Abstract

Sorption of organic pollutants by root tissue fractions, and the role of root turnover in mobilizing organic pollutants in soils, may help elucidate mechanisms of pollutant uptake by plants. The sorption of phenanthrene by bulk root tissue of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) seedlings exhibits uptake much higher than predicted based on the extractable lipids in root tissues and the octanol-water partition coefficient for phenanthrene. Surprisingly, the removal of waxes, extracted by organic solvents, only results in a slight reduction in sorption, however, the subsequent removal of suberin (polymeric lipids) by saponification greatly reduces the affinity of the residual materials (by 7-fold), suggesting that suberin serves as the major sorption medium for organic pollutants. The sorption capability of suberan (i.e., lignin and cellulose) components is completely masked by co-existing hemicellulose materials. The removal of the hemicellulose by acid hydrolysis markedly enhanced the affinity of plant root tissue fractions for phenanthrene (5–40 times), which was attributed to sorption by the aromatic condensed domains as derived from solid-state 13C-NMR data. Reversible sorption-desorption of bulk root tissue and the extractable lipids was observed, but the hydrolyzing fractions and the dewaxed-saponifiable residues demonstrated irreversible sorption.

Introduction

Phytoremediation, including direct root uptake (1–4) and stimulating rhizodegradation via root exudates and turnover materials (5–7), is an environmentally friendly technology for remediating contaminated soils (1,8,9). Plant root tissues play a critical role in implementing successful phytoremediation in contaminated soil. Uptake of nonionic organic compounds by plant roots has been shown to be a passive partitioning process between compounds inside the plant root and in the aqueous phase of the surrounding medium (2,4,10–12). Modeling uptake of nonionic organic compounds into roots is routinely based on the lipid content of the roots and the compound’s octanol-water partition coefficient (2,9–12). The plant lipid-like materials include waxes, suberin and cutin, but experimentally the total lipid is generally substituted by the extractable lipids (waxes) while the polymeric lipids (suberin/cutin) are omitted (3,9,10). Predictions of plant root uptake lower than measured values were widely observed in previous reports (3,4,13), confounding the evaluation of crop contamination at polluted sites. A recent report indicates that the polymeric lipids (i.e., inextractable ester-bound lipids) play a critical role in the sorption of nonionic organic compounds by plant cuticles (above-ground portion) (14), but this finding requires more evidence for the uptake from root tissues (below-ground portion).

The root is designed for the uptake of water and nutrients across the apoplast into the symplast. The apoplastic barriers in endodermal and hypodermal cell walls of roots contain varying amounts of the suberin, lignin, and carbohydrates (15–17). Suberin is a biopolyester primarily composed of oxygenated fatty acid derivatives (18). Suberin and lignin play a crucial role in solute transport through apoplastic barriers (16,17). However, the current knowledge about root uptake derives experimentally from the extractable lipid contents measured by organic solvent extraction rather than from removal of suberin by depolymerization. Few reports deal with the effect of the chemical composition of endodermal and hypodermal cell walls on plant root uptake and on affinity of dead root materials with organic compounds.

The purpose of the current study is to evaluate the role of suberin, suberan (lignin and cellulose), and hemicelloluse in the affinity of the bulk root tissue and its fractions for sorption of nonionic organic compounds, exemplified by the PAH phenanthrene. To this end, root tissue and 9 fractions isolated from the bulk switchgrass seedlings were prepared by chemical treatment. Their structures were analyzed for elemental composition and solid-state 13C-NMR spectra. Sorption-desorption of phenanthrene by each root tissue fraction was conducted.

Materials and Methods

Plant Root Tissue Fractions

Seedlings of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) were used as the test organism because the plant is widely used at petrochemical contaminated sites for phytoremediation. Seeds were germinated on a wet filter paper with 10% strength Hoagland solution for 5 days; the seedlings were transferred to a plastic tray containing perlite and half-strength Hoagland solution. The seedlings continued to grow at 22–24°C for three months until they reached 40–50 cm in height and developed mature roots. The plant seedlings were exposed to a 16h/8h light/dark photoperiod under fluorescent lighting with a light intensity of 120~180 µmol·m−2·s−1.

The root tissues were selected and washed with tap water to remove perlite, and they were air-dried and then oven-dried at 70–80°C overnight. The root tissue fractions were isolated by a modified version of an earlier method (19) as detailed in Figure 1. Briefly, the dry root tissues were ground and sieved (< 0.425 mm). This procedure yielded the bulk root tissue fraction (BRT). The extractable lipids (i.e., waxes) were removed from BRT by Soxhlet extraction with chloroform/methanol (1:1, v/v) at 70°C for 6 h, which yielded a dewaxed-fraction (DWF). To remove the suberin partially and completely, the DWF sample was saponified with 0.01%, 0.02%, and 1.0 % (w/v) KOH solution in methanol (i.e., methanolic KOMe) for 3 h at 70°C under refluxing conditions. After filtration-and-washing, each of the resulting individual residues yielded fractions DWPS1, DWPS2, and DWCS (partially-depolymerization for DWPS1 and DWPS2, and completely-depolymerization for DWCS, 15). The BRT, DWF and DWCS fractions were hydrolyzed (desugared) with 6 mol/L HCl solution, refluxing for 6 h at 100°C to remove the amorphous cellulose components (hemicellulose) and yielding the desugared-fraction (DSF), the dewaxed-desugared-fraction (DWSF), and the nonsaponibiable-nonhydrolyzable fraction (suberan, containing lignin and cellulose), respectively, which were separated by filtration and then washed with methanol-water mixture (1:1, v/v). The filtration-and-washing cycle was run 5-time to adjust these fractions to a neutral condition and to remove any dissolved organic matter sorbed by residues. The wax sample was prepared by evaporating the organic solvents from the Soxhlet extraction solution. The yield percentages of each root fraction were recorded. All isolated fractions were dried, ground, and sieved (< 0.425 mm) before analysis and sorption experiments.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the isolation process of switchgrass root tissue fractions. Bold type indicates the samples used in this study. Fractions DWPS1 and DWPS2 indicate partial-saponification, while DWCS indicates completely saponified. The suberan is the nonsaponifiable-desugared residue, including lignin and cellulose.

