Abstract

In addition to thymus-derived or natural T regulatory (nTreg) cells, a second subset of induced T regulatory (iTreg) cells arises de novo from conventional CD4+ T cells in the periphery. The function of iTreg cells in tolerance was examined in a CD45RBhighCD4+ T cell transfer model of colitis. In situ-generated iTreg cells were similar to nTreg cells in their capacity to suppress T cell proliferation in vitro and their absence in vivo accelerated bowel disease. Treatment with nTreg cells resolved the colitis, but only when iTreg cells were also present. Although iTreg cells required Foxp3 for suppressive activity and phenotypic stability, their gene expression profile was distinct from the established nTreg “genetic signature,” indicative of developmental and possibly mechanistic differences. These results identified a functional role for iTreg cells in vivo and demonstrated that both iTreg and nTreg cells can act in concert to maintain tolerance.

Mature CD4+ “conventional” T (Tconv)4 cells isolated from peripheral blood and lymphoid organs can be induced to express Foxp3 in vitro by T cell activation in the presence of TGF-β1 and IL-2 (1–4). This process is enhanced by retinoic acid and antagonized by IL-6 and IFN-γ. Foxp3+ “induced” regulatory T (iTreg) cells have suppressive function, as measured by their capacity to inhibit T cell proliferation in vitro and to inhibit the induction of experimental autoimmune disease. TGF-β1 also acts with IL-6 to induce a T cell-specific isoform of the retinoic acid-related orphan receptor-γ (RORγt), which is necessary for the development of proinflammatory Th17 cells. Foxp3 and RORγt can be expressed in the same cell population and therefore lie at a critical crossroad between inflammation and tolerance.

In TGF-β1 and conditional T cell-specific TGF-β receptor II knockout mice, a lethal lymphoproliferative autoimmune disease, similar to that seen in Foxp3 knockout mice, develops within the neonatal period (5–9). Although “natural” regulatory T (nTreg) cell development in the thymus appears normal, survival in the periphery is compromised (7–9). Furthermore, TGF-β deficiency may abrogate the conversion of Tconv cells into iTreg cells. These observations demonstrate an important role for TGF-β in maintaining the regulatory T (Treg) cell pool, but do not functionally discriminate between the two types of Treg cells.

Recent studies have examined the in situ generation of iTreg cells under a variety of different conditions. Chronic exposure to systemically delivered submitogenic amounts of agonistic peptides or T cell expansion in a lymphopenic environment results in Foxp3 expression in up to 15% of Ag-experienced Tconv cells. These cells have the capacity to suppress T cell proliferation (10–13). However, studies in diabetic NOD mice with a high frequency of self-reactive T cells showed little overlap in the Tconv and nTreg cell TCR pools, suggesting peripheral conversion plays a minimal role in tolerance (14). Peripheral conversion was also not observed after an acute viral infection and only modestly following immunization (15, 16). Arguably, the published data support the interpretation that chronic Ag exposure creates conditions that favor iTreg cell generation and survival, while during primary responses iTreg cells seem to contribute marginally to Treg cell control. Nevertheless, these studies left unresolved the genetic and functional relationships between iTreg and nTreg cells, as well as the biological relevance of the conversion process itself.

In this study, we used mice that express enhanced GFP (EGFP) under the control of the endogenous Foxp3 promoter with either a functional or a nonfunctional Foxp3 protein (Foxp3EGFP or Foxp3ΔEGFP mice, respectively) to examine in situ conversion and the contribution of iTreg cells to tolerance. As a test of function, we compared the capacity of iTreg and nTreg cells to modify autoimmune inflammation in a lymphopenia-induced model of inflammatory bowel disease. We also compared the gene expression profiles of iTreg and nTreg cells. We found a synergistic role for iTreg cells in the maintenance of dominant immunological tolerance that depended upon Foxp3 to stabilize differentiation induced by T cell activation and TGF-β1.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Foxp3EGFP and Foxp3ΔEGFP mice on the BALB/c background were generated and screened as previously described (16–18). Thy1.1+ Foxp3ΔEGFP newborn mice were rescued by i.p. transfer of 60 × 106 unfractionated Thy1.2+ BALB/c splenocytes to generate naive Thy1.1+CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells with the nonfunctional Foxp3ΔEGFP allele. Rag1−/− mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. The Animal Resource Committees at the Medical College of Wisconsin and at the University of California, Los Angeles, approved all animal experiments, and moribund mice were sacrificed and analyzed per these protocols.

Cell purification and adoptive transfer

Pooled splenocytes and lymph node cells were stained with either anti-CD4-PE or anti-CD4-Pacific Blue and anti-CD45RB-allophycocyanin as appropriate and sorted on the basis of Ab and EGFP fluorescence. All sorting was done on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). The average purity and viability of the sorted CD4+ populations was 98.8 ± 0.2% and 87.6 ± 1.6%, respectively (SEM, n = 23). Colitis was induced in 6-wk-old BALB/c mice by i.p. injection of 4 × 105 CD4+EGFP−CD45RBhigh cells suspended in 1 ml of PBS. Following this injection, mice were weighed twice weekly. In some experiments, when mice had lost 5–7% of their initial body weight, they were treated by i.p. injection of Treg cells purified by cell sorting.

Analytical flow cytometry

Cells were stained as described previously (18) and analyzed using an LSRII (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (Tree Star).

TGF-β1-mediated in vitro conversion

Sorted EGFP− splenocytes from Foxp3EGFP or FoxpΔEGFP mice (1 × 106/ml) were cultured in anti-CD3 mAb (clone 14-2C11 at 2.5 μg/ml)-coated dishes in the presence of soluble anti-CD28 mAb (clone 37.51) at 1 μg/ml with or without TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml; R&D Systems). After 72 h, cells were either analyzed by flow cytometry or resorted based upon EGFP fluorescence.

