Abstract

Correlations between adolescents' own antisocial behavior and adolescents' perceptions of the antisocial behavior of their best friends and friendship groups were examined in this study. The strength of those correlations was expected to vary as a function of the qualities of the dyadic friendships and group relationships. Perceptions of peers' antisocial behavior and dyadic friendship and group relationship qualities were collected through interviews with 431, 12- through 13-year-old adolescents. Measures of adolescents' concurrent and subsequent antisocial behaviors were obtained from the adolescents and their teachers. Adolescents who perceived their friends and groups as participating in antisocial behavior had higher self-reported and teacher-reported antisocial behavior ratings. Perceptions of best friend antisocial behavior were correlated more strongly with adolescents' own concurrent, but not subsequent, antisocial behavior when high levels of help, companionship, and security characterized dyadic friendships. The results are discussed in terms of peer influence and friendship selection processes.

Peer relationships in childhood and adolescence are believed to play an important role in desirable and undesirable developmental outcomes. Information on whether a child has friends, the quality of the child's peer relationships, and the identity of the peers all contribute to understanding the developmental implications of peer relationship experiences (Hartup, 1996). However, researchers who have examined the link between peer relationships and adjustment typically have focused on either the qualities of peer relationships (such as feelings of connectedness to a specific friend or time spent “hanging out” with a specific group of friends) or the general behavioral characteristics of individuals (such as overall levels of antisocial behavior, whether inside or outside of peer relationships). Researchers, further, have limited their inquiry to either the impact of close friends (Savin-Williams & Berndt, 1990) or the impact of the broader peer group (i.e., cliques, crowds, and friendship groups; see Brown, 1990). The purpose for the current study was to examine the relationships between the antisocial behavior of adolescents' peers and adolescents' own antisocial behavior (e.g., fighting, lying, stealing) as a function of the qualities of the specific peer relationships. Those relationships were examined in dyadic friendship and friendship group contexts.

A commonly reported finding is that adolescents' behavior tends to mirror the behavior of their friends and peer groups. For example, adolescents' delinquent behavior is predicted strongly by the extent to which adolescents' peers are involved in delinquent activity (e.g., Simons, Wu, Conger, & Lorenz, 1994; Warr & Stafford, 1991). Links also have been reported between adolescents' and peers' smoking, drinking, and drug use, with adolescents' involvement in such behaviors showing a positive relationship to their friends' involvement in the same behaviors (e.g., Ennett & Bauman, 1994; Tolson & Urberg, 1993). Those associations appear to hold for dyadic friendships and groups. A goal in the current study was to contextualize the findings of earlier research by determining whether the association between adolescents' antisocial behavior and the adolescents' perceptions of peer antisocial behavior varied as a function of the qualities of the adolescents' peer relationships. It was hypothesized that the magnitude of the impact of peers' antisocial behavior on an adolescent's own behavior would depend on the closeness and strength of the relationships between the adolescent and his or her peers. The moderation hypothesis was tested in the dyadic friendship and friendship group contexts to determine whether high quality peer relationships appear to promote or result from behavioral concordance in both peer contexts or if the pattern is limited to dyadic friendship or friendship group relationships.

Several qualities of dyadic friendships have been identified as particularly important for adolescents' social adjustment (see Furman, 1996). Those qualities include companionship (e.g., spending time together), lack of conflict (e.g., the ability to solve disagreements), support (e.g., providing instrumental assistance), security (e.g., faithfulness), and closeness (e.g., feelings of connectedness; see Bukowski, Hoza, & Boivin, 1994; Furman & Buhrmester, 1985; Parker & Asher, 1993). Dyadic friendships characterized by high levels of companionship, support, security, and closeness and low levels of conflict are expected to provide adolescents with the social support and intimacy needed in times of crisis as well as with opportunities for spending time with peers and learning to solve peer relationship problems constructively. Friendships with those qualities have been found to be related positively to self-esteem and related negatively to delinquency, hostility, school problems, and psychiatric symptomatology (Buhrmester, 1990; Hirsch & DuBois, 1992). Moreover, the friendships among more antisocial early adolescents have been found to be of lower quality than are friendships among less antisocial early adolescents (Dishion, Andrews, & Crosby, 1995).

To a lesser extent, researchers also have worked to identify qualities of adolescent group relationships. Group relationship qualities are similar to dyadic friendship qualities in that they focus on the attachment to, and potential support received from, the group. However, conclusions drawn regarding associations between group relationship qualities and adjustment are more tentative, because fewer empirical studies have explored those relationships. Adolescent adjustment has been hypothesized to be associated with (a) whether adolescents believe themselves to be members of a group, (b) how involved and attached the adolescents feel to a particular group, and (c) how important the group is to the adolescents (Brown, 1990; Gavin & Furman, 1989; Newman & Newman, 1976). Ethnographic studies have indicated that adolescents who belong to a group and who feel valued by the group are likely to have a more positive self-image, greater self-confidence, and well-developed interpersonal skills in comparison to adolescents who do not belong to a group or who feel that they are not valued by fellow group members (Hallinan, 1980).

Three studies that have related adolescents' behavior to the behavior of their peers have examined those relationships vis-à-vis the qualities of the peer relationships. Results reported by Agnew (1991) and Wills and Vaughan (1989) have indicated that peer delinquent behavior, smoking, and drinking are related more strongly to adolescents' own delinquent behavior, smoking, and drinking when the adolescents feel more attached to, and spend more time with, their peers. In the only study to test the moderation hypothesis in dyadic friendship and friendship group contexts, Aloise-Young, Graham, and Hansen (1994) found that the similarity between adolescents' own smoking behavior and the smoking behavior of acquaintances and group members predicted the formation, but not the breakdown, of dyadic friendships and friendship groups. Aloise-Young and colleagues interpreted those results as evidence that adolescents might modify their behavior to become friends with a peer or to gain entrance to a friendship group. Alternatively, those results might indicate that behavioral similarity provides the basis for forming close friendships and that without a minimal degree of behavioral concordance, acquaintances are unlikely to become close friends. On the basis of the findings from those three studies, it was expected that adolescents' own antisocial behavior would be related more strongly to perceptions of best friend and group antisocial behavior in the context of close, intimate, and satisfying peer relationships. Such a pattern of moderation is consistent with peer influence and friendship selection interpretations.

It was also of interest to determine whether relationship qualities would moderate the effect of peer antisocial behavior for boys and for girls. Research on peer relationship qualities consistently has identified a pattern of gender differences whereby girls report more intimacy and closeness in their peer relationships than do boys (e.g., Bukowski et al. 1994; Parker & Asher, 1993). Because girls appear to value close relationships more than do boys (Hartup, 1993), it might be that relationship qualities are stronger moderators of the impact of peer antisocial behavior for girls than for boys. Evidence that relationship qualities are stronger moderators for girls than for boys would be provided by a significant three-way interaction involving relationship qualities, peer antisocial behavior, and gender when predicting adolescent antisocial behavior.

