Abstract

Candida biofilms are microbial communities, embedded in a polymeric matrix, growing attached to a surface, and are highly recalcitrant to antimicrobial therapy. These biofilms exhibit enhanced resistance against most antifungal agents except echinocandins and lipid formulations of amphotericin B. In this study, biofilm formation by different Candida species, particularly Candida albicans, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis, was evaluated, and the effect of caspofungin (CAS) was assessed using a clinically relevant in vitro model system. CAS displayed in vitro activity against C. albicans and C. tropicalis cells within biofilms. Biofilm formation was evaluated after 48 h of antifungal drug exposure, and the effects of CAS on preformed Candida species biofilms were visualized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Several species-specific differences in the cellular morphologies associated with biofilms were observed. Our results confirmed the presence of paradoxical growth (PG) in C. albicans and C. tropicalis biofilms in the presence of high CAS concentrations. These findings were also confirmed by SEM analysis and were associated with the metabolic activity obtained by biofilm susceptibility testing. Importantly, these results suggest that the presence of atypical, enlarged, conical cells could be associated with PG and with tolerant cells in Candida species biofilm populations. The clinical implications of these findings are still unknown.

Candida species are opportunistic pathogens that cause superficial and systemic diseases in critically ill patients (8, 22, 44) and are associated with high mortality rates (35%) and costly treatments (8, 19). They rank among the four most common causes of bloodstream infection in U.S. hospitals, surpassing gram-negative rods in incidence (6, 17).

Recent studies suggest that the majority of disease produced by this pathogen is associated with a biofilm growth style (7, 16, 28, 48). Biofilms are self-organized communities of microorganisms that grow on an abiotic or biotic surface, are embedded in a self-produced matrix consisting of an extracellular polymeric substance (14, 15, 55), and when associated with implanted medical devices are commonly refractive to antimicrobial therapy.

As opportunistic pathogens, Candida species are able to attach to polymeric surfaces and generate a biofilm structure, protecting the organisms from the host defenses and antifungal drugs (11, 16, 45, 48). Candida biofilms are more resistant than their planktonic counterparts to various antifungal agents, including amphotericin B (AMB), fluconazole, itraconazole, and ketoconazole (20, 38, 50). However, the molecular basis for the antifungal resistance of biofilm-related organisms is not completely understood.

The complex architecture of Candida biofilms observed both in vitro and in vivo suggests that morphological differentiation to produce hyphae plays an important role in biofilm formation and maturation (7, 32, 33). Baillie and Douglas demonstrated that although mutant cells fixed in either a hyphal or a yeast form can develop into biofilms, the hyphal structure is the essential element for providing the integrity and multilayered architecture of a biofilm (4). It has been reported that Candida parapsilosis, C. glabrata, and C. tropicalis biofilms are not as large as those generated by C. albicans; however, further structural analysis studies are needed to describe biofilm formation by these organisms (30, 31).

The mechanisms responsible for the resistance characteristics displayed by Candida biofilms are unclear. Possible mechanisms include a decreased growth rate; nutrient limitation of cells in the biofilm; expression of resistance genes, particularly those encoding efflux pumps; increased cell density; cell aging; or the presence of “persister” cells in the biofilm (1, 3, 5, 29, 34, 36, 38, 43, 46, 48, 50, 51).

The echinocandins are a novel class of semisynthetic amphiphilic lipopeptides that display important antifungal activity. The echinocandins that are presently marketed are caspofungin (CAS), micafungin, and anidulafungin. The echinocandins show considerable efficacy in vitro and in vivo in the treatment of candidemia and invasive candidiasis (25, 27, 42). CAS is the first antifungal agent to be licensed that inhibits the synthesis of β-1,3-glucan, the major structural component of Candida cell walls; glucan synthesis might prove to be a particularly effective target for biofilms (29, 31, 38, 48, 50). The paradoxical attenuation of antifungal activity at high echinocandin concentrations is a phenomenon that usually occurs with C. albicans isolates and appears to be specific to CAS among echinocandins. The cells surviving at high concentrations appear to be subject to some drug effect, showing evidence of slowed growth in the presence of CAS (53, 54). Recent studies have described this effect in Candida species biofilms (24, 37, 47); however, we are not aware of studies that have elucidated the effect of CAS on Candida biofilm structure. The present study was designed to (i) characterize the in vitro biofilm growth of Candida species bloodstream isolates and (ii) use scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to obtain visual evidence of the effect of CAS on biofilm morphology changes associated with paradoxical growth (PG).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms.

Three clinical Candida sp. isolates, including one isolate of C. albicans (CA4), one isolate of C. tropicalis (CT8), and one isolate of C. parapsilosis (CP1), were evaluated in our study. All strains were obtained from patients with candidemia who were admitted to the intensive care unit of Vera Cruz Hospital (Belo Horizonte, Brazil). These clinical isolates were identified using conventional physiological and morphological methods such as the germ-tube test in serum, micromorphology on cornmeal-Tween 80 agar, and metabolic properties using the ID32C system (bioMerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France).

Medium and growth conditions.

