Abstract

Objective: Foreign body aspirations comprise the majority of accidental deaths in childhood. Diagnostic delay may cause an increase in mortality and morbidity in cases without acute respiratory failure. We report our diagnostic and compare the relevant studies available in literature to our results.

Methods: In our Hospital, bronchoscopy was performed on 1015 patients with the diagnosis of foreign body aspirations (from 1998 to 2008). Of these cases, 63.5% were male and 36.5% female. Their ages ranged from 2 months to 9 years (mean 2.3 years). Diagnosis was made on history, physical examination, radiological methods and bronchoscopy.

Results: Foreign bodies were localized in the right main bronchus in 560 (55.1%) patients followed by left main bronchus in 191 (18.8%), trachea in 173 (17.1%), vocal cord in 75(7.4%) and both bronchus in 16 (1.6%). Foreign body was not found during bronchoscopy in 48 cases (8.7%). The majority of the foreign bodies were seeds. Foreign bodies were removed with bronchoscopy in all cases. Pneumonia occurs in only 2.9% (29/1015) patients out of our cases.

Conclusion: Rigid bronchoscopy is very effective procedure for inhaled foreign body removal with fewer complications. Proper use of diagnostic techniques provides a high degree of success, and the treatment modality to be used depending on the type of the foreign body is mostly satisfactory.

Keywords: Foreign body aspiration, Bronchoscopy, radiological methods

Introduction

Foreign body (FB) aspirations in childhood are frequently emergency conditions especially in less than 3 years age, comprising an important proportion of accidental deaths 1-3. Delay in diagnosis and, consequently, a series of chronic pulmonary pathologic conditions may occur in the cases without acute respiratory failure. It is estimated that almost 600 children under 15 years of age die per year in the USA following aspiration of foreign bodies 4. In fact, choking on food has been the cause of between 2500 to 3900 deaths per year in the USA, when taking both children and adults into consideration 5, 6. The main symptoms associated with aspiration are suffocation, cough, stupor, excessive sputum production, cyanosis or difficulty in breathing. These symptoms develop immediately after the aspiration 6, 7. If the event is noticed in time, the child is taken to the hospital for open tube bronchoscopy. If the event is unnoticed and there are no indicative clinical or laboratory findings, the patient can be hospitalized for bronchitis, bronchial asthma or in neglected cases for pulmonitis, with dangerous consequences for the health and life of the patient due to the delayed diagnosis 8.

The majority of aspirated objects are organic in nature, mainly food. Peanuts are the cause most commonly identified by different authors 9-12, but some mention melon and sunflower seeds as the predominant causes 13. This variation in types of organic materials can be explained by cultural, regional and feeding habit differences. The high incidence of aspirated seeds is related to the absence of molar tooth development between 2 and 3 years of age. This results in an inadequate chewing process, therefore the offering of chunks of food and seeds of any kind to this age group should be avoided. It is also strongly recommended that younger children should not be allowed to play with small plastic or metallic objects. Surprisingly, however, plastic toys are not a frequent cause of FBA in series from developing countries but they represent more than 10% of those identified in the developed world 13- 15.

Management of inhaled foreign body depends on the site of impaction of foreign body. Laryngeal and subglottic foreign bodies need urgent intervention in the form of tracheostomy or urgent bronchoscopy, whereas foreign bodies in the right or left main bronchus cause comparatively less airway problem 16-19. Rigid bronchoscopy is the recommended procedure in children with suspected FBs. However, flexible bronchoscopy is less invasive, more cost-effective, does not require general anesthesia and seems more helpful in children with insufficient historical, clinical or radiological findings for FBA 13, 14. This retrospective study was conducted to investigate the incidence of clinically unsuspected FBA in patients who underwent flexible bronchoscopy in our institution; and evaluated the causes resulting in diagnosis of FBA, and the location and type of foreign body, anesthesia methods, complications, and outcome.

