Abstract

Conduct disorder (CD) is a disorder of childhood and adolescence defined by rule breaking, aggressive and destructive behaviors. For some individuals, CD signals the beginning of a lifelong persistent pattern of antisocial behavior (antisocial personality disorder (ASPD)), while for other people these behaviors either desist or persist at a sub-clinical level. It has generally been accepted that about 40% of individuals with CD persist. This study examined the rate of persistence of DSM-IV CD into ASPD and the utility of individual DSM-IV CD symptom criteria for predicting this progression. We used the nationally representative sample from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Approximately 75% of those with CD also met criteria for ASPD. Individual CD criteria differentially predicted severity and persistence of antisocial behavior with victim-oriented, aggressive behaviors generally being more predictive of persistence. Contrary to previous estimates, progression from CD to ASPD was the norm and not the exception in this sample. Relationships between individual DSM-IV CD symptom criteria and persistent antisocial outcomes are discussed. These findings may be relevant to the development of DSM-V.

1. Introduction

Many antisocial adolescents continue to be antisocial in adulthood while others do not (1). Currently we know little about predicting clinical course for those who present with antisocial behavior during adolescence. Contributing to this uncertainty, antisocial behavior (ASB) has a heterogeneous etiology (2). Given that persons with persistent antisocial behavior (ASB) account for a disproportionately large percentage of crimes (3), identifying methods of discerning adolescents with transient versus persistent ASB is of practical importance.

Research on persistent ASB suggests that an earlier age of onset may predict persistence (4), as well as pervasiveness (5). Other studies disagree reporting that earlier age of onset has no predictive validity (6), and that antisocial adults both with and without prior Conduct Disorder (CD) diagnoses have similar levels of demographic and psychopathological risk factors (7, 8). Also, childhood comorbid hyperactivity and conduct disorder may predict poor adult outcomes (9, 10). Finally, higher levels of psychopathic traits in adolescence predict violent recidivism (11). However, the appropriateness and validity of psychopathy in adolescents is a contentious issue and its application to adolescents is a relatively new area (12).

Longitudinal research on males from birth to 26 years suggests two main groups of deviant youth (13–16). Life-course persistent (LCP) individuals have ASB beginning as early as age 3 and continuing into adulthood. An adolescence-limited (AL) group consists of people whose antisocial acts are largely committed during the period of adolescence. Although there are a variety of between-group differences, during adolescence they are currently indistinguishable (15).

LCP individuals are more troublesome for society, committing more violent offenses, and exhibiting more drug problems, high risk behaviors, reliance on social benefits, and psychopathology (16). There are distinct differences between the transient versus persistent offenders (13). The LCP group members are more likely to have subtle neuropsychological deficits present early in life, and are more likely to display victim oriented violent offenses (13). Unlike their LCP peers, AL members are less likely to display pervasive ASB and are less prone to violent acts (13, 16). The theory suggests that AL adolescents commit antisocial acts with peers and engage primarily in behaviors that symbolize adult privilege and autonomy from parents (15). If this theory is correct then antisocial behaviors in adolescence should differentially predict persistence to adult ASB.

1.1. Aims of the study

In the present study, we examine the prevalence of DSM-IV CD criteria and their utility as discriminators between those who endorse symptom criteria but do not qualify for a diagnosis (sub-clinical), and those who have a CD diagnosis (clinical). We also examine the utility of the individual criteria for predicting of those who qualify for a diagnosis of CD, who will continue on to a diagnosis of ASPD (i.e., transient versus persistent ASB). The main objective is to identify ASBs displayed during adolescence that may indicate severity and persistence into adulthood. Several previous studies of CD have looked at individual diagnostic criteria, however, none of them have done so with goals similar to those of the present study (2, 17–20). To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the utility of individual DSM-IV CD symptom criteria in predicting persistence and diagnosis of ASPD in adulthood.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

We examined the public dataset from Wave 1 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC, http://niaaa.census.gov/) a nationally representative sample of 43,093 respondents interviewed via face-to-face interviews (for details see (21)). The target of the survey was the civilian non-institutionalized population aged 18 years and over residing in the United States including the District of Columbia, Alaska and Hawaii. The research protocol received full ethical review and human subjects approval from the U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Office or Management and Budget.

Conduct disorder (CD) and antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) diagnoses used in the present study were provided in the public dataset, and based on retrospectively reported criteria from the NIAAA Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV) (22). Consistent with DSM-IV standards, personality disorder diagnoses required that at least one endorsed symptom caused social and/or occupational dysfunction. The antisocial personality module of the AUDADIS-IV has good reliability and validity (23). As the algorithms used to create diagnoses in the NESARC are not publicly available, we selected AUDADIS items (Appendix 1) to operationalize DSM-IV’s CD symptom criteria. We were unable to identify an interview question that corresponded to the CD symptom criterion “Break and Enter” in the AUDADIS-IV interview, therefore this criterion is not included in our analyses. We used the items shown in Appendix 1 to represent individual criteria, but we used the CD and ASPD diagnoses provided in the public dataset so that our research could be compared with other studies of this sample. In the public dataset, 1522 subjects are missing responses to some (N = 514) or all (N = 1008) of the CD diagnostic criteria we identified in Appendix 1; we excluded these cases from our analyses.

Appendix 1.