The organism stocks were maintained at −70°C. Each frozen stock culture was initially inoculated onto Sabouraud dextrose agar (Difco, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) and incubated at 35°C for 24 h. Colonies were then picked and added to a tube containing RPMI 1640 broth medium with l-glutamine and without bicarbonate (Sigma Chemicals), buffered to pH 7.0 with 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid (165 M; Sigma Chemicals). A standardized suspension of 1.0 × 106 CFU/ml (optical density at 600 nm, 0.12) was prepared for all experiments and was used immediately.

Substrate material.

Flat circular silicone disks, measuring 13 mm in diameter and 4 mm in thickness, were obtained from Biosurface Technologies (Bozeman, MT). The disks were washed in dilute laboratory soap (Versaclean; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), rinsed at least five times in reverse-osmosis-purified water, rinsed once in 70% ethanol, air dried, and autoclaved before use.

Preconditioning of films with human serum.

The blood used in our experiments was obtained from the Division of Scientific Resources (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Blood was collected from donors who were nonsmokers, took no medications, and had previously tested negative for blood-borne pathogens. The blood was incubated at 37°C for 1 h and then centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 20 min. Serum was removed, filter sterilized, and incubated in a water bath at 56°C for 30 min to allow complement inactivation. Aliquots were stored at −30°C until use.

Biofilm formation.

Mature Candida biofilms were formed as described previously (11, 29, 30, 36). Autoclaved silicone disks were placed in 12-well tissue culture plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY), one disk per well, incubated in human serum for 24 h at 37°C, and rinsed in 5 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove the excess serum. Disks were transferred to a new 12-well plate containing 3 ml of a 1 × 106-CFU ml−1 Candida cell suspension. Disks were incubated at 37°C for 1.5 h with shaking at 100 rpm so that the cells could attach. Following the attachment phase, coupons were rinsed gently in PBS, transferred to new plates containing fresh RPMI 1640 broth, and incubated for 72 h at 35°C on a rocker table to allow biofilm formation. For controls, disks were handled in an identical fashion except that no Candida cells were added. All assays were carried out in triplicate.

Quantitative measurement of biofilms.

Quantitation of Candida biofilms was performed as described previously (11, 23, 29, 30, 37, 45) using the 2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino)carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium hydroxide (XTT) reduction assay. XTT (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) is reduced by mitochondrial dehydrogenase to a water-soluble formazan product that is measured spectrophotometrically. The 50% reduction in the metabolic activity (50% RMA) of the biofilm could be correlated with the MIC50 (MIC at which there is 50% growth inhibition compared to the growth of the control), as determined by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) broth microdilution method M27-A (11, 21). Briefly, an XTT-menadione solution was prepared fresh each day of testing by adding 1.5 ml of XTT (1 g/liter in Ringer's lactate; Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO) to 300 μl of menadione solution (0.4 mM in acetone; Sigma Chemicals). Disks containing Candida species biofilms were washed and transferred to a new 12-well tissue culture plate containing 3 ml of PBS and 180 μl of XTT-menadione solution (prepared as described above) per well. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 h, and the medium was removed and centrifuged for 5 min at 6,000 × g to pellet any suspended cells or debris. The amount of XTT-formazan in the supernatant was measured at 490 nm by using a spectrophotometer (Hach Company, Loveland, CO).

Antifungal susceptibility.

CAS was from Merck (Rahway, NJ). For the planktonic susceptibility testing, we used the CLSI broth microdilution method (40). Candida isolates were stored at −70°C until use. Each isolate was plated on Sabouraud dextrose agar and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Stock solutions of CAS were prepared in sterile saline and diluted in RPMI 1640 medium. Dilutions ranging from 16 to 0.0625 μg/ml were tested. The lowest concentration associated with a significant reduction in turbidity from that of the control well at 48 h was used as the MIC of CAS.

For biofilm susceptibility testing, biofilms were formed in RPMI 1640 medium as described above. After 24 h of biofilm growth, disks containing preformed biofilms were washed three times with PBS prior to challenge with CAS. CAS was diluted in RPMI 1640 medium to yield 10 doubling serial dilutions ranging from 0.25 to 128 μg/ml. Biofilm-containing disks were gently agitated and transferred to new culture plates containing RPMI 1640 medium (3 ml) and different concentrations of the antifungal agent. After exposure to the antifungal agent for 48 h at 35°C on a rocker table, biofilm activity was measured by XTT reduction as described above. The antifungal concentration that caused a 50% RMA of the biofilm compared with the metabolic activity of the drug-free (untreated) control was then determined. Isolates were tested in triplicate.

Candida species biofilm quantification by plate count after CAS exposure.

Candida biofilms were preformed on silicone disks as described above. After 48 h of exposure to different concentrations of CAS, the disks were removed aseptically and washed gently in 5 ml PBS to remove planktonic and loosely adherent cells. Individual disks were transferred to 10 ml PBS and subjected to sonication for 10 min at 42 kHz (model 2510 sonicator; Branson, Danbury, CT), followed by high-speed vortexing for 30 s, further sonication for 5 min, vortexing for 30 s, sonication for 30 s, and a final vortexing for 30 s. A Candida suspension was diluted in Butterfield buffer (Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Sparks, MD) and spread on Sabouraud dextrose agar. Earlier studies indicated that the process removed essentially all of the viable Candida sp. cells from the surface of the disk and that sonication was not associated with a loss of viability of the cells in suspension (data not shown). In each experiment, the counts of viable cells on three different disks were established, and the mean counts for tested isolates were expressed as CFU per square centimeter.