Suppression assay

BALB/c splenocytes containing 2.5 × 105 responder CD4+ T cells were cultured in 96-well flat-bottom plates in the presence of 1 μg/ml anti-CD3 mAb. The number of responder CD4+ cells was kept constant, while the number of suppressor Treg cells was titrated to achieve the indicated ratios in triplicate wells. Cultures were maintained for 48 h, then pulsed with 0.4 μCi/well [3H]TdR for an additional 18 h, harvested, and counted.

Histology

Complete colons were fixed in formalin, processed, and stained with H&E using a histology core facility. Blinded sections from the entire colon were examined by a pathologist (N.H.S.) and large intestine colitis scores were determined for the following inflammatory changes on a 4-point semiquantitative scale with 0 representing no change (19). The following features were considered: severity, depth and chronic nature of the inflammatory infiltrate, crypt abscess formation, granulomatous inflammation, epithelial cell hyperplasia, mucin depletion, ulceration, and crypt loss.

Statistics

To compare groups with respect to the colitis score, nonparametric methods were used because the data were skewed and ordinal. A Kruskal-Wallis test overall was used with a Mann-Whitney U test for pairwise comparison. Since there were ties, the results were checked for consistency using a Savage test or ordered data or a Cochran-Armitage Savage trend test, whichever was relevant. Lymphocyte numbers and lymphocyte percentages were compared by a two-tailed Student’s t test. To compare percent weight change over time, a random coefficient regression model was used. In the first 10 days, there was little difference between the groups. Analysis was done after day 10. Where the data were nonlinear, a polynomial was fit. The random coefficient model essentially fits each mouse separately and calculates an aggregate weighing with respect to fit of the data to the hypothesized model. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were done using a contrast. No adjustment was made for multiple comparisons. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were compared using the log-rank test.

Gene expression profiling

Purified cells sorted by flow cytometry from 4 to 10 mice were used to generate total RNA, which was amplified and used to create probes for Affymetrix 430 2.0 chips. The subset of probe sets whose expression increased or decreased by 2-fold or more was identified and used for further analysis. The data were normalized using the justRMA algorithm from the Bioconductor group (20). Results represent mean fold change values derived from three to five independent arrays for each cell type and scored p < 0.05 by Student’s unpaired two-tailed t test. Selected targets were verified by flow cytometry. It should be noted that because the gene array probes for Foxp3 lie distal to the poly(A) start site in the Foxp3EGFP allele, a false-negative result is generated for Foxp3 in Foxp3EGFP T cells. The following cell populations were analyzed: freshly isolated and in vitro-activated (anti-CD3 mAb plus IL-2) CD4+EGFP+ (nTreg) cells and CD4+EGFP− (Tconv) cells from Foxp3EGFP mice, iTreg cells from Foxp3EGFP and Foxp3EGFP/+ mice, and ΔiTreg cells from Foxp3ΔEGFP/+ mice. The microarray data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), accession number GSE14415.

Results

In situ-generated iTreg cells in experimental colitis

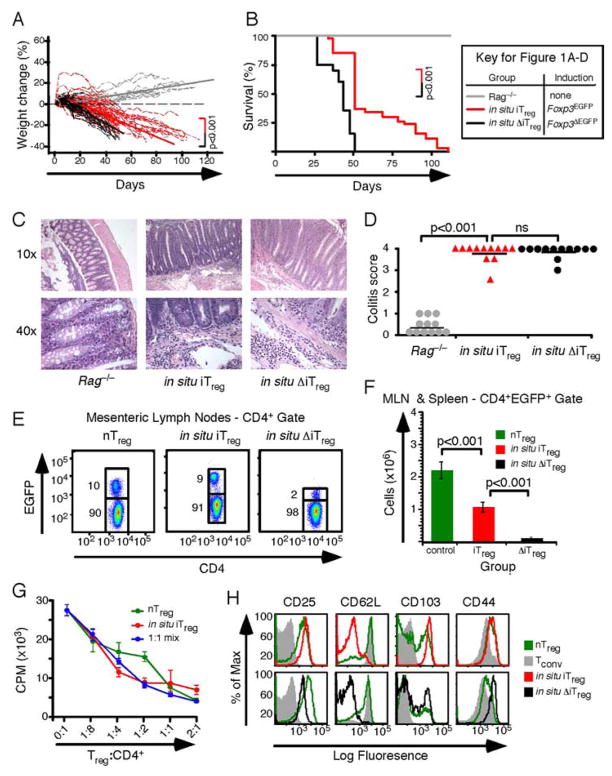

To investigate the relative potency of iTreg cells, the capacity of iTreg cells to suppress autoimmune inflammation was examined in a lymphopenic model of inflammatory bowel disease (21). Colitis was induced in Rag1−/− recipients by the i.p. transfer of 4 × 105 CD4+EGFP− Thy1.2+CD45RBhigh syngeneic Tconv cells isolated by cell sorting from Foxp3EGFP or Foxp3ΔEGFP male mice. In the recipients of naive Tconv cells from Foxp3EGFP mice, diarrhea and weight loss began ~30 days after transfer. Disease progressed until mice became moribund and were sacrificed ~100 days after transfer (Fig. 1, A and B). Colitis was marked by extensive leukocytic infiltration of the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis and serosal layers, absence of mucin-secreting goblet cells, epithelial cell hyperplasia with increased crypt length, epithelial cell ulceration, and crypt abscess formation (Fig. 1C). The mean colitis score from 12 randomly selected moribund mice was 3.8 ± 0.1 (Fig. 1D). Analysis of lymphocytes in the mesenteric lymph nodes 30 days after transfer revealed that 2.4 ± 0.2% of CD4+ Tconv cells had become EGFP+, reflecting the in situ generation of iTreg cells (n = 5; data not shown). This proportion increased to 9 ± 1.3% of CD4+ T cells at the conclusion of the experiment (Fig. 1E). A similar proportion of Treg cells was seen in the mesenteric lymph nodes of normal Foxp3EGFP mice, although the total number of EGFP+ cells was reduced in mice with colitis by ~50% (Fig. 1F). In situ-generated iTreg cells and nTreg cells from healthy mice had similar suppressive function in vitro, as measured by their capacity to reduce Ab-mediated T cell proliferation. A 50:50 mixture of the two cell types did not increase the suppressive effect over that mediated by iTreg cells alone (Fig. 1G). In situ-generated iTreg cells in the mesenteric lymph nodes of mice with colitis could be distinguished from mesenteric lymph node nTreg cells from normal mice on the basis of several cell surface markers including CD25, CD62, and CD103 (Fig. 1H).