Characterization of the Root Tissue Fraction

Elemental (C, H, N) analyses were conducted using an EA 112 CHN elemental analyzer (Thermo Finnigan) for calculation of the H/C and (O+N)/C atomic. Solid-state CP/MAS 13C NMR spectra were obtained with a 300 MHz Bruker at a 13C frequency of 75.48 MHz. The instrument was operated under the following conditions: contact time, 5 ms; spinning speed, 5 kHz; 90° 1H pulse, 7 µs; acquisition delay, 5 s; line broadening, 50 Hz; and the number of scans, from 2500 to 5000. Within the 0–220 ppm chemical shift range, C atoms were assigned to paraffinic carbons (0–50 ppm), substituted aliphatic carbons (50–109 ppm), aromatic carbons (109–163 ppm), carboxyl carbons (163–190 ppm) and carbonyl carbons (190–220 ppm).

Batch Sorption and Desorption Experiment

Phenanthrene, a common environmental contaminant, was used as a model solute. Its properties include an aqueous solubility (Cs) of 1.15 mg/L (25 °C) and an octanol-water partition coefficient (Kow) of 2.8 × 104 (20). Isotherms of phenanthrene onto the root tissue fractions were obtained using a batch equilibration technique. In brief, initial concentrations ranged from 0.0005 to 1.0 mg/L. Stock phenanthrene solution was made at high concentrations in MeOH before preparing a series of phenanthrene concentrations for sorption experiments in aqueous solution which included 0.01 mol/L CaCl2 and 200mg/L NaN3, at pH=7. MeOH concentrations were always less than 0.1% of the solution volume to avoid cosolvent effects. Solid-to-solution ratios were 1.5 mg:28 mL for the desugared-fractions and 3 mg:5 mL for the remaining fractions. Each isotherm consisted of eight to ten phenanthrene concentrations; each point, including the control and calibration, was run in duplicate. The vials were completely filled with sorbate solution to minimize the headspace volume and sealed with aluminum foil-lined Teflon screw caps to avoid sorbate evaporation, and then agitated in the dark for 3 d at 25 ± 0.5 °C (preliminary tests indicated that apparent equilibrium was reached before 72 hrs). The solution was separated by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 20 min. The 0.5-mL supernatant was diluted with 0.5mL methanol. Equilibrium concentrations were measured by using a high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent 1100) with a 4.6×150 mm reverse phase XDB-C18 column and a fluorescence detector using methanol-water (V:V, 85/15) as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The excitation and emission wavelengths for phenanthrene were 244 nm and 360 nm, respectively. Because of little sorption by vials and no biodegradation, the amount sorbed was then determined by difference in aqueous concentration between the nominal concentration without sorbent and with sorbent. All sorption data were fitted to the logarithmic form of the Freundlich equation:

| (1) |

where Q is the solid-phase concentration of phenanthrene (mg/kg) and Ce is the liquid-phase equilibrium concentration of phenanthrene (mg/L). The parameters Kf (the sorption capacity coefficient [(mg/kg)/(mg/L)N]) and N (dimensionless, indicating isotherm nonlinearity) were determined by a linear regression of log-transformed data using Sigmaplot 10.0.

Phenanthrene desorption was conducted by a single decant-refill cycle technique after the completion of the sorption experiments (20). After the 0.5-mL aliquot was withdrawn, as part of the sorption procedure, the supernatant was further withdrawn to discard 75% of the whole supernatant and replaced by the fresh background solution (dilution). Following the dilution, the vials were mixed for the same equilibration time as used in the sorption experiments (20). The vials were centrifuged and an aliquot (0.5 mL) of the supernatant was taken out for HPLC analysis. Mass balance calculations were conducted to determine the amount of phenanthrene desorbed. The losses of phenanthrene during desorption were negligible.

Results and Discussion

Composition of Root Fractions of Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) Seedlings

