Abstract

Background

Generally, urinary 11-nor-9-carboxy-Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THCCOOH) after alkaline hydrolysis is monitored to detect cannabis exposure, although last use may have been weeks prior in chronic cannabis users. Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and 11-hydroxy-THC (11-OH-THC) concentrations in urine following E. coli β-glucuronidase hydrolysis were proposed as biomarkers of recent (within 8 h) cannabis use.

Objective

To test the validity of THC and 11-OH-THC in urine as indicators of recent cannabis use.

Methods

Monitor urinary cannabinoid excretion in 33 chronic cannabis smokers who resided on a secure research unit under 24 h continuous medical surveillance. All urine specimens were collected individually ad libidum for up to 30 days, were hydrolyzed with a tandem E. coli β-glucuronidase/base procedure, and analyzed for THC, 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH by 1- and 2-dimensional-cryotrap gas chromatography mass spectrometry (2D-GCMS) with limits of quantification of 2.5 ng/mL.

Results

Extended excretion of THC and 11-OH-THC in chronic cannabis users’ urine was observed during monitored abstinence; 14 of 33 participants had measurable THC in specimens collected at least 24 h after abstinence initiation. Seven subjects had measurable THC in urine for 3, 3, 4, 7, 7, 12, and 24 days after cannabis cessation. 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH were detectable in urine specimens from one heavy, chronic cannabis user for at least 24 days.

Conclusion

For the first time, extended urinary excretion of THC and 11-OH-THC is documented for at least 24 days, negating their effectiveness as biomarkers of recent cannabis exposure, and substantiating long terminal elimination times for urinary cannabinoids following chronic cannabis smoking.

Keywords: Tetrahydrocannabinol, Urine, Cannabinoids, Cannabis, THC, Chronic cannabis use

1. INTRODUCTION

Cannabinoid detection times in urine depend upon pharmacological factors (e.g., drug dose, route of administration, duration and frequency of use, smoking topography and individual rates of absorption, metabolism and excretion), and methodological issues including analytes evaluated, matrix, type of hydrolysis, cut-off or threshold used, and sensitivity of the method. The primary psychoactive constituent of cannabis, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), is rapidly absorbed during smoking, and due to its high lipophilicity is widely distributed to adipose tissue, liver, lung, and spleen. Body stores of THC increase with increasing frequency and chronicity of cannabis use. THC is rapidly metabolized to the equally psychoactive 11-hydroxy-THC (11-OH-THC), and to the inactive 11-nor-9-carboxy-THC (THCCOOH) metabolite and its glucuronide and sulfate conjugates (Huestis and Smith, 2005). The slow release of THC from fat back into blood was demonstrated to be the rate limiting step in cannabinoid elimination from the body (Hunt and Jones, 1980). Thus, THC was shown to have a long terminal elimination half-life in blood from chronic cannabis users (Johansson et al., 1989a).

Urine testing remains the most common means of drug monitoring in the United States. The highest numbers of positive urine drug tests in workplace drug testing are for cannabinoids, achieved by immunoassay screening and THCCOOH quantification in urine after alkaline hydrolysis. Urinary THCCOOH excretion patterns have been extensively studied (Smith-Kielland et al., 1999; Huestis et al., 1995; Johansson et al., 1990; Musshoff and Madea, 2006). After occasional use, Huestis et al reported THCCOOH concentrations above 15 ng/mL by gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GCMS) after alkaline hydrolysis for up to 4 days (Huestis et al., 1996; Huestis and Cone, 1998a). Urinary THCCOOH window of detection ranges from several days in infrequent users (Huestis and Cone, 1998b) to months in frequent users (Ellis et al., 1985; Peat, 1989; Kelly and Jones, 1992; Fraser and Worth, 2003; Johansson et al, 1989b). Thus, identification of THCCOOH in urine may not indicate recent cannabis exposure (Dackis et al., 1982; McBurney et al., 1986; Fraser and Worth, 2004).

Huestis and Cone developed and validated a model to differentiate new cannabis use from residual drug excretion in occasional cannabis users based on urine THCCOOH concentrations (Huestis and Cone, 1998b). However, this model may not be accurate in chronic cannabis users during the terminal elimination phase, when THCCOOH concentrations are low, below 20–50 ng/mL. In a search for new biomarkers of recent cannabis use, Kemp et al showed that THC and 11-OH-THC could be detected in urine after cannabis smoking if Escherichia coli (E. coli) β-glucuronidase hydrolysis was employed to break ether glucuronide bonds (Kemp et al., 1995a). They conducted a controlled cannabis smoking study quantifying THC and 11-OH-THC concentrations in urine specimens collected up to 8 h after cannabis smoking (Kemp et al, 1995b). The presence of THC or 11-OH-THC in urine was stated to indicate cannabis use within 8 h. In attempting to replicate this finding in our cannabinoid smoking studies, we quickly found that 11-OH-THC could be measured for many days after last smoked THC cigarette. Manno et al later revised their hypothesis to solely rely on the presence of THC in urine (> 1.5 ng/mL) to suggest cannabis use in the previous 8-h (Manno et al., 2001). We believed that this hypothesis required evaluation over a much longer timeframe and also, in individuals who were chronic cannabis users.

Cannabis, the most commonly abused drug world wide, is included in workplace, drug treatment, clinical, military and criminal justice drug testing programs. New drug use may have important consequences for employment, child custody, military status, and imprisonment. In treatment programs, urine drug testing is a deterrent to drug use, and is an effective and objective tool in contingency management programs and for evaluating new behavioral and pharmacotherapy treatments. The ability to differentiate new drug use from residual drug excretion would be valuable for clinicians, toxicologists, employee assistance programs, drug treatment providers, clinical trials of cannabis dependence treatment, anti-doping athletic programs, parole officers, attorneys and judges. The interpretation of cannabinoid urine tests would be greatly improved if new cannabis use could be identified in both occasional and chronic cannabis users.

Recent advances in analytical methods have improved sensitivity, specificity and recovery of cannabinoids in biological fluids and tissues. THC and 11-OH-THC are present in urine as glucuronide conjugates that are only effectively recovered following E. coli b-glucuronidase hydrolysis (Kemp et al., 1995a). We showed that to ensure comprehensive hydrolysis of all three cannabinoid conjugates, an initial hydrolysis with E. coli β-glucuronidase followed by a second hydrolysis with strong base (tandem hydrolysis), obtained better recovery of THCCOOH (Abraham et al., 2007). In addition, two-dimensional gas chromatography mass spectrometry (2D-GCMS) is a new technique (Lowe et al., 2007) that reduces background matrix interference allowing superior resolution and specificity, and achieving more reliable cannabinoid quantification at low concentrations. 2D-GCMS was utilized in this study to verify the.

