Abstract

Background

Depression is common among older cancer patients, but little is known about the optimal approach to caring for this population. This analysis evaluates the effectiveness of the Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) program, a stepped care management program for depression in primary care patients who had an ICD-9 cancer diagnosis.

Methods

Two hundred fifteen cancer patients were identified from the 1,801 participants in the parent study. Subjects were 60 years or older with major depression (18%), dysthymic disorder (33%), or both (49%), recruited from 18 primary care clinics belonging to 8 health-care organizations in 5 states. Patients were randomly assigned to the IMPACT intervention (n = 112) or usual care (n = 103). Intervention patients had access for up to 12 months to a depression care manager who was supervised by a psychiatrist and a primary care provider and who offered education, care management, support of antidepressant management, and brief, structured psychosocial interventions including behavioral activation and problem-solving treatment.

Results

At 6 and 12 months, 55% and 39% of intervention patients had a 50% or greater reduction in depressive symptoms (SCL-20) from baseline compared to 34% and 20% of usual care participants (P = 0.003 and P = 0.029). Intervention patients also experienced greater remission rates (P = 0.031), more depression-free days (P < 0.001), less functional impairment (P = 0.011), and greater quality of life (P = 0.039) at 12 months than usual care participants.

Conclusions

The IMPACT collaborative care program appears to be feasible and effective for depression among older cancer patients in diverse primary care settings.

KEY WORDS: depression, cancer, treatment, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

The majority of cancer patients in the United States are 65 years and older.1 Seventy-seven percent of all cancers are diagnosed in persons 55 years or older. Among those without a prior cancer diagnosis, 16% of males and 10% of females will develop cancer between 60–69 years old and 39% of males and 26% of females will develop cancer between 70–79 years old.2 Rates of clinically significant depression are as high as 25% in older adults,3,4 well above the general population.5 Despite the large number of older adults with cancer and depression, there are few studies examining treatment strategies for depression in this population.

Depression has a substantial impact on health in patients with comorbid medical conditions6 and is associated with increased symptom burden (e.g., pain, fatigue), decreased cognitive and physical functioning, decreased quality of life, impaired family functioning, decreased adherence to medical regimens and healthy behaviors, and potentially decreased immunity and increased mortality.7 Recent comprehensive reports show that depression often goes undetected and untreated in cancer patients.8,9

Despite calls from the National Cancer Institute10 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network11 for systematic detection and treatment of depression in cancer patients, and the availability of evidence-based treatments for depression,12–16 many depressed cancer patients do not receive effective treatment.17,18 This gap in care is in part due to the lack of a system of care for depression that can be adapted into oncology clinics and other settings caring for patients with chronic medical illnesses.19

Oncologists do not consistently identify which of their patients are depressed,17 and there is little evidence that this ability is improved by training alone.20 Cancer patients are often reluctant to seek help for psychiatric illness.21,22 Even if depression is detected, there are further obstacles to the initiation of effective treatment,23 including: (1) depression being regarded as a normal reaction to cancer; (2) the stigma of a psychiatric diagnosis; (3) reluctance by doctors to give or by patients to accept treatments that are seen as psychiatric vs. medical; (4) failure to maintain an active focus on depression and to adjust treatment if it is not effective; and (5) limited access to mental health care. Once treatment is initiated, close monitoring and treatment adjustment are critical, especially since studies have shown that response and tolerability to antidepressant treatment in elderly depressed patients may be lower than in younger patients.24 Depression screening alone, without a system of care that can effectively engage patients and treat depression, has shown minimal effects on improving depression outcomes in medical settings.25–28 Elderly cancer patients may have additional barriers to care, such as transportation, financial, lack of caregiver support, a belief that depression is a normal part of aging,29 and having low rates of depression care compared to younger patients.30

Reorganizing the way medical and mental health professionals work together by means of a Collaborative Care model has been found to significantly improve depression outcomes in primary care.31 The core features of Collaborative Care include active care management, support of medication management prescribed by primary care providers, and mental health specialty consultation and back-up. No studies have reported on the effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in primary care patients with cancer.

This study examines the effectiveness of a collaborative care program for depression in a cohort of patients with cancer from Project IMPACT, a multi-site study of collaborative care for depression in older primary care patients32; www.impact-uw.org. Project IMPACT enrolled 1,801 depressed older adults age ≥60, with an average of three medical comorbidities. Participants were sociodemographically diverse and included 65% women and 23% ethnic minorities.32,33 We hypothesized that cancer patients enrolled in IMPACT would also have significantly better 12-month depression outcomes compared with usual care, although the effect would be slightly less than for the overall study sample.