Mass fractions and elemental composition of switchgrass root fractions are presented in Table 1. Root tissue compositions include waxes (the extractable lipids), suberin (the polymeric lipids), hemicellulose, and suberan (including cellulose and lignin). The amount of the extractable lipids was 8.24 wt%. The fractions subsequently removed by saponification are the polymeric lipids (suberin) because the extractable lipids have already been removed in the previous extraction step. The removal percentages refer to the polymeric lipids only were 4.29 wt%, 4.81 wt% and 11.1 wt% of the bulk root, respectively, which was saponified in 0.01%, 0.02% and 1.0% KOH methanol solution. The amount of suberin in roots (11.1%) compared with the extractable lipids (8.24%) indicates that these fractions should be added to gain a more accurate measurement and understanding of the total lipid contents of root tissue (14). The (N+O)/C ratio of the extractable lipids of root was ~0.48, showing more polarity than the cuticular waxes of above-ground fruits (0.1~0.3, 14). Considering the varying suberin contents in fractions BRT, DWF, DWPS1, DWPS2 and DWCS facilitated an investigation of the role of suberin in the uptake of phenanthrene by roots. The weight loss by acid-hydrolysis represents hemicellulose, which was 46.9%. The final residue (nonsaponifiable-nonhydrolyzable fraction) corresponded to 33.8% of the total bulk root mass, which contained lignin and inextractable cellulose fractions, termed suberan. After acid-hydrolysis (of fractions DWCS→suberan, DWF→DWSF, BRT→DSF), the carbon contents of the residuals increased, while the oxygen content decreased, suggesting a relatively high aromatic content (H/C≈1.1) and low polarity [(N+O)/C=0.41~0.55]. The three pairs (DWCS→suberan, DWF→DWSF, BRT→DSF) are employed to illustrate the role of hemicellulose and suberan in sorption variations of freshly decaying materials as root tissue turnover.

TABLE 1.

Relative Mass Fractions of the Different Root Fractions in Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), and Their Elemental Analysis and Atomic Ratios.

| Fractiona) | Yieldb), %wt |

Component distribution % mass |

Elemental composition % mass |

H/C | (N+O)/C | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wax | Suberin | Hemicellulose | Suberanc) | C | H | N | Od) | ||||

| BRT | 100 | 8.2 | 11.1 | 46.9 | 33.8 | 46.8 | 6.24 | 0.81 | 46.2 | 1.59 | 0.76 |

| DWF | 91.8 | 0 | 12.1 | 51.1 | 36.8 | 45.9 | 6.07 | 0.74 | 47.3 | 1.58 | 0.79 |

| DWPS1 | 87.5 | 0 | 7.8 | 53.6 | 38.6 | 45.3 | 6.06 | 0.66 | 48.0 | 1.59 | 0.81 |

| DWPS2 | 87.0 | 0 | 7.2 | 53.9 | 38.9 | 45.5 | 6.15 | 0.65 | 47.6 | 1.61 | 0.80 |

| DWCS | 80.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 58.1 | 41.9 | 42.8 | 5.95 | 0.65 | 50.6 | 1.66 | 0.90 |

| Suberan | 33.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 100 | 54.7 | 5.22 | 0.42 | 39.7 | 1.14 | 0.55 |

| DWSF | 44.9 | 0 | 24.7 | 0 | 75.3 | 57.0 | 5.42 | 0.39 | 37.2 | 1.13 | 0.50 |

| DSF | 53.1 | 15.4 | 20.9 | 0 | 63.7 | 61.0 | 5.52 | 0.53 | 33.0 | 1.08 | 0.41 |

| Wax | 8.2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 56.0 | 8.44 | 0.74 | 34.8 | 1.80 | 0.48 |

The meaning of each root fraction is indicated in Figure 1.

The yields were obtained in duplicate for each fraction and presented as the average. The yields of each root tissue fraction were calculated based on the percentage content of individual bulk root tissue (BRT). The calculated distribution of hemicellulose was the average from the three pairs used here (BRT-DSF, DWF-DWSF, and DWCS-suberan). The water content of bulk root tissue of Switchgrass seedlings was 92%.

Suberan includes lignin and cellulose.

Oxygen content was calculated by the mass difference.

