Abstract

Thirty-nine blaKPC-producing isolates of the family Enterobacteriaceae with carbapenem resistance or reduced carbapenem susceptibility were obtained from inpatients from eight hospitals in six cities of three provinces in eastern China. The pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis of all 36 Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates revealed six major patterns. The resistant plasmids of most isolates were successfully transferred by conjugation and evaluated experimentally to be 40 to 180 kb in size. A 20.2-kb blaKPC-surrounding nucleotide sequence from plasmid pKP048 has been obtained and contains an integration structure of a Tn3-based transposon and partial Tn4401 segment, with the gene order Tn3-transposase, Tn3-resolvase, ISKpn8, the blaKPC-2 gene, and the ISKpn6-like element. The chimera of several transposon-associated elements indicated a novel genetic environment of the K. pneumoniae carbapenemase β-lactamase gene in isolates from China.

Carbapenems often are used as the most appropriate agents in the treatment of infections caused by multiresistant gram-negative bacteria. However, reports of carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzymes have become increasingly frequent, and the most common carbapenemases to emerge in recent years have been the Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPCs) (8). These plasmid-carried Ambler class A enzymes have since been identified in multiple genera and species of the Enterobacteriaceae, including Klebsiella spp. (36), Escherichia coli (3), Enterobacter spp. (14), Citrobacter spp. (37), Salmonella spp. (18), Serratia marcescens (38), and Proteus mirabilis (29). The KPC-producing isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas putida also were reported recently (1, 30). The geographical distribution of blaKPC-producing isolates has widened not only within the United States, including the New York City region (2, 4, 5, 33), Pennsylvania, Ohio, Delaware, and Arkansas (8, 24), but also in Israel (22), France (21), Greece (7), Colombia (31), China (32), and recently in Argentina (23), Brazil (19), and the United Kingdom (34).

Whereas the KPC enzymes in novel locations are reported increasingly worldwide, very little information is known about the genetic elements around this resistance gene. Naas et al. characterized a new transposon-related structure named Tn4401, which mediated KPC β-lactamase mobilization in several blaKPC-positive K. pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa strains isolated from the United States, Colombia, and Greece (20). This transposon seems to be responsible for rapid blaKPC spread. Another finding for the blaKPC-surrounding structure was the KQ element, which is a large composite element consisting of a Tn1331 backbone and a Tn4401-like element and qnrB19 insertion (25). However, in China, the genetic environment of blaKPC genes is unclear. The aim of this study was to characterize the detailed genetic environment surrounding the blaKPC gene and report the emergence of blaKPC-2-producing Enterobacteriaceae, including K. pneumoniae, Citrobacter freundii, Klebsiella oxytoca, and Enterobacter cloacae isolates from several hospitals in eastern China.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

Thirty-nine nonduplicated isolates of the family Enterobacteriaceae (36 K. pneumoniae, 1 C. freundii, 1 K. oxytoca, and 1 E. cloacae isolate) with carbapenem resistance or reduced carbapenem susceptibility were obtained from inpatients from eight hospitals in six cities of three provinces in eastern China from March 2006 to December 2007 (Table 1). The species-level identification of these isolates was confirmed by an API 20E system. These isolates were recovered mainly from specimens of sputum and others, including blood, wound swabs, and urine.

TABLE 1.

MICs of several antimicrobial agents for 39 clinical isolates

| Hospital (city, province) | Isolate (n) | Clone | Genetic environment of blaKPC-2 | MICa (μg/ml)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEM | IPM | ETP | CST | TGC | CAZ | TZP | CIP | FOX | AMK | ||||

| a (Shanghai, Shanghai) | K. pneumoniae (1) | A | Consistent with pKP048 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 0.25 | 2 | >256 | >256 | >32 | >256 | >256 |

| b (Nanjing, Jiangsu) | K. pneumoniae (5) | B | Variant 1 | >32 | 16->32 | >32 | 0.5-1 | 0.5-2 | 128->256 | >256 | 8->32 | 128->256 | 1->256 |

| b (Nanjing, Jiangsu) | K. pneumoniae (3) | C | Variant 2 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 0.5-1 | 0.5-2 | >256 | >256 | >32 | 128->256 | 1->256 |

