Abstract

Background

Mechanosensing governs many processes from molecular to organismal levels, including during cytokinesis where it ensures successful and symmetrical cell division. While many proteins are now known to be force sensitive, myosin motors with their ATPase activity and force-sensitive mechanical steps are well poised to facilitate cellular mechanosensing. For a myosin motor to experience tension, the actin filament must also be anchored.

Results

Here, we find a cooperative relationship between myosin-II and the actin crosslinker cortexillin-I where both proteins are essential for cellular mechanosensory responses. While many functions of cortexillin-I and myosin-II are dispensable for cytokinesis, all are required for full mechanosensing. Our analysis demonstrates that this mechanosensor has three critical elements: the myosin motor where the lever arm acts as a force amplifier, a force-sensitive bipolar thick filament assembly, and a long lived actin crosslinker, which anchors the actin filament so that the motor may experience tension. We also demonstrate that a Rac small GTPase inhibits this mechanosensory module during interphase, allowing the module to be primarily active during cytokinesis.

Conclusions

Overall, myosin-II and cortexillin-I define a cellular-scale mechanosensor that controls cell shape during cytokinesis. This system is exquisitely tuned through the enzymatic properties of the myosin motor, its lever arm length and bipolar thick filament assembly dynamics. The system also requires cortexillin-I to stably anchor the actin filament so that the myosin motor can experience tension. Through this cross-talk, myosin-II and cortexillin-I define a cellular-scale mechanosensor that monitors and corrects shape defects, ensuring symmetrical cell division.

Introduction

Similar to chemical cues that direct cell behaviors such as chemotaxis, cell proliferation, and cell fate specification, mechanical signals are important for guiding a range of physiological processes. At the organismal level, mechanosensing and mechanotransduction are at the core of many processes, including bone remodeling, hearing, muscle growth and blood pressure regulation [1]. At the cellular level, mechanosensing is needed during processes like cytokinesis [2] and can help direct the differentiation of stem cells [3]. Molecularly, mechanosensing can occur through stretch-activated channels in the plasma membrane [4], through extension of focal adhesion-associated proteins (e.g. [5–7]), and potentially directly through myosin motors, which are force-transmitting enzymes [8–11]. Hearing adaptation likely occurs through a strain-sensitive myosin-I family member, which adjusts its position on the actin filament to modulate the tension on the tip link, controlling channel opening [12]. In muscle, more myosin-II motor domains (cross-bridges) are recruited into the load-bearing state when the muscle contracts under load than when it contracts without load (the Fenn effect; e.g. [13]). However, in nonmuscle cells, it is much less clear how myosins directly respond to cellular-scale mechanical loads as the myosin-IIs are often in disorganized actin polymeric networks, rather than in paracrystalline arrays like those found in muscle. It is also unknown whether a single force sensitive enzyme (myosin) is sufficient to mediate a cellular response or whether nonmuscle cellular mechanosensing is a function of an entire cytoskeletal network. Still, with its load-sensitive kinetic steps, nonmuscle myosin-II is well poised to be at the center of a cellular-scale mechanosensor.

Previously, we discovered a mechanosensory system that helps govern cell shape progression during cytokinesis in Dictyostelium [2]. This mechanosensory system corrects natural shape defects during cell division by recruiting myosin-II and the actin crosslinker cortexillin-I to the site of cell deformation (hereafter referred to as the mechanosensory response). Using micropipette aspiration, we could control where the deformation occurred and direct myosin-II and cortexillin-I anywhere we wanted along the cortex (Fig. 1A, B). Myosin-II is essential for the shape control system and without it, the cells have altered cleavage furrow morphology, produce many more asymmetrically sized daughter cells, and cannot withstand mechanical perturbations. This shape control system does not depend on the mitotic spindle but is specific to cells in anaphase through the end of cytokinesis; interphase and early mitotic wild type cells do not show myosin-II or cortexillin-I redistribution in response to these mechanical perturbations induced with physiologically relevant pressures.

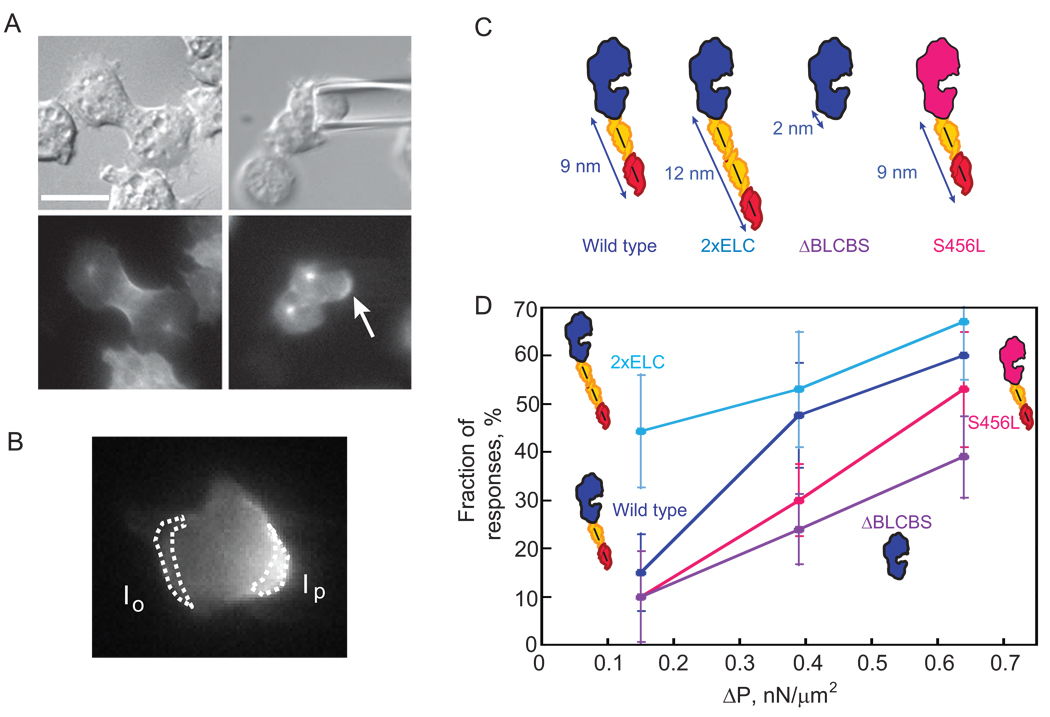

Fig. 1.