FIGURE 1.

Induction of colitis in the absence of functional Foxp3. A, Weight change following the adoptive transfer of 4 × 105 CD4+EGFP−Thy1.2+CD45RBhigh T cells isolated from Foxp3EGFP (dashed red lines; n = 47) and Foxp3ΔEGFP (dashed black lines; n = 20) mice into Rag−/− recipients. Control Rag−/− littermates (gray lines; n = 11) did not receive transferred cells. Color-matched linear regression lines are plotted for each data set. B, Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the mice in A. C, Representative histological sections from the colons of randomly selected mice in A stained with H&E. D, Scatter plot showing the colitis score for each mouse where histology was obtained. E, Representative flow cytometry analysis of the mesenteric lymph nodes from each group (n = 7, 14, and 17, left to right). Numbers denote means for the adjacent gate. F, The total number of Treg cells found in the mesenteric lymph nodes of healthy Foxp3EGFP mice (green) and in mice with colitis with either functional (red) or nonfunctional (black) in situ-derived iTreg cells. G, Representative data from in vitro suppression assays (n = 3) using sorted in situ-derived iTreg cells (red), sorted nTreg cells from healthy mice (green), or a 50:50 mix of each population (blue) to inhibit the anti-TCR-induced proliferation of unfractionated splenocytes. The ratio of Treg cells to CD4+ responder splenocytes is indicated. H, Representative cell surface marker analysis of CD4+EGFP+ mesenteric lymph node Treg cells from E above stained as indicated.

To determine the extent to which in situ-generated iTreg cells might influence disease progression, we induced colitis with 4 × 105 EGFP−Thy1.2+CD45RBhigh syngeneic Tconv cells isolated by cell sorting from Foxp3ΔEGFP mice. For these experiments, Foxp3ΔEGFP mice were rescued at birth with 60 × 106 unfractionated Thy1.1+ splenocytes to allow normal development of the host Thy1.2+CD4+ Tconv cells (our unpublished data). In the absence of a functional Foxp3 locus, weight loss began ~25 days after transfer and was accelerated relative to recipients of CD45RBhigh cells from Foxp3EGFP mice (Fig. 1A, p < 0.001). All mice became moribund and were sacrificed 50 days after initiation of the experiment, demonstrating a significant decrease in survival (Fig. 1B, p < 0.001). Colitis was severe, with a mean colitis score of 3.9 ± 0.1 (Fig. 1, C and D). Flow cytometry revealed a significant decrease in the percent and number of EGFP+ cells (Fig. 1, E and F). In situ-derived ΔiTreg cells generated from Foxp3ΔEGFP Tconv cells had no suppressive function in vitro (data not shown), although their cell surface phenotype was similar to the in situ-derived iTreg cells generated from Foxp3EGFP Tconv cells (Fig. 1H). Thus, Foxp3 is required to sustain iTreg cell numbers and to develop iTreg suppressive function.

Treating established colitis by Treg cell adoptive transfer immunotherapy

In the preceding experiments, the iTreg cells generated in situ from a starting pool of 4 × 105 CD45RBhigh Tconv cells delayed disease progression and prolonged survival, but were not sufficient to prevent severe colitis. Cotransfer of either iTreg or nTreg cells with the CD45RBhigh Tconv cells can prevent disease from developing (22–24). In a setting that must include in situ-generated iTreg cells (Fig. 1), established disease can also be treated by the adoptive transfer of nTreg cells (25). Together, these observations suggest that iTreg cells contribute to tolerance. In the treatment of established disease, it has not been determined whether iTreg and nTreg cells are interchangeable and function in an additive fashion or whether they act synergistically, perhaps by nonredundant mechanisms. To investigate the respective role of iTreg and nTreg cells in therapy, we treated mice at the point where they lost 5–7% of their initial body weight (approximately day 30) with 1 × 106 CD4+Thy1.1+ iTreg cells or 1 × 106 CD4+Thy1.1+ nTreg cells. EGFP+ iTreg cells were generated in vitro by TCR cross-linking in the presence of TGF-β1 and purified by cell sorting. EGFP+ nTreg cells were obtained from the spleens and lymph nodes of Foxp3EGFP mice and also purified by cell sorting. The congenic Thy1.1 marker was used to discriminate between the adoptively transferred Treg cells used to treat the mice and those Thy1.2+ iTreg cells generated in situ during the induction of colitis.

