Abstract

Drawing on a normative sample of 224 youth and their biological mothers, this study tested 4 family variables as potential mediators of the relationship between maternal depressive symptoms in early childhood and child psychological outcomes in preadolescence. The mediators examined included mother–child communication, the quality of the mother–child relationship, maternal social support, and stressful life events in the family. The most parsimonious structural equation model suggested that having a more problematic mother–child relationship mediated disruptive behavior-disordered outcomes for youths, whereas less maternal social support mediated the development of internalizing disorders. Gender and race were tested as moderators, but significant model differences did not emerge between boys and girls or between African American and Caucasian youths.

During the school-age years, children of depressed parents,1 as compared with children of parents without a psychiatric history, have been found to have a range of negative outcomes spanning psychiatric, social, and health domains. Such outcomes include higher levels of internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Billings & Moos, 1983), more psychiatric disorder (Beardslee et al., 1988; Weissman et al., 1987), poorer physical health, and greater deficits in academic, intellectual, and social and emotional competence (C. A. Anderson & Hammen, 1993; Goodman, Brogan, Lynch, & Fielding, 1993; Kaplan, Beardslee, & Keller, 1987; Weissman et al., 1987). Some researchers have found parental depression to be more important than such family risk factors as parent–child discord, low family cohesion, and poor marital adjustment in predicting later child psychopathology (Fendrich, Warner, & Weissman, 1990). Overall, having a depressed parent appears to increase a child’s general risk for psychopathology and specific risk for depression (Beardslee et al., 1988; Beardslee, Versage, & Gladstone, 1998; Downey & Coyne, 1990), although many children from at-risk environments, including those with depressed parents, do not develop adjustment problems. Risk of adjustment problems for children of parents with subclinical depressive symptoms appears to be somewhat tempered in comparison with risk for children of clinically depressed parents (Forehand, McCombs, & Brody, 1987) but is still elevated compared with children of nonsymptomatic parents.

A somewhat separate line of research has examined differences in parenting and interactional styles among depressed mothers or mothers with depressive symptoms compared with nondepressed mothers. Depressed mothers are less able to function adaptively with their children and tend to interact in a more negative and controlling fashion (Burbach & Borduin, 1986; Gelfand & Teti, 1990) than other mothers. Their behavior toward their children has been characterized both as more negative and less positive (Gordon et al., 1989), and their affect is more dysphoric and less happy (Hops et al., 1987). A recent review pointed to the need to identify processes and mechanisms that may account for elevated risk in children of depressed parents. Goodman and Gotlib (1999) outlined four possible mechanisms: (a) genetic heritability, (b) innate dysfunctional neuroregulatory mechanisms, (c) exposure to negative maternal behavior and affect, and (d) the context of the lives of children in the families of depressed mothers. Despite growing theory postulating processes that may be involved in increased risk, only a handful of studies have been conducted to demonstrate whether some or all of these or other mechanisms predict subsequent psychopathology in relation to maternal depression or depressive symptoms (e.g., Davies, Dumenci, & Windle, 1999; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Early Child Care Research Network, 1999; Teti & Gelfand, 1997).

The current study examined four different psychosocial mediators to determine whether they predicted children’s later diagnoses as a function of maternal depressive symptoms. The mediators chosen for this study were based on the two broad psychosocial mechanisms posited by Goodman and Gotlib (1990) to contribute to children’s risk for depression (i.e., exposure to negative maternal behavior, cognition, and affect and the context of the lives of children in the families of depressed mothers). We examined two different aspects of negative maternal behavior and affect specifically in the context of the mother–child dyad: communication and the relationship quality. Depressive symptoms may interfere with a mother’s ability to be an adequate social partner for the child and to meet his or her social and emotional needs. Maternal symptoms may thus influence mothers’ availability for communication and/or the affective bond between mothers and children. The context of children’s lives is the second broad psychosocial risk mechanism. In particular, Goodman and Gotlib implicate the role of stress. We examined two mediators in the area of family context: maternal social support and stressful life events. Maternal social support is indicative of the social resources that the mother accesses in times of need. It both provides a model of interpersonal relations for children to observe and influences mothers’ sensitivity and receptivity as a supportive resource to their children. Stress is another aspect of the family context that is likely to be heightened among children of mothers with depressive symptoms. Prior to the development of depression or conduct disorder, youth have been found to report the presence of more stressful life events (Goodyer, Wright, & Altham, 1988; Hastings, Anderson, & Kelley, 1996).

We chose to study mediation as youth transition into early adolescence (Grades 5–6, as defined by Forehand, Neighbors, & Wierson, 1991), This age period was chosen in part because it marks a time of change and transition that can negatively influence individuals (Simmons, Burgeson, Carlton-Ford, & Blyth, 1987) and is associated with an increase in problems (Petersen & Hamburg, 1986). During adolescence, youth adapt to numerous psychological, physical, cognitive, and social changes, with the period of preadolescence often marking the beginning of radical change. Early adolescence also marks a time point at which youth are more vulnerable to stressors (Wierson & Forehand, 1992) and parental communication and problem solving have an important impact on the functioning of youth (Montemayor, 1986).

The first proposed mediator in this study is mother–child communication. Parents play a pivotal role in their children’s social and emotional competence by coaching, teaching, and nurturing developing skills (e.g., Parke, MacDonald, Beitel, & Bhavnagri, 1988). Communication forms a cornerstone for parents’ ability to attend to their children’s needs and feelings during preadolescence (Montemayor, 1986), given that the parent’s role as social partner to a child includes providing general social support and stress buffering during this developmental period (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999). A number of studies examining family communication and child outcome suggest that less frequent and lower quality of communication is a significant risk for child psychopathology (Slesnick & Waldron, 1997) and that parental depressive symptoms are related to more impaired communication (Albright & Tamis-LeMonda, 2002; Jacob & Johnson, 1997, 2001). Moreover, a longitudinal study from the Isle of Wight sample suggests that lack of parent–child communication at age 10 was predictive of depression 20 years later (Lindeloew, 1999). Children who are unable to garner emotional coaching or problem solving around conflicts they are experiencing due to unavailability or lack of good communication with their parents may be more likely to act out or feel overwhelmed by their problems, resulting in more internalizing and externalizing problems. Conversely, early elementary school-age children with parents who provide more emotional coaching have fewer behavioral problems (Hooven, Gottman, & Katz, 1995).

