Abstract

Allyl sulfide addition-fragmentation chain transfer was employed concurrently with the radical-mediated formation of a thiol-ene network to enable network adaptation and mitigation of polymerization-induced shrinkage stress. This result represents the first demonstration of simultaneous polymerization and network adaptation in covalently crosslinked networks with significant implications for the fabrication of low stress polymer networks. For comparison, analogous networks incorporating propyl sulfide moieties, incapable of addition-fragmentation, were synthesized and evaluated in parallel. At the highest irradiation intensity, the allyl sulfide-containing material demonstrated a more than 75% reduction in the final stress when compared with the propyl sulfide-containing material. Analysis of the conversion evolution revealed that allyl sulfide addition-fragmentation decreased the polymerization rate owing to thiyl radical sequestration. Slow consumption of the allyl sulfide functional group suggests that intramolecular homolytic substitution occurs by a step-wise, rather than concerted, mechanism. Simultaneous stress and conversion measurements demonstrated that the initial stress evolution was identical for both the allyl and propyl sulfide-containing materials but diverged after gelation. While addition-fragmentation chain transfer was found to occur throughout the polymerization, its effect on the stress evolution was concentrated towards the end of polymerization when network rearrangement becomes the dominant mechanism for stress relaxation. Even after the polymerization reaction was completed, the polymerization-induced shrinkage stress in the allyl sulfide-containing material continued to decrease, exhibiting a maximum in the stress evolution and demonstrating the potential for continuing, longer term stress relaxation.

Introduction

Rapid conversion of vinyl monomers to polymer, common in photopolymerization reactions,1 is typically accompanied by significant volume shrinkage, effecting shrinkage stress that is frequently detrimental to both mechanical and optical material properties in applications including coatings,2 adhesives,3 lenses,4, 5 and dental materials.6-8 In principle, polymerization-induced shrinkage stress is dissipated by viscous flow preceding gelation and accumulates after the formation of an incipient gel. When the reaction reaches final conversion, the stress becomes irreversibly set by the network structure.

There are several strategies for combating the deleterious effects of shrinkage stress in rapid free-radical polymerizations. One common mitigation approach is the minimization of polymerization shrinkage, achievable through a variety of means. Oligomeric polymerizable species have been used to reduce polymerization shrinkage and subsequent shrinkage as the concentration of reactive species is low.9 Additionally, ring-opening polymerizations, such as those employing epoxy10 or spiro11 compounds, and polymerization-induced micro-phase separation12, 13 have shown great potential to reduce volume shrinkage. However, upon full conversion to a chemical gel, there are very few mechanisms to alleviate shrinkage stress without effecting irreversible network degradation.

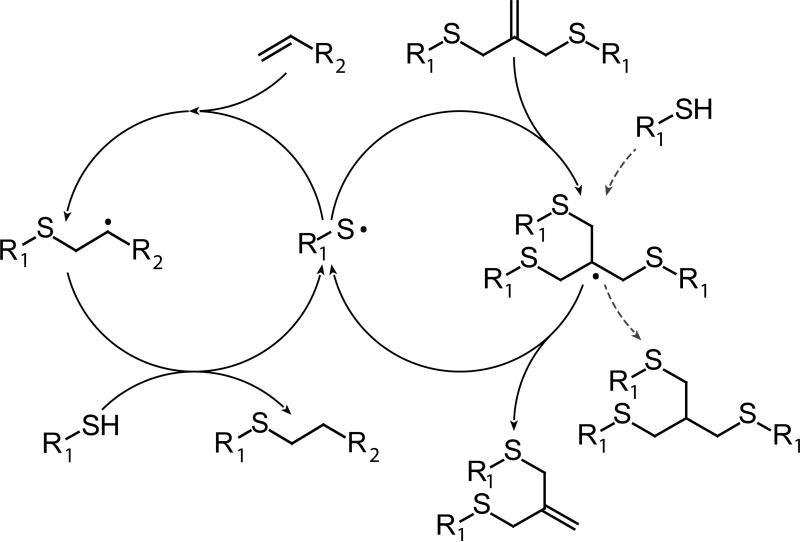

In previous work, post-polymerization stress relief was demonstrated by the introduction of radical species into a network containing allyl sulfide functionalities.14 Allyl sulfide addition-fragmentation (i.e., intramolecular homolytic substitution, SH2′)15, 16 has been utilized in a variety of synthetic schemes,17, 18 including methods for synthesizing low-polydispersity linear polymers.19-21 Incorporation of the allyl sulfide functionality into a chemical network allows for bond rearrangement via addition-fragmentation chain transfer. This reaction preserves the concentration of both the allyl sulfide and thiyl radical reactants, which subsequently participate in further addition-fragmentation events (see Scheme 1). This addition-fragmentation reaction cascade, where an active center effectively diffuses throughout the network, enables a global reduction in stress without concomitant network degradation.

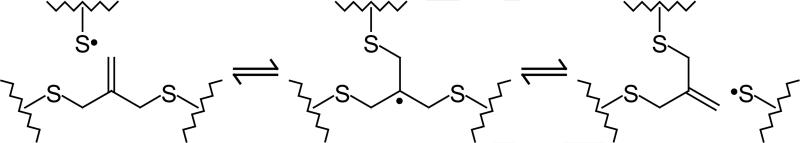

Scheme 1.

Thiyl radical addition to and subsequent fragmentation of an allyl sulfide functionality, demonstrating a tris(methyl sulfide) radical intermediate and rearrangement of bonds, where the zig-zag lines represent the greater polymer network. Here, the network topology is adaptable, while maintaining invariant reactant and product concentrations, and hence crosslink density.

