Abstract

The present study investigated patterns in the development of conduct problems (CP), depressive symptoms, and their co-occurrence, and relations to adjustment problems, over the transition from late childhood to early adolescence. Rates of depressive symptoms and CP during this developmental period vary by gender, yet, few studies involving non-clinical samples have examined co-occurring problems and adjustment outcomes across boys and girls. This study investigates the manifestation and change in CP and depressive symptom patterns in a large, multisite, gender- and ethnically-diverse sample of 431 youth from 5th to 7th grade. Indicators of CP, depressive symptoms, their co-occurrence, and adjustment outcomes were created from multiple reporters and measures. Hypotheses regarding gender differences were tested utilizing both categorical (i.e., elevated symptom groups) and continuous analyses (i.e., regressions predicting symptomatology and adjustment outcomes). Results were partially supportive of the dual failure model (Capaldi, 1991, 1992), with youth with co-occurring problems in 5th grade demonstrating significantly lower academic adjustment and social competence two years later. Both depressive symptoms and CP were risk factors for multiple negative adjustment outcomes. Co-occurring symptomatology and CP demonstrated more stability and was associated with more severe adjustment problems than depressive symptoms over time. Categorical analyses suggested that, in terms of adjustment problems, youth with co-occurring symptomatology were generally no worse off than those with CP-alone, and those with depressive symptoms-alone were similar over time to those showing no symptomatology at all. Few gender differences were noted in the relations among CP, depressive symptoms, and adjustment over time.

Keywords: Depression, Conduct problems, Comorbidity, Adolescence, Adjustment, Gender differences

Conduct problems (CP) and depressive symptoms are two of the most prevalent forms of youth psychopathology, with far-reaching effects on personal and social development (Hinshaw & Lee, 2003). CP and depression are each associated with negative outcomes in adolescence, including academic and social skills deficits and substance use (Birmaher et al., 1996). Co-occurrence of these conditions occurs at higher rates than would be expected by chance and is associated with a more severe and wide-ranging presentation of psychopathology (Angold, Costello, & Erkanli, 1999; Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 1995). There is consistent evidence that developmental patterns of CP and depression vary by gender over this period (Angold & Costello, 1993; Miller-Johnson, Lochman, Coie, Terry, & Hyman, 1998), Yet few studies involving nonclinical samples have examined continuity and change in co-occurring problems across gender. In this study dimensional and categorical approaches were used to predict patterns of elevated CP, depressive symptoms, and their co-occcurrence from 5th to 7th grade. We also examined the relative strength of these symptoms in predicting key adjustment outcomes in 7th grade using a community sample that was gender-balanced and ethnically diverse. We sought to answer the following questions: How do CP and depressive symptoms, and their co-occurrence, manifest and change from late childhood to early adolescence? What happens for youth who are experiencing elevated problems in these areas in childhood as they transition into adolescence? Do patterns of CP and depressive symptoms predict adjustment problems in early adolescence and are these relations different for boys versus girls?

Transition to adolescence and behavior problem rates

The average rates of CP, depressive symptoms, and their co-occurrence generally increase from childhood to adolescence (Anderson, Williams, McGee, & Silva, 1987), For example, Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder diagnoses grow from approximately 5% in late childhood up to 19% in mid-adolescence, and depressive diagnoses rates increase from approximately 3 to 9% (Bird et al., 1988; Cohen et al., 1993). This developmental period is marked by a number of changes in youths' lives, including puberty for girls and onset of puberty for boys, and transition from primary to secondary school settings, with accompanying disturbances in peer groups, reliance on peer status and opinion, and self-esteem issues. This period of rapid physical, emotional, and behavioral change can result in increased interpersonal and internal stress, and the emergence of mood and behavior problems (Roesner & Eccles, 1998). The concomitant increase in serious adjustment problems during this period, such as suicidal behavior, antisocial peer involvement and substance use, highlights the importance of studying these developmental processes (Eccles, 1999; Fergusson, Lynskey, & Horwood, 1996). It is critical to understand how youth who are demonstrating early CP and depressive symptoms move through this time of heightened stress and change, and how these early symptom patterns result in particular adjustment problems, in order to develop more targeted, effective prevention and intervention strategies.

Gender variation in CP, depression, and co-occurring problems

Although overall rates of CP and depressive symptoms increase over adolescence, the early developmental course and severity of each type of problem appears to differ for boys and girls in important ways. In childhood, the gender ratio of CP is approximately four to one for boys versus girls, but by adolescence, decreases to approximately two to one (Frick, 1998; Zocolillo, 1993). There are no appreciable gender differences in rates of depression in childhood. Yet, beginning in pre-adolescent years, rates of girls' diagnosed depression and depressive symptoms on dimensionally-based measures have been shown to be twice as high as for adolescent boys (Ge, Conger, & Elder, 2001; Kandel & Davies, 1982). Co-occurrence of CP and depression has been documented in youth, with overall prevalence rates for community samples at about 6 to 7% (Bird, Gould, & Staghezza, 1993; Kashani et al., 1987). Prevalence rates of comorbid diagnoses appear to increase from childhood to adolescence and some studies report higher rates for boys than girls (Costello et al., 1996; Esser, Schmidt, & Woerner, 1990). There appears to be a complex relationship between co-occurrence and gender. Girls are more likely to become depressed than boys in adolescence. When girls develop CP, they are more likely to also develop co-occurring conditions such as depression. Boys are more likely to have CP in childhood and adolescence. However, if boys do become depressed, they are more likely to have co-occurring conditions, such as CP (Rohde, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1991). Loeber and Keenan (1994) have described this as a gender paradox. Understanding how these patterns unfold by gender is important for developmentally appropriate and effective assessment of risk. Furthermore, when adolescent youth of either gender have a co-occurring condition, the symptoms of each tend to be more severe and chronic, with poorer outcomes (Birmaher et al., 1996; Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999).

Researchers have hypothesized different causal relationships between depression and CP. Experiencing early depression may impede social development, creating dyadic conflict and amplifying risk for negative reactions from others that lead to later CP (Kovacs, Paulauskas, Gatsonis, & Richards, 1988; Rudolph, Hammen, & Burge, 1994), In contrast, CP may emerge first and the disruption in interpersonal functioning may promote depressive symptomatology in adolescence (Rudolph et al., 1994). Capaldi (1991,1992) demonstrated support for the latter hypothesis, in what she terms a dual-failure model. She hypothesizes that the aversive behavior engaged in by the child with early CP leads to increased conflict with parents and peers and greater peer rejection (failure in social domain) and interference with academic skills (failure in academic domain), which in turn leads to depressed mood when the child repeatedly “fails” in his or her environment. The dual failure pathway was supported in longitudinal analyses involving high-risk boys (Capaldi, 1992; Patterson & Capaldi, 1990; Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999). CP predicted the development of depression, but not vice-versa. Other clinical studies provide evidence supporting the emergence of CP prior to depression in early adolescent samples (Biederman, Faraone, Mick, & Lelon, 1995; Sack, Beiser, Phillips, & Baker-Brown, 1993). However, it is important to note that in each study, bidirectional relations existed. It seems likely that a transactional process by which the child's behavior interacts with the environment over time to create new risk factors or problem behaviors (“reciprocal causality,” Fergusson et al., 1996), is another path to co-occurring CP and depression. The relationship may also be asymmetrical, with early CP having a greater effect on emergence of depression in adolescence than the reverse (Loeber & Keenan, 1994). In addition, it may be that the pathways differ across gender, with early depression playing a greater role in facilitating emergence of serious CP for girls. However, the application of these models has not yet been considered in normative samples including both genders. In the current study, we examine the fit of these models for girls, as well as attempting to replicate Capaldi's (1991, 1992) results for boys.

Depressive symptoms, CP, and early adolescent adjustment

Both CP and depression have been shown to individually predict problems in early adolescent adjustment outcomes (Birmaher et al., 1996). We extended Capaldi's (1991,1992) study design with boys to investigate links between elevated symptom patterns and early adolescent adjustment outcomes for girls and boys in four domains: academic adjustment, social competence, antisocial peer relations, and substance use. We were particularly interested in investigating whether a) symptomatology patterns and adjustment outcomes demonstrated different relations across gender, and b) co-occurring CP and depressive symptoms predict worse adjustment in specific or multiple domains (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999). Capaldi (1991) found that the co-occurring group demonstrated more academic and peer problems than other groups, and demonstrated problems associated with depression combined with those associated with CP. Few studies have examined co-occurrence and multiple adjustment domains for girls, but those that have suggest increased risk for drug use and suicide attempts (Hammen & Compas, 1994; King et al., 1996; Miller-Johnson et al., 1998).