The objective of the current research was to examine the time course of THC, 11-OH-THC, and THCCOOH elimination in urine in subjects with a history of chronic, heavy cannabis use, and to test the efficacy of THC and 11-OH-THC as urinary biomarkers of recent cannabis exposure. Participants resided on a secure clinical research unit, under 24 h medical surveillance, while participating in two studies of neurocognitive impairment in abstinent chronic heavy cannabis users. Subjects with the longest histories of cannabis smoking and highest THCCOOH concentrations on admission participated in the present cannabinoid urinary excretion study. Each urine specimen was individually collected throughout an abstinence period of up to 30 days and THC, 11-OH-THC, and THCCOOH concentrations were simultaneously quantified by one-dimensional GCMS. Because of the importance and controversial nature of the data, and availability of new analytical technology, THC, 11-OH-THC, and THCCOOH concentrations and times of last detection were verified by repeat analysis by 2D-GCMS, with low 2.5 ng/mL limits of quantification (LOQ) for each analyte. These are the first data on extended urinary THC, 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH excretion and detection times in chronic, heavy cannabis users, and the first to test the hypothesis that THC and 11-OH-THC in urine are biomarkers of recent cannabis use.

2. METHODS

2.1 PARTICIPANTS

Two clinical research studies at the Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Drug Abuse investigated neurocognitive impairment and effects of cannabis withdrawal in chronic cannabis users during 30 days of continuously monitored abstinence. Neurocognitive performance, fMRI and cerebral blood flow data from these studies have been previously reported (Bolla et al., 2002; Bolla et al., 2005; Bolla et al., 2008; Eldreth et al., 2004; Herning et al., 2003; Herning et al., 2005; Matochik et al., 2005). We recruited individuals with the most frequent and chronic self-reported cannabis use from January 2002 until July 2004 from these studies to participate in this secondary urinary cannabinoid excretion study. Males and females between 18–50 years of age, with cannabis dependence or abuse by DSM-IIIR criteria, and minimum cannabis use for the last two years were recruited. Participants were sequestered on a secure clinical research unit throughout to prevent access to cannabis and other drugs, and to enable collection of all urine voids. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse and participants provided written informed consent. There was no drug administration at any time during participation in the primary or secondary studies.

2.2 SPECIMENS

Every urine void was individually collected in a polypropylene bottle ad libidum from admittance to discharge from the clinical unit (up to 30 days) and immediately refrigerated. Total volume and specific gravity of each urine void was measured and aliquots of urine specimens were stored in 3.5 mL polypropylene screw-cap tubes and 30 mL polypropylene bottles at −20°C prior to analysis. Urine specimens were analyzed by 1D-GCMS within three years of frozen storage. Due to the surprising extended excretion of THC and 11-OH-THC for multiple days, and the low concentrations quantified, we reanalyzed some urine specimens by 2D-GCMS two to three years later in 2007–2008, when the technology became available in our laboratory. We utilized this new method to verify concentration and detection time data.

2.3 SPECIMEN PREPARATION

Tandem hydrolysis and extraction of urinary THC, 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH were performed according to a previously published procedure (Abraham et al., 2007). To ensure complete hydrolysis of conjugates and capture total analyte content, urine specimens (2 mL) were hydrolyzed by two methods in series. The initial 16 h hydrolysis with E. coli β-glucuronidase (Type IX-A) was followed by alkaline hydrolysis with 10N NaOH. Buffered hydrolysates (pH 4.0) were centrifuged and applied to preconditioned solid phase extraction (SPE) columns (Clean Screen® ZSTHC020 extraction columns, United Chemical Technologies). Concentrated extracts were derivatized with N,O-bis (trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) containing 1% trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS).

2.4 GCMS

Trimethylsilyl derivatives of THC, 11-OH-THC, and THCCOOH were initially quantified by 1D-GCMS on an Agilent 6890 GC/5973 MSD system. Capillary separation was achieved on a DB-35MS column (Agilent Technologies). The mass selective detector was operated in electron impact-selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode. Three ions for each analyte and two for each internal standard were acquired. Limit of quantification (LOQ) of the 1D-GCMS method was 2.5 ng/mL for all analytes. Decreasing concentrations of analytes were used to empirically determine limit of detection (LOD) and LOQ. LOD was defined as the lowest concentration with a signal to noise ratio ≥ 3:1 for target and qualifier ions, ion ratios within 20% of average qualifier ion ratios of calibrators, retention time within ± 2% and Gaussian peak shape. At the LOQ, all LOD criteria must be met, signal to noise ratio of the target ion is 10:1, and the calibrator must quantify within 20% of target concentration. With these definitions, it is possible for LOD to equal LOQ. LOQ of the 1D-GCMS method was 2.5 ng/mL for all analytes (Abraham et al., 2007). Method LOD was also established at 2.5 ng/mL due to inconsistent qualifier ion ratios at concentrations <2.5 ng/mL. THC, 11-OH-THC, and THCCOOH extraction efficiencies ranged from 57.0 – 59.3%, 68.3 – 75.5%, and 71.5 – 79.5%, respectively. Inter-assay imprecision ranged from 2.6 to 7.4% (% relative standard deviation) and analytical recovery was 101.1 to 113.7% for all analytes. Specific ions were as follows (quantitative ion underlined): THC 386, 371, 303; THC-d3 389, 374; 11-OH-THC 371, 474, 459; 11-OH-THC-d3 374, 477; THCCOOH 371, 488, 473; THCCOOH-d3 374, 491.

Due to the unexpected presence of THC and 11-OH-THC for extended periods of time, our laboratory developed a high selectivity 2D-GCMS assay for cannabinoids in urine to verify analyte identification and quantification. A subgroup of seven subjects (defined as the Persistent THC Group) with prolonged excretion of THC (≥ 2.5 ng/mL 72 h after cannabis cessation) was selected for repeat extraction and quantification of THC, 11-OH-THC, and THCCOOH by 2D-GCMS to determine last detection times. Verified last detection times were defined as after admission to the clinical unit. Actual detection times could be longer than those presented based on the times of last cannabis use prior to entry and initiation of 24 h continuous monitoring. All urine specimens from all participants collected in the first 72 h were tested. Urine specimens from the Persistent THC Group were tested until THC was no longer detectable (< 2.5 ng/mL) in three successive urine specimens.