A second mediator that was tested is the overall quality of the mother–child relationship. Among infants, maternal sensitivity has been found to both mediate and moderate the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and children’s behavior and cognitive outcomes at age three (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Early Child Care Research Network, 1999). There is also evidence suggesting that maternal depression or depressive symptoms may influence mother–child attachment (Cicchetti, Toth, & Lynch, 1995). The analogous construct appropriate to children in preadolescence is the quality of the parental relationship. Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that youngsters with positive family relationships are less likely to become depressed (Petersen, Sarigiani, & Kennedy, 1991; Reinherz et al., 1993). Mothers who are depressed or have depressive symptoms may be less able to devote their time and energy to developing positive relationships with their children. They may also view their children in a more critical and negative light (Goodman, Adamson, Riniti, & Cole, 1994; Webster-Stratton & Hammond, 1988). Children who feel less close to their mothers may be less likely to internalize their standards for behavior, which may in turn interfere with their ability to control their behavior, thereby resulting in more externalizing problems (Stice, Barrera, & Chassin, 1993). Likewise, children who do not view their mothers as supportive persons on whom they can depend may develop feelings of insecurity and inadequacy, leading to vulnerability toward internalizing problems.

The third proposed mediator is maternal social support. Literature on the interpersonal aspects of depression continues to show that being around depressed persons is aversive for most people (Benazon & Coyne, 2000; Bieling & Alden, 2001; Strack & Coyne, 1983). Although depressed persons initially elicit nurturance and support from people in their social network, they later elicit hostility, resentment, and irritation for their self-absorption and help-seeking behavior (e.g., Segrin & Abramson, 1994). This suggests that depressed mothers and mothers with depressive symptoms, are likely to experience rejection and to have less social support. Without their own supportive network of adults, these mothers may be less able to focus on their children’s needs and may utilize their children for support. In the literature on socially isolated “insular mothers,” less frequent social contact is related to children’s oppositional problems, perhaps because these mothers generalize from their chaotic, crisis-ridden daily lives and interact with their children in conflictual and coercive ways (Wahler, 1990). Moreover, youngsters who observe mothers without supportive networks of their own may acquire maladaptive interpersonal skills and have difficulties in their own relationships (Hammen & Brennan, 2001).

Stressful life events constitute the fourth mediator included in the hypothesized model Stress can be viewed as both a precipitant and a consequence of depression. Depressed persons certainly have more stressful lives and more marital conflict (see Downey & Coyne, 1990, for review) and may generate stressful life events as a result of their negative interpersonal cognitions (Hammen, 1991b), As a result, their children are likely to also be exposed to, and to experience, more stressful life events (Adrian & Hammen, 1993). Childhood adversities have been found to have very strong effects on the first onset of depression (Kessler & Magee, 1993; Loss, Beck, & Wallace, 1995; Tisher, Tonge, & Home, 1994). Experiencing highly stressful events is also associated with youth externalizing behaviors. Exposure to malevolent environmental factors and traumatic life events is common among serious adolescent offenders (Erwin, Newman, McMackin, Morrissey, & Kaloupek, 2000). Stressful events are also correlated with youth’s alcohol consumption (Scheier, Botvin, & Miller, 2000). Thus, experiencing more stressful life events may be predictive of the development of either internalizing or externalizing problems for youth with mothers who have elevated depressive symptoms.

We also examined whether different mediators were predictive of later child depression and other internalizing problems versus other child outcomes, such as disruptive behavior disorders.2 Higher rates of both internalizing and externalizing problems have been documented among children of depressed mothers (Hammen, 1991a; Lee & Gotlib, 1989), yet the differentiation of these developmental outcomes for children of depressed mothers has largely been ignored. A few studies have examined the characteristics of competent children of depressed parents (Beardslee & Podorefsky, 1988; Garber & Little, 1999), finding that the children’s social support, family relationships, coping, and commitment to achievement are important in predicting resiliency. A study with high school–age adolescents found that marital quality mediated the effects of maternal depressive symptoms on adolescent externalizing problems, whereas maternal depressive symptoms mediated the effects of marital quality on adolescent depression (Davies et al., 1999). The current study examined mediation for two types of diagnoses, assessing the same four factors as mediators of the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and youth’s anxiety/depression and as mediators of the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and youth’s disruptive behavior disorders.

In sum, although there is theoretical and empirical support for these four mediators of the relationship between maternal depressive symptoms and child psychopathological outcomes, such a model has not been tested comprehensively in a sample of youth followed longitudinally. Furthermore, the differential prediction of child internalizing and disruptive behavior disorders as they relate to maternal depression and parenting factors has not previously been examined. This study offers both analyses by examining maternal depressive symptoms and mediators of child internalizing and disruptive behavior disorders in a normative sample. In addition, we examined youth gender and race as potential moderators.

Some research suggests that girls and boys may be affected by maternal depression differently, with girls being more vulnerable to developing depression (Hops, 1996; O’Connor & Kasari, 2000) and boys more prone to conduct or externalizing problems (Cummings & Davies, 1994). Rutter (1990) has advanced the notion that family processes may differ according to youth gender, with depressed mothers potentially seeking comfort from their daughters and boys being exposed to more negativity and discord in the family. However, data with respect to gender-linked vulnerabilities and differences are mixed and do not provide consistent findings (see Cummings & Davies, 1994, for further discussion).

Previous research examining children of depressed mothers and children of mothers with depressive symptoms is limited in that most samples have consisted primarily of families with European American backgrounds. Our sample provides a unique opportunity to examine whether the same variables mediate risk among African American and Caucasian youth. A previous study conducted with this same sample in the first grade found that level of maternal depressive symptoms was not related to the quality of mother–child interaction among African Americans but that it was for Caucasians (Harnish, Dodge, Valente, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1995), suggesting that associations may differ as a function of race. In examining race, we held constant the geographical context in which the youth lived (by excluding those from rural environments), as the amount and impact of certain parental behaviors, such as monitoring, on children’s behavior problems has been found to differ depending on context (Armistead, Forehand, Brody, & Maguen, 2002; Forehand et al, 2000). It is possible that other parenting and family factors, such as maternal social support, would have a different impact on child psychopathology in rural versus urban settings, where availability of resources and access to social networks differs greatly. Because race was confounded with study site in our sample, we examined racial and geographical differences by evaluating urban Caucasians in comparison with urban African American youth from our two racially diverse sites only.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 224 youth and their biological mothers, who were part of a normative, nonintervention sample from a larger longitudinal study (Fast Track; Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1992, 2000) examining the development and prevention of conduct problems among children. Participants were selected from four different areas of the country, each representing a different cross-section of the U.S. population: Durham, North Carolina; Nashville, Tennessee; Seattle, Washington; and rural central Pennsylvania. The original normative sample (N = 387) was selected for the Fast Track study by including 10 children per site at each decile of the distribution of scores on a teacher-report screen for behavior problems (Teacher Observation of Child Adaptation—Revised; Werthamer-Larsson, Kellam, & Wheeler, 1991) in kindergarten. For the present study, only those youth who were interviewed with their biological mothers at each of the five measurement points (spanning 7 years) were included, which eliminated 92 children (24%) of the original sample from analyses. An additional 71 children (18%) were lost to attrition, as they were missing data at one or more of the assessments.