Because the associations between adolescent behavior and peer behavior have been shown to result from friendship selection and peer influence processes (see Dishion, Patterson, & Griesler, 1994; Fisher & Bauman, 1988; Tremblay, Masse, Vitaro, & Dobkin, 1995) and because there is considerable interest in attempting to differentiate those two processes empirically (see Ennett & Bauman, 1994; Urberg, Değirmencioğlu, & Pilgrim, 1997), analyses were conducted with concurrent and subsequent adolescent antisocial behavior both serving as dependent variables. When evaluating the prediction of later antisocial behavior, concurrent antisocial behavior was included as a covariate. Controlling for concurrent antisocial behavior is an attempt to show that continuity in antisocial behavior is not responsible for any longitudinal associations between peer antisocial behavior and adolescents' own antisocial behavior. That procedure has been used by other researchers when attempting to differentiate between selection and influence processes (e.g., Berndt & Keefe, 1995).

The primary hypothesis tested in the current study was that adolescents' perceptions of best friend and friendship group antisocial behavior would be associated with adolescents' own concurrent and subsequent antisocial behavior. Two corollary hypotheses also were tested: First, perceptions of best friend and group antisocial behavior were hypothesized to be stronger predictors of adolescents' own antisocial behavior in the context of close, supportive dyadic friendship and friendship group relationships. Second, relationship qualities were hypothesized to moderate the associations between perceptions of best friend and group antisocial behavior and adolescents' own antisocial behavior more strongly for girls than for boys.

Method

Participants

The current assessment of adolescent peer relationships was based on interviews with 431 early adolescents (12 through 13 years of age) conducted in the adolescents' homes or schools. The peer influence and selection processes examined in this study have been shown in other studies to be particularly strong for this age group (Berndt, 1979; Brown, Clasen, & Eicher, 1986). The adolescents and their families were in the eighth year of participation in the ongoing Child Development Project (CDP; see Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1990; Pettit, Bates, & Dodge, 1997), a multisite longitudinal study of socialization factors in children's and adolescents' adjustment. A total of 585 children and their families have participated in the CDP since being recruited from three geographical areas (Nashville and Knoxville, Tennessee and Bloomington, Indiana) during kindergarten preregistration in the summers of 1987 and 1988. The Hollingshead (1975) four-factor index of social status was computed from demographic information provided by the parents at the time of recruitment. CDP adolescents who participated in the seventh-grade interviews (74% of the full sample) were from slightly higher socioeconomic status families than were CDP adolescents who chose not to participate (X̄s = 40.7 and 36.2, SDs = 14.1 and 13.2, for participants and nonparticipants, respectively, t(568) = 3.45, p < .001), participants were more likely to be of European American descent than were nonparticipants (84.4% and 73.4%, χ2(1) = 8.94, p < .01), and participants were more likely to be girls than were nonparticipants (51.5% and 42.3%, χ2(1) = 3.84, p = .05). Participants did not differ from nonparticipants in single-parent status (24.2% and 30.3% for participants and nonparticipants, respectively, χ2(1) = 2.11, n.s.) or mother-reported internalizing (X̄s = 6.69 and 6.03, SDs = 4.9 and 5.0, t(565) = 1.42, n.s.) or externalizing behavior problems in kindergarten (X̄s = 11.55 and 11.38, SDs = 6.9 and 7.5, t(565) = .26, n.s.).

Procedure

On a yearly basis, parents were contacted and asked to provide informed consent to obtain information from the adolescents' teachers and schools. Adolescent participants were contacted via telephone during the winter of their seventh-grade school year and asked to participate in a structured, face-to-face interview. The adolescents were given the choice of being interviewed in their schools or homes by trained graduate student interviewers and were told that they had the option to stop the interview at any time. A subset of respondents (about 15%) had moved out of state since the study began; those adolescents were interviewed over the telephone, and the questionnaires were mailed to them. Adolescents were compensated $15 for participating in the interview session.

The assessment was composed of several different sections that focused on after-school care, parenting, peer relationships, and behavior problems. Only the sections of the assessment that focused on peer relationships and behavior problems are relevant to the current article. The peer relationship portion of the assessment was divided into several parts. First, all of the adolescents were asked to name their best friend and to orally complete the Friendship Qualities Scale and describe the antisocial behavior of their best friends. Generally, other CDP participants were not named as best friends. Next, adolescents were questioned to determine whether they believed they were members of a friendship group. The adolescents were asked which of three statements best described how they spend most of their free time at school. The three statements were, “I spend most of my free time at school (a) alone, (b) hanging out with a group of friends, and (c) alone with my best friend.” Most (78%) adolescents reported spending their free time with a group of friends and thus were asked a set of questions to assess group qualities and behavior. The friendship group section of the interview was skipped for adolescents who reported that they spent most of their free time at school alone or with a best friend, although those adolescents might have spent some portion of their free time in a group context. At the conclusion of the interview, the adolescents were asked to complete a standard behavior problem questionnaire. Adolescents were asked to complete the same behavior problem questionnaire approximately 16 months later during an interview session in the summer following eighth grade. Three hundred seventy adolescents participated in the Grade 7 interview and completed the behavior problem questionnaire in Grade 7 and Grade 8.

Near the end of the seventh-grade school year (approximately 2 to 3 months after the peer relationship interview), school personnel (typically the principal or school secretary) were asked to identify the one teacher who best knew each adolescent. That teacher then was asked to complete a set of questionnaires to assess the adolescents' behavioral adjustment in seventh grade. The same procedure was used to identify teachers who best knew each adolescent at eighth grade. That teacher was asked to complete a set of questionnaires to assess the adolescents' behavior in eighth grade. Grade 7 and Grade 8 teacher data were available for 361 of the adolescents.

Adolescent self-reports served as the primary index of antisocial behavior whereas teacher reports of antisocial behavior were included to test the generalizability of results across different informants. Teachers might have considerable difficulty accurately reporting antisocial behavior among early adolescents because of the covert nature of many forms of antisocial behavior (e.g., lying, vandalism) and, as a result, teachers might rely heavily on the adolescents' reputations and limited classroom-based interactions. Nonetheless, if results replicate across adolescent reports and teacher reports, that might provide evidence that significant results are not due entirely to shared method variance.