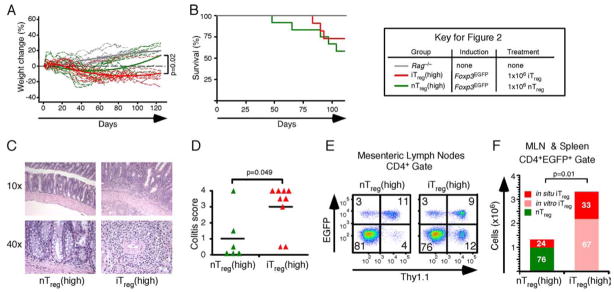

When the number of Treg cells was increased by treating with 1 × 106 CD4+ Thy1.1+ iTreg cells, the mice failed to gain weight but survived to complete the experiment at 125 days (Fig. 2, A and B). Histology showed moderate hypertrophy of the colonic mucosa, distortion of the crypts, and a patchy inflammatory cell infiltrate in the lamina propria (Fig. 2C). Colitis scores averaged 3.0 ± 0.5, consistent with less severe disease than in mice containing only in situ-generated iTreg cells (Figs. 1D and 2D, respectively). In the mesenteric lymph nodes, 9 ± 1.2% of CD4+ T cells were Thy1.1+EGFP+ (in vitro-derived iTreg cells) and 3 ± 0.5% were Thy1.1−EGFP+ (in situ-derived iTreg cells) (Fig. 2E). On average, a total of 3.3 ± 0.7 × 106 Treg cells were recovered from the mesenteric lymph nodes and spleen of treated mice (Fig. 2F).

FIGURE 2.

Treatment of colitis in the presence of in situ-derived iTreg cells. A, Weight change following colitis induced by adoptive transfer of 4 × 105 CD4+EGFP−Thy1.2+CD45RBhigh T cells isolated from Foxp3EGFP mice. After losing 5–7% of their body weight, recipients were treated by i.p. injection of 1 × 106 sorted in vitro-derived Thy1.1+EGFP+ iTreg cells (red; n = 9) or by 1 × 106 sorted Thy1.1+EGFP+ nTreg cells (green; n = 6). Color-matched solid lines represent the polynomial fit based on a random coefficient regression model. B, Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the mice in A. C, Representative histological sections from the colons of the mice in A stained with H&E. D, Scatter plots showing colitis scores for each group. E, Representative flow cytometry analysis of the mesenteric lymph nodes from mice treated with nTreg cells (left panel) or iTreg cells (right panel). Numbers denote mean values for the quadrant. F, Bar graphs depicting the total number of Treg cells found in the mesenteric lymph nodes and spleens of treated mice. The proportion of in situ-derived iTreg cells (red), nTreg cells (green), and in vitro-derived iTreg cells (pink) is indicated.

When mice were treated with 1 × 106 CD4+Thy1.1+ nTreg cells,, they exhibited weight gain consistent with clinical recovery, although survival was not significantly different than in mice treated with iTreg cells (Fig. 2, A and B). Histological examination at 125 days showed nearly normal colons, with an average colitis score of 1.0 ± 0.6 (Fig. 2, C and D). In the mesenteric lymph nodes, 11 ± 1.1% of CD4+ T cells were Thy1.1+EGFP+ (nTreg cells) and 3 ± 0.4% were Thy1.1−EGFP+ (in situ-derived iTreg cells) (Fig. 2E). The total number of Treg cells recovered from the mesenteric lymph nodes was less than half that seen in the iTreg cell-treated mice (1.3 ± 0.3 × 106; Fig. 2F). Thus, despite a >50% reduction in Treg cell numbers, the combination of in situ-derived iTreg cells and nTreg cells suppressed bowel inflammation and restored tolerance, whereas mice with a Treg cell compartment containing only iTreg cells had chronic disease. These data suggested more effective disease suppression when the Treg compartment was comprised of both iTreg and nTreg cells.

Functional synergy between nTreg and iTreg cells

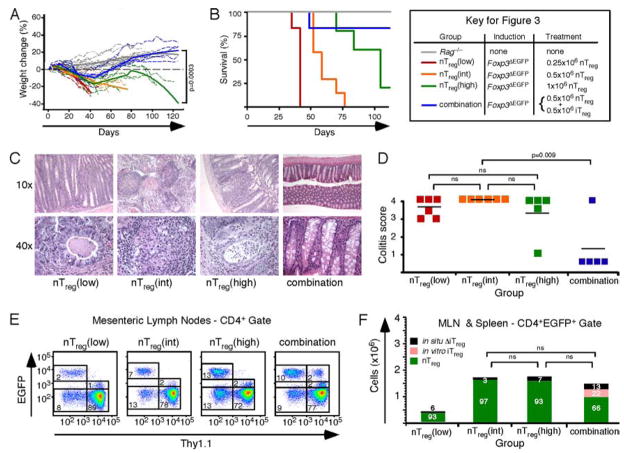

To dissect the individual contributions of iTreg and nTreg cells and to examine the possibility of synergy between the two cell types, we induced colitis by the adoptive transfer of Thy1.1+ CD4+EGFP−CD45RBhigh Tconv cells isolated from Foxp3ΔEGFP mice. In this experiment, functional iTreg cells are not produced in situ (Fig. 1), making it possible to control the Treg cell dose and track each Treg cell population in subsequently treated mice. When the transfer recipients had lost 5–7% of their initial body weight, they were treated with increasing numbers of nTreg cells or with a combination containing iTreg and nTreg cells.