METHODS

The IMPACT trial was conducted in 18 primary care clinics at 8 diverse health-care organizations across the US from 1999 to 2001.32 Institutional review boards for each organization and the study coordinating center approved the study procedures, and all participants provided written informed consent. Detailed information on this trial is provided elsewhere.32,34

Inclusion criteria were 60 years or older, current major depression or dysthymia (chronic depression) diagnosed by the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV),35 and plans to use one of the participating clinics as the main source of general medical services for the coming year. Exclusions included history of bipolar disorder or psychosis, ongoing treatment by a psychiatrist, current alcohol use problems,36 severe cognitive impairment,37 or acute risk of suicide.

For the analyses reported in this article, we focus on the 215 participants who had an ICD-938 diagnosis of non-skin cancer in claims or encounter data in the year before or the year following randomization. These patients were randomly assigned to the IMPACT intervention (n = 112) or usual care (n = 103). The following ICD-9 codes were used to categorize cancer diagnoses: digestive system (150.0–159.9), respiratory system (160.0–163.9, 165.0–165.9), female breast (174.0–174.9), female reproductive (179.0–184.9), male reproductive (185.0–187.9), urinary system (188.0–189.9), occult (195.0–199.9), hematologic (200.0–208.9), and other (includes oral cavity and pharynx, bones and joints, soft tissues, male breast, eye and orbit, brain, thyroid and other endocrine: 140.0–149.9, 170.0–171.9, 175.0–175.9, 190.0–194.9).39

There were also 105 participants who reported a diagnosis or treatment for cancer in the 3 years before study initiation; 75 of these were also among the aforementioned 215 subjects. We used this cohort of patients who self-reported cancer to perform a secondary confirmatory analysis.

Intervention

Intervention patients were offered depression management by a depression care manager (DCM; a nurse or clinical psychologist) working collaboratively with the patient and primary care physician in the patient’s usual primary care clinic for up to 12 months. The DCM conducted a psychosocial history, provided education and behavioral activation (which emphasizes pleasant event scheduling and overcoming avoidance behaviors), and helped patients identify treatment preferences. Treatment options included antidepressant medicines prescribed by the patients' primary care clinicians and a structured six- to eight-session psychotherapy program known as Problem-Solving Treatment (PST) in Primary Care delivered by the DCM.40 A stepped-care pharmacotherapy algorithm34 recommending routinely available antidepressant medications guided the acute and follow-up phases of treatment over 12 months. The DCM met weekly with a supervising psychiatrist and an expert primary care physician (PCP) to monitor clinical progress and adjust treatment plans accordingly. In-person or telephone follow-up visits occurred about every 2 weeks during acute-phase treatment, with subsequent monthly contact during continuation and maintenance phases. The intervention did not include routine assessment or treatment of cancer-related issues, although patients could choose to address cancer-related problems in PST sessions. Patients assigned to the usual care group and their PCPs were told that the patient met research diagnostic criteria for clinical depression and received routinely available depression treatment, including antidepressants and referrals to specialty mental health services as deemed necessary by the attending physician or patient. All study participants were followed in usual care for an additional year after the initial 12 months.

Outcome Measures

Baseline, 3-, 6-, 12-, 18-, and 24-month follow-up data were collected by trained research staff blind to treatment assignment. A 20-item depression severity scale adapted from the Symptom Checklist (SCL-20) was used to assess depression severity and thoughts of death or suicide.41 Depression treatment response was measured by a 50% or greater reduction in SCL-20 score and remission was defined by a score of <0.5. Depression-free days were estimated following the method developed by Lave and colleagues42 using the SCL-20. A score of 0.5 or less on the SCL-20 was used to indicate a full depression-free day and a score of 1.7 or more was used to indicate a 0 depression-free day. Intermediate severity scores were assigned a value between 0 and 1 by linear interpolation. Estimates were then summed to yield the total depression-free days during 12- and 24-month follow-up periods. Use of mental health services and antidepressants, and satisfaction with depression care were also assessed. An item from the SCL-20 was used to assess energy and fatigue. Respondents also rated their health-related quality of life in the past month on a scale from 0 to 10. Respondents were instructed to choose 0 if they felt their situation was about as bad as dying or 10 if they felt in perfect health. The Sheehan Disability Scale was used to assess health-related impairments in work, family, and social functioning.43