The 2D-GCMS chromatographic method and parameters were adapted from a previously described method for determination of cannabinoids in plasma (Lowe et al., 2007). Primary and secondary capillary columns were DB-1MS (Agilent Technologies) and ZB-50 (Phenomenex). Three mL was introduced in splitless injection mode; following separation on the primary column, “cuts” of the analyte elution bands, were released to the secondary GC column for further resolution. The air-cooled cryogenic trap captured THC, 11-OH-THC, and THCCOOH entering the head of the secondary column and then ramped to 275°C to re-vaporize analytes The mass selective detector was operated in electron impact-selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode. Three ions for each analyte and two for each internal standard were acquired. Both LOD and LOQ were 2.5 ng/mL for THC, 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH. Analytical recovery ranged from 87.6% to 102.1% and intra-and inter-assay imprecision, as %RSD, was less than 8.6 % for all analytes (Lowe, Abraham et al., 2008).

3.0 RESULTS

A total of 1,271 urine specimens were analyzed by 1D-GCMS from 33 participants residing on the closed research unit during monitored abstinence for 3 to 30 days. All urine specimens from all participants individually collected during the first 72 h were quantified by 1D-GCMS to determine THC, 11-OH-THC, and THCCOOH elimination patterns. Demographic characteristics and self-reported drug use histories of the 33 participants are included in Table 1. Twenty-six subjects’ (13 M, 13 F, 21 African American, 2 White, 1 American Indian and 2 Unknown race) urine specimens were negative (< 2.5 ng/mL) within 72 h: 13 had no THC positive specimens after admission to the clinical unit; 6 participants’ urine specimens were negative by 24 h, and 7 more within 72 h. These participants had a mean ± SD age of 25.2 ± 4.5 years, weighed 173.1 ± 33.2 lbs with a mean body mass index (BMI) of 27.0 ± 5.3; 6 individuals were classified as obese with a BMI ≥30. These heavy, frequent cannabis users self-reported first cannabis use at 15.7 ± 2.8 years, and currently smoked an average of 3.7 ± 2.3 blunts/joints per day, on 12.5 ± 2.5 days in the last 14. A blunt is a hollowed out cigar filled with cannabis plant material. The THC detection data clearly documented that finding THC in the urine is not a biomarker of recent drug exposure. However, it was surprising to find that urine specimens from the other 7 participants (4 M, 3 F, all African American) were still THC positive ≥2.5 ng/mL 72 h after cannabis cessation. This group we defined as the Persistent THC Group. Urine specimens collected up to 30 days after last cannabis use were evaluated in this Group to characterize the duration of THC detection. Non-consecutive urine specimens were analyzed for the presence of THC. If a specimen was negative for THC, previous specimens were analyzed to pinpoint the time of last detection. The time of last THC detection was defined as the time of the last positive urine specimen prior to at least three consecutive negative specimens.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics and self-reported drug use histories for 33 heavy chronic cannabis users.

| Age | Ht. | Wt. | Drug of | Years | Cannabis use | Age of | Amount | Last | Other | Time on secure |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Gender | Race | (yr) | (in) | (lbs) | BMI | choice | used | Route | last 14 days | first use |

used/day | use | drugs | unit, days |

| A* | M | AA | 33 | 75 | 220 | 27.5 | Cannabis | 10 | Smoke | 7 | 15 | 1 blunt | Previous Day |

A | 12 |

| B* | F | AA | 29 | 66 | 175 | 28.2 | Cannabis | 10 | Smoke | 14 | 12 | 2 blunts | Previous day |

A, T | 8 |

| C* | M | AA | 36 | 75 | 170 | 21.2 | Cannabis | 22 | Smoke | 14 | 14 | 0.25 oz | 3 h Previous |

A, C, T |

21 |

| D* | M | AA | 29 | 67 | 195 | 30.5 | Cannabis | 9 | Smoke | 14 | 20 | 2 blunts | 3 h Previous |

A, T | 30 |

| E* | M | AA | 28 | 70 | 160 | 23.0 | Cannabis | 13 | Smoke | 14 | 14 | 2 blunts | Same Day |

A | 10 |

| F* | F | AA | 21 | 68 | 150 | 22.8 | Cannabis | 7 | Smoke | 3 | 14 | 4 blunts | 3 h Previous |

A, T | 30 |

| G* | F | AA | 28 | 62 | 149 | 27.2 | Cannabis | 11 | Smoke | 14 | 16 | 3 blunts | 2 h Previous |

A, T | 13 |

| H | M | AA | 21 | 73 | 208 | 27.4 | Cannabis | 9 | Smoke | 14 | 12 | 2 blunts | 2 d Previous |

A, T | 21 |

| I | F | U | 38 | 65 | 160 | 26.6 | Cannabis | 22 | Smoke | 14 | 16 | 2–3 blunts | 2 d Previous |

A, C, P, T |

23 |

| J | M | AA | 27 | 70 | 169 | 24.2 | Cannabis | 9 | Smoke | 14 | 15 | 2 blunts | Previous Day |

A; T | 7 |

| K | M | AA | 33 | 67 | 170 | 26.6 | Cannabis | 11 | Smoke | 14 | 21 | 3 joints | 2 d Previous |

A, T | 20 |

| L | M | W | 23 | 67 | 140 | 21.9 | Tobacco | 4 | Smoke | 13 | 16 | 1 oz | Previous Day |

A, T | 25 |

| M | M | AI | 23 | 74 | 145 | 18.6 | Cannabis | 5 | Smoke | 14 | 17 | 4 blunts | 2 d Previous |

A | 22 |

| N | F | AA | 21 | 67 | 200 | 31.3 | Tobacco | 12 | Smoke | 14 | 9 | 0.5 oz | 10 h previous |

A, T | 27 |

| O | F | AA | 19 | 67 | 150 | 23.5 | Cannabis | 4 | Smoke | 14 | 15 | 2 blunts | Previous Day |

T | 7 |

| P | M | AA | 24 | 74 | 250 | 32.1 | Tobacco | 10 | Smoke | 10 | 14 | $10 | Previous Day |

A, T | 30 |

| Q | M | AA | 22 | 69 | 150 | 22.1 | Cannabis | 7 | Smoke | 6 | 14 | 2 blunts | Previous Day |

A, T | 23 |

| R | M | AA | 33 | 71 | 155 | 21.6 | Cannabis | 5 | Smoke | 8 | 17 | 1 blunt | Previous Day |

A, T | 17 |

| S | M | U | 24 | 72 | 174 | 23.6 | Tobacco | 6 | Smoke | 10 | 18 | 2 blunts | 12 h previous |