Mice treated with 0.25 × 106 or 0.5 × 106 Thy1.2+ nTreg cells failed to gain weight and had reduced survival (Fig. 3, A and B). Mice treated with 1 × 106 Thy1.2+ nTreg cells initially gained weight for a short period of time, but then progressively lost weight. Only one animal lived to complete the experiment at 125 days. Histological analysis and colitis scores were consistent with severe disease in all groups (Fig. 3, C and D, average colitis score 3.7 ± 0.2). In mesenteric lymph nodes, the percentage of EGFP+ cells within the CD4+ gate increased with the nTreg cell dose, reaching 13 ± 1.7% in mice that received 1 × 106 Thy1.2+ nTreg cells (Fig. 3E). Importantly, 80% of mice that received a total dose of 1 × 106 Treg cells comprised of a 1:1 mix of iTreg and nTreg cells gained weight and recovered completely. They had normal colons by histology (average colitis score, 1.2 ± 0.5). In the mesenteric lymph nodes of these mice, 2 ± 0.1% of the CD4+ T cells were Thy1.1+EGFP+ iTreg cells and 10 ± 0.6% were Thy1.2+EGFP+ nTreg cells (Fig. 3). The mesenteric lymph nodes and spleens of animals that survived for >50 days contained a similar number of Treg cells, suggesting that homeostatic regulation of the Treg cell compartment size is not tightly linked to the developmental origin of the Treg cells (Fig. 3F). Taken together, the data in Figs. 2 and 3 show that the clinical effect of treating with a mixture of both Treg cell types is greater than treating with either iTreg or nTreg cells alone. These data are consistent with the interpretation that iTreg and nTreg cells can act synergistically to establish and maintain tolerance. It seems likely that in situ-derived iTreg cells and nTreg cells also act in concert in a similar fashion.

FIGURE 3.

Treatment of colitis in the absence of in situ-derived iTreg cells. A, Weight change following colitis induced by adoptive transfer of 4 × 105 CD4+EGFP− Thy1.1+CD45RBhigh T cells isolated from Foxp3ΔEGFP mice. After 5–7% weight loss, recipients were treated by i.p. injection of 0.25 × 106 Thy1.2+EGFP+ nTreg cells (red; n = 6), by 0.5 × 106 Thy1.2+EGFP+ nTreg cells (orange; n = 6), by 1 × 106 Thy1.2+EGFP+ nTreg cells (green; n = 5), or by a mixture of 0.5 × 106 Thy1.1+ iTreg and 0.5 × 106 Thy1.2+nTreg cells (blue; n = 5). Color-matched solid lines represent the polynomial fit based on a random coefficient regression model. B, Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the mice in A. C, Representative histological sections from the colons of the mice in A stained with H&E. D, Scatter plots depicting the colitis scores for each group. E, Representative flow cytometry analysis of the mesenteric lymph nodes from mice treated with nTreg cells (left panels) or a mixture of both cell types (right panel). Numbers denote mean values for the quadrant or gate. F, Bar graphs depicting the total number of Treg cells found in the mesenteric lymph nodes and spleens of treated mice. The proportion of nonfunctional in situ-derived ΔiTreg cells (black), nTreg cells (green), and in vitro-derived iTreg cells (pink) is indicated. ns, Not significant).

Gene expression profiles from nTreg and iTreg cells

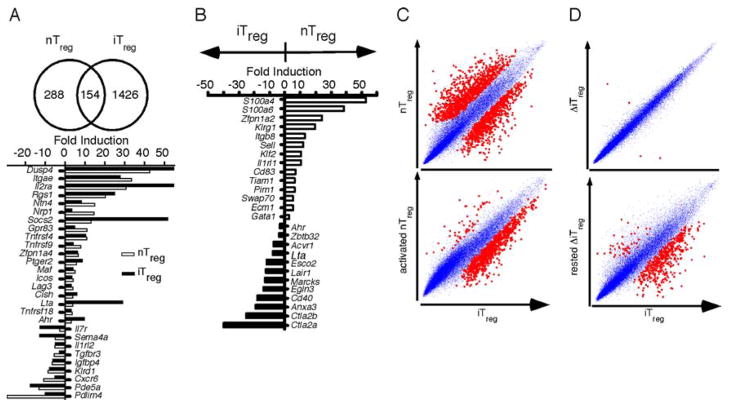

The genetic basis for the synergistic function of iTreg and nTreg cells was investigated by comparing the gene expression profile of in vitro-generated iTreg cells with that of nTreg cells isolated from Foxp3EGFP mice. Results were also compared with other published gene expression profiles of Treg cells and Tconv cells (15, 17, 26, 27). We first identified genes common to nTreg and iTreg cells as compared with Tconv cells. A total of 155 unique genes were found common to both nTreg and iTreg cells, of which 90 were overexpressed and 65 were underexpressed (Fig. 4A and supplemental Table I5). Comparing iTreg and in vitro-activated nTreg cells with activated T cells filtered out the contribution of T cell activation, revealing a smaller subset of common genes that included the prototypical Treg cell genes Socs2, Gpr83, and Nrp1 (neuropilin) (supplemental Table II). Together, these findings confirmed the overlap of the genetic signatures of nTreg and iTreg cells.

FIGURE 4.

Overlap among the gene expression profiles of iTreg cells and nTreg cells. A comparison of the expression profiles of iTreg and nTreg cells with that of Tconv cells identified commonly (A) and selectively (B) expressed genes. All cells were derived from Foxp3EGFP mice. The Venn diagrams illustrate the comparison groups and the number of distinct and shared genes. The bar graphs show a few of the genes that are differentially expressed in iTreg and nTreg cells as mean fold change values derived from three to five independent experiments, each representing mRNA pooled from 4 to 10 mice and scoring p < 0.05 by Student’s unpaired two-tailed t test. C, Scatter plots of mean gene expression values of iTreg cells vs nTreg cells (top panel) or activated nTreg cells (bottom panel). D, Scatter plots of mean gene expression values of iTreg cells vs ΔiTreg cells (top panel) or iTreg cells vs ΔiTreg cells cultured for 7 days in 50 IU/ml IL-2 (bottom panel). Gene comparisons that are found significant in C and D are highlighted in red.