The final sample included 105 boys and 119 girls, with 41% (n = 92) African American, 57% (n = 128) Caucasian, and 2% other minority ethnic background. Approximately 40% of the sample consisted of single-parent families, and the mean socioeconomic status of these families according to the Hollingshead (1979) categorization system was 27 with a standard deviation of 14. This level of socioeconomic status is considered to be working class and includes semiskilled workers such as machinists. As determined with t tests comparing the analyzed and the attrited samples, the two did not differ along the following baseline measures: maternal depression, t(293) = −0.60, p =.55; socioeconomic status, t(293) = −0.38, p =.71; early internalizing scores, t(293) = −0.77, p = .44; or early externalizing scores, t(293) = −1.79, p = .07. Moreover, the percentage of single-parent families did not differ in the analyzed and attrited samples χ2(1, N = 295) = 0.03, p = .85.

Procedure

Although comprehensive assessments were conducted annually beginning in kindergarten as part of the larger Fast Track project, only those procedures and measures relevant to the current study are described here. Data were obtained from the children and their mothers during annual interviews conducted each summer by separate interviewers. While one research assistant interviewed the primary caregiver (in this study, the mother), a second assistant interviewed the child in a separate room. Interviewers read the various measures to the mothers and children and recorded their responses. The data in this study are based on child and mother reports as well as interviewer ratings.

Maternal depressive symptoms were assessed in Years 1 through 3 of the study, when the majority of the youth had finished kindergarten, Grade 1, and Grade 2. Early child internalizing and externalizing problems were assessed in Years 1 and 3 of the study, corresponding to the summers following kindergarten and Grade 2. The measures used to construct the mediational variables were administered in Year 6 of the study, when the youth were approximately 11 years of age and the majority had completed Grade 5. Measures of child diagnostic outcomes were collected in Year 7, when the youths were approximately 12 years of age and the majority had completed Grade 6.

Measures

Maternal depressive symptoms

Mothers were administered the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) for 3 consecutive years (Grades K, 1, and 2), with each time point used as an indicator of a latent variable of maternal depressive symptoms. The CES-D has demonstrated high internal consistency (ranging from .84 to .90 across four different samples) as well as adequate discriminant validity (Radloff, 1977). The percentage of mothers scoring above the clinical cutoff of 16 was 37% at the kindergarten assessment, 22% at the Grade 1 assessment, and 18% at the Grade 2 assessment. Fifty percent of mothers (n = 111) met clinical cutoff for at least one of the three time points, and 30% (n = 23) met the criteria at all three assessment periods.

Early child internalizing and externalizing problems

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), a widely used, standardized parent-report measure that lists 118 child behavior problems for parents to rate as not true, somewhat/sometimes true, or very/often true was administered to mothers in the summers following kindergarten and Grade 2. Evidence on the reliability and validity of these scores is extensive (Achenbach, 1991). The CBCL generates raw and T scores for the broadband dimensions of internalizing and externalizing problems. T scores from kindergarten and second-grade assessments were averaged within these broadband syndromes and used as measures of early internalizing and externalizing problems.

Mother–child communication

Three scales were used as indicators of the latent mother–child communication variable. Both mothers and their children completed modified versions of the Parent–child Communication Scale, which was adapted for Fast Track from the Revised Parent–Adolescent Communication Form used in the Pittsburgh Youth Study (see Loeber, Farrington, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Van Kammen, 1998; Thornberry, Huizinga, & Loeber, 1995). Reports on the parent communication scale, which assesses parents’ openness to communication with their child (e.g., “Do you discuss child-related problems with your child?”) were obtained from both informants. Both the parent and the child versions of the scale consist of five items that are rated on a 5-point scale. These scales have adequate internal consistency in this sample (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = .70 for parent and .70 for child).

The third indicator was the Positive Communication scale from the People in My Life measure, which is a 30-item youth-report instrument designed to measure parent–child relationships in middle childhood, derived from a longer instrument (see Cook, Greenberg, & Kusche, 1995). The Positive Communication scale consists of six items that specifically assess positive aspects of parent–child communication (e.g., “My parents listen to what I have to say”), rated on 4-point scales, with higher scores indicating more frequent communication. Coefficient alpha for this scale was .81.

Mother–child relationship

Mothers and interviewers were each asked to rate the mother–child relationship during the interview, and these 5-point ratings were used as indices of a latent mother–child relationship variable. Mothers were asked to rate how well they get along with their children on a scale ranging from 1 (lots of difficulties) to 5 (very well). Subsequent to spending 2 hr. interviewing the mothers, observing parent–child interactions, and hearing mothers describe their child and their relationship, interviewers rated the mother–child relationship on a scale ranging from 1 (cold, hostile) to 5 (extremely warm, very nurturing). The two items were moderately correlated (r = .43) in this sample.

Maternal social support

Social support was assessed by four subscales from the 38-item Inventory of Parent Experiences (IPE; Crnic & Greenberg, 1990): Friendship Support, Family Support, Community Support, and Parenting Support, which were used as indicators of the latent maternal social support variable. Example items from these four areas include “How satisfied are you with the amount of phone contact you have with friends?” (Friendship Support), “How satisfied are you with the amount of help family members provide?” (Family Support), “How satisfied are you with your involvement in your neighborhood?” (Community Support), and “How satisfied are you with the availability of people to talk to if you were to have bad or angry feelings about your child?” (Parenting Support), Alpha coefficients for these subscales were .82, .75, .62, and .77, respectively.

Stressful life events

A measure of stressful life events was obtained by the total score on the Life Changes instrument, which is a 16-item parent report measure that assesses major life stressors experienced by the child during the previous year (e.g., move, medical problems, divorce or separation of parents, death of an important person). Each item is weighted 2 for major events and 1 for minor events and is based on parental report of the severity of the event for the family.

Child outcome

Youth and their mothers were separately administered computerized versions of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000). We combined individual diagnoses between informants using an “or” algorithm such that if a diagnosis was obtained from either the child or the maternal report, it was considered to be present (Piacentini, Cohen, & Cohen, 1992). Thus, our outcome measures were both dichotomous. The disruptive behavior disorder variable (0 = not present, 1 = present) was coded on the basis of the presence of either conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder. For the internalizing disorder variable, the coding was 0 = no internalizing disorder, 1 = meets diagnostic criteria for at least one internalizing disorder. Diagnoses of social phobia, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, or dysthymic disorder were considered to indicate the presence of an internalizing disorder. All diagnoses are based on DSM-IV criteria in accordance with DISC-IV scoring algorithms.