A, T | 28 |

| T | M | AA | 26 | 72 | 200 | 27.1 | Cannabis | 13 | Smoke | 12 | 13 | 4 blunts | 15 h previous |

A, T | 30 |

| U | F | AA | 28 | 62 | 140 | 25.6 | Cannabis | 12 | Smoke | 14 | 15 | 1–2 blunts | 19 h previous |

A, T | 3 |

| V | F | AA | 22 | 60 | 125 | 24.4 | Cannabis | 8 | Smoke | 14 | 14 | 5 blunts | 5 h previous |

A, T | 30 |

| W | F | AA | 22 | 62 | 180 | 32.9 | Cannabis | 4 | Smoke | 14 | 14 | 10 blunts | 6 h previous |

A, T | 18 |

| X | F | AA | 30 | 63 | 130 | 23.0 | Cannabis | 12 | Smoke | 10 | 18 | 2 blunts | Previous Day |

A, T | 28 |

| Y | M | AA | 25 | 67 | 150 | 23.5 | Cannabis | 9 | Smoke | 14 | 14 | 6 blunts | 12 h previous |

A, T | 30 |

| Z | M | AA | 22 | 73 | 195 | 25.7 | Cannabis | 4 | Smoke | 14 | 18 | 2 blunts | Previous day |

A, T | 29 |

| AA | F | W | 26 | 63 | 150 | 26.6 | Cannabis | 2 | Smoke | 11 | 21 | 7 joints | Same day |

A, T | 14 |

| BB | M | AA | 30 | 74 | 195 | 25.0 | Cannabis | 16 | Smoke | 14 | 14 | 1 ounce | Same day |

A, T | 30 |

| CC | F | AA | 22 | 63 | 160 | 28.3 | Cannabis | 8 | Smoke | 14 | 14 | 4–5 blunts | Previous day |

A, T | 21 |

| DD | F | AA | 26 | 61 | 147 | 27.8 | Cannabis | 9 | Smoke | 14 | 17 | 4 blunts | Previous day |

A, T | 29 |

| EE | F | AA | 23 | 63 | 220 | 39.0 | Cannabis | 8 | Smoke | 14 | 15 | 8 blunts | 10 h previous |

A, T | 29 |

| FF | F | AA | 23 | 66 | 198 | 32.0 | Cannabis | 3 | Smoke | 14 | 20 | 4 blunts | 9 h previous |

A | 30 |

| GG | F | AA | 23 | 63 | 240 | 42.5 | Cannabis | 5 | Smoke | 7 | 18 | 2 blunts | Previous day |

A, T | 29 |

Persistent THC Group with THC ≥2.5 ng/mL for more than 72 h

AA: African-American; AI: American-Indian; U: Unknown; W: White; A: Alcohol; C: Cocaine; P: Phencyclidine; T: Tobacco

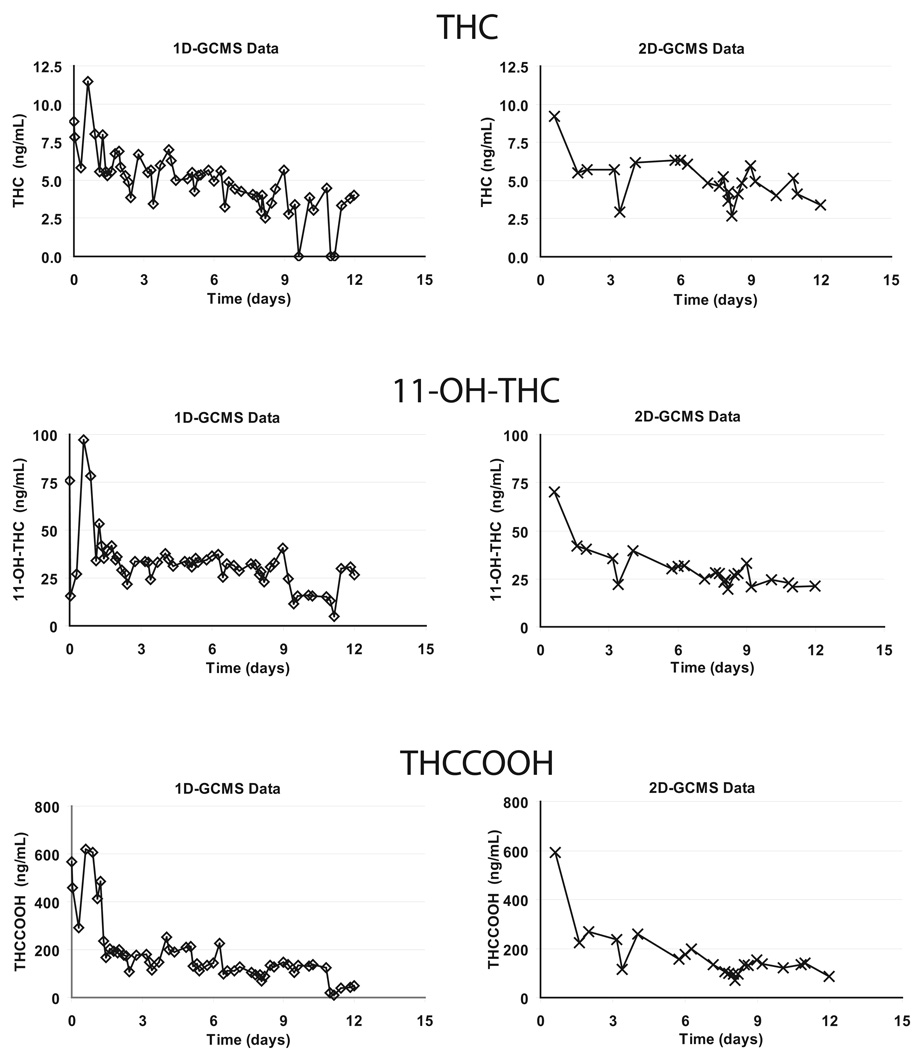

The Persistent THC Group was 29.1 ± 4.7 years old, weighed 174.1 ± 25.7 lbs, and had a mean BMI of 25.8 ± 3.4 with only one individual classified as obese. The Persistent THC Group self-reported first use of cannabis at 15.0 ± 2.5 years, with current smoking of 2.3 ± 1.0 blunts per day on average 11.4 ± 4.5 days out of the last 14. For this Group, a total of 1082 urine specimens were analyzed by 1D-GCMS. Critical urine specimens (n = 161) at and following the times of last THC detection in the Persistent THC Group were subsequently re-extracted and verified by 2D-GCMS with cryotrapping to characterize cannabinoid detection times. A representative comparison of 1- and 2D-GCMS results and excretion curves are shown in Figure 1. Two of these participants (Subjects A and B) chose to withdraw from the study prior to producing THC-negative urine specimens, preventing determination of the time of last THC detection

Figure 1.