Patients and methods

In our Hospitals 1015 cases with the diagnosis of FBA were evaluated and treated from January 1988 to November 2008. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ahwaz Jondishapour University of Medical Sciences and informed parent have signed the consent form of these patients, 644 (63.5%) while 371 were female (36.5%). The average age was 2.3 years (range 2 months-9 years) (Table 1). Plain chest radiography (CXR) was required in all but 162 (16%) patients who underwent immediate bronchoscopy owing to acute respiratory distress following history and physical examination. Computed tomography was used to determine the presence of lung complications due to FB in late period. The most frequently presented symptom was coughing in 845 (83.3%) patients (Table 3). FB was found during bronchoscopy in 96.2% (977 of 1015) of the patients with the history of FBA. Eight of the remaining 38 patients had a history of expectorated FB. A total of 1028 bronchoscopies using a rigid bronchoscope in appropriate size and under general anesthesia were done. Bronchoscopy was repeated once or twice in 11 (1.08%) of cases, for reasons such as the necessity of a recession in bronchoscopy due to the prolongation in the process of removing the FB, and the physical and radiological examinations after bronchoscopy suggestive of the ongoing presence of a foreign body. Prophylactic antibiotics were administered for 1-3 days to the patients who inhaled vegetable matters and had detected findings causing infection. If any specific microorganism was isolated from bronchial lavage taken at the time of bronchoscopy, the treatment continued with appropriate antibiotics. Patients were categorized into two groups according to the elapsed time of referral; those that were within less than 24 hrs were termed 'early', and those diagnosed after 24 hrs or more were termed 'late'. We also did compare all the literature reported FBA with long time course study from different courtiers around the world (Table 6) 22-37.

Table 1.

Types of airway foreign bodies in children

| Foreign body | No. of patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Seed | 648 | 63.87 |

| Food material | 116 | 11.44 |

| Peanut | 99 | 9.8 |

| Bone | 54 | 5.3 |

| Metallic object | 44 | 4.4 |

| Plastic object | 24 | 2.4 |

| Paper | 11 | 1.07 |

| coin | 9 | 0.85 |

| Stone | 6 | 0.53 |

| Bullet | 2 | 0.17 |

| coil | 2 | 0.17 |

| Total | 1015 | 100 |

Table 3.

Presenting history of signs and symptoms

| Symptoms | No. of patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Coughing | 741 | 73.03 |

| Cyanosis | 134 | 13.18 |

| Dyspnea | 47 | 4.64 |

| Wheezing | 33 | 2.2 |

| Unsolved pulmonary infection | 22 | 1.73 |

| Choking | 18 | 3.2 |

| Stridor | 9 | 0.89 |

| Cases without symptoms | 11 | 1.13 |

| Total | 1015 | 100 |

Table 6.

Available data reported in literature concerning Foreign body Aspiration in infants and child

| No. of patients | Age range (months - years) | Study duration (years) | Most common clinical symptom (% frequency) | Most common age (% frequency) | Commonest foreign body | M: F | References - Country [References] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 120 | 6 - 6 | 7 years (1997-2003) | Cough (70%) | 1- 3 years (55.8%) | Ground nuts | 93:27 | Gandhi et al., 2007- India 22 |

| 548 | 2 -16 | 10 years (1987- 1997) | Cough (83%) | 2 -4 years (23.3%) | Dried nuts | 305:243 | Oğuzkaya et al., 1998- Turkey 23 |

| 44 | 3 - 15 | 5 years (2001 - 2006) | Cough (82%) | < 3 years (77%) | ------ | --- | Rahbarimanesh et al., 2008- Iran 24 |

| 87 | 5 - 15 | 8 years (1990 - 1998) | -------------- | ----------- | Dried nuts | 57:30 | Metrangolo et al., 1999- Italy 25 |

| 316 | 0 - 12 | 10 years (1995 - 2005) | Breathlessness (93.2%) | 1 - 3 years (69.9%) | Ground nuts | 139:67 | Kalyanappagol et al., 2007- India 26 |

| 40 | 1 - 20 | 4 years (1996 - 2000) | Cough (75%) | 5 - 16 (60%) | Whistle | 28:12 | Rehman et al., 2000- Pakistan27 |

| 189 | 2.7 ± 2.12 ₤ | 4 years (1997 - 2001) | Choking (43.3%) | 1 - 3 years (72%) | Pip | 105:84 | Erikçi et al., 2003- Turkey 28 |

| 357 | 4 - 70 | 10 years (1990 - 2000) | Cough (78.4%) | 10 - 25 years (43.2%) | Needle | 151:206 | Eroğlu et al., 2003- Turkey 29 |

