Abstract

Drugs exist that show long-lasting inhibition of embryogenesis and microfilaria production or macrofilaricidal activity against Onchocerca volvulus. Therefore, the patients have to be followed-up for several years. Clinical drug trials have to be performed in areas with ongoing transmission to assess the efficacy on younger worms. In addition, future vaccine trials may also require demonstrating efficacy against establishment of new worms. For the evaluation of the efficacy, it is necessary to differentiate between older worms, which were exposed to the drug, and younger worms newly acquired after drug treatment or vaccination. Here, we describe criteria for the differentiation between young and old filariae based on histological studies of worms with a known age from travellers, or from children, or patients living in areas with interrupted transmission in Burkina Faso, Ghana or Uganda. Older worms were larger and presented degenerated tissues. Gomori's iron stain showed that the worms accumulated more iron with increasing age, first in the gut and later in other organs. Using an antibody against O. volvulus lysosomal aspartic protease, the gut of young worms was stained only weakly; whereas, it was stronger labelled in older worms, accompanied by additional staining of hypodermis and epithelia. Using morphological and immunohistological criteria, it was possible to differentiate young (1–3 years old) from older females and to identify young males.

Introduction

Onchocerciasis is still a public health problem in tropical Africa, and the development of better drugs or a vaccine is still needed (Boussinesq 2008). When we began to study the effects of anthelmintic drugs and vector control on Onchocerca volvulus, it became obvious that we had to estimate the age of the filariae to differentiate between worms that had been present during the treatment and those newly acquired between treatment and examination of extirpated O. volvulus months or years later. Therefore, we had to find criteria to estimate the worm age for the identification of young newly acquired worms. We included this aspect during further studies. The results for the age estimation based on the worm morphology had been summarised for histology by Büttner et al. (1988), for electron microscopy by Franz (1988), and for isolated worms using the collagenase digestion technique of the human nodule tissue by Schulz-Key (1988). We observed during these studies in Liberia, 19 male and 25 female immature worms among 6,889 filariae (Albiez et al. 1984), and an immature worm was later described in detail by Duke (1991). The presence or absence of immune cells in the nodule can also support the recognition of young worms (Wildenburg et al. 1996, 1998).

Meanwhile, we have collected more data. Because the estimation of the age by morphological criteria alone is difficult for less experienced examiners, we have included the deposition of iron in the filarial tissues using histochemistry (Wildenburg and Henkle-Dührsen 1999; Jolodar et al. 2004). Further, we studied by immunohistology the uptake of degenerated material by lysosomes positive for O. volvulus aspartic protease (APR; Jolodar et al. 2004) and the presence of Wolbachia endobacteria after doxycycline treatment (Hoerauf et al. 2003, 2008, 2009). Here, we summarise the morphological criteria and describe in more details the differentiation between young and old O. volvulus filariae based on iron staining and labelling of APR. This study provides criteria to identify newly acquired worms in future drug trials.

Patients, materials and methods

Patients and onchocercomas

Our estimates of the worm age are based on the analyses of worms from children (Büttner and Weiss 1984; Büttner et al. 1988), patients who had stayed only a short time in an endemic area and had been nodulectomised for a known number of years later, re-nodulectomies of patients a few years after all palpable nodules had been excised (Albiez 1985), old worms after varying periods of vector control and ivermectin mass treatment. Onchocercomas from patients in Liberia, south western Burkina Faso, northern Ghana and western Uganda were included from the material of previous studies (Büttner et al. 1983, 1988, 1990; Fischer et al. 1993; Ndyomugyenyi et al. 2004; for vector control see Garms et al. 2009). The nodules had been surgically removed from the patients using local anaesthesia and aseptic conditions. Also included were onchocercomas from travellers that had been sent for diagnosis to the Bernhard Nocht Institute.