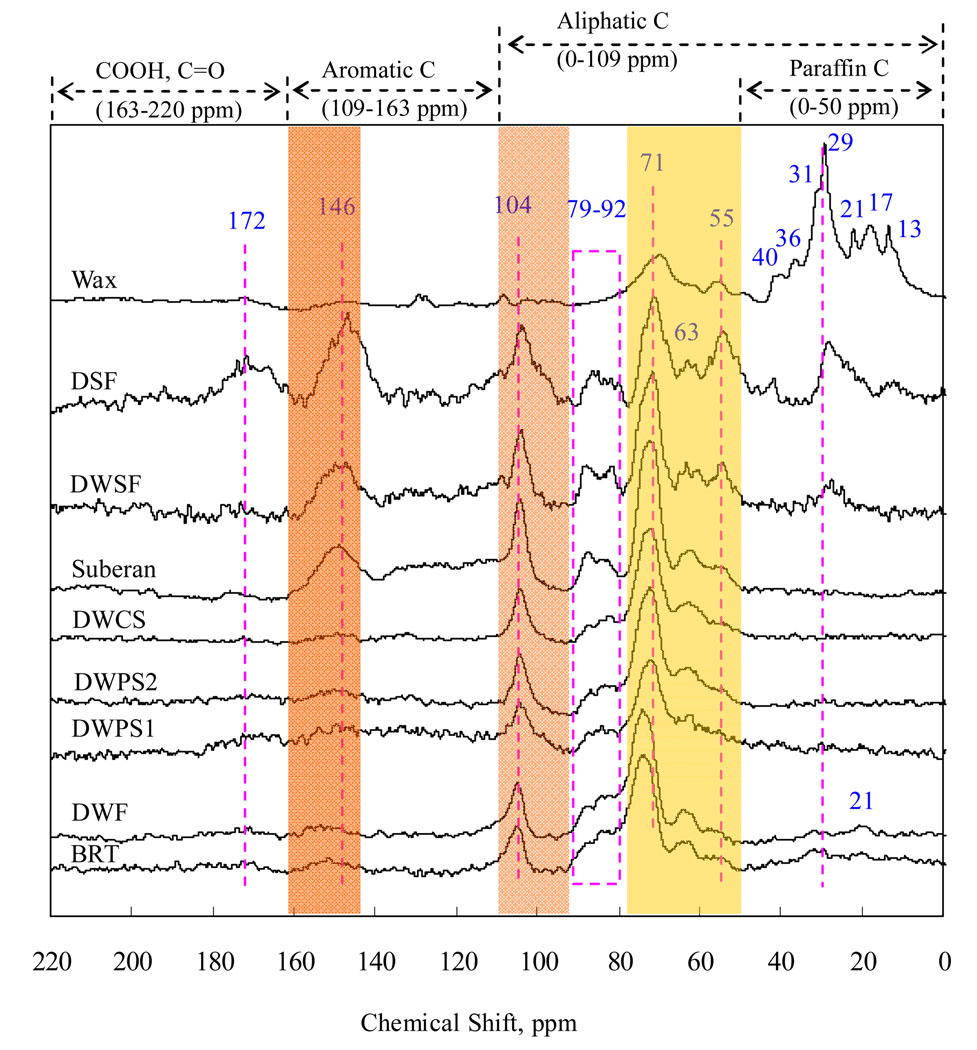

Structures and conformations of root tissue fractions were characterized by solid-state 13C-NMR (Figure 2 and Table 2). From Table 2, the BRT sample is dominated by the alkyl-C (0–50 ppm, 16.5%) and O-alkyl-C (50–109 ppm, 74.5%). The former region is composed of carbons in (CH2)n and terminal CH3 groups of plant lipids, such as waxes and suberin. The percentage of the alkyl-C decreases sequentially from 16.48% (BRT) to 0.25% (DWCS) after dewaxed- and then desuberined-treatment. The 55 ppm peak was from methoxy groups (OCH3) on aromatic rings, which are probably the most characteristic functional group for lignin (21). After desugared-treatment, the carbon distribution in 61–96 ppm region for the residues was reduced significantly, i.e., 63.53% (BRT)→26.81% (DSF), 59.15% (DWF)→44.02% (DWSF), and 65.12% (DWCS)→39.61% (suberan), suggesting that a large portion of the carbohydrates consisted of extractable amorphous components of plant cellulose fibers. Concurrently, the aromatic-C (109–163 ppm) contents increased from 7.72% (BRT) to 21.08% (DSF), 14.23% (DWF)→25.06% (DWSF), and 3.37% (DWCS)→33.08% (suberan). Similar evidence for wood was presented by Huang et al. (21). From Figure 2, with the increasing signals of aromatic C (109–163 ppm) in desugared samples, the peak intensity at 55 ppm also increased. The increasing intensities at 146 ppm indicated the cleavage of aryl ether in lignin by the formation of the phenolic hydroxyl group (21). Among the desugared-residues, the suberan exhibited the highest percentage of non-substituted aromatic-C (109–145 ppm, 22.90%). The respective signals located at 83 and 88 ppm are from C-4 in amorphous and crystalline celluloses (21). These signals with a distribution of 86~92 ppm and 79~85 ppm, respectively, correspond to internal cellulose crystallites (ordered) and external amorphous cellulose (disordered) (22). The spectral regions of 74~77 ppm and 70~74 ppm largely originate from ring carbons within disordered cellulose and ordered cellulose, respectively (22). After acid-hydrolysis, the amorphous domains were removed and the condensed domains remained. Correspondingly, the calculated crystallinity index increased, i.e., 0.292 (BRT)→0.418 (DSF), 0.332 (DWF)→0.427 (DWSF), and 0.255 (DWCS) →0.447 (suberan) (Table 2). These observations indicate that the aromatic condensed domains of lignin and crystalline cellulose are exposed after removal of amorphous cellulose by hydrolysis. However, apart from dissolving the sugars, the additional alteration of the residual materials during the chemical processing is still unclear.

Figure 2.

Solid-state 13C NMR spectra of the bulk root tissue (BRT) and its fractions. Note that the suberan, DWSF, and DSF are the desugared residues of DWCS, DWF, and BRT, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Integrated Results of Solid-State 13C NMR Spectra and Crystallinity Index

| Sample a | Distribution of C chemical shift, ppm (%)b | Aliphatic C, % |

Aromatic C, % |

Polar C, % |

Crystal index c |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–50 | 50–61 | 61–96 | 96–109 | 109–145 | 145–163 | 163–190 | 190–220 | |||||

| BRT | 16.5 | 3.46 | 63.5 | 7.48 | 6.53 | 1.19 | 1.34 | 0.00 | 90.9 | 7.72 | 77.0 | 0.292 |

| DWF | 5.21 | 2.95 | 59.2 | 11.1 | 7.79 | 6.44 | 5.83 | 1.53 | 78.4 | 14.2 | 87.0 | 0.332 |

| DWPS1 | 4.83 | 6.16 | 59.5 | 10.6 | 3.22 | 9.75 | 5.91 | 0.00 | 81.1 | 13.0 | 91.9 | 0.235 |

| DWPS2 | 1.36 | 5.54 | 60.5 | 10.9 | 3.05 | 9.25 | 7.17 | 2.18 | 78.4 | 12.3 | 95.6 | 0.127 |

| DWCS | 0.25 | 10.43 | 65.1 | 12.6 | 2.16 | 1.21 | 0.90 | 7.28 | 88.4 | 3.37 | 97.6 | 0.255 |

| Suberan | 1.18 | 6.08 | 39.6 | 12.2 | 22.9 | 10.2 | 0.97 | 6.83 | 59.1 | 33.1 | 75.9 | 0.447 |

| DWSF | 3.29 | 9.58 | 44.0 | 12.1 | 15.72 | 9.34 | 1.23 | 4.71 | 69.0 | 25.1 | 81.0 | 0.427 |

| DSF | 11.69 | 15.6 | 26.8 | 16.1 | 5.98 | 15.1 | 7.11 | 1.57 | 70.3 | 21.1 | 82.4 | 0.418 |

| Wax | 66.59 | 4.45 | 15.8 | 0.13 | 1.67 | 0.78 | 4.02 | 6.54 | 87.0 | 2.45 | 31.8 | -- |