| 244 | 0-17 | 10 years (1994 - 2003) | ----------- | 0-3 years (68%) | Peanuts | 107:75 | Latifi et al., 2006- Kosovo 30 |

| 132 | 0-10 | 20 years (1997 - 2007) | Wheeze and cough (53.8%) | 1- 3 years (41.6%) | Peanuts | 80:52 | Yadav et al., 2007 - Singapore 31 |

| 210 | 0-13 | 8 years (1991 - 1999) | Suffocation history (91.5%) | 1-2 years (53.3%) | Nuts | 134:76 | Skoulakis et al., 2000 - Greece 32 |

| 32 | 43.81 ± 21.43 ₤ | 14 years (1987-2008) | Acute infection (25%) | ---------------- | Inorganics objects | 21:11 | Blanco et al., 2009 - Spain 33 |

| 27 | 0 - 18 | 13 years (1993-2006) | Cough (100%) and history of choking (74%) | -------------- | Peanuts and watermelon seeds | ----- | Chik et al., 2009-Hong kong 34 |

| 96 | 10 -70 | 12 years (1995-2007) | Cough (82.3%) | 1-3 years (32.1%) | Peanuts | 62:34 | Cobanoğlu and Yalçınkaya, 2009 - Turkey 35 |

| 1027 | 5 - 14 | 8 years (2000-2008) | Paroxysmal cough (84.3%) | -------------- | Dried nuts | 626:401 | Tang et al., 2009 -China 36 |

| 78 | 0 - 14 | 5 years (1997-2002) | -------- | <3 years (89.5%) | seeds, nuts, berries and grains | 45:33 | Göktas et al., 2009- Germany 37 |

| 1015 | 2 - 9 | 20 years (1998-2008) | Cough (73.03%) | 1- 3 years (54.8%) | Seed | 644:371 | Present study |

Results

A total of 1015 patients with foreign body aspiration during June January 1988 to November 2008 were admitted at Imam Khomeini and Apadana Hospitals, Ahwaz, Iran. An over whelming majority was male 644 (63.5%) while 371 were female (36.5%) with male to female ratio of 1.73:1. 599 (59%) patients were categorized into the early group and 416 (41%) into the late group. The age distribution of study groups include 218 (21.5%) patients less than 1 year age, 556 (54.8%) of the cases were 1 to 3 years following with 160 (15.8%) cases in 3 to 6 years of age range and 81 (7.9%) of the patients were more than 6 years of age. The maximum incidents occurred at the age of 1-3 years with a value of 556 cases (54.8%). All the patients were scoped under general anesthesia using rigid bronchoscope seed was retrieved in 648 (63.87%) patients, food material in 116 (11.44%), peanut in 99 (9.8%), bone given in 54 (5.3%) followed by many other FBs like metallic and plastic objects with various number and percentage given in table 1. Obstructive emphysema was seen in 324 (31.9 %) patients while opaque FB in 160 (15.8%), bronchitis or bronchectasis in 140 (13.8%) and unilateral atelectasis in 100 (9.8%) and 29 (2.9%) show labor pneumonia on chest x-ray. The rest 262 patients (25.8%) had normal chest x-ray. The most common site of foreign body enlodgment was right main bronchus in 560 (55.1%) patients followed by left main bronchus in 191 (18.8%), trachea in 173 (17.1%), vocal cord in 75(7.4%) and both bronchus in 16 (1.6%).

