Abstract

The relation between social rejection and growth in antisocial behavior was investigated. In Study 1, 259 boys and girls (34% African American) were followed from Grades 1 to 3 (ages 6–8 years) to Grades 5 to 7 (ages 10–12 years). Early peer rejection predicted growth in aggression. In Study 2, 585 boys and girls (16% African American) were followed from kindergarten to Grade 3 (ages 5–8 years), and findings were replicated. Furthermore, early aggression moderated the effect of rejection, such that rejection exacerbated antisocial development only among children initially disposed toward aggression. In Study 3, social information-processing patterns measured in Study 1 were found to mediate partially the effect of early rejection on later aggression. In Study 4, processing patterns measured in Study 2 replicated the mediation effect. Findings are integrated into a recursive model of antisocial development.

Ever since longitudinal studies established that childhood peer sociometric status is a marker of later antisocial outcomes (e.g., Cowen, Pederson, Babigian, Izzo, & Trost, 1973; Roff, Sells, & Golden, 1972; see review by Coie, in press), peer rejection has been given extraordinary status in social development research, perhaps standing next to the parent–child-based attachment theory as a major paradigm for inquiry. Whereas some studies have examined behavioral, social-cognitive, and family background antecedents of rejected status, others have attempted to alter children’s status through intervention (see Asher & Coie, 1990; Kupersmidt & Dodge, in press). This work is predicated on the assumption that peer status plays a causal role in the exacerbation of antisocial development. However, few studies have tested this assumption, and virtually no study has examined the processes through which this development might occur. The goals of the current article are to: (a) examine the role of social rejection in exacerbating antisocial development, (b) test the hypothesis that temperament moderates this effect, (c) examine whether these effects hold equally well for girls and boys, and (d) test the hypothesis that this effect is mediated by acquired patterns of processing social information.

At one extreme, researchers have characterized peer rejection as a personality trait, referring to “rejected children” as a type of child, just as we refer to introverted children and children with mental retardation as types of children. Even researchers who recognize the heterogeneity of this phenomenon have spoken of subtypes of rejected children, as in “rejected-aggressive” and “rejected-withdrawn” children (Bierman, Smoot, & Aumiller, 1993), as if these groups were personality types. At the opposite end of the theoretical spectrum has stood Olweus (1989), who called for an end to all research on peer rejection because it is not a trait of the child but rather a characteristic of the peer group. He concluded that rejection by peers is epiphenomenal to the personality characteristics that lead a child to be rejected.

The perspective adopted in the current context is that peer rejection is a life event and an interpersonal stressor that might exert an enduring impact on a child’s development. Peer rejection describes the relationship between the child and the peer group. Because relationships form the context for social learning, problematic relationships might prevent a child from learning social skills and instead lead a child to develop negative expectations about future relationships. As such, rejection might have a long-term adverse impact. In this context, social rejection merits study as a chronically stressful experience, in the same way that physical abuse, rape, early loss of a parent, and the experience of victimization by bullying peers merit empirical inquiry.

The first question guiding this work can be framed empirically in terms of the increment in prediction of later aggressive behavior that is afforded by early knowledge that a child has been rejected by his or her peer group. Rejection might be a marker of developmental processes without playing any causal role. That is, it might be that peers can detect emerging psychopathology before the mental health system does or that the factors that lead to peer rejection are the same factors that are responsible for later detected antisocial behavior. Alternately, rejection might play a direct and causal, or at least empirically incremental, role in antisocial development, beyond any of the factors contributing to a child’s rejection. It is hypothesized that, as a provocation stimulus, peer social rejection will lead children to respond with increased reactive and proactive aggressive behavior (Dodge & Coie, 1987). This effect has been assumed by interventionists seeking to prevent or alter rejection, but it has been studied seldom. Reviewers (Kupersmidt, Coie, & Dodge, 1990; Parker & Asher, 1987) discuss this causal question but offer no empirical study or analysis.

Even if social rejection is found to predict aggressive behavior, it might be accounted for by third variables or opposite causation. Therefore, three alternate interpretations are tested. The first possibility is that early antisocial behavior could lead both to social rejection and to later antisocial behavior. A large body of literature supports the conclusion that antisocial behavior precedes peer rejection and is a primary reason that peers cite for their rejection of a child (Coie, in press). The question being tested, then, is whether social rejection predicts change and growth in antisocial behavior, controlling for antisocial behavior that might antecede peer social rejection. The second alternate interpretation is that other behaviors (e.g., social incompetence) might lead both to social rejection and to growth in antisocial behavior. Because both peer rejection and antisocial behavior are known to correlate with competent behavior in specific social situations (e.g., peer group entry skills, Putallaz & Wasserman, 1990; compliance with the teacher, Bierman et al., 1993; and awareness of social norms, Dodge, McClaskey, & Feldman, 1985), social competence was controlled in the first study. In the second study, both school performance and internalizing behavior problems (also known correlates of both social preference and antisocial behavior; Kupersmidt & Dodge, in press) were included as control variables. The third alternate interpretation is that perhaps it is not peers’ rejection of a child that provides prediction but rather peers as a rater of a child’s problems. Perhaps the peer group can identify subtle characteristics in a child that indicate signs of growing antisocial behavior even when teachers are not able to detect these signs. If so, peer social rejection might be an important predictor not because of social status but because it is the peer group that is identifying the problem child. To test this possibility, peer nominations for aggressive behavior were included as a control variable to test the increment in growth in antisocial behavior from early peer rejection controlling for peer nominations for aggressive behavior.

Kupersmidt and Coie (1990) and Coie, Lochman, Terry, and Hyman (1992) showed that in their third-grade samples both early rejection and early aggressive behavior had independent additive effects on later antisocial outcomes, although the Kupersmidt and Coie finding for rejection was only marginally significant. By beginning their inquiry as late as third grade, the recursive relation between aggression and rejection may render separate tests difficult. The 19 rejected children in that sample also may have been too small a group to test the possible moderating, or interaction, effect of rejection in combination with early aggression. Two more recent longitudinal studies suggest that early social rejection might provide a unique increment in predicting later antisocial outcomes. Miller-Johnson, Coie, Maumary-Gremaud, Lochman, and Terry (1999) found that social rejection in third-grade boys incremented the prediction of early adulthood crime beyond the prediction afforded by early aggressive behavior. Bierman and Wargo (1995) found that antisocial outcomes were more severe for children who were both socially rejected and aggressive than for children who were only aggressive.

The second question guiding this study concerned the moderating role that rejection might play in exacerbating problems that are already present or in allowing problematic outcomes to develop. The theoretical basis for this question derives from a conceptualization of rejection as a general social stressor. Like stress effects on engineering mechanics and physical health, a general stressor is most likely to have an effect on the most vulnerable aspect of a person’s disposition. It is plausible that social rejection will exacerbate aggressive behavior only in children who are already showing signs of antisocial behavior. Another way of framing this role is in terms of the buffering effect that social acceptance might play. That is, if a child has begun a process of development of conduct disorder, social acceptance among peers might inhibit this trajectory. A child moving down the conduct disorder path may come upon opportunities to disrupt this course, such as a loving parent, or a protective adult mentor, or perhaps a peer group that teaches the child the value of group participation and social exchange. In ANOVA terms, this moderating role is an interaction effect that is exhibited in combination with a pathogenic process. Because of gender differences in the base rates of aggression, the triple interaction involving rejection, aggression, and gender is also tested. It is also possible that peer rejection will exacerbate social withdrawal in children who already show signs of withdrawal. This interaction effect was also tested.

The third question addressed here was whether the effect of social rejection on aggressive behavior varies across boys and girls. Gender differences in the rate of aggressive behavior are well documented (Coie & Dodge, 1998), as are gender differences in peer rejection (Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982). Unanswered, however, is whether peer rejection exacerbates aggressive behavior to an equal degree in boys and girls. This question assumes heightened importance as national arrest records for assault indicate that the gender difference in aggression appears to be diminishing across generations (Kruttschnitt, 1994) and research on aggression in girls has become more prominent (Putallaz & Bierman, in press).

The fourth question guiding this research concerned the mechanisms through which the effect of social rejection on antisocial development occurs. That question was addressed only after the effect itself was understood. Four prospective studies are reported here. The first two studies evaluated the predictability of middle childhood aggressive behavior from peer social preference scores and status as sociometrically rejected in the first years of elementary school. Study 1 reports the initial finding, and Study 2 provides an independent replication with a larger sample. Studies 3 and 4 address causal mechanisms.

Study 1

This study used a longitudinal design with boys and girls during their first school encounters with peers in first grade to examine the marker, direct, and moderator roles of peer rejection in the growth of aggressive behavior problems 4 years later.