One dimensional-gas chromatography mass spectrometry (1D-GCMS) and two dimensional-gas chromatography mass spectrometry (2D-GCMS) data from Participant A. Urine excretion curves for Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), 11-hydroxy-THC (11-OH-THC), and 11-nor-9-carboxyTHC (THCCOOH) are shown.

3.1 DETECTION TIMES – THC

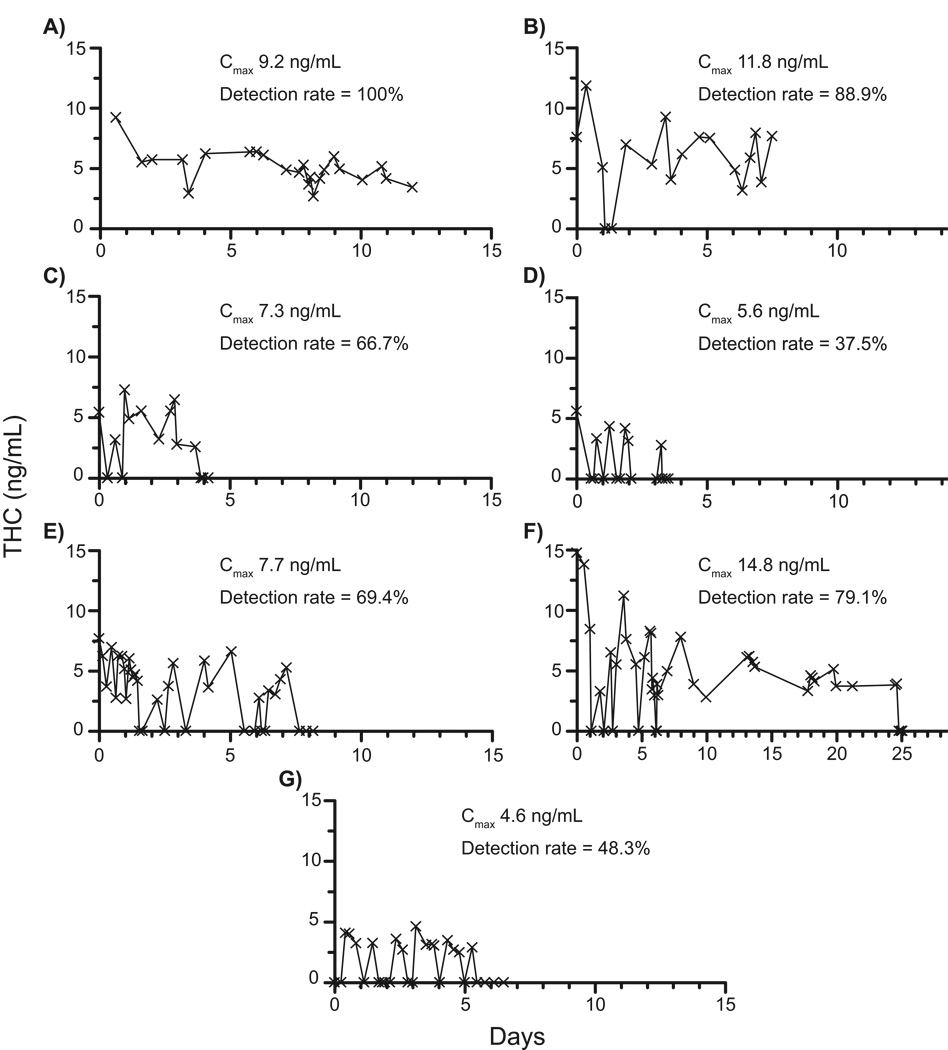

In the Persistent THC Group, last THC detection times with a 2.5 ng/mL GCMS cutoff ranged from 3.3 – 24.7 days (Table 2) with a median of 7.2 days, including the two subjects who chose to withdraw from the study and leave the unit after 12.0 (Subject A) and 7.5 (Subject B) days, prior to producing consecutive THC negative urine specimens. Other subjects’ urine specimens were THC positive for 3.3, 3.7, 4.6, 7.2 and 24.7 (Subject F) days (Table 2) after admission to the study. Subject F who excreted THC in the urine for more than 24 days, produced THC-negative specimens for five days after last THC detection, clearly enabling an accurate determination of her THC detection times in urine.

Table 2.

Urine Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) maximum daily concentrations as determined by one-dimensional gas chromatography mass spectrometry, times of first negative and last positive specimens (≥2.5 ng/mL) in a subgroup of seven heavy chronic cannabis users during 24 h monitored abstinence on a secure research unit.

| Maximum THC Concentration (ng/mL) 1 | Highe st THC |

Time of Highe st |

Time of First Negati ve |

Time of Last Positiv e |

Detectio n Rate2 |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subje ct |

Entr y |

Da y 1 |

Da y 2 |

Da y 3 |

Da y 4 |

Da y 5 |

Da y 6 |

Da y 7 |

Da y 8 |

Da y 9 |

Da y 10 |

Da y 11 |

Da y 12 |

Da y 13 |

Da y 14 |

Da y 22 |

Da y 25 |

Day 26 |

ng/mL | Days | Days | Days | % |

| A | 8.8 | 11. 5 |

8.0 | 6.7 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 4.3 | 5.7 | 3.4 | 4.5 | 4.0 | * | 11.5 | 0.6 | 11.0 | 12.0* | 100.0 | ||||

| B | 7.3 | 11. 0 |

8.2 | 8.5 | 7.9 | 8.2 | 8.4 | 7.0 | 7.6 | ** | 11.0 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 7.5** | 86.2 | ||||||||

| C | 5.8 | 8.3 | 7.6 | 6.5 | 4.5 | N D |

8.3 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 3.7 | 64.3 | ||||||||||||

| D | 5.2 | 5.2 | 6.3 | 2.6 | 3.5 | N D |

6.3 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 3.3 | 44.2 | ||||||||||||

| E | 8.1 | 8.1 | 7.8 | 6.1 | 4.4 | 6.0 | 7.3 | 5.0 | 4.7 | N D |

8.1 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 7.2 | 70.4 | ||||||||

| F | 15.4 | 17. 2 |

10. 1 |

8.9 | 16. 4 |

8.8 | 10. 7 |

8.5 | 9.3 | 7.3 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 6.8 | 5.1 | 6.5 | 3.0 | 3.5 | ND | 17.2 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 24.7 | 85.8 |

| G | ND | 4.8 | 3.6 | 4.7 | 5.7 | 3.6 | ND | 5.7 | 3.1 | 1.1 | 4.6 | 61.5 | |||||||||||

| Mean | 9.7 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 9.0 | 72.7 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Media n |

