The long-term effects of child maltreatment have been postulated by theorists and observed by practitioners, but rarely rigorously studied by researchers. A notable exception is Widom and her colleagues’ program of research. In this issue of the Journal, Colman and Widom (2004) address the important question of the effects of the experience of maltreatment in childhood on intimate relationships in adulthood. In so doing, they integrate and extend two areas of research: (a) the long-term effects of childhood maltreatment and (b) the antecedents of adults’ formation of intimate partnerships. Their study provides an unprecedented, prospective, longitudinal look into the associations between childhood maltreatment and adult cohabitation and marriage. It also raises a number of broader questions about the intergenerational transmission of relationship qualities, especially in terms of the mechanisms underlying intergenerational continuity and discontinuity. It is the understanding of these mechanisms, moreover, that will generate concrete directions for practitioners and policy-makers. With an eye toward expediting such directions, this commentary focuses on a series of questions, raised by Colman and Widom’s findings, about the mediators and moderators of the relations among relationships across generations.

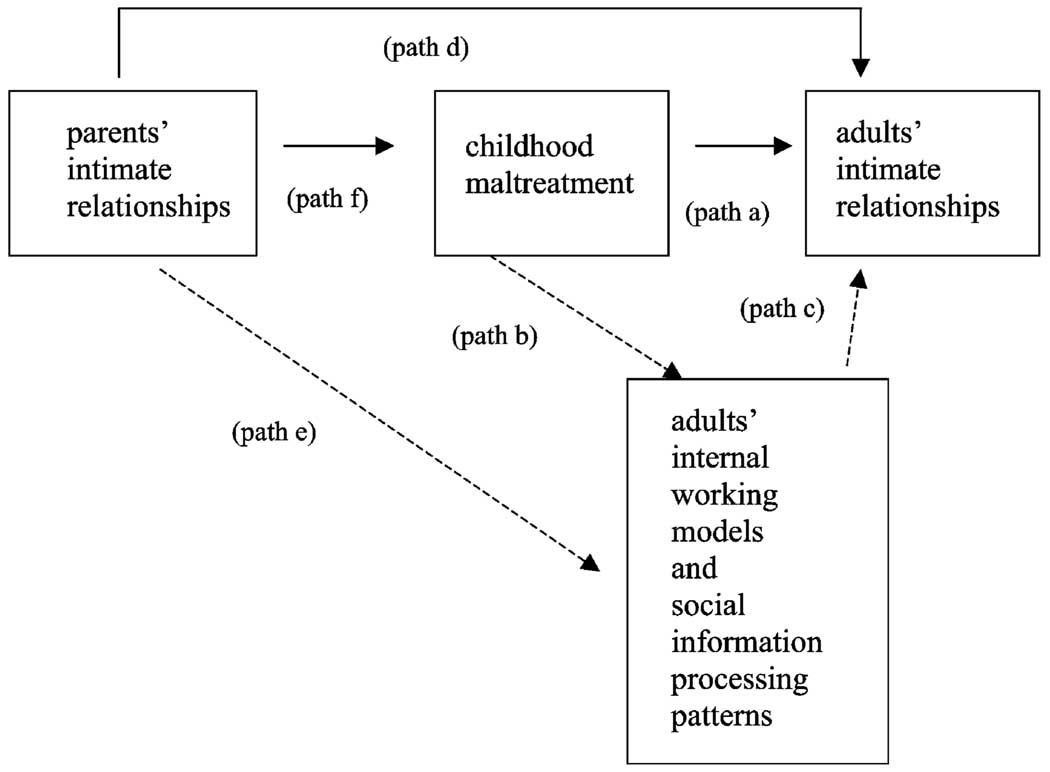

The many strengths of Colman and Widom’s study include its large sample (676 victims of court-substantiated child abuse and 520 matched controls), its long-term longitudinal design (25 years), its examination of different type of childhood maltreatment in both men and women, and its statistical consideration of important selection factors and covariates of childhood maltreatment and marital quality. Colman and Widom (2004) report several take-home findings: (a) childhood victimization is not predictive of a later propensity to marry; (b) childhood victimization does predict problems in the quality of later intimate relationships (e.g., walking out and, for those who do marry, divorce); (c) there are intergenerational continuities in the quality of adults’ intimate relationships; and (d) some effects of a parent’s socioeconomic status and relationship quality on their adult child’s development are mediated by that child’s experience of maltreatment by their parent. These findings raise several questions about the broader relationship context in which these associations may occur, and about the mechanisms that may underlie or disrupt the associations among relationships. Figure 1 depicts one way to conceptualize Colman and Widom’s findings and the questions they raise in a broader relationship context. Three specific sets of questions are considered here.