Results

Diagnostic Rates

Approximately 17% of the youth sample met criteria for a disruptive behavior disorder at Grade 6, and 17% met criteria for an internalizing disorder at that time point, according to either maternal or youth report. The breakdown of more specific diagnoses, and informants who reported them, is provided in Table 1. In general, the rates of disorder in this sample were low to moderate.

Table 1.

Percentage of Youths Meeting Internalizing or Disruptive Behavior Disorder Criteria, by Informant

| Disorder | Youth | Mother | Either |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disruptive behavior disorders | 7.4 | 10.6 | 16.7 |

| Conduct disorder | 4.6 | 3.7 | 7.8 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 3.2 | 8.2 | 11.0 |

| Internalizing disorders | 11.5 | 6.6 | 16.6 |

| Social phobia | 3.2 | 1.8 | 4.6 |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 4.6 | 2.3 | 6.9 |

| Panic disorder | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Agoraphobia | 5,0 | 0.0 | 5.0 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.4 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 0.9 | 1.4 | 2.3 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 1.8 | 0.0 | 1.8 |

| Major depressive disorder | 1.8 | 1.8 | 3.7 |

| Dysthymic disorder | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Analytical Plan

We tested our mediational model using structural equation modeling. We began analyses by testing a full model including the following four variables mediating the relationship between maternal depressive symptoms and child internalizing and disruptive behavior diagnoses: mother–child communication, mother–child relationship, maternal social support, and stressful life events. Nonsignificant paths were removed sequentially until the chi-square difference test between models was nonsignificant. Then the full model was tested for differences with respect to child gender and child race. The full model was used for tests of moderation because it is possible that small magnitude path coefficients in the overall model are the result of beta coefficients that differ in direction across different groups.

All structural equation modeling results were obtained by using the MPlus software (Muthen & Muthen, 1998). Estimates were obtained with the maximum likelihood procedure with the Satorra-Bentler scaled correction (Hu, Bentler, & Kano, 1992) because preliminary tests suggested there was some departure from the multivariate normality assumption. Robust z statistics, based on corrected standard errors, were used to assess parameter significance, and adjusted chi-square difference tests were used to test nested models (Satorra, 2000), Two different indices were used to assess overall model fit: (a) the comparative fit index (CFI, with values > .95 demonstrating good fit; Hu & Bentler, 1999) and (b) the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), with values less than .05 representing close fit and values in the range of .05 to .08 indicating fair fit (Browne & Cudek, 1993).

Measurement Model

Following the two-step approach to structural model testing recommended by J. C. Anderson and Gerbing (1988), we began by using confirmatory factor analysis to test whether our measurement model was acceptable.3 Our model included each of the latent variables and its indicators in one comprehensive model. Given the conceptual link between the mother–child relationship and mother–child communication, we included a covariance term between these two latent variables in all models. We assessed the measurement model by reviewing the magnitude and significance of the factor loadings, as well as both the CFI and RMSEA indices of model fit. Results of the analysis suggested that all criteria were satisfactory, as the model generated all significant factor loadings, with χ2(48, N = 231) = 71.58, p = .02, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .05. Correlations, means, and standard deviations for the observed variables included in the measurement and structural models are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Correlation. Coefficients, Means, and Standard Deviations for Observed Variables

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CES-D (K) | 13.712 | 9.524 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. CES-D (Grade 1) | 10.820 | 8.484 | .551 | |||||||||||||||

| 3. CES-D (Grade 2) | 9.973 | 7.407 | .473 | .520 | ||||||||||||||

| 4. PML Communication | 3.271 | 0.604 | −.125 | −.112 | −.080 | |||||||||||||

| 5. IPE Community Support | 1.959 | 0.701 | −.338 | −.291 | −.272 | .137 | ||||||||||||

| 6. IPE Friendship Support | 2.372 | 0.597 | −.363 | −.270 | −.262 | .099 | .520 | |||||||||||

| 7. IPE Family Support | 2.200 | 0.699 | −.292 | −.186 | −.199 | .188 | .288 | .400 | ||||||||||

| 8. IPE Parenting Support | 2.122 | 0.544 | −.327 | −.192 | −.250 | .224 | .477 | .529 | .420 | |||||||||

| 9. Stressful Life Events | 3.667 | 3.439 | .102 | .154 | .120 | −.046 | −.091 | −.112 | −.213 | −.133 | ||||||||

| 10. Mother–child communication (child) | 3.975 | 0.741 | −.178 | −.179 | −.079 | .647 | .076 | .081 | .106 | .184 | −.055 | |||||||

| 11. Mother–child communication (mother) | 4.040 | 0.589 | −.301 | −.180 | −.155 | .255 | .271 | .302 | .151 | .285 | −.082 | .193 | ||||||

| 12. Mother–child relationship (mother) | 4.396 | 0.793 | −.275 | −.213 | −.149 | .211 | .159 | .177 | .192 | .262 | −.195 | .228 | .313 | |||||

| 13. Mother–child relationship (interviewer) | 3.743 | 0.898 | −.185 | −.143 | −.124 | .205 | .080 | .134 | .218 | .177 | −.145 | .185 | .242 | .423 | ||||

| 14. DISC DBD (Grade 6) | 0.158 | 0.365 | .256 | .243 | .102 | −.065 | −.037 | −.111 | −.154 | −.135 | .197 | .008 | −.160 | −.295 | −.248 | |||

| 15. DISC Internalizing Disorders(Grade 6) | 0.167 | 0.374 | .145 | .098 | .092 | −.107 | −.216 | −.178 | −.065 | −.148 | −.002 | −.053 | −.219 | −.148 | −.128 | .238 | ||

| 16. Early Child Internalizing (K, Grade 2) | 52.588 | 9.140 | .282 | .332 | .307 | −.082 | −.174 | −.191 | −.115 | −.201 | .175 | −.017 | −.216 | −.255 | −.218 | .237 | .235 | |

| 17. Early Child Externalizing (K, Grade 2) | 53.993 | 9.688 | .348 | .393 | .330 | −.208 | −.087 | −.239 | −.186 | −.210 | .171 | −.083 | −.250 | −.356 | −.278 | .328 | .239 | .653 |

Note. Coefficients greater than ±.13 are significant (p < .05). Variables were assessed in Grade 5 unless otherwise noted, K = Kindergarten; CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression scale; PML = People in My Life; IPE = Inventory of Parent Experiences; DISC = Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children; DBD = disruptive behavior disorder.