Radical-mediated photopolymerizations of mercaptan and electron-rich vinyl monomers (i.e, thiol-ene photopolymerizations) have received much attention owing to their low shrinkage stress relative to the commonly utilized (meth)acrylate chain-growth photopolymerizations. Thiol-ene polymerizations proceed via a step-growth mechanism whereby propagation and chain transfer reactions alternate (Scheme 2).22, 23 This mechanism results in geometric molecular weight growth, significantly delaying the gel-point conversion when compared to that of typical chain-growth free-radical mechanisms.24, 25

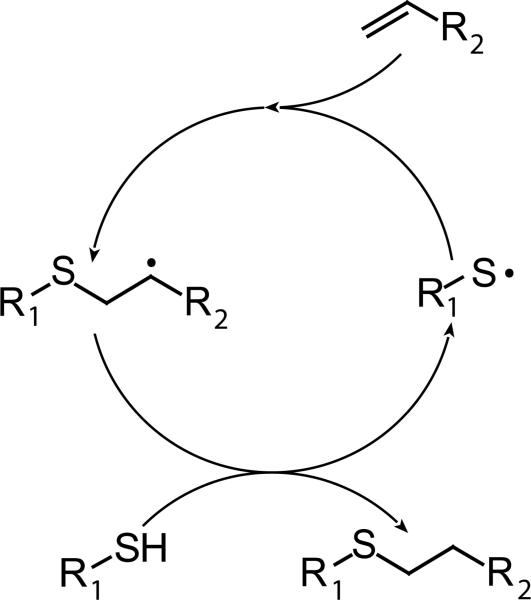

Scheme 2.

The thiol-ene polymerization mechanism where the thiyl radical adds to a vinyl functional group followed by hydrogen abstraction from a thiol functional group, completing the cycle and forming a carbon-carbon single bond. In the ideal mechanism, chain transfer and addition steps alternate and proceed at the same overall rate.

Here, allyl sulfide addition-fragmentation is demonstrated to bring about stress relief during-polymerization, particularly in conjunction with thiol-ene chemistry. The two active radical species in a thiol-ene polymerization are the carbon-centered radical, which abstracts a hydrogen from a thiol group, and the sulfur-centered radical, which adds to a carbon-carbon double bond. While the allyl sulfide moiety is a rather poor reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) agent with respect to carbon-centered radicals,19 it readily reacts with thiyl radicals generated within the thiol-ene polymerization chemistry.26 Thus, when the thiyl radical adds to the allyl sulfide carbon-carbon double bond, addition-fragmentation occurs, yielding a change in network topology without a net change in reactive species (see Scheme 1). Here, we explore the effect of reversible allyl sulfide addition-fragmentation chain transfer during a thiol-ene photopolymerization on the evolution of polymerization-induced shrinkage stress. For comparison, an analogous propyl sulfide monomer, incapable of addition-fragmentation and the corresponding relaxation, was synthesized and polymerized under identical conditions. The resultant network should exhibit similar shrinkage, crosslink density, and homogeneity when compared with the allyl sulfide-containing material, allowing verification that stress relief is indeed coupled to the addition-fragmentation process and confirming the proposed stress relaxation mechanism.

Experimental

Characterization

Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) was performed in triplicate using a TA Instruments Q800 scanning at 1 °C/min from −80 °C to 100 °C at a frequency of 1 Hz and a strain of 0.1% in tension. The crosslink density was estimated from the elastic modulus, E′, determined in the linear rubbery regime, which scales as the number of crosslinks per volume in accordance with rubbery elasticity theory.27 The glass transition temperature (Tg) was assigned as the temperature at the tan δ curve maximum.

Polymerization conversion studies were performed on formulated resin sandwiched between two glass slides separated by 50 μm thick spacers and irradiated in situ using a high pressure mercury vapor short arc lamp (EXFO Acticure 4000) equipped with a 365 nm narrow bandpass filter. Light intensity was measured using a radiometer equipped with a GaAsP detector (International Light IL1400A — model SEL005), a wide bandpass filter (model WBS320) and a quartz diffuser (model W). Conversions of thiol, vinyl-ether, and allyl sulfide functional groups were determined using infrared (IR) spectroscopy and monitoring the peak areas centered at 2570 cm−1 (PETMP thiol — S-H stretch), 3116 cm−1 (MDTVE and MeDTVE vinyl ether — C=C-H stretch), and 3077 cm−1 (MDTVE allyl — C=C-H stretch), respectively, using a Nicolet Magna-IR 750 Series II FTIR spectrometer. Spectra at a resolution of 2 cm−1 were collected at a rate of five every two seconds. Deconvolution of the allyl and vinyl ether peaks for samples containing MDTVE was performed by subtracting the propyl sulfide-containing analogue spectrum from the allyl sulfide-containing spectrum, thus isolating the allyl absorption. All conversion samples were formulated and measured in triplicate, and the presented data represent the mean of three runs where the standard errors were much smaller than the data points on the figures.

Simultaneous polymerization stress and functional group conversion measurements were performed using a cantilever-type tensometer (American Dental Association Health Foundation) coupled with an IR spectrometer via optical fibers as described in the literature.28 Briefly, the resin was introduced into a 1 mm gap between two 6 mm diameter quartz rods, one of which was attached to an aluminum bar cantilever and the other to a solid base. The quartz rod ends were carefully cleaned and treated with 3-mercaptopropyltrimethoxysilane to ensure adhesion at the resin-quartz interface.29 The sample was irradiated through one of the quartz rods, and the tensile force developed by the sample shrinkage during polymerization was determined by monitoring the aluminum bar deflection via a linear differential variable transformer (LDVT). Prior to the measurement, the deflection was calibrated using a force transducer. This calibration constant (i.e., the beam compliance) and the quartz rod area were used to convert the LDVT readings to stress measurements. Optical fibers were positioned to carry an infrared signal to and from an infrared spectrometer transverse through the sample. The vinyl ether conversion was determined by monitoring the peak area centered at 6185 cm−1 (C=C-H first overtone stretch), throughout the polymerization time; this peak was moderately overlapped by the allyl sulfide peak but was readily deconvoluted using Gaussian fitting. All polymerizations were performed at ambient temperature.