Methodological issues in assessing symptomatology patterns

While diagnostic measures are widely used to determine co-occurrence, it has been argued that dimensional measures may be more useful because they measure elevated symptomatology that is likely to reach clinical levels over time (Gotlib, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1995; Hammen & Rudolph, 2003), Dimensional measures have also been considered more reflective of actual depressive symptom presentation, developmentally derived, practical in identifying problem patterns in community samples with low base rates, and useful for comparing across same-age and gender cohorts (Hankin, Fraley, Lahey, & Waldman, 2004; Nottelmann & Jensen, 1995). In this study, analyses with continuous measures allowed us to investigate relations across the entire sample, to identify patterns across the range of symptom levels, and to compare our results to other community samples using dimensional approaches (Compas & Hammen, 1994). Diagnostically-based systems have been criticized as having arbitrary cut-offs and perhaps leading to inaccurate rates of co-occurrence (Angold et al., 1999; Ruseio & Ruscio, 2000). However, there may be important predictive relations that are primarily accounted for by extreme groups, and thus categorical approaches may also add important information (Haslam, 2003). Identifying the best source of information is an additional issue. Multiple informant data are preferable to increase reliability and validity and to capture average behavior across contexts, yet specific informants may be considered more valid for particular symptoms and settings. Self-reports are important sources for internalized symptoms, such as depression, and covert CP (Hinshaw, Simmel, & Heller, 1995), whereas teachers might be the best reporters for overt CP because they have access to a greater range of comparison youth (Stanger & Lewis, 1993), Finally, many studies of symptom patterns have involved small clinical samples, which tend to overestimate prevalence and prevent generalization to community populations (Angold & Costello, 1993).

Purpose of this study

This study examined the relations among symptom patterns and adjustment problems using two approaches (i.e., categorical and continuous), each of which addressed different but complementary questions. The categorical approach examined continuity and change in problems among those already at risk in 5th grade (i.e, those with elevated problems), to compare to Capaldi's (1991, 1992) and others' results. We created groups based on elevated symptoms at 5th grade: conduct problems only (CP), depressive symptoms only (DEP), co-occurring problems (CO-OCCUR), low problems (LOW), and those with some symptoms but not meeting elevation criteria (MED). We then investigated how individuals moved across or remained in groups over the two-year period. We hypothesized that overall prevalence rates of elevated problems would increase from 5th to 7th grade. We expected similar rates of depressive symptoms at 5th grade across gender, but higher rates for girls in 7th grade. We expected higher rates of CP for boys, but smaller differences across gender in 7th grade. More boys were expected to have co-occurring problems, but rates would increase more for girls across time. We thought boys would be more likely to move from the LOW or DEP group to a high CP group (CO-OCCUR or CP), and that CP and CO-OCCUR groups would show high stability (Capaldi, 1992). As depression rates increase for girls through adolescence, we thought girls would be more likely than boys to move from the CP to CO-OCCUR group, and that LOW group girls would move into a high depressive symptom group (DEP or CO-OCCUR group).

Our next task was to investigate predictive temporal relations between CP and depressive symptoms—does early depression predict the development of later CP, or the reverse? Using regression analyses, we investigated how levels of CP and depressive symptoms assessed with continuous measures in 5th grade would predict these same problems in 7th grade, across the entire sample and separately for girls and boys. We expected that CP would predict the development of later depressive symptoms more strongly than the reverse for boys (Capaldi, 1992), but were unsure what the pattern would be for girls. The last area of inquiry was to identify predictive relations between early symptom patterns and later adjustment problems, including academic performance, social competence, antisocial peer involvement, and substance use. We expected that CP and depressive symptoms would predict adjustment problems, but gender differences might emerge in strength and specificity of these relations. We expected that those youth demonstrating early co-occurring problems would show more adjustment problems across multiple adjustment domains, as compared to other patterns (Angold et al., 1999; Capaldi, 1992).

Method

Participants

Data were collected as part of an ongoing, longitudinal, multi-site investigation of the development and prevention of CP in children, the Fast Track Project (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group [CPPRG], 1992). Data derive from Durham, NC; Nashville, TN; Seattle, WA; and central Pennsylvania. At each site, high-risk schools were selected and randomly assigned to intervention and comparison conditions. Within schools, a multistage, multi-informant screening process was used to identify kindergartners with high disruptive behavior scores. Approximately equal numbers of these high-disruptive children from each site were enrolled in the intervention or high-risk comparison group. Three cohorts were recruited and interviewed annually. In order to also study typical development processes, a normative group was also formed from participants who were randomly sampled from the original comparison schools, but stratified by the teacher-completed behavior problem ratings to reflect normative population rates (N = 387; see Lochman & CP-PRG, 1995, for further details). The current study utilizes data from the normative sample. However, to increase power to detect group differences, we also included the high-risk comparison participants who were not also part of the normative sample (n = 76). This results in a total of 463 youth from Cohort I, none of whom received any intervention. Participants with completely missing data at 5th and 7th grade (n = 32; 7%) were excluded from analyses. The sample thus equaled 431. The sample was 54% male (n = 235), and 49% were ethnic minority youth (44.5% African-American; and 4.5% other). The modal Hollingshead SES indicator was 5, indicating a low-income sample (range = 3–5). This sample is slightly overrepresented in risk for disruptive behavior.

Procedures

CP and depressive symptoms were assessed by multiple reporters in home interviews in the summers after the youth completed 5th and 7th grade, and by teacher report during the late spring of those same years. The teacher who knew the child best was identified by the school counselor and parent and this teacher assessed the level of youth CP. Teacher report of depressive symptoms was not collected because teachers are not considered valid informants for internalizing problems (Stanger & Lewis, 1993). Early adolescent adjustment outcomes were assessed using multiple reporters during 7th grade interviews. All participants completed survey questionnaires and were individually interviewed. Because youth had many teachers in 7th grade, multiple teacher reports, when available, were combined.

Missing data

Missing data were multiply imputed using NORM software (Schafer, 1997). Most missing data were due to attrition. Missingness patterns reflected that data adequately conformed to missing-at-random assumptions (Schafer, I997).1 Preliminary analyses, including reliability and scale construction, were conducted prior to multiple imputation to accurately reflect psychometric properties and to reduce variables to a feasible number for multiple imputation. Independent analyses were performed on 10 imputed date sets. Parameter estimates and variances were then combined to obtain an unbiased estimate of the population values, with which significance testing was performed. For categorical analyses of stability and change, significance tests could not be calculated using multiply imputed datasets. Results were calculated using one singly imputed dataset and presented as purely descriptive, This dataset was created using an Expectation-Maximization algorithm covariance matrix from NORM (Dempster, Laird, & Rubin, 1977; Graham, Cumsilie, & Elek-Fisk, 2003).

Construct formation

Because multiple informants and measures were combined in order to reduce measurement error, a careful construct building approach was used. For CP, depressive symptoms, and adjustment problem constructs, indicator variables were first created by measure and informant (e.g., normed subscale scores). Following Capaldi (1991), indicators used in each combined construct score met the following criteria: a) internal consistency through item-total correlations of .3 or above, and alpha coefficients of .6 or above; and b) factor loadings for a forced one-factor solution of 3 or above within each construct. These criteria resulted in a few dropped items within indicators. Indicators were then standardized and combined within year to create an overall construct score (see Appendix A). We standardized across the sample, rather than within gender, in order to be able to meaningfully contrast boys' and girls' prevalence of problems across mis period. Table 1 shows means and SDs of each indicator prior to standardization, across imputed datasets, and after constructs were created.

Appendix A.