Method

Participants

Children were selected to participate in the Social Development Project (Burks, Dodge, Price, & Laird, 1999; Dodge & Price, 1994). This representative sample included 259 boys and girls from 13 classrooms in a Nashville, Tennessee, public school. More than 80% of the children in each class participated. The sample was diverse with respect to gender (52% male) and ethnicity (64% European American, 34% African American, 2% other). These children were enrolled in Grades 1, 2, or 3 (ages 6, 7, or 8) during 1987 to 1988. For the present study, annual assessments were available for 5 years (i.e., until the children were in Grades 5, 6, and 7; ages 10, 11, and 12). In Year 5, 79% of the children continued to participate.

Procedure and measures

In the first 2 years of data collection, sociometric interviews following the protocol described by Coie et al. (1982) were conducted in all classrooms. Interviews were conducted individually and orally. Children were shown a class roster and asked to rate how much they liked each other child on a 5-point scale. Children then named up to three peers they especially liked and up to three peers they especially disliked. A social preference score was created by taking the standardized difference between the standardized like-most nomination score and the standardized dislike-most nomination score. Children were classified as being rejected by peers if their social preference score was less than −1, standardized like-most score was less than 0, and standardized like-least score was greater than 0. Based on these criteria, 40 children (15% of the sample) were classified as being socially rejected in the first year of data collection (i.e., when they were in first, second, or third grade). Children also nominated up to three peers as starting fights, disrupting the group, and getting angry. The nomination scores for each of these three items were standardized and averaged to create a reliable index of peer-nominated aggression (Cronbach’s alpha = .94).

Classroom teachers completed the 110-item Teacher Report Form (TRF) of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1986) for each participating child in Years 3, 4, and 5 of data collection. The raw score from the 25-item aggression subscale was used as a measure of child behavior problems. This scale includes items describing physical aggression, disruption, and oppositional behaviors. For each item, teachers indicated whether the statement describing a particular behavior (e.g., arguing, fighting, threatening) was not true (0), somewhat or sometimes true (1), or very or often true (2) of the child. TRF Aggression in Year 5 was the main outcome measure.

Teachers did not complete the TRF in Years 1 and 2 of data collection, but they did complete the Reactive-Proactive Aggression Scale (Dodge & Coie, 1987) and the Taxonomy of Problematic Situations (Dodge et al., 1985). On the first measure, teachers rated the child’s behavior on 6 items reflecting reactive (i.e., angry) and proactive (i.e., bullying) behavior on a 5-point scale of increasing aggression (Cronbach’s alpha = .91). On the second measure, teachers rated 44 items reflecting situations that are possibly problematic for children, including peer group entry, responding to authority requests, and awareness of social norms. Reliable scores for incompetent behavior in each of these social situations were created (Cronbach’s alphas = .94, .95, and .96, respectively).

Results and Discussion

As many others have found (Kupersmidt, Coie, & Dodge, 1990), we found highly robust negative correlations between social preference scores in Years 1 and 2 and raw teacher-rated Achenbach TRF Aggression scale scores in Year 5, r(183) = −.31 for Year 1 and r(179) = −.36 for Year 2,; both ps<.001. These predictive correlations held among both boys and girls and across ethnic groups.

ANOVA with rejection status in Year 1 (no or yes), gender, and age cohort (Grade 1, 2, or 3) as factors revealed that children who were socially rejected in Year 1 had levels of teacher-rated aggression in Year 5 that were almost twice as high as those of children who had not been rejected in Year 1, F(1, 181) = 4.37, p<.05 (M = 11.33 vs. 6.60). A similar analysis with Year 2 rejection status as a factor revealed that children who were rejected in Year 2 had levels of teacher-rated aggression in Year 5 that were almost 3 times as high as those of children who had not been rejected in Year 2, F(1, 182) = 23.64, p<.001 (M = 17.53 vs. 6.05). These findings support, at minimum, the marker role of early rejection in predicting later TRF-based aggression problems.

We also found evidence to support the direct role of early social preference in this relation after controlling for confounding factors. First, we computed partial correlations, in which Year 5 TRF Aggression scores were predicted from earlier social preference scores after partialling out the effects of all previous teacher-rated aggression scores. These partial correlations were modest but significant, r(170) = −.17, p<.05, and r(170) = − .21, r<.01, for social preference scores in Years 1 and 2, respectively. Next, we partialled out other behavior scores collected from teachers in Year 1 and still found a direct effect of Year 1 social preference on Year 5 TRF Aggression, rs(179) = −.22, −.15, and −.21, controlling for problems with peer group entry, responding to the teacher, and awareness of social norms, respectively, ps<.05 or better.

The effect could be due to the unique perspective of peers as raters rather than rejection per se; therefore, we next partialled out aggressive behavior nomination scores collected from peers in Year 1. For this analysis, peers were raters for both aggression and social preference. We could not statistically explain away the incremental effect of Year 1 social preference beyond early aggression in predicting Year 5 TRF Aggression, r(180) = −.16, p<.05.

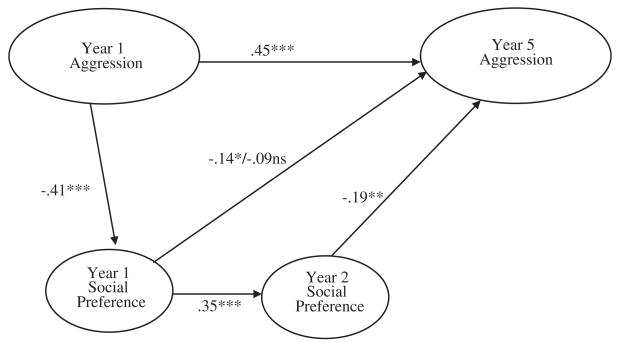

Next, we used path analyses to evaluate the incremental role of social preference scores at each year in this prediction (see Figure 1). Of the variance in Year 5 aggression, 34% was accounted for by Year 1 aggression and the child’s social preference history, with the latter making significant contributions to this prediction. Social preference scores in Years 1 and 2 each made significant incremental contributions in predicting later TRF Aggression beyond the prediction afforded by knowledge of early aggression. As expected, Year 1 aggression scores also predicted Year 1 social preference, and Year 1 preference predicted Year 2 preference. Even after these effects were considered, social preference scores in each year provided unique increments in the prediction of aggression in Year 5. These findings mean that Year 1 social preference has an effect on later aggressive behavior even if the child is not rejected again in the following year. Early social preference contributes uniquely to later aggressive behavior by a child. These findings also mean that the effects of social preference cumulate over time, because information about social preference in Year 2 provides a significant increment in the prediction beyond Year 1 information.

Figure 1.

Social Development Project prediction of Year 5 TRF Aggression from Year 1 Aggression and previous social preference scores. First numbers shown are standardized path coefficients controlling for all earlier factors. Numbers after the slash control for both earlier and later factors. Full model R2 = .34; F(3, 175) = 29.58. *p<.05. **p<.01. ***p<.001.

Next, children were classified into one of three groups based on the number of years they experienced rejection by peers (0, 1, or 2). ANOVA with years of rejection, gender, and age cohort as independent variables and Year 5 TRF Aggression score as the dependent variable revealed a significant main effect of years experiencing rejection, F(2, 166) = 8.31, p<.001. Mean Year 5 TRF Aggression scores for groups of children who met criteria for rejection in 0, 1, or 2 of the first 2 years of the study were 5.89, 11.21, and 22.20, respectively, with each pair of groups significantly differing at p<.05. A significant main effect of gender indicated that boys were more aggressive than girls, but gender did not interact significantly with years of rejection. This finding highlights the cumulative effects of social rejection. Children who had been rejected in both years received aggression scores that were almost 4 times greater than those of children who had never been rejected.

Although it is tempting to start using terms such as cause and effect in describing the role of social rejection, we must stop short of this conclusion because there still might exist other variables that could account for both early rejection and later aggression. This possibility will always hold true for descriptive longitudinal research in which variables are observed and not experimentally manipulated. Still, it seems that the experience of rejection by peers, especially chronic rejection lasting 2 years, plays a contributing role beyond that of a mere marker variable.

Study 2

We sought to replicate and extend these findings in a second longitudinal study. Furthermore, a larger sample was sought to examine possible moderators of this effect of early social rejection that could not be adequately tested with the small sample size of the first study. Conceptualizing peer social rejection as a general stressful life experience suggests that the impact of this stressor could depend on the child’s predispositional tendency to respond to stressors with externalizing versus internalizing behaviors (Bates, Freeland, & Lounsbury, 1979; Rubin, Hymel, Mills, & Rose-Krasnor, 1991). We hypothesized that peer rejection will lead to growth in aggressive behavior only among the subgroup of children that has a difficult temperament or is predisposed to aggressive reactions. Among the subgroup of children not so predisposed, peer rejection will not lead to growth in aggressive behavior, although nonaggressive maladjustment outcomes might still occur.