Histology and immunohistology

The selected onchocercomas were fixed in 70–80% ethanol or 4% phosphate-buffered formaldehyde solution and embedded in paraffin using standard methods. Haematoxylin-eosin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was used for all nodules; Movat, van Gieson and azan staining were applied for selected nodules. For the detection of iron in the filarial tissues, Gomori's iron method was applied for all selected nodules, using acid potassium ferrocyanide solution and nuclear fast red as counter stain (Luna 1968; Wildenburg and Henkle-Dührsen 1999). For immunohistology, the alkaline phosphatase-anti-alkaline phosphatase technique was applied according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (DakoCytomation, Hamburg, Germany). An antiserum raised against APR in a rabbit (Jolodar et al. 2004) had been used as primary antibody (diluted 1:1000–1:4000) in previous studies to assess the vitality of the filariae. It was now used for further nodules to estimate the worm age. As secondary antibody mouse anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (clone MR12/53, DakoCytomation) was applied. Fast Red TR salt (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) served as chromogen and haematoxylin (Merck) as counter stain. In several studies, antibodies were used against Yersinia enterocolitica heat shock protein 60 (hsp60; Pfarr et al. 2008; supplied by Prof. IB Autenrieth, Tübingen) and Dirofilaria immitis Wolbachia surface protein (WSP; supplied by Prof. Claudio Bandi, Milano, Italy).

Results

Morphological characteristics of filarial age

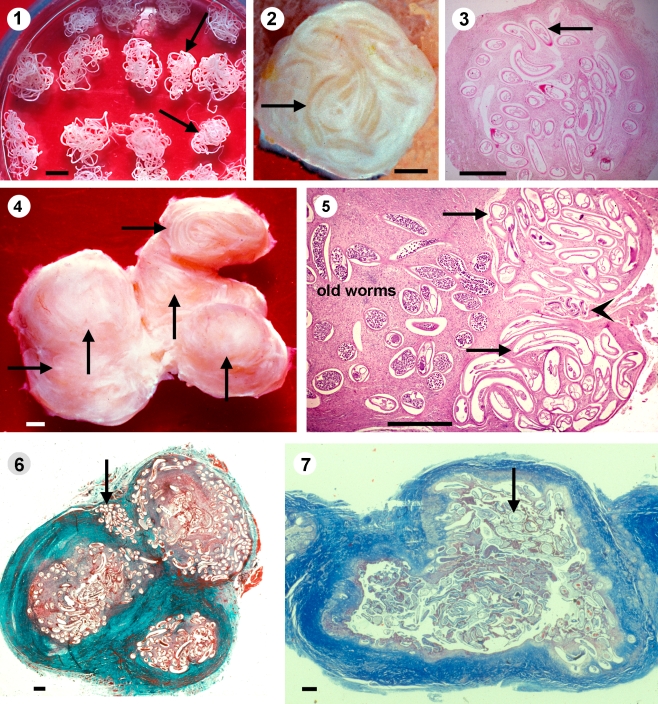

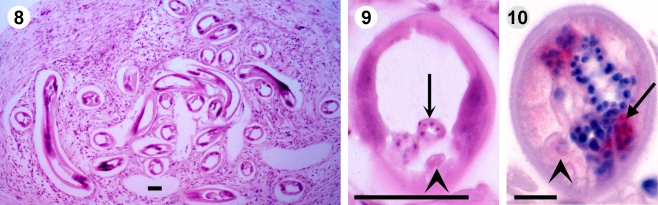

The morphological characteristics of young and old female worms are summarised in Table 1. In principle, these or similar criteria also apply for males. Only a few additional criteria regarding the localisation of young worms in the nodule are shown in Fig. 1 (2–7). The young worms were smaller (Fig. 1 (1)), indicated by a smaller diameter in histological sections (Specht et al. 2009). Especially during the 1–3 years of prepatency (WHO 1987), immature and young nulliparous worms lived in tiny nodules (Fig. 1 (2, 3)), as seen in nodules of young children. Such small onchocercomas can easily be missed. In chronic infections, new female worms were usually attached to an already existing nodule as a satellite (Fig. 1 (4)) or at the edge of the nodule. They were separated from the older worms by connective tissue (Fig. 1 (5, 6)). The same was applied for immature and other young males (Fig. 1 (5)). The localisation in a separate compartment supported the diagnosis of young worms. As long as the worms did not produce microfilariae (mf), the cellular immune reactions were sparse (Fig. 1 (5, 6); Wildenburg et al. 1996; 1998). Young females were not covered by a crust and hence not attacked by numerous neutrophils and macrophages (Figs. 1 (3, 5) and 2 (8)). Immature worms did not yet produce oocytes or spermatocytes (Fig. 2 (8–10)) and they contained only a small number of Wolbachia (Fig. 2 (10)).

Table 1.