Myosin-II lever arm length determines the pressure-threshold-dependent behavior of the cellular mechanosensory response. (A) Representative micrographs showing a positive response to applied pressure. The cell is a myoII: Cit-ΔBLCBS;GFP-tubulin. Top panels, DIC images. Lower panels, fluorescence images. Left panels, cell before aspiration; right panels, cell during aspiration. The centrosomes are visible and Cit-ΔBLCBS accumulates at the micropipette (arrow). This cell is one of the positive responses of ΔBLCBS at 0.39 nN/µm2 pressure. Scale bar, 10 µm. (B) Micrograph of a mitotic cell expressing wild type GFP-myosin-II, showing a response. The intensity of the cortex inside the micropipette (Ip) and the opposite cortex (Io) were measured. The Ip/Io ratio was calculated and the log transform used for analysis. (C) Cartoon comparing wild type, 2xELC, ΔBLCBS, and S456L motors. Blue/pink, motor domain; yellow, essential light chain; red, regulatory light chain. (D) Graph shows the dependency of the fraction of responses on the applied pressure. Frequency histograms of each dataset and a second graph showing the overall average magnitudes (±SEMs) are provided in Fig. S3 (see Experimental Procedures also). At 0.15 nN/µm2 pressure, 2xELC is more responsive than wild type, S456L, or ΔBLCBS myosins (Student's t –test: P<0.01). Wild type and 2xELC myosin-II are more responsive than ΔBLCBS at 0.39 and 0.64 nN/µm2 pressure (Student’s t –test: P<0.01).

Here, we demonstrate that myosin-II and cortexillin-I interact to form a cellular-scale mechanosensor. Unlike cytokinesis, which can be rescued with mutant forms of myosin-II and cortexillin-I, our results show that the mechanosensory system is an exquisitely tuned molecular system that requires fully wild type myosin-II and cortexillin-I function. We show that myosin-II thick filament assembly and disassembly dynamics are required for the mechanosensory response, and that the small GTPase RacE is the cell-cycle stage specificity factor. Using motor and lever arm mutants of myosin-II, we demonstrate that the lever arm length specifies the pressure-threshold dependency of the responses. Finally, to generate tension, the myosin-II must pull against stably anchored actin filaments. Using single molecule methods, we demonstrate that cortexillin-I dwells on the actin filaments on time-scales much longer than the myosin, providing the stable anchoring required for mechanosensing. Overall, these data demonstrate that myosin-II and cortexillin-I cooperate to mediate cellular-scale mechanosensing during cell division.

Results

Wild type myosin-II thick filament assembly dynamics, regulatory phosphorylation, and mechanochemistry are required for the mechanosensory response

To determine how the mechanosensory system operates, we began with a complete structure-function analysis of myosin-II. First, we examined the role of bipolar thick filament (BTF) assembly dynamics in the mechanosensory response by analyzing cells expressing the non-phosphorylatable myosin-II heavy chain mutant (the 3xAla mutant), which stably assembles into thick filaments, and the constitutively disassembled myosin-II heavy chain mutant (the 3xAsp mutant). We anticipated that without assembling into BTFs [14, 15], 3xAsp myosin-II would not accumulate at the micropipette, which proved to be the case (n=10) (Fig S1A, Fig S2, Table S1). 3xAla myosin-II over-accumulates at the cleavage furrow cortex during cytokinesis [14, 15]. However, in all cases, myoII: 3xAla; RFP-tub cells aspirated with a range of pressures (ΔP=0.22–0.79 nN/µm2; n=16) failed to accumulate 3xAla myosin-II at the micropipette (Fig. S1B, Fig. S2). Similarly, the minimal domain (assembly domain; GFP-RLC binding site-assembly domain (GRA)) that is necessary and sufficient for targeting myosin-II to the cleavage furrow cortex but that lacks the BTF assembly regulatory region did not accumulate at the micropipette (ΔP=0.31–0.51 nN/µm2; n=6) (Fig S1C, Fig S2; Table S1). Given that the assembly domain constitutively assembles into BTFs [16, 17], this result is analogous to the 3xAla result. These results indicate that the full thick filament assembly and disassembly dynamics are essential for the mechanosensory system.

We then tested whether regulatory light chain (RLC) phosphorylation, which increases motor activity, is required for the mechanosensory response. In Dictyostelium cells, RLC phosphorylation is not required for cytokinesis, presumably because RLC phosphorylation only activates the myosin-II actin-activated ATPase activity ~3–5-fold [18]. In addition, a five-fold slower myosin-II due to shortening of the lever arm (ΔBLCBS, a deletion of both light chain binding sites) [19] and a ten-fold slower myosin-II (S456L) rescued cytokinesis dynamics [20]. Therefore, myosin-II mechanochemistry is not rate limiting for cytokinesis over at least a ten-fold range of (unloaded) velocity. However, RLC phosphorylation was required for the mechanosensory response. Only 11% (n=19) of ΔRLC cells complemented with RLC S13A (a mutant RLC where the phosphorylation site has been mutated to alanine) showed any detectable response (Fig S1D, Fig S2). In contrast, 64% of control cells (ΔRLC cells complemented with a wild type RLC) responded to mechanical perturbation (n=11; Table S1). Thus, full activation of the myosin-II motor domain through regulatory light chain phosphorylation is required for full mechanosensing ability.

Myosin-II lever arm tunes the pressure-threshold dependency

The results so far indicated that the motor activity itself is a critical component of the ability of the cells to mechanosense and suggested that myosin mechanochemistry could be the direct sensor. Myosin load dependency is commonly studied using single molecule assays where either the motor or actin filament is anchored, and the other component is pulled on using an optical tweezer [8–11]. However, in our experimental setup, we use micropipette aspiration to pull on the cell cortex, which is a network of crosslinked actin polymers with embedded myosin-II thick filaments [20]. We reasoned that we should be able to shift the pressure dependency of the mechanosensory response by altering lever arm length if myosin-II is the cellular-scale mechanosensor, the myosin-II lever arm is a rigid cantilever, and the maximum force production (Fmax) by the myosin motor is inversely related to lever arm length [21] (Fig. 1C). To analyze the data, we used two strategies (Experimental Procedures): we measured a response rate where responses are defined as a magnitude greater than two standard deviations of the interphase mean (wild type interphase cells do not show a response (see below) [2]; Fig. 1D), and we analyzed the entire distribution of the response magnitudes (Fig. S3). The combination of analysis strategies yielded a more complete picture of the lever arm dependency. First, we defined the pressure dependency for the accumulation of wild type myosin-II (9-nm lever arm and 3-µm/s unloaded velocity) to the micropipette (Fig. 1D; Fig.S3). We then studied two lever arm mutants: ΔBLCBS and 2xELC (Fig. 1A,C,D). ΔBLCBS (2-nm lever arm, 0.6-µm/s unloaded velocity), which has a much higher predicted Fmax, required greater applied pressure in order to respond (Fig. 1D; Fig. S3). Within the dynamic pressure range available for these experiments, the ΔBLCBS mutant myosin-II did not respond to wild type levels. In contrast, 2xELC (13-nm lever arm, 4-µm/s unloaded velocity), which is predicted to have a lower Fmax, required much lower pressures to achieve wild type levels of response (Fig. 1D; Fig. S3). Finally, because the unloaded velocities of the three lever arm lengths might explain the differences in responsiveness, we tested the 10–15-fold slower S456L myosin-II (9-nm lever arm, 0.2-µm/s unloaded velocity), which has a wild type lever arm [22]. The S456L myosin-II showed a pressure dependency that was lower than wild type myosin-II at intermediate pressures, but then at high pressures, S456L myosin-II responded nearly at wild type levels and at higher levels than ΔBLCBS did (Fig. 1D; Fig. S3). Thus, the unloaded velocity of myosin-II is not the major determinant; rather the lever arm length tunes the pressure range over which the cell responds to applied mechanical strain. The simplest explanation is that the mechanical stress stabilizes the myosin-II motor in the strongly bound state (increasing the duty ratio), and the lever arm length specifies the pressure required to lock the myosin-II motor onto the actin. Because the slopes of each of the pressure curves are similar between the myosin motor and lever arm mutants, this observation suggests that it is a pressure threshold that triggers the response and the force amplification by the lever arm tunes where this threshold sits.