Despite sharing a portion of the Treg genetic signature, nTreg and iTreg cells were genetically distinct, with each subset marked by a large number of differentially expressed genes (Fig. 4, B and C). A subset of canonical Treg transcripts was selectively expressed in freshly isolated nTreg cells but not in iTreg cells, including the Ikaros family member Helios (Zfpn1a2), the calcium-binding protein S100a4 and S100a6, Klrg1, Itgb8, Swap70, Pim1, Ecm1, and Sell. In turn, a large number of transcripts were differentially enriched in iTreg cells, including the serine protease inhibitors Ctla2a and Ctla2b, Tnfrsf5 (CD40), Acvr1 (activin receptor A type I), Lta (lymphotoxin α), Ahr (aryl hydrocarbon receptor), and Zbtb32 (repressor of gata) (supplemental Table III). The aryl hydrocarbon receptor is of particular interest given the recent report that activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor can generate iTreg cells by a TGF-β1-dependent mechanism and that these iTreg cells protect mice from experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (28). Although a subset of the genes selectively enriched in the freshly isolated nTreg cells was down-regulated upon in vitro cell activation, the differential expression of several others, including Zfpn1a2, Sell, and Swap70 was retained (supplemental Table IV). Comparison with in vitro-activated nTreg cells also revealed the iTreg cells to be enriched in components of TGF-β-related pathways, including Acvr1, Tgfbr1, Tgfbr3, Smurf1, Id1, and Id2. Thus, at least some of differences in the gene expression profiles of nTreg and iTreg cells reflected a more fundamental divergence in their genetic programs that could not be attributed to their activation status.

To determine the role of Foxp3 in the induction and maintenance of the iTreg cell genotype, we compared the gene expression profile of successfully derived iTreg cells that expressed high levels of Foxp3 and exhibited potent in vitro suppressive activity with that of CD4+ T cells from the same culture that failed to express Foxp3 (supplemental Table V). We also compared the expression profiles of iTreg cells with ΔiTreg cells derived in vitro from Foxp3ΔEGFP/+ mice (Fig. 4D and supplemental Table VI). Surprisingly, both comparisons revealed that the genetic signatures of the respective populations were virtually identical. However, when sorted ΔiTreg cells were maintained in culture for 7 days in the presence of IL-2, the expression of a number of genes associated with the Treg signature such as Gpr83, Nrp1, and Itgae was down-regulated (Fig. 4D and supplemental Table VII). These findings indicated that, within the set parameters of the analysis, Foxp3 contributed to the subsequent stability but not the initial establishment of the iTreg cell genetic signature, which seems to be primarily shaped by the actions of TGF-β1 and TCR signaling (29).

Discussion

The central finding of this study is that iTreg cells form a subdivision within the peripheral Treg cell pool that can act synergistically with nTreg cells to maintain tolerance. Although Foxp3 is required for iTreg cell function and stability, the genetic signature of iTreg cells only partially overlapped that of nTreg cells, consistent with their different ontogeny and possibly nonredundant functional role. The concordant gene expression profiles seen at early time points in iTreg and ΔiTreg cells indicated that Foxp3 played little role in initiating iTreg conversion. However, similar to nTreg cells, the suppressive function of iTreg cells is absolutely dependent upon Foxp3 (17, 30). The eventual loss of EGFP fluorescence in ΔiTreg cells also indicated that stability of the iTreg phenotype requires continued expression of a functional Foxp3 protein. This would explain previous observations that Tconv cells from Foxp3ΔEGFP mice that were transferred into SCID recipients failed to give rise to iTreg cells in vivo, even while inducing an aggressive colitis (17). A similar role has been suggested for Foxp3 in nTreg cell phenotype stability, supporting the idea that a principle function of Foxp3 is to differentially regulate a subset of genes activated by TCR-, IL-2-, and TGF-β1-mediated signaling and to sustain its own expression (30).

The apparent dual requirement for iTreg and nTreg cells to enforce peripheral tolerance may reflect the distinct ontogeny and Ag specificity of the respective Treg population. Early in life, iTreg cells may be particularly vital due to the delay in nTreg development relative to the production of Tconv cells by the newborn mouse thymus (31). Indeed, early thymectomy removes a large component of the developing nTreg repertoire but leaves intact the capacity of peripheralized Tconv cells to express Foxp3, resulting in a milder disease phenotype than seen in Foxp3 deficiency (32). Other evidence theoretically supports the requirement for iTreg cells. Tconv cells, from which iTreg cells are derived, are by-and-large specific for foreign Ags. Conversely, several studies report that the nTreg cell TCR repertoire may be enriched with self-specific receptors (33, 34), with some overlap with that of Tconv cells (33–36). Our data suggest that when comparing the nTreg and Tconv TCR repertoires, overlap may be largely due to iTreg cells. Expanding clones that produce both Tconv and iTreg cell effectors would be predicted to generate the most frequently shared TCR isolates. Even if the molecular mechanisms for iTreg- and nTreg cell-mediated suppression are functionally equivalent, differences in their TCR repertoires could control the type and extent of Treg cell activation. Additionally, local factors including the type of APC and the availability of cofactors like retinoic acid are likely to influence the size and Ag specificity of the iTreg compartment (37–39). The composition of the antigenic environment may therefore be a primary determinant of the proportional contribution of iTreg and nTreg cells to the maintenance of tolerance.

Differences in the genetic signatures of iTreg and nTreg cells provide clues to their respective attributes. For example, Helios, a member of the Ikaros family of zinc finger transcription factors, was enriched in nTreg relative to iTreg cells. Helios is primarily expressed in T-lineage cells and early multipotential precursors (40, 41). It associates with the nucleosome remodeling deacetylase complex, which has been implicated in the activation of CD4 gene expression in developing thymocytes, suggesting a role for Helios-nucleosome remodeling deacetylase complexes in nTreg development and perhaps phenotype stability (42, 43). In contrast, iTreg cells were enriched in components of TGF-β-related pathways, such as the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, which may promote proliferation in the face of intense TGF-β signaling (44), and lymphotoxin-α, whose role in Treg cell function remains unexplored. Both iTreg and nTreg cells differentially expressed a number of homing receptors such as Sell, suggesting distinct tissue-homing characteristics. These differences may individually or in combination provide differential effector mechanisms, which, together with their distinct TCR repertoires, enable the two populations to synergistically interact to promote in vivo suppression.