Statistical Analysis

We examined descriptive statistics for demographic and baseline characteristics and compared intervention and usual care groups using logistic regression models with randomized assignment as the dependent variable. For each outcome variable, we made cross-sectional comparisons between the two study groups at each follow-up time point using logistic regression models. We also conducted a repeated measures intent-to-treat analysis on baseline, 6-, and 12-month data using mixed models for continuous variables and GEE method for dichotomous variables. All models were adjusted for time, recruitment method, and site. Due to the small sample size, we did not test the interaction effect between time and intervention. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Since the data were previously imputed, we conducted all analyses on the five multiply imputed data sets using the SAS PROC Mianalyze procedure. Descriptive statistics were derived by combining the results from the five imputed data sets following Rubin’s rule.44

RESULTS

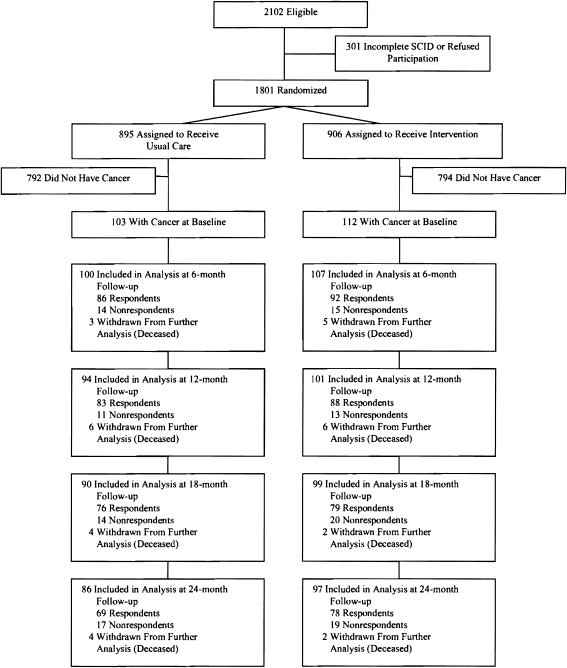

Figure 1 describes the enrollment process for the IMPACT trial. Two hundred fifteen (11.9%) of the 1,801 participants had an ICD-9 diagnosis of cancer in the 12 months before or after randomization. Intervention and control group comparisons (Table 1) showed no significant differences in clinical or demographic characteristics at baseline (P > 0.05), with the exception of mental health service use in the past 3 months (14% in the intervention group vs. 2% in the usual care group, P = 0.005). The mean number of comorbid chronic physical illnesses, selected from a list of nine common medical conditions (cancer excluded), was 3.28 (SD 0.11). Half of the participants met diagnostic criteria for current major depression and dysthymic disorder. Female breast and male reproductive (mostly prostate) cancers were the most common cancer diagnoses, followed by occult and digestive cancers (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of IMPACT trial. IMPACT indicates Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Analyses included all other participants after multiple imputation of unit-level missing data.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics of Subjects Who Have Cancer Diagnoses by ICD-9 (Excluding Skin Cancer)

| Variable | Category | All cancer patients (N = 215) | Intervention (N = 112) | Usual care (N = 103) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 130 (60%) | 70 (63%) | 60 (58%) | 0.525 | |

| Age | Mean (SE) | 71.75 (0.50) | 71.73 (0.70) | 71.78 (0.71) | 0.964 |

| Married or living with partners | 96 (45%) | 44 (39%) | 52 (50%) | 0.100 | |

| Ethnic minority | 53 (25%) | 25 (22%) | 28 (27%) | 0.409 | |

| At least high school graduate | 173 (80%) | 93 (83%) | 80 (78%) | 0.323 | |

| Medicare coverage | 175 (81%) | 89 (79%) | 86 (83%) | 0.449 | |

| Prescription medication coverage | 199 (93%) | 103 (92%) | 96 (93%) | 0.730 | |