Method

Participants

A representative sample of 585 kindergarten boys and girls (age 5) participated in the ongoing Child Development Project (Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1990; Pettit, Bates, & Dodge, 1997). The sample includes ethnically diverse (82% European American, 16% African American, 2% from other ethnic backgrounds) children who matriculated in 15 public schools in 1987 and 1988 in three geographic sites at Nashville and Knoxville, Tennessee, and Bloomington, Indiana. Parents were approached at random during kindergarten preregistration and asked if they would participate in a longitudinal study of child development. About 15% of all children at the targeted schools did not preregister; therefore, this proportion of participants was recruited on the first day of school by letter or telephone. Of those asked, approximately 75% agreed to participate. Girls composed 48% of the sample.

Children and their parents participated in an initial assessment during the summer before children started kindergarten and during follow-up assessments annually. The present study included data from kindergarten (age 5) through third grade (age 8). In third grade, 85% of the children continued to participate in the study. These children did not differ from attrited children on child or family variables from the initial assessment.

Procedure and measures

Social preference scores and sociometric status were assessed as in the previously described Social Development Project following the protocol described by Coie et al. (1982). During the winter of each school year, sociometric interviews were conducted in all classrooms in which at least 70% of children’s parents gave consent. Based on the criteria described previously, 66 children (11% of the sample) were classified as being rejected in kindergarten.

Approximately 6 months after children’s initial entry into the study and annually thereafter, their classroom teachers completed the TRF of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1986). As in the Social Development Project, the raw score from the 25-item aggression subscale was used as a measure of child behavior problems. Teachers also rated children’s behavior on the Reactive–Proactive Aggression Scale (Dodge & Coie, 1987), with three items assessing reactive aggression (Cronbach’s α = .90 to .93) and three items assessing proactive aggression (Cronbach’s α = .86 to .91). Teachers were compensated $5 for each child they rated.

Results and Discussion

Our goals were to replicate the findings from the Social Development Project regarding the direct role of early social rejection in relation to later aggression and to extend these findings by examining sex differences, differences between reactive and proactive aggression, and the possible moderator roles of early social rejection in later behavior problems. The results that follow report Grade 3 TRF Aggression outcomes. Analyses using Grade 3 reactive aggression and proactive aggression scores as separate outcomes were highly consistent with analyses for TRF Aggression. The few exceptions are integrated when the corresponding results for TRF Aggression are described.

First, we found robust negative correlations between social preference scores in kindergarten (age 5) and in Grades 1, 2, and 3 (ages 6, 7, and 8) and TRF Aggression scale scores in Grade 3 (age 8), r(484) = −.36, r(430) = −.39, r(450) = −.33, and r(430) = −.42 for kindergarten, first, second, and third grades (ages 5, 6, 7, and 8), respectively, all ps<.001. These correlations did not vary significantly across sites, cohorts, sexes, and racial groups.

ANOVA with rejection status (no or yes), gender, site, and cohort as factors revealed that children who were socially rejected in kindergarten (age 5) had mean TRF Aggression scores in Grade 3 (age 8) that were 2.8 times higher than those of the nonrejected group, F(1,482) = 53.24, p<.001. Nearly identical findings held for rejected groups identified in first grade (age 6), F(1, 437) = 50.69; second grade (age 7), F(1, 469) = 30.89; and third grade (age 8), F(1, 437) = 94.94, all ps<.001. A significant main effect of gender on TRF Aggression revealed that teachers reported higher levels of aggression for boys than for girls, but gender did not interact significantly with social rejection in the prediction of aggression.

Next, we computed partial correlations, in which third grade (age 8) TRF Aggression scores were predicted from earlier social preference scores after partialling out the effects of all previous TRF Aggression scores. These partial correlations were robust, r(477) = −.21, r(403) = − .17, and r(420) = − .15 for kindergarten, first, and second grades (ages 5, 6, and 7) social preference scores, respectively, all ps<.01. The same findings held when we used ANCOVA with the rejected and nonrejected groups, controlling for prior aggression scores, at kindergarten (age 5), F(1, 477) = 13.01; at first grade (age 6), F(1, 431) = 20.81; and at second grade (age 7), F(1, 439) = 7.38, all ps<.01 or better. Again, no significant interactions between gender and rejection were found. The evidence to this point replicates our previous findings supporting the direct role of social rejection in later TRF Aggression.

When we partialled out TRF school performance, r(460) = − .33, p<.001, and TRF internalizing, r(477) = − .36, p<.001, scores collected from kindergarten teachers, we still found a direct effect of early rejection on Grade 3 (age 8) TRF Aggression. The effect also held when we partialled out aggressive behavior nomination scores collected from kindergarten (age 5) peers, r(481) = − .14, p<.01. When reactive and proactive aggression were examined separately, however, after partialling out aggressive behavior nominations provided by kindergarten peers, the correlation between kindergarten (age 5) rejection and Grade 3 (age 8) proactive aggression was no longer significant, r(483) = − .06, although the correlation between kindergarten (age 5) rejection and Grade 3 (age 8) reactive aggression remained significant, r(483) = − .16, p<.001. Thus, early peer rejection appears to exacerbate growth in reactive rather than proactive aggressive behavior. Furthermore, we could not statistically explain away the incremental effect of kindergarten (age 5) social rejection beyond other early factors in predicting Grade 3 (age 8) aggression, and the findings held for both boys and girls.

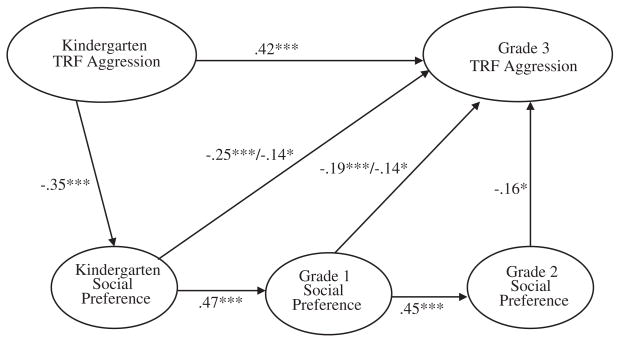

Next, we replicated the path analyses evaluating the incremental role of social preference scores at each grade level in this prediction (see Figure 2), including Gender × Kindergarten Aggression and Gender × Social Preference interactions for each year. Of the variance in Grade 3 (age 8) aggression, 34% was accounted for by kindergarten (age 5) aggression and the child’s social preference history. None of the interactions involving gender was significant. Social preference scores in each successive year made a significant incremental contribution in predicting later TRF Aggression, beyond the prediction afforded by knowledge of early aggression and previous preference scores. When these analyses were conducted using Grade 3 (age 8) reactive and proactive aggression outcomes, the Grade 2 (age 7) social preference score did not significantly increment the prediction of Grade 3 (age 8) proactive aggression after taking into account kindergarten and Grade 1 social preference scores (β = .06, ns); however, Grade 2 (age 7) social preference did significantly increment this prediction for Grade 3 (age 8) reactive aggression (β = −.20, p<.01). In combination with the partial correlation results, these findings suggest that the link between social rejection and growth in aggression is stronger for reactive than for proactive aggression.

Figure 2.

Child Development Project prediction of Grade 3 TRF Aggression from kindergarten aggression and previous social preference scores. First numbers shown are standardized path coefficients controlling for all earlier factors. Numbers after the slash control for both earlier and later factors. Full model R2 = 34; F(8, 381) = 24.44. *p<.05. **p<.01. ***p<.001.

ANOVA was conducted on Grade 3 (age 8) TRF Aggression scores as a function of a grouping variable that classified children according to the number of years they experienced rejection, with gender, race, cohort, and site as other factors. Mean Grade 3 (age 8) TRF Aggression scores for groups of children who met criteria for rejection in 0, 1, 2, or 3 years of elementary school before Grade 3 (age 8) were 4.00, 9.19, 14.66, and 19.43, respectively. These differences were highly significant, F(3, 447) = 26.97, p<.001. Children who had been rejected continuously for 3 years received Grade 3 aggression scores that were 5 times greater than those of children who had never been rejected. Cell contrasts (p<.01) revealed that 1 year of rejection led to worse outcomes than 0 years, and 2 years was worse than 1 year. Two years and 3 years did not differ. In these analyses, neither the main effect of gender nor the interaction between gender and the number of years of rejection was significant in the prediction of Grade 3 (age 8) TRF Aggression.