UDADIS-IV interview questions used to represent Conduct Disorder diagnostic criteria

| Conduct Disorder Criterion | AUDADIS-IV question In your entire life, did you EVER… | |

|---|---|---|

| CD 1 | Bully | Have a time when you bullied or pushed people around or tried to make them afraid of you? OR: Harass, threaten or blackmail someone? |

| CD2 | Fights | Get into a lot of fights that you started? |

| CD3 | Weapons | Use a weapon, like a stick, knife, or gun in a fight? |

| CD4 | Cruel to People | Hit someone so hard that you injured them or they had to see a doctor? OR: Physically hurt another person in any other way on purpose? |

| CD5 | Cruel to Animals | Hurt or be cruel to an animal or pet on purpose? |

| CD6 | Steal with Confrontation | Rob or mug someone, or snatch a purse? |

| CD7 | Force Sex | Force someone to have sex with you against their will? |

| CD8 | Fire Setting | Start a fire on purpose to destroy someone else’s poroperty or just to see it burn? |

| CD9 | Vandalism | Destroy, break, or vandalize someone else’s property – like their car, home, or other personal belonging’s? |

| CD10 | Break and Enter | Not available in public dataset |

| CD11 | Lies | Have a time in your life when you lied a lot not counting any times you lied to keep from being hurt? OR: Use a false or made-up name or alias? OR: Scam or con someone for money, to avoid responsibility or just for fun? OR: Forge someone else’s signature – like on a legal document or on a check? |

| CD12 | Steal without Confrontation | Steal anything from someone or someplace when no one was around? OR: Shoplift? |

| CD13 | Out Late | Stay out late at night even though your parents told you to stay home? (before age 13) |

| CD14 | Runaway | Run away from home overnight at least twice when you were living at home or urn away and stay away for a longer time? |

| CD15 | Truancy | Often cut class, not go to class or go to school and then leave without permission? (before the age of 13 |

2.2. Subject Grouping

We estimated prevalence of each DSM-IV CD criterion in the whole sample (minus the above exclusions). ASPD is only diagnosed in persons who also meet criteria for CD, but not all persons with CD develop ASPD. Thus, we classified respondents who had endorsed at least one CD criterion into three groups based on their antisocial status. Respondents with no diagnosis of CD or ASPD but who had endorsed at least one CD criterion were classified as Sub-Clinical (SC). Respondents who warranted a diagnosis of CD but not ASPD were classified as CD only (CD); they had “transient” ASB. The remaining respondents were diagnosed with both CD and ASPD (ASPD); they had “persistent” ASB.

2.3. Analyses

The prevalence of each criterion was examined separately in each sex for the entire NESARC sample (minus exclusions). In addition, we calculated the prevalence of each criterion according to antisocial status (SC, CD, ASPD), and age of onset within these groups. Criterion prevalence patterns provide graphical comparisons of prevalence rates in these sub-groups. Diagrams were obtained by plotting the relative prevalence of the criterion in each antisocial status group compared to the prevalence in the ASPD group. Three points plotted for each criterion are obtained by:

These plots provide a comparison of criterion patterns that is not complicated by large prevalence differences between criteria. Although some criteria may appear to be extremely useful predictors based on these plots, it is important to note that infrequently endorsed criteria are of limited utility because they provide information on very few individuals.

We aimed to identify criteria that significantly predict sub-clinical versus clinical ASB, and transient versus persistent ASB. We conducted logistic regressions with the CD symptom criteria as independent variables. Models with a single criterion as a predictor of antisocial status as well as analyses with all CD criteria in a single model were tested. The first approach estimates the informativeness of each individual criterion; the second identifies criteria that are redundant or less useful in the context of the entire set. These analyses provide statistical tests of the criterion pattern plots. The utility of our results was explored by a post-hoc investigation of endorsement patterns. Analyses were conducted in SUDAAN (24), a program designed to be applied to data using complex survey sampling, it adjusts for variances using the Taylor series linearization method while using the NESARC sampling weights.

3. Results

Of the 43,093 respondents to the NESARC, we excluded 1,522 due to missing CD diagnostic information. Of the remaining 41,571 respondents, 11,683 (28%) reported at least one of the DSM-IV CD criteria. In males, 1186 (6.7%) respondents qualified for a diagnosis of CD, and 79% of those with CD (932) also qualified for a diagnosis of ASPD. Similarly, in females, 627 (2.6%) respondents qualified for a diagnosis of CD, and 75% of those (n=471) also qualified for a diagnosis of ASPD.

Table 1 shows the overall prevalence of each CD symptom criterion, presented separately by sex. In addition, the prevalence of each symptom criterion by antisocial status is provided for the sub-sample of respondents who endorsed at least 1 CD criterion. Finally, of those who endorsed each symptom criterion, the percentage of respondents reporting onset before the age of 15 years (per DSM-IV before 13 for “Truancy” and “Runaway”) is presented by antisocial status.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Conduct Disorder criteria in NESARC data

| MALES |

FEMALES |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Criterion Prevalence (%) | Criterion Prevalence by Antisocial Status (%) | % of those endorsing the symptom reporting age of onset before 15 years | Overall Criterion Prevalence (%) | Criterion Prevalence by Antisocial Status (%) | % of those endorsing the symptom reporting age of onset before 15 years | ||||||||||

| DSM | Criterion | N=17,767 | SC N=5211 | CD N=254 | ASPD N=932 | SC N=5211 | CD N=254 | ASPD N=932 | N=23,804 | SC N =4659 | CD N=156 | ASPD N=471 | SC N=4659 | CD N=156 | ASPD N=471 |