Constructs and indicators

| Construct | Measure | Reporter | Available N | # of items | Time frame | Sample item | a alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conduct problems—5th grade | Things that you have done (CPPRG, 2000a, 2000b, 2000c, 2000d) | Child | 395 | 17 | Past year | Have you purposefully destroyed or damaged things not belonging to you? | .80b |

| Child behavior checklist (Achenbach, 1991b) | Parent | 406 | 28 | Past 6 months | Physically attacks people | .93 | |

| Teacher's report form (Achenbach, 1991a) | Teacher | 394 | 33 | Past 6 months | Gets in many fights | .97 | |

| Conduct problems—7th grade | Self-report of delinquency (Elliott et at., 1985) | Child | 378 | 33 | Past year | Have you attacked someone with the intent to hurt them? | .82a |

| Child behavior checklist (Achenbach, 1991b) | Parent | 383 | 32 | Past 6 months | Disobediant at home | .92 | |

| Teacher's report form (Achenbach, 1991a) | Teacher | 374 | 33 | Past 6 months | Lying or cheating | .97 | |

| Depression—5th grade | Reynolds child depression scale (Reynolds, 1989) | Child | 395 | 26 | None noted | I feel that no one cares about me | .87 |

| Child behavior checklist (Achenbach, 1991b) | Parent | 406 | 10 | Past 6 months | Cries a lot | .68 | |

| Depression—7th grade | Reynolds child depression scale (Reynolds, 1989) | Child | 379 | 30 | None noted | I have trouble sleeping | .87 |

| Child behavior checklist (Achenbach, 1991b) | Parent | 383 | 10 | Past 6 months | Feels worthless or inferior | .73 | |

| Adjustment outcomes—7th grade | |||||||

| Academic achievement | Teacher's rating of student adjustment | Teacher | 388 | 3 | None noted | Student academic performance. (Likert scale reflecting skill level) | .92 |

| Social competence teacher report-revised | Teacher | 374 | 5 | None noted | Able to read grade level and answer questions. (5 pt Likert scale reflecting how well this describes student). | .92 | |

| School adjustment-parent report | Parent | 380 | 3 | Past school yr | My child has an easy time handling academic demands | .69 | |

| Social competence | Social competence teacher report-revised | Teacher | 373 | 10 | None noted | Shows empathy and compassion. (5 pt Likert scale reflecting how well this describes student). | .93 |

| Teacher's rating of student adjustment | Teacher | 388 | 2 | None noted | The student's ability to develop friendships, get along with peers, and be part of a social network or a group of friends. (Likert scale reflecting skill level) | .83 | |

| School adjustment-parent report | Parent | 380 | 2 | Past school yr | My child did not have as many friends this year | .64 | |

| School adjustment-child report | Child | 379 | 3 | Past school yr | I had a hard time making friends | .62 | |

| Antisocial peer relations | Self report of close friends (O'Donnell, Hawkins, & Abbott, 1995) | Child | 361 | 21 | None noted | (How often) has this friend gotten in trouble with the police? | .89 |

| Substance use | Tobacco, alcohol, & drugs (adapted from Resnick et at., 1997) | Child | 379 | 5 | Past year | (How often) have you smoked cigarettes daily? | .68b |

Cronbach's alpha prior to rescoring (original data) and imputation, unless otherwise noted

Kuder-Richardson 20 Coefficient.

Table 1.

Indicator and construct means for total sample and by gender

| Construct | Measure | Total M (SD)a | Boys M (SD)a | Girls M (SD)a | Percent of data missing (N = 431) | 10 imputed files M (SD)b | Construct M (SD)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conduct problems | |||||||

| 5th grade | Things that you have done | .08 (.11) | .10 (.12) | .06 (.09) | 8.4 | .08 (.12) | .00 (.75) |

| Child behavior checklist | .32 (.38) | .39 (.31) | .25 (.22) | 5.8 | 31 (.29) | ||

| Teacher's report form | .39 (.45) | .51 (.47) | .25 (39) | 8.6 | .40 (.47) | ||

| 7th grade | Self-report of delinquency | .04 (.08) | .05 (.08) | .03 (.07) | 12.3 | .05 (.08) | .00 (.74) |

| Child behavior checklist | .31 (.27) | 38 (.29) | .24 (.23) | 11.1 | .31 (.27) | ||

| Teacher's report form | .45 (.45) | .57 (.47) | .30 (38) | 13.2 | .43 (.45) | ||

| Depressive symptoms | |||||||

| 5th grade | Reynolds child depression scale | .55 (.37) | .57 (.36) | .53 (.57) | 8.4 | .54 (36) | .00 (.79) |

| Child behavior checklist | .16 (.23) | .18 (.25) | .14 (.22) | 5.8 | .16 (.25) | ||

| 7th grade | Reynolds child depression scale | 1.56 (.41) | 1.53 (.37) | 1.59 (.45) | 12.1 | 1.55 (.43) | .00 (.75) |

| Child behavior checklist | .17 (.24) | .19 (.26) | .14 (.22) | 11.1 | .17 (.25) | ||

| Academic achievement | Teacher's rating of student adjustment | 2.79 (1.05) | 2.51 (1.01) | 3.12 (.99) | 10.0 | 2.75 (1.09) | .00 (.86) |

| Social competence teacher report-revised | 2.63 (1.45) | 2.3 (1.45) | 3.00 (1.36) | 13.2 | 2.55 (1.51) | ||

| School adjustment-parent report | 3.09 (.94) | 2.83 (.89) | 338 (.91) | 11.8 | 3.02 (.91) | ||

| Social competence | Social competence teacher report-revised | 3.16 (.90) | 2.86 (.88) | 3.52 (.80) | 10.0 | 3.19 (.93) | .00 (.81) |

| Teacher's rating of student adjustment | 2.92 (1.09) | 2.61 (1.04) | 3.27 (1.04) | 13.4 | 2.97 (1.09) | ||

| School adjustment-parent report | 3.64 (.87) | 3.42 (.92) | 3.89 (.73) | 11.8 | 3.62 (.84) | ||

| School adjustment-child report | 4.14 (.60) | 4.01 (.59) | 4.28 (.58) | 12.1 | 4.17 (.60) | ||

| Antisocial peer relations | Self report of close friends | 1.47 (.50) | 1.56 (.55) | 1.38 (.42) | 18.1 | 1.48 (.53) | 6.94 (1.0) |

| Substance use | Tobacco, alcohol, & drugs | .16 (.20) | .17 (.21) | .14 (.19) | 12.1 | .16 (.21) | .00 (1.0) |

Means and standard deviations prior to imputation (available data only).

Means and standard deviations averaged across the 10 imputed datasets.

Means and standard deviations after standardizing and averaging the indicator variables for total sample, using singly imputed dataset.

Measures

Conduct problems

At the end of 5th grade, youth completed the 32-item Things That You Have Done survey (CPPRG, 2000d; adapted from the Self-Report Delinquency Scale; SRD; Elliott, Ageton, & Huizinga, 1985). This measure assesses frequency of aggressive and delinquent behaviors. Because of a high rate of zero responses, items were dichotomized and the mean of 17 items was calculated, producing a percentage of the total items that the youth reported committing. At the end of 7th grade, youth completed the SRD (Elliott et al., 1985). The 28 items were dichotomized and a mean score capturing the percentage of problems was created. Parents rated 112 behavior items on a 3 point scale on the Child Beahvior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991b) at each home visit. The mean of 32 of 33 items on the Externalizing broad-band scale was used to measure parent-report of CP (one item, “uses alcohol or drugs,” was removed because drug use was an outcome variable). Teachers completed the Externalizing scale from the Teacher's Report Form (TRF; Achenbach, 1991a) in the spring of 5th and 7th grade. A mean score of 33 of 34 items (“uses alcohol or drugs” was removed) was used as teacher report of CP. There is extensive documentation of the validity and reliability of the CBCL and TRF (Achenbach, 1991a, b). A composite cross-reporter measure of CP was created by averaging z-scores of parent, teacher, and youth report, separately for 5th and 7th grade. Indicator variables demonstrated high loadings onto a forced one-factor solution in PCA (loadings = .71–.74), To assess internal consistency of cross-reporter measures, composite alphas were calculated taking into account Cronbach's alpha and variance and covariances between indicators. The composite α for the cross-reporter measure of CP was .97.

Depressive symptomatology

Youth completed the Reynolds Child Depression Scale (RCDS; Reynolds, 1989), a 30-item measure assessed on a 4-point Likert scale (from “not at all” to “much of the time”) at the end of 5th and 7th grade. The mean of the 24 items that conformed to construct criteria was created. For parent report, a mean of 7 items from the Anxious/Depressed subscale of the CBCL, chosen using conceptual and empirical criteria, was derived (Lengua, Sadowski, Friedrich, & Fisher, 2001). A cross-reporter composite was created by averaging z-scores of parents and youths for 5th and 7th grade. The cross-reporter measure demonstrated good internal consistency (composite αs = .83 and .85). The two indicator variables loaded onto forced one-factor solutions within grade at a high level (i.e., .78).

Early adolescent adjustment

The adjustment measures were selected to closely follow Capaldi (1992), and were assessed by multiple informants (parent-, youth-, and/or teacher-report) at the end of 7th grade. For teacher report measures, 26% of the sample had data from three teachers, 48% from two teachers, and 26% from one teacher. When there were multiple teachers, scores were averaged. There were no significant differences across mean scores for youth with different numbers of teachers.