The meaning of each root fraction is indicated in Figure 1.

Aliphatic C: total aliphatic carbon region (0–109 ppm). Aromatic C: total aromatic carbon region (109–163 ppm). Polar C: total polar C region (50–109 ppm and 145–220 ppm).

Crystallinity index=(86–92ppm)/[(86–92ppm)+(79–86ppm)]=Crystalline cellulose/(amorphous cellulose+crystalline cellulose).

Phenanthrene Sorption by Root Tissue Fractions

Sorption of phenanthrene to root tissue fractions (9 samples) of switchgrass seedlings were compared to illustrate the role of chemical composition (i.e., waxes, suberin, cellulose, and lignin). Selected isotherms are presented in Figure 3, which fit well to the Freundlich equation, and the regression parameters are listed in Table 3. A precise comparison cannot be made between Kf values because of nonlinearity. Therefore, the sorption coefficients (Kd and Koc) were also calculated and presented in Table 3. The sorption isotherm for wax was linear (N=1.02±0.02), but for BRT, DWF, DWPS1, DWPS2 and DWCS samples the isotherms were weakly nonlinear (N=0.93~0.95), and essentially nonlinear for samples suberan, DWSF, DSF (desugared-residues, N=0.80~0.91). The nonlinearity of the desugared-samples may be a result of the contribution of the exposed aromatic condensed domains, which favor nonlinear specific-interaction (19,21,23). The phenanthrene sorption coefficient into bulk root tissue (BRT, Koc=8,500) was somewhat less than the octanol-water partition coefficient (Kow=28,000), and it was considerably less than that of the bulk fruit above-ground cuticle (Koc=103,000, 19), medium polarity [(N+O)/C=0.31] in comparison with octanol (0.125) and BRT (0.756). However, the Koc value for the bulk root tissue was higher than aspen wood fibers (~4500) with the identical polarity [(N+O)/C=0.754] (21). The lack of a direct relationship between the polarity index and Koc (or Kow) supports the previous findings that both polarity and accessibility regulates the sorption of aromatic organic contaminants by plant cuticular materials (19).

Figure 3.

Phenanthrene sorption-desorption by bulk root tissue fractions of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum). (A) Sorption of the bulk root tissue (BRT), dewaxed fraction (DWF), partially-saponifiable fraction (DWPS1), completely-saponifiable fraction (DWCS), and the extractable waxes (Wax). The dashed line in Figure 3(A) is the prediction for BRT sample based on the extractable lipid sorption model (Q=flipidKowCe). (B) Sorption of BRT, DWF and DWCS, and their desugared fractions (DSF, DWSF, and suberan). (C) Sorption-desorption data of BRT and DWCS. The dashed line in Figure 3(C) is used just for easily reading the desorption point.

TABLE 3.

Phenanthrene Sorption Coefficients and Freundlich Model Parameters with the Root Tissue Fractions of Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) Seedlings.

| Sorbent a | N | logKfb | Freundlich r2 | Kd (mL/g) c | Koc(mL/g) d | Linear r2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRT | 0.951 ± 0.009 | 3.594 ± 0.031 | 0.999 | 3974 ± 59 | 8496 | 0.996 |

| DWF | 0.928 ± 0.006 | 3.541 ± 0.012 | 1.000 | 3503 ± 44 | 7631 | 0.997 |

| DWPS1 | 0.938 ± 0.008 | 3.508 ± 0.017 | 0.999 | 3006 ± 38 | 6636 | 0.986 |

| DWPS2 | 0.937 ± 0.004 | 3.479 ± 0.008 | 1.000 | 3072 ± 39 | 6749 | 0.997 |

| DWCS | 0.936 ± 0.008 | 2.736 ± 0.015 | 0.999 | 527.7 ± 70 | 1232 | 0.997 |

| Suberan | 0.799 ± 0.014 | 4.355 ± 0.036 | 0.995 | 20810 ± 780 | 38068 | 0.975 |

| DWSF | 0.859 ± 0.008 | 4.311 ± 0.020 | 0.999 | 18240 ± 530 | 32003 | 0.985 |

| DSF | 0.914 ± 0.020 | 4.412 ± 0.049 | 0.992 | 20100 ± 800 | 32970 | 0.972 |

| Wax | 1.020 ± 0.020 | 3.622 ± 0.042 | 0.995 | 4075 ± 50 | 7279 | 0.997 |

The meaning of each root fraction is indicated in Figure 1.

Kf is the Freundlich sorption coefficient [(mg/kg)/(mg/L)N].

Kd is the sorption coefficient calculated from the slope of the linear isotherms due to (practically) linear sorption.

Koc = Kd / foc; where foc is the organic carbon content of sorbent.