Materials

3-Mercaptopropyltrimethoxysilane was purchased from Gelest. 3-Chloro-2-chloromethyl-1-propene (96%), potassium ethyl xanthogenate (97%), 2-chloroethyl vinyl ether (95%), sodium bromide (>99%), ethylenediamine (>98%) and sulfuric acid (98%) was purchased from Fisher Scientific. 2-Methyl-1,3-propanediol (99%) and sodium metal (99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Pentaerythritol tetra(3-mercaptopropionate) (PETMP — shown in Scheme 3a) and Irgacure 184 (1-hydroxycyclohexyl-phenyl-ketone) were obtained from Evans Chemetics and Ciba Specialty Chemicals, respectively, and were used without further purification.

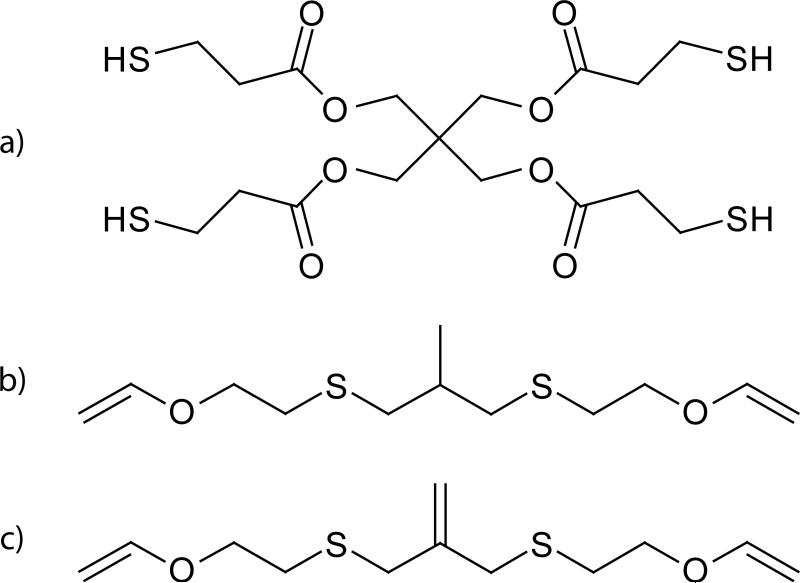

Scheme 3.

Mercapto- and vinyl-based monomers used in this study: a) PETMP, b) MeDTVE, and c) MDTVE.

Synthesis of 2-methylpropane-1,3-di(thioethyl vinyl ether) (MeDTVE — Scheme 3b)

2-Methyl-1,3-dibromopropane was synthesized following a modified procedure from literature,30 and the synthesis of 2-methyl-1,3-dimercaptopropane and subsequent synthesis of 2-methylpropane-1,3-di(thioethyl vinyl ether) followed the procedure found in references 31 and 32. Synthesis of these compounds is summarized below:

Synthesis of 2-methyl-1,3-dibromopropane

258 g (2.5 mol) of sodium bromide was added to 225 ml of water in a 2 L round bottom equipped with a reflux condenser while stirring. 90.12 g (1 mol) of 2-methyl-1,3-propanediol was then added followed by the gradual addition of 226 ml (4.25 mol) of sulfuric acid. The solution was heated to reflux for two hours, and the product was subsequently obtained by distillation from the reaction mixture. The product was washed with an aqueous 2 M sulfuric acid solution and then with an aqueous 10 wt% sodium carbonate solution. The product was then dried over calcium chloride and purified by distillation to give 155 g (72%) of a dense, clear liquid that became increasingly purple over time. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.49 (ddd, J = 5.5, 10.1, 16.2, 4H), 2.24 − 2.13 (m, 1H), 1.15 (d, J = 6.7, 3H).

Synthesis of 2-methyl-1,3-dimercaptopropane

125 g (778 mmol) of potassium ethyl xanthogenate was added to 125 ml of absolute ethanol and purged with argon. A 50% v/v solution of 80 g (371 mmol) of freshly distilled 2-methyl-1,3-dibromopropane in ethanol was added dropwise to the potassium ethyl xanthogenate-ethanol suspension and stirred overnight. The product was obtained using liquid-liquid water-ether extraction. The etheric solution was dried over calcium chloride and the ether evaporated to give 103 g of a crude, light yellow oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.64 (q, J = 7.1, 4H), 3.18 (ddd, J = 6.6, 13.7, 20.8, 4H), 2.31 − 2.21 (m, 1H), 1.42 (t, J = 7.1, 6H), 1.12 (d, J = 6.8, 3H). This crude yellow oil was added dropwise to 200 ml of ethylenediamine in an ice bath and, upon complete addition, was allowed to react no longer than 2 hours. Finally, this mixture was then acidified by cautious addition to a flask of sulfuric acid (500 ml) and ice, yielding a malodorous mixture. The product was obtained using liquid-liquid water-ether extraction. The etheric solution was dried over calcium chloride and the ether evaporated. The residual oil was then vacuum distilled to give 24.0 g (53%) of a slightly yellow oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.67 − 2.54 (m, 4H), 1.86 − 1.75 (m, 1H), 1.26 (t, J = 8.4, 2H), 1.04 (d, J = 6.7, 3H).