| c (Hangzhou, Zhejiang) | K. pneumoniae (10) | D | Consistent with pKP048 | 2->32 | 2->32 | 16->32 | 0.5-1 | 0.5-1 | 32->256 | >256 | >32 | 64->256 | >256 |

| c (Hangzhou, Zhejiang) | K. pneumoniae (5) | E | Variant 2 | 16->32 | 16->32 | >32 | 0.5-1 | 1-1.5 | 32->256 | >256 | >32 | 32-128 | 1->256 |

| c (Hangzhou, Zhejiang) | C. freundii (1) | Consistent with pKP048 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 0.75 | 2 | 32 | >256 | >32 | >256 | 2 | |

| d (Hangzhou, Zhejiang) | K. pneumoniae (9) | C | Variant 2 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 0.5-1 | 0.5-2 | >256 | >256 | >32 | 128->256 | 1->256 |

| e (Shaoxing, Zhejiang) | K. pneumoniae (2) | F | Consistent with pKP048 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 0.5-2 | 1 | >256 | >256 | 16->32 | >256 | 4 |

| f (Taizhou, Zhejiang) | K. pneumoniae (1) | F | Consistent with pKP048 | >32 | 32 | >32 | 0.75 | 0.38 | >256 | >256 | 12 | 32 | 2 |

| g (Taizhou, Zhejiang) | K. oxytoca (1) | Consistent with pKP048 | >32 | >32 | 16 | 1 | 2 | 128 | >256 | >32 | >256 | 2 | |

| h (Ningbo, Zhejiang) | E. cloacae (1) | Consistent with pKP048 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 0.5 | 2 | >256 | >256 | >32 | >256 | >256 | |

MEM, meropenem; IPM, imipenem; ETP, ertapenem; CST, colistin; TGC, tigecycline; CAZ, ceftazidime; TZP, piperacillin-tazobactam; CIP, ciprofloxacin; FOX, cefoxitin; AMK, amikacin.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

MICs of meropenem, imipenem, ertapenem, colistin, tigecycline, ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin, piperacillin-tazobactam, cefoxitin, and amikacin were determined by the Etest technique (AB Biodisk, Sweden) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the susceptibility breakpoints were interpreted as recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and some previous reports (11, 16). E. coli ATCC 25922 and E. coli ATCC 35218 were used as quality controls.

PCR for carbapenemase genes.

All original isolates and their E. coli transconjugants were screened by PCR with primers that are specific for the carbapenem resistance determinant, such as blaKPC, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaSME, blaIMI, and blaNMC, as described previously (33). All of the positive PCR products were sequenced as described below. All isolates were positive with blaKPC primers, confirming the production of a KPC enzyme.

PFGE.

Genomic DNA of all K. pneumoniae isolates was analyzed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) after digestion with XbaI (Sangon, China) using the contour-clamped homogenous electric field (CHEF) technique (13). DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose III (Sangon, China) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer with a CHEF apparatus (CHEF Mapper XA; Bio-Rad) at 14°C and 6 V/cm and with alternating pulses at a 120° angle in a 2- to 40-s pulse time gradient for 22.5 h. Salmonella enterica serotype Braenderup H9812 was used as the size marker (15). Restriction patterns were interpreted by the criteria proposed by Tenover et al. (28).

Plasmid manipulations and Southern hybridization.

The conjugation experiment was carried out in mixed-broth cultures. Rifampin (rifampicin)-resistant E. coli EC600 (LacZ− Nalr Rifr) was used as the recipient strain. Exponential-phase L broth cultures of donor and recipient were mixed at a volume ratio of 2:1. This mixture was incubated for 4 h at 35°C. The transconjugants were selected on Mueller-Hinton agar containing imipenem (1 μg/ml) or ampicillin (50 μg/ml) and rifampin (700 μg/ml). The selected transconjugants were identified by an API 20E system. The Qiagen Plasmid Midi kit (Qiagen, Germany) was used to extract plasmids according to the manufacturer's instructions. E. coli V517 (54, 5.6, 5.1, 3.9, 3.0, 2.7, and 2.1 kb), E. coli R1 (92 kb), and E. coli R27 (182 kb) were used as the standards for plasmid size analysis. For Southern blot hybridization, plasmids were transferred from electrophoresis gels to nylon membranes (Bio-Rad) and hybridized with [α-33P]dCTP (DuPont)-labeled blaKPC-2-specific probes. Probes were generated by PCR with primers KPC-A and KPC-B (Table 2). After being washed, the membrane was compressed with a storage phosphor screen (Kodak, Japan) for 48 h and then scanned for hybridization signals.