The Role of the Extractable Lipids and Polymeric Lipids in Root Uptake

After removing the extractable lipids from BRT, the Koc of DWF (7,600) demonstrated only an insignificant reduction. Based on the assumption of the predominant role of plant lipids (experimentally substituted by the extractable lipids), the predicted Kd for BRT (upon extracting lipid contents) was 2,300 mL/g (Kd = Kow×lipid% =28000×8.24%). The predicted sorption of BRT, shown as the dashed line in Figure 3(A), was notably lower than the measured value. Li et al. (3) also observed a similar result for lindane and hexachlorobenzene sorbed to bulk root tissues, and attributed it to underestimation of the plant lipid contents and to the fact that octanol is less effective as a partition medium than plant lipids. Recently, Zhang and Zhu (13) argued that the phenomenon was attributed to the underestimation of the contribution of the carbohydrates besides the lipid (the extractable lipid actually), because the former dominated the weight fractions of root tissue and exhibited relative high sorption capability (>10-fold) over general presumption (2). In the current study, for the isolated-waxes of bulk root tissue with high polarity (0.48), the phenanthrene Koc (7300) was less than the Kow. Even for fruit cuticular waxes with extremely low polarity (~0.10), the Koc of phenanthrene (26000~32000) didn’t exceed the Kow (20). These results suggest that the extractable lipid may be not the dominant sorptive medium for neutral, hydrophobic chemicals like phenanthrene in bulk root tissue.

Recently, the polymeric lipids, in addition to the extractable lipids, were suggested to be included to gain more accurate determination of plant lipid content and then to estimate Koc values precisely (14). The polymeric lipids can’t be extracted by organic solvents but are dissolved by depolymerization in methanolic KOMe (14). Interestingly, after removal of polymeric lipids (i.e., suberin) from DWF, the sorption capability (Kd) was reduced gradually, from 3,500 mL/g (DWF) to the minimal value (530 mL/g) for DWCS without polymeric lipids. Thus, the sorption coefficient of suberin composition can be estimated through a mass balance, i.e., Kd,DWF × fDWF = Kd,DWCS × fDWCS + Kd,suberin × fsuberin, where Kd,DWF, Kd,DWCS and Kd,suberin are sorption coefficients of DWF, DWCS and root suberin, respectively; and fDWF, fDWCS and fsuberin are their corresponding contents in the bulk root tissue (Table 1). The calculated Kd,suberin value for switchgrass root tissue is 25,100 mL/g, which is much higher than the determined-Kd,wax value (4,075 mL/g). The result in vitro suggests that the suberin functions as the major storage medium in root tissue for neutral, hydrophobic organic pollutants, rather than the extractable lipid (3,4) or the whole carbohydrates (13). However, more studies in vivo are needed to prove this suggestion. Recently, Wild et al. (24) used two-photon excitation microscopy for the first time to directly visualize and track the uptake and movement of PAHs in living roots. They found that the solutes are mainly located at the outer surface of the epidermal cells but once within the cortex cells they are concentrated and “streamed” longitudinally toward the shoot by slow lateral movement. The unique distribution and movement of PAHs within root in vivo are consistent with the structural distribution of suberin in root cell walls, in which suberin separates the vascular tissue of the central cylinder from the root cortex in endodermal cell walls, while it builds the interface (Casparian strip) to the soil environment in rhizodermal and hypodermal cell walls (16,17). Therefore, more studies are needed to elucidate the role of suberin in root uptake and translocation of organic pollutants in phytoremediation practices.

For polymeric lipids (cutin) in plant cuticle (ripe tissue), the sorption coefficients were 72,400 mL/g for tomato cuticle, 73,700 mL/g for potato periderm, 90,200 mL/g for apple cuticle, and 99,600 mL/g for grape cuticle (25), which are significantly higher than the Kd,suberin value of roots (freshly) in this study. The distinct sorption capability may be attributed to a different development stages of polymeric lipids in the ripe fruit cuticles and the fresh switchgrass seedling root.

The Role of Cellulose and Lignin in Sorption of Root Tissue Fractions

After removal of the amorphous cellulose (hemicellulose) by acid hydrolysis, the sorption capability of the root tissue fractions were significantly enhanced [see Figure 3(B)], i.e., Kd (mL/g) = 527.7 (DWCS)→20,810 (suberan), 3503 (DWF)→18,240 (DWSF), 3974 (BRT)→20,100 (DSF). Consumption of the hemicellulose extremely enhanced the affinity of the plant root tissue fractions with phenanthrene (5–40 times), which is attributed to the exposed condensed domains and aromatic cores (suberan) derived from solid-state 13C-NMR data. The aromatic condensed domains favor hydrophobic interaction, π-π electron donor-acceptor (π-π EDA) interactions, and polarizable interactions with organic solutes, especially those with high polarizability such as phenanthrene (26,27). Similar observations were reported regarding enhanced sorption of phenanthrene (2–14 times higher) to hydrolyzed wood (22).