Measures

Dyadic friendship relationship qualities

A modified version of the Friendship Qualities Scale (Bukowski et al., 1994) was used to assess friendship qualities in the current study. The original version had 23 items rated on a 5-point scale. The items represented five subscales (companionship, conflict, help, security, closeness). Each item in the modified version was rated on a 3-point scale (0 = Not true, 1 = Somewhat/sometimes true, 2 = Very/often true). The response scale was changed to make the options more consistent with other scales used throughout the interview. In addition, three of the original items were dropped when pilot testing revealed that those items were unclear or inappropriate for some of the study participants (i.e., “If I forgot my lunch or needed a little money, my friend would loan it to me”; “I think about my friend even when my friend is not around”; “If my friend and I have a fight or argument, we can say ‘I'm sorry’ and everything will be alright”). In an attempt to capture more fully the dyadic qualities of friendships, seven supplementary items were written by rephrasing the original items to emphasize the help and security provided to the friend by the adolescent, as distinguished from the help and security provided by the friend to the adolescent. Those seven new items were expected to form two additional subscales: one 4-item subscale to index the help provided to the friend by the adolescent (α = .79; e.g., “I help my friend if she is having trouble with something”) and one 3-item subscale to index the security provided by the adolescent to the friend (α = .53; e.g., “If my friend has something bothering him he can tell me about it even if it is something he cannot tell to other people”). The internal consistency of the original five scales was modest and ranged from .58 for the companionship scale through .73 for the closeness scale (help scale α = .72, conflict scale α = .67, and security scale α = .60). After reverse scoring the conflict items, a composite dyadic friendship qualities score was computed as the sum of the 27 items (α = .88, range = 0 through 54).

Best friend antisocial behavior

To assess perceptions of the mildly antisocial behavior of best friends, five items taken from Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller, and Skinner (1991) were embedded into the friendship qualities portion of the interview. Those five items (i.e., “My friend (a) gets into trouble at school, (b) gets into fights with other kids, (c) uses bad language, (d) lies to his or her parents and teachers, and (e) likes to do things that make me scared or uncomfortable”) were rated on the same 3-point scale as the friendship qualities items. A best friend antisocial behavior score was created by taking the mean rating for the five best-friend behavior items (α = .69, range = 0 through 2).

Friendship group relationship qualities

Friendship group relationship qualities were operationalized as group affiliation or involvement and enjoyment. Four items were written to reflect the affiliation or involvement aspect of group quality (i.e., “I feel happiest when I am with members of my group”; “It is important to me to be a member of my group”; “I spend as much time as I can with my group”; and “When my group does something together, others are sure to let me know”) and were rated on a 3-point scale (0 = Not true, 1 = Somewhat/sometimes true, 2 = Very/often true). Those items were based on items described by Brown and Lohr (1987) and Gavin and Furman (1989). Three additional items were written to index the extent to which the adolescents found membership in the friendship group to be enjoyable (i.e., “The kids in my group, (a) have good ideas about fun things to do, (b) have a lot of fun, and (c) have lots of friends at school”) and each item was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = Never, 2 = Once in a while, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Fairly often, 5 = Very often). After rescaling to a common metric, a friendship group qualities score (α = .66, range = 1 through 5) was computed by taking the mean of the seven items.

Friendship group antisocial behavior

Adolescents also rated how often the members of their friendship groups engaged in each of five mildly antisocial behaviors on a 5-point scale (1 =Never, 2 = Once in a while, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Fairly often, 5 = Very often). The behaviors were the same behaviors used to index friend antisocial behavior, but the group items appeared in a slightly different format (i.e., the phrase “the members of my group” replaced the best friend's name) and in a different section of the interview. A group antisocial behavior score was created by taking the mean rating for the five friendship group behavior items (α = .74, range = 1 through 5).

Adolescents' own antisocial behavior

Adolescent-reported antisocial behavior scores were computed from the Youth Self Report (YSR, Achenbach, 1991b). Of particular interest were antisocial behaviors that are likely to be influenced by peer relationship processes (in contrast to aggression that has been shown to be very stable over time, see Huesmann & Moise, 1998). The YSR “delinquency scale” scores were used to index adolescent-reported antisocial behavior. The “delinquency scale” score is the sum of 11 items (e.g., steals, uses alcohol or drugs, lying or cheating; αs = .69 and .73 for Grade 7 and Grade 8, respectively). Each item is scored on a 3-point scale (0 = Not true, 1 = Somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = Very often or often true). Four hundred seven adolescents completed the YSR during the interview session in Grade 7 and 370 adolescents completed the YSR in Grade 8. Adolescents with complete YSR data did not differ significantly from adolescents for whom YSR data were available in Grade 7 only in any of the peer relationship variables.

Teacher-reported antisocial behavior scores were computed from the Teachers' Report Form (TRF, Achenbach, 1991a). The TRF “delinquency scale” scores were used to index teacher-reported antisocial behavior. The “delinquency scale” score is the sum of nine items (e.g., steals, uses alcohol or drugs, lying or cheating; αs = .75 and .78, for seventh and eighth grades, respectively). Each item is scored on a 3-point scale (0 = Not true, 1 = Somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = Very often or often true). Teachers provided TRF data for 391 adolescents in Grade 7 and 361 adolescents in Grade 8. No significant differences in the peer relationship variables were found between adolescents with complete TRF data and adolescents for whom TRF data were available only in Grade 7.

Results

Analyses were done in three steps. First, features of the adolescent peer relationship descriptions were examined to determine if the descriptions were comparable to the friendships and group relationships described in past studies. That examination included analyses testing for gender differences in mean scores on each of the peer relationship variables. Next, relations among the peer relationship measures were examined to consider the association between relationship qualities and peer antisocial behavior and to identify which peer relationship variables showed significant bivariate relations with adolescents' own antisocial behavior. Finally, a series of analyses were conducted to test the hypotheses that relationship qualities would moderate the relations between peer antisocial behavior and adolescents' own antisocial behavior and that the moderation would differ for girls and for boys. Concurrent and longitudinal predictions were evaluated in those analyses.

Construct Measurement

Descriptive features of friendship groups and best friendships

Almost 78% of the adolescents reported that they were members of a friendship group. Adolescent friendship groups ranged in size from 3 through 10, with 50% of the groups composed of seven or fewer members. Most of the group members (66.8%) reported that all of the members of their groups were the same gender and 64% of the group members reported that there were none in their groups who were more than 1 year older than the respondents. Group size was correlated modestly with group qualities (r = .14, p < .05) and group antisocial behavior (r = .15, p < .01), indicating that members of larger groups reported more enjoyment and involvement with their group and perceived more frequent antisocial behavior among group members. Furthermore, t-tests revealed that group members did not differ significantly from non-members in the quality of their best friendships, in perceptions of best friend antisocial behavior, or in adolescent-reported or teacher-reported antisocial behavior in Grade 7 or Grade 8 (all ts < 1.4, ps > .15).

All of the adolescents interviewed were able to name a best friend. Nearly 75% of the group members named a member of their friendship group as their best friend. The mean length of the best friendship was 42.7 months, but the large standard deviation (SD = 35.7) indicated a variety of friendship experiences. One-fourth of the adolescents reported having formed their best friendship in the past year (i.e., less than 12 months in length), and 22% reported friendships lasting longer than 5 years (i.e., more than 60 months in length). Length of friendship was not associated with friendship qualities or perceptions of best friend antisocial behavior (rs = .02 and −.04, respectively, both ps > .40).

