Abstract

Intimal hyperplasia is a major cause of restenosis after the interventional or surgical treatment of occlusive arterial disease. We investigated the effects of clopidogrel, calcium dobesilate, nebivolol, and atorvastatin on the development of intimal hyperplasia in rabbits after carotid venous bypass surgery.

We divided 40 male New Zealand rabbits into 4 study groups and 1 control group. After occluding the carotid arteries of the rabbits, we constructed jugular venous grafts between the proximal and the distal segments of the occluded artery. Thereafter, group 1 (control) received no medication. We administered daily oral doses of clopidogrel to group 2, calcium dobesilate to group 3, nebivolol to group 4, and atorvastatin to group 5. The rabbits were killed 28 days postoperatively. The arterialized jugular venous grafts were extracted for histopathologic examination.

Intimal thicknesses were 42.87 ± 6.95 μm (group 2), 46.5 ± 9.02 μm (group 3), 34.12 ± 5.64 μm (group 4), and 48.37 ± 6.16 μm (group 5), all significantly less than the 95.12 ± 9.93 μm in group 1 (all P < 0.001). Medial thicknesses were 94 ± 6 μm (group 2), 101.5 ± 13.52 μm (group 3), 90.5 ± 9.69 μm (group 4), and 101.37 ± 7.99 μm (group 5), all significantly thinner than the 126.62 ± 13.53 μm in group 1 (all P < 0.001).

In our experimental model of carotid venous bypass grafting in rabbits, clopidogrel, calcium dobesilate, nebivolol, and atorvastatin each effectively reduced the development of intimal hyperplasia. Herein, we discuss our findings and review the medical literature.

Key words: Anastomosis, surgical; cardiovascular agents/administration & dosage; carotid arteries/drug/effects/pathology/surgery; carotid stenosis/prevention & control; coronary artery disease/drug therapy/prevention & control; coronary restenosis/drug therapy; disease models, animal; hyperplasia/drug therapy/etiology/prevention & control; jugular veins/transplantation; rabbits; tunica intima/drug effects/pathology

Intimal hyperplasia is a major cause of restenosis after the interventional or surgical treatment of occlusive arterial diseases.1–3 Intimal hyperplasia has been described as the adaptive process that takes place in response to hemodynamic stresses or injuries to the vascular bed.2,4 Some degree of endothelial injury always occurs after any percutaneous or surgical treatment of vascular disorders. The vascular endothelial layer routinely forms an anticoagulant layer by secreting various mediators that enable blood flow.5 This anticoagulant and its homeostatic properties are lost in cases of vascular injury, and a procoagulant surface for the elements of blood is formed. The chief pathologic process involves platelet aggregation and degranulation with proliferation and migration of vascular smooth-muscle cells, along with an increase in matrix proteins at the site of endothelial injury. This adaptive process results in intimal hyperplasia, a phenomenon that is seen often upon clinical follow-up of invasively treated occlusive vascular disease. In numerous studies, restenosis due to intimal hyperplasia has been as high as 20% to 50%.6–8

We investigated the effects of clopidogrel, calcium dobesilate, nebivolol, and atorvastatin on the development of intimal hyperplasia in rabbits that had undergone venous carotid artery bypass. This method was similar to clinical coronary artery or peripheral arterial bypass surgery, and it was practical, replicable, and inexpensive. Our findings and a literature review are presented here.

Materials and Methods

Study Protocol

This study was conducted at the Medical & Surgical Research Center of Ondokuz Mayis University, and the protocol was approved by the university's Ethical Committee of Animal Studies. We experimented upon 40 male New Zealand rabbits, each 2,500 to 3,000 g in weight and of similar age. The animals were furnished by the university's Surgical Research Center, whose staff provided humane care throughout. The rabbits were kept in a daylit environment, in specially designed cages, at a mean temperature of 20 °C. They were randomly divided into 4 study groups and 1 control group of 8 animals each.

