Abstract

Background

Few bowel preparation rating scales have been validated. Most were intended for comparing oral purgatives, failing to account for washing/suctioning by the endoscopist. This limits their utility in studies of colonoscopy outcomes such as polyp detection rates.

Objective

To develop a valid and reliable scale for use in colonoscopy outcomes research.

Setting

Academic medical center.

Methods

We developed the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS), a 10-point scale assessing bowel preparation after all cleansing maneuvers are completed by the endoscopist. We assessed inter- and intra-observer reliability using video footage of colonoscopies viewed on two separate occasions by 22 clinicians. We then applied the BBPS prospectively during screening colonoscopies, comparing BBPS scores with clinically-meaningful outcomes including polyp detection rates and procedure times.

Results

The intra-class correlation coefficient (a measure of inter-observer reliability) for BBPS scores was 0.74. The weighted Kappa (a measure of intra-observer reliability) for scores was 0.77 (95% CI 0.66-0.87). During 633 screening colonoscopies, the mean (SD) BBPS score was 6.0 (1.6). Higher BBPS scores (≥5 versus <5) were associated with a higher polyp detection rate (40% vs 24%; p<0.02). BBPS scores were inversely correlated with colonoscope insertion (r = −0.16; p<0.003) and withdrawal (r = −0.23; p<0.001) times.

Limitations

Single-center study.

Conclusions

The BBPS is a valid and reliable measure of bowel preparation. It may be well-suited to colonoscopy outcomes research because it reflects the colon's cleanliness during the inspection phase of the procedure.

Keywords: colonoscopy, bowel preparation, outcomes research

INTRODUCTION

The diagnostic accuracy of colonoscopy requires thorough visualization of the colonic mucosa, making bowel preparation a vital element of the procedure. Failure to adequately cleanse the bowel for colonoscopy can lead to missed lesions, prolonged procedure duration, and repeat procedures at earlier intervals.1-4 The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy suggested that every colonoscopy report should include an assessment of the quality of bowel preparation. They proposed the use of terms such as “excellent,” “good,” “fair,” and “poor,” but admitted that these terms lack standardized definitions.5

It is unclear if endoscopists apply these terms to the quality of preparation encountered upon insertion of the colonoscope when the bowel is not adequately distended, or during withdrawal, after cleansing maneuvers such as washing and suctioning of fluid have been completed. This distinction is important as the former is an assessment of the method of colonic preparation, while the latter is an assessment of the likelihood for missed lesions, a more clinically relevant measure. Furthermore, in any individual patient, the quality of bowel preparation may vary between colonic segments. It might prove useful to have a bowel preparation rating scale that is sensitive to such differences in order to better define the likelihood of a missed polyp and/or appropriate screening and surveillance intervals. We sought to develop a novel bowel preparation rating scale specifically for application during withdrawal of the colonoscope, after all cleansing maneuvers are completed. Such a scale could be used in the clinical and research settings, controlling for bowel preparation in studies assessing rates of missed lesions, and for establishing guidelines on appropriate screening and surveillance intervals inclusive of bowel preparation quality.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Boston University Medical Center.