Figure 1.

A model of relations among relationships across generations. Solid lines represent associations reported by Colman and Widom. Dotted lines represent associations discussed in this commentary.

Question 1: Do adults’ internal working models and social information processing patterns mediate associations between the experience of maltreatment in childhood and intimate relationships in adulthood?

Given the associations between childhood maltreatment and later relationship problems reported by Colman and Widom (see Figure 1, path a), what mechanisms might mediate these associations? We focus here on adults’ working models of attachment and social information processing patterns. Considering these processes together offers a compelling account of how the experience of maltreatment might lead to problems in later intimate relationships. According to attachment theory and research, in the absence of intervening experiences, there are continuities between an individual’s early relationships and later ones, and these continuities occur as a function of the individual’s “internal working models” (Berlin & Cassidy,1999; Bowlby, 1969/1982, 1973, 1980; Main, 1999; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985; see Figure 1, paths b and c). Internal working models are cognitive representations forged in early relationships and carried forward to adulthood to guide the adult’s perspective of caregivers and the self and of how people can and should behave in close relationships (Bowlby, 1969/1982, 1973, 1980). Internal working models are hypothesized to operate by guiding cognitive processes such as attention, memory, and attribution, especially in emotionally-laden situations (Bowlby, 1980; Bretherton & Munholland, 1999; Cassidy, 1994; Main et al., 1985). Internal working models guide the individual’s thinking about the extent to which he or she is worthy of kind treatment and is able to elicit care, the extent to which others are trustworthy and supportive, and the extent to which he or she is likely to receive care when needed. A “secure” adult state of mind with respect to attachment is characterized by trust and expectations of others’ supportiveness. An “insecure” adult state of mind with respect to attachment is characterized by suspicion and expectations that others will not be available when needed (Berlin & Cassidy, 1999; Bowlby, 1979; Bretherton & Munholland, 1999).

An adult’s internal working models of attachment may or may not be concordant with early relationship experiences. Insecure working models are hypothesized to include defensive distortions in the form of minimizing (denying) or over-stating the negative qualities of early relationships. It is also quite possible for working models to change, especially as a function of traumatic or ameliorative attachment experiences. Thus, an adult who was a victim of childhood maltreatment but later received therapeutic help from another attachment figure can “earn” secure working models.

Regardless of whether there is continuity or discontinuity between early and later working models of attachment, current relationships are hypothesized to reflect current—not former—models (Bowlby, 1969/1982, 1979, 1988; Main & Goldwyn, 1998). Thus, associations between adults’ secure internal working models and healthy, supportive intimate relationships are expected, even for “earned secure” adults who had experienced troubled early relationships. Support for these propositions has come from several studies illustrating associations between adults’ working models of attachment and the characteristics of current intimate partnerships (Cohn, Silver, Cowan, Cowan, & Pearson, 1992; Owens et al., 1995; Scharfe & Bartholomew, 1995; Simpson, Rholes, & Phillips, 1996). Moreover, two studies have found that “earned secure” adults with troubled or traumatic histories exhibit equally competent and supportive behaviors as “continuously secure” adults, and more competent and supportive behaviors than insecure adults during observed problem-solving discussions with their partners (Paley, Cox, Burchinal, & Payne, 1999; Roisman, Padron, Sroufe, & Egeland, 2002). Finally, young adults’ working models of attachment have been found to mediate the associations between parent-child dyadic behaviors assessed in early adolescence and behaviors with a romantic partner assessed in early adulthood (Roisman, Madsen, Hennighausen, Sroufe, & Collins, 2001).