Anesthetic and Surgical Technique

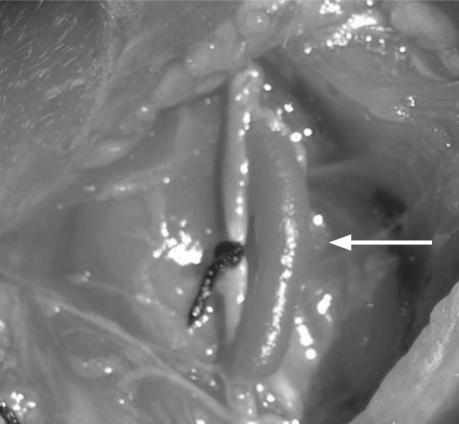

General anesthesia was achieved in each rabbit upon the administration of 10 mg/kg of ketamine hydrochloride intravenously and 3 mg/kg of xylazine intramuscularly. During each 2.5-hour operation, half of the above dosages were repeated every 45 minutes. Each animal was placed on the surgical table in supine position with cervical extension. Cefazolin sodium (10 mg/kg) was injected intramuscularly as prophylaxis against infection. A vertical 5-cm skin incision was performed, 1.5 cm to the right of and lateral to the anterior midline, in order to reach the carotid artery and jugular vein. After complete occlusion of the carotid artery was instituted by use of heavy silk ligature, each animal underwent a venous carotid artery bypass that was constructed between the proximal and distal portions of the carotid artery, with the accompanying jugular vein as the conduit. A single intravenous dose of 150 IU/kg of heparin was administered. Side branches of the jugular vein segment that was to be used as the bypass conduit were ligated with 4-0 silk sutures. Each bypass graft was at least 2.5 cm long. Proximal and distal anastomoses (length, 3 mm) were performed end-to-side with 9-0 polypropylene sutures. Pulsatile blood flow to the venous graft was confirmed. The carotid artery was ligated externally with 4-0 silk suture (Fig. 1). After hemostasis was achieved, the surgical site was closed. Intraoperatively, 1 rabbit died and was replaced. The subjects were protected from the effects of hypothermia for approximately 3 hours until they regained a normal activity level.

Fig. 1 Operative photograph of completed venous bypass graft (arrow) to the internal carotid artery

Medical Therapy

Postoperatively, the rabbits in group 1 (control group) were not medicated. Starting from the 5th postoperative hour, the 32 rabbits in the 4 study groups received their respectively assigned medication dosages once daily for 4 weeks, through nasoenteral tubes. The group 2 rabbits initially received 10 mg/kg of clopidogrel. The rabbits in group 3 were administered 100 mg/kg of calcium dobesilate. In group 4, the rabbits received 0.5 mg/kg of nebivolol. The group 5 rabbits were initially given 10 mg/kg of atorvastatin.

The effective dosages and safety limits of the pharmaceutical agents had been determined after a literature review. The animals in groups 3 and 4 tolerated the dosages; however, 2 rabbits each in groups 2 and 5 experienced diarrhea and lethargy and died on postoperative day 3. Necropsy studies revealed extensive liver necrosis. The dead rabbits were replaced, and the initial 10-mg/kg daily dosages of clopidogrel and atorvastatin, respectively, were reduced to 2.5 mg/kg in those 2 groups thereafter. The reduced dosages were tolerated well.

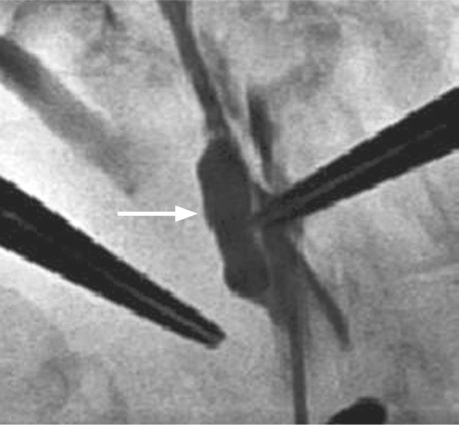

Graft patency was monitored daily with use of a hand-held Doppler ultrasonographic apparatus. Each graft's nonstenotic arterial waveform was recorded as evidence of patency. In addition, 1 rabbit in group 1 underwent carotid angiography (Fig. 2), and 1 each from groups 2 and 5 underwent duplex ultrasonographic examination. This last was deemed impractical for study purposes and was limited to those 2 animals.