Development of the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale

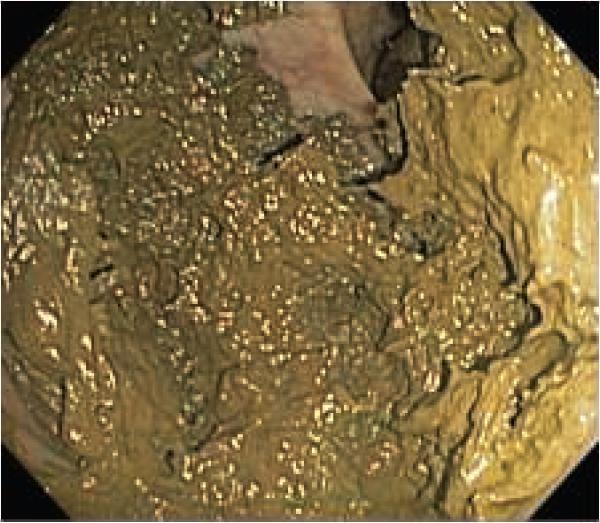

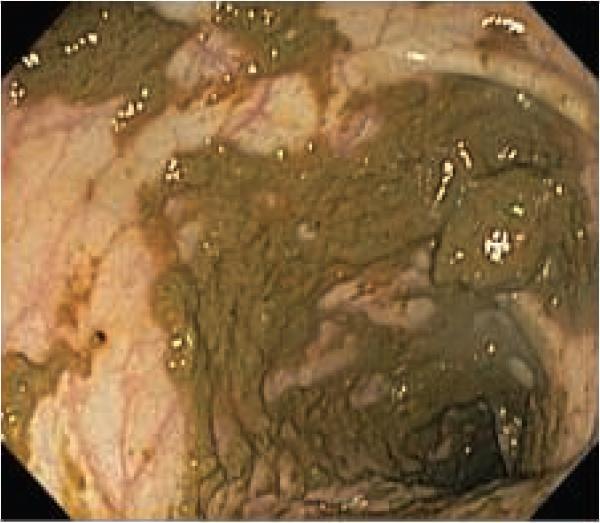

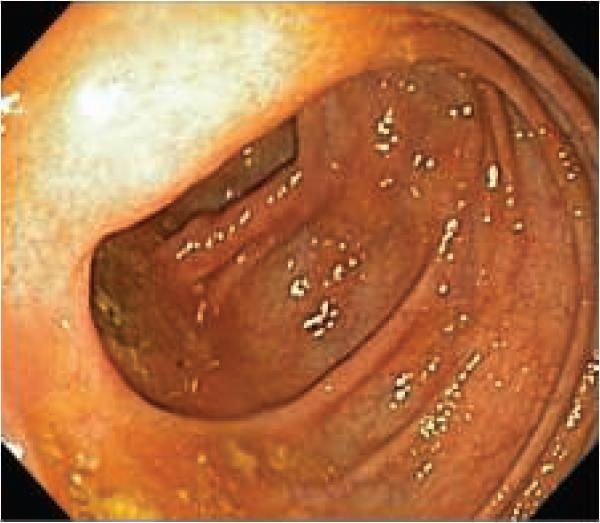

The Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS; suggested pronunciation- “bee-bops”) was developed to limit inter-observer variability in the rating of bowel preparation quality, while preserving the ability to distinguish various degrees of bowel cleanliness. Subjective terms such as “excellent,” “good,” “fair,” “poor,” and “unsatisfactory” are replaced by a four-point scoring system applied to each of the three broad regions of the colon: the right colon (including the cecum and ascending colon), the transverse colon (including the hepatic and splenic flexures), and the left colon (including the descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum). The points are assigned as follows (Figure 1):

0 = Unprepared colon segment with mucosa not seen due to solid stool that cannot be cleared.

1 = Portion of mucosa of the colon segment seen, but other areas of the colon segment not well seen due to staining, residual stool and/or opaque liquid.

2 = Minor amount of residual staining, small fragments of stool and/or opaque liquid, but mucosa of colon segment seen well.

3 = Entire mucosa of colon segment seen well with no residual staining, small fragments of stool or opaque liquid. The wording of the scale was finalized after incorporating feedback from three colleagues experienced in colonoscopy.

Figure 1.

The Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS). A, segment score 0: unprepared colon segment with mucosa not seen due to solid stool that cannot be cleared. B, segment score 1: portion of mucosa of the colon segment seen, but other areas of the colon segment not well seen due to staining, residual stool and/or opaque liquid. C, segment score 2: minor amount of residual staining, small fragments of stool and/or opaque liquid, but mucosa of colon segment seen well. D, segment score 3: entire mucosa of colon segment seen well with no residual staining, small fragments of stool and/or opaque liquid

Each region of the colon receives a “segment score” from 0 to 3 and these segment scores are summed for a total BBPS score ranging from 0 to 9. Therefore, the maximum BBPS score for a perfectly clean colon without any residual liquid is 9 and the minimum BBPS score for an unprepared colon is 0. If an endoscopist aborts a procedure due to an inadequate preparation, then any non-visualized proximal segments are assigned a score of 0. Representative endoscopic images were selected to aid in comprehension of the points making up the segment scores.