Social information processing theory and research (e.g., Dodge, 1986; Dodge & Pettit, 2003) complement and extend the attachment perspective by specifying and operationalizing the cognitive processes purported to be guided by internal working models. According to social information processing theory, social behaviors occur as a function of how an individual selectively attends to specific cues, interprets those cues, accesses from memory behavioral responses to those cues, evaluates the potential consequences of various responses, and decides to enact a particular response. Dodge, Bates, and Pettit (1990) and Dodge, Bates, Pettit, and Valente (1995) have found that children who experience physical maltreatment are likely to develop biased patterns of processing social information, hostile attributions about others’ intentions, a propensity to access retaliatory aggressive responses, even from minor provocations, and a tendency to evaluate aggressive responses as morally acceptable and likely to lead to positive outcomes. These social information processing patterns, moreover, predict aggressive behavior and partially mediate the effect of physical maltreatment on later aggressive behavior (Dodge et al., 1990).

One next step toward better understanding the processes that mediate the associations between childhood maltreatment and adults’ intimate relationships examined by Colman and Widom would be to study how the experience of childhood maltreatment predicts adults’ working models of attachment, including distorted memories of childhood experiences, and patterns of processing social information. This empirical inquiry would fill in dotted paths b and c in Figure 1.

Question 2: What accounts for intergenerational continuity in relationship qualities?

In Figure 1, path d depicts the intergenerational transmission of characteristics of one’s parents’ intimate relationships to characteristics of one’s own adult relationships. The most well-known example of this intergenerational transmission comes from studies of divorce. Amato (1996) has found that children whose parents have been divorced are at risk of growing up to experience conflict in their own romantic relationships and to experience divorce themselves. Much less clear is an understanding of the mechanisms that may account for this continuity, although internal working models have been postulated to play a role (Berlin & Cassidy, 1999; Hazan & Shaver, 1987) (see Figure 1, path e). McLoyd (1990) has proposed that characteristics of family background (particularly socioeconomic status but also marital quality) may exert their effects on distal child outcomes through their more proximal impact on parenting. Other plausible hypotheses are that continuity is accounted for by passive observational learning by the child of her or his parents’ relationship, or by a common third variable, such as shared genetic characteristics.

The findings from Colman and Widom provide support for the perspective that parent-child interactions may mediate intergenerational continuity in relationship characteristics. That is, they find significant effects of parents’ marital status on adult children’s likelihood of cohabitation, walking out of a romantic relationship, and divorce. These effects are mediated through their impact on the abuse and neglect of their child, which, in turn, account for the effects on adverse adult relationship outcomes (see Figure 1, paths a and f). These findings provide important information regarding not only the contributions that parent-child interactions can make to intergenerational continuity in the qualities of adults’ intimate relationships, but also the context in which abuse and neglect can occur (that is, in a context of marital discord).

Question 3: What accounts for intergenerational discontinuity in relationship qualities?

In Colman and Widom’s study and in others, problematic early relationships (including child maltreatment) and parents’ marital discord are not inevitably linked to problematic adult partnerships. In addition to the defensive distortions and attributional biases discussed earlier, what moderating processes might account for these intergenerational discontinuities? Important factors that are relatively simple to measure are the ages and duration of childhood victimization, as several recent studies have highlighted the particularly injurious nature of earlier and longer-lasting victimization (e.g., Keiley, Howe, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 2001; Trickett, Reiffman, Horowitz, & Putnam, 1997; US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, 2002). In addition, as already discussed, ameliorative attachments that could develop with non-abusive adults or psychotherapists may also break intergenerational cycles of dysfunctional relationships (Bowlby, 1988; Egeland, Jacobvitz, & Sroufe, 1988). These deserve further scrutiny. Last, work by Quinton, Rutter, and Liddle (1984) and Belsky, Youngblade, and Pensky (1990) has suggested that a woman’s physical attractiveness may contribute to discontinuities between problematic childhood relationships and adult marital quality, perhaps by giving her a wider variety of partners to choose from, and, thus, an increased opportunity to find a supportive mate.

Conclusions

Colman and Widom’s important work on the associations between childhood maltreatment and adults’ intimate relationships led to the consideration in this commentary of three specific questions pertaining to the mechanisms underlying intergenerational continuity and discontinuity in relationship qualities. Better understanding of these mechanisms is, we believe, key to improving practices and policies for vulnerable children, especially those who have been victims of child abuse or neglect. For example, to the extent that adults’ internal working models and social information processing patterns account for the links between the experience of childhood maltreatment and later marital problems, therapies that help people gain insight into their working models and consider alternative attributions and behaviors are warranted. To the extent that marital discord sets the stage for abusive or neglectful parenting practices, policies that integrate (rather than separate) resources for promoting positive marriages with resources for promoting child welfare are required. The measure of our success in these research and practical efforts will be fewer abused or neglected children to study or to treat.