Fig. 2 Postoperative carotid angiogram (arrow indicates venous bypass graft).

Results

After 4 weeks, the animals were placed under general anesthesia and were surgically explored. Arterialized pulsatile jugular vein grafts were seen in all. The carotid arteries were explanted 1 cm below and above the proximal and distal anastomoses, along with the graft and neighboring nerves, and the animals were humanely killed. One graft each in groups 1, 2, 3, and 5 was found to be occluded (overall patency, 90%).

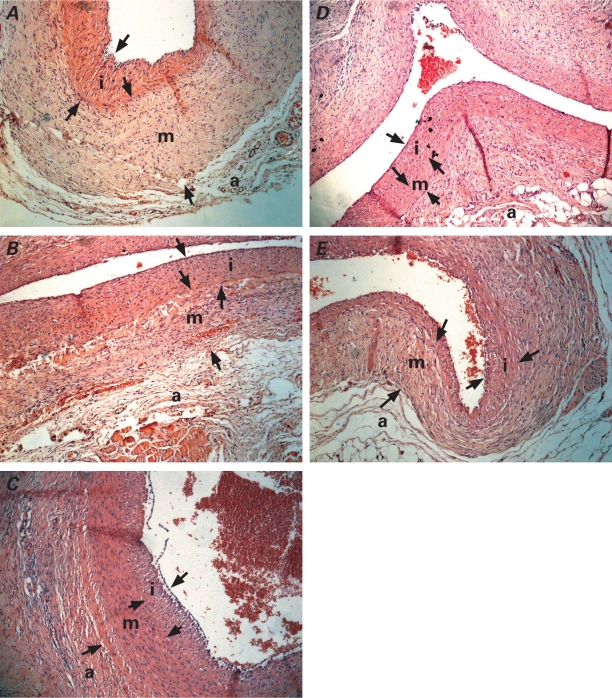

All of the explanted grafts were examined histopathologically (Fig. 3). After the tissue samples were irrigated with formaldehyde solution and fixed in buffered neutral formalin, microslices were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and with Verhoeff's stain, in order to show the elastic fibers in the walls of the jugular vein. The distance between the vascular lumen and internal elastic lamina was recorded as the intimal thickness. The distance between the internal and external elastic laminae was the medial thickness. Intimal–medial thickness ratios were then calculated.

Fig. 3 Histologic views of the explanted grafts at the end of the study. Lesser intimal hyperplasia can be seen in all of the study groups in the A) control group: B) clopidogrel group, C) calcium dobesilate group, D) nebivolol group, and E) atorvastatin group (H & E, orig. ×10).

a = adventitia; i = intima; m = media; arrows indicate borders of intimal and medial areas

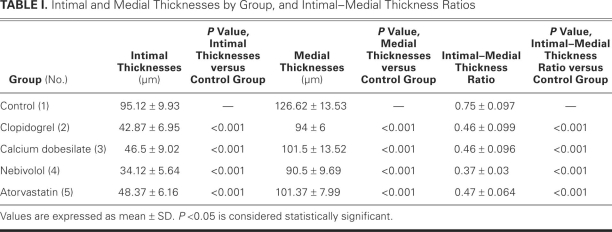

As Table I shows, intimal thicknesses were 95.12 ± 9.93 μm in group 1, 42.87 ± 6.95 μm in group 2, 46.5 ± 9.02 μm in group 3, 34.12 ± 5.64 μm in group 4, and 48.37 ± 6.16 μm in group 5. These were significantly lower in the study groups than in the control group (all P < 0.001). Intimal thickness was significantly lower in group 4 than in group 3 (P = 0.029) and in group 5 (P = 0.008). Similar results were noted when medial thicknesses were compared: 126.62 ± 13.53 mm in group 1, 94 ± 6 μm in group 2, 101.5 ± 13.52 mm in group 3, 90.5 ± 9.69 mm in group 4, and 101.37 ± 7.99 mm in group 5 (all study groups, P < 0.001 vs control group). Differences between the study groups were not statistically significant.