SEM.

For examination by SEM, Candida species biofilms were grown as described in the preceding section using 12-well tissue culture plates. After 24 h of growth, the disks were washed with PBS, and different CAS concentrations (1.0, 16, and 128 μg of CAS/ml of RPMI 1640) were added to the samples. Plates were then incubated for an additional 48 h at 35°C on a rocker table. Control (untreated) samples were incubated in RPMI 1640 only. The drug concentrations were selected on the basis of the metabolic activity results obtained in the susceptibility testing assays.

After incubation, the samples (disks containing biofilms) were washed with PBS and placed in a fixative solution of 5% glutaraldehyde in cacodylate buffer (0.67 M; pH 6.2) overnight at room temperature. Samples were then dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, immersed in hexamethyldisilazane (Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA), and finally air dried overnight at room temperature. The samples were then mounted on aluminum stubs with silver paint, sputter coated with gold (Polaron SC7640 sputter coater; Thermo VG Scientific, United Kingdom), and observed with a FEI XL30 environmental SEM (FEI Co., Hillsboro, OR). The entire surface of the sample was examined, and images that were representative of the sample were taken. Experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed using the two-tailed t test and Excel 2003 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

In vitro activities of CAS and AMB against preformed Candida species biofilms.

The susceptibilities of C. albicans, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis planktonic (free-floating) cells and biofilms to CAS are shown in Table 1. The planktonic Candida isolates used in our study were highly susceptible to the antifungal agents tested, though C. parapsilosis tended to be less susceptible than the other species.

TABLE 1.

Antifungal susceptibilities of different Candida sp. isolates under planktonic and biofilm growth conditions as determined using the CLSI and XTT methodsa

| Isolate | MIC (μg/ml) of CAS for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Planktonically grown cellsb | Biofilms at 48 h (SMIC50)c | |

| C. albicans (CA4) | 0.0625 | 0.5 |

| C. parapsilosis (CP1) | 0.25 | 4 |

| C. tropicalis (CT8) | 0.0625 | 0.25 |

Results are representative of at least three separate experiments.

The MIC end point for planktonic cells is based on visual determination of the lowest drug concentration that produced a prominent decrease in growth relative to the growth in the drug-free control well.

The MIC end point for biofilms is based on the lowest drug concentration producing a 50% RMA relative to the metabolic activity of the untreated growth control, as measured by the XTT reduction assay.

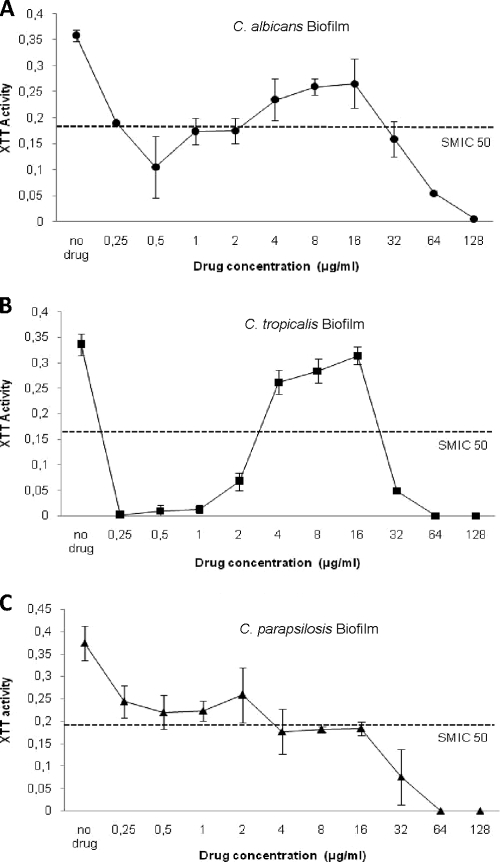

The biofilm susceptibility test results are shown in Fig. 1. As shown in Fig. 1A to C, the sessile MICs (SMICs), which are the 50% reductions in metabolic activity, of CAS for C. tropicalis, C. albicans, and C. parapsilosis biofilms were not comparable to the planktonic MICs for these organisms. The SMICs for biofilms of C. tropicalis and C. albicans were estimated as 0.25 and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively, more than 2 dilutions higher than their planktonic MICs (Table 1). The SMIC for C. parapsilosis (4 μg/ml) was 16 times the planktonic MIC (Fig. 1C), demonstrating that biofilm-associated C. parapsilosis cells are substantially more resistant to CAS than their planktonic counterparts.

FIG. 1.

Metabolic activities of biofilms of Candida species exposed to different concentrations of CAS. Metabolic activity is expressed as the average optical density of silicone disks containing treated biofilms compared to that for untreated biofilms (control). (A) C. albicans; (B) C. tropicalis; (C) C. parapsilosis. Error bars, standard deviations (n = 3).

The susceptibility pattern exhibited by C. tropicalis and C. albicans in which biofilm cells were less susceptible to CAS at concentrations above the SMIC (4 to 16 μg/ml) than at ∼0.25 to 2 μg/ml is termed paradoxical growth. PG with CAS was not observed for C. parapsilosis. Overall, these results suggest that CAS is more effective against preformed C. albicans and C. tropicalis biofilms.