Academic adjustment

Teachers rated the student's level of skill on a 5-point scale in six areas using the Teacher's Rating of Student Adjustment (TRSA; CPPRG, 2000b). Three items were used (academic performance, academic motivation, and personal maturity related to work completion). Agreement among teachers for each item using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC; Shrout & Fleiss, 1979) ranged from .80 to .82. Teachers also completed the Social Competence Teacher Report-Revised (SC-TR; CPPRG, 2000a), a 17-item measure of academic competence, prosocial behavior, and emotion regulation. The five items related to academic competence, rated on a 6-point scale, were used for this construct. Parents and youth completed parallel measures that assessed both academic and social adjustment to school. The School Adjustment-Parent Report (SA-PR; CPPRG, 2001a) is a 20-item measure rated on a 5-point scale. Three items were used for parent report of academic adjustment. The items from the youth report version (SA-CR; CPPRG, 2001a) demonstrated poor psychometric properties and are not used here. A composite cross-reporter construct was created by combining z-scores from the parent and two teacher subscales. Because two of three measures in the composite were rated by teachers, teacher report was weighted somewhat more. However, this was deemed acceptable given that teachers are likely subject to less bias and more information to rate any given child academically. Analyses indicated that the cross-reporter construct was internally consistent (composite α = .91).

Social competence

Teacher-reported items assessing prosocial behavior from the SCTR-R and items from the TRSA measuring the domains of social skills and relationships with adults were used. ICCs across multiple teacher reports ranged from .65 to .71. Parent and youth report was assessed using the SA-PR and SA-CR. A cross-reporter measure was created by combining standard z-scores from youth, parent, and two teacher subscales, with high internal consistency (composite α = .90).

Antisocial peer relations were assessed by youth report on the Self-Report of Close Friends (O'Donnell, Hawkins, & Abbott, 1995). For each of two best friends and for the larger peer group, seven items rated on a 4-point scale assessed peer delinquency, substance use, and other problem behavior. One item was removed due to a low item-total score correlation; others were averaged for a total score.

Substance use was assessed using the Tobacco, Alcohol, and Drugs survey, adaptated from the survey used in the New York Longitudinal Study (Resnick et al., 1997). A mean was created combining five dichotomous items (alcohol, smoking, marijuana, cocaine, and “other illegal drug” use).

Gender

Gender was coded 1 for males, 0 for females.

Results

Rates, continuity, and change in symptom patterns over time

We first investigated the question: How do CP and depressive symptoms manifest and change from 5th to 7th grade? Table 1 presents the means of single-reporter measures of CP and depressive symptoms by grade and gender, for available data prior to imputation. Examination of these scores allows for a rough estimate of differences across gender, and of absolute change from 5th to 7th grade. As expected, all informants report greater levels of CP for boys, and approximately equal levels of depression for boys and girls in 5th grade. The means of CP and depression were quite stable from 5th to 7th grade, with one exception: the rate of child report of depression nearly triples. Contrary to expectation, CP means did not increase for boys or girls (except slight increase for teacher report). It is important to note that indicators of CP are not identical in 5th and 7th grade. However, as youth-report items are very similar across the two measures and total scores were standardized and moderately correlated (r = .36, p < .01), we directly compare these scores.

To examine patterns among youth with elevated symptoms, consistent with prior studies (Capaldi, 1991; Miller-Johnson et al., 1998), a cut-off of .5 SD above the mean at 5th grade for the entire sample (using imputed data) was used to create five distinct symptomatology groups from the continuous, standardized multi-reporter constructs of CP and depression. The .5 SD cut-off was used to identify youth with meaningfully elevated level of symptoms,2 and to obtain large enough group sizes across gender to be able to conduct predictive analyses with adequate power (Capaldi, 1991; Miller-Johnson et al., 1998). Three elevated groups at 5th grade were established as follows. Participants in the CP alone group (CP) had a score on the CP construct .5 SD above the mean and a score on the depression construct at or below the mean. Participants in the depressive symptoms alone group (DEP) had the opposite pattern. Participants in the co-occurring CP and depressive symptoms group (CO-OCCUR) scored at least .5 standard deviations above the mean on both depressive symptoms and CP. The two comparison groups were established as follows. Those in the group with neither problem (LOW) scored at or below the mean on both measures. While we were primarily interested in comparing extreme groups, we report some results for those participants who had scores that fell between the mean and .5 SD above the mean at 5th grade (MED, with essentially “medium” or mixed levels of symptoms), in order to examine patterns of youth who desist from elevated problems. The cut-off criteria of .5 SD resulted in groups in which girls demonstrate a higher level of impairment than boys in that same group. Investigation of mean differences by gender in the singly-imputed dataset indicated that boys on average had significantly higher CP at both grades, and depressive symptom ratings in 5th grade only, than girls.

The cut-off scores for 5th grade scores were utilized to assign symptomatology groups in 7th grade. Table 2 shows the number and percentage of youth in each group by gender, to present prevalence rates. Differences in prevalence at both years are presented for descriptive purposes (i.e. trends in the data). Overall, prevalence rates did not increase as expected, although there was a slight increase in elevated problems for girls and slight decrease for boys. A larger percentage of boys than girls met criteria for membership in an elevated problems group in both 5th (34.47% vs. 21.42%) and 7th grade (31.49% vs. 28.57%). Relatively small numbers of youth met criteria for specific elevated symptom groups. As we expected, at 5th grade, boys were more likely to meet criteria for an elevated CP group (CP or CO-OCCUR) than girls, and girls were more likely to be in the elevated depressive (DEP) or low symptomatology (LOW) groups. The percentage of boys with co-occurring symptomatology was about two times that of girls.' The rates of co-occurrence did not increase more for girls as expected. We thought that rates would be similar for girls and boys for early depressive symptoms, and higher rates (bigger difference) for girls in 7th grade; this was supported by the results. For depressive symptoms, girls' rates increased and boys' rates decreased such that at 7th grade, there was a three-fold difference between them. For CP, results showed that boys were about three times more likely to have CP than girls in 5th grade, but only two times as likely in 7th grade. Rates in lower-level problem groups were stable for boys, while fewer girls met criteria for the LOW group in 5th as compared to 7th grade.

Table 2.

Means of construct scores and percentage of youth in each group by grade and gender

| Groups based on standardized scores derived from 5th grade measures | 5th grade | 7th grade | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls |

Boys |

Girls |

Boys |

|

| % of girls (n) | % of boys (n) | % of girls (I) | % of boys (n) | |

| Elevated groups | ||||

| CO-OCCUR group | 8.67 (17) | 14.89 (35) | 8.67 (17) | 15.74 (37) |

| Depressive score M (SD) | 1.31 (.81) | 1.15 (.85) | .98 (1.02) | .53 (.74) |

| CP score M (SD) | .99 (.60) | 1.18 (.52) | .75 (1.01) | .84 (.68) |

| CP group | 3.57 (7) | 14.47 (34) | 5.10 (10) | 11.06 (26) |

| Depressive score M (SD) | −.39 (.33) | −.39 (.24) | .38 (.92) | −.12 (.64) |

| CP Score M (SD) | 1.00 (.58) | .90 (.45) | .37 (.51) | .74 (.91) |

| DEP group | 9.18 (18) | 5.10 (12) | 14.79 (29) | 4.68 (11) |

| Depressive score M (SD) | .95 (.40) | .85 (.57) | .48 (.88) | .23 (.67) |

| CP Score M (SD) | −.34 (.21) | −.25 (.20) | −.19 (.57) | −.16 (.29) |

| TOTAL in elevated symptom groups | 21.42 (42) | 34.47 (81) | 28.57 (56) | 31.49 (74) |

| Comparison groups | ||||

| Low group | 56.63 (111) | 32.34 (76) | 49.94 (92) | 33.62 (79) |

| Depressive score M (SD) | −.57 (.30) | −.49 (.28) | −.32 (.52) | −.32 (.58) |

| CP score M (SD) | −.62 (.24) | −.47 (.25) | −.52 (.37) | −.26 (.47) |

| MED group | 21.94 (43) | 33.20 (78) | 24.45 (48) | 34.99 (82) |

| Depressive score M (SD) | −.21 (.43) | .22 (.67) | −14 (.73) | .11 (.73) |

| CP score M (SD) | −.01 (.48) | .24 (.59) | −.16 (.48) | .25 (.65) |

Note. The results presented are from the singly imputed dataset. CO-OCCUR: Co-occurring CP and depression, CP: Conduct problems, DEP: Depressive symptomatology, LOW: No elevated depression or CP, MED: level of symptomatology for those individuals was between the mean and .5 SD above the mean for either CP or depression, or both.