TABLE I. Intimal and Medial Thicknesses by Group, and Intimal–Medial Thickness Ratios

Intimal–medial thickness ratios were 0.75 ± 0.097 (group 1), 0.46 ± 0.099 (group 2), 0.46 ± 0.096 (group 3), 0.37 ± 0.03 (group 4), and 0.47 ± 0.064 (group 5). The ratios were significantly less in the study groups than in the control group (all P < 0.001). There were no significant differences between the study groups.

Statistical Analysis

Data were evaluated by use of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 10.0 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, Ill) and were stated as mean ± SD. Sample-size determination was made before the study was conducted. Levene's test of equality of error variances showed homogenous distribution of the data. Differences of means were calculated by using univariate analysis of variance. Homogenous subset analysis (with Bonferroni corrections) and post hoc Tukey HSD (honestly significantly different), Bonferroni, and Tamhane tests were also applied.

Discussion

Two major hypotheses have emerged regarding the pathologic processes that underlie the development of intimal hyperplasia after the treatment of occlusive vascular disease: response to injury, and adaptive remodeling. Currently, pharmaceutical agents (such as statins, nitric oxide [NO] donors or precursors, and clopidogrel) and surgical techniques (external mechanical barriers or internal degradable stents for grafts) are being applied to inhibit or retard intimal hyperplasia. Although many recent experimental studies in the area of molecular biology have produced seemingly effective results in animals (including the techniques of heparin bonding to polytetrafluoroethylene, free-radical scavenging, and photochemical therapies), no agent or technique has proved to be safe, applicable, and efficient in human beings.2–4,9

In different reports of intermediate and long-term follow-up, vein-graft restenosis rates range from 20% to 50%.2,6,10,11 In a rabbit model of balloon injury, it was shown that re-endothelization started as early as the 3rd day and that intimal hyperplasic activity peaked by the end of the 1st month.12 In a more recent study of the development of intimal hyperplasia, examination was recommended at the end of the 4th week.13 The pathogenesis may differ for arterial and venous allografts, but the same time period was used for venous allografts in different studies.9,14 In accordance with these data, we decided to examine the grafts after 4 weeks. We chose animals of similar age and weight. Because studies have indicated an impact of estrogens on the development of intimal hyperplasia,15,16 we worked with male rabbits.

Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) are probably the most important mediators in the proliferation of smooth-muscle cells and in migration initiation,17 with bFGF showing its effects on smooth-muscle-cell proliferation solely after endothelial injury.18 In vitro studies on human and animal smooth-muscle cells showed that nebivolol inhibits the smooth-muscle-cell proliferation and migration triggered by bFGF, and the smooth-muscle-cell proliferation initiated by PDGF.19,20 Oral treatment with nebivolol inhibited the formation of intimal hyperplasia in a venous bypass graft model, as in our study.

Calcium dobesilate was reported to protect endothelial functions and increase vascular relaxation in a model of aortic endothelial injury in rabbits.21 Dosage-related inhibition of rat aortic smooth-muscle-cell proliferation and DNA synthesis by calcium dobesilate (daily oral dosages, 30–200 mg/kg for 7 days) was shown in a study by Parés-Herbuté and colleagues.22 It was stated that this inhibition was reversible upon removal of the drug, in ex vivo and in vitro models. In the same study, it was shown that calcium dobesilate increases NO production by increasing NO synthase activity in addition to protecting against low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol oxidation.22 We inhibited intimal hyperplasia through the daily oral dosage of 100 mg/kg of calcium dobesilate in our venous graft model, seemingly in agreement with the earlier study.

Yamanouchi and colleagues23 reported that 10 mg/kg daily of a hydrophilic statin, pravastatin, significantly decreased intimal hyperplasia after 4 weeks in comparison with a control group, probably due to pleiotropic effects, in rabbits whose jugular veins were interpositionally grafted to the carotid artery. We preferred to use atorvastatin, which has well-known pleiotropic effects. In previous reports, 10-mg/kg daily dosages of atorvastatin were thought to be safe and effective,24–26 but we were obliged to reduce this to 2.5 mg/kg. We observed that this lower dosage of atorvastatin effectively inhibited the development of intimal hyperplasia.