8.3 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 7.2 | 70.4 | ||||||||||||||||||

Highest THC concentration within day

Number of specimens greater than limit of quantification divided by total number of specimens tested

ND = none detected (<2.5 ng/mL limit of detection)

Specimen collection terminated at 12.0 days

Specimen collection terminated at 7.5 days

3.2 THC CONCENTRATIONS IN URINE

Table 2 summarizes maximum daily urine THC concentrations after drug cessation in the Persistent THC Group over the entire collection period (1D-GCMS). Time of peak THC urine concentrations ranged from 0.0 – 3.1 days (median 0.6 days) after abstinence initiation. The highest urine THC concentrations in this Group ranged from 5.7 – 17.2 ng/mL. In six of seven participants in the Group, THC negative specimens were interspersed between THC-positive specimens. Times of the first THC-negative specimen varied from 0.3 – 11.0 days.

Urinary THC excretion profiles confirmed by 2D-GCMS are shown in Figure 2 and demonstrate varied excretion patterns. Twenty-three specimens collected from admission to discharge were tested for Subject A. All specimens were THC-positive (>2.5 ng/mL) with concentrations ranging from 2.7 – 9.2 ng/mL. Specimens 11.0 and 12.0 days post admission had THC concentrations of 4.1 and 3.4 ng/mL, respectively. Sixteen of 18 specimens had THC >2.5 ng/mL (88.9% detection rate) ranging from 3.2 – 11.8 ng/mL. THC was not detected in two specimens at 1.1 and 1.3 days. THC quantification in the final available specimen (7.5 days) was 7.7 ng/mL. Subject C’s urine THC concentrations ranged from <2.5 – 7.3 ng/mL until day 3; all specimens after 88 hours were < 2.5 ng/mL. Three specimens quantifying <2.5 ng/mL were interspersed among the 13 collected in the first 3.9 days. Subject D displayed the lowest THC detection rate in the Group (37.5%), with an entry concentration of 5.6 ng/mL and only 6 of 16 specimens testing positive over 3.5 days. Subject E’s THC concentrations ranged from none detected to 7.7 ng/mL. Ten of the 35 specimens quantified by 2D-GCMS were <LOQ. Participant F had detectable THC concentrations for the longest time of any chronic frequent user in this study. THC was detected in the urine 24.7 days after cessation, with later specimens (up to 30 days) negative for THC. Thirty-four of 43 specimens tested positive for a 79.1% detection rate over 25 days. Six specimens <LOQ (2.5 ng/mL) occurred within the first 7 days. THC concentrations in Subject G specimens ranged from <2.5 – 4.6 ng/mL with negative specimens interspersed at regular intervals on each of the five testing days.

Figure 2.

Urine Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) excretion curves from seven chronic heavy cannabis users with THC concentrations ≥2.5 ng/mL for more than 72 h while residing on a closed research unit. Quantification was by two-dimensional gas chromatography mass spectrometry.

3.3 11-OH-THC AND THCCOOH CONCENTRATIONS IN URINE

Maximum within-day urine concentrations of 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH metabolites by 1D-GC/MS from the Persistent THC Group are shown in Table 3. 11-OH-THC was detected in all of the specimens from 6 of 7 subjects and in 42 of 43 specimens from Subject D for an overall detection rate of 99.7% (n = 336). Urine 11-OH-THC Cmax ranged from 41 – 204 ng/mL. Time of highest urine 11-OH-THC concentration (Tmax) ranged from 0.0 – 0.6 days. Mean peak concentration time was 0.2 days after cannabis cessation. Time of highest concentration was within the first day following cessation for all subjects and mean maximum 11-OH-THC concentrations were substantial at 51, 42, and 40 ng/mL during days 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

Table 3.

Urine 11-hydroxy-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (11-OH-THC) and 11-nor-9-carboxy-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THCCOOH) maximum daily concentrations by one-dimensional gas chromatography mass spectrometry quantification in seven heavy chronic cannabis users during 24 h monitored abstinence on a secure research unit.

| Maximum Within-Day 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH Concentrations (ng/mL) 1 | Highest Concentration |

Time of Highest |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Day 1 |

Day 2 |

Day 3 |

Day 4 |

Day 5 |

Day 6 |

Day 7 |

Day 8 |

Day 9 |

Day 10 |

Day 11 |

Day 12 |

Day 13 |

Day 14 |

Day 22 |

Day 25 |

(ng/mL) | (Days) | |

| A | 11-OH-THC | 97 | 53 | 34 | 34 | 38 | 37 | 37 | 32 | 41 | 25 | 16 | 31 | 97 | 0.6 | ||||

| THCCOOH | 620 | 484 | 178 | 180 | 253 | 212 | 225 | 128 | 148 | 139 | 137 | 50 | 620 | 0.6 | |||||

| B | 11-OH-THC | 144 | 78 | 83 | 75 | 67 | 67 | 63 | 64 | 144 | 0.4 | ||||||||

| THCCOOH | 401 | 182 | 204 | 172 | 207 | 189 | 161 | 118 | 401 | 0.9 | |||||||||

| C | 11-OH-THC | 41 | 38 | 39 | 26 | 41 | 0.2 | ||||||||||||

| THCCOOH | 851 | 710 | 668 | 308 | 851 | 1.0 | |||||||||||||

| D | 11-OH-THC | 90 | 34 | 21 | 31 | 90 | 0.0 | ||||||||||||

| THCCOOH | 489 | 468 | 133 | 197 | 489 | 0.0 | |||||||||||||

| E | 11-OH-THC | 71 | 46 | 34 | 27 | 31 | 39 | 22 | 22 | 8 | 71 | 0.0 | |||||||

| THCCOOH | 312 | 324 | 195 | 180 | 207 | 180 | 99 | 126 | 66 | 324 | 1.2 | ||||||||

| F | 11-OH-THC | 204 | 86 | 65 | 69 | 47 | 52 | 35 | 42 | 41 | 29 | 37 | 39 | 32 | 26 | 16 | 18 | 204 | 0.0 |

| THCCOOH | 581 | 303 | 121 | 141 | 126 | 105 | 123 | 119 | 105 | 69 | 81 | 75 | 88 | 60 | 31 | 38 | 581 | 0.2 | |

| G | 11-OH-THC | 41 | 23 | 21 | 20 | 19 | 16 | 41 | 0.4 | ||||||||||

| THCCOOH | 395 | 206 | 221 | 146 | 102 | 79 | 395 | 0.6 | |||||||||||

| median time of highest 11-OH-THC | 0.2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| median time of highest THCCOOH | 0.6 | ||||||||||||||||||

Highest concentration within day

THCCOOH was measurable in all urine specimens with Cmax (range 324 – 851 ng/mL) within 1.2 days (mean 0.6 + 0.42 days) of abstinence. Testing of all 33 participants was discontinued when THC was no longer detectable (< 2.5 ng/mL) in three successive urine specimens; therefore, last detection of 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH in chronic users remains to be determined, although currently these analytes were detected in one subject’s urine for 24.7 days of abstinence with continuous monitoring.