To enhance comprehension of the BBPS, a fifteen minute training DVD was created and viewed by members of our gastroenterology division. The DVD contained narrated video footage illustrating each point of the BBPS. It also illustrated how a segment score may be improved through maneuvers such as washing and fluid aspiration. Next, two truncated demonstration colonoscopies (only the withdrawal portion) were included to show how the BBPS would be applied. These demonstration colonoscopies exhibited total BBPS scores considered to be 4 and 5, respectively. Copies of the BBPS DVD may be obtained from the corresponding author.

Assessment of Reliability

The training DVD also contained three truncated testing colonoscopies, with images differing from those in the demonstration colonoscopies. The testing colonoscopies had bowel preparation qualities considered to represent total BBPS scores 4, 5, and 6, respectively. To assess reliability, we asked members of our Gastroenterology division to rate the quality of bowel preparation in each testing colonoscopy using the BBPS. Participants viewed the testing colonoscopies on two occasions, at least one month apart. For the second viewing, the order of the testing colonoscopies was changed to limit the possibility that someone might remember the scores they had provided during the first viewing. The scores from the two viewings were used to calculate intra-observer and inter-observer reliability.

Assessment of Validity

After all endoscopists had viewed the training DVD, the BBPS was applied prospectively in 633 screening colonoscopies at our institution. After each screening colonoscopy, the endoscopist was asked to record the quality of bowel preparation using both the categorical system used historically at our medical center (“excellent”, “good”, “fair”, “poor”, or “unsatisfactory”) and the BBPS score. Endoscopists also recorded the location and size of all polyps found during the examination, as well as whether they were recommending a repeat colonoscopy specifically because the bowel preparation was deemed inadequate. Endoscopy nurses recorded colonoscope insertion and withdrawal times.

To measure the construct validity of the BBPS, we assessed four factors: 1) comparison with another, albeit non-standardized, method of assessing bowel preparation (i.e. excellent, good, fair, poor, unsatisfactory); 2) the association between BBPS score and a perception of inadequate bowel preparation; 3) the association between BBPS score and polyp detection rate; and 4) the association between BBPS score and colonoscope insertion and withdrawal times.

Statistical analysis

To assess inter-observer reliability, we calculated the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) among scores applied after viewing the testing colonoscopies. Since, for each testing case, two BBPS scores were available from each clinician, we randomly selected one of the two scores for this calculation. We repeated this procedure 1000 times to determine the potential distribution and a 95% predictive interval for the ICC of a single reading.6 To assess intra-observer reliability, we calculated weighted kappa measures.7-9 We calculated the mean total BBPS score for each possible categorical assessment- “excellent”, “good”, “fair”, “poor”, and “unsatisfactory”, and obtained a p value for the trend in means using linear regression. We determined the polyp detection rate for each BBPS score, as well as for a dichotomized score (<5 and ≥5). This dichotomized point was chosen a priori based on a clinical assessment that the degree of cleanliness causing a score <5 would likely be considered inadequate. Associations between BBPS scores and polyp detection rates as well as recommendations for repeat procedures were calculated using chi-square tests. Colonoscope insertion and withdrawal times were correlated with BBPS scores using Pearson's correlation coefficient. For colonoscope withdrawal times, we excluded cases in which polyps were found. All calculations were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and two-sided p values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

The BBPS training and testing DVD was viewed by 22 members of our gastroenterology section, including 13 full-time faculty, 8 fellows and one physician assistant with greater than 10 years experience in performing flexible sigmoidoscopy. Individuals viewed the DVD twice with a mean (SD) of 10 (3) weeks between viewings. The ICC for inter-observer agreement of a single reading in total BBPS scores was 0.74 (95% predictive interval 0.67-0.80). The weighted kappa value for intra-observer agreement in total BBPS scores was 0.77 (95% CI 0.66-0.87). This degree of agreement is considered to be substantial.10 The ICCs and weighted kappa values stratified by experience (i.e. attendings vs. fellows), are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Reliability of the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale

| Inter-observer Reliability | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

All clinicians (n=22) |

Attendings* (n=14) |

Fellows (n=8) |

|

|

Intra-class correlation coefficient (95% predictive interval) |

0.74 (0.67-0.80) |

0.74 (0.65-0.85) |

0.83 (0.77-0.91) |

| Intra-observer (Test-Retest) Reliability | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

All clinicians (n=21)† |

Attendings* (n=13) |

Fellows (n=8) |

|

|

Weighted kappa (95% confidence interval) |

0.77 (0.66 - 0.87) |

0.76 (0.60 - 0.92) |

0.85 (0.76 - 0.94) |

Includes one physician assistant with over 10 years of experience performing flexible sigmoidoscopy.