Mediational Models

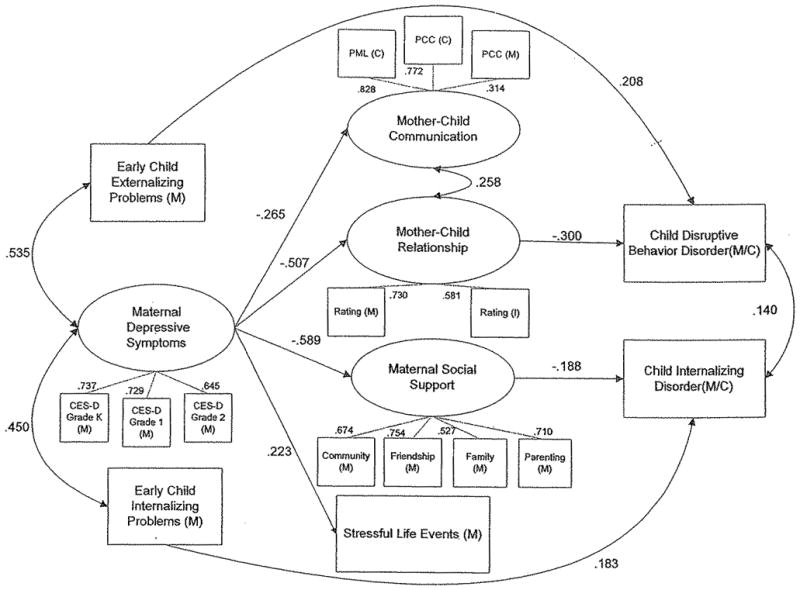

After confirming the presence of significant relationships between the predictor and the criteria, we conducted model tests of mediation. We began with a full model, which estimated paths from maternal depressive symptoms to the four mediators and from each of the four mediators to the two outcomes. The model also included direct paths from maternal depressive symptoms to child internalizing and child disruptive behavior diagnoses and from early child internalizing and externalizing symptoms to later internalizing disorders and disruptive behavior disorders. The model also allowed for the covariation of maternal depressive symptoms with early child internalizing and externalizing problems, as well as the covariation of child internalizing and disruptive behavior diagnoses at Grade 6. Using the full model as a starting point, we tested sequential models by removing paths with the smallest Wald statistic values one at a time, until the chi-square difference test between successive models was significant, suggesting that all paths were necessary in the model. Table 3 provides information about this model-pruning process, including which paths were removed and chi-square values for each of the models. The final model (shown in Figure 1) included the mother–child relationship as a mediator of child disruptive behavior disorders and maternal social support as a mediator of child internalizing diagnoses. It also included direct paths between early child externalizing problems and later disruptive behavior disorders and between early child internalizing problems and later internalizing diagnoses. This model showed a good fit with the data, χ2(111, N = 222) = 134.62, p = .06, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .03.

Table 3.

Evolution of Structural Equation Models From the Full Model to the Most Parsimonious Model

| Model | Path to be removed | t value of path (path coefficient)a | Chi-square value | df | χ2 changeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full model | Mother–child communication to internalizing | −0.40 (−.04) | 124.50 | 103 | |

| Model 2 | Maternal depressive symptoms to internalizing | −0.45 (−.07) | 124.54 | 104 | 0.04 |

| Model 3 | Social support to DBD | 0.93 (.08) | 124.66 | 105 | O.11 |

| Model 4 | Maternal depressive symptoms to DBD | 0.80 (.09) | 125.52 | 106 | 0.77 |

| Model 5 | Mother–child relationship to internalizing | −1.38 (−.11) | 126.33 | 107 | 0.72 |

| Model 6 | Mother–child communication to DBD | 1.52 (.14) | 127.81 | 108 | 1.32 |

| Model 7 | Stressful Life Events to internalizing | −1. 23 (−.07) | 130.10 | 109 | 2.05 |

| Model 8 | Stressful Life Events to DBD | 1.96 (.12) | 131.36 | 110 | 1.13 |

| Final model | None | 134.62 | 111 | 2.92 |

Note. DBD = disruptive behavior disorder

Refers to standardized path coefficient prior to its removal from the overall model.

Chi-square change values are based on the corrected values due to use of the Satorra-Bentler scaled statistic.

Figure 1.

Final mediational model testing child outcomes as a function of maternal depressive symptoms. Coefficients are standardized path coefficients, all of which are significant at p < .05. Curved lines with double-headed arrows represent covariances between latent variables. Dashed lines represent indicators of latent variables. The person completing the measure is depicted by M = Mother, C = Child, I = Interviewer, CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression; PML = People in My Life; PCC = Parent–Child Communication.

Moderation by Gender and Race

Gender

We assessed mean differences between girls and boys (and their mothers) on each of the observed variables using independent t tests for all continuous mediators and chi-square tests for diagnostic outcomes. The Satterthwaite correction for degrees of freedom was used for t tests when variances were statistically inequivalent. Two differences emerged. Mothers of boys reported significantly more depressed mood in kindergarten (M = 14.83, SD = 10.39) compared with mothers of girls (M = 12.25, SD = 8.44), t(208) = 2.05, p = .04. Also, a higher proportion of boys evidenced disruptive behavior disorders (25%) compared with girls (9%), χ2(1, N = 215) = 10.03, p = .001. To test whether child gender moderated the relationships hypothesized in our full model, we divided the sample into two groups on the basis of child gender and compared a structural model that allowed parameter estimates to differ in the two groups with a model that constrained parameter estimates to be identical for boys and girls. Using the chi-square difference test, we found that the gender-specific model was not significantly different, χ2(225, N = 222) = 252.42, p = .10, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .03, compared with the gender-constrained model, χ2(243, N = 222) = 270,48, p = .11, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .03; Satorra-Bentler Adjusted Δχ2(18, N = 222) = 16.37, p = .57, suggesting that we should not test further for path moderation by gender.

Race

To hold constant the geographical context, our tests of moderation by race were conducted with a selected subsample of the youth. Specifically, we only included African American and Caucasian youth from our two racially diverse urban sites (i.e., Nashville, Tennessee, and Seattle, Washington).4 We began our tests of moderation of race by using t tests to compare mean differences between these urban African American and urban Caucasian youth on each of the observed variables. Differences emerged on two of the observed variables. First, we found that mothers of African American youth in urban areas reported significantly more depressive symptoms (M = 14.48, SD = 9.50) than did mothers of Caucasian youth in urban areas (M = 8.98, SD = 6.62) at the Grade 3 assessment, t(73) = 3.29, p = .002. Mothers of African American youth in urban areas also reported less family support (M = 1.80, SD = 0.72) than did mothers of Caucasian youth in urban areas (M = 2.11, SD = 0.66), t(102) = −2.32, p = .02.