| Cancer diagnosis | Female breast | 63 (29%) | 40 (36%) | 23 (22%) | 0.032 |

| Male reproductive | 50 (23%) | 27 (24%) | 23 (22%) | 0.758 | |

| Occult | 27 (13%) | 14 (13%) | 13 (13%) | 0.979 | |

| Digestive system | 26 (12%) | 10 (9%) | 16 (16%) | 0.142 | |

| Urinary system | 21 (10%) | 9 (8%) | 12 (12%) | 0.375 | |

| Hematologic | 21 (10%) | 11 (!0%) | 10 (10%) | 0.978 | |

| Female reproductive | 19 (9%) | 10 (9%) | 9 (9%) | 0.961 | |

| Other * | 18 (8%) | 10 (9%) | 8 (8%) | 0.759 | |

| Respiratory system | 16 (7%) | 9 (8%) | 7 (8%) | 0.730 | |

| Number of cancer types | 1 | 176 (82%) | 89 (79%) | 87 (84%) | 0.257 |

| 2 | 32 (15%) | 18 (16%) | 14 (14%) | ||

| 3 | 7 (3%) | 5 (4%) | 2 (2%) | ||

| Depression status (SCID) | Major depression | 39 (18%) | 24 (21%) | 15 (15%) | 0.379 |

| Dysthymia | 70 (33%) | 34 (30%) | 36 (35%) | ||

| Both | 106 (49%) | 54 (48%) | 52 (50%) | ||

| 2+ prior episodes of depression | 150 (70%) | 81 (72%) | 69 (67%) | 0.432 | |

| Treatment preferences | Antidepressant | 62 (29%) | 29 (26%) | 33 (32%) | 0.698 |

| Psychotherapy | 127 (59%) | 70 (62%) | 57 (56%) | ||

| Neither | 8 (4%) | 5 (4%) | 3 (3%) | ||

| No preference | 18 (8%) | 8 (7%) | 9 (9%) | ||

| Positive on cognitive impairment screener | 78 (36%) | 44 (39%) | 34 (33%) | 0.356 | |

| Positive on anxiety screener | 66 (31%) | 37 (33%) | 29 (28%) | 0.439 | |

| Chronic disease count (0–9) | Mean (SE) | 3.28 (0.11) | 3.23 (0.16) | 3.33 (0.16) | 0.665 |

| Significant chronic pain | 116 (54%) | 62 (55%) | 54 (52%) | 0.647 |

ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision

*Includes oral cavity and pharynx, bones and joints, soft tissues, male breast, eye and orbit, brain, thyroid and other endocrine cancers

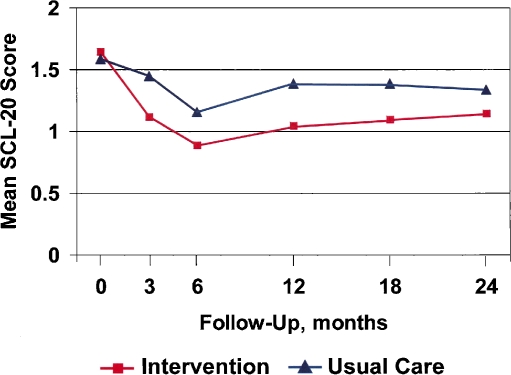

Figure 2.

SCL-20 depression scores in subjects who have cancer diagnoses by ICD-9 (excluding skin cancer), N = 215. SCL-20 indicates a 20-item depression severity scale adapted from the Hopkins Symptom Checklist. For depression, P < 0.01 for the comparisons between usual care and intervention groups at 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up; P = 0.49 at 0 months, 0.01 at 18 months, and 0.09 at 24 months.

Depression Treatment and Outcomes

Depression treatment (pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy) increased for both intervention and usual care groups over the 12-month intervention (Table 2). Antidepressant use and specialty mental health counseling or psychotherapy was significantly greater among intervention than usual care patients. These increases in treatment were similar to findings in the overall study sample.32 Intervention patients were about twice as likely as those receiving usual care to experience a depression treatment response at 12 months (39% vs. 20%; P = 0.029). Remission rates were higher in the intervention group at 6 months (P = 0.006) and at 12 months (P = 0.031). Intervention patients reported more depression-free days compared with the usual care group in the first year [185.8 (10.9) vs. 135.0 (10.2); P < 0.001] and a higher proportion of patients reported at 12 months that their satisfaction with depression care was ‘good or excellent’ (93% vs. 74%; P = 0.015). Thoughts of ending one’s life decreased in the intervention group, but increased in the usual care group.