One physician was unable to view the DVD twice.

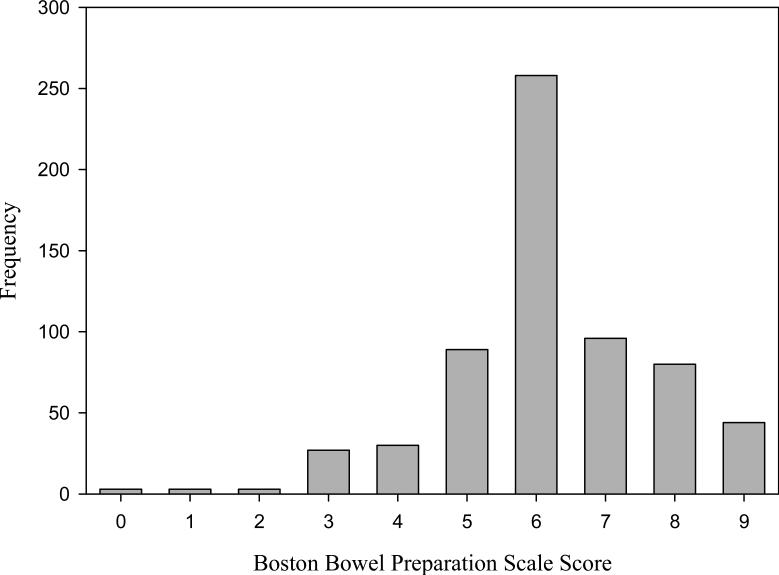

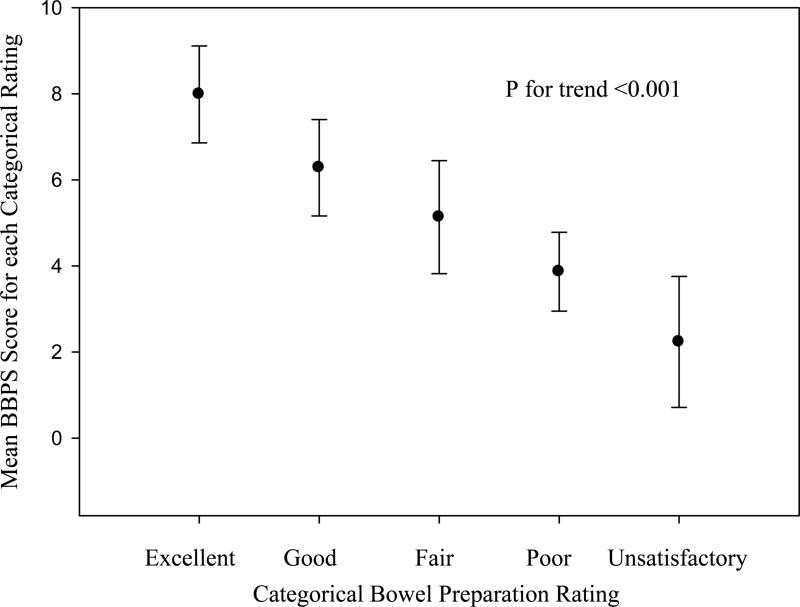

When the BBPS was used prospectively during 633 screening colonoscopies, we observed an approximate bell-shaped distribution of scores (Figure 2). The mean (SD) BBPS score was 6.2 (1.5) and the median score was 6.0 (range 0.0-9.0; IQR 6.0-7.0). When considering the categorical bowel preparation ratings used during those colonoscopies (excellent, good, fair, poor, and unsatisfactory), we noted a significant trend in decreasing mean BBPS score assigned in each category (p for trend <0.001; Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Distribution of Boston Bowel Preparation Scale scores applied during 633 screening colonoscopies. The distribution approximates a bell-shaped curve with a median score of 6 and an interquartile range of 6-7.

Figure 3.

We determined the mean (SD) Boston Bowel Preparation Scale score (y-axis) assigned for each categorical bowel preparation rating (x-axis) observed during 633 screening colonoscopies. The decreasing trend in scores across decreasing categorical preparation qualities was statistically significant (p<0.001).