Gender differences

A set of analyses was conducted to explore possible gender differences in peer relationship experiences. Two MANOVAs were conducted to test for mean level gender differences in the peer relations and adjustment variables. The best friendship and antisocial behavior variables were dependent variables in the first MANOVA. There was a significant overall gender difference, F(6, 287) = 6.30, p < .001. Friendship-group relationship qualities and group antisocial behavior were dependent variables in the second MANOVA. Again, there was a significant overall gender difference, F(2, 331) = 5.08, p < .01. Several t-tests were conducted as a follow-up to identify gender differences on specific peer relationship variables. Those results are summarized in Table 1. Girls had higher scores for dyadic friendship and group relationship qualities, whereas boys perceived more antisocial behavior among their best friends and groups than did girls. Moreover, three of the four reported antisocial behavior scores were higher for boys than for girls. Gender differences in the relationships among the variables were tested through interaction effects, as will be described.

Table 1. Peer Relationship and Antisocial Behavior Means by Adolescent Gender.

| Girls | Boys | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | X̄ (SD) | X̄ (SD) | df | t |

| Dyadic friendship qualities total score | 39.98 (4.5) | 36.49 (6.6) | 428 | −6.45*** |

| Companionship | 1.58 (.35) | 1.52 (.35) | 428 | −1.98* |

| Conflict | .63 (.47) | .57 (.45) | 428 | −1.34 |

| Help | 1.87 (.25) | 1.74 (.35) | 428 | −4.30*** |

| Security | 1.84 (.26) | 1.68 (.36) | 428 | −5.29*** |

| Closeness | 1.91 (.21) | 1.72 (.34) | 428 | −6.56*** |

| Help provided | 1.94 (.18) | 1.84 (.30) | 428 | −4.45*** |

| Security provided | 1.88 (.25) | 1.65 (.39) | 428 | −7.24*** |

| Best friend antisocial behavior | .25 (.31) | .35 (.35) | 428 | 3.26*** |

| Group relationship qualities | 3.88 (.40) | 3.75 (.40) | 331 | −2.96** |

| Group antisocial behavior | 1.81 (.74) | 1.94 (.61) | 331 | 1.74* |

| Adolescent antisocial behavior | ||||

| Grade 7 YSR (adolescent report) | 2.14 (2.1) | 2.69 (2.5) | 405 | 2.42* |

| Grade 7 TRF (teacher report) | .97 (1.8) | 1.44 (2.2) | 406 | 2.09* |

| Grade 8 YSR | 2.99 (2.9) | 3.15 (2.5) | 368 | .58 |

| Grade 8 TRF | 1.26 (2.1) | 1.79 (2.4) | 359 | 2.24 |

Note: n = 170 through 213 for girls and 165 through 218 for boys.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Relationships among peer relationship constructs

Correlations between the scores that indexed each of the peer relationship domains are shown in Table 2. Adolescents who reported higher quality friendships and group relationships also perceived less frequent antisocial peer behavior among their best friends and the members of their friendship groups. Adolescents who reported high quality friendships also reported high quality group relationships. Likewise, adolescents who reported frequent antisocial behavior among their best friends also reported frequent antisocial behavior among their groups. That is not surprising, because in many cases the best friend was also a member of the friendship group. Higher levels of adolescent-reported and teacher-reported antisocial behavior were associated with perceptions of more frequent antisocial behavior among best friends and groups. Higher quality friendships were associated with less adolescent-reported antisocial behavior in seventh grade but not eighth grade. Neither dyadic friendship nor group relationship qualities were related to teacher-reported antisocial behavior. Those bivariate relationships indicated that best friend and group antisocial behavior were moderately strong predictors of adolescents' own antisocial behavior. However, the relationships also indicated that adolescents report more frequent peer antisocial behavior when relationships are perceived as being of lower quality.

Table 2. Bivariate Correlations Among Peer Relationship and Antisocial Behavior Variables.

| Bivariate Correlations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer Relationship Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. |

| 1. Dyadic friendship qualities | |||||||

| 2. Best friend antisocial behavior | −.28*** | ||||||

| 3. Group relationship qualities | .43** | −.15** | |||||

| 4. Group antisocial behavior | −.30*** | .58*** | −.22*** | ||||

| 5. Grade 7 YSR (adolescent report) | −.13* | .46*** | −.05 | .58*** | |||

| 6. Grade 7 TRF (teacher report) | −.03 | .31*** | −.07 | .28*** | .23*** | ||

| 7. Grade 8 YSR | −.08 | .31*** | −.05 | .35*** | .47*** | .21*** | |

| 8. Grade 8 TRF | −.08 | .29*** | −.09 | .27*** | .30*** | .46*** | .27*** |

Note: n = 281 through 431.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Peer Relationships and Concurrent: (Grade 7) Behavioral Adjustment

Moderated multiple regression analyses were conducted to test the hypotheses that relationship qualities and peer antisocial behavior would interact to predict adolescents' own antisocial behavior and that those relationships would vary as a function of adolescent gender. Best friend and group variables were analyzed separately with the Grade 7 adolescent-reported and teacher-reported antisocial behavior scores serving as dependent variables. Initially, all participants (with the exception of one outlier) for whom any Grade 7 data were available were included in those analyses. Analyses with teacher-reported antisocial behavior as the dependent variable were repeated excluding adolescents with Grade 7, but not Grade 8, teacher data. Likewise, analyses with adolescent-reported antisocial behavior as the dependent variable were repeated excluding adolescents with Grade 7, but not Grade 8, self-report data. To maximize statistical power and to present the most reliable estimates, results from the full sample will be reported. However, for the one occasion when the results were different in the two samples, results from both samples will be reported.

In each analysis, adolescent gender, relationship qualities, and perceptions of peer behavior were entered in the first step. To reduce the chances of model misspecification when evaluating interactions among correlated predictors (see Ganzach, 1997), squared relationship qualities and peer behavior terms were entered in the second step. Two-way interactions (Gender  Relationship Qualities, Gender

Relationship Qualities, Gender  Peer Behavior, and Relationship Qualities

Peer Behavior, and Relationship Qualities  Peer Behavior) were entered in a series of third steps to control for all main and quadratic effects, and the three-way interaction was entered in the fourth step to control for all main effects, quadratic effects, and two-way interactions. Two-way interactions were tested separately to maximize power to detect significant interactions (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). Because relationship qualities and peer antisocial behavior were correlated, each variable was centered (i.e., the sample mean was subtracted from each participant's score) before creating quadratic and multiplicative interaction terms to reduce multicollinearity (Jaccard, Turisi, & Wan, 1990). A significant Relationship Qualities

Peer Behavior) were entered in a series of third steps to control for all main and quadratic effects, and the three-way interaction was entered in the fourth step to control for all main effects, quadratic effects, and two-way interactions. Two-way interactions were tested separately to maximize power to detect significant interactions (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). Because relationship qualities and peer antisocial behavior were correlated, each variable was centered (i.e., the sample mean was subtracted from each participant's score) before creating quadratic and multiplicative interaction terms to reduce multicollinearity (Jaccard, Turisi, & Wan, 1990). A significant Relationship Qualities  Peer Behavior interaction term would provide support for the hypothesis that relationship qualities moderate the relations between adolescents' own and peers' antisocial behavior. A significant Relationship Qualities

Peer Behavior interaction term would provide support for the hypothesis that relationship qualities moderate the relations between adolescents' own and peers' antisocial behavior. A significant Relationship Qualities  Peer Behavior

Peer Behavior  Gender interaction would indicate that the pattern of moderation differs for boys and for girls. Interactions were evaluated based on the fitted regression equations.