Cooperative interactions between myosin-II and cortexillin-I are required for the mechanosensory system

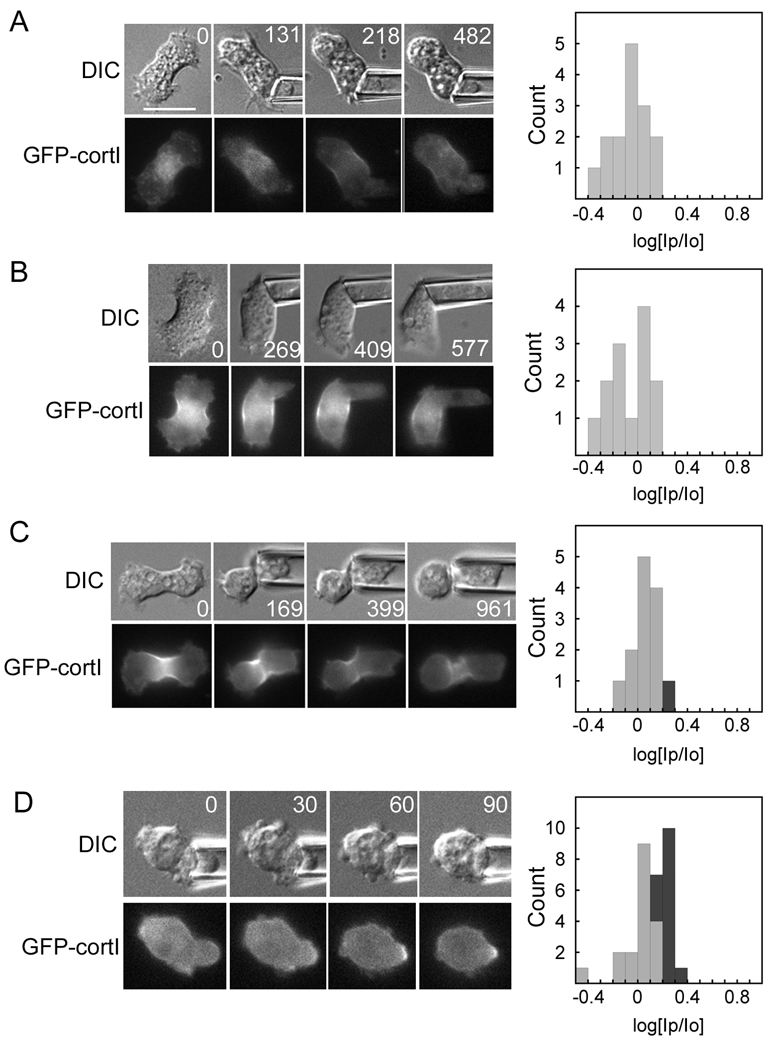

Because myosin-II and cortexillin-I are recruited to the micropipette [2], we then asked whether these proteins depend on each other for recruitment. In a myoII null background, cortexillin-I did not localize in response to mechanical load (ΔP=0.15–0.43 nN/µm2; n=15) (Fig. 2A). One hypothesis was that myosin-II may help mobilize the crosslinked actin network, promoting cortexillin-I mobility. To partially phenocopy this condition [23], we silenced expression of the actin crosslinker dynacortin using RNAi in a myoII:GFP-cortI cell (Fig 2B). Cortexillin-I recruitment to the pipette was not restored in dynacortin RNAi cells (ΔP=0.13–0.45 nN/µm2; n=13). Consistent with its lower mechanosensitivity particularly at lower pressures, S456L myosin-II only partially rescued GFP-cortI recruitment to the micropipette (ΔP=0.24–0.87 nN/µm2; n=13) (Fig. 2C). However, expression of unlabeled wild type myosin-II in a myoII:GFP-cortI background restored GFP-cortexillin-I recruitment in 44% of the cells (ΔP=0.22–0.57 nN/µm2; n=32) (Fig 2D).