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis of Depression and Functional Outcomes by Group Assignment in Subjects Who Have Cancer Diagnoses by ICD-9 (Excluding Skin Cancer)

| Variable | Time point | Cancer patients (N = 215) | Intervention (N = 112) | Usual care (N = 103) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCL-20 | Baseline | 1.62 (0.04) | 1.65 (0.06) | 1.59 (0.06) | 0.487 |

| 3 months | 1.28 (0.05) | 1.12 (0.07) | 1.45 (0.07) | 0.006 | |

| 6 months | 1.02 (0.06) | 0.89 (0.07) | 1.16 (0.08) | 0.008 | |

| 12 months | 1.22 (0.05) | 1.05 (0.07) | 1.39 (0.07) | 0.004 | |

| 18 months | 1.24 (0.06) | 1.10 (0.08) | 1.39 (0.07) | 0.012 | |

| 24 months | 1.24 (0.06) | 1.15 (0.08) | 1.34 (0.08) | 0.087 | |

| Response (≥50% improvement in SCL-20) | 3 months | 53 (25%) | 38 (35%) | 15 (15%) | 0.007 |

| 6 months | 93 (45%) | 59 (55%) | 34 (34%) | 0.003 | |

| 12 months | 58 (30%) | 39 (39%) | 19 (20%) | 0.029 | |

| 18 months | 54 (29%) | 38 (39%) | 16 (18%) | 0.012 | |

| 24 months | 46 (25%) | 30 (31%) | 16 (19%) | 0.088 | |

| Remission (SCL-20 <0.5) | 3 months | 25 (12%) | 18 (17%) | 6 (6%) | 0.059 |

| 6 months | 49 (24%) | 34 (32%) | 15 (15%) | 0.006 | |

| 12 months | 31 (16%) | 22 (22%) | 9 (9%) | 0.031 | |

| 18 months | 26 (14%) | 18 (19%) | 7 (8%) | 0.053 | |

| 24 months | 23 (13%) | 17 (18%) | 6 (7%) | 0.087 | |

| Antidepressant use in the past 3 months | Baseline | 92 (43%) | 55 (49%) | 37 (36%) | 0.052 |

| 3 months | 118 (56%) | 73 (67%) | 44 (44%) | 0.002 | |

| 6 months | 116 (56%) | 68 (64%) | 48 (48%) | 0.036 | |

| 12 months | 110 (57%) | 68 (67%) | 42 (45%) | 0.010 | |

| 18 months | 91 (48%) | 55 (56%) | 36 (40%) | 0.041 | |

| 24 months | 84 (46%) | 50 (52%) | 34 (39%) | 0.121 | |

| Any mental health visit in the past 3 months | Baseline | 18 (8%) | 16 (14%) | 2 (2%) | 0.005 |

| 3 months | 66 (31%) | 48 (43%) | 18 (18%) | <0.001 | |

| 6 months | 58 (28%) | 43 (40%) | 15 (15%) | <0.001 | |

| 12 months | 57 (29%) | 42 (42%) | 15 (16%) | <0.001 | |

| 18 months | 26 (14%) | 15 (15%) | 11 (12%) | 0.561 | |

| 24 months | 27 (15%) | 17 (17%) | 11 (12%) | 0.386 | |

| Satisfaction with depression care | Baseline | 35 (44%) | 21 (42%) | 14 (47%) | 0.713 |

| 3 months | 115 (65%) | 80 (76%) | 35 (49%) | <0.001 | |

| 12 months | 128 (85%) | 82 (93%) | 46 (74%) | 0.015 | |

| 18 months | 64 (55%) | 36 (61%) | 28 (49%) | 0.209 | |

| 24 months | 57 (54%) | 33 (56%) | 24 (51%) | 0.684 | |

| Sheehan disability scale | Baseline | 4.85 (0.18) | 5.06 (0.26) | 4.63 (0.25) | 0.228 |

| 3 months | 4.10 (0.19) | 3.62 (0.27) | 4.64 (0.30) | 0.017 | |

| 6 months | 4.13 (0.22) | 3.92 (0.29) | 4.36 (0.30) | 0.266 | |

| 12 months | 4.34 (0.21) | 3.81 (0.28) | 4.91 (0.31) | 0.011 | |

| 18 months | 3.97 (0.20) | 3.69 (0.30) | 4.28 (0.29) | 0.185 | |

| 24 months | 4.10 (0.25) | 4.16 (0.37) | 4.03 (0.28) | 0.774 | |

| Quality of life | Baseline | 5.42 (0.15) | 5.39 (0.21) | 5.45 (0.20) | 0.855 |

| 3 months | 6.04 (0.17) | 6.33 (0.22) | 5.72 (0.26) | 0.081 | |

| 6 months | 6.03 (0.19) | 6.30 (0.25) | 5.74 (0.25) | 0.097 | |

| 12 months | 6.32 (0.16) | 6.67 (0.23) | 5.95 (0.24) | 0.039 | |

| 18 months | 5.86 (0.18) | 6.33 (0.25) | 5.35 (0.24) | 0.009 | |

| 24 months | 6.20 (0.19) | 6.51 (0.25) | 5.84 (0.29) | 0.117 | |

| Feeling low energy | Baseline | 2.56 (0.08) | 2.60 (0.10) | 2.51 (0.12) | 0.563 |