Bledsoe and associates27 reported that a combination of clopidogrel and pravastatin in a rat carotid-endarterectomy model significantly decreased intimal hyperplasia and C-reactive protein levels. In another study,28 clopidogrel alone was not found to inhibit intimal hyperplasia effectively. On the other hand, Herbert and coworkers29 showed a dose-related inhibition of platelet aggregation and smooth-muscle-cell proliferation in a rabbit model of carotid artery injury, after 3 weeks of the daily administration of 25 mg/kg of clopidogrel. Zurbrügg and co-authors30 also reported that the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel inhibited smooth-muscle-cell proliferation and intimal-hyperplasia development more effectively than did aspirin treatment alone, in an experimental venous bypass graft model. Even though dosages of clopidogrel between 1 and 25 mg/kg daily have been reported to be safe and effective,29,31 our initial administration of 10 mg/kg daily caused death in our subject animals.

External absorbable synthetic materials, when used as barriers for tissue growth, are shown to inhibit neointimal formation and intimal hyperplasia.9,32 Immunosuppressive antineoplastic agents, such as leflunomide analogue FK778 or paclitaxel, were reported to be effective in the inhibition of intimal hyperplasia.33,34 Delayed re-endothelization was described as the reason for in-stent thrombosis. Probucol was effective in enhancing re-endothelization and inhibiting intimal hyperplasia.35 Irradiation is known to inhibit atherosclerotic-lesion formation, especially after coronary artery stenting.36–38

In many clinical and experimental studies, it was emphasized that NO donors can prevent the development of intimal hyperplasia. Kown and colleagues11 showed experimentally that polymers of a NO precursor, L-arginine, can inhibit neointimal hyperplasia formation and intimal–medial thickness ratios in a dose-related fashion.

All of the pharmaceutical agents that we used in our study groups inhibited the development of intimal hyperplasia. This effect might be due to specific or common metabolic pathway alterations. One of the most commonly used new-generation antiaggregant agents, clopidogrel, has also been found to inhibit smooth-muscle-cell proliferation, causing less intimal hyperplasia. Calcium dobesilate, which is chiefly used clinically to treat venous disorders (and which was reported to effect endothelial functional regulation, antiaggregation, and augmentation of NO synthase activity, and to reduce smooth-muscle-cell proliferation), also inhibited intimal hyperplasia in our experimental model. A new-generation β-blocking agent, nebivolol, is known to increase NO secretion and inhibit endothelin-1 release, in addition to its previously reported effects.19 In our study, we observed its powerful intimal hyperplasia-inhibiting effect. Administration of the cholesterol-lowering drug atorvastatin is almost routine in the treatment of atherosclerotic vascular diseases. Given its other pleiotropic effects (anti-inflammatory, endothelial protector, NO-secretion increase, smooth-muscle-cell proliferation and migration inhibition, and antiaggregation), atorvastatin was also effective in our study.

The treatment of occlusive vascular disease is not flawless, and the high restenosis rate due to intimal hyperplasia during intermediate and long-term follow-up constitutes an ongoing challenge. Clopidogrel, calcium dobesilate, nebivolol, atorvastatin, and other agents should be studied experimentally and clinically in order to gain a better understanding of the pathologic processes that are involved, and, eventually, to achieve a clear solution.

Acknowledgment

We thank Prof. Yuksel Bek of our faculty's Public Health Department for his invaluable help in the statistical analysis of our data.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Muzaffer Bahcivan, MD, Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, School of Medicine, Ondokuz Mayis University, 55139 Kurupelit, Samsun, Turkey E-mail: mbahcivan33@yahoo.com