| CD1 | Bully | 9.4 | 18.7 | 38.4 | 57.0 | 47.5 | 88.9 | 82.5 | 4.9 | 17.3 | 50.3 | 59.4 | 49.7 | 95.3 | 77.6 |

| CD2 | Fights | 3.9 | 6.0 | 16.4 | 33.0 | 37.0 | 89.2 | 78.9 | 1.8 | 5.2 | 25.5 | 31.3 | 29.1 | 100.0 | 80.7 |

| CD3 | Weapons | 3.8 | 7.8 | 5.2 | 25.2 | 19.9 | 95.4 | 60.3 | 1.6 | 5.6 | 4.4 | 25.5 | 14.5 | 93.2 | 44.7 |

| CD4 | Cruel to People | 14.4 | 34.0 | 35.3 | 65.6 | 22.9 | 89.3 | 59.9 | 4.3 | 15.9 | 27.4 | 53.3 | 27.3 | 92.4 | 61.3 |

| CD5 | Cruel to Animals | 3.2 | 5.5 | 18.0 | 22.0 | 58.5 | 97.6 | 84.8 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 6.2 | 4.6 | 48.2 | 91.6 | 76.0 |

| CD6 | Steal w/Confront | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 4.6 | 19.3 | NA | 37.7 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 14.3 | NA | 46.3 |

| CD7 | Forced Sex | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 18.8 | NA | 21.8 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 21.1 | 99.0 | 8.0 |

| CD8 | Fire Setting | 1.9 | 2.4 | 11.3 | 18.2 | 63.2 | 95.8 | 83.4 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 5.7 | 9.2 | 67.8 | 99.8 | 64.4 |

| CD9 | Vandalism | 6.0 | 9.0 | 39.6 | 48.2 | 16.0 | 93.4 | 76.3 | 1.7 | 4.6 | 17.8 | 33.1 | 7.9 | 94.2 | 60.5 |

| CD10 | Break and Enter& | ||||||||||||||

| CD11 | Lies | 9.6 | 20.2 | 23.0 | 57.3 | 28.8 | 90.8 | 70.1 | 7.1 | 27.9 | 38.2 | 72.2 | 31.9 | 91.1 | 80.8 |

| CD12 | Steal w/o Confront | 18.7 | 43.5 | 68.6 | 81.7 | 72.8 | 99.8 | 93.7 | 11.2 | 47.4 | 59.2 | 78.6 | 74.3 | 97.2 | 90.9 |

| CD13 | Out Late* | 4.0 | 6.5 | 23.2 | 30.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 1.2 | 3.2 | 22.9 | 23.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| CD14 | Runaway | 5.1 | 10.3 | 18.6 | 31.9 | 39.0 | 89.1 | 74.2 | 5.1 | 19.0 | 37.0 | 58.7 | 34.0 | 94.6 | 82.8 |

| CD15 | Truancy* | 4.8 | 9.4 | 28.0 | 27.5 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 2.1 | 7.0 | 24.9 | 27.8 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

SC = sub-clinical (1 or more CD criteria endorsed, no diagnosis); CD = Conduct Disorder diagnosis, no ASPD (transient); ASPD = CD and ASPD diagnoses (persistent)

There was not an interview item in the publicly available NESARC data that corresponded to this particular DSM criterion

age of onset was required before age 13 for these two criteria based on DSM-IV standards

Prevalence values estimated using SUDAAN

For each symptom criterion with the exception of “Runaway” the prevalence is higher in males than females. In males, 5.3% of the sample was ASPD (persistent), 1.4% was CD-only (transient), 29.3% was SC (subclinical), and the remaining 64.0% of males did not report ASB. In females 2.0%, 0.7%, 19.6%, and 77.7% were classified as ASPD, CD-only, SC, and not reporting ASB, respectively. The prevalence of the CD symptom criteria in males ranged from 0.2% (“Forced Sex”) to 18.7% (“Steal without Confrontation”), and in females from 0.1% (“Forced Sex” and “Steal with Confrontation”) to 11.2% (“Steal without Confrontation”).