Gender interaction would indicate that the pattern of moderation differs for boys and for girls. Interactions were evaluated based on the fitted regression equations.

Best friends

The standardized beta coefficients for the best friend attributes are shown in Table 3. The best friendship main effects and interactions accounted for 25% and 16% of the variance in adolescent-reported and teacher-reported antisocial behavior, respectively. Perceptions of best friend antisocial behavior remained a significant predictor of adolescent-reported and teacher-reported antisocial behavior controlling for dyadic friendship qualities and gender. The quadratic best friend antisocial behavior term also was a significant predictor of teacher-reported antisocial behavior, indicating accelerated levels of antisocial behavior at high levels of best friend antisocial behavior. Teachers also reported more frequent antisocial behavior among boys than among girls. Two different interaction terms were significant predictors of antisocial behavior. Perceived best friend antisocial behavior was a stronger predictor of adolescent-reported antisocial behavior for girls than for boys (ΔR2 = .01, p < .05) and friendship qualities interacted with best friend antisocial behavior to predict adolescent-reported (ΔR2 = .02, p < .01) and teacher-reported antisocial behavior (ΔR2 = .02, p < .001).

Table 3. Antisocial Behavior Regressed on Best Friendship and Group Attributes (standardized betas).

| Grade 7 | Grade 8 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best Friendship | Friendship Group | Best Friendship | Friendship Group | |||||

| Variables |

YSRa n = 407 |

TRFb n = 391 |

YSR n = 316 |

TRF n = 303 |

YSR n = 350 |

TRF n = 339 |

YSR n = 268 |

TRF n = 264 |

| First step | ||||||||

| Grade 7 antisocial behaviorc | .43*** | .41*** | .42*** | .38*** | ||||

| Adolescent gender (0 = male, 1 = female) | −.05 | −.12* | −.07 | −.15** | .03 | −.03 | .02 | −.03 |

| Antisocial behavior | .46*** | .32*** | .58*** | .25*** | .11* | .16** | .12+ | .16** |

| Relationship qualities | .02 | .08 | .07 | .07 | −.01 | −.01 | .03 | −.04 |

| Second step | ||||||||

| Antisocial behavior squared | −.01 | .18** | −.03 | −.02 | .02 | .15* | −.11 | .10 |

| Relationship qualities squared | −.08 | −.04 | .04 | .01 | −.02 | −.02 | −.03 | −.05 |

| Series of third steps | ||||||||

Relationship Qualities  Antisocial Behavior Antisocial Behavior |

.16** | .18*** | .16+ | −.08 | −.03 | .05 | .06 | .20+ |

Relationship Qualities  Gender Gender |

.04 | −.02 | .12 | .22 | .03 | .01 | .19 | .15 |

Antisocial Behavior  Gender Gender |

.15* | −.07 | −.06 | −.15+ | .04 | .10 | .01 | .16+ |

| Fourth step | ||||||||

Relationship Qualities  Antisocial Antisocial |

||||||||

Behavior  Gender Gender |

.04 | −.05 | .36* | .37+ | .02 | −.05 | −.07 | −.06 |

| Gender and peer relationship variables | ||||||||

| Main effects R2 | .21*** | .11*** | .33*** | .09*** | .01 | .03*** | .01 | .03* |

| Peer relationship interactions R2 | .03** | .03** | .02* | .02+ | .01 | .01 | .01 | .02 |

| Total R2 | .25*** | .16*** | .36*** | .11*** | .24*** | .26*** | .26*** | .24*** |

YSR is adolescent-reported antisocial behavior.

TRF is teacher-reported antisocial behavior.

Grade 7 adolescent-reported antisocial behavior served as a covariate when predicting Grade 8 adolescent-reported antisocial behavior and Grade 7 and teacher-reported antisocial behavior served as a covariate when predicting Grade 8 teacher-reported antisocial behavior.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

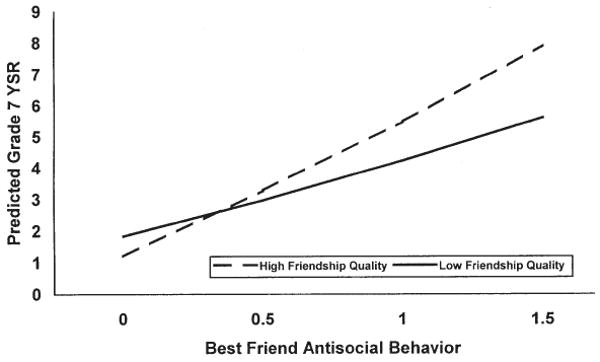

The coefficient estimates from the model, including the main effects, quadratic terms, and the single two-way interaction, were used to interpret the significant Friendship Quality  Friend Antisocial Behavior interaction. Because the primary interest was in predicting adolescents' own antisocial behavior from peer behavior, the best friend antisocial behavior slope (i.e., unstandardized beta) was computed at high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) levels of dyadic friendship qualities (see Jaccard et al., 1990). When predicting adolescent-reported and teacher-reported antisocial behavior, perceptions of best friend antisocial behavior were related more strongly to antisocial behavior when the friendship qualities scores were high (slopes = 4.17 and 2.16, for adolescent-reported and teacher-reported antisocial behavior, respectively) than when the friendship qualities scores were low (slopes = 2.29 and .28). In other words, adolescents who described higher-quality friendships reported being more similar to their best friends in terms of antisocial behavior than did adolescents who described lower-quality friendships. To illustrate the interaction, the plotted predicted values of adolescent-reported antisocial behavior for high and low values of friendship quality are shown in Figure 1. The upward slope of both lines evidences the strong relationship between best friend antisocial behavior and adolescent-reported antisocial behavior. The interaction between best friend antisocial behavior and dyadic friendship qualities is illustrated best by the difference in the slopes of the high and low friendship qualities lines; the high friendship qualities line is steeper than the low friendship qualities line and the lines cross near the origin.

Friend Antisocial Behavior interaction. Because the primary interest was in predicting adolescents' own antisocial behavior from peer behavior, the best friend antisocial behavior slope (i.e., unstandardized beta) was computed at high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) levels of dyadic friendship qualities (see Jaccard et al., 1990). When predicting adolescent-reported and teacher-reported antisocial behavior, perceptions of best friend antisocial behavior were related more strongly to antisocial behavior when the friendship qualities scores were high (slopes = 4.17 and 2.16, for adolescent-reported and teacher-reported antisocial behavior, respectively) than when the friendship qualities scores were low (slopes = 2.29 and .28). In other words, adolescents who described higher-quality friendships reported being more similar to their best friends in terms of antisocial behavior than did adolescents who described lower-quality friendships. To illustrate the interaction, the plotted predicted values of adolescent-reported antisocial behavior for high and low values of friendship quality are shown in Figure 1. The upward slope of both lines evidences the strong relationship between best friend antisocial behavior and adolescent-reported antisocial behavior. The interaction between best friend antisocial behavior and dyadic friendship qualities is illustrated best by the difference in the slopes of the high and low friendship qualities lines; the high friendship qualities line is steeper than the low friendship qualities line and the lines cross near the origin.