4.0 DISCUSSION

For the first time, the hypothesis that THC and 11-OH-THC in urine indicated new cannabis use was tested with these novel cannabinoid excretion data. Urinary concentrations of THC and 11-OH-THC in chronic, heavy cannabis smokers during extended supervised abstinence and following tandem enzymatic and alkaline hydrolysis are presented. Subjects resided on a secure clinical research unit throughout to prevent access to cannabis and other drugs. Highest analyte concentrations, times of first negative and last positive THC specimens, and detection rates were determined to guide interpretation of urine cannabinoid tests in drug treatment, workplace, military and criminal justice programs.

Detection times of psychoactive THC and 11-OH-THC in these self-reported chronic users were much longer than previously reported. Last THC detection times after admission to the study ranged from 3 – 24 days for the Persistent THC Group with extensive self-reported cannabis histories of up to 22 years. To verify these findings, we applied a highly sensitive ad selective 2D-GCMS method and demonstrated that results and excretion curves (Figure 1) showed good agreement between the 1- and 2D-GCMS methods. Inter-individual variations in time of last THC detection and in THC detection rates were high. Detection rates varied from 37.5% to 100%, with negative specimens interspersed with positives in 6 of 7 subjects. Interspersed negative specimens are related to the slow release of THC from tissues and individuals’ hydration state. This release may be variable and is poorly understood, but factors such as diet and exercise may be important. An important implication from the present study is that a positive specimen for THC following a negative urine specimen cannot be attributed to new cannabis use.

Manno et al reported urinary THC concentrations in 8 participants after controlled dosing of one 1.77% or 3.58% THC cigarette (Manno et al., 2001). THC concentrations were <1.5 ng/mL by 6 h and 11-OH-THC remained detectable up to 8 h. Subjects in the study were self-reported light users of 1–3 cannabis cigarettes per week. From these data, the authors concluded that urinary THC and 11-OH-THC concentrations ≥ 1.5 ng/mL suggested cannabis use within 8 hr. Although this may apply to infrequent cannabis users, the present research demonstrates that urinary THC and 11-OH-THC can be quantified at concentrations above 2.5 ng/mL for weeks in subjects whose history includes frequent long-term cannabis use for extended periods of time.

The extended duration of 11-OH-THC metabolite detection reported here is in agreement with a study of urinary 11-OH-THC metabolite excretion profiles in chronic users (Fraser and Worth, 2004). Substantial urinary 11-OH-THC concentrations, extended detection times, and an 81% positive rate for 11-OH-THC were reported in 4 subjects in an uncontrolled clinical setting (Fraser and Worth, 2004). Another study (Ellis et al., 1985) reported a mean last detection time of 27 days for cannabinoid metabolites by immunoassay, with 77 days required to drop below the cutoff calibrator for 10 consecutive days in some subjects.

Limitations of this study include the inability to complete elimination profiles and determine times of last detection for metabolites 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH, due to a 30-day residence protocol limitation. Primary studies monitored neurocognitive deficits and effects of cannabis withdrawal in long-term cannabis users. The urinary cannabinoid excretion was conducted as a contemporaneous secondary study. Family and child-care responsibilities, lack of desire to reside on a closed unit without visitors for an extended period, and cost were all factors limiting residential stay. An additional limitation is the lack of creatinine normalization of THCCOOH data. The objective and focus of the study was evaluation of urinary THC and 11-OH-THC as indicators of recent cannabis use. These analytes are not routinely monitored in urine and are not normalized to creatinine concentrations. We wanted to treat single urine specimens as they would be evaluated in routine drug testing programs. However, attempts were made to compensate for potentially dilute specimens; low LOQs of 2.5 ng/mL were much lower than the routine cutoff of 15 ng/mL THCCOOH used in most drug testing programs, and three consecutive negative urine specimens were required prior to defining the last THC positive specimen.

Another limitation was the extended frozen storage time for urine specimens necessitated by the large number of specimens analyzed, the time required to conduct the human subjects studies, and time required to verify these unexpected results with the second 2D-GCMS analysis. Extended frozen storage could have degraded cannabinoids over time. Urine specimens were tested by 1D-GCMS up to three years after collection and storage at −20°C. Specimens were retested by a validated 2D-GCMS method within the next two years, for a total storage time of up to five years. Results are highly reliable and verified by 2D-GCMS. It is possible that urinary concentrations and last detection times are underestimated due to degradation in frozen storage, but this would only lead to an underestimation of last detection time. The hypothesis that THC and 11-OH-THC are biomarkers of recent cannabis use was disproven.

These data demonstrate for the first time that following long-term frequent cannabis smoking, THC and 11-OH-THC can be measured in urine for up to 24 days (using a limit of quantification of 2.5 ng/mL), negating their value as urinary biomarkers of recent cannabis use. These results support the hypothesis of Hunt et al that the rate-limiting step in the terminal elimination of THC is the slow excretion of THC from tissue stores that may be extended following chronic cannabis exposure (Hunt and Jones, 1980).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Allan Barnes for assistance with data interpretation and preparation of the manuscript and Jennifer Runkle and Wesen Nebro for technical assistance.