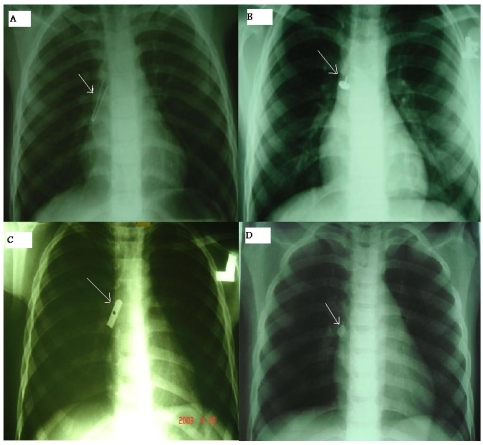

The duration of enlodgment of foreign body ranged from 0 hours to more than 6 month (Table 2). In fifty seven patients recovery was un-eventful except mild laryngeal edema which was treated by steroids and humidified air. We had mortality in two patients due to brain anoxia. Sixty patients had multiple FBs in both right and left bronchus. Mostly patients were discharged from hospital on third day. Seven hundred-forty one patients (73.03%) presented with cough, 134 patients (13.18%) had cyanosis and 47 patients (4.64 %) had dyspnea as shown in table 3. Rare cases (Figure) were removed by appropriate tools and techniques under bronchoscopy. A cylinder-shaped plastic whistle removed from the main right bronchus by a grasper forceps (Figure 1A), a thumbtack was removed by using a crocodile forceps (Figure 1B), a sharpener was removed by a cup forceps (Figure 1C), and the dental piece FB was extracted (Figure 1D).

Table 2.

Duration of enlodgment of foreign body

| Length of time | No. of patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0- 8 hours | 146 | 14.4 |

| 8 - 24 hours | 123 | 12.2 |

| 1-7 days | 452 | 44.5 |

| 7 - 14 days | 95 | 9.3 |

| 14- 30 days | 103 | 10.1 |

| 30 - 180 days | 77 | 7.6 |

| More than 180 days | 19 | 1.9 |

| Total | 1015 | 100 |

Figure 1.

Different foreign bodies removed by bronchoscopy (arrows). (A) Endoscopic image of a whistle lodged in the right bronchus. (B) A thumbtack removed from a patient with bronchoscopy. (C) Endoscopic image 8 of a sharpener in the right middle lobe bronchus. (D) A dental piece removed from a patient.

Cough was the commonest symptom after aspiration in both groups; cyanosis (79/1015, 7.8%), dyspnea (37/1015, 3.7%), unsolved pulmonary infection (14/1015, 1.4%), and chocking (11/1015, 1.1%) were more common in early diagnosis group; whereas cyanosis (55/1015, 5.4%), dyspnoea (10/1015, 1%) were more common in those diagnosed late. Also the commonest symptom after aspiration was cough in all age groups. The Cough (419/1015, 41.3%), cyanosis (58/1015, 5.7%), dyspnea (31/1015, 3%), and wheeze (21/1015, 2%) were more common in 1-3 years age group (Table 4). Seeds were the commonest aspirated organic objects (648/1015, 61.85%), followed by food material (116/1015, 11.42%), peanut (99/1015, 9.74%), and bone (54/1015, 5.31%). In case of inorganic materials the most common one was metallic object (44/1015, 4.32%) followed by plastic objects (24/1015, 2.34%). The commonest age was less than 3 years. The relation between age and aspirated mayerial type has given in detail in table 5.

Table 4.

Presenting clinical features, complications, and corresponding patient numbers and percentage with foreign body type and age

| Complications | Referral groups | Age groups (years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early No. (Percentage) | Late No. (Percentage) | < 1 No. (Percentage) | 1 -3 No. (Percentage) | 3 -6 No. (Percentage) | >6 No. (Percentage) | |

| Coughing | 427 (42%) | 314 (30.9%) | 156 (15.4%) | 419 (41.3%) | 105 (10.3%) | 61 (6%) |

| Cyanosis | 79 (7.8%) | 55 (5.4%) | 21 (2%) | 58 (5.7%) | 39 (3.9) | 16 (1.6%) |

| Dyspnea | 37 (3.7%) | 10 (1%) | 15 (1.5%) | 31 (3%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 |

| Wheezing | 2 (0.2%) | 4 (0.4%) | 6 (0.6%) | 21 (2%) | 6 (0.6%) | 0 |

| Unsolved pulmonary infection | 14 (1.4%) | 8 (0.8%) | 7 (0.7%) | 11 (1%) | 4 (0.4) | 0 |

| Choking | 11 (1.1%) | 7 (0.6%) | 6 (0.6%) | 10 (1%) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Stridor | 7 (0.7%) | 2 (0.2%) | 4 (0.4%) | 5 (0.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Cases without symptoms | 5 (0.5%) | 6 (0.6%) | 3 (0.3%) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.4%) | 3 (0.3%) |

| Multiple | 17 (1.7%) | 10 (1%) | - | - | - | - |

| Total (n=1015) | 599 (59.1%) | 416 (40.9%) | 218 (21.5%) | 556 (54.6%) | 160 (15.9%) | 81 (8%) |

Table 5.