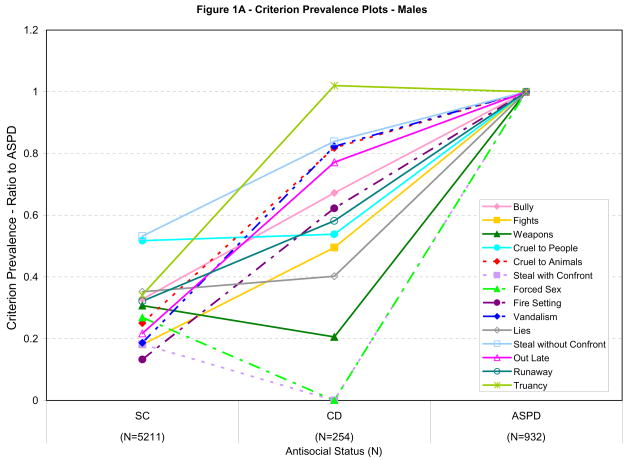

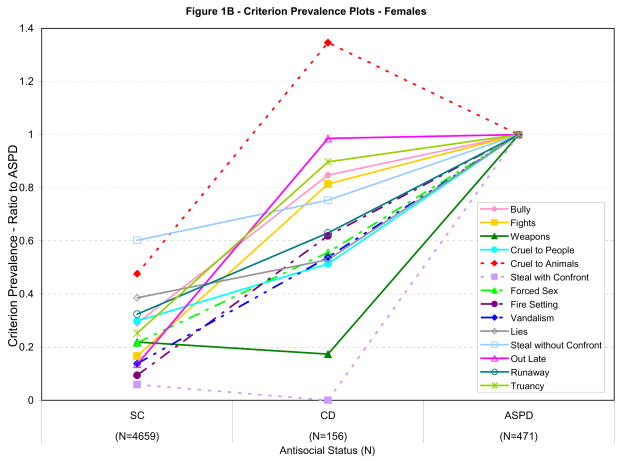

The criterion prevalence patterns for each item by antisocial status are shown graphically in Figures 1A (males) and 1B (females). These figures display criterion prevalence trends according to antisocial status. A criterion for which the prevalence ratio is stable across sub-clinical (SC) and CD-only (CD) groups, but increases in the ASPD group (e.g., lies) discriminates transient and persistent ASB. In contrast, a criterion for which the prevalence ratio increases from SC to CD, but is stable across CD and ASPD (e.g., truancy), poorly discriminates transient from persistent persons. The prevalence ratio lines provide a simple comparison of criterion functioning across antisocial status. These figures suggest that in each sex, several criteria better predict persistent ASB. Consistent across sex, “Steal with Confrontation,” “Weapons,” and “Lies” appear to discriminate CD and ASPD groups. A similar pattern is observed for the criterion “Forced Sex” in males. Figures 1A and 1B also indicate some criteria are not useful discriminators of transient and persistent ASB (e.g., “Truancy,” “Out Late,” and “Cruelty to Animals”). These criteria are endorsed with very similar, or for “Truancy” in males and “Cruelty to Animals” in females, greater frequency by the CD group compared with the ASPD group.

Figure 1.

Figures 1A and 1B

Criterion prevalence plots (1A – males, 1B – females): Data points for each group calculated as ratio of criterion prevalence in group noted in column versus the ASPD group (e.g., prevalence SC/prevalence ASPD, prevalence CD/prevalence ASPD, prevalence ASPD/prevalence ASPD). SC = sub-clinical (1 or more CD criteria endorsed, no diagnosis); CD = Conduct Disorder diagnosis, no ASPD; ASPD = CD and ASPD diagnoses. Prevalence estimates were obtained using SUDAAN.

Table 2 presents the odds ratios (and 95% confidence intervals) for the logistic regression analyses. Odds ratios are presented for single criterion and full models in each sex that examine a) whether the criterion significantly predicts clinical behavior versus sub-clinical behavior, and b) whether the criterion significantly predicts persistent versus transient behavior.

Table 2.

Odds ratios for Conduct Disorder criteria

| Males |

Females |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical vs. Subclinical (C.I)a | Persistent vs. Transient (C.I.)b | Clinical vs. Subclinical (C.I)a | Persistent vs. Transient (C.I.)b | |||||

| Criterion | Single item in each model | All items in one model | Single item in each model | All items in one model | Single item in each model | All items in one model | Single item in each model | All items in one model |

| Bully | 4.9 (4.12 – 5.86) | 3.9 (3.07 – 5.04) | 2.1 (1.50 – 2.92) | 1.9 (1.25 – 3.01) | 6.4 (5.16 – 7.84) | 6.7 (4.89 – 9.29) | 1.5 (1.00 – 2.22) | 1.6 (0.92 – 2.82) |

| Fights | 6.6 (5.30 – 8.14) | 4.0 (2.77 – 5.84) | 2.5 (1.56 – 3.95) | 2.0 (1.00 – 3.94) | 7.7 (5.89 – 10.09) | 3.3 (2.03 – 5.32) | 1.4 (0.83 – 2.31) | 0.9 (0.44 – 1.96) |

| Weapons | 3.2 (2.56 – 3.87) | 1.0 (0.61 – 1.56) | 5.9 (3.34 –10.46) | 4.2 (2.44 – 7.05) | 4.2 (3.27 – 5.52) | 0.9 (0.50 – 1.60) | 7.4 (2.84 – 19.26) | 5.5 (1.89 – 15.95) |

| Cruel to People | 2.8 (2.37 – 3.34) | 2.1 (1.56 – 2.72) | 3.4 (2.40 – 4.89) | 3.0 (2.01 – 4.49) | 4.6 (3.70 – 5.77) | 2.7 (1.83 – 3.89) | 3.1 (1.87 – 5.00) | 3.0 (1.69 – 5.44) |

| Cruel to Animals | 4.6 (3.68 – 5.76) | 5.0 (3.36 – 7.52) | 1.3 (0.83 – 2.13) | 1.5 (0.89 – 2.53) | 2.4 (1.51 – 3.67) | 3.1 (1.28 – 7.35) | 0.7 (0.26 – 2.07) | 0.8 (0.25 – 2.27) |

| Steal w/Confront* | 4.4 (2.66 – 7.43) | 13.1 (5.56 – 31.00) | 1.5 (0.07 – 28.29) | |||||

| Forced Sex* | 3.0 (1.22 – 7.23) | 4.1 (1.70 – 9.91) | 2.6 (0.61 – 10.71) | 1.8 (0.39 – 8.61) | 1.3 (0.33 – 4.83) | |||