| 6 months | 1.84 (0.09) | 1.69 (0.12) | 2.00 (0.13) | 0.081 | |

| 12 months | 2.05 (0.09) | 1.82 (0.12) | 2.29 (0.12) | 0.006 | |

| 18 months | 2.16 (0.10) | 1.89 (0.14) | 2.46 (0.12) | 0.003 | |

| 24 months | 2.15 (0.10) | 2.03 (0.13) | 2.29 (0.14) | 0.179 |

ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; SCL-20, 20-item depression severity scale

Repeated measures analyses over 12 months showed that after adjusting for time, recruitment method, and site, the intervention was significantly associated with response (OR 2.69, 95% CI 1.54, 4.71), remission (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.51, 3.94), use of antidepressants (OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.45, 2.94), and mental health utilization (OR 4.48, 95% CI 2.80, 7.10).

To further validate our results, we performed similar analyses on the 105 patients who self-reported a cancer diagnosis or cancer treatment in the 3 years prior to randomization. Similar group differences in depression and secondary outcomes were found in this sub-sample (data not shown).

Functional and Quality of Life Outcomes

By 12 months, intervention patients reported significantly less health-related functional impairment and higher quality of life in the preceding month compared with usual care (Table 2). Ratings of energy level were significantly better in the intervention group than in usual care at 12 months.

Long-term Outcomes

Significant differences in depression treatment response rates persisted even at 18 months, 6 months after the end of the intervention (38% in intervention group vs. 16% in usual care; P = 0.012). Intervention patients continued to report more depression-free days compared with the usual care group in the 2nd year [356.5 (21.7) vs. 247.6 (19.6); P < 0.001]. Thoughts of ending one’s life remained slightly lower in the intervention than the usual care group. Intervention patients continued to report less health-related functional impairment and higher quality of life at 18- and 24-months than those in usual care, but these differences were not always statistically significant. Ratings of energy continued to be significantly better in the intervention group at 18, but not 24 months.

DISCUSSION

The IMPACT model of depression care was more effective than usual care in treating depression in older primary care patients with cancer and a mean of three comorbid conditions. Depression outcomes among cancer patients were generally similar to the overall IMPACT study sample, suggesting that cancer does not reduce the relative effectiveness of the program compared to usual care.32,45 Benefits from improved treatment of depression in patients with comorbid cancer and depression extended beyond reducing depressive symptoms to include improved functional outcomes and quality of life. Many of these benefits persisted beyond the 12-month intervention period into the subsequent year.

There are few data to guide clinicians regarding effective models of care for depressed elderly cancer patients in primary care. Findings from this secondary analysis of IMPACT data provide promising evidence that collaborative depression care may be a feasible and effective treatment model for depressed older adults with cancer and can help guide future treatment research for this population. Our finding that use of antidepressants and mental health services returned to near baseline levels by 24 months suggests adding a brief relapse prevention module during the 2nd year may be beneficial.

Energy level improved more in the intervention group than the usual care group, illustrating the importance of treating comorbid depression in patients with fatigue, a common symptom in cancer patients and survivors.46 Cancer patients have twice the rate of suicide compared with the general population, with older age at diagnosis conferring an additional risk.47 Accordingly, a decrease in thoughts of death in this cancer cohort’s intervention group was slightly less than in the overall sample’s,48 suggesting that thoughts of death and suicide may warrant particular attention in depressed cancer patients.

In an earlier British study, Strong and colleagues49 demonstrated the effectiveness of an oncology nurse-led collaborative care model with a younger, more female population in a cancer center. Ell and colleagues50 found 12 months of bilingual social worker-led collaborative care to be more effective than usual care for depression in low-income, predominantly female (85%) Hispanic cancer patients with probable major depression or dysthymia at a university-affiliated county cancer clinic. In this study, reliance on self-report without a confirmatory diagnostic interview for depression may have led to inclusion of some patients with minor depression and a high usual care response rate. There was also a high rate of dropouts (45.3%), particularly in patients with poor prognostic factors, raising some question of generalizability to older, lower functioning patients. However, this and an earlier smaller study51 increase optimism that depressed low-income ethnic minority patients may benefit from collaborative care within the cancer setting.