Next we ran separate models to compare the subset of urban Caucasian youth with urban African Americans to test for the moderation of race on the overall model and specific paths. The comparison of models generated for these two groups did not demonstrate a significant difference between the race-constrained model, χ2(243, N = 217) = 310.18, p = .002, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .05, in comparison with the race-specific model, χ2(225, N = 217) = 282.72, p = .005, CFI = .92, RMSEA = .05; Satorra-Bentler adjusted Δχ2(18, N = 217) = 25.06, p = .12, suggesting that the relations among the variables were similar for the two racial groups of youth.

Discussion

The findings of this study showed that elevated maternal depressive symptoms were associated with later difficulties in the family environment. Consistent with the growing literature on the parenting deficits of depressed mothers (Burbach & Borduin, 1986; Gelfand & Teti, 1990), mothers with more depressive symptoms had poorer communication and worse relationships with their children 3 years following their most recent measure of depressive symptomatology. As expected, more symptomatic mothers also reported less satisfaction with their social support and the occurrence of more stressful life events in their families.

In terms of mediators of outcome, children with worse relationships with their mothers had more disruptive behavior disorders measured 1 year later, even controlling for early externalizing problems, supporting the notion that the quality of the mother–child relationship is an important psychosocial factor related to children’s disruptive behavior. In other words, maternal depressive symptoms were associated with more contentious mother–child relationships, which predicted more disruptive behavior disorders for children. This finding further reinforces the role of the family as a vital social context for youth, even in early adolescence, as Baumrind (1991) has previously argued. Moreover, the results are consistent with Patterson’s (1982) coercion theory, which posits that children exposed to negative interactions with parents are at elevated risk for externalizing behavior themselves because irritable or problematic exchanges with family are thought to generalize to other settings.

Mothers who reported less satisfaction with their social support network had children with more internalizing disorders 1 year later. These mothers may be modeling dissatisfaction and isolating behavior, or they may be more aversive with their children, as Wahler’s (1990) research has suggested. We speculate that children of mothers with more interpersonal difficulties have more interpersonal difficulties themselves as a result of learning similar habits and patterns of interaction (Harnmen & Brennan, 2001). Alternatively, the presence of maternal depressive symptoms combined with lowered social support may induce in the children excessive or inappropriate caregiving; these children may be left to support or comfort their mothers in a way that is beyond their resources or ability (Cummings & Davies, 1999), leaving them at higher risk for internalizing disorders. Moreover, children of mothers without a support network may have fewer adults who are available for support and involvement in their lives. To increase competency and resiliency among families in which maternal depressive symptoms pose a risk to youth development, a logical intervention would include increasing support within and beyond the family system.

These results are consistent with the emotional security hypothesis laid out by Cummings and Davies (1999), which postulates that negative family influences increase children’s risk for psychopathology by threatening their emotional security. Although this study was not set up as a direct test of their theory, the theory’s supposition that parental support is one aspect of the family process that can impinge on children’s felt security and create vulnerability for psychopathology would fit with the current data.

No differences emerged in the mediators associated with the prediction of internalizing or disruptive behavior disorders for girls and boys. It may be the case that the mediators tested in this study were too general to detect more subtle aspects of stress and support that may pose differential risk to girls and boys, such as the possibility that boys and girls have differential vulnerabilities to different kinds of stress (e.g., extrafamilial versus interfamilial, specific life events versus chronic stressors). It is also possible that gender differences in predictors of risk do not emerge until youth are slightly older, corresponding to the time when gender differences in youth depression emerge (e.g., girls with depressed mothers report the highest level of depressive symptoms after age 13; Hops, 1996), Thus, the development of psychopathology in later adolescence may follow a different course, may show gender-specific risks, or may be influenced by different mediators or risk factors than those outlined here (e.g., see Wierson & Forehand, 1992).

Although no differences were found when the hypothesized model was examined with respect to race, these findings require further replication, given that the race-specific models had relatively small sample sizes and only reached marginal levels of fit. In contrast to Harnish et al. (1995), no differences emerged between mothers of Caucasian and African American youth in the relationship between maternal depressive symptoms and the quality of the mother–child relationship. This difference may be due in part to differences in methodology between the two studies, such as (a) their use of concurrent measurement of the mother–child relationship and child symptomatology versus our longitudinal approach and (b) their measurement of maternal depression at a single time point versus our assessment across 3 years.

The set of mediators in the overall model accounted for additional variance in disruptive behavior and internalizing diagnoses in children, over and above the direct effects of maternal depressive symptoms and early child psychopathology. The moderate relationships we found between maternal depressive symptoms and later parenting variables are particularly interesting in light of the fact that our study did not focus on clinically diagnosed maternal depression but rather used symptoms of depression as measured by a checklist It is likely that effects obtained in this study may be even more pronounced in those with higher levels of depressive symptoms (Gotlib, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1995), although there may also be effects found in clinical populations that did not emerge in this sample. It should be emphasized that our findings may be specific to the particular developmental time frame assessed; We examined maternal depression in early childhood and evaluated child psychopathology as outcomes during the transition from 5th to 6th grade (i.e., in early adolescence).

Several limitations of the research design and methods are acknowledged. Because a large proportion of our sample (40%) consisted of single-parent families, this study did not examine the effects of marital discord, which is another important variable that may also mediate the effects of maternal depression on children and adolescents (Cummings & Davies, 1999; Davies et al., 1999). However, two of the changes that qualified as stressful life events on the life changes measure (parental divorce and stress or conflict in the extended family) are likely related to marital discord. Also, it may be that the presence of a father figure or another involved supportive person—factors not tested in the current model—are also important predictors or moderators of outcome.

It is also important to note that the relationships found in the current study were focused on mothers with depressive symptoms, not mothers who had clinically diagnosed depression. The relationship between maternal depression, the mediators, and the outcomes may be different depending on whether mothers’ symptoms are episodic or chronic in nature. Although the present study did not include further assessment of symptom duration, it is an important issue to pursue. Finally, the study was based on measures that were derived from maternal, child, and interview reports but did not include data from other important sources, including observational methods and teacher reports.

Implications for Application and Public Policy

The identification of parents who have elevated levels of depressive symptoms is a crucial aspect to evaluating children’s risk for psychopathology, including both internalizing and externalizing problems. Because treatments for depression in adults are generally quite effective, increasing referrals and access to treatment for parents should be beneficial in ameliorating their children’s risk. Additionally, treatment providers who work with depressed adults who are also parents should consider conducting an evaluation of the family system and incorporating the children’s mental health needs into their assessments and possibly their intervention approaches. Treatments that address both parent and child vulnerabilities are particularly suited to this task. For example, Sanders and McFarland (2000) reported that a cognitive–behavioral intervention that integrated the treatment of parental depression with teaching parenting skills was helpful in reducing both maternal depression and child disruptive behavior. This twofold approach addressing both parental psychopathology and the parent–child subsystem may hold promise for short-circuiting the development or exacerbation of children’s problems while at the same time improving parental functioning.