| Fire Setting | 8.1 (5.96 – 11.09) | 4.9 (2.87 – 8.42) | 1.7 (1.06 – 2.84) | 1.6 (0.85 – 2.84) | 10.4 (6.48 – 16.70) | 13.1 (5.49 – 31.46) | 1.7 (0.62 – 4.57) | 2.1 (0.72 – 5.93) |

| Vandalism | 8.7 (7.37 – 10.39) | 6.1 (4.60 – 8.13) | 1.4 (0.98 – 2.01) | 1.8 (1.13 – 2.71) | 8.6 (6.43 – 11.45) | 3.8 (2.10 – 6.86) | 2.3 (1.22 – 4.30) | 2.5 (1.15 – 5.30) |

| Break and Enter& | ||||||||

| Lies | 4.0 (3.32 – 4.71) | 2.0 (1.58 – 2.58) | 4.5 (3.01 – 6.68) | 3.9 (2.49 – 5.99) | 4.5 (3.64 – 5.57) | 3.2 (2.29 – 4.58) | 4.0 (2.55 – 6.32) | 4.0 (2.39 – 6.55) |

| Steal w/o Confront | 4.9 (4.09 – 5.78) | 6.2 (4.78 – 8.11) | 2.1 (1.48 – 2.99) | 2.7 (1.70 – 4.26) | 3.1 (2.46 – 3.92) | 4.5 (3.24 – 6.18) | 2.4 (1.46 – 3.95) | 2.8 (1.53 – 5.25) |

| Out Late | 5.7 (4.67 – 7.05) | 10.8 (8.09 – 14.49) | 1.4 (0.98 – 2.11) | 1.9 (1.03 – 3.38) | 9.2 (6.69 – 12.72) | 12.7 (7.96 – 20.37) | 1.1 (0.64 – 1.73) | 1.3 (0.67 – 2.34) |

| Runaway | 3.6 (2.99 – 4.30) | 3.1 (2.14 – 4.35) | 2.0 (1.38 – 2.93) | 2.5 (1.52 – 4.14) | 4.8 (3.90 – 5.97) | 4.0 (2.76 – 5.74) | 2.5 (1.55 – 4.02) | 2.9 (1.68 – 5.09) |

| Truancy | 3.7 (3.04 – 4.44) | 7.6 (5.71 – 10.05) | 1.0 (0.66 – 1.58) | 1.0 (0.57 – 1.73) | 4.9 (3.83 – 6.29) | 8.1 (5.79 – 11.39) | 1.2 (0.74 – 1.98) | 1.2 (0.61 – 2.28) |

Odds ratios represent the amount of increased risk for being classed clinical over sub-clinical if the criterion is endorsed.

Odds ratios represent the amount of increased risk for being classed persistent over transient if the criterion is endorsed.

For some criterion endorsement was not sufficient to calculate odds ratios

There was not an interview item in the publicly available NESARC data that corresponded to this particular DSM criterion

Odds ratios were estimated using SUDAAN, significant odds ratios in bold

3.1. Sub-clinical versus clinical

The single item model odds ratios (ORs) vary considerably in magnitude, from a low of 2.8 (“Cruel to People”) to a high of 8.7 (“Vandalism”) in males, and from a low of 2.4 (“Cruel to Animals”) to a high of 13.1 (“Steal with Confrontation”) in females. Considering the full model, in males, “Out Late,” “Steal without Confrontation,” “Vandalism” and “Truancy” are the criteria most predictive of clinical status. In females, “Out Late” and “Truancy” are also the most highly predictive, in addition to “Fire Setting.” Consistent across sex, “Weapons” is significantly predictive of clinical ASB in the single item model, but non-significant in the full model. The changes in the value and significance of the odds ratios from the single item to full models highlights that, as is expected with a set of items intended to measure a single construct, the items are not entirely independent. When an item’s OR is significant in the single item model but not in the full model, this may suggest that the criteria is not significantly informative after accounting for all of the other items.

3.2. Transient versus persistent

The second pair of ORs test each criterion’s utility in predicting transient versus persistent ASB. Considering the full model in Table 2, in both sexes the 3 strongest predictors of persistence are “Weapons,” “Lies” and “Cruel to People.” The single item model ORs vary to a lesser degree for these comparisons. In both sexes, the criterion “Steal with Confrontation” was not endorsed by anyone in the transient ASB group. Thus, this criterion strongly predicts persistent ASB, however, it was impossible to estimate odds ratios due to non-endorsement by the CD group. This was also true for “Forced Sex” in males.

For single item models, three criteria have non-significant ORs consistent across sex (“Cruel to Animals,” “Out Late” and “Truancy”). Additionally, “Vandalism” was not significantly predictive in males, and three criteria (“Fights,” “Forced Sex” and “Fire Setting”) were non-significant in females. The results from the full model were very similar to those from the single item models. The highest OR was for “Weapons” in both sexes and in both models.

Table 3 presents the specificity and sensitivity of each criterion in predicting persistent ASB. The most sensitive criterion in both sexes was “Stealing without Confrontation”. Specificity of 100% was obtained for “Stealing with Confrontation” in both sexes, and also with “Forced Sex” in males. There was a wide range in sensitivity (1–82%) and moderate range in specificity (76–100%) parameters.

Table 3.