Figure 1. Predicted values of adolescent-reported antisocial behavior (YSR) as a function of dyadic friendship qualities and best friend antisocial behavior.

In an attempt to determine which friendship qualities dimensions were responsible for moderating the relation between perceived best friend antisocial behavior and adolescents' own antisocial behavior, analyses were repeated using each of the seven friendship qualities scale scores. The security and companionship interactions were significant predictors of teacher-reported antisocial behavior. The help, security, help-provided, and security-provided interactions predicted adolescent-reported antisocial behavior. Inspection of the betas indicated greater perceived similarity in antisocial behavior when the friendships were reported to be high in security, help, and companionship than when the friendships were reported to be low in security, help, and companionship.

Groups

The regression coefficients for the friendship group attributes also are shown in Table 3. The peer relationship variables accounted for 36% and 11% of the variance in adolescent-reported and teacher-reported antisocial behavior, respectively. Perceptions of group antisocial behavior remained a significant predictor of adolescent-reported and teacher-reported antisocial behavior, controlling for group relationship qualities and gender. Again, teachers reported more antisocial behavior among boys than among girls. The three-way Group Antisocial Behavior  Group Quality

Group Quality  Gender interaction was a significant predictor of adolescent-reported antisocial behavior (ΔR2 = .01, p < .05). The three-way interaction tended toward significance as a predictor of teacher-reported antisocial behavior using the full sample. However, the three-way interaction was nonsignificant when the analysis was repeated using data from adolescents for whom teacher reports were available in Grade 7 and Grade 8. Interpretation of the three-way interaction revealed that group antisocial behavior was associated more strongly with adolescent-reported antisocial behavior when girls reported higher-quality group relationships than when girls reported lower-quality group relationships (slopes = −.01 and 1.20, for low- and high-quality group relationships, respectively). The difference was minimal for boys (slopes = 2.35 and 2.25, for low- and high-quality group relationships, respectively). In other words, all boys and the girls with higher-quality group relationships perceived the level of antisocial behavior among their friendship group members as similar to their own level of antisocial behavior. There was no correspondence between perceptions of group antisocial behavior and adolescents' own antisocial behavior among girls reporting lower-quality group relationships.

Gender interaction was a significant predictor of adolescent-reported antisocial behavior (ΔR2 = .01, p < .05). The three-way interaction tended toward significance as a predictor of teacher-reported antisocial behavior using the full sample. However, the three-way interaction was nonsignificant when the analysis was repeated using data from adolescents for whom teacher reports were available in Grade 7 and Grade 8. Interpretation of the three-way interaction revealed that group antisocial behavior was associated more strongly with adolescent-reported antisocial behavior when girls reported higher-quality group relationships than when girls reported lower-quality group relationships (slopes = −.01 and 1.20, for low- and high-quality group relationships, respectively). The difference was minimal for boys (slopes = 2.35 and 2.25, for low- and high-quality group relationships, respectively). In other words, all boys and the girls with higher-quality group relationships perceived the level of antisocial behavior among their friendship group members as similar to their own level of antisocial behavior. There was no correspondence between perceptions of group antisocial behavior and adolescents' own antisocial behavior among girls reporting lower-quality group relationships.

Peer Relationships and Subsequent: (Grade 8) Antisocial Behavior

A similar sequence of regression analyses was conducted with the Grade 8 antisocial behavior scores serving as dependent variables and the Grade 7 antisocial behavior scores serving as covariates. Specifically, when predicting Grade 8 adolescent-reported antisocial behavior, Grade 7 adolescent-reported antisocial behavior was included as a covariate in the first step along with gender, peer antisocial behavior, and peer relationship quality. Grade 7 teacher-reported antisocial behavior served as the covariate when predicting Grade 8 teacher-reported antisocial behavior. Those analyses also are summarized in Table 3.

Best friends

After controlling for Grade 7 antisocial behavior, the best friend variables accounted for 2% and 4% of the variance in adolescent-reported and teacher-reported Grade 8 antisocial behavior, respectively. Perceptions of best friend antisocial behavior remained a significant predictor of adolescent-reported and teacher-reported antisocial behavior, and the quadratic best friend antisocial behavior term remained a significant predictor of teacher-reported antisocial behavior. The interaction terms were no longer significant predictors of antisocial behavior.

Groups

After controlling for Grade 7 antisocial behavior, the friendship group variables accounted for 2% and 5% of the variance in adolescent-reported and teacher-reported Grade 8 antisocial behavior, respectively. Perceptions of group antisocial behavior remained a significant predictor of teacher-reported antisocial behavior and tended toward significance as a predictor of adolescent-reported antisocial behavior. Two interaction terms tended toward significance as predictors of teacher-reported antisocial behavior. Group antisocial behavior tended to be a stronger predictor of teacher-reported antisocial behavior for girls than for boys, and group antisocial behavior tended to be a stronger predictor of teacher-reported antisocial behavior in the context of high-quality friendships.

Discussion

Hartup (1996) highlighted the need for simultaneous examinations of multiple peer relationship attributes and interactions among those attributes. The current study shows that among early adolescents, relations between best friend antisocial behavior and adolescents' own antisocial behavior were moderated by the qualities of the friendship. Perceptions of the antisocial behavior of a particular best friend were associated most strongly with participants' own antisocial behavior in the context of friendships described as being high in help, companionship, and security. That pattern of moderation applied to the dyadic friendships of boys and of girls. The pattern was repeated for females in the friendship group domain. Specifically, group antisocial behavior was a stronger predictor of antisocial behavior among female adolescents who reported high-quality group relationships than among those females who reported that they were not as involved with their groups or did not enjoy group membership. In general, the effect sizes were small and the evidence of moderation was limited to concurrent antisocial behavior.

Analyses described in this study tested hypotheses drawn from two processes that might account for the links between adolescents' perceptions of peer relationship attributes and adolescents' own antisocial behavior. Because the peer relationship data were collected at the same time or earlier than the outcome data, the direction of effects cannot be fully addressed. It is possible that adolescent peer relationship experiences influence behavior, and it equally is possible that the behavior problems shown by adolescents influence their peer relationships. The most likely scenario is that both of those processes occur together, such that adolescent behavior problems are reflected in adolescent peer relationship perceptions and experiences and that peer relationship experiences forecast changes in behavior (Fisher & Bauman, 1988; Tremblay et al., 1995).