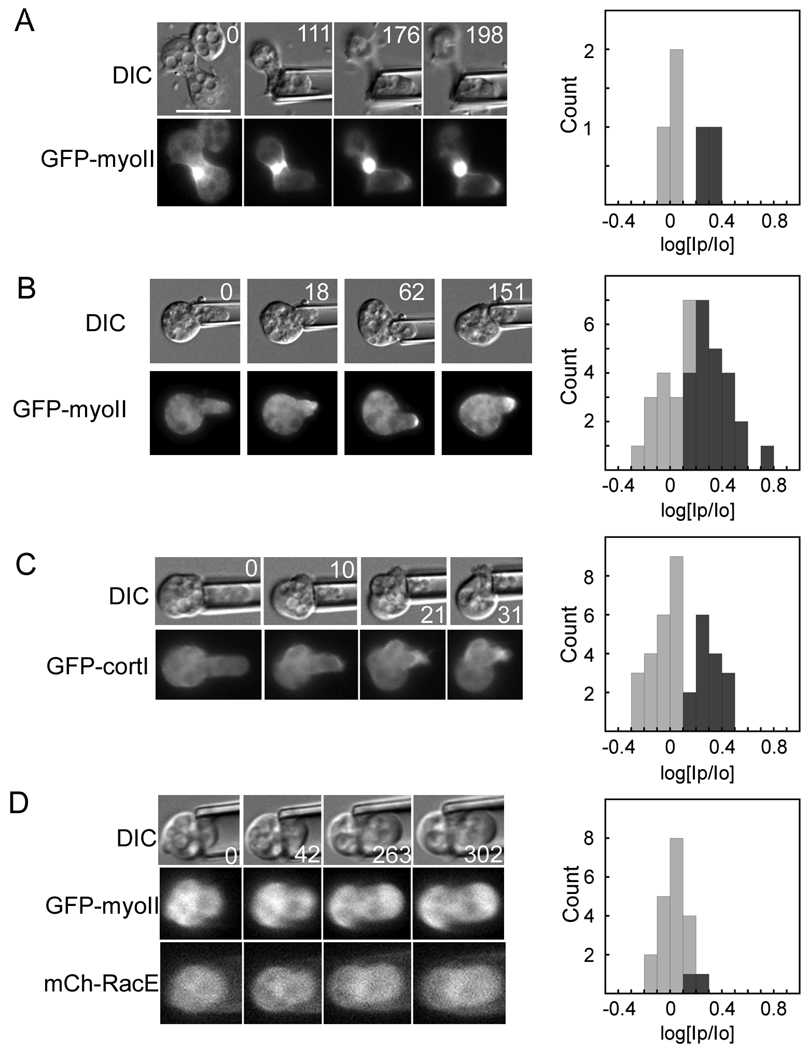

Fig. 2.

The mechanosensitive localization of cortexillin-I requires myosin-II. Example time series (times in s) of DIC and fluorescent images are shown for (A) a myoII:GFP-cortI cell aspirated with 0.30 nN/µm2 of pressure; (B) a myoII:GFP-cortI;dynhp cell aspirated with 0.21–0.28 nN/µm2 of pressure; (C) a myoII:GFP-cortI;S456L cell aspirated with 0.26 nN/µm2 of pressure; and (D) a myoII:GFP-cortI; myosin (rescue) cell aspirated with 0.45 nN/µm2 of pressure. Frequency histograms show measurements from all cells measured for each genotype. As described in the Experimental Procedures, the dark grey bars of the histograms indicate positive responses, while light grey bars indicate negative responses. Statistical analysis indicated that the myoII:GFP-cortI and myoII:GFP-cortI;myoII strains are statistically distinct (Student’s t –test: P<0.001). Scale bar, 10 µm.

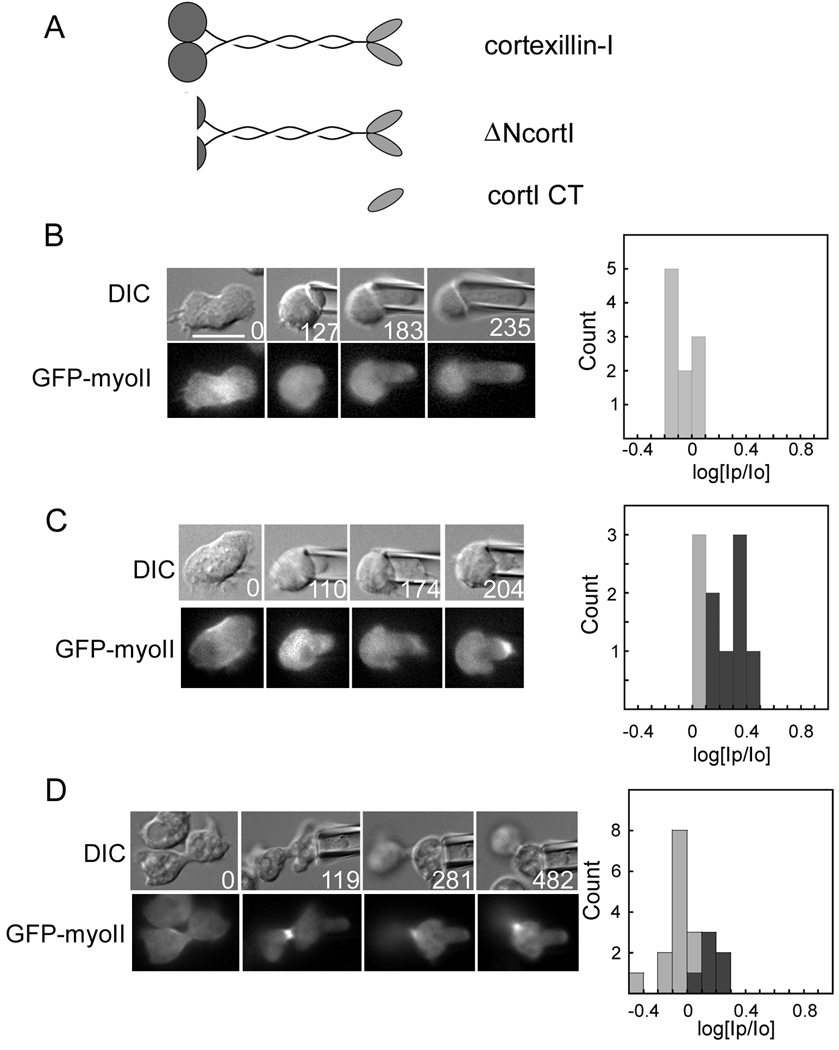

We then asked if myosin-II depends on wild type cortexillin-I (Fig. 3A). In two different cortexillin-I null strains, GFP-myosin-II did not move to the micropipette (Fig. 3B; Table S1). However, this defect could only be rescued to wild type levels with full-length cortexillin-I (70% of cells responding, n=10) (Fig. 3C; Table S1). Previous structure-function studies indicated that only the carboxyl-terminal domain of cortexillin-I (cortI CT) is needed for cytokinesis, for PIP2 binding and for actin crosslinking in vitro [24] (Fig. 3A). We tested whether cortI CT (Table S1) and ΔN-cortextillin-I (ΔNcortl), which is missing the amino-terminal calponin-homology domain that provides an additional actin-binding site, are sufficient for mechanosensing. CortI CT failed to rescue mechanosensing, and ΔNcortl only rescued to intermediate levels (Fig. 3D; Table S1). Thus, as with myosin-II, wild type cortexillin-I activity is required for mechanosensing. Because cortexillin-I is an actin crosslinking protein, we tested whether this dependency on cortexillin-I is a phenomenon general to any actin crosslinking protein. We analyzed mechanosensory responses in cells devoid of the actin crosslinkers dynacortin, enlazin, and fimbrin. None of these proteins was required for the mechanosensory response (Fig. S4), which is consistent with the observation that they do not move to the micropipette as myosin-II and cortexillin-I do [2]. Overall, cortexillin-I and myosin-II depend on each other for accumulating in response to mechanical perturbation as part of the mechanosensory shape control pathway.

Fig. 3.