Sensitivity and Specificity of individual criteria and criteria patterns for predicting ASPD diagnoses in subjects with CD

| Males |

Females |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1186 | N = 627 | |||

| DSM-IV CD Criteria | Sensitivitya | Specificityb | Sensitivitya | Specificityb |

| Bully | 57 | 85 | 60 | 78 |

| Fights | 33 | 88 | 32 | 78 |

| Weapons | 25 | 95 | 25 | 94 |

| Cruel to People | 65 | 87 | 53 | 85 |

| Cruel to Animals | 22 | 82 | 5 | 68 |

| Steal with Confront | 5 | 100 | 4 | 100 |

| Forced Sex | 1 | 100 | 2 | 84 |

| Fire Setting | 18 | 86 | 9 | 82 |

| Vandalism | 48 | 82 | 33 | 84 |

| Break and Enter& | ||||

| Lies | 58 | 90 | 72 | 84 |

| Steal without Confront | 82 | 82 | 78 | 79 |

| Out Late | 31 | 83 | 24 | 76 |

| Runaway | 32 | 86 | 59 | 82 |

| Truancy | 28 | 79 | 28 | 77 |

| any 3 total criteria | 18 | 62 | 23 | 55 |

| any 4 total criteria | 22 | 76 | 22 | 81 |

| any 5 total criteria | 20 | 90 | 19 | 91 |

| any 3–5 total criteria | 60 | 75 | 64 | 72 |

| any 6 total criteria | 33 | 98 | 30 | 95 |

| 2 criteria patterns* | ||||

| Weapons & Cruel to People | 21 | 97 | 20 | 96 |

| Weapons & Steal with Confront | 3 | 100 | 2 | 100 |

| Weapons & Lies | 17 | 99 | 20 | 98 |

| Cruel to People & Steal with Confront | 4 | 100 | 2 | 100 |

| Cruel to People & Lies | 40 | 96 | 39 | 94 |

| Steal with Confront & Lies | 4 | 100 | 3 | 100 |

| any 2 of: Weapons, Cruel to People, Steal with Confront, Lies$ | 49 | 95 | 47 | 92 |

| 3 criteria patterns* | ||||

| Weapons & Cruel to People & Steal with Confront | 3 | 100 | 2 | 100 |

| Weapons & Cruel to People & Lies | 14 | 100 | 16 | 100 |

| Weapons & Steal with Confront & Lies | 3 | 100 | 2 | 100 |

| Cruel to people & Steal with Confront & Lies | 4 | 100 | 2 | 100 |

| any 3 of: Weapons, Cruel to People, Steal with Confront, Lies | 16 | 100 | 17 | 100 |

| all 4 criteria* (Weapons, Cruel to People, Steal with Confront, Lies) | 3 | 100 | 1 | 100 |

Sensitivity: Of those with an ASPD diagnosis, the percent that endorse the criterion or criteria cluster

Specificity: Of those endorsing the criterion or criteria cluster, the percent with an ASPD diagnosis

There was not an interview item in the publicly available NESARC data that corresponded to this particular DSM criterion

Post-hoc analyses of combinations of 4 criteria selected as highly informative based on other analyses in the study

Most useful predictor based on high sensitivity and specificity across sex

Sensitivity and specificity estimated using SUDAAN

3.3. Post-Hoc analyses

We conducted post-hoc analyses to examine the sensitivity and specificity obtained from patterns of criterion endorsement. While recognizing the limitations of conducting initial and post-hoc analyses in the same dataset, we conducted these post-hocs hoping to identify distinct patterns of endorsement useful for predicting persistence, which may be tested in other datasets.

We selected 4 criteria that appeared most informative in discriminating between transient versus persistent ASB, based on criterion pattern plots, odds ratios, high specificity and consistency across sex (“Weapons,” “Cruel to People,” “Steal with Confrontation” and “Lies”). Using these 4 criteria we examined all the possible patterns of criterion endorsement, and calculated the sensitivity and specificity of these criterion endorsement patterns (Table 3, lower portion).

Table 3 shows that a pattern of endorsing any 2 of 4 criteria (“Weapons,” “Cruel to People,” “Steal with Confrontation” and “Lies”) identifies persistent ASB with good sensitivity (~48%) and very good specificity (~93%) in both sexes. This particular pattern of criterion endorsement compares favorably in terms of specificity and sensitivity when contrasted with criterion counts of 3, 4, 5 and 6 or more criteria (Table 3).

4. Discussion

We examined the DSM-IV CD criteria in the NESARC dataset. The main objective was to identify adolescent ASBs that may be useful indicators of severity and persistence. The results are informative in three respects. First, they suggest a surprising rate of persistence of ASB into adulthood. Second, the criteria vary significantly in their utility for predicting clinical and persistent ASB. Finally, the results support current etiological and developmental theories of ASB.

Although the strong association between CD and adult antisocial behavior has long been recognized (1, 25), our results suggest that the often quoted rate of persistence of CD to ASPD of 40%, such as in the AACAP conduct disorder practice parameters summary, may be a marked underestimate (26). In the current study 75% of those with CD progressed to ASPD compared with the previously cited estimate of 40% persisting (27). There are several potential reasons for the discrepancy between the previous studies and ours including differences in criteria, thresholds, and samples.