Microscopic evaluation of PG in Candida species biofilms.

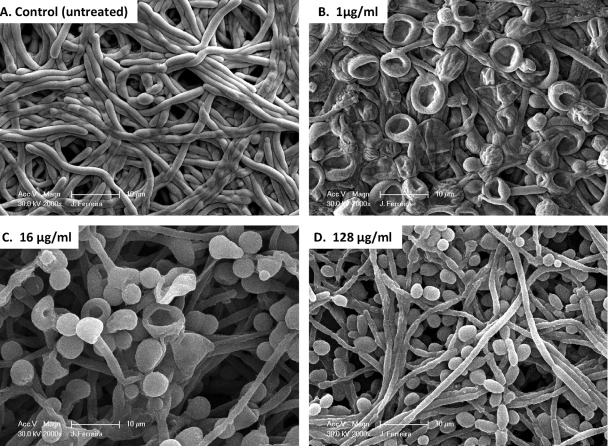

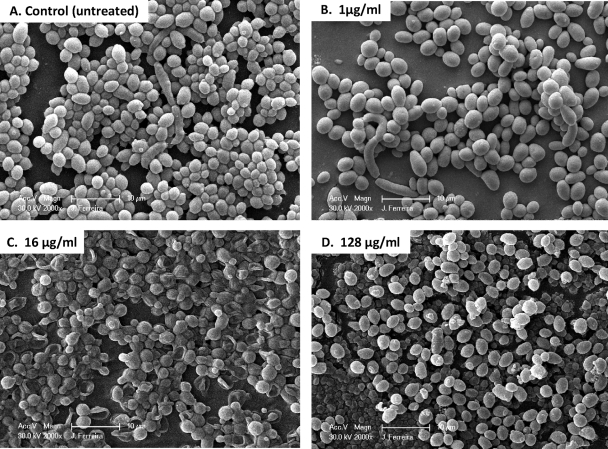

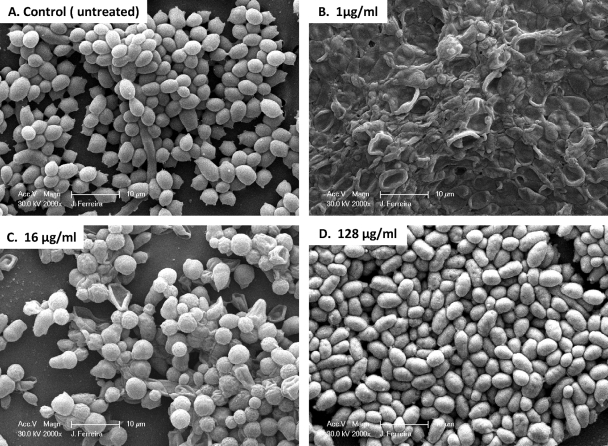

In an effort to correlate PG with Candida cellular morphological changes, we used SEM to examine the effects of different CAS concentrations on biofilm-associated cells. SEM provided useful information on the different cellular morphologies present in the biofilm structure. Triplicate disks containing biofilms of each species were exposed to three different CAS concentrations (1, 16, and 128 μg/ml) and were compared to the untreated controls. Because silicone disks have a uniformly flat surface, planar imaging was readily obtained. Figures 2 to 4 show SEM images of biofilms formed by different Candida species. C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis (Fig. 3 and 4, respectively) produced less-extensive biofilms than C. albicans (Fig. 2). SEM also revealed species-specific differences in biofilm structure. The biofilm architecture of the C. albicans control (untreated) was highly heterogeneous, composed of a dense layer of yeasts, pseudohyphae, and hyphal forms (Fig. 2A). C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis biofilms displayed a typical microcolony/water channel architecture containing yeast cell aggregates (irregular groupings of basal blastospore layers) and filamentous forms (Fig. 3A and Fig. 4A).

FIG. 2.

Scanning electron micrographs of preformed Candida albicans biofilms in the presence of different CAS concentrations. Biofilms were grown on silicone disks for 24 h prior to exposure to the antimicrobial agent; then they were incubated for 48 h in RPMI 1640 medium containing different concentrations of CAS. (A) C. albicans biofilm without drug (control); (B through D) C. albicans biofilms after exposure to CAS at 1 μg/ml, 16 μg/ml, or 128 μg/ml, respectively. Images represent typical fields of view. Bars, 10 μm.

FIG. 4.

Scanning electron micrographs of preformed Candida parapsilosis biofilms in the presence of different CAS concentrations. Biofilms were grown on silicone disks for 24 h prior to exposure to the antimicrobial agent; then they were incubated for 48 h in RPMI 1640 medium containing different concentrations of CAS. (A) C. parapsilosis biofilm without drug (control); (B through D) C. parapsilosis biofilms after exposure to CAS at 1 μg/ml, 16 μg/ml, or 128 μg/ml, respectively. Images represent typical fields of view. Bars, 10 μm.

FIG. 3.