We next examined how youth who demonstrated elevated problems in 5th grade fared in early adolescence. Table 3 investigates the movement between groups for youth with elevated symptoms at 5th grade as they move to 7th grade. The percentages reflect the youth who were in a particular group in 5th grade who remained (stability) or moved to a different group (change) by 7th grade. We expected that CO-OCCUR and CP groups would demonstrate strong stability; this was partially supported. Among youth in the three symptomatology groups, the CO-OCCUR group demonstrated strong stability, with 46.15% remaining two years later. The LOW group demonstrated the strongest stability over the 2 years (64.17%). Only 29.26% of the CP youth remained in CP, but 7 of the 41 youth who initially met criteria for the CP group developed elevated co-occurring problems. Overall, 14.63% of the youth who were in the elevated CP, and 20% with elevated depressive symptoms moved into the LOW category by 7th grade, while only 3.84% of those in me CO-OCCUR group decreased in symptoms enough to fall into the LOW group, indicating lower levels of true desistance among co-occurring youth.

Table 3.

Stability and change from 5th grade groups to 7th grade groups

| Seventh grade group | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO-OCCUR | CP | DEP | LOW | MED | Total in 5th grade | ||||||

| 5th grade group | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | n | n | |

| All youth | |||||||||||

| CO-OCCUR | 46.15 | 24 | 7.69 | 4 | 7.69 | 4 | 3.84 | 2 | 34.61 | 18 | 52 |

| CP | 17.07 | 7 | 29.26 | 12 | 2.43 | 1 | 14.63 | 6 | 36.58 | 15 | 41 |

| DEP | 14.29 | 3 | 3.33 | 1 | 36.66 | 11 | 20.00 | 6 | 30.00 | 9 | 30 |

| LOW | 2.13 | 4 | 3.74 | 7 | 6.41 | 12 | 64.17 | 120 | 23.52 | 44 | 187 |

| MED | 24.79 | 16 | 9.91 | 12 | 9.91 | 12 | 30.57 | 37 | 36.36 | 44 | 121 |

| Total in 7th grade | 54 | 36 | 40 | 171 | 130 | 431 | |||||

| Girls | |||||||||||

| CO-OCCUR | 47.05 | 8 | 0.00 | 0 | 17.65 | 3 | 5.88 | 1 | 29.41 | 5 | 17 |

| CP | 28.57 | 2 | 14.28 | 1 | 14.28 | 1 | 0.00 | 0 | 42.86 | 3 | 7 |

| DEP | 10.52 | 2 | 5.56 | 1 | 38.89 | 7 | 22.22 | 4 | 22.22 | 4 | 18 |

| LOW | 1.80 | 2 | 1.80 | 2 | 8.10 | 9 | 66.67 | 74 | 21.62 | 24 | 111 |

| MED | 6.98 | 3 | 13.95 | 6 | 20.93 | 9 | 30.23 | 13 | 27.91 | 12 | 43 |

| Total in 7th grade group | 17 | 10 | 29 | 12 | 48 | 196 | |||||

| Boys | |||||||||||

| CO-OCCUR | 45.71 | 16 | 11.43 | 4. | 2.86 | 1 | 2.86 | 1 | 37.14 | 13 | 35 |

| CP | 14.71 | 5 | 32.35 | 11 | 0.00 | 0 | 17.65 | 6 | 35.29 | 12 | 34 |

| DEP | 8.33 | 1 | 0.00 | 0 | 33.33 | 4 | 16.67 | 2 | 41.67 | 5 | 12 |

| LOW | 2.63 | 2 | 6.58 | 5 | 3.95 | 3 | 60.53 | 46 | 26.32 | 20 | 76 |

| MED | 16.67 | 13 | 7.69 | 6 | 3.85 | 3 | 30.77 | 24 | 41.03 | 32 | |

| Total in 7th grade group | 37 | 26 | 11 | 79 | 82 | 235 | |||||

Note. %: the percentage of 5th grade youth within a group (row) who remained or changed to another group by 7th grade. CO-OCCUR: Co-occurring CP and depression, CP: Conduct problems, DEP: Depressive symptomatology, LOW: No elevated depression or CP, MED: level of symptomatology for those individuals was between the mean and .5 SD above the mean for either CP or depression, or both.

The stability and change percentages varied for girls and boys. Boys were more likely to have and maintain elevated CP than girls, yet boys and girls were equally likely to move from lower-level or depressive symptoms to high-CP groups. As we hypothesized, girls were more likely than boys to move from CP to CO-OCCUR groups. However, because there was a very small number of girls who met criteria for elevated CP in 5th grade (n = 7), these results must be interpreted cautiously and will need to be replicated in larger samples. Results confirmed the hypothesis that girls would be more likely to move from lower-level symptom groups to high-DEP groups than boys. Approximately 38% of girls with low or medium problems developed elevated depressive symptoms (CO-OCCUR or DEP) by 7th grade, and only 26% of boys followed the same pattern. For the CO-OCCUR group, while approximately half of boys and girls remained in this group, if they did move, boys were more likely to move into the elevated CP group or MED group, and CO-OCCUR girls were more likely to move into the elevated depressive group or MED group (no girls who initially met criteria for CO-OCCUR moved to CP). None of the CP boys moved into the DEP group, and none of the boys in the DEP group moved into the CP alone group, whereas girls in these same groups showed more variability with some showing opposite elevated symptom patterns in 7th grade. Of the youth that moved, girls were more likely to move to the DEP group whereas boys were approximately equally likely to move to the CP, DEP, or CO-OCCUR group.

It is important to note that interpretation of stability and change by gender is complicated by the fact that symptom levels may have increased or decreased for all boys or all girls from 5th to 7th grade. If there were systematic differences across gender, elevated group status in 7th grade may not accurately reflect the numbers of youth by gender that should be considered truly elevated. However, we grew confident in the interpretation after examining unstandardized means over time (see Table 2) and means within groups (see Table 3), as each group tended to follow similar patterns across 5th to 7th grade for boys and girls. All youth demonstrated regression to the mean, with lower levels of symptoms on average in 7th grade, but the magnitude of the differences is similar across gender.

To summarize the above results, based upon elevated symptom groups created using total sample averages and examining tendencies by gender, approximately 60% of girls and 46% of boys who demonstrated elevated CP and depressive symptoms at 5th grade remained elevated in some problem at 7th grade. Approximately half of both boys and girls who demonstrated co-occuring problems in 5th grade remained elevated in both problems in 7th grade. Boys were more likely to remain in the elevated CP only group, while girls with elevated CP in 5th grade were more variable in 7th grade. Girls appeared more likely to move from depressive symptoms only to a high CP group. Those with the lowest levels of problems mostly remained non-symptomatic, with girls with initially low problems showing a slightly higher tendency to develop elevated depressive symptoms 2 years later than boys.

Predictive temporal relations between CP and depressive symptoms

We next turned to examining a related, but different question: Do early CP predict the development of later depressive symptoms more strongly than the reverse, as Capaldi (1991) found for boys? To address this, analyses using the continuous cross-informant measures were conducted. First, we present pearson product-moment correlations for cross-sectional and cross-time relationships. Depressive symptoms and CP were moderately correlated in 5th (r = .42, p < .001) and in 7th (r = .40, p < .001) grade. Broken down by gender, moderate correlations emerged for boys (r's = .36 and .42, p < .001) and girls (r's= .43 and .36, p < .001). For cross-time relations, Pearson r's ranged from .30 (5th grade CP and 7th grade depressive symptoms) to .69 (5th and 7th grade CP), all significant at the p < .001 level. Fisher r-to-z analyses indicated that the differences in correlations did not significantly vary across gender or time.

Regression analyses were used to examine the longitudinal prediction of depressive symptoms and CP at 7th grade from 5th grade symptomatology. Depressive symptoms and CP scores at 5th grade were entered simultaneously in a single step to predict 7th grade depressive symptoms, and a separate regression utilizing the same model predicted 7th grade CP. For the whole sample, depressive symptoms in 7th grade were significantly predicted by depressive symptoms in 5th grade (B = .53, SE = .04, p < .001) but not CP in 5th grade (B = .43, SE =.05, p =.37). CP in 7th grade was significantly predicted by early CP (B = .66, SE = .04, p < .001), but not by depressive symptoms in 5th grade (B = .42, SE=.04, p = .28).