Interestingly, the DWCS sample contains 41.90% of suberan (i.e., lignin and cellulose), but the Kd value exhibited a minimum (527.7 mL/g), suggesting that the availability of suberan components to sorb phenanthrene is completely masked/inhibited by the co-existing amorphous cellulose materials. Several studies have indicated that cellulose and hemicelluloses, which mainly consist of polar aliphatic moieties, exhibit little measurable uptake of aromatic hydrocarbons, while lignin, containing primarily aromatic moieties, showed great affinity for the solutes (23). For DWCS, lignin-rich moieties may be dispersed among carbohydrates rich in polyhydroxyl and carboxylic groups. These functional groups can produce strong hydrogen bonds within the root tissue and also with water, possibly preventing PAH molecules from accessing the aromatic cores as a result of the surrounding polar components (19,21). In this situation, the sorption capability of root tissue fractions would be controlled by the total lipid contents, including the extractable and polymeric components. The order of magnitude of Kd was consistent with the total lipid contents, i.e., BRT (Kd = 3974, lipid%=19.3) > DWF (3503, 12.1%) > DWPS1 (3006, 7.8%) ≈ DWPS2 (3072, 7.2%) » DWCS (527.7, 0%). The sequence of Kd values were in reverse order of suberan content, i.e., BRT (suberan% = 33.8%) > DWF (36.8%) > DWPS1 (38.6%) ≈ DWPS2 (38.9%) » DWCS (41.9%). The current observations, i.e., that the presence of hemicellulose inhibits sorption and that suberin functions as storage domains for phenanthrene, explains the previous findings in vivo that phenanthrene only migrated as far as the cortex cells of root tissue and did not reach the vascular transport system (the phloem/xylem)(24).

However, without the presence of the amorphous cellulose, sorption of the root tissue fractions (e.g., suberan, DWSF and DSF) would be mainly dominated by lignin rather than lipids. Thus, PAH molecules might more easily gain access to the aromatic cores of the desugared root fractions, which increased the Koc in comparison with their precursor. The Koc for desugared-fraction samples were comparable to that of pure lignin (Koc=28,000~23,000, 24). Similarly, Wang and Xing (23) observed that lignin-coating biopolymers resulted in an increased Koc for phenanthrene relative to chitin and cellulose and also increased isotherm nonlinearity, due to the newly formed condensed domains which were available for the sorbate. Lignin is recalcitrant and hydrophobic, while most cellulose is more polar and readily degraded. Celluloses exhibit little nonpolar organic compound sorption. Thus, wood-water partition coefficients have been hypothesized to be controlled by the wood lignin content (28,29). Wood-water partition coefficients for nonionic sorbates (10 < Kow < 104) can be predicted as the product of the wood’s fractional lignin content (28); However, the availability of lignin adjoining fibers within the wood particle to retain organic pollutants should be evaluated, especially for decaying plant tissues with varying chemical compositions.

Desorption of Phenanthrene with Root Tissue Fractions

Selected desorption data are presented in Figure 3C. Differences in the degree of hysteresis were observed between root tissue fractions. For bulk root tissue (BRT) and isolated-wax samples (wax), there was no apparent hysteresis at all. The desorption behavior in vitro suggests that phenanthrene retained by bulk root tissues may be reversibly released into soil (rhizosphere) or transferred into the internal environment of the root tissue with the transpiration water, but data in vivo are still needed. Wild et al. (24) reported that after entering the cell walls of the cortex cells of root in vivo, phenanthrene started to exhibit the streaming phenomenon with the transpiration stream, which is consistent with desorption behavior and insignificant hysteresis for bulk root tissue. Conversely, for desugared-fractions, a pronounced hysteresis occurred at all concentrations of phenanthrene, reflecting that desorption of phenanthrene from these samples was comparatively difficult and implying that sorption-desorption hysteresis increased after degradation of the dead root tissue due to removal of hemicellulose and cellulose. The possible reasons for the difference in hysteresis between lipid and suberan (lignin and cellulose) composition may be as follows: hydrolysis removes most hemicellulose and part of the cellulose, yielding a much more condensed matrix in which irreversible adsorption dominates. Huang et al. (21) believed that aromatic moieties play an important role in hysteresis, that is, the higher the aromaticity, the more apparent the hysteresis. Van Beinum et al. suggested that the observed difference between the sorption and desorption data should be attributed to the nonattainment of equilibrium due to a slow diffusion into and out of the lignin particles (30). The apparent hysteresis for the non-linear fractions may be an indication that the kinetics of desorption were slower than the kinetics of sorption. Sorption-desorption hysteresis of the waxes is controlled by the conformation and polarity of the waxes. In a previous report, sorption hysteresis of fruit cuticular lipids with phenanthrene at high concentrations was observed and attributed to a transition of solid amorphous (32 ppm) to mobile amorphous domains (29 ppm) in the reconstituted-waxes upon loading phenanthrene, as derived from solid-state 13C NMR data (20). In comparison, the extractable lipids of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) roots presented a more mobile amorphous state based on solid-state 13C NMR data (see Figure 1), i.e., the polymethylene peak located in 29 ppm over 32 ppm, and resulted in insignificant hysteresis. Interestingly, the DWCS sample with minimal sorption exhibited the largest hysteresis among the tested root tissue fractions, which may be due to aromatic cores dispersed among carbohydrates functioning as effective binding sites. Clearly, the effect of chemical compositions on sorption/desorption behavior of root tissues will provide a fundamental guide to conceptualize plant root uptake and also contribute to understanding solute transport through an apoplastic barrier (i.e., Casparian band) in cell walls.

Acknowledgments

We thank SERDP (Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program), Project Number ER-1499, and IIHR Hydroscience and Engineering at the University of Iowa for support of this research; and Collin Just for laboratory direction. A Visiting Scholar award to the first author from Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, is gratefully acknowledged. Chen thanks in part support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 40671168). This work was partially supported by the Superfund Basic Research Program (SBRP), Grant Number P42ES13661, and is a contribution from the W. M. Keck Phytotechnology Laboratory at the University of Iowa.