Scanning electron micrographs of preformed Candida tropicalis biofilms in the presence of different CAS concentrations. Biofilms were grown on silicone disks for 24 h prior to exposure to the antimicrobial agent; then they were incubated for 48 h in RPMI 1640 medium containing different concentrations of CAS. (A) C. tropicalis biofilm without drug (control); (B through D) C. tropicalis biofilms after exposure to CAS at 1 μg/ml, 16 μg/ml, or 128 μg/ml, respectively. Images represent typical fields of view. Bars, 10 μm.

After exposure to CAS, preformed biofilms of C. albicans exhibited fewer hyphae and a substantial increase in the number of enlarged blastospores, most of which appeared to have collapsed after the 1-μg/ml treatment. Collapsed blastospores were also observed, to a lesser extent, after the 16-μg/ml treatment. Biofilms exposed to 128 μg/ml CAS contained substantially more blastospores (although they were smaller that those seen at 1 and 16 μg/ml) than non-drug-exposed biofilms but otherwise appeared unaffected by CAS treatment. Biofilms grown in 1 μg/ml CAS had viable counts approximately 2 log CFU/cm2 lower than untreated biofilms, but counts at 16 μg/ml were approximately equivalent to those of the control (Table 2). After exposure to 128 μg/ml CAS, preformed biofilms had reduced but detectable viable counts, but no XTT reduction was detectable (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Median viable cell counts recovered from silicone coupons

| CAS concn (μg/ml) | Median viable cell count (log CFU/cm2)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | C. tropicalis | C. parapsilosis | |

| No drug | 6.4 | 4.6 | 6.5 |

| 0.25 | 4.4 | 0 | 6.4 |

| 0.5 | 3.4 | 0 | 6.2 |

| 1 | 3.3 | 0 | 5.7 |

| 2 | 4.7 | 0 | 5.9 |

| 4 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 5.7 |

| 8 | 5.6 | 5.2 | 5.7 |

| 16 | 6.2 | 4.5 | 5.7 |

| 32 | 5.6 | 4.2 | 5.4 |

| 64 | 4.6 | 3.6 | 5.0 |

| 128 | 3.5 | 2.7 | 3.3 |

Unlike C. albicans, C. tropicalis did not exhibit substantial changes in cellular morphology when grown in the presence of CAS (Fig. 2 and 3). However, all of the cells in all fields examined exhibited collapsed cell walls when grown in the presence of 1 μg/ml CAS. There was substantially less effect on cellular morphology at 16 μg/ml CAS, though conically shaped cells were observed. After exposure to 128 μg/ml of CAS, preformed biofilms appeared very similar morphologically to untreated biofilms. Viable counts and XTT activity agreed for the 1- and 16-μg/ml exposures to CAS (Table 2 and Fig. 1A). However, biofilms showed reduced but still detectable viable counts after the 128-μg/ml exposure; no XTT activity was detected at this concentration. Cells exposed to 128 μg/ml CAS were similar morphologically to the untreated control.

C. parapsilosis biofilms were composed predominantly of yeast cells, whether or not they were exposed to CAS. In contrast to the effects on C. albicans and C. tropicalis, 1 μg/ml CAS did not appear to affect C. parapsilosis cell structures. An effect on cell morphology was observed at 16 but not 128 μg/ml. Viable counts and metabolic activity demonstrated gradual reductions with increasing CAS concentrations. No XTT reduction was detectable at 64 or 128 μg/ml, though viable cells were detected (Table 2). These results suggest that for C. albicans and C. tropicalis, PG is associated with increased metabolic activity, increased viable counts, and a change in the predominant cellular morphology within the biofilm.

DISCUSSION

In recent years, the ability of Candida species to form biofilms has been evaluated (16, 20, 23, 29, 39, 45, 49, 52). Special attention has been focused on the clinical setting, where Candida biofilms have gained prominence because of the recognition that the frequent use of medical devices has led to a concomitant increase in device-related infections (16, 31, 48). Biofilm cells are characterized by significantly enhanced resistance to some antifungal agents and altered phenotypes, making eradication difficult (4, 11, 31, 32, 48). An understanding of the complexities of Candida species biofilm development and phenotypic characteristics will allow us to create new strategies aimed at eradicating and preventing this process, thereby reducing the incidence of these infections.

Using a biofilm model system, we confirmed the SMIC50s for isolates from three medically relevant Candida species: C. albicans, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis. Our biofilm MIC results confirmed the findings of other groups indicating that CAS has good in vitro activity against C. albicans and C. tropicalis at clinical concentrations (2, 12, 29, 37, 47). We assumed, as previously published by others (11, 21, 37), that measurements based on XTT metabolic activity were sufficient to indirectly quantify biofilms. While XTT measurement may be used to monitor biofilm formation, microscopy analyses are critical for strain and species comparisons (31). The PG effect was confirmed in our study for C. albicans and C. tropicalis but not for C. parapsilosis. Our quantitative biofilm results are partially in agreement with those of a study published by Melo and colleagues for C. albicans, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis (37). They reported high frequencies of PG for C. albicans (100% of tested isolates), C. tropicalis (67% of tested isolates), and C. parapsilosis (57% of tested isolates) biofilms. One important limitation of our study was the low number of isolates tested. This limitation could influence the detection of PG for the different species, as observed in our study for C. parapsilosis.