Morphological characteristics of young and old female O. volvulus filariae

| Organ or tissue | Young worms, a few months to 4 years old | Old worms, probably more than 5 years old |

|---|---|---|

| Size of the worm | Thin, small diameter, short | Thick, larger diameter, long |

| Surface coat of female | Absent | Often present |

| Cuticle | Thin, regular, Basal layer well demarcated | Thick, basal protuberances |

| Cuticular ridges | Prominent, regular | Flat or not distinct |

| Hypodermis | Light | Dense, vacuoles, inclusion bodies, many lysosomes |

| Body wall muscles at midbody | Fibrillar portion well developed | Reduction of fibrillar portion, vacuoles |

| Intestine | Light, none or few iron granules, nuclei well visible | Dark, protrusions of inner layer of lamina, iron granules |

| Uterus lumen | Filled with intact oocytes or oocytes and embryos | Filled, often degenerated embryos, in very old worms often empty |

| Uterus epithelium | Light | Often darker, lysosomes |

| Uterus muscle cells | Flat, no brown pigment | Prominent, often brown pigment |

| Oocytes | None in immature worms, many in nulliparous and fecund worms | Reduced numbers in many worms that are not productive |

| Embryos | All stages of embryos in productive worms | Increased numbers of degenerated embryos and mf |

| Basal laminas of organs | Thin, regular | Thicker, often protrusions |

| Calcifications in the organs | None | May be present |

| Pleomorphic neoplasms | None | Present in 2–4% of untreated worms |

Fig. 1.

1 Young female O. volvulus (arrows) are smaller than older worms. Collagenase digestion technique. Scale bar = 1 mm. 2–3 Especially in children are young worms (arrows) often alone in tiny nodules with a diameter of 2–4 mm, covered only by a thin layer of connective tissue and the gut contains no or only sparse iron (3). Iron stain, scale bar = 1 mm. 4–5 In adult patients are the young worms (arrows) usually attached to a nodule with older filariae. The histology shows two young nulliparous worms (arrows), between them, an immature male (arrowhead) and several older productive worms. A thin outer layer covers the young worms and between the worm sections remains sparse host tissue. 4 Scale bar = 1 mm, 5 HE, scale bar = 200 µm. 6 A large nodule with three separated portions with older filariae and between them a young female worm (arrow). Van Gieson staining, scale bar = 1 mm. 7 A large nodule with a thick outer wall and a cyst that contains only old and dead worms (arrow). Azan staining, scale bar = 1 mm

Fig. 2.

8–9 An immature female O. volvulus produces not yet oocytes (arrows) and the gut contains no pigment (arrowhead). Young worms from a 4-year-old child in Liberia. HE, scale bar = 50 µm. 10 This immature worm without oocytes and a light gut (arrowhead) from an untreated patient contains Wolbachia (arrow) in the hypodermis, that are red labelled by anti-hsp60 serum. Scale bar = 10 µm