TABLE 2.

Primers for PCR amplification of the blaKPC-surrounding sequences

| Primer name | No. in Fig. 3 | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| For1231 | 1 | TCCTCTGCGTGAGCTACACT |

| Re4510 | 2 | TTCTGACCACTGAGCAGACT |

| For4100 | 3 | CAGGACGTTCGTTGCTTATC |

| Re5198 | 4 | GGCAATACTGAGCTGATGAG |

| For4710 | 5 | GTCTCAACCAGCCAGCAGTC |

| Re5712 | 6 | TTACGTAGATCCGAGACACC |

| For5451 | 7 | TGGCCAGGATGTACAACGTC |

| Re6282 | 8 | CATTCCTTGAGCGCCTGAAC |

| For5958 | 9 | TCAAGCTTCTGACCGACAAC |

| Re6838 | 10 | CCTTGAATGAGCTGCACAGT |

| Kpc-up | 11 | GCTACACCTAGCTCCACCTTC |

| Kpc-dw | 12 | ACAGTGGTTGGTAATCCATGC |

| For7085 | 13 | GCGATACCACGTTCCGTCTG |

| Re8069 | 14 | TCCGTAGTGAGGCTGTTCTG |

| For7755 | 15 | ACAGATACGCCATTCGCCTC |

| Re8728 | 16 | CGAACATAAGGCCGAACGTG |

| KPC-A | TGTAAGTTACCGCGCTGAGG | |

| KPC-B | CCAGACGACGGCATAGTCAT |

Shotgun sequencing of plasmid pKP048.

The plasmid pKP048 from a transconjugant of K. pneumoniae strain KP048 in Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China, was sequenced by using a whole-genome shotgun approach (27). DNA for plasmid pKP048 was randomly sheared by ultrasonication, and the 1.5- to 3.0-kb fragments were cloned into vector pUC18 (Takara Bio, Japan). End sequencing was performed by using BigDye Terminator 3.1 chemistry and a 3730XL sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Sequence gaps were filled by primer walking on linking clones and by the sequencing of the PCR products from the plasmid DNA. The resulting sequence data were assembled by using the Phred/Phrap/Consed software suite from the University of Washington, Seattle (9, 10, 12). GeneMark.hmm 2.4 was used to identify putative open reading frames (ORFs) (17). Nucleotide and amino acid sequences were analyzed and compared by use of the BLAST program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Genetic environment analysis of blaKPC gene.

A PCR mapping approach was carried out to compare the genetic context of the blaKPC gene in other isolates with that found in plasmid pKP048. A series of primers were designed at the base of blaKPC-surrounding sequences (Table 2). PCR experiments were performed according to standard conditions with an annealing temperature of 58°C. The obtained amplification products were sequenced.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

A 20,158-bp sequence surrounding the blaKPC gene has been submitted to the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under accession number FJ628167.

RESULTS

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

The MICs of a variety of antimicrobial agents tested against all isolates are shown in Table 1. All isolates were resistant to ertapenem, and most of them were resistant to meropenem and imipenem, except for five isolates from Hangzhou, for which the MICs were 2 μg/ml. All isolates also were resistant to ceftazidime, piperacillin-tazobactam, ciprofloxacin, and cefoxitin. These isolates were susceptible to colistin (MIC ≤ 2 μg/ml) and tigecycline (MIC ≤ 2 μg/ml). Of note, MICs of amikacin for these isolates were extremely variable. Seventeen isolates, including 15 K. pneumoniae isolates, 1 C. freundii isolate, and 1 K. oxytoca isolate, were susceptible to amikacin (MIC ≤ 4 μg/ml); in contrast, the rest were resistant (MIC ≥ 256 μg/ml).

PCR for carbapenemase genes.

