047 and 3039 bp. The 1047-bp fragment from pDS56/RBSII/thisA_2 was ligated with the 3039-bp fragment from pDS56/RBSII/thisA, yielding pDS56/RBSII/thisA_Asp127Val. DNA sequencing confirmed the expected nucleotide exchanges within the insert and excluded inadvertent mutations. Subsequently, thisA_Asp127Val was expressed in E. coli W3110 ΔtrpEA2 cells and purified as described above, yielding 4.9 mg of protein per gram of wet cell mass.

Steady-State Enzyme Kinetics.

Steady-state enzyme kinetics of the TrpF reaction was measured at 25°C by fluorescence spectroscopy according to ref. 18. Anthranilic acid was first converted into an equal amount of PRA by 0.7 μM anthranilate phosphoribosyltransferase from yeast, using a large molar excess of phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP). This reaction was followed by a decrease of the fluorescence emission at 400 nm, after excitation at 350 nm. As soon as a constant fluorescence intensity was reached, enzyme was added. A further decrease of the fluorescence intensity indicated the conversion of PRA to CdRP. Due to the presence of 0.7 μM indoleglycerol-phosphate synthase from E. coli, CdRP was further converted into indoleglycerol phosphate, thus preventing product inhibition. Steady-state enzyme kinetics of the HisA reaction was measured at 25°C by absorption spectroscopy according to ref. 19. In the presence of an enzyme with HisA activity, ProFAR was first converted to PRFAR, and then further into imidazoleglycerol phosphate (ImGP) and aminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) by 1 μM ImGP synthase from T. maritima. Thus, product inhibition of the HisA reaction was prevented and the decrease of the absorbance at 300 nm was used to monitor the reaction [Δɛ300 (ProFAR − AICAR) = 5.637 mM−1⋅cm−1].

Results and Discussion

Selection in Vivo of tHisA Variants with TrpF Activity.

tHisA variants with acquired TrpF activity were identified by genetic complementation of an E. coli strain that lacks the trpF gene on its chromosome (ΔtrpF; ref. 12). This recipient was transformed with a plasmid library containing randomly mutagenized thisA genes that was generated by DNA shuffling (20), and the transformants were plated on selective medium lacking tryptophan and incubated at 37°C. Although the thisA gene in the plasmid is preceded by a tandem lac operator (11), its multiple copies override the inhibition of transcription of the endogenous lac repressor. From the three colonies that appeared after several days, plasmid DNA was isolated. As a control, fresh recipient cells were transformed with these plasmids. Moreover, the corresponding thisA inserts were recloned into fresh plasmid. The resulting transformants grew on selective medium, whereas the recipient of a plasmid containing wild-type thisA did not (negative control). These results prove that mutations introduced into the thisA gene had resulted in tHisA variants with the ability to complement ΔtrpF cells. DNA sequencing of the three isolated mutant thisA genes revealed that two of them were identical. Those were termed thisA_1 and carried the following four nucleotide (amino acid) exchanges: A70G (Asn24Asp), A289G (Arg97Gly), C523T (His175Tyr), and G708A (Met236Ile). The third variant, thisA_2, carried the three nucleotide (amino acid) exchanges C223T (His75Tyr), T332C (Phe111Ser), and A380T (Asp127Val). It additionally contained the two silent nucleotide exchanges C234T and T648C.

Production of Selected tHisA Variants and Activity Measurements in Vitro.