Presenting corresponding patient numbers with foreign body type and age

| Age groups | Foreign body type No. (Percentage) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed | Food material | Peanut | Bone | Metallic object | Plastic object | Paper | Coin | Stone | Bullet | Coil | |

| < 1 | 95 (9.35%) | 74(7.3%) | 0 | 0 | 30 (2.95%) | 19(1.87%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 -3 | 399 (39.3%) | 11 (1.08%) | 78 (7.68%) | 49 (4.82%) | 10 (0.98%) | 3(0.29%) | 10(0.98%) | 4(0.39%) | 1(0.098%) | 0 | 0 |

| 3 -6 | 122 (12%) | 16 (1.57%) | 11(1.08%) | 0 | 0 | 1(0.098%) | 1(0.098%) | 3(0.29%) | 5(0.49%) | 1(0.098%) | 0 |

| >6 | 46 (4.5%) | 15 (1.47%) | 10 (0.98%) | 5 (0.49%) | 4 (0.39%) | 1(0.098%) | 0 | 2(0.19%) | 0 | 1(0.098%) | 2(0.19%) |

| Total (n=1015) | 648 (61.85%) | 116 (11.42%) | 99 (9.74%) | 54 (5.31%) | 44 (4.32%) | 24(2.35%) | 11(1.083%) | 9(0.88%) | 6(0.59%) | 2 (0.19%) | 2(0.19%) |

Discussion

Foreign body aspiration is frequently encountered in pediatric practice; however, the condition is often not diagnosed immediately because there are no specific clinical manifestations. Usually, there is a suggestive history of choking, although the classic clinical presentation, with coughing, wheezing, and diminished air inflow, is seen in less than 40% of the patients; other symptoms include cyanoses, fever, and stridor. Sometimes, FBA can be completely asymptomatic. The evolution of FBA can lead to variable degrees of respiratory distress, atelectasis, chronic coughing, recurrent pneumonia, and even death 38, 39. Previous reports indicate that male gender is present in 60—66% of cases and children in the first and second year of life are predominantly affected 40, 41. In this study the frequency of FBA in male was 63.5% and the ages 1 to 3 years were predominantly affected. The most common foreign body inhaled, Symptoms, most frequent age, and type of inhaled foreign body are different from region to region across the world.

Bronchoscopy should be used as a diagnostic method in cases where the possibility of FB aspiration cannot be ruled out through history, physical and radiological examination. Upon diagnosis, early bronchoscopy is necessary because the earlier the bronchoscopy the lesser the complications. Some children with respiratory complaints wrongly have long been receiving treatment for pneumonia or asthma only because these current diagnostic methods were ineffective. Their definite diagnosis and treatment were provided by bronchoscopy, which was resorted to after unresponsiveness to previous treatment. Dikensoy et al. reported that morbidity evaluated in cases where medical treatment without bronchoscopy was used curatively 42.

Ventilation in the other bronchial system is more reliable even if it prolongs the duration of bronchoscopy. On the contrary, the attempts to remove a large piece at a time require that the bronchoscope be pulled out together with the piece and necessitate a further bronchoscopy to check for additional FBs in the distal segment. In FBA, bronchiectasis and pulmonary damage can occur as complications of the late period 43. Bronchoscopy in children under 12 months requires skill because technical difficulties due to small instrumentation and bronchospasm commonly occur when compared to older children. Boorish contact of the bronchoscope or forceps with the bronchial wall, and the prolongation of bronchoscopy can be considered to be factors which contribute to spasm. It has been reported that a bronchoscope with appropriate diameter should be chosen and the procedure should be limited to 20 min in order to avoid possible sub-glottic and laryngeal edema and bronchospasm after bronchoscopy 44.