The mechanosensitive localization of myosin-II requires cortexillin-I. (A) Wild type cortexillin-I, ΔNcortl and cortI CT were tested for their ability to restore mechanosensory responses. All three proteins rescue cytokinesis [24, 25]. Example time series (times in s) of DIC and fluorescence images are shown for (B) a cortI:GFP-myoII cell; (C) a cortI: GFP-myoII;RFP-cortI (full-length cortexillin-I) cell; and (D) a cortI: GFP-myoII;RFP-ΔNcortl cell. Frequency histograms show measurements from all cells measured for each genotype. Statistical analysis indicated that the cortI: GFP-myoII;RFP-tub and cortI: GFP-myoII;RFP-cortI strains are statistically distinct (Student’s t –test: P<0.0001). Scale bar, 10 µm.

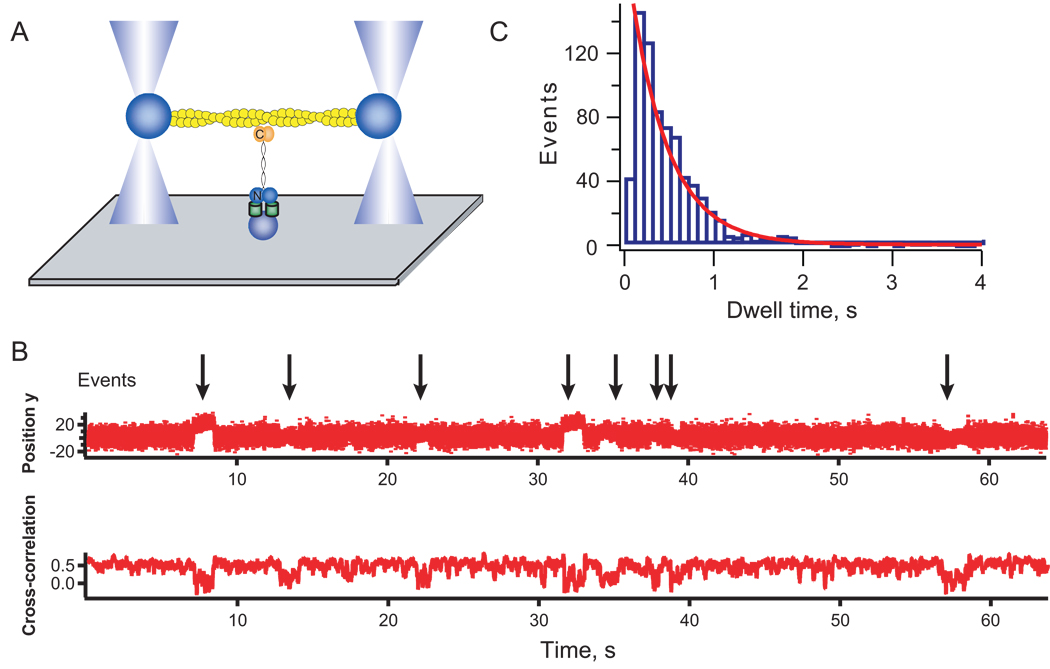

Myosins have load-sensitive actin-binding properties; yet for myosin to experience these loads, the actin filaments must be anchored to the actin network or to the plasma membrane. These anchor points must be longer lived than the myosin motor-actin interaction. Unloaded Dictyostelium myosin-II strongly bound state time is 2.4 ms [22], which may increase 10-fold to 24 ms under load (Supplementary Analysis). Since cortexillin-I is essential for the mechanosensory response, we tested whether it remains bound to the actin for longer time-scales than the myosin motor domain does. Previous FRAP studies indicated that cortexillin-I turns over on the 5-s time-scale [20]. However, in vivo FRAP may reflect multiple protein interactions. Therefore, we used a single molecule approach to directly test the lifetime of a single cortexillin-I-actin interaction (Fig. 4A). We purified GFP-cortexillin-I and measured the cortexillin-I-actin dwell-time distribution (Fig. 4B, C). We found that cortexillin-I bound a single actin filament with an average dwell time (τ) of 550 ms, which is up to 200-fold longer than the myosin motor-actin strongly bound state time.

Fig. 4.

Single molecule analysis of cortexillin-I-actin interactions. (A) Cartoon depicts the geometry of the experimental set up. GFP-cortexillin-I is anchored to the substrate through the GFP using anti-GFP antibodies. An actin dumbbell is steered into position using a dual beam optical trap. (B) An example trace showing the bead position (top) and the cross-correlation of the fluctuations of the two beads (bottom) holding the actin dumbbell. (C) Dwell time distribution showing the distribution of bound life-times. The mean τ is 550 ms (± 40 ms, n = 776 events). Errors are standard errors from fitting bootstrap sampled datasets.

RacE is the cell-cycle stage specificity factor

Previously, we showed that without extreme deformation this mechanosensory pathway was not active in wild type cells during interphase [2]. Because RacE presides over a pathway of global actin crosslinking proteins - dynacortin, enlazin and fimbrin -that control (resist) contractility dynamics during cytokinesis [20, 25, 26], we hypothesized that it might inhibit the mechanosensory pathway. We first confirmed that mitotic RacE mutant cells were mechanosensory. Indeed, RacE null cells accumulated GFP-myosin-II at the micropipette during cytokinesis (40% responses; n=5) (Fig. 5A). However, during interphase, 62% (n=37) of RacE null cells responded by accumulating GFP-myosin-II (Fig. 5B) and 41% (n=37) responded by accumulating GFP-cortexillin-I (Fig. 5C) at the micropipette. This effect was reversed (rescued) by expressing mCherry-RacE in these RacE null cells (10%; 2 out of 20 cells responded) (Fig. 5D). Thus, in wild type cells, RacE shields this mechanosensory system during interphase (see Discussion).

Fig. 5.

RacE is the cell cycle stage specificity factor that determines when myosin-II and cortexillin-I can redistribute in response to mechanical strain. Example time series (times in s) of DIC and fluorescence images are shown for (A) a mitotic RacE: GFP-myoII cell; (B) an interphase RacE: GFP-myoII cell; (C) an interphase RacE: GFP-cortI cell; and (D) an interphase RacE: mCh-RacE;GFP-myoII cell. Frequency histograms show measurements from all cells measured for each genotype. Scale bar, 10 µm.