Among the 633 patients who underwent colonoscopy, 243 had at least one polyp found (38%). The polyp detection rate for each BBPS score was: 0 = 0%, 1 = 0%, 2 = 33%, 3 = 19%, 4 = 33%, 5 = 43%, 6 = 45%, 7 = 31%, 8 = 35%, and 9 = 36%. The polyp detection rate was 40% for patients with a BBPS score ≥5 compared to 24% for patients with a BBPS score <5 (p<0.02). The endoscopist recommended repeating the procedure because of inadequate bowel preparation among 2% of cases with a BBPS score ≥5, compared to 73% among cases with a BBPS score <5 (p<0.001). Total BBPS scores were inversely correlated with both colonoscope insertion (r = −0.16; p<0.003) and withdrawal (r = −0.23; p<0.001) times.

DISCUSSION

We have developed a valid and reliable bowel preparation rating scale that can be easily taught with a brief instructional DVD. The BBPS demonstrated good intra- and inter-observer reliability among 22 physicians, including both fellows and attendings. Prospective use of the BBPS during screening colonoscopy showed significant associations with clinical outcomes such as polyp detection rates, recommendations for repeat procedures, and colonoscope insertion and withdrawal times.

Many previously published bowel rating scales were designed specifically to compare the efficacy of two or more bowel preparation methods.11-15 As such, they measure the degree of bowel cleanliness encountered by endoscopists during initial inspection of the colon. The BBPS distinguishes itself from these scales by being applied after the endoscopist has performed any additional cleansing maneuvers, reflecting the actual practice of colonoscopy. Therefore, the BBPS may be better suited to colonoscopy outcomes research, such as studies aimed at defining appropriate screening and surveillance intervals that account for bowel preparation quality. Furthermore, the BBPS can also be used when comparing bowel preparations. In such instances, the study outcome would represent the clinical effectiveness of the preparations tested (e.g. “Did Mrs. Jones have better colonoscopic visualization after using preparation A versus B?”) instead of the efficacy of the preparations (i.e. Does one preparation clean better than the other?). This is an important distinction, because without accounting for an endoscopist's ability to improve preparation quality with cleansing maneuvers during colonoscopy, the clinical impact of one preparation versus another remains unknown.

Many published bowel preparation scales rely on a global assessment of bowel cleanliness, failing to account for differences in individual colon segments. During colonoscopy, however, one may find a generally excellent preparation, except for one region that is poorly prepared. The BBPS recognizes that the colon is not uniformly prepared for colonoscopy, allowing the assignment of various scores to each of three broad segments of the colon. By accounting for such subtleties, the BBPS may help better define risks for missed pathology, although this remains to be demonstrated. Other published bowel preparation scales rely on factors prone to inter-observer variation such as quantitative estimates of residual stool or liquid, the percentage of visualized mucosa, or the likelihood of missing certain sized lesions. The BBPS relies on more generalized assessments, using segment scores to permit tailoring to individual patients.

Few of the previously published bowel preparation rating scales have been formally validated. The Aronchick scale16 was evaluated by five gastroenterologists who reviewed 80 videotaped colonoscopies.17 Inter-observer reliability was measured using ICCs that ranged from 0.31 for “distal colon to hepatic flexure” to 0.76 for the cecum. A Friedman's Chi-squared test was also used to test the likelihood that samples of given scores were drawn from the same population. Intra-observer reliability was not reported, nor was there formal correlation with other colonoscopy outcomes such as polyp detection rates.

Another validated scale, the Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale, uses three colonic segment scores (in this case 0-4) that are summed as part of a total score.18 However, there is an additional global fluid quantity rating (0-2), requiring subjective estimation of residual liquid. The Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale was validated only by comparison with the Aronchick scale, and not by correlation with colonoscopy outcomes. Reliability testing was limited to two observers, a staff gastroenterologist and a research fellow, who observed 97 colonoscopies. Inter-observer reliability was tested using Pearson correlation coefficients, linear regression analyses, and a kappa ICC. This scale performed well, albeit between only two investigators, with a kappa ICC of 0.94 (95% CI 0.91-0.96), but intra-observer reliability was not assessed.