Previous reports indicate that male gender is present in 60—66% of cases and children in the first and second year of life are predominantly affected 45-47. Our data regarding the incidence, gender, and age of patients with foreign body aspiration were consistent with the literature. Aspirated foreign bodies can be classified into two categories, organic and inorganic. Most of the aspirated foreign bodies are organic materials, such as nuts and seeds in children, and food and bones in adults. The most common type of inorganic aspirated substances in children are beads, coins, pins, small parts of varies toys, and small parts of school equipment such as pen caps 48. As we listed the different type of foreign bodies in Asian countries such as India, 22 China, 36 and Turkey 23 the most common were organic type include peanut, ground and dried nuts, while in European countries such as Italy 25 and Kosovo 30 the most common were organic type include dried nuts as well as inorganic type in some countries like Spain 33. The most common at risk age found less than 3 years in most reported paper that was in agreement with our study 22 - 37.

Pneumonia, the most frequent complication after bronchoscopy in the literature 29, occurs in only 2.9% (29/1015) patients out of our cases because of the intensive antibiotics, chest physiotherapy, and cool mist provided, especially after the aspiration of oily seeds. FBA, one of the leading causes of accidental child deaths at home, does rarely cause deaths after the victim is safely brought to hospital, did not occur in our cases because of the intensive cares and immediate bronchoscopy 44. FBA can be identified using the existing diagnostic methods and, if the methods of removal are appropriate for the type of the FB is used, favorable outcomes with lower mortality and morbidity rates will be seen. Most frequently, aspirated objects are food, which is involved in 75% of the cases; other organic materials, such as bones, teeth, and plants, 7%; non-organic materials, such as metals and plastics, 13%; rocks, 1%; and toys or parts of toys, 1% 49. In our research the most common FB was seed.

Almost 40% of our patients were diagnosed as having FBA 24 hrs after onset of symptoms. The delayed diagnosis rate in our locality was high compared to rates of 17% and 23% reported in other Asian studies 50, 51. One possible reason for a delayed diagnosis was that parents were not aware of the significance of sign and symptoms such as cough and choking. Because the children usually do not have severe symptoms immediately after the choking, parents may not seek medical help until there is a persistent cough and fever. Young children below the age of 3 years are particularly at risk of aspiration, as demonstrated in our study as well as others 50, 28.

In conclusion, diagnosis of FBA in children is difficult, because its presentation can be mistaken as asthma or respiratory tract infection, which leads to delayed diagnosis and treatment, and can result in intrabronchial granuloma formation. Therefore, early rigid bronchoscopy is very effective procedure for inhaled foreign body removal with fewer complications. Although the rate of mortality resulting from foreign body aspiration is low, cooperation amongst pediatricians, radiologists, and ENT specialists is required for rapid diagnosis and treatment.