This study supports the important role that aspects of parenting and parent–child processes play in the intergenerational transmission of psychopathology. During the preadolescent years, it appears important from a prevention and intervention standpoint to pay close attention to parent–child rifts, attending to the contributing roles of both the child and the parent. In addition, intervention efforts aimed at increasing social support and effective coping should be targeted both to the youth and to the parental system.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grants R18 MH48043, R18 MH50951, R18 MH50952, and R18 MH50953. The Center for Substance Abuse Prevention and the National Institute on Drug Abuse also have provided support for Fast Track through a memorandum of agreement with the NIMH. This work was also supported in part by U.S. Department of Education Grant S184U30002 and NIMH Grants K05MH00797 and K05MH01027.

We are grateful for the close collaboration of the Durham Public Schools, the Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools, the Bellefonte Area Schools, the Tyrone Area Schools, the Mifflin County Schools, the Highline Public Schools, and the Seattle Public Schools. We greatly appreciate the hard work and dedication of the many staff members who implemented the project, collected the evaluation data, and assisted with data management and analyses. We also wish to thank Liliana Lengua and Elizabeth McCauley for their input on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Portions of this article have been presented at the 109th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, San Francisco, August 2001.

Although there is some research examining the children of depressed fathers (or depressed parents), (the vast majority of studies of effects of parental depression on children have focused on the influence of maternal depression. It has been suggested that mothers are more involved than fathers in the intergenerational transmission of depression (Hops, 1996). Also, throughout the article the term depressed is used to refer to parents with clinical depression (major depressive disorder or dysthymic disorder), whereas parents with depressive symptoms is used in reference to parents with elevated levels of self-reported symptoms who do not necessarily meet diagnostic criteria for depression.

The term externalizing problems throughout this article refers to conduct problems such as aggression and delinquency, as measured by the Child Behavior Checklist, and does not include symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity. The corresponding construct drawn from categorical classifications of psychopathology is disruptive behavior disorders, which includes oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder.

A confirmatory factor analysis with a combined communication/relationship construct was also tested but yielded a poorer fit with the data (CFI = 0.89, RMSEA = .08, p < .001).

The models testing for moderation by race were also analyzed with participants from the three urban sites (Durham, North Carolina; Nashville, Tennessee; and Seattle, Washington), and similar results were found.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist 14–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Adrian C, Hammen C. Stress exposure and stress generation in children of depressed mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:354–359. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albright MB, Tamis-LeMonda CS. Maternal depressive symptoms in relation to dimensions of parenting in low-income mothers. Applied Developmental Science. 2002;6:24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, Hammen CL. Psychosocial outcomes of children of unipolar depressed, bipolar, medically ill, and normal women: A longitudinal study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:448–454. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Armistead L, Forehand R, Brody G, Maguen S. Parenting and child psychosocial adjustment in single-parent African American families: Is community context important? Behavior Therapy. 2002;33:361–375. doi: 10.1177/0145445502026004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition. In: Cowan PA, Hetherington M, editors. Family transitions. Hillsdale, NJ: Eribaum; 1991. pp. 111–163. [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Keller MB, Lavori PW, Klerman GK, Dorer DJ, Samuelson H. Psychiatric disorder in adolescent offspring of parents with an affective disorder in a nonreferred sample. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1988;15:313–322. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Podorefsky D. Resilient adolescents whose parents have serious affective and other psychiatric disorders: Importance of self-understanding and relationships. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;145:63–69. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Gladstone TRG. Children of affectively ill parents: A review of the past ten years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:1134–1141. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benazon NR, Coyne JC. Living with a depressed spouse. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:70–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieling PJ, Alden LE. Sociotropy, autonomy, and the interpersonal model of depression: An integration. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:167–384. [Google Scholar]

- Billings AG, Moos R. Comparison of children of depressed and nondepressed parents: A social environmental perspective. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1983;11:483–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00917076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudek R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Burbach DJ, Borduin CM. Parent–child relations and the etiology of depression: A review of the methods and findings. Clinical Psychology Review. 1986;6:133–153. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL, Lynch M. Bowlby’s dream comes full circle: The application of attachment theory to risk and psychopathology. In: Ollendick T, Prinz R, editors. Advances in clinical child psychology. Vol. 17. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. A developmental and clinical model for the prevention of conduct disorders: The FAST Track Program. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:509–527. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Merging universal and indicated prevention programs: The Fast Track model. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:913–927. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00120-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook E, Greenberg M, Kusche C. People in My Life: Attachment relationships in middle childhood; Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Indianapolis, IN. 1995. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Greenberg MT. Minor parenting stresses with young children. Child Development. 1990;61:1628–1637. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Maternal depression and child development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35:73–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Depressed parents and family functioning: Interpersonal effects and children’s functioning and development. In: Joiner T, Coyne JC, editors. The interactional nature of depression. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 299–327. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Dumenci L, Windle M. The interplay between maternal depressive symptoms and marital distress in the prediction of adolescent adjustment. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:238–254. [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:50–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin BA, Newman E, McMackin RA, Morrissey C, Kaloupek DG. PTSD, malevolent environment, and criminality among criminally involved male adolescents. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2000;27:196–215. [Google Scholar]

- Fendrich M, Warner V, Weissman MM. Family risk factors, parental depression, and psychopathology in offspring. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Brody G, Armistead L, Dorsey S, Morse E, Morse PS, Stock M. The role of community risks and resources in the psychosocial adjustment of at-risk children: An examination across two community contexts and two informants. Behavior Therapy. 2000;31:395–414. [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, McCombs A, Brody G. The relationship between parental depressive mood states and child functioning. Advances in Behaviour Therapy and Research. 1987;9:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Neighbors B, Wierson M. The transition to adolescence: The role of gender and stress in problem behavior and competence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1991;32:929–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb01920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Little S. Predictors of competence among offspring of depressed mothers. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1999;14:44–71. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand DM, Teti DM. The effects of maternal depression on children. Clinical Psychology Review. 1990;10:329–353. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Adamson LB, Riniti J, Cole S. Mothers’ expressed attitudes: Associations with maternal depression and children’s self-esteem and psychopathology. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33:1265–1274. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199411000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Brogan D, Lynch ME, Fielding B. Social and emotional competence in children of depressed mothers. Child Development. 1993;64:516–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of risk. Psychological Review. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyer IM, Wright C, Altham PME. Maternal adversity and recent stressful life events in anxious and depressed children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1988;29:651–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1988.tb01886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D, Surge D, Hammen C, Adrian C, Jaenicke C, Hiroto D. Observations of interactions of depressed women with their children. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;146:50–55. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Symptoms versus a diagnosis of depression: Differences in psychosocial functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:90–100. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Depression runs in families: The social context of risk and resilience in children of depressed mothers. New York: Plenum Press; 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991b;100:555–561. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Brennan PA. Depressed adolescents of depressed and nondepressed mothers: Tests of an interpersonal impairment hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:284–294. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harnish JD, Dodge KA, Valente E Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Mother–child interaction quality as a partial mediator of the roles of maternal depressive symptomatology and socioeconornic status in the development of child behavior problems. Child Development. 1995;66:739–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings TL, Anderson SJ, Kelley ML. Gender differences in coping and daily stress in conduct-disorder and non-conduct-disordered adolescents. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1996;18:213–226. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AA. Four-factor index of social status. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1979. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Hooven C, Gottman JM, Katz LF. Parental meta-emotion structure predicts family and child outcomes. Cognition and Emotion. 1995;9:229–264. [Google Scholar]