We then investigated relations by gender using two methods. Separate regression models by gender predicting 7th grade problems demonstrated very similar results for boys and girls, and matched the results obtained with the total sample. That is, early CP, but not depressive symptoms predicted later CP; early depressive symptoms, but not CP, predicted later depressive symptoms. The second method involved regressions computed for the total sample, with 5th grade depressive symptoms, CP, gender, and all two-way interaction terms entered as predictors of depressive symptoms at grade 7, and then a separate regression equation for CP at 7th grade. For 7th grade CP, both initial CP (B = .60, SE =.08, p < .001) and gender (B =.18, SE =.06, p < .01) were significantly predictive, and depressive symptoms and interaction terms were nonsignificant For depressive symptoms in 7th grade, only 5th grade depressive symptoms attained significance (B = .63, SE= .07, p < .001). In summary, when problems are assessed continuously, boys and girls show similar patterns of relations between concurrent CP and depressive symptomatology, and similar predictive relations between early and later symptoms. When controlling for early CP, early depressive symptoms predicted later depressive symptoms. When controlling for early depressive symptoms, early CP predicted later CP. These results differ from Capaldi's (1991) findings for boys.

Predictive relations between early symptom patterns and later adjustment

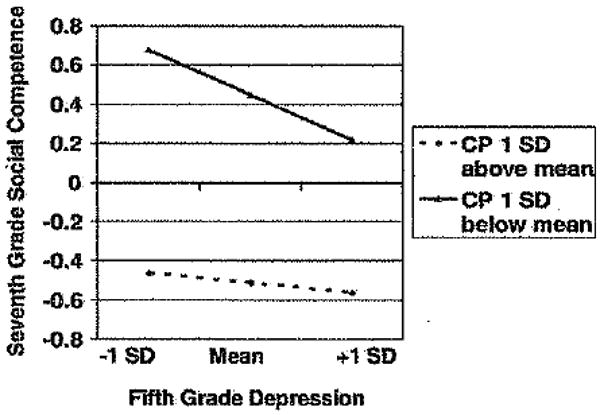

We next examined the relative strength of 5th grade symptomatology (again using both continuous and categorical approaches) in predicting four early adolescent adjustment outcomes: academic adjustment, social competence, involvement with antisocial peers, and substance use. Regression equations assessing relations among 5th grade CP, depression, and adjustment outcomes tested the hypothesis that early co-occurring problems would be strongly associated with adjustment problems in multiple domains across the entire sample. Continuous measures of early CP, depression, and gender were entered in one step. Next, the CP by depression interaction was entered on the second step. Then, the CP by gender interaction term was entered. Finally, the depression by gender interaction term was entered, removing the CP by gender interaction. As shown in Table 4, gender was significantly associated with academic adjustment and social competence (B = −.39, SE=.08, p < .01, and B = −.30, SE= .06, p < .01, respectively). In both cases, girls demonstrated higher functioning than boys. Both CP and depression significantly predicted all of the adjustment outcomes (with the exception that depressive symptoms showed only a trend in predicting substance use, and did not significantly predict antisocial peers). When tested incrementally, (i.e., with gender, CP, and DEP on one step, and the interaction term on the second step), the interaction between CP and depression significantly added to the prediction of academic adjustment (B = .11, SE=.06, p < .05; R2 changes = .01, p < .05) and social competence (B = .09, SE= .05, p < .05, R2 change = .01, p < .05). Follow-up analyses of the interaction results using the Aiken and West (1991) method of testing for significance of simple slopes indicated that for CP 1 SD above the mean, the level of social competence was already quite low and depression was not a significant predictor of social competence (B = − .05, SE= .05, p = .30; R2 change = .002, p = .27). When CP were 1 SD below the mean, the initial level of social competence was much higher and depression was a significant predictor of social competence (B = − .23, SE= .07, p < .001, R2 change = .01, p < .05; see Fig. 1). No gender by symptoms interaction terms explained unique variance when entered on step 3 (not shown in Table 4). A similar pattern emerged in follow-up analyses for academic adjustment.

Table 4.

Means, unstandardized regression coefficients and standard errors for the relationship between continuous measures of symptomatology and gender in fifth grade and adjustment outcomes in seventh grade

| Adjustment outcomes | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic adjustment |

Social competence |

Antisocial peers |

Substance use | |||||||||

| M (SD) | ||||||||||||

| Girls: (n = 196) | .32 (.80) | .32 (.80) | − .18 (.87) | −.09 (.93) | ||||||||

| Boys: (n = 235) | −.27 (.82) | − .27 (.80) | .15 (1.08) | .08 (1.05) | ||||||||

| Significance (t) | p < .001 | p < .001 | p; < .001 | p = .07 | ||||||||

| Regression analyses | B (SE) | R2 | R2 ch | B (SE) | R2 | R2 ch | B (SE) | R2 | R2 ch | B (SE) | R2 | R2 ch |

| Predictors: | ||||||||||||

| Step l: | ||||||||||||

| Gender | −.39**(.08) | −.30** (.06) | .15 (.10) | −.01 (.10) | ||||||||

| CP | −.35**(.06) | −.55** (.05) | .32** (.07) | .33** (.07) | ||||||||

| Depressive | −.12*(.06) | −.14** (.04) | .12 (.07) | .12 + (.07) | ||||||||

| .21 | .21** | .42 | .42** | .11 | .11** | .09 | .09** | |||||

| CP X depression | .11* (.06) | .22 | .01* | .09* (.05) | .43 | .01* | .01 (.07) | .11 | .00 | −.02 (.07) | .09 | .00 |

| F = 30.25, p < .001 | F = 83.19, p < .001 | F = 11.32, p < .001 | F = 10.18, P < .001 | |||||||||

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01.

Fig. 1.

Interaction between fifth grade CP and depression as predictors of seventh grade social competence

A second strategy involving the categorical elevated symptomatology groups was then utilized. For each outcome, mean differences for each pairwise comparison among the symptomatology groups were tested via dummy coding in a regression model. This involved testing three regression models, each of which included gender and the appropriate three dummy coded pairwise comparisons (e.g., first regression included CO-OCCUR vs. LOW, CO-OCCUR vs. CP, CO-OCCUR vs. DEP; second regression included all comparisions between CP and other groups, third regression included all comparisons between DEP and other groups). Because this method resulted in several tests of mean differences, thus increasing the risk for Type I error, Bonferroni correction was utilized (p < .008). The MED group was not included in these analyses because we wanted to examine differences across extreme groups, reduce the number of significance tests and risk for Type I error, and increase interpretability of significant group differences. In Table 5, we present the means and SDs of the adjustment outcomes for the five symptom groups and the significant differences (unstandardized regression coefficients) for planned comparisons. In general, the CO-OCCUR group demonstrated the highest mean problem scores, with CP, DEP, and LOW groups demonstrating progressively lower problem scores, in academic adjustment, social competence, antisocial peers, and substance use. Gender significantly predicted academic adjustment and social competence, with girls showing higher functioning. Interaction terms testing gender by initial levels of symptoms were entered last, and none were significant (not shown in Table 5). For all adjustment outcomes, the CO-OCCUR group demonstrated significantly more problematic scores than the DEP and LOW groups. The CP group showed greater problems than the LOW group on all domains, and significantly more problems in academic and social adjustment that the DEP group. The DEP group differed from the LOW group only on level of social competence (lower competence shown by DEP). The CP and CO-OCCUR group means did not significantly differ for any of the adjustment domains, but were associated with high levels of problems across all domains.

Table 5.

Means and unstandardized regression coefficients in the relationship between categorical symptomatology groups assigned in fifth grade and adjustment outcomes in seventh grade

| Adjustment outcomes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic adjustment | Social competence | Antisocial peers | Substance use | |

| M (SD) | ||||

| CO-OCCUR | −.41 (.78) | −.66 (.76) | .49 (1.29) | .53 (1.13) |

| CP | −.39 (.65) | −.61 (.59) | .31 (1.20) | .33 (1.02) |

| DEP | .15 (.91) | .12 (.70) | −.12 (.83) | −.17 (1.07) |

| LOW | .33 (.83) | .45 (.62) | −.28 (.71) | −.24 (.81) |

| MED | −.23 (.80) | −.24 (.76) | .14 (1.07) | .08 (1.06) |

| Unstandardized regression coefficients (b)–pairwise comparisons | ||||

| CO-OCCUR vs LOW | −.63** | −.99** | .83** | .87** |

| CP vs LOW | −.59** | −.94** | .63** | .63** |

| DEP vs LOW | −.17 | −.28* | .34 | .14 |

| CO-OCCUR vs DEP | −.45* | −.71** | .49* | .73** |

| CP vs DEP | −.41* | −.66** | .28 | .49 |

| CO-OCCUR vs CP | −.04 | −.05 | .21 | .23 |

Note. All pairwise comparisons use Bonferroni correction (p < .017). CO-OCCUR: Co-occuring elevated CP and depressive symptoms, CP: Elevated conduct problems, DEP: Elevated depressive symptomatology, LOW: No elevated depression or CP. MED: level of symptomatology for those individuals was between the mean and .5 SD above the mean for either CP or depression, or both

p < .008,

p < .001.