In this study, we used SEM to visualize morphological changes associated with preformed Candida biofilms after exposure to CAS. The efficacy of 1 μg/ml CAS was confirmed by SEM for sessile cells of C. tropicalis and C. albicans. We showed that 16 μg/ml CAS causes significant alterations in the morphologies of preformed C. albicans and C. tropicalis biofilms, with the presence of enlarged blastospores, aberrant cells, and fewer hyphae. The preparation of samples for SEM involves fixation in an aldehyde, graded dehydration steps, and critical-point drying. This dehydration processing will alter the extracellular polymeric substance matrix of the biofilm (31, 45) when samples are exposed to a vacuum during examination. The appearance of collapsed cells, especially in C. albicans and C. tropicalis biofilms treated with 1 or 16 μg/ml of CAS, suggests an altered cell wall structure that is more susceptible to the destructive effects of SEM processing. Transmission electron microscopic examination of treated and untreated cell walls would be required to ascertain this effect.

Biofilm morphological changes associated with PG have been described for Candida sp. isolates previously (37); however, to our knowledge, this study provides the first detailed SEM image analysis of PG of C. albicans and C. tropicalis biofilms adherent to biomaterial disks. Our results also show that at least a percentage of cells in the biofilm maintain viability even in the presence of high concentrations (128 μg/ml) of CAS. There are four plausible explanations for this finding: (i) there is an abundance of biofilm production, and such cells may be shifting their metabolism away from regular functions (54, 56); (ii) the biofilm consists of a heterogeneous population with different growth rates, and therefore a subpopulation of cells could also confer antifungal resistance due to its lower growth rate (32, 38); (iii) there are problems with drug solubility at high CAS concentrations; (iv) the biofilm contains persister cells (phenotypic variants of the wild type rather than mutants) that are able to survive despite the presence of antibiotics at concentrations well above the MIC (34).

Studies of Candida albicans biofilm formation have previously described the presence of persister cells after exposure to various antifungal drugs (29, 34). Persisters were originally described as dormant, slowly growing, or nongrowing cells (26, 35) but are now recognized as drug-tolerant cells that neither grow nor die in the presence of microbicidal antibiotics. In this study, we observed the presence of sessile-cell subpopulations of C. albicans and C. tropicalis that displayed a pattern of tolerance to CAS and were associated with morphologically aberrant forms at 16 μg of the drug. Interestingly, at 128 μg of CAS, the same fungal species displayed biofilms similar in structure to control biofilms. However, similar patterns were not observed when we compared the viable cell counts and the low XTT activity results of the biofilms exposed to this drug concentration versus the controls. These observations may suggest a species-specific phenomenon of “dormancy” in the presence of high CAS concentrations. Further studies to determine whether this is the case are warranted.

CAS belongs to the echinocandin family and represents the newest class of antifungal drugs that inhibit the synthesis of β-1,3-glucan, a fundamental component of the fungal cell wall, by the inhibition of β-1,3-glucan synthase, an enzyme complex that forms glucan polymers in the cell wall (13, 18, 25). Interestingly, C. albicans biofilm cell walls contain significantly higher concentrations of β-1,3-glucan than their planktonic counterparts, and these glucans can be found in the supernatant surrounding the biofilm and in the matrix (41). The echinocandins and the lipid formulations of AMB have also been shown to display activity against Candida species biofilms (29, 38, 47). One explanation for the possible correlation between PG and yeast morphology changes has been presented by Stevens and colleagues (53). These researchers quantified β-1,3-glucan, β-1,6-glucan, and chitin, after exposure to high CAS concentrations, in a C. albicans strain for which the PG effect had previously been demonstrated. Whereas both the β-1,3-glucan and the β-1,6-glucan content declined relative to those of the control (untreated cells), chitin concentrations increased significantly after drug exposure. This would suggest that CAS exposure affects cell wall composition, which in turn alters morphology. Others mechanisms that have been suggested to explain PG include an involvement of the calcineurin pathway and upregulation of the protein kinase C cell wall integrity pathway (54, 56). The explanations for the attenuation of CAS activity in non-C. albicans species biofilm cells in vitro remain largely unknown.

From the clinical perspective, there are no published data that clearly demonstrate the PG effect in the treatment of candidemia and invasive Candida infections (56). However, one potential clinical application could be the limited use of CAS in antimicrobial lock therapy. The antibiotic lock technique was developed as a means to overcome the high-grade antimicrobial resistance observed for microbial biofilms and consists of filling a central venous catheter lumen with a high concentration of an antibiotic solution in order to salvage the device (9). Few studies have evaluated the efficacy of new antifungal drugs with antibiofilm activity against biofilm-encased organisms in catheters by lock therapy (10, 49, 52). Possible correlations between the concentration of CAS and its impact on lock therapy strategies should be investigated.

In conclusion, our results confirmed that therapeutic concentrations of CAS display potent in vitro activity against C. albicans and C. tropicalis biofilm and planktonic cells. PG was confirmed and associated with changes in specific biofilm cell morphologies. Finally, further work involving in vitro and in vivo experiments is needed in order to determine the validity of our observations.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge E. Perez, M. Williams, and T. Forster (Biofilm Laboratory, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) for their hard work and valuable input and/or technical support. We also thank Naureen Iqbal and J. Frade (Mycotic Diseases Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) for assistance with the planktonic and sessile susceptibility testing assays. We thank D. Warnock, Fred Tenover, J. Patel, R. Carey, J. Chandra, T. Walsh, and M. Arduino for stimulating discussions.