- Hops H. Intergenerational transmission of depressive symptoms: Gender and developmental considerations. In: Mundt C, Goldstein MJ, Hahlweg K, Fiedler P, editors. Interpersonal factors in the origin and course of affective disorders. London, England: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 1996. pp. 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hops H, Biglan A, Sherman L, Arthur J, Friedman L, Osteen V. Home observations of family interactions of depressed women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:341–346. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structural analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM, Kano Y. Can test statistics in covariance structure analysis be trusted? Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:351–362. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Johnson SL. Parent–child interaction among depressed fathers and mothers: Impact on child functioning. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:391–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Johnson SL. Sequential interactions in the parent–child communications of depressed fathers and depressed mothers. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:38–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan B, Beardslee W, Keller M. Intellectual competence in children of depressed parents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1987;16:158–163. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Magee WJ. Childhood adversities and adult depression: Basic patterns of association in a U.S. national survey. Psychological Medicine. 1993;23:679–690. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700025460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Gottlib IH. Maternal depression and child adjustment: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1989;98:78–85. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.98.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeloew M. Parent–child interaction and adult depression: A prospective study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1999;100:270–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen WB. Antisocial behavior and mental health problems: Explanatory factors in childhood and adolescence. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Loss N, Beck SJ, Wallace A. Distressed and nondistressed third- and sixth-grade children’s self-reports of life events and impact and concordance with mothers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1995;23:397–409. doi: 10.1007/BF01447564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montemayor R. Family variation in parent–adolescent storm and stress. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1986;1:15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. MPlus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Early Child Care Research Network. Chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms, maternal sensitivity, and child functioning at 36 months. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1297–1310. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor MJ, Kasari C. Prenatal alcohol exposure and depressive features in children. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:1084–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, MacDonald KB, Beitel A, Bhavnagri N. The role of the family in the development of peer relationships. In: Peters RDeV, McMahon RJ., editors. Social learning and systems approaches to marriage and the family. New York: Brunner-Mazel; 1988. pp. 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson G. Family coercive process. Eugene, OR: Castalia Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Hamburg BA. Adolescence: A developmental approach to problems and psychopathology. Behavior Therapy. 1986;17:480–499. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Sarigiani PA, Kennedy RE. Adolescent depression: Why more girls? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20:247–271. doi: 10.1007/BF01537611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini JC, Cohen P, Cohen J. Combining discrepant diagnostic information from multiple sources: Are complex algorithms better than simple ones? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1992;20:51–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00927116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, Pakiz B, Silverman AB, Frost AK, Lefkowitz ES. Psychosocial risks for major depression in late adolescence: A longitudinal community study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:1155–1163. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199311000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Commentary: Some focus and process considerations regarding the effects of parental depression on children. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MR, McFarland M. Treatment of depressed mothers with disruptive children: A controlled evaluation of cognitive behavioral family intervention. Behavior Therapy. 2000;31:89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A. Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. In: Heijmans RDH, Pollock DSG, Satorra A, editors. Innovations in multivariate statistical analysis. London, England: Kluwer Academic; 2000. pp. 233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier LM, Botvin GL, Miller NL. Life events, neighborhood stress, psychosocial functioning, and alcohol use among urban minority youth. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2000;9:19–50. [Google Scholar]

- Segrin C, Abramson LY. Negative reactions to depressive behaviors: A communications theories analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:655–668. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.4.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons RG, Burgeson R, Carlton-Ford S, Blyth DA. The impact of cumulative change in early adolescence. Child Development. 1987;58:1220–1234. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slesnick N, Waldron HB. Interpersonal problem-solving interactions of depressed adolescents and their parents. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:234–245. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Barrera M, Chassin L. Relation of parental support and control to adolescents’ externalizing symptomatology and substance use: A longitudinal examination of curvilinear effects. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:609–629. doi: 10.1007/BF00916446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack S, Coyne JC. Social confirmation of dysphoria: Shared and private reactions to depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;44:798–806. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.44.4.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti DM, Gelfand DM. Maternal cognitions as mediators of child outcomes in the context of postpartum depression. In: Murray L, Cooper P, editors. Postpartum depression and child development. New York: Guilford Press; 1997. pp. 136–164. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry T, Huizinga D, Loeber R. The prevention of serious delinquency and violence: Implications from the Program of Research on the Causes and Correlates of Delinquency. In: Howell J, Krisberg B, Hawkins D, Wilson JD, editors. Sourcebook on serious, violent, and chronic juvenile offenders. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. pp. 213–327. [Google Scholar]

- Tisher M, Tonge BJ, Horne DJ. Childhood depression, stressors, and parental depression. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;28:635–641. doi: 10.1080/00048679409080787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahler RG. Some perceptual functions of social networks in coercive mother–child interactions. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990;9:43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Hammond M. Maternal depression and its relationship to life stress, perceptions of child behavior problems, parenting behaviors, and child conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1988;16:299–315. doi: 10.1007/BF00913802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Gammon GD, John K, Merikangas KR, Warner V, Prusoff BA, Sholomskas D. Children of depressed parents: Increased psychopathology and early onset of major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:847–853. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800220009002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werthamer-Larsson L, Kellam SG, Wheeler L. Effect of first-grade classroom environment on shy behavior, aggressive behavior, and concentration problems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1991;19:585–602. doi: 10.1007/BF00937993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierson M, Forehand R. Family stressors and adolescent functioning: A consideration of models for early and middle adolescents. Behavior Therapy. 1992;23:671–688. [Google Scholar]