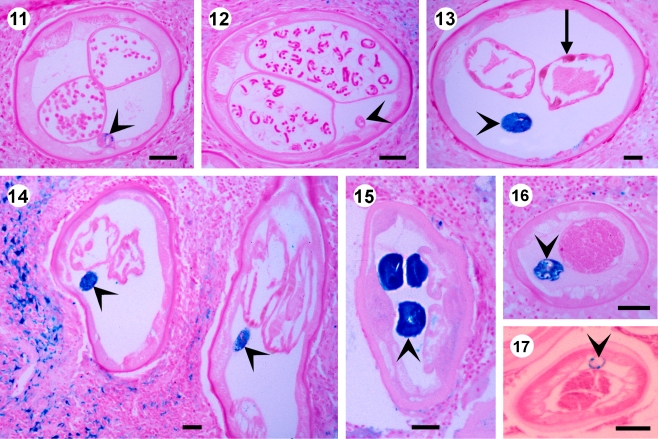

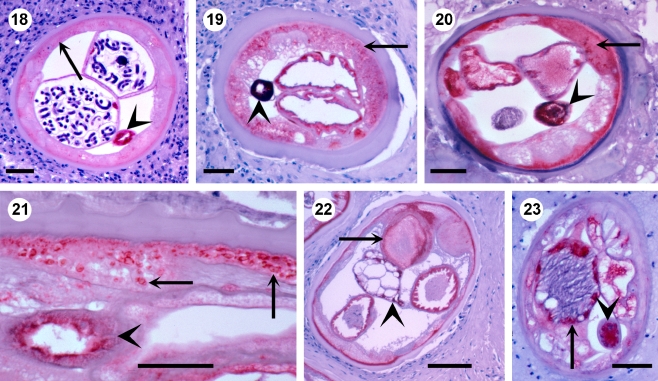

Young nulliparous females less than 1–3 years old, nodulectomised from a 4-year-old child, harboured numerous normal oocytes (Fig. 3 (11); Hoerauf et al. 2008). In contrast, older nulliparous female worms contained normal plus degenerated oocytes, but no degenerated remnant mf, since they had not been inseminated. For these worms, additional criteria had to be considered, such as the amount of iron in the gut. Female worms older than 12 months that had been inseminated, showed normal embryogenesis (Fig. 3 (12, 18)) or remnants of embryos and more often degenerated mf between the reproductive cycles. Older and very old females often presented empty uteri (Figs. 3 (13–15) and 4 (19, 20, 22)) and signs of strong degeneration, as seen in worms from a traveller after 6 years or from patients living in previously endemic areas after 11 years of vector control.

Fig. 3.

A nulliparous (11) and a productive (12) young female O. volvulus from a 4-year-old child contain no or sparse iron in the gut (arrowheads). Scale bar = 50 µm. 13 A 6-year-old female worm from a patient who had briefly visited Nigeria 6 years before the nodulectomy. The gut contains much iron (arrowheads) and the muscle cells of the uterus contain brown pigment (arrow). Scale bar = 50 µm. 14 An old female worm from a patient nodulectomised after 11 years of vector control in Burkina Faso contains much iron in the gut (arrowhead). Scale bar = 50 µm. 15–16 Old female and male worms from patients after 11 years ivermectin treatment and 7 years vector control in the Itwara focus in western Uganda contain much iron in the gut (arrowheads). Scale bar = 50 µm. 17 A young male less than 27 months old contains only sparse iron in the gut (arrowhead). Scale bar = 50 µm

Fig. 4.

18 In a young fecund female O. volvulus from a 4-year-old child, the gut (arrowhead) is labelled for APR, whereas, the hypodermis is negative (arrow) except for the outer layer. Scale bar = 50 µm. 19 An old female with many APR-positive lysosomes in the hypodermis (arrow) and a strongly pigmented gut (arrowhead) from a patient after 11 years of vector control in Burkina Faso. Scale bar = 50 µm. 20 An old female with APR-positive hypodermis (arrow), gut (arrowhead) and uterus from a patient after 11 years of ivermectin treatment and seven years of vector control in the Itwara focus in Uganda. Scale bar = 50 µm. 21 Many strongly APR-positive lysosomes in hypodermis (arrow) and gut (arrowhead) of an old female after 11 years of ivermectin treatment. Scale bar = 50 µm. 22 An old female with APR-positive inclusions (arrow) characteristic for older age. Hypodermis, uterus and gut (arrowhead) are stained for APR. Scale bar = 50 µm. 23 An old male with APR-positive testis (arrow) and gut (arrowhead) after 11 years of vector control in Burkina Faso. Scale bar = 50 µm

Iron staining

Iron is taken up with the food. It originates from the haemoglobin of ingested erythrocytes and accumulates throughout the life span. Hence, the storage of iron in the worm tissues is correlated with the age of the worm (Fig. 3 (11–17)). Immature worms did not contain iron (not shown). Sixteen head nodules from a 4-year-old Liberian child contained 24 living female and nine male worms with no or only little iron (Fig. 3 (11, 12)). Since it needs at least 7 months to develop into adults, these were young worms and the nulliparous worms were probably less than 3 years old. However, for productive female and for male worms, it was difficult to decide whether they were 2, 3 or almost 4 years old. A single nulliparous female worm acquired by a traveller 6 years before nodulectomy during a short visit in West Africa contained already much iron in the gut but none in other tissues (Fig. 3 (13)). After seven or more years other tissues such as the muscles of the uterus and the body wall, hypodermis and uterus epithelium increasingly contained iron. Worms in nodules removed after 7–11 years of vector, control the old female worms, demonstrated much iron in the gut (Fig. 3 (14, 15)) and often also iron in other tissues (data not shown). Older males also had accumulated much iron (Fig. 3 (16)), whereas, a less than 27 months old young male contained only sparsely iron (Fig. 3 (17)). Therefore, one can conclude that iron deposition starts in the gut.