References

- 1.Garas SM, Huber P, Scott NA. Overview of therapies for prevention of restenosis after coronary interventions. Pharmacol Ther 2001;92(2–3):165–78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Tessier DJ, Komalavilas P, Liu B, Kent CK, Thresher JS, Dreiza CM, et al. Transduction of peptide analogs of the small heat shock-related protein HSP20 inhibits intimal hyperplasia. J Vasc Surg 2004;40(1):106–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Nigri GR, Kossodo S, Waterman P, Fungaloi P, LaMuraglia GM. Free radical attenuation prevents thrombosis and enables photochemical inhibition of vein graft intimal hyperplasia. J Vasc Surg 2004;39(4):843–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Lin PH, Chen C, Bush RL, Yao Q, Lumsden AB, Hanson SR. Small-caliber heparin-coated ePTFE grafts reduce platelet deposition and neointimal hyperplasia in a baboon model. J Vasc Surg 2004;39(6):1322–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Luscher TF. Endothelial dysfunction in coronary artery disease. J Myocard Ischemia 1995;7(suppl 1):15–20.

- 6.Angelini GD, Newby AC. The future of saphenous vein as a coronary artery bypass conduit. Eur Heart J 1989;10(3):273–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Chan P, Munro E, Patel M, Betteridge L, Schachter M, Sever P, Wolfe J. Cellular biology of human intimal hyperplastic stenosis. Eur J Vasc Surg 1993;7(2):129–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Franklin SM, Faxon DP. Pharmacologic prevention of restenosis after coronary angioplasty: review of the randomized clinical trials. Coron Artery Dis 1993;4(3):232–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Vijayan V, Shukla N, Johnson JL, Gadsdon P, Angelini GD, Smith FC, et al. Long-term reduction of medial and intimal thickening in porcine saphenous vein grafts with a polyglactin biodegradable external sheath. J Vasc Surg 2004;40(5):1011–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Mallory FB. Pathological technique. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co.; 1942. p. 170–1.

- 11.Kown MH, Yamaguchi A, Jahncke CL, Miniati D, Murata S, Grunenfelder J, et al. L-arginine polymers inhibit the development of vein graft neointimal hyperplasia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001;121(5):971–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.More RS, Rutty G, Underwood MJ, Brack MJ, Gershlick AH. A time sequence of vessel wall changes in an experimental model of angioplasty. J Pathol 1994;172(3):287–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Dowd MB, Hemmrich K, Morrison WA. L-arginine reduces neointimal hyperplasia in cold-stored arterial allografts in a rabbit low-flow-through model. J Reconstr Microsurg 2007; 23(6):301–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Izzat MB, Mehta D, Bryan AJ, Reeves B, Newby AC, Angelini GD. Influence of external stent size on early medial and neointimal thickening in a pig model of saphenous vein bypass grafting. Circulation 1996;94(7):1741–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Ishibahshi T, Obayashi S, Sakamoto S, Aso T, Ishizaka M, Azuma H. Estrogen replacement effectively improves the accelerated intimal hyperplasia following balloon injury of carotid artery in the ovariectomized rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2006;47(1):37–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Watanabe T, Miyahara Y, Akishita M, Nakaoka T, Yamashita N, Iijima K, et al. Inhibitory effect of low-dose estrogen on neointimal formation after balloon injury of rat carotid artery. Eur J Pharmacol 2004;502(3):265–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Steed DL, Webster MW. Growth factors and wound healing. In: Haimovici H, editor. Haimovici's vascular surgery. 4th ed. Cambridge (MA): Blackwell Science; 1996. p. 230–6.