References

- 1.Divisi D, Di Tommaso S, Garramone M, Di Francescantonio W, Crisci RM, Costa AM, Gravina GL, Crisci R. Foreign bodies aspirated in children: role of bronchoscopy. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007 Jun;55(4):249–52. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brkić F, Umihanić S. Tracheobronchial foreign bodies in children. Experience at ORL clinic Tuzla, 1954-2004. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007 Jun;71(6):909–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roda J, Nobre S, Pires J, Estêvão MH, Félix M. Foreign bodies in the airway: A quarter of a century's experience. Rev Port Pneumol. 2008;14(6):787–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown TC, Clark CM. Inhaled foreign bodies in children. Med J Aust. 1983;2:322–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menéndez AA, Gotay Cruz F, Seda FJ, Vélez W, Trinidad Pinedo J. Foreign body aspiration: experience at the University Pediatric Hospital. P R Health Sci J. 1991 Dec;10(3):127–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiyan G, Gocmen B, Tugtepe H, Karakoc F, Dagli E, Dagli TE. Foreign body aspiration in children: The value of diagnostic criteria. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(7):963–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomaske M, Gerber AC, Stocker S, Weiss M. Tracheobronchial foreign body aspiration in children - diagnostic value of symptoms and signs. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006 Aug 19;136(33-34):533–8. doi: 10.4414/smw.2006.11459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karakoc F, Cakir E, Ersu R, Uyan ZS, Colak B, Karadag B, Kiyan G, Dagli T, Dagli E. Late diagnosis of foreign body aspiration in children with chronic respiratory symptoms. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007 Feb;71(2):241–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Midulla F, Guidi R, Barbato A, Capocaccia P, Forenza N, Marseglia G, Pifferi M, Moretti C, Bonci E, De Benedictis FM. Foreign body aspiration in children. Pediatr Int. 2005 Dec;47(6):663–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2005.02136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raos M, Klancir SB, Dodig S, Koncul I. Foreign bodies in the airways in children. Lijec Vjesn. 2000 Mar;122(3-4):66–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsolov Ts, Melnicharov M, Perinovska P, Krutilin F. Foreign bodies in the upper airways of children - problems relating to diagnosis and treatment. Khirurgiia (Sofiia) 1999;55(5):33–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emir H, Tekant G, Beşik C, Eliçevik M, Senyüz OF, Büyükünal C, Sarimurat N, Yeker D. Bronchoscopic removal of tracheobroncheal foreign bodies: value of patient history and timing. Pediatr Surg Int. 2001 Mar;17(2-3):85–7. doi: 10.1007/s003830000485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brkić F, Delibegović-Dedić S, Hajdarović D. Bronchoscopic removal of foreign bodies from children in Bosnia and Herzegovina: experience with 230 patients. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001 Sep 28;60(3):193–6. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(01)00531-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oğuz F, Citak A, Unüvar E, Sidal M. Airway foreign bodies in childhood. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000 Jan 30;52(1):11–6. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(99)00283-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skoulakis CE, Doxas PG, Papadakis CE, Proimos E, Christodoulou P, Bizakis JG, Velegrakis GA, Mamoulakis D, Helidonis ES. Bronchoscopy for foreign body removal in children. A review and analysis of 210 cases. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000 Jun 30;53(2):143–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(00)00324-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaupa P, Saxena AK, Barounig A, Höllwarth ME. Management strategies in foreign-body aspiration. Indian J Pediatr. 2009 Feb;76(2):157–61. doi: 10.1007/s12098-008-0231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunn GR, Wardrop P, Lo S, Cowan DL. Management of suspected foreign body aspiration in children. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004 Jun;29(3):286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2004.00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osman EZ, Webb CJ, Clarke RW. Management of suspected foreign body aspiration in children. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2003 Jun;28(3):276. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2003.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunn GR, Wardrop P, Lo S, Cowan DL. Management of suspected foreign body aspiration in children. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2002;27(5):384–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2002.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinot A, Closset M, Marquette CH, Hue V, Deschildre A, Ramon P, Remy J, Leclerc F. Indications for flexible versus rigid bronchoscopy in children with suspected foreign-body aspiration. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997 May;155(5):1676–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.5.9154875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lima JA, Fischer GB. Foreign body aspiration in children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2002 Dec;3(4):303–7. doi: 10.1016/s1526-0542(02)00265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gandhi R, Jain A, Agarwal R, Vajifdar H. Tracheobronchial Foreign Bodies- A seven years review. J Anesth Clin Pharmacology. 2007;23(1):69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oğuzkaya F, Akçali Y, Kahraman C, Bilgin M, Sahin A. Tracheobronchial foreign body aspirations in childhood: a 10-year experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1998;14(4):388–92. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(98)00205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahbarimanesh A, Noroozi E, Molaian M, Salamati P. Foreign Body Aspiration: A five-year Report in a Children's Hospital. Iranian Journal of Pediatrics. 2008;18(2):191–192. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metrangolo S, Monetti C, Meneghini L, Zadra N, Giusti F. Eight Years' Experience With Foreign-Body Aspiration in Children: What Is Really Important for a Timely Diagnosis? J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34(8):1229–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalyanappagol VT, Kulkarni NH, Bidri LH. Management of tracheobronchial foreign body. aspirations in paediatric age group - a 10 year retrospective analysis. Indian J Anaesth. 