To the Editor

Although therapeutics for the treatment of pain have developed considerably in the last few years, they still may fail to alleviate pain in cancer patients or become associated with significant undesirable side effects. Pain due to pancreatic cancer may be an example of such an instance. Patients with locally advanced or advanced pancreatic cancer often require increasing doses of opioid pain medications to control their pain. Although effective in pain control, opioids are often associated with adverse side effects: constipation, nausea, confusion and drowsiness. Other treatment options – such as radiation or celiac plexus block – may not provide sustained pain relief.1–4

Recent advances in the techniques of noninvasive brain stimulation may offer alternative therapeutic options for pain control. We recently reported that transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), based on the application to the scalp of a weak direct current to the scalp that flows between two relatively large electrodes – an anode and a cathode5 -- is a an effective method of reducing pain in patients with spinal cord injury and fibromyalgia.6,7 The present case provides proof-of-principle evidence that tDCS can exert clinically meaningful analgesic effects in patients with pain due to pancreatic cancer.

Case

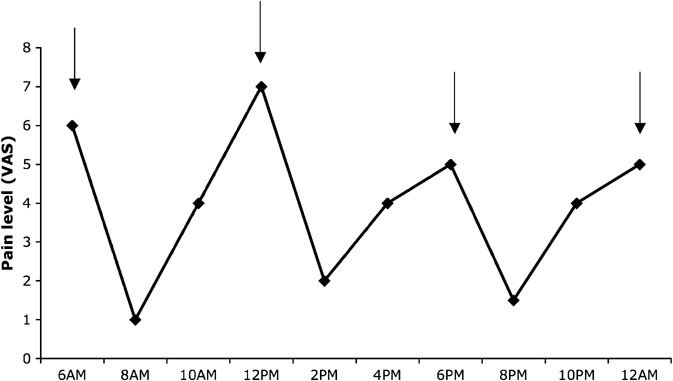

A 65-year-old woman was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer after one year of pain of increasing intensity in the upper abdominal area. The diagnosis of pancreatic cancer was made with a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen, showing an image suggestive of a necrotic mass in the tail of the pancreas. A subsequent biopsy confirmed adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Surgical treatment was not considered due to the local invasion and the presence of metastatic lesions. The patient began chemotherapy with gemcitabine, which resulted in a partial alleviation of her pain. However, after six months, her pain returned and codeine and paracetamol (acetaminophen) were initiated. At the time of the study, she was taking 180mg of codeine per day (four times a day) and up to 2 g of paracetamol. With this treatment regimen, she had pain levels that varied, on average, from 1 to 6 on a numeric scale. She reported that her pain was especially severe when the effects of codeine were wearing off (2–4 hours after the previous dose) (Figure 1 shows her daily variation of pain). In addition, she reported severe constipation with this dosage of codeine.

Figure 1.

Daily variation of pain levels as indexed by visual analogue scale. Arrows indicate the time of medications intake (6AM, 12PM, 6PM and 12AM). The patient was taking codeine 45 mg of codeine and 500 mg of paracetamol.

After giving written informed consent, the patient participated in a research protocol investigating the effects of noninvasive brain stimulation in patients with chronic pain. The protocol was approved by the local research ethics committee. While blinded to the treatment condition, she received sham and active tDCS in a randomized order. We measured pain, cognitive effects, and side effects using the following instruments: numeric scales for pain, mood and anxiety; Mini-Mental State examination (MMSE); Stroop test; Forward and Backward Digit Span; and a questionnaire for adverse effects. During the day of stimulation, medication was withheld in order to evaluate her response without the effects of analgesics. We also asked her immediately after each tDCS session to guess which type of stimulation she received. She responded that she believed she received active stimulation in both situations (could not differentiate). Importantly, the rater was also blinded to the treatment received by the patient.

Direct current was transferred by using a saline-soaked pair of surface sponge electrodes and delivered by a custom developed, battery-driven, constant current stimulator with a maximum output of 10 mA and electrode size of 35 cm2. The anode electrode was placed over C3 (using EEG 10/20 system – corresponding to the primary motor cortex6 and the cathode electrode was placed over the contralateral supraorbital area.

During sham stimulation, the patient had no change in pain levels and pain worsened two hours after the tDCS (increase of 2 points). However, after active stimulation, she reported that she was pain free (her pain decreased from 4 to zero) and the benefit lasted for several hours. The effect was particularly remarkable as she reported that she usually could not tolerate skipping one dose of her medication for more than four hours (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pain levels during treatment with sham and active tDCS. During treatment with tDCS, medications were withheld.

There were no adverse effects. After sham stimulation, her MMSE did not change, digit span forward did not change, digit span backward increased one sequence (2 to 3), and Stroop colors performance execution time decreased from 25.63 to 22.89 seconds. After active stimulation, MMSE, digit span forward and backward did not change, and Stroop colors execution time also decreased from 23.06 to 20.56. There were no changes in mood and anxiety after either sham or active stimulation.