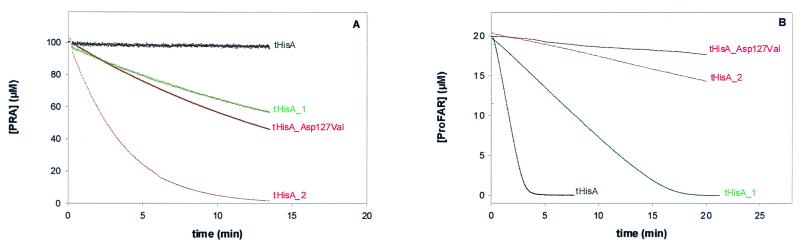

To measure the newly acquired TrpF activity in vitro, tHisA_1, tHisA_2, and wild-type tHisA were overexpressed in E. coli W3110 ΔtrpEA2 cells, which lack the entire tryptophan operon on their chromosome (14). These cells were chosen to avoid any contamination of the tHisA variants with intrinsic TrpF from E. coli. The tHisA variants were purified by the procedure developed for the wild type, which involves heat denaturation of the soluble host cell proteins and affinity chromatography on Red Sepharose (10). Since the yields of the purified variant proteins were comparable to those obtained with the wild type, the amino acid substitutions of tHisA_1 and tHisA_2 do not significantly impair the thermostability of the tHisA scaffold. The catalytic efficiency of the variants was determined by steady-state enzyme kinetics, using the decrease of fluorescence intensity at 400 nm upon conversion of PRA into CdRP (18). Fig. 3A shows that both tHisA_1 and tHisA_2 have significant TrpF activity, in contrast to wild-type tHisA.

Figure 3.

TrpF (A) and HisA (B) activities of tHisA variants. (A) The TrpF reaction was monitored essentially as described (18). Each variant (21 μM) was incubated with 100 μM in situ synthesized PRA in the presence of 0.7 μM indoleglycerol-phosphate synthase from E. coli. The buffer conditions were 50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5 at 25°C, containing 4 mM MgEDTA and 2 mM DTT. (B) The HisA reaction was monitored essentially as described (19). Each variant, 0.25 μM tHisA, 0.5 μM tHisA_1, 21 μM tHisA_2, or 21 μM tHisA_Asp127Val, was incubated with 20 μM enzymatically synthesized ProFAR (22) in the presence of 1 μM ImGP synthase from T. maritima and of 5 mM glutamine. The buffer conditions were 50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5 at 25°C, containing 2 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT.

Which minimal modification of the sequence is sufficient for the acquisition of TrpF activity by tHisA? We approached this question by producing variants corresponding to each of the seven single amino acid substitutions found in tHisA_1 and tHisA_2, using site-directed mutagenesis. These variants were overexpressed and purified as described above, giving similar yields. Only the variant tHisA_Asp127Val from tHisA_2 showed significant TrpF activity (Fig. 3A), whereas the other ones were inactive (data not shown). Detailed steady-state kinetic studies can reveal which of the kinetic constants kcat and Km was the selected trait of particular variants (16). We therefore measured the rates of the TrpF reaction as a function of PRA concentration for tHisA_1, tHisA_2, and tHisA_Asp127Val. For all variants, a linear dependence of the initial velocities vi on the PRA concentration (between 0 and 100 μM PRA for tHisA_1, and between 0 and 10 μM PRA for tHisA_2 and tHisA_Asp127Val) was observed (data not shown). Because the initial slope of the vi versus [PRA] plot is identical to Vmax/KmPRA, the catalytic efficiency parameters kcat/KmPRA of tHisA_1, tHisA_2, and tHisA_Asp127Val can be calculated (Table 1), using the known total enzyme concentration ([E0]) and the relationship kcat = Vmax/[E0]. Furthermore, from the given values of kcat/KmPRA and because the initial slopes of saturation plots are linear only to the limit of [PRA] < 0.1 KmPRA, minimal values for kcat and KmPRA could be determined (Table 1). The KmPRA values of the mutant enzymes are several orders of magnitude larger than that of tTrpF, whereas their kcat values amount to at least 1% that of tTrpF. In the absence of tryptophan, the trp operon is derepressed in trp− mutants of E. coli, leading to the accumulation of the substrate of the corresponding gene product. Considering the likely accumulation of PRA in the case of the ΔtrpF host used in this work for selection purposes, small values of KmPRA of the tHisA variants seem to be not as crucial for cell growth as increased values of kcat. Put differently, kcat is probably the selected trait in our experiments (16).

Table 1.