The blaKPC gene was detected by PCR in all of the isolates, and sequencing results revealed that they belonged to the same KPC-2 allele as that reported several times already in China (32, 38). No metallo-carbapenemase gene (blaIMP and blaVIM) or other class A enzyme gene (blaSME, blaIMI, and blaNMC) was detected.

PFGE analysis.

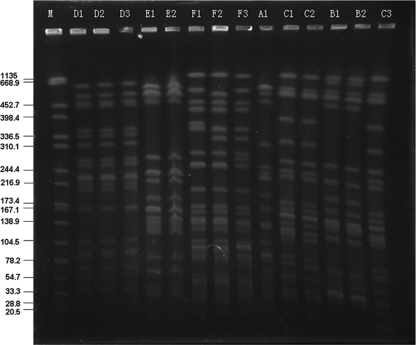

According to the datum-interpreting criteria described by Tenover et al. (28), the 36 clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae were grouped into six clonal patterns by PFGE, designated patterns A to F (Fig. 1). Pattern A was represented by one isolate that was from a hospital in Shanghai, and pattern B was represented by five isolates that were from a hospital in Nanjing. Twelve isolates representing pattern C were from the hospital of Nanjing (three isolates) and a hospital in Hangzhou (nine isolates). Another hospital in Hangzhou had 15 total isolates; 10 of them exhibited pattern D, and the other 5 represented pattern E. Pattern F, with three subtypes by three isolates, occurred in a hospital of Shaoxing (two isolates) and a hospital of Taizhou (one isolate) (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The four blaKPC-positive clones were observed in the unique region, including patterns A, B, D, and E, while the remaining clones were detected in separate regions (patterns C and F).

FIG. 1.

PFGE analysis of XbaI-digested genomic DNA from isolates of K. pneumoniae. M, marker (Salmonella enterica serotype Braenderup H9812); A1 was from hospital a in Shanghai; B1, B2, and, C3 were from hospital b in Nanjing; C1 and C2 were from hospital d in Hangzhou; D1, D2, D3, E1, and E2 were from hospital c in Hangzhou; F1 and F2 were from hospital e in Shaoxing; and F3 was from hospital f in Taizhou.

Plasmid manipulations and analysis.

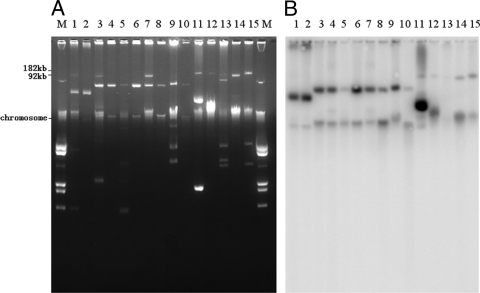

Except for 5 isolates of PFGE pattern B from Nanjing and 7 isolates of pattern C (3 isolates in Nanjing and 4 isolates in Hangzhou), plasmids in 27 isolates successfully transferred carbapenem resistance to E. coli by conjugation. Transconjugants exhibited a phenotype of resistance or reduced susceptibility to carbapenem that was similar to that of their parent isolates. The plasmids of clinical isolates and their transconjugants that possess the blaKPC-2 gene were extracted and experimentally evaluated to be 40 to 180 kb in size, displaying the diversity of their genetic contents. Electrophoretic profiles of a subset of these plasmids and hybridization with a blaKPC-2-specific probe are shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Electrophoretic profiles of plasmids (A) and hybridization with a blaKPC-2-specific probe (B). M, marker (E. coli V517); lanes 1 and 2, K. oxytoca from hospital g of Taizhou and its transconjugant; lanes 3 and 4, K. pneumoniae from hospital e of Shaoxing and its transconjugant; lanes 5 and 6, K. pneumoniae from hospital a of Shanghai and its transconjugant; lanes 7 and 8, E. cloacae from hospital h of Ningbo and its transconjugant; lanes 9 and 10, C. freundii from hospital c of Hangzhou and its transconjugant; lanes 11 and 12, K. pneumoniae from hospital c of Hangzhou harboring plasmid pKP048 and its transconjugant; lanes 13 and 14, K. pneumoniae from hospital d of Hangzhou and its transconjugant; and lane 15, K. pneumoniae from hospital b of Nanjing.