The results indicated that adolescents' perceptions of peer relationship qualities change the meaning of perceptions of peers' antisocial behavior. Specifically, whereas close, supportive, dyadic friendships often are described as positive experiences that can provide adolescents with social support and entertainment, the current study indicated that friendships of this type also might have provided adolescents with the opportunity to engage in destructive behaviors and provided the social support to continue involvement in such behavior (see Hartup, 1996). Help, companionship, and security were the friendship qualities that appeared to moderate most strongly the impact of adolescents' perceptions of friends' antisocial behavior. High levels of perceived conflict in the friendships did not appear to diminish the impact of the friends' behavior. Thus, early adolescents might be influenced most by perceptions of their best friends' behavior when they spend a lot of time with their best friends, provide and receive instrumental assistance from best friends, and when the friends serve as confidants. Alternatively, adolescents might feel most secure, provide more instrumental assistance, and spend more time with their friends when they perceive behavioral similarity. Moreover, engaging in antisocial behavior with friends might serve to bolster perceptions of intimacy and security (Lightfoot, 1997). For example, adolescents might be unlikely to engage in antisocial behavior, or even to discuss their involvement in antisocial behavior, with peers who they feel actively would discourage such behavior but readily share their stories and engage in antisocial activities with like-minded individuals.

Those results are consistent with at least two relationship processes that might account for behavioral similarity. One possibility is that only when acquaintances are similar in terms of involvement in antisocial behavior will they become close friends (Hartup, 1996). It is possible also that friends have more opportunities to influence one another's behavior when the friends spend a lot of time together and feel secure in the friendship. In the former, adolescents might imitate the behavior of the desired friends or might choose to emphasize their own skills and interests that are compatible with the friends' skills and interests. In the early stages of friendships, particularly among antisocial adolescents, it might be necessary to have some similar antisocial interests before developing trust and intimacy. In the latter process, through spending time together, helping one another with problems, and sharing ideas adolescent friends might become more similar over time (Dishion et al., 1994). Although those two processes appear to be very different, both are likely to play important roles at differing times in friendship establishment and maintenance processes. Longitudinal studies that follow the formation of specific friendships are needed to disentangle those two processes. However, it is likely that the two processes are blended throughout the life of a friendship, with increases in behavioral concordance serving to strengthen the qualities of the relationship, which in turn provides the friends with greater influence over one another's behavior. Nonetheless, the finding of Aloise-Young and colleagues (1994) that behavioral concordance, or the lack thereof, did not predict friendship resolution, indicated that behavioral concordance might be more necessary during the early stages of friendship formation and might be less influential in well-established relationships.

Other studies have documented interaction effects among peer relationship features (e.g., Agnew, 1991; Aloise-Young et al., 1994; Wills & Vaughan, 1989), but the current study was the first to test the impact of peer antisocial behavior as a function of relationship qualities in multiple peer relationship contexts and to test the applicability of the interactions to boys' and to girls' peer relationships. The hypothesized pattern of moderation was identified in the dyadic friendship and the friendship group context although the pattern was limited to girls' friendship group relationships. The evidence for gender differences in the group but not dyadic friendship context is surprising. Girls, as compared to boys, have reported valuing close relationships and having more intimacy and closeness in their friendships (e.g., Bukowski et al., 1994; Hartup, 1993). If dyadic friendships are assumed to be, on average, more intimate than group relationships, gender differences should be identified more easily in the dyadic friendship context. In the current study, girls did report higher-quality dyadic friendships than did boys, but girls also reported higher-quality group relationships than did boys. If the three-way interaction is interpreted from an influence perspective, it might be evidence that girls who do not feel attached to their groups might be the only group resistant to the influence of high levels of group antisocial behavior. From a selection perspective, it might be evidence that similarity in antisocial behavior is more relevant to the formation and establishment of high-quality group relationships for girls than for boys. Boys' groups might be organized around other activities or boys might be willing to tolerate more diversity in antisocial behavior. Yet another possibility is that the group-relationship quality measure tapped dimensions of group quality that are more relevant for girls than for boys. The results of the current study indicated that adolescent descriptions of group qualities have some predictive utility, but a more reliable and comprehensive assessment and treatment of group relationship qualities, perhaps to address help and security issues, is needed.

As described previously, there was general support for the relationship quality moderation hypothesis and some evidence consistent with the gender difference hypothesis when predicting concurrent antisocial behavior problems. However, neither hypothesis was supported in longitudinal analyses. Best friend and group antisocial behavior predicted later antisocial behavior, but the relationship was not moderated by relationship qualities. In interpreting the lack of longitudinal findings, several possibilities come to mind.1 First, those results might be evidence that the friendships and friendship group relations changed substantially in the 16 months between assessments. Although many of the adolescents reported that their friendships had lasted for several years, it is unknown whether those friendships continued through eighth grade. Many adolescent friendships last less than a single school year, and it is common for adolescents to change friendship groups over the course of a year (Bukowski et al., 1994; Savin-Williams & Berndt, 1990; Urberg, Değirmencioğlu, Tolson, & Halliday-Schner, 1995). A second interpretation is that the reduction in the sample of adolescents for whom Grade 8 antisocial behavior scores were available and the associated reduction in statistical power made the identification of significant interactions unlikely. However, analyses repeated with the longitudinal sample provided results that were consistent with the analyses using the full sample. It is possible that the high stability in antisocial behavior from seventh through eighth grades and the marginal reliability of the relationship qualities scales, particularly the group qualities scale, limited the amount of variance that could be explained by the peer relationship interactions. Another possibility is that the moderating role of relationship quality is stronger at different points in adolescence. A final interpretation of the limited longitudinal results is that the concordance in behavior among adolescent friends might drive the assessment of friendship quality. If the behavioral concordance predates or is a prerequisite for the formation of secure friendships and high-quality group relationships as the selection perspective indicates, then longitudinal relations might be limited after controlling for continuity in antisocial behavior. It is important to keep in mind that the main effects of peer antisocial behavior remained significant in the analyses of longitudinal data, which might indicate that peer behavior does continue to forecast adolescent antisocial behavior.

Limitations and Recommendations

In comparing the results presented in this article with other studies, the reader should keep in mind that all participants were early adolescents, that the measure of friendship group quality might not tap all relevant dimensions, that the friendship and group relationship qualities measures were reliable only marginally, and that the analyses might have been biased by the fluctuation in sample size across analyses. Moreover, although the effects were statistically significant and relatively consistent, the effect sizes generally were small. Friendship and group relationship qualities appear to be important aspects of adolescent peer relationships. Whereas considerable effort has been directed toward developing comprehensive and reliable measures of dyadic friendship qualities (Bukowski et al., 1994; Parker & Asher, 1993), more work is needed to develop comprehensive and reliable measures of group relationship qualities. Limiting the sample to those adolescents who described best friendship and friendship group relationships or to participants with complete data would have reduced sample size fluctuations. However, either approach would have excluded a sizable minority of participants, resulting in reduced statistical power and the exclusion of those adolescents who had a best friend but were not members of a friendship group.