Recent reports demonstrate that nTreg cells have epigenetic changes that are consistent with a stable, differentiated cell lineage (45, 46). Unlike nTreg cells, the iTreg cell compartment is not fixed and is maintained in dynamic equilibrium with Tconv cells. For example, in the colitis experiments, functional iTreg cells are clearly generated in situ, while ~60% of the surviving in vitro-derived iTreg cells lost Foxp3 expression. Our experiments are therefore most consistent with a model of Treg cell function that involves a terminally differentiated nTreg cell population augmented by iTreg cells, with the latter entering and leaving the peripheral pool proportional to the needs of the host to control autoinflammatory responses.

Finally, the observation that both iTreg and nTreg cells are necessary to treat active colitis suggests that they may also have non-redundant roles in maintaining tolerance once established. In that regard, nTreg or iTreg depletion experiments in the absence of in situ-generated iTreg cells may help to functionally discriminate between the two cell types. It will also be important to determine whether iTreg cells function at sites other than the mucosal interface, where the microenvironment is conducive to their generation. These investigations will bear on the potential therapeutic use of Treg cells in treating autoimmune diseases and graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation (47). Specifically, the use of iTreg cells derived in vitro from Tconv cells may not prove sufficient to enforce tolerance, particularly in those situations where the indigenous nTreg cells are either depleted or rendered ineffective. Strategies that promote both nTreg and iTreg responses may have a better chance of success.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank James Booth for animal care and Iris Williams-McClain for cell sorting. We also thank James Verbsky, William Grossman, Jack Routes, Jack Gorski, and Bonnie Dittel for helpful discussions and for critical reading of this manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI47154 (to C.B.W.) and AI080002 (to T.A.C.), the D.B. and Marjorie Reinhart, Nickolett, and Montgomery Family Foundations (to C.B.W.), the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin (to C.B.W.), and American Heart Association Grant 0525142Y (to W.L.).

Abbreviations used in this paper: Tconv, conventional T; Treg, regulatory T; iTreg, induced Treg; nTreg, natural Treg; EGFP, enhanced GFP; RORγt, retinoic acid-related orphan receptor γt.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