Characterization of the genetic environment of the blaKPC-2 gene.

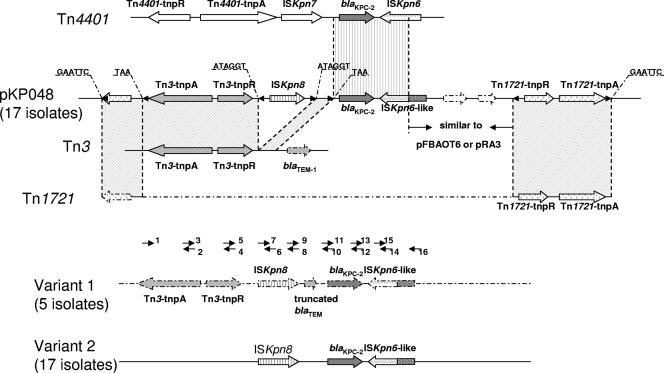

pKP048, a blaKPC-2-positive plasmid of ∼150 kb in size and 10−9 transconjugants/donor in frequency of conjugation, was selected for complete sequencing to explore the genetic environment of the blaKPC-surrounding sequence. While this project was being conducted, a nucleotide sequence of 20,158 bp surrounding the blaKPC-2 gene was obtained. The annotation of this sequence revealed several ORFs, and some of these have been associated with the blaKPC-2 gene. The immediate environment surrounding blaKPC-2 in pKP048 from China is composed of a partial Tn4401 structure and a Tn3-based element (Fig. 3). Tn4401, which was characterized as a blaKPC mobilization element in several blaKPC-producing isolates from the United States, Colombia, and Greece, consists of a transposase, a resolvase, a blaKPC gene, and two putative insertion sequence (IS) elements, ISKpn6 and ISKpn7. In pKP048, only a 2,070-bp region is identical to Tn4401, including the blaKPC-2 gene and an ISKpn6-like ORF (Fig. 3). An ISKpn6-like element downstream of the blaKPC-2 gene shared the same 287-amino-acid fragment in its C terminus with ISKpn6 in Tn4401 (a total of 439 amino acids). The inverted repeats (IRs) of ISKpn6 and its transposition-generated target site duplications (TSDs) are absent.

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of the novel genetic structure involved in the blaKPC-2 gene in China. ORFs are shown, and their directions of transcription are presented as broad arrows. Inverted repeats of the respective mobile elements are shown as small black triangles. Nucleotide letters above the sequence of pKP048 with underlining represent target site duplications. The gray-shaded area delimited by two dotted lines indicates identical regions. Short arrowheads with numbers show the primers listed in Table 2 and were used for PCR mapping.

Upstream of the blaKPC-2 gene is located a Tn3-based transposon, including its transposase and resolvase genes (Fig. 3). The Tn3-based element is flanked by two 3-bp TSDs (TAA) and 38-bp complete IRs, indicating the occurrence of a transposition event. The 3′ segment of the Tn3 transposon is disrupted by a novel putative IS element, designated ISKpn8, which encodes a putative transposase (326 amino acids) belonging to the IS481 family and is 57% similar in amino acids to a transposase from Pelobacter carbinolicus (NC_007498). Upon the breaking sites, ISKpn8 was found to be bracketed by two 6-bp TSDs (ATAGGT) and two incomplete 28-bp IRs. To explore both sides of the Tn4401-Tn3 integration region, we found a segment of the Tn1721 transposon. The segment of Tn1721 itself has inserted on the plasmid with a GAATTC TSD. It is split by a Tn4401-Tn3 integration region and a ca. 3-kb sequence that identified with plasmid pFBAOT6 (NC_006143) in Aeromonas punctata and plasmid pRA3 (DQ401103) in Aeromonas hydrophila (Fig. 3).

By using a PCR mapping approach, fragments of partial structures containing ISKpn8, blaKPC-2, and ISKpn6-like elements were obtained from all isolates, including three non-Klebsiella isolates. Seventeen isolates are consistent with the genetic environment in pKP048 completely. Moreover, there are another two variants in 22 isolates of our research. In five isolates of PFGE pattern B, a truncated blaTEM gene also was a part of the Tn3 transposon located between ISKpn8 and the blaKPC-2 gene. The 17 isolates belong to PFGE patterns C and E only obtained four PCR fragments lacking the Tn3-based transposase and its resolvase, suggesting the diversity of the genetic environment surrounding this region in blaKPC-producing isolates from China. Neither of the two variants has any detected segments of Tn1721. Sequences upstream and downstream of these two variants remain unclear.