It is also important to consider that all of the peer relationship information was obtained from single informants, namely the adolescents themselves. Although adolescents often are asked to report on their friends' behavior (e.g., Berndt & Keefe, 1995; Chassin, Presson, Todd, Rose, & Sherman, 1998), this practice might bias results by providing evidence of stronger associations between peer relationship experiences and adjustments than would be found using multi-informant measures (Hartup, 1996). However, a recent study provided evidence of convergence between adolescent reports and school-based sociometric methodologies for identifying friendship groups or cliques (Cairns, Leung, Buchanan, & Cairns, 1995), and other studies have reported similar results using friend reports of their own behavior and adolescent reports of their friends' behavior (e.g., Berndt & Keefe, 1995; Fisher & Bauman, 1988). Asking adolescents about their friendships and peer relationships better reflects adolescents' perceptions of their peer relationships (Hartup, 1996) and is not limited to adolescents with friends who are participating in the study or attending the same school.

The primary contribution for this study is the evaluation of relationship qualities as moderators of the relationships between perceptions of peer antisocial behavior and adolescents' own antisocial behavior. Perceived peer antisocial behavior was found to be a strong correlate of adolescent-reported and teacher-reported antisocial behavior. In the context of a secure and supportive friendship the relation between perceptions of peer antisocial behavior and adolescents' own antisocial behavior was particularly strong. The lack of longitudinal evidence of moderation is consistent with the proposition that perceived concordance in antisocial behavior provides the impetus for developing close and secure friendships. However, prospective longitudinal research is needed to trace the interplay between behavioral concordance and friendship quality to clarify whether behavioral concordance predates or follows from secure and intimate peer relationships.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH 42498) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD 30572) to G. S. Pettit, K. A. Dodge, and J. E. Bates. We are grateful to the Child Development Project families for their participation.

Footnotes

Several of these alternatives were suggested by an anonymous reviewer.

Portions of this article were presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Washington, D.C., April 1997. Portions of these data also appeared in an unpublished doctoral dissertation by the first author, at Auburn University.

Contributor Information

Robert D. Laird, University of Rhode Island

Gregory S. Pettit, Auburn University

Kenneth A. Dodge, Duke University

John E. Bates, Indiana University

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Teacher's Report Form and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self Report Form and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991b. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew R. The interactive effects of peer variables on delinquency. Criminology. 1991;29:47–72. [Google Scholar]

- Aloise-Young PA, Graham JW, Hansen WB. Peer influence on smoking initiation during early adolescence: A comparison of group members and group outsiders. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1994;79:281–287. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.79.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ. Developmental changes in conformity to peers and parents. Developmental Psychology. 1979;15:608–616. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ, Keefe K. Friends' influence on adolescents' adjustment to school. Child Development. 1995;66:1312–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB. Peer groups and peer cultures. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 171–196. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Clasen DR, Eicher SA. Perceptions of peer pressure, peer conformity dispositions, and self-reported behavior among adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 1986;4:521–530. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Lohr MJ. Peer-group affiliation and adolescent self-esteem: An integration of ego-identity and symbolic interaction theories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:47–55. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D. Intimacy of friendship, interpersonal competence, and adjustment during preadolescence and adolescence. Child Development. 1990;61:1101–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Hoza B, Boivin M. Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence: The development and psychometric properties of the friendship qualities scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1994;11:471–484. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RB, Leung M, Buchanan L, Cairns BD. Friendships and social networks in childhood and adolescence: Fluidity, reliability, and interrelations. Child Development. 1995;66:1330–1345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Todd M, Rose JS, Sherman SJ. Maternal socialization of adolescent smoking: The intergenerational transmission of parenting and smoking. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1189–1201. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Andrews DW, Crosby L. Antisocial boys and their friends in early adolescence: Relationship characteristics, quality, and interactional process. Child Development. 1995;66:139–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Griesler PC. Peer adaptations in the development of antisocial behavior. In: Huesmann LR, editor. Current perspectives on aggressive behavior. New York: Plenum; 1994. pp. 61–95. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Stoolmiller M, Skinner ML. Family, school, and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science. 1990;250:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.2270481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE. The contribution of influence and selection to adolescent peer group homogeneity: The case of adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:653–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LA, Bauman KE. Influence and selection in the friend-adolescent relationship: Findings from studies of adolescent smoking and drinking. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1988;18:289–314. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W. The measurement of friendship perceptions: Conceptual and methodological issues. In: Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF, Hartup WW, editors. The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children's perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Ganzach Y. Misleading interaction and curvilinear terms. Psychological Methods. 1997;2:235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Gavin LA, Furman W. Age differences in adolescents' perceptions of their peer groups. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:827–834. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinan MT. Patterns of cliquing among youth. In: Foot HC, Chapman AJ, Smith JR, editors. Friendship and social relations in children. New York: John Wiley; 1980. pp. 321–342. [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW. Adolescents and their friends. In: Larson B, editor. Close friendships in adolescence. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1993. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW. The company they keep: Friendships and their developmental significance. Child Development. 1996;67:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch BJ, DuBois DL. The relation of peer social support and psychological symptomatology during the transition to junior high school: A two-year longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1992;20:333–347. doi: 10.1007/BF00937913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social position. Yale University; New Haven: 1975. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR, Moise JF. The stability and continuity of aggression from early childhood to young adulthood. In: Flannery DJ, Huff CR, editors. Youth violence: Prevention, intervention, and social policy. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1998. pp. 73–95. [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Turisi R, Wan CK. Interaction effects in multiple regression (Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, series no 07-072) Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoot C. The culture of adolescent risk-taking. New York: Guilford; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Newman PR, Newman BM. Early adolescence and its conflict: Group identity versus alienation. Adolescence. 1976;11:261–274. [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Asher SR. Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA. Supportive parenting, ecological context, and children's adjustment: A seven-year longitudinal study. Child Development. 1997;68:908–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Berndt TJ. Friendship and peer relations. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 277–307. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Wu CI, Conger RD, Lorenz FO. Two routes to delinquency: Differences between early and late starters in the impact of parenting and deviant peers. Criminology. 1994;32:247–275. [Google Scholar]

- Tolson JM, Urberg KA. Similarity between adolescent best friends. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1993;8:274–288. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay RE, Masse LC, Vitaro F, Dobkin PL. The impact of friends' deviant behavior on early onset of delinquency: Longitudinal data from 6 to 13 years of age. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:649–667. [Google Scholar]

- Urberg KA, Değirmencioğlu SM, Pilgrim C. Close friend and group influence on adolescent cigarette smoking and alcohol use. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:834–844. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urberg KA, Değirmencioğlu SM, Tolson JM, Halliday-Scher K. The structure of adolescent peer networks. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:540–547. [Google Scholar]

- Warr M, Stafford M. The influence of delinquent peers: What they think or what they do? Criminology. 1991;29:851–865. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Vaughan R. Social support and substance use in early adolescence. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1989;12:321–339. doi: 10.1007/BF00844927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]