Literature Cited

- 1.Dietz AC, Schnoor JL. Advances in phytoremediation. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001;109 suppl 1:163–168. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109s1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiou CT, Sheng G, Manes M. A partition-limited model for the plant uptake of organic contaminants from soil and water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001;35:1437–1444. doi: 10.1021/es0017561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li H, Sheng GY, Chiou CT, Xu OY. Relation of organic contaminant equilibrium sorption and kinetic uptake in plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:4864–4870. doi: 10.1021/es050424z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su YH, Zhu YG. Transport mechanisms for the uptake of organic compounds by rice (Oryza sativa) roots. Environ. Pollut. 2007;148:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leigh MB, Fletcher JS, Fu X, Schmitz FJ. Root turnover: an important source of microbial substrates in rhizosphere remediation of recalcitrant contaminants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002;36:1579–1583. doi: 10.1021/es015702i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamath R, Schnoor JL, Alvarez PJJ. A model for the effect of rhizodeposition on the fate of phenanthrene in aged contaminated soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:9669–9675. doi: 10.1021/es0506861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mueller KE, Shann JR. Effects of tree root-derived substrates and inorganic nutrients on pyrene mineralization in rhizosphere and bulk soil. J. Environ. Qual. 2007;36:120–127. doi: 10.2134/jeq2006.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnabel WE, Dietz AC, Burken JG, Schnoor JL, Alvarez PJ. Uptake and transformation of trichloroethylene by edible garden plants. Water Res. 1997;31:816–824. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins C, Fryer M, Grosso A. Plant uptake of non-ionic organic chemicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006;40:45–52. doi: 10.1021/es0508166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briggs GG, Bromilow RH, Evans AA. Relationships between lipophilicity and root uptake and translocation of non-ionized chemicals by barley. Pestic. Sci. 1982;13:495–504. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trapp S. Modeling uptake into roots and subsequent translocation of neutral and ionisable organic compounds. Pest. Manage. Sci. 2000;56:767–778. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trapp S. Fruit Tree model for uptake of organic compounds from soil and air. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2007;18:367–387. doi: 10.1080/10629360701303693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang M, Zhu L. Sorption of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to carbohydrates and lipids of ryegrass root and implications for sorption prediction model. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43:2740–2745. doi: 10.1021/es802808q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen B, Li Y, Guo Y, Zhu L, Schnoor JL. Role of the extractable lipids and polymeric lipids in sorption of organic contaminants onto plant cuticles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:1517–1523. doi: 10.1021/es7023725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopes MH, Gil AM, Silvestre AJD, Neto CP. Composition of suberin extracted upon gradual alkaline methanolysis of Quercus suber L. cork. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000;48:383–391. doi: 10.1021/jf9909398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schreiber L, Hartmann K, Skrabs M, Zeier J. Apoplasic barriers in roots: chemical composition of endodermal and hypodermal cell walls. J. Environ. Bot. 1999;50:1267–1280. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franke R, Schreiber L. Suberin-A biopolyester forming apoplastic plant interfaces. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007;10:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernards MA. Demystifying suberin. Can. J. Bot. 2002;80:227–240. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen B, Johnson EJ, Chefetz B, Zhu L, Xing B. Sorption of polar and nonpolar aromatic organic contaminants by plant cuticular materials: the role of polarity and accessibility. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:6138–6146. doi: 10.1021/es050622q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen B, Xing B. Sorption and conformational characteristics of reconstituted plant cuticular waxes on montmorillonite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:8315–8323. doi: 10.1021/es050840j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang L, Boving TB, Xing B. Sorption of PAHs by aspen wood fibers as affected by chemical alterations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006;40:3279–3284. doi: 10.1021/es0524651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wormald P, Wickholm K, Larsson PT, Iversen T. Conversions between ordered and disordered cellulose. Effects of mechanical treatment followed by cyclic wetting and drying. Cellulose. 1996;3:141–152. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Xing B. Importance of structural makeup of biopolymers for organic contaminant sorption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41:3559–3565. doi: 10.1021/es062589t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wild E, Dent J, Thomas GG, Jones KC. Direct observation of organic contaminant uptake, storage, and metabolism within plant roots. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:3695–3702. doi: 10.1021/es048136a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Chen B. Phenanthrene sorption by fruit cuticles and potato periderm with different compositional characteristics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:637–644. doi: 10.1021/jf802719h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu DQ, Hyun SH, Pignatello JJ, Lee LS. Evidence for pi-pi electron donor-acceptor interactions between pi-donor aromatic compound sand pi-acceptor sites in soil organic matter through pH effects on sorption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004;38:4361–4368. doi: 10.1021/es035379e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen TH, Goss KU, Ball WP. Polyparameter linear free energy relationships for estimating the equilibrium partition of organic compounds between water and the natural organic matter in soils and sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:913–924. doi: 10.1021/es048839s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackay AA, Gschwend PM. Sorption of monoaromatic hydrocarbons to wood. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000;34:839–845. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trapp S, Miglioranza KSB, Mosbaek H. Sorption of lipophilic organic compounds to wood and implications for their environmental fate. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001;35:1561–1566. doi: 10.1021/es000204f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Beinum W, Beulke S, Brown CD. Pesticide sorption and desorption by lignin described by an intraparticle diffusion model. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006;40:494–500. doi: 10.1021/es051940s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]