At this point, the replication supports the hypothesis that the experience of rejection plays a contributing role, beyond that of a mere marker variable, in the development of later behavior problems. We next examined whether this effect is moderated by another factor. If social rejection acts as a general stressor to exacerbate a child’s maladjustment, it is plausible that the effect of rejection on later aggressive behavior would be greatest for children who were initially inclined toward aggression. We asked the question: Is the effect of social rejection equally strong for children initially inclined toward aggression and children initially inclined away from aggression? We used a median split of the sample based on the kindergarten TRF Aggression scores to generate four groups of children: nonrejected-nonaggressive, rejected-nonaggressive, nonrejected-aggressive, and rejected-aggressive. This classification resembles groupings that are increasingly standard in the field (see Bierman et al., 1993; Bierman & Wargo, 1995; Cillessen, Van Ijzendoorn, Van Lieshout, & Hartup, 1992).

We then conducted an ANOVA on Grade 3 (age 8) TRF Aggression scores, with kindergarten (age 5) rejected status and kindergarten aggression status as factors, along with gender, race, cohort, and site. We found three significant and unique effects that held across gender, race, cohort, and site. We found strong main effects of early social rejection, F(1, 473) = 10.52, p<.001, and early aggression status, F(1, 473) = 40.94, p<.001. As hypothesized, there was also a significant interaction of rejection and early aggression, F(1, 473) = 6.03, p<.05. The effect of rejection was much stronger among those children who were initially inclined toward aggressive behavior (i.e., above the kindergarten median for aggression) than among those who were inclined initially away from aggressive behavior.

When Grade 3 (age 8) reactive aggression was analyzed as the outcome, the main effect of kindergarten (age 5) rejected status, F(1, 467) = 19.92, p<.001, and kindergarten (age 5) reactive aggression, F(1, 467) = 14.58, p<.001, was each significant, but the interaction between rejection and kindergarten reactive aggression was not significant, F(1, 467) = .82, ns. With Grade 3 (age 8) proactive aggression as the outcome, the main effect of kindergarten (age 5) rejected status was significant, F(1, 469) = 6.80, p<.01, but the main effect of kindergarten (age 5) proactive aggression was not significant, F(1, 469) = 1.66, ns. The interaction between kindergarten (age 5) rejection and kindergarten (age 5) proactive aggression was significant, F(1, 469) = 4.04, p<.05, indicating that the effect of early peer rejection held for proactively aggressive kindergarteners but not for children who were not disposed toward aggression in kindergarten.

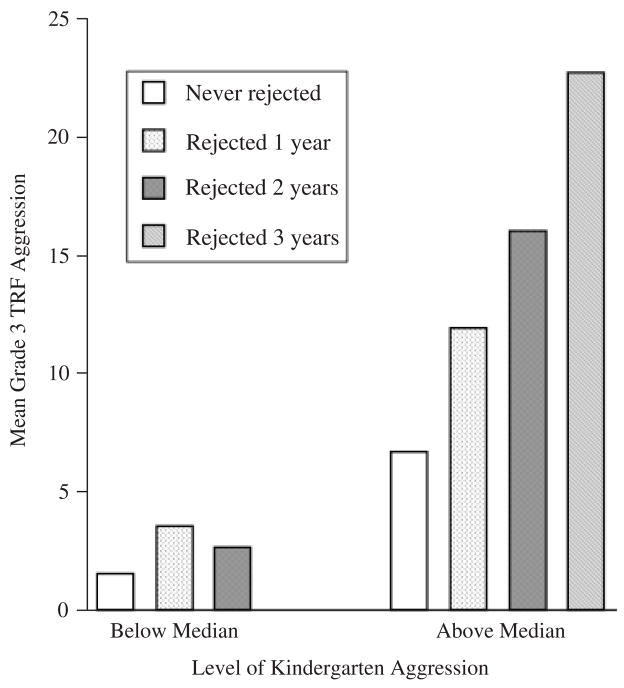

The next analysis examined the cumulative effects of chronic rejection as a function of early aggressive disposition. An ANOVA with Grade 3 (age 8) TRF Aggression as the dependent variable and cumulative rejection (0, 1, 2, or 3 years) and kindergarten (age 5) aggression status (above or below the median) as independent variables (along with site, cohort, gender, and race) revealed a main effect of rejection, F(3, 464) = 7.55, p<.001, a main effect of kindergarten aggression status, F(1, 464) = 27.13, p<.001, a significant Gender × Kindergarten (age 5) aggression interaction effect, F(1, 464) = 7.23, p<.01, and a Rejection × Kindergarten aggression status interaction effect, F(3, 464) = 3.79, p<.01. The Gender × Aggression effect indicated that Grade 3 (age 8) aggression scores differed across high and low kindergarten (age 5) aggression groups to a greater degree for boys than girls.

Figure 3 shows that even cumulative rejection does not increase aggressive behavior in children who were not initially inclined toward aggression. Graphed here are the Grade 3 (age 8) TRF Aggression scores by the number of years of rejection that have been experienced by a child, with separate graphs for children initially below the median in kindergarten (age 5) aggression and for children above the median. As shown, the effects of rejection are dramatic and cumulative for children initially above the median in aggression, but these effects are minimal for children initially below the median in aggression. There were no children who were initially below the median on aggression who were rejected for all 3 years. This figure shows that among children who had been initially inclined toward aggressive behavior, if the peer group is accepting of the child continuously across the early elementary school years, that child’s later aggression will not escalate and will remain in an average range.

Figure 3.

Child Development Project mean Grade 3 TRF Aggression scores by number of years of social rejection and level of early aggression.

We next examined reactive and proactive aggression outcomes. For Grade 3 (age 8) reactive aggression, significant main effects were found for both cumulative rejection, F(3, 460) = 7.51, p<.001, and kindergarten (age 5) reactive aggression, F(1, 460) = 9.92, p<.01. The cumulative Rejection × Kindergarten (age 5) reactive aggression interaction was not significant, F(3, 460) = 1.06, ns. In the prediction of Grade 3 (age 8) proactive aggression, the main effect of cumulative rejection, F(3, 462) = 8.15, p<.001, was significant, but there was not a significant main effect of kindergarten (age 5) proactive aggression, F(1, 462) = .78, ns, or a significant cumulative Rejection × Kindergarten (age 5) proactive aggression interaction, F(3, 462) = .98, ns.

Although the analyses of TRF Aggression suggest that the group of children who were initially nonaggressive do not become more aggressive following peer rejection, it is still possible that they might suffer other adverse reactions (e.g., growth in social withdrawal). The Grade 3 (age 8) TRF Withdrawal scale was subjected to the same ANOVA, with early rejection status, early aggression status, gender, race, cohort, and site as independent variables. All tests of main effects and interaction effects involving rejection yielded nonsignificant Fs less than 1.

These analyses raise the question of whether peer rejection moderates the effects of other early behaviors on later outcomes. It is plausible that peer rejection will exacerbate any problem for which a child is initially predisposed or at risk. The work of Rubin and colleagues (Rubin et al., 1991; Rubin & Mills, 1988) suggests that socially withdrawn children might react to peer rejection with increased social withdrawal or isolation (rather than aggression). This was found to be the effect of rejection on children’s behavior in contrived play groups (Dodge, 1983).

To test this possibility, we used a median split on kindergarten (age 5) TRF Social Withdrawal scores to create a group of children initially predisposed toward withdrawal and a group not so predisposed. ANOVA on Grade 3 (age 8) TRF Social Withdrawal scores, with kindergarten (age 5) rejected status and kindergarten (age 5) withdrawal status as factors, along with gender, race, cohort, and site revealed a significant main effect of kindergarten (age 5) social withdrawal status on Grade 3 (age 8) TRF Social Withdrawal scores, F(1, 473) = 17.26, p<.001, and a significant main effect of gender, F(1, 473) = 5.19, p<.05. However, there was no significant main effect of kindergarten rejection, F(1, 473) = 3.03, ns, or rejection by early withdrawal interaction, F(1, 473) < 1, ns, on Grade 3 (age 8) TRF Social Withdrawal scores. Panak and Garber (1992) have conducted additional work regarding effects of social rejection on internalizing outcomes. It remains possible that social rejection leads to other, unmeasured negative outcomes for nonaggressive children. The rest of our focus is on the effects of social rejection on later aggressive behavior.

These findings provide support for the hypothesis that the experience of being rejected by peers in early elementary school plays an incremental role in the later development of aggressive behavior problems, beyond the contributions made by factors leading to peer rejection in the first place. The causal role of rejection cannot be proven by correlational data, of course, because still other variables (e.g., physical attractiveness, verbal ability) might lead both to rejection and to growth in aggressive behavior.