Discussion

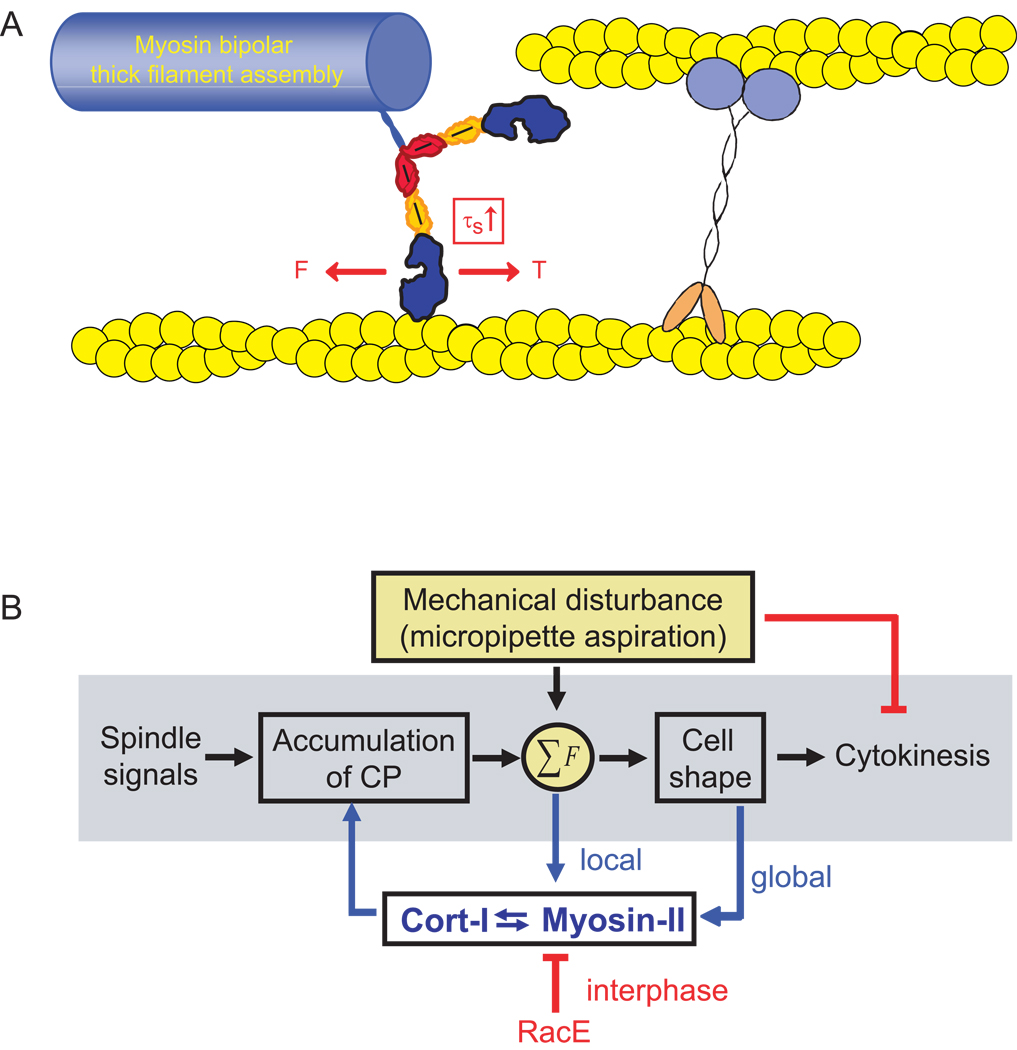

A feedback control system requires a sensor and a transducer. In the shape control system described here (Fig. 6), the cell responds to mechanical perturbations in order to correct the shape defect so that high fidelity (successful and symmetrical) cytokinesis may proceed. Myosin-II and cortexillin-I work as an ensemble to sense and respond to mechanical perturbation. Myosin-II is uniquely poised to be a sensor and a transducer since it naturally has load-dependent actin-binding steps. Limited by the energy available from ATP hydrolysis, myosins must respond to applied forces by either holding on to the actin filament (myosin-I and myosin-II), by back stepping (myosin-V) or by releasing from the actin track altogether [27]. However, for such a mechanism to operate, the actin filament itself must be anchored to the network in order for the myosin to generate enough tension to stall so that it dwells on the actin polymer. In this cytokinesis mechanosensory shape control system, cortexillin-I appears to be a key actin crosslinker that works in concert with myosin-II to respond to applied cellular deformation. Therefore, this study reveals that a cellular-scale mechanosensor requires three critical elements: the myosin motor domain with its active force transducer (myosin ATPase) and force amplifier (myosin lever arm), a force-sensitive element that allows myosin thick filament accumulation, and an actin crosslinker (cortexillin-I in this case) that stabilizes the actin filament so that tension may be generated (and therefore experienced) by the motor domain as it goes through its power stroke (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Mechanosensory cell shape control system. (A) Cartoon depicts the mechanical circuit between myosin-II and cortexillin-I that mediates mechanosensing. Because tension is required to balance the myosin power stroke, which generates a force (F) on the actin filament, cortexillin-I likely anchors the actin filament, providing the tension (T) needed to increase the strongly bound state time (τs). This cross-communication between myosin-II and cortexillin-I stabilizes each protein on the actin, promoting their accumulation. This stabilization also appears to provide feedback on myosin-II thick filament assembly, allowing thick filaments to form, a requisite for accumulation. (B) This mechanosensory system ensures successful high fidelity cytokinesis. Mechanical perturbation halts cytokinesis during early stages of cytokinesis and triggers accumulation of myosin-II and cortexillin-I to the site of mechanical deformation during all stages of cytokinesis. Cooperative interactions between myosin-II and cortexillin-I define the cellular-scale mechanosensor.

The lever arm tunes the pressure-threshold dependency of the response. From recent single molecule studies, myosin-I and myosin-II move through sub-steps with different load sensitivities as they translocate along the actin filament [9, 11]. Complete transition through the sub-steps is required for ADP to be released, allowing ATP to bind so that the motor can release from the track. By varying the lever arm length, we were able to tune the pressure-threshold dependency of the cell’s response. Similar to the single molecule assays, our observations suggest that the mechanical stress that we apply to the cortex leads to strain on the myosin lever arm, preventing the motor from undergoing its full working stroke and locking the motor onto the filament for a longer period of time. Due to the longer lever arm (assuming the lever arm is a rigid rod and Fmax ∝ (lever arm length)−1; [21]), 2xELC (est. Fmax = 2 pN) should require lower overall forces to strain the lever arm than the wild type motor (Fmax = 3 pN; [21]); consistently, it required less pressure to accumulate at the micropipette. In contrast, the short lever arm mutant ΔBLCBS (est. Fmax = 14 pN) was much less sensitive and did not reach full wild type mechanosensory response levels within the available pressure range for these experiments. This is consistent with the idea that a shorter lever arm requires greater forces to stall the motor. Because of its very short unloaded strongly bound state time (τs), it has not been feasible to measure the load dependency of τs for Dictyostelium myosin-II. However, by comparing the active radial stress that we attribute to the cleavage furrow cortex during furrow ingression [26], the concentration of myosin-II at the furrow cortex [15], and the pressure dependency of the mechanical response (this paper), estimates indicate that myosin-II may undergo a 5–10-fold increase in duty ratio under mechanical stress (Supplementary Analysis). This is within range of the 5–12-fold increase in duty ratio for other myosin-IIs [8]. One alternative hypothesis is that 2xELC achieves greater mechanosensitivity because it has a higher actin-activated ATPase activity that is insensitive to RLC phosphorylation (ie. 2xELC is an unregulated motor, which behaves more similarly to RLC-phosphorylated wild type myosin-II). However, we disfavor this possibility because ΔABLCBS is similarly unregulated [21] but is significantly less mechanosensitive. Another alternative hypothesis is that the mechanosensory responsiveness is simply due to differences in the unloaded velocities of the different motors (wild type: 3 µm/s, 2xELC: 4 µm/s, and ΔBLCBS: 0.6 µm/s; [21]). However, we disfavor this hypothesis since the 10-fold slower S456L myosin-II (0.2 µm/s; [22]) was more responsive than the 5-fold slower ΔBLCBS mutant. S456L achieves its reduced unloaded velocity through a 3-fold longer ADP-bound state and a ¼ normal step size [22]. While the S456L protein undoubtedly undergoes its complete conformational change, without load it likely releases prematurely, yielding a fractional productive step. Thus, our observations suggest that loading this motor restores its ability to lock onto the actin filaments. These observations are consistent with in vivo mechanical data on interphase and dividing cells [20]. During interphase, cells expressing S456L have mechanical properties intermediate between wild type and myoII null cells. However, during cytokinesis, the S456L mutant fully restores cell mechanics and cytokinesis furrow ingression dynamics to wild type levels, suggesting that the mechanical stress in the dividing cell allows the S456L myosin-II to function like a wild type motor.