DISCUSSION

In the last 7 years, several case and outbreak reports describing the presence of KPC β-lactamases have been published (26, 33, 35). The KPC-2 or KPC-3 allele has expanded rapidly across species and geographic regions because of clonal dissemination as well as horizontal gene transfer (8). Here, we describe the appearance of the KPC-2 enzyme in strains of the family Enterobacteriaceae with carbapenem resistance or reduced carbapenem susceptibility from eight hospitals in six cities of three provinces in eastern China.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing showed that carbapenem nonsusceptibility strains also were resistant to many other antimicrobial agents, such as ceftazidime, piperacillin-tazobactam, ciprofloxacin, and cefoxitin. These isolates were susceptible to colistin and tigecycline as described before (6), suggesting a choice for clinical therapy. The susceptibility to amikacin in these isolates was variable, because the 16S rRNA methylase gene armA was detected by PCR-based assays in all 22 isolates for which the MIC was ≥256 μg/ml. The nosocomial infection of blaKPC-producing isolates was due mainly to clonal dissemination, because each hospital possessed only one or two pulse clones. The interhospital clonal spread among separate geographic regions also has happened because isolates from two cities shared the same pattern.

Most isolates can easily transfer carbapenem resistance to E. coli by conjugation, indicating that the resistant plasmids possessed their own transfer-associated gene clusters. The sizes of these plasmids vary across a broad range, and the plasmid incompatibility group dissimilarity (data not show) exhibited different plasmid profiles, although their host shared the same PFGE pattern. Horizontal gene transfer and transposition events likely modified the genetic contents of resistant plasmids.

Previous studies of the genetic environment of the blaKPC gene had characterized a transposon-associated element, Tn4401, from K. pneumoniae isolate YC with a U.S. origin (20). The blaKPC-containing plasmids of isolates from Greece and Colombia also were analyzed. Tn4401 was considered the origin of blaKPC-like gene acquisition and dissemination. However, in our present work, the genetic environment of the blaKPC gene from isolates in China was distinct. The genetic environment surrounding the blaKPC-2 gene in most isolates from China is considered the integration of a Tn3-based transposon and a partial Tn4401 structure, with the ORF order of Tn3-transposase, Tn3-resolvase, ISKpn8, the blaKPC-2 gene, and the ISKpn6-like element. Part of Tn1721 (5′ segment) is interrupted by the overall integration region and itself is inserted with the duplication of 6-bp target site, suggesting the cotransposition of these transposon elements. The detailed analysis of all TSD and IR sequences revealed that several transposition events must be happening. We speculated that Tn1721 inserted first on the plasmid pKP048 containing the blaKPC-2 gene, the ISKpn6-like element, and another 3-kb sequence. Part of the Tn3-based transposon then inserted upstream of the blaKPC-2 gene. Subsequently, ISKpn8 was inserted downstream of the Tn3-resolvase gene independently because it possessed its own TSD and IR sequences. The hypothesis must be validated by further experiments.

Some isolates in our study also present diversity in this genetic structure, such as 17 isolates not having the Tn3-transposase and its resolvase and 5 isolates having a partial blaTEM gene fragment. The truncated blaTEM gene fragment belonging to the representative structure of the Tn3 transposon indicates the variety of the length of insertion segments. The sequences of the unknown regions in these isolates need to be explored in depth.