Synthesis of 2-methylpropane-1,3-di(thioethyl vinyl ether)

A 50% v/v solution of 24 g (196 mmol) of 2-methyl-1,3-dimercaptopropane and 44 g (413 mmol) of chloroethyl vinyl ether in methanol was prepared and added to a refluxing solution of sodium in methanol under argon protection. The reaction was allowed to react for two hours and then purified using liquid-liquid water-ether solution, dried over calcium chloride, evaporated the ether, and then vacuum distilled to give 40.2 g (78%) of clear oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.46 (dd, J = 6.8, 14.4, 2H), 4.19 (dd, J = 2.2, 14.3, 2H), 4.03 (dd, J = 2.2, 6.8, 2H), 3.85 (t, J = 6.7, 4H), 2.77 (t, J = 6.7, 4H), 2.62 (ddd, J = 6.5, 12.8, 92.4, 4H), 2.00 − 1.86 (m, 1H). 1.09 (d, J = 6.7, 3H).

2-Methylene-propane-1,3-di(thioethyl vinyl ether) (MDTVE — Scheme 3c)

The synthesis of MDTVE has been previously described in the literature31 and is analogous to the procedure described above for MeDTVE, where the commercially available 3-chloro-2-chloromethyl-1-propene replaces the 2-methyl-1,3-dibromopropane in the synthesis above. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.45 (dd, J = 6.8, 14.3, 2H), 5.04 (s, 2H), 4.19 (dd, J = 2.2, 14.3, 2H), 4.03 (dd, J = 2.2, 6.8, 2H), 3.83 (t, J = 6.7, 4H), 3.35 (s, 4H), 2.69 (t, J = 6.7, 4H).

Results and Discussion

The allyl sulfide divinyl ether monomer (MDTVE) and its propyl sulfide divinyl ether analogue (MeDTVE) were photopolymerized with PETMP in a 1:1 vinyl ether:thiol stoichiometric ratio. The two divinyl ether monomers have nearly identical chemical structures and molecular weights, where the central carbon is either a planar sp2 or tetrahedral sp3 configuration in the MDTVE or MeDTVE monomers, respectively (see Scheme 3). The cured polymeric networks exhibit similar thermomechanical properties, as shown in Table 1, indicative of similar network structures. Nevertheless, the material incorporating the allyl sulfide functionality has a larger elastic modulus and a higher Tg, suggesting that the network has a slightly higher crosslink density and/or less flexible backbone.

Table 1.

DMA measurements for a 1:1 vinyl ether:thiol stoichiometric ratio of MDTVE/PETMP or MeDTVE/PETMP, formulated with 0.5 wt% Irgacure 184 and irradiated at 30 mW/cm2 of 365 nm light for 5 minutes.

| Material | Glassy Modulus | Rubbery Modulus | Tg — max(tan δ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| E'(T = −50 °C) | E'(T = 20 °C) | ||