This is the first study of collaborative care for depressed older adults with cancer in primary care settings (as opposed to cancer centers).49,50 It also differs in its enrollment of a higher proportion of elderly, male, and chronically depressed and medically ill patients. Late-life depression is especially undetected and undertreated in men and members of racial and ethnic minority groups.5 Our study drew from 18 diverse primary care clinics in 8 health-care organizations in 5 states (including VA, HMO, university-based, and private practice clinics), establishing the IMPACT model as feasible and robust across a diverse set of clinic settings and socioeconomic groups. IMPACT also followed patients for 12 months after treatment was completed, illustrating the long-term benefits of the intervention.

Our study shows that effective depression care can be offered to depressed older adults with cancer in diverse primary care settings through evidence-based programs such as IMPACT. Cancer patients may especially benefit from collaborative care because they are often engaged in a multidisciplinary treatment environment that includes oncologists and other medical specialists, social workers, nutritionists, physical therapists, and sometimes psychologists or psychiatrists.

Several limitations warrant mentioning. Because this was a secondary analysis, cancer patients were not prospectively randomized to the study groups. Nevertheless, the groups were well-balanced in demographic and clinical characteristics. Although use of ICD-9 codes to ascertain cancer diagnoses has been shown to be valid, some misclassification may have occurred, such as with provisional diagnoses.52–54 Moreover, we did not have data on timing or staging of cancer diagnosis or type of cancer treatment received.

Multiple imputation was based on the assumption that the missing data were missing at random (MAR). If the missing mechanism was not missing at random (NMAR), then the yielded results are likely to be biased. Given the low rate of item-level missing in our data and the fact that the wave-level missing was unrelated to the depression outcomes, our analyses with the multiple imputed data appear to be appropriate. Some of the continuous outcomes do not seem to follow an exact normal distribution; however, a central limit theorem has shown that a large sample such as ours can adequately address this issue.

Future studies should test the delivery of collaborative depression care to cancer patients at various stages in treatment, including during the acute phase of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Studies should also test the feasibility and effectiveness of delivering the intervention in the cancer care setting vs. a primary care setting, using different intervention components (e.g., behavioral activation), adding treatment components that focus on additional symptoms such as cancer-related fatigue or pain,55 and intervening in populations with different cancer diagnoses and prognoses.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the John A. Hartford Foundation, the California Healthcare Foundation, the Hogg Foundation, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Cancer in Elderly People: Work-shop Proceedings. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007.

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2008. http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/2008CAFFfinalsecured.pdf.

- 3.Spoletini I, Gianni W, Repetto L, et al. Depression and cancer: an unexplored and unresolved emergent issue in elderly patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:143–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Kua J. The prevalence of psychological and psychiatric sequelae of cancer in the elderly—how much do we know? Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2005;34:250–6. [PubMed]

- 5.Unutzer J. Clinical practice. Late-life depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2269–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:851–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Evans DL, Charney DS, Lewis L, et al. Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:175–89. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Institute of Medicine. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. [PubMed]

- 9.Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004:57–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Patrick DL, Ferketich SL, Frame PS, et al. NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: symptom management in cancer: pain, depression, and fatigue. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1110–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Distress Management V.1 11/08/07; http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.asp Accessed April 8, 2009.

- 12.Gill D, Hatcher S. Antidepressants for depression in people with physical illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000:CD001312. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Williams S, Dale J. The effectiveness of treatment for depression/depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:372–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Mynors-Wallis LM, Gath DH, Lloyd-Thomas AR, Tomlinson D. Randomised controlled trial comparing problem solving treatment with amitriptyline and placebo for major depression in primary care. BMJ. 1995;310:441–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Felgoise SH, McClure KS, Houts PS. Project Genesis: assessing the efficacy of problem-solving therapy for distressed adult cancer patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:1036–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Roth AJ, Modi R. Psychiatric issues in older cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003;48:185–97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Fallowfield L, Ratcliffe D, Jenkins V, Saul J. Psychiatric morbidity and its recognition by doctors in patients with cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1011–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Passik SD, Dugan W, McDonald MV, Rosenfeld B, Theobald DE, Edgerton S. Oncologists' recognition of depression in their patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1594–600. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Von Korff M, Unutzer J, Katon W, Wells K. Improving care for depression in organized health care systems. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:530–1. [PubMed]