References

- Amato P. Explaining the intergenerational transmission of divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996;56:21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Youngblade L, Pensky E. Childrearing history, marital quality and maternal affect: Intergenerational transmission in a low-risk sample. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;1:291–304. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Cassidy J. Relations among relationships: Contributions from attachment theory and research. In: Cassidy J, Shaver P, editors. Handbook of attachment. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 688–712. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 19691982. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss, Vol. 2: Separation. New York: Basic Books; 19691982. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. The making and breaking of affectional bonds. New York: Methuen; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss, Vol. 3: Loss. New York: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A secure base. New York: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Munholland KA. Internal working models in attachment relationships: A construct revisited. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. Emotion regulation: influences of attachment relationships. In: Fox N, editor. Emotion regulation: Biological and biological considerations. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development; 1994. pp. 228–249. 59(2–3, Serial No. 240) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn DA, Silver DH, Cowan CP, Cowan PA, Pearson J. Working models of childhood attachment and couple relationships. Journal of Family Issues. 1992;13:432–449. [Google Scholar]

- Colman RA, Widom CS. Childhood abuse and neglect and adult intimate relationships: A prospective study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:1133–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA. A social information processing model of social competence in children. In: Perlmutter M, editor. Minnesota symposium in child psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1986. pp. 77–125. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science. 1990;250:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.2270481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Valente E. Social information-processing patterns partially mediate the effect of early physical abuse on later conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:632–643. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.4.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS. A biophychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(2):349–371. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeland B, Jacobvitz D, Sroufe LA. Breaking the cycle of abuse. Child Development. 1988;59:1080–1088. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:511–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiley MK, Howe TR, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. The timing of child physical maltreatment: A cross-domain growth analysis of impact on adolescent externalizing and internalizing problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:891–912. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main M. Epilogue. Attachment theory: Eighteen points with suggestions for future studies. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 845–887. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Goldwyn R. Adult attachment scoring and classification system. University of California at Berkeley; 1998. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. In: Bretherton I, Waters E, editors. Growing points of attachment theory and research. Monograph of the Society for Research in Child Development; 1985. pp. 66–104. 50(1–2, Serial No. 209) [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens G, Crowell JA, Pan H, Treboux D, O’Connor E, Waters E. The prototype hypothesis and the origins of attachment working models: Adult relationships with parents and romantic partners. In: Waters E, Vaughn BE, Posada G, Kondo-Ikemura K, editors. Caregiving, cultural, and cognitive perspectives on secure-base behavior and working models: New growing points of attachment theory and research. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development; 1995. pp. 216–233. 60(2–3, Serial No. 244) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paley B, Cox MJ, Burchinal MR, Payne CC. Attachment and marital functioning: comparison of spouses with continuous-secure, earned-secure, dismissing, and preoccupied attachment stances. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:580–597. [Google Scholar]

- Quinton D, Rutter M, Liddle C. Institutional rearing, parenting difficulties, andmarital support. Psychological Medicine. 1984;14:107–124. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700003111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Madsen SD, Hennighausen KH, Sroufe LA, Collins WA. The coherence of dyadic behavior across parent-child and romantic relationships as mediated by the internalized representation of experience. Attachment and Human Development. 2001;1:156–172. doi: 10.1080/14616730126483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GL, Padron E, Sroufe LA, Egeland B. Earned-secure attachment status in retrospect and prospect. Child Development. 2002;73:1204–1219. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfe E, Bartholomew K. Accommodation and attachment representations in young couples. Journal of Personal and Social Relationships. 1995;12:389–401. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Phillips D. Conflict in close relationships: An attachment perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:899–914. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.5.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, Reiffman A, Horowitz LA, Putnam FW. Characteristics of sexual abuse trauma and the prediction of developmental outcomes. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. The Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology, Vol. VIII: The effects of trauma and on the developmental process. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1997. pp. 289–314. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth, and Families. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; Child maltreatment 2000. 2002