| MeDTVE/PETMP | 1.7 ± 0.2 GPa | 10.8 ± 0.2 MPa | −26.6 ± 0.3 °C |

| MDTVE/PETMP | 1.8 ± 0.1 GPa | 12.2 ± 0.1 MPa | −19 ± 1 °C |

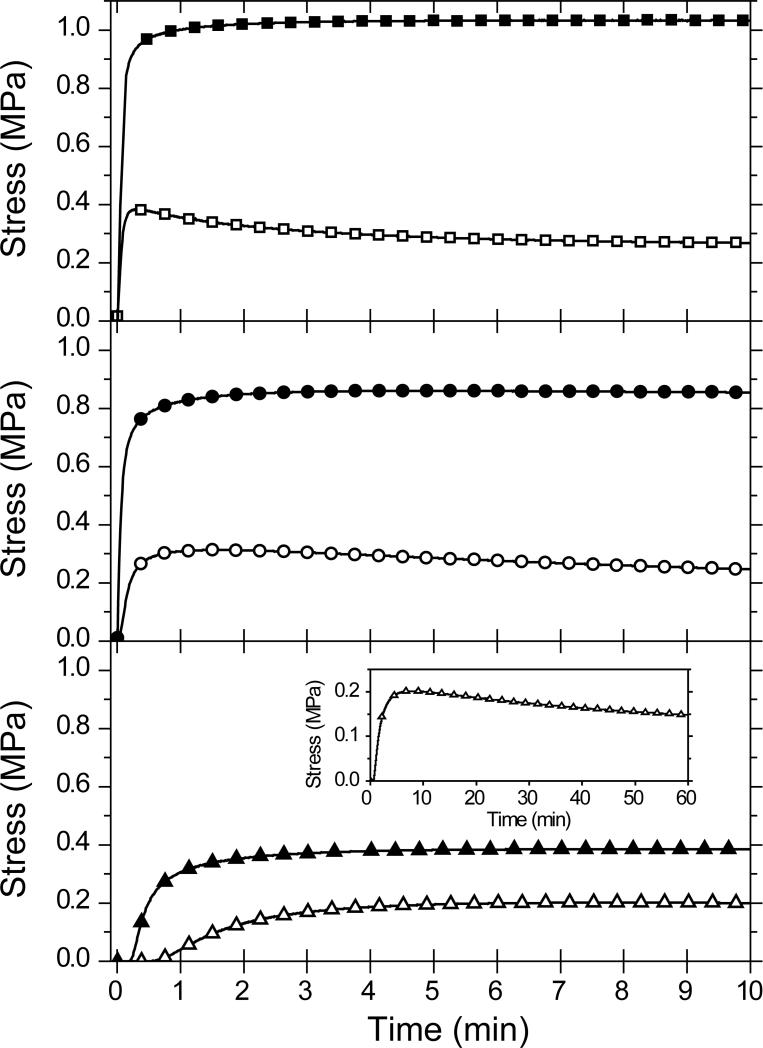

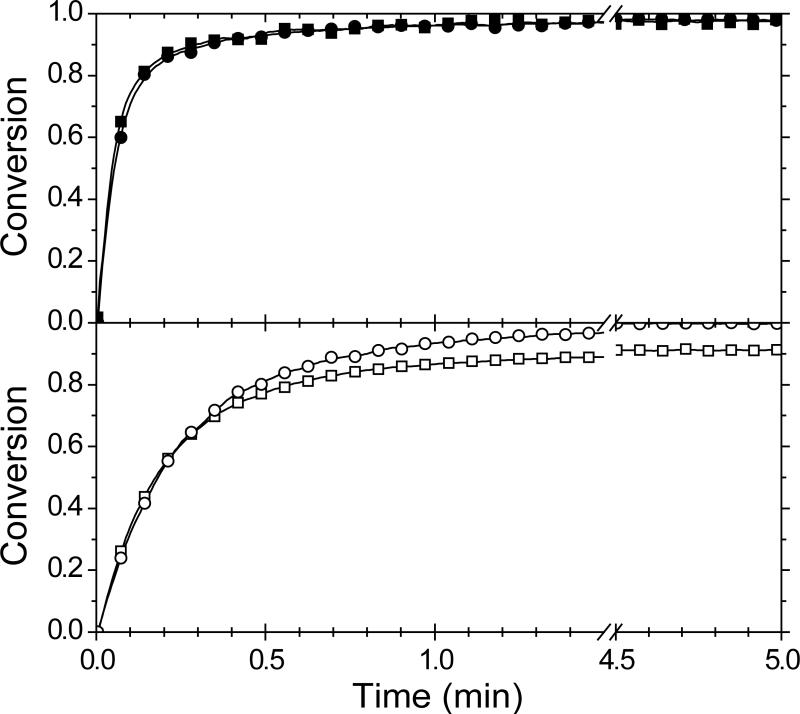

In Figure 1, the shrinkage stress evolution during the photopolymerization of allyl sulfide-based MDTVE/PETMP (open symbols) and propyl sulfide-based MeDTVE/PETMP (filled symbols) thiol-ene resins at three intensities is shown. Despite possessing a slightly higher rubbery modulus and crosslink density (see Table 1), the allyl sulfide-containing material has a dramatically reduced polymerization induced shrinkage stress. The allyl sulfide-containing material exhibits as little as one fourth of the volume-induced shrinkages stress as compared to that of the material containing the propyl sulfide analogue. Moreover, the stress evolution of the allyl sulfide-containing material demonstrates a maximum followed by a gradual, continuous stress relaxation. As illustrated in the three panels of Figure 1, both the stress development rate and the ultimate stress decrease with reduced irradiation intensity. The final stress is the superposition of stored and dissipated stress as the material contracts; this complex viscoelastic behavior is compounded as the material is structurally evolving throughout the polymerization. At sufficiently high polymerization rates, and hence deformation rates (i.e., large polymerization-induced volume shrinkage rates), the material possesses solid-like character, storing stress prior to gelation and yielding a higher accumulated or final stress. Conversely, pre-gelation shrinkage stress is dissipated via flow at low polymerization rates, reducing the final stress.

Figure 1.

Polymerization stress for a 1:1 vinyl ether:thiol stoichiometric ratio of MeDTVE/PETMP (filled symbols) and MDTVE/PETMP (open symbols) irradiated at 10.0 (top panel – squares), 1.0 (middle panel – circles), and 0.1 (bottom panel – triangles) mW/cm2. The inset in the bottom panel is MDTVE/PETMP irradiated at 0.1 mW/cm2 for 60 minutes. All samples were formulated with 0.8 wt% Irgacure 184 and irradiated with 365 nm light. For clarity, not all data points are shown.

The conversion of vinyl ether and thiol for MDTVE/PETMP and MeDTVE/PETMP photopolymerized at the same irradiation intensity is shown in Figure 2. The polymerization rate is slower for the allyl sulfide-containing material as the allyl sulfide functionality and the vinyl ether compete in reactions with the thiyl radical. The allyl sulfide functionality acts as a chain transfer agent, which, upon reaction with a thiyl radical, temporarily sequesters the radical and reduces the polymerization rate. As the polymerization proceeds, the vinyl ether functionality is consumed, thus increasing the likelihood of thiyl radicals reacting with the relatively more abundant allyl sulfide functionality. Interestingly, unlike the thiol functional group (see Figure 2b), the vinyl ether functional group in the MDTVE/PETMP sample does not reach full conversion, suggesting thiol consumption by an alternate mechanism, not indicated in Scheme 1 or Scheme 2.

Figure 2.

Conversion of vinyl ether (square) and thiol (circle) functional groups for a 1:1 vinyl ether:thiol stoichiometric ratio of MeDTVE/PETMP (top panel – filled symbols) and MDTVE/PETMP (bottom panel – open symbols) for thin-film samples irradiated at 10 mW/cm2 of 365 nm light. For clarity, not all data points are shown.