Steady-state kinetic parameters of selected tHisA variants compared with wild-type enzymes tHisA and tTrpF

| Enzyme | TrpF reaction

|

HisA reaction

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat, s−1 | KmPRA, mM | kcat/KmPRA, mM−1⋅s−1 | kcat, s−1 | KmProFAR, μM | kcat/KmProFAR, μM−1⋅s−1 | |

| tHisA | 0 | ND | ND | 0.70 | 0.60 | 1.2 |

| tHisA_1* | >0.046 | >1.0 | 0.046 | 0.061 | 1.32 | 0.046 |

| tHisA_2* | >0.049 | >0.1 | 0.49 | ≈2⋅10−4 | ND | ND |

| tHisA_Asp127 Val* | >0.012 | >0.1 | 0.12 | ≈1⋅10−4 | ND | ND |

| tTrpF† | 3.7 | 2.8⋅10−4 | 13.3⋅103 | 0 | ND | ND |

Buffer conditions: 50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5 at 25°C, containing 4 mM MgEDTA and 2 mM DTT (TrpF reaction), or 2 mM NaEDTA and 1 mM DTT (HisA reaction). ND, because of the very low kcat value, Km and therefore also kcat/Km could not be determined.

Only minimal values for kcat and KmPRA could be determined, because KmPRA is at least 10 times as high as the maximally applied substrate concentrations.

Data from ref. 21.

The question is whether the acquired TrpF activities of tHisA_1, tHisA_2, and tHisA_Asp127Val are at the expense of their original HisA activity. Therefore, the HisA activity was measured with a coupled spectrophotometric assay, using ImGP synthase as a helper enzyme (19). ProFAR and glutamine are thus converted to ImGP and aminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR), and product inhibition of HisA by PRFAR is avoided. Fig. 3B shows that the reaction is catalyzed rapidly by tHisA (0.25 μM) and more slowly by tHisA_1 (0.5 μM). These progress curves were analyzed with the integrated form of the Michaelis–Menten equation (18), yielding the values for kcat and KmProFAR. In contrast, addition even of high concentrations (21 μM) of tHisA_2 or tHisA_Asp127Val to 20 μM ProFAR resulted in the conversion of only a small fraction of the substrate into product (Fig. 3B). The deduced kcat values show that tHisA_2 and tHisA_Asp127Val have lost almost all HisA activity (Table 1).

Structural Basis of the TrpF Activity of tHisA_1, tHisA_2, and tHisA_Asp127Val.

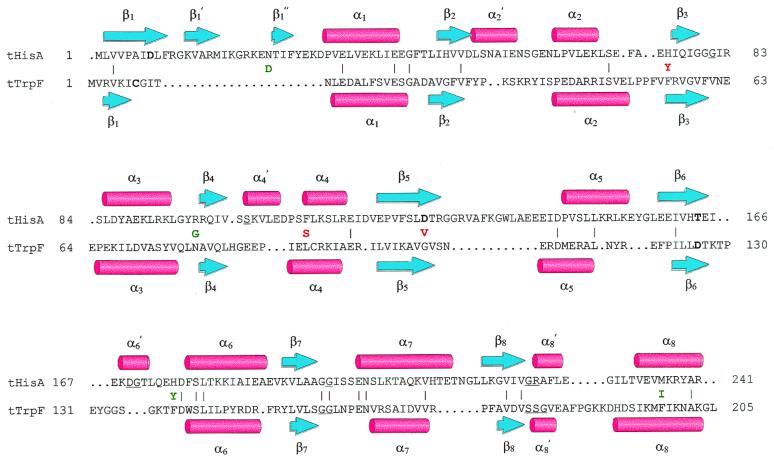

Can we understand the acquisition of TrpF activity by tHisA variants on a structural basis? Fig. 4 shows a structure-based amino acid sequence alignment of tHisA and tTrpF. Whereas tTrpF is an almost perfect canonical (βα)8-barrel, tHisA bears a number of extra secondary structural elements. Nevertheless, both the β-strands of the central barrels and the individual α-helices of tHisA and tTrpF superimpose well, although the amino acid sequence identity is only about 10%. In addition, two of the catalytically important residues are located at equivalent positions in β-strand 1 (Asp-8 in tHisA and Cys-7 in tTrpF) and in β-strand 6 (Thr-164 in tHisA and Asp-126 in tTrpF), as are residues that bind the phosphate moieties of the substrates between β-strand 7 and α-helix 8′. A similar “structural conservation” of catalytically essential residues has been found for several members from the superfamily of enolases, which comprises (βα)8-barrel enzymes that catalyze the abstraction of the α-proton from a carboxylic acid (26).