Role of Funding Source

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. This clinical study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Authors are employed by the Chemistry and Drug Metabolism and Molecular Neuropsychiatry sections of the Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham TT, Lowe RH, Pirnay SO, Darwin WD, Huestis MA. Simultaneous GC-EI-MS determination of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol, 11-hydroxy-Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol, and 11-nor-9-carboxy-Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol in human urine following tandem enzyme-alkaline hydrolysis. J Anal Toxicol. 2007;31:477–485. doi: 10.1093/jat/31.8.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolla KI, Brown K, Eldreth D, Tate K, Cadet JL. Dose-related neurocognitive effects of marijuana use. Neurology. 2002;59:1337–1343. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000031422.66442.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolla KI, Eldreth D, Matochik JA, Cadet JL. Neural substrates of faulty decision-making in abstinent marijuana users. Neuroimage. 2005;26:480–492. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolla KI, Lesage SR, Gamaldo CE, Neubauer DN, Funderburk FR, Cadet JL, David PM, Verdejo-Garcia A, Benbrook AR. Sleep disturbance in heavy marijuana users. Sleep. 2008;31:901–908. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.6.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dackis CA, Pottash AIC, Annitto W, Gold MS. Persistence of urinary marijuana levels after supervised abstinence. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1196–1198. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eldreth D, Matochik JA, Cadet JL, Bolla KI. Abnormal brain activity in prefrontal brain regions in abstinent marijuana users. Neuroimage. 2004;23:914–920. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis GM, Mann MA, Judson BA, Schramm NT, Tashchian A. Excretion patterns of cannabinoid metabolites after last use in a group of chronic users. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1985;38:572–578. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1985.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraser AD, Worth D. Urinary excretion profiles of 11-nor-9-carboxy-Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Study III. A Delta-9-THC-COOH to creatinine ratio study. Forensic Sci Int. 2003;137:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2003.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser AD, Worth D. Urinary excretion profiles of 11-nor-9-carboxydelta9-tetrahydrocannabinol and 11-hydroxy-delta9-THC: cannabinoid metabolites to creatinine ratio study IV. Forensic Sci Int. 2004;143:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herning RI, Better W, Tate K, Cadet JL. EEG deficits in chronic marijuana abusers during monitored abstinence - Preliminary findings. Neuroprotective Agents. 2003;993:75–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herning RI, Better W, Tate K, Cadet JL. Cerebrovascular perfusion in marijuana users during a month of monitored abstinence. Neurology. 2005;64:488–493. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150882.69371.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huestis MA, Mitchell JM, Cone EJ. Detection times of marijuana metabolites in urine by immunoassay and GC-MS. J Anal Toxicol. 1995;19:443–449. doi: 10.1093/jat/19.6.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huestis MA, Mitchell JM, Cone EJ. Urinary excretion profiles of 11-nor-9-carboxy-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in humans after single smoked doses of marijuana. J Anal Toxicol. 1996;20:441–452. doi: 10.1093/jat/20.6.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huestis MA, Cone EJ. Urinary excretion half-life of 11-nor-9-carboxydelta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in humans. Ther Drug Monit. 1998a;20:570–576. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199810000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huestis MA, Cone EJ. Differentiating new marijuana use from residual drug excretion in occasional marijuana users. J Anal Toxicol. 1998b;22:445–454. doi: 10.1093/jat/22.6.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huestis MA, Smith ML. Human cannabinoid pharmacokinetics and interpretation of cannabinoid concentrations in biological fluids and tissues. In: Elsohly M, editor. Marijuana and the Cannabinoids. New York: Humana Press; 2005. pp. 205–235. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunt CA, Jones RT. Tolerance and disposition of tetrahydrocannabinol in man. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1980;215:35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johansson E. Terminal elimination plasma half-life of delta-1-tetrahydrocannabinol (delta-1-THC) in heavy users of marijuana. European J Clin Pharmacol. 1989a;37:273–277. doi: 10.1007/BF00679783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johansson E, Halldin MM. Urinary excretion half-life of delta1-tetrahydrocannabinol-7-oic acid in heavy marijuana users after smoking. J Anal Toxicol. 1989b;13:218–223. doi: 10.1093/jat/13.4.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johansson E, Gillespie HK, Halldin MM. Human urinary excretion profile after smoking and oral administration of [14C] delta-1-tetrahydrocannabinol. J Anal Toxicol. 1990;14:176–180. doi: 10.1093/jat/14.3.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly P, Jones RT. Metabolism of tetrahydrocannabinol in frequent and infrequent marijuana users. J Anal Toxicol. 1992;16:228–235. doi: 10.1093/jat/16.4.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kemp PM, Abukhalaf IK, Manno JE, Manno BR, Alford DD, Abusada GA. Cannabinoids in humans. I. Analysis of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and six metabolites in plasma and urine using GC-MS. J Anal Toxicol. 1995a;19:285–291. doi: 10.1093/jat/19.5.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kemp PM, Abukhalaf IK, Manno JE, Manno BR, Alford DD, McWilliams ME, Nixon FE, Fitzgerald MJ, Reeves RR, Wood MJ. Cannabinoids in humans. II. The influence of three methods of hydrolysis on the concentration of THC and two metabolites in urine. J Anal Toxicol. 1995b;19:292–298. doi: 10.1093/jat/19.5.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowe RH, Karschner EL, Schwilke EW, Barnes AJ, Huestis MA. Simultaneous quantification of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), 11-hydroxydelta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (11-OH-THC), and 11-nor-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol-9-carboxylic acid (THCCOOH) in human plasma using two-dimensional gas chromatography, cryofocusing, and electron impact-mass spectrometry. J Chromatog A. 2007;1163:318–327. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.06.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manno JE, Manno BR, Kemp PM, Alford DD, Abukhalaf IK, McWilliams ME, Hagaman FN, Fitzgerald MJ. Temporal indication of marijuana use can be estimated from plasma and urine concentrations of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, 11-hydroxy-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, and 11-nor-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol-9-carboxylic acid. J Anal Toxicol. 2001;25:538–549. doi: 10.1093/jat/25.7.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matochik JA, Eldreth D, Cadet JL, Bolla KI. Altered brain tissue composition in heavy marijuana users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McBurney LJ, Bobbie BA, Sepp LA. GC/MS and Emit analyses for delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol metabolites in plasma and urine of human subjects. J. Anal. Tox. 1986;10:56–64. doi: 10.1093/jat/10.2.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Musshoff F, Madea B. Review of biologic matrices (urine, blood, hair) as indicators of recent or ongoing cannabis use. Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28:155–163. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000197091.07807.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peat MA. Distribution of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and its metabolites. In: Baselt RC, editor. Advances in Analytical Toxicology II. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1989. pp. 186–217. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith-Kielland A, Skuterud B, Morland J. Urinary Excretion of 11-nor-9-carboxy-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabinoids in frequent and infrequent drug users. J Anal Toxicol. 1999;23:323–332. doi: 10.1093/jat/23.5.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]