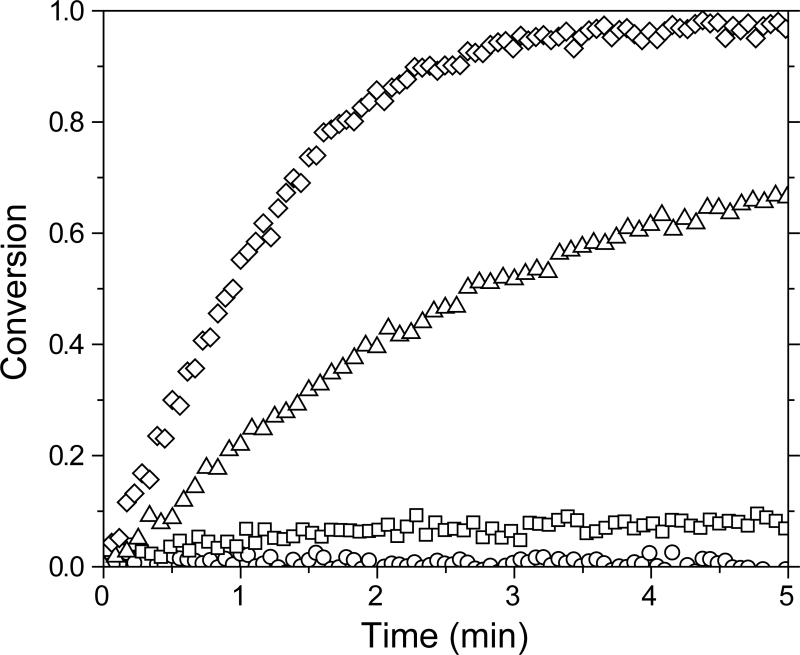

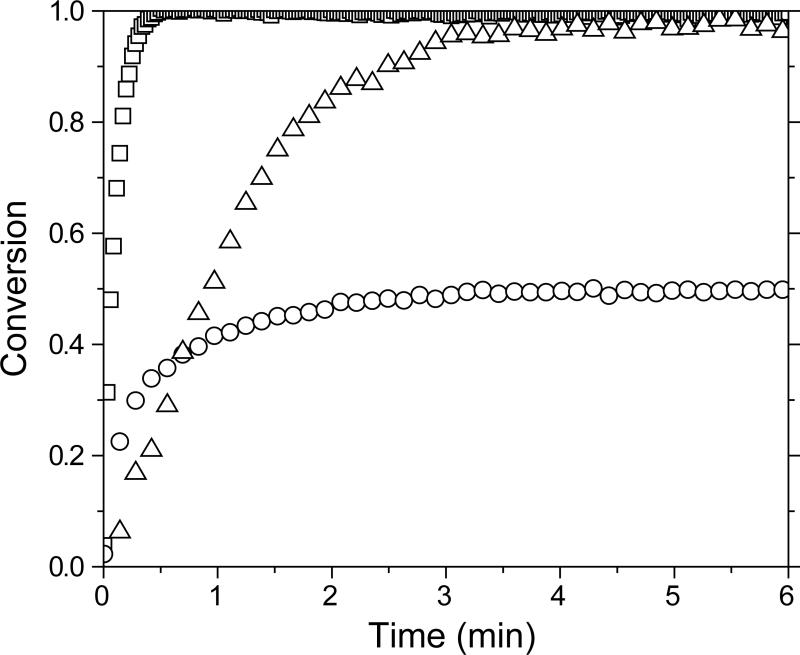

There has been significant debate within the literature on whether intramolecular homolytic substitution of the allyl sulfide (SH2′, i.e., addition-fragmentation) occurs via a concerted or step-wise mechanism.15, 18, 33, 34 For a concerted addition-fragmentation mechanism, the tris(methyl sulfide) radical intermediate (shown in Scheme 1) would not exist, prohibiting potential side reactions and thus conserving the allyl sulfide concentration throughout the polymerization; however, as shown in Figure 3, consumption of allyl sulfide is observed. Indeed, increasing the stoichiometric imbalance in favor of excess thiol results in increased allyl sulfide consumption, inconsistent with a concerted mechanism. Alternatively, the existence of a tris(methyl sulfide) radical intermediate would enable hydrogen abstraction from a thiol group, consistent with a step-wise mechanism. This side reaction is established further by simultaneously monitoring thiol, vinyl ether, and allyl sulfide functional group conversions, revealing that the thiol functional group reacts well after the vinyl functionality is completely consumed, as shown in Figure 4. The excess thiol formulation, containing a 1:3 vinyl ether:thiol stoichiometric mixture of MDTVE to PETMP (1:2 total vinyl:thiol), demonstrates that the allyl sulfide and vinyl ether functional groups approach complete conversion while the thiol functional group approaches 50% conversion; this equates to a 1:1 reaction between thiol and all carbon-carbon double bonds. The presence of this side reaction with thiol is attributable to allyl sulfide addition-fragmentation proceeding via a step-wise mechanism.

Figure 3.

Conversion of allyl sulfide functional groups in a 5:3 (circle), 1:1 (square), 3:5 (triangle), and 1:3 (diamond) vinyl ether:thiol stoichiometric ratio of functional groups for a MDTVE/PETMP polymerization. Thin-film samples were irradiated at 10 mW/cm2 of 365 nm light. For clarity, not all data points are shown.

Figure 4.

Conversion of vinyl ether (square), thiol (circle), and allyl sulfide (triangle) functional groups versus polymerization time for a 1:3 vinyl ether:thiol functional group stoichiometric ratio of MDTVE/PETMP. Thin-film samples were irradiated at 10 mW/cm2 of 365 nm light. For clarity, not all data points are shown.

The simultaneous thiol-ene/allyl sulfide reaction mechanism is proposed in Scheme 4, which incorporates addition-fragmentation into the thiol-ene polymerization mechanism. When the thiyl radical is formed, it undergoes radical-mediated addition to either vinyl ether or allyl sulfide. Upon reaction with allyl sulfide, the tris(methyl sulfide) radical intermediate either fragments, regenerating allyl sulfide and thiyl radical, or abstracts a hydrogen atom from a thiol; this side reaction can be considered as being akin to the thiol-ene polymerization of thiols with allyl sulfides. The thiol-ene polymerization mechanism, regardless of whether it occurs in the vinyl ether or allyl sulfide cycle, results in the loss of a thiol and concomitant creation of a thioether. Thus, networks having similar thiol conversion should have similar crosslink densities, as observed in the DMA (Table 1).

Scheme 4.

Proposed thiol-ene/allyl sulfide reaction mechanism, where the thiyl radical may participate in either the thiol-ene polymerization (left cycle) or allyl sulfide addition-fragmentation (right cycle). Hydrogen abstraction from thiol by the tris(methyl sulfide) radical is indicated by the dashed line.