- 18.Edelman ER, Nugent MA, Smith LT, Karnovsky MJ. Basic fibroblast growth factor enhances the coupling of intimal hyperplasia and proliferation of vasa vasorum in injured rat arteries. J Clin Invest 1992;89(2):465–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Brehm BR, Wolf SC, Bertsch D, Klaussner M, Wesselborg S, Schuler S, Schulze-Osthoff K. Effects of nebivolol on proliferation and apoptosis of human coronary artery smooth muscle and endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res 2001;49(2):430–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Alfke H, Kleb B, Klose KJ. Nitric oxide inhibits the basic fibroblast growth factor-stimulated migration of bovine vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro. Vasa 2000;29(2):99–102. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Ruiz E, Tejerina T. Calcium dobesilate increases endothelium-dependent relaxation in endothelium-injured rabbit aorta. Pharmacol Res 1998;38(5):361–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Pares-Herbute N, Fliche E, Monnier L. Involvement of nitric oxide in the inhibition of aortic smooth muscle cell proliferation by calcium dobesilate. Int J Angiol 1999;8(5):5–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Yamanouchi D, Banno H, Nakayama M, Sugimoto M, Fujita H, Kobayashi M, et al. Hydrophilic statin suppresses vein graft intimal hyperplasia via endothelial cell-tropic Rho-kinase inhibition. J Vasc Surg 2005;42(4):757–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Bustos C, Hernandez-Presa MA, Ortego M, Tunon J, Ortega L, Perez F, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibition by atorvastatin reduces neointimal inflammation in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32(7):2057–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Auerbach BJ, Krause BR, Bisgaier CL, Newton RS. Comparative effects of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors on apo B production in the casein-fed rabbit: atorvastatin versus lovastatin. Atherosclerosis 1995;115(2):173–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Maeso R, Aragoncillo P, Navarro-Cid J, Ruilope LM, Diaz C, Hernandez G, et al. Effect of atorvastatin on endothelium-dependent constrictor factors in dyslipidemic rabbits. Gen Pharmacol 2000;34(4):263–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Bledsoe SL, Barr JC, Fitzgerald RT, Brown AT, Faas FH, Eidt JF, Moursi MM. Pravastatin and clopidogrel combined inhibit intimal hyperplasia in a rat carotid endarterectomy model. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2006;40(1):49–57. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Bledsoe SL, Brown AT, Davis JA, Chen H, Eidt JF, Moursi MM. Effect of clopidogrel on platelet aggregation and intimal hyperplasia following carotid endarterectomy in the rat. Vascular 2005;13(1):43–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Herbert JM, Tissinier A, Defreyn G, Maffrand JP. Inhibitory effect of clopidogrel on platelet adhesion and intimal proliferation after arterial injury in rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb 1993; 13(8):1171–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Zurbrugg HR, Musci M, Sanger S, Gutersohn A, Mulling C, Wellnhofer E, et al. Prevention of venous graft sclerosis with clopidogrel and aspirin combined with a mesh tubing in a dog model of arteriovenous bypass grafting. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2001;22(4):337–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Herbert JM, Dol F, Bernat A, Falotico R, Lale A, Savi P. The antiaggregating and antithrombotic activity of clopidogrel is potentiated by aspirin in several experimental models in the rabbit. Thromb Haemost 1998;80(3):512–8. [PubMed]

- 32.Karayannacos PE, Hostetler JR, Bond MG, Kakos GS, Williams RA, Kilman JW, Vasko JS. Late failure in vein grafts: mediating factors in subendothelial fibromuscular hyperplasia. Ann Surg 1978;187(2):183–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Jahnke T, Schafer FK, Bolte H, Rector L, Schafer PJ, Brossmann J, et al. Periprocedural oral administration of the leflunomide analogue FK778 inhibits neointima formation in a double-injury rat model of restenosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2005;16(7):903–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Lee BH, Nam HY, Kwon T, Kim SJ, Kwon GY, Jeon HJ, et al. Paclitaxel-coated expanded polytetrafluoroethylene haemodialysis grafts inhibit neointimal hyperplasia in porcine model of graft stenosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006;21(9):2432–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Tanous D, Brasen JH, Choy K, Wu BJ, Kathir K, Lau A, et al. Probucol inhibits in-stent thrombosis and neointimal hyperplasia by promoting re-endothelialization. Atherosclerosis 2006;189(2):342–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Kovalic JJ, Perez CA. Radiation therapy following keloidectomy: a 20-year experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1989; 17(1):77–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Friedman M, Felton L, Byers S. The antiatherogenic effect of iridium-192 upon the cholesterol-fed rabbit. J Clin Invest 1964;43:185–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Teirstein PS, Massullo V, Jani S, Popma JJ, Mintz GS, Russo RJ, et al. Catheter-based radiotherapy to inhibit restenosis after coronary stenting. N Engl J Med 1997;336(24):1697–703. [DOI] [PubMed]