2007;51(1):27– 23. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rehman A, Ghani A, Mian FA, Ahmad I, Khalil M, Akhtar N. foreign body aspiration. THE PROFESSIONAL. 2000;7(3):388–392. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erikçi V, Karaçay S, Arikan A. Foreign body aspiration: a four-years experience. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2003;9(1):45–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eroğlu A, Kürkçüoğlu IC, Karaoğlanoğlu N, Yekeler E, Aslan S, Başoğlu A. Tracheobronchial foreign bodies: a 10 year experience. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2003;9(4):262–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Latifi X, Mustafa A, Hysenaj Q. Rigid tracheobronchoscopy in the management of airway foreign bodies: 10 years experience in Kosovo. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70(12):2055–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yadav S P S, Singh J, Aggarwal N, Goel A. Airway foreign bodies in children: experience of 132 cases. Singapore Med J. 2007;48(9):850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skoulakis CE, Doxas PG, Papadakis CE, Proimos E, Christodoulou P, Bizakis JG, Velegrakis GA, Mamoulakis D, Helidonis ES. Bronchoscopy for foreign body removal in children. A review and analysis of 210 cases. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000 Jun 30;53(2):143–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(00)00324-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramos MB, Fernandez-Villar A, Rivo JE, Leiro V, Garcia-Fontan E, Botana MI, Torres ML, Canizares MA. Extraction of airway foreign bodies in adults: experience from 1987-2008. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009 Sep;9(3):402–5. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2009.207332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chik KK, Miu TY, Chan CW. Foreign body aspiration in Hong Kong Chinese children. Hong Kong Med J. 2009 Feb;15(1):6–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cobanoğlu U, Yalçınkaya I. Tracheobronchial foreign body aspirations. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2009 Sep;15(5):493–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang LF, Xu YC, Wang YS, Wang CF, Zhu GH, Bao XE, Lu MP, Chen LX, Chen ZM. Airway foreign body removal by flexible bronchoscopy: experience with 1027 children during 2000-2008. World J Pediatr. 2009 Aug;5(3):191–5. doi: 10.1007/s12519-009-0036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Göktas O, Snidero S, Jahnke V, Passali D, Gregori D. Foreign Body Aspiration in Children: Field Report of a German Hospital. Pediatr Int. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2009.02913.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sirmali M, Türüt H, Kisacik E, Findik G, Kaya S, Taştepe I. The relationship between time of admittance and complications in paediatric tracheobronchial foreign body aspiration. Acta Chir Belg. 2005;105(6):631–4. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2005.11679791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oliveira CF, Almeida JF, Troster EJ, Vaz FA. Complications of tracheobronchial foreign body aspiration in children: report of 5 cases and review of the literature. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo. 2002;57(3):108–11. doi: 10.1590/s0041-87812002000300005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sersar SI, Rizk WH, Bilal M, El Diasty MM, Eltantawy TA, Abdelhakam BB, Elgamal AM, Bieh AA. Inhaled foreign bodies: presentation, management and value of history and plain chest radiography in delayed presentation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006 Jan;134(1):92–9. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tariq SM, George J, Srinivasan S. Inhaled foreign bodies in adolescents and adults. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2005 Dec;63(4):193–8. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2005.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dikensoy O, Usalan C, Filiz A. Foreign body aspiration: clinical utility of flexible bronchoscopy. Postgrad Med J. 2002 Jul;78(921):399–403. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.921.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doğru D, Nik-Ain A, Kiper N, Göçmen A, Ozçelik U, Yalçin E, Aslan AT. Bronchiectasis: the consequence of late diagnosis in chronic respiratory symptoms. J Trop Pediatr. 2005 Dec;51(6):362–5. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmi036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pinzoni F, Boniotti C, Molinaro SM, Baraldi A, Berlucchi M. Inhaled foreign bodies in pediatric patients: review of personal experience. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007 Dec;71(12):1897–903. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baharloo F, Veyckemans F, Francis C, Biettlot MP, Rodenstein DO. Tracheobronchial foreign bodies: presentation and management in children and adults. Chest. 1999;115(5):1357–62. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.5.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swanson K, Prakash U. Airway foreign bodies in adults. J Bronchol. 2003;10:107–111. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oguzkaya F, Akcali Y, Kahraman C, Bilgin M, Sahin A. Tracheobronchial foreign body aspirations in childhood: a 10-year experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1998;14(4):388–392. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(98)00205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dikensoy O, Usalan C, Filiz A. Foreign body aspiration: clinical utility of flexible bronchoscopy. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:399–403. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.921.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Causey AL, Talton DS, Miller RC, Warren ET. Aspirated safety pin requiring thoracotomy: report of a case and review. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1997;13:397–400. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199712000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chiu CY, Wong KS, Lai SH, Hsia SH, Wu CT. Factors predicting early diagnosis of foreign body aspiration in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21:161–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tan HK, Brown K, McGill T, Kenna MA, Lund DP, Healy GB. Airway foreign bodies (FB): a 10-year review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;56:91–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(00)00391-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]