Participants in Robins’ early studies were characterized as antisocial based on a variety of criteria that are not all congruent with the current conceptions of CD and ASPD (e.g., drug use, drinking, sex, marriage, bad language, masturbation, and bad friends) (1, 25). While the results of these pioneering studies are undoubtedly a major contribution, their generalizeability to current conceptions of antisocial behavior (i.e., DSM-IV) is limited. The Zoccolillo et al., (1992) study may be the most contemporary estimate of rate of progression from CD to ASPD, however, this study was based on DSM-III. The DSM-IV includes additional CD criteria, and the threshold for an ASPD diagnosis dropped from 4 to 3 total symptoms. Although Zoccolillo et al. had prospective measures of conduct problems it appears based on reported N’s that they utilized retrospectively reported CD to estimate progression rates (27). Also, the generalizeability of the study is limited by the small number of participants (N=241), and the sampling design. Children included in the study had either lived a substantial part of their lives in cottage-based children’s homes or were from a comparison group of children from inner city areas (27). Although it is often asserted that the majority of adolescents with CD desist, in the present study persistence is the norm. The results presented here are considerably more generalizeable than previous studies because the NESARC is a general population sample including more than 43,000 respondents.

To date relatively little work has focused on predicting adult antisocial outcome from individual childhood antisocial symptoms. This may relate, in part, to Robin’s conclusions from her classic work (Robins, 1978) that number of symptoms was more predictive of adult outcome than any individual childhood symptom. However, Robins utilized some childhood antisocial symptoms not included in the DSM-IV. We examined the relationship between individual CD symptoms (and clusters of symptoms) and progression and found that individual CD criteria vary substantially in their utility for predicting persistence. For example, “Weapons,” “Cruel to People,” and “Lies” are of moderate utility for predicting clinical status (i.e., developing full CD after meeting one CD criterion), but are strong predictors of persistence. In contrast, “Fights,” “Cruelty to Animals,” “Out Late” and “Truancy” are useful for predicting clinical status but poor predictors of persistence. Although endorsement of individual items has been related to severity of ASB in studies of individual behaviors (19), we are unaware of research investigating the set of DSM criteria together.

Differences in the results from single item versus full models provide information regarding the set of DSM-IV criteria. For example, in clinical versus sub-clinical regressions, models including a single CD criterion, compared with the model including all CD criteria, showed markedly disparate results in some cases (e.g., Table 2, “Weapons”). These criteria may be redundant after accounting for other criteria, and potentially of limited utility. This discrepancy may also highlight criteria useful to in identifying severe cases.

Our results are somewhat consistent with Moffitt’s theory regarding behaviors indicative of persistent versus transient offenders (13). People with persistent ASB are likely to display more victim oriented and violent offenses (13), such behaviors were indicative of persistence in our analyses (e.g., “Steal with Confrontation,” “Cruelty to People,” “Weapons” and “Lies”). Transient offenders should commit antisocial acts with peers and engage in behaviors that symbolize adult privilege or signify autonomy from parents (13), these behaviors were of limited utility in predicting persistence in our analyses (e.g., “Fights,” “Out Late” and “Truancy”). Although these clusters of behaviors are informative, they are not entirely definitive as indicated by moderate to low sensitivities for many of the 2 and 3 victim oriented criteria patterns shown in Table 3.

Research suggests that persistent ASB represents a more heritable form of the disorder (18). Generally, criteria predictive of persistence in the present study (e.g., “Weapons” and “Lies”) have higher heritabilities (17, 18) and many CD criteria not significantly predictive of persistent ASB in our results have low or no heritability (17, 18). Correspondence between heritability estimates and the utility of individual symptoms in predicting clinically significant outcomes highlights the potential utility of using criterion heritability as a strategy for refining diagnostic criteria and disentangling heterogeneity.

4.1. Limitations

This study should be considered in view of the following limitations. We were unable to identify CD criterion 10 (“Break and Enter”) in the AUDADIS-IV. If the criterion was not included in the diagnosis of CD provided in the public dataset, this would cause under-diagnosis of CD, and consequently under-diagnosis of ASPD. For our purposes, the missing criterion and resultant under-diagnosis, though important, likely made our criteria analyses more conservative (i.e., our transient group consisted of those who qualified for a CD diagnosis with one criterion missing, but still did not go on to ASPD); however, in this case progression rates could be biased upward. Also, the operationalization of the DSM-IV criteria was based on the AUDADIS-IV. Readers should consider the extent to which this conceptualization matches DSM-IV criteria or other measures of CD and ASPD. Our estimates of persistence may be slightly inflated as both the CD and ASPD diagnoses are based on interviews administered at the same time by the same interviewer. While the data are retrospectively reported, it is important to note that the other studies addressing the same question were similarly and more severely limited. Some of the previous studies were also based on retrospective data and had smaller and less representative samples (7, 27, 28), others were based on adolescent antisocial criteria that represent a fairly tenuous characterization of the current CD diagnostic criteria (1, 25). For this reason, our study may represent the most comprehensive and generalizable examination of this question to date. However, it is still uncertain that the endorsement patterns we identified in the retrospective NESARC data will be effective at predicting persistence in other samples, with prospective data, or in clinical practice. Additionally, it is uncertain whether the high rates of persistence from CD to ASPD that we report will be found in prospective data. Future studies should examine these issues further.