As described previously, the observed reduction in the vinyl ether consumption rate is attributed to the allyl sulfide functionality temporarily sequestering a fraction of the thiyl radical concentration. A vinyl ether species balance allows the thiyl radical concentration, [S◻], to be expressed in terms of kp, the reaction rate constant for propagation of the thiyl radical through the vinyl ether, and vinyl ether conversion, pVE, as

where [VE] is the vinyl ether concentration. A comparison of the vinyl ether consumption rate in the propyl and allyl sulfide-containing polymerizations reveals the fraction of thiyl radicals sequestered by the allyl sulfide, ϕAS, as

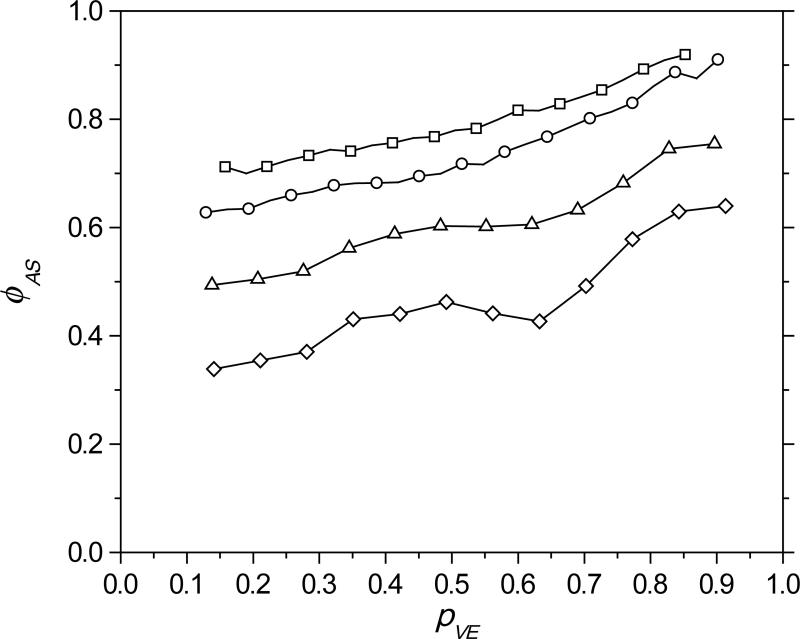

Here, kp is assumed equivalent for MDTVE and MeDTVE as the difference in the functionality incorporated in the backbone of these monomers should have a minimal impact on the terminal vinyl ether functionalities. The instantaneous rates of conversion for allyl and propyl sulfide-based resins were evaluated at equivalent conversions, demonstrating that the allyl sulfide cycle sequesters greater than 70% of the available thiyl radicals shortly after the polymerization begins (squares — Figure 5). The allyl sulfide concentration effect was evaluated by mixing MDTVE and MeDTVE in various ratios, allowing the independent manipulation of the ratio of allyl sulfide to vinyl ether while holding the vinyl ether to thiol ratio constant. The competition between the two vinyl groups to react with the thiyl radical is demonstrated in Figure 5, where the thiyl radical sequestration increases with increasing allyl sulfide concentration, and, as the polymerization proceeds, with decreasing vinyl ether concentration. This behavior is consistent with the proposed reaction mechanism shown in Scheme 4.

Figure 5.

Thiyl radical mole fraction in the allyl sulfide cycle (ϕAS) versus the vinyl ether conversion (pVE) for a 100:0 (square), 75:25 (circle), 50:50 (triangle), and 25:75 (diamond) MDTVE:MeDTVE mixture, formulated with a 1:1 vinyl ether:thiol stoichiometric balance with PETMP.

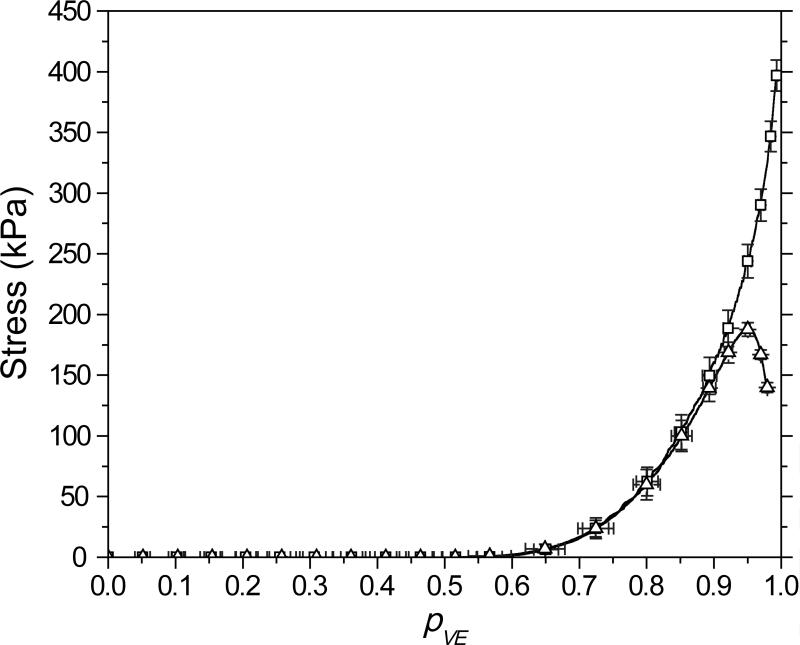

Shrinkage stress as a function of vinyl ether conversion, obtained by coupling simultaneous tensometry and IR spectroscopy, is shown in Figure 6. These photopolymerizations were performed using low light intensity (0.1 mW/cm2 at 365 nm), reducing the polymerization rate and minimizing the possibility of accumulated stress in the pre-gel regime. The gel-point conversion, predicted by the Flory-Stockmayer equation35, 36 as 0.58, closely coincides with the location of the polymerization stress initiation. The post-gelation stress evolution for the allyl sulfide-containing material is markedly different than the propyl sulfide-containing material, attributed to addition-fragmentation chain transfer through the network backbone which dominates the latter stages of the polymerization (see Figure 5). Aside from the significantly reduced final stress, there is an apparent maximum and subsequent relaxation in the stress evolution. The decrease in stress occurring beyond 92% vinyl ether conversion relates to stress relaxation that is occurring after the thiol functionality is completely consumed (see Figure 2). This post-polymerization stress relaxation is characteristic of allyl sulfide addition-fragmentation as observed in previous post-polymerization studies of similar materials.14 In the absence of thiol, the carbon-centered radical generated by the propagation of a thiyl radical through a vinyl ether (see the thiol-ene polymerization cycle, Scheme 4) is incapable of undergoing subsequent propagation or chain transfer events. Thus, in this regime, these carbon-centered radicals exclusively participate in termination events, reducing the proportion of radicals available for addition-fragmentation chain transfer.