Labelling of lysosomal aspartic protease

An immunoassay for APR was also used for the estimation of worm age. The enzyme plays a role in the process of digestion of food in the gut and in all cells and tissues where degenerated material has to be removed (Jolodar et al. 2004). The gut of O. volvulus was always APR-positive, and the labelling was stronger in older worms, probably because they need more food, as they are larger and they produce embryos. In contrast, other tissues such as the hypodermis and the uterus endothelium became more positive with increasing age corresponding to the proceeding degeneration of the tissues (Fig. 4 (18–23)). Therefore, APR was usually less expressed in immature and other young worms (Fig. 4 (18)). It was strongly expressed in lysosomes associated with degradation of degenerated cell components (Fig. 4 (19–23)) and with inclusion bodies (Fig. 4 (22)), both characteristics for older worms (Jolodar et al. 2004). Other filarial compounds may be used instead of APR as long as they show variations depending on worm age, for example the CuZn superoxide dismutase in the gut of O. volvulus (Wildenburg and Henkle-Dührsen 1999).

Male filariae

For male worms, the same criteria were applied as those described for females. But again it was difficult to differentiate 2- to 3-year-old from 4- to 5-year-old male worms. Since the males are small, the storage of iron was much less than in the 100 times heavier productive females. However, males older than 7 years showed strong iron deposition in the gut, as did the 11-year-old male of Fig. 3 (16) or the strong staining for APR in several organs (Fig. 4 (23)). In doxycycline trials, 12 and more months after 6 weeks of doxycycline treatment, all Wolbachia-positive male worms showed the criteria of young worms compared with the old filariae (see Specht, Hoerauf et al. in preparation).

Discussion

The average life expectancy of O. volvulus is estimated to be 9–11 years, and the reproductive life span ends before the age of 13–14 years based on the observation of mf in four villages in the savannah (Plaisier et al. 1991; see for further references). We found comparable figures based on studies of filariae collected after collagenase digestion of the human nodule tissue in the forest zone in Liberia and in the savannah in Ghana and Burkina Faso (Büttner and Weiss 1984; Büttner et al. 1983; 1988; 1990; Albiez et al. 1987). Considering this, one may designate worms less than 4 years old as young, 4–6 years as middle-aged, 7–10 years as old, and those (few) more than 10 years as very old. For example, 12 years after the beginning of vector control in northern Ghana and Burkina Faso, we collected only very old worms (Albiez et al. 1987; Büttner et al. 1990) in spite of some filaria-positive blackflies at the rivers Sissily and Bougouriba.

The age estimation of O. volvulus in a large drug trial was first applied by Duke et al. (2002) to assess the intensity of transmission. When they had no means to assess the Annual Transmission Potential (ATP) while a large IVM trial was in progress and no pre-treatment base-line ATP figures were available, they used the determination of the average age of the worm population to estimate the acquisition of new young female worms during the trial. They counted the young nulliparous worms in full production of oocytes as a subpopulation probably recently acquired. They used for their assessment a classification of the female worms (Duke et al. 2002; Duke 2005), which we have followed except that we also included the definition of immature worms. Since in another report we were interested in the identification of newly acquired worms with regard to drug trials (Specht, Hoerauf et al. in preparation), we differentiated only young worms less than 3–4 years from all other older worms. It is however also possible to differentiate the groups of older worms, if this is needed.

It needs to be mentioned that there are always a small number of worms with exceptions from the described characteristics. Further, drug-treated filariae may show signs of drug-induced degeneration, as we have observed after doxycycline. In this case, iron storage and APR-staining became more important than the morphology. The following assumptions are based on our findings and on the literature.

The fourth stage larvae moult to immature worms, which begin to produce oocytes or spermatocytes probably after seven or a few more months, since the minimal prepatent period is estimated to be 7 months (WHO 1987). Based on this figure and our observations, we assume that immature worms are less than 1 year old.

The next category refers to young nulliparous worms in full production of oocytes without degenerated remnant embryos or mf from a previous production cycle. In a highly endemic area, the prepatent period is usually not longer than 2–3 years (WHO 1987). However, some female worms may never become inseminated. We assume that nulliparous worms without signs of degeneration, none or sparse iron in the gut and weak APR-staining of the gut are less than 3 years and most of them are less than 2 years old. A few young worms with early insemination may contain remnant mf.