Figure 4.

Structure-based amino acid sequence alignment of tHisA and tTrpF. The backbone atoms from the x-ray structures of tHisA (8) and tTrpF (23) were superimposed with an rms deviation of 2.2 Å (24). β-Strands are represented by blue arrows, α-helices by red cylinders. Identical residues (10%) between tHisA and tTrpF are indicated by (|). Catalytically important residues of wild-type tHisA (Asp-8, Asp-127, and Thr-164; S. Schmidt, M. Henn-Sax, and R.S., unpublished data) and of wild-type tTrpF (Cys-7 and Asp-126; ref. 25) are in boldface. Residues involved in binding of the single phosphate moiety of PRA and of the two phosphate moieties of ProFAR are underlined. For tHisA, these residues were identified by a structure-based sequence alignment with the related tHisF protein, whose x-ray structure showed two phosphate ions bound to the active site (8). The acquired amino acids of tHisA_1 (green) and tHisA_2 (red) are given between the tHisA and the tTrpF sequences.

From the four new amino acids in tHisA_1, only Asp-24 and Tyr-175 are located at the C-terminal face of the central β-barrel and therefore lie close to the active site. Gly-97 and Ile-236, in contrast, are far from the active site and therefore act indirectly, if at all. In any case, several of the acquired amino acids must act in concert to establish the TrpF activity of tHisA_1, because all of its single mutation variants are inactive. In addition to the new TrpF activity, tHisA_1 has retained significant HisA activity (Fig. 3B; Table 1) and therefore represents a functional model for the postulated common ancestor of these two enzymes (Fig. 2).

Of the three amino acid exchanges in tHisA_2, only AspVal127 is located close to the active site (Fig. 4), and only this single substitution shows significant TrpF activity (Fig. 3A; Table 1). Asp-127 is a catalytically essential residue for the HisA reaction, as confirmed by the inactivity of tHisA_Asp127Val (Fig. 3B; Table 1). It is remarkable that a single amino acid exchange is sufficient to convert the specificity of an enzyme for substrates from different metabolic pathways. Val-127 in tHisA_Asp127Val is aligned with a glycine residue in tTrpF, which itself is surrounded by two valine residues. It is therefore tempting to assume that hydrophobicity in this region is crucial for enzymatic conversion of PRA instead of ProFAR.

Our findings show that not only protein folds (27) but also enzymatic specificity can be easily changed by a single amino acid exchange. This flexibility allows rapid structural and functional adaptation of proteins in the presence of selective pressure. That such adaptations do actually occur during natural evolution is suggested by experiments performed with EbgA, an E. coli protein with unknown natural function. Under selective pressure, the ebgA gene acquires two mutations that turn EbgA into a functional β-galactosidase, enabling growth on lactose of E. coli strains lacking lacZ (28).

In conclusion, the finding that the substrate specificity of two enzymes from different metabolic pathways can be interconverted with relative simplicity in a single round of random mutagenesis and selection supports their common ancestry from an ancestral enzyme of broader substrate specificity (Fig. 2). However, alternative scenarios cannot be excluded—for example, the evolution of TrpF from HisA. Along these lines, the tHisA structure shows an internal twofold repeat, which is not readily detectable in tTrpF and which might be an ancient characteristic of (βα)8-barrel enzymes (Fig. 4; ref. 8).

Because HisA and TrpF use the same protein fold to perform analogous reactions on different substrates (Fig. 1), our results suggest that a reaction mechanism can be conserved during the evolution of new catalytic functions (1). They also underscore the power of directed evolution techniques, given the existence of an efficient selection or screening system and a suitable scaffold such as the (βα)8-barrel (29, 30).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Hans-Joachim Fritz, Kasper Kirschner, and Charles Yanofsky for support and helpful comments on the manuscript, as well as Dr. V. Jo Davisson and Silke Beismann-Driemeyer for the gift of the phisGIE-tac plasmid and of imidazoleglycerol phosphate synthase from T. maritima, respectively. Financial support was received from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Grants STE 891/2-1, 2-2, and a Heisenberg Fellowship to R.S.).