To summarize results from these analyses, both CP and depressive symptoms were associated with later adjustment problems in multiple domains, even when controlling for gender differences. However, it appeared that the strength of these relationships varied by the patterning of symptoms, and severity. Those youth manifesting co-occurring depression and CP in 5th grade demonstrated significantly lower academic adjustment and social competence, and more antisocial peers and substance use than youth with depressive symptoms only or low problems overall, similar to other studies (Capaldi, 1992; Miller-Johnson et al., 1998). Those youth with CP alone also showed significantly more problems than depressive and low problem groups (similar levels to those with co-occurring problems), particularly in academic and social domains. Youth with high depressive symptoms did not have significantly higher mean levels of adjustment problems than youth with low problems, except in social competence.

Discussion

This study examined the development of CP, depression, and their comorbid presentation in a large sample of youth from 5th to 7th grade. Our objective was to identify problem patterns and gender differences in presentation over time, and investigate predictive relations to important adjustment problems in early adolescence. By investigating these relations from both continuous and categorical approaches, we were able to examine findings across the entire range of boys and girls, and for youth who demonstrated elevated risk for later problems (i.e., those with already elevated problems in 5th grade). As in other studies utilizing similar approaches (Capaldi, 1991, 1992; Miller-Johnson et al., 1998), we found moderate stability in rates and continuity of elevated co-occurring problems across the transition from late childhood to early adolescence, for both boys and girls. Youth with low problem scores in both CP and depressive symptoms tended to remain at low levels, while youth who were elevated on CP or depressive symptoms demonstrated more variability across time. In examining associations between early and later CP and depressive symptoms, we did not find support for the hypothesis that CP in late childhood would predict increases in depression in early adolescence, as Capaldi (1992) found with boys. Gender did not appear to explain the different results in these two samples. In terms of predicting early adolescent outcomes from earlier symptom patterns, both CP and depressive symptoms appeared to be associated with adjustment outcomes in early adolescence, and co-occurring problems were specifically associated with poor academic outcomes and low social competence. CP were more strongly associated with later problems than depressive symptoms across all domains, highlighting the wide-ranging and enduring negative effects of early emerging aggression, interpersonal conflict, and rule-breaking behavior on development. In general, while gender differences were noted in rates of problems in 5th and 7th grade, relations between symptomatology in late childhood and adolescent outcomes were not moderated by gender. Below, we discuss our findings regarding a) continuity and change in symptoms over this period, b) the predictive associations among CP and depression, and c) the predictive associations among early symptom patterns on indices of early adolescent outcomes (i.e., academic achievement, social competence, antisocial peers, and substance use). We address how symptomatology patterns related to gender, and place findings in developmental context as we discuss each set of hypotheses and results.

Continuity and change in CP and depressive symptom patterns during the transition to adolescence

We were particularly interested in examining how youth with elevated levels of CP and depressive symptoms in late childhood would fare across this important transition. We hypothesized that youth with high CP in late childhood would continue to exhibit significant symptom levels two years later, and depressive symptoms might be lower in late childhood, but would increase over time. We found moderate levels of stability in elevated problems, and stability tended to be highest within type of elevated problem. That is, in general, youth who were elevated in depressive symptoms tended to stay elevated (i.e., in the depressive group or by joining the co-occurring group by 7th grade) and those with CP continued to show high CP in 7th grade (i.e., remaining in CP and/or joining CO-OCCUR group).

The co-occurring problem group showed the highest rates and significant persistence over time. Already by 5th grade, approximately 12% of youth in the entire sample were demonstrating elevated problems in both domains. In examining trends in the data, one noteworthy pattern was that a substantial portion of youth moved from the high CP group in 5th grade to the CO-OCCUR group in 7th grade. These youth were primarily accounted for by boys and girls from the CP group developing high depressive symptoms over the two-year period. Youth in the co-occurring group also maintained the highest mean levels of both CP and depression at both time points, although they showed a decrease over time. Thus, youth with more serious levels of depressive and CP symptoms appear to experience co-occurrence (“a double whammy”), and this is evident by 5th grade. These youth generally continue to experience greater levels of both problems as they transition to adolescence. These findings confirm that the presentation of more serious depression or CP for youth by 7th grade is more often one of co-occurrence than either alone, and highlight the need to further understand the developmental underpinnings of comorbid problems prior to entering middle school.

Overall, a modest number of youth dropped in their level of problems from 5th to 7th grade. Only 11% of youth who were in one of the elevated symptomatology groups dropped in their levels of symptoms enough to be below the mean on CP and depressive symptoms over this same time period, indicating low levels of true desistance in problem behavior over these two years. A slightly larger but still modest percentage of youth (20%) demonstrated emergence of elevated problems in 7th grade (i.e., moving from the LOW or MED group to an elevated group), suggesting that the risk for serious depression or CP is present for most of the sample by 5th grade. The data suggest that early CP and early depressive symptomatology forecast persisting, although sometimes changing, problems in CP and depression into early adolescence.

Regarding gender differences, the well-established findings of higher rates of CP and co-occurring problems among boys and depressive symptoms among girls were replicated in this sample (Angold & Rutter, 1992; Compas et al., 1997; Fleming, Offord, & Boyle, 1989). We expected and found similar initial mean scores of depressive symptoms across gender. However, girls showed an increase in both mean rates and meeting criteria for elevated symptoms by 7th grade. Also as expected, rates of elevated CP were higher for boys than girls in 5th grade (4:1 ratio), and we found the expected smaller difference evident in 7th grade (2:1 ratio). Change in CP rates over time was due to a slight increase in girls and a decrease in boys. This finding fits with others indicating overall higher rates of problems in boys in late childhood and adolescence, but increasing rates of problems across multiple symptom domains in girls during adolescence (Loeber & Keenan, 1994). The developmental period under study here overlaps with significant transitions for youth, including moving from elementary to middle school, with concomitant changes in peer groups and activities. For girls between the ages of 11 to 13, rapidly occurring physical and emotional changes associated with puberty are in full swing, as opposed to boys who are typically beginning puberty. These changes may result in girls' increasing development of internalizing symptoms including self-esteem and body issues, mood lability, and associated CP including irritability and conflict with peers (Hoffman, Powlishta, & White, 2004).

Gender was associated with co-occurring problems in an interesting but complex manner. As expected, more boys demonstrated co-occurring problems as compared to girls (Bird et al., 1993; Costello et al., 1996). We thought that girls' rates would increase over time. This was not found. However, rates of CP are very low in preadolescent girls, naturally leading to lower rates of comorbidity. Perhaps the expected increasing pattern will be observed as these girls grow older (Loeber & Keenan, 1994; Zoccolillo, 1992). There is some evidence that girls may begin to engage in more serious aggression and delinquency after puberty, through involvement with deviant older boys and in later adolescence (Silverthorn & Frick, 1999). Interestingly, a modest but still considerable number of girls with co-occurrence were evident already at 5th grade, more so than those with CP alone. It may be that girls who develop early CP (earlier than 5th grade) are at higher risk for greater levels of and more varied psychopathology, as has been suggested by the gender paradox theory (Loeber & Keenan, 1994; Robins, 1986; Silverthorn & Frick, 1999). However, in our group-based results, girls with high CP did not demonstrate significantly more problems or higher mean scores than boys with high CP in 5th grade.

These results underscore the importance of early identification and prevention and intervention efforts with youth with elevated symptoms of depression or CP, prior to the transition to middle school. Several researchers have discussed how the early onset of these problems is associated with chronic and severe trajectories across later adolescence and into adulthood (Moffitt & Caspi, 2001), and have emphasized the value of implementing programs aimed at increasing behavioral and emotional competence in elementary school years in order to prevent the development or amplification of depression and CP (CPPRG, 2001a; Roesner & Eccles, 1998). The high stability of co-occurring problems for both genders, and the considerable percentage of youth with “medium” levels of problems who develop co-occurring problems by 7th grade (24.79%) underscores the need to assess for, and intervene with, both problems simultaneously when one problem is indicated. That is, interventions that combine components aimed at decreasing CP and those aimed at decreasing depressive symptoms are more likely to have wide-ranging positive effects (Gilham, Reivich, Jaycox, & Seligman, 1995; Weiss, Harris, Catron, & Han, 2003).