We believe the BBPS has now been reasonably validated for general use in research studies. However, our reliability testing was based on three truncated colonoscopy video clips reflecting BBPS scores in the mid-scale range (considered to be 4, 5, and 6), rather than full colonoscopies reflecting all nine BBPS scores. We chose to test the reliability in the mid-scale range, postulating this would be the region with the broadest inter-observer variability. Moreover, we postulated a priori that the clinically-relevant cut-point regarding a preparation's overall adequacy would likely fall in this range. In addition, there is likely very good agreement between gastroenterologists assessing excellent and poor preparations, but this will need to be proven in future studies.

The strengths of our study include the large number of individuals who participated in reliability testing and the large number of cases and clinically meaningful outcomes used to prospectively validate the scale. However, our study was limited to a single institution, potentially limiting the generalizability of our results. It is reassuring that we found similar results among fellows, attendings, and a GI physician assistant, suggesting that the BBPS can be used by clinicians with various levels of experience. Furthermore, the BBPS training DVD is brief (15 minutes, including testing videos) making dissemination of the scale, and standardization of its use, straightforward. Unfortunately, we are unable to comment on the utility of the BBPS during other procedures that require colonic catharsis, such as CT colonography. It is not clear that the BBPS can be used effectively in non-colonoscopy bowel imaging, particularly because the distinction between segment scores 2 and 3 is likely impossible without direct visualization of the bowel. Furthermore, we did not measure the reliability of the BPPS in non-colonoscopy settings.

In summary, the BBPS is a valid and reliable instrument for rating the quality of bowel preparation during colonoscopy. Investigators may find it useful for colonoscopy-oriented research requiring a method of controlling for various degrees of bowel preparation. Future studies should assess the validity of the BBPS at other institutions, verify its reliability across the full spectrum of scores, and examine the relationship between individual segment scores and polyp detection rates.

Acknowledgments

Grant information: Supported by an ASGE/TAP Endoscopic Research Award (Dr. Jacobson) and National Institute's of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases award K08-DK070706 (Dr. Jacobson).

REFERENCES

- 1.Burke CA, Church JM. Enhancing the quality of colonoscopy: the importance of bowel purgatives. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:565–73. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.03.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:378–84. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02776-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P. Impact of colonoscopy preparation quality on detection of suspected colonic neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:76–9. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas-Gibson S, Rogers P, Cooper S, et al. Judgement of the quality of bowel preparation at screening flexible sigmoidoscopy is associated with variability in adenoma detection rates. Endoscopy. 2006;38:456–60. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:873–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnhart H, Song S, Harber M. Assessing intra, inter and total agreement with replicated readings. Statist Med. 2005;24:1371–1384. doi: 10.1002/sim.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleiss J, Cohen J. The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. Edu Psychol Meas. 1973;33:613–619. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spitzer R, Cohen J, Fleiss J, Endicott J. Quantification of agreement in psychiatry diagnosis: A new approach. Arch Gen Psych. 1967;17:83–87. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1967.01730250085012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landis J, Koch G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Afridi S, Barthel J, King P, JJ P, Marshall J. Prospective, randomized tiral comparing a new sodium phosphate-bisacodyl regimen with conventional PEGES lavage for outpatient colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:485–489. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)80008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berkelhammer C, Ekambaram A, Silva R. Low-volume oral colonoscopy bowel preparation: sodium phosphate and magnesium citrate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:89–94. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.125361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarkston W, Tsen T, Dies D, Schratz C, Vaswani S, Bjerregaard P. Oral sodium phosphate versus sulfate-free polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution in outpatient preparation for colonoscopy: a prospective comparison. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:42–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golub RW, Kerner BA, Wise WE, Jr., et al. Colonoscopic bowel preparations--which one? A blinded, prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:594–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02054117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma VK, Steinberg EN, Vasudeva R, Howden CW. Randomized, controlled study of pretreatment with magnesium citrate on the quality of colonoscopy preparation with polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:541–3. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aronchick C, Lipshutz W, Wright S, DuFrayne F, Bergman G. A novel tableted purgative for colonoscopic preparation: efficacy and safety comparisons with Colyte and Fleet phophosoda. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:346–352. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aronchick C, Lipshutz W, Wright S, DuFrayne F, Bergman G. Validation of an instrument to assess colon cleansing. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2667. (AB360)[abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rostom A, Jolicoeur E. Validation of a new scale for the assessment of bowel preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:482–6. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02875-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]