The mechanosensory system is likely to be highly cooperative. Based on our data, we find that elements of myosin mechanochemistry (full ATPase activity, regulatory light chain phosphorylation, and lever arm) as well as bipolar thick filament assembly dynamics are required for the response. Thick filament assembly requires a nucleation step and is delicately balanced by small electrostatic charge differences just downstream of the assembly domain [17, 28]. Our observations suggest that as mechanical stress locks the myosin-II motor onto actin, it promotes the formation of bipolar thick filaments. Simulations indicate that a potential force-sensitive step could in fact be in the transition between assembly incompetent and competent states (Supplementary Analysis). Further, cortexillin-I accumulates directly in a myosin-II activity dependent manner. Cortexillin-I responds co-temporally with myosin-II, S456L only partially restores cortexillin-I recruitment consistent with S456L’s weak activity, and cortexillin-I accumulates in interphase RacE mutants similar to myosin-II. We suggest that mechanical stress in the cortical actin network stabilizes myosin-II and cortexillin-I, allowing both to accumulate in a cooperative fashion.

This study has other important implications for both cellular mechanosensing and cell shape control. The global cortex has increased mechanical deformability during cytokinesis as compared to interphase [20], and we now find that the Rac-family small GTPase RacE determines the cell cycle specificity of the mechanosensory nature of the cortex (Fig. 5B). This Rac acts as an inhibitor of cytokinesis contractility [26]. As RacE is required for cortical tension and maintenance of other actin crosslinkers in the cortex ([20, 25] and references therein), RacE controls mechanical resistance. Given the fluid nature of RacE null cells [26], its presence in wild type cells may make the cortex more elastic (solid-like) so that the mechanical stress is absorbed by the crosslinked network. During wild type cell division (or in interphase RacE null cells), the cortical network becomes more deformable so that the myosin-II/cortexillin-I sensor now bears the mechanical stress, directing these proteins’ accumulation at sites of shape deformation.

In addition to the shape control system, the cooperative interactions between myosin-II and cortexillin-I undoubtedly drive contractility at the cleavage furrow cortex. Null mutants in either gene have similarly altered cleavage furrow morphology, asymmetry in daughter cell sizes, and similar furrow ingression dynamics [2, 20, 26, 29]. The fact that neither protein requires the other for localization to the cleavage furrow cortex highlights that there are multiple pathways that direct their localization. Once myosin-II and cortexillin accumulate at the furrow cortex, myosin-II motors likely pull against cortexillin-I generating contractile stress in the actin network to help drive cleavage furrow constriction. In other scenarios, other crosslinkers or combinations of crosslinkers may also interact cooperatively with myosin-II in a similar manner as cortexillin-I does here.

In sum, this study reveals that myosin-II mediates cellular-scale mechanosensing in nonmuscle cells to monitor and correct cell shape changes during cytokinesis. As Dictyostelium are protozoans with numerous features similar to human cells, this mechanosensory system likely reflects an early requirement for cells to feel and respond to mechanical inputs from their environment and to monitor shape change progression during cell division. Myosin-II may have evolved some of its mechanosensitive enzymatic steps in this context. Mechanosensitive myosin-dependent processes like hearing, muscle contraction, and cardiovascular function are undoubtedly late evolutionary beneficiaries of this cellular-scale mechanosensory module.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Strains

Dictyostelium discoideum strains and plasmids are described in full in the Supplementary Experimental Procedures and Table S1.

Micropipette Aspiration

Micropipette aspiration experiments were performed as previously described [2]. In short, micropipettes were pulled to an inner radius, ranging from 2–3 µm. Using a motorized water manometer system, aspiration pressure was applied to the surface of the cell. To quantify responses, the fluorescent signal intensities (after background subtraction) of the cortex inside the pipette (Ip) and outside the pipette at the opposite cortex (Io) were measured. Ratios of Ip/Io greater than 1.39 (log(Ip/Io) = 0.14, which is two standard deviations above the wild type interphase mean (as defined in [2]), were considered positive responses. In the frequency histograms, the positive responses are colored dark grey while negative responses are colored light grey. To determine standard errors for the fraction of responses (for Fig. 1D), we used SE = √(f(1-f)/n) where f is the fraction of responses and n is the sample size. We also analyzed the entire histograms for overall mean and standard errors for statistical testing (Student’s t-test). This approach does not require any additional assumptions about the responses, and we find that using both types of analyses provides a more complete picture of the data. Finally, particularly for the lever arm length and S456L mutants, we analyzed and compared the total signal intensities of the aspirated cells prior to aspiration to confirm that the exact cells analyzed had comparable (statistically identical) expression levels. Similar expression levels for each protein were generally the case across all of the strains studied.