- 20.Merckaert I, Libert Y, Delvaux N, et al. Factors that influence physicians' detection of distress in patients with cancer: can a communication skills training program improve physicians' detection? Cancer. 2005;104:411–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Kadan-Lottick NS, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, Zhang B, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric disorders and mental health service use in patients with advanced cancer: a report from the coping with cancer study. Cancer. 2005;104:2872–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Pirl WF, Muriel A, Hwang V, et al. Screening for psychosocial distress: a national survey of oncologists. J Support Oncol. 2007;5:499–504. [PubMed]

- 23.Greenberg DB. Barriers to the treatment of depression in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004:127–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Sneed JR, Rutherford BR, Rindskopf D, Lane DT, Sackeim HA, Roose SP. Design makes a difference: a meta-analysis of antidepressant response rates in placebo-controlled versus comparator trials in late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Coyne JC, Thompson R, Palmer SC, Kagee A, Maunsell E. Should we screen for depression? Caveats and potential pitfalls. Appl Preventive Psychology. 2000;9:101–21. [DOI]

- 26.Gilbody SM, House AO, Sheldon TA. Routinely administered questionnaires for depression and anxiety: systematic review. BMJ. 2001;322:406–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Pignone MP, Gaynes BN, Rushton JL, et al. Screening for depression in adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:765–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Hirschfeld RM, Keller MB, Panico S, et al. The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA. 1997;277:333–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Sarkisian CA, Lee-Henderson MH, Mangione CM. Do depressed older adults who attribute depression to “old age” believe it is important to seek care? J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:1001–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Klap R, Unroe KT, Unutzer J. Caring for mental illness in the United States: a focus on older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:517–24. [PubMed]

- 31.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2428–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Unutzer J, Katon W, Williams JW Jr., et al. Improving primary care for depression in late life: the design of a multicenter randomized trial. Med Care. 2001;39:785–99. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.First MD, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). Clinical Version. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1996.

- 36.Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P. The CAGE questionnaire: validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131:1121–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40:771–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. Washington, D.C.: Public Health Service. US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1988.

- 39.Jones LE, Doebbeling CC. Suboptimal depression screening following cancer diagnosis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:547–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Mynors-Wallis LM, Gath DH, Day A, Baker F. Randomised controlled trial of problem solving treatment, antidepressant medication, and combined treatment for major depression in primary care. BMJ. 2000;320:26–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L. SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale–preliminary report. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1973;9:13–28. [PubMed]

- 42.Lave JR, Frank RG, Schulberg HC, Kamlet MS. Cost-effectiveness of treatments for major depression in primary care practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:645–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27:93–105. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Rubin D. Multiple Imputation for Non-response in Surveys. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1987.

- 45.Hunkeler EM, Katon W, Tang L, et al. Long term outcomes from the IMPACT randomised trial for depressed elderly patients in primary care. BMJ. 2006;332:259–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Nail LM. My get up and go got up and went: fatigue in people with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004:72–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Misono S, Weiss NS, Fann JR, Redman M, Yueh B. Incidence of suicide in persons with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4731–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Unutzer J, Tang L, Oishi S, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation in depressed older primary care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1550–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Strong V, Waters R, Hibberd C, et al. Management of depression for people with cancer (SMaRT oncology 1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;372:40–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, Quinn DI, Dwight-Johnson M, Lee PJ. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008; 26:4488–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Dwight-Johnson M, Ell K, Lee PJ. Can collaborative care address the needs of low-income Latinas with comorbid depression and cancer? Results from a randomized pilot study. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:224–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.McBean AM, Warren JL, Babish JD. Measuring the incidence of cancer in elderly Americans using Medicare claims data. Cancer. 1994;73:2417–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.McClish DK, Penberthy L, Whittemore M, et al. Ability of Medicare claims data and cancer registries to identify cancer cases and treatment. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:227–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Wang PS, Walker AM, Tsuang MT, Orav EJ, Levin R, Avorn J. Finding incident breast cancer cases through US claims data and a state cancer registry. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:257–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Fleishman SB. Treatment of symptom clusters: pain, depression, and fatigue. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004:119–23. [DOI] [PubMed]