This work was supported in part by a research grant from the Investigator-Initiated Studies Program of Merck & Co., Inc., and by a grant from the CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, Brazil).

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not constitute endorsement by the Public Health Service or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Merck & Co., Inc.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 June 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andes, D., J. Nett, P. Oschel, R. Albrecht, K. Marchillo, and A. Pitula. 2004. Development and characterization of an in vivo central venous catheter Candida albicans biofilm model. Infect. Immun. 72:6023-6031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachmann, S. P., K. VandeWalle, G. Ramage, T. F. Patterson, B. L. Wickes, J. R. Graybill, and J. L. López-Ribot. 2002. In vitro activity of caspofungin against Candida albicans biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3591-3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baillie, G. S., and L. J. Douglas. 1998. Effect of growth rate on resistance of Candida albicans biofilms to antifungal agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1900-1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baillie, G. S., and L. J. Douglas. 1999. Role of dimorphism in the development of Candida albicans biofilms. J. Med. Microbiol. 48:671-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baillie, G. S., and L. J. Douglas. 2000. Matrix polymers of Candida biofilms and their possible role in biofilm resistance to antifungal agents. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:397-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee, S. N., T. G. Emori, D. H. Culver, R. P. Gaynes, W. R. Jarvis, T. Horan, J. R. Edwards, J. Tolson, T. Henderson, W. J. Martone, et al. 1991. Secular trends in nosocomial primary bloodstream infections in the United States, 1980-1989. Am. J. Med. 91(3B):S86-S89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blankenship, J. R., and A. P. Mitchell. 2006. How to build a biofilm: a fungal perspective. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:588-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calderone, R. A. 2002. Introduction and historical perspectives, p. 3-13. In R. A. Calderone (ed.), Candida and candidiasis. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 9.Carratalà, J. 2002. The antibiotic-lock technique for therapy of ‘highly needed’ infected catheters. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 8:282-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cateau, E., M. H. Rodier, and C. Imbert. 2008. In vitro efficacies of caspofungin or micafungin catheter lock solutions on Candida albicans biofilm growth. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:153-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandra, J., P. K. Mukherjee, S. D. Leidich, F. F. Faddoul, L. L. Hoyer, L. J. Douglas, and M. A. Ghannoum. 2001. Antifungal resistance of candidal biofilms formed on denture acrylic in vitro. J. Dent. Res. 80:903-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cocuaud, C., M. H. Rodier, G. Daniault, and C. Imbert. 2005. Anti-metabolic activity of caspofungin against Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis biofilms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:507-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denning, D. W. 2002. Echinocandins: a new class of antifungal. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:889-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donlan, R. M. 2001. Biofilms and device-associated infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:277-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donlan, R. M., and J. W. Costerton. 2002. Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:167-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Douglas, L. J. 2002. Medical importance of biofilms in Candida infections. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 19:139-143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edmond, M. B., S. E. Wallace, D. K. McClish, M. A. Pfaller, R. N. Jones, and R. P. Wenzel. 1999. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in United States hospitals: a three-year analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:239-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Georgopapadakou, N. H. 2001. Update on antifungals targeted to the cell wall: focus on β-1,3-glucan synthase inhibitors. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 10:269-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gudlaugsson, O., S. Gillespie, K. Lee, J. Vande Berg, J. Hu, S. Messer, L. Herwaldt, M. A. Pfaller, and D. Diekema. 2003. Attributable mortality of nosocomial candidemia, revisited. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37:1172-1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawser, S. P., and L. J. Douglas. 1995. Resistance of Candida albicans biofilms to antifungal agents in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2128-2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawser, S. P., H. Norris, C. J. Jessup, and M. A. Ghannoum. 1998. Comparison of a 2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino)carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium hydroxide (XTT) colorimetric method with the standardized National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards method of testing clinical yeast isolates for susceptibility to antifungal agents. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1450-1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hobson, R. P. 2003. The global epidemiology of invasive Candida infections—is the tide turning? J. Hosp. Infect. 55:159-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin, Y., H. K. Yip, Y. H. Samaranayake, J. Y. Yau, and L. P. Samaranayake. 2003. Biofilm-forming ability of Candida albicans is unlikely to contribute to high levels of oral yeast carriage in cases of human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2961-2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katragkou, A., A. Chatzimoschou, M. Simitsopoulou, M. Dalakiouridou, E. Diza-Mataftsi, C. Tsantali, and E. Roilides. 2008. Differential activities of newer antifungal agents against Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:357-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kauffman, C. A., and P. L. Carver. 2008. Update on echinocandin antifungals. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 29:211-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keren, I., D. Shah, A. Spoering, N. Kaldalu, and K. Lewis. 2004. Specialized persister cells and the mechanism of multidrug tolerance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186:8172-8180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim, R., D. Khachikia, and A. C. Reboli. 2007. A comparative evaluation of properties and clinical efficacy of the echinocandins. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 8:1479-1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kojic, E. M., and R. O. Darouiche. 