Figure 6.

Stress versus vinyl ether conversion (pVE) for a 1:1 vinyl ether:thiol stoichiometric ratio of MeDTVE/PETMP (square) and MDTVE/PETMP (triangle), irradiated at 0.1 mW/cm2 of 365 nm for 60 minutes. For clarity, not all data points are shown.

Conclusion

Allyl sulfide addition-fragmentation in a radical-mediated thiol-ene polymerization reduces polymerization-induced shrinkage stress. Comparison of the photopolymerizations of allyl sulfide and propyl sulfide-containing thiol-ene materials allowed the effect of addition-fragmentation on polymerization rate and shrinkage stress evolution to be isolated. The allyl sulfide functionality acts as an addition-fragmentation chain transfer agent, sequestering radical species and reducing the polymerization rate. Moreover, the addition-fragmentation mechanism provides a pathway for network rearrangement, significantly reducing polymerization stress. It was further shown that addition-fragmentation proceeds via a step-wise mechanism, allowing for an irreversible side reaction whereby the radical intermediate abstracts hydrogen from thiol. This side reaction reduces both the allyl sulfide functional group concentration and the proportion of radicals available for addition-fragmentation chain transfer due to residual, unreacted vinyl ether. Consequently, this side reaction leads to inhibition of the stress relaxation mechanism. Nevertheless, thiyl radical addition to allyl sulfide predominantly results in addition-fragmentation and is an effective pathway to reduce polymerization-induced shrinkage stress. Indeed, addition-fragmentation chain transfer provides a novel avenue for future stress reduction strategies applied to other network forming polymerizations.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health, NIH grant DE10959.

References

- 1.Bowman CN, Kloxin CJ. AIChE J. 2008;54:2775. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobine AF. Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology III. Elsevier; London: 1993. pp. 219–268. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woods JG. Radiation Curing: Science and Technology. Plenum Press; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kloosterboer JG. Adv. Polym. Sci. 1988;84:1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zwiers RJM, Dortant GCM. Appl. Opt. 1985;24:4483. doi: 10.1364/ao.24.004483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovell LG, Berchtold KA, Elliott JE, Lu H, Bowman CN. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2001;12:335. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu H, Carioscia JA, Stansbury JW, Bowman CN. Dent. Mater. 2005;21:1129. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stansbury JW, Bowman CN, Newman SM. Phys. Today. 2008;61:82. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carioscia JA, Lu H, Stanbury JW, Bowman CN. Dent. Mater. 2005:21. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tilbrook DA, Clarke RL, Howle NE, Braden M. Biomaterials. 2000;21:1743. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stansbury JW. J. Dent. Res. 1992;71:1408. doi: 10.1177/00220345920710070901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bucknall CB, Davies P, Partridge IK. Polymer. 1985;26:109. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue T. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1995;20:119. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott TF, Schneider AD, Cook WD, Bowman CN. Science. 2005;308:1615. doi: 10.1126/science.1110505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall DN, Oswald AA, Griesbaum K. J. Org. Chem. 1965;30:3829. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall DN. J. Org. Chem. 1967;32:2082. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Migita T, Kosugi M, Takayama K, Nakagawa Y. Tetrahedron. 1973;29:51. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barton DHR, Crich D. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1986:1613. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meijs GF, Rizzardo E, Thang SH. Macromolecules. 1988;21:3122. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans RA, Moad G, Rizzardo E, Thang SH. Macromolecules. 1994;27:7935. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans RA, Rizzardo E. Macromolecules. 1996;29:6983. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan CR, Magnotta F, Ketley AD. J. Polym. Sci.: Polym. Chem. Ed. 1977;15:627. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoyle CE, Lee TY, Roper T. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 2004;42:5301. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walling C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1945;67:441. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reddy SK, Okay O, Bowman CN. Macromolecules. 2006;39:8832. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cook WD, Chausson S, Chen F, Le Pluart L, Bowman CN, Scott TF. Polym. Int. 2008;57:469. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flory P. Principles of Polymer Chemistry. Corenell University Press; Ithaca, NY: 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu H, Stansbury JW, Dickens SH, Eichmiller FC, Bowman CN. J. Mater. Sci.-Mater. Med. 2004;15:1097. doi: 10.1023/B:JMSM.0000046391.07274.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walba DM, Liberko CA, Korblova E, Farrow M, Furtak TE, Chow BC, Schwartz DK, Freeman AS, Douglas K, Williams SD, Klittnick AF, Clark NA. Liq. Cryst. 2004:31. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamm O, Marvel CS. Org. Synth. 1921;1:1. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott TF, Draughon RB, Bowman CN. Adv. Mater. 2006;18:2128. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evans RA, Rizzardo E. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 2001;39:202. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griesbaum K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1970;9:273. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu YW, Huang HT, Chen Y, Yang JF. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:6061. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flory PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1941;63:3083. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stockmayer WH. J. Chem. Phys. 1943;11:45. [Google Scholar]