In addition, these findings support the hypothesis that this effect is moderated by a child’s disposition toward aggression. Thus, it does not appear that peer rejection serves merely as an early marker of later behavior problems. Presuming that these direct and moderating effects are real, it makes sense to turn to our next question: What is the process through which the experience of peer rejection has an impact on later antisocial development?

Study 3

Numerous hypotheses regarding how peer rejection affects later antisocial behaviors have been suggested in the literature, although few empirical studies have been conducted to answer this question. Two concepts dominate the theoretical literature. The first hypothesis is that in rejecting a child and in excluding him or her from play, the peer group is denying the child important opportunities for social growth and the development of social skills. According to Piaget (1926/1955/1932/1965), Hartup (1983), and Youniss (1980), social cognitive skills develop during free exchange with a peer group in comfortable contexts. A child who is denied access to these contexts by a rejecting peer group will have difficulty developing these skills. In turn, the failure to develop social cognitive skills will enhance the likelihood of later antisocial behavior.

Two kinds of evidence consistent with this hypothesis have accumulated. First, several researchers have demonstrated that the peer group acts systematically to deny the rejected child opportunities for free and comfortable interaction. Putallaz and Wasserman (1990) observed that peers exclude rejected children from entry into the peer group. Hartup, Glazer, and Charlesworth (1967) found that peers provide little positive reinforcement to rejected children. Ladd (1983) observed that, relative to popular children, unpopular children end up interacting in smaller groups with younger and less skilled peers. Hymel, Wagner, and Butler (1990) found that peers hold attributional and memory biases about socially rejected children that lead them to deny play opportunities to rejected children. Thus, it is clear that social rejection by peers leads a child to experience a less comfortable context that might not be conducive to the development of social skills.

The second type of supporting research is the literature on social-cognitive and emotion-regulation correlates of social rejection. Rejected children perform less competently than average children at attending to and interpreting peer cues (Dodge & Feldman, 1990), at regulating emotion (Eisenberg et al., 1997), at social-problem-solving tasks (Nelson & Crick, 1999), at understanding appropriate display rules for behavior (Jones, Abbey, & Cumberland, 1998), and at behavioral expression of emotions (Hubbard, in press). All of these skills and patterns are hypothesized to develop during peer exchanges. Of course, cross-sectional correlational studies such as those described cannot tease apart the temporal effects of rejection on these skills versus the effect of these skills on the propensity to become rejected. Thus, the rationale for this hypothesis is strong, but the evidence in support of this hypothesis is indirect and weak. What is needed is a longitudinal study of the relation between rejection and social-information-processing skills and biases over time. One of the few such studies, by Egan, Monson, and Perry (1998), found that the experience of victimization by peers is associated with later decreases in evaluations that aggressive and assertive behavior by a child will be effective. Another study, by MacKinnon-Lewis, Rabiner, and Starnes (1999) found that low social acceptance is correlated with later beliefs that peers will be unfriendly.

The second hypothesized mechanism for the effect of rejection is a stress effect, that the emotional reaction that social rejection engenders in children leads to dysfunctional behavior. Being rejected by peers may lead a child to feel lonely, angry, and alienated. These emotions may lead the child to become biased in future attributions about the peer group that caused these feelings, which in turn may increase the likelihood of aggressive retaliation. Also, the child who has been chronically rejected may develop a sense of low self-efficacy and low behavioral competence, which may lead that child to escalate his or her behavior to the point of aggression to achieve desired outcomes. Asher, Parkhurst, Hymel, and Williams (1990) pointed out that these emotional reactions depend on cognitive responses to rejection. That is, they hypothesize that how one attributes the causes of one’s rejection will influence one’s behavioral response to that experience.

These two kinds of mechanisms are captured well in a framework of information processing about social rejection events. According to social-information-processing theory (Dodge, 1986), a child’s response to an event such as being rejected or rebuffed from peer play occurs as a function of a sequence of processing steps. These steps include attending to cues in the rejection stimulus, making an attribution about the rejection, generating responses to the event, imagining potential outcomes of one’s own behavioral responses to decide on a course of action, and behaviorally enacting a chosen response. These five steps neatly fit the two kinds of reactions to rejection proposed in the literature.

The experience of chronic social rejection may prevent a child from acquiring skills of attending to relevant social cues. This experience might also lead a child to develop hostile attributional biases about peer motives. A child who has been excluded from peer play might not acquire a response repertoire that includes competent responses, known as solution-generating skill deficits. This child might develop low self-efficacy for the outcomes of his or her own behavior. And this child might not get enough practice to develop skills in enacting competent behaviors. According to this theory, these processing skill deficits and biases in turn are likely to lead to dysfunctional behavior such as aggression. These hypotheses were tested in both of the previously described longitudinal samples.

Method

The 259 participants in the Social Development Project (described in Study 1) completed annual assessments of social-information-processing patterns about social rejection events. One of the important tenets of processing theory is that a child’s processing patterns are highly situation specific; therefore, we used measures of processing patterns that involve stimuli that are particularly suited to capturing a child’s reactions to being rejected by peers. We chose 12 stimulus situations involving rebuff from peer group participation, such as when peers tell a child that he or she cannot join them in a game. We created 12 scripts involving peer rebuff and had actors role-play 3 minute-long scenerios of each script (36 in all) that were videorecorded (see Dodge & Price, 1994). The intent of the peers in rejecting the child varied as hostile, benign, or ambiguous for each script. The 36 vignettes were placed into three sets of 12 vignettes each, with four trials of each intent for each set. We presented these scenarios to each child on videotape and asked the child to imagine being the protagonist who had been rejected by peers. We then asked questions of the child to assess his or her skills and patterns of processing rejection cues. From these interviews, we derived one internally consistent and reliable score for each of the five aspects of processing.

Encoding was assessed by asking children to describe what happened in the story. Responses were coded according to how much relevant information the child encoded (0 = no attention to relevant information, .5 = partial attention, 1 = clear attention to appropriate cues). Responses were averaged across vignettes to create a single encoding score (range = 0 to 1).

Attributions were coded based on children’s responses to the question: “Was the other child being mean or not being mean in this story?” Hostile bias was the number of times the child interpreted an ambiguous or nonhostile cue as being hostile (range = 0 to 8).

Children then were told the antagonist’s actual intention and were asked what they would do or say if the event portrayed in the vignette happened to them. Responses were coded as competent, aggressive, or inept. The proportion of aggressive responses generated by the child was calculated across vignettes.

For each vignette, children were then shown three response strategies (competent, aggressive, and inept) in counterbalanced order. Following the demonstration of each strategy, children were asked whether: (a) others would like them if they used that response, and (b) the other kids would let them play or stop bothering them if they did that. Responses were coded on a 4-point scale (1 = really sure no, 2 = a little sure no, 3 = a little sure yes, 4 = really sure yes). Children’s evaluation of aggressive responses was calculated by averaging across the two items and then across the 12 vignettes whether children indicated that aggressive responses would achieve desired interpersonal and instrumental outcomes.

Finally, children were told a competent response and were asked to show the interviewer how they would enact the competent response from the story. Their enactment of the response was rated by the interviewer on a 5-point scale from 0 (very incompetent) to 4 (very competent). A single enactment score was created by averaging across the 12 vignettes.

Intercoder agreement on scoring was assessed by having a second coder present during the interview for 52 participants (20% of sample). Independent coder agreement was 90% for encoding, 100% for attributions, 84% for response generation, 100% for response evaluation, and 83% for enactment. Internal consistency of responses was calculated within each version that a child received and was highly significant (p<.001) for each variable. The median Cronbach’s alpha was .63.

Results and Discussion

Correlations among all variables are listed in Table 1. These analyses indicate that social preference scores in Year 1 were significantly correlated with three of the five processing scores in Year 4, and three of the five processing scores in Year 4 were significantly correlated with aggression scores in Year 5.