Abbreviations

- HisA

N′-[(5′-phosphoribosyl)formimino]-5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (ProFAR) isomerase

- PRFAR

N′-[(5′-phosphoribulosyl)formimino]-5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide

- CdRP

1-(o-carboxyphenylamino)-1-deoxyribulose 5-phosphate

- ImGP

imidazoleglycerol phosphate

- tHisA

HisA from Thermotoga maritima

- TrpF

phosphoribosylanthranilate (PRA) isomerase

- tTrpF

TrpF from T. maritima

Footnotes

Article published online before print: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.160255397.

Article and publication date are at www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.160255397

References

- 1.Gerlt J A, Babbitt P C. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1998;2:607–612. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(98)80091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horowitz N H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1945;31:153–157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.31.6.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altamirano M M, Blackburn J M, Aguayo C, Fersht A R. Nature (London) 2000;403:617–622. doi: 10.1038/35001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen R A. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1976;30:409–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.30.100176.002205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winkler M E. In: Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. 2nd Ed. Neidhardt F C, Ingraham J L, Low K B, Magasanik B, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 1996. pp. 485–505. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yanofsky C, Miles E W, Bauerle R, Kirschner K. In: The Encyclopedia of Molecular Biology. Creighton T E, editor. Vol. 4. New York: Wiley; 1999. pp. 2676–2689. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Priestle J P, Grütter M G, White J L, Vincent M G, Kania M, Wilson E, Jardetzky T S, Kirschner K, Jansonius J N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5690–5694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lang, D., Thoma, R., Henn-Sax, M., Sterner, R. & Wilmanns, M. (2000) Science, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Hegyi H, Gerstein M. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:147–164. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thoma R, Obmolova G, Lang D A, Schwander M, Jenö P, Sterner R, Wilmanns M. FEBS Lett. 1999;454:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00757-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stüber D, Matile H, Garotta G. In: Immunological Methods. Lefkovits I, Pernis B, editors. Vol. 4. Orlando, FL: Academic; 1990. pp. 121–152. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sterner R, Dahm A, Darimont B, Ivens A, Liebl W, Kirschner K. EMBO J. 1995;14:4395–4402. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vogel H J, Bonner D M. J Biol Chem. 1956;218:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider W P, Nichols B P, Yanofsky C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:2169–2173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.4.2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarkar G, Sommer S S. BioTechniques. 1990;8:404–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merz A, Yee M C, Szadkowski H, Pappenberger G, Stemmer W P C, Yanofsky C, Kirschner K. Biochemistry. 2000;39:880–889. doi: 10.1021/bi992333i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chester N, Marshak D R. Anal Biochem. 1993;209:284–290. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hommel U, Eberhard M, Kirschner K. Biochemistry. 1995;34:5429–5439. doi: 10.1021/bi00016a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klem T J, Davisson V J. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5177–5186. doi: 10.1021/bi00070a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stemmer W P C. Nature (London) 1994;370:389–391. doi: 10.1038/370389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sterner R, Kleemann G R, Szadkowski H, Lustig A, Hennig M, Kirschner K. Protein Sci. 1996;5:2000–2008. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davisson V J, Deras I L, Hamilton S E, Moore L L. J Org Chem. 1994;59:137–143. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hennig M, Sterner R, Kirscher K, Jansonius J N. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6009–6016. doi: 10.1021/bi962718q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen G E. J Appl Crystallogr. 1997;30:1160–1161. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thoma R. Ph.D. thesis. Switzerland: Univ. of Basel; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasson M S, Schlichting I, Moulai J, Taylor K, Barrett W, Kenyon G L, Babbitt P C, Gerlt J A, Petsko G A, Ringe D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10396–10401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cordes M H J, Walsh N P, McKnight C J, Sauer R T. Science. 1999;284:325–327. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall B G. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arnold F H, Volkov A A. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1999;3:54–59. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(99)80010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petsko G A. Nature (London) 2000;403:606–607. doi: 10.1038/35001176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]