Predictive associations among late childhood and early adolescent CP and depressive symptoms

Based on existing research (Capaldi, 1992; Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Loeber & Keenan, 1994), we hypothesized that CP would predict the development of depressive symptoms more strongly than the reverse. This was not confirmed. CP in 5th grade did not predict depressive symptoms in 7th grade when controlling for 5th grade depression. Instead, the results reflected the moderate stability of each type of problem: Earlier CP was a significant predictor of later CP, and 5th grade depressive symptoms scores were significant predictors of later depressive symptoms, but not of CP. The enduring experience of specific symptoms was not surprising, but we were surprised that our results were not consistent with this part of the dual failure model (Capaldi, 1991). We expected to find that early CP led to increased problems in mood, as youth experience problems in social relationships and interference and poor performance in school in response to aversive, aggressive or antisocial behavior. While these results did not directly replicate Capaldi's findings (1992), it may be that in this more ethnically- and socioeconomically-diverse sample, the expected relations between CP developing into depressive symptoms still may be relevant, but at an earlier age than 5th grade. We were not able to assess the onset and progression of these problems prior to 5th grade. We investigated whether gender explained these differences across samples, but it did not—similar patterns of relations were demonstrated for boys and for girls. Alternatively, there may be other variables that moderate these relations that were not examined here, such as level of family conflict and poor family management (Capaldi, 1992; Kim et al., 2003) or social, cultural, ethnic, or community-based differences in the manifestation and experience of behavior problems (Achenbach et al., 1991a; Costello et al., 1996; Kessler et al., 1994), In addition, it may be that this sample was not large enough to identify significant differences, as there were some groups with relatively small numbers, especially among the girls. More research is needed to assess patterns of CP and depressive symptoms in relation to potential moderating influences in larger samples of diverse youth.

CP, depressive, and co-occurring problems and early adolescent adjustment

Depressive symptoms and CP were significant predictors of lower academic adjustment and social competence, and higher involvement with antisocial peers and substance use. Our findings generally confirmed our hypothesis that co-occurrence would result in the highest level of problems, and more varied problems, than other patterns. In group-based analyses, the expected step-down relationship was evidenced, such that CO-OCCUR group was associated with the worst adjustment outcomes, followed by CP, then DEP, and finally, LOW. In general, youth with comorbid symptomatology were little worse than those with CP alone, but significantly worse than youth with depressive symptoms only, suggesting that CP has wide-ranging effects on multiple domains of early adolescent outcomes (Capaldi, 1992; Hinshaw, 1992).

Both types of analyses suggested that CP had a stronger relationship with academic adjustment and social competence than did depressive symptoms, but also indicated that the combination of depression and CP led to greater severity in these domains. This lends partial support to one component of the dual failure model (Capaldi, 1991), which posits that early CP results in failures in academic and social domains, and the development of secondary symptoms, such as depression. In these analyses, gender differences emerged, indicating that boys demonstrated lower academic adjustment and lower social competence, regardless of CP or depressive symptoms. However, the interaction of CP and depressive symptomatology at 5th grade uniquely added to the prediction of academic and social problems, demonstrating that experiencing depressive symptoms mattered most for youth with low levels of CP Youth with low levels of both problems had more positive social skills and had higher achievement in school, but those youth with high CP demonstrated significantly lower social competence and academic adjustment regardless of depression (see Fig. 1). These results for predicting adjustment outcomes are virtually identical with Capaldi's (1992) findings for high-risk boys with other findings (Cohen, Gottlieb, Kershner, & Wehrspann, 1985; McConaughy, Achenbach, & Gent, 1988). Depressive symptoms during late childhood result in problems in academic and social adjustment in early adolescence, but do not contribute in these domains as strongly as CP.

Expected significant relations between elevated CP and antisocial peers and substance use were evidenced (Keenan, Loeber, Zhang, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Van Kammen, 1995; Moffitt, Caspi, Dickson, Silva, & Stanton, 1996). Moreover, the co-occurring group reported greater involvement with antisocial peers and substance use than the CP group, although the interaction of these problems did not uniquely predict mean outcomes once accounting for main effects. Interestingly, post-hoc investigation of mean scores by gender and group (exploratory investigation not reported in results) showed that girls in the CO-OCCUR group reported greater involvement with deviant peers than boys in the CO-OCCUR group. For the CP group, girls' mean scores for antisocial peers were slightly higher than boys, but more similar to one another. This would suggest that it is the addition of depressive symptoms for co-occurring girls that result in greater involvement with antisocial peers, rather than more severe CP. This is consistent with the idea that depressed girls may be more likely to associate with youth, especially males, who engage in delinquent behavior (Capaldi & Crosby, 1997). As girls enter adolescence, their involvement with older antisocial boys, perhaps as romantic partners, may increase (Moffitt & Caspi, 2001). These close ties may lead to increased CP and depressive symptoms as these girls may experience rejection from prosocial peers and increasing problems due to consequences from antisocial behavior (Silverthorn & Frick, 1999).

Study limitations

Although this study improved on previous research by using a diverse sample, there were limitations to note. First, sample size and group criteria may have restricted our ability to demonstrate sizeable symptom group differences. That is, we decided to use .5 SD as the cut-off because it allowed for larger groups who demonstrate elevation. However, if differences exist only among the most extreme groups, the lower cut-off may not have captured this (Hinshaw, Lahey, & Hart, 1993). Alternatively, if CP and depressive symptoms are best conceptualized as dimensionally distributed (Hankin et al., 2004; Ruscio & Ruscio, 2000), creating groups based on relatively arbitrary cut-offs may also skew results. To offset this limitation, we contrasted categorical and continuous analytical strategies, to demonstrate which significant relations were demonstrated across the sample (e.g., CP and depressive symptoms predicted social adjustment across the sample) and which significant results were carried by differences in more extreme groups (e.g., CP levels in the co-occurring and CP groups appeared to relate to involvement with antisocial peers and substance use more than depressive levels). Second, we decided to combine data from different informants so as to minimize rater bias and to capture behavior experienced and observed in multiple contexts. Other research has used single informants, arguing that the lack of convergence between informants results in potentially misleading associations (Offord et al., 1996). It is possible that different results would emerge if symptom patterns were investigated separately by informant. Third, the age of the sample may have decreased the likelihood of finding certain associations. We assumed that testing predictive relations in this developmental period over which several stressful transitions occur might have resulted in significant gender-related shifts in symptom patterns. However, assessing depression and outcomes such as substance use may prove more critical in later adolescence when base rates are higher, especially for girls. Finally, limitations with using multiply imputed data exist, including the inability to use multiply-imputed data for significance testing for the continuity and change analyses.

In general, this study suggests that CP and depressive symptomatology appear to lead to maladaptive outcomes in part because they interfere with the normal acquisition of developmentally appropriate skills in social, cognitive, and psychological domains (Sameroff, 1995; Sroufe & Rutter, 1984). Understanding the relative predictive power of CP, depressive symptoms, and their co-occurring presentation in relation to various adjustment outcomes (i.e., determing who is at greater risk) will help plan more effective and targeted secondary prevention and intervention strategies. From the present results, it is clear that early depressive symptoms and CP should both be targeted for treatment, before the transition to middle school and early adolescence, in order to have the greatest impact and to keep one condition from developing into two or more co-occurring conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grants RI8MH48043, R18MH50951, and Rl8MH50953. The Center for Substance Use Prevention and the National Institute on Drug Abuse have also provided support for Fast Track through a memorandum of agreement with the NIMH. This work was also supported in part by the Department of Education Grant S184U30002, NIMH Grants K05MH00797 and K05MH01027, and NIDA Grant R01DA016903-03. We are grateful for the close collaboration of the Durham Public Schools, the Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools, the Bellefonte Area Schools, the Tyrone Area Schools, the Mifflin County Schools, the Highline Public Schools, and the Seattle Public Schools. We greatle appreciate the hard work and dedication of the many staff members who implemented the project, collected the evaluation data, and assisted with data management and analyses. The design and analyses for the current study were originally based upon the dissertation project of me second author.

Footnotes

Multiple imputation (MI) is an appropriate method for treating missing data if variables and correlates of the dependent variable that are thought to relate to the causes of missing data are included in the imputation model. First, missingness patterns were examined to insure that data met missing-at-random assumptions. Thirty-two participants were missing all data (7% of sample) and these participants were excluded from any analyses. Of the 431 youth with some data, the percentage of missing data across measures ranged from 6% (25 youth were missing the parent reported Child Behavior Checklist at 5th grade) to 16% (70 youth were missing the Self-Report of Close Friends measure in 7th grade). MI was deemed appropriate for this dataset, as missing data numbered less than 30% and demonstrated an adequate random pattern of missingness, and means and standard deviations of imputed data almost exactly matched unimputed means (Schafer, 1997). The data set with which the imputation was conducted consisted of 35 variables including key demographic variables (e.g., gender, ethnicity, site, SES, three perceived neighborhood context variables) and all indicators by informant (e.g., parent-reported CP scores at 5th grade). Interaction terms were created after imputation.