Worms with typical signs of older age, such as large diameter, degeneration of their tissues, increased amounts of iron in the gut and stronger APR-staining, producing reduced numbers of oocytes and often containing degenerated remnant mf, are probably older than 3 years. The age may be estimated by the degree of alterations described for older age.

Fecund worms producing embryos of all stages up to mf with the above described characteristics of young age are probably between 7 months and 2–3 years old, with mild signs of aging 4–5 years and with increasing signs of old age 6–14 years.

Senescent worms have empty uteri and show all signs of degeneration. They are certainly older than 3 years and most of them older than 6 years. However, some exceptions might occur, as we observed a calcified worm collected from a 3-year-old child. Worms with pleomorphic neoplasms (Duke et al. 2002) showed signs of middle aging.

Immature males and males with a small diameter, without signs of degeneration, with no or sparse iron, with weak APR-staining and normal spermatogenesis are certainly less than 5 years old and most of them are probably less than 3 years old.

Conclusion

For most O. volvulus worms, the differentiation between those 1–3 years young and older ones is possible using the criteria described above. Only for a few filariae remains the age estimation difficult.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ingeborg Albrecht and Klaus Jürries for the technical assistance. We are obliged to Dr. Kwablah Awadzi (Hohoe, Ghana) for onchocercomas from northern Ghana, Mr. Ephraim Tukesiga, (Vector Control Unit, Fort Portal, Uganda) for nodules from Uganda, Prof. IB Autenrieth (Tübingen, Germany) for the anti-hsp60 serum and Prof. Claudio Bandi (Milano, Italy) for the anti-WSP serum and Prof. Achim Hoerauf for critical reading of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

Nodulectomies for research purposes had been approved by the Ethics Commission of the Medical Board in Hamburg, and by the authorities of the respective African countries. The procedures used were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1975 and its revisions in 1983, 2000 and 2002).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- APR

O. volvulus lysosomal aspartic protease

- hsp60

heat shock protein 60

- mf

microfilaria

- WSP

Wolbachia surface protein

References

- Albiez EJ. Effects of a single complete nodulectomy on nodule burden and microfilarial density two years later. Trop Med Parasitol. 1985;36:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albiez EJ, Büttner DW, Schulz-Key H. Studies on nodules and adult Onchocerca volvulus during a nodulectomy trial in hyperendemic villages in Liberia and Upper Volta. II. Comparison of the macrofilaria population in adult nodule carriers. Trop Med Parasitol. 1984;35:163–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albiez EJ, Kaiser S, Büttner DW. The worm burden of Onchocerca volvulus in patients in Burkina Faso twelve years after interruption of the transmission. Trop Med Parasitol. 1987;38:348. [Google Scholar]

- Boussinesq M. Onchocerciasis control: biological research is still needed. Parasite. 2008;15:510–514. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2008153510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büttner DW, Weiss U (1984) The macrofilaria burden of children with onchocerciasis in West Africa. In: Proceedings of the International Congress of Infectious Diseases, Wien, 1983, Edizioni Luigi Pozzi, Rome, pp 153–156