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for Social Development Project Sample

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | N | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Yr 1 social preferencea | .35*** | −.41*** | −.31*** | −.29*** | −.26*** | −.31*** | −.41*** | −.31*** | −.37*** | −.38*** | .05 | −.01 | −.15* | .05 | .15* | .08 | −.17* | −.23** | .04 | .16* | 259 | .00 | .98 |

| 2. Yr 2 social preferencea | – | −.32*** | −.38*** | −.26*** | −.37*** | −.36*** | −.32*** | −.28*** | −.38*** | −.32*** | .03 | .07 | −.05 | .01 | .11 | .13 | −.11 | −.17* | .01 | .08 | 220 | .03 | .87 |

| 3. Yr 1 aggressionb | – | .50*** | .50*** | .52*** | .54*** | .66*** | .68*** | .79*** | .73*** | −.08 | .04 | .08 | .02 | −.16* | −.03 | .07 | .11 | −.08 | −.22** | 258 | 4.21 | 2.13 | |

| 4. Yr 2 aggressionb | – | .35*** | .49*** | .34*** | .48*** | .37*** | .47*** | .44*** | −.10 | .05 | .03 | .01 | −.09 | −.08 | .12 | .13 | −.09 | −.11 | 217 | 4.17 | 2.26 | ||

| 5. Yr 3 aggressionb | – | .56*** | .65*** | .48*** | .41*** | .53*** | .41*** | −.12 | .10 | .17* | .00 | .05 | −.06 | .10 | .24** | −.14 | −.12 | 193 | 6.10 | 9.31 | |||

| 6. Yr 4 aggressionb | – | .49*** | .55*** | .36*** | .53*** | .39*** | −.16* | .08 | .02 | .11 | −.13 | −.03 | .11 | .13 | −.14 | −.25** | 190 | 6.00 | 9.68 | ||||

| 7. Yr 5 aggressionb | – | .53*** | .44*** | .57*** | .39*** | −.23** | .06 | .09 | −.03 | −.16* | −.09 | .10 | .20** | −.18* | −.20** | 184 | 7.11 | 9.83 | |||||

| 8. Yr 1 aggressiona | – | .38*** | .60*** | .49*** | −.14* | .06 | .09 | .01 | −.14* | −.07 | .16* | .15* | −.11 | −.28*** | 259 | 2.52 | 3.58 | ||||||

| 9. Yr 1 entryb | – | .69*** | .72*** | −.06 | .02 | .06 | −.05 | −.06 | −.06 | .01 | .16* | .03 | −.10 | 258 | 2.68 | .85 | |||||||

| 10. Yr 1 authority problemsb | – | .79*** | −.10 | −.02 | .11 | −.03 | −.12* | −.10 | .11 | .16* | −.08 | −.19** | 258 | 2.45 | 1.01 | ||||||||

| 11. Yr 1 social norm problemsb | – | −.06 | .01 | .10 | −.03 | −.16* | −.10 | .18* | .12 | .02 | −.20** | 258 | 2.18 | .69 | |||||||||

| 12. Yr 1 encodingc | – | −.05 | .02 | −.12* | .23*** | .36*** | −.16* | −.01 | .04 | .22** | 259 | .89 | .11 | ||||||||||

| 13. Yr 1 attributionc | – | .13* | .00 | .09 | .02 | .18* | .04 | −.09 | .04 | 259 | .51 | .35 | |||||||||||

| 14. Yr 1 response generationc | – | .08 | .03 | .02 | .07 | .21** | .00 | .14 | 259 | .44 | .47 | ||||||||||||

| 15. Yr 1 response evaluationc | – | −.02 | −.07 | −.02 | −.05 | .37*** | −.03 | 259 | .23 | .05 | |||||||||||||

| 16. Yr 1 enactmentc | – | .22** | −.09 | −.01 | .08 | .34*** | 259 | 2.20 | .57 | ||||||||||||||

| 17. Yr 4 encodingc | – | −.30*** | .03 | .09 | .25*** | 199 | .99 | .03 | |||||||||||||||

| 18. Yr 4 attributionc | – | .02 | −.08 | −.18* | 199 | .28 | .31 | ||||||||||||||||

| 19. Yr 4 response generationc | – | −.10 | .11 | 199 | .34 | .41 | |||||||||||||||||

| 20. Yr 4 response evaluationc | – | −.04 | 199 | .22 | .04 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 21. Yr 4 enactmentc | – | 199 | 2.57 | .48 |

Note. Sample size for correlations ranges from 167 to 259.

Peer report.

Teacher report.

Child report.

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

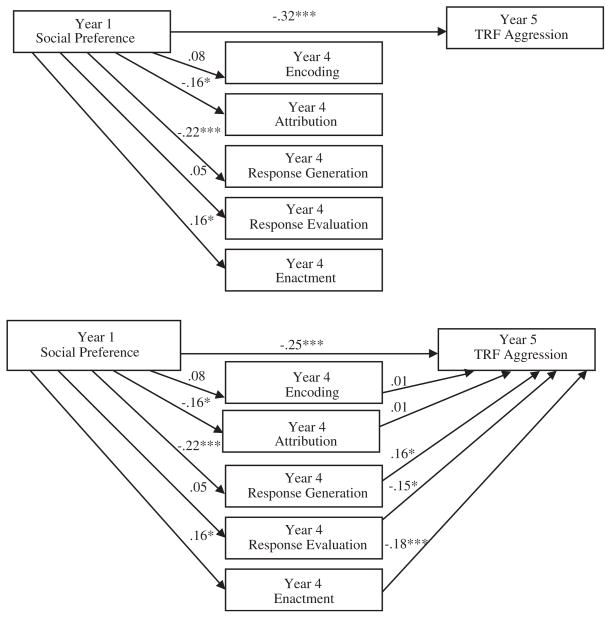

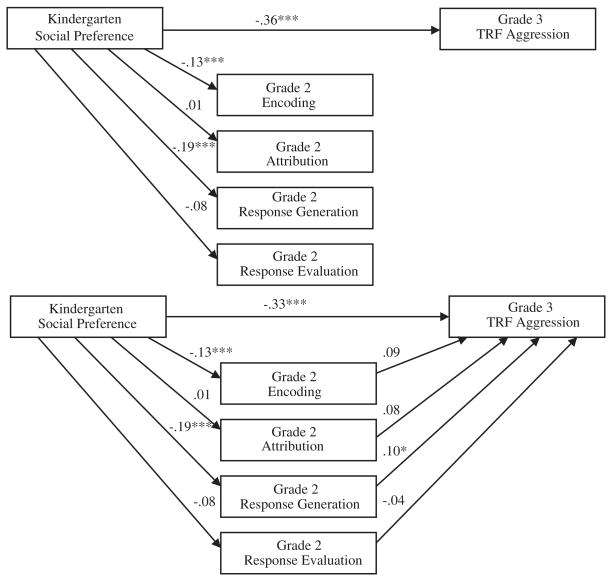

We tested the mediational hypothesis through a series of path analyses using Amos 4.0 (Arbuckle, 1994). Social preference scores in Year 1 were used to predict a set of five processing scores in Year 4 and TRF Aggression scores in Year 5. Mediation as defined by Baron and Kenny (1986) requires several kinds of findings: (a) a predictor must be directly related to both an outcome and a mediator; (b) the mediator must be directly related to the outcome; and (c) after parsing the effect of the mediator, the association between the predictor and outcome must be attenuated. Figure 4A depicts a direct effects model showing that the first of these criteria was met. Social preference scores in Year 1 significantly predicted TRF Aggression scores in Year 5 and how children processed rejection cues in Year 4. Significant processing outcomes of early low social preference included later hostile attribution biases, skill deficits in generating competent solutions to rejection dilemmas, and skill deficits in enactment of competent behaviors. The direct effects model fit the data well as indicated by Bentler’s Comparative Fit Index = .99, despite a significant model chi-square, χ2(15) = 54.42, p<.001.

Figure 4.

Social Development Project direct effects model with early social preference as a predictor of later social-information-processing patterns and aggression (top). Model with social information processing mediators of the relation between early social preference and later aggression in the Social Development Project (bottom). Numbers shown are standardized path coefficients. *p<.05. ***p<.001.

The next model added paths from the rejection-processing mediators in Year 4 to Year 5 TRF Aggression. As shown in Figure 4B, Year 4 response-generation skill deficits, low self-efficacy in evaluating the probable outcomes of one’s own behavior, and behavioral enactment skill deficits provided nonredundant increments in this prediction. Year 1 social preference remained a significant predictor of Year 5 TRF Aggression after adding the paths through the mediating variables. However, the fit of the model improved significantly, χ2 change(5) = 14.57, p<.05. This pattern constitutes evidence for partial mediation of the effect of early preference on later aggression, according to the criteria set forth by Baron and Kenny (1986). The model accounted for 18%, 1%, 3%, 5%, 1%, and 2% of the variance in aggression, encoding, attributions, response generation, response evaluation, and enactment, respectively. The total effect of social preference in Year 1 on Year 5 aggression was −.32 (10% of variance). The direct effect of early social preference accounted for 61% of this total effect, and the intervening development of biased and deficient patterns of processing rejection events indirectly accounted for 39% of the total effect.

Thus far, we have counted on the temporal differences in time of data collection to refute the possibility that causal directions might proceed in the opposite order, that is, that processing patterns might influence social preference scores. In a last path analysis conducted using hierarchical linear regression techniques, we first added the five Year 1 processing variables to the prediction. This variable set significantly predicted Year 5 aggression, accounting for 8% of the variance. When entered next, the Year 1 social preference scores significantly incremented this prediction by an additional 6%. Finally, the Year 4 processing variables significantly incremented this prediction even further, accounting for yet another 7% of the variance in Year 5 aggression.