Disclosures The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, Lei KJ, Li L, Marinos N, McGrady G, Wahl SM. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25− naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-β induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1875–1886. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fantini MC, Becker C, Monteleone G, Pallone F, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Cutting edge: TGF-β induces a regulatory phenotype in CD4+CD25− T cells through Foxp3 induction and down-regulation of Smad7. J Immunol. 2004;172:5149–5153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng SG, Wang J, Wang P, Gray JD, Horwitz DA. IL-2 is essential for TGF-β to convert naive CD4+CD25− cells to CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells and for expansion of these cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:2018–2027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson TS, DiPaolo RJ, Andersson J, Shevach EM. Cutting edge: IL-2 is essential for TGF-β-mediated induction of Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:4022–4026. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulkarni AB, Huh CG, Becker D, Geiser A, Lyght M, Flanders KC, Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Ward JM, Karlsson S. Transforming growth factor β1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:770–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shull MM, Ormsby I, Kier AB, Pawlowski S, Diebold RJ, Yin M, Allen R, Sidman C, Proetzel G, Calvin D, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-β1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992;359:693–699. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li MO, Sanjabi S, Flavell RA. Transforming growth factor-β controls development, homeostasis, and tolerance of T cells by regulatory T cell-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Immunity. 2006;25:455–471. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marie JC, Letterio JJ, Gavin M, Rudensky AY. TGF-β1 maintains suppressor function and Foxp3 expression in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1061–1067. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marie JC, Liggitt D, Rudensky AY. Cellular mechanisms of fatal early-onset autoimmunity in mice with the T cell-specific targeting of transforming growth factor-β receptor. Immunity. 2006;25:441–454. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Apostolou I, von Boehmer H. In vivo instruction of suppressor commitment in naive T cells. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1401–1408. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curotto de Lafaille MA, Lino AC, Kutchukhidze N, Lafaille JJ. CD25− T cells generate CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells by peripheral expansion. J Immunol. 2004;173:7259–7268. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kretschmer K, Apostolou I, Hawiger D, Khazaie K, Nussenzweig MC, von Boehmer H. Inducing and expanding regulatory T cell populations by foreign antigen. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1219–1227. doi: 10.1038/ni1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knoechel B, Lohr J, Kahn E, Bluestone JA, Abbas AK. Sequential development of interleukin 2-dependent effector and regulatory T cells in response to endogenous systemic antigen. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1375–1386. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong J, Mathis D, Benoist C. TCR-based lineage tracing: no evidence for conversion of conventional into regulatory T cells in response to a natural self-antigen in pancreatic islets. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2039–2045. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Williams LM, Dooley JL, Farr AG, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity. 2005;22:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haribhai D, Lin W, Relland LM, Truong N, Williams CB, Chatila TA. Regulatory T cells dynamically control the primary immune response to foreign antigen. J Immunol. 2007;178:2961–2972. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin W, Haribhai D, Relland LM, Truong N, Carlson MR, Williams CB, Chatila TA. Regulatory T cell development in the absence of functional Foxp3. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:359–368. doi: 10.1038/ni1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin W, Truong N, Grossman WJ, Haribhai D, Williams CB, Wang J, Martin MG, Chatila TA. Allergic dysregulation and hyperimmunoglobulinemia E in Foxp3 mutant mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:1106–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leach MW, Bean AG, Mauze S, Coffman RL, Powrie F. Inflammatory bowel disease in C.B-17 scid mice reconstituted with the CD45RBhigh subset of CD4+ T cells. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:1503–1515. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gentleman RC, V, Carey J, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Izcue A, Coombes JL, Powrie F. Regulatory T cells suppress systemic and mucosal immune activation to control intestinal inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:256–271. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powrie F, Leach MW, Mauze S, Caddle LB, Coffman RL. Phenotypically distinct subsets of CD4+ T cells induce or protect from chronic intestinal inflammation in C. B-17 scid mice. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1461–1471. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.11.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Annacker O, Pimenta-Araujo R, Burlen-Defranoux O, Barbosa TC, Cumano A, Bandeira A. CD25+CD4+ T cells regulate the expansion of peripheral CD4 T cells through the production of IL-10. J Immunol. 2001;166:3008–3018. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fantini MC, Becker C, Tubbe I, Nikolaev A, Lehr HA, Galle P, Neurath MF. Transforming growth factor β induced Foxp3+ regulatory T cells suppress Th1 mediated experimental colitis. Gut. 2006;55:671–680. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.072801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mottet C, Uhlig HH, Powrie F. Cutting edge: cure of colitis by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:3939–3943. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.3939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugimoto N, Oida T, Hirota K, Nakamura K, Nomura T, Uchiyama T, Sakaguchi S. Foxp3-dependent and -independent molecules specific for CD25+CD4+ natural regulatory T cells revealed by DNA microarray analysis. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1197–1209. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Z, Herman AE, Matos M, Mathis D, Benoist C. Where CD4+CD25+ Treg cells impinge on autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1387–1397. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quintana FJ, Basso AS, Iglesias AH, Korn T, Farez MF, Bettelli E, Caccamo M, Oukka M, Weiner HL. Control of Treg and TH17 cell differentiation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature. 2008;453:65–71. doi: 10.1038/nature06880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill JA, Feuerer M, Tash K, Haxhinasto S, Perez J, Melamed R, Mathis D, Benoist C. Foxp3 transcription-factor-dependent and -independent regulation of the regulatory T cell transcriptional signature. Immunity. 2007;27:786–800. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gavin MA, Rasmussen JP, Fontenot JD, Vasta V, Manganiello VC, Beavo JA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3-dependent programme of regulatory T-cell differentiation. Nature. 2007;445:771–775. doi: 10.1038/nature05543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fontenot JD, Dooley JL, Farr AG, Rudensky AY. Developmental regulation of Foxp3 expression during ontogeny. J Exp Med. 2005;202:901–906. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory T cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:531–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsieh CS, Liang Y, Tyznik AJ, Self SG, Liggitt D, Rudensky AY. Recognition of the peripheral self by naturally arising CD25+CD4+ T cell receptors. Immunity. 2004;21:267–277. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsieh CS, Zheng Y, Liang Y, Fontenot JD, Rudensky AY. An intersection between the self-reactive regulatory and nonregulatory T cell receptor repertoires. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:401–410. doi: 10.1038/ni1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pacholczyk R, Ignatowicz H, Kraj P, Ignatowicz L. Origin and T cell receptor diversity of Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ T cells. Immunity. 2006;25:249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pacholczyk R, Kern J, Singh N, Iwashima M, Kraj P, Ignatowicz L. Nonself-antigens are the cognate specificities of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2007;27:493–504. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, Hall J, Sun CM, Belkaid Y, Powrie F. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-β and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mucida D, Park Y, Kim G, Turovskaya O, Scott I, Kronenberg M, Cheroutre H. Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science. 2007;317:256–260. doi: 10.1126/science.1145697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun CM, Hall JA, Blank RB, Bouladoux N, Oukka M, Mora JR, Belkaid Y. Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 Treg cells via retinoic acid. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1775–1785. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hahm K, Cobb BS, McCarty AS, Brown KE, Klug CA, Lee R, Akashi K, Weissman IL, Fisher AG, Smale ST. Helios, a T cell-restricted Ikaros family member that quantitatively associates with Ikaros at centromeric heterochromatin. Genes Dev. 1998;12:782–796. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.6.782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelley CM, Ikeda T, Koipally J, Avitahl N, Wu L, Georgopoulos K, Morgan BA. Helios, a novel dimerization partner of Ikaros expressed in the earliest hematopoietic progenitors. Curr Biol. 1998;8:508–515. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sridharan R, Smale ST. Predominant interaction of both Ikaros and Helios with the NuRD complex in immature thymocytes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30227–30238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams CJ, Naito T, Arco PG, Seavitt JR, Cashman SM, De Souza B, Qi X, Keables P, Von Andrian UH, Georgopoulos K. The chromatin remodeler Mi-2β is required for CD4 expression and T cell development. Immunity. 2004;20:719–733. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang X, Fan Y, Karyala S, Schwemberger S, Tomlinson CR, Sartor MA, Puga A. Ligand-independent regulation of transforming growth factor β1 expression and cell cycle progression by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6127–6139. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00323-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baron U, Floess S, Wieczorek G, Baumann K, Grutzkau A, Dong J, Thiel A, Boeld TJ, Hoffmann P, Edinger M, et al. DNA demethylation in the human FOXP3 locus discriminates regulatory T cells from activated FOXP3+ conventional T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2378–2389. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Floess S, Freyer J, Siewert C, Baron U, Olek S, Polansky J, Schlawe K, Chang HD, Bopp T, Schmitt E, et al. Epigenetic control of the foxp3 locus in regulatory T cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roncarolo MG, Battaglia M. Regulatory T-cell immunotherapy for tolerance to self antigens and alloantigens in humans. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:585–598. doi: 10.1038/nri2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.