Single molecule analysis

His-tagged GFP-cortexillin-I was expressed and purified to homogeneity from E. coli using polyethyleneimine and ammonium sulfate cuts followed by Ni2+-NTA, size exclusion and mono S column chromatography. The purified protein was tested in actin high-speed co-sedimentation assays, confirming that it saturated actin with the expected one mole of cortexillin-I dimer per four actins (data not shown) [30]. The GFP-cortexillin-I was then anchored to a platform bead using anti-GFP monoclonal antibody (QBiogene, 3E6). Neutravidin-coated 1-µm biotinylated polystyrene beads (Molecular Probes) were attached to the ends of actin filaments assembled with 10% biotin-labeled actin monomers, creating actin dumbbells. An actin dumbbell was steered with a dual-beam optical trap using acousto-optic modulators over individual platform beads in search of platforms that interacted with the actin filament. The positions of both beads of the actin dumbbell and their cross-correlation were monitored. Cortexillin-I-actin interactions were determined by a decrease in the cross-correlated fluctuations of the two beads. Binding lifetimes were measured and plotted. The distributions largely fit a single exponential from which the cortexillin-I-binding lifetime was determined. The probability that binding events were the result of two cortexillin molecules, instead of one, is ~4 %. The buffer used for these assays contains 25 mM KCl, 25 mM imidazole•HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EGTA, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.086 mg/mL glucose oxidase, 0.014 mg/mL catalase, 0.09 mg/mL glucose and 1 mM DTT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Dictyostelium stock center for the RLC mutant strains and James Spudich for the 3xAla and 3xAsp constructs. We thank Sue Craig, Rob Jensen, and Carolyn Machamer for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by ACS grant RSG CCG-114122 (to D.N.R.), NIH grants GM066817 (to D.N.R.) and GM078450 (to R.S.R), and NSF grant CCF 0621740 (to P.A.I. and D.N.R.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Orr AW, Helmke BP, Blackman BR, Schwartz MA. Mechanisms of mechanotransduction. Dev. Cell. 2006;10:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Effler JC, Kee Y-S, Berk JM, Tran MN, Iglesias PA, Robinson DN. Mitosis-specific mechanosensing and contractile protein redistribution control cell shape. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1962–1967. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinac B. Mechanosensitive ion channels: molecules of mechanotransduction. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:2449–2460. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balaban NQ, Schwartz US, Riveline D, Goichberg P, Tzur G, Sabanay I, Mahalu D, Safran S, Bershadsky AD, Addadi L, Geiger B. Force and focal adhesion assembly: a close relationship studied using elastic micropatterned substrates. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:466–472. doi: 10.1038/35074532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedland JC, Lee MH, Boettiger D. Mechanically activated integrin switch controls a5b1 function. Science. 2009;323:642–644. doi: 10.1126/science.1168441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.del Rio A, Perez-Jimenez R, Liu R, Roca-Cusachs P, Fernandez JM, Sheetz MP. Stretching single talin rod molecules activates vinculin binding. Science. 2009;323:638–641. doi: 10.1126/science.1162912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kovacs M, Thirumurugan K, Knight PJ, Sellers JR. Load-dependent mechanism of nonmuscle myosin 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:9994–9999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701181104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veigel C, Molloy JE, Schmitz S, Kendrick-Jones J. Load-dependent kinetics of force production by smooth muscle myosin measured with optical tweezers. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:980–986. doi: 10.1038/ncb1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altman D, Sweeney HL, Spudich JA. The mechanism of myosin VI translocation and its load-induced anchoring. Cell. 2004;116:737–749. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laakso JM, Lewis JH, Shuman H, Ostap EM. Myosin I can act as a molecular force sensor. Science. 2008;321:133–136. doi: 10.1126/science.1159419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillespie PG, Cyr JL. Myosin-1c the hair cell's adaptation motor. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2004;66:521–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.112842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford LE, Huxley AF, Simmons RM. Tension transients during steady shortening of frog muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 1985;361:131–150. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabry JH, Moores SL, Ryan S, Zang J-H, Spudich JA. Myosin heavy chain phosphorylation sites regulate myosin localization during cytokinesis in live cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1997;8:2647–2657. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.12.2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson DN, Cavet G, Warrick HM, Spudich JA. Quantitation of the distribution and flux of myosin-II during cytokinesis. BMC Cell Biology. 2002;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shu S, Liu X, Korn ED. Dictyostelium and Acanthamoeba myosin II assembly domains go to the cleavage furrow of Dictyostelium myosin II-null cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:6499–6504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0732155100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hostetter D, Rice S, Dean S, Altman D, McMahon PM, Sutton S, Tripathy A, Spudich JA. Dictyostelium myosin bipolar thick filament formation: importance of charge and specific domains of the myosin rod. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen P, Ostrow BD, Tafuri SR, Chisholm RL. Targeted disruption of the Dictyostelium RMLC gene produces cells defective in cytokinesis and development. J. Cell Biol. 1994;127:1933–1944. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zang J-H, Cavet G, Sabry JH, Wagner P, Moores SL, Spudich JA. On the role of myosin-II in cytokinesis: Division of Dictyostelium cells under adhesive and nonadhesive conditions. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1997;8:2617–2629. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.12.2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reichl EM, Ren Y, Morphew MK, Delannoy M, Effler JC, Girard KD, Divi S, Iglesias PA, Kuo SC, Robinson DN. Interactions between myosin and actin crosslinkers control cytokinesis contractility dynamics and mechanics. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:471–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uyeda TQ, Abramson PD, Spudich JA. The neck region of the myosin motor domain acts as a lever arm to generate movement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:4459–4464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy CT, Rock RS, Spudich JA. A myosin II mutation uncouples ATPase activity from motility and shortens step size. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:311–315. doi: 10.1038/35060110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girard KD, Kuo SC, Robinson DN. Dictyostelium myosin-II mechanochemistry promotes active behavior of the cortex on long time-scales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2103–2108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508819103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stock A, Steinmetz MO, Janmey PA, Aebi U, Gerisch G, Kammerer RA, Weber I, Faix J. Domain analysis of cortexillin I: actin-bundling PIP2-binding and the rescue of cytokinesis. EMBO J. 1999;18:5274–5284. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson DN, Spudich JA. Dynacortin, a genetic link between equatorial contractility and global shape control discovered by library complementation of a Dictyostelium discoideum cytokinesis mutant. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:823–838. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.4.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang W, Robinson DN. Balance of actively generated contractile and resistive forces controls cytokinesis dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:7186–7191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502545102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kee Y-S, Robinson DN. Motor proteins: myosin mechanosensors. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:R860–R862. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moores SL, Spudich JA. Conditional Loss-of-Myosin-II-Function Mutants Reveal a Position in the Tail that Is Critical for Filament Nucleation. Mol. Cell. 1998;1:1043–1050. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Girard KD, Chaney C, Delannoy M, Kuo SC, Robinson DN. Dynacortin contributes to cortical viscoelasticity and helps define the shape changes of cytokinesis. EMBO J. 2004;23:1536–1546. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faix J, Steinmetz M, Boves H, Kammerer RA, Lottspeich F, Mintert U, Murphy J, Stock A, Aebi U, Gerisch G. Cortexillins, major determinants of cell shape and size, are actin-bundling proteins with a parallel coiled-coil tail. Cell. 1996;86:631–642. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.