Two points must be reiterated. First, the experience of low social preference by peers significantly affected later processing patterns, even when early processing patterns were taken into account. That is, low social preference scores led to a change in processing patterns over time. Second, this change in processing patterns that occurred as an outcome of early rejection accounted for significant predictions of Year 5 aggression scores.

Study 4

We sought to replicate the mediation findings from the Social Development Project by returning to analyses of data from the previously described Child Development Project.

Method

The 585 participants in the Child Development Project completed social-information-processing measures as part of their annual assessments. Trained interviewers visited children in their homes during the summer following second grade (age 7). As in the Social Development Project, encoding, attributions, and response generation were measured following the presentation of 12 video vignettes depicting peer entry situations. Alphas for responding were .64, .73, and .89, respectively. In a format different from the Social Development Project, after each video vignette, children were shown alternative strategies (competent, aggressive, and inept) for dealing with the situation. Response evaluation was assessed by asking children to rate whether each alternative strategy was a good or bad thing to say or do (1 = very bad, 2 = bad, 3 = good, 4 = very good). Aggressive response evaluation was scored as the average of this single item across the 12 vignettes (alpha = .91). Response enactment was not measured in the Child Development Project. These four measures of social information processing were used in conjunction with the previously described social preference and TRF Aggression measures to replicate the mediation analyses.

Results and Discussion

Correlations among all variables are listed in Table 2. These analyses indicate that social preference scores in kindergarten (age 5) were significantly correlated with two of the four processing scores in Grade 2 (age 7), and two of the four processing scores in Grade 2 (age 7) were significantly correlated with aggression scores in Grade 3 (age 8).

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for Child Development Project Sample

| Variable No. | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | N, M(SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. K social preferencea | .49*** | .40*** | .43*** | −.38*** | −.40*** | −.35*** | −.36*** | −.50*** | .30*** | −.10* | −.23*** | −.22*** | −.13** | .02 | −.20*** | −.08 | 566, .15(.97) |

| 2. Grade 1 social preferencea | – | .44*** | .49*** | −.35*** | −.46*** | −.42*** | −.39*** | −.37*** | .21*** | .04 | −.07 | −.19*** | −.12* | .02 | −.14** | −.11* | 467, .21(.90) |

| 3. Grade 2 social preferencea | – | .49*** | −.27*** | −.39*** | −.42*** | −.33*** | −.28*** | .17*** | −.03 | −.18*** | −.23*** | −.21*** | .02 | −.12* | −.12* | 483, .16(.95) | |

| 4. Grade 3 social preferencea | – | −.35*** | −.32*** | −.35*** | −.42*** | −.31*** | .17*** | −.01 | −.13** | −.26*** | −.19*** | −.02 | −.17** | −.09 | 443, .07(.95) | ||

| 5. Kind aggressionb | – | .57*** | .56*** | .53*** | .57*** | −.15*** | .08* | .14** | .13** | .07 | .05 | .10* | .03 | 578,6.68(10.24) | |||

| 6. Grade 1 aggressionb | – | .57*** | .57*** | .54*** | −.16*** | −.05 | .06 | .14** | .14** | .04 | .10* | −.02 | 532,8.14(11.94) | ||||

| 7. Grade 2 aggressionb | – | .62*** | .51*** | −.16*** | −.02 | .06 | .14** | .14** | .01 | .17** | −.03 | 521,8.49(12.60) | |||||

| 8. Grade 3 aggressionb | – | .51*** | −.18*** | .00 | .11* | .31*** | .14** | .07 | .16** | .00 | 498,5.55(8.54) | ||||||

| 9. K aggressiona | – | −.14** | −.05 | .03 | .09* | .11* | .07 | .06 | .01 | 566,1.76(1.88) | |||||||

| 10. K school performanceb | – | −.22*** | −.33*** | −.22*** | −.13** | .08 | −.16** | −.13** | 553,6.25(2.14) | ||||||||

| 11. K internalizingb | – | .81*** | .34*** | .09* | −.02 | .01 | .13** | 578,4.03(4.99) | |||||||||

| 12. K withdrawalb | – | .44*** | .16** | −.02 | .06 | .11* | 578,1.84(2.82) | ||||||||||

| 13. Grade 3 withdrawalb | – | .18*** | −.05 | .09 | .06 | 498,1.92(2.67) | |||||||||||

| 14. Grade 2 encodingc | – | −.11* | .12* | .12** | 450,1.09(.15) | ||||||||||||

| 15. Grade 2 attributionsc | – | −.20*** | −.13** | 450, .62(.15) | |||||||||||||

| 16. Grade 2 response generationc | – | .13** | 450, .22(.28) | ||||||||||||||

| 17. Grade 2 response evaluationc | – | 450, .22(.05) |

Note. Sample size for correlations ranges from 376 to 578.

Peer report.

Teacher report.

Child report.

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

A direct effects model tested using path analyses as described earlier revealed that kindergarten social preference scores significantly predicted Grade 3 (age 8) TRF Aggression and children’s social-information-processing patterns in second grade (age 7; see Figure 5A). Kindergarten (age 5) social preference scores independently predicted encoding problems and deficits in response generation in second grade (age 7). A Comparative Fit Index of .99 indicated that the direct effects model fit the data well, despite a significant model chi-square, χ2(10) = 51.09, p< .001.

Figure 5.

Child Development Project direct effects model with early social preference as a predictor of later social-information-processing patterns and aggression (top). Model with social-information-processing mediators of the relation between early social preference and later aggression in the Child Development Project (bottom). Numbers shown are standardized path coefficients. *p<.05. ***p<.001.

Paths from the social-information-processing mediators to Grade 3 (age 8) TRF Aggression were added to test a mediated model. As shown in Figure 5B, social-information-processing patterns in Grade 2 (age 7) predicted Grade 3 (age 8) TRF Aggression. Response generation was the only mediator to make an independent contribution to this prediction. The path between social preference and aggression remained significant, but the fit of the mediated model was significantly better than the fit of the direct effects model, χ2 change(4) = 10.39, p<.05. The model accounted for 15%, 2%, 0%, 4%, and 1% of the variance in aggression, encoding, attributions, response generation, and response evaluation, respectively. The total effect of kindergarten social preference on Grade 3 TRF Aggression was −.36 (13% of variance). Of this total effect, 84% was accounted for by the direct effect of early social preference on later aggression, and 16% was accounted for by the indirect path through the development of social-information-processing problems. Mediation occurred specifically through problems with response generation.

Analyses were repeated for the reactive and proactive aggression scores. Findings were similar to those for TRF Aggression, except that for Grade 3 (age 8) reactive and proactive aggression, mediation occurred through problems with encoding as well as through response generation.

To test for possible gender differences in the mediating role of social-information-processing patterns, we tested both the direct effects model and the mediated model for boys and girls separately. We compared the fit of each model when the paths were constrained to be equal across genders with alternative models in which the paths were allowed to vary by gender. The fit of these models did not significantly differ, χ2 change (5) = 7.34 and χ2 change (9) = 9.47, ns, respectively. Thus, the mediation of the association between social preference and aggression by social-information-processing patterns did not differ across boys and girls.

General Discussion

Four important findings emerge from the studies reported here. First, social rejection by the peer group in early elementary school is associated with later antisocial behavior, even after controlling for previous antisocial behavior. Second, this effect of peer rejection holds only among children who are initially above the median in aggressive behavior. Third, these effects hold equally well for boys and girls. Fourth, a significant portion of this effect of peer rejection is accounted for by the child’s tendency to develop biased patterns of processing social information as a function of having been rejected by peers.

Effects of Social Rejection on Behavioral Development

We began with the hypothesis that the phenomenon of social rejection by peers during early elementary school should be conceptualized as a stressful life experience that exacerbates later antisocial development. This hypothesis has been supported by the findings from two independent samples that include boys and girls from diverse ethnicity and geographic regions, to the limits that uncontrolled descriptive longitudinal research can support such a hypothesis. We found that social rejection plays an incremental role in the development of later aggression, even after controlling for previous levels of aggressive behavior. This effect is stronger for reactive aggression, which is a response to stress or provocation, than for proactive aggression, which is instrumental behavior that may have little to do with the provocative stress of peer rejection.

We tested the hypothesis that this effect is merely an artifact of conjoint association with third variables, such as a range of other behaviors that might lead to rejection and the peer nominator as a source of ratings about a child. However, no attempt to discount the effect of peer rejection on later antisocial behavior was successful. This finding is striking because it suggests that peers are not merely observers of a child’s developmental psychopathology; in their capacity to accept or reject a child, they become active players in that child’s development.