In conclusion, our study of 39 isolates of the family Enterobacteriaceae in China characterized the novel genetic environment of the blaKPC-surrounding sequence. The integration structure of the Tn3-based transposon and the partial Tn4401 segment indicated the diversity of the genetic environment harboring this widespread carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the Zhejiang Provincial Program for the Cultivation of High-Level Innovative Health Talents (no. 2007191) and the National Basic Research Programme 973 of China (no. 2005CB523101).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 July 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bennett, J. W., M. L. Herrera, J. S. Lewis, Jr., B. W. Wickes, and J. H. Jorgensen. 2009. KPC-2-producing Enterobacter cloacae and pseudomonas putida coinfection in a liver transplant recipient. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:292-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford, P. A., S. Bratu, C. Urban, M. Visalli, N. Mariano, D. Landman, J. J. Rahal, S. Brooks, S. Cebular, and J. Quale. 2004. Emergence of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella species possessing the class A carbapenem-hydrolyzing KPC-2 and inhibitor-resistant TEM-30 beta-lactamases in New York City. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:55-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bratu, S., S. Brooks, S. Burney, S. Kochar, J. Gupta, D. Landman, and J. Quale. 2007. Detection and spread of Escherichia coli possessing the plasmid-borne carbapenemase KPC-2 in Brooklyn, New York. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:972-975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bratu, S., D. Landman, R. Haag, R. Recco, A. Eramo, M. Alam, and J. Quale. 2005. Rapid spread of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in New York City: a new threat to our antibiotic armamentarium. Arch. Intern. Med. 165:1430-1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bratu, S., M. Mooty, S. Nichani, D. Landman, C. Gullans, B. Pettinato, U. Karumudi, P. Tolaney, and J. Quale. 2005. Emergence of KPC-possessing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Brooklyn, New York: epidemiology and recommendations for detection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3018-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castanheira, M., H. S. Sader, L. M. Deshpande, T. R. Fritsche, and R. N. Jones. 2008. Antimicrobial activities of tigecycline and other broad-spectrum antimicrobials tested against serine carbapenemase- and metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:570-573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuzon, G., T. Naas, M. C. Demachy, and P. Nordmann. 2008. Plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase KPC-2 in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from Greece. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:796-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deshpande, L. M., P. R. Rhomberg, H. S. Sader, and R. N. Jones. 2006. Emergence of serine carbapenemases (KPC and SME) among clinical strains of Enterobacteriaceae isolated in the United States medical centers: report from the MYSTIC Program (1999-2005). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 56:367-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ewing, B., and P. Green. 1998. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 8:186-194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ewing, B., L. Hillier, M. C. Wendl, and P. Green. 1998. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 8:175-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galani, I., F. Kontopidou, M. Souli, P. D. Rekatsina, E. Koratzanis, J. Deliolanis, and H. Giamarellou. 2008. Colistin susceptibility testing by Etest and disk diffusion methods. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 31:434-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon, D., C. Abajian, and P. Green. 1998. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 8:195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gouby, A., C. Neuwirth, G. Bourg, N. Bouziges, M. J. Carles-Nurit, E. Despaux, and M. Ramuz. 1994. Epidemiological study by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of an outbreak of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a geriatric hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:301-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hossain, A., M. J. Ferraro, R. M. Pino, R. B. Dew III, E. S. Moland, T. J. Lockhart, K. S. Thomson, R. V. Goering, and N. D. Hanson. 2004. Plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzyme KPC-2 in an Enterobacter sp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4438-4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter, S. B., P. Vauterin, M. A. Lambert-Fair, M. S. Van Duyne, K. Kubota, L. Graves, D. Wrigley, T. Barrett, and E. Ribot. 2005. Establishment of a universal size standard strain for use with the PulseNet standardized pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols: converting the national databases to the new size standard. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1045-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelesidis, T., D. E. Karageorgopoulos, I. Kelesidis, and M. E. Falagas. 2008. Tigecycline for the treatment of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a systematic review of the evidence from microbiological and clinical studies. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:895-904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lukashin, A. V., and M. Borodovsky. 1998. GeneMark.hmm: new solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:1107-1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miriagou, V., L. S. Tzouvelekis, S. Rossiter, E. Tzelepi, F. J. Angulo, and J. M. Whichard. 2003. Imipenem resistance in a Salmonella clinical strain due to plasmid-mediated class A carbapenemase KPC-2. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1297-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monteiro, J., A. F. Santos, M. D. Asensi, G. Peirano, and A. C. Gales. 2009. First report of KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains in Brazil. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:333-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naas, T., G. Cuzon, M. V. Villegas, M. F. Lartigue, J. P. Quinn, and P. Nordmann. 2008. Genetic structures at the origin of acquisition of the beta-lactamase blaKPC gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1257-1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naas, T., P. Nordmann, G. Vedel, and C. Poyart. 2005. Plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase KPC in a Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4423-4424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navon-Venezia, S., I. Chmelnitsky, A. Leavitt, M. J. Schwaber, D. Schwartz, and Y. Carmeli. 2006. Plasmid-mediated imipenem-hydrolyzing enzyme KPC-2 among multiple carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli clones in Israel. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3098-3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasteran, F. G., L. Otaegui, L. Guerriero, G. Radice, R. Maggiora, M. Rapoport, D. Faccone, A. Di Martino, and M. Galas. 2008. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-2, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:1178-1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pope, J., J. Adams, Y. Doi, D. Szabo, and D. L. Paterson. 2006. KPC type beta-lactamase, rural Pennsylvania. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:1613-1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rice, L. B., L. L. Carias, R. A. Hutton, S. D. Rudin, A. Endimiani, and R. A. Bonomo. 2008. The KQ element, a complex genetic region conferring transferable resistance to carbapenems, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3427-3429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samra, Z., O. Ofir, Y. Lishtzinsky, L. Madar-Shapiro, and J. Bishara. 2007. Outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae producing KPC-3 in a tertiary medical centre in Israel. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 30:525-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen, P., Y. Jiang, Z. Zhou, J. Zhang, Y. Yu, and L. Li. 2008. Complete nucleotide sequence of pKP96, a 67,850 bp multiresistance plasmid encoding qnrA1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr and blaCTX-M-24 from Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:1252-1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tibbetts, R., J. G. Frye, J. Marschall, D. Warren, and W. Dunne. 2008. Detection of KPC-2 in a clinical isolate of proteus mirabilis and first reported description of carbapenemase resistance caused by a KPC beta-lactamase in P. mirabilis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:3080-3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villegas, M. V., K. Lolans, A. Correa, J. N. Kattan, J. A. Lopez, and J. P. Quinn. 2007. First identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates producing a KPC-type carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1553-1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villegas, M. V., K. Lolans, A. Correa, C. J. Suarez, J. A. Lopez, M. Vallejo, and J. P. Quinn. 2006. First detection of the plasmid-mediated class A carbapenemase KPC-2 in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from South America. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2880-2882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei, Z. Q., X. X. Du, Y. S. Yu, P. Shen, Y. G. Chen, and L. J. Li. 2007. Plasmid-mediated KPC-2 in a Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:763-765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woodford, N., P. M. Tierno, Jr., K. Young, L. Tysall, M. F. Palepou, E. Ward, R. E. Painter, D. F. Suber, D. Shungu, L. L. Silver, K. Inglima, J. Kornblum, and D. M. Livermore. 2004. Outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing a new carbapenem-hydrolyzing class A beta-lactamase, KPC-3, in a New York medical center. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4793-4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woodford, N., J. Zhang, M. Warner, M. E. Kaufmann, J. Matos, A. Macdonald, D. Brudney, D. Sompolinsky, S. Navon-Venezia, and D. M. Livermore. 2008. Arrival of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing KPC carbapenemase in the United Kingdom. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:1261-1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yigit, H., A. M. Queenan, G. J. Anderson, A. Domenech-Sanchez, J. W. Biddle, C. D. Steward, S. Alberti, K. Bush, and F. C. Tenover. 2001. Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1151-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yigit, H., A. M. Queenan, J. K. Rasheed, J. W. Biddle, A. Domenech-Sanchez, S. Alberti, K. Bush, and F. C. Tenover. 2003. Carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella oxytoca harboring carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase KPC-2. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3881-3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang, R., L. Yang, J. C. Cai, H. W. Zhou, and G. X. Chen. 2008. High-level carbapenem resistance in a Citrobacter freundii clinical isolate is due to a combination of KPC-2 production and decreased porin expression. J. Med. Microbiol. 57:332-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang, R., H. W. Zhou, J. C. Cai, and G. X. Chen. 2007. Plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolysing beta-lactamase KPC-2 in carbapenem-resistant Serratia marcescens isolates from Hangzhou, China. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59:574-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]