- Büttner DW, Albiez E, Parow D. Parasitological studies on Onchocerca volvulus eight years after interruption of the transmission in Upper Volta. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1983;76:669–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büttner DW, Albiez EJ, von Essen J, Erichsen J. Histological examination of adult Onchocerca volvulus and comparison with the collagenase technique. Trop Med Parasitol. 1988;39:390–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büttner DW, Awadzi K, Opoku NO. Histological studies of onchocercomata from an area with interrupted transmission in Ghana. Acta Leiden. 1990;59:49–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke BOL. Observations and reflections on the immature stages of Onchocerca volvulus in the human host. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1991;85:103–110. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1991.11812536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke BOL. Evidence for macrofilaricidal activity of ivermectin against female Onchocerca volvulus: further analysis of a clinical trial in the Republic of Cameroon indicating two distinct killing mechanisms. Parasitology. 2005;130:447–453. doi: 10.1017/S0031182004006766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke BOL, Marty AM, Peet DL, Pardon J, Pion SDS, Kamgno J, Boussinesq M. Neoplastic change in Onchocerca volvulus and its relation to ivermectin treatment. Parasitology. 2002;125:431–444. doi: 10.1017/S0031182002002305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer P, Kipp W, Bamuhiga J, Binta-Kahwa J, Kiefer A, Büttner DW. Parasitological and clinical characterization of Simulium neavei-transmitted onchocerciasis in western Uganda. Trop Med Parasitol. 1993;44:311–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz M. The morphology of adult Onchocerca volvulus based on electron microscopy. Trop Med Parasitol. 1988;39:359–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garms R, Lakwo TL, Nyomugyenyi R, Kipp W, Rubaale T, Tukesiga E, Katamaywa J, Post RJ, Amazigo UV. The elimination of the vector Simulium neavei from the Itwara onchocerciasis focus in Uganda by ground larviciding. Acta Trop. 2009;111:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerauf A, Mand S, Volkmann L, Büttner M, Marfo-Debrekyei Y, Taylor M, Adjei O, Büttner DW. Doxycycline in the treatment of human onchocerciasis: kinetics of Wolbachia endobacteria reduction and of inhibition of embryogenesis in female Onchocerca worms. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:261–273. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(03)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerauf A, Specht S, Büttner M, Pfarr K, Mand S, Fimmers R, Marfo-Debrekyei Y, Konadu P, Debrah AY, Bandi C, Brattig N, Albers A, Larbi J, Batsa L, Taylor MJ, Adjei O, Büttner DW. Wolbachia endobacteria depletion by doxycycline as antifilarial therapy has macrofilaricidal activity in onchocerciasis: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2008;197:295–311. doi: 10.1007/s00430-007-0062-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerauf A, Specht S, Marfo-Debrekyei Y, Büttner M, Debrah AY, Mand S, Batsa L, Brattig N, Konadu P, Bandi C, Fimmers R, Adjei O, Büttner DW. Efficacy of 5-week doxycycline treatment on adult Onchocerca volvulus. Parasitol Res. 2009;104(2):437–447. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolodar A, Fischer P, Büttner DW, Miller DJ, Schmetz C, Brattig N. Onchocerca volvulus: expression and immunolocalization of a nematode cathepsin D-like lysosomal aspartic protease. Exp Parasitol. 2004;107:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna LG, editor. Manual of histologic staining methods of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. 3. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Ndyomugyenyi R, Tukesiga E, Büttner DW, Garms R. The impact of ivermectin treatment alone and when in parallel with Simulium neavei elimination on onchocerciasis in Uganda. Trop Med Inter Health. 2004;9:882–886. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfarr KM, Heider U, Schmetz C, Büttner DW, Hoerauf A. The mitochondrial heat shock protein 60 (HSP60) is up-regulated in Onchocerca volvulus after the depletion of Wolbachia. Parasitology. 2008;135:529–538. doi: 10.1017/S003118200700409X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaisier AP, van Ootmarssen GJ, Remme J, Habbema JDF. The reproductive lifespan of Onchocerca volvulus in West African savanna. Acta Tropica. 1991;48:271–284. doi: 10.1016/0001-706X(91)90015-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz-Key H. The collagenase technique: how to isolate and examine adult Onchocerca volvulus for the examination of drug effects. Trop Med Parasitol. 1988;39:423–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specht S, Hoerauf A, Adjei O, Debrah A, Büttner DW (2009) Newly acquired Onchocerca volvulus filariae after doxycycline treatment. Parasitol Res (in press). Sep 16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- WHO WHO expert committee on onchocerciasis. 3rd report. Wld Hlth Org Tech Rep Ser. 1987;752:1–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildenburg G, Henkle-Dührsen K. Onchocerca volvulus: immunolocalization of the extracellular CuZn superoxide dismutase using antibodies raised against a 15-mer epitope of this enzyme. Exp Parasitol. 1999;91:1–6. doi: 10.1006/expr.1999.4352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildenburg G, Krömer M, Büttner DW. Dependence of eosinophil granulocytes infiltration into nodules on the presence of microfilariae producing Onchocerca volvulus. Parasitol Res. 1996;82:117–124. doi: 10.1007/s004360050081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildenburg G, Korten S, Büttner DW. Mast cell distribution in nodules of Onchocerca volvulus from untreated patients with generalized onchocerciasis. Parasitology. 1998;116:257–268. doi: 10.1017/S0031182097002278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]