Moderation of the Effect of Social Rejection

The second important finding is that the effect of social rejection varies across types of children. Social rejection acts as a stressor to exacerbate antisocial development only among children who are initially predisposed toward aggression, that is, above the median. Among children who are below the median in initial levels of aggression, the experience of social rejection does not increase aggressive behavior, nor does it exacerbate withdrawal. It is unclear whether it has any negative impact at all. In contrast, among children who are initially above the median in aggressive behavior, the experience of social rejection has a strong impact on increasing aggressive behavior.

Two important caveats must be added to these conclusions. First, it is possible that exacerbation of withdrawal would be found during adolescence, when withdrawn behavior becomes increasingly non-normative and is associated with psychopathology. Second, perhaps social rejection has other, unmeasured, effects on nonaggressive children, such as increasing depression, academic failure, or psychosomatic symptoms.

The positive frame for these findings is that the experience of even just a minimal level of stable positive social preference by peers during childhood can have strong buffering effects on the development of later antisocial psychopathology. Children who otherwise are inclined toward aggressive behavior can be largely deterred in that path if they can escape social rejection in the normative peer context. Some theorists like to emphasize the role parents play in lifting their child toward positive social adjustment outcomes. The perspective that this work provides is that positive peer relationships play a crucial role as well in deflecting aggressive children away from aggressive trajectories.

Gender and Social Rejection

The third important finding is that the effects of social rejection do not differ across boys and girls. Rejection appears to act as a stressor for both groups. An important caveat to this conclusion is that the current measures were restricted to general, reactive, and proactive types of aggressive behavior. Because data collection began in 1987, we were not able to take advantage of Crick and Grotpeter’s (1995) distinction between overt and relational aggression. It is possible that peer rejection exacerbates overt aggression in boys and relational aggression in girls, but the test of that hypothesis awaits further inquiry. The current findings, however, do support the importance of intervening to prevent social rejection and to mitigate its impact in both boys and girls.

Mediation of the Effect of Social Rejection

The fourth important finding is support for the hypothesis that one mechanism through which social rejection affects later adjustment is by affecting the way children process social information. It had been established previously (e.g., Dodge et al., 1990) and has been replicated here that initial problems and biases in social information processing contribute to behavior that leads children to become rejected by peers in early elementary school. Social rejection, in turn, alters the way children process information during future peer interactions. That is, social rejection alters the way children attend to social cues and solve social problems, by increasing their hypervigilance to hostile cues and their tendency to generate aggressive responses to peer dilemmas and their skill in enacting those responses. The effect of these acquired patterns of processing the social world is to exacerbate the child’s likelihood of acting aggressively toward peers.

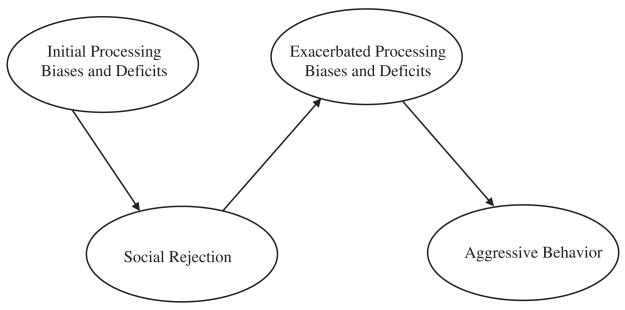

These findings can be summarized in the model of how the experience of social rejection by peers leads to later aggressive behavior problems shown in Figure 6. First, it appears that initial processing biases and deficits contribute to a child’s becoming rejected by the peer group. A child who displays hostile attributional biases, who is unable to generate competent solutions to interpersonal dilemmas, and who is unskilled at enacting competent behavioral responses is at risk for becoming socially rejected. Second, this stressful experience of being socially rejected by one’s peers and being denied opportunities for social engagement in early elementary school has long-term effects of exacerbating a child’s processing biases and deficits. As a consequence of being rejected, a child is increasingly likely to attribute hostile intent to peers, to generate inappropriately aggressive responses to social rejection dilemmas, and to be unskilled at enacting competent behavioral responses. Finally, these processing biases and deficits that were acquired partially as a consequence of being rejected by the peer group lead to later chronic aggressive behavior problems.

Figure 6.

Conceptual model of how social rejection leads to later aggression.

Conclusions and Implications

The major theoretical basis for this research was that social rejection by peers acts as a social stressor that increases a tendency to react aggressively among children who are so disposed. Although this explanation is consistent with the three major findings and is plausible, a modified and equally plausible explanation is that social acceptance by peers inhibits antisocial development in aggressive children. The difference between these two explanations is the mechanism of action: Does antisocial behavior grow among children who have experienced the stress of peer rejection, or does antisocial behavior diminish among aggressive children who experience peer acceptance? Normal behavioral development involves a decrease in the rate of aggressive behavior across age, as a child learns skills of cooperation, empathy, perspective taking, intention-cue detection, social problem solving, and response evaluation that inhibit aggressive behaviors (Coie & Dodge, 1998). It is likely that acceptance in a peer group enables a child to learn these skills. It may be that the effects reported here represent the rejected child’s lack of exposure to positive peer group influences that inhibit aggressive behavior rather than a catalytic exacerbation of antisocial tendencies. Because the major measure of peer experience used here was the dimensional score ranging from positive to negative peer social preference, and all attempts to discern a nonlinear effect of this score were unsuccessful, the findings are consistent with either explanation. Future research is necessary to tease apart whether the stressful aspect of active rejection by peers or the lack of exposure to important peer group experiences is responsible for the effects reported here.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this research were presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, March 1993, New Orleans, Louisiana. The Child Development Project has been funded by grants MH42498 and MH56961 from the National Institute of Mental Health and HD30572 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The Social Development Project has been funded by grants BNS89089035 from the National Science Foundation and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. We are grateful to the parents, children, and teachers who participated in this research and to Janice Brown, Kimberly Skow, Douglas Alexander, and numerous students and coworkers for their contributions to this work.

References

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. Manual for the Teacher’s Report Form and the Teacher Version of the Child Behavior Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle J. AMOS Users’s Guide. Chicago, IL: Small Waters Corp; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Asher SR, Coie JD, editors. Peer rejection in childhood. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Asher SR, Parkhurst JT, Hymel S, Williams GA. Peer rejection and loneliness in childhood. In: Asher SR, Coie JD, editors. Peer rejection in childhood. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 253–273. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Freeland CB, Lounsbury ML. Measurement of infant difficultness. Child Development. 1979;50:794–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Smoot DL, Aumiller K. Characteristics of aggressive-rejected, aggressive (non-rejected), and rejected (nonaggressive) boys. Child Development. 1993;64:139–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Wargo JB. Predicting the longitudinal course associated with aggressive-rejected, aggressive (nonrejected), and rejected (nonaggressive) status. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:669–682. [Google Scholar]

- Burks VS, Dodge KA, Price JM, Laird RD. Internal representational models of peers: Implications for the development of problematic behavior. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:802–810. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.3.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AH, Van Ijzendoorn HW, Van Lieshout CF, Hartup WW. Heterogeneity among peer-rejected boys: Subtypes and stabilities. Child Development. 1992;63:893–905. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD. The impact of negative social experience on the development of antisocial behavior. In: Kupersmidt J, Dodge KA, editors. Peer relations in childhood: From development to intervention to public policy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA. Aggression and antisocial behavior. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, editors. Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 3: Social, emotional, and personality development. 5. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 779–862. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA, Coppotelli HA. Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:557–569. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Lochman JE, Terry R, Hyman C. Predicting early adolescent disorder from childhood aggression and peer rejection. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:783–792. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowen EL, Pederson A, Babigian H, Izzo LD, Trost MA. Long-term follow-up of early detected vulnerable children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1973;41:438–446. doi: 10.1037/h0035373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA. A social information processing model of social competence in children. In: Perlmutter M, editor. Minnesota Symposium in Child Psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1986. pp. 77–125. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA. Behavioral antecedents of peer social status. Child Development. 1983;54:1386–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science. 1990;250:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.2270481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Coie JD. Social information-processing factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:1146–1158. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.6.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Feldman E. Issues in social cognition and sociometric status. In: Asher SR, Coie JD, editors. Peer rejection in childhood: Origins, consequences, and intervention. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 119–155. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, McClaskey CL, Feldman E. A situational approach to the assessment of social competence in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:334–353. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Price JM. On the relation between social information processing and socially competent behavior in early school-aged children. Child Development. 1994;65:1385–1397. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan S, Monson T, Perry D. Social-cognitive influences on change in aggression over time. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:996–1006. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]