2004. Candida infections of medical devices. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:255-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuhn, D. M., T. George, J. Chandra, P. K. Mukherjee, and M. A. Ghannoum. 2002. Antifungal susceptibility of Candida biofilms: unique efficacy of amphotericin B lipid formulations and echinocandins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1773-1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuhn, D. M., J. Chandra, P. K. Mukherjee, and M. A. Ghannoum. 2002. Comparison of biofilms formed by Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis on bioprosthetic surfaces. Infect. Immun. 70:878-888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuhn, D. M., and M. A. Ghannoum. 2004. Candida biofilms: antifungal resistance and emerging therapeutic options. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 5:186-197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumamoto, C. A. 2002. Candida biofilms. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:608-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumamoto, C. A. 2008. Molecular mechanisms of mechanosensing and their roles in fungal contact sensing. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:667-673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LaFleur, M., C. Kumamoto, and K. Lewis. 2006. Candida albicans biofilms produce antifungal-tolerant persister cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3839-3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis, K. 2007. Persister cells, dormancy and infectious disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:48-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mateus, C., S. A. Crow, Jr., and D. G. Ahearn. 2004. Adherence of Candida albicans to silicone induces immediate enhanced tolerance to fluconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3358-3366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melo, A. S., A. L. Colombo, and B. A. Arthington-Skaggs. 2007. Paradoxical growth effect of caspofungin observed on biofilms and planktonic cells of five different Candida species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3081-3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mukherjee, P. K., and J. Chandra. 2004. Candida biofilm resistance. Drug Resist. Updat. 7:301-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mukherjee, P. K., J. Chandra, D. M. Kuhn, and M. A. Ghannoum. 2003. Mechanism of fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans biofilms: phase-specific role of efflux pumps and membrane sterols. Infect. Immun. 71:4333-4340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2002. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeast. Approved standard M27-A2. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 41.Nett, J., L. Lincoln, K. Marchillo, R. Massey, K. Holoyda, B. Hoff, M. VanHandel, and D. Andes. 2007. Putative role of β-1,3 glucans in Candida albicans biofilm resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:510-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ostrosky-Zeichner, L., J. H. Rex, P. G. Pappas, R. J. Hamill, R. A. Larsen, H. W. Horowitz, W. G. Powderly, N. Hyslop, C. A. Kauffman, J. Cleary, J. E. Mangino, and J. Lee. 2003. Antifungal susceptibility survey of 2,000 bloodstream Candida isolates in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3149-3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perumal, P., S. Mekala, and W. L. Chaffin. 2007. Role for cell density in antifungal drug resistance in Candida albicans biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2454-2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pfaller, M. A., and D. J. Diekema. 2007. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20:133-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramage, G., K. Vande Walle, B. L. Wickes, and J. L. Lopez-Ribot. 2001. Biofilm formation by Candida dubliniensis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3234-3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramage, G., S. Bachmann, T. F. Patterson, B. L. Wickes, and J. L. Lopez-Ribot. 2002. Investigation of multidrug efflux pumps in relation to fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans biofilms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:973-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramage, G., K. VandeWalle, S. P. Bachmann, B. L. Wickes, and J. L. López-Ribot. 2002. In vitro pharmacodynamic properties of three antifungal agents against preformed Candida albicans biofilms determined by time-kill studies. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3634-3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramage, G., B. L. Wickes, and J. L. Lopez-Ribot. 2001. Biofilms of Candida albicans and their associated resistance to antifungal agents. Am. Clin. Lab. 20:42-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schinabeck, M. K., L. A. Long, M. A. Hossain, J. Chandra, P. K. Mukherjee, S. Mohamed, and M. A. Ghannoum. 2004. Rabbit model of Candida albicans biofilm infection: liposomal amphotericin B antifungal lock therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1727-1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seneviratne, C. J., L. Jin, and L. P. Samaranayake. 2008. Biofilm lifestyle of Candida: a mini review. Oral Dis. 14:582-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seneviratne, C. J., L. J. Jin, Y. H. Samaranayake, and L. P. Samaranayake. 2008. Cell density and cell aging as factors modulating antifungal resistance of Candida albicans biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3259-3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shuford, J. A., M. S. Rouse, K. E. Piper, J. M. Steckelberg, and R. Patel. 2006. Evaluation of caspofungin and amphotericin B deoxycholate against Candida albicans biofilms in an experimental intravascular catheter infection model. J. Infect. Dis. 194:710-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stevens, D. A., M. Espiritu, and R. Parmar. 2004. Paradoxical effect of caspofungin: reduced activity against Candida albicans at high drug concentrations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3407-3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stevens, D. A., M. Ichinomiya, Y. Koshi, and H. Horiuchi. 2006. Escape of Candida from caspofungin inhibition at concentrations above the MIC (paradoxical effect) accomplished by increased cell wall chitin: evidence for β-1,6-glucan synthesis inhibition by caspofungin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3160-3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watnick, P., and R. Kolter. 2000. Biofilm, city of microbes. J. Bacteriol. 182:2675-2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wiederhold, N. P. 2007. Attenuation of echinocandin activity at elevated concentrations: a review of the paradoxical effect. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 20:574-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]