Comment

This case report shows that active, but not sham, tDCS can acutely alleviate pain due to advanced pancreatic cancer. In addition, we also showed that, in this patient, this treatment was not associated with adverse events, cognitive changes, or mood changes. We previously showed that using another technique of noninvasive brain stimulation (repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation) also can significantly suppress chronic visceral pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis.8

Prior work done in patients with chronic pancreatic inflammation suggests that sustained chronic visceral pain from pancreatic disease affects: 1) the interaction and modification of various somatic sensory modalities between the ascending pathways;9,10 2) the activation of spinal gating mechanisms through the dorsal column neural synapses;11 and 3) reorganization in the cortical representation of visceral sensation, including a suppression of local GABAergic and a potentiation of glutamatergic activity. In fact, chronic pancreatitis patients report a decrease in pain when given ketamine, a non-competitive antagonist of glutamatergic NMDA receptors.12 NMDA receptors enhance brain excitability, can control synapse maturation, and modulate other receptors, such as the GABA-A receptors.13

The rationale of using the primary motor cortex as the target comes from studies using epidural motor cortex stimulation,14, 15 suggesting the potential therapeutic utility of motor cortex stimulation. Up-regulation of motor cortex excitability might modulate pain perception through indirect effects via neural networks on pain-modulating areas, such as thalamic nuclei, as suggested by neuroimaging.14

Several limitations should be discussed. First, this is a report of one case only. However, we believe this is important to report in order to encourage future research in this area. Second, we did not measure the long-term effects of this therapy. Therefore, it is unclear whether the effects would be long-lasting if several sessions of tDCS are applied; this should be further explored. We previously showed that five consecutive sessions of tDCS in chronic pain due to spinal cord injury results in pain alleviation that lasts five days;6 however, mechanisms of pain in pancreatic cancer are certainly different.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Pancreas Foundation and the Harvard-Thorndike General Clinical Research Center at BIDMC (NCRR MO1 RR01032 -CREFF/BIDMC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Gisele Silva, Department of Neurology, Federal University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

Rebecca Miksad, Department of Oncology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Steven D. Freedman, Pancreas Center, Department of Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Alvaro Pascual-Leone, Berenson-Allen Center for Noninvasive Brain Stimulation, Department of Neurology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Sanjay Jain, Department of Oncology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Daniela L. Gomes, Department of Neurology, Federal University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

Edson J. Amancio, Centro de Neurocirugia Funcional e Dor, Hospital 9 de Julho, São Paulo, Brazil.

Paulo S. Boggio, Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie, São Paulo, Brazil.

Claudio F. Correa, Centro de Neurocirugia Funcional e Dor, Hospital 9 de Julho, São Paulo, Brazil.

Felipe Fregni, Berenson-Allen Center for Noninvasive Brain Stimulation, Department of Neurology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA.

References

- 1.Dobelbower RR, Jr, Borgelt BB, Strubler KA, Kutcher GJ, Suntharalingam N. Precision radiotherapy for cancer of the pancreas: technique and results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1980;6(9):1127–1133. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(80)90164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haslam JB, Cavanaugh PJ, Stroup SL. Radiation therapy in the treatment of irresectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Cancer. 1973;32(6):1341–1345. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197312)32:6<1341::aid-cncr2820320609>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong GY, Schroeder DR, Carns PE, et al. Effect of neurolytic celiac plexus block on pain relief, quality of life, and survival in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(9):1092–1099. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young RF, Brechner T. Electrical stimulation of the brain for relief of intractable pain due to cancer. Cancer. 1986;57(6):1266–1272. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860315)57:6<1266::aid-cncr2820570634>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nitsche MA, Liebetanz D, Antal A, et al. Modulation of cortical excitability by weak direct current stimulation--technical, safety and functional aspects. Suppl Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;56:255–276. doi: 10.1016/s1567-424x(09)70230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fregni F, Boggio PS, Lima MC, et al. A sham-controlled, phase II trial of transcranial direct current stimulation for the treatment of central pain in traumatic spinal cord injury. Pain. 2006;122(1–2):197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fregni F, Gimenes R, Valle AC, et al. A randomized, sham-controlled, proof of principle study of transcranial direct current stimulation for the treatment of pain in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(12):3988–3998. doi: 10.1002/art.22195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fregni F, DaSilva D, Potvin K, et al. Treatment of chronic visceral pain with brain stimulation. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(6):971–972. doi: 10.1002/ana.20651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sung B, Lim G, Mao J. Altered expression and uptake activity of spinal glutamate transporters after nerve injury contribute to the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain in rats. J Neurosci. 2003;23(7):2899–2910. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02899.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sung YJ, Walters ET, Ambron RT. A neuronal isoform of protein kinase G couples mitogen-activated protein kinase nuclear import to axotomy-induced long-term hyperexcitability in Aplysia sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24(34):7583–7595. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1445-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishikawa K, Tanaka M, Black JA, Waxman SG. Changes in expression of voltage-gated potassium channels in dorsal root ganglion neurons following axotomy. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22(4):502–507. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199904)22:4<502::aid-mus12>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mannion S, O’Brien T. Ketamine in the management of chronic pancreatic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26(6):1071–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aamodt SM, Constantine-Paton M. The role of neural activity in synaptic development and its implications for adult brain function. Adv Neurol. 1999;79:133–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-Larrea L, Peyron R, Mertens P, et al. Electrical stimulation of motor cortex for pain control: a combined PET-scan and electrophysiological study. Pain. 1999;83(2):259–273. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsubokawa T, Katayama Y, Yamamoto T, Hirayama T, Koyama S. Chronic motor cortex stimulation in patients with thalamic pain. J Neurosurg. 1993;78(3):393–401. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.3.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]