5. Conclusions and future directions

While our results should be confirmed with prospective longitudinal designs, our findings are important for several reasons. First, our results suggest that most individuals with CD go on to develop persistent ASPD emphasizing the severity of this adolescent diagnosis. Second, our analyses suggest that CD criteria involving victim-oriented offenses are more predictive of persistence. These findings may prove useful for clinicians treating adolescents and researchers engaged in longitudinal ASB research. Finally, psychiatrists are currently considering a revision of DSM-IV (29) and predicting clinical course and selecting appropriate treatments are major foci of the DSM. Our study suggests that there may be additional information within the current criteria that is useful in delineating clinical course and outcome. There have been few studies investigating individual DSM criteria with nationally representative samples. Our findings provide information on persistence and information specific to each criterion that may have relevance to the CD section of DSM-V.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants: DA016314, DA020922, DA009842, DA011015, DA012845 The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) is sponsored by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Robins LN. Deviant children grown up. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eaves LJ, Silberg JL, Hewitt JK, Rutter M, Meyer JM, Neale MC, et al. Analyzing twin resemblance in multisymptom data: genetic applications of a latent class model for symptoms of conduct disorder in juvenile boys. Behav Genet. 1993;23(1):5–19. doi: 10.1007/BF01067550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farrington DP, Wikstrom P-OH. Criminal careers in London and Stockholm: A cross-national comparative study. In: Weitekamp EGM, Kerner HJ, editors. Cross-national longitudinal research on human development and criminal behavior. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1994. pp. 65–89. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farrington DP, Loeber R, Elliot DS, Hawkins DJ, Kandel DB, Klein MW, et al. Advancing knowledge about the onset of delinquency and crime. In: Lahey B, Kazdin A, editors. Advances in clinical child psychology. New York: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 231–342. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooner RK, Schmidt CW, Felch LJ, Bigelow GE. Antisocial behavior of intravenous drug abusers: implications for diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1992 Apr;149(4):482–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanford M, Boyle MH, Szatmari P, Offord DR, Jamieson E, Spinner M. Age-of-onset classification of conduct disorder: reliability and validity in a prospective cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(8):992–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199908000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marmorstein NR. Adult antisocial behaviour without conduct disorder: demographic characteristics and risk for cooccurring psychopathology. Can J Psychiatry. 2006 Mar;51(4):226–33. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marmorstein NR, Iacono WG. Longitudinal follow-up of adolescents with late-onset antisocial behavior: a pathological yet overlooked group. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005 Dec;44(12):1284–91. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000181039.75842.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pardini D, Obradovic J, Loeber R. Interpersonal callousness, hyperactivity/impulsivity, inattention, and conduct problems as precursors to delinquency persistence in boys: a comparison of three grade-based cohorts. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2006 Feb;35(1):46–59. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simonoff E, Elander J, Holmshaw J, Pickles A, Murray R, Rutter M. Predictors of antisocial personality. Continuities from childhood to adult life. Br J Psychiatry. 2004 Feb;184:118–27. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gretton HM, Hare RD, Catchpole RE. Psychopathy and offending from adolescence to adulthood: a 10-year follow-up. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004 Aug;72(4):636–45. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotler JS, McMahon RJ. Child psychopathy: theories, measurement, and relations with the development and persistence of conduct problems. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2005 Dec;8(4):291–325. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-8810-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev. 1993;100(4):674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Childhood predictors differentiate life-course persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways among males and females. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13(2):355–75. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Dickson N, Silva PA, Stanton W. Childhood-onset versus adolescent-onset antisocial conduct problems in males: Natural history from ages 3 to 18 years. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:399–424. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Harrington H, Milne BJ. Males on the life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways: follow-up at age 26 years. Dev Psychopathol. 2002;14(1):179–207. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402001104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelhorn HL, Stallings MC, Young SE, Corley RP, Rhee SH, Hewitt JK. Genetic and environmental influences on conduct disorder: symptom, domain and full-scale analyses. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;46(6):580–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyons MJ, True WR, Eisen SA, Goldberg J, Meyer JM, Faraone SV, et al. Differential heritability of adult and juvenile antisocial traits. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(11):906–15. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950230020005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin G, Bergen HA, Richardson AS, Roeger L, Allison S. Correlates of firesetting in a community sample of young adolescents. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004 Mar;38(3):148–54. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohan JL, Johnston C. Gender appropriateness of symptom criteria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional-defiant disorder, and conduct disorder. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2005 Summer;35(4):359–81. doi: 10.1007/s10578-005-2694-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant BF, Moore TC, Shepard J, Kaplan K. Source and Accuracy Statement: Wave 1 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003 Jul 20;71(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ. Co-occurrence of DSM-IV personality disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Compr Psychiatry. 2005 Jan-Feb;46(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SUDAAN. Research Triangle Institute. Software for Survey Data Analysis (SUDAAN) Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2002. Version 9.0 ed. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robins LN. Sturdy childhood predictors of adult antisocial behaviour: replications from longitudinal studies. Psychol Med. 1978 Nov;8(4):611–22. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700018821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steiner H, Dunne JE. Summary of the practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with conduct disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997 Oct;36(10):1482–5. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199710000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zoccolillo M, Pickles A, Quinton D, Rutter M. The outcome of childhood conduct disorder: implications for defining adult personality disorder and conduct disorder. Psychol Med. 1992 Nov;22(4):971–86. doi: 10.1017/s003329170003854x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cottler LB, Price RK, Compton WM, Mager DE. Subtypes of adult antisocial behavior among drug abusers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995 Mar;183(3):154–61. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Widiger TA, Simonsen E, Krueger R, Livesley WJ, Verheul R. Personality disorder research agenda for the DSM-V. J Personal Disord. 2005 Jun;19(3):315–38. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.3.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]